Abstract

Background

Sphingomyelin phosphodiesterase acid-like 3B (SMPDL3B) is emerging as a potential biomarker and therapeutic target in myalgic encephalomyelitis (ME), a complex multisystem disorder characterized by immune dysfunction, metabolic disturbances, and persistent fatigue. This study investigates the role of SMPDL3B in ME pathophysiology and explores its clinical relevance.

Methods

A case–control study was conducted in two independent cohorts: a Canadian cohort (249 ME patients, 63 controls) and a Norwegian replication cohort (141 ME patients). Plasma and membrane-bound SMPDL3B levels were quantified using ELISA and flow cytometry. Gene expression of SMPDL3B and PLCXD1, encoding phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C (PI-PLC), was analyzed by qPCR. The effects of dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitors—vildagliptin, saxagliptin, and linagliptin—on modulation of membrane-bound and soluble SMPDL3B were assessed in vitro by qPCR, flow cytometry and ELISA.

Results

ME patients exhibited significantly elevated plasma SMPDL3B levels, which correlated with symptom severity. Flow cytometry revealed a reduction in membrane-bound SMPDL3B in monocytes, accompanied by increased PLCXD1 expression and elevated plasma levels of PI-PLC and SMPDL3B. These findings suggest that immune dysregulation in ME may be linked to enhanced cleavage of membrane-bound SMPDL3B by PI-PLC. Sex-specific differences were observed, with female ME patients displaying higher plasma SMPDL3B levels, an effect influenced by estrogen. In vitro, estradiol upregulated SMPDL3B expression, indicating hormonal regulation. Vildagliptin and saxagliptin were tested for their potential to inhibit PI-PLC activity independently of their role as DPP-4 inhibitors, and restored membrane-bound SMPDL3B while reduced its soluble form.

Conclusions

SMPDL3B emerges as a key biomarker for ME severity and immune dysregulation, with its activity influenced by hormonal and PI-PLC regulation. The ability of vildagliptin and saxagliptin to preserve membrane-bound SMPDL3B and reduce its soluble form via PI-PLC inhibition suggests a novel therapeutic strategy. These findings warrant clinical trials to evaluate their potential in mitigating immune dysfunction and symptom burden in ME.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12967-025-06829-0.

Keywords: Myalgic encephalomyelitis (ME), Sphingomyelin phosphodiesterase acid-like 3b (SMPDL3B), Phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C (PI-PLC), Vildagliptin, Saxagliptin

Background

Myalgic encephalomyelitis (ME), also referred to as chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS), is a debilitating multisystem disorder of unknown etiology that affects millions worldwide, with a higher prevalence in women (4:1 ratio) [1]. ME is characterized by persistent fatigue, post-exertional malaise (PEM), dysautonomia, sleep disturbances, cognitive impairment, and immune dysfunction. Despite its profound impact on quality of life, no specific biomarkers or diagnostic tests are currently available, reflecting the limited understanding of its underlying pathophysiology [2]. Environmental triggers, including viral and bacterial infections or chemical exposures, have been implicated in disease onset, but the mechanisms driving disease progression remain unclear [2].

Immune dysfunction is a hallmark of ME, with patients frequently exhibiting altered T-cell responses, impaired natural killer (NK) cell activity, and dysregulated cytokine production, often marked by elevated pro-inflammatory cytokines [3]. In parallel, emerging evidence highlights metabolic abnormalities, particularly in lipid metabolism, as key contributors to disease pathology [4, 5]. Disruptions in energy production, lipid signaling pathways, and mitochondrial function have been linked to fatigue, cognitive impairment, and other ME symptoms [6, 7].

Sphingomyelin phosphodiesterase acid-like 3B (SMPDL3B) is a key immune-regulatory protein [8] involved in sphingolipid metabolism, a signaling network that governs essential cellular processes such as growth, differentiation, apoptosis, and inflammation [8]. SMPDL3B, when membrane-anchored, exerts a dual regulatory function in innate immune signaling by inhibiting TLR4 activation [8] while simultaneously enhancing TLR3 signaling [9]. In the TLR4 pathway, membrane-bound SMPDL3B modulates lipid raft composition, reducing membrane fluidity and limiting receptor clustering. This structural regulation dampens inflammatory responses, thereby curbing excessive release of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-6. Conversely, SMPDL3B promotes TLR3 activation by stabilizing the receptor complex within specialized membrane microdomains, enhancing type I interferon (IFN-β) production and supporting antiviral immunity [8]. Increased cleavage of membrane-bound SMPDL3B by plasma phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C (PI-PLC), encoded by the PLCDX1 gene, may disrupt immune regulation by simultaneously amplifying TLR4-driven inflammation and impairing TLR3-mediated antiviral defenses. This dual effect could contribute to immune dysregulation, a hallmark of ME pathophysiology. Given that chronic immune dysfunction, excessive inflammation, and impaired antiviral responses are central features of ME, the dysregulation of SMPDL3B may play a pivotal role in disease progression.

This study examines SMPDL3B levels and its regulatory mechanisms in well-characterized ME patient cohorts to assess its potential as a biomarker for disease severity and its role in ME pathophysiology. Given the emerging evidence of SMPDL3B’s involvement in immune regulation, we hypothesize that dysregulated cleavage of membrane-bound SMPDL3B by PI-PLC contributes to ME-associated immune dysfunction by disrupting TLR-mediated signaling, leading to excessive inflammation and impaired antiviral responses. Furthermore, we propose that pharmacological inhibition of PI-PLC can restore immune homeostasis by preserving membrane-bound SMPDL3B, offering a novel therapeutic strategy for ME.

Methods

Study populations

This case–control study utilized two independent prospective cohorts to investigate the role of SMPDL3B in ME pathophysiology. The Canadian cohort included 249 ME patients (208 females, 41 males) and 63 sedentary healthy controls (HC) (33 females, 30 males).

HC were included in the study if they met the following criteria: (1) over 18 years of age; (2) self-identified as Caucasian of European ancestry; (3) reported a sedentary lifestyle, defined as engaging in less than two hour of moderate-intensity exercise per week; and (4) had no personal or family history of ME. Controls were frequency-matched to the ME patient group based on age and sex distribution at the group level.

All the participants were recruited before the COVID-19 pandemic (Table 1). ME patients were diagnosed using the Canadian Consensus Criteria. All participants were over 18 years old and self-identified as Caucasian of European ancestry. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of CHU Sainte-Justine (protocol #4047), and all participants provided written informed consent. All procedures followed ethical guidelines and human research regulations.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of participants

| N (women:men) | Age (years) | BMI (kg/m2) | Disease duration (years) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Canadian cohort | ||||

| All ME patients | 249 | 47.9 ± 0.8 | 26.1 ± 0.4 | 7.1 ± 0.6 |

| Female ME patients | 208 | 48.9 ± 0.8 | 26.0 ± 0.4 | 6.8 ± 0.4 |

| Male ME patients | 41 | 46.9 ± 2.1 | 26.2 ± 0.5 | 7.4 ± 0.3 |

| All HC | 63 | 49.0 ± 1.4 | 25.3 ± 0.7 | NA |

| Female HC | 33 | 50.0 ± 2.1 | 23.9 ± 1.0 | |

| Male HC | 30 | 48.0 ± 2.0 | 26.7 ± 0.6 | |

| Norwegian cohort | ||||

| All ME patients | 141 | 36.8 ± 1.0 | 25.0 ± 0.4 | 7.5 ± 0.1 |

| Female ME patients | 119 | 36.8 ± 1.0 | 25.0 ± 0.5 | 7.5 ± 0.3 |

| Male ME patients | 22 | 36.7 ± 2.3 | 25.1 ± 0.7 | 7.6 ± 0.6 |

| p-value | ||||

| All | < 0.0001**** | 0.0763 | 0.1966 | |

| Female | < 0.0001**** | 0.3421 | 0.1316 | |

| Male | 0.0063** | 0.3437 | 0.8757 |

BMI Body Mass Index

Data were expressed in mean ± standard error of the mean. Statistical comparisons were performed between Canadian ME patients, Canadian healthy controls, and Norwegian ME patients. Age and BMI were compared using a Kruskal–Wallis test, followed by post hoc analysis when appropriate. Disease duration was compared between Canadian and Norwegian ME patients using Mann–Whitney U test

For replication, plasma samples were obtained from a Norwegian cohort of 141 ME patients (119 females, 22 males), all diagnosed according to the Canadian Consensus Criteria. These samples were collected at Haukeland University Hospital as part of a previous study conducted between 2014 and 2017 [ClinicalTrials.gov NCT02229942, 2014–2017; [10]], with participants providing informed consent under that study’s protocol. To account for potential biological influences on ME prevalence, symptomatology, and clinical outcomes, a sex-disaggregated analysis was performed.

