Abstract

Rheumatic heart diseases (RHDs) impose a substantial global burden, primarily affecting individuals under 25 years of age in low- and medium-income countries (LMICs) and poor and marginalized groups in high-income countries.[1,2,3] The underlying cause is a group A beta-hemolytic streptococcus, which triggers an immune-mediated attack on the heart and joints. Although acute rheumatic fever (ARF) is treatable, its occurrence and complications remain high in impoverished areas.[4] Variations in social structure contribute to differences in the incidence and progression of the disease, even in affluent regions.[5] Administering anesthesia to this patient population presents significant challenges, particularly when early management has been inadequate due to limited medical care and follow-up. Literature shows evidence for anesthetic management of different types of RHDs, mostly focusing on mitral and aortic valvulopathies.[6,7] This review synthesizes literature from databases such as MEDLINE and PubMed searches from the year 2000 to date, focusing on anesthesia management strategies and the challenges posed by ARF and RHD. Specific topics covered include the diagnosis and management of ARF, acute complications, perioperative care for patients with RHD, and unique considerations for different valvular pathologiesWith this review, we aim to discuss the available evidence, current World Health Organization (WHO) and societal guidelines in the context of perioperative medical and anesthetic management, hemodynamic challenges, and postoperative courses. An emphasis on basic point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) training is made in this review as the current era of diagnostics and therapeutics is increasingly reliant on echocardiography.

Keywords: Acute rheumatic fever, anesthesia, aortic insufficiency, aortic stenosis, mitral regurgitation, mitral stenosis, pregnancy, rheumatic heart disease, tricuspid regurgitation, tricuspid stenosis

Introduction

Rheumatic heart disease (RHD) is an ailment of poverty and overcrowding. Despite effective treatment being available, it claims 300,000 lives per year globally.[5,8] A non-suppurative immune-mediated complication of group A beta-hemolytic streptococcal infection, rheumatic fever (RF), can present as acute severe carditis and valvular lesions or RHD where we see chronic valvular destruction after recurrent infective episodes. In low- and medium-income countries (LMICs), lack of primary care among the poor leads to the early progression of disease within 2–5 years of an initial episode of Streptococcal pharyngitis, whereas in high-income countries (HICs), the disease might take decades to progress. As a result, LMICs are primarily burdened with younger population with RHD while older patients are encountered in HICs.

In 2018, the World Health Organization (WHO) adopted resolution WHA 71.14, calling for a global response for RHD and RF, recognizing the extent and impact of the problem.[9] Anesthesiologists play a part in closing the gap by being part of patient care and assisting in managing these patients. Many management strategies for delivering safe anesthesia dwell upon understanding the disease and its sequelae. This especially holds for patients in LMICs where RHD might not be the disease presentation but rather a comorbidity complicating the surgical management of the primary pathology for which the patient presents to the hospital. Modifications in anesthetic techniques and incorporating invasive monitoring and imaging become vital tools for the anesthesiologist. AHA/ACC incorporated modified Jones criteria in 2015 to fit the current echocardiography era of diagnostics, further solidifying the importance of concomitant imaging in anesthesia care.[10] This calls for anesthesiologists to be not only familiar with the criteria but also gain expertise in echocardiography or seek help as suited for the same.

In this review, we aim to address the unique challenges posed by patients with rheumatic fever and RHD. We discuss specific issues of diagnosis and management of acute RF, its acute complications, and perioperative care of patients affected by this disease both in acute and chronic phases. Data search for this review was done with EMBASE and MEDLINE using words and combinations of anesthesia, acute rheumatic fever, rheumatic heart diseases, rheumatic valvular heart disease, mitral valve disease, aortic valve disease, and tricuspid valve disease.

Acute Rheumatic Fever

Acute rheumatic fever (ARF) usually presents within a month of group A beta-hemolytic streptococcal throat infection, although streptococcal skin infections have been noted to be responsible in tropical countries.[10,11,12] Molecular mimicry and, more recently, neoantigen theory are postulated as the mechanisms responsible for the immune-mediated affliction of the organ systems affected.[13,14] Clinical and diagnostic features of ARF and RHD are included in revised Jones criteria as major and minor manifestations of the disease and World Heart Federation echocardiographic criteria [Tables 1–3].[10,15] A classic description of the disease that “licks the joints, bites the heart, and nibbles the brain” still holds as cardiac complications are among the most serious ones.

Table 1.

Revised Jones criteria

| A. For all patient populations with evidence of preceding GAS infection | |

|---|---|

| Diagnosis: initial ARF | 2 major manifestations or 1 major plus 2 minor manifestations |

| Diagnosis: recurrent ARF | 2 Major or 1 major and 2 minor or 3 minor |

|

| |

| B. Major criteria | |

|

| |

| Low-risk populations | Moderate- and high-risk populations |

| Carditis | Carditis |

| • Clinical and/or subclinical | • Clinical and/or subclinical |

| Arthritis | Arthritis |

| • Polyarthritis only | • Monoarthritis or polyarthritisb • Polyarthralgia |

| Chorea | Chorea |

| Erythema marginatum | Erythema marginatum |

| Subcutaneous nodules | Subcutaneous nodules |

|

| |

| C. Minor criteria | |

|

| |

| Low-risk populations | Moderate- and high-risk populations |

| Polyarthralgia | Monoarthralgia |

| Fever (≥38.5°C) | Fever (≥38.5°C) |

| ESR ≥60 mm in the first hour and/or CRP ≥3.0 mg/dL | ESR ≥60 mm and/or CRP ≥3.0 mg/dL |

| Prolonged PR interval, after accounting for age variability (unless carditis is a major criterion) | Prolonged PR interval, after accounting for age variability (unless carditis is a major criterion) |

Evidence of preceding GAS infection is required for both populations. GAS: group A streptococcal infection; ARF: acute rheumatic fever; ESR: erythrocyte sedimentation rate; CRP: C-reactive protein. Low-risk populations are those with ARF incidence ≤2 per 100,000 school-aged children or all-age rheumatic heart disease prevalence of ≤1 per 1000 population-year. Subclinical carditis indicates echocardiographic valvulitis. Gewitz MH et al.; American Heart Association Committee on Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease of the Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young. Revision of the Jones Criteria for the diagnosis of acute rheumatic fever in the era of Doppler echocardiography: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2015 May 19;131(20):1806-18[10]

Table 3.

