Abstract

Background

Vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) brings new hope for handling stroke. Our previous study confirmed that VNS could reduce neuronal pyroptosis and improve stroke prognosis. However, how VNS suppresses pyroptosis remains poorly understood. Osteopontin (OPN,SPP1) plays a neuroprotective role. Therefore, this study aims to determine whether vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) inhibits pyroptosis and promotes recovery from cerebral ischemic injury through osteopontin (OPN), and to elucidate the mechanisms by which OPN regulates pyroptosis.

Methods

Acute ischemic stroke (AIS) patients and healthy controls were recruited. The middle cerebral artery ischemia–reperfusion (MCAO/R) model of rats in vivo, the oxygen–glucose deprivation and reperfusion (OGD/R) and lipopolysaccharide (LPS) + adenosine triphosphate (ATP) models of microglia in vitro were established. Gene analysis of GEO public dataset (GSE61616), analysis of proteomics, western blotting, Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) analysis, immunofluorescence staining, ELISA, TTC staining, TUNEL staining, transmission electron microscopy (TEM), scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and neurological function score were used to examinate expressions or concentrations of osteopontin, pyroptosis-related molecules, OPN-ASC interaction, infarct volume, neurological function, cell membrane pore, respectively.

Results

In MCAO/R rats and AIS patients, osteopontin levels were elevated. Intranasally administered recombinant osteopontin (rOPN) and VNS reduced pyroptosis and improved neurological deficits. VNS upregulated osteopontin expression in MCAO/R rats and AIS patients. Small interfering OPN RNA (siOPN) reversed effects of VNS on pyroptosis and outcome of MCAO/R injury in rats. The binding energy of OPN and ASC was -11.7 kcal/mol. LPS + ATP enhanced OPN-ASC interaction, and rOPN interfered with ASC oligomerization. Conditioned medium of microglia treated with rOPN reversed LPS + ATP-induced neruonal injury. Collectively, OPN may serve as a potential mediator through which VNS inhibits pyroptosis and improves the outcome of ischemic stroke, thereby representing a promising therapeutic target for stroke treatment.

Conclusions

These findings suggest that VNS alleviates pyroptosis and improves the outcome of cerebral ischemic stroke by upregulating osteopontin (OPN), which interferes with ASC oligomerization.

Graphical Abstract

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12916-025-04242-4.

Keywords: Ischemic stroke, Vagus nerve stimulation, Osteopontin, Pyroptosis, ASC

Background

Ischemic stroke is a leading cause of global mortality and long-term disability. Despite advances in medical care, treatment options remain limited [1, 2]. Vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) was initially developed for refractory epilepsy and depression [3, 4]. Due to its safety and proven therapeutic potential, VNS has been explored as a treatment for various central nervous system (CNS) disorders, including ischemic stroke [5]. Clinical trials have shown that combining rehabilitation therapy with VNS significantly improves motor function in the affected limbs of stroke patients [6]. In animal models, VNS also confers neuroprotection against ischemia–reperfusion (I/R) injury [5, 7], however, the underlying mechanisms remain poorly understood.

Pyroptosis is an inflammasome-mediated form of programmed cell death characterized by strong inflammatory responses [8, 9]. To date, five major inflammasomes have been identified: NLRP1, NLRP3, NLRC4, IPAF, and AIM2, with NLRP3 being the most extensively studied [10, 11]. Following I/R injury, NLRP3 inflammasome activation leads to pyroptosis and the release of large amounts of proinflammatory cytokines [12, 13]. Inhibiting pyroptosis has been shown to reduce I/R-induced brain injury in animal models [5, 12]. Moreover, recent studies suggest that VNS suppresses pyroptosis and improves outcomes after cerebral ischemia [5]. However, the precise mechanisms by which VNS inhibits pyroptosis remain unclear.

Osteopontin (OPN), a glycoprotein encoded by the SPP1 gene, is widely expressed in various organs [14]. Under physiological conditions, OPN expression in the CNS is low. Following CNS injury such as stroke, traumatic brain injury, or neurodegeneration, OPN expression markedly increases and exerts neuroprotective effects [15–17]. However, whether OPN regulates pyroptosis, and whether VNS modulates pyroptosis via OPN expression after ischemic stroke, remains to be elucidated.

Therefore, the aim of this study is to determine whether VNS inhibits pyroptosis and promotes recovery from cerebral ischemic injury by regulating OPN expression, and to explore how OPN modulates pyroptosis.

Methods

Patients

The study included the following cohorts: (1) Acute ischemic stroke (AIS) patients admitted to the Department of Neurology of the First Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical University from Oct. 1, 2023 to Dec.1, 2023. (2) Patients with acute ischemic stroke (AIS) or traumatic brain injury (TBI) admitted to the Department of Neurosurgery of Mianyang Third People's Hospital from Oct. 1, 2023 to Feb.1, 2024. (3) Patients treated for sequelae of acute ischemic stroke in the Rehabilitation Department of the First Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical University from Oct. 1, 2023 to Dec.1, 2023. (4) Healthy volunteers were selected from people admitted to the Department of Health Management of the First Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical University from Oct. 1 to Dec1, 2023.

Inclusion criteria of AIS involved: (1) Age of 18–85 years old. (2) All patients met the diagnostic criteria of acute cerebral infarction, and had the corresponding head MRI or head and neck CTA evidence consistent with the patient's symptoms.

Exclusion criteria of AIS involved: (1) Severe organic diseases, such as severe heart failure (New York Heart Association class II and IV), severe liver and renal dysfunction, severe thyroid dysfunction, adrenal disease and tumor history. (2) Complicated with other serious neurological diseases, dementia, dystonia, etc. (3) Alcoholics and drug abusers. (4) Pregnant and lactating women. (5) Participating in another trial with an active intervention.

Ultimately, 42 healthy volunteers, 44 AIS patients and 22 AIS patients treated with VNS participated in our study from Oct. 1 to Dec1, 2023. 3 TBI patients requiring surgery and 3 AIS patients requiring surgery participated in our study from Oct. 1, 2023 to Feb.1, 2024. The demographic characteristics of the patients and the healthy controls are presented in Additional file 1: Table S1. Participants were provided with a detailed description of the trial, and provided written informed consent for the publication of patient data.

Animals

To negate hormonal influence on findings [18], adult male Sprague–Dawley (SD) rats (220-250 g) purchased from the Experimental Animal Centre of Chongqing Medical University (license No. SCXK (Yu) 2022–0016) were used for MCAO/R model. All experimental SD rat had free access to food and water throughout the study period and were kept in 12-h light–dark cycle rooms with appropriate temperature and humidity. Neonatal Sprague‒Dawley rats (1 day old) were also purchased from the Department of Animal Laboratory, Chongqing Medical University, Chongqing, China to culture primary neurons and microglial.

In this study, a total of 210 male SD rats were used and assigned to different experimental protocols as follows: (1) Sham group and MCAO/R group (n = 8): used for evaluating the baseline effects of middle cerebral artery occlusion/reperfusion (MCAO/R). (2) rOPN group and PBS group (n = 5): used to verify whether exogenous rOPN administered intranasally can enter the brain and exert biological effects. (3) Sham, MCAO/R, MCAO/R + VNS, and MCAO/R + PBS groups (n = 13): used for evaluating the therapeutic effect of vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) and PBS control following MCAO/R. (4) Sham, MCAO/R, and MCAO/R + VNS groups (n = 11): used to assess the role of VNS in MCAO/R injury without additional pharmacologic intervention. (5) siOPN group and siNC group (n = 3): used to investigate the gene-silencing effect of siRNA targeting osteopontin (OPN). (6) Sham, MCAO/R, MCAO/R + VNS, MCAO/R + VNS + siOPN, and MCAO/R + VNS + siNC groups (n = 18): used to explore the involvement of OPN in mediating VNS-induced neuroprotection.

Experimental rats were randomly distributed into groups, with data acquisition conducted in a blinded manner to maintain researcher objectivity. And the number of animals used per experiment was determined based on power analysis and prior experience. The final number of animals included in statistical analysis is indicated in the corresponding figure legends. All procedures were conducted in accordance with institutional ethical guidelines and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Middle cerebral artery occlusion and reperfusion (MCAO/R) model in rats and VNS treatment

The MCAO/R model is a canonical model for eliciting focal cerebral ischemia in rodent studies [19]. Focal cerebral ischemia was induced via intraluminal middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO), following the technique detailed by Longa et al. [20]. Rats underwent anesthesia with Avertin (concentration: 1.25 mg/mL, dosage: 2 mL/100 g, i.p.) [21] This study adhered to the IMPROVE guidelines [22], with reporting protocols and details conforming to the ARRIVE guidelines [23].

Invasive VNS was performed in SD rats with reference to previous studies [24]. Invasive VNS was performed in Sprague–Dawley (SD) rats (male, 220-250 g). Rats were anesthetized with with Avertin (concentration: 1.25 mg/mL, dosage: 2 mL/100 g, i.p.) and placed in the supine position on a heating pad to maintain body temperature.

A midline cervical incision (~ 2 cm) was made to expose the right cervical vagus nerve, carefully separating it from the carotid artery and surrounding connective tissue under a surgical microscope.

A bipolar VNS cuff electrode (MicroProbes for Life Science, Cat. #CM21, Gaithersburg, MD, USA) was gently wrapped around the nerve without applying compressive force. The leads were tunneled subcutaneously to the dorsal side of the neck, where they were temporarily fixed with sutures. A head mount connector was not used in this study; stimulation was directly delivered via external connection to the stimulator during the experiment.

The stimulation protocol began approximately 30 min after induction of middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO). Electrical stimulation was delivered using a constant-current stimulator (STG4002, Multi Channel Systems, Germany) for one hour, with parameters set to: Pulse duration: 0.5 ms, Amplitude: 0.5 mA, Frequency: 20 Hz. Stimulation cycle: 30 s ON, 5 min OFF. At the end of stimulation, the electrode was carefully removed, the incision sutured, and animals returned to their cages for recovery under close observation. An illustrative image of the implantation setup is provided in Additional file 2: Figure S1.