Plasma and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) collection

Peripheral blood samples were collected from Canadian cohort participants via median cubital vein venipuncture into EDTA-treated tubes to prevent coagulation. Whole blood was centrifuged at 215×g for 10 min, after which plasma was aliquoted and stored at − 80 °C until further analysis. To isolate PBMCs, the remaining fraction was diluted with a balanced salt solution (Wisent Inc., Saint-Jean-Baptiste, QC, Canada), layered onto lymphocyte separation media (Wisent), and centrifuged at 400×g for 30 min. The resulting PBMC ring was collected, washed in complete RPMI 1640 media (Wisent), and centrifuged at 250×g for 7 min. The final cell pellet was resuspended in a cryopreservation solution consisting of RPMI 1640 media supplemented with 40% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Thermo Fisher Scientific), 10% dimethyl sulfoxide, DMSO (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), and 1% antibiotic–antimycotic (Wisent). Cells were then stored in liquid nitrogen for further analysis.

Evaluation of participant’s health status, ME symptoms and disease severity

Health status and symptom severity were assessed using standardized questionnaires. Canadian cohort participants completed the 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36), Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory (MFI-20), and DePaul Symptom Questionnaire (DSQ). SF-36 provides an overview of physical and mental health status [11]. MFI-20 evaluates fatigue across five domains: General Fatigue, Physical Fatigue, Reduced Activity, Reduced Motivation, and Mental Fatigue, with total scores used to determine disease severity [12]. The DSQ assesses symptom frequency and groups responses into four factors: Neuroendocrine, Autonomic and Immune Dysfunction, Cognitive Dysfunction, Post-Exertional Malaise, and Sleep Disturbances [13]. Disease severity in the Norwegian cohort was determined by the investigating physician based on a standardized clinical assessment [10]. The criteria for the five categories were as follows: Mild ME: Activity level reduced by ≥ 50% pre-illness, mobile, can do light household tasks, may work part-time with cost, needs rest days; Mild/Moderate ME: Mostly housebound, significantly reduced activities with occasional better days; Moderate ME: Mostly housebound, significantly reduced activities, unable to work/study, needs daily rest, poor sleep. Moderate/Severe ME: Mostly immobile, very limited capacity for self-care; Severe ME: Immobile most of the day (bed-sofa), very limited self-care, rarely leaves home, severe PEM, may have sensory sensitivities. Patients with very severe ME (bedbound 24/7 and needing full care) were excluded from this categorization. [10]. Since the Canadian and Norwegian cohorts did not use the exact same set of questionnaires, we analyzed the cohorts separately using their respective classifications.

Measurement of plasma SMPDL3B and PI-PLC levels

Plasma SMPDL3B levels were quantified using a sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (Cat. ABX585223, Abbexa Ltd, Cambridge, UK) following the manufacturer’s protocol. All samples were analyzed in duplicate to ensure accuracy, and mean values were used for analysis. PI-PLC levels were measured using a commercial ELISA kit (Cat. MBS038525-96, MyBioSource, San Diego, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Duplicate readings were averaged for analysis.

Quantitative PCR for SMPDL3B, PLCXD1, and IL-6 gene expression

Relative gene expression of SMPDL3B, PLCXD1 (encoding PI-PLC), and IL-6 was assessed using quantitative PCR (qPCR) with TaqMan probes. Total RNA was extracted from PBMCs using TRIzol reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) following the manufacturer’s protocol. RNA concentration and purity were evaluated using a Nanodrop spectrophotometer (TM1000, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Complementary DNA (cDNA) synthesis was performed using 1 µg of total RNA and the All-In-One 5 × MasterMix (Cat. G592, Applied Biological Materials, Richmond, BC, Canada).

qPCR reactions were performed in 10 µL volumes using TaqMan Universal Master Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific), target-specific TaqMan assays (SMPDL3B: Hs00205522_m1, PLCXD1: Hs00895227_m1, IL-6: Hs00174131_m1, GAPDH: Hs02786624_g1), and a QuantStudio 3 Real-Time PCR System (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Cycling conditions were: 50 °C for 2 min, 95 °C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s and 60 °C for 1 min. Gene expression was calculated using the comparative Ct method (2^−ΔΔCt), normalizing to GAPDH. All reactions were performed in duplicate, with negative controls (nuclease free water) included to rule out contamination.

Flow cytometry for detection of membrane-anchored SMPDL3B

Cryopreserved PBMCs from a subset of participants in the Canadian cohort, consisting of 27 ME patients and 9 HC, were thawed, washed, and incubated overnight in RPMI 1640 medium (Wisent) with 10% FBS (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and 1% antibiotic–antimycotic (Wisent) using 3 million of cells per patient and healthy controls (1.5 million for the staining and 1.5 million for the unstained part). Cells were stained using a 1:25 dilution of monoclonal anti-SMPDL3B antibody (LS-C132144, LifeSpan BioSciences Inc., Lynnwood WA, USA), with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated secondary antibody (Cat. A11029, 1:50 dilution, Thermo Fisher Scientific) used for detection. Isotype controls were included to account for non-specific binding. Samples were analyzed using a BD Fortessa flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA), and mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) was quantified using FlowJo software (v10.10, FlowJo LLC, Ashland, OR, USA). During the analysis, viability and doublet exclusion were considered, and only viable singlet cells were included. Calibration was performed using the QIFIKIT quantitative analysis kit (Cat. K007811-8, Dako, Glostrup, Denmark).

Western blot

Jurkat cells were treated with Diarylpropionitrile (DPN, Tocris, Bristol, UK), a selective Estrogen Receptor β (ERβ) agonist, to assess estrogen-mediated SMPDL3B regulation for 18 h. Cells were lsed using RIPA buffer with protease inhibitors, and protein concentration was determined using the Bio-Rad Protein Assay Dye (Cat. 5000006, Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA). Proteins were separated via 10% SDS-PAGE, transferred to PVDF membranes (Bio-Rad), and blocked with 10% Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) in PBS-Tween 0.2%. Membranes were incubated overnight at 4 °C with SMPDL3B (Proteintech, Rosemont, IL, USA). The next day, the membrane was stripped using a mild stripping buffer composed of 15 g/L glycine, 1 g/L SDS and 0.01% Tween 20. The membrane was incubated twice in fresh buffer for 10 min, followed by two washes in 1X PBS and two washes in 1X TBST. The membrane was then incubated overnight with β-actin antibody (Cat. Sc47778, 1:1000 dilution, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA) antibodies, followed by goat anti-rabbit HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (Cat. 31462, 1:5000 dilution, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Protein bands were visualized using ChemiDoc MP Imaging System (Bio-Rad).

In vitro TLR4 challenge with LPS

PBMCs were isolated from four ME patients and four healthy controls, selected based on lower levels of membrane-anchored SMPDL3B compared to healthy subjects. Cells were stimulated for 4 h with increasing concentrations of lipopolysaccharides (LPS, TLR4 agonist, Cat. L7895-1MG, Sigma- Aldrich) at 0.4, 1, and 2 µg/mL. After stimulation, RNA was extracted from a portion of the cells for RT-qPCR to evaluate IL-6 and PLCXD1 expression. Another portion was lysed using RIPA buffer supplemented with a protease inhibitor cocktail, and the supernatant was collected for SMPDL3B quantification by ELISA. SMPDL3B levels were assessed in both cell lysates and supernatants by ELISA method.

