Abstract

Background

Heart failure and atrial fibrillation (HF-AF) frequently coexist, resulting in complex interactions that substantially elevate mortality risk. This study aimed to develop and validate a machine learning (ML) model predicting the 3-year all-cause mortality risk in HF-AF patients to support personalized risk stratification and management.

Method

This retrospective cohort study included 558 HF-AF patients admitted in 2018, with a median follow-up duration of 1,185 days. The cohort was randomly divided into training (70%) and test (30%) sets. Feature selection utilized the Boruta algorithm and least absolute shrinkage and selection operator regression. Six ML models were trained using tenfold cross-validation and optimized via grid search. Model performance was evaluated across 12 metrics, including the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC), to identify the best-performing model. Subsequently, Shapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) analysis was used to interpret the optimal model and investigate interactions between features.

Results

Of the 558 patients, 215 reached the primary endpoint. Feature selection identified 14 key variables for model development. The best-performing model, CatBoost, achieved the highest AUC (0.809) and demonstrated robust performance across multiple evaluation metrics. SHAP analysis highlighted the New York Heart Association (NYHA) classification, absolute lymphocyte count (ALC), high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP), and age as key predictors. SHAP interaction analysis identified several feature interactions, with relatively strong ones observed between ALC and NYHA classification, and ALC and BNP.

Conclusions

CatBoost was identified as the optimal model for predicting three-year all-cause mortality in HF-AF patients, potentially aiding clinicians in risk stratification and individualized treatment planning to improve patient outcomes.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12872-025-04928-w.

Keywords: Machine learning, Heart failure, Atrial fibrillation, All-cause mortality, Prediction model

Introduction

Heart failure (HF) represents a major global public health challenge, with its prevalence increasing by 106.3% between 1990 and 2019 [1]. Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common persistent arrhythmia, affecting approximately 60 million people worldwide [2]. Nearly half of HF patients develop comorbid AF in advanced disease stages [3]. Individuals with AF have a 4.52-fold increased risk of developing HF compared to those without AF [4]. HF can facilitate AF development by inducing atrial remodeling and fibrosis. Conversely, AF-induced persistent tachycardia, irregular heart rate (HR), and ineffective atrial contractions can precipitate HF [5]. An analysis of data from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Wide-Ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research revealed a significant increase in HF-related mortality among patients with AF between 2011 and 2020. Furthermore, in 2020, the age-adjusted mortality rate reached 20.48 per 100,000 (95% CI: 20.34–20.62), representing a substantial rise from 8.15 per 100,000 (95% CI: 8.05–8.26) in 1999 [6].

HF and AF often exacerbate each other, establishing a vicious cycle that leads to poor prognosis and heavy socioeconomic burden on patients [7]. Jones et al. [8] conducted a population-based cohort study reporting that patients with HF-AF had a higher mortality risk than those with either condition alone. In a multicenter study of 929,552 participants, Ziff et al. [9] reported an all-cause mortality as high as 70.8% in patients with HF-AF. Therefore, developing prognostic risk prediction models is essential to assist clinicians in optimizing management and devising personalized treatment strategies for these patients.

Machine learning (ML) is a computational approach that uses data to train models, uncover latent patterns, and perform complex tasks [10]. Recently, ML has been widely used in the medical field [10], particularly in the area of cardiovascular diseases (CVDs). Numerous studies have investigated prognostic risk prediction in patients with either HF [11] or AF [12]. However, prognostic studies specifically targeting patients with comorbid HF and AF remain limited [13].

Therefore, developing prognostic risk prediction models for these patients is essential to support clinicians in optimizing disease management and formulating personalized treatment strategies. To address the “black box” problem of ML models, we employed the Shapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) method to interpret the best-performing model, thereby providing insight into the model’s influential features and their potential clinical implications for patients with HF-AF.

Methods

Study population

Patients with HF-AF admitted to the Department of Cardiovascular Medicine, First Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical University in 2018 were retrospectively analyzed in this study. Medical records were retrieved from the electronic system. The inclusion criteria for enrollment were as follows: 1) A diagnosis of HF based on the Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of HF in China 2018, which is contingent upon the presence of symptoms and/or signs of HF, N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide > 125 ng/L and/or BNP > 35 ng/L, evidence of abnormal cardiac structure and/or function, and classified as New York Heart Association (NYHA) classification of II-IV; 2) A prior diagnosis of AF, or documented evidence of AF on a standard 12-lead electrocardiogram, or 24- or 72-h Holter monitoring, or continuous inpatient ECG monitoring (details provided in the Supplementary Methods); and 3) multiple hospitalizations within one year, with only the most recent admission data included. The exclusion criteria were: 1) unstable vital signs or in-hospital death; 2) malignant tumors; 3) acute infections; and 4) missing data > 20%.

Data collection

We extracted the following data from patients’ medical records at the time of admission: age, sex, body mass index (BMI) (calculated as weight in kg divided by height in m2), history of tobacco and alcohol use, HR, and blood pressure (systolic and diastolic); comorbidities including hypertension, coronary artery disease, diabetes mellitus, dilated cardiomyopathy, hypertensive heart disease, peripheral arterial disease, hyperthyroidism, stroke, anemia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, history of bleeding, coronary stent implantation, cardiac valvuloplasty, and implantable cardioverter defibrillator implantation, and abnormal liver and renal function; medication history (statins, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin II receptor blockers, warfarin, novel oral anticoagulants, antiplatelet agents, beta-blockers, calcium channel blockers, and digoxin); NYHA classification; laboratory tests [leukocyte, hemoglobin, neutrophil, absolute lymphocyte count (ALC), uric acid, albumin (ALB), blood urea nitrogen (BUN), creatinine, international normalized ratio, activated partial thromboplastin time, D-dimer, lipids, BNP, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP), and glycosylated hemoglobin]; echocardiographic findings; length of stay (LOS); and duration of anticoagulation.

Patients were followed up through outpatient visits, rehospitalizations, and telephone interviews. All-cause mortality was defined as the primary endpoint. The median final follow-up duration was 1,185 days.

