Abstract

Background

Physical activity and nutrition are modifiable risk factors associated with a range of mental health and psychosocial outcomes in older adults. This trial evaluated the efficacy of a multicomponent digital health promotion intervention in reducing levels of psychological distress among adults aged 60+ years.

Methods

The MovingTogether intervention is a Facebook- and eHealth-delivered intervention, facilitated by allied health professionals, and incorporates healthy lifestyle education, tailored exercise guidance (including balance training), and social support. Participants (n = 80) aged 60+ years were randomly assigned to the intervention (n = 39) or waitlist control (n = 41) in a 1:1 ratio, treating household couples as one unit. The primary outcome was psychological distress and secondary outcomes included physical activity levels, social capital, concern about falling, loneliness, physical functioning, quality of life and physical activity enjoyment. Outcomes were measured at baseline, postintervention (Week 11) and at follow-up (Week 16) via self-report, online questionnaires. Linear mixed models and an intention-to-treat approach were applied to determine between-group differences. Adherence, retention and adverse events were also tracked, and participant experience interviews were evaluated through a directed qualitative content analysis.

Results

The MovingTogether intervention significantly reduced psychological distress in the intervention group compared to the control postintervention, with a medium effect size [mean change between groups = 2.34, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.25, 4.43, P = .03, Cohen’s d = 0.59]. Change was maintained at follow-up (mean change between groups = 2.02, 95% CI: 0.27, 3.77, P = 0.03, Cohen’s d = 0.31). No significant changes were found in secondary outcomes. Thirty-one (39%) participants dropped out of the study by the postprogramme point.

Conclusion

The results suggest multicomponent digital health promotion interventions, combining lifestyle education, physical activity and social support, can improve the mental health of older adults. More research is needed to understand how to best utilise digital engagement strategies and improve retention in physical activity programmes for older adults.

Keywords: mental health, distress, physical activity, nutrition, falls, older people

Key Points

This trial evaluated a multicomponent digital health promotion for older adults.

The intervention was guided by mental-health-informed principles, emphasising enjoyment, social support and autonomy.

The intervention significantly improved psychological distress, which was maintained 1 month postintervention.

No secondary health outcomes changed following the intervention.

The results emphasise the need to explore tailored methods to increase retention, especially for groups at risk of nonadherence.

Introduction

By 2030, one in six people will be aged over 60 years [1]. People in this age group face an increased risk of age-related health issues, including poor mental health [2]. Around 14% of older adults live with a mental disorder, accounting for 10.6% of the total disability-adjusted life years in this age group [1]. One in three adults over the age of 60 years experiences depressive symptoms [3], and ~26% self-report anxiety [4]. Additionally, a quarter of suicides occur in older adults (27.2%) [1]. Improving mental health in older adults can be challenging due to the complexity of symptoms, reluctance to seek help and medication nonadherence in some cases [5].

Poor mental health can be due to a combination of risk factors, including physical inactivity, poor diet, loneliness, social isolation, falls and concern about falling [6, 7]. Social isolation and loneliness e.g. can increase the risk of depression [8]. In addition, one in three older adults fall annually, further contributing to psychological consequences [6]. Concerns about falling can exacerbate mental health challenges, through activity avoidance and increased feelings of isolation. Depressive symptoms and concerns about falling have been shown to increase the risk of falling, independently from antidepressant use [9].

To improve mental health, multicomponent health promotion interventions should target different behavioural risks for psychological distress [10]. Physical activity has been shown to reduce symptoms of depression and suicidality in older adults [11, 12]. Additional mental health benefits are seen in mental health-informed programmes that include a social component, are enjoyable, focus on leisure-time physical activity and promote autonomy [13]. Additionally, balance exercise can reduce the rate of falls in community-dwelling older adults and StandingTall is one example of an acceptable and feasible eHealth app that reduces the rate of falls [14, 15]. Dietary interventions with a focus on education and behaviour change have been found to improve mental health as well [16].

Leveraging this knowledge, technology-based interventions have emerged as a promising avenue for delivering health-promoting programmes to older adults [17]. Examples include social media platforms, which have been used to successfully change exercise behaviours and improve mental outcomes [18]. We previously developed a Facebook-delivered, pilot intervention to promote physical activity and diet behaviours among older adults. The programme was feasible, acceptable and exhibited preliminary efficacy for reducing levels of psychological distress and improving quality of life, physical activity levels, loneliness and physical functioning [19]. By integrating evidence-based interventions with technology, such as the StandingTall programme [14], we can address the multifaceted health needs of older adults in an accessible and potentially scalable manner.

This randomised controlled trial (RCT) evaluated the efficacy of a mental-health-informed, multicomponent digital health promotion intervention, including physical activity and healthy eating, in reducing levels of psychological distress among adults aged 60+ years. Secondary outcomes included physical activity, social capital, physical functioning, loneliness, quality of life, concern about falling and physical activity enjoyment. Adherence, retention, adverse events and participant experiences were also measured.

Methods

Ethical approval was obtained from the University of New South Wales Human Research Ethics Committee on 17 September 2021 (HC210654). This trial was prospectively registered on the Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry on 29 September 2021 (ACTRN12621001322820p).

The trial protocol has been published and describes the methodology in greater detail [20] as guided by the Template for Intervention Description and Replication checklist. Reporting of the trial results adhered to the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) checklist (see Appendix 1 in the online supplementary material).

Design

A two-arm, waitlist control RCT was conducted. Participants were randomly assigned (1:1) to either the intervention group or the waitlist control group. Three sets of couples were treated as one unit per pair, as per the protocol. Additionally, two participants randomised to the intervention group informed researchers of acute contraindications to exercise before starting the intervention and were excluded postrandomisation. They were offered an option to participate in the waitlist group’s iteration of the programme after data collection. Randomisation took place after eligibility screening using randomly permuted blocks of two, four and six using an online computer generator [20]. An investigator not involved with recruitment or screening set up the randomisation schedule. The investigator involved in randomisation was blinded to participant identities. Trial participants were not blinded to their allocation. The intervention group included n = 39 participants and the waitlist control group n = 41.

Recruitment

Participants were recruited through targeted online and print advertisements, predominantly age-targeted Facebook advertisements, between February and June 2022. The recruitment strategy has been described previously [20].

Individuals were considered eligible if they met the following inclusion criteria: (i) they were aged 60+ years, (ii) they were proficient in written and spoken English, (iii) they lived independently in the community in Australia, (iv) they were able to mobilise indoors without a walking aid, (v) they had access to the Internet, (vi) they had Facebook and either a computer, laptop or iPad/tablet access and (vii) they self-reported participating in less than 150 minutes of moderate- to vigorous-intensity physical activity per week, assessed with the Physical Activity Vital Sign Questionnaire [21].