In vitro experiments with PI-PLC pharmacological inhibitors

Our initial search for potential PI-PLC inhibitors among FDA- or Health Canada-approved molecules did not identify any suitable candidates. However, further exploration revealed vildagliptin, a dipeptidyl-peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitor previously reported to inhibit Bacillus cereus PI-PLC at micromolar concentrations, as a promising candidate [14]. To investigate this potential, we conducted in vitro experiments using PBMCs isolated from healthy individuals. This experimental setup enabled us to directly assess the effects of vildagliptin and two related DPP-4 inhibitors on SMPDL3B modulation. Saxagliptin was selected due to its structural similarity to vildagliptin, suggesting a potential capacity to inhibit PI-PLC activity, while linagliptin, with a distinct molecular structure, served as a negative control.

PBMCs were treated with increasing concentrations (25, 50, and 100 µM) of vildagliptin (Cat. SML2302-50MG, Sigma-Aldrich), saxagliptin (Cat. 23697-10, Cayman Chemical’s, Ann Arbor, MI, USA), and linagliptin (Cat. SML3619-10MG, Sigma-Aldrich), all reconstituted in DMSO (Cat. D2650-100 mL, Sigma-Aldrich). Untreated cells received only the vehicle (DMSO). PBMCs were seeded in 12-well culture plates, at a concentration of 1.3 × 106 cells/well. After an 18-h treatment period, cells and culture media were harvested for further analysis. To evaluate the effects on SMPDL3B gene expression, total RNA was extracted from treated PBMCs, and the relative expression of SMPDL3B and PLCXD1 genes was quantified using RT-qPCR. Additionally, the impact on membrane-bound SMPDL3B was assessed by staining the cells with fluorescently labeled anti-SMPDL3B antibodies followed by flow cytometry analysis, as detailed above. Finally, to measure soluble SMPDL3B released into the culture medium (RPMI 1640), cell-free supernatants were collected and measured by ELISA.

Statistical analysis

Data were expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). For comparisons between two groups, the Mann–Whitney U test was used. For comparisons involving more than two groups, the Kruskal–Wallis test was performed, followed by Dunn’s post hoc test with multiple comparison correction. Since the data were not normally distributed, Spearman’s correlation coefficient was used to assess variable associations. A P-value ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant. To investigate the relationship between SMPDL3B levels and disease severity, a threshold of 30 ng/mL was established for the Canadian cohort using a Random Forest model implemented in Python with the open-source scikit-learn library (version 1.6.1). This threshold was derived from symptom severity scores obtained across three validated questionnaires: MFI-20, SF-36, and DSQ. Model performance and threshold stability were assessed using k-fold cross-validation, by obtaining the corresponding ROC curve, sensitivity, and specificity. Additionally, a multivariate logistic regression analysis was conducted to assess the influence of sex, age, and estrogen use on plasma SMPDL3B levels. Variables were included simultaneously in the model, and odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated.

Results

Clinical and demographic data of study participants

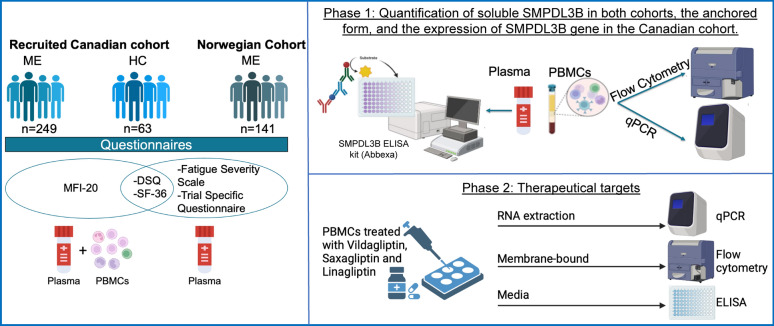

The clinical and demographic characteristics of the Canadian and Norwegian cohorts are summarized in Table 1. The study design is illustrated in Fig. 1. The sex distribution in both cohorts reflects the well-documented higher prevalence of ME in women, with females comprising 83% of the Canadian cohort and 84% of the Norwegian cohort. Given that sex is a crucial biological variable influencing immune responses and disease susceptibility, its consideration in ME is essential [15]. There were no significant differences in body mass index (BMI) or age between ME patients and HC in the Canadian cohort. Similarly, illness duration did not significantly differ between the Canadian and Norwegian ME cohorts. However, the Canadian cohort was significantly older than the Norwegian cohort (p < 0.0001, Supplementary Fig. S1). The prevalence of several comorbidities within Canadian ME cohort (n = 249), the Canadian Healthy Control (HC) group (n = 63), and the Norwegian ME cohort (n = 141) is detailed in Supplementary Table S2. In the Canadian ME cohort, the most frequent comorbidities reported were allergy (38.2%), fibromyalgia (35.7%), and anxiety (31.3%), followed closely by depression (30.9%). Hypothyroidism was reported in a smaller percentage (2.4%). The HC group in Canada showed a lower prevalence of most comorbidities compared to the ME group, with allergy being the most common (27.0%), followed by anxiety (12.7%) and depression (11.1%). Fibromyalgia was absent in the HC group. In the Norwegian ME cohort, allergy was also highly prevalent (39.7%), followed by other comorbidities (18.4%), anxiety (9.9%), depression (8.5%), hypothyroidism (5.7%), and fibromyalgia (7.8%).

Fig. 1.

Illustration of the experimental study design. ME encephalomyelitis, HC healthy controls, MFI-20 Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory, SF-36 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey, DSQ DePaul Symptom Questionnaire

Association between circulating SMPDL3B levels and ME severity

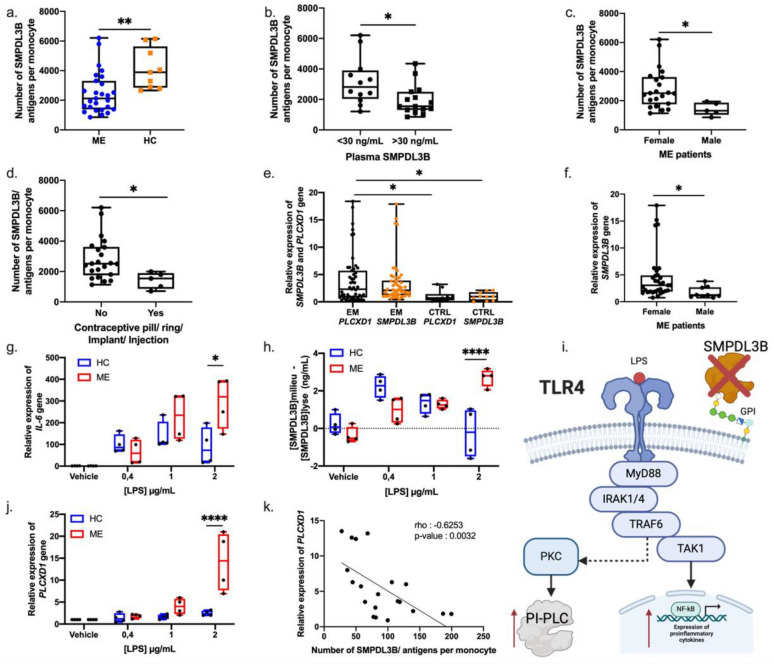

Plasma SMPDL3B levels were significantly elevated in ME patients compared to HC in the Canadian cohort (Fig. 2a), suggesting a potential role for SMPDL3B in ME pathophysiology. To evaluate the variability of circulating SMPDL3B levels among ME patients and explore its potential as a biomarker for disease severity, we stratified the Canadian cohort into high and low plasma SMPDL3B level groups using a 30 ng/mL threshold (Supplementary Table S1). This threshold was determined using ROC curve analysis applied to the entire Canadian cohort. By optimizing for both sensitivity and specificity through k-fold cross-validation using a Random Forest model, we obtained an AUC of 0.84 (Supplementary Fig. S2), with a specificity of 87% and a sensitivity of 77% at a threshold of 30 ng/mL. These results confirm the robustness of SMPDL3B as a biomarker for stratifying disease severity based on multiple symptom scores from the MFI-20, SF-36, and DSQ questionnaires.

