Abstract

For detection of viral RNA in blood or tissue, samples are often collected into lysis buffers prior to downstream molecular analysis. Immediate sample processing and cold storage are not always possible during large-scale or field studies, or in facilities lacking a stable electrical supply. Additionally, samples may need to be transported significant distances before processing. Here, using Peptidylprolyl Isomerase A (Ppia), a stably expressed gene in rodent tissues, we investigate the long-term stability and detection of RNA in guinea pig tissues stored for up to 52 weeks and in hamster blood stored for up to 12 weeks in MagMAX Lysis/Binding Solution Concentrate at −80°C, 4°C, 21°C, and 32°C.

Keywords: RNA stability, lysis buffer, storage, temperature

Report

Under ideal conditions, it is recommended to store samples for RNA analysis either frozen (flash freezing in liquid nitrogen) or in preservation solutions such as RNAlater to maintain sample integrity and prevent degradation [1]. Although cryopreservation remains the gold standard, the use of liquid nitrogen may be impractical or unavailable in certain contexts, such as fieldwork studies or resource-limited settings. RNAlater has been proposed as an alternative, enabling room temperature storage for several days without substantial loss in RNA quality [2], which may be advantageous when collecting tissue samples under non-ideal conditions [3]. However, when handling potentially infectious material, the use of RNAlater may pose a biohazard risk, as studies have demonstrated its capacity to preserve viral infectivity [4–6].

High-consequence viral hemorrhagic fevers (VHFs) are caused by negative-sense RNA viruses that include nairoviruses, arenaviruses, filoviruses, and henipaviruses. Processing and molecular analyses of samples that are known or suspected to contain these viruses for outbreak response, ecological field studies, or research require handling under strict biocontainment and inactivation via validated methods before work can be performed at lower containment [7]. Particularly during outbreak response, these samples may be collected under resource-limited settings, inadequate cold-chain storage and face logistical difficulties in transportation to facilities for analysis. To reduce infection risk and maintain sample quality, it is ideal for samples to be immediately collected into a known inactivant that can also stabilize RNA until samples can be processed by, for example, nucleic acid extraction and subsequent reverse transcription quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR), which can confirm viral presence and determine viral loads (e.g., in pathogenesis and medical countermeasure studies) through the detection of short, specific sections of the viral genome [8–10].

MagMAX Lysis/Binding Solution Concentrate (Cat. No. Invitrogen, AM8500) has been demonstrated to be an effective inactivant for many RNA viruses [11–13]. This lysis buffer contains 55–80% guanidinium thiocyanate (GITC; CAS: 593–84-0), a chaotropic agent that protects RNA from degradation by denaturing RNases [14], and is frequently used for the inactivation of virus in tissue and blood samples for downstream RT-qPCR analysis in research, diagnostics, and ecological investigations [8,15–21]. Here, we evaluated the detection of RNA in rodent tissue stored in MagMAX Lysis/Binding Solution Concentrate at various temperatures and for different lengths of time. We aimed to mimic scenarios that may occur during field studies, outbreaks, or cold-storage failures that could result in delayed processing (i.e., RNA extraction) or suboptimal handing after sample collection, and to determine suitability for medium or long-term storage under these conditions. To perform these studies, we selected Ppia as the gene target due to its high conservation across mammals, its stable expression in both naïve and infected rodent tissue [22]; and because the assay targets a short amplicon (126 base pairs) aligning with best practices for RT-qPCR assays which recommend amplicon sizes of 75–150 base pairs [23].

