Abstract

Introduction

Afghanistan is a low-income country where providing essential healthcare services is lifesaving for millions. The COVID-19 pandemic, the government and the international aid changes have affected the overburdened and fragile health system and put a risk on universal health coverage in Afghanistan. In this study, we aim to study the changes and backlogs to the essential health services during and after COVID-19 pandemic (Feb 2020 to Sep 2022) in Afghanistan.

Method

A cross-sectional study of health facilities was conducted in nine provinces of Afghanistan. A randomly selected 165 public and private primary care centers and hospitals in 49 districts were studied. A WHO standardized questionnaire was used for this survey. Trained staff met the facility managers in person and completed the questionnaire by individual interviews during September 2022.

Result

Hospitals located mostly in urban areas (n = 39, 65%) and clinics were located mostly in rural areas (n = 74, 71.1%) and governed by the government and the NGOs (76.6% of hospitals and 84.7% of clinics). The average number of staff per facility was 118 (SD = 180) for hospitals and 16(SD = 7) for clinics. 27 (46.5%) of hospitals and 44 (41.9%) of clinics reported that they experienced a higher outpatient service utilization in the previous month, compared to the month before. nearly half of the backlogs during the pandemic were related to routine preventive services such as annual check-ups antenatal care, and childhood immunization (55.0% for hospitals, and 45.7% for clinics). prioritizing high risk patients (86.7%), promoting self-care interventions wherever appropriate (75.0%), redirecting patients to alternative healthcare facilities (73.3%), providing all care in a single visit for multiple morbidities (60.0%), and providing home-based care for certain patients (58.3%) in hospitals. However, the most used strategies in clinics were prioritizing high risk patients (93.3%), redirecting patients to alternative healthcare facilities (75.2%), and providing home-based care for certain patients (66.7%).

Conclusion

The pandemic exacerbated existing health inequities and hindered progress toward Universal Health Coverage (UHC). Health facilities employed various strategies to cope with the disruptions, such as prioritizing high-risk patients, promoting self-care, and redirecting patients to alternative facilities. However, the increased cost of transportation and health services, along with limited availability of medicines, remained significant barriers to healthcare access.

Keywords: COVID-19 pandemic, Primary health care, Rural settings, Changes in utilization of health services, Afghanistan

Introduction

Afghanistan is a low-income country with a Human Development Index (HDI) value 0.478. In 2021, it ranked 180th among 191 countries and territories worldwide [1]. During the last two decades, significant progress has been made in coverage of essential health services in Afghanistan (an increase in coverage index from 23 in 2000 to 42 in 2019) [2]. The backbone of Afghanistan’s health system is Basic Package of Health Services and Essential Package of Hospital Services [3]. The Basic Package of Health Services (BPHS) started in 2003 and focuses on primary care, including maternal and newborn health, child health and immunization, public nutrition, communicable diseases, mental health, disability, and regular supply of essential drugs [4]. The second package, the Essential Package of Hospital Services (EPHS), started in 2005 and includes secondary and partially tertiary care in Afghanistan [5]. Many studies show significant progress toward service coverage and access to different essential health services within Afghanistan [6–10]. However, the COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted the provision and utilization of health services in many developed and developing countries [11].

The COVID-19 pandemic has affected many sectors, specifically fragile health systems in Low- and Middle-Income Countries (LMICs). It posed widespread challenges on all levels of health service delivery, especially during early times due to the steady spread of the virus within the continents [7]. As of July 2024, the World Health Organization (WHO) reported nearly 776 million confirmed cases and over seven million deaths globally from which over 23 million cases and 351 thousand deaths reported from the Eastern Mediterranean Region [12]. There are pieces of evidence that the COVID-19 pandemic has affected progress toward achieving Universal Health Coverage (UHC) globally [13–18]. However, how much the pandemic has affected the basic and essential health services in Afghanistan during its peak months has yet to be studied. Afghanistan experienced several waves (six main peaks) of COVID-19 cases from February 2020 to February 2023. The first major peak occurred in mid-2020, with a surge in cases and deaths reported in June and July 2020 [13]. The second peak was observed in December 2020- January 2021. However, the notable wave was in June-July 2021 (Delta variant), when the country recorded its highest daily number of cases [14]. The highest mortality rates were seen during these peaks, particularly affecting older adults and those with pre-existing conditions. The healthcare system, already strained by ongoing conflicts and limited resources, faced immense challenges in managing these surges [15]. Despite efforts to control the spread, including lockdowns and vaccination campaigns, the pandemic’s impact was profound, exacerbating existing health and socio-economic issues [16]. The fourth peak was during December 2021-January 2022 (Omicron variant), the fifth peak was observed in June 2022 and the sixth peak was in January 2023 [17, 18].

Despite imposing several restrictions on population movement and gathering and implementation of lockdowns, the country still experienced these waves mainly due to poor diagnostic and treatment capacity. The shortage of diagnostic kits, inadequate number of diagnostic centers, high cost of diagnosis in private sector, lack of kit production inside the country, shortage of trained laboratory staff and inadequate of safe and standard vehicles for transporting diagnostic kits are the main gaps. In addition, serious shortage of trained healthcare workers, facilities and equipment hindered provision of proper treatment for COVID-19 patients [19, 20].

In this national cross-sectional survey, we, we aim to explore the changes and backlogs in providing and utilizing essential health services during the pandemic (Feb 2020 to Sep 2022) in Afghanistan.