Fig. 2.

Influence of covariates on plasma SMPDL3B levels and symptom severity in ME patients. (a) Plasma levels of SMPDL3B in ME patients (n = 249) and healthy controls (n = 63) from the Canadian cohort. (b) Plasma levels of SMPDL3B in different groups of patients with ME from the Norwegian cohort grouped by symptom severity (n = 16 for mild, n = 40 for mild/moderate, n = 41 for moderate, n = 22 moderate/severe and n = 21 severe). Disease severity was determined based on clinical assessments incorporating standardized and trial-specific questionnaires. (c) Plasma SMPDL3B levels in ME Canadian, ME Norwegian and healthy control female participants (n = 208, n = 119 and n = 33 respectively) and males (n = 41, n = 22 and n = 30 respectively). (d) Plasma concentrations of SMPDL3B in Canadian female ME participants across different age groups (n = 16 for 18–30 years, n = 97 for 31–50 for years, n = 95 for 51 years and up). (e) Plasma concentrations of SMPDL3B in Norwegian female ME participants across different age groups (n = 37 for 18–30 years, n = 65 31–50 for years, n = 16 for 51 years and up). (f) Plasma levels of SMPDL3B in Canadian female participants with or without oral contraceptive use (n = 176 and n = 32 respectively). (g) Plasma levels of SMPDL3B in Norwegian female participants with or without oral contraceptive use (n = 88 and n = 31 respectively). An unpaired T test was performed when comparing two groups. For comparisons between two groups, the Mann–Whitney U test was used. For comparisons involving more than two groups, the Kruskal–Wallis test was performed, followed by Dunn’s post hoc test with multiple comparison correction where appropriate. Differences were found to be significant at *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, *** P-value < 0.001 and ****P < 0.0001

This threshold offers a simple binary classification, which can be useful in a clinical setting for quick screening or stratification. Patients with plasma SMPDL3B levels above 30 ng/mL exhibited significantly greater symptom burden and disease severity, as reflected by lower SF-36 scores and higher MFI-20 and DSQ scores. We aimed to validate our findings from the Canadian cohort using the independent Norwegian cohort. To this end, we calculated a ROC curve to assess the association between SMPDL3B levels and severity scores. This analysis yielded an AUC of 0.73, with a sensitivity of 75% and a specificity of 79%, supporting the reproducibility of the association between elevated SMPDL3B levels and increased symptom severity in an independent population.

Disease severity was classified into five categories (mild, mild/moderate, moderate, moderate/severe, severe) in the Norwegian cohort based on standardized clinical assessments, including Fatigue Scale, and Clinical Trial Questionnaire scores. Consistent with findings in the Canadian cohort, plasma SMPDL3B levels were significantly higher in the severe ME group compared to the mild ME group (Fig. 2b, p < 0.05).

Influence of sex, age, and estrogen on SMPDL3B levels

Sex, age, and hormonal factors were examined as potential modulators of SMPDL3B levels. Women exhibited significantly higher circulating SMPDL3B levels than men in both cohorts (Fig. 2c), consistent with the higher prevalence of ME in women. Given the observed sex imbalance in both cohorts, we independently examined the association of higher plasma SMPDL3B levels (≥ 30 ng/mL) with distinct symptom patterns in women and men. Among women, elevated levels were significantly linked to greater severity across multiple domains, including physical function, reduced activity, physical fatigue, post-exertional malaise and overall severity. In contrast, among men, higher SMPDL3B levels were primarily associated with increased overall symptom severity and reduced motivation (Supplementary Table S3). Notably, independent of SMPDL3B levels, women generally exhibited higher overall disease severity than men. Specifically, female ME patients presented with greater cognitive disturbances, sleep disturbances, autonomic symptoms, post-exertional malaise, and higher physical symptom scores. Conversely, men reported lower overall severity scores but exhibited higher reduced motivation compared to women (Supplementary Table S4). Further analysis revealed an age-dependent decline in plasma SMPDL3B concentrations, with the highest levels observed in patients aged 18–30 years, followed by a progressive decline with age (Fig. 2d–e).

In the logistic regression analysis accounting for age, sex, and plasma SMPDL3B levels, we found that for every 50 ng/mL increase in plasma SMPDL3B levels, patients had three times higher odds (OR = 3.0, 95% CI [2.0–4.4], p < 0.001) of experiencing greater disease severity. Notably, age did not significantly affect severity (p = 0.566). However, this association was primarily observed in female patients, who comprised 84% of the cohort (p < 0.001). Due to the small sample size of male patients, logistic regression could not be reliably performed in this subgroup, precluding the calculation of an odds ratio specific to men. The insufficient statistical power in this group highlights the need for larger, sex-stratified studies to confirm these findings. These results suggest that plasma SMPDL3B levels are associated with disease severity, particularly in female patients. Further studies are needed to validate this association and to elucidate the potential influence of sex hormones on SMPDL3B regulation, which we further explore in this study.

Estradiol modulates SMPDL3B levels in vitro

Given the observed sex differences and the higher prevalence of ME in women, we investigated the role of estrogen in regulating SMPDL3B levels. Women using oral contraceptives, which contain synthetic estrogen and progestin, exhibited higher plasma SMPDL3B levels compared to non-users in both cohorts (Fig. 2f–g), whereas menopausal women, who have lower estrogen levels, displayed reduced plasma SMPDL3B levels [16]. To further explore the regulatory effects of estrogen, we treated Jurkat cells (human immortalized T lymphocytes) with estradiol in a dose-dependent manner (0.25–1 nM). Western blot analysis revealed a significant increase in total SMPDL3B protein levels in cell lysates following estradiol treatment, with β-actin levels remaining unchanged (Supplementary Fig. S3a–b). Additionally, estradiol modulated soluble SMPDL3B levels in the culture media, suggesting that estrogen influences both SMPDL3B expression and its extracellular release (Supplementary Fig. S3c). To quantitatively confirm these results, we measured SMPDL3B and PI-PLC levels using ELISA (Supplementary Fig. S3d–e). We observed increased SMPDL3B production at 0.25 and 0.5 nM of estradiol, with a peak in PI-PLC levels at 0.25 nM in the cell lysates. In the culture media, the highest levels of SMPDL3B and PI-PLC were detected at 0.85 and 1 nM extracellularly. These findings support a mechanistic link between estrogen signaling and SMPDL3B regulation, which may contribute to the observed sex differences in ME.

Modulation of membrane-bound and soluble SMPDL3B protein levels in PBMCs

Flow cytometry analysis revealed that membrane-bound SMPDL3B was more abundant on monocytes than on lymphocytes in both ME and HC groups (Supplementary Fig. S4). However, ME patients exhibited significantly reduced membrane-bound SMPDL3B on monocytes compared to HC (Fig. 3a), with a more pronounced reduction in those with high circulating SMPDL3B levels (> 30 ng/mL) (Fig. 3b). Additionally, women with ME showed higher levels of membrane-bound SMPDL3B on monocytes than men with ME (Fig. 3c). This sex-based difference may be attributed to a reduced SMPDL3B gene expression in men with ME compared to women with ME (Supplementary Fig. S5a). Despite higher SMPDL3B expression, membrane-bound levels remained lower in women with ME compared to healthy women, and a similar trend was observed in men with ME compared to healthy men (Supplementary Fig. S5b). Furthermore, ME patients using oral contraceptives exhibited reduced SMPDL3B levels at the surface of their monocytes (Fig. 3d), consistent with our in vitro estradiol experiments (Supplementary Fig. S3). Given the elevated SMPDL3B gene expression in ME patients (Fig. 3e), the observed reduction in membrane-bound SMPDL3B was unlikely due to transcriptional downregulation.

Fig. 3.

