Abstract

Background

Emotional intelligence is crucial in nursing care. This study aimed to develop and evaluate an emotional intelligence training program based on Demirel’s Program Development Model and Bar-On EQ Model.

Methods

The study is a randomized controlled trial with experimental, placebo, and control groups. The study was conducted with the population of the first year students (n:250) studying in the nursing faculty of a research university. The students were randomly placed in experimental (n = 20), control (n = 20), and placebo (n = 20) groups. Bar-On Emotional Quotient Inventory (EQ-i) was used to measure emotional intelligence. The intervention lasted 8 weeks. Blinding and synchronized placebo training were applied to minimize bias. The Emotional Intelligence Training Program developed, was applied as the intervention in the study. In order to minimize the risk of interaction, a different training program was synchronously applied to the placebo group. In order to create the illusion that the training initiative was the same for this group, a training initiative on environmental awareness, which is a different subject, was applied in the same number of sessions and duration. In the analysis of the data, SPSS 25 package software were employed.

Results

In the measurements performed following the training intervention, it was determined that the students in the experimental group had significantly higher emotional intelligence mean score compared to pre-training period mean score and the students in the placebo and control groups. The post-training emotional intelligence scores (Mean ± SD) were: Experimental group 3.66 ± 0.13, Control group 3.11 ± 0.30, Placebo group 3.35 ± 0.28. The experimental group showed significant improvement. The pre-training and post-training emotional intelligence scores (Mean ± SD) were: Experimental group: 3.22 ± 0.63 (pre), 3.66 ± 0.13 (post); Control group: 3.28 ± 0.62 (pre), 3.11 ± 0.30 (post); Placebo group: 3.51 ± 0.49 (pre), 3.35 ± 0.28 (post). The experimental group showed significant improvement (p < 0.001, d = 1.2).

Conclusions

In conclusion, it was observed that the emotional intelligence training program developed and applied to the nursing students was effective in increasing total emotional intelligence scores by approximately 13.7% compared to the pre-training level. The findings indicate that the program can effectively enhance emotional intelligence in nursing students and is applicable within nursing curricula.’

Trial registration

The study was conducted in line with the CONSORT diagram. The study registered ClinicalTrials.gov. ID: NCT05379361 (date: 2022-05-17).

Keywords: Emotional intelligence, Education, Nursing, Students, Randomized controlled trials

Introduction

The concept of emotional intelligence (EI) has received increasing attention in recent years as a key component in professional and social success [1, 2]. Emotional intelligence refers to a combination of emotional and social skills that influence the way individuals perceive and express themselves, develop and maintain social relationships, cope with challenges, and use emotional information effectively [3, 4].

In a rapidly changing world, our lives are changing with the scientific, social, and technological developments and, artificial intelligence-driven information technology and new knowledge, skills and competencies are needed. In order to secure this knowledge, skills and competence, it is necessary to acquire emotional competencies [5]. It has been emphasized that emotional intelligence skills are important for nurses, who work in environments loaded with emotions, to provide effective health care and work efficiently [2, 6]. Nursing students, who will be in constant interaction with people as professional nurses in the future, are expected to give the best care to the patient and healthy individual/society in the light of the knowledge and skills they have acquired. The process of giving care to patients; even in difficult situations such as illness, violence, sadness, crisis and death, it requires the fulfillment of professional roles by using skills such as active listening, understanding the individual, empathy and effective communication [7–9]. For this reason, in order to move the nursing profession forward, there is a need to develop emotional intelligence skills in nursing students and nurses [10–12].

It is possible to improve nurses’ emotional intelligence through training programs that will ensure the development of emotional intelligence during their professional education [12]. Emotional intelligence affects students’ academic achievements [10, 11, 13], coping with difficulties in life and psychological stress [14], and teamwork [15, 16]. Studies conducted with the participation of nursing students [10–12] have revealed that students’ emotional intelligence skills could not be improved adequately during their education. When nursing education programs are examined [12, 17], it is seen that contents and applications that focus on the improvement of emotional intelligence are limited [10]. When the literature was reviewed in terms of international studies that focused on the improvement of emotional intelligence skills [18, 19], although there are training programs that utilize established models such as Goleman’s or Mayer-Salovey’s frameworks, no emotional intelligence training program was identified that is both based on a model and systematically structured in accordance with a formal program development process. Hence, the information provided above points to a need for the improvement of nurses’ emotional intelligence skills through training programs based on a certain model. Hence, the information provided above points to a need for the improvement of nurses’ emotional intelligence skills through training programs based on a certain model.

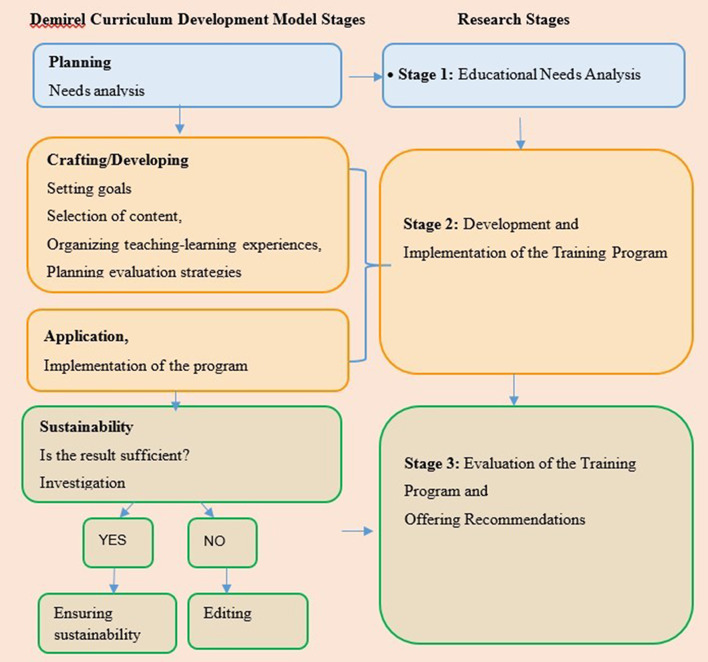

Although some training programs addressing emotional intelligence exist, most lack a systematic development model. This study utilizes Demirel’s Program Development Model, which is grounded in the philosophy of competency-based and learner-centered education and aligns well with nursing education (Fig. 1). It incorporates a comprehensive approach through three stages: needs analysis, program design and implementation, and program evaluation.

Fig. 1.

Demirel curriculum development model stages and research stages

To address these gaps, we developed and evaluated an EI training program using Demirel’s model and Bar-On’s framework, hypothesizing it would improve nursing students’ EI scores versus controls. The study was conducted to develop and evaluate the effectiveness of a training program based on the lack of an educational initiative suitable for the curriculum development process on the emotional intelligence of a cohort of nursing students. This research is unique and valuable in that it presents an EI training program based on an international model to the nursing literature, based on the Bar-on EI model, which comprehensively addresses all dimensions of emotional intelligence in an international context.

Method

Study design

The study is a randomized controlled trial with experimental, placebo, and control groups.