Morphological features of rheumatic heart disease

| Features seen in mitral valve |

| AML thickening ≥3 mm (age-specific) |

| Chordal thickening |

| Restricted leaflet motion |

| Excessive leaflet tip motion in systole |

| Features seen in aortic valve |

| Irregular/focal thickening |

| Coaptation defect |

| Restricted leaflet motion |

| Prolapse |

AML anterior mitral leaflet. Reményi B, Wilson N, Steer A, et al. World Heart Federation criteria for echocardiographic diagnosis of rheumatic heart disease--an evidence-based guideline. Nat Rev Cardiol 2012;9:297[15]

Cardiac complications, manifesting in 50%–80% of ARF cases, present as pancarditis and affect the pericardium, epicardium, myocardium, conduction system, and valves. Valvulitis, seen in 10% of cases, can present as acute valvular regurgitation lesions of the mitral and aortic valves and, less commonly, the tricuspid valve. Mitral annular and chordal inflammation, with subsequent annular dilatation and chordal elongation, are responsible for the pathogenesis of mitral valvular prolapse and regurgitation.[16] Rarely, chordal rupture occurs with acute severe mitral regurgitation (MR), requiring urgent mitral valve surgery. Although rare, severe MR with or without aortic insufficiency (AI) can lead to acute heart failure.[17] Myocarditis and pericarditis generally resolve without sequelae, but advanced degree of heart block can be occasionally seen.[18]

Acute inflammatory symptoms of ARF warrant avoidance of elective surgery during an acute episode. The use of steroids during the active inflammatory stage, although documented in the literature, has not been validated to be helpful in the control of the disease process. Urgent and emergent non-cardiac surgery should be undertaken with the consideration of the cardiac manifestations of the disease. Top anesthetic considerations are diagnosis per revised Jones criteria and anesthetic management of patients with complications. MR and subsequent presence or absence of heart failure symptoms, development of heart block, and the possibility of worsening of inflammatory response with surgical stress are significant concerns.

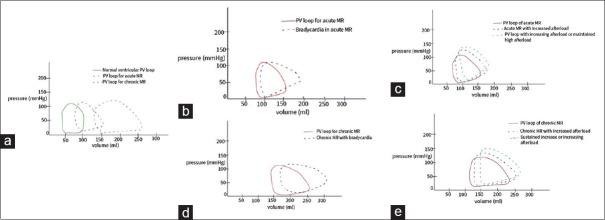

Anesthetic management is dependent on the surgical requirements and disease manifestations. MR in ARF is primary and acute, with a unique left ventricular pressure-volume relationship and response to changing variables such as afterload, diastolic time, rhythm, and contractility [Figure 1]. If signs of heart failure are absent, afterload reduction, heart rates of 85–95 bpm, and maintenance of sinus rhythm are the typical hemodynamic goals [Table 4], which can be attained with the help of low-dose nitroprusside or nitroglycerin infusions. An increase in systemic vascular resistance (SVR) and hypertension should be avoided. The benefits of neuraxial versus general anesthesia should be weighed against the surgical requirements and hemodynamic status of the patient. Medications lowering cardiac contractility are typically avoided; however, the severity of disease manifestations should be considered. Heart rate and blood pressure goals during the surgery can be obtained with ephedrine, atropine, glycopyrrolate, low-dose infusion of inotropes, and vasopressors such as dopamine, norepinephrine, and epinephrine. Intraoperative hemodynamic monitoring should be based on surgical and anesthetic requirements and cardiac functions. In patients with heart failure symptoms, invasive hemodynamic monitoring, in addition to standard American Society of Anesthesia (ASA) monitors, should be considered early on. Arterial blood pressure monitoring, urinary catheter, and central venous lines should be utilized as necessary by the anesthesiologist. The use of pulmonary artery (PA) catheters, although debatable, might have some utility in the intensive care unit (ICU) for inotrope and fluid management, depending on the severity of the cardiac and valvular dysfunction and the extent of surgery. Echocardiography should be decided on a case-by-case basis and by the expertise available. There should be a low threshold for alerting cardiology and cardiac surgery services if the patient needs advanced cardiac support services such as an intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP) or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) for severe heart failure with valvulopathy.

Figure 1.

(a) P-V loops in acute and chronic MR, (b) effect of bradycardia on P-V loop in acute MR (low LV compliance and volume), (c) effect of increased afterload on P-V loop in acute MR, (d) effect of bradycardia on P-V loop in chronic MR (increased LV volume and better compliance compared to acute MR), (e) effect of increased afterload on P-V loop in chronic MR. P-V pressure volume; MR mitral regurgitation; LV left ventricle

Table 4.

Hemodynamic goals for anesthetic management of valvular diseases associated with RHD

| Valvulopathy | Rhythm | HR | Preload | Afterload | LV Contractility | RV contractility | PVR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MS | Sinus (although Afib present in severe disease commonly) | 50–70 (Avoid HR <50) | Maintain (avoid hyper or hypovolemia) | Maintain | - | Maintain and support as needed | Maintain or lower |

| MR | Sinus | 80–100 | Maintain | Lower | Maintain and support as needed | - | - |

| AS | Sinus | 60–80 (Avoid tachycardia and severe bradycardia) | Adequate (Avoid hypovolemia) | Maintain | - | - | - |

| AI | - | 80–100 | Maintain | Lower | Maintain and support as needed | - | - |

| TR | Sinus | 90–100 (Avoid bradycardia in RV dysfunction) | Maintain (Avoid hyper or hypovolemia | Maintain and support perfusion pressures | Maintain | Maintain and support | Maintain or lower |

RHD, Rheumatic heart disease; HR, Heart rate; LV, left ventricle; RV, Right ventricle; PVR, pulmonary vascular resistance; MS, mitral stenosis; MR, Mitral regurgitation; AS, Aortic stenosis; AI, Aortic insufficiency; TR, Tricuspid regurgitation

Rheumatic Heart Disease

RHD develops as a sequela of one or recurrent episodes of ARF. In endemic regions of the world, the episodes of ARF can be frequently missed, leading to progressive valvulopathy presenting as advanced disease and complications such as heart failure, atrial fibrillation, pulmonary hypertension, and, less commonly, embolic stroke.[19,20] It is not unusual in these regions for a patient to present to the hospital for non-cardiac surgery with an established diagnosis of RHD or clinical suspicion of the same by the presence of a heart murmur. A high index of clinical suspicion should lead to imaging and diagnosis of the disease and complications before planning for elective surgery. In emergent situations, the patient should proceed to surgery with appropriate monitoring, including a bedside-focused cardiac examination. Although some form of mitral valve involvement is present in all RHDs, the aortic valve might be affected in 20%–30% of patients, followed by the tricuspid valve and rarely the pulmonic valve.

