Abstract

Objective

This study aimed to investigate factors influencing fatigue, its relationship with turnover or transfer intention (TTI), and its impact on the mental health of intensive care unit (ICU) nurses in rural Okinawa, Japan. In this region, career options are limited, and many female nurses struggle with balancing work and household responsibilities, potentially contributing to fatigue and mental health challenges.

Patients and Methods

A retrospective observational study was conducted with 28 ICU nurses from an acute care hospital in Okinawa. Fatigue and depressive symptoms were assessed using the Japanese Workers’ Accumulated Fatigue Self-Diagnosis Checklist and Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9). Participants were categorized according to fatigue levels (Low-High and Highest) and TTI status. Univariate analysis was used to examine the relationships between fatigue, TTI, and variables including gender, marital status, interpersonal issues, and nursing experience.

Results

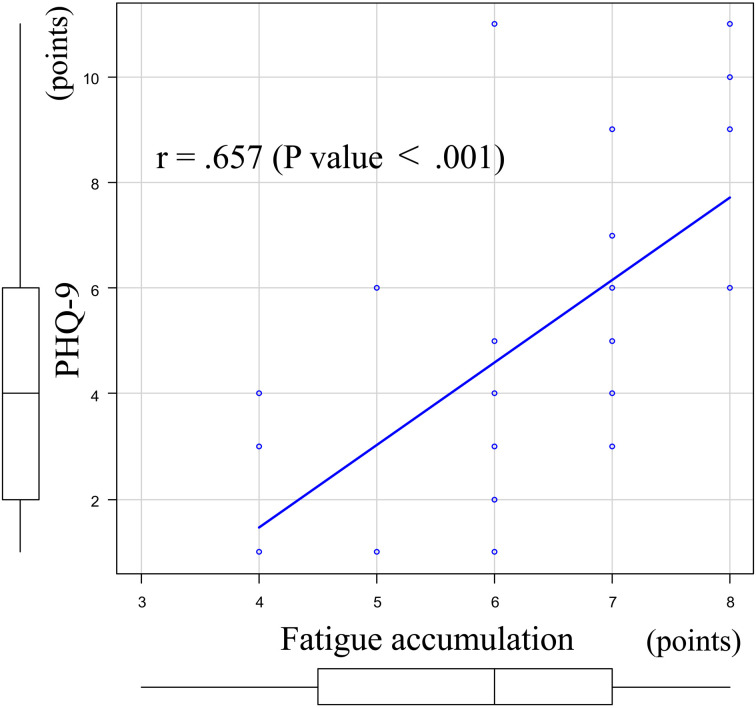

The Highest fatigue group accounted for 67.9% of the participants, and 42.9% were classified as having mild depression. The Highest fatigue group showed significantly higher PHQ-9 scores, longer nursing experience, and higher proportions of married nurses compared to the Low-High fatigue group (P<0.05). Fatigue and PHQ-9 scores were positively correlated (r=0.657, P<0.001). TTI was reported by 46.4% of participants, with significantly higher rates observed among female nurses experiencing interpersonal issues and those in the Highest fatigue group (P<0.05).

Conclusion

This study found a correlation between ICU nurses’ subjective fatigue and mental health, suggesting that severe fatigue, particularly due to interpersonal challenges, may be linked to TTI, highlighting the need for early interventions. However, no direct link was found between fatigue, depressive symptoms, and TTI. Further longitudinal research is required to clarify causality and enhance interventions. In rural areas such as Okinawa, where career options are limited, tailored interventions targeting fatigue and interpersonal challenges are essential.

Keywords: intensive care unit (ICU) nurses, subjective fatigue, depressive symptoms, turnover, work environment

Introduction

Nurse turnover is a critical issue, particularly in intensive care units (ICUs) where it affects patient care and the overall functionality of healthcare systems1, 2). ICU nurses face significant physical and psychological burdens that often lead to fatigue, depression, burnout, and reduced job satisfaction1). Fatigue exacerbates these challenges, making it difficult to retain nurses in ICUs3). As a result, turnover or transfer intentions (TTI) rates tend to rise.

Okinawa is a low-income region where dual-income households are common. The employment rate of mothers with children in Okinawa is remarkably high at 76%, having increased by approximately 20% over the past two decades4). At a study facility located in Okinawa, between 2021 and 2023, 26 ICU nurses left or transferred to other departments, representing 74.3% of the total ICU nursing positions. The majority of those who left were female, citing excessive workload and interpersonal issues as the main reasons. If such a negative workplace environment remains unaddressed, the high turnover and departmental transfer rates observed at this facility may represent only the tip of the iceberg, with potential TTI concealed beneath the surface. In rural areas, especially in regions like Okinawa, nurses face significant barriers when seeking career transitions. Unlike urban settings, where multiple healthcare facilities offer opportunities to align with career plans and work-life balance, rural areas provide limited options. In Okinawa Prefecture, only nine general hospitals are equipped with ICUs5), meaning that nurses who wish to work in an ICU must choose from these facilities. Typically, additional factors such as commuting distance, salary, and availability of childcare facilities or other benefits are also considered, further narrowing their options. This lack of alternatives often forces nurses to remain in their current positions despite their dissatisfaction. However, these labor conditions, which compel nurses to endure, may lead to burnout, mental health decline, or eventual turnover. Understanding these dynamics is essential for addressing TTI and developing effective retention strategies. In response, the study facility planned to introduce policies to improve nurse retention. Prior to implementation, questionnaire-based surveys and interviews were conducted to assess ICU conditions and challenges. Based on the results, measures such as reducing operational beds and increasing in-department education opportunities were implemented in clinical practice. However, these findings have not been statistically analyzed. This study aimed to retrospectively examine these results to identify nurses’ fatigue levels, the prevalence of depressive symptoms, factors influencing fatigue, and the prevalence and determinants of TTI, a precursor to turnover. Clarifying these factors will help identify the causes of fatigue, clarify the impact of fatigue on mental health and TTI, and provide insights for developing effective strategies to improve nurse retention.