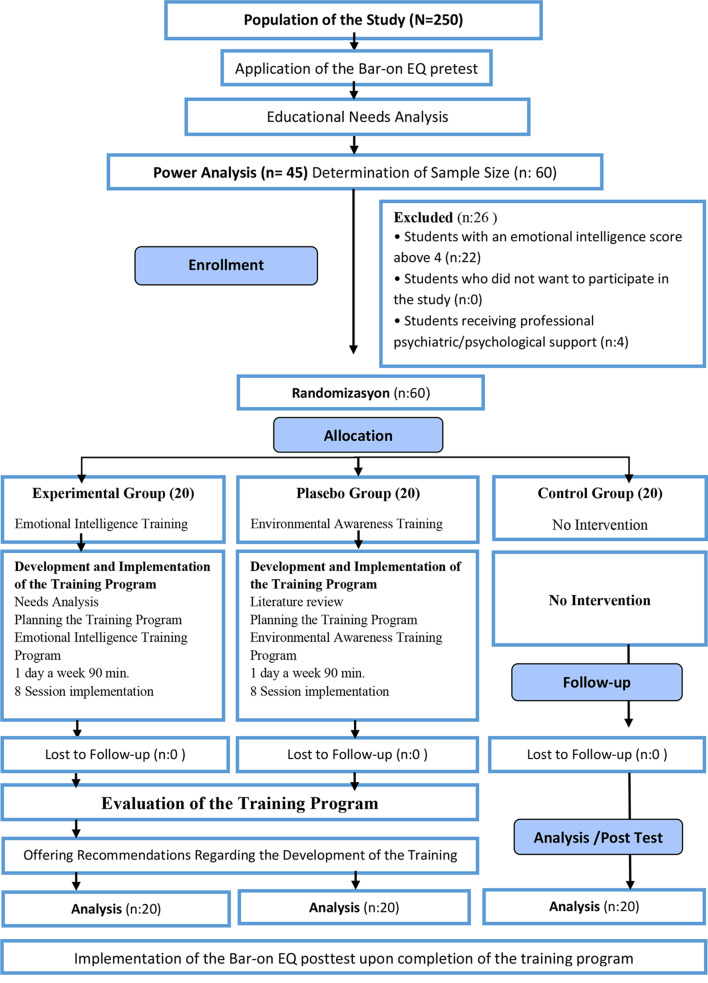

In the research, a training program was applied as an initiative. The study was conducted in line with the CONSORT diagram and was published in Clinical Trial (ID: NCT05379361).

In the research answers to the following hypotheses were sought:

H1: The emotional intelligence mean score of the experimental group is after training is significantly higher compared to score of before training.

H2: The emotional intelligence mean score of the experimentalgroup after training is significantly higher compared to the mean scores of the control and placebo groups at follow-ups.

Researchpopulation and sample

The research population consisted of the first year students of the nursing faculty (N = 250) of a research university. Rationale for choosing first-year students: they have not yet received professional education that could bias results. The study sample was calculated (with g-power) through power analysis with Type I margin of error 0.05 and Type II margin of error 0.10. The number of the students to be included in the study was determined to be 45 in total with 15 students in each group. Considering the probability of data loss and risks related to group cohesion, the study sample was formed of 60 students with 20 students in each group. In multiple groups the assumed effect size is expected high value (Cohen’s f > 0.40) and in terms of emotional intelligence score averages, the Cohen’s f value between groups was calculated as 0.75 [20].

Randomization

The students were randomly selected and assigned to experimental, control and placebo groups. In the pre-test, students completed the Bar-On EQ scale by using nicknames to ensure anonymity. (Fig. 2). To prevent researcher bias, these nicknames (n = 224) were listed and assigned random serial numbers using www.random.org. Based on these random numbers, 60 students were selected for the study. A separate list was used to later match nicknames to actual students, but the contact information was blinded during selection to maintain allocation concealment. Group assignments were made randomly using Excel, without knowledge of the students’ identities. Educators delivering the interventions were also blinded to group allocation, as the assignments were based on anonymous numbers, ensuring allocation concealment and minimizing performance bias. After group assignments were finalized, nicknames were matched back to student identities for implementation.

Fig. 2.

Study flowchart

Participants did not know which group they were in during the study. To minimize intergroup communication bias—given that all students were from the same faculty—a placebo group received a parallel environmental awareness training program, which was prepared in line with the relevant literature [21, 22] structured similarly to the emotional intelligence training. This approach helped reduce expectancy effects and maintain blinding during implementation.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria for the study were determined for students as having a mean score between 1 and 4 on the pretest emotional intelligence scale and being voluntary to particpate in the study. Participants with an high (> 4) emotional intelligence score had the risk of presenting statistically ineffective intermittent data in terms of measuring the effect of the attempt to improve the emotional intelligence skills were excluded in the study. Emotional intelligence skills of these participants were already considered high and it was decided that there was no need for development. Students who received or were receiving professional psychological or psychiatric support were excluded from the study because of the risk that the professional therapeutic process they received would have a positive impact on the development of EI. Because if this risk had not been eliminated, it would have prevented the effectiveness of the implemented program from being evaluated realistically. The students who had taken or were currently taking professional psychological or psychiatric support (n = 4) and students with EI score above 4 (n:22) were excluded from the study. This cutoff was based on prior studies suggesting that individuals with higher baseline EI levels demonstrate limited measurable gains from training interventions, due to ceiling effects. Therefore, including such participants could reduce the sensitivity of outcome assessments and mask the true effectiveness of the intervention. Educator followed a standardized handbook developed based on the training protocol.

Data colecction tools

Identifying information form

The form consisted of 9 questions inquiring about the sociodemographic characteristics (gender, age, family type, etc.) of the students and their characteristics related to emotional intelligence.

The Bar-On emotional quotient inventory (Bar-On EQ-I)

The Bar-On EQ-I was developed by Bar-On (1997). Turkish validity and reliability study of the inventory was conducted by Acar (2002) [23]. The inventory consists of 5 dimensions, 15 subdimensions, and 88 items. The dimensions are Intrapersonal EQ (27 items) Interpersonal EQ (18 items), Adaptability EQ (15 items), Stress Management EQ (12 items), and General Mood EQ (11 items). The subdimensions of the inventory are Optimism (4 items), Happiness (7 items), Impulse Control (6 items), Stress Tolerance (7 items), Flexibility (5 items), Reality Testing (15 items), Problem Solving (5 items), Social Responsibility (6 items), Interpersonal Relations (7 items), Empathy (5 items), Independence (5 items), Self-Actualization, Self-Regard (6 items), Assertiveness (6 items), and Emotional Self-Awareness (6 items). There are affirmative and negative statements on the inventory. The 5-point Likert type scale is scored between 1– Totally Agree and 2– Totally Disagree. The negative items are reversely scored. The value to be sobtained is evaluated according to the height of the average value obtained by dividing the total score in dimensions and sub-dimensions by the number of items. The average value that can be obtained varies between 1 and 5. High scores obtained from the scale indicate higher levels of emotional intelligence. In Acar’s study, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of the total scale was found as 0.83, while the Cronbach’s alpha coefficients of the subdimensions were 0.80 for Intrapersonal EQ, 0.77 for Interpersonal EQ, 0.65 for Adaptability EQ, 0.73 for Stress Management EQ, and 0.75 for General Mood EQ. In the present study, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of the total scale was determined to be 0.95, and the Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were found to be 0.93 for Intrapersonal EQ, 0.94 for Interpersonal EQ, 0.77 for Adaptability EQ, 0.74 for Stress Management EQ, and 0.87 for General Mood EQ.

Training program evaluation form

The form prepared by the researchers is made up of 23 questions in which the students evaluate the purpose, functioning, effects, environment, and activities of the training program [24, 25]. The 5-point Likert type scale is scored as 1- Totally Disagree and 5– Totally Agree. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of the scale was found as 0.86.

Data collection

Workflow of the research

In the study, the processes and stages included in Demirel’s Program Development Model [26] were followed. The educational program development process is based on an approach and model, and there are many models in the literature on program development. In program development studies, it is important to determine accurately and objectively whether the chosen approach or model to be developed is suitable for the desired result with the program in terms of philosophy, structure and stages [26, 27]. For this reason, Demirel’s Program Development Model was used in the study as it overlaps with the higher education system and nursing philosophy in international conjecture, as well as being comprehensive and updated [26]. Accordingly, the study was carried out in there stages (Fig. 1).

In the first stage of the study, a needs analysis was performed. In the second stage, the training program was planned and implemented, and finally, in the third stage, the training program was evaluated (Fig. 2). This study was conducted from September 2018 to July 2020.

Stage 1: Educational needs analysis

In identifying the educational needs, descriptive needs analysis approach was adopted. In the needs analysis, the answer to the question “What are the needs of nursing students in terms of emotional intelligence training program? was sought. Individual in-depth interviews were held with the stakeholders of nursing education (faculty members, nurses, nursing students, and individuals receiving healthcare services) by using the maximum heterogeneity sampling method, and needs analysis was continued until data saturation was achieved (3 faculty members, 7 nurses, 10 nursing students, and 5 patients). The data obtained were categorized by themes, and a content analysis was performed. In the light of the data obtained from this analysis, the following judgements were made:

Emotional intelligence skills are a prerequisite for nursing; emotional intelligence skills of nursing students are inadequate and need to be improved throughout undergraduate education.