The REMEDY study demonstrated that in the current antibiotic era, earlier diagnosed lesions of both mitral and aortic valves are regurgitant lesions. Stenotic valvular lesions become the primary presentation in patients with an ARF history living in their 30s.[20,21] The following sections are dedicated to distinct valvulopathies.

Mitral Valvulopathy

The mitral valve is the most commonly affected in upwards of 50%–60% of cases of RHD, and rheumatic mitral stenosis (MS) is the most common cause of MS worldwide. RHD affects the mitral valve by causing valve stiffening, commissural fusion, and deformed, shortened, rigid, and calcified subvalvular apparatus. MR is more common in patients under 20 years of age in endemic regions, with MS dominating the picture in patients more than 30 years of age. Although pure MR can conceal underlying LV dysfunction and is generally well tolerated in younger patients, MS usually presents as the more severe lesion.

Typical echocardiographic findings in moderate-to-severe mitral valve stenosis are a fish mouth deformity secondary to commissural fusion and hockey stick deformity. The commissural fusion is one of the factors that makes balloon mitral valvulotomy (BMV) feasible as a form of conservative management for a stenotic mitral valve. This is unlike other etiopathologies of mitral stenosis. The echocardiographic criteria for diagnosing and grading disease severity are demonstrated in Tables 2, 3, and 5.[10,15,22] Long-term sequelae of MS start when the valve area decreases to less than 2.5 cm2. Due to the pressure differential caused by the stenotic and regurgitant valve, left atrial pressure chronically increases, leading to increased left atrial (LA) size and LA pressures, greater in MS than MR. Chronic back pressure and disease progression eventually lead to an increase in pulmonary artery pressures and eventual RV dysfunction. These features predispose the patient to be unable to handle increased fluid loads, decreases in systemic vascular resistance (SVR), and atrial arrhythmias such as atrial fibrillation (Afib), which can interfere with LA contribution in LV filling. It is likely to find these patients in chronic Afib and on chronic anticoagulant therapy due to their propensity to form clots. These changes are much more severe in MS, with the highest propensity to clot formation among valvular diseases.

Table 2.

Diagnostic criteria for rheumatic heart disease based on history, cardiac auscultation, and echocardiographic findings

| Column A | Column B | Column C | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Category of rheumatic heart disease | Presence or history of proven acute rheumatic fever AND/OR Finding on clinical cardiac auscultation (i.e., presence of pathological murmur of MR, MS, AI, and/or AS) AND/OR Echocardiographic structural and functional changes of MS without murmur (i.e., silent MS) | Echocardiographic valvular structural abnormality (i.e., typical rheumatic valve morphology according to the World Heart Federation criteria for echocardiographic diagnosis of rheumatic heart disease) | Echocardiographic functional abnormality (i.e., presence of significant valve regurgitation according to the World Heart Federation criteria for echocardiographic diagnosis of rheumatic heart disease |

| Definite (presence of at least two of the abnormalities described in columns A, B, and C) | + | + | + |

| Borderline (presence of abnormalities described in either column B or C) | - | + | + |

| Normal (none of the abnormalities described in columns A, B, and C) | - | - | - |

MR: mitral regurgitation; MS: mitral stenosis; AI: aortic insufficiency; AS: aortic stenosis. WHO Technical Report Series. Rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease: Report of a WHO expert panel, Geneva 29 October - 1 November 2001. Geneva: WHO; 2004. Remenyi B, Wilson N, Steer A, et al. World Heart Federation criteria for echocardiographic diagnosis of rheumatic heart disease - an evidence-based guideline. Nat Rev Cardiol 2012;9:297[15]

Table 5.

AHA/ACC guidelines for severity of valvular lesion in RHD

| Classification of Mitral Stenosis Severity | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Disease severity | Mild | Moderate | Severe |

| Valve area (cm2) | >2.5 | 2.5-1.5 | ≤1.5 |

| Pressure half-time (milliseconds) | <100 | 100-149 | ≥150 |

| Mean gradient (mmHg)# | <5 | 5-9 | ≥10 |

| Systolic pulmonary artery pressure | <30 | 30-49 | ≥50 |

| Classification of Mitral Regurgitation severity | |||

| Vena contracta (cm) | <0.3 | Intermediate | ≥0.7 |

| Pulmonary venous flow | Systolic dominance | Normal or systolic blunting | Minimal to no systolic flow/systolic flow reversal |

| Regurgitant volume (ml) | <30 | 30–59 | ≥60 |

| Regurgitation fraction | <30 | 30–49 | ≥50 |

| Classification of Aortic Stenosis Severity | |||

| Aortic valve area (cm2) | >1.5 | 1–1.5 | <1 |

| Mean pressure gradient (mmHg) | <20 | 20–40 | >40 |

| Classification of Aortic Regurgitation Severity | |||

| Pressure half time (millisecond) | >500 | 500–200 | <200 |

| Vena contracta (cm) | <0.3 | 0.3–0.6 | >0.6 |

| Jet width/LVOT width (%) | <25 | 25–64 | ≥65 |

| Regurgitant volume (ml) | <30 | 30–49 | ≥60 |

| Regurgitation fraction (%) | <30 | 30–49 | ≥50 |

| Classification of Tricuspid Regurgitation Severity | |||

| IVC diameter (cm) | <2 | 2.1–2.5 | >2.5 |

| Vena contracta (cm) | <0.3 | 0.3–0.69 | ≥0.7 |

| Hepatic venous flow | Systolic dominance | Systolic blunting | Systolic flow reversal |

| Regurgitant volume (ml) | <30 | 30–44 | ≥45 |

LVOT, Left ventricular outflow tract; IVC, Inferior vena cava. #At a heart rate of 60–80 beats per minute. Pandian NG et al. Recommendations for the Use of Echocardiography in the Evaluation of Rheumatic Heart Disease: A Report from the American Society of Echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2023 Jan; 36(1):3-28[22]

Anesthesia goals for non-cardiac surgery for these patients depend on the type and extent of surgical interventions, patient comorbidities, and severity of the disease. Proper grading and assessment of the severity of the disease is advised unless the surgery is urgent or emergent. In elective cases, preoperative assessment should include a detailed history, including surgical history and physical exam with symptom assessment and functional classification, including New York Heart Assessment (NYHA) grade. Blood tests such as an antistreptolysin O (ASO) titer and C-reactive protein (CRP), hepatic function tests in patients with symptoms of congestive hepatopathy, and coagulation studies for patients on anticoagulants are recommended, in addition to the routine laboratory tests, to rule out acute disease flare. In addition, medication history [Table 6], electrocardiogram (ECG), and valid echocardiography reports should be available to plan appropriately for anesthesia and surgery. Severe MS lesions benefit from BMV before elective surgery. In urgent surgeries, the use of POCUS to quickly assess the cardiac and valvular functions is suggested if the patient does not have the complete workup or the same is unavailable. If time permits, patients undergoing urgent or emergent surgeries with severe MS can also undergo BMV in a center with available services.