To assess stability of tissue RNA in samples stored in MagMAX Lysis/Binding Solution Concentrate, liver, gonad, kidney, heart, lung, eye, and brain tissues were collected post-mortem from naïve adult strain 13/N guinea pigs (n = 9; 5 males, 4 females; 879–1345 days old) from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in-house colony that were euthanized for humane reasons (e.g., age, injury, or underlying conditions) by isoflurane inhalation followed by intracardiac administration of sodium pentobarbital. Tissue was maintained on ice, homogenized in MagMAX Lysis/Binding Solution Concentrate using 4 mL polycarbonate grinding vial containing pre-cleaned 3/8” 440C stainless steel grinding balls (OPS Diagnostics, Cat. No. PCVS 04–240-03) and stored at either −80°C, 4°C, 21°C, or 32°C for up to one year prior to RNA extraction and RT-qPCR analyses. To ensure sufficient material for all sampling points, whole organs were collected. Organs too large for a single grinding vial were divided and homogenized separately to ensure complete homogenization. Homogenization was performed using the 2000 Geno/Grinder (SPEX SamplePrep) using 1500 strokes/minute for 2 minutes. All tissue samples were brought to a final volume of 10 mL with MagMAX Lysis/Binding Solution Concentrate and centrifuged at 100 × g for 5 minutes to remove any particulate debris. Samples were pre-aliquoted into 300 μL volumes before storage. Post-homogenization sample processing took approximately 4 hours and was conducted at room temperature. To mimic potential storage conditions, homogenates were placed in cold storage (−80°C or 4°C), controlled room temperature (21°C [19.5–22.5°C]), or hot storage (32°C [28–32°C]) to mimic warmer equatorial conditions during field studies or outbreaks.

RNA was extracted using the MagMAX™ Pathogen RNA/DNA Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cat. No. 4462359) in a 96-well KingFisher Apex purification system (Thermo Fisher Scientific) from 250 μL tissue homogenate after 0, 1, 2, 4, 8, 12, 36, or 52 weeks of storage. Immediately prior to extraction, 150 μL isopropanol was added to sample homogenate. Eluates were treated with Baseline-zero DNase (Lucigen, Cat. No. DB0715K), eluted in 75 μL MagMAX elution buffer, and stored at −80°C. RNA extracted from week 0 samples were assessed using the Nanodrop 1000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for yield and purity (A260/A280). RNA extracted from one heart sample was found to be of insufficient yield and purity at week 0 and was discarded from further analysis.

RT-qPCR set-up was performed using the OT-2 liquid handling system (Opentrons). PCRs were run on the CFX384 Real-Time PCR Detection systems (BioRad) with 10 μL reaction volume containing 2.5 μL template RNA for RT-qPCR using the SuperScript III Platinum One-Step qRT-PCR kit (ThermoFisher Scientific, Cat. No. 11732088). Each RT-qPCR reaction was performed in duplicate. Thermal cycling conditions were as follows: 50°C reverse transcription step for 15 min, 95°C denaturation for 2 min, and 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 30 s. RNA assessed using the reference gene, Peptidylprolyl Isomerase A (Ppia) [Accession #XM_003465805 (guinea pig) and XM_005086775 (hamster)], which is stably expressed in rodent models of VHFs [22]. Primers were based on the pan-species Ppia assay described previously, with probe sequence shifted to remove an indicated hairpin site identified in the previously described sequence. This assay spans multiple exons (based on Mus musculus [NM_008907], exon boundaries are not defined for guinea pig or hamster sequences) and targets the majority of splice variants (8/11) [24]. Primers were generated by Integrated DNA Technologies, and primer sequences (5ʹ–3ʹ) were as follows: forward (400 μM; exon 1), CCC ACC GTG TTC TTC GAC; reverse (400 μM, exon 3), TCC TTT CTC TCC AGT GCT CAG; and probe (200 μM, exon 1), HEX – CCT TGG GCC – ZEN – GCG TCT CCT TCG A – IABkFQ. Data was analyzed in Bio-Rad CFX Manager 3.1 and GraphPad Prism v10. Changes in Ct values over time were calculated for each storage condition relative to Ct values on week 0. Ct values greater than 35 were considered negative. Ordinary one-way ANOVA with Tukey multiple comparisons test was conducted using Ct values to evaluate statistical differences between samples stored at −80°C, 4°C, 21°C, or 32°C (Table S1).