In order to improve nursing students’ emotional intelligence skills, it is necessary to diversify and improve teaching methods, to include interactive methods in the curriculum, and to increase the amount of methods, contents, and experiences with emotional content.

A training program that focuses on the improvement of emotional intelligence should be developed through methods such as psychodrama, role-play, case study, and case analysis,

Stage 2: Development and implementation of the training program

There are different approaches to EI in terms of conceptual and modeling in the literature. It is seen that skill-based and mixed models have been developed regarding the concept of emotional intelligence [4, 12, 28, 29]. In talent-based models, emotional intelligence is considered as a group of abilities, while in mixed models, it is considered together with its cognitive, affective, intuitive and social components. For this reason, the “Bar-On Emotional Intelligence Model” developed by Bar-On, which is one of the mixed models, was used in the research. As “Bar-On Emotional Intelligence Model” is comprehensive and widely used, and overlaps with nursing skills such as empathy, interpersonal relations, social responsibility awareness, problem solving, independence, emotional commitment, and emotional self-awareness [4, 30–32], it was used in the study.

These two models (Bar-on EQ and Demirel Program Development Model)were employed in the study in an integrated in the development of the training program. In this context, in the study, the emotional intelligence training program (EITP) was based on Bar-On EQ model in terms of emotional intelligence model and developed in line with Demirel’s Program Development Model in terms of program/curriculum development model in education [26].

The training program was planned as follows in line with the results obtained from the needs analysis and Bar-On Model [4, 33]. In the training program, it was aimed to improve the students’ emotional intelligence skills. To this end, Emotional Intelligence Concept, Intrapersonal Awareness, Interpersonal Relations and Communication Skills, Social responsibility and Empathy, Flexibility, Reality Testing, Problem Solving and Critical Approach, Stress Management, Coping with Stress, Happiness, and Optimism were included in the training program (Table 1).

Table 1.

Structure of the education process

| Sessions | Aim | Contents | Method/Activity | Evaluation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1. Session: Meeting, Program and Emotional Intelligence Promotion |

Students establish a trusting relationship by getting to know the educator and group members and explain the concept of emotional intelligence. |

1.Introduction of the Educator and the Program 2. Feeling Confident 3. Keeping a Journal 4.The concept of emotional intelligence |

1. Sociometric study 2. Program introduction 3.Trustactivity: Psychodrama: Creating an Emotion Pool and Group Sculpture 4. Group sharing 5. Presentation |

Receiving written feedback |

|

2. Session: Personal Awareness |

Students’ desire to realize their individual characteristics and potential and to strengthen them, and regular application of developmental exercises. |

1. Self-Awareness and Independence 2. Self-Respect 3. Self-Awareness and Self-Actualization |

1. Warm-up Activity: Important Thing About Myself & About You 2. Self-description and analysis with drawing 3. Consistency Agreement (Homework) 4. Group sharing |

1.Receiving written feedback 2. Student dairy analysis 3. Drawing description |

| 3. Session: Interpersonal relationships and communication skills | Students’ establish and maintain effective communication and positive interpersonal relationships. |

1. Interpersonal Relationships 2. Effective Communication (Verbal and Non-Verbal Communication, Active Listening and Attention) |

1. Warm-up activity: Social Self (Psychodrama Social Atom Study) 2. Effective communication activity: Nonverbal and Verbal Speech Activity |

1. Self-Assessment, Peer-Assessment 2. Receiving written feedback 3.Assignment evaluation 4.Student dairy analysis |

|

4. Session: Social responsibility and empathy |

Students should act empathetically by taking part in individual and social responsibility projects. |

1. Social Responsibility Awareness 2. Social Responsibility Projects and Their Importance 3. Empathy |

1. Warm-up activity: Being Disabled in Turkey 2. Social Responsibility Projects and Their Importance 3. Think & Write! Values Sheet Exercise Homework 4. Brainstorm Project Ideas |

1. Self-Assessment, Peer-Assessment 2. Receiving written feedback 3. Project Proposal Report 4. Student dairy analysis |

| 5. Session: Flexibility, realism | Students can manage moments of conflict by facing real situations |

1. Compliance with Terms 2. Resilience and Conflict Management 3. Realism |

1. Warm-up activity: Being Cat and Dog Role Reverse 2. Conflict Management (Case Study) 3. Psychodrama Study |

1. Self-Assessment, Peer-Assessment 2.Receiving written feedback 3.Student dairy analysis |

| 6. Session: Problem solving and critical approach | Students solve the problems they experience with a critical approach |

1. Problem solving process and Nursing 2. Critical Approach |

1. Warm-up Activity (Problem Story Summer Activity Psychodramatic Work for the Other Group) 3. Problem Solving- (Case Study) 4. Reflection Exercise: Animation |

1. Self-Assessment, Peer-Assessment 2. Receiving Written Feedback (Training Session Evaluation Form) 3.Student dairy analysis |

|

7. Session: Stress management, coping with stress |

Students’ ability to cope with stress effectively |

1. Positive and Negative Stress 2. Impulse Control 3. Stress Tolerance 4. Coping with Stress |

1.Warm-up Activity: Psychodrama(Fairytale work) 2. Response to Stress (Simulation) 3.Anger-Emotion Management: Internal Support-Getting Help Exercise 4. Effective Coping with Stress - Breathing & Relaxation |

1. Self-Assessment, Peer-Assessment 2. Receiving written feedback 3. Student dairy analysis |

| 8. Session: Happiness and optimism, termination of education | Students should exhibit a positive mood and optimistic approach in life. |

1. Happiness and Optimism 2. Future Life and Hope |

1. Warm-up Activity (Me after 10 years Psychodramatic Study) 2. Film Analysis Concentrating on the Feeling of Hope (Movie: Don’t Lose Hope) 3. There is a Letter from the Future! 4. Our Development in the Training Program (Past me-Present me and Group Statue Change Process) |

1. Self-Assessment, Peer-Assessment 2. Receiving Written Feedback 3. Student dairy analysis 4. Comparison of Beginning and Ending Sculpture |

Educator handbooks were prepared in designing training programs. Factors for all elements of the training process, such as goals and objectives for all planned training sessions, content, training methods and strategies, training materials, duration, evaluation methods, have been determined and the instructions have been written in detail. After the design of the educator’s handbook was completed, it was presented to 3 expert opinions. Expert opinions contributed to the training methods, and after it was finalized, the process was carried out using the book in the training program.

In the implementation of the training program, teaching methods such as sociometric studies, psychodrama, discussion, project preparation, brainstorm, reflection practice, case study, demonstration, story drama, simulation, role-play, assignment, and teaching materials such as slideshows, movies, videos, drawing and painting paper, flip chart, and notebook were used (Table 1).

Researchers involved in the development and planning of the training program are also the educators of the training program. One of the trainers has a Jungian psychodrama practitioner certificate trained from an organization with reference to FEPTO (European Federation of Psychodrama Training Organizations). The training program was planned and implemented as 8 sessions (8 weeks) a day per week with each session comprising of two 45-minute classes (90 min). 2 make-up sessions were held for the students who could not join the sessions. The sessions and training program were evaluated through written and verbal feedback, diary analysis, picture, material, and project analysis, and self-evaluation and peer evaluation (Table 1).

While the EITP plan was applied to the intervention group, the training program with the same number of sessions, duration and intervention forms on environmental awareness was applied to the placebo group as an intervention (Fig. 2). In the training applied to the placebo group, only the training contents were prepared on environmental awareness and the students were not informed that the contents were different.

The placebo program consisted of interactive but emotionally neutral content such as recycling practices, environmental sustainability, climate change awareness, and ecological footprint calculation. Methods included group discussions, infographic analysis, video screenings, and simple project planning. No content overlapped with emotional intelligence skills or themes (e.g., empathy, interpersonal relationships, self-awareness), ensuring the placebo program was inert regarding EI development.

Educators followed a standardized handbook prepared for the program, which included detailed objectives, methods, materials, duration, and assessment tools for each session. In addition, sessions were recorded for fidelity checks, and educators documented adherence to the plan using session checklists.

