Abstract

Myocardial infarction (MI) is the leading cause of death worldwide. Exogenous delivery of nitric oxide (NO) shows great potential in MI treatment. However, the burst generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in ischemic microenvironment of MI oxidize NO to harmful peroxynitrite (ONOO−). It renders secondary damage to cardiomyocyte, causing the failure of NO based therapies. Herein, we proposed an ROS responsive peptide-drug conjugates (PDCs) to overcome the dilemma of NO based therapy. The conjugated cardiac injury targeting peptide (CTP) in the PDC (named CTP-PBA-ISN) promoted selective accumulation of drugs in MI sites. Besides, controlled release of NO prodrug isosorbide mononitrate (ISN) was achieved by pathological ROS triggered hydrolysis of boronate ester. Meanwhile the antioxidant byproduct 4-hydroxybenzyl alcohol further scavenges the overwhelming ROS, reducing the production of RNS and improving the bioavailability of NO. The CTP-PBA-ISN efficiently inhibited myocardial apoptosis, improved myocardial function, and ameliorated adverse cardiac remodeling post-MI in mice by relief of oxidative stress, promotion of angiogenesis and restoration of mitochondrial homeostasis and function. These findings prove that the synergic ROS regulation is essential in maximizing therapeutic effects of NO. Our CTP-PBA-ISN may serve as a valuable inspiration for development of other treatments of myocardial infarction and other ischemic diseases.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12951-025-03578-6.

Keywords: Myocardial infarction, Nitric oxide, Reactive oxygen species, Peptide-drug conjugate, Mitochondrial homeostasis

Introduction

Cardiac myocytes are highly differentiated somatic cells with weak self-regenerating ability [1–3]. Due to their high metabolic activities, maintaining sufficient energy supply is extremely vital for the health and functions of cardiac myocytes [4, 5]. It also makes them particularly vulnerable to factors of stress [6]. Myocardial infarction (MI) is one of leading causes of global mortality [7, 8]. During MI, restrained blood flow seriously dampens the functions of myocardial mitochondria, causing reduction in ATP production and initiating mitochondria-related apoptosis [9]. The lack of oxygen supply causes massive irreversible damage and remodulation of the heart tissues, inevitably leading to heart failure. Even with timely percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), the 10-year mortality rate of MI was still as high as 72.7% [10]. Therefore, alternating treatments that can improve the health quality and life span of MI patients are always sought after in both clinics and pre-clinic researches.

Nitric oxide (NO) is a Nobel Prize laureated signaling molecule, with a wide variety of psychological functions in cardiovascular homeostasis, including artery vasodilatation, fibrosis inhibition and regulation of inflammation [11, 12]. During cardiovascular events, production of NO was elevated, potentially as a protective mechanism for cardiomyocyte via ion channel remodulation [13, 14]. On the other hand, NO can also promote angiogenesis via VEGF related signaling to allow locally reconstruction of blood supply in the infarct region, reducing myocytes hypoxia and enhancing mitochondria functions [15]. Therefore, NO has long been regarded as a promising strategy for post-treatment of MI. Unfortunately, despite of efforts in decades, barely any NO-based therapies in MI treatments have made it to clinical translation, with only nitrate drugs as exceptional examples. These NO donors overcame the disadvantages of the short half-life and diffusion radium of NO gas molecule, and achieved certain degree of success in cardiovascular medications. However, the long-term use of these drugs is often complicated with extra restrictions, due to side effects and reduction in effectiveness [16, 17]. Besides, large cohort retrospective studies of nitrate drugs in recent years revealed the limited, and sometimes conflicting, therapeutic outcome of nitrate drugs in MI therapies [18, 19]. These facts undoubtably cast a long shadow over NO-based treatments in MI related medical applications.

One of the key reasons for these undesirable results is the indiscriminate distribution of the NO prodrugs, causing relatively low accumulation in the infarct heart tissue [20, 21]. Besides, the high level of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in the pathological microenvironment of MI can also react with the released NO. The converted reactive nitrogen species (RNS), including peroxynitrite (ONOO−), not only reduced NO availability, but also exert higher cytotoxicity towards myocytes than ROS [22, 23]. These factors constitute great challenges in improving the therapeutic effects of NO prodrugs. Multifunctional platforms with both ROS eliminating and NO releasing properties may serve as a solution to the above-mentioned obstacles. Previously, a ROS-responsive/eliminating nanodrugs for targeted delivery of NO were developed by our group, via host-guest assembly between β-CD based antioxidants and first line clinic NO donor isosorbide dinitrate [24]. The system proved more effective in minimizing undesirable side-reaction with ROS and improving NO viability. However, most nano-based multifunctional systems were flawed with drawbacks of complicate formulation, obscure chemical structure, differences among batches and skeptical stability in vivo [25]. These problems undoubtably increase the difficulties for future translation. Therefore, delivery systems with elegant design, clear chemical structures and facile function integration are of great value in both research and potential translation of NO based MI therapy.

PDCs, known as peptide-drug conjugates, are a new class of emerging pro-drugs [26, 27]. Unlike most nanodrugs, PDCs have defined chemical structure, therefore having better quality control over different batches. Administrated via intravenous injection, PDCs can facilitate special accumulation at site of interests via peptide-target interaction. In addition, stimuli-responsive drug release and synergy among multiple drugs can be readily achieved by intentional design of linkers between peptides and payload drugs [28]. Compared with antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs), PDCs present simpler design, cheaper synthesis, decreased immunogenicity and enhanced tissue penetration [29, 30]. So far, most PDCs and ADCs are mainly focused on oncology fields, with rare reports of cardiovascular applications. Nevertheless, the benefits bestowed by PDCs techniques may offer a possibility to overcome the disadvantages of conventional NO therapies and NO based nano-drugs.

Bearing with these thoughts, herein, we designed and fabricated an ROS responsive peptide based NO prodrug with ROS eliminating ability to explore the potential of PDCs in MI treatments. Isosorbide mononitrate (ISN), a nitrate drug in clinical use, was chosen as the NO donor and conjugated to cardiac injury targeting CSTSMLKAC cyclo-peptide (CTP), via orthogonal reactions between azide-alkyne and boronic acid-catechol (Figure S1). Taking the advantages of 1,6-elimination on phenyl boronic acid esters (PBEs) after reacting with H2O2, the obtained PDCs (CTP-PBA-ISN) were designed to release ISN in a traceless manner by stimuli of overwhelming ROS in the microenvironment of infarct area. Moreover, the byproduct 4-hydroxybenzyl alcohol (HBA) acts as a potent anti-oxidant, further reducing the NO-scavenging ROS. We hypothesize that the combination of targeting delivery and ROS elimination/responsive NO release will boost the accumulation of NO at MI sites. The enhanced availability of NO will achieve better preservation of myocytes via revascularization in infarct area and restoration of mitochondria homeostasis. The therapeutic effects of CTP-PBA-ISN were thoroughly evaluated on standard left descending anterior ligation model of mice (Scheme 1). The new strategy will serve as an inspiration for the development of future NO based prodrugs with great translational value for efficient MI therapy.

Scheme 1.

Schematic illustration of ROS-responsive/scavenging PDCs for myocardial infarction treatment. Enhanced MI accumulation was achieved by peptide-targeting delivery and ROS responsive drug release. Harmful generation of RNS was inhibited by the ROS-stimuli scavenging of boronate ester hydrolysis. The subsequent increase in NO bio-availability promoted angiogenesis in MI lesion and restored mitochondria homeostasis, attenuating myocardial apoptosis and preserving normal functions of heart

Results and discussion

Synthesis and characterization of PDCs

ISN is a first-line NO releasing drug used in clinics for treatment of angina pectoris. We chose ISN for further modification, due to its obvious shortcomings of indiscriminate distribution in the body and resistance development during long-term use [21]. The hydroxyl group on ISN was conjugated to (4-(hydroxymethyl) phenyl) boronic acid (PBA) via a four steps synthesis to obtain the ROS responsive prodrug PBA-ISN (Figure S1A). Under oxidation, it may release ISN via the ROS responsiveness of boronate and unique 1–4 elimination of the resulting intermediates (Fig. 1C). The structure and mass of components in each step were confirmed by 1H NMR, 13C NMR and Q-TOF, respectively (Figure S2-S9). To attach the PBA-ISN to DBCO modified peptides, a linker was further synthesized via EDCl and HOBT catalyzed amide reactions between dopamine and 4-azidobenzoic acid (Figure S1B, S10 and S11). The resulting Azido-BA-DPA contains catechol and azido groups, which can readily react with boronic acid from the PBA-ISN and DBCO from the peptides, respectively (Fig. 1A and S1C). The successful synthesis of the final CTP-PBA-ISN was confirmed by HPLC-MASS (Figure S12). The uniformed mass and definite structure guaranteed good stability in quality among different batches. It also avoids complexed blend in of different excipients, which are usually typical for nano-based prodrugs. A non-targeting nCTP-PBA-ISN and a CTP-PBA without NO releasing ability were similarly synthesized as negatively controls, using peptides with scrambled sequence or only HPBA, respectively.

Fig. 1.

Fabrication and characterization of CTP-PBA-ISN. (A) Schematic illustration of synthesis and self-assembly of CTP-PBA-ISN; (B) The DLS profile and TEM image of CTP-PBA-ISN, scale bar 500 nm; (C) ROS triggered drug release via hydrolysis boronate ester and subsequent 1,6-elimination of 4-hydroxybenzyl alcohol carbonate; (D) ROS responsive drug release of CTP-PBA-ISN in PBS and different H2O2 concentrations (10 µM and 1 mM), respectively; and ROS clearance profiles of CTP-PBA-ISN measured by DPPH assay (E) and ABTS assay (F). Data are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 3)

The obtained CTP-PBA-ISN could form spherical nanoaggregates with a diameter of 47 ± 4 nm in aqueous solution, as confirmed by TEM images and DLS results (Fig. 1B). The hydrophobic PBA-ISN, Azido-BA-DPA and DBCO endowed the CTP-PBA-ISN its amphiphilic nature (Fig. 1A), which is the driven force of its self-assembly. The relatively large size may helpful in avoiding premature elimination by renal filtration and extending circulation time [31].