Reduced membrane-bound SMPDL3B caused by an increase of PLCXD1 expression and production in ME patients. a Number of SMPDL3B antigens per monocyte in ME patients (n = 27) and healthy controls (HC) (n = 9). Membrane-bound SMPDL3B levels were quantified using flow cytometry, with gating strategies applied to identify monocyte populations. b SMPDL3B antigens per monocyte in ME patients with low (n = 12) and high (n = 15) plasma SMPDL3B levels, with a 30 ng/ml threshold. c SMPDL3B antigens per monocyte in female (n = 22) and male (n = 5) ME patients. d SMPDL3B antigens per monocyte in female with (n = 5) and without (n = 22) contraceptive pill use. e Relative expression of SMPDL3B and PLCXD1 genes in ME patients (n = 51) and HC (n = 10). Gene expression was measured by RT-qPCR and normalized using GAPDH. f Relative expression of the SMPDL3B gene in females (n = 40) and males (n = 11) with ME. g Relative expression of IL-6 gene in PBMCs from 4 patients and 4 controls, treated for 4 h with increasing doses of LPS. h Difference in SMPDL3B levels between cell culture medium and cell lysate of PBMCs from ME patients (n = 4) and HC (n = 4) treated with increasing doses of LPS. i Illustration proposing a mechanism by which the reduction of membrane-bound SMPDL3B leads to an increase in PI-PLC through PKC activation upon stimulation of TLR4 by LPS. j Relative expression of PLCXD1 gene in PBMCs from 4 patients and 4 controls, treated for 4 h with increasing doses of LPS. k Correlation between the relative expression of PLCXD1 and SMPDL3B antigens per monocyte in ME patients (n = 20). Spearman correlation was used with an rho of -0.6253 and a p-value < 0.0032. T test was used when comparing two groups. For comparisons between two groups, the Mann–Whitney U test was used. For comparisons involving more than two groups, the Kruskal–Wallis test was performed, followed by Dunn’s post hoc test with multiple comparison correction where appropriate. Differences considered significant at *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P-value < 0.001 and ****P-value < 0.0001

To investigate the mechanism underlying the loss of membrane-bound SMPDL3B, we examined the role of phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C (PI-PLC), encoded by PLCXD1 gene. PI-PLC cleaves glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) anchors, leading to the release of GPI-anchored proteins from cellular membranes. Experimental evidence confirmed that PI-PLC treatment releases SMPDL3B from membranes, verifying its GPI-anchored status [8]. ME patients exhibited significantly upregulated PLCXD1 expression (Fig. 3e), which positively correlated with SMPDL3B gene expression (Supplementary Fig. S6a) and plasma SMPDL3B levels (Supplementary Fig. S6c), while negatively correlating with membrane-bound SMPDL3B levels (Supplementary Fig. S6b). Notably, men with ME exhibited lower PLCXD1 expression than women with ME (Supplementary Fig. S5a), suggesting a potential sex-based regulatory mechanism. The overall lower levels of membrane-anchored SMPDL3B in male ME patients can be attributed to their reduced SMPDL3B expression (Fig. 3f).

Functional consequences of reduced membrane-bound SMPDL3B levels

To examine the functional impact of reduced membrane-bound SMPDL3B, we assessed TLR4-mediated cytokine production. PBMCs from ME patients exhibited increased IL-6 production following LPS stimulation compared to HC (Fig. 3g). Additionally, LPS stimulation increased soluble SMPDL3B levels in ME patient PBMC culture media (Fig. 3h), linking reduced membrane-bound SMPDL3B to heightened inflammatory responses. As previously shown, SMPDL3B inhibits TLR4, but when increasing doses of recombinant SMPDL3B were added to LPS-stimulated PBMCs, activation of TLR4 by LPS was not inhibited, and IL-6 expression remains high (Supplementary Fig. S7). This suggests that the soluble form of SMPDL3B does not play the same role as the anchored form.

Contribution of PI-PLC in TLR4 signaling and inflammatory amplification loop

We propose that TLR4 activation by LPS may enhance PI-PLC activity, leading to the cleavage of membrane-bound SMPDL3B and further amplifying the inflammatory response. Supporting this hypothesis, LPS stimulation significantly upregulated PLCXD1 expression in ME patients (Fig. 3j), which correlated with a reduction in the membrane-bound form of SMPDL3B (Fig. 3k, rho = − 0.6253, p = 0.0032). These findings suggest an amplification loop in which inflammation promotes PI-PLC activity, contributing to sustained SMPDL3B cleavage and exacerbation of the inflammatory cascade (Fig. 3i).

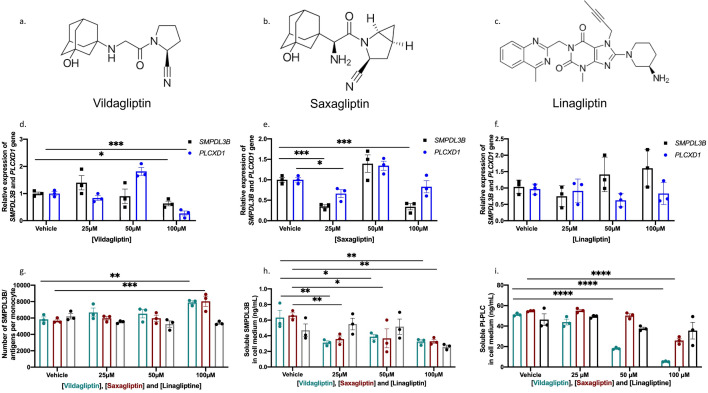

Therapeutic potential of PI-PLC pharmacological inhibitors on SMPDL3B modulation

Given the role of PI-PLC in cleaving membrane-bound SMPDL3B and contributing to the amplification of inflammatory processes in ME, we explored the therapeutic potential of vildagliptin, a known DPP-4 inhibitor, and two related molecules saxagliptin and linagliptin, in modulating SMPDL3B levels. Notably, vildagliptin, a widely used DPP-4 inhibitor for type 2 diabetes treatment, has been shown previously to interact with and inhibit Bacillus cereus PI-PLC activity at micromolar concentrations, which prompted our interest to test it in vitro [18]. We treated PBMCs from healthy controls (HC) with increasing doses of vildagliptin (25–100 µM) and observed no effect on SMPDL3B expression at low concentrations (25–50 µM) while a significant reduction was measured at the highest concentration (100 µM) (Fig. 4d), indicating a transcriptional effect. Despite this reduction in gene expression, there was a marked increase in membrane-bound SMPDL3B levels in monocytes at 100 µM of vildagliptin (Fig. 4g). This suggests that vildagliptin stabilizes the membrane anchoring of SMPDL3B, potentially counteracting PI-PLC-mediated cleavage. Furthermore, vildagliptin treatment resulted in decreased soluble SMPDL3B levels at all tested concentrations (Fig. 4h), supporting the hypothesis that vildagliptin may inhibit the cleavage process of SMPDL3B through the direct pharmacological inhibition of human PI-PLC. Additionally, vildagliptin significantly reduced soluble PI-PLC levels at 50 and 100 µM (Fig. 4i).

Fig. 4.

Vildagliptin and Saxagliptin Modulate SMPDL3B Expression and Membrane Anchoring in PBMCs. The molecular structures of vildagliptin, saxagliptin and linagliptin are shown in panels a, b and c respectively. The data are displayed as a histogram with individual data points overlaid with mean and standard error of the mean (SEM). d Gene expression levels of SMPDL3B and PLCXD1 in PBMCs treated with increasing doses of vildagliptin. e Gene expression levels of SMPDL3B and PLCXD1 in PBMCs treated with increasing doses of saxagliptin. f Gene expression levels of SMPDL3B and PLCXD1 in PBMCs treated with increasing doses of linagliptin. Gene expression was measured using RT-qPCR with TaqMan probes and normalized to the housekeeping gene GAPDH. g Levels of membrane-bound SMPDL3B in monocytes after treatment with increasing doses of vildagliptin, saxagliptin and linagliptin (NT (no treatment), 25 µM, 50 µM, and 100 µM). Membrane-bound SMPDL3B levels were quantified using flow cytometry, with gating strategies applied to identify monocyte populations. h Levels of membrane-bound SMPDL3B in lymphocytes under the same conditions. i Levels of soluble PI-PLC in cell culture supernatant of PBMCs following treatment with increasing doses of vildagliptin, saxagliptin and linagliptin. Soluble SMPDL3B and PI-PLC levels were quantified using ELISA. T test was used when comparing two groups. For comparisons between two groups, the Mann–Whitney U test was used. For comparisons involving more than two groups, the Kruskal–Wallis test was performed, followed by Dunn’s post hoc test with multiple comparison correction where appropriate. Differences were found to be significant at *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P-value < 0.001 and ****P-value < 0.0001