Methods

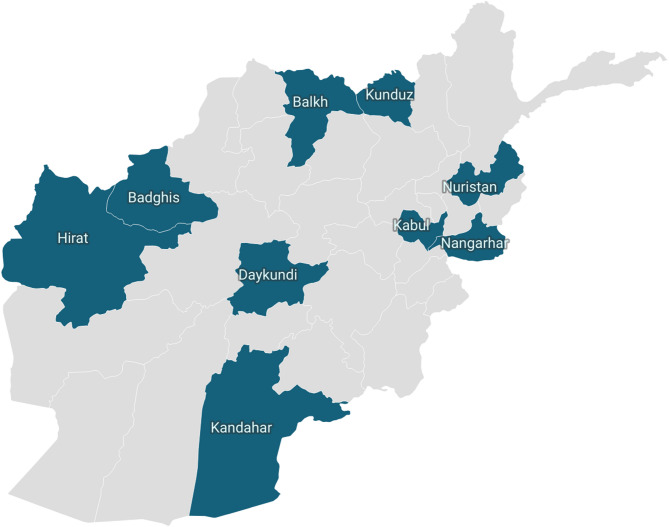

We conducted a cross-sectional study of health facilities in nine provinces of Afghanistan, including Kabul, Nangarhar, Herat, Kandahar, Balkh, Daykondi, Nooristan, Kunduz, and Badghis (Fig. 1). Altogether, these nine provinces included 49% of the total population in 2020 [21]. The tool, service readiness for COVID-19 case management and essential health service provision [22, 23], can be used by countries to rapidly assess the capacity of health services during the pandemic. The tool aims to help alert the authorities and other stakeholders about where provision and utilization of COVID-19 and essential health services may require modification and/or investment. It can be used once to provide a rapid snapshot of status, or on a regular basis for tracking and monitoring the service readiness during the different phases of the pandemic. In Afghanistan, it is the second round of this survey, the first round was implemented in five zone provinces (Kabul, Nangarhar, Kandahar, Herat, Balkh) during the February 2022. The questionnaire for this survey was developed by the WHO Headquarters and modified for the local setting of the Afghanistan health system by the WHO Afghanistan country office. Then, the questionnaire was validated by national experts in a national workshop in January 2022. Before the first round of the survey, the tool was piloted. The questionnaire was not translated into local language, as the interviewers were proficient in both English and local languages (Dari and Pashto).

Fig. 1.

Selected provinces in Afghanistan for the survey

We used two-stage random sampling to select a representative sample of healthcare centers and hospitals in the nine provinces. In first stage, we randomly selected 49 (out of 130) districts in these nine provinces using PPS (Probability-Proportional-to-Size Sampling). To select health facilities, we used a comprehensive sample frame of public facilities with exact location addresses provided by Ministry of Public health. Unfortunately, there was not such sampling framework for private health facilities. So, we included all private health facilities located in the selected districts of the province. We obtained the list and address of these private health facilities from Provincial Public Health Department (PPHDs) of these provinces. Having a combined framework for public and private health facilities, 165 (out of 300) primary public health care centers and hospitals randomly were selected in the selected districts. We excluded facilities that were specifically designated to provide COVID-19 care at the time of study. However, one question was about if the facility has been ever designated to COVID-19 care during the pandemic. Data collection was completed from 14 to 23 September 2022 simultaneously in all selected provinces, and the facility managers were asked to report on disruptions in service provision and changes in service delivery strategies.

Trained staff met in person with the facility managers and completed the questionnaire by individual interviews during September 2022. The responses were entered electronically using the offline Lime Survey application [24] and uploaded to a secure database. The questionnaire had 253 questions and took an average of 80 min to complete. In this paper, we present the findings for the following sections: staffing, and delivery and utilization of essential health services, which includes 59 questions.

Data were exported into Excel, cleaned the raw data by removing inconsistencies, repetition, and data entry errors, and then exported into and analyzed using STATA version 17. We calculated the frequency distribution of characteristics of facilities and responses to questions.

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ministry of Public Health institutional review board (IRB Code No: A.0122.0389). Verbal informed consent was obtained from each facility manager who was interviewed. They were told that participation is voluntary, and they can leave the interview any time they would like.

Results

We enrolled managers from 165 public and private health facilities in nine provinces of Afghanistan. We analyzed the data disaggregated by type of health facilities (hospital and health clinics). The majority of health clinics were in rural areas (n = 74, 71.1%), while 35 (65%) of hospitals located in urban setting. Most of health facilities was managed by government/NGOs (n = 46, 76.6% of hospitals and n = 89, 84.7% of clinics). 17 (28.3%) hospitals were designated as a COVID-19 center during the pandemic. The average number of medical doctors, nurse, and midwives are (24.6, 25.5, and 7.7 respectively) for hospitals. An average of 105 (89%) out of 118 averaged total staff received at least one dose of COVID-19 vaccine in hospitals and an average of 13(81.0%) out of 15.7 total averaged number of staff received one dose of COVID-19 vaccines in clinics. 38 (63.3%) hospitals and 60 (57.1%) clinics received training for COVID-19 topics in the previous year (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of health care facilities assessed in Sep 2022, Afghanistan (N = 165)

| Characteristics | Hospitals (N = 60) | Clinics (N = 105) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |

| Facility Location | ||||

| Rural | 21 | 35 | 74 | 71.1 |

| Urban | 39 | 65 | 30 | 28.8 |

| Managing authority | ||||

| Government/NGO | 46 | 76.6 | 89 | 84.7 |

| Private for profit | 14 | 23.3 | 16 | 15.2 |

| A designated COVID-19 center during the pandemic | ||||

| Yes | 17 | 28.3 | 4 | 3.8 |

| staffing, new infection, vaccination | ||||

| Average number of staff per facility (Mean, SD) | 118.0 | 180.0 | 16.0 | 7 |

| Total number of medical doctor (Mean, SD) | 24.6 | 54.2 | 1.3 | 1.5 |

| Total number of nurse (Mean, SD) | 25.5 | 54.3 | 1.5 | 1.2 |

| Total number of midwives (Mean, SD) | 7.7 | 14.7 | 1.4 | 0.8 |

| Average number of staff who received COVID-19 vaccine (at least one dose) | 105 | 89.0 | 13 | 81.2 |

| Staff who were on leave or absent in the previous one week due to reasons related to COVID-19 (Mean, SD) | 1.1 | 2.1 | 0.1 | 0.4 |

| Training and supportive supervision for COVID-19 topics | ||||

| Facilities received training related to COVID-19 for their staff in the previous one year | 38.0 | 63.3 | 60 | 57.1 |

| Proper use of personal protective equipment (PPE) | 37.0 | 97.4 | 46 | 78 |

| Environmental cleaning and disinfection | 36 | 94.7 | 51 | 85 |

| Screening of COVID-19 signs and symptoms at the point of first presentation | 29 | 78.4 | 46 | 76.7 |

| Hand hygiene | 33 | 86.8 | 52 | 88.1 |

| Prioritizing patients on arrival using a triage tool | 34 | 89.5 | 45 | 75 |

| Management of emergency conditions such as difficulty in breathing, shock, and altered mental status | 31 | 83.8 | 36 | 60 |

| Provision of remote healthcare such as telemedicine | 22 | 57.9 | 29 | 48.3 |

| Facilities received supportive supervision related to COVID-19 in the previous one year | 29 | 48.3 | 60 | 57.1 |

Outpatient service utilization

27 (46.5%) of hospitals and 44 (41.9%) of clinics reported that they experienced a higher overall outpatient service utilization in the previous month, compared to the month before. The factors that may be associated with the higher number of outpatient visits are typical increase in other infectious disease because of changing seasons or weather (28.3%), more patients presenting with acute respiratory infection symptoms (21.7%), more patients being redirected from other facilities (18.3%), and general health communication campaigns to promote care seeking (10.0%) for hospitals. For clinics, the main reasons were seasonal increase in other infectious diseases (31.4%), more patients presenting with acute respiratory infection symptoms (18.1%), and general health communication campaign to promote care-seeking (12.4%). Potential factors for the lower number of OPD visits were increased cost for transportation (11.7%) and increased cost for health services (10.0%) for hospitals. While the main reason for clinics was seasonal decrease in other infectious diseases because of changing seasons or weather (14.3%), changes in recommendation to the public for mild illness and elective care (7.6%) and limited availability of medicines or consumables (7.6%) in the clinics (Table 2).

Table 2.

Changes in utilization and provision of essential health services and its reason in assessed health facilities, Sep 2022, Afghanistan (N = 165)

| Changes | Hospitals (N = 60) | Clinics (N = 105) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |

| Outpatient service utilization | ||||

| Higher | 27.0 | 46.5 | 44 | 41.9 |

| Similar | 16.0 | 27.6 | 37 | 35.2 |

| Lower | 15.0 | 25.8 | 24 | 22.8 |

| Potential reasons for the lower number of outpatient visits in the previous one month, compared to the month before | ||||

| Decrease in COVID-19 transmission | 3 | 5.0 | 7 | 6.6 |

| Typical decrease in other infectious diseases because of changing seasons or weather | 5 | 8.3 | 15 | 14.3 |

| Changes in recommendation to the public for mild illness and elective care | 3 | 5.0 | 8 | 7.6 |

| Fear, mistrust, uncertainty about catching COVID-19 during facility visits | 1 | 1.7 | 0 | 0 |

| Lockdown or stay at home order | 2 | 3.3 | 6 | 5.7 |

| Disruption of public transport | 2 | 3.3 | 6 | 5.7 |

| Increased cost for transportation | 7 | 11.7 | 5 | 4.7 |

| Scope of specific services reduced | 1 | 1.7 | 2 | 1.9 |

| Provision of specific services completely suspended | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0 |

| Reduced or changed opening hours | 1 | 1.7 | 1 | 0.9 |

| Facility closure | 1 | 1.7 | 1 | 0.9 |

| Limited availability of medicines or consumables | 0 | 0.0 | 8 | 7.6 |

| Limited availability of medical staff | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 1.9 |

| Long waiting hours at facility | 4 | 6.7 | 1 | 0.9 |

| Increased cost for health services | 6 | 10.0 | 4 | 3.8 |

| Potential reasons for the higher number of outpatient visits in the previous one month, compared to the month before | ||||

| More patients presenting with acute respiratory infection symptoms | 13 | 21.7 | 19 | 18.1 |

| Typical increase in other infectious diseases because of changing seasons or weather | 17 | 28.3 | 33 | 31.4 |