Oxygen–glucose deprivation and reperfusion (OGD/R) model in vitro

The OGD/R model was established utilizing standardized methodologies that have been used in previous studies [25]. Following medium substitution with D-Hanks solution, cells underwent 150 min of incubation in a hypoxic environment (1% O2, 5% CO2, 94% N2 at 37℃). Afterwards, cells were switched out for complete medium and moved to a normoxic incubator for 24 h.

Intracerebroventricular injection of small interfering RNA (siRNA)

Small interfering RNA targeting osteopontin (siOPN) or scrambled control siRNA(siNC) was administered via intracerebroventricular (ICV) injection. Adult male rats were anesthetized with Avertin (tribromoethanol, i.p.) and placed in a stereotaxic apparatus (RWD Life Science, China). A burr hole was drilled, and 5 μL of siOPN solution (2 μg/μL in RNase-free PBS) was injected into the right lateral ventricle using a Hamilton microsyringe (10 μL) at a rate of 0.5 μL/min.The stereotaxic coordinates relative to the bregma were: anteroposterior (AP): –0.8 mm, mediolateral (ML): + 1.5 mm, dorsoventral (DV): –3.5 mm. The needle was held in place for 5 min after injection to allow diffusion and minimize backflow. Injections were performed at 3 days prior to MCAO/R and again at the time of reperfusion. Animals were returned to their cages and monitored during recovery.The sequences of siOPN and control siRNA are provided in Additional file 1: Table S2.

Western blotting

Proteins were electrotransferred onto PVDF membranes following separation by 8% and 10% SDS-PAGE. Membranes were blocked with 5% skim milk at room temperature for 2 h and incubated overnight at 4℃ with the following primary antibodies: mouse anti-Osteopontin (1:100, Santa Cruz, AKm2A1), rabbit anti-NLRP3 (1:1000, Abcam, ab263899), rabbit anti-GSDMD-N (1:200, Santa Cruz, sc-393656), rabbit anti-ASC (1:200, Santa Cruz, sc-514414), rabbit anti-Cl-Caspase1 (1:1000, Proteintech, 22,915–1-AP), rabbit anti-β-Actin (1:5000, Proteintech, 81,115–1-RR), After TBST washing, The membranes were incubated with the secondary antibody (1:5000) at room temperature for 1 h. After cleaning, the slides were visualized by an enhanced chemiluminescent kit, imaged, and analysed by Fusion software (Vilber Lourmat, France).

Immunofluorescence and TUNEL staining

For paraffin sections of brain tissue, dewaxed at 60 ℃ for 2 h, underwent antigen repair with sodium citrate buffer, when the temperature dropped to room temperature, incubated with 10% goat serum for 1 h at 37℃ to block non-specific binding sites and placed at 4℃ overnight with anti-Osteopontin (1:50, Santa Cruz, AKm2A1), anti-GSDMD-N(1:50, Santa Cruz, sc-393656), anti-Cl-Caspase1 (1:1000, Proteintech, 22,915–1-AP), anti-GFAP (1:100, Proteintech, 60,190–1-Ig), anti-Neun (1:100, Proteintech, 26,975–1-AP), anti-Iba-1(1:100,Abcam, ab178846), anti-NF200 (1:100, CST, 2837 T). Subsequently, samples were incubated with secondary antibodies for 1 h at 37℃, followed by a 15-min treatment with DAPI. Confocal imaging was then performed using a confocal laser microscope (Zeiss, Germany).

Cells were fixed using 4% paraformaldehyde and subsequently blocked with a solution containing 3% BSA and 0.1% Triton X-100. Samples were incubated overnight with primary antibodies specific to ASC (Abcam, ab309497) and MAP2 (ThermoFisher, PA1-10,005) preceded a 1 h incubation with secondary antibodies at 37℃. Nuclear staining was achieved with DAPI for 15 min, and imaging was conducted via confocal microscopy (Zeiss, Germany).

Paraffin sections of brain tissue were dewaxed at 60℃ for 2 h, dewaxed in xylene and gradient alcohol successively. Then, sections were stained with an apoptosis kit according to the instructions (Servicebio, Wuhan, China. Cat. #G1505). The statistical analysis of the TUNEL-positive cell count was conducted using the ImageJ software.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

The concentrations of osteopontin in human serum samples, rat serum samples and rat CSF samples were detected by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (Fine test, Wuhan, China. Cat. # EH0248, Cat. # ER1214). The contents of Interleukin-1β (IL-1β) and Interleukin-18(IL-18) in the infarct brain tissue at 3 days post-induction of ischemia–reperfusion (I/R) injury were detected by ELISA kit (Fine test, Wuhan, China. Cat. # ER1094, Cat. # ER0036).

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

The rats were anesthetized and perfused with 0.1 M phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and 2.5% ice-cold glutaraldehyde, the the infarcted brain samples were sectioned into 1mm3, fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde, then post-fixed in 1% osmium tetroxide. Ultimately, samples were stained using uranyl acetate and lead citrate, then examined via a Hitachi H7500 transmission electron microscope (Tokyo, Japan).

Scanning electron microscope (SEM)

The microglia treated with LPS and ATP were fixed by 2.5% ice-cold glutaraldehyde, and washed by 0.1 M PBS. Subsequently, the cells underwent washes with 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer and dehydration by ethanol. Following dehydration, the samples were subjected to critical point drying (CPD). To ensure conductivity and minimize charging during SEM imaging, the dried samples were coated with a 10 nm-thick layer of gold–palladium using a sputter coater. Ultimately, samples were examined via a JSM-IT700HR scanning electron microscope (SEM) (JEOL, Japan).

Measurement of cerebral infarct volume

After deep anesthesia, rat brains were rapidly removed and frozen at − 20 °C for ~ 25 min, then sectioned into 2 mm slices. The slices were incubated in 2% TTC solution (Solarbio, Cat. #G3005) at 37 °C for 15 min, followed by fixation in 4% paraformaldehyde at 4 °C for 4 h. Infarct areas were quantified from high-resolution images using ImageJ software.

Neurological function evaluation

Neurological function was evaluated at 1 d, 3 d and 7 d after MCAO/R by the modified Neurological Severity Score (mNSS) [26], corner test [27], cylinder test [28], rotarod test [29] and handgrip test [27].

Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP)

Co-IP assay was used to confirm the interactions of proteions. First, cells from Control, OGD/R and LPS + ATP groups were incubated with anti-OPN, anti-ASC, or rat IgG (2 µg) for 20 h at 4 ℃ on a rotator. At the second day, Protein A/G magnetic beads were added to the above lysates and rotated for 2 h at 4℃. After washing, antigens were washed out by 2X SDS elution buffer and boiling for 10 min. The obtained samples were used for Western blotting.

Laser speckle contrast imaging (LSCI)

Cerebral blood flow (CBF) changes post-MCAO were assessed utilizing a Laser Speckle Contrast Imaging (LSCI) system (Peri-Cam PSI System; Perimed) [30]. After deep anesthesia, the rat’s head was secured in a stereotaxic frame (RWD Life Science Co., Ltd, Shenzhen, China), and a midline scalp incision was made to expose the skull. Laser speckle contrast imaging (LSCI) was employed to evaluate and compare cerebral blood flow (CBF) between the MCAO/R and MCAO/R + VNS groups. Regions of interest (ROIs) were defined, and blood perfusion was measured in perfusion units (PUs).

Drug treatment

rOPN (Abcam, ab281819,5 μg/rat) was dissolved in PBS and administered intranasally during middle cerebral artery reperfusion, MCAO/R + vehicle group received the equal volume of PBS. OPN siRNA and scrambled siRNA (Tsingke Biotech, Beijiing) were injected intracerebroventricularly at 72 h before MCAO/R surgery and reperfusion after MCAO.

Cell culture and treatment

The protocols for culturing primary microglial and primary cortical neurons were in the methodology section of the study conducted by Xia and colleagues [25]. Primary microglia were isolated from the cerebral cortices of Neonatal Sprague‒Dawley rats (1 day old). Briefly, meninges were removed, and the cortices were mechanically dissociated and enzymatically digested in 0.25% trypsin–EDTA at 37 °C for 15 min. The suspension was filtered through a 70 μm cell strainer and plated in poly-D-lysine–coated T75 flasks in DMEM/F12 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. After 14 days of mixed glial culture, microglia were detached by gentle shaking (180 rpm, 1 h, 37 °C), collected, and replated for downstream experiments. Microglial purity was confirmed by Iba1 immunostaining (> 95%).

Primary cortical neurons were isolated from the cerebral cortices of Neonatal Sprague–Dawley rats (1 day old). After removal of meninges, cerebral cortices were dissected, minced, and digested with 0.25% trypsin at 37 °C for 15 min. Following gentle trituration, the dissociated cells were filtered through a 40 μm cell strainer and seeded onto poly-D-lysine-coated plates in Neurobasal medium supplemented with 2% B27, 0.5 mM GlutaMAX, and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. Cultures were maintained at 37 °C in a 5% CO₂ incubator. Medium was half-changed every 3 days. Neurons were used for experiments after 7–10 days in vitro, when neuronal morphology was established.

Following purification of microglia, the culture medium was replaced, and cells were pre-treated with 0.5 μg/mL concentration of rOPN (Abcam, ab281819) for 1 h. Thereafter, the cells were exposed to a model comprising lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (100 ng/mL for 5.5 h) and adenosine triphosphate (ATP) (5 mM for 0.5 h). Conditioned medium was subsequently collected after this treatment.

Bioinformatics analysis

We retrieved the transcriptomic data of rat brain tissue post-MCAO/R-induced stroke from the public GEO database (GSE61616). The identification of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) was accomplished through the application of the'limma'package in R, and their functional significance was explored by mapping them with the Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) software (QIAGEN Inc., Valencia, CA, USA). The IPA software was also employed to construct networks of genes and forecast pathways linked to SPP1 expression. Moreover, we collected 3 sham and 3 ischemic brain tissue samples after MCAO/R 3 d in rats for proteomics analysis (BGI, Beijing). The specific steps of bioinformatics analysis were described by Xia et al. [25].