Individuals were excluded from the study if they met one of the following criteria: (i) high levels of psychological distress (score of >30 on the K10) unless deemed to have support from a mental health professional, (ii) high risk of suicidal behaviour (score of >21 on the Suicidal Ideation Attributes Scale) unless deemed eligible to participate by a clinical psychologist through a suicide risk assessment, (iii) absolute contraindications to exercise according to the American College of Sports Medicine or relative contraindications (identified with the Exercise Sport Science Australia Physical Activity Readiness Scale embedded in the Demographics Questionnaire), without accredited exercise physiologist (AEP) clearance to exercise [22, 23], (iv) participating in a fall prevention programme at least weekly, (v) signs of cognitive impairment (score < 4) as assessed by a cognitive impairment screen [the Ottawa 3DY (Ottawa day, date, dlrow, year)] [24] and (vi) diagnosis of a progressive neurological condition.

Sample size

A power calculation was conducted using General Linear Mixed Model Power and Sample Size (GLIMMPSE) [20, 25, 26] based on K10 pilot study data [19]. A sample size of n = 80 assumed standard deviation (SD) = 6.41, correlation between repeated values of 0.6 with 80% power for a moderate effect and a 15% dropout rate.

Intervention

The intervention was underpinned by the Capability, Opportunity, Motivation-Behaviour (COM-B) model of behaviour change [27]. The MovingTogether intervention was facilitated by allied health professionals and comprised (i) a Facebook-delivered healthy lifestyle education and support group, (ii) an eHealth fall prevention programme (StandingTall) and (iii) an aerobic and strength exercise programme tailored to each participant which prioritised the principles of mental-health-informed physical activity.

Facebook-delivered healthy lifestyle education and support group

Participants joined a private Facebook group, where they received targeted education and resources from AEPs and an accredited practising dietitian on various topics [28]. Facilitators used three to seven posts per week in the Facebook group to convey text, infographics and video mediums [20]. Each post took less than 10 minutes to read/watch. Topics included overcoming barriers, goal setting, reducing sedentary behaviour, increasing physical activity and increasing structured exercise, balance training and nutrition based on behaviour change techniques [20, 27]. These topics were based on proven behaviour change techniques and intended to foster interaction and support among group members. The intervention also offered two optional weekly 20–30 minute group video calls [19, 28], led by facilitators to further promote social connection between participants and to discuss educational resources. Participants were encouraged to support others in the group as encouraged in previous trials [19, 28]. Posts and video calls encouraged meeting physical activity guidelines and balance training recommendations of 2 hours per week [29]. The Facebook group created opportunity for participants to engage in physical activity, education-targeted health literacy to enhance capability to participate and social-support-facilitated motivation to engage.

StandingTall

Participants were provided with a home-based balance training programme through the StandingTall app [14]. In the initial 2 weeks, participants took part in a guided StandingTall balance assessment through a one-on-one video call with an AEP and a sample StandingTall session through a small group video call. After the assessment, the app generated an individualised, tailored exercise programme for each participant based on their baseline balance assessment. When training, the app guided participants throughout their entire session with animation and countdown clocks in real time. The programme was designed to be challenging yet suitable for participants’ abilities and automatically progressed based on the reported rate of perceived exertion during training. Participants were able to contact AEPs for exercise modifications if needed and were encouraged to complete at least 2 hours of balance training per week. Time spent exercising on the app was tracked through website analytics. The accessibility of an app that offers real-time guidance promoted the opportunity to engage in behaviour change.

Strength and aerobic exercise

Additionally, participants were invited to access tailored AEP advice and exercise programmes, taking into account each participant’s unique health needs and activity interests [30]. Exercise programmes ranged in modalities, recommended dependant on participant needs, health and goals. Options included strength, aerobic, mixed strength and aerobic, aqua-based and flexibility exercise programmes. The aim was to encourage participants to engage in physical activity that met the recommended guidelines of 150 minutes of moderate to vigorous activity per week. However, if this goal was not achievable or facilitators deemed this was not in line with mental-health-informed physical activity, the exercise programme was modified accordingly [31]. Expert advice allowed participants the autonomy and capability to independently engage in physical activity during the programme and encouraged lasting behaviour change postprogramme.

Waitlist control protocol

Following the week 14 follow-up assessment, the waitlist control group was invited to join a private Facebook group separate from the Facebook group used by the intervention group, and completed the facilitated intervention without additional questionnaires completion.

Outcomes

Surveys

Participants completed all the questionnaires at baseline, postintervention and at the 1-month follow-up point online though REDCap. It took ~45 minutes for participants to complete questionnaires at each time point.

Participant characteristics

Participant characteristics and demographics were reported using a short questionnaire. Questions asked for participants’ age, gender, residing Australian state, education, employment level, living situation, walking aid use, falls history and existing health conditions.

Psychological distress

The K10 is a 10-item tool that evaluates a participant’s psychological distress over the past 4 weeks [32]. A five-level response scale with corresponding numerical values was used. Total scores range between 10 (no distress) and 50 (severe distress). The K10 has demonstrated appropriate psychometric properties and is sensitive to predict mental health diagnoses in older adults [32, 33].

Physical activity

The 10-item Incidental and Planned Exercise Questionnaire (IPEQ) was devised and validated in older adults to capture the self-report frequency and duration of planned and incidental physical activities over a recent 1-week time period. Each question allowed participants to choose one from six to seven responses of activity participation, frequency or duration. This questionnaire has good reliability and an acceptable internal consistency [34].

Social capital

The Brief Social Resources Questionnaire [35] includes questions on both objective and subjective social resources that comprise social capital. Three social network questions were adapted from the Lubben Social Network Scale-6 [36] to measure objective social interactions, e.g. ‘With how many other people do you live?’ The remaining three were adapted from the Duke Social Support Index-10 [37] to focus on social support and the participants’ perceptions of their social interactions, e.g. ‘How socially supported do you feel?’ Responses to each of the six items were standardised. Both the Lubben Social Network Scale-6 and the Duke Social Support Index-10 have been validated extensively in older adults [36, 37].

Concern about falling

The Iconographical Falls Self-Efficacy Scale (Icon-FES) is a 30-item questionnaire that uses pictures and words to evaluate concern about falling while completing activities of daily living. Four response options were available to all questions about fall concern (‘not at all concerned’ to ‘very concerned’), and questions about activity avoidance (‘no never’ to ‘yes always’). This scale has high internal consistency, excellent test–retest reliability and sensitivity to predict high concern about falling and risk of falling in older adults [38].

Loneliness

Loneliness and social isolation was evaluated through the 20 questions of the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) Loneliness Scale [39]. Responses are on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from ‘never’ to ‘often’. A total score over 25 represents a high level of loneliness and 30 or higher indicates a very high level of loneliness. Moderate-quality evidence has shown the scale is reliable and valid to assess loneliness in older adults [39].

Quality of life

The European Quality of Life Five Dimensions (EQ-5D-5L) comprises five areas of living, with one item for each, including mobility, self-care, usual activities like work and housework, pain and/or discomfort and anxiety and/or depression [40]. Each question had five possible responses ranging from ‘no problems’ to ‘unable’ to complete activity or ‘extreme’ experience of mental health problems or pain. Extensive evidence concluded excellent psychometric properties and moderate to strong correlations with physical/functional health, pain, activities of daily living and clinical biological measures [41].

Physical functioning

The functional component of the Late Life Function and Disability Instrument (LLFDI) was used [42]. There are 32 items with responses on a five-point Likert scale ranging from ‘never’ to ‘often’. Higher scores are indicative of increased difficulty performing physical and functional tasks. The functional component has high test–retest reliability and has been validated in older adults with moderate to strong correlations with multiple performance-based mobility measures [43].

Enjoyment

The Physical Activity Enjoyment Scale (PACES) includes 18 questions, answered on a seven-point bipolar rating scale [44].

Process evaluation

Adherence

Participant adherence to balance exercise training was recorded. Average weekly balance training duration and total training duration were recorded through the StandingTall app [14]. Adherence to individualised aerobic and strength programmes was also recorded. This was assessed using a survey at the postintervention assessment point asking participants the average frequency and duration of individualised programme completion per week. Other data collected included the number of participants who viewed, reacted to and commented on each educational Facebook post. Demographic data was also compared between dropouts who did not complete postprogramme questionnaires and completers who completed the questionnaires. Dropouts were contacted and then sent a reminder on an additional occasion before dropout status was confirmed.

Adverse events

Participants were encouraged at the beginning to contact the research team either via email, in group calls or private Facebook messages to report any accidents or changes to their health.

Interviews

Participants from both groups were invited to participate in an optional 15–20 minute one-on-one semistructured interview via Zoom. The aim was to gain practical feedback about how the intervention can be improved. Participants were asked about their experience participating in the intervention and what they perceived to be the intervention’s strengths and weaknesses. Interviewers asked about positive or negative experiences with the programme and the different programme components, any perceived benefits or lifestyle changes from the programme, ways the programme could be improved and factors that affected their engagement. The interview schedule can be found in (see Appendix 2 in the online supplementary material). Interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim, removing identifying information, and uploaded to NVivo12 (QSR International, Melbourne, Australia) for analysis.

Statistical analyses

Quantitative analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS 25.0. Intention-to-treat analyses with linear mixed modelling were conducted to test the efficacy of the intervention. Group (intervention vs control), time and group by time were added as fixed effects and subject as a random effect to the model. The mean differences between the intervention and control groups on primary and secondary outcomes postintervention and at follow-up assessments were calculated with 95% confidence intervals (CIs; without Bonferroni corrections), controlled for the baseline level of each outcome respective of the focus of the analysis: e.g. baseline psychological distress levels were controlled for in the analysis of psychological distress change. Linear mixed modelling was chosen over other traditional methods as it uses maximum likelihood estimations by handling missing data to include all the available observations in the data, preventing potential power loss due to the missingness in data [45]. Chi-square tests were used to assess predictors of outcome missingness, by comparing demographic characteristics between questionnaire completers and dropout groups. Cohen’s d was calculated by dividing the mean difference between the groups by the pooled SD at that assessment.

A directed qualitative content analysis was performed on interview data [46]. The first step involved defining the categories to be applied whereby categories are patterns or themes directly mentioned by participants or derived from quotes through analysis. Next, we outlined and implemented the coding process, determined trustworthiness and analysed the results of the coding process. Once themes were defined, they were reviewed and revised by two members of the research team (C.M. and G.M.).

Results

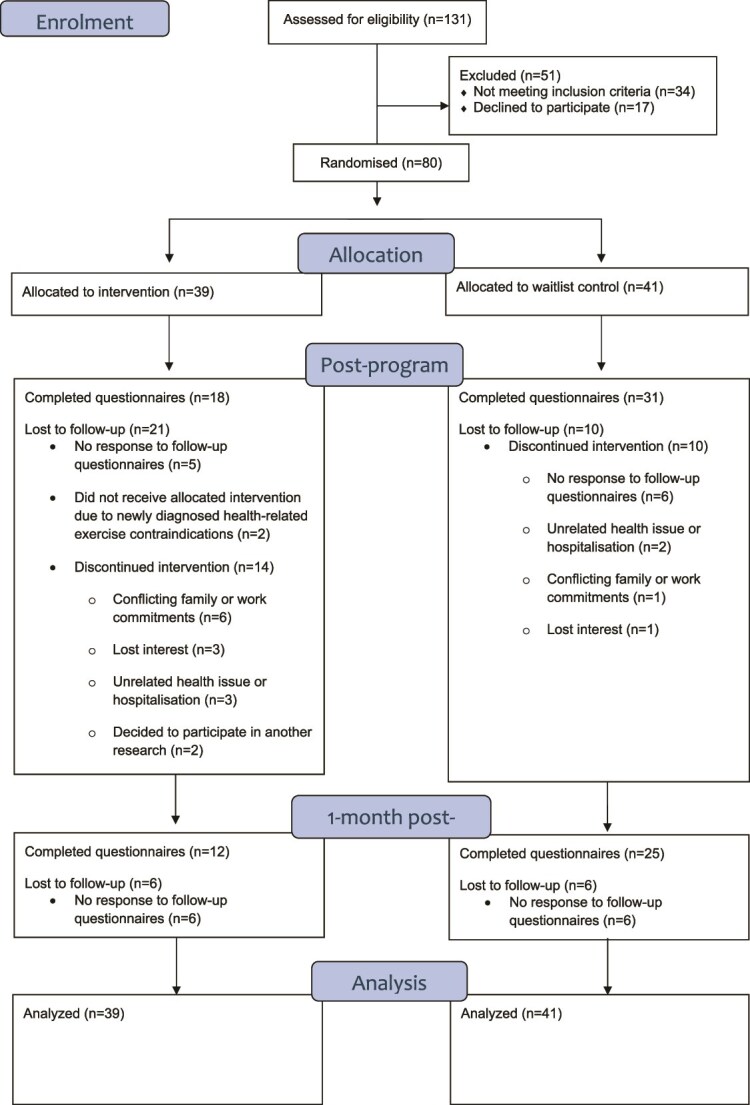

A total of 131 people were screened, with 51 people excluded due to ineligibility (n = 34) or no response after expressing initial interest (n = 17) (see Figure 1). The remaining 80 were randomised to the intervention (n = 39) or waitlist control group (n = 41). Recruitment started in February 2022 and ended in June 2022 after 80 participants were screened eligible and consented to the study.

Figure 1.

Participant progress through enrolment, intervention allocation, follow-up and data analysis using the CONSORT flow diagram template (Altman et al. 2001).

Of the 80 participants randomised, two (2.5%) were diagnosed with a health-related exercise contraindication after randomisation and therefore did not receive the allocated intervention. In total, 31 (39%) were lost to follow-up before the postprogramme assessment and 43 (54%) were lost to the 1-month follow-up due to various reasons outlined in Figure 1.

Demographics and baseline characteristics

Baseline demographics and characteristics of all the participants can be seen in Table 1. Females comprised 89% (n = 71) of the sample and 30% (n = 24) lived alone. The mean age of participants was 66 years (SD = 4.9). Most lived in New South Wales (NSW) (54%), were married (51%), retired (55%) and had the highest level of education of a bachelor’s degree (36%), tertiary education without completing and obtaining a degree (35%) or had completed postgraduate education (15%). Most participants used Facebook for 60 minutes or less per week (55%) at baseline. Within the last year, 18 participants (23%) reported having had a fall. At baseline, most (69%) of the sample were ‘likely to be well’ according to the K10, 18% were ‘likely to have a mild disorder’, 9% were ‘likely to have a moderate disorder’ and 4% were ‘likely to have a severe disorder’.

Table 1.

Baseline demographics and descriptive characteristics of all participants.

| Variable | Intervention group (n = 39) |

Control group (n = 41) |

Total (N = 80) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 66.9 (5.80) | 65.7 (3.83) | 66.3 (4.92) |

| Sex (female), n (%) | 34 (87) | 37 (90) | 71 (89) |

| Living alone, n (%) | 13 (33) | 11 (27) | 24 (30) |

| Smoker, n (%) | 2 (5) | 1 (2) | 3 (4) |

| Uses walking aid outdoors, n (%) | 5 (13) | 2 (5) | 7 (9) |

| Fall in the past year | 7 (18) | 11 (27) | 18 (23) |

| State of residence, n (%) New South Wales Queensland Victoria Western Australia Australian Capital Territory South Australia Tasmania Northern Territory |

21 (54) 6 (15) 3 (7) 4 (10) 2 (5) 1 (3) 1 (3) 1 (3) |

23 (56) 7 (18) 7 (18) 1 (2) 1 (2) 1 (2) 1 (2) 0 |

44 (54) 13 (16) 10 (13) 5 (6) 3 (4) 2 (3) 2 (3) 1 (1) |

| Marital status, n (%) Married Single De facto Widowed Other or prefer not to say |

22 (56) 9 (23) 1 (3) 5 (13) 2 (5) |

19 (47) 14 (34) 5 (12) 0 3 (7) |

41 (51) 23 (29) 6 (8) 5 (6) 5 (6) |

| Employment status, n (%) Retired Part time or casual Full time Other, e.g. family carer Unemployed |

25 (63) 6 (17) 3 (8) 3 (7) 2 (5) |

20 (49) 12 (29) 7 (17) 2 (5) 0 |

45 (55) 18 (23) 10 (13) 5 (6) 2 (3) |

| Education, n (%) | |||

| Year 12 or less Tertiary, but no degree Bachelor’s degree Postgraduate degree Other |

4 (11) 14 (36) 16 (41) 2 (5) 3 (7) |

3 (7) 14 (34) 13 (33) 10 (24) 1 (2) |

7 (9) 28 (35) 29 (36) 12 (15) 4 (5) |

| Facebook use per week, n (%) 0–30 minutes 45–60 minutes 70–90 minutes 100–120 minutes 120+ minutes |

8 (20) 10 (26) 4 (10) 10 (26) 7 (18) |

12 (29) 14 (34) 5 (12) 4 (10) 6 (15) |

20 (25) 24 (30) 9 (11) 14 (18) 13 (16) |

| Kessler-10, mean (SD) Kessler-10, n (%) Likely to be well Likely to have a mild disorder Likely to have a moderate disorder Likely to have a severe disorder |

17.9 (5.85) 24 (61) 10 (26) 3 (8) 2 (5) |

16.9 (5.20) 32 (77) 4 (9) 4 (12) 1 (2) |

17.4 (5.52) 56 (69) 14 (18) 7 (9) 3 (4) |

Primary outcome

Psychological distress (K10)

The mean levels of psychological distress in the intervention group decreased significantly (P = .03) from baseline to postintervention (week 11). The mean difference between the intervention and control groups was 2.34 at postintervention assessment (95% CI: 0.25, 4.36) with a medium effect size (Cohen’s d = 0.59). This was maintained at the 1-month follow-up assessment (P = .03), with a mean difference between groups of 2.02 (95% CI: 0.27, 3.77, Cohen’s d = 0.31) (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Between-group changes in the waitlist and intervention groups.

| Descriptive statistics | Mixed-model analysis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |||||

| Outcome variable | Time point | Intervention Baseline n = 39, Post n = 18 1-month n = 12 |

Control Baseline n = 41, Post n = 31 1-month n = 25 |

Difference in mean change (95% CI) | P value | Effect size |

| Kessler-10 (K10) | Baseline | 17.88 (5.85) | 16.88 (5.20) | |||

| Post | 14.39 (5.35) | 17.68 (5.85) | 2.34 (0.25, 4.43) | .03* | 0.59 | |

| 1-month | 16.38 (5.30) | 18.07 (5.67) | 2.02 (0.27, 3.77) | .03* | 0.31 | |

| The Incidental and Planned Exercise Questionnaire (IPEQ) | Baseline | 10.93 (18.66) | 17.68 (18.66) | |||

| Post | 14.20 (15.89) | 14.44 (12.82) | −0.59 (−7.74, 8.92) | .89 | 0.02 | |

| 1-month | 15.67 (14.79) | 16.46 (18.12) | −2.10 (−13.20, 9.00) | .70 | 0.08 | |

| The Brief Social Resources Questionnaire | Baseline | 17.59 (7.49) | 21.28 (10.57) | |||

| Post | 18.75 (8.31) | 18.63 (9.09) | −2.31 (−7.66, 3.04) | .18 | 0.01 | |

| 1-month | 19.44 (7.85) | 18.66 (10.26) | −5.20 (−10.68, 0.28) | .06 | 0.09 | |

| The European Quality of Life Five Dimensions (EQ-5D-5L) | Baseline | 8.69 (3.00) | 7.87 (2.45) | |||

| Post | 8.38 (3.03) | 8.21 (2.21) | −0.04 (−1.17, 1.09) | .94 | 0.06 | |

| 1-month | 8.44 (2.99) | 7.91 (2.45) | −0.63 (−1.44, 2.69) | .54 | 0.19 | |

| University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) Loneliness Scale | Baseline | 42.97 (13.52) | 42.77 (11.08) | |||

| Post | 37.63 (14.66) | 42.79 (11.01) | 2.92 (−1.71, 7.54) | .21 | 0.40 | |

| 1-month | 41.29 (12.45) | 44.12 (12.17) | 0.07 (−3.95, 4.10) | .97 | 0.23 | |

| Functional component of the Late Life Function and Disability Instrument (LLFDI) | Baseline | 68.22 (24.46) | 57.36 (16.77) | |||

| Post | 63.87 (46.41) | 57.35 (16.13) | 5.28 (−1.19, 11.76) | .11 | 0.19 | |

| 1-month | 63.12 (23.01) | 60.03 (19.06) | 3.05 (−5.90, 12.00) | .49 | 0.15 | |

| The Iconographical Falls Self-Efficacy Scale (Icon-FES) | Baseline | 101.42 (36.98) | 83.18 (18.86) | |||

| Post | 131.43 (36.98) | 94.00 (30.34) | 25.15 (−59.39, 9.10) | .14 | 1.12 | |

| 1-month | 88.31 (40.40) | 80.33 (16.04) | 3.08 (−5.51, 11.66) | .48 | 0.26 | |

| Physical Activity Enjoyment Scale (PACES) | Baseline | 70.50 (25.61) | 69.79 (19.67) | |||

| Post | 71.50 (57.03) | 65.83 (32.79) | 5.75 (−2.54, 14.04) | .17 | 0.12 | |

| 1-month | 61.94 (19.75) | 66.49 (25.85) | 3.25 (−6.02, 12.51) | .48 | 0.20 | |

Notes. K10 score range = 10–50. EQ-5D-5L score range = 5–25. UCLA Loneliness Scale score range = 0–60. Functional Component of the LLFDI score range = 32–160. IconFES score range = 30–120. PACES score range = 0–48. Significance level for the P value was set to 0.05*. Cohen’s d effect sizes were calculated based on estimated marginal means derived from the mixed models’ results. Cohen’s d effect sizes were interpreted as small (d = 0.2), medium (d = 0.5) and large (d = 0.8). Mixed models were adjusted for baseline scores.

Secondary outcomes

There were no significant between-group differences in physical activity levels, social capital, quality of life, loneliness, physical function, concern about falling or physical activity enjoyment from baseline to postintervention or at the 1-month follow-up point (week 10) (see Table 2).

Retention and adverse events

The intervention group had a programme completion rate of 59% (22 out of 37), i.e. remained in the Facebook group at the time of the last post. Fifty-nine percent of all the participants (47 out of 80) completed postprogramme questionnaires. Dropouts were participants who did not complete the postintervention questionnaires. Dropouts were older, with a mean age of 67.2 years (SD = 4.35), compared to participants who completed questionnaires (mean age 65.6, SD = 5.29). A minority (9%) of questionnaire completers spent 120+ minutes per day on Facebook at baseline, compared to 22% of dropouts. Dropouts had fewer falls in the past year (18%) compared to questionnaire completers (25%). Questionnaire completers were most ‘likely to be well’ (77%), compared to dropouts (61%). Eleven per cent of questionnaire completers and 25% of dropouts were ‘likely to have a mild or moderate disorder’ and 2% of questionnaire completers and 6% of dropouts were ‘likely to have a severe disorder’. There were no significant differences between the questionnaire completer and dropout groups.

One intervention participant reported a fall during the study period while riding their bike on a public footpath. This fall was unrelated to the intervention and the participant was not injured.

Engagement—Facebook

Facilitators posted in the group between three and seven times per week. The number of participants who viewed and reacted to each post is shown in Appendix 3 of the online supplementary material. Each facilitator-initiated post was viewed on average by 43% of participants (73% of programme completers). Engagement fluctuates throughout, with higher levels at the beginning and end of the programme. Comments on facilitator posts was the least used method to interact with the Facebook group; however, certain posts encouraging higher interaction, e.g. a poll on barriers to physical activity, recorded increased engagement. Appendix 3 in the online supplementary material displays participant engagement with facilitator-initiated Facebook posts.

Engagement—physical activity

Fourteen participants engaged in the StandingTall component of the intervention (64% of programme completers). After Week 5, these participants were completing on average 37.5 minutes (SD = 33.75) per week out of their goal of 80 minutes. After Week 10, there was an average of 18 minutes (SD = 36.57) per week being completed of a 2-hour weekly goal. On average, the total minutes of StandingTall completed by all the participants in the intervention group was 311.88 minutes (SD = 311.36) per participant. In addition to general physical activity advice and exercise guidance, tailored AEP services and exercise programmes were requested by 32% of programme completers. On average, participants used tailored exercise programs 50 minutes (SD = 41.27) per week.

Qualitative results

Eleven participants (14%) decided to participate in the optional feedback interviews postprogramme. Overall, participants discussed their positive experiences with the programme and facilitators, and how they felt the programme increased external physical activity and other healthy habits, even post-programme. Participants also discussed the negative impact of external factors on engagement, how more challenging, varied exercise was sought and specific feedback to improve the programme. Differing views were offered about the level of accountability provided as well as the facilitated social connection. Table 3 and Figure 2 provide themes and participant quotes.

Table 3.

Qualitative thematic analysis and corresponding participant quotes

| Theme | Subtheme | Quote |

|---|---|---|

| Positive experiences | Programme flexibility Friendly facilitators Accountability |

‘I liked the [StandingTall] exercises that you could just join in when it suited and they were pretty much self-explanatory. As long as I had my chair nearby and the phone, everything was set to go.’—Female, aged 71 ‘I was the one that was making comments on it rather than [Participant 7, husband]. I sort of tend to get on Facebook a bit more than [husband, Participant 7] and so I was more into the social media.’—Female, aged 66 ‘We didn’t really need to do that because we could, because we’re, [Participant 4, wife] and I were bouncing off each other. Some of the time to try and motivate ourselves.’—Male, aged 69 ‘Just that I kept thinking I can’t keep in touch with so many people that’s the other thing I’ve got about five or six really good friends and that’s what I do cause beyond that it just gets too much.’—Female, aged 60 ‘Yeah so you felt motivated enough just from the app?’—Interviewer *[Female, aged 60] nods* ‘[The facilitator] was very good actually. I really enjoyed my interaction with her. Easy to talk to and doesn’t make me sort of feel too guilty.’—Female, aged 66 ‘Actually having you know [the facilitator] overseeing it. That was motivating because there was the contact point or somebody who’s contacting me to follow up or to see what I was doing so that’s always motivating.’—Female, aged 65 ‘I was accountable to someone and myself, but it was it was just enough to really make a difference in my thinking.’—Female, aged 60 |

| Perceived benefits | Physical benefits Mental health benefits Programme increased physical activity and encouraged healthy habits outside of the programme |

‘I was in quite a bit of physical pain, because I’d been ill and getting back to exercise it was actually very well timed and the StandingTall was kind of the only exercise I was doing as well as walking to work and back from the car park, but it really got me back into being a bit balanced and I was doing it faithfully.’—Female, aged 63 ‘I was going well. Yeah, [his balance] has improved quite a bit.’—Male, aged 63 ‘It gave me something to focus on because of the challenging family things that’s been going on and it just gives you a different focus. Also, I like the fact that I was improving with standing on one leg.’—Female, aged 68 ‘I do think I’m happier. Cause I was a bit glum there for a while, probably prior to starting it.’—Female, aged 66 ‘I was more aware of trying to be more physically active and I actually started wearing my Fitbit again. I think it actually did inspire me to get my Fitbit up and running again. I’ve actually got it on today. I went for a walk.’—Female, aged 66 ‘I’m doing it on my daughter’s Wii now. It’s more than 15 minutes now it’s got up to half an hour. Every second day.’—Female, aged 60 |

| Competing life stressors affected programme engagement | Health problems Personal schedule |

‘The mental change is due to two things right. Initially with my cancer because you do worry about a lot and the second thing is the tablet itself. The thing is with the tablet. They say the side effect of it is, you feel sort of depressed or a little bit anxious so you have to watch out for all those things.’—Male, aged 63 ‘We haven’t done it for the last two or three weeks because we’ve been away for a while and then things are just starting to get busy come up to Christmas, of course, but, but we will get back to it.’—Male, aged 69 |

| Dislikes or areas for programme improvement | Accountability More challenging and varied exercise sought Increased social connection Continued support Alternative digital platform |

‘I think if I’d have been reminded a little bit more because I get busy with other things and if I was prompted a bit more, I think I would have been more diligent.’—Female, aged 66 ‘I found that the exercises were starting off so slow that I sort of felt it didn’t apply to me because I was able to do a lot of physical activity.’—Female, aged 66 ‘Well for me I don’t think it sort of was targeting enough on the balance for me that was just my one, but you?’ *gestures to husband—Female, aged 66 ‘Like a variety, a greater variety or more frequent exercise, exercise set. Like, just add to, just to vary it up a bit.’—Male, aged 66 ‘If you cross them in some way, so that people from the different groups might be able to share any commonality or any differences or anything. A bigger group rather than having two separate groups.’—Female, aged 63 ‘If there was contact or top up information every three months or six months just to see if anything’s changed. Say if in any of your findings you you see that you know there’s things that we could change behaviour or something . . . Yes and can let you know if there’s anything that could change because I think while I understand it’s a study and the purpose of the study is you know having started it and I don’t want to just stop and say oh well that’s done and in the past. You want to keep going but if there’s any changes or developments or things that you find that’ll be useful.’—Female, aged 65 ‘We haven’t done it for probably months now, and it’s because the programme’s finished. I’m not being held accountable.’—Female, aged 68 ‘I think there might be partly, not an age thing, but a generational thing, so most people most people doing this, are probably, are less Facebook and social media orientated compared to young, like the next younger generation.’—Male, aged 69 ‘I must say I didn’t really interact with the Facebook group.’—Female, aged 71 ‘Is that because it was online and you prefer, social interaction face to face sort of interaction?’—Interviewer ‘No, not really. I’ve been in a number of Facebook groups and it was just another one and yeah I just didn’t feel the need to get one in there.’—Female, aged 71 |

Figure 2.

Summary of qualitative themes, subthemes and exemplar quotes.

Positive experiences with the programme involved accountability from enrolment, facilitators and other participants, friendly facilitators and programme flexibility. While participants valued being ‘accountable to someone’ to allied health facilitators, approachable facilitators were specifically important for positive experiences, ‘I really enjoyed my interaction with [AEP]. Easy to talk to and doesn’t make me sort of feel too guilty.’

A range of benefits, including physical and mental health benefits, were reported, although only significant mental health benefits were reflected in quantitative data. For example, physical activity levels were said to increase; however, no significant changes in quantitative physical activity records were observed. Another benefit captured in interviews that may not have been deduced in questionnaire responses included engagement in activities outside the programme, sometimes even after the end of the programme, ‘I’m doing it on my daughter’s Wii now. It’s got up to half an hour. Every second day.’

Participants also reflected on some reasons why they may not have engaged in the programme as much as they were intending to. Reasons were often related to health challenges and competing personal schedules, ‘We haven’t done it for the last 2 or 3 weeks because we’ve been away for a while and then things are just starting to get busy come up to Christmas, of course, but, but we will get back to it.’.

Mixed feedback revealed the need for increased tailoring in all aspects of the programme, with suggested areas for improvement by some participants commonly being factors reported as positive experiences for others. The level of accountability and social connection, varied exercises, alternative digital platforms and continued support following the programme were all listed as possible areas of improvement, ‘I think there might be partly, not an age thing, but a generational thing, so most people most people doing this, are probably, are less Facebook and social media orientated compared to young, like the next younger generation.’

Discussion

Principal results

A 10-week multicomponent digital health promotion programme (MovingTogether) significantly reduced levels of psychological distress in adults over 60 years postintervention when compared to a waitlist control group. Change was maintained at the 1-month follow-up point. No significant changes were found for secondary outcomes, including physical activity levels, social capital, concern about falling, loneliness, physical functioning, quality of life and physical activity enjoyment.

Qualitative feedback from participants provided depth and context to the quantitative findings. Interviews highlighted participants were encouraged to engage in various activities outside of the programme and sometimes initiated changes postprogramme, such as starting a type of exercise class. Although the intervention group had increased physical activity levels compared to the control group, this change was not significant. Discussion around social support and accountability revealed the diversity in needs and expectations of participants such as motivation levels, which should be measured and further tailored in future studies. For example, some participants expressed they would have liked more social support from the Facebook group, while others were satisfied by simply observing the activity in the Facebook group. The initial one-on-one call with the study AEP for a balance assessment could be expanded for an extended consult. The purpose would be to discuss the motivation for joining the programme and plan for increased tailoring throughout the remainder of the programme.

Comparison with prior work

Contrary to previous studies suggesting that multicomponent physical activity programmes for adults over 65 years old can improve health outcomes, including function and quality of life [47], we did not find significant changes in outcomes besides psychological distress. Our intervention included components that have demonstrated success in other healthy ageing interventions such as multicomponent and multiprofessional team approaches to intervention design and delivery [47], designed to encourage participants to choose enjoyable physical activities and approaches to a healthier dietary pattern to optimise potential mental health benefits. While reductions in psychological distress were observed, we did not design the study to isolate the effects of individual components. Given that all the components are interrelated and linked to mental health benefits [11, 12, 16], it is likely the combination and flexibility of the components contributed to distress reduction, rather than one specific component alone. A recent study investigated lifestyle behaviour clusters (engaging in multiple lifestyle changes) and observed a dose–response relationship between engaging in more than one lifestyle change and fewer symptoms of poor mental health [48]. Furthermore, qualitative feedback indicated that some participants would have enjoyed more increased social connection. The importance of group cohesion and social support in increasing exercise adherence among older adults is well established, providing individualised health benefits and tailored advice [49].

Online group physical activity programmes highlight the potential of using e-Health for exercise interventions to facilitate social support and interaction within programmes for potential increased benefit. Our MovingTogether supports existing evidence that both exercise and social support are important for psychological well-being [50]. For example, the Mood Lifters for Seniors study found significant decreases in depression and stress symptoms of older adults in response to an online programme that included weekly peer-led group calls with discussion of topics including exercise and relationships with others [50]. Incorporating peer facilitation could enhance our programme, responding to the diverse social support needs and accountability preferences indicated by participant feedback. Previous peer-led physical activity interventions for older adults have demonstrated favourable outcomes, suggesting this could be a valuable addition to our allied health facilitator-led model [50].

There was a high rate of participants lost to follow-up after 10 weeks [n = 31 (39%)]. Although high, this is lower than other online trials. For example, a programme with online exercise sessions for adults over 4 weeks had 54% of participants drop out, despite the sessions being easily accessible through live stream and the participants being free of barriers related to health conditions [51]. Trials involving older people often have higher dropout rates [52], which can commonly be due to reasons directly related to psychological distress [52]. Notably, in our study, those who dropped out tended to have higher scores of psychological distress, suggesting a potential link to mild, moderate or severe mental disorders.

Limitations

We had a higher than expected dropout rate, with 36% lost to follow-up after 10 weeks compared to the 15% accounted for in power calculations. Predictors of dropout were assessed between participants who completed the postprogramme assessments and participants who did not, with no significant differences between these two groups. However, this approach does not refute the possibility that there might be unobserved variables explaining the difference between these groups. Therefore, future studies should explore other potential factors that might contribute to attrition and data completeness. Also, despite nutrition content included in the intervention, our study did not measure participants’ diet quality or eating habits to reduce the questionnaire burden on participants.

Multiple sample limitations were identified, including that our sample was technologically literate and willing to take part in the physical activity programme. While it was important that participants could use Facebook and the StandingTall programme, the transferability to other populations, such as older adults who do not use social media, is unknown. However, to reach older adults with varying levels of technology use, various recruitment methods were used. There were no specific strategies employed to address cultural diversity or language differences as this was beyond the scope and resources of the study. Recruiting participants who did not speak English would have impeded their ability to fully engage in the programme, including both the content and social components.

Additionally, we note a deviation from the original protocol, which planned for subgroup analyses and analyses of cognitive data. Subgroup analyses were not completed due to the reduced statistical power resulting from the high dropout rate. Practical issues encountered while administering the cognitive assessment via Inquisit 6 computer software led to a reduced response rate at all time points and therefore data was not accurately indicative of the sample [20].

Directions for future research

As this work did not assess the effect of the different components separately, future research could explore the individualistic mechanisms behind these, while still acknowledging the importance of considering the effect of lifestyle clusters, to inform further trials. Considering digital delivery via social media has the potential to be low-cost, low-resource and scalable, future trials should focus on investigating methods to improve retention. Given the high dropout rate and mixed qualitative feedback, future research should investigate implementing personalised engagement strategies. Participant feedback surrounded improving accountability, social connection and offering alternative platforms to Facebook. Feedback warrants exploring the preprogramme motivation, programme expectations, barriers to physical activity, topics of interest and preferred communication styles, which may vary among individuals. Additionally, gamification and wearable technologies could be explored to monitor real-time physical activity to enhance engagement and adherence to exercise programmes and could facilitate a more precise measurement of physical activity levels [18]. Finally, investigating the efficacy and acceptability of peer-led models in addition to professional-led interventions could provide valuable insights into how best to structure support within these programmes to maximise engagement and impact.

Conclusions

A multicomponent digital health promotion intervention combining lifestyle education, physical activity and social support can improve the mental health of older adults. More research is needed to focus on how best to utilise Facebook features for delivery and to improve retention in physical activity programmes for older adults. Facebook engagement warrants further exploration for utilising balance training, social support and/or social media delivery for older adults’ mental health.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Chiara Mastrogiovanni, Discipline of Psychiatry and Mental Health, School of Clinical Medicine, University of New South Wales, Sydney, NSW, Australia.

Simon Rosenbaum, Discipline of Psychiatry and Mental Health, School of Clinical Medicine, UNSW Sydney, Sydney, NSW, Australia.

Kim Delbaere, Falls, Balance and Injury Research Centre, Neuroscience Research Australia, UNSW Sydney, Sydney, NSW, Australia; School of Population Health, UNSW Sydney, Sydney, NSW, Australia.

Anne Tiedemann, Institute for Musculoskeletal Health, the University of Sydney School of Medicine, Sydney, NSW, Australia.

Scott Teasdale, Discipline of Psychiatry and Mental Health, School of Clinical Medicine, University of New South Wales, Sydney, NSW, Australia; Mindgardens Neuroscience Network, Sydney, NSW, Australia.

Catherine Sherrington, Institute for Musculoskeletal Health, the University of Sydney School of Medicine, Sydney, NSW, Australia.

Meghan Ambrens, Falls, Balance and Injury Research Centre, Neuroscience Research Australia, UNSW Sydney, Sydney, NSW, Australia; School of Population Health, UNSW Sydney, Sydney, NSW, Australia.

Gülşah Kurt, School of Psychology, University of New South Wales, Sydney, NSW, Australia.

Grace McKeon, Discipline of Psychiatry and Mental Health, School of Clinical Medicine, University of New South Wales, Sydney, NSW, Australia.

Declaration of Conflicts of Interest:

The authors declare that Prof Kim Delbaere is a Senior Editor at Age and Ageing. C.M. is supported by the UNSW Research Training Program (RTP) Scholarship. K.D., S.R. and C.S. are supported by the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC). A.T. is supported by a University of Sydney Robinson fellowship.

Declaration of Sources of Funding:

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- 1. World Health Organization . Mental Health of Older Adults. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-health-of-older-adults (15 April 2024, date last accessed).

- 2. Prince MJ, Wu F, Guo Y et al. The burden of disease in older people and implications for health policy and practice. Lancet 2015;385:549–62. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61347-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cai H, Jin Y, Liu R et al. Global prevalence of depression in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis of epidemiological surveys. Asian J Psychiatr 2023;80:103417. 10.1016/j.ajp.2022.103417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Curran E, Rosato M, Ferry F et al. Prevalence and factors associated with anxiety and depression in older adults: gender differences in psychosocial indicators. J Affect Disord 2020;267:114–22. 10.1016/j.jad.2020.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fiske A, Wetherell JL, Gatz M. Depression in older adults. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 2009;5:363–89. 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.032408.153621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. James S, Lucchesi L, Bisignano C et al. The global burden of falls: global, regional and national estimates of morbidity and mortality from the Global Burden of Disease study 2017. Inj Prev 2020;26:i3–11. 10.1136/injuryprev-2019-043286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. van der Meulen E, Zijlstra GR, Ambergen T et al. Effect of fall-related concerns on physical, mental, and social function in community-dwelling older adults: a prospective cohort study. J Am Geriatr Soc 2014;62:2333–8. 10.1111/jgs.13083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lee SL, Pearce E, Ajnakina O et al. The association between loneliness and depressive symptoms among adults aged 50 years and older: a 12-year population-based cohort study. Lancet Psychiatry 2021;8:48–57. 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30383-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kvelde T, Lord SR, Close JC et al. Depressive symptoms increase fall risk in older people, independent of antidepressant use, and reduced executive and physical functioning. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2015;60:190–5. 10.1016/j.archger.2014.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Barbagelata M, Morganti W, Seminerio E et al. Resilience improvement through a multicomponent physical and cognitive intervention for older people: the DanzArTe emotional well-being technology project. Aging Clin Exp Res 2024;36:72. 10.1007/s40520-023-02678-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Vancampfort D, Hallgren M, Firth J et al. Physical activity and suicidal ideation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord 2018;225:438–48. 10.1016/j.jad.2017.08.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Schuch FB, Vancampfort D, Rosenbaum S et al. Exercise for depression in older adults: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials adjusting for publication bias. Braz J Psychiatry 2016;38:247–54. 10.1590/1516-4446-2016-1915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Vella SA, Aidman E, Teychenne M et al. Optimising the effects of physical activity on mental health and wellbeing: a joint consensus statement from Sports Medicine Australia and the Australian Psychological Society. J Sci Med Sport 2023;26:132–9. 10.1016/j.jsams.2023.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Delbaere K, Valenzuela T, Lord S et al. E-health StandingTall balance exercise for fall prevention in older people: results of a two year randomised controlled trial. Br Med J 2021;373:n740. 10.1136/bmj.n740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Taylor ME, Ambrens M, Hawley-Hague H et al. Implementation of a digital exercise programme in health services to prevent falls in older people. Age Ageing 2024;53:afae173. 10.1093/ageing/afae173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Firth J, Marx W, Dash S et al. The effects of dietary improvement on symptoms of depression and anxiety: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Psychosom Med 2019;81:265–80. 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Forsman AK, Nordmyr J, Matosevic T et al. Promoting mental wellbeing among older people: technology-based interventions. Health Promot Int 2018;33:1042–54. 10.1093/heapro/dax047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. McKeon G, Papadopoulos E, Firth J et al. Social media interventions targeting exercise and diet behaviours in people with noncommunicable diseases (NCDs): a systematic review. Internet Interv 2022;27:100497. 10.1016/j.invent.2022.100497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. McKeon G, Tiedemann A, Sherrington C et al. Feasibility of an online, mental health-informed lifestyle program for people aged 60+ years during the COVID-19 pandemic. Health Promot J Austr 2021;33:545–52. 10.1002/hpja.538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mastrogiovanni C, Rosenbaum S, Delbaere K et al. A mental health-informed, online health promotion programme targeting physical activity and healthy eating for adults aged 60+ years: study protocol for the MovingTogether randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2022;23:1052–14. 10.1186/s13063-022-06978-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Greenwood JL, Joy EA, Stanford JB. The Physical Activity Vital Sign: a primary care tool to guide counseling for obesity. J Phys ActHealth 2010;7:571–6. 10.1123/jpah.7.5.571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. American College of Sports Medicine. In: ACSM’s Health-Related Physical Fitness Assessment Manual 5th Edition, 2017. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States: Wolters Kluwer. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Exercise Sports Science Australia (ESSA) . Adult Pre-Exercise Screening System (APSS) Screening Tool V2. https://www.essa.org.au/Public/ABOUT_ESSA/Pre-Exercise_Screening_Systems.aspx (25 March 2024, date last accessed).

- 24. Molnar FJ, Wells GA, McDowell I. The derivation and validation of the Ottawa 3D and Ottawa 3DY three-and four-question screens for cognitive impairment. Clin Med Insights Geriatr 2008;2:1–11. 10.4137/CMGer.S916. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kreidler SM, Muller KE, Grunwald GK et al. GLIMMPSE: online power computation for linear models with and without a baseline covariate. J Stat Softw 2013;54:i10. 10.18637/jss.v054.i10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Browne RH. On the use of a pilot sample for sample size determination. Stat Med 1995;14:1933–40. 10.1002/sim.4780141709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Michie S, Van Stralen MM, West R. The behaviour change wheel: a new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement Sci 2011;6:1–12. 10.1186/1748-5908-6-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. McKeon G, Steel Z, Wells R et al. Mental health informed physical activity for first responders and their support partner: a protocol for a stepped-wedge evaluation of an online, codesigned intervention. Br Med J Open 2019;9:e030668. 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-030668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sherrington C, Michaleff ZA, Fairhall N et al. Exercise to prevent falls in older adults: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med 2017;51:1750–8. 10.1136/bjsports-2016-096547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Cheema B, Robergs R, Askew C. Exercise physiologists emerge as allied healthcare professionals in the era of non-communicable disease pandemics: a report from Australia, 2006–2012. Sports Med 2014;44:869–77. 10.1007/s40279-014-0173-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.WHO guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020.

- 32. Kessler RC, Andrews G, Colpe LJ et al. Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychol Med 2002;32:959–76. 10.1017/S0033291702006074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Vasiliadis H-M, Chudzinski V, Gontijo-Guerra S et al. Screening instruments for a population of older adults: the 10-item Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K10) and the 7-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale (GAD-7). Psychiatry Res 2015;228:89–94. 10.1016/j.psychres.2015.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Delbaere K, Hauer K, Lord SR. Evaluation of the incidental and planned activity questionnaire (IPEQ) for older people. Br J Sports Med 2010;44:1029–34. 10.1136/bjsm.2009.060350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Annaliese McGavin. Brief social resources questionnaire [not published]. 2021.

- 36. Lubben J, Blozik E, Gillmann G et al. Performance of an abbreviated version of the Lubben Social Network Scale among three European community-dwelling older adult populations. Gerontologist 2006;46:503–13. 10.1093/geront/46.4.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wardian J, Robbins D, Wolfersteig W et al. Validation of the DSSI-10 to measure social support in a general population. Res Soc Work Pract 2013;23:100–6. 10.1177/1049731512464582. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Delbaere K, Smith ST, Lord SR. Development and initial validation of the Iconographical Falls Efficacy Scale. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2011;66A:674–80. 10.1093/gerona/glr019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Russell DW. UCLA Loneliness Scale (version 3): reliability, validity, and factor structure. J Pers Assess 1996;66:20–40. 10.1207/s15327752jpa6601_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Balestroni G, Bertolotti G. EuroQol-5D (EQ-5D): an instrument for measuring quality of life. Monaldi Arch Chest Dis 2012;78:155–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Feng Y-S, Kohlmann T, Janssen MF et al. Psychometric properties of the EQ-5D-5L: a systematic review of the literature. Qual Life Res 2021;30:647–73. 10.1007/s11136-020-02688-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Haley SM, Jette AM, Coster WJ et al. Late Life Function and Disability Instrument: II. Development and evaluation of the function component. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2002;57:M217–22. 10.1093/gerona/57.4.M217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Beauchamp MK, Schmidt CT, Pedersen MM et al. Psychometric properties of the Late-Life Function and Disability Instrument: a systematic review. Biomed Cent Geriatr 2014;14:12. 10.1186/1471-2318-14-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kendzierski D, DeCarlo KJ. Physical activity enjoyment scale: two validation studies. J Sport Exerc Psychol 1991;13:50–64. 10.1123/jsep.13.1.50. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Salim A, Mackinnon A, Christensen H et al. Comparison of data analysis strategies for intent-to-treat analysis in pre-test-post-test designs with substantial dropout rates. Psychiatry Res 2008;160:335–45. 10.1016/j.psychres.2007.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Hsieh H-F, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res 2005;15:1277–88. 10.1177/1049732305276687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Owusu-Addo E, Ofori-Asenso R, Batchelor F et al. Effective implementation approaches for healthy ageing interventions for older people: a rapid review. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2021;92:104263. 10.1016/j.archger.2020.104263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Bourke M, Wang HFW, McNaughton SA et al. Clusters of healthy lifestyle behaviours are associated with symptoms of depression, anxiety, and psychological distress: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Clin Psychol Rev 2025;118:102585. 10.1016/j.cpr.2025.102585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Beauchamp MR, Liu Y, Dunlop WL et al. Psychological mediators of exercise adherence among older adults in a group-based randomized trial. Health Psychol 2021;40:166–77. 10.1037/hea0001060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Roberts JS, Ferber RA, Funk CN et al. Mood Lifters for seniors: development and evaluation of an online, peer-led mental health program for older adults. Gerontol Geriatr Med 2022;8:23337214221117431. 10.1177/23337214221117431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Wilke J, Mohr L, Yuki G et al. Train at home, but not alone: a randomised controlled multicentre trial assessing the effects of live-streamed tele-exercise during COVID-19-related lockdowns. Br J Sports Med 2022;56:667–75. 10.1136/bjsports-2021-104994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Ferrucci L, Guralnik JM, Studenski S et al. Designing randomized, controlled trials aimed at preventing or delaying functional decline and disability in frail, older persons: a consensus report. J Am Geriatr Soc 2004;52:625–34. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52174.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.