The obtained CTP-PBA-ISN demonstrated The ROS triggered drug release from the PDCs was monitored by the absorbance of HBA. As demonstrated in Fig. 1D, the cumulative release of drugs reached 86.0 ± 3.0% after 24 h incubation with 1 mM of H2O2, while less than 15% of drugs were released in PBS during the same period of time. Due to the enzymatic release nature of NO from ISN, the NO release was tested from cultural medium of cells with or without H2O2 treatment. As indicated in Figure S13, treatment of cells with both H2O2 and CTP-PBA-ISN significantly increased NO concentration. On the other hand, cells without H2O2 treatment only presented with moderated NO release. CTP-PBA-ISN can also eliminate ROS and free radicals in a dose-dependent manner, as indicated by results of ABTS and DPPH assay, respectively (Fig. 1E and F). It should be noted that boronates itself usually do not scavenge free radicals. The radical eliminating effects may come from the resulting byproduct of HBA and re-exposed catechol, after oxidation of boronates (Fig. 1C). Taking together, these results indicated that the CTP-PBA-ISN was potent in scavenging ROS and had ROS-triggered NO release. It laid the foundation for further exploration of the synergic bioeffects of ROS-scavenging and NO releasing.

Cellular uptake of PDCs and evaluation of intracellular OS relief

Firstly, to visualize the uptake of nano-PDCs by cells, a red fluorescent dye, rhodamine B (Rhod B), was labeled on nano-PDCs (RhodB-nano-PDCs). Cells were incubated with RhodB-nano-PDC for different time and observed by fluorescent microscope. As shown in Figure S14A-C, the fluorescence intensity increased over time, indicating that the nano-PDCs can facilitate efficient uptake by both H9c2 cells and HUVECs. To evaluated the biosafety of nano-PDCs, viability of H9c2 cells and HUVECs were measured after 24 h incubation with different treatments. The results of CCK8 assays revealed that all treatments had low cytotoxicity (cell viability ≥ 90%) within a wide range of concentrations (Figure S15). The data demonstrated that the nano-PDCs had desirable biosafety, which is the foundation for future evaluation and applications.

After the occurrence of MI, myocardial ischemia causes the excessive production of ROS [24, 32]. The pathological accumulation of ROS will overwhelm cellular protective counter mechanism, leading to massive oxidative stress (OS) damage [33]. Therefore, effective elimination of ROS is vital in protection of myocytes after MI. Firstly, the ROS eliminating ability of 4-hydroxybenzyl alcohol (4-HBA) was verified on cells treated with H2O2. The intracellular ROS levels were monitored with a DHE assay kit on H2O2 treated H9c2 cells. As demonstrated in Figure S16, 4-HBA could mitigate intracellular ROS in a concentration-dependent manner. Next, the ROS scavenging capacity of different nano-PDCs were tested. As demonstrated in Fig. 2A, all the PDCs effectively reduced the concentration of intracellular ROS, as visualized by much fainter red fluorescence from treated cells. On the other hand, treatment with ISN did not change the level of ROS inside cells (Fig. 2A and B), indicating relatively weak ROS regulating ability of NO. Meanwhile, both ISN and CTP-PBA-ISN significantly increased the intracellular level of NO, as indicated by brighter fluorescence from NO probes (Fig. 2C and D). However, ISN treatment also dramatically elevated the intracellular concentration of peroxynitrite (ONOO−), with the highest RNS level among all the groups (Fig. 2E and F). It vividly demonstrated the ROS induced NO conversion into RNS under OS conditions. On the contrary, the NO releasing CTP-PBA-ISN did not increase the intracellular concentration of RNS (Fig. 2E and F). The difference may arise from the potent ROS scavenging ability of CTP-PBA-ISN. It is worth noting that H2O2 treatment alone can also upregulated intracellular level of RNS, probably via oxidation of intracellular produced NO. Besides, a downregulation of RNS inside cells was also observed in CTP-PBA treated cells, possibly via anti-oxidant mechanisms. The phenomenon confirmed the pathological complexity during OS, and emphasized the necessity of synergic therapy. It proved that our ROS responsive/eliminating strategy was effective in improving cellular viability of NO and minimizing the undesirable generation of RNS.

Fig. 2.

Regulation of intracellular oxidative stress of PDCs in H9c2 cells. (A) Representative images of ROS probe DHE staining after different treatments. Scale bar = 100 μm. (B) Quantification of fluorescence intensity of DHE staining. n = 5. (C) Representative images of NO probe O38 staining after different treatments. Scale bar = 100 μm. (D) Quantification of fluorescence intensity of O38 staining. n = 5. (E) Representative images of RNS probe O58 staining after different treatments. Scale bar = 100 μm. (F) Quantification of fluorescence intensity of O58 staining. n = 5. (G-M) Representative immunoblot image and quantification of the protein expression of Nrf2, HO-1, NQO, TNF-α and IL-6 in H9c2 cells, respectively. n = 3. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001

Furthermore, CTP-PBA-ISN treatment downregulated intracellular expression of Nrf2, HO-1 and NQO-1, all of which are vital hall-markers of cellular OS. It indicated that the combined therapy was effective in countering OS by direct ROS elimination. Apart from direct injury, OS can also provoke the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines from cells, amplifying the damage to the heart. As demonstrated in Fig. 2H and M, the hall-markers of pro-inflammation cytokines, such as TNF-α and IL-6 protein expressions were dramatically upregulated after H2O2 treatment. CTP-PBA-ISN treatment capably reversed such elevation, when other treatments only achieved limited effects. All these data suggested that the ROS-scavenging and NO-releasing CTP-PBA-ISN exerted potent OS relieving effects on cardiomyocytes and attenuating OS related inflammation.

Cellular protection of PDCs

As mentioned above, OS during MI may induce loss of myocytes, which serves as an initiation of detrimental myocardial remodeling. Therefore, the cellular protective effects of PDCs were evaluated. As demonstrated in Figure S17A, H2O2 treatment significantly reduced the viability of H9c2, indicating severe OS injury to the myocytes. CTP-PBA only partially restored the viability of H9c2. However, ISN treatment not only produced no protective effects, but also increased the loss of myocytes. The results were possibly due to the toxic conversion of NO into RNS in oxidative microenvironment. It also demonstrated the limitations of therapies based only on anti-oxidant or NO releasing, respectively. On the contrary, the CTP-PBA-ISN with synergic ROS-scavenging and NO releasing demonstrated potent preservation of cell survival, better than any other treatments. Meanwhile, calcein-AM/PI staining (Fig. 3A and B) and profiles of flowcytometry (Fig. 3C and D) also indicated that CTP-PBA-ISN had the best inhibitory effect on cell apoptosis (apoptosis percentages of 15.6%, 30.0%, 32.2%, 20.3% and 7.6% for CTP-PBA-ISN + H2O2, H2O2, ISN + H2O2, CTP-PBA + H2O2 and PBS treated myocytes). Moreover, western blotting analysis (Fig. 3E and G) demonstrated that CTP-PBA-ISN was the most effective in downregulation of apoptosis proteins (BAX, Caspase3) and upregulation of anti-apoptosis protein (Bcl-2). The results proved that the synergy between PBA and NO indeed maximized cell protective effects on myocytes.

Fig. 3.

Protective effects of PDCs in H9c2 cells. (A) Representative images of calcein AM/PI staining after different treatments. Scale bar = 100 μm. (B) Quantification of dead/live cells from calcein AM/PI staining. n = 5. (C, D) Apoptosis of H9c2 cells analyzed by flow cytometry after different treatments with Annexin V-PI staining. n = 3. (E-G) Representative immunoblot image and quantification of the protein expression of BAX, Bcl-2 and Caspase-3 in H9c2 cells. n = 3. (H) Mitochondrial membrane potential after different treatments was evaluated by JC-10 staining. Scale bar = 100 μm. (I) Relative ratios of red versus green fluorescence intensities from JC-10 staining. n = 5. (J) Mitochondrial ROS level after different treatments was evaluated by MitoSOX staining. Scale bar = 100 μm. (K) Quantification of MitoSOX staining. n = 5. (L) Cytoplasmic calcium level was measured by Fluo-4 AM staining after different treatments. Scale bar = 100 μm. (M) Quantification of Fluo-4 AM staining. n = 5. (N) Representative images of TEM after different treatments. where the white arrows indicate the mitochondria inside the cell. (O) ATP levels in cells. n = 3. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001

Regulation of myocytes’ mitochondria

Mitochondria homeostasis is vital for the function and survival of cardiomyocytes [34, 35]. During MI, overwhelming ROS may initiate mitochondria related calcium dysfunctions, which is the trigger of cellular apoptosis. As mentioned above, CTP-PBA-ISN significantly enhanced the survival of myocytes via inhibiting of apoptosis. Since apoptosis is closely related to mitochondria, it is possible that CTP-PBA-ISN may exerts its protective effects via regulation of mitochondria.

To verify the hypothesis, change in mitochondrial membrane potential, a typical indicator of mitochondrial dysfunction, was first investigated by JC-10 probe. As demonstrated by Fig. 3H and I, cells treated with H2O2 demonstrated obvious depolarization of mitochondria membrane, as indicated by green fluorescence from dispersed JC-10. ISN had negligible influence on the restoration of mitochondrial membrane potential, while CTP-PBA only demonstrated limited effects. On the other hand, CTP-PBA-ISN potently restored the cross-membrane potential of mitochondria in H2O2-treated H9c2 cells, with obvious increase in red fluorescence from aggregated JC-10. Besides, MitoSOX staining also indicated that CTP-PBA-ISN was the most effective in blocking the H2O2-induced overproduction of ROS in mitochondria (Fig. 3J and K). Pathological generation of overwhelming ROS from mitochondria is closely related with stress factors, which is the main cause of aforementioned mitochondrial membrane depolarization and loss of mitochondrial calcium homeostasis [36]. The cytoplasmic calcium level was then monitored by Fluo-4 AM staining. As demonstrated in Fig. 3L and M, calcium concentration in cytoplasm increased remarkably after treatment of H2O2, indicating the possible compromise of mitochondrial homeostasis. CTP-PBA-ISN treatment reversed the abnormal elevation of cytoplasmic calcium level. The results suggested beneficial effects of CTP-PBA-ISN on regulating mitochondrial activities under oxidative stress, which were well in-line with the data of apoptosis inhibition.