Stage 3: Evaluation of the training program and offering recommendations

Throughout the training program implementation, various evaluations were made in order to assess the students, the program, educational activities, and other learning dynamics. These evaluations were made by the researchers following each session, and the program was continued considering the results of the evaluations.

Data analysis

Before the intervention, baseline equivalence between the intervention and placebo groups was tested. There was no statistically significant difference between the groups in terms of sociodemographic characteristics and total/subscale EI scores at baseline (p > 0.05), indicating balanced groups.

In the analysis of the data, descriptive statistics methods (Shapiro-Wilk and Kolmogorov-Smirnov normality tests, mean, standard deviation, frequency, percentage distributions) through SPSS 25 package software, independent samples t-test, paired samples t-test, Mann-Whitney U test, Wilcoxon signed-rank test, parametric and non-parametric tests, and Bonferroni and Tukey tests among the multiple comparison (post hoc) tests for intergroup comparisons were employed.

Ethical aspect of the study

All procedures performed in this study were guided by the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethics Committee approval (dated x and numbered y) and written institutional permission from the faculty where the study was conducted were obtained for the study. In addition, the students’ written consents and the author’s permission to use the scale were obtained as well.

Findings

Descriptive characteristics

The descriptive characteristics of the students included in the study groups are presented in Table 1. In all study groups, 75% of the students were female. 75% of the experimental group students, and 85% of the control and placebo group students were graduates of Anatolian High School. 65% of the experimental group and 60% of the placebo group lived with their families, while 65% of the students in the control group lived in dormitories. The parents of 95% of the students lived in the same home. 80% of the students in the experimental group and 70% of the students in the control group had two and more siblings, while 65% of the students in the placebo group had only one sibling. Homogeneity between the groups before the training was checked, and no statistically significant difference was found (Table 2).

Table 2.

Sociodemographic distribution of study groups and homogenization between groups

| Variables | Experimental Group (a) | Control Group (b) | Plasebo Group (c) | Total | Significance (p) | Test Value ** | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |||||

| Gender | p,168* | χ2 = 3,562 | ||||||||||

| Female | 15 | 75 | 15 | 75 | 1 | 95 | 49 | 81,7 | ||||

| Male | 5 | 25 | 5 | 25 |

9 1 |

5 | 11 | 18,3 | ||||

| Graduated School Type | p,519* | KW = 7,163 | ||||||||||

| Anatolian High School | 15 | 75,0 | 17 | 85,0 | 17 | 85,0 | 49 | 81,7 | ||||

| Science High School | 0 | 1 | 5,0 | 1 | 5,0 | 2 | 3,3 | |||||

| General High School | 0 | 10,0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 10,0 | 4 | 6,7 | ||||

| Health Vocational High School | 2 | 10,0 | 2 | 10,0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 6,7 | ||||

| Religious Vocational High School |

2 1 |

5,0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1,7 | ||||

| Where he lives | p,139* | KW = 3,951 | ||||||||||

| With His/Her Family | 10 | 50,0 | 8 | 40,0 | 14 | 70,0 | 32 | 53,3 | ||||

| In a Dormitory | 40,0 | 11 | 55,0 | 6 | 30,0 | 25 | 41,7 | |||||

| In Shared House/Pension | 8 | 5,0 | 1 | 5,0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3,3 | ||||

| Alone |

1 1 |

5,0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1,7 | ||||

| Number of Siblings | p,263* | KW = 2,674 | ||||||||||

| Has no Siblings | 0 | 0 | 1 | 5,0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1,7 | ||||

| Has a Sibling | 3 | 15,0 | 6 | 30,0 | 7 | 35,0 | 16 | 26,7 | ||||

| Has two or more Siblings | 17 | 85,0 | 13 | 65,0 | 13 | 65,0 | 43 | 71,7 | ||||

| ±SD |

±SD

±SD

|

±SD

±SD

|

±SD

±SD

|

Significance (p) | Test Value ** | |||||||

| Bar-On EQ Scale Score | 20 | 3,22 ± 0,63 | 20 | 3,28 ± 0,62 | 20 | 3,51 ± 0,49 | 60 | 3,35 ± 0,50 | p,377* | F=,992 | ||

| Age | 20 | 18,85 ± 1,63 | 20 | 18,50 ± 1,05 | 20 | 18,30 ± 1,26 | 60 | 18,55 ± 1,33 | p,311* | χ2 = 16,034 | ||

* p > 0.05

**  : Average/mean score, SD: Standart Deviation, F:One Way Anova, χ2: Pearson Chi-Square, KW: Kruskal-Wallis value

: Average/mean score, SD: Standart Deviation, F:One Way Anova, χ2: Pearson Chi-Square, KW: Kruskal-Wallis value

Findings regarding emotional intelligence skills

It was determined that the pre-training emotional intelligence mean score was 3.22 ± 0.63 for the experimental group, 3.28 ± 0.62 for the control group, 3.51 ± 0.4 for the placebo group, and that there was no statistically significant difference between the groups (p > 0.05) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Comparison of mean scores of EQ dimensions by groups and time

| Group/Time | Experimental (a)  ±SD ±SD |

Control (b)  ±SD ±SD |

Plasebo (c) ±SD ±SD |

Test and Significance * | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self Awareness |

**** Pre-T |

3,26±,66 | 3,33±,73 | 3,56±,60 | F*=,647 p**,527 |

| Post-T | 3,38±,45 | 3,10±,19 | 3,11±,18 | F*=2,604 p,017 | |

| Test and Significance ** |

t = 2,604 p,017 |

t = 1,293 p,211 |

t = 3,097 p,006 |

a > b > c*** | |

| Intrapersonal Eq | Pre-T | 3,22±,80 | 3,53±,97 | 3,77±,77 | F*=,479 p,622 |

| Post-T | 4,15±,39 | 3,44±,64 | 3,69±,75 | F*=6,817 p ,002 | |

| Test and Significance ** |

t = 4,211 p,000 |

t=,343 p,736 |

t=,327 p,747 |

a > b*** | |

| Adaptability | Pre-T | 3,03±,57 | 3,12±,53 | 3,38±,48 | F = 1,752 p,183 |

| Post-T | 3,51±,38 | 3,11±,28 | 3,13±,25 | F = 10,437 p ,000 | |

| Test and Significance ** |

t = 3,012 p ,007 |

t=,022 p,983 |

t = 2,092 p,050 |

a > c > b*** | |

| Stress Management | Pre-T | 2,81±,60 | 2,88±,52 | 3,04±,59 | F=,534 p,589 |

| Post-T | 3,33±,22 | 2,86±,35 | 2,70±,29 | F = 25,275 p ,000 | |

| Test and Significance ** |

t = 3,873 p,001 |

t=,142 p,889 |

t = 1,965 p,064 |

a > b > c*** | |

| General Mood | Pre-T | 2,89±,58 | 3,42±,81 | 3,61±,78 | F=,803 p,453 |

| Post-T | 3,93±,47 | 3,06±,47 | 3,11±,35 | F = 24,707 p,000 | |

| Test and Significance ** |

t = 7,300 p,000 |

t = 1,826 p,084 |

t = 2,696 p,014 |

a > b > c*** | |

| Total Scale | Pre-T | 3,22±,63 | 3,28±,62 | 3,51±,49 | F=,992 p,377 |

| Post-T | 3,66±,13 | 3,11±,30 | 3,35±,28 | F = 29,087 p ,000 | |

| Test and Significance ** |

t = 3,086 p,006 |

t = 1,074 p,296 |

t = 1,564 p,134 |

a > b, a > c*** | |

*  : Average/mean score, SD: Standart Deviation, F:One Way Anova value

: Average/mean score, SD: Standart Deviation, F:One Way Anova value

** Test and Significance: Paired-Samples t test

***Post hoc tests: Bonferroni and Tukey

**** Pre-training and Post-training

It was found that the pre-training emotional intelligence mean score of the experimental group was 3.22 ± 0.63 and post-training score was 3.66 ± 0.13, and that the difference was statistically significant (p < 0.05) in favor of the post-training mean score. The experimental group students’ post-training mean scores were found to be statistically higher compared to their pre-training mean scores in all scale dimensions (Table 3).