Molecular docking

The protein structure files of OPN and ASC were obtained from the AlphaFold database, and PyMol2.5.32 was used to remove the predicted incorrect structural regions. We used ZDOCK 3.0.21 to perform the molecular docking of OPN and ASC. The model with the highest affinity was created with the PyMol Molecular Graphics System, and was shown in Fig. 7B.

Fig. 7.

Blocking osteopontin eliminates the neuroprotective effect of VNS after MCAO/R. A-B Typical TTC staining images captured at 3 days post-MCAO/R injury, alongside a quantified assessment of the infarcted volume (n = 5), Scale bars = 1 inch. C-G The examination of neurological deficits by mNSS score, corner test,cylinder test, Rotarod test and Handgrip test (n = 5). H Representative immunofluorescence images depicting the expression of NF200 in the Sham, MCAO/R, MCAO/R + VNS, MCAO/R + VNS + siOPN and MCAO/R + VNS + siNC groups, Scale bars = 20 μm. *p < 0.05 vs. the Sham group, #p < 0.05 vs. the MCAO/R group, △p < 0.05 vs. the MCAO/R + VNS group, ▲p < 0.05 vs. the MCAO/R + VNS group

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism version 10.0.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). Data normality was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test. For comparisons between two groups, a two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test was applied. For comparisons involving more than two groups, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed, followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test as the post-hoc analysis. Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Mortality and neurological deficit score

A total of 210 rats were used, of which 50 rats underwent sham surgery, and 160 rats underwent MCAO/R. Of the 160 MCAO/R rats, The neurologic deficit score of 1 to 3 indicates a successful model, while scores of 0 and 4 are excluded [20]. 12 were excluded from this study due to low neurological function score. The overall mortality of MCAO/R rats was 10.81% (16/148). No rats in the sham group died.

Physiological parameters

During the whole experiment, blood pressure, heart rate, blood gas and other physiological parameters of rats in every group were normative, and there was no significant change in these parameters before and after VNS (Table 1).

Table 1.

The physiological parameters of rats during the experiment (all data are shown as the mean ± SD)

| Group | Mean blood pressure (mmHg) | Heat rate (bp/min) |

PH | PCO2 | PO2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sham | 85.60 ± 4.20 | 365.40 ± 7.10 | 7.38 ± 0.01 | 46.90 ± 0.80 | 111.00 ± 8.70 |

| MCAO | 85.00 ± 4.10 | 366.40 ± 6.50 | 7.39 ± 0.03 | 46.50 ± 0.50 | 112.40 ± 10.40 |

| MCAO + VNS | 84.80 ± 6.00 | 364.00 ± 6.40 | 7.39 ± 0.03 | 47.50 ± 0.90 | 111.80 ± 10.50 |

| MCAO + VNS + siOPN | 84.20 ± 5.10 | 366.00 ± 6.30 | 7.39 ± 0.02 | 47.10 ± 1.00 | 109.20 ± 10.10 |

| MCAO + VNS + siNC | 86.40 ± 4.10 | 361.40 ± 4.90 | 7.37 ± 0.03 | 46.90 ± 1.10 | 114.20 ± 8.30 |

Analysis of ischemic stroke-associated DEGs from brain tissue of rats

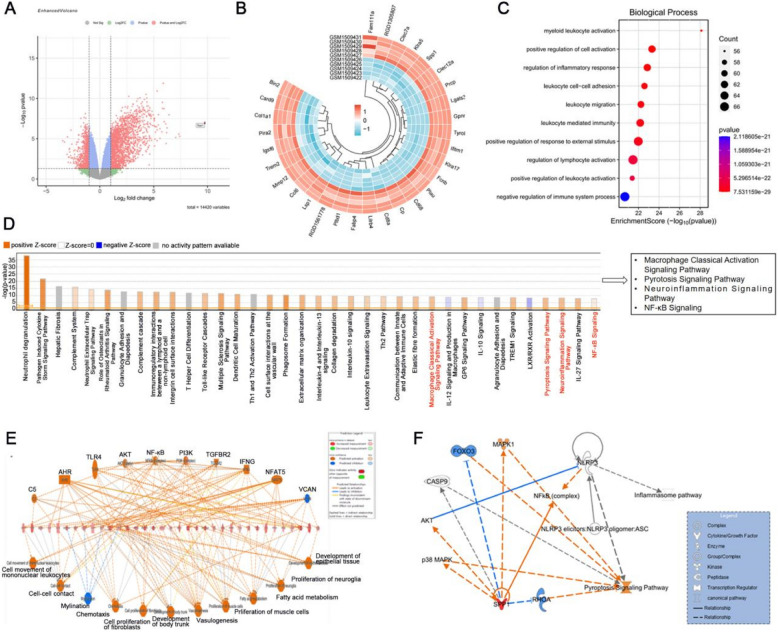

Comparison of expression data between MCAO/R and sham groups from the GEO database (GSE61616) identified 3736 DEGs in MCAO/R group (2456 upregulated and 1280 downregulated). The volcano plot of DEGs between MCAO/R and sham groups is displayed in Fig. 1A. The heat map of the top 30 DEGs between MCAO/R and sham groups is displayed in Fig. 1B. Among the top 10 biological processes for the DEGs between MCAO/R and sham groups were'positive regulation of cell activation'and'regulation of inflammatory response'(Fig. 1C). Moreover, IPA analysis of the top 40 enriched canonical pathways among DEGs between MCAO/R and sham groups yielded ‘pyrotosis signaling pathway’ and'neuroinflammation signaling pathway'(Fig. 1D). IPA analysis displayed the effect network associated with DEGs between sham and MCAO/R groups mainly including cell movement of monoclear leukocytes and NF-kB mediated inflammatory effect (Fig. 1E). For these pathways, IPA indicated potential molecular networks linking SPP1 and pyroptosis signaling pathway may be mediated by the NLRP3 and ASC (Fig. 1F).

Fig. 1.

Analysis of ischemic stroke-associated DEGs from brain tissue of rats. A DEGs between MCAO/R and sham groups were illustrated in the volcano plot. B The top 30 DEGs between the MCAO/R and sham groups were displayed in the heatmap. C The top 10 enriched Gene Ontology (GO) terms associated with “biological process for the DEGs between the MCAO/R and Sham groups. D Top 40 ingenuity pathway functional enrichment of DEGs between MCAO/R and Sham groups. E The effect network associated with DEGs. F Potential molecular networks linking SPP1, NLRP3,ASC and pyroptosis signaling pathway

Cerebral ischemia induces osteopontin upregulation in rats and patients

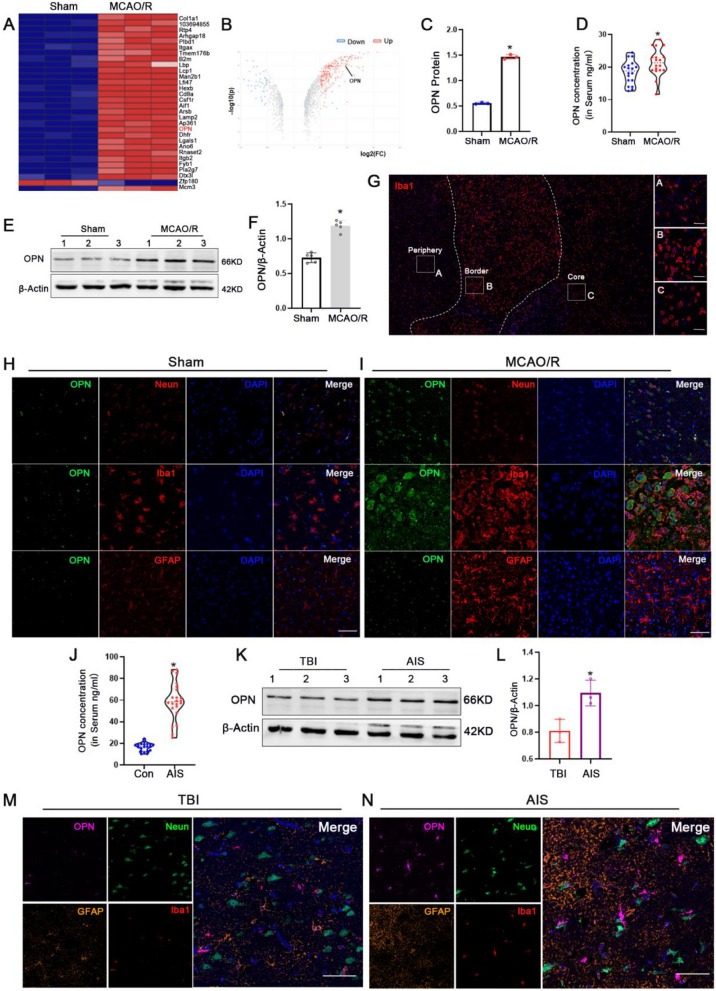

SPP1 is also named osteopontin (OPN). Bioinformatics analysis from GSE61616 showed expression of SPP1 mRNA in MCAO/R group is significantly higher than that in the sham group in rats (Fig. 1B). Our proteomics data also showed the expression of OPN protein was higher in the MCAO/R group in rats (Fig. 2A-C). ELISA analysis and western blotting showed that osteopontin concentration in serum and expression of osteopontin in cerebral tissue were elevated in MCAO/R than those in the sham group in rats, respectively (Fig. 2D-F). Immunofluorescence staining analysis indicated that osteopontin is mainly expressed on neurons and microglia in the sham group, was significantly high expression on microglia in MCAO/R group in rats (Fig. 2H,I).

Fig. 2.