It is reported that NO is able to regulate cardiovascular homeostasis by affecting mitochondrial function and energy metabolism of the myocardium during cardiovascular events [37]. However, supplement of NO alone to H2O2 treated myocytes yield limited, if any, protective effects on OS burdened mitochondria (Fig. 3N and O). As mentioned before, overwhelming ROS in the microenvironment may convert NO into detrimental RNS. The reduced NO availability and harmful byproduct may contribute to the failure in present study and many other previous researches. However, the ROS-scavenging CTP-PBA-ISN, which can also release NO in response to ROS, exhibited superior mitochondrial and myocyte rescue effects compared to the ROS scavenging counterpart of CTP-PBA. It also preserved the normal structure of mitochondria under OS shock of H2O2, with less swelling and dissolving of cristae (as indicated by white arrow in Fig. 3N), as well as increased ATP content (Fig. 3O). The difference clearly demonstrated the essentialness of proper regulation of ROS in maximizing biological effects of NO in cell protection and disease relieving.

Preservation of survival and angiogenesis functions of endothelial cells

Apart from direct rescue of myocytes, effective angiogenesis after MI could prevent continuous death of cardiomyocytes in marginal infarct region [38]. However, excessive generation of ROS within the infarcted myocardium causes loss of function and intact of endothelium, delaying or even totally preventing the process of angiogenesis [38, 39]. NO is well-known for its role in enhancing angiogenesis via endothelium repair. Therefore, the in vitro angiogenesis promoting ability of PDCs under ROS-rich conditions were further investigated.

Similar to those of myocytes, calcein-AM/PI staining (Fig. 4A and B) and CCK-8 assay (Figure S17B) revealed that CTP-PBA-ISN treatment was the most effective in maintaining bio-viability and inhibiting apoptosis of human umbilical vessel endothelial cells (HUVECs) under oxidative stress. Meantime, CTP-PBA-ISN can also maximizing intracellular NO delivery (Fig. 4C and E, and Figure S18), while eliminating overwhelming ROS and minimizing RNS generation inside cells.

Fig. 4.

Protective effects of PDCs in HUVECs. (A) Representative images of calcein AM/PI staining after different treatments. Scale bar = 100 μm. (B) Quantification of dead/live cells from calcein AM/PI staining. n = 5. (C-E) Quantification of fluorescence intensity of ROS probe DHE staining, NO probe O38 staining and RNS probe O58 staining. n = 5. (F) Percentage of wound healing area of HUVECs in scratch assay. n = 5. (G) HUVEC migration after different treatments in scratch-wound healing assay. Scale bar = 500 μm. (H) Quantification of migrated HUVECs in Transwell assay. n = 5. (J) Transwell-migrated HUVECs after different treatments stained with crystal violet. Scale bar = 100 μm. (I, K, M) Quantification of tube lengths, branching lengths, and junction numbers. n = 5. (L) HUVEC tube formation after different treatments. Scale bar = 500 μm. (N-P) Representative immunoblot image and quantification of the protein expression of p-eNOS, eNOS and VEGF in HUVECs. n = 3. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001

Proper migration of endothelial cells (ECs) was important for generation of functional new blood vessels. As demonstrated in Fig. 4F and J, H2O2 seriously suppressed the migration of HUVECs, as indicated by slow healing in the scratch assay and less crystal violet staining in transwell assay. On the other hand, CTP-PBA-ISN remarkably attenuated these suppressive effects, restoring HUVECs’ migration to the level similar to those of H2O2-untreated control. In addition, CTP-PBA-ISN also facilitated recovery in pseudopod length, number of junction and degree of branch (Fig. 4I, K and M) of H2O2-treated HUVECs in tube formation assay.

Interestingly, declined expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and ratio of phosphorated endothelial nitric oxide synthetase (p-eNOS/eNOS) under stimuli of H2O2 were remarkably upregulated by treatment of CTP-PBA-ISN (Fig. 4N and P). Both VEGF and p-eNOS/eNOS are vital for the integration and healing of endothelium, which are closely regulated by NO signaling. However, ISN treatment alone barely promoted the H2O2-inhibited migration of HUVECs, nor did it reverse the downregulated expression of angiogenesis-related proteins. As comparison, the ROS-scavenging CTP-PBA and CTP-PBA-ISN was potent in restoring the OS affected functions of ECs. It is worth noting that the NO releasing CTP-PBA-ISN is more effective than CTP-PBA in facilitating angiogenesis-associated activities of HUVECs. These results again demonstrated the necessity of efficient elimination in maximizing the biological effects of NO based therapies.

Accumulation in infarct area and attenuation of OS injury

We then explored the therapeutic effect of PDCs on a mouse model of MI (Fig. 5A). The MI model was established by ligating the left anterior descending artery of heart, which was confirmed by the typical changes of electrocardiogram, with a widened QRS complex and a depressed R-S wave amplitude (Figure S19A). Moreover, Serum markers of myocardial injury, including creatine kinase-MB (CK-MB) and cardiac troponin T (cTnT), were determined at 24 h after MI (Figure S19B and S19C). All these results indicated successful fabrication of the MI model in mice.

Fig. 5.

PDCs ameliorated OS injury post-MI in mice. (A) Schematic illustration of the experimental process. (B) Representative ex vivo fluorescence images and average radiance of sham and MI hearts 2 h and 6 h after intravenous injection of Cy5.5-labeled PDCs. (C, D) Representative images and quantification of fluorescence intensity of DHE staining on day 1 after MI. Scale bar = 50 μm. n = 4. (E, F) Representative images and quantification of fluorescence intensity of O56 staining on day 1 after MI. Scale bar = 50 μm. n = 4. (G-M) Representative immunoblot image and quantification of the protein expression of Nrf2, HO-1, NQO, TNF-α and IL-6 in the heart at 1 days after MI. n = 3. (N, O) Representative images and quantification of TTC staining on day 3 after MI. n = 3. (P, Q) Representative images and quantification of TUNEL positive cells in the infarcted hearts at 3 days after MI. Scale bar = 100 μm. n = 4. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001

Efficient accumulation of drugs in infarct regions was important in maximizing therapeutic outcome and minimizing side effects of NO based therapies, such as hypotension. Therefore, the infarct targeting ability of PDCs were firstly investigated. To visualize the distribution of PDCs in vivo, a near-infrared fluorescent dye Cy5.5 was attached to the CTP-PBA-ISN (Cy5.5-CTP-PBA-ISN), with a PDCs conjugating to peptide with a scrambled sequence of CLSSATKMC(Cyclo) as a non-targeting control (Cy5.5-nCTP-PBA-ISN). As demonstrated in Fig. 5B, infarcted hearts of mice presented bright fluorescent signal 2 h after with injection of Cy5.5-CTP-PBA-ISN via tail veins. The intensity of the fluorescence was still much stronger than that of non-targeting Cy5.5-nCTP-PBA-ISN 6 h after injection, indicating good retention of CTP-PBA-ISN in infarct affected hearts. On the other hand, healthy hearts demonstrated negligible fluorescence. The results confirmed the desirable targeting ability of CTP-PBA-ISN to injured cardiomyocyte. Meanwhile, CTP-PBA-ISN also accumulated in the kidneys, livers, and lungs of sham and MI rats with extended time after injections (Figure S20 and S21). The phenomenon is typical for nano-based materials [40].

Excessive ROS in MI tissue is one of the causes of cardiomyocyte apoptosis [41, 42]. It also dampens the therapeutic effects of NO by converting NO into RNS. As demonstrated in Fig. 5C and D, concentration of ROS in tissue slices of heart significantly elevated after MI operation, as indicated by bright fluorescence from ROS probe of DHE. Treatment of NO donor ISN not only had little effects on tissue abundance of ROS, but also promoted vast generation of RNS (Fig. 5E and F). As a consequence, the level of nitrotyrosine were significantly promoted in heart tissues of NO only treated mice (Figure S22). On the contrary, our PDCs based NO delivery system was the most effective in delivering NO (Figure S23) and eliminating ROS (Fig. 5E) in heart tissue, while generating the least RNS and causing less nitrosation of tyrosine of proteins. Western blot was also performed to detect the expression of OS and inflammation related proteins in the heart after MI injury. The PDCs based NO delivery system demonstrated the most effective OS and inflammation relieving effects, as demonstrated by the significant decrease in the OS proteins (NRF2, HO-1 and NQO-1) and pro-inflammation cytokines (TNF-α and IL-6) after CTP-PBA-ISN treatment (Fig. 5G and M).

As a consequence, the infarct area determined by TTC staining was greatly reduced by CTP-PBA-ISN treatment (Fig. 5N and O). Meanwhile, terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) staining also indicated lowest number of apoptosis cardiomyocytes in the infarcted myocardial tissue after CTP-PBA-ISN therapy (Fig. 5P and Q). The results proved that the ROS responsive PDCs was more efficient in protecting cardiomyocyte via synergy between ROS scavenging and NO releasing.

