Abstract

P-selectin facilitates human carcinoma metastasis in immunodeficient mice by mediating early interactions of platelets with bloodborne tumor cells via their cell surface mucins, and this process can be blocked by heparin [Borsig, L., Wong, R., Feramisco, J., Nadeau, D. R., Varki, N. M. & Varki, A. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 3352–3357]. Here we show similar findings with a murine adenocarcinoma in syngeneic immunocompetent mice but involving a different P-selectin ligand, possibly a sulfated glycolipid. Thus, metastatic spread can be facilitated by tumor cell selectin ligands other than mucins. Surprisingly, L-selectin expressed on endogenous leukocytes also facilitates metastasis in both the syngeneic and xenogeneic (T and B lymphocyte deficient) systems. PL-selectin double deficient mice show that the two selectins work synergistically. Although heparin can block both P- and L-selectin in vitro, the in vivo effect of a single heparin dose given before tumor cells seems to be completely accounted for by blockade of P-selectin function. Thus, L-selectin on neutrophils, monocytes, and/or NK cells has a role in facilitating metastasis, acting beyond the early time points wherein P-selectin mediates interactions of platelet with tumor cells.

Keywords: cancer‖heparin‖glycolipids‖platelets

Hematogeneous metastasis occurs when tumor cells enter the bloodstream, interact with host blood cells, and eventually colonize a distant tissue. Much evidence indicates that hematogenously disseminating tumor cells interact with platelets and leukocytes, forming microemboli that facilitate their arrest in the vasculature (1–4). Although the contribution of platelets to metastasis has been confirmed in several experimental settings (1, 2, 5–10), the mechanisms and significance of leukocyte participation in tumor microemboli remain largely unknown.

Altered cell surface glycosylation is a prominent feature of tumor cells (11–15). In particular, the expression of sialylated fucosylated glycans like sialyl Lewisx/a correlate with a poor prognosis because of tumor progression and a high rate of metastasis (for examples, see refs. 16–18). Selectins are vascular cell adhesion molecules that recognize certain sialyl Lewisx/a carrying mucin-type glycoproteins found on normal leukocytes and endothelium (11, 19–23). Carcinoma cell surface molecules carrying sialyl Lewisx/a also can be recognized by all three selectins (11–15, 17, 24–27), mediating tumor cell interactions with platelets, leukocytes, and endothelium in vitro (10, 25, 27, 28). Based on such data, an in vivo role for E- and P-selectins in metastatic spread has been suggested. The hypothesis that E-selectin on activated endothelium might facilitate cancer cell seeding (14, 29) is supported by transgenic over-expression of E-selectin in the mouse liver, which redirected metastases to this organ (30), and a system where tumor cell expression of sialylated fucosylated glycans was increased by transfecting a fucosyltransferase (31). Carcinoma lines expressing E-selectin ligands also displayed an increased metastatic capacity in cytokine-pretreated mice (32). However, E-selectin is not constitutively expressed in vivo but must be transcriptionally activated by certain stimuli. We have previously shown that platelets adhere to some human carcinoma cells mostly via P-selectin and that inhibition of this interaction leads to attenuation of metastasis in vivo (7, 9). In addition, platelet adhesion to tumor cells physically interferes with access of leukocytes to tumor cells, suggesting a possible shielding effect (8, 9).

L-selectin is constitutively expressed on all neutrophils and monocytes, and on subsets of bloodborne T cells, B cells, and natural killer (NK) cells (19, 22, 23, 33, 34) It is well known to facilitate leukocyte rolling along the vessel wall, which is one of the earliest cellular responses to inflammatory stimuli or tissue damage (19, 22, 23, 35, 36). L-selectin is also required for efficient recirculation of normal lymphocytes into lymph nodes. Transgenic ectopic expression of L-selectin in a spontaneous mouse carcinoma model facilitated lymph node metastasis (37). However, naturally occurring L-selectin on a B cell lymphoma cell line was not associated with enhanced lymph node metastasis (38). Regardless, in contrast to P- and E-selectin, there has been no documented role for normal leukocyte L-selectin in facilitating the metastasis of adenocarcinomas.

Most physiological L-selectin and P-selectin ligands are sialylated fucosylated glycans on mucins, with a requirement for sulfation on tyrosine residues, or on lactosamine units (20–22). Both L-selectin and P-selectin also can bind to sulfatides (3-O-sulfated galactosylceramides; refs. 39–43). The glycosaminoglycan heparin, which is clinically used as an anticoagulant, is known to inhibit tumor growth and metastasis (44–48). Heparin also is a potent inhibitor of P- and L-selectin (49, 50). Indeed, a single injection of heparin given just before tumor cells significantly reduces metastasis, at least partly via inhibition of P-selectin-mediated platelet–tumor cell interaction (9). Here we implicate L-selectin in facilitating metastasis, show that it is synergistic with P-selectin, and explore the relative effects of heparin on the contributions of the two selectins.

Materials and Methods

Immunodeficient Mouse Models.