Saxagliptin, a structurally similar DPP-4 inhibitor, exhibited effects comparable to vildagliptin (Fig. 4a, b). At 100 µM, saxagliptin increased membrane-bound SMPDL3B (Fig. 4g) and reduced soluble SMPDL3B levels (Fig. 4h) at all tested concentrations. Moreover, saxagliptin treatment also led to a significant decrease in soluble PI-PLC levels at 100 µM (Fig. 4i). However, while both saxagliptin and vildagliptin decreased SMPDL3B expression (Fig. 4d, e), only vildagliptin led to a reduction in PLCXD1 expression (Fig. 4d), further strengthening the distinct inhibitory effect of vildagliptin and saxagliptin on human PI-PLC. In contrast, linagliptin, a DPP-4 inhibitor with a different molecular structure (Fig. 4c), did not exhibit the same effects on SMPDL3B modulation. Linagliptin increased both SMPDL3B and PLCXD1 expression, along with elevated levels of soluble SMPDL3B and PI-PLC, while reducing the membrane-bound form of SMPDL3B. These findings underscore the unique ability of vildagliptin and saxagliptin to stabilize the membrane-bound form of SMPDL3B, highlighting their potential as therapeutic strategies to modulate SMPDL3B levels by inhibiting PI-PLC activity, independently of their role as DPP-4 inhibitors.

Given the promising results obtained in healthy controls, we further investigated the effects of vildagliptin and saxagliptin on PBMCs isolated from ME patients. Patients were selected based on their plasma SMPDL3B levels, categorized into two groups: those with high plasma SMPDL3B levels (> 30 ng/mL) and those with low plasma SMPDL3B levels (< 30 ng/mL). Due to the limited availability of biological samples and the prior findings in healthy subjects, we selected a single concentration of 100 µM, which had previously shown significant effects. Treatment with vildagliptin and saxagliptin resulted in a significant reduction in SMPDL3B and PLCXD1 gene expression (Fig. 5a). Notably, SMPDL3B expression was reduced in both patient groups, regardless of their initial plasma SMPDL3B levels (Fig. 5b). However, PLCXD1 downregulation was observed exclusively in patients with high plasma SMPDL3B levels and only in response to vildagliptin treatment (Fig. 5c). At the protein level, both vildagliptin and saxagliptin led to an increase in membrane-bound SMPDL3B (Fig. 5d), with a particularly pronounced effect in patients with high plasma SMPDL3B levels (Fig. 5e). This suggests that these drugs may enhance the stabilization of membrane-anchored SMPDL3B proteins, preventing its cleavage by PI-PLC. In parallel, a significant reduction in soluble SMPDL3B was observed upon vildagliptin treatment (Fig. 5f), with the most pronounced decrease occurring in patients with high SMPDL3B plasma levels (Fig. 5g). Furthermore, vildagliptin treatment led to a notable reduction in total PI-PLC levels (Fig. 5h). A significant decrease in plasma PI-PLC was observed in all patients following vildagliptin treatment, while saxagliptin specifically reduced soluble PI-PLC levels in patients with initially low SMPDL3B levels (Fig. 5i). Importantly, linagliptin did not exhibit significant effects in any of these experiments, further highlighting the distinct pharmacological properties of vildagliptin and saxagliptin in modulating SMPDL3B and PI-PLC levels.

Fig. 5.

Vildagliptin and Saxagliptin Modulate SMPDL3B Expression and Membrane Anchoring in Patient PBMCs. Data are presented as bar graphs with individual data points overlaid, showing the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). a SMPDL3B and PLCXD1 gene expression levels in PBMCs from ME patients treated with 100 µM vildagliptin, saxagliptin, or linagliptin. b SMPDL3B gene expression in PBMCs stratified by plasma SMPDL3B levels (> 30 ng/mL or < 30 ng/mL) following treatment with 100 µM vildagliptin, saxagliptin, or linagliptin. c PLCXD1 gene expression in PBMCs stratified by plasma SMPDL3B levels following treatment with 100 µM vildagliptin, saxagliptin, or linagliptin. Gene expression was measured using RT-qPCR with TaqMan probes and normalized to GAPDH as a housekeeping gene. d Membrane-bound SMPDL3B levels in monocytes following treatment with 100 µM vildagliptin, saxagliptin, or linagliptin, assessed using flow cytometry. Gating strategies were applied to identify monocyte populations. e Membrane-bound SMPDL3B levels in monocytes stratified by plasma SMPDL3B levels (> 30 ng/mL or < 30 ng/mL) under the same treatment conditions. f Soluble SMPDL3B levels in the culture supernatant of patient PBMCs treated with 100 µM vildagliptin, saxagliptin, or linagliptin, quantified using ELISA. g Soluble SMPDL3B levels in the culture supernatant of PBMCs stratified by plasma SMPDL3B levels following treatment with 100 µM vildagliptin, saxagliptin, or linagliptin. h Soluble PI-PLC levels in the culture supernatant of PBMCs treated with 100 µM vildagliptin, saxagliptin, or linagliptin, quantified using ELISA. i Soluble PI-PLC levels in the culture supernatant of PBMCs stratified by plasma SMPDL3B levels following treatment with 100 µM vildagliptin, saxagliptin, or linagliptin. Statistical analysis was performed using an unpaired t-test for comparisons between two groups. For comparisons between two groups, the Mann–Whitney U test was used. For comparisons involving more than two groups, the Kruskal–Wallis test was performed, followed by Dunn’s post hoc test with multiple comparison correction where appropriate. Statistical significance was indicated as follows: P < 0.05 (*), P < 0.01 (**), P < 0.001 (***), and P < 0.0001 (****)

Discussion

ME is a complex disorder characterized by chronic fatigue, PEM, dysautonomia, sleep disturbances, cognitive impairments, and widespread pain. Its pathophysiology remains poorly understood, with diagnosis relying on clinical assessment due to a lack of objective biomarkers. Recent research suggests that immune dysregulation and chronic inflammation play key roles in disease progression [17–20]. Elevated plasma SMPDL3B levels correlated with disease severity and poorer scores on health-related questionnaires (SF-36, MFI-20, DSQ), reinforcing its clinical relevance. This association was consistent across Canadian and Norwegian cohorts, supporting its robustness and generalizability.

Given the established role of immune disturbances in ME, our findings suggest that membrane-bound SMPDL3B may modulate TLR4 signaling and contribute to symptom severity by influencing this inflammatory pathway [17–20]. This mechanism aligns with prior evidence showing that SMPDL3B regulates TLR4 signaling in macrophages and dendritic cells by altering membrane fluidity, thereby impacting immune responses [8]. Consistent with this, we demonstrated that PBMCs from ME patients exhibited heightened cytokine responses, such as IL-6, following TLR4 activation when membrane-bound SMPDL3B levels were reduced, further reinforcing its role in ME-related chronic inflammation. Treatments targeting TLR4, such as low-dose naltrexone and lithium, have shown promise in alleviating symptoms through pathway inhibition [21–23]. Additionally, the loss of membrane-anchored SMPDL3B could also impair TLR3 signaling, potentially limiting the efficacy of Ampligen in ME patients. Given TLR3’s role in antiviral immunity and immune homeostasis, it represents another potential therapeutic target in ME. Rintatolimod (Ampligen), a selective TLR3 agonist, has been investigated in this context, with Phase III trials showing variable response rates depending on disease duration [24]. However, our study did not directly assess this relationship, and further research is needed to determine whether SMPDL3B levels influence treatment response.

SMPDL3B is also a lipid-modifying enzyme that catalyzes the conversion of sphingomyelins into ceramides, which are crucial for cell membranes and signaling. Decreased membrane-anchored SMPDL3B in ME patients could explain lower plasma ceramide levels as initially reported by Naviaux’s group, including the observed sex differences, given that ceramide reduction is more pronounced in women than men [5], resulting in higher plasma sphingomyelin levels [25]. This sex-specific pattern in ceramide metabolism is consistent with our finding that women with ME exhibit higher circulating SMPDL3B levels than men, suggesting less membrane-bound form and further supporting the role of SMPDL3B in sex-related variations in sphingolipid metabolism. Muilwijk et al. demonstrated that sphingolipid concentrations exhibit age-dependent disparities between men and women, with levels increasing more rapidly in women over time. While younger women tend to have lower sphingolipid concentrations than men within the same age group, these levels surpass those of older men [26]. Similarly, studies on SMPDL3B’s role in prostate and ovarian cancers suggest distinct sex-specific regulatory mechanisms, including interactions with estrogen receptors [27–29]. Estrogen has been shown to regulate sphingolipid pathways, and our in vitro experiments suggest that estradiol modulates SMPDL3B levels. Our findings thus align with known sex-related differences in sphingolipid metabolism and ME pathophysiology [30].

One of the key mechanistic insights from our study was the altered distribution of SMPDL3B between its soluble and membrane-bound forms. ME patients exhibited reduced membrane-bound SMPDL3B on monocytes and lymphocytes, particularly in those with high circulating levels of the soluble form. This reduction correlated with increased expression of PI-PLC (PLCXD1), an enzyme known to cleave membrane-bound GPI-proteins like SMPDL3B, suggesting that heightened PI-PLC activity drives SMPDL3B shedding, leading to elevated soluble SMPDL3B levels and potentially exacerbating inflammation. We further provide the first evidence that pharmacological inhibition of PI-PLC using vildagliptin and saxagliptin restores membrane-bound SMPDL3B in immune cells. Notably, our selection of these DPP-4 inhibitors was based not on their enzymatic inhibition of DPP-4 but rather on the ability of vildagliptin to inhibit Bacillus cereus PI-PLC at micromolar concentrations [18]. By structural similarity, we extended this proof-of-concept to saxagliptin and confirmed its efficacy in inhibiting PI-PLC and preserving/restoring membrane-bound SMPDL3B, while linagliptin, used as a negative control, confirmed that this effect was not mediated by DPP-4 inhibition. Since inhibition of Bacillus cereus PI-PLC was achieved at micromolar concentrations, improved drug formulations, including transdermal approaches, may enable lower, more targeted dosing with better bioavailability. If validated in a randomized control trial, PI-PLC inhibition could represent a novel immunomodulatory strategy for ME, offering a targeted approach to restoring immune homeostasis. While other regulatory mechanisms, such as transcriptional control, post-translational modifications, or shedding by other proteases, may also influence membrane-bound and soluble SMPDL3B protein levels, our findings highlight PI-PLC-mediated cleavage as a critical driver of the depletion of membrane-bound SMPDL3B in immune dysregulation occurring in ME.

Our study has several strengths, including the use of two independent cohorts and a multifaceted approach combining clinical, molecular, and mechanistic analyses. This allowed us to uncover the altered distribution of SMPDL3B and its potential role in immune dysregulation in ME. However, we acknowledge a limitation in our study to be the sex imbalance in our cohorts, with a significant female predominance consistent with the established epidemiology of ME [31], thus limiting robust sex-specific analyses within this study. While our exploratory analyses revealed potential differences in SMPDL3B levels between sexes such as higher membrane-bound SMPDL3B on monocytes in women with ME and lower SMPDL3B gene expression in men with ME, these findings should be interpreted cautiously due to the underrepresentation of male participants and the resulting insufficient statistical power. This aligns with broader research indicating significant sex dimorphism in ME regarding prevalence, symptom presentation, and potentially underlying biological mechanisms, including hormonal influences [32]. Future studies with balanced sex ratios or dedicated sex-stratified designs are crucial to definitively elucidate potential sex-specific roles of SMPDL3B in ME pathophysiology and to determine if the observed trends hold true in adequately powered cohorts.

Notably, we identified vildagliptin and saxagliptin as promising therapeutics for restoring membrane-bound SMPDL3B through PI-PLC inhibition, a novel finding that could lead to new treatment strategies. However, there are important limitations to consider. The cross-sectional design prevents causal conclusions, and longitudinal studies are needed to determine whether SMPDL3B depletion contributes to disease progression or results from chronic inflammation. Additionally, while our focus on PBMCs provides insights into immune dysregulation, it may not capture SMPDL3B regulation across other immune cell types or tissues. Given SMPDL3B's broader roles, its depletion could also affect other organ systems, warranting further investigation. Finally, our cohorts were predominantly Caucasian, which may limit the generalizability of our findings, highlighting the need for more diverse cohorts in future studies.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that SMPDL3B may play a central role in ME pathophysiology, potentially contributing to chronic inflammation and disease severity. However, further studies are needed to determine whether these associations are causal. These findings suggest that SMPDL3B could serve as both a biomarker for disease severity and a target for therapeutic intervention. By addressing the current gaps in understanding and refining therapeutic strategies targeting SMPDL3B, we can move closer to developing more effective, personalized treatments for ME.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We extend our heartfelt gratitude to all the participants who contributed to this study and to l’Association Québécoise de l’Encéphalomyélite Myalgique (AQEM) for their invaluable support in the enrollment process. We also sincerely thank Ms. Sophie Perreault, R.N., Ms. Hélène Gagnon, R.N., Ms. Frédérique Provencher, R.N., and Mr. Patrick Perras, R.N., for their exceptional nursing assistance. We are grateful to Mr. Carl Munoz for his insightful guidance, which greatly enhanced our understanding of computer sciences and the quality of the data analysis. Special thanks to Dr. Iurie Caraus as well, for his bioinformatic assistance. This work was supported by grants awarded to Pr. Alain Moreau from The Sibylla-Hesse Foundation and The Open Medicine Foundation Canada. We also acknowledge the support for Ms. Bita Rostami-Afshari, MSc, Ms. Corinne Leveau, MSc, and Ms. Atefeh Moezzi, MSc, who are recipients of the ME Stars of Tomorrow Doctoral Bursary from The ICanCME Research Network (2023–2025), funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Additionally, Ms. Leveau is supported by a Doctoral Bursary from the CHU Sainte-Justine Foundation (2024–2025).

Abbreviations

- AKT

Ak strain transforming (Protein Kinase B)