Preservation of cardiac integrity and functions

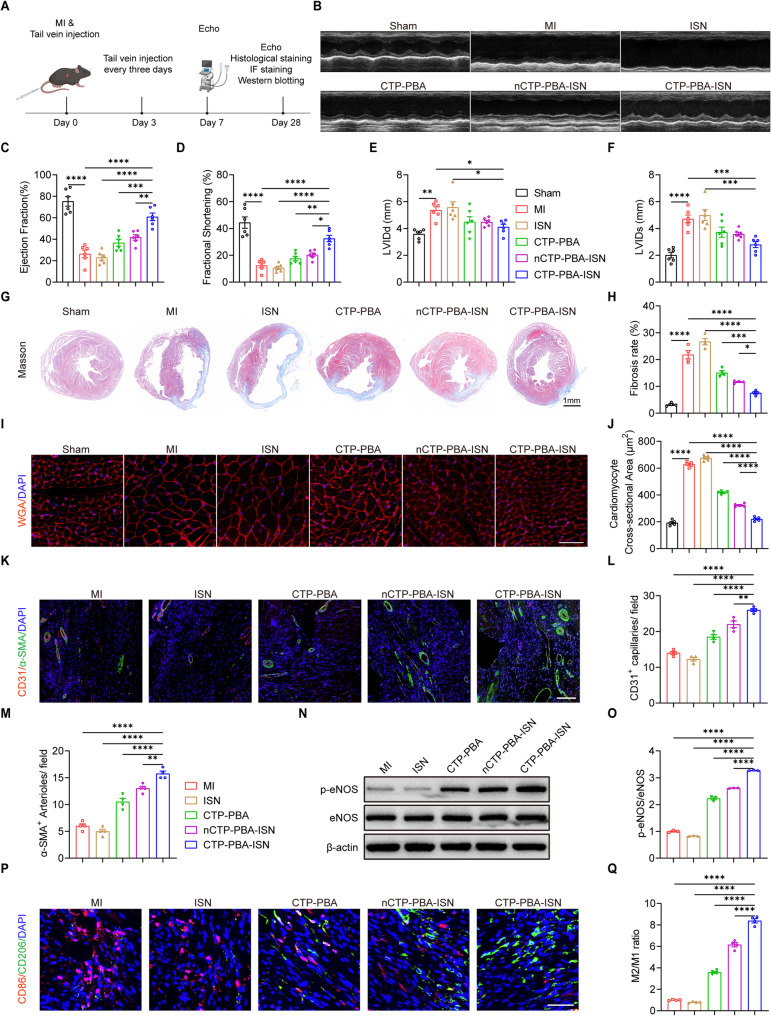

Loss of cardiomyocytes during chronic period of MI inevitably contributed the final heart failure or even death of the patients [43]. Prevention or delay of pathological cardiac remodeling was of great meaning in both maintaining cardiac functions. Meanwhile, decreased ejection fraction (EF), fraction shortening (FS) and increase in left ventricular internal diameter at diastole (LVIDd) and systole (LVIDs) were also developed, as indicated by echocardiographic assessments on 7th and 28th days (Fig. 6B and S24). On the other hand, administration of CTP-PBA-ISN ameliorated these pathological changes in echocardiography (Fig. 6A and F, and Figure S24A-S24E). By contrast, treatments of CTP-PBA or non-cardio-targeting nCTP-PBA-ISN only achieved limited recovery of heart functions and decrease in the myocardial injury hall-markers. Last but not least, ISN barely yielded any therapeutic effects, as demonstrated by negligible change in myocardial contraction. The results clearly demonstrated the limitation of NO based therapy in treatment of MI. It also proved that ROS elimination/responsive NO releasing PDCs could effectively restored myocardial function loss and relieved myocardial injury caused by MI.

Fig. 6.

PDCs improved cardiac function and reduced adverse cardiac remodeling post-MI in mice. (A) Schematic illustration of the experimental procedures. (B) Representative echocardiography images of the hearts of different groups at 28 days after MI. (C-F) Quantification of the EF, FS, LVIDd, and LVIDs of the hearts with different treatments at 28 days after MI. n = 6. (G, H) Representative Masson’s trichrome images and quantification of fibrotic areas of the hearts with different treatments at 28 days after MI. Scale bar = 1 mm. n = 4. (I, J) Representative WGA staining images and quantification of cross-sectional area of cardiomyocytes of the hearts with different treatments at 28 days after MI. Scale bar = 50 μm. n = 5. (K-M2) Representative images and quantification of CD31 (red) and α-SMA (green) immunofluorescence staining of the hearts with different treatments at 28 days after MI. Scale bar = 100 μm. n = 4. (N, O) Representative immunoblot image and quantification of the protein expression of p-eNOS and eNOS in the hearts with different treatments at 28 days after MI. n = 3. (P, Q) Representative CD86 (red), CD206 (green) images and quantification of the ratio of M2/M1 macrophages in the hearts with different treatments at 28 days after MI. Scale bar = 50 μm. n = 4. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001

Cardiac remodeling will seriously impair the contraction of the heart and is the leading cause of heart failure after MI [44, 45]. As demonstrated in Fig. 6G and H, massive remodeling of cardiac tissue was observed in MI mice on 28th days after operation, as indicated by extensive replacement of myocytes by fibroblasts in infarct area. An increase in cross-sectional area of cardiomyocytes was also visualized by WGA staining, which is the typical character of ventricular contractile dysfunctions after MI (Fig. 6I and J). However, MI mice with CTP-PBA-ISN treatment presented with the reduced fibrotic area and increased infarct wall thickness (Figure S25), exhibiting superior therapeutic outcomes among all the groups. The less ventricular remodeling was accompanied by smaller cross-sectional area of cardiomyocytes, similar to those of healthy mice. It indicated the potent inhibition of pathological cardiac remodeling by CTP-PBA-ISN.

Apart from direct protection of myocytes, revascularization is also of great significance, especially for myocytes in the junctional area. The resupply of nutrient and oxygen may accelerate tissue repair in ischemic myocardium after MI tissue [38]. As demonstrated in Fig. 6K and M, angiogenesis in the border zone of infarct region was greatly promoted by the treatment of CTP-PBA-ISN, as confirmed by increase in density of CD31 positive (CD31+) capillaries and α-SMA positive (α-SMA+) arterioles. However, the NO releasing ISN didn’t have any effects of neovascularization in the border zone of infarct area. The contrast implied that the pro-angiogenesis effects may be attributed to the activities of NO after sufficient ROS scavenging. And the results were further confirmed by the protein level of phosphorated eNOS (p-eNOS), the active form of eNOS, after CTP-PBA-ISN administration (Fig. 6N and O).

Interestingly, phenotypes of macrophages were also altered after treatments. Macrophages are pivotal players in MI and participate in the angiogenesis process for myocardial tissue repair [46]. The pro-inflammatory M1 types exacerbate tissue injury and inhibit revascularization, while the anti-inflammatory M2 types promote angiogenesis [47, 48]. As demonstrated in Fig. 6P and Q, an increased ratio of CD86 positive (red) over CD 206 positive (green) macrophages indicated the infiltration of M1 type macrophages after MI. The results were in line with the suppressed angiogenesis after MI. Fortunately, treatment of CTP-PBA-ISN reversed the trends and established a M2-dominant macroenvironment. The unexpected shift in ratio of M1 over M2 may be attributed to the aforementioned downregulation of immune-chemokines (TNF-α and IL-6) by the PDCs.

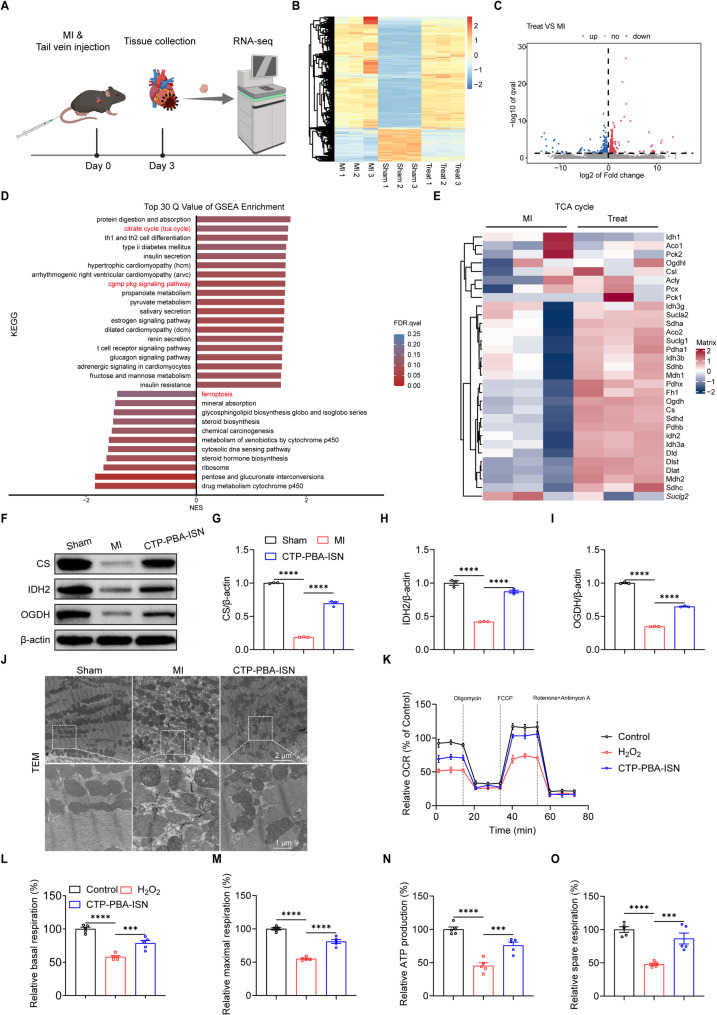

Exploration of therapeutic mechanism of PCDs

RNA-seq analysis of heart tissues with different treatments (Sham, MI and CTP-PBA-ISN) was performed to further explore the mechanism underlying the protective effects of CTP-PBA-ISN against MI (Fig. 7A). Hierarchical clustering analysis of the mRNA expression across the whole transcriptome indicated substantial changes in gene signatures between MI and MI with CTP-PBA-ISN groups (Fig. 7B), with 318 genes up-regulated and 207 genes down-regulated by the therapy (|Log2FC| ≥ 0, P.adj ≤ 0.05; Fig. 7C). Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) (Fig. 7D and Figure S26) revealed that treatment with CTP-PBA-ISN upregulated tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, cGMP-PKG signaling as well as cardiac muscle contraction pathway. It also suppressed ferroptosis related signaling. Specifically, the enrichment of the cGMP-PKG signaling pathway indicated that treatment of CTP-PBA-ISN directly affect the NO signal activation step, possibly via NO induced activation of sGC. The upregulated TCA pathway implied that CTP-PBA-ISN treatment improved the energy metabolism of myocytes during MI. Furthermore, the DEGs in the TCA cycle pathway were visually displayed by a heat map. As demonstrated in Fig. 7E, CTP-PBA-ISN treatment upregulated the gene expression of hall-marker enzymes in the TCA cycle, including three key rate-limiting enzymes in mitochondrial metabolism: citrate synthase (CS), isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH2), and alpha ketoglutarate dehydrogenase (OGDH).