Table 6.

Typical medications used in valvulopathies

| Medications | MS | MR | AS | AI | TR | TS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-arrhthymics | Amiodarone Digoxin | Digoxin Amiodarone | Amiodarone Digoxin | Digoxin | Digoxin | Digoxin |

| CCBs | Diltiazem | Amlodipine Nifedipine | ||||

| Beta-blockers | Metoprolol tartarate Metoprolol succinate | Metoprolol tartarate Metoprolol succinate | ||||

| ACEIs ARBs | Lisinopril | Lisinopril | Lisinopril Losartan | Lisinopril | ||

| Nitrates | Nitroglycerine | |||||

| Diuretics | Furosemide | Furosemide | Furosemide | Furosemide | Furosemide | Furosemide |

| Torsemide | Torsemide | Torsemide | Torsemide | Torsemide | Torsemide | |

| Anticoagulants | Warfarin | Warfarin | Warfarin | Warfarin | Warfarin | Warfarin |

| DOACs | DOACs | DOACs | DOACs | DOACs | DOACs | |

| Enoxaparin | Enoxaparin | Enoxaparin | Enoxaparin | Enoxaparin | Enoxaparin | |

| Heparin | Heparin | Heparin | Heparin | Heparin | Heparin |

MS: mitral stenosis; MR: mitral regurgitation; AS: aortic stenosis; AI: aortic insufficiency; TR: tricuspid regurgitation; TS tricuspid stenosis; CCBs: calcium channel blockers; ACEIs: angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors; ARBs: angiotensin receptor blockers; DOACs: direct oral anticoagulants

Monitored anesthesia care (MAC), general or regional anesthesia, or a combination can be undertaken to provide adequate surgical conditions and postoperative analgesia. For patients on anticoagulants, guidelines formulated by ASRA, ESRA, and AAGBI can be used as references.[23,24,25]

A balanced anesthetic technique with the consideration of specific anesthetic agents on the sympathetic nervous system, SVR, myocardial depression, and maintenance of hemodynamic goals of significant lesions is advised. Table 7 summarizes the hemodynamic effects of commonly used anesthetic agents. Monitoring during the surgery depends on the anesthetic technique, type of surgery, and disease severity. Generally, standard ASA monitors for oxygenation, ventilation, circulation, and temperature are recommended for any non-cardiac surgery for RHD patients. Consideration for advanced hemodynamic monitoring such as invasive arterial blood pressure, urinary catheterization, central venous pressure, pulmonary artery pressure, and transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) monitoring should be given in patients with advanced disease, high NYHA grade, and reduced myocardial function. Antibiotic prophylaxis for the procedure depends on the surgery. The American Heart Association (AHA) does not recommend prophylaxis for endocarditis in patients with unrepaired rheumatic valve disease undergoing surgery [Table 8]. In patients with predominant MS, the hemodynamic goals for anesthesia management are maintenance of sinus rhythm and avoidance of rapid ventricular rates, avoidance of rapid reduction in SVR (systemic vascular resistance), and avoidance of sudden and marked increases in central blood volumes [Table 4]. Changes in these parameters and their effect on ventricular pressure-volume loops in MS are depicted in Figure 2. In patients with predominant MR, the hemodynamic goals are somewhat opposing to those for mitral stenosis, hence the importance of quantifying the disease, which is, more often than not, a mixed valvulopathy. In MR, slow heart rates and increases in SVR are avoided while maintaining cardiac contractility [Table 4]. The corresponding pressure-volume loops are depicted in Figure 1.

Table 7.

Hemodynamic effects of commonly used anesthetic agents

| Agent | MAP | HR | CI | SVR | PVR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Isoflurane | Decrease | Increase | - | Decrease | - |

| Sevoflurane | Decrease | - | Decrease | Decrease | - |

| Desflurane | Decrease | Increase | - | Decrease | - |

| Nitrous Oxide | - | - | - | - | Increase |

| Propofol | Decrease | - | Decrease | Decrease | - |

| Thiopentone | Decrease | Increase | -/Dose-dependent decrease | Decrease | - |

| Etomidate | -/Decrease | -/Decrease | - | - | - |

| Ketamine | Increase | Increase | Increase | Increase | Increase |

| Midazolam | -/Dose-dependent decrease | -/Increase | -/Dose-dependent decrease | -/Decrease | - |

| Fentanyl | -/Dose-dependent decrease | Dose-dependent bradycardia | -/Decrease | - | - |

| Hydromorphone | - | -/Dose-dependent bradycardia | - | - | - |

| Morphine | Decrease | Tachycardia*/Bradycardia (dose-dependent) | -/Decrease | Decrease | - |

| Succinylcholine | -/Decrease# | -/Bradycardia#/Tachycardia$ | - | - | - |

| Rocuronium | - | - | - | - | - |

| Vecuronium | - | - | - | - | - |

| Atracurium | -/Decrease* | -/Tachycardia* | - | -/Decrease | - |

| Pancuronium | Increase | Increase | Increase | Increase | - |

*Secondary to histamine release. #Parasympathetic nicotinic receptor stimulation. $Sympathetic ganglion if nicotine receptor stimulation

Table 8.