| More clients presenting with GBV related issues | 2 | 3.3 | 3 | 2.8 |

| More patients being redirected from other facilities | 11 | 18.3 | 5 | 4.7 |

| Backlog from disruptions of services prior to the past month | 2 | 3.3 | 3 | 2.8 |

| Communication to the public about reactivation of any services that were previously suspended or reduced | 3 | 5.0 | 6 | 5.7 |

| General health communications campaign to promote care-seeking | 6 | 10.0 | 13 | 12.4 |

| Community outreach or home visits | ||||

| Immunization outreach (n = 89) | ||||

| Higher | 7 | 11.7 | 18 | 17.1 |

| Similar | 2 | 3.3 | 22 | 20.9 |

| Lower | 13 | 21.7 | 29 | 27.6 |

| Malaria prevention campaigns, including distribution of insecticide-treated nets (n = 55) | ||||

| Higher | 1 | 1.6 | 4 | 3.8 |

| Similar | 9 | 15.0 | 42 | 40 |

| Lower | 13 | 21.6 | 23 | 21.9 |

| Neglected tropical disease outreach activities, including mass drug administration (n = 56) | ||||

| Higher | 1 | 1.6 | 5 | 4.7 |

| Similar | 9 | 15 | 45 | 42.8 |

| Lower | 13 | 21.6 | 19 | 18.1 |

| Community -based mobile clinics (n = 51) | ||||

| Higher | 4 | 6.6 | 8 | 7.6 |

| Similar | 6 | 10.0 | 45 | 42.8 |

| Lower | 13 | 21.6 | 16 | 15.2 |

| Home visits (n = 86) | ||||

| Higher | 5 | 8.3 | 18 | 17.1 |

| Similar | 5 | 8.3 | 23 | 21.9 |

| Lower | 13 | 21.6 | 28 | 26.6 |

Community outreach or home visits

Facility mangers were asked about changes in frequency of outreach services in the previous month, compared to the same one month last year. Most facilities reported a decrease in immunization outreach (13 (21.7%) of hospitals and 29 (27.6%) of clinics), malaria prevention campaigns (13 (21.6%) of hospitals and 23(21.9%) of clinics), neglected tropical disease outreach activities (13 (21.6%) of hospitals), community-based mobile clinics (13 (21.6%) of hospitals, and home visits (13 (21.6%) of hospitals, and 28 (26.6%) of clinics). However, 45 (42.8%) of clinics reported similar activities for neglected tropical disease outreach activities, as well as community-based mobile clinics (n = 45,42.8%) (Table 2).

Table 3 presented backlog per services in assessed health facilities. We defined backlog for interviewees as following: “During the COVID-19 pandemic, sometimes, facilities have not been able to provide certain outpatient services as usual. In some facilities, that have resulted in backlogs of patients who wait for their turns. Since the start of the pandemic, has this facility ever had backlogs related to the COVID-19 pandemic in the following type of services?”. As presented (Table 3), nearly half of the backlogs during the pandemic were related to routine preventive services such as annual check-ups antenatal care, and childhood immunization (55.0% for hospitals, and 45.7% for clinics). In addition to this, the most backlogged services during the pandemic were those for non-communicable diseases (43.3% for hospitals and 44.7% for clinics), and TB and HIV/AIDS (41.7% for hospitals, and 37.1% for clinics).

Table 3.

Backlog per services in assessed health facilities during the pandemic, Sep 2022, Afghanistan (N = 165)

| Backlog per services | Hospitals (N = 60) | Clinics (N = 105) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |

| During the pandemic | ||||

| Routine preventive services such as annual check-ups, antenatal care, childhood immunization | 33 | 55.0 | 48 | 45.7 |

| Management of non-communicable diseases | 26 | 43.3 | 47 | 44.7 |

| Management of infectious diseases such as TB and HIV/AIDS | 25 | 41.7 | 39 | 37.1 |

| Elective surgeries or procedures | 26 | 43.3 | 14 | 13.3 |

| During last month (Aug-Sep 2022) | ||||

| Routine preventive services such as annual check-ups, antenatal care, childhood immunization | 29 | 48.3 | 40 | 38.1 |

| Management of non-communicable diseases | 23 | 38.3 | 41 | 39 |

| Management of infectious diseases such as TB and HIV/AIDS | 23 | 38.3 | 35 | 33.3 |

| Elective surgeries or procedures | 24 | 40 | 15 | 14.3 |

Table 4 shows the strategies used by the health facilities for safe and continued delivery of services during the pandemic. The interviewees were asked the following question: “now I am going to ask you about services that are unrelated to COVID-19. During the pandemic, some facilities have provided services differently at times. Has the facility done any of the following ever during the pandemic?.

Table 4.