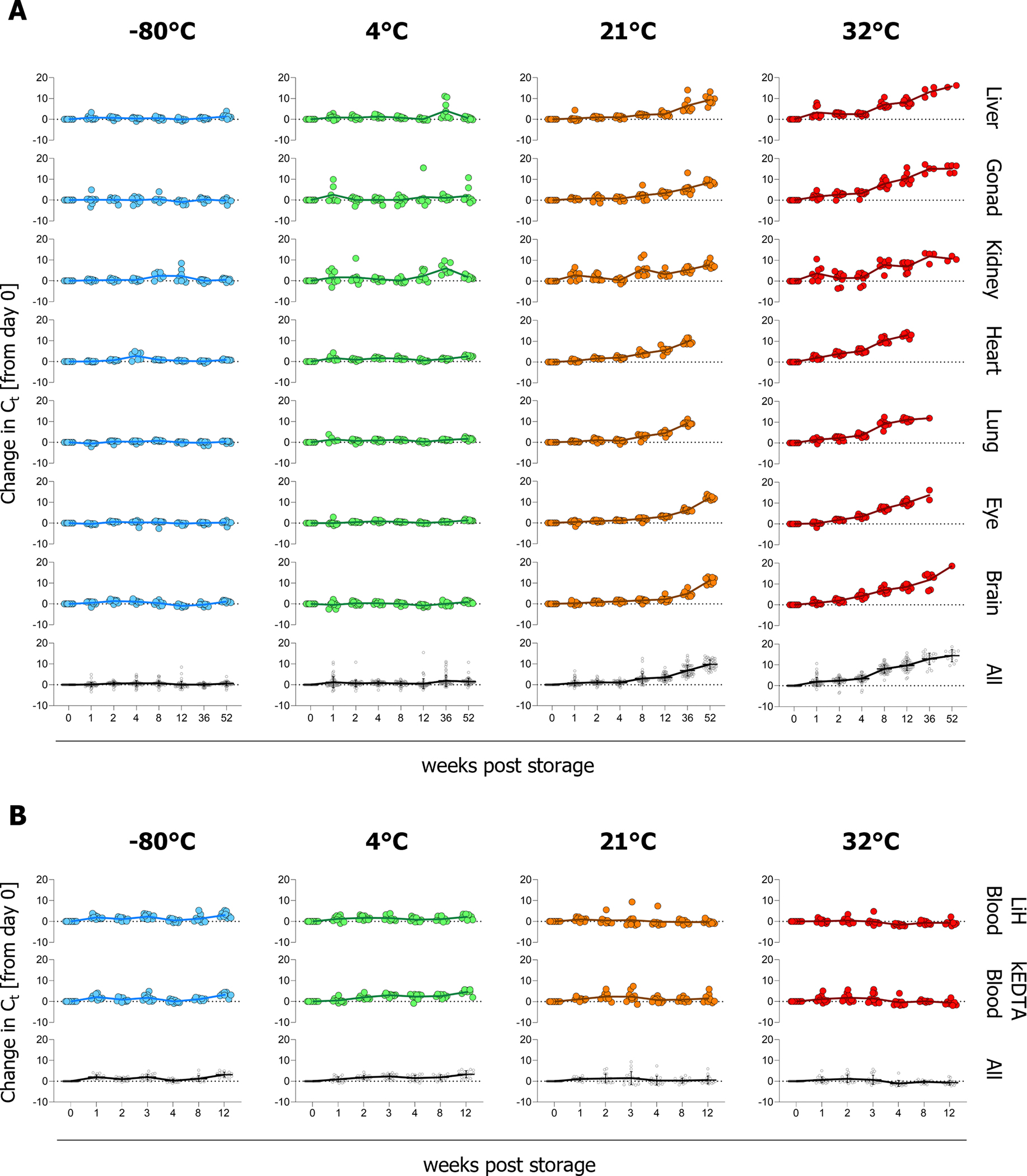

We found that cold storage (−80°C and 4°C) was optimal, with minimal change (i.e., <3.3 Ct) to tissue RNA Ct values up to 52 weeks post-sample collection. This is supported by previous studies, which showed that storing synthetic and cellular RNA in GITC-containing buffers at −20°C, −80°C, and in liquid nitrogen for up to 18 months did not appreciably reduce RNA stability [25]. Storage at room temperature (21°C) for up to 12 weeks, and at 32°C for up to 4 weeks, demonstrated on average no significant change in Ct value (i.e., < 6.6 Ct or ~100-fold loss) (Figure 1A, Table S2), indicating utility of these conditions up to these time points. However, extended storage at high temperatures indicated degradation of tissue RNA, with approximately a 100–1000-fold (6.6 – 9.9 Ct increase) loss on average by 36 weeks at 21°C and 8 weeks at 32°C. High-temperature storage (32°C) was particularly detrimental for RNA detection, with only liver (2/9), gonad (5/9), kidney (3/9), and brain (1/9) returning quantifiable values (<35 Ct) at 52 weeks. Heart and lung RNA samples were particularly sensitive; little to no RNA could be detected by RT-qPCR at 36 weeks of storage at 32°C or 52 weeks at 21°C. Significance differences were observed between samples stored at cold temperatures (−80°C and 4°C) and 32°C from as early as 1 week for lung, and 2 weeks for heart (Table S1).

Figure 1. Tissue RNA can be detected in tissue and blood samples after long-term storage in MagMAX Lysis/Binding Solution Concentrate at −80°C, 4°C, 21°C, and 32°C.