Fig. 7.

RNA-seq analysis of the molecular mechanism of myocytes protection. (A) Schematic illustration of the experimental process. (B) Hierarchical clustering and heatmap of DEGs in hearts determined by RNA-seq of Sham, MI, and MI + CTP-PBA-ISN groups. (C) Volcano plot of differentially expressed genes between MI and CTP-PBA-ISN treated group. (D) GSEA analysis of significantly up- and down-regulated genes of KEGG database. (E) Heatmaps of DEGs in TCA cycle pathway. (F-I) Representative immunoblot image and quantification of the protein expression of CS, IDH2 and OGDH in the heart at 3 days after MI. n = 3. (J) The ultrastructure of myocardial mitochondria observed by TEM in the heart at 3 days after MI. (K-O) Mitochondrial OCR after different treatments was evaluated by seahorse XFe96 analyzer in primary cardiomyocytes. n = 5. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001

To further verify the enhancement in mitochondria functions by CTP-PBA-ISN, protein expressions of CS, IDH2, and OGDH were examined in the heart tissues collected from mice at 3 days after MI (Fig. 7F and I). The results indicated that CPT-PBA-ISN facilitated recovery of these downregulated mitochondria related rate-limiting enzymes after MI.

As afore-demonstrated, CTP-PBA-ISN was able to retain the potential of mitochondria membrane, inhibiting detrimental generation of overwhelming ROS and abnormal flux of Ca2+ (Fig. 3H and M) in cell experiments in vitro. These effects were beneficial in retaining the structure integration (Fig. 3N). Similarly, treatment of CTP-PBA-ISN ameliorated myocardial fiber rupture, mitochondrial damage and increased mitochondrial numbers in TEM images of tissue slices (Fig. 7J). It confirmed the desirable preservation of mitochondria structure by CTP-PBA-ISN in vivo.

Finally, to verify the improvement of mitochondria functions by CTP-PBA-ISN, seahorse stress test was then carried out to evaluate oxygen consumption rate (OCR) of mitochondrial respiration in primary cardiomyocytes, which is a key parameter reflecting mitochondrial function. As shown in Fig. 7K and O, the basic respiration, maximal respiration, ATP production and spare respiration capacity were substantially decreased in NRVCMs treated with H2O2. However, CTP-PBA-ISN treatment significantly reversed the pathological respiratory inhibition. The results confirmed the restoration in mitochondria function by CTP-PBA-ISN treatment.

As aforementioned, myocytes are highly sensitive to the changes in energy supply, because of their high level of metabolic activities. MI will cause serious mitochondria dysfunctions, rendering energy deficiency in myocyte. These factors lead to the loss of myocytes and chronic remodeling after MI. CTP-PBA-ISN facilitated mitochondria protection and function preservation via OS relief and maximizing NO bioavailability, which may contribute to its favored therapeutic outcome on MI.

Safety evaluation of NPs in vivo

The biocompatibility and safety of PDCs in vivo are important factors in drug design and development. To this end, changes in the anatomical structure of liver, spleen, lung and kidney were thoroughly evaluated by hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining after 28-day continuous administration of different PDCs. As shown in Figure S27, negligible histopathological changes were noted in these organs. Moreover, hematologic parameters of white blood cell (WBC), monocyte (Mon), neutrophil (Neu), platelet (PLT), red blood cell (RBC), hemoglobin (HGB), hematocrit (HCT), as well as the liver function indicators of alanine transaminase (ALT), aspartate transaminase (AST) and the kidney function indicators of creatinine (CRE) and urea nitrogen (BUN) revealed that CTP-PBA-ISN exerted no significant alternations compared to sham group (Figure S28). Taken together, these data confirmed that the PDCs had negligible toxicity and good biosafety in vivo.

Conclusion

In summary, a ROS-responsive peptide-drug conjugate (PDC) CTP-PBA-ISN was successfully produced. The facile conjugation of targeting peptides (CTP) via two pairs of orthogonal reactions enhanced selective accumulation of drugs at myocardial infarction (MI) site. Upon the stimulation of pathological ROS, NO prodrug was released via fast hydrolysis of boronate ester, while the anti-oxidant 4-hydroxybenzyl alcohol (HBA) as a beneficial by-product further scavenged the harmful ROS. The mitigated oxidative stress not only inhibited myocytes injury, but also reduced the toxic generation of RNS, a key factor for the failure of conventional NO based therapy. The synergic protective effects of ROS elimination and NO regulation effectively restored mitochondria homeostasis of oxidative stress affected myocytes and promoted angiogenesis via NO related signaling pathways. Therefore, the CTP-PBA-ISN treatment significantly ameliorated cardiac damage, inhibited myocardial apoptosis, suppressed adverse cardiac remodeling, and improved myocardial function post-MI, with negligible systemic toxicity after long term administration. We believed that the present our strategy not only but also provided new solution for innovative NO-based interventions for in ischemic heart disease.

Materials and methods

Materials

All chemicals are obtained and used without further purification, unless stated. Dibenzocyclooctyne (DBCO) conjugated cyclo-peptides were obtained from Suzhou Motif Biotech Co., Ltd. BBoxiProbe® DHE, BBoxiProbe® O56, BBoxiProbe® O58, BBoxiProbe® O38 were purchased from Bestbio. Nrf2 (A0674, 1:1000 for Western blot), β-Actin (AC026, 1:80000 for Western blot), IL6(AC026, 1:1000 for Western blot) were purchased from ABclonal. HO-1 (10701-1-AP, 1:1000 for Western blot), NQO-1 (67240-1-Ig, 1:5000 for Western blot), BAX (50599-2-Ig, 1:2000 for Western blot), Bcl2 (68103-1-Ig, 1:5000 for Western blot), Caspase 3 (19677-1-AP, 1:500 for Western blot), CS (16131-1-AP, 1:2000 for Western blot), OGDH (15212-1-AP, 1:5000 for Western blot), IDH2 (15932-1-AP, 1:500 for Western blot) were purchased from proteintech. TNF-α (GB11188-100, 1:500 for Western blot), VEGFA (GB11034B-100, 1:1000 for Western blot) were purchased from Servicebio. CD31 (ab222783, 1:100 for IF), eNOS (phospho S1177) (ab215717, 1:1000 for Western blot) were purchased from abcam. CD206 (24595, 1:200 for IF), eNOS (32027, 1:1000 for Western blot) were purchased from CST. CD86 (NBP2-25208, 2 ug/ml for IF) were purchased from Novus. Calcein-AM/PI, Fluo-4 AM, ATP assay kit were purchased from Beyotime. The Annexin V-FITC/PI, MitoSOX were purchased from YEASEN. JC-10 were purchased from Solarbio. CCK-8 were purchased from Meilunbio. Celltracker dyes (C2925), Wheat Germ Agglutinin (W11262) were purchased from Thermo Fisher. TTC (T8877), α-SMA (A5228, 1:3000 for IF) were purchased from sigma. The TUNEL (12156792910) was purchased from Roche. Matrigel Matrix was purchased from Corning. Mouse cTnT ELISA Kit (ml037292) and Mouse CK-MB ELISA Kit (ml037723) were purchased from Mlbio.

Synthesis of PBA-ISN

5-isosorbide mononitrate (ISN, 0.01 mol; 1.91 g) was added to 50 mL dichloride methane (DCM) in a 100 mL flask with a magnetic stir. 1,1’-Carbonyldiimidazole (CDI, 0.02 mol; 3.24 g) was slowly dropped to the solution with vigorously stirring. The reaction was left at room temperature (25 ℃) overnight, extracted with water, aqueous hydrochloride (0.01 M) and saturated NaHCO3 solution, respectively. The organic layer was collected, combined and washed with brine, dried over anhydrous Na2SO4. The product ISN-CDI was collected after rotated evaporation under vacuum, yielding 2.8 g (98.5%). CDCl3 for 1H NMR and 13C NMR. CH3CH2OH for quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry (cation).

ISN-CDI (0.007 mol; 2.00 g) and 10 mL DCM were added in a 50 mL flask with a magnetic stir. 4-(Hydroxymethyl) phenylboronic acid pinacol ester (PBAP, 0.0073 mol; 1.7 g) and 4-Dimethylaminopyridine (DMAP, 0.005 mol; 0.61 g) were dissolved in the solution. The solution was kept at 45 ℃ with stirring for 36 h. The solution was cooled to room temperature and concentrated to minimum volume. The purified product of PBAP-ISN was obtained by flush chromatography (EA: PE = 3:7 − 5:5), yielding 2.53 g (81.1%). CDCl3 for 1H NMR and 13C NMR. CH3CH2OH for quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry (cation).