Statistical analysis

The random forest imputation method was applied to data with less than 20% missingness, in order of increasing proportions of missing values. This ensemble learning technique, which utilizes multiple decision trees, predicts and imputes missing values based on observed data [14]. Its ability to capture complex interactions and nonlinear relationships has made it a robust and widely used method for imputing missing values in medical datasets [15]. The imputed dataset was randomly split into training and test sets at a 7:3 ratio. Subsequently, normally distributed continuous variables were presented as the mean ± standard deviation, while non-normally distributed variables were summarized as the median (interquartile range). Categorical data were expressed as frequencies and percentages. For group comparisons of continuous variables, the independent samples t-test or Mann–Whitney U test was applied, with results presented as the mean ± standard deviation or median (interquartile range), respectively. Categorical variables were compared using the chi-squared test, Wilcoxon rank-sum test, or Fisher’s exact test, depending on the nature of the data, with results reported as counts and percentages.

Prior to model training, we conducted feature selection on the training set. First, all features were evaluated ten times using the Boruta algorithm to categorize them as either confirmed or tentative. Confirmed features that appeared more than five times were initially selected for ML model training. The remaining confirmed and tentative features were considered uncertain. Subsequently, we applied a tenfold cross-validation with least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) for feature selection. Finally, the intersection of the features selected by LASSO tenfold cross-validation and the uncertain Boruta features, together with the initially confirmed features, constituted the final feature set for ML model training. To evaluate potential multicollinearity among these features, the variance inflation factor (VIF) was calculated, with values greater than 10 considered indicative of multicollinearity between variables.

We then employed six ML models, including Categorical Boosting (CatBoost), Neural Networks (NN), regularized logistic regression (LR) (including LASSO LR, ridge LR, and elastic net LR), Random Forest (RF), Support Vector Machines (SVM), and gradient boosting decision tree (GBDT). To optimize model performance, we used tenfold cross-validation and grid search to determine the best hyperparameters. Additionally, to enhance result stability and reliability, we evaluated the models using 12 metrics: the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC), sensitivity, specificity, Positive Predictive Value (PPV), Negative Predictive Value (NPV), accuracy, F1-score, kappa, Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC), calibration curve, Brier Score (BS), and Decision Curve Analysis (DCA). Kappa measures the agreement between observed and predicted outcomes. Values ranged from −1 to 1, with values greater than 0.6 typically indicating substantial agreement [16]. MCC, derived from all four components of the confusion matrix (true positives, false negatives, true negatives, and false positives), provides a robust assessment of model performance, especially in imbalanced datasets. It is widely used in medical research, with values above 0.7 signifying strong model performance [17]. The calibration curve evaluates the alignment between predicted probabilities and actual outcomes, while the BS reflects the mean squared error of predictions, with lower values indicating better calibration [18]. The BS ranges from 0 to 1, with values below 0.25 generally indicative of optimal performance. The DCA curve was employed to assess the clinical utility of each predictive model by calculating the net benefit across a range of threshold probabilities. At a given threshold, a model with a higher decision curve indicates a greater net benefit, and thus, a higher potential for clinical application [19]. These metrics were derived using the bootstrap method. AUC served as the primary metric for model performance evaluation and was used to determine the best model based on test set results. Finally, to interpret the black-box nature of the best model, we employed SHAP to assess feature contributions in predicting three-year all-cause mortality in HF-AF patients. Additionally, SHAP interaction values were computed to explore pairwise feature interactions and better understand how combined features influence model predictions.

All statistical analyses, feature selection, model development, and evaluations were conducted using R (version 4.2.2) and Python (version 3.10).

Results

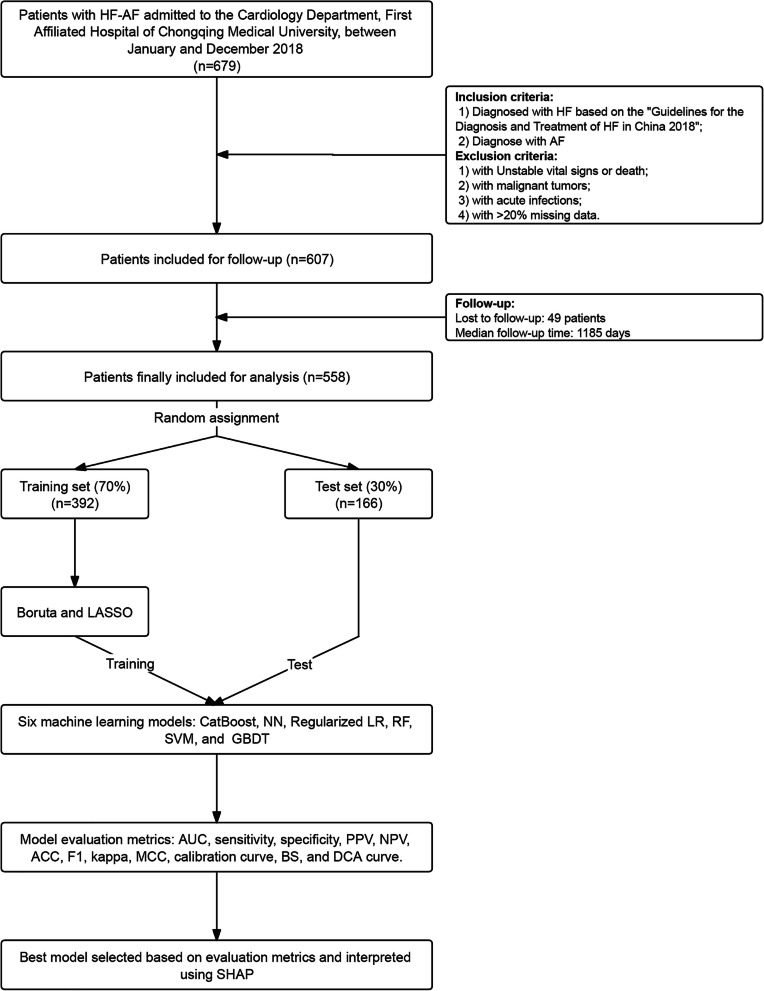

Based on the eligibility criteria, 558 individuals were included in the final analysis. Missing data were observed in 21 variables. Among them, BNP and D-dimer had the highest proportions of missingness, at 16.89% and 16.49%, respectively. The remaining variables had missing rates of less than 10%. Detailed information on the distribution of missing values across variables is provided in Fig. S1. The flowchart is presented in Fig. 1. After the 7:3 randomized assignment, data from 392 individuals were allocated to the training set, while the remaining 166 individuals comprised the test set. This division was performed to evaluate and identify the most effective ML models. Table 1 summarized the baseline characteristics. All parameters were similar and comparable between the training and test sets. The average age of the training set was 76 years, whereas that of the test set was 75 years. In the training and test groups, 151 and 64 participants, respectively, reached the endpoint event.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of patient selection, data processing, model development, and validation. Abbreviations: HF, heart failure; AF, atrial fibrillation; HF-AF, heart failure with atrial fibrillation; LASSO, least absolute shrinkage and selection operator; CatBoost, Categorical Boosting; NN, Neural Networks; LR, logistic regression; RF, Random Forest; SVM, Support Vector Machines; GBDT, gradient boosting decision tree; AUC, area under the curve; PPV, Positive Predictive Value; NPV, Negative Predictive Value; ACC, accuracy; F1, the harmonic mean of precision and recall; MCC, Matthews Correlation Coefficient; BS, Brier Score; DCA, Decision Curve Analysis; SHAP, Shapley Additive exPlanations

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of HF-AF patients

| Characteristics | Overall (n = 558) | Training-set (n = 392) | Test-set (n = 166) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MACE (3-year) | 0.994 | |||

| No | 343 (61.470) | 241 (61.480) | 102 (61.446) | |

| Yes | 215 (38.530) | 151 (38.520) | 64 (38.554) | |

| Age, year | 76.000 (69.000, 82.000) | 76.000 (69.000, 82.000) | 75.000 (67.000, 81.000) | 0.094 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 22.893 (20.433, 25.473) | 22.857 (20.382, 25.356) | 23.571 (20.831, 25.915) | 0.297 |

| ALC, 109 | 1.140 (0.790, 1.520) | 1.140 (0.785, 1.542) | 1.135 (0.803, 1.475) | 0.935 |

| ALB, g/L | 39.346 ± 4.865 | 39.254 ± 4.944 | 39.561 ± 4.681 | 0.497 |

| BUN, mmol/L | 7.400 (5.800, 9.900) | 7.300 (5.775, 9.800) | 7.650 (5.925, 9.900) | 0.323 |

| BNP, pg/mL | 537.214 (294.500,1050.664) | 539.548 (302.750,1067.568) | 514.218 (279.500,1024.706) | 0.547 |

| hs-CRP, mg/L | 4.000 (1.433, 13.601) | 4.020 (1.500, 14.618) | 3.975 (1.218, 13.050) | 0.832 |

| LVEDD, mm | 51.365 ± 9.705 | 51.329 ± 9.464 | 51.452 ± 10.283 | 0.891 |

| RAD, mm | 44.622 ± 8.448 | 44.859 ± 8.241 | 44.062 ± 8.920 | 0.309 |

| Anemia | 0.361 | |||

| No | 490 (87.814) | 341 (86.990) | 149 (89.759) | |

| Yes | 68 (12.186) | 51 (13.010) | 17 (10.241) | |

| Digoxin | 0.307 | |||

| No | 538 (96.416) | 380 (96.939) | 158 (95.181) | |

| Yes | 20 (3.584) | 12 (3.061) | 8 (4.819) | |

| NYHA classification | 0.109 | |||

| II | 136 (24.373) | 92 (23.469) | 44 (26.506) | |

| III | 302 (54.122) | 223 (56.888) | 79 (47.590) | |

| IV | 120 (21.505) | 77 (19.643) | 43 (25.904) | |

| Anticoagulation status | 0.182 | |||

| Continuous | 411 (73.656) | 284 (72.449) | 127 (76.506) | |

| Intermittent | 78 (13.978) | 53 (13.520) | 25 (15.060) | |

| Never | 69 (12.366) | 55 (14.031) | 14 (8.434) | |

| Length of stay, day | 9.000 (7.000, 12.000) | 9.000 (7.000, 12.000) | 9.000 (7.000, 12.000) | 0.417 |

Abbreviations: HF-AF heart failure and atrial fibrillation, MACE major adverse cardiovascular events (all-cause mortality), BMI body mass index, ALC absolute lymphocyte count, ALB albumin, BUN blood urea nitrogen, BNP B-type natriuretic peptide, hs-CRP high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, LVEDD left ventricular end-diastolic dimension, RAD right atrial dimension, NYHA New York Heart Association

First, we performed 10 iterations of Boruta screening to identify confirmed and tentative features. Subsequently, we determined the optimal λ value (0.038) and selected the corresponding non-zero features using tenfold cross-validation LASSO regression. As described previously, we identified 14 features, including age, BMI, BNP, BUN, hs-CRP, lymphocytes, right atrial dimension (RAD), left ventricular end-diastolic dimension (LVEDD), LOS, ALB, NYHA classification, anemia, anticoagulation duration, and digoxin use (Table S1). VIF results indicated no multicollinearity between features (all VIFs < 10) (Table S2). Therefore, all selected features were retained and incorporated into the ML model for training. Six models, comprising CatBoost, NN, LR, RF, SVM, and GBDT, were constructed. We ensured that the minimum number-of-events rule was met for each independent variable to guarantee the stability and validity of the models.

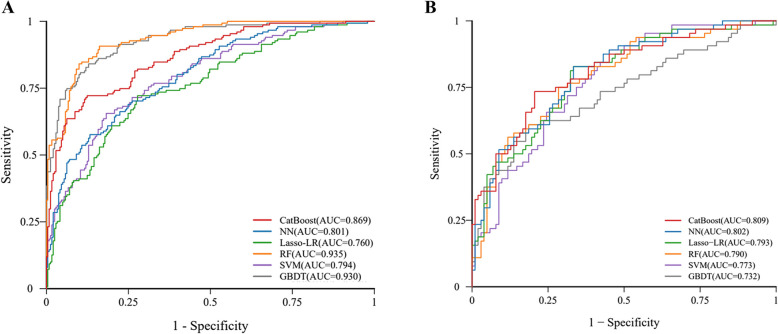

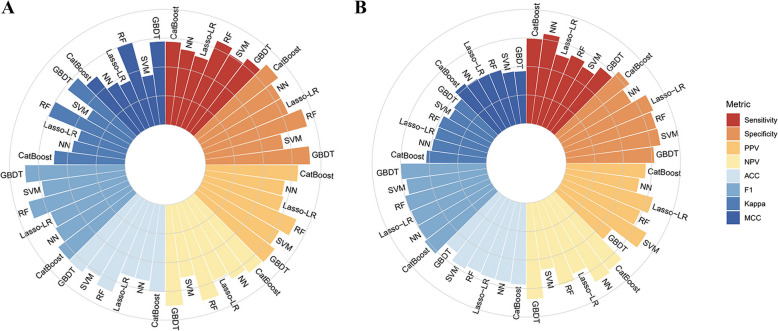

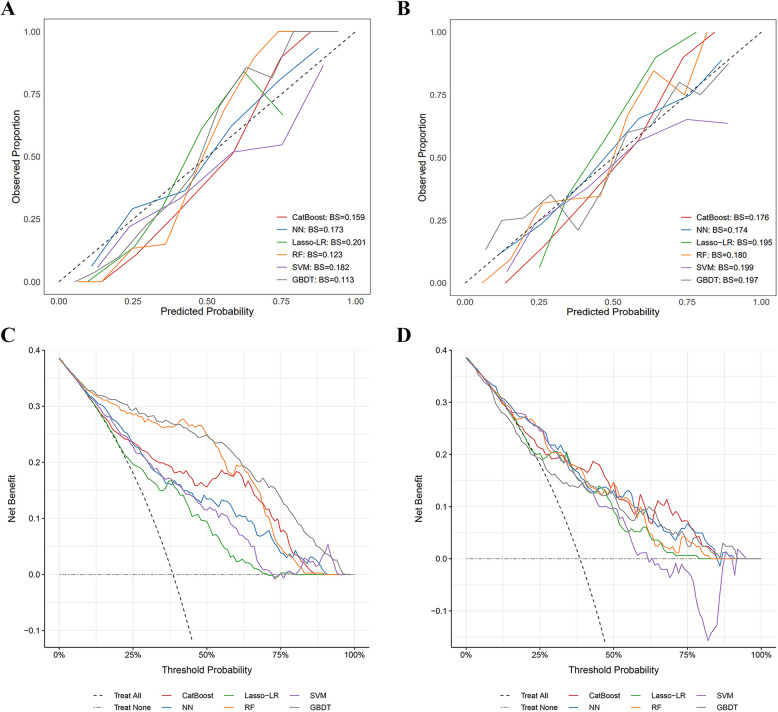

The models were trained using grid search for hyperparameter tuning, combined with a nested tenfold cross-validation strategy, to improve evaluation robustness. The average AUC from cross-validation was used to determine the optimal hyperparameter combination. Table S3 shows the specific hyperparameter tuning process. Model performance was evaluated on the test set. Figures 2, 3 and 4 and Table S4 provide an overview of the performance metrics for the six models on both the training and test sets. All evaluation metrics were derived using bootstrapping with 1,000 resamples to enhance the stability and reliability of the trained models.

Fig. 2.

ROC curves for each model in the training and test sets. A ROC curve in the training set, showing RF with the highest AUC (0.935), followed by GBDT (0.930), CatBoost (0.869), NN (0.801), SVM (0.794), and Lasso-LR (0.760); B ROC curve in the test set, demonstrating CatBoost with the highest AUC (0.809), followed by NN (0.802), Lasso-LR (0.793), RF (0.790), SVM (0.773), and GBDT (0.732). Abbreviations: ROC, receiver operating characteristic; AUC, area under the curve; CatBoost, Categorical Boosting; NN, Neural Networks; Lasso-LR, least absolute shrinkage and selection operator-penalized logistic regression; RF, Random Forest; SVM, Support Vector Machines; GBDT, gradient boosting decision tree

Fig. 3.

Evaluation metrics for each model in the training and test sets. A Evaluation metrics in the training set; B Evaluation metrics in the test set. Abbreviations: CatBoost, Categorical Boosting; NN, Neural Networks; Lasso-LR, least absolute shrinkage and selection operator-penalized logistic regression; RF, Random Forest; SVM, Support Vector Machines; GBDT, gradient boosting decision tree; PPV, Positive Predictive Value; NPV, Negative Predictive Value; ACC, accuracy; F1, the harmonic mean of precision and recall; MCC, Matthews Correlation Coefficient

Fig. 4.

Calibration and DCA curves for each model in the training and test sets. A Calibration curves in the training set. GBDT and RF demonstrated better calibration, with curves closest to the ideal diagonal line. CatBoost and NN showed moderate calibration, while SVM and Lasso-LR exhibited relatively lower predicted probabilities compared to other models. B Calibration curves in the test set. NN and CatBoost demonstrated better calibration, followed by RF and Lasso-LR, while GBDT and SVM showed relatively lower predicted probabilities. C Decision curve analysis in the training set. GBDT, RF, and CatBoost yielded the highest net benefit across most threshold probabilities, indicating superior clinical utility. D Decision curve analysis in the test set. All models demonstrated greater net benefit than the treat-all and treat-none strategies across a wide range of threshold probabilities. Abbreviations: CatBoost, Categorical Boosting; NN, Neural Networks; Lasso-LR, least absolute shrinkage and selection operator-penalized logistic regression; RF, Random Forest; SVM, Support Vector Machines; GBDT, gradient boosting decision tree; BS, Brier Score; DCA, Decision Curve Analysis

In the training set, RF had the best AUC (0.935), followed by GBDT (0.930) and CatBoost (0.869). The AUC of all models exceeded 0.760, and the AUC values of NN, SVM, and LASSO-LR were 0.801, 0.794, and 0.760, respectively (Fig. 2).

However, in the test set, CatBoost achieved the highest AUC (0.809). NN, LASSO-LR, RF, SVM, and GBDT achieved AUCs of 0.802, 0.793, 0.790, 0.773, and 0.732, respectively (Fig. 2). As CatBoost achieved the highest AUC, it was selected for the prediction of three-year all-cause mortality. The CatBoost model also performed well in secondary assessment metrics, with a sensitivity of 0.745, specificity of 0.790, PPV of 0.796, NPV of 0.833, F1 of 0.715, accuracy of 0.773, kappa of 0.526, and MCC of 0.532 (Fig. 3). The decision and calibration curves are shown in Fig. 4.

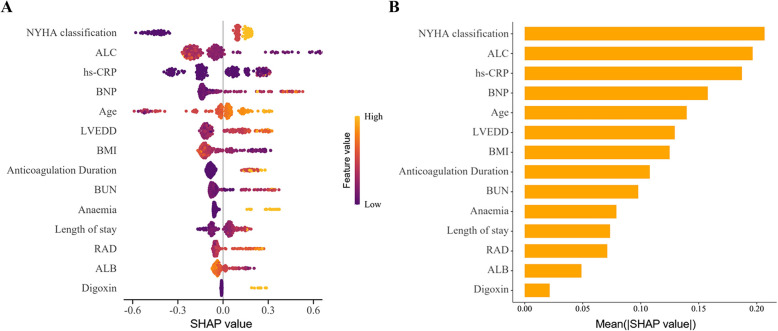

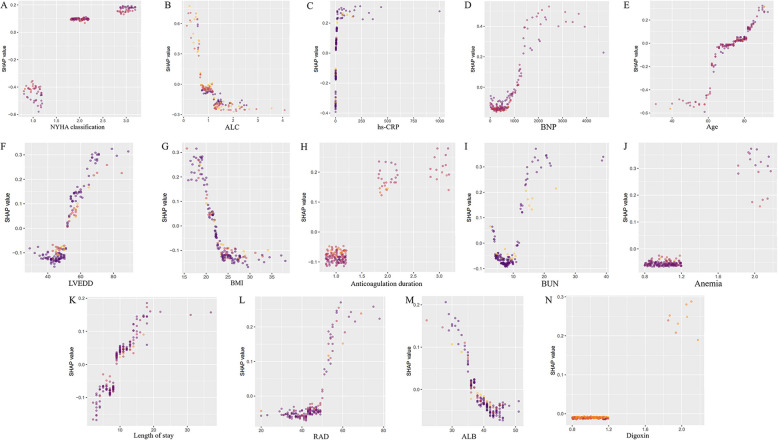

The impact of each feature on the endpoint event was analyzed using SHAP values in the CatBoost model. Features were ranked by importance from the highest to lowest (Fig. 5). The top seven important features were NYHA classification, ALC, hs-CRP, BNP, age, LVEDD, and BMI. The SHAP dependence plot (Fig. 6) demonstrates the impact of a single feature on the model’s output and how its importance shifts with varying feature values. The interaction heatmap (Fig. S2) revealed the relatively strong interaction between ALC and NYHA classification, followed by ALC and BNP. These findings suggested potential synergistic effects between ALC and cardiac function in contributing to the prediction of three-year all-cause mortality in HF-AF patients. Fig. S3 visualized pairwise interactions across some features.

Fig. 5.

SHAP explanations for CatBoost model. A Summary plot of the SHAP values for CatBoost. Each point represents a SHAP value for a feature in an individual patient. Features are ranked by their importance based on the mean absolute SHAP values. Orange points indicate higher feature values, while blue points indicate lower values. A positive SHAP value indicates a greater contribution to predicted risk, whereas a negative value indicates a protective effect; B Ranking of feature importance based on the average absolute SHAP values. The bar plot displays the mean absolute SHAP value for each feature, reflecting its average contribution to the model’s predictions across all samples. Features with higher values have a greater impact on the output of the CatBoost model. NYHA classification, LAC, and hs-CRP are the top three most influential features. Abbreviations: SHAP, Shapley Additive exPlanations; CatBoost, Categorical Boosting; NYHA, New York Heart Association; ALC, absolute lymphocyte count; hs-CRP, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; BNP, B-type natriuretic peptide; LVEDD, left ventricular end-diastolic dimension; BMI, body mass index; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; RAD, right atrial dimension; ALB, albumin

Fig. 6.

SHAP independence plot for each feature. Each plot (A-N) demonstrates how changes in feature values affect the model’s predictions, with higher SHAP values indicating a stronger impact on the outcome. The features include: A NYHA classification, B ALC, C hs-CRP, D BNP, E Age, F LVEDD, G BMI, H Anticoagulation duration, I BUN, J Anemia, K Length of stay, L RAD, M ALB, and N Digoxin. Abbreviations: SHAP, Shapley Additive Explanation; NYHA, New York Heart Abbreviations: SHAP, Shapley Additive exPlanations; NYHA, New York Heart Association; ALC, absolute lymphocyte count; hs-CRP, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; BNP, B-type natriuretic peptide; LVEDD, left ventricular end-diastolic dimension; BMI, body mass index; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; RAD, right atrial dimension; ALB, albumin

Discussion

HF and AF mutually reinforce each other and share a bidirectional causal relationship. Early identification of high-risk patients and individualized treatment strategies may enhance patient outcomes. Among the evaluated models, CatBoost demonstrated superior predictive performance.

There are limited studies on this topic. To our knowledge, only one prior cohort study from northern China explored the use of ML to predict all-cause mortality risk in patients with HF-AF [13]. That study included 1,796 patients and developed a single model using Light Gradient Boosting Machine, which achieved an AUC of 0.757 in predicting three-year mortality. Although our study included a smaller cohort (n = 558), we developed and compared multiple ML models and identified CatBoost as the best-performing algorithm. Our model achieved a slightly higher AUC of 0.809 than the previous study. Moreover, the CatBoost model attained an F1-score of 0.715, which was substantially higher than the previously reported 0.528. Given the class imbalance in both datasets, the F1-score serves as a more informative metric of model performance than accuracy or AUC alone, as it balances precision and recall. Careful model selection and optimization may help mitigate limitations posed by class imbalance and small cohort size. These findings indicate that our model may be more effective in identifying high-risk patients, thereby potentially facilitating earlier clinical intervention.

SHAP analysis identified higher NYHA classification as the most influential predictor of mortality. BNP, LVEDD, and RAD also contributed to the prediction of three-year all-cause mortality in patients with HF-AF. These variables reflect different dimensions of HF severity. Although VIF values indicated no multicollinearity among these variables, further stratified analysis based on NYHA classification revealed that patients with higher classification had elevated BNP and LVEDD levels (Table S5). HF symptoms, BNP concentrations, and echocardiographic measurements are often clinically interdependent. However, such clinical associations do not necessarily translate into statistical multicollinearity [20]. Previous studies have demonstrated that combining multiple indicators can provide additive diagnostic and prognostic value in HF [21–23]. In the context of ML training, these clinical interdependencies may influence SHAP values by distributing importance across correlated features, thereby potentially diluting the apparent contribution of any single variable. Consequently, the inclusion of these interrelated variables may improve the model’s overall predictive performance. While these variables were retained for their clinical significance and predictive power, caution should be exercised when interpreting individual SHAP values, as underlying feature dependencies may affect the reliability of such explanations.

Additionally, inflammatory markers such as ALC and hs-CRP are important in predicting the endpoint event. Inflammation has been linked to the development of HF [24] and AF [25]. Cohort studies have reported that elevated serum hs-CRP levels are linked to worse outcomes in both acute and chronic HF [26, 27]. Similarly, a meta-analysis [28] revealed that hs-CRP is associated with poor prognosis in AF patients because inflammation leads to oxidative stress, dysregulation of calcium ions, as well as tissue disruption and repair [29], potentially affecting electrical activity of the heart, which promotes cardiac fibrosis and structural changes [30]. Lymphocytes are key inflammatory cells, and low ALC contributes to the prognosis prediction of CVD. Low ALC has been correlated with increased mortality in both HF [31] and AF [32] patients. In these patients, ALC accumulation in the myocardium and decreased peripheral ALC may result from lymphocyte redistribution and may be linked to poor prognosis [33]. Notably, there might be an interaction between ALC and NYHA classification, with low ALC improving the model prediction performance for high NYHA classification. A similar association was observed for BNP. This may be because patients with advanced HF are more susceptible to infection in the presence of immunosuppression, increasing the risk of poor prognosis [34]. We found that low ALB levels were also a predictor of poor prognosis. Studies have shown that low ALB levels are closely linked to inflammation [35], antioxidants, and other factors [36] that promote poor prognosis in HF and AF cases [37].

Furthermore, SHAP analysis showed that anemia, higher BUN levels, and digoxin use were notable contributors to the prediction of all-cause mortality in patients with HF-AF. Approximately 30–50% of patients with HF-AF have comorbid anemia, with a high prevalence of iron deficiency anemia [38]. Anemia reduces the oxygen available to the body’s tissues, leading to increased myocardial workload and structural damage [38]. An elevated BUN level may serve as an indirect marker of neurohormonal activation reflecting renal dysfunction involved in the pathophysiology of HF-AF [39]. Additionally, impaired renal filtration reduces nitrogen excretion, leading to elevated BUN levels. Consequently, chronic kidney disease facilitates atrial fibrosis and cardiac electrophysiological remodeling via molecular mechanisms, including TGFβ1/Smad2/3 pathway activation, NLRP3 inflammasome activation, and connexin kinase modulation. These pathological changes ultimately accelerate the course of CVD [40]. Digoxin use remains controversial due to its narrow therapeutic window and patient susceptibility to drug concentrations [41]. Moreover, increasing evidence suggests that digoxin should be used with caution [42]. Finally, advanced age and prolonged hospitalization also contributed to the model’s ability to predict poor prognosis in HF-AF, which is also supported by studies [9, 43].

We demonstrated that high BMI and long-term regular anticoagulation therapy are identified as predictors of a better prognosis in patients with HF-AF. Obesity may reduce the risk of mortality in these patients by improving standard medical therapy and increasing tolerance to metabolic stress [44]. Anticoagulation was another protective factor that has been a cornerstone of treatment for AF; however, many patients are concerned about the bleeding risks associated with long-term anticoagulant therapy, prompting them to discontinue the drug prematurely or even refuse treatment. Despite the increased uptake of anticoagulation therapy in recent years, confidence in its use among patients remains suboptimal [45, 46]. This may indicate a need for clinicians to enhance patient education and promote adherence.

We used ML to predict the three-year risk of all-cause mortality in patients with HF-AF, achieving promising performance. This work demonstrated an additional application of ML in this field by incorporating numerous interpretable and important variables that can help clinicians better manage and individualize treatment strategies for these patients. However, it is important to note that ML models predict outcomes based on learned data patterns, primarily capturing correlations rather than causal relationships. Moreover, SHAP analysis, as a model-specific interpretation method, provides insights into how features contribute to model predictions but cannot be interpreted independently of the model itself. SHAP interaction values reflect the interactions between features, which are shaped by the data distribution and the underlying algorithmic structure. Therefore, the interpretability results derived from SHAP analysis should be interpreted cautiously and in conjunction with clinical expertise and biological plausibility to enhance applicability in clinical decision-making.

Our study has a few limitations. First, the single-center setting, absence of external validation, and relatively small sample size limit the generalizability of the model, and its performance across diverse populations remains uncertain. Although we performed more complex feature engineering with a tenfold cross-validation and multisampling to enhance the robustness of the results, publicly available data for direct external validation are currently unavailable. Our team is currently collecting medical records of patients with HF-AF from multiple hospitals in Chongqing, China (2023), with plans for a three-year follow-up in a subset of patients to further validate the robustness of the CatBoost model. Moreover, some cases of paroxysmal AF may have remained undetected, potentially introducing selection bias due to diagnostic underascertainment. Additionally, although our features are accessible, routinely collected, and generalizable, incorporating features such as cardiac nuclear magnetic resonance, mental health assessment, and genetic data in the future is expected to further improve the model's accuracy and enable more targeted clinical interventions.

Conclusion

Through the development and test of multiple ML models, we found that CatBoost outperformed other models in predicting the 3-year all-cause mortality in patients with HF-AF using simple and readily available clinical variables. Among these, NYHA classification, ALC, and hs-CRP showed strong associations with higher predicted mortality, whereas obesity and anticoagulation were associated with lower predicted risk. We believe that this study will assist clinicians in predicting mortality risk and providing early intervention for patients with HF-AF. In addition, it may help improve patients’ awareness of the importance of anticoagulation and other modifiable factors, thereby contributing to better outcomes and reducing the economic burden associated with this comorbidity.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

All authors thank the patients who participated in this study. All authors would like to thank all the staff members who helped complete this study for their hard work. Special thanks are given to Yuxuan Li for her valuable support in statistical analysis.

Abbreviations

- HF

Heart failure

- AF

Atrial fibrillation

- HF-AF

Heart failure and atrial fibrillation

- HR

Heart rate

- ML

Machine learning

- CVDs

Cardiovascular diseases

- NYHA classification

New York Heart Association classification

- BMI

Body mass index

- ALC

Absolute lymphocyte count

- ALB

Albumin

- BUN

Blood urea nitrogen

- hs-CRP

High-sensitivity C-reactive protein

- LOS

Length of stay

- LASSO

Least absolute shrinkage and selection operator

- VIF

Variance inflation factor

- CatBoost

Categorical Boosting

- NN

Neural Networks

- LR

Logistic regression

- RF

Random Forest

- SVM

Support Vector Machines

- GBDT

Gradient boosting decision tree

- AUC

The area under the receiver operating characteristic curve

- PPV

Positive Predictive Value

- NPV

Negative Predictive Value

- MCC

Matthews Correlation Coefficient

- BS

Brier Score

- DCA

Decision Curve Analysis

- RAD

Right atrial dimension

- LVEDD

Left ventricular end-diastolic dimension

Authors’ contributions

JC. W. and H. Y. analyzed the data. SY. X., JC. W., FL. Q, NY. B., and Z. L. contributed to the data acquisition and interpretation of data. JC. W. and GH. T. drafted the manuscript. H. X. and GL.C. substantively revised the manuscript. JC. W. prepared figures and Tables. All authors have accepted the submitted and final versions of this article.

Funding

This research was funded by the Natural Science Foundation of Chongqing (grant number GSTB2023NSCQMSX0491 and cstc2020jcyj-msxmX0863).

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The present study involves human participants and was approved by the Ethics Committee of the First Hospital of Chongqing Medical University (reference number 2020-528) and adhered to the guidelines of the Helsinki Declaration. Written informed consent was obtained from all individual participants.

Consent for publication

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Guanglei Chang, Email: augustchang.2008@qq.com.

Hua Xiao, Email: 202235@hospital.cqmu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Liu Z, Li Z, Li X, Yan Y, Liu J, Wang J, et al. Global trends in heart failure from 1990 to 2019: An age-period-cohort analysis from the Global Burden of Disease study. ESC Heart Fail. 2024;11(5):3264–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Elliott AD, Middeldorp ME, Van Gelder IC, Albert CM, Sanders P. Epidemiology and modifiable risk factors for atrial fibrillation. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2023;20(6):404–17. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Reddy YNV, Borlaug BA, Gersh BJ. Management of Atrial Fibrillation Across the Spectrum of Heart Failure With Preserved and Reduced Ejection Fraction. Circulation. 2022;146(4):339–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vermond RA, Geelhoed B, Verweij N, Tieleman RG, Van der Harst P, Hillege HL, et al. Incidence of Atrial Fibrillation and Relationship With Cardiovascular Events, Heart Failure, and Mortality: A Community-Based Study From the Netherlands. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66(9):1000–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carlisle MA, Fudim M, DeVore AD, Piccini JP. Heart Failure and Atrial Fibrillation, Like Fire and Fury. JACC Heart Fail. 2019;7(6):447–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zuin M, Bertini M, Vitali F, Turakhia M, Boriani G. Heart Failure-Related Death in Subjects With Atrial Fibrillation in the United States, 1999 to 2020. J Am Heart Assoc. 2024;13(9): e033897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Verhaert DVM, Brunner-La Rocca HP, van Veldhuisen DJ, Vernooy K. The bidirectional interaction between atrial fibrillation and heart failure: consequences for the management of both diseases. Europace. 2021;23(23 suppl 2):ii40-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jones N, Smith M, Lay-Flurrie S, Roalfe AK, Yang Y, Hobbs FDR, et al. Survival among people with heart failure and atrial fibrillation; a population cohort study. Eur Heart J. 2022;43(Supplement_2):ehac544.899. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ziff OJ, Carter PR, McGowan J, Uppal H, Chandran S, Russell S, et al. The interplay between atrial fibrillation and heart failure on long-term mortality and length of stay: Insights from the, United Kingdom ACALM registry. Int J Cardiol. 2018;1(252):117–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beam AL, Kohane IS. Big Data and Machine Learning in Health Care. JAMA. 2018;319(13):1317–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Awan SE, Sohel F, Sanfilippo FM, Bennamoun M, Dwivedi G. Machine learning in heart failure: ready for prime time. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2018;33(2):190–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wegner FK, Plagwitz L, Doldi F, Ellermann C, Willy K, Wolfes J, et al. Machine learning in the detection and management of atrial fibrillation. Clin Res Cardiol. 2022;111(9):1010–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zheng C, Tian J, Wang K, Han L, Yang H, Ren J, et al. Time-to-event prediction analysis of patients with chronic heart failure comorbid with atrial fibrillation: a LightGBM model. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2021;21(1):379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tang F, Ishwaran H. Random Forest Missing Data Algorithms. Stat Anal Data Min. 2017;10(6):363–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alsaber A, Al-Herz A, Pan J, Al-Sultan AT, Mishra D. Handling missing data in a rheumatoid arthritis registry using random forest approach. Int J Rheum Dis. 2021;24(10):1282–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33(1):159–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chicco D, Jurman G. The advantages of the Matthews correlation coefficient (MCC) over F1 score and accuracy in binary classification evaluation. BMC Genomics. 2020;21(1):6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rufibach K. Use of Brier score to assess binary predictions. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63(8):938–9. author reply 939. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Van Calster B, Wynants L, Verbeek JFM, Verbakel JY, Christodoulou E, Vickers AJ, et al. Reporting and Interpreting Decision Curve Analysis: A Guide for Investigators. Eur Urol. 2018;74(6):796–804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lund LH, Pitt B, Metra M. Left ventricular ejection fraction as the primary heart failure phenotyping parameter. Eur J Heart Fail. 2022;24(7):1158–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Williams SG, Ng LL, O’Brien RJ, Taylor S, Wright DJ, Li YF, et al. Complementary roles of simple variables, NYHA and N-BNP, in indicating aerobic capacity and severity of heart failure. Int J Cardiol. 2005;102(2):279–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Steg PG, Joubin L, McCord J, Abraham WT, Hollander JE, Omland T, et al. B-type natriuretic peptide and echocardiographic determination of ejection fraction in the diagnosis of congestive heart failure in patients with acute dyspnea. Chest. 2005;128(1):21–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lim TK, Hayat SA, Gaze D, Celik E, Collinson P, Senior R. Independent value of echocardiography and N-terminal pro-natriuretic Peptide for the prediction of major outcomes in patients with suspected heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 2007;100(5):870–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aimo A, Bayes-Genis A. Biomarkers of inflammation in heart failure: from risk prediction to possible treatment targets. Eur J Heart Fail. 2023;25(2):161–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boos CJ. Infection and atrial fibrillation: inflammation begets AF. Eur Heart J. 2020;41(10):1120–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pellicori P, Zhang J, Cuthbert J, Urbinati A, Shah P, Kazmi S, et al. High-sensitivity C-reactive protein in chronic heart failure: patient characteristics, phenotypes, and mode of death. Cardiovasc Res. 2020;116(1):91–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang L, He G, Huo X, Tian A, Ji R, Pu B, et al. Long-Term Cumulative High-Sensitivity C-Reactive Protein and Mortality Among Patients With Acute Heart Failure. J Am Heart Assoc. 2023;12(19):e029386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li G, Zhao Y, Peng Z, Zhao Y. Risk factors for the recurrence of atrial fibrillation after catheter ablation: a meta-analysis. Egypt Heart J. 2025;77(1):9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang H, Dhalla NS. The Role of Pro-Inflammatory Cytokines in the Pathogenesis of Cardiovascular Disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(2):1082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Ramos-Mondragón R, Lozhkin A, Vendrov AE, Runge MS, Isom LL, Madamanchi NR. NADPH Oxidases and Oxidative Stress in the Pathogenesis of Atrial Fibrillation. Antioxidants (Basel). 2023;12(10):1833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Vaduganathan M, Ambrosy AP, Greene SJ, Mentz RJ, Subacius HP, Maggioni AP, et al. Predictive value of low relative lymphocyte count in patients hospitalized for heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: insights from the EVEREST trial. Circ Heart Fail. 2012;5(6):750–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yu Y, Wang S, Wang P, Xu Q, Zhang Y, Xiao J, et al. Predictive value of lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio in critically Ill patients with atrial fibrillation: A propensity score matching analysis. J Clin Lab Anal. 2022;36(2): e24217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Núñez J, Miñana G, Bodí V, Núñez E, Sanchis J, Husser O, et al. Low lymphocyte count and cardiovascular diseases. Curr Med Chem. 2011;18(21):3226–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Heidecker B, Pagnesi M, Lüscher TF. Heart failure and respiratory tract infection: Cause and consequence o f acute decompensation? Eur J of Heart Fail. 2024;26(4):960–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Soeters PB, Wolfe RR, Shenkin A. Hypoalbuminemia: Pathogenesis and Clinical Significance. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2019;43(2):181–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Belinskaia DA, Voronina PA, Shmurak VI, Jenkins RO, Goncharov NV. Serum Albumin in Health and Disease: Esterase, Antioxidant, Transporting and Signaling Properties. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(19):10318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Manolis AA, Manolis TA, Melita H, Mikhailidis DP, Manolis AS. Low serum albumin: A neglected predictor in patients with cardiovascular disease. Eur J Intern Med. 2022;102:24–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chopra VK, Anker SD. Anaemia, iron deficiency and heart failure in 2020: facts and numbers. ESC Heart Fail. 2020;7(5):2007–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Anand IS, Gupta P. Anemia and Iron Deficiency in Heart Failure: Current Concepts and Emerging Therapies. Circulation. 2018;138(1):80–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Qiu H, Ji C, Liu W, Wu Y, Lu Z, Lin Q, et al. Chronic Kidney Disease Increases Atrial Fibrillation Inducibility: Involvement of Inflammation, Atrial Fibrosis, and Connexins. Front Physiol. 2018;9:1726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Patocka J, Nepovimova E, Wu W, Kuca K. Digoxin: Pharmacology and toxicology-A review. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol. 2020;79:103400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Javid S, Gohil NV, Ali S, Tangella AV, Hingora MJH, Hussam MA, et al. Association of serum digoxin concentration with morbidity and mortality in patients with atrial fibrillation, heart failure and reduced ejection fraction of 45 % or below. Curr Probl Cardiol. 2024;49(2):102218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pan Y, Xu L, Yang X, Chen M, Gao Y. The common characteristics and mutual effects of heart failure and atrial fibrillation: initiation, progression, and outcome of the two aging-related heart diseases. Heart Fail Rev. 2022;27(3):837–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang J, Yang Y min, Zhu J, Zhang H, Shao X hui. Obesity paradox in patients with atrial fibrillation and heart failure. Int J Cardiol. 2014;176(3):1356–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 45.Alcusky M, McManus DD, Hume AL, Fisher M, Tjia J, Lapane KL. Changes in Anticoagulant Utilization Among United States Nursing Home Residents With Atrial Fibrillation From 2011 to 2016. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8(9): e012023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liu T, Yang HL, Gu L, Hui J, Omorogieva O, Ren MX, et al. Current status and factors influencing oral anticoagulant therapy among patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation in Jiangsu province, China: a multi-center, cross-sectional study. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2020;20(1):22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.