It was determined that the post-training mean scores of the experimental group in the dimensions of Intrapersonal EQ, Adaptability EQ, Stress management EQ, General Mood EQ were significantly higher compared to the mean scores of the control and placebo groups (p < 0.05). When the direction of the difference was examined, it was seen that the post-training mean scores of the experimental group in the dimensions of Intrapersonal EQ, Adaptability EQ, Stress Management EQ, and General Mood EQ were significantly higher than the control group, and the mean scores of the control group were significantly higher than the mean scores of the placebo group (p < 0.05). A significant difference in terms of Interpersonal EQ dimension was found between the post-training mean score of the experimental group and the mean score of the control group (p < 0.05). In this dimension, no significant difference was found between the experimental group and the placebo group, and between the control group and the placebo group (p > 0.05). Regarding the total scale, it was determined that the post-training emotional intelligence mean score was 3.66 ± 0.13 in the experimental group, 3.11 ± 0.30 in the control group, and 3.35 ± 0.28 in the placebo group, and that the mean score of the experimental group students was significantly higher compared to the students in the control and placebo groups (p < 0.05). It was also determined that the difference between the control and placebo groups was not statistically significant (p > 0.05) (Table 3).

Regarding the control group, it was found that the total scale mean scores of the control group before and after training were respectively 3.28 ± 0.62 and 3.11 ± 0.30, and that the difference between these two scores was not statistically significant (p > 0.05). Similarly, no statistically significant difference was found between the pre-training and post-training mean score in terms of the scale dimensions (p > 0.05). As for the placebo group, it was determined that the total scale mean scores of the placebo group before and after training were respectively 3.51 ± 0.49 and 3.35 ± 0.28, and that the difference between these two scores was not statistically significant (p > 0.05). The difference between the pre-training and post-training mean scores of the placebo group on Interpersonal EQ, Adaptability EQ, and Stress management EQ was found to be statistically insignificant (p > 0.05). However, a statistically significant difference was determined between the pre-training and post-training mean scores of the placebo group on Intrapersonal EQ and General Mood EQ dimensions (p < 0.05), and it was determined that post-training mean scores in both dimensions decreased at a significant level compared to the pre-training mean scores (Table 3).

The pre-training and post-training emotional intelligence subscale mean scores and intergroup differences were examined in the experimental, control, and placebo groups. It was determined in the experimental group that there was a statistically significant difference between pre-training and post-training mean scores in terms of the subscales of Independence, Self-Regard, Assertiveness, Emotional Self-Awareness, Social Responsibility, Interpersonal Relations, Empathy, Flexibility, Reality Testing, Problem Solving, Stress Tolerance, Impulse Control, Optimism, and Happiness (p < 0.05). Regarding the students in the control group, a statistically significant difference was determined between their pre-training and post-training mean scores in terms of the subscales of Independence and Assertiveness (p < 0.05). It was also determined that other than these subscales, there was no statistically significant difference between the control group students’ mean scores in terms of all subscales (p > 0.05). A statistically significant difference was determined between the pre-training and post-training mean scores of the placebo group students in terms of the subscales of Independence, Self-Actualization, Reality Testing, Impulse Control, and Happiness (p < 0.05). Regarding the other nine subscales, no statistically significant difference was found between the pre-training and post-training mean scores of the placebo group students (p > 0.05) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Comparison of mean scores of emotional intelligence sub-dimensions by groups and time

| Group/Time | Experimental (a) ±SD ±SD |

Control (b) ±SD ±SD |

Plasebo (c) ±SD ±SD |

Test and Significance * | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independence |

**** Pre-T |

3,38±,88 | 3,62±,77 | 3,42±,94 | F=,437 p,648 |

| Post-T | 4,09±,83 | 2,59±,73 | 2,37±,84 | F = 26,894p,000 | |

| Test and Significance ** | t = 3,397 p,003 |

t = 3,912 p,001 |

t = 3,162 p,005 | a > b, a > c*** | |

| Self-Actualization | Pre-T | 3,50±,77 | 3,28±,97 | 3,80±,91 | F = 2,433 p,097 |

| Post-T | 4,18±,48 | 3,29±,50 | 3,21±,39 | F = 26,746 p,000 | |

| Test and Significance ** | t=-6,532 p,000 | t=-,035p,973 | t = 2,975 p,008 | a > b, a > c*** | |

| Self-Regard | Pre-T | 3,43±,80 | 3,44±,96 | 3,50±,93 | F=,041 p,959 |

| Post-T | 3,83±,57 | 3,23±,42 | 3,28±,39 | F = 10,041 p,000 | |

| Test and Significance ** | t = 3,302 p,004 | t=,822p,422 | t = 1,024p,319 | a > b, a > c*** | |

| Assertiveness | Pre-T | 3,30±,84 | 3,55±,69 | 3,49±,67 | F=,610 p,547 |

| Post-T | 3,90±,27 | 3,05±,29 | 3,03±,17 | F = 2,243 p,115 | |

| Test and Significance ** | t = 2,187 p,041 | t = 3,126 p,006 | t = 2,795p,012 | - | |

| Emotional Self-Awareness | Pre-T | 3,10±,71 | 3,15±,55 | 3,29±,59 | F=,470p,627 |

| Post-T | 3,93±,39 | 3,26±,46 | 3,50±,59 | F = 9,302p,000 | |

| Test and Significance ** | t=-5,814p,000 | t=-,753 p,461 | t=-1,335p,198 | a > b, a > c*** | |

| Social Responsibility | Pre-T | 4,03±,94 | 3,75 ± 1,01 | 3,50±,89 | F = 1,569 p,217 |

| Post-T | 4,31±,44 | 3,17±,79 | 3,45±,86 | F = 13,523p ,000 | |

| Test and Significance ** | t = 1,648 p,116 | t = 2,241p,307 | t=,162p,873 | a > b, a > c*** | |

| Interpersonal Relations | Pre-T | 3,35±,92 | 3,55 ± 1,01 | 3,49±,97 | F=,238p,789 |

| Post-T | 3,82±,47 | 3,02±,37 | 3,25±,44 | F = 18,242p,000 | |

| Test and Significance ** | t=-2,571p,019 | t = 2,385p,028 | t = 1,013p,324 | a > b, a > c*** | |

| Empathy | Pre-T | 3,79±,84 | 3,67 ± 1,02 | 3,42 ± 1,07 | F=,730p,486 |

| Post-T | 4,22±,41 | 2,98±,91 | 3,12±,95 | F = 14,438p,000 | |

| Test and Significance ** | t = 2,607p, 017 | t=,555p,918 | t=,978p,340 | a > b, a > c*** | |

| Flexibility | Pre-T | 2,69±,72 | 2,91±,60 | 3,17±,52 | F = 2,957 p,060 |

| Post-T | 3,61±,52 | 3,05±,28 | 3,13±,35 | F = 11,404p,000 | |

| Test and Significance ** | t=-5,981p,000 | t=-1,106p,283 | t=,282p,781 | a > b, a > c*** | |

| Reality Testing | Pre-T | 3,36±,78 | 3,15±,73 | 3,17±,60 | F=,529p,592 |

| Post-T | 3,58±,81 | 2,80±,38 | 2,53±,26 | F = 20,157p,000 | |

| Test and Significance ** | t = 2,010p,049 | t = 1,760p,095 | t = 4,292 p,000 | a > b, a > c*** | |

| Problem Solving | Pre-T | 3,53±,91 | 3,24 ± 1,05 | 3,53±,89 | F=,613p,545 |

| Post-T | 4,061±,45 | 3,50±,53 | 3,75±,56 | F = 5,796p,005 | |

| Test and Significance ** | t=-2,850p,010 | t=-,954p,352 | t=-,946p,356 | a > b, a > c*** | |

| Stress Tolerance | Pre-T | 2,71±,68 | 2,62±,70 | 3,00±,74 | F = 1,535 p,224 |

| Post-T | 3,57±,44 | 3,04±,43 | 3,05±,30 | F = 11,489p,000 | |

| Test and Significance ** | t=-4,925p,000 | t=-2,261p,036 | t=-,322p,751 | a > b, a > c*** | |

| Impulse Control | Pre-T | 3,23±,83 | 2,94±,86 | 3,15±,74 | F=,899p,413 |

| Post-T | 3,40±,46 | 2,65±,71 | 2,29±,71 | F = 15,402p,000 | |

| Test and Significance ** | t = 4,152p,001 | t = 1,027p,318 | t = 3,074p,006 | a > b, a > c*** | |

| Optimism | Pre-T | 3,21 ± 1,01 | 3,30 ± 1,02 | 3,64±,85 | F = 2,765 p,071 |

| Post-T | 3,59±,41 | 3,03±,70 | 3,25±,65 | F = 4,336p,018 | |

| Test and Significance ** | t=-3,808p,001 | t = 1,087p,291 | t = 1,659p,114 | a > b*** | |

| Happiness | Pre-T | 3,47±,75 | 3,55±,87 | 3,41±,81 | F = 1,339 p,270 |

| Post-T | 3,69±,63 | 3,08±,40 | 3,05±,28 | F = 12,195p,000 | |

| Test and Significance ** | t = 3,429p,003 | t = 1,049p,324 | t = 2,230p,038 | a > b, a > c*** | |

**  : Average/mean score, SD: Standart Deviation, F:One Way Anova value

: Average/mean score, SD: Standart Deviation, F:One Way Anova value

** Paired-Samples t Test

***Post hoc tests: Bonferroni and Tukey

**** Pre-training and Post-training

The pre-training and post-training total scale mean scores of the students in the groups were examined in terms of differences in the subscales between the groups. It was determined that there was no statistically significant difference between the pre-training subscale mean scores (p > 0.05). When the difference between the groups in terms of post-training subscale mean scores was examined, a statistically significant difference was determined in all subdimensions except the subscale of Assertiveness (p < 0.05). When the direction of the difference was examined, it was seen that there was no statistically significant difference between the experimental and placebo groups only in terms of Optimism subscale (p > 0.05), and that the mean score of the experimental group was significantly higher the mean score of the control group (p < 0.05). When the direction of the difference in other subscales with a significant difference was examined, it was observed that the experimental group had significantly higher scores compared to the control and placebo groups (p < 0.05). In terms of difference between groups, a statistically significant difference was not found between the control and placebo groups (p > 0.05) (Table 4).

Findings regarding the training program

95% of the students in the experimental group stated that the purpose and objectives of the course were comprehensible, and 90% of the students in the experimental group reported that the objectives were in line with their needs.100% of the students thought that the organization of the subjects and content, and the balance between theoretical knowledge and practices was adequate, and 90% found the scope of the program sufficient. 95% of the students found the training material effective, and 100% believed the training methods were used efficiently. While all students stated that the instructor used time effectively, 65% partially agreed that the total duration of the training was sufficient. While 95% of the students found the content of the training implementable, 5% partially agreed with this view. 70% of the students stated that the physical environment was suitable, and 100% reported that the instructor established a comfortable and trust-based communication among the participants. All students in the experimental group believed that the instructor used the skills and emotional skills related to the training processes effectively. All students agreed on the view that the instructor was able to manage his/her own feelings. All students stated that they received feedback throughout the training process, and that they did not suffer any emotional damage. 95% of the students in the experimental group indicated that there was interaction among the participants, and that the training contributed to their individual development.

While the majority of the students in the placebo group evaluated the items related to the training process positively, 100% of them stated that they received feedback at the end of the training, that they did not suffer any emotional damage, that the instructor was understanding and tolerant towards the participants, and that the training program contributed to their development. While 90% of the students stated that the training was suitable for the requirements of the training objectives, 10% partially agreed with this opinion.

Discussion

The research, it was aimed to develop the emotional intelligence skills of nursing students with the training program based on the Bar-On emotional intelligence model and developed in line with the Demirel program development model. Findings showed that the developed training program (EITP) was effective for nursing students. It was determined in the study that the emotional intelligence mean score of the experimental group significantly increased after training compared to their pre-training mean score, and that there was no statistically significant difference in the mean scores of the placebo and control groups. The emotional intelligence mean score of the students in the experimental group significantly increased in comparison to the mean scores of the students in the placebo and control groups.

The hypotheses of the research, “H1: The emotional intelligence mean score of the experimental group is after training is significantly higher compared to score of before training.”, and “H2: The emotional intelligence mean score of the experimentalgroup after training is significantly higher compared to the mean scores of the control and placebo groups at follow-ups” were supported. The effect sizes calculated (Cohen’s d) for total emotional intelligence and subscales showed medium to large effects in the experimental group (e.g., d = 0.73 for total EI score), indicating not only statistical significance but also practical relevance. These findings underscore the robustness of the intervention’s impact.

In their studies, Fletcher et al. (2009) [34], Sharif et al. (2013) [35], Erkayiran and Demirkan (2018) [12], and Shahbazi et al. (2018) [36] determined a signficant increase in emotional intelligence mean scores following the training intervention. When the studies which measured the effect of interventional studies that aimed to improve emotional intelligence skills were examined, it was seen that similar results to the present study were obtained, showing an increase in emotional intelligence skills after the training [29, 37, 38]. Obtaining similar results in this way made us think that the skills included in the emotional intelligence and its sub-dimensions could be developed with the educational initiative, even though the method, sample (participants), approach, quality, or content of the training program changed. Different studies are unique and important in terms of providing evidence about the ways in which these initiatives can be followed. The significant findings presented by this research, unlike the literature, can be considered as drawing attention to the benefit of methods and strategies, such as sociodrama and psychodrama, on emotional intelligence training initiatives in terms of affective domain gains in educational effectiveness. Using teaching methods other than traditional education methods increases their satisfaction [39], affective gains are acquired through experience and these gains are affected by the classroom climate [40], and as the number of days spent in the education group and the common experiences increase, students can feel more belonging, comfort, pleasure and confidence [41–44].

In the present study, it was determined that the emotional intelligence subscales mean score of the students in the experimental group significantly increased after the training compared to their pre-training mean score. The students in the control and placebo group scored significantly lower on some subscales after the training compared to their pre-training scores, and there was no difference between the pre-training and post-training scores on the other subscales. This decline in certain subscales (e.g., Empathy and Flexibility) in the placebo and control groups may be attributed to the natural fluctuations in emotional engagement levels over time when no targeted intervention is provided. It is also possible that being exposed to generic environmental topics without emotional content (as in the placebo group) may have created a contrast effect, leading students to become more aware of but not more skilled in EI-related competencies, especially those requiring interpersonal reflection. In terms of the difference between the groups in terms of the post-training subscale mean scores, it was determined that there was a significant increase in the mean score of the experimental group compared to the control and placebo groups on all subscales except the subscale of Assertiveness. These results show that the content and training activities developed by focusing on sub-skills that form emotional intelligence skills in the development of an emotional intelligence training program was an appropriate approach. The lack of improvement in Assertiveness may stem from cultural or contextual barriers, as assertiveness can be influenced by societal expectations or internalized beliefs among nursing students, particularly in more collectivist settings. Future versions of the training may benefit from integrating role-play or confidence-building strategies tailored specifically to enhance assertiveness. The absence of a difference in the subscale of Assertiveness suggests that the content and training activities in this sub-dimension should be revised and rearranged.

When the studies conducted in the literature on emotional intelligence skills in nursing were reviewed, it was observed that Intrapersonal skills were at a moderate level and above [29], and that they could be improved through interventions such as collaborative learning application [45]. It has been documented that nursing students’ self-regard skills are affected by their satisfaction in the training processes [10]. Although emotional self-awareness is highly important for the nursing students’ interaction process, it can be improved and should be handled together with empathy skill [46].

In studies conducted on interpersonal skills and social responsibility skills, it was determined that nursing students’ interpersonal skills were at a good level [29], interaction training was important for its development, it affected their performance [47], and it was associated with their teamwork attitudes and important for multidisciplinary studies [15]. It was seen that social responsibility skills were at different levels [48], and that social responsibility awareness should be developed for the professionalism of the nursing occupation and the quality of the care provided [49].

Namdar et al. (2009) [50] determined in their study that flexibility in terms of emotional intelligence in nursing students was not high and should be developed. Koç (2020) [51], on the other hand, revealed that cognitive flexibility increased psychological resilience and differentiated the attitudes toward coping with stress. Developed reality testing skills of nursing students are highly important for nursing and nursing education in terms of constituting a basis for evidence-based applications and the development of the profession [52].