2.53 g PBAP-ISN (0.0057 mol) was dissolved in 5 mL N, N-dimethylformamide (DMF). Diethanolamine (DEA, 0.0057 mol; 0.6 g) was added to the solution with stirring. The mixture was kept at room temperature (25 ℃) for 6 h. The white precipitates were collected by filtration, and washed with ethyl acetate (EA) and ether to obtain the product of DEA-PBA-ISN. Yielding 1.89 g (86.3%). d6-DMSO for 1H NMR and 13C NMR. CH3CH2OH for quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry (cation).

1.00 g DEA-PBA-ISN (0.0023 mol) was dispersed in 5 mL 1 M HCl aqueous solution. The mixture was stirred at room temperature (25 ℃) for 2 h. The precipitate was separated by centrifuge, and washed with Miliq water. The resulting solid was lyophilized to yield 0.71 g (84.2%). d6-DMSO for 1H NMR and 13C NMR. CH3CH2OH for quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry (anion).

Synthesis of azido-BA-DPA

0.8 g 4-azidobenzoic acid (azido-BA, 0.005 mol) and 0.95 g dopamine hydrochloride (DPA · HCl, 0.005 mol) were dissolved in 10 mL DMF, to which 1.92 g 1-(3-Dimethylaminopropyl)-3-ethylcarbodiimide hydrochloride (EDCl, 0.01 mol) and 1.35 g 1-Hydroxybenzotriazole (HOBT, 0.01 mol). The reaction was kept at room temperature (25 ℃) for 48 h. Most DMF was removed by rotated evaporation under vacuum. The residue was dissolved in EA and the precipitate was removed. The organic solution was washed with excessive HCl aqueous solution and water, dried over anhydrous Na2SO4. The volume of the solution was reduced to minimum and subjected to flush chromatography (EA: PE = 3:7). The product of Azido-BA-DPA was obtained by rotated evaporation under vacuum as a white solid. Yielding 1.54 g (51.7%). d6-DMSO for 1H NMR and 13C NMR. CH3CH2OH for quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry (cation).

Preparation and characterization of different PDCs

DBCO conjugated cyclo-peptides, Azido-BA-DPA and PBA-ISN (molar ratio 1: 1: 1) were dissolved in DMF under argon. The bottle was sealed and kept at 45 ℃ overnight. The resulting PDCs were obtained by precipitation in ethyl ether and dried in vacuum. The products were analyzed by high performance liquid chromatography (ThermoFisher U3000) equipped with a mass spectrum detector (ThermoFisher Orbitrap Eclipse). PBA-ISN was replaced by 4-(Hydroxymethyl)phenylboronic acid (PBA) to fabricate the ROS-responsive/eliminating PDCs without NO releasing ability, in the same procedures. Rhodamine B (Rhod B) isothiocyanate and were used to labeled the PDCs. In a standard case, the PDC was kept in the dark with the fluorescent dye in DMSO at room temperature overnight. The resulting solution was diluted with Miliq water. The mixture was thoroughly dialyzed against water, until the fluorescence in the sheath fluid was undetectable. The resulting liquid was lyophilized in the dark to obtain the corresponding the fluorescent dyes conjugated PDCs. Normalization was performed by UV-Vis spectrometer before use, for the guarantee of same fluorescence intensity among different solutions.

Quantification of ROS triggered drug release

To test responsive drug release behavior, CTP-PBA-ISN was placed into dialysis chamber, which was incubated with 5 mL PBS with or without 1 mM H2O2 at 37℃ with shaking at 125 rpm. At pre-set time points, the release solution was harvested for UV quantitative detection. To test the NO release from PDCs, PDCs (10 µM) was incubated with cells pre-treated with PBS and H2O2 for 24 h. The NO release at 0 h and 24 h were detected by Griess assay, respectively.

Evaluation of ROS scavenging ability

The ROS eliminating ability of PDCs was evaluated by 2,2’-azino-bis (3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) (ABTS) and 2,2-diphenyl-1- picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) assay. Briefly, 75 µl DPPH (500 µM) was mixed with 25 µl solution with different concentration of PDCs (0, 5, 10, 25, 50, 100 and 200 µM). The mixed solution was incubated in darkness for 30 min. Finally, the absorbance at 517 nm was recorded and scavenged DPPH was calculated. The ABTS assay was performed under the standard instruction of the test kit.

Cell culture

The H9c2 cells were cultured in high-glucose Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% FBS. HUVECs were cultured in specific Endothelial cell medium with 5% FBS and growth factor supplements purchased from ScienCell Research Laboratories, Inc. (San Diego, CA, USA). Isolation and culture of neonatal rat primary cardiomyocytes was performed as described previously [49]. Briefly, heart tissues of neonatal Wistar rats were dissociated with trypsin and cells were plated for 1 h into tissue culture dishes in DMEM with 10% FBS to reduce the number of nonmyocytes. Cells that did not attach to the plates were aspirated and plated into 6-well culture plates. Primary cardiomyocytes were cultured in the same growth medium as H9C2 cells.

Evaluation of cellular uptake of PDCs

H9c2 cells (1 × 106 per well) were seeded in 6-well plates and cultivated for 24 h. Rhodamine B labeled PDCs were then added to the wells and co-incubated with cells for different 0, 2, 4, 6, and 8 h, respectively. Afterwards, medium was removed and the cells were washed with PBS. Cells were digested by Trypsin for tests on flow cytometry (BD FACS-CaliburTM). For fluorescence photographs, the nucleis were stained with Hoechst 33,258 and the images were acquired by fluorescence microscope.

Cell viability assay

HUVECs (5 × 103 per well) and H9c2 cells (5 × 103 per well) were cultured in 96-well plate for 24 h. The medium was refreshed with different drugs (10 µM equivalent of PBA or/and ISN). And then, the cells were stimulated with 500 µM H2O2 with PBS as control. After 24 h, fresh cultural medium with 10% CCK-8 reagents were added and the cells were incubated for another 4 h. The absorbance of the supernatant at 450 nm was measured to calculate the cell viability.

HUVECs (1 × 105/well) and H9c2 cells (1 × 105/well) were seeded in 24-well plates for 24 h. After different treatments for 24 h, the cells were stained for 30 min according to the standard procedures of live/death kit. Then, the images of cells were taken by fluorescence microscope.

Measurement of intracellular ROS, NO and ONOO- levels in vitro

To determine the levels of intracellular ROS, NO and ONOO−, cells were seeded and cultured for 24 h. After being treated with different drugs for 4 h, cells were stained with fluorescent probes (BBoxiProbe® DHE for ROS tests, BBoxiProbe® O38 for NO tests and BBoxiProbe® O58 for ONOO− tests), respectively. Then, the images were captured by fluorescence microscopy, and the mean fluorescence intensities were measured by Image J Software to compare the intracellular ROS, NO and ONOO− levels.

Evaluation of mitochondria-related cell injury and cellular ATP

H9c2 cells were seeded and cultured for 24 h. After different treatments for 6 h, cells were stained with different fluorescent probe (JC-10 for tests of mitochondrial membrane potential, MitoSOX for tests of mitochondrial ROS probe and Fluo-4 AM for tests of cytoplasmic calcium), respectively. Then, the images were captured by fluorescence microscopy, and the mean fluorescence intensities were by Image J Software to demonstrate changes in the mitochondrial membrane potential, mitochondrial ROS and cytoplasmic calcium.

The cell apoptosis evaluation was performed by the Annexin V-FITC/PI Kit. Briefly, H9c2 cells were seeded and incubated in 6-well plates for 24 h. After different treatments for 24 h, the cells were harvested and stained according to the instructions of apoptosis kit. The stained cells were quantified by flow cytometric analysis. The cellular ATP levels were determined using an enhanced ATP assay kit (Beyotime, S0027).

Mitochondria observation of ultrathin sections in TEM

For TEM analysis, H9c2 cells or cardiac tissue were harvested, fixed overnight with 2.5% glutaraldehyde solution and dehydrated by ethanol with gradient concentrations (50%, 70%, 90% and 100%). The resin embedded samples were cut into ultrathin slices, stained with osmium tetroxide (1%) for 1 h at room temperature. Images were taken and analyzed by transmission electron microscope (TEM).

Migration and tube formation of HUVECs

The migration ability of HUVECs was determined by Wound healing and Transwell assay. For wound healing assay, HUVECs were pre-stained with green fluorescent dye and cultured in 6-well plates to a 100% confluent monolayer. A gap of scratch was created by the tip of 200 µL pipette. After treated with fresh medium containing different PDCs and drugs, images of the scratches were captured at 0 h and 24 h by fluorescence microscopy. For Transwell assay, Boyden Chamber and the Costar Transwell apparatus with 8.0-µm pore size was employed. HUVECs (8 × 104 per well) were seeded in the upper chambers with serum-free medium. The lower chamber was filled with medium containing 10% FBS and different drugs. After 8 h incubation, migrated cells were stained with 0.1% crystal violet and captured by an optical microscope. Five randomly fields were taken to count the number of migrated cells by Image J software.

For tube formation assay, HUVECs (2.5 × 104 per well) were seeded into Matrigel matrix coated 96-well dishes. After adding different reagents and incubating for 6 h, the graphs were captured by an optical microscope and quantified by Image J software from five randomly selected fields.

Western blotting

The cells and heart tissues were lysed by lysate buffer and the protein content was quantified by BCA protein detection kit. Then, equal amounts of cells/ tissues proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE gel electrophoresis followed by being transferred to PVDF membranes. After blocking with 5% non-fatted milk, incubating with primary antibodies and corresponding secondary antibodies, the bands were obtained by chemiluminescence using ECL detection reagent and analyzed by Image J software.

