Abstract

Three different reaction types are extensively studied at multi‐gram scale by resonant acoustic mixing (RAM): 1) the Knoevenagel condensation to vanillin barbiturate; 2) the Biginelli multicomponent reaction to dihydropyrimidinones, which includes the anticancer drug (±)‐Monastrol; and 3) the Biltz synthesis to the antiepileptic drug Phenytoin. The RAM approach demonstrated advantages over traditional solution‐based methods by enhancing sustainability and minimizing solvent usage. The processes are assessed by green chemistry metrics and tools (e.g., Chem21 and DOZN 3.0) demonstrating that RAM technology is outperforming compared to the corresponding solution‐based methods, representing an environmentally friendly alternative to conventional approaches in organic synthesis and for the preparation of pharmaceuticals in a more sustainable way. The use of milling beads, for grinding‐assisted RAM (GA‐RAM) processes, alone or in combination with liquid‐assisted RAM (LA‐RAM), is also investigated, to enhance reaction efficiency.

Keywords: active pharmaceutical ingredients, green chemistry metrics, mechanochemistry, rearrangements, resonant acoustic mixing

Knoevenagel condensation, Biginelli three‐component reaction and benzylic rearrangement are investigated at multi‐gram scale, by resonance acoustic mixing (RAM), to prepare biologically active molecules, also including the marketed Phenytoin (antiepileptic drug). Chem21 and DOZN 3.0 tools were used to assess the greenness of the RAM‐assisted syntheses, outperforming in comparison with the solution‐based counterparts, in terms of green metrics and sustainability.

1. Introduction

The facile and effective synthesis of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) has always been of importance not only to the big pharma companies but also many research groups around the world. The main aspects of the field research include the investigation of more economic, sustainable, “green”, and simplistic ways while the yields and the efficiency of the process stay intact. The field of mechanochemistry combines all these desired aspects while cuts down the waste production and accelerates the traditional synthetic pathways.[ 1 ] The most widely studied modern mechanochemical process regarding APIs synthesis is ball milling[ 2 ] with twin‐screw extrusion (TSE)[ 3 ] and bead‐mill[ 4 ] coming right after.

In the last years, technologies based on resonance acoustic mixing (RAM), largely used for the preparation of different type of materials,[ 5 ] were recently used for preparing co‐crystals[ 6 ] or to carry out organic synthesis.[ 7 ] Operating at low‐frequency acoustic energy (60 Hz), RAM enables the chemical transformations by intensively mixing of the materials, in the solid state and/or in wet conditions. [7a] However, examples on the use of RAM as enabling technology applied to organic syntheses still remain limited.

To expand the use of RAM for covalent‐bond forming reactions and to better understand its potential in synthetic chemistry (at different scales), three different reaction types extensively studied by ball‐milling, were selected as benchmarks: 1) the Knoevenagel condensation to vanillin barbiturate; 2) the Biginelli multicomponent reaction (MCR) to dihydropyrimidinones, which includes the anticancer drug (±)‐Monastrol;[ 8 ] and 3) the Biltz synthesis[ 9 ] to the antiepileptic drug Phenytoin, occurring via a cascade reaction sequence involving a condensation reaction followed by a challenging benzylic rearrangement.

To understand the potentiality of RAM methods toward the preparation of value added molecules for real‐case applications, and to evaluate the eco‐footprint of these reactions in comparison with the corresponding solvent‐based procedures, their efficiency, energy consumption, and environmental impact were assessed by green chemistry metrics and toward the 12 Principles of green chemistry, using freely available toolkits such Chem21[ 10 ] and DOZN 3.0.[ 11 ] Indeed, this approach is unprecedented for RAM‐assisted syntheses, while the use of green chemistry metrics in mechanochemical processes other than RAM, is now becoming more common,[ 12 ] since the seminal application to the preparation of amino‐acids derivatives.[ 13 ]

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Knoevenagel condensation to Vanillin Barbiturate

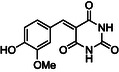

The mechanochemical Knoevenagel condensation to vanillin barbiturate in a ball mill[ 14 ] and the real‐time in situ Raman spectroscopy monitoring[ 15 ] were previously reported. Herein, the preparation of Vanillin Barbiturate (1) by RAM was investigated (Scheme 1 ).

Scheme 1.

Best conditions for RAM‐activated synthesis of Vanillin Barbiturate (1) in the presence of catalytic amounts of acid (LA‐RAM) and ZrO2 grinding balls (GA‐RAM).

Various experiments using RAM were run to gain an understanding of how vanillin and barbituric acid would react. Initially small glass vials (30 mL capacity) were used to ascertain how the powders would behave in the closed system at high mixing speeds. The reaction between vanillin and barbituric acid is known to produce a bright orange solid, which is a good indicator of product formation.

During these tests only the reagent powders were added to the vial followed by short mixing times of 5‐ and 10‐min intervals with 5 min rest periods, up to 30 min mixing in total, at 80 g acceleration to allow for reaction monitoring. A color change was observed although it was not representative of the expected vanillin barbiturate (1) product, with a negligible raise of temperature of the container after mixing.

No obvious pressure build‐up was observed in the closed vessel and only traces of the condensation product were obtained. Preliminary tests at 5–8 g scale were then repeated at 80 g for 20 min, using catalytic amounts (0.1–0.2 mL) of water and different acids (e.g., diluted acetic or hydrochloric acid; see also Table S1, Supporting Information). The biggest color change effect was obtained with hydrochloric acid 2 m (1 mL of HCl 2 m was used for 5 g of vanillin), leading to a mixture with a deep orange‐yellow color (Figure S1, Supporting Information). However, analysis by liquid‐state 1H NMR showed very little product was forming under these conditions, despite the distinct color change.

RAM‐activated processes are usually described as “grinding‐free media”, however depending on the reaction type, the use of aiding “mixing” agent consisting of “milling beads” could be necessary,[ 16 ] to improve not only the mixing extent for systems with unfavorable rheology (viscous or sticky media) but also to increase the mechanochemical stress experimented by the reactants, in a “grinding assisted resonance acoustic mixing” (GA‐RAM) process.

Therefore, considering the low conversions obtained in the previous experiments and in order to increase the mechanical mixing and to promote better conversion, the acid‐catalyzed reaction was repeated in polypropylene (PP) vessels (20 mL capacity), instead of glass vials, also introducing 3 mm zirconia beads, with an optimal 1:1 bead to powder ratio (10 g of reagents and 10 g of 3 mm beads). The RAM experiment was conducted by discontinuous mixing: a mixing phase of 5 min at 100 g followed by a rest phase of 5 min, for three mixing cycles, was chosen so that overheating, gas formation, and swelling could be controlled. During each rest phase, ex situ 1H NMR analyses were conducted on an aliquot of sample, each time that a color change was observed during the mixing/resting cycles (Figure 1 ). Colorimetric variations were considered to qualitative evaluate the reaction outcome. Indeed, after the first cycle, a yellow powder was obtained when mixing the reagents at 100 g during 15 min, with no addition of acid catalyst (Figure 1a). Then, liquid‐assisted RAM (LA‐RAM) was performed upon addition of 1 mL of HCl 2 m (η = 0.1 μL mg−1). As a result, agglomeration of the powders around the beads occurred (cycle 2, Figure 1b), together with a change of color turning to dark orange and suggesting an intermediate formation. Finally, after the third cycle, the rheology of the product turned again into a powder of yellow‐orange color (Figure 1c), characteristic of the desired product. Unfortunately, the reaction did not reach completion, despite longer mixing times (and cycles), as shown by 1H NMR analyses. The color change is a clear indication that the reaction was occurring during RAM processing, going from two white powders (vanillin and barbituric acid) to a bright yellow/orange solid (Figure 1 and S1, Supporting Information). The π system becomes more conjugated once vanillin barbiturate (1) is formed, presenting a typical donor (barbiturate moiety)–acceptor (the phenolic‐OH and the ‐OMe group of the vanillin) pattern.

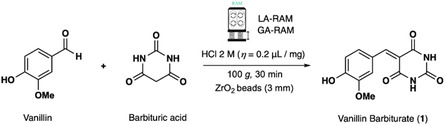

Figure 1.

Distinct color change occurring when mixing the reactants at 80 g in the presence of 10 g of milling beads in PP vessels of 20 mL (reaction scale 35 mmol Vanillin, 10 g total): a) with no acidic catalyst, during 15 min (cycle 1); b) after addition of acid catalyst (HCl 2M) during 5 min (cycle 2), and c) for additional 15 min reaction (cycle 3).

However, to improve the mixing conditions, a high‐density polyethylene (HDPE) vessel was used, having more desirable width and height (150 mL capacity), with a 1:1.6 reagents to the beads ratio (for 60 g of mixed reagents, 5 mL 2 m HCl and 100 g of 3 mm zirconia beads were used). In a first attempt, mixing the reagents twice during 10 min at 80 g acceleration, followed by 5 min rest in between each cycle, did not afford full conversion (Figure 2a). Full conversion was obtained after four additional cycles of 10 min each (with 5 min rest in between each cycle), at an acceleration of 100 g (Figure 2b), as shown by 1H NMR analyses of the crude.

Figure 2.

Aspect of crudes of Knoevenagel condensations to vanillin barbiturate (1) carried out in the presence of 100 g of milling beads in HDPE vessel of 150 mL (30–50 g scale, 100–170 mmol o‐vanillin). The reaction was conducted at: a) 80 g during 20 min of cycled mixing; b) 100 g during 40 min of cycled mixing, and c) 100 g during 30 min of continuous mixing.

1H NMR was carried out on all the samples to track the progress of the reactions: product formation was evident by the appearance of two distinct peaks after 11 ppm, attributed to the N‐H protons of vanillin barbiturate (1), and the disappearance of the singlet at 9.5 ppm, characteristic of the starting aldehyde proton in vanillin. Finally, the reaction was repeated at 100 g acceleration for 30 min without any rest phase (Figure 2c), leading to full conversion of starting materials, as determined by 1H NMR analyses of the bright orange‐yellow powders, and clearly indicating that continuous mixing (instead of cycled) at higher acceleration (100 g instead of 80 g) were needed to achieve full conversion. Vanillin barbiturate (1) (23 g, 87 mmol, 95%) was obtained after 30 min reaction only, with no need of post‐reaction work‐up, the final product being recovered directly from the HDPE vessel, after sieving the beads.[ 17 ]

In the better conditions conditions (Scheme 1), the simultaneous use of LA‐RAM and GA‐RAM outperformed compared to solution‐based synthesis[ 18 ] in terms of throughput (95% yield vs 58%, respectively) over the time (30 min reaction vs 2.5 h, respectively), and with no‐need of work‐up, in contrast to solution‐based synthesis requiring a large amount of water (200 mL for 6.0 mmol of vanillin) used as solvent and for recovering the final product as precipitate after several washings and drying under vacuum.

The solvent‐free Knoevenagel condensation reaction to vanillin barbiturate (1) was previously described to occur with full conversion of the reagents only under activation upon heating, for example, by microwave irradiation, at 50 °C during 1 h.[ 14 ] Therefore, to get additional evidence that the Knoevenagel condensation reaction to vanillin barbiturate (1) occurred by RAM activation with full conversion of the reactants in 30 min, and not in the NMR tube during the analyses, kinetic studies both in solution by 1H NMR and at the solid state by FT‐IR (ATR device) were performed.

To investigate the reaction kinetics in solution, the starting materials were solubilized in deuterated DMSO‐d 6 and the reaction mixture was analyzed regularly, monitoring its progress at t = 0 min, t = 1 h, t = 12 h, and t = 24 h (Figure S4, Supporting Information). After 24 h, and as expected, the reaction did not reach full conversion, as it can be observed by the presence of vanillin in the crude, indicated by the singlet at 9.77 ppm, characteristic for HC=O functional group of the starting aldehyde. There results, not only are aligned with these previous findings for a similar experiment aiming to demonstrate that the reaction was occurring by twin‐screw extrusion (e.g., no full conversion was reached even after 95 days in the NMR tube)[ 19 ] but also highlight that RAM activation allowed the reaction to occur with full conversion of the reactants.

To rule out also the possibility that the reaction was occurring by simple contact of the reagents (and with full conversion), the reactivity of the starting materials at the solid‐state was further investigated by FT‐IR (ATR device) (Figure S9, Supporting Information). Therefore, the reactants were gently mixed by hand in a vial and the powder was analyzed by FT‐IR during the same amount of time the reaction took place in using the RAM device (30 min in total), collecting a spectrum at t = 0 min, t = 5 min, t = 15 min, and t = 30 min. For comparison, FT‐IR spectra were recorded also for the substrates vanillin, barbituric acid, and for the final product vanillin barbiturate (1), obtained by RAM. The overlapping of the FT‐IR spectra recorded at different times, with those of the reference substrates, and the vanillin barbiturate (1), show that no reaction is occurring at the solid state during the kinetic study by simple contact of the reagents and by applying a constant pressure to the powders.

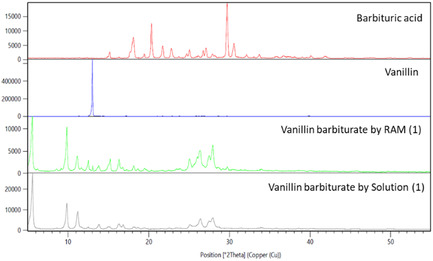

To further confirm the identity of the final product and to understand any differences in the morphology of the product, the powders were analyzed by several other characterization methods, such as: solid state (SS) 1H and 13C MAS NMR (Figure 3 and S9, Supporting Information respectively), X‐ray powder diffraction (PXRD, Figure 4 ), scanning electron microscopy (SEM, Figure S11, Supporting Information), and Raman spectroscopy (Figure S12, Supporting Information).

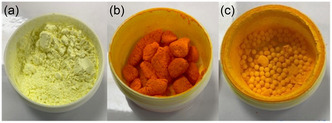

Figure 3.

Comparing normalized 1H solid‐state MAS NMR spectra of starting materials vanillin (black) and barbituric acid (blue) to Vanillin Barbiturate (1) (green).

Figure 4.

PXRD analyses showing stacked diffraction patterns of starting materials vanillin (blue), barbituric acid (red) and vanillin barbiturate (1) prepared by LA‐RAM as a mixture of Form II and Form III (green) and in solution (gray).[ 20 ] The same wavelength (Cu K radiation, 1.5406 Å) was used to record the PXRD patterns, for comparison with the reported data in solution.[ 20 ] The list for the most intense peaks for PXRD diffractogram of each compound is given in Tables S2–S5, Supporting Information. The magnified PXRD diffractogram for vanillin is reported in Figure S10, Supporting Information.

Solid state (SS) 1H MAS NMR spectrum of vanillin barbiturate (1) prepared by RAM was compared with the spectra of the starting materials vanillin and barbituric acid (Figure 3a). The 1H MAS NMR spectrum for the barbituric acid shows distinctive NH functionality at 11.1 ppm,[ 15 ] which is also observed in the corresponding NMR spectrum recorded for the vanillin barbiturate (1) prepared by LA‐RAM, and presenting an additional downfield shoulder (at 11.2 ppm)[ 15 ] as expected for two not synchronous NH protons. Similarly, the distinctive CHO peak of the vanillin (at 10.55 ppm)[ 15 ] is no longer present in the spectrum of vanillin barbiturate (1) obtained by LA‐RAM. Moreover, OH and aromatic protons in vanillin (at 6–8 ppm) are down‐shielded as expected, due to an increase of conjugation in vanillin barbiturate (1) (Figure 3).

13C CP MAS NMR was used to gain a better understanding of the peak dispersion (Figure S9, Supporting Information). The measurements confirmed the disappearance of the CH2 carbon signal at 39.6 ppm associated with barbituric acid in favor of a new peak at 57.5 ppm corresponding to the exocyclic carbon atom of the newly formed C=C double bond of the Knoevenagel product. Vanillin barbiturate (1) exceeded the expected 12 distinct carbon signals (with six additional signals), suggesting that multiple molecular units (different polymorphs) can be present in the crystallographic unit cell (Z > 1), consisting of a mixture of Form II and Form III,[ 15 ] based on the data previously reported for the solid‐state 13C NMR of pure Form II and Form III.[ 15 ]

Additional analysis by PXRD was then carried out to gain a better understanding of the crystalline composition of the materials (Figure 4). The PXRD diffractogram for vanillin barbiturate (1) prepared both by LA‐RAM and in solution were compared, also in relation to the PXRD diffractogram of the starting materials vanillin and barbituric acid. The PXRD pattern recorded for vanillin barbiturate (1) prepared by solution chemistry by us, showed characteristic 2θ peaks at 5.57° (corresponding to the spacing of 1.59 nm between the diffracting planes) and 10,[ 20 ] in agreement with the previously reported diffractogram, recorded at the same wavelength, for synthesis in aqueous solution.[ 20 ] However, PXRD patterns of vanillin barbiturate (1) prepared by RAM and in solution indicated the formation of completely different products. Previous reports demonstrated that the reagents can form a cocrystal prior to onset of the chemical reaction, and that three different forms (Form I, Form II, and Form III) of vanillin barbiturate (1) can be obtained at the solid‐state, depending on the mechanochemical processing conditions.[ 15 ] Mechanistic studies were also conducted to identify the processing conditions to selectively prepare each form, and identifying heating at 150 °C as crucial parameter to promote a polymorphic transition converting all the forms (co‐crystal included) to the most stable Form III.[ 21 ]

The PXRD diffractogram for the vanillin barbiturate (1) prepared by LA‐RAM presented two different crystalline phases identified as Form II[ 15 ] and Form III,[ 15 , 21 ] and previously reported for the Knoevenagel condensation in the ball mill. The slight increase of temperature occurring during RAM synthesis of vanillin barbiturate (1), was not likely enough to convert Form II to Form III, which explain the presence of both forms in the product prepared by RAM.

This agrees with the results obtained by 13C solid‐state MAS NMR spectra. Even if Form III was obtained in a mixture with Form II, its formation occurred without need of external heating by LA‐RAM, outperforming in comparison with ball‐milling processes, failing in delivering it after 50 h milling, and for which heating at 75 °C was necessary.[ 21 ]

Samples of vanillin barbiturate (1) prepared by both LA‐RAM and in solution were also analyzed by SEM to identify the morphology of the material (Figure S11, Supporting Information). As a result, in both cases, the formation of flower‐like nodules, which under higher magnification consisted of soft petal‐like crystals, was observed. Additionally, the analysis of the crude reaction mixture by ex situ Raman spectroscopy leading to vanillin barbiturate (1) was in agreement with previously reported data[ 15 ] (Figure S12, Supporting Information).

It showed a characteristic band at 1543 cm−1 corresponding to the new formed C=C double bond in conjugation to the aromatic ring, leading to a subtle C=C stretch (at 1500 cm−1) shifting. Similarly, the bands associated to the C=O stretching of the starting aldehyde (i.e., vanillin) at 1650 cm−1 and the CH2 stretching of methylene at 650 cm−1 for barbituric acid were no longer observed in the vanillin barbiturate (1) sample.