Considering that nursing is performed in a highly stressful environment, there are numerous studies that dealt with stress tolerance and problem-solving skills, which are very important for nursing students. Abdollahi et al. (2018) [53] determined that a high level of problem-solving skills in nursing students was associated with perceived stress and therefore a high level of stress tolerance. Zhao et al. (2015) [54] and Abdollahi et al. (2018) [53] revealed that nursing students were faced with many stress factors, that their stress tolerance was low, that their problem-solving skills fell short of coping with stress, and that this skill should be improved. These two sub-dimensions of emotional intelligence skills are discussed in the literature as two concepts that are closely related with each other.

One of the basic factors for a training process to be functional and beneficial is to evaluate the quality of the training [24, 25]. For this purpose, the students’ views on the training program were examined in the study, and it was determined that the students in the experimental group and the placebo group agreed with almost all the items in the form partially and totally. These findings suggest that factors such as method and training environment, which could have an impact on the training process, were positively evaluated by the students, and this positively contributed to achieving the goals and targets determined in the training process [24, 25].

It has been stated in the literature that emotional intelligence training increases the students’ motivation, develops their adaptation skills, increases the quality of their interaction with other students, and helps with the development of social processes [34, 35]. In the activity in which how the students perceived their emotional intelligence development was examined, it was observed that they thought they made progress. The results of the study indicated that the students’ acquired the behavioral change targeted in the training.

Overall, these findings suggest that the training program’s strength lies in its structured design, which targets distinct EI sub-dimensions through experiential, reflective, and group-based learning methods. Rather than assuming general EI improvement, the subscale analysis provides nuanced insight into what works and what needs refinement. Compared with the placebo group, which showed no positive change despite similar group interaction settings, this highlights the importance of content specificity in emotional development interventions.

Conclusion and recommendations

The results of the study offer significant contributions to the field of emotional intelligence training program development in nursing education and to the development of the students’ emotional intelligence skills. The training initiative implemented was effective in the development of the students’ emotional intelligence skills. Emotional intelligence skills significantly developed in the students in the experimental group after the training compared to the students in the control and placebo groups. It was observed that the emotional intelligence training program developed and applied to the nursing students was effective in increasing total emotional intelligence scores by approximately 13.7% compared to the pre-training level. The results obtained from the study showed that the training program developed was effective in terms of improving the students’ emotional intelligence skills.

In the light of these results, it can be recommended that nursing students should be evaluated in terms of emotional intelligence at the beginning of the education process, that the content of the training program should be developed in line with their needs, and that a course on emotional intelligence skills should be incorporated in the curriculum.

The research was contributing to nursing practice. The results reveal the feasibility of this approach to healthcare education and can improve the quality of nursing care and nurse education by improving emotional intelligence skills. This study will contribute to the development of skills that will increase the vital and professional satisfaction of nurses.

The qualitative increase in nursing care, the decrease in care costs and the effective health management will help to reduce the costs of diseases and will have a positive effect on health expenses, which constitute a serious share in the economy. This contribution will also have an impact on the increase of socially healthy individuals and societies, and the potential to create individuals and societies that receive qualified nursing care and will be satisfied with health care services. The results obtained in providing a comprehensive and multidimensional example of an education program at the international level can serve as motivation for research and initiatives aimed at enhancing the global emotional intelligence skills of the nursing profession. This, in turn, can contribute to the increase in effective nursing care globally and the growth of communities worldwide.

The results of the research will be guiding in measuring the current status of nursing students in terms of skills aimed to be acquired in education, measuring the level of achievement of the program outputs, and evaluating the achievements of affective skills.

Research limitations

This study was limited to first-year nursing students from a single university, which affects the generalizability of the results. Moreover, the program’s long-term effects were not evaluated due to the lack of follow-up assessment. Future studies should implement the training in later academic years and conduct longitudinal evaluations to better understand the sustainability and broader impact of the intervention.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- EI

Emotional Intelligence

Author contributions

Study design: NKY, HK. Data collection: NKY, Data analysis: NKY, HK. Study supervision: HK. Manuscript writing: NKY, HK. Critical revisions for important intellectual content: NKY, HK.

Funding

No funding was received for conducting this study.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

In this study, all methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. Ethics Committee approval (dated x and numbered y) and written institutional permission from the faculty where the study was conducted were obtained for the study. In addition, the students’ written consents and the author’s permission to use the scale were obtained as well. Our manuscript is a quantitative research article, in which the necessary data was obtained by filling out a questionnaires, and at the beginning of the questionnaires, informed consent was obtained from the nursing students to participate in the study. Participants were assured of the confidentiality of the information. Approval was obtained from the ethics committee regarding the educational content and process implemented as an initiative. The ethics committee approval (from the Istanbul University-Cerrahpaşa Social and Humanities Research Ethics Committee, date: 07.05.2018 issue: 48747) and the informed consents of the participants were obtained. The study was based on volunteering.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Footnotes

This study was presented as an oral presentation at the 2nd International & 8th National Nursing Education Congress and its summary was published in the congress proceedings book. https://motto.tc/siteler/www.nursingedu8.com/gorseller/files/hemsirelik-egitimi-kongresi-2022-bildiri-kitabi-2.pdf.

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Gómez-Leal R, Holzer AA, Bradley C, Fernández-Berrocal P, Patti J. The relationship between emotional intelligence and leadership in school leaders: A systematic review. Camb J Educ. 2022;52(1):1–21. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hwang WJ, Park EH. Developing a structural equation model from grandey’s emotional regulation model to measure nurses’ emotional labor, job satisfaction, and job performance. Appl Nurs Res. 2022;64:151557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walker SA, Double KS, Kunst H, Zhang M, MacCann C. Emotional intelligence and attachment in adulthood: A meta-analysis. Pers Indiv Differ. 2022;184:111174. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bar-On R. The Bar-On model of emotional-social intelligence (ESI). Psicothema. 2006;13–25. [PubMed]

- 5.Kim SH, Shin S. Social–emotional competence and academic achievement of nursing students: A canonical correlation analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(4):1752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yonck R. Makinenin Kalbi Yapay duygusal Zekâ Dünyasında Geleceğimiz. Çev. Tufan göbekçin. İstanbul: Paloma Yayınevi; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sarıkoç G, Kaplan M. Hemşirelik öğrencilerinin Sosyal duygusal Öğrenme becerileri, Mesleki Benlik Saygısı ve akademik Branş memnuniyetleri Arasındaki Ilişki. Florence Nightingale Hemşirelik Dergisi. 2017;25(3):201–8. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gómez-Díaz M, Delgado-Gómez MS, Gómez-Sánchez R. Education, emotions and health: emotional education in nursing. Procedia-Social Behav Sci. 2017;237:492–8. [Google Scholar]

- 9.McCloughen A, ve Foster K. Nursing and pharmacy students’ use of emotionally intelligent behaviours to manage challenging interpersonal situations with staff during clinical placement: a qualitative study. J. Clin. Nurs. 2018;27(13–14), 2699–2709. 10.1111/jocn.13865 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Sharon D, Grinberg K. Does the level of emotional intelligence affect the degree of success in nursing studies? Nurse Educ Today. 2018;64:21–6. 10.1016/j.nedt.2018.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Snowden A, Stenhouse R, Duers L, Marshall S, Carver F, Brown N, et al. The relationship between emotional intelligence, previous caring experience and successful completion of a pre-registration nursing/midwifery degree. J Adv Nurs. 2018;74(2):433–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Erkayiran O, Demirkiran F. The impact of improving emotional intelligence skills training on nursing students’ interpersonal relationship styles. Int J Caring Sci 2018;11(3).