(A) Tissues (liver [n=9], gonad [testes (n=5) or ovary (n=4)], kidney [n=9], heart [n=8], lung [n=9], eye [n=9], and brain [n=9]) harvested from 9 individual naïve guinea pigs were homogenized into undiluted MagMAX Lysis/Binding Solution Concentrate and stored at −80°C, 4°C, 21°C, or 32°C for indicated periods (B) Whole blood from 10 naïve Syrian hamsters was collected into vacutainers containing lithium heparin (LiH) or potassium EDTA (KEDTA). Blood was added to MagMAX Lysis/Binding Solution Concentrate before storing at −80°C, 4°C, 21°C, or 32°C For both tissues (A) and blood (B) RNA was extracted using the MagMAX™ Pathogen RNA/DNA Kit in a 96-well KingFisher Apex purification system at the indicated time points and quantified by RT-qPCR using primers specific for the reference gene Peptidylprolyl isomerase A. To determine changes in RNA levels, differences in Ct values relative to week 0 were calculated and graphed using GraphPad Prism v10. Individual animals are represented by circles, where sample-type means are indicated by the solid line. Tissue samples were assessed at all indicated timepoints, data points depicted without values indicate instances where RNA was not detectable. Due to limited terminal blood sample volume, fewer blood samples were analyzed at later time points (LiH blood: n = 10 at ≤ week 4, n = 9 at weeks 8 and 12; KEDTA blood: n = 10 at ≤ week 3, n = 9 at week 4, n= 8 at weeks 8 and 12). Graphs are presented by individual tissue type or blood specimen type or with all data for the corresponding time and temperature combined (All), with error bars representing the standard error of the mean.

To assess stability of blood RNA in samples stored in MagMAX Lysis/Binding Solution Concentrate, terminal whole blood samples from naïve Syrian hamsters (n = 10; 5 males and 5 females; 133 days old) were collected in either lithium heparin (LiH) or potassium EDTA (KEDTA) before adding 1 volume blood to 4 volumes undiluted in MagMAX Lysis/Binding Solution Concentrate. Samples were pre-aliquoted into 300 μL volumes before storage as previously described for tissues: cold storage (−80°C or 4°C), room temperature (21°C [19.5–22.5°C]), or hot storage (32°C [28–32°C]). RNA was extracted as previously described for tissue from 250 μL whole blood lysate after 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 8, or 12 weeks of storage and analyzed by RT-qPCR. The detection of Ppia in blood samples was more stable than in tissues; irrespective of anti-coagulant used for collection, detection levels remained consistent up to 12 weeks post-storage, even at 32°C (Figure 1B). These differences may be linked to compositional differences between matrices. Metal ions such as magnesium, zinc, iron, and lead have been shown to increase RNA hydrolysis [26,27]. Blood has lower metal ion concentrations than tissue [28], and chelators used in blood collection (e.g., KEDTA and LiH) can bind metal ions, potentially conferring further protection to RNA from hydrolysis [26,29]. Certain tissues (liver and kidney) may also contain higher levels of natural chelators such as glutathione, metallothionein and citrate providing additional protection, which could address differences observed between tissue types [30–32]. In addition, the high lipid content of tissues may interfere with the chemistry of lysis reagents by altering the pH which could accelerate RNA decay [33].

We determined that a short amplicon can be detected across all storage conditions in tissue for up to a year under cold storage, whereas room temperature or higher led to increased Ct values and decreased ability to detect RNA targets after 4 weeks of storage. RNA detection was not affected by temperature and remained stable in blood samples stored up to 12 weeks under all four conditions tested. These findings are based on detection of an amplicon size of 126 bp to mimic the conditions used for molecular detection of pathogens by RT-qPCR. Although no infectious agents were used in these studies, ratios of MagMAX Lysis/Binding Solution Concentrate to sample used herein adhered to or exceeded our current validated procedures for virus inactivation (≥ 1:10 for tissue and ≥ 1:4 for blood) to ensure these data are applicable to infectious virus studies.

While these data support detection of short amplicons, future studies would be warranted to assess RNA quality, data necessary for analyses like next-generation sequencing (NGS) that require high-quality, intact RNAs to provide high-resolution transcriptomics [34], as previous studies have indicated that tissue RNAs extracted via the MagMAX kit may not be suitable for NGS/RNA sequencing studies [35]. Furthermore, our data focuses on a cellular target (not a viral target) and is derived from naïve tissue. We previously reported that Ppia was stably expressed in both naïve and infected rodents [22], other gene targets may not exhibit stable expression in rodents. Within living cells, various mechanisms exist to degrade both cellular and viral RNAs, such as nuclease mediated degradation. However, in our study, samples were processed and stored in a guanidinium thiocyanate-based lysis buffer, a strong protein denaturant; thus, enzyme-mediated RNA degradation is unlikely to have played a significant role. Instead, the observed RNA decay is more likely due to instability in chemical structure (e.g., hydrolysis), which is known to be accelerated at increased temperatures [36]. Here, we focus on single stranded messenger RNA; however, RNA stability in viral targets may also vary depending on RNA composition (e.g., double-stranded vs. single-stranded RNA viruses, or segmented vs. non-segmented RNA viruses). Future studies would benefit from including a broader range of targets representing diverse RNA compositions and structures. Finally, we aimed to mimic sub-optimal conditions that might be encountered in low-resource conditions; other factors not assessed herein that could negatively impact RNA stability include temperature fluctuations (e.g., cold-storage failure, day-night cycle), exposure to temperatures >32°C, light exposure, and unregulated humidity levels.

Overall, this report provides data relevant to both laboratory and field studies, supporting the use of cold temperatures (−80°C and 4°C) for long-term storage of rodent tissue samples collected in MagMAX Lysis/Binding Solution Concentrate. Additionally, our findings indicate that under sub-optimal circumstances when cold storage is not feasible, blood and most tissue types – excluding lung and heart, which show earlier levels of degradation – can be stored in MagMAX Lysis/Binding Solution Concentrate at room temperature for up to 12 weeks, and at temperatures up to 32°C for 4 weeks, prior to RNA extraction and RT-qPCR analysis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We thank Tatyana Klimova for assistance with editing the manuscript.

Funding.

This work was supported in part by CDC Emerging Infectious Disease Research Core funds and by an appointment to the CDC administered by the Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education (ORISE) through an interagency agreement between the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) and USDA-ARS (K.A.D.). ORISE is managed by Oak Ridge Associated Universities (ORAU) under contract with DOE.

Footnotes

Potential Conflicts of Interest. All authors: no reported conflicts

Ethics statement. All animal studies were approved by the CDC Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, performed in an AAALAC International-approved facility, and conducted in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. The CDC is fully accredited by the AAALAC International.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process. During the preparation of this work the author(s) used ChatGPT and Grammarly selectively to improve grammar and syntax. After using this tool/service, the author(s) reviewed and edited the content as needed and take(s) full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Disclaimer. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Data availability.

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- [1].Riesgo A, Pérez-Porro AR, Carmona S, Leys SP, Giribet G, Optimization of preservation and storage time of sponge tissues to obtain quality mRNA for next-generation sequencing, Mol Ecol Resour 12 (2012) 312–322. 10.1111/j.1755-0998.2011.03097.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Camacho-Sanchez M, Burraco P, Gomez-Mestre I, Leonard JA, Preservation of RNA and DNA from mammal samples under field conditions, Mol Ecol Resour 13 (2013) 663–673. 10.1111/1755-0998.12108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Wille M, Yin H, Lundkvist Å, Xu J, Muradrasoli S, Järhult JD, RNAlater ® is a viable storage option for avian influenza sampling in logistically challenging conditions, J Virol Methods 252 (2018) 32–36. 10.1016/j.jviromet.2017.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Kurth A, Possible biohazard risk from infectious tissue and culture cells preserved with RNAlater™, Clin Chem 53 (2007) 1389–1390. 10.1373/clinchem.2007.085894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Pham PH, Sokeechand BSH, Garver KA, Jones G, Lumsden JS, Bols NC, Fish viruses stored in RNAlater can remain infectious and even be temporarily protected from inactivation by heat or by tissue homogenates, J Virol Methods 253 (2018) 31–37. 10.1016/j.jviromet.2017.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Uhlenhaut C, Kracht M, Viral infectivity is maintained by an RNA protection buffer, J Virol Methods 128 (2005) 189–191. 10.1016/j.jviromet.2005.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Guidance on the Inactivation or Removal of Select Agents and Toxins for Future Use, (n.d.) https://www.selectagents.gov/compliance/guidance/inactivation/index.htm (accessed October 14, 2024).

- [8].Towner JS, Sealy TK, Ksiazek TG, Nichol ST, High-throughput molecular detection of hemorrhagic fever virus threats with applications for outbreak settings, in: Journal of Infectious Diseases, J Infect Dis, 2007. 10.1086/520601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Loayza Mafayle R, Morales-Betoulle ME, Romero C, Cossaboom CM, Whitmer S, Alvarez Aguilera CE, Avila Ardaya C, Cruz Zambrana M, Dávalos Anajia A, Mendoza Loayza N, Montaño A-M, Morales Alvis FL, Revollo Guzmán J, Sasías Martínez S, Alarcón De La Vega G, Medina Ramírez A, Molina Gutiérrez JT, Cornejo Pinto AJ, Salas Bacci R, Brignone J, Garcia J, Añez A, Mendez-Rico J, Luz K, Segales A, Torrez Cruz KM, Valdivia-Cayoja A, Amman BR, Choi MJ, Erickson B-R, Goldsmith C, Graziano JC, Joyce A, Klena JD, Leach A, Malenfant JH, Nichol ST, Patel K, Sealy T, Shoemaker T, Spiropoulou CF, Todres A, Towner JS, Montgomery JM, Chapare Hemorrhagic Fever and Virus Detection in Rodents in Bolivia in 2019, N Engl J Med 386 (2022) 2283–2294. 10.1056/NEJMOA2110339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Racsa LD, Kraft CS, Olinger GG, Hensley LE, Viral Hemorrhagic Fever Diagnostics, Clin Infect Dis 62 (2016) 214. 10.1093/CID/CIV792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Alger K, Ip H, Hall J, Nashold S, Richgels K, Smith C, Inactivation of Viable Surrogates for the Select Agents Virulent Newcastle Disease Virus and Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza Virus Using Either Commercial Lysis Buffer or Heat, Applied Biosafety 24 (2019) 189–199. 10.1177/1535676019888920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Ngo KA, Jones SA, Church TM, Fuschino ME, St. George K, Lamson DM, Maffei J, Kramer LD, Ciota AT, Unreliable inactivation of viruses by commonly used lysis buffers, Applied Biosafety 22 (2017) 56–59. 10.1177/1535676017703383. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Honeywood MJ, Jeffries-Miles S, Wong K, Harrington C, Burns CC, Oberste MS, Bowen MD, Vega E, Use of guanidine thiocyanate-based nucleic acid extraction buffers to inactivate poliovirus in potentially infectious materials, J Virol Methods 297 (2021) 114262. 10.1016/j.jviromet.2021.114262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].McGookin R, RNA Extraction by the Guanidine Thiocyanate Procedure, in: Nucleic Acids, Methods Mol Biol, 2003: pp. 113–116. 10.1385/0-89603-064-4:113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Pallister J, Middleton D, Wang LF, Klein R, Haining J, Robinson R, Yamada M, White J, Payne J, Feng YR, Chan YP, Broder CC, A recombinant Hendra virus G glycoprotein-based subunit vaccine protects ferrets from lethal Hendra virus challenge, Vaccine 29 (2011) 5623–5630. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Liu Y, Sun YL, Wu W, Aq.Q Li, Da Yang X, Zhang S, Li C, Su QD, Cai SJ, Sun DP, Hu HY, Zhang Z, Yang XX, Kamara I, Koroma S, Bangura G, Tia A, Kamara A, Lebby M, Kargbo B, Li J, Wang S, Dong XP, Shu YL, Xu WB, Gao GF, Wu GZ, Li DX, Liu WJ, Liang MF, Serological Investigation of Laboratory-Confirmed and Suspected Ebola Virus Disease Patients During the Late Phase of the Ebola Outbreak in Sierra Leone, Virol Sin 33 (2018) 323–334. 10.1007/s12250-018-0044-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Paweska JT, Jansen van Vuren P, Meier GH, le Roux C, Conteh OS, Kemp A, Fourie C, Naidoo P, Naicker S, Ohaebosim P, Storm N, Hellferscee O, Ming Sun LK, Mogodi B, Prabdial-Sing N, du Plessis D, Greyling D, Loubser S, Goosen M, McCulloch SD, Scott TP, Moerdyk A, Dlamini W, Konneh K, Kamara IL, Sowa D, Sorie S, Kargbo B, Madhi SA, South African Ebola diagnostic response in Sierra Leone: A modular high biosafety field laboratory, PLoS Negl Trop Dis 11 (2017) e0005665. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0005665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Park JY, Welch MW, Harmon KM, Zhang J, Piñeyro PE, Li G, Hause BM, Gauger PC, Detection, isolation, and in vitro characterization of porcine parainfluenza virus type 1 isolated from respiratory diagnostic specimens in swine, Vet Microbiol 228 (2019) 219–225. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2018.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Sudeep AB, Yadav PD, Gokhale MD, Balasubramanian R, Gupta N, Shete A, Jain R, Patil S, Sahay RR, Nyayanit DA, Gopale S, Pardeshi PG, Majumdar TD, Patil DR, Sugunan AP, Mourya DT, Detection of Nipah virus in Pteropus medius in 2019 outbreak from Ernakulam district, Kerala, India, BMC Infect Dis 21 (2021) 1–7. 10.1186/s12879-021-05865-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Balasubramanian R, Mohandas S, Thankappan UP, Shete A, Patil D, Sabarinath K, Mathapati B, Sahay R, Patil D, Yadav PD, Surveillance of Nipah virus in Pteropus medius of Kerala state, India, 2023, Front Microbiol 15 (2024) 1342170. 10.3389/fmicb.2024.1342170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Mærkedahl RB, Frøkiær H, Lauritzen L, Metzdorff SB, Evaluation of a low-cost procedure for sampling, long-term storage, and extraction of RNA from blood for qPCR analyses, Clin Chem Lab Med 53 (2015) 1181–1188. 10.1515/cclm-2014-1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Davies KA, Welch SR, Sorvillo TE, Coleman-McCray JAD, Martin ML, Brignone JM, Montgomery JM, Spiropoulou CF, Spengler JR, Optimal reference genes for RNA tissue analysis in small animal models of hemorrhagic fever viruses, Sci Rep 13 (2023). 10.1038/s41598-023-45740-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Nolan T, Huggett JF, Sanchez E, Good practice guide for the application of quantitative PCR (qPCR), LGC; (2013) 11–12. [Google Scholar]

- [24].Thierry-Mieg D, Thierry-Mieg J, AceView: a comprehensive cDNA-supported gene and transcripts annotation., Genome Biol 7 Suppl 1 (2006) 1–14. 10.1186/gb-2006-7-s1-s12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Gilleland RC, Hockett RD, Stability of RNA molecules stored in GITC, Biotechniques 25 (1998) 944–948. 10.2144/98256bm03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].AbouHaidar MG, Ivanov IG, Non-enzymatic RNA hydrolysis promoted by the combined catalytic activity of buffers and magnesium ions, Zeitschrift Fur Naturforschung - Section C Journal of Biosciences 54 (1999) 542–548. 10.1515/znc-1999-7-813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Chatterjee A, Zhang K, Rao Y, Sharma N, Giammar DE, Parker KM, Metal-Catalyzed Hydrolysis of RNA in Aqueous Environments, Environ Sci Technol 56 (2022) 3564–3574. 10.1021/acs.est.1c08468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Zaksas NP, Soboleva SE, Nevinsky GA, Twenty Element Concentrations in Human Organs Determined by Two-Jet Plasma Atomic Emission Spectrometry, Scientific World Journal 2019 (2019). 10.1155/2019/9782635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Chheda U, Pradeepan S, Esposito E, Strezsak S, Fernandez-Delgado O, Kranz J, Factors Affecting Stability of RNA – Temperature, Length, Concentration, pH, and Buffering Species, J Pharm Sci 113 (2024) 377–385. 10.1016/j.xphs.2023.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Nordberg M, Nordberg GF, Metallothionein and Cadmium Toxicology—Historical Review and Commentary, Biomolecules 12 (2022). 10.3390/biom12030360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Pastore A, Federici G, Bertini E, Piemonte F, Analysis of glutathione: Implication in redox and detoxification, Clinica Chimica Acta 333 (2003) 19–39. 10.1016/S0009-8981(03)00200-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Parkinson EK, Adamski J, Zahn G, Gaumann A, Flores-Borja F, Ziegler C, Mycielska ME, Extracellular citrate and metabolic adaptations of cancer cells, Cancer and Metastasis Reviews 40 (2021) 1073–1091. 10.1007/s10555-021-10007-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Zhang H, Liu Y, Yu B, Lu R, An Optimized TRIzol-Based Method for Isolating RNA from Adipose Tissue, Biotechniques 74 (2023) 203–209. 10.2144/BTN-2022-0120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Kukurba KR, Montgomery SB, RNA sequencing and analysis, Cold Spring Harb Protoc 2015 (2015) 951–969. 10.1101/pdb.top084970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Sellin Jeffries MK, Kiss AJ, Smith AW, Oris JT, A comparison of commercially-available automated and manual extraction kits for the isolation of total RNA from small tissue samples, BMC Biotechnol 14 (2014). 10.1186/s12896-014-0094-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Kornienko IV, Aramova OY, Tishchenko AA, Rudoy DV, Chikindas ML, RNA Stability: A Review of the Role of Structural Features and Environmental Conditions, Molecules 29 (2024). 10.3390/molecules29245978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.