Rag2−/− immunodeficient mice in a 129S6 genetic background (129S6/SvEvTac-Rag2tm1) were from Taconic Farms. L-selectin-deficient mice (here referred to as L−/−) in a B6,129S background (B6;129S-Selltm1Hyn) from The Jackson Laboratory were originally deposited by one of us (R.O.H.). L-selectin:Rag2 double-null mice as well as Rag2−/− littermate controls (L+/+) were bred and characterized as follows: PCR genotyping of the Rag2 mutant was as described previously (7); PCR screening for L-sel wild-type (wt) allele was conducted with L-sel-729 GGGAGCCCAACAACAAGAAG and L-sel-730 ACACTGGACCACATACTGACACTG primers; and PCR screening for the L-sel mutant allele was performed with primers L-sel-730 and NeoB CACGAGACTAGTGAGACGTG in PCR reactions at annealing temperature of 59°C. Eight-week-old mice were injected i.v. with 3–4 × 105 cells of LS180 human tumor cells. After 6 weeks, lung metastases were detected by histology and by PCR amplification of human Alu sequences exactly as previously described (7, 9). In brief, amplified Alu sequences were blotted, probed with an oligonucleotide corresponding to a consensus Alu sequence (nonoverlapping with the original PCR primers), and quantified by a PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics).

Flow Cytometry Analysis of MC-38 Cells.

The mouse colon adenocarcinoma cell line MC-38 was a kind gift from J. Schlom, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD. Chimeras of mouse selectins (P-, L-, and E-) fused with the Fc region of human IgG (a kind gift from J. B. Lowe) were used for probing tumor cells for selectin ligands. Cells were detached from plates by incubation with PBS containing 2 mM EDTA for 5 min at 37°C and washed three times with Hanks' balanced salt solution (HBSS) before blocking nonspecific sites with 0.5% BSA in HBSS. Mouse selectin chimeras were preincubated with a goat-anti-human IgG Ab conjugated with PE for 1 h at room temperature (rt) before incubation of the mixture with tumor cells. After a 2-h incubation at 4°C, cells were washed with HBSS/BSA and HBSS, followed by fixation with 2% (wt/vol) paraformaldehyde in HBSS. Cells were washed again with HBSS and resuspended in HBSS/BSA for flow cytometry. Controls were stained in a presence of 5 mM EDTA (calcium chelation) and also 30 mM EDTA in the case of P-selectin (49). In some instances, tumor cell surfaces were pretreated before probing for selectin ligands. Selective removal of sialylated mucins was done by treatment with O-sialoglycoprotease (Cedarlane Laboratories) in HBSS for 1 h at 37°C with occasional mixing. Removal of sialic acids was by treatment with Arthrobacter ureafaciens sialidase (Sigma) in Hepes buffer (pH 6.9) for 1 h at 37°C. Removal of glycosaminoglycans was by treatment with a mixture of heparanase II and chondroitinase ABC (Sigma) in HBSS buffer for 1 h at 37°C.

ELISA Analysis of Lipids from MC-38 Cells.

Cells (2 × 108) were detached by trypsin treatment in presence of EDTA and washed three times with PBS. The cell pellet was resuspended in chloroform:methanol mixture 1:1 and sonicated three times for 1 min. Lipids were extracted for 1 h at rt while shaking. Insoluble proteins were spun down in two rounds of centrifugations at 4°C. The supernatant containing lipids was dried and stored at 4°C. For lipid ELISA (51), the extracts were resuspended in methanol and 20-μl coated onto wells of ELISA plates (Nunc, catalog no. 269620). As a control 200 ng of bovine sulfatide (Matreya, Pleasant Gap, PA) were used. After evaporation and lipid absorption, some wells were treated with 5 units of arylsulfatase type V from Limpets (Sigma, catalog no. S8629) in acetate buffer, pH 5.0, for 90 min at 37°C with occasional shaking. Plates were blocked with HBSS/0.5% BSA for 30 min. Mouse selectin chimeras were preincubated with secondary goat–anti-human IgG Ab conjugated with alkaline phosphatase (Bio-Rad) for 1 h at rt. Preincubated selectins were added to plates and incubated for 2 h in the absence or presence of 5 mM EDTA at rt, followed by washing with HBSS three times. After a final wash, p-nitrophenyl phosphate liquid substrate (Sigma) was added and incubated at rt for 5 min, and absorbance was measured at 405 nm.

Preparation of MC-38-Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) Cells.

MC-38 murine colon adenocarcinoma cells were transfected with linearized pEGFP-N1 (CLONTECH) by using lipofectamine as per the manufacturer's instructions, followed by selection with G418 (1 mg/ml). Cells underwent two rounds of bulk sorting for GFP fluorescence (1,000 cells each) before a final sorting for 10 cells/pool. Several 10-cell pools were expanded and analyzed for GFP fluorescence and presence of selectin ligands (data not shown). One pool (designed as A2) that had high GFP fluorescence and unchanged levels of selectin ligands was used in all subsequent experiments.

Experimental Metastasis in Syngeneic Mice.

P-selectin-deficient mice (P−/−) in a C57BL6 background and control wt C57BL6 mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory. L-selectin-deficient mice (L−/−) from The Jackson Laboratory were backcrossed for at least seven generations into a C57BL6 background. PL-selectin double-deficient (PL−/−) mice (52) also were backcrossed for at least seven generations into a C57BL6 background. Selectin wt littermates from the same backcrosses were used as controls for experiments with L−/− and PL−/− mice. Mice (7–10 weeks old) were injected i.v. with 3 × 105 MC-38-GFP tumor cells via the tail vein. Some mice also were injected with 100 units of heparin [sodium heparin 20,000 USP units/ml (lot no. 382173) from Fujisawa, Deerfield, IL] or with PBS, 10 min before tumor cell injection. After 22 days, mice were anesthetized with metofane and perfused with PBS. A picture of dissected lungs was taken, and lungs were further processed for quantitation of metastasis by detection of GFP fluorescence. Perfused lungs were homogenized in 2 ml of a hypotonic buffer (20 mM Tris⋅Cl, pH 7.0) by using a Polytron (Brinkhan). Triton X-100 was added to a final concentration of 0.5%. After 30 min on ice, the insoluble debris was spun down (10,000 × g for 10 min), 10 μl of each supernatant diluted with Tris⋅Cl buffer (20 mM, pH 7.0) to a final volume of 100 μl, and transferred to a Quartz ELISA plate. Fluorescence was read on a Cytofluor II microplate reader at Ex = 485 and Em = 508. Background levels for subtraction were determined on lungs from mice, which had not been injected with GFP-labeled cells.