Strategies used for safe and continued delivery of services during the pandemic, Sep 2022, Afghanistan (N = 165)

| Strategies | Hospitals (N = 60) | Clinics (N = 105) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |

| Reduced the scope of specific services | 31 | 51.6 | 53 | 50.5 |

| Reduced the volume of specific services | 17 | 28.3 | 24 | 22.9 |

| Suspended the provision of specific services | 25 | 41.7 | 36 | 34.3 |

| Redirected patients to alternative healthcare facilities | 44 | 73.3 | 79 | 75.2 |

| Given priority to seeing high-risk patients | 52 | 86.7 | 98 | 93.3 |

| Provided all care in a single visit for multiple morbidities | 36 | 60.0 | 66 | 62.9 |

| Supported self-care interventions wherever appropriate | 45 | 75.0 | 84 | 80 |

| Provided home-based care for certain patients | 35 | 58.3 | 70 | 66.7 |

| Shifted clinical encounters to digital platforms such as teleconsultations | 29 | 48.3 | 39 | 37.1 |

| Provided electronic or tele prescriptions | 27 | 45.0 | 40 | 38.1 |

| Extended prescriptions of medicines for long-term use, such as medicines for treating non-communicable diseases | 38 | 63.3 | 50 | 47.6 |

| Used novel dispensing approaches for medicines | 30 | 50.0 | 44 | 41.9 |

These strategies were prioritizing high risk patients (86.7%), promoting self-care interventions wherever appropriate (75.0%), redirecting patients to alternative healthcare facilities (73.3%), providing all care in a single visit for multiple morbidities (60.0%), and providing home-based care for certain patients (58.3%) in hospitals. However, the most used strategies in clinics were prioritizing high risk patients (93.3%), redirecting patients to alternative healthcare facilities (75.2%), and providing home-based care for certain patients (66.7%).

Discussion

In our study, most of hospitals located in urban setting and managed by government/NGOs. At the time of the survey, we found that nearly one third of hospitals were repurposed as COVID-19 center during the pandemic. More than half of the hospitals and clinics received training for COVID-19 topics in the previous year and almost 90% of staff in hospitals and clinics received at least one dose of COVID-19 vaccine. Health facilities experienced a higher level of outpatient service utilization after the pandemic peak, mainly due to seasonal non-COVID-19 infections (other infectious diseases that are diagnosed at facility level) and more frequent acute respiratory infection symptoms. Meanwhile, the main reason for the lower number of OPD visits at hospitals were increased transportation cost and increased cost for health services, while the main reason for lower number of OPD visits were decrease in seasonal infectious diseases, changes in recommendation to the public for mild illness and elective care and limited availability of medicine or consumables in the clinics. However, most health facilities reported a decrease in community-based outreach programs. Health facilities used strategies such as prioritizing high-risk patients, promoting self-care interventions, and redirecting patients to other health facilities to respond to these fluctuations.

The COVID-19 pandemic disrupted the delivery of essential healthcare services worldwide. This effect was worse in countries with fragile health systems and existing health inequities. The pandemic also affected the achievement of universal access to healthcare and provision of equal opportunities for healthcare utilization for all populations [25]. As a global movement toward Universal Health Coverage (UHC), Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 3.8 target focuses on this concept. This target is measured using two metrics: SDG indicator 3.8.1 on the coverage of essential health services and SDG indicator 3.8.2 on catastrophic health spending.

In this study, we found that the most reported backlogs were for routine essential health services such as antenatal care, childhood immunization, and management of communicable and non-communicable diseases. The backlogs were reported higher in hospitals comparing to clinics. It may be due to not considering the referral pathway by Afghan population, as they directly seek diagnosis and treatment services from hospitals. The results of a study conducted jointly by WHO/Europe, the European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, and the Nuffield Trust in 2022 show that backlog and delays in non-emergency health care have stretched the health system and left many people without care [26]. A study in Iran showed that after an initial significant reduction of hospitalization rate, emergency department visits and outpatient visits in the first month of COVID-19 outbreak, significant monthly increases were observed in these three areas during the COVID-19 pandemic [27].

Many health facilities in Afghanistan implemented several strategies to maintain the delivery of their essential services during the COVID-19 pandemic. These strategies were prioritizing high-risk patients, redirecting patients to alternative healthcare facilities, and providing home-based care to certain patients in both hospitals and clinics and promoting self-care in both hospitals and clinics. While we have yet to find any study on the effectiveness of these strategies, we recommend program managers and service providers assess the efficacy of these strategies at the facility, provincial, and national levels. A study in India showed that to maintain service provision, home-based services increased, and use of PPE, telephones for communication and applying social distancing have been increased [28].

Responding to backlogs, especially for essential health services, and delivering alternative strategies to maintain the health services must strengthen the health system focusing on the health workforce. Coates et al. (2021) framework suggested three types of interventions to increase health workforce capacity during a pandemic: (1) increase the numbers of health workers; (2) improve the skills of the health workforce by increasing the scope of work and their flexibility; (3) increase the support required in terms of medicine and supply to increase the sustainability of service provision [29]. Some of good initiatives to train and deploy health workforce during the pandemic in Afghanistan include training doctors and nurses in Rapid Response Teams (RRTs) and Contact Tracing teams and deploying them to the borders to detect and treat the suspected cases, train and deploy home-based care teams (a team of one doctor and one nurse) to provide diagnosis and treatment for mild and moderate cases of COVID-19 at their homes, training lab technicians on COVID-19 rapid and PCR tests and deploying them to 6 regional lab centers across the country, establishing COVID-19 treatment centers and training the health workforce on using PPE, social distancing, infection prevention, diagnosis and treatment of COVID-19 patients [30, 31]. In 2023, Afghanistan has a density of 10.3 doctors, nurses, and midwives per 10,000 population [32]. It was much lower than the minimum threshold density recommended by WHO, which is 44.5 doctors, nurses, and midwives per 10,000 [33]. Afghanistan needs to train more students to become doctors, nurses, or midwives to cover this gap in its workforce. Training more women to hold doctor, nurse and midwifery jobs is critical for Afghanistan’s health system, considering the cultural barriers in Afghan community. This should consider geographical balance throughout the country as well.