Experimental animals, MI model establishment

All animal experiments were carried out according to the guides of Care and Use of laboratory animals of Animal Care and Use Committee, Zhejiang Academy of Medical Sciences. Healthy male C57BL/6 mice (10-week-old) male were purchased from the animal center of Zhejiang Academy of Medical Sciences. Mice were randomly divided into six groups: (1) Sham-operated group (Sham), (2) myocardial infarction group (MI), (3) NO treatment group (ISN), (4) anti-oxidant treatment group (CTP-PBA), (5) nontargeting ROS responsive NO treatment group (nCTP-PBA-ISN) and (6) targeting ROS responsive NO treatment group (CTP-PBA-ISN). The mice were intravenously administrated with saline (MI group) or ISN, CTP-PBA, nCTP-PBA-ISN and CTP-PBA-ISN (200 µg/kg equivalent of ISN and 159 µg/kg equivalent of PBA) via tail veins immediately after surgery and every three days for a total of four weeks. The mice were then euthanized. Blood samples and major organs were harvested for histological analysis.

To establish the MI model, the mice were anesthetized with a 2% isoflurane inhalation, and ventilated and intubated with the help of a rodent ventilator. Under aseptic conditions, the heart was exposed by a left thoracotomy, and the left anterior descending (LAD) coronary artery was permanently ligated with a 6 − 0 silk suture to create myocardial infarction (MI). The presence of myocardial blanching in the heart was considered the cardiac ischemia. The chest was closed and skin was then suture. Electrocardiograms (ECGs) were captured by the Vevo 1100 system to further confirm the successful establishment of the MI. All procedures were performed on the mice in the sham group, without ligating the LAD.

Determination of cTnT and CK-MB

To evaluate the protective effect of PDCs on the myocardial enzyme spectrum, blood samples were collected from mice 24 h after MI injury. The serum was obtained by centrifugating blood samples (3000 rpm, 10 min). The concentration of cTnT and CK-MB (indicators of myocardial injury) were determined using a Mouse cTnT ELISA Kit and a CK-MB detection Kit, according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

In vivo distribution and pharmacokinetics of PDCs

To determine in vivo distribution of PDCs in major organs, sham and MI mice were intravenously injected with Cy5.5-labeled PDCs via tail vein. At 2 h and 6 h after injection, the animals were euthanized, and hearts, lungs, livers, spleens and kidneys were harvested for fluorescence imaging using an IVIS Spectrum System (Perkin Elmer). For pharmacokinetics, healthy C57BL/6 mice were randomly injected with Cy5.5-labeled PDCs. At 10 min, 0.5 h, 1 h, 2 h, 4 h, 6 h, 8 h, 16 h and 24 h, the subjects were sacrificed and blood samples were collected (500 µL each animal). Then, the blood was centrifuged at 2000 rpm for 15 min to obtain serum. Then, the fluorescent signals of PDCs were measured with a fluorescence microplate reader.

Echocardiograph

Transthoracic echocardiograph was conducted on a Vevo 1100 system (VisualSonics Inc.) equipped with a 30 MHz ultrasound transducer. Briefly, mice were anesthetized with 2% isoflurane inhalation and fixed on a warming pad. The cardiac function parameters of ejection fraction (EF), fraction shortening (FS), left ventricular end-systolic diameter (LVIDd), left ventricular end-diastolic diameter (LVIDs), and from the M-mode of the echocardiograms were recorded at days 7 and 28 after MI surgery.

Triphenyl tetrazolium chloride (TTC) staining

The animals were euthanized before hearts were dissected and perfused with PBS. Then, the hearts were frozen at − 80 °C for 20 min and sliced vertically along its long axis into 5 sections. Subsequently, the slices were incubated with 2% TTC solution at 37 °C in the dark for 20 min. Following the incubation, slices were rinsed with PBS and immersed with 4% PFA for 24 h. Digital images were captured and the infarction area was quantified by ImageJ software.

Histological assessment

At pre-set time points, the animals were sacrificed and hearts were collected. After being perfused with cold PBS, hearts were immersed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 24 h. Then, the samples were dehydrated in ethanol with gradient concentrations, embedded in paraffin and serially cut into 5 μm slices. Subsequently, hematoxylin-eosin (H&E) staining and Masson stating were performed and imaged to evaluate the morphology and myocardial fibrosis. The fibrosis area and wall thickness were quantified from digital images by Image J software.

Immunofluorescence staining

The ROS, NO and ONOO− probes were used to estimate the levels of ROS, NO and ONOO− in the myocardial tissue region 24 h after MI. To estimate the peroxynitrite in the myocardial tissue region, the sections were incubated with the primary antibody of nitrotyrosine. TUNEL kit was employed to determine the apoptosis in the myocardial tissue region 3 days after MI. To evaluate the cardiomyocyte hypertrophy in the myocardial tissue region 28 days after MI, the sections were incubated with the primary antibody of WGA. To estimate the angiogenesis in the myocardial tissue region, the sections were incubated with the primary antibody of CD31 and α-SMA, respectively. To determine the inflammation infiltration of macrophages in the myocardial tissue region, the sections were incubated with primary antibodies of CD206 and CD86, respectively. And the aforementioned sections were labeled with species-specific secondary antibodies. The images were captured by fluorescence microscope and analyzed using Image J software.

RNA sequencing analysis

Total RNA was harvested from cardiac tissue of mice in the infarcted zone of the MI, ISN, CTP-PBA, nCTP-PBA-ISN and CTP-PBA-ISN treated groups using TRIzol (thermofisher, 15596018). After enrichment and purification of the obtained mRNA, Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer was used to estimate the total concentration of mRNA for normalization. Subsequently, these mRNA were sequenced on an Illumina Novaseq 6000 platform. Differentially expressed gene (DEG) analysis was performed by using the edgeR package. Gene set enrichment analysis was performed using software GSEA (v4.1.0) and MSigDB.

Mitochondrial function assessment by seahorse analyzer

Mitochondrial respiration oxygen consumption rate (OCR) was detected by a Seahorse XFe96 analyzer (Agilent, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Primary cardiomyocytes (2 × 103 per well) were seeded into Seahorse XFe96 microplates for 24 h, the culture medium was replaced with Seahorse detection solution containing glucose (10 mM), pyruvate (1 mM) and Glutamine (2 mM) for 1 h. The OCR was detected by adding oligomycin (1 µM), FCCP (1 µM), antimycin A (1 µM) and rotenone (1 µM). Data was analyzed using Seahorse Wave software.

Safety assessment in vivo

To determine the safety of drugs, blood samples and major organs were collected. The level of hematologic parameters and classical indicators of hepatic and kidney functions were tested. The major organs were harvested, sliced and stained with H&E. The digital images were taken and analyzed.

Statistical analysis

All data were expressed as mean ± SEM and analyzed with GraphPad Prism (v9.0). The two-tailed Student’s t test is used for comparing differences between two groups. And one-way ANOVA analysis with Tukey’s post hoc tests were employed to compare three or more groups. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Testing and Analysis Center of the Department of Polymer Science and Engineering and Chemistry Instrumentation Center Department of Chemistry Zhejiang University for help in testing. All animal experiments were approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Zhejiang Academy of Medical Sciences (Approval No. ZJCLA-IACUC-20010693).

Author contributions

ZL, QC and WD contributed equally to this work. ZL: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Writing & editing. QC: Methodology, Investigation, Data curation. WD: Methodology, Investigation, Data curation. BY: Methodology. QL: Methodology. FQ: Methodology, Funding acquisition. JG: Methodology. JZ: Methodology, Funding acquisition. XS: Methodology. SC: Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition. ZS: Investigation, Funding acquisition. MS: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition. WZ: Conceptualization, Methodology, Funding acquisition. GF: Supervision, Conceptualization, Funding acquisition. QJ: Writing & editing, Methodology, Conceptualization. YZ: Supervision, Writing & editing, Methodology, Conceptualization. FJ: Conceptualization, Supervision, Methodology, Writing & editing, Funding acquisition. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (22305219, 82270262, 82200271, 82311530688, 82401857), the Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province, China (2024C03025; LY23H020006, LY24H020001) and Traditional Chinese Medicine Science and Technology Project of Zhejiang Province (2025ZS022; 2022ZZ022).

Data availability

All data are available in the main text and the Supporting Information, or at any proper requests from the authors.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All animal experiments were approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Zhejiang Academy of Medical Sciences (Approval No. ZJCLA-IACUC-20010693).

Consent for publication

All authors agree to be published.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Zhaoyang Lu, Quanyou Chai and Wenbin Dai contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Qiao Jin, Email: jinqiao@zju.edu.cn.

Yanbo Zhao, Email: zhaoybzju@zju.edu.cn.