Results

L-Selectin Deficiency Attenuates Metastasis.

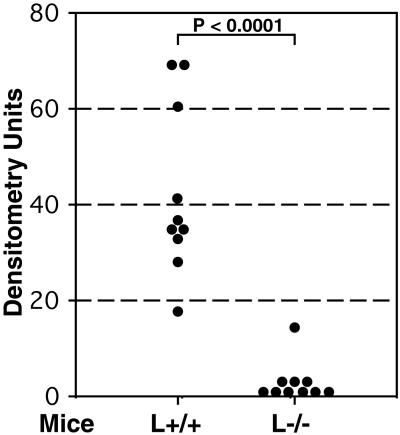

We first studied experimental metastasis of human tumor cells in immunodeficient (Rag2−/−) L-selectin-deficient (L−/−) mice, the approach we previously used to study P-selectin-deficiency (7, 9). Human colon adenocarcinoma LS180 cells (American Type Culture Collection, CL 187), shown previously to express functional L-selectin ligands (25, 27), were injected i.v. into mice, which were studied 6 weeks later. Although metastatic foci were seen histologically in control mice (L+/+), they were not detected in L−/− mice (data not shown). For a more sensitive and precise quantification of metastasis, we used PCR amplification of human-specific Alu sequences in the genomic DNA isolated from the remaining one-half of each dissected lung (7, 53). Fig. 1 presents a composite of two independent experiments, showing a significant reduction of metastasis in L−/− mice. Signals just at the level of detection were observed in six of the 10 L−/− mice. In contrast, all control mice (L+/+) had measurable levels of metastasis. Because Rag2−/− mice are deficient in T and B lymphocytes, these results indicate a significant role for L-selectin expressed on endogenous neutrophils, monocytes, or NK cells in facilitating metastasis in this system.

Figure 1.

L-selectin deficiency attenuates metastasis of human adenocarcinoma cells in immunodeficient mice. Mice were injected i.v. with 3–4 × 105 LS180 cells and studied 6 weeks later. Human-specific Alu-PCR was conducted on genomic DNA isolated from dissected lungs and densitometrically quantified as described in Materials and Methods. The number of animals studied were 9–10 in each group. Statistical significance was determined by the Student's t test.

Mouse Colon Adenocarcinoma Cell Line MC-38 Expresses L- and P-Selectin Ligands.

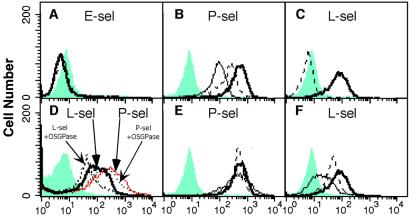

We had previously reported attenuation of metastasis in P−/− mice by using the above mentioned xenogeneic system (7, 9). To exclude the possibility that our results were an artifact of the system used, and to investigate further the role of L-selectin and P-selectin in metastasis, we next established a syngeneic immunocompetent mouse model system. The mouse colon adenocarcinoma cell line MC-38, which is syngeneic to the C57BL6 mouse strain (54), was used for metastasis assays in L−/− or P−/− mice in a C57BL6 background. Also, the tumor cells were tagged with enhanced GFP, allowing easy detection and quantitation of metastasis. First, we evaluated whether these cells express selectin ligands and would be suitable for our studies. Cell surfaces were analyzed by flow cytometry using recombinant mouse selectin probes. As shown in Fig. 2 A–C, the P- and L-selectin probes bound to MC-38 cells, but no binding of E-selectin was detected. Binding of L-selectin was calcium-dependent (blocked by EDTA), whereas P-selectin binding was only partially inhibited, even with higher concentrations of EDTA. This is typical of P-selectin interactions with some sulfated ligands (49).

Figure 2.

Characterization of selectin ligands on MC-38 mouse adenocarcinoma cells by flow cytometry. MC-38 cells were probed with recombinant mouse selectins and studied by flow cytometry as described in Materials and Methods. The gray areas represent control profiles with secondary Ab only. (A--C) Bold solid line represents selectin-stained cells (selectin as indicated); dashed line represents selectin staining in presence of 5 mM EDTA, and thin line represents selectin staining in presence of 30 mM EDTA. (D) L- and P-selectin staining of cells after O-sialoglycoprotease treatment as indicated. (E and F) Bold solid line represents selectin-stained cells (selectin as indicated); dashed line represents selectin-stained cells after heparinase plus chondroitinase treatment, and thin solid line represents selectin-stained cells after sialidase treatment.

Some of the Tumor Cell Selectin Ligands Are Not Mucins.

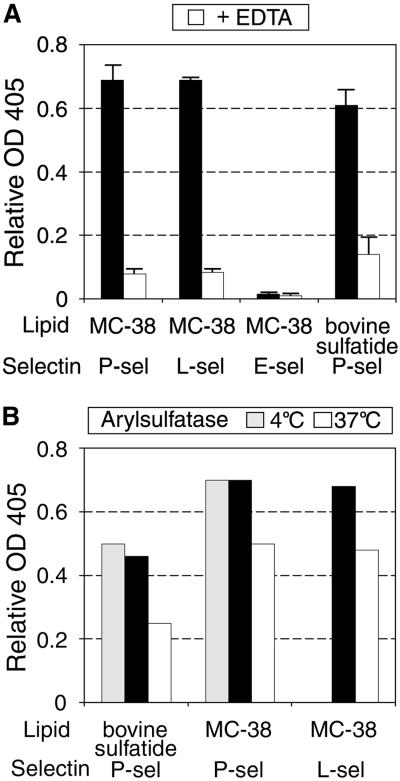

Because our previously reported tumor-associated selectin ligands were mucins carrying sialylated, fucosylated epitopes (27), we checked for the presence of similar molecules on MC-38 cells, by treatment with O-sialoglycoprotease, an enzyme which specifically cleaves sialylated mucins (Fig. 2D). This treatment partially reduced binding of L-selectin to the cells, but P-selectin binding remained unaffected. Removal of sialic acid by sialidase reduced binding of L-selectin but again, had no effect on P-selectin binding (Fig. 2E). The partial effects of sialidase and O-sialoglycoprotease treatment indicate that the L-selectin-binding sites are at least in part presented by sialylated mucins. Because there appeared to be no mucin-type ligands for P-selectin, we checked for other potential P-selectin ligands such as glycosaminoglycans (e.g., heparan sulfate; refs. 49 and 50) and sulfatides (3-sulfated galactosylceramides; refs. 39–41). Treatment with a mixture of glycosaminoglycan-cleaving enzymes heparinase and chondroitinase gave no decrease in P-selectin binding. In contrast, there was a clear decrease of L-selectin binding (Fig. 2 E–F). To test for the presence of sulfatides, glycolipids were extracted and examined by an ELISA assay for selectin ligand activity. As shown in Fig. 3A, P-selectin-Fc strongly bound to the tumor lipid fraction in an EDTA-dependent manner, suggesting that glycolipid ligands are the functional P-selectin-binding sites. Bovine sulfatide was used as a positive control. In keeping with the previous observations, the binding of E-selectin to sulfatide was poor, and the same was true with the tumor lipid extract (41). To examine further the possibility that the lipid selectin ligand is a sulfatide, we used arylsulfatase treatment for removal of sulfate groups (Fig. 3B). This reduced binding of P- and L-selectin by 30%, as compared to 45% reduction of binding to bovine sulfatide. Controls using the enzyme at 4°C showed no effect on selectin binding. Complete removal of P-selectin binding was not achieved even in the sulfatide control, possibly because of limitations of enzyme action on the coated ELISA plates. Thus, the partial decrease in binding to MC-38 lipid extracts suggests that most or all of the P-selectin ligand activity is comprised of sulfated glycolipids, possibly sulfatides. L-selectin-Fc also bound to the tumor lipid extracts, in agreement with previous knowledge that sulfatides also are recognized by L-selectin (42, 55). The presence of the additional sulfated glycolipid ligand also explains the incomplete L-selectin ligand removal by either O-sialoglycoprotease or heparinase-chondroitinase. In summary, the P-selectin ligand on MC-38 cells is represented mostly or completely of sulfated glycolipids (possibly sulfatides), whereas the L-selectin ligand consists of a mixture of mucins, glycosaminoglycans, and sulfated glycolipids.

Figure 3.

Characterization of selectin ligands in the lipid extracts of MC-38 mouse adenocarcinoma cells. Total lipid extracts of MC-38 cells and control bovine sulfatide were coated onto ELISA plates and probed with selectins as described in Materials and Methods. (A) Selectins were incubated in absence (black bars) or presence (white bars) of 5 mM EDTA. Data shown are mean ± SD of triplicates (B) Treatment of lipid-coated ELISA with arylsulfatase before addition of P- and L-selectin as described in Materials and Methods. Wells coated with bovine sulfatide were used as a positive control. Solid bars represent selectin only; white bars represent selectin binding after arylsulfatase treatment at 37°C, and gray bars represent selectin binding after arylsulfatase treatment at 4°C. Data from one of three representative experiments is presented.

L-and P-Selectin Deficiency Attenuates Metastasis of MC-38 Cells.