Cerebral ischemia induces osteopontin upregulation in rats and patients. A-C Analysis of Proteomics. D OPN concentration in serum in the sham and MCAO/R 3 d groups by ELISA in rats (n=18). E-F OPN expression and quantification data in the sham and MCAO/R 3 d group by Western blotting in cerebral tissue of rats (n=5). G Regional segmentation of microglia in the lesion area following middle cerebral artery occlusion/reperfusion (MCAO/R) in rats. H-I Representative immunofluorescence images depicting expression of OPN in neurons, astrocytes and microglia in the sham and MCAO/R 3 d groups in rats, Scale bars=20μm. J OPN concentration in serum in the healthy control (n=20) and AIS patients (n=22) by ELISA. K-L OPN expression and quantification data in the TBI and AIS patients by Western blotting (n=3). M-N Representative immunofluorescence images depicting expression of OPN in neurons, astrocytes and microglia in the TBI and AIS patients, Scale bars=20μm. *p<0.05 vs. the sham group or the TBI group, *p <0.05 vs. the control group

Futhermore, ELISA analysis revealed significantly higher osteopontin concentrations in the serum of 22 AIS patients compared to 20 healthy controls (Fig. 2J), western blotting analysis likewise indicated a substantial upregulation in osteopontin expression in the 3 acute ischemic stroke (AIS) patients than that in the 3 traumatic brain injury (TBI) patients in brain tissue (Fig. 2K,L). The immunofluorescence staining analysis of human brain tissues revealed the expression of osteopontin is mainly expressed on microglia but not in the neurons of control patients, and the expression of osteopontin expressed on microglia was significantly upregulated of AIS patients (Fig. 2M,N).These results from MCAO/R rats and AIS patients suggest that cerebral ischemic injury upregulate osteopontin expression.

Intranasal rOPN administration ameliorates pyroptosis and improves neurological outcomes after MCAO/R in rats

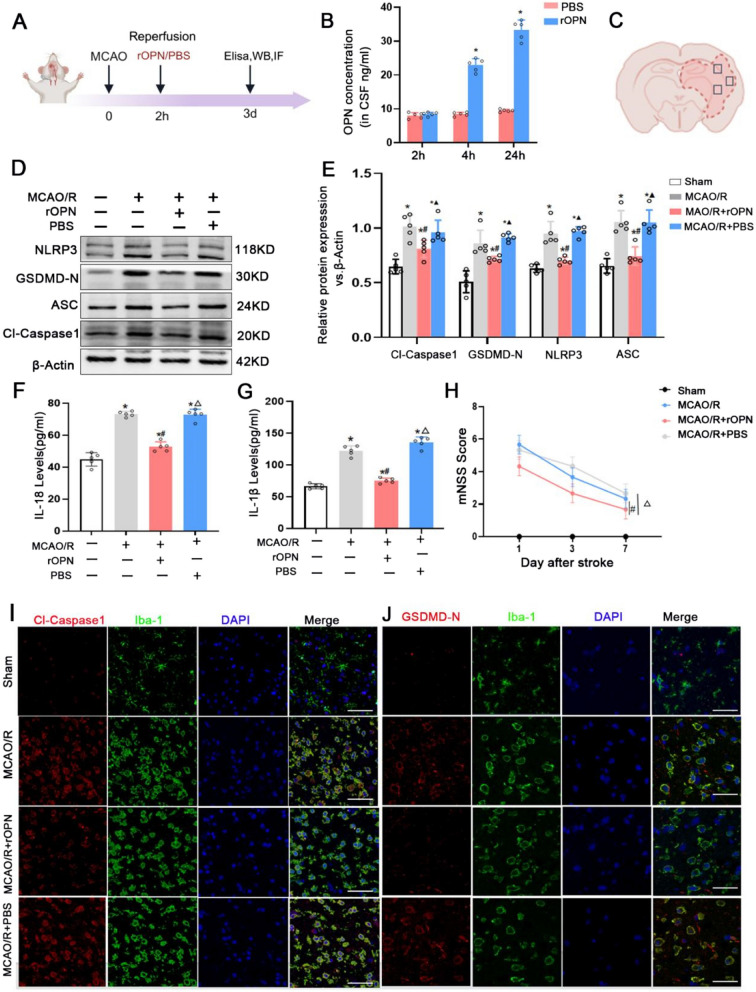

Our above results suggest that cerebral ischemic injury of MCAO/R rats and AIS patients upregulate osteopontin (SPP1) expression in brain tissue and serum. Prior investigations have demonstrated that osteopontin exerts a protective effect for ischemic brain injury [16, 17], but it remains unclear whether osteopontin exerts a neuroprotective effect by affecting pyroptosis. Therefore, we intranasally administered recombinant osteopontin (rOPN) during middle cerebral artery reperfusion to clarify effects of rOPN on pyroptosis after MCAO/R. ELISA analysis showed that rOPN concentration in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of rats was significantly increased at 4 h and 24 h after rOPN treatment, which suggest that exogenous intranasally administered rOPN can enter the brain and play a role (Fig. 3B). Cleaved caspase 1 (Cl-Caspase-1), gasdermin D N-terminal fragment (GSDMD-N), NOD-like receptor pyrin domain containing 3 (NLRP3), and apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a CARD (ASC) are markers of pyroptosis [5]. A schematic diagram of the ischemic brain was provided in Fig. 3C to indicate the region used for analysis. Western blotting results showed that expressions of Cl-Caspase-1, GSDMD-N, NLRP3, and ASC proteins were significantly increased in the MCAO/R and PBS groups compared with the Sham group, which was reversed considerably by rOPN (Fig. 3D,E). During the process of pyroptosis, IL-18 and IL-1β are liberated into the extracellular milieu, serving to attract inflammatory cells and amplify the inflammatory cascade [5]. ELISA analysis revealed elevated concentrations of IL-1β and IL-18 in the MCAO/R and PBS groups compared to the sham group, which was also reversed considerably by rOPN (Fig. 3F, G). In addition, rOPN treatment significantly attenuated mNSS score than those in the MCAO/R and PBS groups at 1 d,3d and 7 d after reperfusion (Fig. 3H).

Fig. 3.

Intranasal rOPN administration ameliorates pyroptosis and improves neurological outcomes after MCAO/R in rats. A Timeline of experiments. B OPN concentration in CSF by ELISA in the PBS and rOPN groups (n=5). C Schematic representation of rat brain coronal section, tested areas are demarcated by square outlines. D-E NLRP3, GSDMD-N, Cl-Casepase1 and ASC proteins expression and quantification data in the Sham, MCAO/R, MCAO/R+rOPN and MCAO/R+PBS groups by Western blotting (n=5). F-G IL-18 and IL-1β levels in the Sham, MCAO/R, MCAO/R+rOPN and MCAO/R+PBS groups by ELISA (n=5). H Assessment of the mNSS scores in the Sham, MCAO/R, MCAO/R+rOPN and MCAO/R+PBS groups (n=5). I-J Representative immunofluorescence images depicting expression of Cl-Caspase1 and GSDMD-N co-stained with Iba-1 in the Sham, MCAO/R, MCAO/R+rOPN and MCAO/R+PBS groups, Scale bars=50μm or 20μm. *p<0.05 vs. the Sham group, #p<0.05 vs. the MCAO/R group, △p<0.05 vs. the MCAO/R +rOPN group

As shown in Fig. 2, expression of osteopontin on microglia were especially increased after MCAO/R in rats and in AIS patients. We further observed whether rOPN affected microglial pyroptosis after MCAO/R. Immunofluorescence staining demonstrated that expressions of Cl-Caspase-1 and GSDMD-N proteins in microglia were obviously upregulated in the MCAO/R and PBS groups than those in the sham group in the ischemic area after MCAO/R, which was reversed by rOPN (Fig. 3I, J). These results suggest that intranasal administration of rOPN can ameliorate pyroptosis and improve outcome after MCAO/R. Especially, rOPN can reduce microglia pyroptosis in the infarct zone.

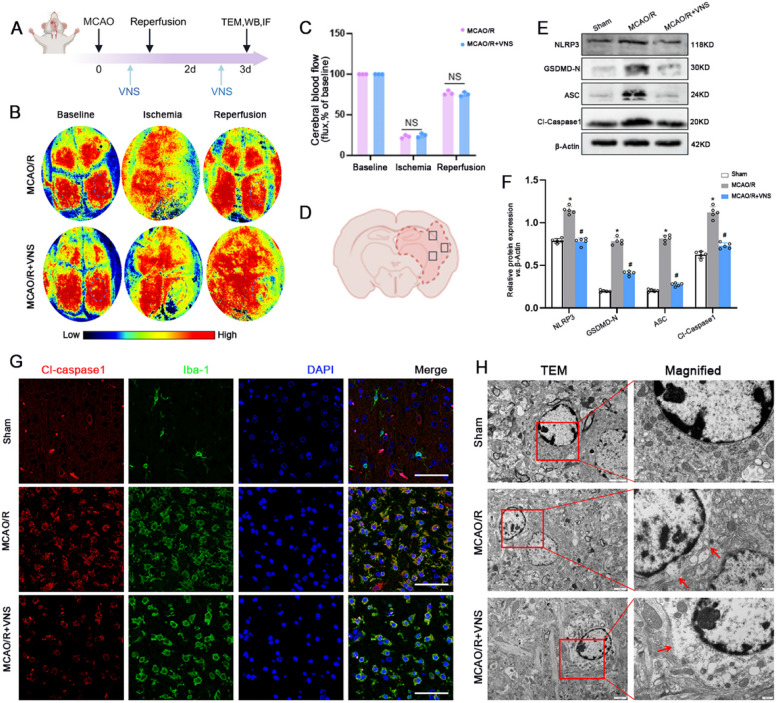

VNS reduces pyroptosis following MCAO/R in rats

VNS exerts a neuroprotective effect in ischemic stroke [5]. However, its neuroprotective mechanism remains unclear. Laser Speckle Contrast Imaging (LSCI) revealed a reduction in the right cerebral blood flow (CBF) of rats post-MCAO, followed by an increase upon reperfusion. Notably, VNS treatment did not lead to a significantly greater enhancement in CBF compared to the MCAO/R group (Fig. 4B, C). The outcomes from western blotting disclosed that expressions of Cl-Caspase-1, GSDMD-N, NLRP3, and ASC proteins were significantly increased in the MCAO/R group compared with the sham group, which was reversed by VNS treatment (Fig. 4E,F).

Fig. 4.

VNS reduces pyroptosis following MCAO/R in rats. A Timeline of the experiment. B-C LSCI was employed to assess cerebral blood flow in both the MCAO/R and the MCAO/R + VNS group. D Schematic representation of rat brain coronal section, tested areas are demarcated by square outlines. E–F NLRP3, GSDMD-N, Cl-Casepase1 and ASC proteins expression and quantification data in the Sham, MCAO/R and MCAO/R + VNS groups by Western blotting (n = 5). G Representative immunofluorescence images depicting the expression of Cl-Caspase1 co-localized with Iba-1 in the Sham, MCAO/R and MCAO/R + VNS groups, Scale bars = 20 μm. H Featured representative TEM images of microglia in the ischemic core, with red boxed areas indicating zones of enlarged view and red arrowheads pointing to membrane pore sites. *p < 0.05 vs. the Sham group, #p < 0.05 vs. the MCAO/R group

Further, immunofluorescence staining also showed that expression of Cl-Caspase1 protein in microglia (Iba-1) was significantly increased in the MCAO/R group compared with the sham group, which was reversed by VNS treatment (Fig. 4G). At the same time, transmission electron microscopy(TEM) images unveiled that, subsequent to MCAO/R injury, microglia manifested an increased number of membrane pores compared to the sham group. Notably, treatment with VNS markedly reduced the quantity of these membrane pores relative to the MCAO/R group (Fig. 4H). These findings indicate that VNS treatment may play a neuroprotective role by inhibiting pyroptosis, especially microglia pyroptosis, rather than by altering cerebral blood flow after MCAO/R.

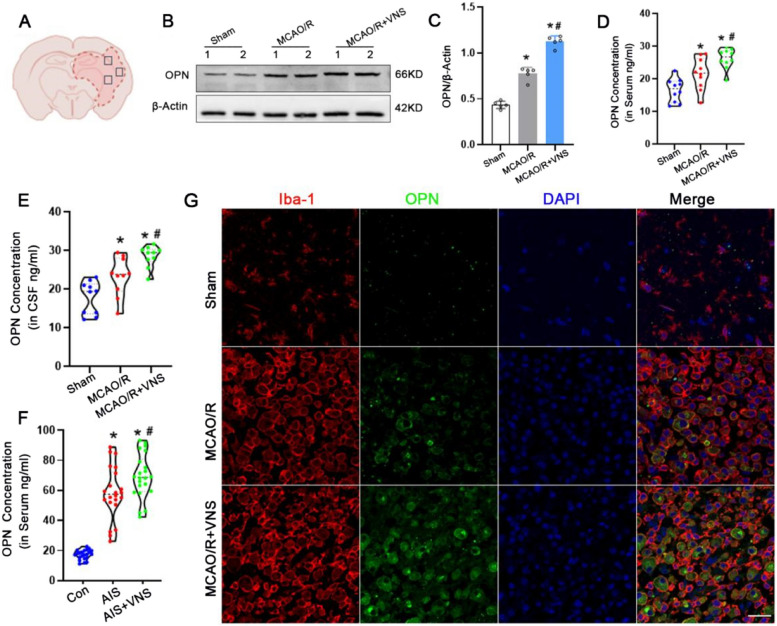

VNS upregulated osteopontin expression in MCAO/R rats and AIS patients

We further observed whether VNS treatment affected on osteopontin expression in MCAO/R rats and AIS patients. Western blotting analysis revealed that osteopontin levels in cerebral tissues was significantly upregulated in the MCAO/R group than that in the sham group, and VNS treatment more significantly enhanced osteopontin expression after MCAO/R (Fig. 5B,C). Moreover, ELISA results indicated that VNS treatment also significantly increased the osteopontin concentration in serum and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) samples of rats than those in the sham and MCAO/R groups (Fig. 5D, E).

Fig. 5.

VNS upregulaed osteopontin expression in MCAO/R rats and AIS patients. A Schematic representation of rat brain coronal section, tested areas are demarcated by square outlines. B-C Expression of osteopontin and quantification data in the Sham, MCAO/R and MCAO/R + VNS groups by Western blotting (n = 5). D-E osteopontin concentration of serum and CSF in the Sham, MCAO/R and MCAO/R + VNS groups by ELISA in rats (n = 10). F osteopontin concentration of serum in the Con, AIS and AIS + VNS groups by ELISA in patients (n = 22). G Representative immunofluorescence images depicting expression of OPN⁺/Iba-1⁺ in the Sham, MCAO/R and MCAO/R + VNS groups, Scale bars = 20 μm. *p < 0.05 vs. the Sham group, #p < 0.05 vs. the MCAO/R group

At the same time, osteopontin concentration in serum was also significantly increased in the 22 AIS patients treated with VNS than those in the 22 AIS patients and 22 healthy controls (Fig. 5F). Futhermore, immunofluorescence staining suggested that the number of OPN+/Iba-1+ cells were significantly increased after VNS treatment than those in the MCAO/R and the sham groups (Fig. 5G). These findings from MCAO/R rats and AIS patients suggest that VNS treatment upregulate osteopontin expression.

VNS reduces pyroptosis via osteopontin in rats following MCAO/R

We further inhibited osteopontin through injecting small interfering OPN RNA (siOPN) into the lateral ventricle at 3 d before MCAO/R and again at the time of reperfusion to verify whether VNS attenuated pyroptosis via osteopontin after MCAO/R in rats. As shown Fig. 6B and 6C, siOPN successfully reduced the expression of osteopontin. A schematic diagram of the ischemic brain was provided in Fig. 6D to indicate the region used for analysis. Western blotting revealed significantly higher levels of Cl-Caspase1, GSDMD-N, NLRP3, and ASC in the MCAO/R + VNS + siOPN group versus the MCAO/R + VNS and MCAO/R + VNS + siNC groups (Fig. 6E,F).

Fig. 6.

VNS reduces pyroptosis via osteopontin in rats following MCAO/R. A Timeline of the experiment. B-C Expression of osteopontin and quantification data in the Sham, siOPN and siNC groups by Western blotting (n = 3). D Schematic representation of rat brain coronal section, tested areas are demarcated by square outlines. E, F Expressions of NLRP3, GSDMD-N, ASC and Cl-Caspase1 proteins and quantification data in the Sham, MCAO/R, MCAO/R + VNS, MCAO/R + VNS + siOPN and MCAO/R + VNS + siNC groups by Western blotting (n = 5). G Representative immunofluorescence images depicting expression of Cl-Caspase1 co-localized with Iba-1 in the Sham, MCAO/R, MCAO/R + VNS, MCAO/R + VNS + siOPN and MCAO/R + VNS + siNC groups, Scale bars = 20 μm. H-I Representative immunofluorescence images depicting the expression of Cl-Caspase1 co-localized with TUNEL andquantitative analyses in the Sham, MCAO/R, MCAO/R + VNS, MCAO/R + VNS + siOPN and MCAO/R + VNS + siNC groups, Scale bars = 50 μm. J-K IL-18 and IL-1β levels in the Sham, MCAO/R, MCAO/R + VNS, MCAO/R + VNS + siOPN and MCAO/R + VNS + siNC groups by ELISA (n = 5). *p < 0.05 vs. the Sham group, #p < 0.05 vs. the MCAO/R group, △p < 0.05 vs. the MCAO/R + VNS group, ▲p < 0.05 vs. the MCAO/R + VNS + siOPN group

Moreover, Immunofluorescence staining showed that co-labeling of TUNEL and cleaved caspase-1 identified a population of double-positive cells, indicating pyroptotic cells undergoing both inflammasome activation and DNA fragmentation (Fig. 6H). Given that the majority of CL-caspase-1⁺ cells co-localized with Iba1⁺ microglia in adjacent sections (Fig. 6G), these double-positive cells are likely representative of pyroptotic microglia. Compared with the MCAO/R group, the MCAO/R + VNS group exhibited a marked reduction in the number of CL-caspase-1⁺/Iba1⁺ and TUNEL⁺/CL-caspase-1⁺ cells, suggesting that VNS effectively suppresses microglial pyroptosis following ischemic stroke. Notably, this protective effect was abolished by siRNA-mediated knockdown of OPN (Fig. 6G–I), further supporting the hypothesis that VNS mitigates microglial pyroptosis in an OPN-dependent manner.

At the same time, the levels of IL-1β and IL-18 were markedly increased following MCAO/R injury, subsequently reduced by VNS treatment, and observed to be significantly elevated in the MCAO + VNS + siOPN group compared to both the MCAO + VNS and MCAO/R + VNS + siNC groups (Fig. 6J,K). These findings suggest that VNS treatment reduced pyroptosis through osteopontin in MCAO/R in rats.

Blocking osteopontin eliminates the neuroprotective effect of VNS after MCAO/R

We proceeded to investigate whether the neuroprotective benefits of VNS treatment were mediated via osteopontin. Infarct volumes were tested by TTC staining. Long-term neurological deficits were examined by mNSS evaluation, corner test, cylinder test, rotarod test and handgrip test at 1 d, 3 d and 7 d after MCAO/R. The number of survival neurons was tested by immunofluorescence staining with NF200 antibody, a marker of neurons. Results showed that VNS treatment decreased infarct volume (Fig. 7A,B), improved neurological deficits (Fig. 7C-G), and increased the number of survival neurons (Fig. 7H) than those in the MCAO/R group, respectively. There were opposite effects in the MCAO + VNS + siOPN group (Fig. 7A-H). These finding suggested that blockade of osteopontin could negate the therapeutic effects of VNS in MCAO/R.

rOPN inhibits microglial pyroptosis and protects neurons by disrupting asc oligomerization in vitro

After MCAO/R in rats, we have confirmed that intranasally administered rOPN inhibited pyroptosis, siOPN aggravated pyroptosis, and VNS treatment ameliorated pyroptosis by upregulating osteopontin. Moreover, rOPN, siOPN and VNS especially affected pyroptosis of microglia in vivo. Further, the OGD/R and LPS + ATP models of primary microglia were constructed to verify the effect of rOPN on pyroptosis of microglia in vitro again. Western blotting results suggested that pyroptosis-related molecules including Cl-Caspase1, GSDMD-N, NLRP3 and ASC were considerably higher in the OGD/R and LPS + ATP groups than those in the Con and PBS groups (Fig. 8A,B). Immunofluorescence staining showed OPN +/Iba-1 + microglia were increased in OGD/R and LPS + ATP groups compared with Con and PBS groups (Fig. 8C). After rOPN treatment, expressions of Cl-Caspase1, GSDMD-N, NLRP3 and ASC were diminished (Fig. 8D-G). At the same time, IL-1β and IL-18 levels tested by ELISA were upregulated in OGD/R and LPS + ATP groups, downregulated by rOPN treatment(Fig. 8H-K). And, scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images unveiled that, after treatment with LPS and ATP, microglia manifested an increased number of membrane pores compared to the Con group, notably, treatment with rOPN markedly reduced the quantity of these membrane pores relative to the LPS + ATP group (Fig. 8L). These results in vitro confirmed that rOPN impedes pyroptosis of microglia again. Then, how does osteopontin affect pyroptosis?

Fig. 8.

rOPN inhibits microglial pyroptosis and protects neurons by disrupting ASC oligomerization in vitro. A-B Expressions of NLRP3, GSDMD-N, ASC and Cl-Caspase1 proteins and quantification data in the Con, PBS, OGD/R and LPS + ATP groups by Western blotting (n = 5). C Representative immunofluorescence images of OPN in microglia in the Con, PBS, OGD/R and LPS + ATP groups, Scale bars = 20 μm. D-E Expressions of NLRP3, GSDMD-N, ASC and Cl-Caspase1 proteins and quantification data in the Con, OGD/R, OGD/R + rOPN and OGD/R + PBS groups by Western blotting (n = 5). F-G Expressions of NLRP3, GSDMD-N, ASC and Cl-Caspase1 proteins and quantification data in the Con, LPS + ATP, LPS + ATP + rOPN and LPS + ATP + PBS groups by Western blotting (n = 5). H-I IL-18 and IL-1β levels in the Con, OGD/R, OGD/R + rOPN and OGD/R + PBS groups by ELISA (n = 5), J-K IL-18 and IL-1β levels in the Con, LPS + ATP, LPS + ATP + rOPN and LPS + ATP + PBS groups by ELISA (n = 5). L Featured representative SEM images of pyrotic microglial, with red boxed areas indicating zones of enlarged view and red arrowheads pointing to membrane pore sites, Scale bars = 5 μm or 1 μm. M Predicted docking module of ASC and OPN was analyzed by ZDOCK and exhibited with PyMol. N Co-IP of OPN and ASC in the Con, OGD/R and LPS + ATP groups. O ASC oligomerization in the Con, LPS + ATP, LPS + ATP + rOPN and LPS + ATP + PBS groups by Western blotting. P Exemplary immunofluorescence images showing ASC specks in microglia, Scale bars = 20 μm. Q Step of collecting microglia-conditioned medium for primary neurons culture. R-S Neuronal morphology analyses were conducted on cells treated with conditioned medium, utilizing MAP2 staining in conjunction with ImageJ software to calculate the Automated Neurite Degeneration Index (ANDI), Scale bars = 50 μm. *p < 0.05 vs. the Con group, #p < 0.05 vs. the PBS group or OGD/R group or LPS + ATP group,

Pyroptosis-related molecules including NLRP3, ASC, Cl-Caspase1 and GSDMD-N. After stimulated by pathogenic or injury-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), NLRP3, ASC and Cl-Caspase1 formed an NLRP3-ASC-Caspase1 complex (called the NLRP3 inflammasome) to further activate GSDMD-N. Activated GSDMD-N binds nonspecifically to the plasma membrane, causing the cell membrane to form small holes, ions outflow, which results in cell swell, rupture, release large amounts of pro-inflammation contents such as IL-1β and IL-18 to induce injury [5]. ASC is a key link of NLRP3-ASC-Caspase1 complex [31, 32]. Wang et al. reported that ASC oligomerization played an important role in pyroptosis, and interfering with the oligomerization of ASC can effectively inhibit pyroptosis [33]. Whether does osteopontin inhibit pyroptosis via disturbing ASC oligomerization?

We firstly employed ZDOCK to simulate molecular docking between ASC and osteopontin, and detected that the binding energy was −11.7 kcal/mol, indicating a strong potential for real binding (Fig. 8M). Next, Co-immunoprecipitation assay (Co-IP) analysis showed that OPN-ASC interaction was enhanced in the OGD/R and LPS + ATP groups compared with the Con group (Fig. 8N). At the same time, ASC oligomerization was disrupted in the LPS + ATP + rOPN group compared with the LPS + ATP and LPS + ATP + PBS groups (Fig. 8O). Futhermore, immunofluorescence staining also suggested ASC level was reduced in LPS + ATP + rOPN group (Fig. 8P). These results suggest that osteopontin disturb ASC oligomerization.

Finally, we cultured primary cortical neurons with conditioned medium from microglia to investigate whether inhibiting microglial pyroptosis with rOPN affected on neuronal survival. Analysis of neuronal morphology demonstrated that conditioned medium of microglia treated with LPS + ATP decreased total neurite length and increased fragmented neurites. Conversely, conditioned medium of microglia treated with rOPN maintained the typical morphology of neurons. It suggest that inhibiting microglial pyroptosis with rOPN reveal a neuroprotective effect (Fig. 8R,S).

Taken together, these results demonstrate that rOPN inhibits ASC oligomerization, impairs NLRP3 inflammasome assembly, and reduces pyroptosis in microglia, thereby contributing to neuronal protection.

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrated that osteopontin (OPN) expression is upregulated in both MCAO/R rats and AIS patients. Intranasal administration of rOPN and VNS treatment significantly inhibited pyroptosis and improved neurological outcomes in rats following ischemic stroke. Notably, VNS upregulated OPN expression in both animal and human samples, and silencing OPN reversed the protective effects of VNS on pyroptosis and infarct outcome. Molecular docking revealed a strong binding affinity between OPN and ASC (−11.7 kcal/mol), which was confirmed by Co-IP. LPS + ATP stimulation enhanced OPN–ASC interaction, while rOPN disrupted ASC oligomerization, a key step in inflammasome activation. Moreover, conditioned medium from rOPN-treated microglia reversed LPS + ATP-induced neuronal injury. Together, these findings from both in vivo and in vitro studies suggest that VNS suppresses pyroptosis and promotes recovery after ischemic stroke via OPN upregulation, which in turn interferes with ASC oligomerization.

Osteopontin (OPN,SPP1) is a multifunctional, highly phosphorylated glycoprotein that acts as both an adhesive molecule and a cytokine, binding to receptors such as integrins and CD44 variants [34]. While its expression is low in the brain under normal conditions, it is significantly upregulated in microglia, astrocytes, perivascular fibroblasts, and cerebrospinal fluid under various pathological conditions [15, 35–40]. Consistent with previous studies reporting its neuroprotective functions in stroke, TBI, and neurodegenerative diseases [41–50], our results confirm OPN elevation in ischemic brain tissue and serum, and further demonstrate its anti-pyroptotic effects. Prior work has shown that OPN reduces apoptosis, modulates neuroinflammation, maintains blood–brain barrier integrity, and alleviates edema [51–60], while also promoting cell survival, proliferation, and differentiation in neural and vascular cell types [61–63]. Our findings expand upon these earlier studies by showing that rOPN also modulates pyroptosis through direct interference with ASC oligomerization.

Pyroptosis, characterized by inflammasome activation, plays a critical role in ischemic injury. The NLRP3 inflammasome, composed of NLRP3, ASC, and pro-caspase-1, is one of the most extensively studied inflammasome complexes and is central to the canonical pyroptotic pathway [11, 64–66]. Upon activation, ASC oligomerization leads to caspase-1 activation and the release of IL-1β and IL-18, amplifying neuroinflammation [67]. Previous studies have reported that VNS can attenuate neuronal pyroptosis by modulating α7nAChR signaling [5]. Our data show that VNS reduces the expression of NLRP3, ASC, cleaved caspase-1, and GSDMD-N. In addition, it lowers infarct volume and improves neurological deficits. These protective effects were abolished by siOPN, which supports the involvement of the OPN–NLRP3 axis in mediating the neuroprotective actions of VNS.

Several limitations of this study should be acknowledged. First, the findings are based on a single MCAO/R animal model, which may not fully replicate the complexity of human stroke. Second, we did not evaluate the long-term outcomes of rOPN or VNS treatment. Third, the upstream mechanisms by which VNS regulates OPN expression remain unclear. Future studies addressing these limitations will be essential to enhance mechanistic understanding and translational relevance.

Further investigations are warranted to identify the precise cellular sources of OPN under ischemic conditions and during VNS stimulation. While microglia are likely contributors, other glial or vascular cells may also be involved. In addition, it is important to explore the specific receptors involved in OPN signaling, such as integrins and CD44 isoforms, as well as the involvement of OPN in other inflammasome pathways, including NLRC4, AIM2, or the non-canonical NLRP3 pathway. Exploring the therapeutic efficacy of OPN during the chronic phase of stroke, particularly its effects on synaptic plasticity and neurogenesis, represents another important direction for future research.

In conclusion, our study demonstrates that VNS promotes recovery after ischemic stroke by upregulating OPN. OPN suppresses pyroptosis by interfering with ASC oligomerization (Fig. 9). This work uncovers a novel link between VNS and inflammasome regulation and identifies OPN as a promising therapeutic target for ischemic brain injury.

Fig. 9.

Schematic diagram illustrating the mechanism by which vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) suppresses microglial pyroptosis after ischemic stroke by modulating osteopontin (OPN) expression and targeting the NLRP3 inflammasome pathway. VNS treatment induced upregulation of osteopontin (OPN) expression following ischemic stroke. OPN may bind to apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a CARD (ASC), thereby inhibiting ASC oligomerization and subsequent assembly of the NLRP3 inflammasome. This leads to reduced caspase-1 activation, suppressing the cleavage of pro-IL-1β and pro-IL-18 into their mature pro-inflammatory forms (IL-1β and IL-18), as well as inhibiting gasdermin D (GSDMD)-mediated pyroptosis. As a result, microglial pyroptosis is attenuated, contributing to improved neurological outcomes after ischemic brain injury

Conclusions

These findings from AIS patients and MCAO/R rats, both in vivo and in vitro, suggest that VNS alleviates pyroptosis and improves the outcome of ischemic stroke by upregulating osteopontin, which disrupts ASC oligomerization. This mechanism may provide a novel therapeutic target for the treatment of ischemic stroke.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Table S1. Demographic characteristics of healthy controls, AIS patients and AIS + VNS patients in the deprivation cohort. Table S2. siRNA sequences

Additional file 2: Figure S1. An illustrative image of vagus nerve stimulation in SD rats following middle cerebral artery occlusion and reperfusion

Acknowledgements

The illustration was partly created with BioRender.com.

Abbreviations

- AIM2

Absent in Melanoma 2 Inflammasome

- AIS

Acute ischemic stroke

- ASC

Apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a CARD

- ATP

Adenosine triphosphate

- VNS

Vagus nerve stimulation

- CBF

Cerebral Blood Flow

- CNS

Central Nervous System

- Co-IP

Co-immunoprecipitation

- CSF

Cerebrospinal Fluid

- DAPI

4',6-Diamidino-2-Phenylindole

- DEGs

Differentially Expressed Genes

- Elisa

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- GFAP

Glial Fibrillary Acidic Protein

- Iba-1

Ionized Calcium-Binding Adapter Molecule 1

- IPA

Ingenuity Pathway Analysis

- IPAF

Ice Protease-Activating Factor

- LPS

Lipopolysaccharide

- LSCI

Laser speckle contrast imaging

- MCAO/R

Middle cerebral artery ischemia–reperfusion

- Neun

Neuronal Nuclei

- NLRC

NOD-like receptor family CARD domain-containing

- NLRP1

NOD-like receptor family pyrin domain containing 1

- NLRP3

NOD-like receptor family pyrin domain containing 3

- OPN

Osteopontin

- OGD/R

Oxygen-glucose deprivation and reperfusion

- PVDF

Polyvinylidene fluoride

- rOPN

Recombinant Osteopontin

- SD rats

Sprague-Dawley rats

- SEM

Scanning electron microscopy

- siNC

Small interfering Negative Control

- siOPN

Small interfering OPN RNA

- TBI

Traumatic brain injury

- TEM

Transmission electron microscopy

- TUNEL

Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling

- TTC

2,3,5-Triphenyltetrazolium Chloride

Authors’ contributions

WJ,TH and WL conceived and designed the experiments. WJ, TH, RY performed the experiments. YQH, ZY and QT analyzed the data. LXM, XJF and YQ contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools. WJ wrote the first draft of the manuscript. YQ and JGW critically reviewed and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant no. 82171456, 81971229 and 82472616), the Natural Science Foundation of Chongqing municipality (Grant no.CSTC2021JCYJ-MSXMX0263 and CSTB2023NSCQ-MSX1015) and The First Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical University, Doctoral Innovation Project of The First Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical University, CYYY-BSYJSCXXM-202318 and CYYY-BSYJSCXXM-202327.

Data availability

We would like to clarify that the proteomics dataset generated in this study is currently being used in additional unpublished studies. As such, the data are not publicly available at this stage, but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request and will be made publicly accessible following the publication of those subsequent studies.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study received approval from the ethics committee at Chongqing Medical University Hospital (number, K2023-270) before initiation and complied with the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical approval for the animal experiments were granted by the Animal Ethics Committee at Chongqing Medical University (number, 2022–04).

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Jun Wen and Hao Tang contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Gongwei Jia, Email: jiagongwei@hospital.cqmu.edu.cn.

Qin Yang, Email: xyqh200@126.com.