- 13.Stenhouse R, Snowden A, Young J, Carver F, Carver H, Brown N. Do emotional intelligence and previous caring experience influence student nurse performance? A comparative analysis. Nurse Educ Today. 2016;43:1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang P, Li CZ, Zhao YN, Xing FM, Chen CX, Tian XF, Tang QQ. The mediating role of emotional intelligence between negative life events and psychological distress among nursing students: A cross-sectional study. Nurse Educ Today. 2016;44:121–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rasooli T, Moradi-Joo E, Hamedpour H, Davarpanah M, Jafarinahlashkanani F, Hamedpour R, Mohammadi-Khah J. The relationship between emotional intelligence and attitudes of organizational culture among managers of hospitals of Ahvaz Jundishapur university of medical sciences. Entomol Appl Sci Lett. 2019;6(3):62–7. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Talman K, Hupli M, Rankin R, Engblom J, Haavisto E. Emotional intelligence of nursing applicants and factors related to it: A cross-sectional study. Nurse Educ Today. 2020;85:104271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.YÖKATLAS. (2022). Hemşirelik Lisans Programları Atlası, Erişim Tarihi: 10.01.2022. https://yokatlas.yok.gov.tr/lisans-bolum.php?b=10248

- 18.Papoutsi C, Drigas AS, Skianis C. Serious games for emotional intelligence’s skills development for inner balance and quality of life: a literature review. Retos: nuevas tendencias En educación física. Deporte Y Recreación 2022; (46):199–208.

- 19.Kovalchuk V, Prylepa I, Chubrei O, Marynchenko I, Opanasenko V, Marynchenko Y. Development of emotional intelligence of future teachers of professional training. Int J Early Child Special Educ 2022;14(1).

- 20.Farmus L, Beribisky N, Martinez Gutierrez N, Alter U, Panzarella E, Cribbie RA. Effect size reporting and interpretation in social personality research. Curr Psychol. 2023;42(18):15752–62. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Álvarez-Nieto C, Richardson J, Navarro-Perán M Á, Tutticci N, Huss N, Elf M,… López-Medina IM. Nursing students’ attitudes towards climate change and sustainability: A cross-sectional multisite study. Nurse Education Today, 2022:108, 105185. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Butterfield P, Leffers J, Vásquez MD. Nursing’s pivotal role in global climate action. BMJ, 2021; 373.

- 23.Acar F. Duygusal Zekâ ve liderlik. Erciyes Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Dergisi. 2002;12:53–68. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Turgut MF, Baykul Y. Eğitimde Ölçme ve Değerlendirme. 9. Baskı. Ankara: Pegem Yayıncılık. 2021.

- 25.Atılgan H, Kan A, Doğan N. Eğitimde Ölçme ve Değerlendirme. 12. Baskı. Ankara: Anı Yayıncılık. 2020.

- 26.Demirel Ö. Eğitimde program Geliştirme Kuramdan Uygulamaya. 29 ed. Baskı. Ankara: Pegem Akademi. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Şeker H. Eğitimde program Geliştirme Kavramlar yaklaşımlar. 5. Baskı. Ankara: Anı Yayıncılık; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Honkavuo L. Educating nursing Students-Emotional intelligence and the didactics of caring science. Int J Caring Sci 2019;12(1).

- 29.Gilar-Corbi R, Pozo-Rico T, Sánchez B, Castejón JL. Can emotional intelligence be improved? A randomized experimental study of a business-oriented EI training program for senior managers. PLoS ONE, 2019; 14(10), e0224254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Erdil F, Başer M, Kaya H, Özer N, Duygulu S, Orgun F. Hemşirelik Ulusal Çekirdek Eğitim Programı (HUÇEP). Ankara, Yükseköğretim Kurulu. 2022. Available from: https://www.hemed.org.tr/2022-hucep/ (cited at: 01.04.23).

- 31.WHO-Nurse Educator Core Competencies Report (NECCR). (2016). Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/nurse-educator-core-competencies (cited at: 01.04.22).

- 32.HEPDAK. Hemşirelik Eğitim Programları Değerlendirme ve Akreditasyon Derneği-Özdeğerlendirme Raporu Hazırlama Kılavuzu. 2021. Available from: https://www.hepdak.org.tr/doc/b4_v5_1.pdf (cited at: 10.10.2021).

- 33.Baltaş Z. İnsanın Dünyasını Aydınlatan ve Işine Yansıyan işık: duygusal Zekâ. 8 ed. İstanbul: Remzi Kitabevi; 2022. pp. Bask–. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fletcher I, Leadbetter P, Curran A, O’Sullivan H. A pilot study assessing emotional intelligence training and communication skills with 3rd year medical students. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;76:376–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sharif F, Rezaie S, Keshavarzi S, Mansoori P, Ghadakpoor S. Teaching emotional intelligence to intensive care unit nurses and their general health: a randomized clinical trial. Int J Occup Environ Med (The IJOEM). 2013;4(3):141–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shahbazi S, Heidari M, Sureshjani EH, Rezaei P. Effects of problem-solving skill training on emotional intelligence of nursing students: an experimental study. J Educ Health Promotion. 2018;7(156):1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Beauvais A, Atli Özbaş A, Wheeler K. End-of-life psychodrama: Influencing nursing students’ communication skills, attitudes, emotional intelligence and self-reflection. J Psychiatric Nurs, 2019; 10(2).

- 38.Goudarzian AH, Nesami MB, Sedghi P, Gholami M, Faraji M, Hatkehlouei MB. The effect of self-care education on emotional intelligence of Iranian nursing students: A quasi-experimental study. J Relig Health. 2019;58:589–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mostafa NHMMS, Hossein JS, Saeed E. The effect of teaching uning a blend of collaborative and mastery of learning models, on learning of vital signs: An experiment on nursing and operation room students of Mashhad university of medical sciences. Iranian Journal of Medical Education. 2011;11(5 (34)):541–553. Available from: https://sid.ir/paper/59397/en

- 40.Erden M, Akman Y. Eğitim psikolojisi. 21.Basım. Alkım Yayınevi. 2014.

- 41.Koçyiğit M. Etkili İletişim ve Duygusal Zekâ. Eğitim Kitabevi. 4. Baskı. Konya. 2021.

- 42.Erdoğan İ. Sınıf Yönetimi. 21. Basım. İstanbul: Alfa Basım Yayın Dağıtım. 2019.

- 43.Moreno JL. Psikodrama Temel Metinler. Çev: Özbay, G. İstanbul: Avangard Yayınları. 2017.

- 44.Şener Ö. Psikodramanın Sosyal Kaygısı Olan Üniversite öğrencileri Üzerindeki Pozitif etkisi. 6. Türkiye Lisansüstü Çalışmaları Kongresi - Bildiriler Kitabı-III, 2017. 151–60.

- 45.Yuan Y, Geng G, Sun Q. Promotion of the development of independence of undergraduate nursing students by cooperative learning. J Nurs Sci, 2006; 22.

- 46.Fino E, Di Campli S, Patrignani G, Mazzetti M. Professional framing and emotional stability modulate facial appearance biases in nursing students. Japan J Nurs Sci. 2020;17(e12351):1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Reljić NM, Pajnkihar M, Fekonja Z. Self-reflection during first clinical practice: the experiences of nursing students. Nurse Educ Today. 2019;72:61–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Han JR. The mediated effects of Self-regulation in the relationship between nursing professionalism and social responsibility of the nursing students. J Digit Convergence. 2022;20(1):437–43. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tyer-Viola L, Nicholas PK, Corless IB, Barry DM, Hoyt P, Fitzpatrick JJ, Davis S. M. Social responsibility of nursing: A global perspective. Policy Politics Nurs Pract. 2009;10(2):110–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Namdar H, Sahebihagh M, Ebrahimi H, Rahmani A. Assessing emotional intelligence and its relationship with demographic factors of nursing students. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res. 2009;13(4):145–9. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Koç GG. Bilişsel esneklik ve psikolojik dayanıklılık ile stresle başa çıkma arasındaki ilişkinin incelenmesi (Master’s thesis, Sakarya Üniversitesi).2020.

- 52.Hirani SAA, Richter S, Salami BO. Realism and relativism in the development of nursing as a discipline. Adv Nurs Sci. 2018;41(2):137–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Abdollahi A, Abu Talib M, Carlbring P, Harvey R, Yaacob SN, Ismail Z. Problem-solving skills and perceived stress among undergraduate students: the moderating role of hardiness. J Health Psychol. 2018;23(10):1321–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhao FF, Lei XL, He W, Gu YH, Li DW. The study of perceived stress, coping strategy and self-efficacy of C Hinese undergraduate nursing students in clinical practice. Int J Nurs Pract. 2015;21(4):401–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.