Fan Jia, Email: jiafan@zju.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Sadahiro T, Yamanaka S, Ieda M. Direct cardiac reprogramming: progress and challenges in basic biology and clinical applications. Circ Res. 2015;116:1378–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ji X, Chen Z, Wang Q, Li B, Wei Y, Li Y, Lin J, Cheng W, Guo Y, Wu S, et al. Sphingolipid metabolism controls mammalian heart regeneration. Cell Metab. 2024;36:839–e856838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nguyen NUN, Canseco DC, Xiao F, Nakada Y, Li S, Lam NT, Muralidhar SA, Savla JJ, Hill JA, Le V, et al. A calcineurin-Hoxb13 axis regulates growth mode of mammalian cardiomyocytes. Nature. 2020;582:271–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Da Dalt L, Cabodevilla AG, Goldberg IJ, Norata GD. Cardiac lipid metabolism, mitochondrial function, and heart failure. Cardiovasc Res. 2023;119:1905–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.She P, Gao B, Li D, Wu C, Zhu X, He Y, Mo F, Qi Y, Jin D, Chen Y, et al. The transcriptional repressor HEY2 regulates mitochondrial oxidative respiration to maintain cardiac homeostasis. Nat Commun. 2025;16:232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nah J, Fernandez AF, Kitsis RN, Levine B, Sadoshima J. Does autophagy mediate cardiac myocyte death during stress?? Circ Res. 2016;119:893–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murray CJL. The global burden of disease study at 30 years. Nat Med. 2022;28:2019–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McLaughlin S, McNeill B, Podrebarac J, Hosoyama K, Sedlakova V, Cron G, Smyth D, Seymour R, Goel K, Liang W, et al. Injectable human Recombinant collagen matrices limit adverse remodeling and improve cardiac function after myocardial infarction. Nat Commun. 2019;10:4866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen G, Gan J, Wu F, Zhou Z, Duan Z, Zhang K, Wang S, Jin H, Li Y, Zhang C, Lin Z. Scpep1 Inhibition attenuates myocardial infarction-induced dysfunction by improving mitochondrial bioenergetics. Eur Heart J 2025;00:1–16. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Wang Y, Leifheit EC, Krumholz HM. Trends in 10-Year outcomes among medicare beneficiaries who survived an acute myocardial infarction. JAMA Cardiol. 2022;7:613–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Farah C, Michel LYM, Balligand JL. Nitric oxide signalling in cardiovascular health and disease. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2018;15:292–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carlstrom M, Weitzberg E, Lundberg JO. Nitric oxide signaling and regulation in the cardiovascular system: recent advances. Pharmacol Rev. 2024;76:1038–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heusch G. Myocardial ischaemia-reperfusion injury and cardioprotection in perspective. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2020;17:773–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cohen MV, Yang XM, Downey JM. Nitric oxide is a preconditioning mimetic and cardioprotectant and is the basis of many available infarct-sparing strategies. Cardiovasc Res. 2006;70:231–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang J, Wang S, Sun Q, Zhang J, Shi X, Yao M, Chen J, Huang Q, Zhang G, Huang Q, et al. Peroxynitrite-Free nitric oxide-Embedded nanoparticles maintain nitric oxide homeostasis for effective revascularization of myocardial infarcts. ACS Nano. 2024;18:32650–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhu D, Hou J, Qian M, Jin D, Hao T, Pan Y, Wang H, Wu S, Liu S, Wang F, et al. Nitrate-functionalized patch confers cardioprotection and improves heart repair after myocardial infarction via local nitric oxide delivery. Nat Commun. 2021;12:4501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kalyanaraman H, Ramdani G, Joshua J, Schall N, Boss GR, Cory E, Sah RL, Casteel DE, Pilz RB. A novel, direct NO donor regulates osteoblast and osteoclast functions and increases bone mass in ovariectomized mice. J Bone Min Res. 2017;32:46–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ho EC, Parker JD, Austin PC, Tu JV, Wang X, Lee DS. Impact of nitrate use on survival in acute heart failure: A Propensity-Matched analysis. J Am Heart Assoc 2016;5:e002531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Nunes AP, Seeger JD, Stewart A, Gupta A, McGraw T. Cardiovascular outcome risks in patients with erectile dysfunction Co-Prescribed a phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitor (PDE5i) and a nitrate: A retrospective observational study using electronic health record data in the united States. J Sex Med. 2021;18:1511–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thadani U, Rodgers T. Side effects of using nitrates to treat angina. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2006;5:667–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nossaman VE, Nossaman BD, Kadowitz PJ. Nitrates and nitrites in the treatment of ischemic cardiac disease. Cardiol Rev. 2010;18:190–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dai W, Deng Y, Chen X, Huang Y, Hu H, Jin Q, Tang Z, Ji J. A mitochondria-targeted supramolecular nanoplatform for peroxynitrite-potentiated oxidative therapy of orthotopic hepatoma. Biomaterials. 2022;290:121854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang Z, Yang N, Hou Y, Li Y, Yin C, Yang E, Cao H, Hu G, Xue J, Yang J, et al. L-Arginine-Loaded gold nanocages ameliorate myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury by promoting nitric oxide production and maintaining mitochondrial function. Adv Sci (Weinh). 2023;10:e2302123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li J, Zhang J, Yu P, Xu H, Wang M, Chen Z, Yu B, Gao J, Jin Q, Jia F, et al. ROS-responsive & scavenging NO nanomedicine for vascular diseases treatment by inhibiting Endoplasmic reticulum stress and improving NO bioavailability. Bioact Mater. 2024;37:239–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith BR, Edelman ER. Nanomedicines for cardiovascular disease. Nat Cardiovasc Res. 2023;2:351–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fu C, Yu L, Miao Y, Liu X, Yu Z, Wei M. Peptide-drug conjugates (PDCs): a novel trend of research and development on targeted therapy, hype or hope? Acta Pharm Sin B. 2023;13:498–516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang Y, Cheetham AG, Angacian G, Su H, Xie L, Cui H. Peptide-drug conjugates as effective prodrug strategies for targeted delivery. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2017;110–111:112–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cooper BM, Iegre J, DH OD, Olwegard Halvarsson M, Spring DR. Peptides as a platform for targeted therapeutics for cancer: peptide-drug conjugates (PDCs). Chem Soc Rev. 2021;50:1480–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang B, Wang M, Sun L, Liu J, Yin L, Xia M, Zhang L, Liu X, Cheng Y. Recent advances in targeted Cancer therapy: are PDCs the next generation of adcs?? J Med Chem. 2024;67:11469–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wu M, Huang W, Yang N, Liu Y. Learn from antibody-drug conjugates: consideration in the future construction of peptide-drug conjugates for cancer therapy. Exp Hematol Oncol. 2022;11:93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Choi HS, Liu W, Misra P, Tanaka E, Zimmer JP, Itty Ipe B, Bawendi MG, Frangioni JV. Renal clearance of quantum Dots. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25:1165–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhong Y, Yang Y, Xu Y, Qian B, Huang S, Long Q, Qi Z, He X, Zhang Y, Li L, et al. Design of a Zn-based nanozyme injectable multifunctional hydrogel with ROS scavenging activity for myocardial infarction therapy. Acta Biomater. 2024;177:62–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Senoner T, Dichtl W. Oxidative Stress in Cardiovascular Diseases: Still a Therapeutic Target? Nutrients 2019, 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Wyant GA, Yu W, Doulamis IP, Nomoto RS, Saeed MY, Duignan T, McCully JD, Kaelin WG. Jr.: Mitochondrial remodeling and ischemic protection by G protein-coupled receptor 35 agonists. Science 2022, 377:621–629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Yan M, Gao J, Lan M, Wang Q, Cao Y, Zheng Y, Yang Y, Li W, Yu X, Huang X, et al. DEAD-box helicase 17 (DDX17) protects cardiac function by promoting mitochondrial homeostasis in heart failure. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2024;9:127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sun Q, Ma H, Zhang J, You B, Gong X, Zhou X, Chen J, Zhang G, Huang J, Huang Q, et al. A Self-Sustaining antioxidant strategy for effective treatment of myocardial infarction. Adv Sci (Weinh). 2023;10:e2204999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lin M, Xian H, Chen Z, Wang S, Liu M, Liang W, Tang Q, Liu Y, Huang W, Che D, et al. MCM8-mediated mitophagy protects vascular health in response to nitric oxide signaling in a mouse model of Kawasaki disease. Nat Cardiovasc Res. 2023;2:778–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wu X, Reboll MR, Korf-Klingebiel M, Wollert KC. Angiogenesis after acute myocardial infarction. Cardiovasc Res. 2021;117:1257–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xu D, Bi S, Li J, Ma S, Yu ZA, Wang Y, Chen H, Zhan J, Song X, Cai Y. Legumain-Guided Ferulate-Peptide Self-Assembly enhances Macrophage-Endotheliocyte partnership to promote therapeutic angiogenesis after myocardial infarction. Adv Healthc Mater. 2024;13:e2402056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kim C, Kim H, Sim WS, Jung M, Hong J, Moon S, Park JH, Kim JJ, Kang M, Kwon S, et al. Spatiotemporal control of neutrophil fate to tune inflammation and repair for myocardial infarction therapy. Nat Commun. 2024;15:8481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tang D, Kang R, Berghe TV, Vandenabeele P, Kroemer G. The molecular machinery of regulated cell death. Cell Res. 2019;29:347–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen HW, Chien CT, Yu SL, Lee YT, Chen WJ. Cyclosporine A regulate oxidative stress-induced apoptosis in cardiomyocytes: mechanisms via ROS generation, iNOS and Hsp70. Br J Pharmacol. 2002;137:771–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu Q, Huang J, Ding H, Tao Y, Nan J, Xiao C, Wang Y, Wu R, Ni C, Zhong Z et al. Flavin-containing monooxygenase 2 confers cardioprotection in ischemia models through its disulfide bond catalytic activity. J Clin Invest 2024;134:e177077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 44.Zheng X, Liu L, Liu J, Zhang C, Zhang J, Qi Y, Xie L, Zhang C, Yao G, Bu P. Fibulin7 mediated pathological cardiac remodeling through EGFR binding and EGFR-Dependent FAK/AKT signaling activation. Adv Sci (Weinh). 2023;10:e2207631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sun M, Mao S, Wu C, Zhao X, Guo C, Hu J, Xu S, Zheng F, Zhu G, Tao H, et al. Piezo1-Mediated neurogenic inflammatory cascade exacerbates ventricular remodeling after myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2024;149:1516–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liu S, Chen J, Shi J, Zhou W, Wang L, Fang W, Zhong Y, Chen X, Chen Y, Sabri A, Liu S. M1-like macrophage-derived exosomes suppress angiogenesis and exacerbate cardiac dysfunction in a myocardial infarction microenvironment. Basic Res Cardiol. 2020;115:22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu C, Huang J, Qiu J, Jiang H, Liang S, Su Y, Lin J, Zheng J. Quercitrin improves cardiac remodeling following myocardial infarction by regulating macrophage polarization and metabolic reprogramming. Phytomedicine. 2024;127:155467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen R, Zhang H, Tang B, Luo Y, Yang Y, Zhong X, Chen S, Xu X, Huang S, Liu C. Macrophages in cardiovascular diseases: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic targets. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2024;9:130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nakamura K, Fushimi K, Kouchi H, Mihara K, Miyazaki M, Ohe T, Namba M. Inhibitory effects of antioxidants on neonatal rat cardiac myocyte hypertrophy induced by tumor necrosis factor-alpha and angiotensin II. Circulation. 1998;98:794–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement