Abstract

Background

Vacuolar myopathy is a muscle disease characterized by inefficient autophagy and the accumulation of intracytoplasmic degradation products in autophagic vacuoles. Acquired vacuolar myopathy associated with monoclonal gammopathy is a novel clinical entity first described in 2019. The objective of the present article is to describe the first case of an acquired vacuolar myopathy associated with lambda light chain myeloma.

Case presentation

A 52-year-old man was admitted to our nephrology department for acute kidney injury and was diagnosed with lambda light chain multiple myeloma. The patient presented with supraventricular arrythmia and developed rapidly progressing muscle weakness of the face and all four limbs, with a myogenic electromyographic pattern. A muscle biopsy highlighted muscle fibre vacuoles and lambda light chain deposits. Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging revealed concentric hypertrophy and subepicardial areas of fibrosis that were suggestive of an infiltrative disease. There were no signs of amyloidosis. Treatment with a combination of bortezomib, lenalidomide and dexamethasone gave a good hematologic response, and the patient recovered near-normal levels of muscle strength in the following six months. The number of episodes of arrythmia decreased.

Conclusion

Clinicians should be aware that lambda light chain myeloma may cause lambda light-chain deposits within muscle fibres and vacuolar myopathy. A corticosteroid-sparing strategy for vacuolar myopathy does not appear to be necessary when the course of the myeloma is favourable. Myopathy associated with monoclonal gammopathy is an emerging entity. Given that monoclonal gammopathy is very common in older adults, the appearance of muscle impairments in this context could prompt the physician to consider the initiation of corticosteroids, immunosuppressive agents, or intravenous immunoglobulins. Electromyography and muscle biopsy results can guide the diagnosis.

Keywords: Case report, Vacuolar myopathy, Lambda-light chain, Myeloma, Monoclonal gammopathy

Background

Vacuolar myopathy (VM) is a muscle disease characterized by inefficient autophagy and thus the accumulation of intracytoplasmic degradation products in autophagic vacuoles that can be seen under the light microscope. Although most cases of VM are caused by a mutation in a gene coding for a lysosomal enzyme [1], acquired VM can also arise after exposure to a drug like hydroxychloroquine [2] or colchicine [3]. In 2019, Allenbach et al. were the first to describe cases of acquired VM associated with monoclonal gammopathy [4]. However, none of the three patients described by Allenbach et al. presented with malignant plasma cells. The objective of the present article was to report on the first case of an acquired VM associated with lambda light chain (LLC) myeloma.

Case presentation

Clinical presentation

A 52-year-old man with an unremarkable medical history was admitted to our nephrology department for acute kidney injury. With an infiltrated plasma cell count in the bone marrow of 38%, the patient met the morphological criteria for myeloma. He carried 1q and 17p deletions, both of which are associated with a poor prognosis. A serum protein analysis revealed hypogammaglobulinemia (4.9 g/L), an elevated LLC level (6630 mg/L), and a low kappa/lambda ratio (0.019).

The acute kidney injury was related to myeloma cast nephropathy (confirmed by a kidney biopsy) and required haemodialysis. A PET scan revealed bone lesions on the fifth lumbar vertebra and the pelvis, in the absence of hypercalcemia.

One week after admission, the patient complained about muscle weakness. A neurologic examination highlighted predominantly proximal motor impairments in all four limbs. The impairments were assessed on the Medical Research Council Manual Testing Scale. On day 10 (where day 0 corresponded to the day of hospital admission), the score was 3 out of 5 for the deltoid and iliopsoas on the right and 4 out of 5 for the deltoid and iliopsoas on the left (Table 1). There were no signs of brain damage, spinal cord damage, or cauda equina/conus medullary syndrome. The osteotendinous reflexes were normal in the upper limbs and attenuated in the lower limbs on day 10, completely absent in all limbs on day 15, and normal in all limbs on day 45. Mild rhabdomyolysis was noted on admission (serum creatine kinase level: 1517 IU/L; normal range: 46–171 IU/L) but had resolved by the time the patient first complained of muscle weakness.

Table 1.

Changes over time in limb and face muscle strength, as assessed on the Medical Research Council Manual Testing Scale

| D10 | D15 | D30 | D45 | D60 | D135 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upper limbs | ||||||||||||

| L | R | L | R | L | R | L | R | L | R | L | R | |

| Deltoid | 4/5 | 3/5 | 3/5 | 2/5 | 0/5 | 0/5 | 1/5 | 1/5 | 3/5 | 3/5 | 3/5 | 3/5 |

| Biceps | 4/5 | 4/5 | - | - | - | - | 3/5 | 3/5 | 3/5 | 3/5 | 4/5 | 4/5 |

| Triceps | 4/5 | 4/5 | - | - | - | - | 3/5 | 3/5 | 3/5 | 3/5 | 4/5 | 4/5 |

| Palm and finger extensors | - | - | 4/5 | 4/5 | - | - | 3/5 | 3/5 | 4/5 | 4/5 | 4/5 | 4/5 |

| Carpi and finger flexors | - | - | 5/5 | 5/5 | - | - | 3/5 | 3/5 | 4/5 | 4/5 | 4/5 | 4/5 |

| Lower limbs | ||||||||||||

| L | R | L | R | L | R | L | R | L | R | L | R | |

| Iliopsoas | 4/5 | 3/5 | 2/5 | 2/5 | 0/5 | 0/5 | 1/5 | 1/5 | 2/5 | 1/5 | 3/5 | 3/5 |

| Quadriceps | 4/5 | 3/5 | 2/5 | 2/5 | 1/5 | 1/5 | 1/5 | 1/5 | 3/5 | 2/5 | 4/5 | 4/5 |

| Hamstring | - | - | - | - | 1/5 | 2/5 | 2/5 | 2/5 | 3/5 | 2/5 | 4/5 | 4/5 |

| Tibialis anterior | - | - | 3/5 | 3/5 | 3/5 | 3/5 | 2/5 | 2/5 | 2/5 | 2/5 | 4/5 | 4/5 |

| Triceps surae | - | - | 4/5 | 4/5 | 3/5 | 3/5 | 3/5 | 3/5 | 2/5 | 2/5 | 4/5 | 4/5 |

| Facial | ||||||||||||

| No impairment | Severe diplegia | Moderate diplegia | Persistent mild left peripheral facial paralysis | Persistent mild left peripheral facial paralysis | Persistent mild left peripheral facial paralysis | |||||||

D0 corresponds to the day of hospital admission. Muscle strength was assessed on the Medical Research Council Manual Testing Scale from 0 (weakest) to 5 (strongest)

D day, L left, R right, “-” means that data were not available.

Electromyography

Electromyographic testing revealed spontaneous activity of the deltoid, trapezius, and biceps in the right upper limb. During voluntary contraction, the recordings were highly polyphasic; a dissociation between the level of effort and the spatial recruitment suggested that a myogenic syndrome was present. Similar observations were made for the iliopsoas, fascia lata and vastus medialis muscles on the right lower limb. The nerve conduction velocity was normal (Table 2).

Table 2.

Results of electromyographic tests of the right upper and lower limbs

| Nerve tested | Collection area (muscle) | Stimulation area | Latency (ms) | Amplitude (mV) | Segment | Latency difference (ms) | Distance (mm) | Conduction velocity (m/s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Motor conduction | ||||||||

| Median | Opposing thumb | Wrist | 4.2 | 4.6 | Wrist-Elbow | 5.5 | 280 | 51 |

| Elbow | 9.7 | 4.3 | ||||||

| Ulnar | Abductor of 5th finger | Wrist | 3.3 | 9.9 | Wrist-Elbow | 5.3 | 270 | 51 |

| Elbow | 8.6 | 9.5 | ||||||

| Fibular | Tibialis anterior | Fibular neck | 4.3 | 3.5 | Fibular neck-Popliteal Fossa | 1.5 | 85 | 57 |

| Popliteal fossa | 5.8 | 3.5 | ||||||

| Fibular | Extensor digitorum brevis | Ankle | 5.0 | 3.7 | Ankle-Fibular neck | 9.6 | 350 | 36 |

| Fibular neck | 14.6 | 3.2 | ||||||

| Tibial | Abductor hallucis | Ankle | 6.1 | 8.9 | - | - | - | - |

| Sensory conduction | ||||||||

| Median | 3rd finger | Palm | 1.9 | 0.015 | Palm-Wrist | 2.7 | 75 | 28 |

| Wrist | 4.6 | 0.019 | 3rd finger-Palm | 1.9 | 70 | 37 | ||

| Ulnar | 5th finger | Wrist | 2.6 | 0.021 | 5th finger-Wrist | 2.6 | 125 | 48 |

| Saphenous | External malleolus | Ankle | 2.0 | 0.050 | External malleolus-Ankle | 2.0 | 90 | 45 |

All electromyographic tests were performed on the right upper and lower limbs

Brain imaging and laboratory tests

The brain MRI results were normal. A lumbar puncture revealed clear cerebrospinal fluid, normal cell counts (1 nucleated cell/mm3, 2 red blood cells/mm3, and zero malignant cell/mm3), a slightly elevated protein level (0.86 g/L; normal range: 0.20–0.45 g/L), and normal glycorrhachia (3.6 mmol/L; normal range in cases of euglycemia: 2.3–4.1 mmol/L). No myositis-associated antibodies (Ro-52, OJ, EJ, PL-12, PL-7, SRP, Jo-1, PM-Scl75, PM-Scl100, Ku, SAE-1, NXP2, MDA5, TIF1gamma, Mi-2b, and Mi-2a) were detected.

Histopathologic assessment of a muscle biopsy

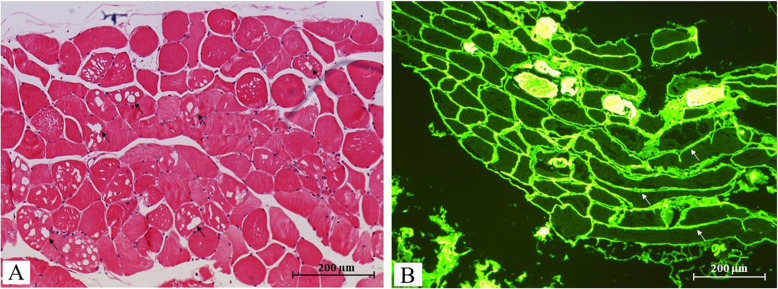

An analysis of a biopsy of the right deltoid muscle showed an irregular muscle fibre diameter, a few groups of atrophic fibres, focal necrosis, and macrophage resorption of fibres. Within the fibres, we observed small, visibly empty vacuoles in the absence of inflammation or fibrosis but with mild adipose infiltration (Fig. 1). Congo Red staining did not reveal any amyloid deposits, and periodic acid Schiff staining did not evidence glycogen overload. However, immunofluorescence revealed diffuse linear LLC deposits on the periphery of the muscle fibres and in the vessel wall.

Fig. 1.

Histopathology of a biopsy of the right deltoid muscle. The histopathologic assessment of the right deltoid muscle showed irregular, atrophic muscle fibres and small, apparently empty vacuoles under the light microscope (→) after hematein-eosin staining (magnification: × 10) (A). Immunofluorescence microscopy revealed diffuse, linear LLC deposits on the periphery of the muscle fibres (→) (magnification: × 10) (B)

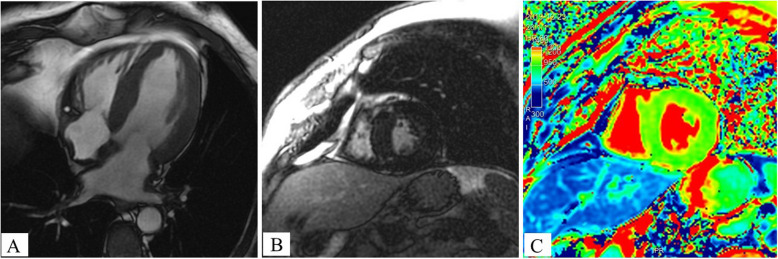

Cardiac assessment

Cardiac MRI showed concentric hypertrophy of the left ventricle (interventricular septum thickness: 16 mm) and both atria, and a preserved left ventricular ejection fraction (60%); these features were suggestive of infiltrative disease (Fig. 2). We also observed foci of left ventricular subepicardial fibrosis (in the inferolateral basal wall and interventricular septum at the right ventricle’s insertion points) but no evidence of amyloid deposits (i.e. normal myocardial native T1 values and no pericardial effusion, atrial enlargement, left ventricular or atrial subendocardial late gadolinium enhancement). The patient displayed repeated episodes of atrial arrythmia, which decreased in frequency upon treatment of the myeloma.

Fig. 2.

Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. A Cine-MRI with a four-chamber view: hypertrophy of the left ventricle and both atria. B Late gadolinium enhancement with a short-axis view: note the presence of foci of subepicardial fibrosis at the interventricular septum (at right ventricle insertion points). C Native T1 mapping: the normal T1 values in the thickened left ventricular myocardium were not suggestive of cardiac amyloidosis

Treatment and outcomes

The motor impairment worsened for five days, with the appearance of facial diplegia and impaired palpebral occlusion on day 15. Treatment with a combination of bortezomib, lenalidomide and dexamethasone was initiated on day four and led to a good hematologic response. After four months of treatment, the patient had recovered well (first in the face and then in the limbs, see Table 1). After six months of treatment, muscle strength scores were near-normal. Thirty-four months later, the patient developed plasma cell leukaemia and (despite intensive salvage therapy) died after two months. The myopathy did not reappear during the course of the leukaemia, although the serum LLC level rose to 4280 mg/L (kappa/lambda ratio: 0.0009).

Discussion

Here, we reported on the first case of VM associated with LLC myeloma. The patient presented with episodes of supraventricular arrhythmia and concomitant, severe, proximal motor impairments and diplegia. Electromyographic testing showed a myogenic pattern, and a muscle biopsy highlighted muscle fibre vacuoles with LLC deposits. Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging revealed concentric hypertrophy and subepicardial areas of fibrosis that were suggestive of an infiltrative disease.

Treatment with a combination of bortezomib, lenalidomide and dexamethasone gave a good hematologic response, and the patient recovered near-normal levels of muscle strength in the following six months. The number of episodes of arrythmia decreased.

A corticosteroid-sparing strategy for vacuolar myopathy does not appear to be necessary when the course of the myeloma is favourable. Treatment with corticosteroids, immunosuppressive agents or intravenous immunoglobulins could be considered when muscle manifestations are severe. Clinicians should pay more attention to mild muscle impairments in patients with myeloma or monoclonal gammopathy. Electromyography and muscle biopsy results can guide the diagnosis.

In the context of gammopathy without malignant cells: vacuolar myopathy

Three cases of acquired VM associated with monoclonal gammopathy were described by Allenbach et al. in 2019 [4]. All three of Allenbach et al.’s patients had predominantly proximal muscle impairments and IgG kappa gammopathy but not plasma cell malignancy. Our patient had a similar motor impairment but also showed myeloma-associated LLC gammopathy. Hence, we speculate that the vacuoles contained LLCs. Unfortunately, we could not confirm this by electron microscopy because a glutaraldehyde-fixed sample was not available. In 2023, Soontrapa et al. reported on a case of acquired VM with biclonal gammopathy in a context of polyneuropathy, organomegaly, endocrinopathy, M protein, skin changes (POEMS) syndrome [5]. The 51-year-old woman presented weight loss with severe distal and mild proximal weakness and length-dependent sensory impairments. In contrast, our patient did not display severe distal motor impairments or features of POEMS syndrome.

The patients with VM described by Allenbach et al. and Soontrapa et al. presented with gammopathy; however, to the best of our knowledge, a case of acquired VM associated with myeloma has not previously been reported. All the patients improved clinically and recovered normal levels of muscle strength after the initiation of treatment with immunosuppressive agents. The creatine kinase level rose in few cases only (Table 3).

Table 3.

Case reports on non-amyloid, non-nemaline myopathies associated with gammopathy and/or malignant plasma cells

| Reference | Gammopathy or myeloma | Clinical findings | Creatine kinase | Electromyography | Histopathology | Therapy/outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-vacuolar myopathy | ||||||

| Fernandez-Sola et al., 1987 [6] | KLC myeloma | 44, M, asymptomatic | Elevated | / |

Kappa LCDD LM: unremarkable IF: KLC deposits |

/ |

| Farah et al., 2005 [7] | KLC myeloma | 70, F, asymptomatic | Elevated | / |

Kappa LCDD LM: unremarkable IF: KLC deposits |

/ |

| Belkhribchia et al., 2020 [8] | LLC myeloma | 48, F, progressive proximal weakness, distal dysaesthesia, HCM, LVEF = 21% | Normal | A myogenic pattern in the proximal muscles + bilateral peripheral neuropathy |

Lambda LCDD LM: unremarkable IF: LLC deposits |

Not reported/CYC + BTZ + CS |

| Vacuolar myopathy | ||||||

| Allenbach et al., 2019 [4] | MGUS IgG kappa | 3 patients aged from 38 to 56, sex not reported, proximal weakness | Elevated | A myogenic pattern in the proximal muscles |

LM: Glycogen-positive vacuoles IF: not reported |

Favourable (in 2 of the 3 patients)/ISs + CS + Ig |

| Soontrapa et al., 2023 [5] | 2 MGUS (IgG kappa + Ig A lambda) | 51, F, severe distal and slight proximal weakness | Normal | Polyradiculoneuropathy and a myogenic pattern in the proximal muscles |

LM: Glycogen-positive vacuoles IF: not reported |

Favourable/autologous stem cell transplantation |

| The present report | LLC myeloma | 52, M, proximal weakness, facial diplegia, HCM, LVEF 60% | Normal (before the onset of muscle weakness) | A myogenic pattern in the proximal muscles |

LM: Glycogen-negative vacuoles IF: LLC deposits |

Favourable/BTZ + LN + CS |

KLC kappa light chain, M male, LCDD light chain deposition disease, LM light microscopy, IF immunofluorescence, F female, LLC lambda light chain, HCM hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, LVEF left ventricular ejection fraction, CYC cyclophosphamide, BTZ bortezomib, CS corticosteroid, MGUS monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance, IS immunosuppressant, Ig immunoglobulin, LN lenalidomide

In the context of myeloma: neuromuscular disorders (except for vacuolar myopathy)

In the context of myeloma, neuromuscular disorders mainly affect the peripheral nervous system and are related to plasma cell dyscrasia or drug toxicity [9]. Although myeloma associated-myopathies have been observed, they are rare and mainly encompass LLC amyloid myopathy and non-amyloid myopathies (including sporadic onset late nemaline myopathy (SLONM)) [10]. It is noteworthy, that cells from patients with SLONM may contain some vacuoles but (in contrast to VM) are always characterized by the presence of nemaline rods.

Lastly, non-amyloid non-nemaline myopathies associated with myeloma (or monoclonal gammopathy) that affect the muscles have not been extensively characterized (Table 3). Two cases of kappa light-chain deposition disease (LCDD) in the muscles (in the absence of VM) have been described in a context of myeloma and monoclonal gammopathy of renal significance [6, 7, 11].

Belkhribchia et al. reported on the original case of lambda LCDD related to LLC myeloma [8]. The clinical findings included proximal limb muscle weakness, with a myogenic electromyographic pattern. Although the muscle biopsy was normal when viewed with light microscopy, further investigations using immunofluorescence microscopy revealed LLC deposits in the endomysium, perimysium, and vascular walls. Cardiac MRI highlighted an abnormally thick myocardium in the left ventricle and a very low left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), which suggested the presence of an infiltrating myocardial disease. However, the case described by Belkhribchia et al. differs from the present case in several important respects: (i) the absence of fibre vacuoles, (ii) the presence of neuropathy, (iii) the less sudden worsening in clinical signs, and (iv) the very low LVEF.

Given that our patient presented with features of cardiac infiltrative disease but had no signs of amyloidosis on MRI, we hypothesize that the myocardial infiltration was related to LLC deposits. Although LCDD rarely targets organs other than the kidney, cardiac involvement has been reported [12, 13].

Monoclonal gammopathy of clinical significance

Monoclonal gammopathy of clinical significance (MGCS) corresponds to an emerging, broad spectrum of disorders affecting a variety of organs [14]. The deposits are classified according to their organization and nature [15]. We note that amyloid and nemaline myopathies associated with monoclonal gammopathy have been reported frequently [16, 17]. Although the American Society of Hematology’s guidelines mention the particular case of SLONM-MGCS, they do not list VM associated with monoclonal gammopathy. However, Yu et al. suggested that MGCS-associated myopathy should be considered as a clinical entity [16]. We believe that MGCS-associated myopathy might be a new element in the broad “monoclonal gammopathy of determined significance” spectrum. In cases of vacuolar myopathy associated with monoclonal gammopathy, severe muscle impairments may require treatment. In two of the three cases described by Allenbach et al., various treatments (including corticosteroids, immunosuppressive agents, and intravenous immunoglobulins) led to an increase in muscle strength [4].

The mechanism of MGCS is complex and includes the direct toxicity of immunoglobulins and the indirect toxicity of factors related to the clone (e.g. mediators, auto-antibodies, and changes in the complement pathway). With regard to lambda LCDD in muscles, we hypothesize that LLC is toxic for muscle cells but we cannot rule out the involvement of other clone-related causative factors. It is noteworthy that our patient had normal complement C3 and C4 levels and no obvious autoimmune factors. Interestingly, the VM did not reappear when the myeloma relapsed. However, given the well-known genomic instability observed during myeloma progression, one cannot rule out downregulation of the clone associated with the myopathy (if there was one) [18].

Acknowledgements

We thank David Fraser PhD (Biotech Communication SARL, Ploudalmézeau, 238 France) for editorial advice and copy-editing assistance.

Authors’ contributions

Q.B. wrote the manuscript. All authors revised the manuscript. C.R provided and interpreted cardiac magnetic resonance images. N.G provided and interpreted histopathology image sections. P-E.M performed electromyographic testing and interpreted the results.

Funding

This work was not supported by any specific funding from agencies or organizations in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study. The authors declare that data supporting the findings of this case report study are available within the article.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

In line with the French legislation on non-interventional studies of routine clinical practice, the study protocol was approved by a hospital committee (Amiens University Hospital, Amiens, France) with competency for research not requiring authorization by an institutional review board (reference: PI2023_843_0180).

Consent for publication

Given that the patient died, his wife provided written informed consent for the publication of this case report.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Mair D, Biskup S, Kress W, et al. Differential diagnosis of vacuolar myopathies in the NGS era. Brain Pathol. 2020:bpa.12864. 10.1111/bpa.12864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Khosa S, Khanlou N, Khosa GS, Mishra SK. Hydroxychloroquine-induced autophagic vacuolar myopathy with mitochondrial abnormalities. Neuropathology. 2018;38(6):646–52. 10.1111/neup.12520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fernadez C, Figarella-Branger D, Alla P, Harle JR, Pellissier JF. Colchicine myopathy: a vacuolar myopathy with selective type I muscle fiber involvement. Acta Neuropathol. 2002;103(2):100–6. 10.1007/s004010100434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Allenbach Y, Salort-Campana E, Malfatti E, et al. P.09Vacuolar myopathy with monoclonal gammopathy and stiffness (VAMGS). Neuromuscul Disord. 2019;29:S44. 10.1016/j.nmd.2019.06.038. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Soontrapa P, Tracy JA, Gonsalves WI, Liewluck T. Treatment-responsive glycogen storage myopathy in a patient with POEMS syndrome: a new monoclonal gammopathy-associated myopathy. Eur J Neurol. 2023. 10.1111/ene.16008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fernández-Solá J, Cases A, Monforte R, et al. A possible pathogenic mechanism for rhabdomyolysis associated with multiple myeloma. Acta Haematol. 1987;77(4):231–3. 10.1159/000206001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Farah R, Farah R, Kolin M, Cohen H, Kristal B. Light chain muscle deposition caused rhabdomyolysis and acute renal failure in patient with multiple myeloma. CN. 2005;63(01):50–3. 10.5414/CNP63050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Belkhribchia MR, Moukhlis S, Bentaoune T, Chourkani N, Zaidani M, Karkouri M. Skeletal myopathy as the initial manifestation of light chain multiple myeloma. Eur J Case Rep Intern Med. 2020;(LATEST ONLINE):1. 10.12890/2020_002095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Mohty B, El-Cheikh J, Yakoub-Agha I, Moreau P, Harousseau JL, Mohty M. Peripheral neuropathy and new treatments for multiple myeloma: background and practical recommendations. Haematologica. 2010;95(2):311–9. 10.3324/haematol.2009.012674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Uruha A, Benveniste O. Sporadic late-onset nemaline myopathy with monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance. Curr Opin Neurol. 2017;30(5):457–63. 10.1097/WCO.0000000000000477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gudapati P, Al- Sultani A, Parmar A, Motwani R, Fortkort P. Rhabdomyolysis and acute renal dysfunction as initial manifestations of monoclonal gammopathy of renal significance. Cureus. 2023. 10.7759/cureus.34759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nishioka R, Yoshida S, Takamatsu H, Kawano M. Cardiac light-chain deposition disease and hints at diagnosing: a case report. Eur Heart J Case Rep. 2023;7(2): ytad049. 10.1093/ehjcr/ytad049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Joly F, Cohen C, Javaugue V, et al. Randall-type monoclonal immunoglobulin deposition disease: novel insights from a nationwide cohort study. Blood. 2019;133(6):576–87. 10.1182/blood-2018-09-872028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dispenzieri A. Monoclonal gammopathies of clinical significance. Hematology. 2020;2020(1):380–8. 10.1182/hematology.2020000122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fermand JP, Bridoux F, Dispenzieri A, et al. Monoclonal gammopathy of clinical significance: a novel concept with therapeutic implications. Blood. 2018;132(14):1478–85. 10.1182/blood-2018-04-839480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yu H, He D, Zhang Q, Cao B, Liu W, Wu Y. Case report: monoclonal gammopathies of clinical significance-associated myopathy: a case-based review. Front Oncol. 2022;12:914379. 10.3389/fonc.2022.914379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Okhovat AA, Nilipour Y, Boostani R, et al. Sporadic late-onset nemaline myopathy with monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance: report of four patients. Neuromuscul Disord. 2021;31(1):29–34. 10.1016/j.nmd.2020.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aksenova AY, Zhuk AS, Lada AG, et al. Genome instability in multiple myeloma: facts and factors. Cancers. 2021;13(23):5949. 10.3390/cancers13235949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study. The authors declare that data supporting the findings of this case report study are available within the article.