- AQEM

Association Québécoise de l’Encéphalomyélite Myalgique

- BMI

Body mass index

- BSA

Bovine Serum Albumin

- cDNA

Complementary DNA

- CFS

Chronic fatigue syndrome

- CHU Sainte-Justine

Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Sainte-Justine

- COVID-19

Corona virus disease-19

- DMSO

Dimethyl sulfoxide

- DPN

Diarylpropionitrile

- DPP-4

Dipeptidyl peptidase-4

- DSQ

DePaul Symptom Questionnaire

- EDTA

Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid

- ELISA

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- ERβ

Estrogen receptor beta

- FBS

Fetal bovine serum

- FDA

Food and drug administration

- FSGS

Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis

- GAPDH

Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- HC

Healthy control

- HRP

Horseradish peroxidase

- IFN-β

Interferon beta

- IL-6

Interleukin-6

- LPS

Lipopolysaccharides

- ME

Myalgic encephalomyelitis

- MFI-20

Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory Questionnaire

- ng/mL

Nanogram per milliliter

- NK

Natural killer

- OR

Odd’s ratio

- PBMCs

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells

- PBS

Phosphate-buffered saline

- PEM

Post-exertional malaise

- PI-PLC

Phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C

- PLCXD1

Phosphatidylinositol specific phospholipase C X domain containing 1

- PVDF

Polyvinylidene fluoride

- QIFIKIT

Quantitative analysis kit

- qPCR

Quantitative polymerase chain reaction

- RIPA

Radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer

- RNA

Ribonucleic acid

- ROC

Receiver-operating characteristic curve

- RPMI

Roswell park memorial institute medium

- SDS

Sodium dodecyl sulfate

- SDS-PAGE

Sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- SEM

Standard error of the mean

- SF-36

36-Item Short-Form Health Survey

- TBST

Tris-buffered saline with Tween 20

- TLR3

Toll-like receptor 3

- TLR4

Toll-like receptor 4

- TNF-α

Tumor necrosis factor alpha

Author contributions

BRA, WE, AF, ME, M-YA, and Pr. A Moreau designed the research project; BRA carried out the experiments and analysis; ØF and OM, provided Norwegian samples and the respective data analysis; BRA, WE, AM, IB, PR, CL and Pr. A Moreau contributed to the interpretation of date; BRA, ME, M-YA, AF, AM, CL, WE, IB, PR, and Pr. A Moreau all contributed to the writing of this paper. All co-authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from The Sibylla-Hesse Foundation and Open Medicine Foundation Canada, awarded to Pr. Moreau.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of CHU Sainte-Justine (protocol #4047). Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Pr. Moreau is Director of Interdisciplinary Canadian Collaborative Myalgic Encephalomyelitis (ICanCME) Research Network, a national research network funded by The Canadian Institutes of Health Research (Grant MNC—166142 to Pr. Moreau). Pr. Moreau, Dr. Fluge and Pr. Mella are members of the Scientific Advisory Board of the Open Medicine Foundation (USA). The authors declare no other competing interests.

Footnotes

The original online version of this article was revised: the original publication contained errors in Fig. 4 and the caption for Fig. 2.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

8/14/2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: 10.1186/s12967-025-06900-w

References

- 1.Valdez AR, Hancock EE, Adebayo S, Kiernicki DJ, Proskauer D, Attewell JR, et al. Estimating prevalence, demographics, and costs of ME/CFS using large scale medical claims data and machine learning. Front Pediatr. 2018;6:412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Canada OMF. Qu’est-ce que l’EM 2022. Available from: https://www.omfcanada.ngo/quest-ce-que-lem-sfc/?lang=fr.

- 3.Yang T, Yang Y, Wang D, Li C, Qu Y, Guo J, et al. The clinical value of cytokines in chronic fatigue syndrome. J Transl Med. 2019;17(1):213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Germain A, Ruppert D, Levine SM, Hanson MR. Metabolic profiling of a myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome discovery cohort reveals disturbances in fatty acid and lipid metabolism. Mol Biosyst. 2017;13(2):371–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Naviaux RK, Naviaux JC, Li K, Bright AT, Alaynick WA, Wang L, et al. Metabolic features of chronic fatigue syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113(37):E5472–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dakal TC, Xiao F, Bhusal CK, Sabapathy PC, Segal R, Chen J, et al. Lipids dysregulation in diseases: core concepts, targets and treatment strategies. Lipids Health Dis. 2025;24(1):61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nkiliza A, Parks M, Cseresznye A, Oberlin S, Evans JE, Darcey T, et al. Sex-specific plasma lipid profiles of ME/CFS patients and their association with pain, fatigue, and cognitive symptoms. J Transl Med. 2021;19(1):370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heinz LX, Baumann CL, Koberlin MS, Snijder B, Gawish R, Shui G, et al. The lipid-modifying enzyme SMPDL3B negatively regulates innate immunity. Cell Rep. 2015;11(12):1919–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Merscher S, Fornoni A. Podocyte pathology and nephropathy - sphingolipids in glomerular diseases. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2014;5:127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fluge O, Rekeland IG, Lien K, Thurmer H, Borchgrevink PC, Schafer C, et al. B-lymphocyte depletion in patients with myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome: a randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2019;170(9):585–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ware JE Jr. SF-36 health survey update. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000;25(24):3130–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smets EM, Garssen B, Bonke B, De Haes JC. The Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory (MFI) psychometric qualities of an instrument to assess fatigue. J Psychosom Res. 1995;39(3):315–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jason LA, Sunnquist M, Brown A, Furst J, Cid M, Farietta J, et al. Factor analysis of the depaul symptom questionnaire: identifying core domains. J Neurol Neurobiol. 2015;1(4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Chakraborty S, Rendon-Ramirez A, Asgeirsson B, Dutta M, Ghosh AS, Oda M, et al. The dipeptidyl peptidase IV inhibitors vildagliptin and K-579 inhibit a phospholipase C: a case of promiscuous scaffolds in proteins. F1000Research. 2013;2:286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chrousos GP. Stress and sex versus immunity and inflammation. Sci Signal. 2010;3(143):pe36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Soares CN. Menopause and mood: the role of estrogen in midlife depression and beyond. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2023;46(3):463–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Light AR, White AT, Hughen RW, Light KC. Moderate exercise increases expression for sensory, adrenergic, and immune genes in chronic fatigue syndrome patients but not in normal subjects. J Pain. 2009;10(10):1099–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hwang JH, Lee JS, Oh HM, Lee EJ, Lim EJ, Son CG. Evaluation of viral infection as an etiology of ME/CFS: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Transl Med. 2023;21(1):763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Triantafilou K, Triantafilou M. Coxsackievirus B4-induced cytokine production in pancreatic cells is mediated through toll-like receptor 4. J Virol. 2004;78(20):11313–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fairweather D, Yusung S, Frisancho S, Barrett M, Gatewood S, Steele R, et al. IL-12 receptor beta 1 and Toll-like receptor 4 increase IL-1 beta- and IL-18-associated myocarditis and coxsackievirus replication. J Immunol. 2003;170(9):4731–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hummig W, Baggio DF, Lopes RV, Dos Santos SMD, Ferreira LEN, Chichorro JG. Antinociceptive effect of ultra-low dose naltrexone in a pre-clinical model of postoperative orofacial pain. Brain Res. 2023;1798: 148154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sakrajda K, Langwinski W, Stachowiak Z, Ziarniak K, Narozna B, Szczepankiewicz A. Immunomodulatory effect of lithium treatment on in vitro model of neuroinflammation. Neuropharmacology. 2025;265: 110238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gao J, Lin C, Zhang C, Zhang X, Wang Y, Xu H, et al. Exploring the function of (+)-naltrexone precursors: their activity as TLR4 antagonists and potential in treating morphine addiction. J Med Chem. 2024;67(4):3127–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Strayer DR, Carter WA, Stouch BC, Stevens SR, Bateman L, Cimoch PJ, et al. A double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized, clinical trial of the TLR-3 agonist rintatolimod in severe cases of chronic fatigue syndrome. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(3): e31334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xiong R, Gunter C, Fleming E, Vernon SD, Bateman L, Unutmaz D, et al. Multi-’omics of gut microbiome-host interactions in short- and long-term myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome patients. Cell Host Microbe. 2023;31(2):273-87e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Muilwijk M, Callender N, Goorden S, Vaz FM, van Valkengoed IGM. Sex differences in the association of sphingolipids with age in Dutch and South-Asian Surinamese living in Amsterdam, the Netherlands. Biol Sex Differ. 2021;12(1):13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Song B, Jiang Y, Lin Y, Liu J, Jiang Y. Contribution of sphingomyelin phosphodiesterase acid-like 3B to the proliferation, migration, and invasion of ovarian cancer cells. Transl Cancer Res. 2024;13(4):1954–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Parkes JE, Boehler JF, Li N, Kendra RM, O’Hanlon TP, Hoffman EP, et al. A novel estrogen receptor 1: sphingomyelin phosphodiesterase acid-like 3B pathway mediates rituximab response in myositis patients. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2023;62(8):2864–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Taneja V. Sex hormones determine immune response. Front Immunol. 2018;9:1931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liang J, Zhang B, Hu Y, Na Z, Li D. Effects of steroid hormones on lipid metabolism in sexual dimorphism: a Mendelian randomization study. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022;13:1119154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Faro M, Saez-Francas N, Castro-Marrero J, Aliste L, Fernandez de Sevilla T, Alegre J. Gender differences in chronic fatigue syndrome. Reumatol Clin. 2016;12(2):72–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thomas N, Gurvich C, Huang K, Gooley PR, Armstrong CW. The underlying sex differences in neuroendocrine adaptations relevant to Myalgic Encephalomyelitis Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2022;66: 100995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.