The RAM‐assisted two‐component Knoevenagel condensation reaction demonstrated, the investigation was extended to a more complex system, involving a domino/cascade reaction sequence consisting of condensation‐addition‐intramolecular cyclisation.

2.2. Biginelli 3‐component reaction (3‐CR)

Synthetic strategies based on multicomponent reactions (MCR),[ 22 ] combined with enabling technologies such as RAM are still unexplored. MCR are a very powerful and attractive “benign‐by‐design” approach intrinsically endowed with step, pot, and intrinsically high atom economy, usually leading to minimal waste generation, while allowing access molecular diversity and structural complexity, and often applied to the preparation of highly substituted dihydropyrimidinones,[ 23 ] scaffolds of great importance in medicinal chemistry, being contained in many biologically active compounds, and marketed drugs. The Biginelli 3‐CR was extensively studied by ball milling[ 24 ] and by single‐screw drill (SSD) device. [24] This investigation by RAM constitutes a benchmark for evaluating the synthetic potential of MCR in association with this specific technology.

Therefore, two 3‐CR were carried out: equimolar amounts of ethylacetoacetate, benzaldehyde and (thio)urea were reacted by RAM to afford ethyl 1,4‐dihydro‐2‐hydroxy‐6‐methyl‐4‐phenyl‐5‐pyrimidinecarboxylate (2) or the bioactive (±)‐Monastrol (3), a cell‐permeable compound that arrests cells in mitosis by inhibiting Eg5, a member of kinesin‐5 family, and a potent anticancer drug[ 25 ] (Scheme 2 ).

Scheme 2.

Best conditions for Biginelli 3‐CR by GA‐RAM to dihydropyrimidinone derivatives: 1,4‐dihydro‐2‐hydroxy‐6‐methyl‐4‐phenyl‐5‐pyrimidinecarboxylate (2) and the bioactive (±)‐Monastrol (3).

The preparation of dihydropirimidone (2) was used as benchmark. The reagents, in a 1:1:1 molar ratio (total volume 7.32 mL), were added to a glass vial (20 mL) and the sample was mixed manually and monitored over 2 days to assess for heat formation, bloating and corrosion. In an identical experiment, RAM was applied at 100 g for 5 min, without the addition of beads. Even if no significant overheating, bloating or gas evolution was observed, the crude turned into a yellow highly viscous paste, and no further mixing was observed, hampering good conversion of the reactants. After these initial findings, a more thorough screening of the optimal conditions for the formation of (2) was carried out in RAM, investigating different process parameters such as the reaction scale, the use of GA‐RAM and the suitable milling media (e.g., ZrO2 or stainless steel beads), the effect of variable amounts of solid acidic catalysts (e.g., citric acid, p‐TsOH SiO2), and the order of addition of the reagents (by a one‐pot/one step 3‐CR or by a two‐step cascade sequence) (Table S6, Supporting Information).

Very interestingly, both chemical and process parameters were determinant to form the desired product: 1) the reaction scale; and 2) the presence of the milling media (i.e., milling balls for GA‐RAM), usually described as not necessary in RAM‐activated processes. Indeed, the use of 3 mm ZrO2 beads outperformed in comparison with the denser and harder beads in stainless steel (Table S6, entries 1–3, Supporting Information).

Indeed, the one‐pot/one step 3‐CR, performed with 3 mm ZrO2 balls on 12.5 g scale afforded a full conversion of the starting materials and a 21% yield of Biginelli product (2), determined by 1H NMR analysis (Table S6, entry 1, Supporting Information). In these non‐optimized conditions, the yield remained low also because of the poor rheology of the mixture, becoming a dense paste, hampering the reaction to proceed. However, in an identical 1.2 g scale reaction (Table S6, Supporting Information, entry 2), no formation of (2) could be observed and the conversion, determined by 1H NMR, stopped at 67%. In this case, the corresponding Knoevenagel condensation by‐product (identified by GC‐MS) was formed upon reaction between the benzaldehyde and the β‐ketoester, as reported previously in ball‐milling using zeolites as catalysts.[ 26 ] Lower conversions were also obtained by replacing ZrO2 by an equivalent weight of stainless steel balls (Table S6, Supporting Information, entries 1–2 vs 3) or by a two‐step addition of the reagents in a cascade sequence, with or without the assistance of milling balls (Table S6, Supporting Information, entries 14 and 15).

With the aim to improve the yield, another set of experiments focused on the selection of a suitable solid acidic catalyst (Table S6, Supporting Information, entries 4–13), the Biginelli reaction in solution being reported as an acid‐catalyzed process. Among the acidic catalysts tested, p‐toluenesulfonic acid (10 mol%) delivered a slightly improved 34% yield (determined by 1H NMR, Table S6, Supporting Information, entry 6), with no improvement by adding ZrO2 balls (Table S6, Supporting Information, entries 10–12), and independently on the order of addition of the reagents (by a one‐pot/one step 3‐CR or by a two‐step cascade sequence).

All‐in one, yields remained low to moderate in all the tests performed at small scale reaction (1.2 g), sometimes failing to deliver the target compound (2), independently on the chemical and process conditions used, except when the reaction scale was 10‐fold (i.e., up‐scaling) and with the presence of beads (i.e., by GA‐RAM), significantly improving the mixing of the reagents once the viscous paste that was formed.

To confirm these experimental findings, the reaction was repeated on a much bigger scale still using 3 mm diameter zirconia beads, to increase the extent of mixing. Therefore, a 1:1.2 reagents to beads ratio was used (90 g of zirconia beads were used for ≈84.0 g of mixed reagents), and the glass vial was replaced by a 150 mL HDPE reaction vessel. The reaction was run at 100 g for 10 min total mixing time (two cycles of 5 min each, with a rest time of 10 min in between). The reaction crude was analyzed by 1H NMR, showing the appearance of two distinct singlets at 5.2 ppm, characteristic for the C‐H hydrogen and the N1‐H singlet at 9.2 ppm within the dihydropyrimidone structure (2).

Non‐ambient or variable temperature XRD (VT‐XRD) showed changes in the Bragg reflections at 21.3 (at 90 °C) and 22.4 (at 100 °C), with no other noticeable phase changes or transitions after and up to 190 °C, suggesting that only one stable form was prepared by GA‐RAM (Figure 5 ). The formation of a hydrate phase cannot be excluded, based on the cascade reaction mechanism for Biginelli reaction, generating two equivalent of water, one of which already in the first step, due to the formation of the imine intermediate between the benzaldehyde and urea.[ 27 ] Indeed, the formation of crystallization water in similar condensation steps was previously described,[ 28 ] as well as its removal upon heating under vacuum at 80 °C during several hours.[ 29 ]

Figure 5.

Spectroscopic characterization of dihydropyrimidinone (2), prepared by GA‐RAM process: VT‐XRD analyses showing how the temperature ramping affects dihydropyrimidinone (2) structure.

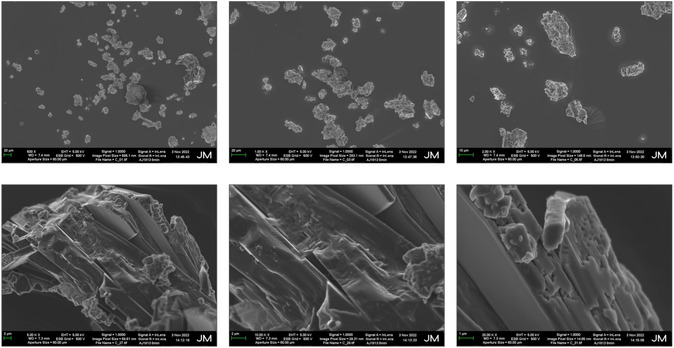

SEM analyses (Figure 6 ) performed on recrystallized dihydropyrimidinone (2) confirmed its crystallinity, also giving insight in its morphology, constituted by straight‐edged cuboidal structures.

Figure 6.

Characterization of dihydropyrimidinone (2) by scanning electron miscroscopy (SEM). Images at different range of magnifications.

Despite that the reaction conditions under GA‐RAM were not optimized, the conversion of starting materials was not complete, and the recovery of the product required a crystallization by hot EtOH, the results could be considered satisfying in terms of throughput, with ≈23 g (31% yield, 1st recrystallisation round) of dihydropirimidone (2) obtained selectively in only 10 min reaction and with no other by‐products observed in the crude.

Any other experiment conducted at lower acceleration (g), for longer reaction times delivered worst results, due to a lack of efficient mixing hampered by the formation of a sticky paste.

The kinetic studies performed for vanillin barbiturate (1), in solution by 1H NMR and at the solid state by FT‐IR, were also performed in the case of the MCR leading to ethyl 1,4‐dihydro‐2‐hydroxy‐6‐methyl‐4‐phenyl‐5‐pyrimidine carboxylate (2) (respectively Figure S5 and S6, Supporting Information) were conducted. Also in this case, no traces of the target compound (2) could be observed after 24 h, in DMSO‐d 6), confirming the previous findings.

These preliminary investigations to prepare dihydropyrimidinone (2) were functional to the preparation of the biologically active[ 25 ] (±)‐Monastrol (3).

Previously reported solvent‐based Biginelli 3‐CR to (±)‐Monastrol (3) indicated as efficient, protocols based on microwave activation,[ 30 ] also without a solvent,[ 31 ] in the presence of a Lewis‐acid catalyst (e.g., Yb(OTf)3, [30a] LaCl3, [30b] Zr‐pillared clay,[ 31 ] or p‐TsOH[ 32 ]). Metal‐free, biomass‐derived nano‐architectured carbon quantum dots[ 33 ] were also used as catalysts with excellent yields. However, the aforementioned endeavors made use of solvents and needed heating from 60 to 120 °C to drive the reaction toward completion (during 30 min–2 h).

To our best knowledge, no mechanochemical preparation of (±)‐Monastrol (3) has been performed so far. Therefore, having successfully improved the GA‐RAM Biginelli 3‐CR to dihydropyrimidinone (2), the method was adapted to the preparation of (±)‐Monastrol (3) (Scheme 2 and Table S7, Supporting Information).

Three different test reactions on a 5 g scale were carried out, to understand the influence of both chemical (e.g., the use of p‐TsOH as catalyst) and process parameters (e.g., use of 3 mm ZrO2 beads as grinding media) in combination or not (Table S7 and Figure S15, Supporting Information). As a results, in the best conditions (Table S7, Supporting Information, entry 3), (±)‐Monastrol (3) was obtained in a 55% isolated yield by reacting equimolar amount of the reactants, with p‐TsOH (10 mol%) as catalyst, during 45 min at 100 g. A slightly lower, but still comparable 51% yield was obtained when increasing the mixing events by using 3 mm ZrO2 grinding media (entry 2). Clearly, the chemical parameters more than processing conditions drive the reaction to better conversion and yield. Indeed, without catalyst, but in the presence of grinding media (entry 1), the yield dropped to 37%. Worth of note is that the Biginelli 3‐CR performed better when thiourea (leading to (±)‐Monastrol 3) was used instead of urea (leading to 2), as demonstrated by comparative experiments carried out in identical reaction conditions (Table S6, Supporting Information, entries 1, 6, and 10 vs Table S7, Supporting Information, entries 1–3).

These findings confirmed that the chemical parameters, including the change in rheology of the reaction mixture during mixing, are those mostly influencing the outcome of the reaction. Indeed, in the preparation of (2) the starting materials consist of two liquids, turning into a dense as described earlier, while in the synthesis of (3), the reactants are solids, except for the β‐ketoester, with the final mixture consisting of a viscous liquid. Noteworthily, the filling degree of the vessel influenced the outcome of the reaction, with, 80% being the optimum value for good mixing in both cases.

As for the dihydropyrimidone (2), also in the case of (±)‐Monastrol (3), the yield was increased upon scaling‐up. Indeed, the reaction performed in a ≈82 mmol scale (27.0 g of total mass of reagents) delivered an improved 61% yield, supporting the evidence that by increasing the reaction scale, higher energy could be delivered during the reagent mixing.

Kinetic studies by 1H NMR in solution showed no reaction after 24 h, or by simple contact of the reagents for 45 min, as evidenced by solid‐state FT‐IR (ATR device) analyses (respectively Figure S7 and S8, Supporting Information).

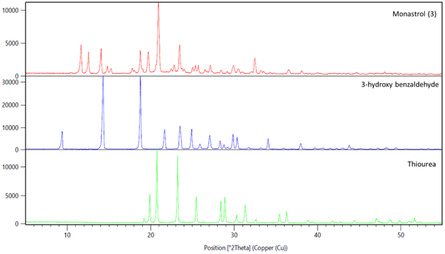

After a straightforward work‐up, based on precipitation of (±)‐Monastrol (3) in a 1:3 v/v mixture of EtOH/H2O, the off‐white powder was analyzed by PXRD (Figure 7 and Table S8–S10, Supporting Information). Even though the diffraction patterns for (±)‐Monastrol (3) are well defined, potential amorphous content can not be excluded.

Figure 7.

PXRD analyses showing stacked diffraction patterns of starting materials thiourea (green), 3‐hydroxy‐benzaldehyde (blue) and (±)‐Monastrol (3) prepared by GA‐RAM. The list of the most intense peaks for each compound is indicated in Tables S8–S10, Supporting Information).

To the best of our knowledge, no data are available for the solid‐state characterization of (±)‐Monastrol (3) and its preparation by mechanochemical methods have not been disclosed so far, paving the way for a “Safe and Sustainable by Design” (SSbD) synthesis of biologically active compounds via MCR, via a special emphasis of RAM activation processes, still at the early stage of its use for green organic chemistry synthesis.

Challenging the RAM‐assisted activation for organic transformations, the investigation was pursued by exploring an additional reaction still involving a condensation reaction, followed by an intramolecular rearrangement, and based on the Biltz synthesis.[ 9 ]

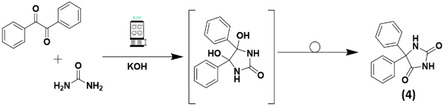

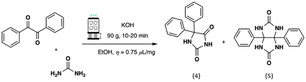

2.3. Biltz Synthesis to the Antiepileptic Phenytoin

The manufacturing solvent‐based route to Phenytoin is based on the Biltz method.[ 9 ] Mainly used for accessing 5,5‐disubstituted hydantoins,[ 34 ] it involves the condensation reaction between stoichiometric quantities of benzil and urea in alkaline conditions and in ethanolic solution, followed by an [1,2]‐intramolecular phenyl shift. Due to its importance for the World Health Organization (WHO),[ 35 ] the synthesis of the antiepileptic drug Phenytoin (5,5‐diphenyl hydantoin) was previously reported by ball milling (at laboratory scale) by both Biltz and Reads methods,[ 36 ] with the mechanism at the solid‐state investigated few years later, by in situ Raman spectroscopy.[ 37 ] Herein, its synthesis by RAM is described, paving the way to a still unexplored field of investigation related to the molecular rearrangements by RAM, never explored so far in the current literature (Scheme 3 and Figure S20, Supporting Information), and only in the recent years started to be explored by mechanochemical processes other than RAM.[ 38 ] Mechanochemical rearrangements[ 38 , 39 ] are valuable tools that facilitate the synthesis of several APIs and provide an exceptional method for their derivatization, the installation of different chemotypes in existing compounds and further exploration of the chemical space. Their potential within mechanochemical conditions has been recently highlighted,[ 38 ] and in contrast to methods in solution, requiring highly energetic conditions under reflux at high temperatures, their access by ball milling is usually quite successful, avoiding harsh reaction conditions and long reaction times, and providing more sustainable processes with improved green chemistry metrics,[ 12 ] for the lab‐scale preparation of APIs such as the anticonvulsant ethotoin[ 40 ] (by Lossen rearrangement) and the analgesic paracetamol (by Beckmann rearrangement).[ 41 ] Recently, the Beckman rearrangement was reported in batch (using a beads mill)[ 4 ] and in continuous (by TSE)[ 42 ] for the sustainable and multigram scale of the WHO essential medicine paracetamol.[ 35 ]

Scheme 3.

Biltz rearrangement to Phenytoin (4) by RAM.

Herein, we report the multigram‐scale preparation of Phenytoin by RAM, investigating and optimizing all the chemical and processing parameters.

The first set of experiments aimed to identify if, other no‐hygroscopic bases could be used instead of KOH. Therefore, equimolar amounts of benzil and urea were reacted by RAM at 100 g, in the presence of bases such as KOH, CaO, K2CO3 and t‐BuOK, during 180 min (Table 1 ). A visual inspection of the sample after the reaction showed that a homogeneous mixing occurred when K2CO3 and t‐BuOK were used, while in the presence of KOH or CaO as a base, the aspect of the was quite different. When performing the reaction with KOH, a very hard agglomerate was formed, while with CaO, the reagents separated into different layers inside the glass vial. The outcome of the synthesis depended not only the proper choice of the base but also the rheological behaviors of the reaction mixture (Table 1).

Table 1.

Screening of the base for Biltz synthesis to Phenytoin (4) by RAM.a)

| Entry | Base | Yield [%]b), c) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | CaO | n.r. |

| 2 | K2CO3 | n.r. |

| 3 | t‐BuOK | n.r. |

| 4 | KOH | 46 |

| 5 | KOHd), g) | 52g) |

| 6 | KOHe) | 48 |

| 7f) | KOHf) | 60 |

| 8 | KOHg) | 43 |

| 9h) | KOHh) | 55h) |

Reaction was conducted in a 10 mL screw cap glass vial. Reaction conditions: benzil (5.35 mmol,1.0 equiv.), urea (5.35 mmol, 1.0 equiv.) and KOH (10.7 mmol, 2.0 equiv.) were accelerated at 100 g during 180 min;

The yield refers to the isolated product after work‐up. Work‐up: the RAM crude was dissolved in water and the precipitate, consisting of unreacted benzil and 3a,6a‐diphenylglycoluril[ 37 ] (5) (c.f., Table 3 and Supporting Information), was filtered off. The water filtrate was acidified with an aqueous solution of 10% citric acid till pH 4. Phenytoin (4) precipitated off, it was filtered and washed with water till neutral pH, then dried in vacuo in the presence of P2O5;

n.r. = No reaction;

Benzil and urea were pre‐grinded in a mortar before the reaction;

The reagents (benzil and urea) and the base were pre‐mixed at 60 g during 5 min;

The mixing occurred by three cycles of 60 min. each, with 5 min rest in between each cycle. The hard agglomerate formed after each cycle was scratched manually, before the subsequent mixing cycle;

KOH (4.0 equiv.) were used;

The potassium ureate salt[ 37 ] was formed first by mixing 1 urea (1.0 equiv.) and KOH (2.0 equiv.) at 80 g for 60 min, leading a deliquescent viscous liquid, then benzil was added and the mixture was reacted at 100 g during 180 min.

Therefore, Phenytoin (4) could be obtained in 46% yield only in the presence of KOH (entry 4) after a straightforward work‐up based on precipitation in acidified water, followed by filtration in vacuo. However, the yield remained limited, due to the rheological changes of the starting materials during mixing, with the formation of a rock‐hard material hampering the full conversion of the reactants and stopping the reaction no mixing was further possible. A slight better improvement, leading to 52% yield of Phenytoin (4) was observed when benzil and urea were pre‐grinded in a porcelain mortar (entry 5) or by RAM (entry 6), to achieve more effective mixing and shearing of the powders during the RAM reaction.

However, pre‐grinding of the reagents was not considered a crucial parameter for improving the rheological properties of the mixture and the reaction yield, therefore, the optimization study was continued without any pre‐grinding. The reaction was not improved even by doubling the amount of base (entry 8). The better results were obtained by carrying out the mixing during three cycles of 60 min each, with a resting time of 5 min in between each cycle (entry 7). A hard agglomerate was formed after each cycle; therefore, the powders were manually scratched before starting the subsequent cycle.

Speculating that the major problem hampering the full conversion of the reactants was due to the poor rheology of the mixture, and being known that potassium ureate is a viscous clear liquid,[ 37 ] the Biltz reaction was divided into two separate steps, the first one involving the formation of the more nucleophilic salt potassium ureate at 80 g during 30 min, followed by the addition of benzil (entry 9), leading to 55% yield of Phenytoin (4), confirming that the presence of a viscous state was effective for a more efficient mixing and hence, increased yield.

Therefore, the effect of the addition of liquid additives was investigated screening green or biomass‐derivative solvents such as H2O, EtOH, or glycerol in a liquid‐assisted RAM (LA‐RAM) [7c] process, arbitrarily choosing η = 0.5 μL mg−1, and slightly decreasing the acceleration g from 100 to 90 (Table 2 , entries 1–3). Compared to the neat reaction conditions (Table 1, entry 4), the addition of H2O or glycerol led to worst results, while improved yields were obtained by addition of EtOH (Table 2, entry 3) resulting in a 67% GC‐MS yield. In a comparative experiment, pre‐grinded KOH (entry 7) was used, increasing the yield to 81% (entry 7) in half of the time (90 min). The better outcome could be due to the reduced size of KOH particles, probably displaying a better surface area and thus increased efficiency upon mixing. Based on the preliminary screening of LAG solvent (entries 1–3), EtOH was selected for further LA‐RAM investigations, aimed to determine the optimum η value (entries 4–8) and the shortest reaction time (entries 8–11). A selection of data is given in Table 2 (and Figure S21, Supporting Information).

Table 2.

Screening of the liquid additives for Biltz synthesis to Phenytoin (4) by RAM.a)

| Entry | Influence of | Liquid additive | η [μL mg−1] | Time [min.] | Yield [%]b) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | LAG solvent | H2O | 0.5 | 180 | 14 |

| 2 | Glycerol | 0.5 | 180 | n.r.c) | |

| 3 | EtOH | 0.5 | 180 | 67 | |

| 4 | η value | EtOH | 0.05 | 90 | 41 |

| 5 | EtOH | 0.1 | 90 | 24 | |

| 6 | EtOH | 0.25 | 90 | 39 | |

| 7d) | EtOH | 0.5 | 90 | 81 | |

| 8 | EtOH | 0.75 | 90 | 99 | |

| 9 | Reaction time | EtOH | 0.75 | 60 | 99 |

| 10 | EtOH | 0.75 | 20 | 98 (79%)e) | |

| 11 | EtOH | 0.75 | 10 | 26 |

Reaction was conducted in a 10 mL screw cap glass vial. Reaction conditions: benzil (5.35 mmol, 1.0 equiv.), urea (5.35 mmol, 1.0 equiv.) and KOH (10.7 mmol, 2.0 equiv.) were accelerated at 90 g during 180 min, except when otherwise specified;

Yields were calculated by quantitative GC‐MS using a linear calibration curve obtained by using commercial phenytoin, except when otherwise specified (see Supporting Information for more details);

n.r. = No reaction;

Pre‐grinded KOH was used;

Isolated yield.

The better results were obtained at 90 g acceleration during 90 or 60 min, with an optimal value of η = 0.75 μL mg−1 (entries 8 and 9 respectively, and Figure S21, Supporting Information), leading to 99% GC‐MS yield (i.e., ≈9.0 g of pure Phenytoin (4) after work‐up), with a comparable result in only in 20 min reaction (entry 10), the yield drastically dropping for 10 min reaction (entry 11), with only 40% conversion of the reactants.

For η = 0.75 μL mg−1, the visual inspection of the crude after the reaction indicated the formation of a viscous bleu liquid (indicative of the formation of the desired Phenytoin (4), Figure S21, Supporting Information) and an overall increase of the temperature of the vial (≈80 °C) was observed upon contact. Therefore, the presence of favorable rheologic properties, together with additional thermal activation might have allowed the access to the energetic state required to promote the benzylic rearrangement to Phenytoin (4).

Finally, the study was completed studying the impurities potentially formed during the LA‐RAM preparation of Phenytoin (4) at different scale, particularly finalized to identify the presence of 3a,6a‐diphenylglycoluril (5) as by‐product, known to be formed both in solution[ 9 ] and by ball milling[ 36 , 37 ] (Table 3 ).

Table 3.

Selectivity study for Biltz reaction by LA‐RAM synthesis.

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Time [min.] | Conversion [%] | Yield [%] | Phenytoin (4) / 3a,6a‐Diphenylglycoluril (5) |

| 1a) , b) | 60 | 100 | 99 | 1:0.01d) |

| 2a) , b) | 20 | 100 | 98 | 1:0.04d) |

| 3b) , c) | 10 | 100 | 97 | 1:0.02e) |

Reaction conditions: benzil (5.35 mmol,1.0 equiv.), urea (5.35 mmol, 1.0 equiv) and KOH (10.7 mmol, 2.0 equiv.) were accelerated at 90 g for the specified time. Yields were calculated via quantitative GC‐MS using a linear calibration curve obtained by using commercial phenytoin, except when otherwise specified;

Yield refers to isolated product after the work‐up of the reaction (as described already in Table 2);

Reaction scale was benzil (35.68 mmol, 1.0 equiv.), urea (35.68 mmol, 1.0 equiv.) and KOH (71.35 mmol, 2.0 equiv.);

Determined by 1H NMR integrals associated to protons of the phenyl rings for Phenytoin (4)[ 36 ] and accordingly the corresponding protons for 3a,6a‐diphenylglycoluril (5);[ 37 ]

Determined by the mass in g obtained after the work‐up for each product.

Therefore, independently on the reaction scale, the amount of by product 3a,6a‐diphenylglycoluril (5) remained constant, and anyway really limited. It is worth noticing that much better results were obtained upon increasing the reaction scale, confirming the tendencies observed so far when up‐scaling compounds (1–3). Indeed, in the optimized reaction conditions (90 g, η = 0.75 μL mg−1), by increasing the reaction scale from 5.35 to 35.7 mmol, 15 g of Phenytoin (4) could be obtained in only 10 min with a full conversion of the reactants and a much higher yield (97%, Table 3, entry 3) compared to the same reaction on a seven times less smaller scale during 10 min, which delivered poor conversion (40%) and a lower yield (26%, Table 2, entry 11).

The more efficient energy transfer through the shearing of the particles at higher total mass may account for the acceleration of the reaction and the better yields. These results also show that the preparation of Phenytoin (4) by LA‐RAM was successful, and potentially scalable to higher amount, in view of the implementation of RAM technology for the preparation of other marketed APIs.

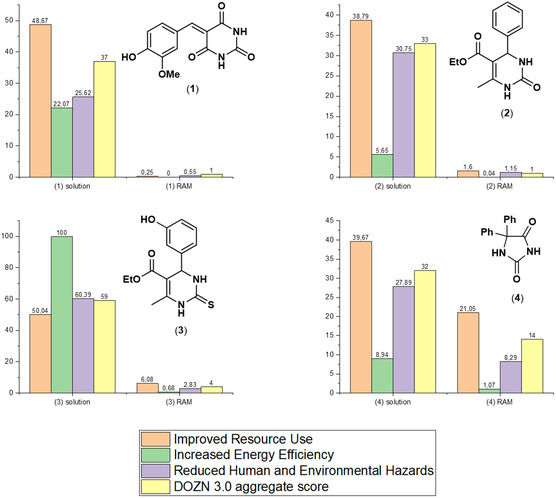

In view of the relevance of crystalline forms in the pharmaceutical field,[ 43 ] the batch of Phenytoin (4) prepared by LA‐RAM at large scale (35.7 mmol, Table 3, entry 3) was analyzed by ATR FT‐IR spectra (Figure S22, Supporting Information) and PXRD (Figure 8 and Table S11, Supporting Information) and the data were compared with the spectral characteristics of a commercial sample of phenytoin. Thermogravimetric (Figure S19, Supporting Information) and quantitative 1H NMR qNMR analyses were performed to assess the purity of Phenytoin (4). As a result, the purity of Phenytoin (4) was 92%, based on the essay using mesitylene of reference.[ 44 ] The PXRD peaks shows that Phenytoin (4) shared the same crystal structure of the commercial sample (same polymorph), and even though, the presence of an amorphous phase cannot be excluded, the PXRD patterns were in accordance with those previously reported,[ 45 ] and supporting that the reaction occurred by RAM, rather than in solution.

Figure 8.

Comparison of PXRD patterns of Phenytoin (4) obtained by large‐scale LA‐RAM with the reactants (benzil and urea) and a commercial batch of phenytoin (the list of peaks for each compound is given in Table S11–S13, Supporting Information).

Then, the environmental impact of the RAM‐assisted syntheses of compounds (1–4) was compared with the corresponding solution‐based counterparts using green chemistry metrics.

2.4. Green Metrics Calculations for RAM‐Assisted Reactions

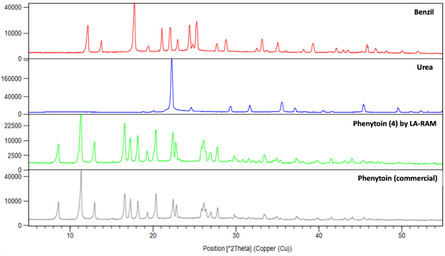

Green chemistry metrics encompass a set of indicators employed to characterize various aspects pertaining to the principles of green chemistry within a specific chemical process. To the best of our knowledge, the assessment of the greenness of RAM‐assisted protocols (often assimilated to mechanochemical methods) by green chemistry metrics and its comparison with the corresponding solution‐based counterparts were never reported so far. Herein, green chemistry metrics[ 12 ] were calculated for all the RAM‐assisted reactions using the most recent and efficient methods making use of Chem 21[ 10 ] (Table 4 ) and DOZN 3.0[ 11 , 46 ] (Figure 9 ) toolkits, to investigate their sustainability profiles. As a result, compared to classic solution synthesis, the use of RAM as enabling technology outperformed not only in terms of productivity (higher throughput), reaction times and yield, but also for better green chemistry metrics.

Table 4.

Comparison of green chemistry metrics by Chem21 toolkit for solution‐based vs RAM‐assisted reactions in the preparation of compounds 1–4.a)

| PRODUCT (Solution synthesis vs RAM conditions) | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| METRICS |

(1) |

(2) |

(3) |

(4)b) |

||||||||

| AE | 85.7 | vs | 90.7 | 79.8 | vs | 87.8 | 74.3 | vs | 89.0 | 79.2 | vs | 93.3 |

| RME | 81.4 | vs | 87.7 | 75.8 | vs | 27.1 | 63.9 | vs | 54.7 | 77.6 | vs | 90.8 |

| OEc) | 95.0 | vs | 96.7 | 95.0 | vs | 30.9 | 85.9 | vs | 61.4 | 97.9 | vs | 97.3 |

| PMI | 176.0 | vs | 1.1 | 123.3d | vs | 5.4 | 910.7 | vs | 20.3 | 221.6d) | vs | 93.9 |

| E‐factor | 175.0 | vs | 0.1 | 122.3d) | vs | 4.4 | 909.7 | vs | 19.3 | 220.6d) | vs | 92.9 |

| Solvent | H 2 O, EtOH, Et 2 O | No solvent | EtOH, CHCl 3 | EtOH | Acetone , CH 3 CN, CHCl 3 | H 2 O , EtOH | H 2 O, DMSO | EtOH, H 2 O | ||||

| Work‐up, recovery | Filtration (Boiling H 2 O, EtOH, Et 2 O) | Filtration | Filtration Recryst.ss | Filtration | Chromat. | Filtration | Filtration, HCl neutralization | Filtrat., Acidif. | ||||

| Health & safety | ||||||||||||

| Main hazard statements | H225, H319 | H310, H330, H351 | H302, H332, H225 | H310, H330, H411 | H315, H225, H302 | |||||||

| H224 | H290 | H290 | H319 | |||||||||

The optimum value for AE, RME and OE is 100%; for E‐factor the optimum value is 0, with PMI = E‐factor +1[ 51 ] When comparing two processes, the one with the lowest PMI will be the greenest;

Green metrics calculations for the RAM process were performed with the data from the synthesis indicated in Table 3, entry 3;

, where RME and AE are the values described above;

Estimated from the solubility data of the compound in the solvent used (c.f., ESI). Legend: Green flag : Preferred; Amber flag : Acceptable with some concerns; Red Flag : Undesirable.

Figure 9.

Comparison of solution‐based versus RAM‐assisted synthesis by DOZN 3.0 quantitative scoring tool[ 11 , 55 ] for compounds 1–4. Legend: Group 1 (Improved Resource Use ‐ orange), Group 2 (Increased Energy Efficiency ‐ green), Group 3 (Reduced Human and Environmental Hazards ‐ violet) and Aggregate score (yellow).

Assessment by Chem21 provides indicators on the sustainability of reactions by considering a broad range of both quantitative and qualitative criteria to evaluate their environmental friendliness. For instance, the quantitative factors include yield, selectivity, metrics such as atom economy (AE),[ 47 ] reaction mass efficiency (RME),[ 48 ] optimum efficiency (OE),[ 10 ] process mass intensity (PMI),[ 49 ] and E‐factors.[ 50 ] Herein, these parameters were calculated for compounds 1–4, prepared by both solution methods and RAM‐assisted syntheses, to compare the environmental footprint for each of the synthetic approach (Table 4 and Excel spreadsheet, Supporting Information). Worth of note is the integration of OE, which facilitates a direct comparison of various reaction types, a comparison that may not may not consistently align with (AE) or RME. This is because some chemical processes inherently demonstrate atom or mass efficiency, while others do not, making OE a more versatile metric for evaluating diverse chemistries.[ 51 ]

The qualitative criteria help evaluate energy efficiency, safety, and potential environmental and health risks. The scoring system uses clear, visual indicators that are easy to interpret. Each criterion is assigned a green, amber, or red “flag,” where green indicates “preferred,” amber means “acceptable with some concerns,” and red signifies “undesirable” (Table 4).

For the solution syntheses of compounds (1),[ 18 ] (2),[ 52 ] (3) [30a] and (4),[ 53 ] the calculations of the green metrics using Chem21 toolkit were performed based on the experimental procedures reported in literature, selecting the highest yielding reactions of the current literature. Weather the amounts of solvents used in the work‐up were not indicated in the original experimental protocol in solution, the calculations were done based on an estimation of the minimum amount of solvent required for the recovery of the target compound (i.e., recrystallization, neutralization, and liquid–liquid extraction), based on the solubility of the compound in the solvents used at each step.

As data in Table 4 (and Excel spreadsheets in the Supporting Information) clearly indicate, green metrics like AE, E‐factor and PMI were within the optimum value for the RAM‐assisted synthesis of all the targets (1) to (4), indicating the better ecological footprint of the RAM‐based mechanochemical methods, not making use of solvent, metal catalysts or critical elements. They also displayed a better energetic profile (green flag) while no heating was needed to activate the reactions or for the recovery of the product during the work‐up (green flag), also avoiding purification by column chromatography, or the use of acidic solutions. Additionally, for all the compounds (1–4) the health and safety profiles for the RAM processes (amber flag) were much better in comparison with the solution‐based synthesis (red flag). Weather a solvent was used for the liquid‐assisted processes (LA‐RAM), the choice turned to EtOH, considered not harmful, to water, for the recovery of the product by precipitation/filtration.

In the case of RME, the green metric values for the RAM‐assisted syntheses were better for compounds (1) and (4), while solution‐based processes delivered better values for compounds (2) and (3). In these cases, even though solution‐based methods indicated (apparently) a better use of resources, RME for compound (2) was calculated only on the first round of recrystallization, and not on the total amount of product that could be obtained by carrying out several subsequent recrystallizations.

For (±)‐Monastrol (3), the slightly better RME value for solution‐based versus RAM method (63.9 vs 54.7, respectively) is due to the slightly lower yield obtained by RAM (61%) in comparison with the 86% yield obtained in solution. However, even if RME is unfavorable for the RAM syntheses of (2) and (±)‐Monastrol (3) in comparison with the solution‐based process, considerations on the sustainability of a process based only on one green metric risk to be biased.

Indeed, the solvents used in post‐reaction treatments are not accounted in the calculations of RME, defined by the ratio Mass of product (Kg)/Total mass of reagents (Kg). while the green metrics AE, E‐factor and PMI, which also account for the solvents used in the work‐up (extractions) and the recovery of the products (e.g., by column chromatography), indicate a generally better ecological footprint for the RAM processes (Table 4) also for compounds (2) and (±)‐Monastrol (3), with an easier work‐up and recovery, allowing to keep the amount of solvents to the minimum. Similar considerations apply to OE green metric for both compounds, being OE linearly dependent on RME values (c.f., Table 4, legend).

Assessment by DOZN 3.0 tool (Figure 9, Table S14 and S15, Supporting Information, and Excel spreadsheet in the Supporting Information). The 12 Principles of Green Chemistry and Green Engineering were previously categorized based on their relevance to scaling up mechanochemical processes,[ 54 ] however, the principles are conceptual and qualitative. In a seminal article, the quantitative and harmonized assessment of mechanochemical processes against the 12 Principles of Green Chemistry (in batch by ball mills and in continuous by twin screw extrusion) and the comparison with solution‐based methods was reported for the preparation of nitrofurantoin,[ 55 ] an antibacterial agent listed as essential medicine by WHO.[ 35 ] Later on, this approach was applied to the evaluation of other biologically relevant compounds such as 1,4‐dihydropyrimidines[ 56 ] (1,4‐DHP) and the rac‐ibuprofene:nicotinamide cocrystal[ 57 ] prepared by mechanochemical methods making use of ball mills and vibrating eccentric mills. However, to the best of our knowledge, no reports deal with the (qualitative or quantitative) assessment of RAM‐assisted reactions against the 12 principles of green chemistry.

Therefore, the evaluation of the green metrics using the DOZN 3.0 Quantitative Scoring Analysis software was also performed for all the methods (in solution and by RAM), for which the data were available (Figure 9).

DOZN tool takes into account the 12 Principles of Green chemistry[ 58 ] and evaluates them by dividing in 3 groups: 1) Group 1: Improved resource use, where the principles (#) taken into account are the 1, 2, 7, 8, 9, and 11; 2) Group 2: Increased energy efficiency, accounting for principle 6 and evaluating the deviation from ambient conditions with regard to temperature and pressure; and 3) Group 3: Reduced human and environmental hazards, which includes principles 3, 4, 5, 10, and 12 and measures the amount of waste generated, its severity, and the hazard level of the final product. For each group of principles, a score is generated and normalized to an aggregate score, accounting for the “greenness” of each process, with the optimal value usually being below 1 and the closest as possible to zero. Moreover, when comparing two processes, the one with the lowest aggregate score will be the greenest.

As data in Figure 9 (Table S14 and S15, and Excel spreadsheet, Supporting Information) indicate the direct comparison of the DOZN 3.0 scores for the preparation of compounds (1) to (4) by RAM and in solution. The DOZN 3.0 scores show that the RAM syntheses are eco‐friendlier and more economic (# 2, # 4, and # 7), less hazardous and inherently safer (# 1, # 3, #5, and # 12), and more efficient (# 6) with respect to their solvent‐based counterparts, all scoring exceptionally better in all the categories (Groups 1–3 and aggregate scores; Table S15, Supporting Information), and confirming the better AE (Table S14, Supporting Information) for all the RAM‐activated processes and their globally lower environmental impact.

All the processes, by RAM and in solution, use of the same reactants to make the same products (1–4) but the scores are always in favor of the RAM processes. The difference in scores arises from the amount and the nature of the solvents needed for the reaction, the work‐up and the purification (for the solution‐based syntheses), and in the case of compounds (1–3), also by the need of raw materials in excess affecting Group 1 score.

3. Conclusion

It is well recognized that mechanochemistry can play a role in mitigating climate change by enabling research approaches that support the transition to a more resource‐efficient use.[ 59 ] The implementation of mechanochemical methods for organic synthesis (both in batch and in continuous) is continuously growing worldwide, also permitting access to compounds not easily prepared (on not possible to be prepared) in solution.[ 60 ] In comparison, resonance acoustic mixing (RAM) as a method for organic synthesis has yet a lot to be discovered. In this work, three key and representative organic reactions (Knoevenagel condensation, Biginelli 3‐CR, and rearrangement by Biltz method) were investigated for the first time and the use of grinding‐assisted RAM (GA‐RAM), alone or in combination with LA‐RAM process, reported. The in‐depth investigation of these reactions in both terms of reactivity and mechanochemical activation using RAM has unveiled some key aspects of the use of this technique and was applied to prepare biologically active compounds, such as the anticancer prototype drug (±)‐Monastrol (3), and the antiepileptic drug Phenytoin (4), listed as WHO essential API.[ 35 ] The [1,2]‐intramolecular benzylic rearrangement leading to marketed Phenytoin (4) is the first RAM‐assisted rearrangement nowadays reported. Trying to translate these results even further than their significantly easy protocols and reaction workup, their ecological footprint was also assessed by green chemistry metrics using freely available tools such as CHEM21 and DOZN 3.0.

As a result, all the RAM‐activated reactions herein reported were found to be “greener”, more efficient, more eco‐friendly, with a better use of resources, and producing much less waste than the ones performed in solution, outperforming in terms of yield upon up‐scaling. Even when yields remained low to moderate, as in the case of compounds (2) and (3), these reactions represent the proof‐of‐concept on the potential of RAM in the sustainability sphere.

The minimalistic characteristics of RAM experimental set‐up and its operational simplicity, as for the currently used milling devices, make RAM technology one of the possible choices to conduct mechanochemical organic syntheses. Indeed, activation by RAM is an additional and complementary approach to (and not a replacement of) the mechanochemical technologies and tools already on the market, sharing with them the potential reduction in energy consumption, possibly enhancing environmental and human health outcomes, and in some cases, achieving higher productivity compared to traditional solution‐based methods, as demonstrated herein in the preparation of the marketed antiepileptic drug Phenytoin (4).

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

C.M.C. and S.M.S. contributed equally to this work. The authors would also like to thank Stephen Day (SSNMR), Edward Bilbe and Huw Marchbank (PXRD), Lia JaKyung Murfin and Ofentse Makgae (Electron microscopy) at Johnson Matthey Technology Centre, UK, for carrying out all the characterizations. This article is based upon work from COST Action CA18112 “Mechanochemistry for Sustainable Industry”,[ 61 ] supported by COST (European Cooperation in Science and Technology).[ 62 ] COST (European Cooperation in Science and Technology) is a funding agency for research and innovation networks, helping to connect research initiatives across Europe and enable scientists to grow their ideas by sharing them with their peers. This boosts their research, career and innovation. www.cost.eu. E.C. and C.M.C. acknowledge IMPACTIVE (Innovative Mechanochemical Processes to synthesize green ACTIVE pharmaceutical ingredients),[ 63 ] the research project funded from the European Union's Horizon Europe research and innovation programme (European Health and Digital Executive Agency) under grant agreement No. 101057286.

Contributor Information

Evelina Colacino, Email: evelina.colacino@umontpellier.fr.

Maria Elena Rivas, Email: Maria.Rivas-Velazco@matthey.com.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available in the supplementary material of this article.

References

- 1. Mateti S., Mathesh M., Liu Z., Tao T., Ramireddy T., Glushenkov A. M., Yang W., Chen Y. I., Chem. Commun. 2021, 57, 1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.a) Colacino E., Porcheddu A., Charnay C., Delogu F., React. Chem. Eng. 2019, 4, 1179; [Google Scholar]; b) Pérez‐Venegas M., Juaristi E., ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 8881; [Google Scholar]; c) Ying P., Yu J., Su W., Adv. Synth. Catal. 2021, 363, 1246. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Crawford D. E., Porcheddu A., McCalmont A. S., Delogu F., James S. L., Colacino E., ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 12230. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Geib R., Colacino E., Gremaud L., ChemSusChem 2024, 17, e202301921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.a) Rivas M. E., in Mechanochemistry and Emerging Technologies for Sustainable Chemical Manufacturing, 1st ed. (Eds: Colacino E., Garcia F.), Routledge & CRC Press (Taylor and Francis Group), Boca Raton, FL: 2023, p. 336. ISBN: 978 0367775018; [Google Scholar]; b) Polyak F., JP2023510089A 2023;; c) Cheng W., Jiaqing M., Kun L., Zhanxiong X., Pengpeng Z., Chongwei A., BaoYun Y., Wang J., J. Energy Mater. 2023, 41, 595; [Google Scholar]; d) Hyun J., Pak C., J. Power Sources 2025, 626, 235716; [Google Scholar]; e) Michalchuk A. A. L., Boldyreva E. V., in Encyclopedia of Green Chemistry, Vol. 2, Elsevier, Amsterdam, Netherlands: 2025, pp. 2532–2541. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Michalchuk A. A. L., Hope K. S., Kennedy S. R., Blanco M. V., Boldyreva E. V., Pulham C. R., Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 4033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.a) Gonnet L., Lennox C. B., Do J.‐L., Malvestiti I., Koenig S. G., Nagapudi K., Friščić T., Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202115030; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Gonnet L., Lennox C., Borchers T., Askari M., Wahrhaftig‐Lewis A., Koenig S., Nagapudi K., Friscic T. (Preprint), ChemRivX, 2024, https://doi.org/10.26434/chemrxiv‐22024‐qb26435wr;; c) Lennox C. B., Borchers T. H., Gonnet L., Barrett C. J., Koenig S. G., Nagapudi K., Friščić T., Chem. Sci. 2023, 14, 7475; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Effaty F., Gonnet L., Koenig S. G., Nagapudi K., Ottenwaelder X., Friščić T., Chem. Commun. 2023, 59, 1010; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Wohlgemuth M., Schmidt S., Mayer M., Pickhardt W., Grätz S., Borchardt L., Chem. Eur. J. 2023, 29, e202301714; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Dey A., Kancherla R., Pal K., Kloszewski N., Rueping M., Commun. Chem. 2024, 7, 295; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g) Thorpe J. D., Marlyn J., Koenig S. G., Damha M. J., RSC Mechanochem. 2024, 1, 244; [Google Scholar]; h) Vugrin L., Chatzigiannis C., Colacino E., Halasz I., RSC Mechanochem. 2025, 10.1039/D5MR00016E [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.a) Gonçalves I. L., Rockenbach L., das Neves G. M., Göethel G., Nascimento F., Porto Kagami L., Figueiró F., Oliveira de Azambuja G., de Fraga Dias A., Amaro A., de Souza L. M., da Rocha Pitta I., Avila D. S., Kawano D. F., Garcia S. C., Battastini A. M. O., Eifler‐Lima V. L., MedChemComm 2018, 9, 995; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Kappe C. O., Shishkin O. V., Uray G., Verdino P., Tetrahedron 2000, 56, 1859. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Biltz H., Ber. Dtsch. Chem. Ges. 1908, 41, 1379. [Google Scholar]

- 10. McElroy C. R., Constantinou A., Jones L. C., Summerton L., Clark J. H., Green Chem. 2015, 17, 3111. [Google Scholar]

- 11. DeVierno Kreuder A., House‐Knight T., Whitford J., Ponnusamy E., Miller P., Jesse N., Rodenborn R., Sayag S., Gebel M., Aped I., Sharfstein I., Manaster E., Ergaz I., Harris A., Nelowet Grice L., ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2017, 5, 2927. DOZNTM is a universal tool, suitable for scoring any process, no matter the activation technique used, once the detailed experimental/process conditions are known. The DOZN™ tool is accessible free of charge here: https://bioinfo.merckgroup.com/dozn (accessed April 2, 2025). [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fantozzi N., Volle J.‐N., Porcheddu A., Virieux D., García F., Colacino E., Chem. Soc. Rev. 2023, 52, 6680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Konnert L., Gauliard A., Lamaty F., Martinez J., Colacino E., ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2013, 1, 1186. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kaupp G., Reza Naimi‐Jamal M., Schmeyers J., Tetrahedron 2003, 59, 3753. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lukin S., Tireli M., Lončarić I., Barišić D., Šket P., Vrsaljko D., di Michiel M., Plavec J., Užarević K., Halasz I., Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 13216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.a) Guilherme Buzanich A., Cakir C. T., Radtke M., Haider M. B., Emmerling F., de Oliveira P. F. M., Michalchuk A. A. L., J. Chem. Phys. 2022, 157, 214202; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Bui M., Chakravarty P., Nagapudi K., Faraday Discuss. 2023, 241, 357; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Nagapudi S., Nagapudi K., Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2024, 26, 12545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.95% yield was obtained by recovering the residual vanillin barbiturate (1) stuck on beads.

- 18. Luo Y., Ma L., Zheng H., Chen L., Li R., He C., Yang S., Ye X., Chen Z., Li Z., Gao Y., Han J., He G., Yang L., Wei Y., J. Med. Chem. 2010, 53, 273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Crawford D. E., Miskimmin C. K. G., Albadarin A. B., Walker G., James S. L., Green Chem. 2017, 19, 1507. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Nebalueva A. S., Timralieva A. A., Sadovnichii R. V., Novikov A. S., Zhukov M. V., Aglikov A. S., Muravev A. A., Sviridova T. V., Boyarskiy V. P., Kholkin A. L., Skorb E. V., Molecules 2022, 27, 5659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cindro N., Tireli M., Karadeniz B., Mrla T., Užarević K., ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 16301. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Zhu J., Beinayme H., in Multicomponent Reactions. Wiley‐VCH, Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim: 2005, ISBN: 9783527308064. [Google Scholar]

- 23.a) Blasco M. A., Thumann S., Wittmann J., Giannis A., Gröger H., Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2010, 20, 4679; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Lewandowski K., Murer P., Svec F., Fréchet J. M. J., J. Comb. Chem. 1999, 1, 105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.a) Gomes C., Vinagreiro C. S., Damas L., Aquino G., Quaresma J., Chaves C., Pimenta J., Campos J., Pereira M., Pineiro M., ACS Omega 2020, 5, 10868; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Leonardi M., Villacampa M., Carlos Menéndez J., Chem. Sci. 2018, 9, 2042; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Sahoo P. K., Bose A., Mal P., Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2015, 6994. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mayer T. U., Kapoor T. M., Haggarty S. J., King R. W., Schreiber S. L., Mitchison T. J., Science 1999, 286, 971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Shahid A., Ahmed N. S., Saleh T. S., Al‐Thabaiti S. A., Basahel S. N., Schwieger W., Mokhtar M., Catalysts 2017, 7, 84. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Biginelli P., Gazz P., Gazz. Chim. Ital. 1893, 23, 360. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Colacino E., Porcheddu A., Halasz I., Charnay C., Delogu F., Guerra R., Fullenwarth J., Green Chem. 2018, 20, 2973. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kaupp G., in Organic Solid‐State Reactions with 100% Yield, (Ed. Toda F.), Springer Berlin Heidelberg, Berlin, Heidelberg: 2005, pp. 95–183. [Google Scholar]

- 30.a) Dallinger D., Kappe C. O., Nat. Protoc. 2007, 2, 317; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Glasnov T. N., Tye H., Kappe C. O., Tetrahedron 2008, 64, 2035. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Singh V., Sapehiyia V., Srivastava V., Kaur S., Catal. Commun. 2006, 7, 571. [Google Scholar]

- 32.a) Xu Y., Zhou M., Li Y., Li C., Zhang Z., Yu B., Wang R., ChemMedChem 2013, 8, 1345; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Jin T., Zhang S., Li T., Synth. Commun. 2002, 32, 1847. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Singh A., Singh G., Sharma S., Kaur N., Singh N., ChemistrySelect 2022, 7, e202200942. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Konnert L., Lamaty F., Martinez J., Colacino E., Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 13757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.WHO Model List of Essential Medicines ‐ 23rd list, 2023, https://www.who.int/publications‐detail‐redirect/WHO‐MHP‐HPS‐EML‐2023.2002 (accessed: January 2025).

- 36. Konnert L., Reneaud B., de Figueiredo R. M., Campagne J.‐M., Lamaty F., Martinez J., Colacino E., J. Org. Chem. 2014, 79, 10132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Puccetti F., Lukin S., Užarević K., Colacino E., Halasz I., Bolm C., Hernández J. G., Chem. Eur. J. 2022, 28, e202104409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Virieux D., Delogu F., Porcheddu A., García F., Colacino E., J. Org. Chem. 2021, 86, 13885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Nijem S., Kaushansky A., Pucovski S., Ivry E., Colacino E., Halasz I., Diesendruck C. E., RSC Mechanochem. 2025, in press, 10.1039/D4MR00141A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Porcheddu A., Delogu F., De Luca L., Colacino E., ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 12044. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Mocci R., Colacino E., Luca L. D., Fattuoni C., Porcheddu A., Delogu F., ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 2100. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Baier D. M., Rensch T., Dobreva D., Spula C., Fanenstich S., Rappen M., Bergheim K., Grätz S., Borchardt L., Chem. Methods 2023, 3, e202200058. [Google Scholar]

- 43.a) Braga D., Casali L., Grepioni F., Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 9013; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Braga D., Chem. Commun. 2023, 59, 14052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Pauli G. F., Chen S.‐N., Simmler C., Lankin D. C., Gödecke T., Jaki B. U., Friesen J. B., McAlpine J. B., Napolitano J. G., J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57, 9220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.a) Moriyama K., Furuno N., Yamakawa N., Int. J. Pharm. 2015, 480, 101; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Yuminoki K., Tachibana S., Nishimura Y., Mori H., Takatsuka T., Hashimoto N., Pharmazie 2016, 33, 56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Sharma P., Vetter C., Ponnusamy E., Colacino E., ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2022, 2010, 5110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Li C.‐J., Trost B. M., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2008, 105, 13197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Ribeiro M. G. T. C., Machado A. A. S. C., Green Chem. Lett. Rev. 2013, 6, 1. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Martínez J., Cortés J. F., Miranda R., Processes 2022, 10, 1274. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Sheldon R. A., Green Chem. 2017, 19, 18. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Sheldon R. A., Green Chem. 2007, 9, 1273. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Kuarm B. S., Madhav J. V., Laxmi S. V., Rajitha B., Synth. Commun. 2012, 42, 1211. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Arani N. M., Safari J., Ultrason. Sonochem. 2011, 18, 640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Colacino E., Isoni V., Crawford D., Garcia F., Trends Chem. 2021, 3, 335. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Sharma P., Vetter C., Ponnusamy E., Colacino E., ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 5110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Blazquez‐Barbadillo C., González J. F., Porcheddu A., Virieux D., Menéndez C., Colacino E., Green Chem. Lett. Rev. 2022, 15, 881. [Google Scholar]

- 57. Bodach A., Portet A., Winkelmann F., Herrmann B., Gallou F., Ponnusamy E., Virieux D., Colacino E., Felderhoff M., ChemSusChem 2024, 17, e202301220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Anastas P., Warner J., Anastas P., Warner J., Green Chemistry: Theory and Practice, Oxford University Press, Oxford, NY: 2000, p. 148. [Google Scholar]

- 59.a) Gomollón‐Bel F., Chem. Int. 2019, 12; [Google Scholar]; b) Gomollón‐Bel F., ACS Cent. Sci. 2022, 8, 1474; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Gomollón‐Bel F., Chem. Eng. News 2022, 100, 21; [Google Scholar]; d) Galant O., Cerfeda G., McCalmont A. S., James S. L., Porcheddu A., Delogu F., Crawford D. E., Colacino E., Spatari S., ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 1430. [Google Scholar]

- 60. Porcheddu A., Cuccu F., De Luca L., Delogu F., Colacino E., Solin N., Mocci R., ChemSusChem 2022, 15, e202200362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.a) For more information on COST Action CA18112 ‘Mechanochemistry for Sustainable Industry’ (MechSustInd), https://www.mechsustind.eu/ (accessed: April 2025);; b) Hernández J. G., Halasz I., Crawford D. E., Krupicka M., Baláž M., André V., Vella‐Zarb L., Niidu A., García F., Maini L., Colacino E., Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2020, 8; [Google Scholar]; c) Biela J., Stalla M., Rabe L., Machado D., Evers G., Ansems S., Impact assessment Study on Innovation in COST Actions, November, 2024; https://www.cost.eu/uploads/2025/01/COST-Impact-Assessment-Innovation-112024.pdf (accessed: May 2025).

- 62. COST | European Cooperation in Science and Technology . https://www.cost.eu/ (accessed: April 2025).

- 63.a) IMPACTIVE: Innovative Mechanochemical Processes to synthesize green ACTIVE pharmaceutical ingredients . https://mechanochemistry.eu/ (accessed: January 2025);; b) Saenz de La Torre J. J., Flamarique L., Gomollon‐Bel F., Colacino E., Open Res. Europe 2025, 5, 73. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Material

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available in the supplementary material of this article.