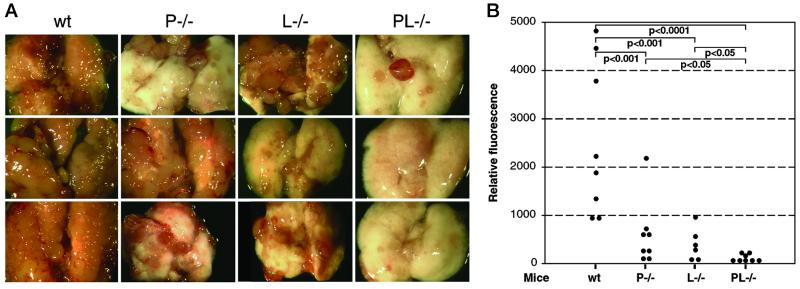

We injected GFP-tagged MC-38 cells i.v. into L−/− and P−/− or wt C57BL mice, killed them 22 days later, and analyzed the extent of metastasis. Dissected lungs were photographed (Fig. 4A) and metastasis quantified by measurement of GFP fluorescence in lung homogenates. Fig. 4 presents data from two independent experiments. The lungs of control wt mice were almost completely displaced by metastasis (Fig. 4A), and correspondingly high fluorescence measurements were obtained (Fig. 4B). A significant reduction was observed in L−/− mice, as well as in P−/− mice. The latter is in agreement with our previously published results, showing platelet P-selectin involvement in metastasis progression (7, 9). These data also indicate that non-mucin P-selectin ligands on tumor cells can play a role in metastasis. Histological evaluation showed a reduction of tumor cell-platelet aggregates in the setting of P-selectin deficiency but not in L-selectin deficiency (data not shown).

Figure 4.

Effect of selectin deficiencies on the metastatic progression of MC-38 mouse adenocarcinoma cells. Mice were injected i.v. with 2–3 × 105 MC-38-GFP cells and examined 22 days later. Lungs were dissected, photographed, and homogenized, and the homogenate was diluted for a fluorescence read-out. (A) Examples of dissected lungs from each mouse genotype. (B) Quantitation of metastasis by GFP fluorescence. All mice were in a syngeneic C57BL6 background. The number of animals studied were six to eight per group. Statistical significance was determined by the Bonferonni multiple compare test.

L-and P-Selectin Act Synergistically.

To ascertain whether the roles of P- and L-selectins are independent, we also injected PL−/− mice with MC-38-GFP-tagged cells. The combined deficiency further attenuated metastatic spread, with only few metastatic foci being observed (Fig. 4A). Quantitation of metastatic spread yielded five of eight measurements just at the level of detection i.e., 3 mice had no detectable metastasis (Fig. 4B). This marked reduction of metastasis in PL−/− mice was statistically significant when compared to the less marked effects in P−/− mice (P < 0.05) or L−/− mice (P < 0.05). Thus, P- and L-selectins act synergistically, and their combined deficiency dramatically reduced metastasis of this aggressive tumor, which had virtually displaced the lungs in wt mice.

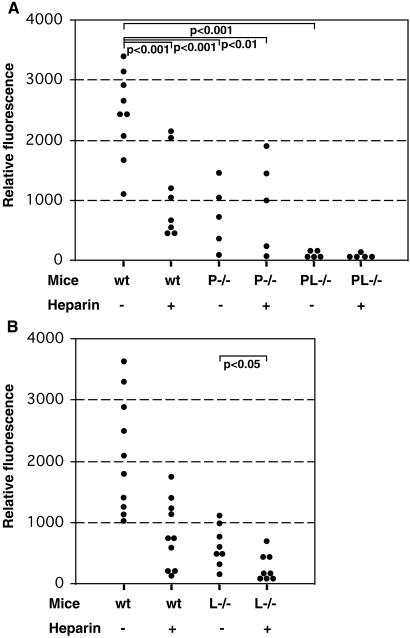

Single-Dose Heparin Attenuates Metastasis Primarily via P-Selectin Inhibition.

We previously showed that a single, 100-unit dose of unfractionated heparin, which peaks in the mouse circulation in 1–2 h and completely disappears in 6–8 h, can significantly reduce metastasis of a human tumor in immunodeficient mice (9). Because heparin is known to be a potent inhibitor of both P- and L-selectin (49, 50), we investigated the possible role of heparin as a blocker of L-and P-selectin-based interactions in this syngeneic system. A single dose of 100 units of heparin was injected into the tail veins of wt and selectin-deficient mice, followed 10 min later by injection of MC-38-GFP cells. Control animals were injected with saline instead of heparin. Mice were killed 22 days later, and the extent of metastasis was quantified. As shown in Fig. 5A, heparin injection in wt mice reduced metastasis to levels similar to those observed in P−/− mice, with or without heparin injection. There was no statistically significant difference between the level of metastasis in wt mice injected with heparin vs. P−/− mice, whether or not the latter were injected with heparin. Thus, P-selectin deficiency and heparin likely act via a common mechanism. Histological evaluation after heparin injection in wt mice showed a diminution of in vivo platelet-tumor cell aggregates (data not shown), indicating a mechanism for heparin action similar to what we reported in the xenogeneic system (9). As before, very low metastasis was detected in PL−/− mice, and no additional effect of heparin could be observed. In contrast, L−/− mice that received heparin showed a further reduction in the incidence of metastasis (Fig. 5B, P < 0.05). Taken together these data suggest that inhibition by single-dose heparin works via mechanisms other than the L-selectin inhibition, primarily P-selectin inhibition. Because a single dose of heparin blocks selectin interactions only for a few hours (9), the role of L-selectin in facilitating metastasis may operate later during the metastatic cascade.

Figure 5.

Effect of heparin on metastatic progression of MC-38 cells in selectin-deficient mice. Mice were i.v. injected with 100 units of heparin or saline 10 min before injection of 2–3 × 105 GFP-expressing MC-38 cells, and studied 22 days later; the lungs were dissected, homogenized, and diluted for quantitation of metastasis by GFP fluorescence. (A) wt = C57BL6 wt mice; P−/− mice in C57BL6 background, and PL−/− mice in C57BL6 background. The number of animals studied were five to eight per group. Statistical significance was determined by the Bonferonni multiple compare test. (B) wt = C57BL wt mice and L−/− mice in C57BL background. The number of animals studied were 8–10 per group. Statistical significance was determined by Student's t test.

Discussion

Hematogeneous metastasis is known to be facilitated by formation of tumor cell-platelet-leukocyte microemboli. However, the molecular mechanisms involved in these interactions have remained poorly understood. The finding that vascular selectins recognize oligosaccharide structures, such as SLex and SLea, on tumor cells in vitro suggested that these endogenous lectins might interact with carcinoma cells in vivo. Given the expected roles of platelets and endothelium in the metastatic process, E- and P-selectin have been previously investigated with respect to their potential role in metastasis. The over-expression of E-selectin (30) or an increase in E-selectin ligands (31) leads to augmented metastasis. We have shown that P-selectin deficiency attenuates metastasis of human carcinoma cells in immunodeficient mice, and our data particularly implicated platelet P-selectin in this process (7, 9, 10).

Here we provide the first evidence that L-selectin, which is endogeneously expressed on leukocytes, also can affect the in vivo behavior of tumor cells. We show that L-selectin deficiency attenuates metastasis by some unknown mechanisms that seem to operate beyond the time point where platelet P-selectin enhances metastatic spread. L-selectin deficiency attenuated metastasis both in the xenogenic system involving immunodeficient mice and in a syngeneic system by using immunocompetent animals. Metastasis was further reduced in PL−/− mice, indicating synergistic roles of P- and L-selectins. Thus, each of these selectins has a distinct role in metastasis. Analysis of tumor cells in the lung vasculature revealed apparently unchanged aggregation of platelets around tumor cells in L−/− mice (data not shown), suggesting that L-selectin is not required for the initial platelet adhesion to tumor cells.

Because the immunodeficient Rag2−/− mice used do not have mature T and B cells, other L-selectin-expressing cells (neutrophils, monocytes, and/or subsets of NK cells) must be involved in supporting metastatic spread. L-selectin has a key role in the accumulation and activation of neutrophils and monocytes at sites of inflammation (22, 23, 56, 57). Activation of rolling neutrophils is accompanied by shedding of soluble L-selectin, which modulates the extent of neutrophil–endothelial interactions (58–60). Partial deletion of the intracellular domain of L-selectin prevents leukocyte rolling without affecting ligand recognition, implying that binding of L-selectin to its ligand is not sufficient for leukocyte rolling (61). Apart from cell adhesion, L-selectin is also known to be a transmembrane-signaling molecule (62, 63). Several reports indicate that the triggering of L-selectin either by ligand binding or by crosslinking leads to activation of a Ras pathway, induction of the respiratory burst and O2− generation (62, 64). Crosslinking of L-selectin on neutrophils leads to phosphorylation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase, which effects neutrophil shape change, integrin activation, and release of secretory granules (65). Recent studies (59) suggest that L-selectin-mediated signaling activates rolling of leukocytes and promotes their arrest if other costimulatory factors on the endothelium, such as chemokines, are present. Based on such knowledge, certain possibilities for L-selectin involvement in metastasis can be envisaged. Because carcinoma cells interact closely with platelets and such emboli are trapped in the microvasculature, the direct interaction of L-selectin-bearing leukocytes with tumor cells seems to be unlikely (7–9). Hence, it is tempting to speculate that it is L-selectin-mediated signaling, accompanied by activation of leukocytes, that mediates the contribution of this molecule in facilitating metastasis. Indeed, engagement of neutrophil L-selectin has been shown to induce increased expression of TNF-α and IL-8 (55). A role for L-selectin in monocyte activation by tumor cells also has been suggested (66). Release of cytokines in the microenvironment of tumor emboli might be crucial for tumor cell survival and/or be a contributing factor for their subsequent extravasation into tissues. In addition, recent studies in an in vivo model of acute inflammation have shown that L-selectin can modulate events downstream of leukocyte rolling and adhesion (67) potentially facilitating tumor cell extravasation. A related possibility is that L-selectin-positive leukocytes interacting with endothelium might simultaneously interact with the outer regions of platelet-tumor cell emboli (via platelet P-selectin and leukocyte PSGL-1), thus “leading the way” for the passage of the tumor cells through the endothelial barrier. In this scenario it would be the endogeneous L-selectin ligands on the endothelium that would be relevant. This would require that L-selectin ligands appear on endothelial cells other than those of lymphoid organs. In fact, it is known that L-selectin ligands can be induced on the endothelium during chronic inflammation (23, 68). In this regard, recent data suggest that extravasation phase of hematogenous metastasis may only occur after a period of intravascular proliferation of tumor cells (69). This could provide sufficient time for the proposed endogenous L-selectin ligands to appear.

Heparin is an efficient inhibitor of P-and L-selectin (49). We have previously shown that a single injection of unfractionated heparin given just before the tumor cells significantly reduces metastasis of a human tumor in an immunodeficient mouse (9, 10). Here we use the MC-38 syngeneic system to show that heparin injection reduces metastasis to levels similar to those seen in P−/− mice. No further reduction of metastasis could be observed by combining P-selectin deficiency and heparin, suggesting that both treatments affect the same step in the metastatic cascade. In contrast, such a single dose of heparin led to a further reduction of metastasis in L−/− mice (P < 0.05). Thus, the role of L-selectin seems to be independent of P-selectin and apparently occurs in a time frame beyond that in which a single dose of heparin acts. Further studies will be needed to define the exact timing and modes of L-selectin action in supporting tumor metastasis.

Although most natural selectin ligands are mucin-associated sialyl Lewis X-containing epitopes, sulfatides are also known to be potential ligands of P- and L-selectin (39, 41–43). Sulfatides are 3-sulfated galactosylceramides, which are able to trigger biological responses via P- or L-selectin binding (39, 41, 43). The unusual composition of L-selectin ligands expressed on MC-38 cells includes mucin-like structures, glycosaminoglycan structures, and sulfated glycolipids, possibly sulfatides. In contrast, most or all of the P-selectin ligand activity may be represented by sulfatides (Figs. 2 and 3). Analysis of MC-38-GFP cells in the lung vasculature revealed a very similar aggregation of platelets around tumor cells (data not shown) to that seen previously with the human colon adenocarcinoma cells. This is in line with earlier results indicating the P-selectin-mediated interaction and possibly protective function of platelets (7–9). Thus, we have provided here in vivo evidence that sulfated glycolipids may be functional selectin ligands in metastatic spread.

Acknowledgments

This paper was supported by U.S. Public Health Service Grant R01CA38701 (to A.V.) and a fellowship of the Novartis-Foundation, Basel, Switzerland (to L.B.).

Abbreviations

- P−/−

P-selectin-deficient mice

- L−/−

L-selectin-deficient mice

- PL−/−

PL-selectin double-deficient mice

- HBSS

Hanks' balanced salt solution

- rt

room temperature

- wt

wild-type

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

References

- 1.Karpatkin S, Pearlstein E. Ann Intern Med. 1981;95:636–641. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-95-5-636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gasic G J. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 1984;3:99–114. doi: 10.1007/BF00047657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fidler I J. Cancer Res. 1990;50:6130–6138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Honn K V, Tang D G, Crissman J D. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 1992;11:325–351. doi: 10.1007/BF01307186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tanaka N G, Tohgo A, Ogawa H. Invasion Metastasis. 1986;6:209–224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Karpatkin S, Pearlstein E, Ambrogio C, Coller B S. J Clin Invest. 1988;81:1012–1019. doi: 10.1172/JCI113411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim Y J, Borsig L, Varki N M, Varki A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:9325–9330. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.16.9325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nieswandt B, Hafner M, Echtenacher B, Männel D N. Cancer Res. 1999;59:1295–1300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Borsig L, Wong R, Feramisco J, Nadeau D R, Varki N M, Varki A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:3352–3357. doi: 10.1073/pnas.061615598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Varki, N. M. & Varki, A. (2002) Semin. Thromb. Hemostasis, in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Fukuda M. Cancer Res. 1996;56:2237–2244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hakomori S. Cancer Res. 1996;56:5309–5318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim Y S, Gum J, Brockhausen I. Glycoconjugate J. 1996;13:693–707. doi: 10.1007/BF00702333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kannagi R. Glycoconjugate J. 1997;14:577–584. doi: 10.1023/a:1018532409041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim Y J, Varki A. Glycoconjugate J. 1997;14:569–576. doi: 10.1023/a:1018580324971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nakamori S, Kameyama M, Imaoka S, Furukawa H, Ishikawa O, Sasaki Y, Kabuto T, Iwanaga T, Matsushita Y, Irimura T. Cancer Res. 1993;53:3632–3637. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Takada A, Ohmori K, Yoneda T, Tsuyuoka K, Hasegawa A, Kiso M, Kannagi R. Cancer Res. 1993;53:354–361. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Amado M, Carneiro F, Seixas M, Clausen H, Sobrinho-Simoes M. Gastroenterology. 1998;114:462–470. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70529-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kansas G S. Blood. 1996;88:3259–3287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McEver R P, Cummings R D. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:485–492. doi: 10.1172/JCI119556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Varki A. J Clin Invest. 1997;99:158–162. doi: 10.1172/JCI119142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lowe J B. Kidney Int. 1997;51:1418–1426. doi: 10.1038/ki.1997.194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Girard J P, Springer T A. Immunol Today. 1995;16:449–457. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(95)80023-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stone J P, Wagner D D. J Clin Invest. 1993;92:804–813. doi: 10.1172/JCI116654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mannori G, Crottet P, Cecconi O, Hanasaki K, Aruffo A, Nelson R M, Varki A, Bevilacqua M P. Cancer Res. 1995;55:4425–4431. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pottratz S T, Hall T D, Scribner W M, Jayaram H N, Natarajan V. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:L918–L923. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1996.271.6.L918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim Y J, Borsig L, Han H L, Varki N M, Varki A. Am J Pathol. 1999;155:461–472. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65142-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Izumi Y, Taniuchi Y, Tsuji T, Smith C W, Nakamori S, Fidler I J, Irimura T. Exp Cell Res. 1995;216:215–221. doi: 10.1006/excr.1995.1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sawada R, Tsuboi S, Fukuda M. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:1425–1431. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Biancone L, Araki M, Araki K, Vassalli P, Stamenkovic I. J Exp Med. 1996;183:581–587. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.2.581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ohyama C, Tsuboi S, Fukuda M. EMBO J. 1999;18:1516–1525. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.6.1516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mannori G, Santoro D, Carter L, Corless C, Nelson R M, Bevilacqua M P. Am J Pathol. 1997;151:233–243. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Luscinskas F W, Kansas G S, Ding H, Pizcueta P, Schleiffenbaum B E, Tedder T F, Gimbrone M A., Jr J Cell Biol. 1994;125:1417–1427. doi: 10.1083/jcb.125.6.1417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tang M L K, Steeber D A, Zhang X Q, Tedder T F. J Immunol. 1998;160:5113–5121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Butcher E C. Cell. 1991;67:1033–1036. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90279-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ley K, Tedder T F. J Immunol. 1995;155:525–528. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Qian F, Hanahan D, Weissman I L. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:3976–3981. doi: 10.1073/pnas.061633698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Aviram R, Raz N, Kukulansky T, Hollander N. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2001;50:61–68. doi: 10.1007/PL00006682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Aruffo A, Kolanus W, Walz G, Fredman P, Seed B. Cell. 1991;67:35–44. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90570-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bajorath J, Hollenbaugh D, King G, Harte W, Jr, Eustice D C, Darveau R P, Aruffo A. Biochemistry. 1994;33:1332–1339. doi: 10.1021/bi00172a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mulligan M S, Warner R L, Lowe J B, Smith P L, Suzuki Y, Miyasaka M, Yamaguchi S, Ohta Y, Tsukada Y, Kiso M, et al. Int Immunol. 1998;10:569–575. doi: 10.1093/intimm/10.5.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Alon R, Feizi T, Yuen C-T, Fuhlbrigge R C, Springer T A. J Immunol. 1995;154:5356–5366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Suzuki Y, Toda Y, Tamatani T, Watanabe T, Suzuki T, Nakao T, Murase K, Kiso M, Hasegawa A, Tadano-Aritomi K, et al. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1993;190:426–434. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1993.1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Engelberg H. Cancer. 1999;85:257–272. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19990115)85:2<257::aid-cncr1>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hejna M, Raderer M, Zielinski C C. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91:22–36. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.1.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ornstein D L, Zacharski L R. Haemostasis. 1999;29, Suppl. 1:48–60. doi: 10.1159/000054112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Smorenburg S M, Hettiarachchi R J K, Vink R, Büller H R. Thromb Haemost. 1999;82:1600–1604. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Koliopanos A, Friess H, Kleeff J, Shi X, Liao Q, Pecker I, Vlodavsky I, Zimmermann A, Büchler M W. Cancer Res. 2001;61:4655–4659. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Koenig A, Norgard-Sumnicht K E, Linhardt R, Varki A. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:877–889. doi: 10.1172/JCI1509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xie X, Rivier A S, Zakrzewicz A, Bernimoulin M, Zeng X L, Wessel H P, Schapira M, Spertini O. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:30718–30711. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001257200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Manzi A E, Sjoberg E R, Diaz S, Varki A. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:13091–13103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Robinson S D, Frenette P S, Rayburn H, Cummiskey M, Ullman-Culleré M, Wagner D D, Hynes R O. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:11452–11457. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.20.11452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.McKenzie B A, Barrieux A, Varki N M. Cancer Commun. 1991;3:15–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tan M H, Holyoke E D, Goldrosen M H. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1976;56:871–873. doi: 10.1093/jnci/56.4.871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Laudanna C, Constantin G, Baron P, Scarpini E, Scarlato G, Cabrini G, Dechecchi C, Rossi F, Cassatella M A, Berton G. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:4021–4026. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ley K, Bullard D C, Arbonés M L, Bosse R, Vestweber D, Tedder T F, Beaudet A L. J Exp Med. 1995;181:669–675. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.2.669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Eriksson E E, Xie X, Werr J, Thoren P, Lindbom L. J Exp Med. 2001;194:205–217. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.2.205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kishimoto T K, Jutila M A, Berg E L, Butcher E C. Science. 1989;245:1238–1241. doi: 10.1126/science.2551036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hafezi-Moghadam A, Thomas K L, Prorock A J, Huo Y Q, Ley K. J Exp Med. 2001;193:863–872. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.7.863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gerli R, Gresele P, Bistoni O, Paolucci C, Lanfrancone L, Fiorucci S, Muscat C, Costantini V. J Immunol. 2001;166:832–840. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.2.832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kansas G S, Ley K, Munro J M, Tedder T F. J Exp Med. 1993;177:833–838. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.3.833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Waddell T K, Fialkow L, Chan C K, Kishimoto T K, Downey G P. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:15403–15411. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.25.15403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Crockett-Torabi E. J Leukocyte Biol. 1998;63:1–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Brenner B, Gulbins E, Schlottman K, Koppenhoefer U, Busch G L, Walzog B, Steinhausen M, Coggeshall K M, Linderkamp O, Lang F. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:15376–15381. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.26.15376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Smolen J E, Petersen T K, Koch C, O'Keefe S J, Hanlon W A, Seo S, Pearson D, Fossett M C, Simon S I. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:15876–15884. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M906232199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Putz E F, Männel D N. Scand J Immunol. 1996;44:556–564. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.1996.d01-346.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hickey M J, Forster M, Mitchell D, Kaur J, De Caigny C, Kubes P. J Immunol. 2000;165:7164–7170. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.12.7164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Berg E L, Mullowney A T, Andrew D P, Goldberg J E, Butcher E C. Am J Pathol. 1998;152:469–477. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Al-Mehdi A B, Tozawa K, Fisher A B, Shientag L, Lee A, Muschel R J. Nat Med. 2000;6:100–102. doi: 10.1038/71429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]