References

- 1.Paul S, Candelario-Jalil E. Emerging neuroprotective strategies for the treatment of ischemic stroke: an overview of clinical and preclinical studies. Exp Neurol. 2021;335: 113518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sun R, Peng M, Xu P, Huang F, Xie Y, Li J, et al. Low-density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR) regulates NLRP3-mediated neuronal pyroptosis following cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury. J Neuroinflammation. 2020;17(1):330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gonzalez HFJ, Yengo-Kahn A, Englot DJ. Vagus nerve stimulation for the treatment of epilepsy. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 2019;30:219–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carreno FR, Frazer A. Vagal nerve stimulation for treatment-resistant depression. Neurotherapeutics. 2017;14(3):716–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tang H, Li J, Zhou Q, Li S, Xie C, Niu L, et al. Vagus nerve stimulation alleviated cerebral ischemia and reperfusion injury in rats by inhibiting pyroptosis via α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. Cell Death Discov. 2022;8(1):54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dawson J, Liu CY, Francisco GE, Cramer SC, Wolf SL, Dixit A, et al. Vagus nerve stimulation paired with rehabilitation for upper limb motor function after ischaemic stroke (VNS-REHAB): a randomised, blinded, pivotal, device trial. Lancet. 2021;397(10284):1545–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Luo L, Liu M, Fan Y, Zhang J, Liu L, Li Y, et al. Intermittent theta-burst stimulation improves motor function by inhibiting neuronal pyroptosis and regulating microglial polarization via TLR4/NFκB/NLRP3 signaling pathway in cerebral ischemic mice. J Neuroinflammation. 2022;19(1):141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu L, Zhang J, Lu K, Zhang Y, Xu X, Deng J, et al. ChemR23 signaling ameliorates brain injury via inhibiting NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated neuronal pyroptosis in ischemic stroke. J Transl Med. 2024;22(1):23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tobin MK, Bonds JA, Minshall RD, Pelligrino DA, Testai FD, Lazarov O. Neurogenesis and inflammation after ischemic stroke: what is known and where we go from here. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2014;34(10):1573–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Poh L, Kang SW, Baik SH, Ng GYQ, She DT, Balaganapathy P, et al. Evidence that NLRC4 inflammasome mediates apoptotic and pyroptotic microglial death following ischemic stroke. Brain Behav Immun. 2019;75:34–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang L, Xue S, Fei C, Yu C, Li J, Li Y, et al. Protective effect of Tao Hong Si Wu Decoction against inflammatory injury caused by intestinal flora disorders in an ischemic stroke mouse model. BMC Complement Med Ther. 2024;24(1):124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jia H, Qi X, Fu L, Wu H, Shang J, Qu M, et al. NLRP3 inflammasome inhibitor ameliorates ischemic stroke by reprogramming the phenotype of microglia/macrophage in a murine model of distal middle cerebral artery occlusion. Neuropathology. 2022;42(3):181–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ge Y, Wang L, Wang C, Chen J, Dai M, Yao S, et al. CX3CL1 inhibits NLRP3 inflammasome-induced microglial pyroptosis and improves neuronal function in mice with experimentally-induced ischemic stroke. Life Sci. 2022;300:120564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sun C, Rahman MSU, Enkhjargal B, Peng J, Zhou K, Xie Z, et al. Osteopontin modulates microglial activation states and attenuates inflammatory responses after subarachnoid hemorrhage in rats. Exp Neurol. 2024;371:114585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Iczkiewicz J, Rose S, Jenner P. Osteopontin expression in activated glial cells following mechanical- or toxin-induced nigral dopaminergic cell loss. Exp Neurol. 2007;207(1):95–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sun C, Enkhjargal B, Reis C, Zhang T, Zhu Q, Zhou K, et al. Osteopontin-Enhanced Autophagy Attenuates Early Brain Injury via FAK-ERK Pathway and Improves Long-Term Outcome after Subarachnoid Hemorrhage in Rats. Cells. 2019;8(9):980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sun CM, Enkhjargal B, Reis C, Zhou KR, Xie ZY, Wu LY, et al. Osteopontin attenuates early brain injury through regulating autophagy-apoptosis interaction after subarachnoid hemorrhage in rats. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2019;25(10):1162–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Torrens-Mas M, Pons DG, Sastre-Serra J, Oliver J, Roca P. Sexual hormones regulate the redox status and mitochondrial function in the brain. Pathological implications Redox Biol. 2020;31:101505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ikeda K, Negishi H, Yamori Y. Antioxidant nutrients and hypoxia/ischemia brain injury in rodents. Toxicology. 2003;189(1–2):55–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Longa EZ, Weinstein PR, Carlson S, Cummins R. Reversible middle cerebral artery occlusion without craniectomy in rats. Stroke. 1989;20(1):84–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Veríssimo LF, Alves FHF, Estrada VB, da Costa Marques LA, Andrade KC, Bonancea AM, et al. Cardiovascular effects of early maternal separation and escitalopram treatment in rats with depressive-like behaviour. Auton Neurosci. 2024;256:103223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Percie du Sert N, Alfieri A, Allan SM, Carswell HV, Deuchar GA, Farr TD, et al. The IMPROVE Guidelines (Ischaemia Models: Procedural Refinements Of in Vivo Experiments). J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2017;37(11):3488–517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Percie du Sert N, Hurst V, Ahluwalia A, Alam S, Avey MT, Baker M, et al. The ARRIVE guidelines 2.0: Updated guidelines for reporting animal research. Exp Physiol. 2020;105(9):1459–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ay I, Sorensen AG, Ay H. Vagus nerve stimulation reduces infarct size in rat focal cerebral ischemia: an unlikely role for cerebral blood flow. Brain Res. 2011;1392:110–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xia XM, Duan Y, Wang YP, Han RX, Dong YF, Jiang SY, et al. Vagus nerve stimulation as a promising neuroprotection for ischemic stroke via α7nAchR-dependent inactivation of microglial NLRP3 inflammasome. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2024;45(7):1349–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yu P, Wang L, Tang F, Guo S, Liao H, Fan C, et al. Resveratrol-mediated neurorestoration after cerebral ischemic injury - Sonic Hedgehog signaling pathway. Life Sci. 2021;280: 119715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li R, Song M, Zheng Y, Zhang J, Zhang S, Fan X. Naoxueshu oral liquid promotes hematoma absorption by targeting CD36 in M2 microglia via TLR4/MyD88/NF-κB signaling pathway in rats with intracerebral hemorrhage. J Ethnopharmacol. 2024;319(Pt 1):117–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hosomoto K, Sasaki T, Yasuhara T, Kameda M, Sasada S, Kin I, et al. Continuous vagus nerve stimulation exerts beneficial effects on rats with experimentally induced Parkinson’s disease: Evidence suggesting involvement of a vagal afferent pathway. Brain Stimul. 2023;16(2):594–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bai S, Lu X, Pan Q, Wang B, Pong UK, Yang Y, et al. Cranial Bone Transport Promotes Angiogenesis, Neurogenesis, and Modulates Meningeal Lymphatic Function in Middle Cerebral Artery Occlusion Rats. Stroke. 2022;53(4):1373–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yan J, Zhang Y, Wang L, Li Z, Tang S, Wang Y, et al. TREM2 activation alleviates neural damage via Akt/CREB/BDNF signalling after traumatic brain injury in mice. J Neuroinflammation. 2022;19(1):289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lu A, Magupalli VG, Ruan J, Yin Q, Atianand MK, Vos MR, et al. Unified polymerization mechanism for the assembly of ASC-dependent inflammasomes. Cell. 2014;156(6):1193–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang K, Sun Q, Zhong X, Zeng M, Zeng H, Shi X, et al. Structural Mechanism for GSDMD Targeting by Autoprocessed Caspases in Pyroptosis. Cell. 2020;180(5):941-955.e20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang Y, Cao C, Zhu Y, Fan H, Liu Q, Liu Y, et al. TREM2/β-catenin attenuates NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated macrophage pyroptosis to promote bacterial clearance of pyogenic bacteria. Cell Death Dis. 2022;13(9):771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yokosaki Y, Tanaka K, Higashikawa F, Yamashita K, Eboshida A. Distinct structural requirements for binding of the integrins alphavbeta6, alphavbeta3, alphavbeta5, alpha5beta1 and alpha9beta1 to osteopontin. Matrix Biol. 2005;24(6):418–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wung JK, Perry G, Kowalski A, Harris PL, Bishop GM, Trivedi MA, et al. Increased expression of the remodeling- and tumorigenic-associated factor osteopontin in pyramidal neurons of the Alzheimer’s disease brain. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2007;4(1):67–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Choi JS, Kim HY, Cha JH, Choi JY, Lee MY. Transient microglial and prolonged astroglial upregulation of osteopontin following transient forebrain ischemia in rats. Brain Res. 2007;1151:195–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Günther M, Plantman S, Davidsson J, Angéria M, Mathiesen T, Risling M. COX-2 regulation and TUNEL-positive cell death differ between genders in the secondary inflammatory response following experimental penetrating focal brain injury in rats. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2015;157(4):649–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gao N, Zhang-Brotzge X, Wali B, Sayeed I, Chern JJ, Blackwell LS, et al. Plasma osteopontin may predict neuroinflammation and the severity of pediatric traumatic brain injury. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2020;40(1):35–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Månberg A, Skene N, Sanders F, Trusohamn M, Remnestål J, Szczepińska A, et al. Altered perivascular fibroblast activity precedes ALS disease onset. Nat Med. 2021;27(4):640–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.De Schepper S, Ge JZ, Crowley G, Ferreira LSS, Garceau D, Toomey CE, et al. Perivascular cells induce microglial phagocytic states and synaptic engulfment via SPP1 in mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Neurosci. 2023;26(3):406–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chan JL, Reeves TM, Phillips LL. Osteopontin expression in acute immune response mediates hippocampal synaptogenesis and adaptive outcome following cortical brain injury. Exp Neurol. 2014;261:757–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Meller R, Stevens SL, Minami M, Cameron JA, King S, Rosenzweig H, et al. Neuroprotection by osteopontin in stroke. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2005;25(2):217–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Doyle KP, Yang T, Lessov NS, Ciesielski TM, Stevens SL, Simon RP, et al. Nasal administration of osteopontin peptide mimetics confers neuroprotection in stroke. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2008;28(6):1235–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Topkoru BC, Altay O, Duris K, Krafft PR, Yan J, Zhang JH. Nasal administration of recombinant osteopontin attenuates early brain injury after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Stroke. 2013;44(11):3189–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Suzuki H, Ayer R, Sugawara T, Chen W, Sozen T, Hasegawa Y, et al. Protective effects of recombinant osteopontin on early brain injury after subarachnoid hemorrhage in rats. Crit Care Med. 2010;38(2):612–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wu J, Zhang Y, Yang P, Enkhjargal B, Manaenko A, Tang J, et al. Recombinant Osteopontin Stabilizes Smooth Muscle Cell Phenotype via Integrin Receptor/Integrin-Linked Kinase/Rac-1 Pathway After Subarachnoid Hemorrhage in Rats. Stroke. 2016;47(5):1319–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jin Y, Kim IY, Kim ID, Lee HK, Park JY, Han PL, et al. Biodegradable gelatin microspheres enhance the neuroprotective potency of osteopontin via quick and sustained release in the post-ischemic brain. Acta Biomater. 2014;10(7):3126–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Powell MA, Black RT, Smith TL, Reeves TM, Phillips LL. Matrix Metalloproteinase 9 and Osteopontin Interact to Support Synaptogenesis in the Olfactory Bulb after Mild Traumatic Brain Injury. J Neurotrauma. 2019;36(10):1615–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dixon B, Malaguit J, Casel D, Doycheva D, Tang J, Zhang JH, et al. Osteopontin-Rac1 on Blood-Brain Barrier Stability Following Rodent Neonatal Hypoxia-Ischemia. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 2016;121:263–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chen W, Ma Q, Suzuki H, Hartman R, Tang J, Zhang JH. Osteopontin reduced hypoxia-ischemia neonatal brain injury by suppression of apoptosis in a rat pup model. Stroke. 2011;42(3):764–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chiocchetti A, Indelicato M, Bensi T, Mesturini R, Giordano M, Sametti S, et al. High levels of osteopontin associated with polymorphisms in its gene are a risk factor for development of autoimmunity/lymphoproliferation. Blood. 2004;103(4):1376–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang W, Cui Y, Gao J, Li R, Jiang X, Tian Y, et al. Recombinant Osteopontin Improves Neurological Functional Recovery and Protects Against Apoptosis via PI3K/Akt/GSK-3β Pathway Following Intracerebral Hemorrhage. Med Sci Monit. 2018;24:1588–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.He J, Liu M, Liu Z, Luo L. Recombinant osteopontin attenuates experimental cerebral vasospasm following subarachnoid hemorrhage in rats through an anti-apoptotic mechanism. Brain Res. 2015;1611:74–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang X, Louden C, Yue TL, Ellison JA, Barone FC, Solleveld HA, et al. Delayed expression of osteopontin after focal stroke in the rat. J Neurosci. 1998;18(6):2075–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ladwig A, Walter HL, Hucklenbroich J, Willuweit A, Langen KJ, Fink GR, et al. Osteopontin Augments M2 Microglia Response and Separates M1- and M2-Polarized Microglial Activation in Permanent Focal Cerebral Ischemia. Mediators Inflamm. 2017;2017:7189421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Al DH. Neuroprotective effect of resveratrol against late cerebral ischemia reperfusion induced oxidative stress damage involves upregulation of osteopontin and inhibition of interleukin-1beta. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2017;68(1):47–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nakatsuka Y, Shiba M, Nishikawa H, Terashima M, Kawakita F, Fujimoto M, et al. Acute-Phase Plasma Osteopontin as an Independent Predictor for Poor Outcome After Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage. Mol Neurobiol. 2018;55(8):6841–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Suzuki H, Hasegawa Y, Kanamaru K, Zhang JH. Mechanisms of osteopontin-induced stabilization of blood-brain barrier disruption after subarachnoid hemorrhage in rats. Stroke. 2010;41(8):1783–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Iwanaga Y, Ueno M, Ueki M, Huang CL, Tomita S, Okamoto Y, et al. The expression of osteopontin is increased in vessels with blood-brain barrier impairment. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2008;34(2):145–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gong L, Manaenko A, Fan R, Huang L, Enkhjargal B, McBride D, et al. Osteopontin attenuates inflammation via JAK2/STAT1 pathway in hyperglycemic rats after intracerebral hemorrhage. Neuropharmacology. 2018;138:160–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gliem M, Krammes K, Liaw L, van Rooijen N, Hartung HP, Jander S. Macrophage-derived osteopontin induces reactive astrocyte polarization and promotes re-establishment of the blood brain barrier after ischemic stroke. Glia. 2015;63(12):2198–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lee H, Jin YC, Kim SW, Kim ID, Lee HK, Lee JK. Proangiogenic functions of an RGD-SLAY-containing osteopontin icosamer peptide in HUVECs and in the postischemic brain. Exp Mol Med. 2018;50(1):e430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Brenner D, Labreuche J, Touboul PJ, Schmidt-Petersen K, Poirier O, Perret C, et al. Cytokine polymorphisms associated with carotid intima-media thickness in stroke patients. Stroke. 2006;37(7):1691–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fann DY, Lim YA, Cheng YL, Lok KZ, Chunduri P, Baik SH, et al. Evidence that NF-κB and MAPK Signaling Promotes NLRP Inflammasome Activation in Neurons Following Ischemic Stroke. Mol Neurobiol. 2018;55(2):1082–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ren H, Kong Y, Liu Z, Zang D, Yang X, Wood K, et al. Selective NLRP3 (Pyrin Domain-Containing Protein 3) Inflammasome Inhibitor Reduces Brain Injury After Intracerebral Hemorrhage. Stroke. 2018;49(1):184–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hao Y, Ding J, Hong R, Bai S, Wang Z, Mo C, et al. Increased interleukin-18 level contributes to the development and severity of ischemic stroke. Aging (Albany NY). 2019;11(18):7457–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Soriano-Teruel PM, García-Laínez G, Marco-Salvador M, Pardo J, Arias M, DeFord C, et al. Identification of an ASC oligomerization inhibitor for the treatment of inflammatory diseases. Cell Death Dis. 2021;12(12):1155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Table S1. Demographic characteristics of healthy controls, AIS patients and AIS + VNS patients in the deprivation cohort. Table S2. siRNA sequences

Additional file 2: Figure S1. An illustrative image of vagus nerve stimulation in SD rats following middle cerebral artery occlusion and reperfusion

Data Availability Statement

We would like to clarify that the proteomics dataset generated in this study is currently being used in additional unpublished studies. As such, the data are not publicly available at this stage, but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request and will be made publicly accessible following the publication of those subsequent studies.