Recommendations for endocarditis prophylaxis

| Patients | Procedures | Antibiotic prophylaxis |

|---|---|---|

| • Prosthetic cardiac valve or valve repair with prosthetic valve material. • Durable mechanical circulatory support device (ventricular assist device or artificial heart). • Previous, relapsed, or recurrent IE • Certain types of congenital heart disease, including: ✓ Unrepaired cyanotic congenital heart disease (including patients with palliative shunts and conduits). ✓ Completely repaired congenital heart defect with prosthetic material or device, during the first six months after surgical or transcatheter placement. |

• Dental procedures that involve manipulation of the gingival tissue, manipulation of the periapical region of teeth, or perforation of the oral mucosa in patients with valvular heart • disease • Skin abscess drainage in patients at risk for IE • Antibiotic prophylaxis is not recommended for nondental procedures (e.g., TEE, • esophagogastroduodenoscopy, colonoscopy or cystoscopy) in the absence of active infection. • Routine antimicrobial prophylaxis for infective endocarditis is not recommended for most women (with or without heart disease) during pregnancy and delivery. |

• First line Amoxicillin 2 g (adult) or 50 mg/kg • For penicillin allergy Cephalexin 2 g (adult) or 50 mg/kg Or Azithromycin/clarithromycin 500 mg (adult) or 15 mg/kg Or Doxycycline 100 mg (adult), <45 kg (pediatric): 2.2 mg/kg, ≥45 kg: 100 mg |

|

✓ Repaired congenital heart disease with residual defect at the site or adjacent to the site of a prosthetic patch or prosthetic device. | ||

|

✓ Prosthetic pulmonary artery valve or conduit Cardiac transplant recipients who develop cardiac valvulopathy. |

IE, Infective endocarditis; TEE, transesophageal echocardiography. 2020 ACC/AHA Guideline for the Management of Patients With Valvular Heart Disease: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee. on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2021;143:e72-e227[35]

Figure 2.

(a) P-V loop in MS, (b) effect of tachycardia on P-V loop in MS, (c) effect of hypovolemia/reduced after load on P-V loop in MS. P-V pressure volume; MS mitral stenosis

Postoperative monitoring and recovery depend on surgical duration and invasiveness, the need for postoperative ventilation, and fluid resuscitation. Patients with severe MS and MR can benefit from recovery in the ICU. Control of pain in the postoperative period can be achieved with patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) pumps inclusive of systemic opioids and epidural infusions with similar hemodynamic goals as defined for pre and intraoperative periods. Care should be given to patients with elevated pulmonary artery pressures as severe acute increases in pulmonary artery pressures can occur with narcotics secondary to hypoventilation. Epidurals and regional nerve blocks might be especially beneficial in these patients. Early rehabilitation of these patients with physical therapy/occupational therapy (PT/OT) and follow-up with cardiology is recommended. Resumption of medical treatment, including cardiac medications and anticoagulants, should be done as early as possible and in conjunction with the surgical team as part of a multidisciplinary collaborative effort.

Aortic Valvulopathy

RHD is the most common cause of aortic valvular disease worldwide, with AI being more common than aortic stenosis (AS) or mixed disease. Although concomitant mitral valve involvement is present in most cases, up to 14% of patients can have pure AI, 9% pure AS, and 6% pure mixed aortic valve disease.[26] The pathophysiology of aortic valve disease is similar to mitral valve disease with irregular valve leaflet thickening and fibrosis, causing prolapse, coaptation defect, and restricted opening. In patients with predominant aortic stenosis, commissural fusion leading to reduced central aperture is seen.[15]

Echocardiographic features of the disease and diagnostic criteria are depicted in Tables 2, 3, and 5.[10,15,22] Aortic valve disease causes chronic pressure and volume overload-related changes in the LV, causing concentric and eccentric hypertrophic, respectively. AI can cause LV dilatation and concealed underlying LV dysfunction. LV dysfunction caused by AS is predominantly diastolic and increases as the valve lesion progresses. Symptoms of AI are progressive congestive heart failure (CHF) as the disease progresses. In contrast, AS can present as angina, syncope, and dyspnea, secondary to CHF, with progressively reduced life expectancy with each symptom. Both AS and AI can be asymptomatic in mild to moderate and occasionally severe disease. Pre-anesthesia evaluation in these patients must include verbal, physical, and drug history. Physical examination and laboratory workup are similar to rheumatic mitral valve disease. ASO titer, ESR, and CRP should evaluate acute disease flare. Elective surgery is suggested to be undertaken only when the patient does not have a flare. ECG and echocardiography are advised in all patients with documented or suspected disease. In urgent and emergent surgeries, a quick bedside cardiac echocardiogram can be done by the anesthesiologist in case a recent ECHO is unavailable.

Anesthesia can be MAC, general, regional, or a combination, depending on the surgical requirement, disease severity, and hemodynamic goals. When neuraxial techniques or deep peripheral nerve blocks are used, regional anesthesia societal guidelines are advised to be used.[23,24,25]

A balanced, procedure-centered anesthesia technique should be used. Monitoring should include standard ASA monitors with low thresholds for invasive monitoring such as a urinary catheter, arterial blood pressure monitoring, central venous cannulation including PA catheter and TEE based on the expertise of the anesthesia team, perioperative hemodynamic changes predicted, and postoperative ICU requirement. In severe AS, defibrillator pads are recommended to be applied preoperatively. The predominant lesion, AS or AI, dictates hemodynamic goals for the surgery. In AI, normal to increased heart rates of 80–100 bpm, normal to low preload and afterload, and maintained contractility are recommended [Table 4]. These goals can be achieved with balanced anesthesia technique, ephedrine or glycopyrrolate injection, fluid restriction, vasodilators such as nitroglycerin, and neuraxial anesthesia techniques. The effect of changes in hemodynamic parameters is depicted in Figure 3. In AS, slower heart rates of 60–80 bpm, maintenance of sinus rhythm, preload, afterload, and contractility are recommended [Table 4]. These goals can be achieved with beta-blockers, anti-arrhythmic therapy, judicious fluid administration, and vasoconstrictors such as phenylephrine and norepinephrine as needed. The effect of changes in hemodynamic parameters is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 3.

(a) P-V loops in acute and chronic AI, (b) effect of bradycardia on P-V loop in acute AI (low LV compliance and volume), (c) effect of increased afterload on P-V loop in acute AI, (d) effect of bradycardia on P-V loop in chronic AI (increased LV volume and better compliance compared to acute AI), (e) effect of increased afterload on P-V loop in chronic AI. P-V pressure volume; AI aortic insufficiency; LV left ventricle

Figure 4.

(a) P-V loop in AS, (b) effect of tachycardia on P-V loops in AS, (c) effect of increasing hypovolemia/reduced after load on P-V loops in AS. P-V pressure volume; AS aortic stenosis

Postoperative recovery, like in mitral valve disease, is determined by disease severity, surgery, invasive mechanical ventilation, and ICU requirements. Pain management can be achieved with multimodal analgesia, PCA pumps, and regional analgesia techniques. Care should be taken with patients on narcotics as pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) could be present in cases with diastolic dysfunction and increased LA pressures. Respiratory depression in these patients can lead to acute severe increases in PAH and right heart strain or failure. Recovery involves a multi-departmental effort with early involvement of rehabilitation services.

Tricuspid Valvulopathy

Less data is available for rheumatic tricuspid valve disease (RTVD) compared to mitral and aortic valve involvement; however, RTVD presents unique challenges concerning diagnosis and management. RTVD has a prevalence of 7.7%–9.7% among RHDs.[27,28] Within this subgroup, most lesions are tricuspid regurgitation (TR), with less than 3% of tricuspid disease attributed to tricuspid stenosis (TS). TS thus averages less than 0.5% of all rheumatic valvulopathies. Rheumatic pulmonary stenosis is rare, with an incidence of 0.03%.[28] While primary TR is caused by shortened and thickened tricuspid leaflets, secondary TR occurs in RHD from passive tricuspid annular dilation from PAH secondary to mitral disease. TS, a much less common complication, occurs secondary to commissural fusion and thickened tricuspid leaflets. However, pure TS without TR is very uncommon.

The absence of clinical signs makes diagnosis of right-sided valvulopathies difficult. In RHD, TR/TS are invariably associated with mitral and aortic valve diseases and PAH in most cases. Clinical manifestations can be seen as mild right heart dysfunction to right heart failure, hepatic dysfunction including ascites, renal dysfunction, and pericardial and pleural effusions. Pre-anesthetic evaluation of these patients should include a complete history and physical exam, routine lab work, ASO titer, CRP, liver and renal function tests, medication history, chest X-ray, ECG, and echocardiography. Patients with hepatic dysfunction can be coagulopathic, and coagulation tests are recommended. Although right heart catheterization is the definite test for delineating PAH, it can be deferred for the requirement of advanced therapy.[29]

Anesthesia is planned according to surgical needs, predicted hemodynamic changes, and predominant valvular and cardiopulmonary disease. MAC, general anesthesia, and regional anesthesia techniques can be used alone or in combination per the surgical requirements. In moderate-to-severe PAH and moderate-to-severe right heart dysfunction, laparoscopic techniques are not recommended as they have the potential to cause right heart failure by causing hypercarbia, reduced right heart preload, and increased afterload. For regional techniques, regional anesthesia societal guidelines can be used for reference.[23,24,25]

A balanced anesthesia technique is used with hemodynamic goals dictated by the surgical procedure and valvular disease. Perioperative anxiolytics and narcotics should be administered judiciously in patients with PAH due to the risk associated with hypercarbia and hypoxia causing right heart failure. Pre-induction invasive lines should be considered in patients with advanced disease undergoing high-risk surgery. Apart from standard ASA monitors, invasive blood pressure monitoring and dynamic measures of cardiac output such as stroke volume variability should be considered early. PA catheter can be inserted to guide therapy in PAH, although the risk of vascular injury in PAH should be weighed against the benefits of monitoring PAP. Echocardiography can be used per institutional practice and anesthesiologist’s preference and expertise. Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) and TEE are valuable tools for this purpose. Hemodynamic goals are guided mainly by the predominant valvular pathology, which in most cases is a primary left-sided pathology. The goal for right-sided pathology is to prevent exacerbations in PAH and right heart failure. This can be achieved by maintaining baseline RV preload and afterload by avoiding hypovolemia, hypoxia, hypercarbia, increased sympathetic tone, and lung hyperinflation. RV contractility can be maintained by preserving RV perfusion pressure with vasopressors such as norepinephrine and inotropes such as epinephrine, milrinone, and dobutamine. Selective pulmonary dilators such as epoprostenol and nitric oxide can be used to reduce right heart afterload.

Postoperative management of these patients is dictated by the hemodynamic changes from the procedure and anesthetic techniques, the requirement of ventilatory and vasopressor support, and ICU requirement for advanced monitoring and management. Multimodal pain management techniques should be used with cautious use of narcotics in patients with PAH and RV dysfunction. Pulmonary hypertension and heart failure meds should be restarted as soon as feasible, along with any preoperative anticoagulant medications. Early rehabilitation therapy should be the goal in all patients.

Mixed Disease

Manjunath et al.,[28] in their single-center study, including 13,289 patients, reported 3941 patients to have mixed valvular RHD. The combinations of valve disease in the order of most to least common were MS + MR (46.6%) > MS + AI (26.5%) > MR + AI (23.3%) > MS + AS (2.4%) > MR + AS (0.9%) >AS + AI (0.3%). Anesthetic management of mixed disease should be guided by the dominant or the more severe pathology. Fortunately, more severe combinations such as MS + AS and MR + AS are relatively uncommon. Early involvement of a multidisciplinary team to manage these patients is crucial to their survival and surgical success. Advanced hemodynamic monitoring is generally required to administer adequate pain relief and anesthesia. Postoperative care of these patients can be equally challenging, and early involvement of cardiac support services such as an extracorporeal life support team is advised in case of clinical deterioration.

RHD in Pregnancy

RHD in pregnancy is a significant cause of maternal mortality in the resource-poor regions of the world.[30] The majority of heart disease in women of childbearing age in these regions is rheumatic. Patients can have multiple presentations ranging from a documented mild, well-controlled disease to a patient with severe stenotic mitral valve disease presenting for the first time in labor.[31] Rheumatic MS, being the most common lesion during pregnancy, often presents for the first time during pregnancy due to the hyperdynamic state of pregnancy. It is also not uncommon to see pregnant patients with bioprosthetic and less commonly mechanical valves presenting to the anesthesia preoperative clinic. Thus, a combination of pregnancy with associated unique physiological changes and RHD poses multiple challenges in the anesthetic management of these patients.

Pregnancy-related physiological changes are increased cardiac output by 40%–50% of baseline, tachycardia, and increased circulating blood volume, which worsens during labor and postpartum due to autotransfusion from the uterus and lower extremities. These can exacerbate the transmitral gradient and LA pressure, resulting in pulmonary edema in a more than mildly stenotic mitral valve.[32] Although patients with rheumatic MR are generally able to tolerate the pregnancy, heart failure can be seen in moderate-to-severe MR.

Risk stratification of individual patients can be done using a modified WHO classification of maternal cardiovascular risk. In elective cases, the birth plan should be discussed with patients according to the risk.[33] Women planning a pregnancy or diagnosed early in pregnancy should be offered BMV pre-pregnancy and in the second trimester, respectively.[34] BMV can be done with minimal sedation and local anesthetic infiltration, making it safe during pregnancy. Urgent BMV can be undertaken in late pregnancy in patients with heart failure, although with increased risk and need for general anesthesia due to the requirement of mechanical ventilatory support. All women presenting with RHD in pregnancy should get a complete history and physical exam done. Exercise stress testing (EST) can be done to evaluate functional status, with the understanding that pregnant patients have higher resting heart rates and might have lower exercise capacity. Laboratory workup should include routing blood counts, metabolic panel, ASO titer, CRP, coagulation studies, ECG, and echocardiogram. Pregnant patients with bioprosthetic valves do not require anticoagulation, but occasionally, physicians encounter a pregnant patient with a mechanical valve. These patients are on warfarin, and as warfarin crosses the placenta and has teratogenic effects, the decision has to be made to either switch to unfractionated heparin (UFH) or low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) during pregnancy. AHA/ACC guidelines state that less than 5 mg/day of warfarin is safe during the first trimester, which is also the period of most reported valve thrombosis in patients switched to UFH or LMWH.[35] LMWH is preferred in the second and third trimesters.[35,36] It is, therefore, not unusual to see a pregnant patient with a mechanical valve present in the first trimester on warfarin therapy and the second and third trimesters on UFH/LMWH. The Regional Anesthesia Society’s and Society for Obstetric Anesthesia’s recommendations should be followed if regional anesthesia technique is planned in these patients.[23,24,25,36,37]

Labor epidural can be used in most patients with milder valvular disease. It provides an advantage in mild MS and MR by reducing SVR and thereby causing less overloading of pulmonary circulation from autotransfusion. Cesarean section (CS) itself has the disadvantage of causing sudden autotransfusion. In milder forms of the disease, epidurals can be used for CS with incremental dosing to avoid hypotension. Spinal anesthesia is not advisable in these patients, given the increased risk of hemodynamic collapse with a sudden reduction in preload and afterload and bradycardia seen in patients with high blocks. However, general anesthesia can be administered in patients with moderate-to-severe stenotic mitral valve disease. Apart from standard ASA monitors, advanced invasive monitoring, such as arterial line central venous access, including PA catheters to monitor PAH and TEE to guide therapy, can be used at the anesthesiologist’s discretion. Invasive lines are preferably established before induction. Anesthesia maintenance can be done with volatiles. A high-dose narcotic anesthesia with remifentanyl has been demonstrated by Weiner et al.[38] in an isolated case report. The neonatal ICU team should be alerted in advance of the need for resuscitation of these babies, especially if opioids were used for anesthesia before delivery. Nitrous oxide should be avoided in patients with PAH. Vasopressors and inotropes should be readily available in case of decompensation. In all instances, multidisciplinary involvement is required, and cardiac surgery support should be requested early if the need for ECMO is predicted. Getting access for ECMO before induction is feasible in most cases where support services are involved early.

Postpartum, these patients should be monitored for worsening CHF in the ICU for at least 24 hours as most of the decompensation happens during this time.[3] Cardiology and cardiac surgical services should continue to monitor these patients. Patients on preoperative anticoagulants should be restarted on the therapy as soon as feasible. These patients should also have post-discharge follow-up with cardiology in addition to their routine obstetric follow-up. Patients should discuss and plan for future pregnancy and contraception at that time.

Conclusion

This article highlights the significant challenges posed by ARF and RHD in anesthetic management, particularly in LMICs. The progression and complications of these conditions demand a comprehensive understanding and a tailored approach to anesthesia. Anesthesiologists play a critical role in the perioperative care of these patients, necessitating expertise in diagnosing, risk stratification, understanding hemodynamic implications, and managing the specific challenges associated with various forms of valvular diseases. The article underscores the need for global collaboration, adherence to guidelines, and application of a multidisciplinary approach to effectively manage and reduce the morbidity and mortality associated with RHD.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Funding Statement

Nil.

References

- 1.Kwan GF, Mayosi BM, Mocumbi AO, Miranda JJ, Ezzati M, Jain Y, et al. Endemic cardiovascular diseases of the poorest billion. Circulation. 2016;133:2561–75. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.008731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zilla P, Bolman RM, 3 rd, Boateng P, Sliwa K. A glimpse of hope: Cardiac surgery in low-and middle-income countries (LMICs) Cardiovasc Diagn Ther. 2020;10:336–49. doi: 10.21037/cdt.2019.11.03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tempe DK. Cardiac anesthesiologist and global capacity building to tackle rheumatic heart disease. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2021;35:1922–6. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2021.01.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Robertson KA, Volmink JA, Mayosi BM. Antibiotics for the primary prevention of acute rheumatic fever: A meta-analysis. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2005;5:11. doi: 10.1186/1471-2261-5-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Watkins DA, Johnson CO, Colquhoun SM, Karthikeyan G, Beaton A, Bukhman G, et al. Global, regional, and national burden of rheumatic heart disease, 1990-2015. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:713–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1603693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paul A, Das S. Valvular heart disease and anaesthesia. Indian J Anaesth. 2017;61:721–7. doi: 10.4103/ija.IJA_378_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kurup V, Haddadin AS. Valvular heart diseases. Anesthesiol Clin. 2006;24:487. doi: 10.1016/j.atc.2006.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carapetis JR, Steer AC, Mulholland EK, Weber M. The global burden of group A streptococcal diseases. Lancet Infect Dis. 2005;5:685–94. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(05)70267-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.WHO. Rheumatic Heart Disease. 2020. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/rheumatic-heart-disease .

- 10.Gewitz MH, Baltimore RS, Tani LY, Sable CA, Shulman ST, Carapetis J, et al. Revision of the Jones Criteria for the diagnosis of acute rheumatic fever in the era of Doppler echocardiography: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2015;131:1806–18. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000205. Erratum in: Circulation 2020 142 e65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ralph AP, Noonan S, Wade V, Currie BJ. The 2020 Australian guideline for prevention, diagnosis and management of acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease. Med J Aust. 2021 Mar;214(5):220–227. doi: 10.5694/mja2.50851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frost HR, Laho D, Sanderson-Smith ML, Licciardi P, Donath S, Curtis N, et al. Immune cross-opsonization within emm clusters following group a streptococcus skin infection: Broadening the scope of type-specific immunity. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;65:1523–31. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tandon R, Sharma M, Chandrashekhar Y, Kotb M, Yacoub MH, Narula J. Revisiting the pathogenesis of rheumatic fever and carditis. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2013;10:171–7. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2012.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dougherty S, Okello E, Mwangi J, Kumar RK. Rheumatic Heart Disease: JACC Focus Seminar 2/4. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2023;81:81–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2022.09.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reményi B, Wilson N, Steer A, Ferreira B, Kado J, Kumar K, et al. World Heart Federation criteria for echocardiographic diagnosis of rheumatic heart disease--an evidence-based guideline. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2012;9:297–309. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2012.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marcus RH, Sareli P, Pocock WA, Meyer TE, Magalhaes MP, Grieve T, et al. Functional anatomy of severe mitral regurgitation in active rheumatic carditis. Am J Cardiol. 1989;63:577–84. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(89)90902-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Essop MR, Nkomo VT. Rheumatic and nonrheumatic valvular heart disease: Epidemiology, management, and prevention in Africa. Circulation. 2005;112:3584–91. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.539775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rocha Araújo FD, Brandão KN, Araújo FA, Vasconcelos Severiano GM, Alves Meira ZM. Cardiac tamponade as a rare form of presentation of rheumatic carditis. Am Heart Hosp J. 2010;8:55–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Okello E, Ndagire E, Muhamed B, Sarnacki R, Murali M, Pulle J, et al. Incidence of acute rheumatic fever in northern and western Uganda: A prospective, population-based study. Lancet Glob Health. 2021;9:1423–30. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(21)00288-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zühlke L, Engel ME, Karthikeyan G, Rangarajan S, Mackie P, Cupido B, et al. Characteristics, complications, and gaps in evidence-based interventions in rheumatic heart disease: The Global Rheumatic Heart Disease Registry (the REMEDY study) Eur Heart J. 2015;36:1115–22a. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Feinstein AR, Wood HF, Spagnuolo M, Taranta A, Jonas S, Kleinberg E, et al. Rheumatic fever in children and adolescents. A long-term epidemiologic study of subsequent prophylaxis, streptococcal infections, and clinical sequelae. VII. Cardiac changes and sequelae. Ann Intern Med. 1964;60((Suppl 5)):87–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pandian NG, Kim JK, Arias-Godinez JA, Marx GR, Michelena HI, Chander Mohan J, et al. Recommendations for the use of echocardiography in the evaluation of rheumatic heart disease: A Report from the American Society of Echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2023;36:3–28. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2022.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Horlocker TT, Vandermeuelen E, Kopp SL, Gogarten W, Leffert LR, Benzon HT. Regional anesthesia in the patient receiving antithrombotic or thrombolytic therapy: American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine evidence-based guidelines (Fourth Edition) Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2018;43:263–309. doi: 10.1097/AAP.0000000000000763. Erratum in: Reg Anesth Pain Med 2018 43 566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kietaibl S, Ferrandis R, Godier A, Llau J, Lobo C, Macfarlane AJ, et al. Regional anaesthesia in patients on antithrombotic drugs: Joint ESAIC/ESRA guidelines. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2022;39:100–32. doi: 10.1097/EJA.0000000000001600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Working Party;Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain &Ireland;Obstetric Anaesthetists'Association;Regional Anaesthesia UK. Regional anaesthesia and patients with abnormalities of coagulation: The Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain &Ireland The Obstetric Anaesthetists'Association Regional Anaesthesia UK. Anaesthesia. 2013;68:966–72. doi: 10.1111/anae.12359. Erratum in: Anaesthesia 2016 71 352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Afifi A, Hosny H, Yacoub M. Rheumatic aortic valve disease-when and who to repair? Ann Cardiothorac Surg. 2019;8:383–9. doi: 10.21037/acs.2019.05.01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sultan FAT, Moustafa SE, Tajik J, Warsame T, Emani U, Alharthi M, et al. Rheumatic tricuspid valve disease: An evidence-based systematic overview. J Heart Valve Dis. 2010;19:374–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Manjunath CN, Srinivas P, Ravindranath KS, Dhanalakshmi C. Incidence and patterns of valvular heart disease in a tertiary care high-volume cardiac center: A single center experience. Indian Heart J. 2014;66:320–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ihj.2014.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pagnamenta A, Lador F, Azzola A, Beghetti M. Modern invasive hemodynamic assessment of pulmonary hypertension. Respiration. 2018;95:201–11. doi: 10.1159/000484942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Siu SC, Sermer M, Colman JM, Alvarez AN, Mercier LA, Morton BC, et al. Prospective multicenter study of pregnancy outcomes in women with heart disease. Circulation. 2001;104:515–21. doi: 10.1161/hc3001.093437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Haththotuwa HR, Attygalle D, Jayatilleka AC, Karunaratna V, Thorne SA. Maternal mortality due to cardiac disease in Sri Lanka. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2009;104:194–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2008.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Beaton A, Okello E, Scheel A, DeWyer A, Ssembatya R, Baaka O, et al. Impact of heart disease on maternal, fetal and neonatal outcomes in a low-resource setting. Heart. 2019;105:755–60. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2018-313810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Regitz-Zagrosek V, Roos-Hesselink JW, Bauersachs J, Blomström-Lundqvist C, Cífková R, De Bonis M, et al. 2018 ESC Guidelines for the management of cardiovascular diseases during pregnancy. Eur Heart J. 2018;39:3165–241. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sharma JB, Yadav V, Mishra S, Kriplani A, Bhatla N, Kachhawa G, et al. Comparative study on maternal and fetal outcome in pregnant women with rheumatic heart disease and severe mitral stenosis undergoing percutaneous balloon mitral valvotomy before or during pregnancy. Indian Heart J. 2018;70:685–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ihj.2018.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Otto CM, Nishimura RA, Bonow RO, et al. 2020 ACC/AHA Guideline for the Management of Patients With Valvular Heart Disease: Executive Summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2021 Feb 2;143(5):e35–e71. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Van Hagen IM, Roos-Hesselink JW, Ruys TP, Merz WM, Goland S, Gabriel H, et al. Pregnancy in women with a mechanical heart valve: Data of the European Society of Cardiology registry of pregnancy and cardiac disease (ROPAC) Circulation. 2015;132:132–42. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.015242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Leffert L, Butwick A, Carvalho B, Arendt K, Bates SM, Friedman A, et al. The Society for Obstetric Anesthesia and Perinatology consensus statement on the anesthetic management of pregnant and postpartum women receiving thromboprophylaxis or higher dose anticoagulants. Anesth Analg. 2018;126:928–44. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000002530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weiner MM, Vahl TP, Kahn RA. Case scenario: Cesarean section complicated by rheumatic mitral stenosis. Anesthesiology. 2011;114:949–57. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3182084b2b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]