In addition, we found that health facilities decreased their community outreach healthcare services during the pandemic. Other studies also showed challenges in providing community-based healthcare services during the COVID-19 pandemic [34, 35]. One alternative could be promoting self-care among the population. Self-care can be used for the prevention or management of non-communicable and communicable diseases, mental health, and sexual and reproductive health [36–38].

One of the main findings of our study is that the main potential reason for the low utilization of health services is the increased cost of transportation and health services at hospital level. Although there is evidence of high Out-of-pocket payments in Afghanistan, more than 70% during the recent decade [39], this finding is also worth considering. The need for a sustainable health financing system aimed at decreasing the OOP and catastrophic cost of healthcare has always been a concern for Afghanistan [40] which was never achieved due to political instability in this country. The regime changes in 2021 and suspension of donor funding to the health system deteriorated the situation more [41]. The findings of our study also showed that one of the main reasons of low utilization of health services at clinic level was limited availability of medicines and consumables. The findings from different studies especially after 2021 are consistent with the result of our study [42, 43]. A qualitative study during 2022 using in-depth interviews with 43 health workers in ten provinces of Afghanistan also showed that the main barriers to achieving UHC in Afghanistan are severe shortages of facilities, equipment, workers and medications at facility levels especially at rural areas. The study also highlighted that the quality of available medications is under question too [44]. A study in Pakistan also showed that the main barriers to care-seeking were stockouts and lack of supplies at facility level [45].

Our study had five main limitations. First, our data on changes in the services were based on the survey with health facility managers, but not on the actual utilization record. So, it includes first, recall bias in terms of response of facility managers about service delivery for the past month or the past year. Second, as the facility managers were not the actual beneficiary of the services with real experience, they might not provide a response based on what was real in health facilities. The third limitation is that we did not collect patients’ perspectives and reasons for less access to health services during the COVID-19 pandemic and we presented the reasons based on the responses of facility managers’ perception which can be differ from patients’ perspective. To our knowledge, we could not find any population or patient- based study focusing on service delivery assessment during the pandemic. Fourth, under the scope of our study, we could not explore the influence of reduced community activities on preventive care such as vaccination or curative care for communicable and non-communicable diseases. Future qualitative studies are recommended to explore this aspect.

fifth, our study did not examine the link between using the coping mechanisms and the increased service utilization rate. In addition, we did not explore whether the coping mechanisms have been applied to the period of COVID outbreak or rather for period before and after the pandemic. We recommend future studies to explore any possible association in health facilities.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic has significantly disrupted essential healthcare services worldwide, particularly in countries with fragile health systems like Afghanistan. Our study highlights the challenges faced by health facilities, including increased outpatient service utilization due to non-COVID-19 infections and decreased community-based outreach programs. The pandemic exacerbated existing health inequities and hindered progress toward Universal Health Coverage (UHC). Health facilities employed various strategies to cope with the disruptions, such as prioritizing high-risk patients, promoting self-care, and redirecting patients to alternative facilities. However, the increased cost of transportation and health services, along with limited availability of medicines, remained significant barriers to healthcare access. The study underscores the need for sustainable health financing, training more healthcare workers, especially women, and assessing the effectiveness of coping strategies. Future studies should explore patients’ perspectives and the impact of reduced community activities on preventive care. Addressing these challenges is crucial for strengthening Afghanistan’s health system and achieving UHC. International donors are recommended to support establishing a resilient health system with sustainable financing mechanism in Afghanistan. Due to two main limitations of our study, we recommend further studies on the effectiveness of coping mechanisms on maintaining provision of essential health services and utilization of essential health services based on facility records and patient perspective.

Acknowledgements

For this paper, we wish to acknowledge the support from the University of California, San Francisco’s International Traineeships in AIDS Prevention Studies (ITAPS), U.S. NIMH, R25 MH064712.

Abbreviations

- HDI

Human Development Index

- BPHS

Basic Package of Health Services

- EPHS

Essential Package of Hospital Services

- LMICs

Low ad Middle Income Countries

- WHO

World Health Organization

- UHC

Universal Health Coverage

- OPD

Outpatient Department

- TB

Tuberculosis

- HIV

Human Immune deficiency Virus

- AIDS

Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome

Authors’ contributions

NN and AM designed the study or analysis plan. NN and AI led the data collection, NN and AM analyzed the data. NN wrote the manuscript. AI, AA, and JT reviewed the manuscript and contributed to its enrichment. All authors reviewed the manuscript and approved the final version.

Funding

The survey was funded by the World Health Organization.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available as the informed consent applied only for the use by the research team. If desired, the data can be viewed and reviewed together with the corresponding author.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ministry of Public Health institutional review board (IRB Code No: A.0122.0389). Verbal informed consent was obtained from each facility manager who was interviewed. They were told that participation is voluntary, and they can leave the interview any time they would like.

Consent for publication

Not Applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.United Nations for Development Program. Human Development Reports 2021. https://hdr.undp.org/data-center/country-insights#/ranks. Accessed 01 Nov 2023.

- 2.The World Bank. SDG 3.8.1 Coverage of essential health service. https://databank.worldbank.org/embed/SDG-3.8.1-Coverage-of-essential-health-services/id/f609d4b. Accessed 01 Nov 2023.

- 3.World Health Organization. Afghanistan Health System. https://www.emro.who.int/afg/programmes/health-system-strengthening.html#:~:text=Afghanistan’s%20health%20system%20has%20been,population%20within%20two%20hours%20distance. Accessed 01 Nov 2023.

- 4.Newbrander W, Ickx P, Feroz F, Stanekzai H. Afghanistan’s basic package of health services: its development and effects on rebuilding the health system. Glob Public Health. 2014. 10.1080/17441692.2014.916735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Afghanistan Ministry of Public health. Essential Package of Hospital Services 2005. https://platform.who.int/docs/default-source/mca-documents/policy-documents/guideline/afg-cc-46-01-guideline-2005-eng-essential-hospital-services.pdf. Accessed 01 Nov 2023.

- 6.Kim YM, Zainullah P, Mungia J, Tappis H, Bartlett L, Zaka N. Availability and quality of emergency obstetric and neonatal care services in Afghanistan. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2012. 10.1016/j.ijgo.2011.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Edward A, Branchini C, Aitken I, Roach M, Osei-Bonsu K, Arwal SH. Toward universal coverage in afghanistan: A multi-stakeholder assessment of capacity investments in the community health worker system. Soc Sci Med. 2015. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Akseer N, Bhatti Z, Rizvi A, Salehi AS, Mashal T, Bhutta ZA. Coverage and inequalities in maternal and child health interventions in Afghanistan. BMC Public Health. 2016. 10.1186/s12889-016-3406-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mbaeyi C, Kamawal NS, Porter KA, Azizi AK, Sadaat I, Hadler S, Ehrhardt D. Routine immunization service delivery through the basic package of health services program in afghanistan: gaps, challenges, and opportunities. J Infect Dis. 2017. 10.1093/infdis/jiw549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Howard N, Woodward A, Patel D, Shafi A, Oddy L, Veen A, et al. Perspectives on reproductive healthcare delivered through a basic package of health services in afghanistan: a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014. 10.1186/1472-6963-14-359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Health Organization. Third round of the global pulse survey on continuity of essential health services during the COVID-19 pandemic. 2021. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-EHS_continuity-survey-2022.1. Accessed 02 Nov 2023.

- 12.World Health Organization. WHO COVID-19 dashboard. https://data.who.int/dashboards/covid19/deaths?n=o&m49=957. Accessed 13 Aug 2024.

- 13.Haileamlak A. The impact of COVID-19 on health and health systems. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2021. 10.4314/ejhs.v31i6.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saengtabtim K, Tang J, Leelawat N, Egawa S, Suppasri A, Imamura F. Universal health coverage mitigated COVID-19 health-related consequences in Asia Oceania. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct. 2023. 10.1016/j.ijdrr.2023.103725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mao W, Ogbuoji O, Watkins D, Bharali I, Nsiah-Boateng E, Diab MM, et al. Achieving global mortality reduction targets and universal health coverage: the impact of COVID-19. PLoS Med. 2021. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Al-Awlaqi S, Dureab F, Annuzaili D, Al-Dheeb N. COVID-19 in conflict: the devastating impact of withdrawing humanitarian support on universal health coverage in Yemen. Public Health Pract (Oxf). 2020. 10.1016/j.puhip.2020.100015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nguyen Thu H, Nguyen Quynh A, Khuat Hai O, Le Thi Thanh H, Nguyen Thanh H. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on provision of HIV/AIDS services for key populations. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2022. 10.1002/hpm.3508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cuschieri S, Grech E, Gatt A, Cutajar A, Vassallo C, Zahra D, et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mediterranean region over 18 months: bridging the health outcomes and sustainable development goals. Afr Health Sci. 2022. 10.4314/ahs.v22i4.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mousavi SH, Abdi M, Zahid SU, Wardak K. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in afghanistan: measures and challenges. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2021;42(3):366–7. 10.1017/ice.2020.240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Essar MY, Hasan MM, Islam Z, Aeel Riaz MM, Aborode AT, Ahmad Sh. COVID-19 and multiple crises in afghanistan: an urgent battle. Confl Health 2021; 15(70). 10.1186/s13031-021-00406-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Amimo F, Lambert B, Magit A, Hashizume M. A review of prospective pathways and impacts of COVID-19 on the accessibility, safety, quality, and affordability of essential medicines and vaccines for universal health coverage in Africa. Global Health. 2021. 10.1186/s12992-021-00666-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. The World Bank. Afghanistan Province Dashboard. https://www.worldbank.org/en/data/interactive/2019/08/01/afghanistan-interactive-province-level-visualization. Accessed 03 Nov 2023.

- 23.World Health Organization. Monitoring frontline service readiness capacities during the COVID-19 pandemic. https://www.who.int/teams/integrated-health-services/health-services-performance-assessment/monitoring-health-services/monitoring-frontline-service-readiness-capacities-during-the-covid-19-pandemic. Accessed 03 Nov 2023.

- 24.Neyazi N, Lindan C, Perdes S, Ibrahimi AG, Horemans D, Al Afsoor D. The provision and utilization of essential health services in Afghanistan during COVID-19 pandemic. Front Public Health. 2023. 10.3389/fpubh.2022.1097680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Limesurvey Organization. English Support Forum. https://forums.limesurvey.org/forum/can-i-do-this-with-limesurvey/59814-offline-surveys. Accessed 03 Nov 2023.

- 26.Hussain R, Arif S. Universal health coverage and COVID-19: recent developments and implications. J Pharm Policy Pract. 2021. 10.1186/s40545-021-00306-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mahmoodpour-Azari M, Rezaei S, Badiee N, Hajizadeh M, Mohammadi A, Kazemi-Karyani A, et al. The COVID-19 pandemic and healthcare utilization in iran: evidence from an interrupted time series analysis. Osong Public Health Res Perspect. 2023;14(3):180–7. 10.24171/j.phrp.2023.0041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Phuong HN, Shivani K, Anjali P, Lan MT, Monika W, Sebanti G, et al. COVID-19 disrupted provision and utilization of health and nutrition services in Uttar pradesh, india: insights from service providers, Houshold phone surveys, and administrative data. J Nutr. 2021;151(8):2305–16. 10.1093/jn/nxab135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.European observatory on health systems and policies. Addressing backlogs and managing waiting lists during and beyond the COVID-19 pandemic. 2022. https://www.who.int/europe/news/item/20-07-2022-covid-19-has-caused-major-disruptions-and-backlogs-in-health-care--new-who-study-finds. Accessed 20 Nov 2023. [PubMed]

- 30.Lucero-Prisno DE 3rd, Ahmadi A, Essar MY, Lin X, Adebisi YA. Addressing COVID-19 in afghanistan: what are the efforts and challenges? J Glob Health. 2020;10(2):020341. 10.7189/jogh.10.020341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yen MY, Schwartz J, King CC, Lee CM, Hsueh PR. Society of Taiwan Long-term care infection prevention and control. Recommendations for protecting against and mitigating the COVID-19 pandemic in long-term care facilities. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2020;53(3):447–53. 10.1016/j.jmii.2020.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Coates A, Fuad AO, Hodgson A, Bourgeault IL. Health workforce strategies in response to major health events: a rapid scoping review with lessons learned for the response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Hum Resour Health. 2021. 10.1186/s12960-021-00698-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Neyazi N, Yaghmaei N, Ahmadzai M, Kleipool E, Naumann N, Wassenaar M, Omar MH, Gedik FG, Alba S, Dieleman M, Ibrahimi AG, AbouZeid A. Assessing the health workforce in Afghanistan: a situational analysis into the country’s capacity for Universal health coverage. Confl Health. 2025;19(1):25. 10.1186/s13031-025-00663-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.World Health Organization. Global strategy on human resources for health: workforce 2030. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241511131. Accessed 30 Nov 2023.

- 35.O’Sullivan B. Challenges and innovations in access to community-based rural primary care services during the Covid-19 pandemic in Australia. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2022. 10.1002/hpm.3598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mahoney KJ. Self-Direction of home and Community-Based services in the time of COVID-19. J Gerontol Soc Work. 2020. 10.1080/01634372.2020.1774833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Narasimhan M, Aujla M, Van Lerberghe W. Self-care interventions and practices as essential approaches to strengthening health-care delivery. Lancet Glob Health. 2023. 10.1016/S2214-109X(22)00451-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Patel V, Chisholm D, Parikh R, Charlson FJ, Degenhardt L, Dua T, et al. Addressing the burden of mental, neurological, and substance use disorders: key messages from disease control priorities, 3rd edition. Lancet. 2016. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00390-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Riegel B, Moser DK, Buck HG, Dickson VV, Dunbar SB, Lee CS, et al. Self-Care for the prevention and management of cardiovascular disease and stroke: A scientific statement for healthcare professionals from the American heart association. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017. 10.1161/JAHA.117.006997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Afghanistan Ministry of Public Health. National Health Account report. 2019. https://extranet.who.int/countryplanningcycles/sites/default/files/planning_cycle_repository/afghanistan/afghanistan_national_health_accounts.pdf. Accessed 24 Nov 2023.

- 41.Higgins-Steele A, Farewar F, Ahmad F, Qadir A, Edmond K. Towards universal health coverage and sustainable financing in afghanistan: progress and challenges. J Glob Health. 2018. 10.7189/jogh.08.020308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Safi N, Anwari P, Safi H. Afghanistan’s health system under the Taliban: key challenges. The Lancet. 22;400(10359),1179–1180. 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01806-2 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 43.Roien R, Essar MY, Ahmadi A, Lucero-Prisno Iii DE, Yousefi AA, Hasan MM, et al. Challenges of drug supply: how Afghanistan is struggling. Public Health Pract (Oxf). 2021;2:100129. 10.1016/j.puhip.2021.100129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lamberti-Castronuovo A, Valente M, Bocchini F, Trentin M, Paschetto M, Bahdori GA, et al. Exploring barriers to access to care following the 2021 socio-political changes in afghanistan: a qualitative study. Confl Health. 2024;18(1):36. 10.1186/s13031-024-00595-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Paudel M, Leghari A, Ahmad AM, Gibbs S, Wheeler J, Goldberg S, et al. Understanding changes made to reproductive, maternal, newborn and child health services in Pakistan during the COVID-19 pandemic: a qualitative study. Sex Reproductive Health Matters. 2022;30(1). 10.1080/26410397.2022.2080167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available as the informed consent applied only for the use by the research team. If desired, the data can be viewed and reviewed together with the corresponding author.