Patients and Methods

Participants

This study included 28 ICU nurses from an acute care hospital in Okinawa, Japan. Surveys and interviews were conducted for all 35 ICU nursing staff members employed in the ICU as of November 2023. However, six nurses who did not complete all surveys conducted before and six months after policy implementation were excluded. Among the remaining 29 nurses, one ICU head nurse, who was not directly involved in patient care, was also excluded. Details of the study flow and eligibility criteria are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The study flow and eligibility criteria.

Study design

This retrospective single-center cohort study was conducted at an acute care hospital in Okinawa, Japan. As of December 2023, the hospital had 388 beds, including 12 ICU beds. This study involved the statistical analysis and interpretation of previously collected survey results, following approval from the ethics committee.

Data collection

Interview and questionnaire-based survey data were submitted to a clinical psychologist, who matched the individual data and created a correspondence table. To ensure anonymity, names were removed, and anonymized data were provided to the statistical analysis team.

1) Interview data

Each participant was interviewed once by the ICU nursing manager and once by a clinical psychologist before the implementation of hospital policies. The interviews primarily encouraged participants to freely express their thoughts, using the Depth Interview method6), specifically applied to inquiries about TTI. Standardized semi-structured questions, such as “Do you have any dissatisfaction with your workplace?” and “Does this make you consider leaving or transferring from your department?” were asked. If responses were ambiguous, TTI was recorded as “none”.

2) Questionnaire data

Participants anonymously completed the questionnaires, reflecting on their situation six months prior to policy implementation. Each questionnaire was assigned an identification number from the correspondence table. The survey included items on sex, age, years of nursing, ICU experience, marital status, and workplace dissatisfaction. Additional data on overtime hours were obtained from the hospital’s work management system. Fatigue and depressive symptoms were assessed using the Japanese versions of the Workers’ Accumulated Fatigue Self-Diagnosis Checklist7) and Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9)8). Fatigue scores ranged from 0 to 7, with scores of 4–7 classified as the highest fatigue. This fatigue score comprised two components: “subjective symptoms” (Category I: 0–2 points, Category II: 3–7 points, Category III: 8–14 points, Category IV: 15+ points) and “work conditions” (Category A: 0 points, Category B: 1–5 points, Category C: 6–11 points, Category D: 12+ points). Participants with a “subjective symptoms” score of ≥3 (Category II or above) underwent additional screening for depressive symptoms using the PHQ-9. A PHQ-9 score of ≥5 was defined as mild or greater depression, while a score of ≥10 was defined as moderate or greater depression.

Statistical analysis

Participants were classified into “Low-High fatigue group” (scores 0–3) and “Highest fatigue group” (scores 4–7) based on fatigue scores. Univariate analysis was used to compare the groups using Student’s t-test (or Welch’s test for unequal variances) for normally distributed continuous variables and the Mann–Whitney U test for non-normally distributed variables. Categorical variables were analyzed using Fisher’s exact test. Spearman’s rank correlation was used to assess the relationship between fatigue and PHQ-9 scores. Participants were also categorized into “TTI group” and “non-TTI group” based on the presence or absence of TTI. Additionally, three factors related to the rationale and objectives of the policy implementation—“gender”, “interpersonal issues”, and “individuals belonging to the Highest fatigue group”—were combined to create a new variable. This variable was used as an explanatory variable, while TTI served as the outcome variable, and a univariate analysis was performed. All statistical analyses were conducted using EZR, a graphical user interface for R (version 3.6.1; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria)9). All tests were two-sided, and a P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Overview of participants

Among the 28 participants surveyed, 64.3% were experienced hires, while 17.9% were new graduates. Individuals in their 30s accounted for 50.0% of the participants. The average nursing experience was 9.5 ± 5.5 years, and the median ICU experience was 4.5 [2.8–8.0] years. Of all participants, 89.3% had been expressing a desire for ICU placement. Workplace dissatisfaction included perceived nursing shortages relative to the number of patients (53.6%), dissatisfaction with salaries and promotions (10.7%), workload-related nursing shortages (82.1%), and interpersonal issues (46.4%). The median fatigue score was 6.0 [4.8–7.0]. The PHQ-9 was administered as a screening tool for depressive symptoms to 26 nurses (92.9%) whose “subjective symptoms” scores—a component of the fatigue score—were ≥3 (Category II or above). One nurse had missing data and was excluded from the analysis. Consequently, the PHQ-9 was administered to 25 nurses, yielding a median score of 4 [2–6]. The Highest fatigue group showed higher values for all the variables. Mild or greater depression was observed in 42.9% of all participants, while moderate or greater depression was observed in 10.7%. The results are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Results of univariate analysis: background factors influencing high fatigue accumulation.

| N | Low-High fatigue | Highest fatigue | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 28 (100) | 9 (32.1) | 19 (67.9) | ||

| Fatigue accumulation (points) | 6 [4.8–7.0] | 4 [4.0–4.0] | 7 [6.0–7.0] | <0.0001c |

| Self-reported symptom (category) | 3 [2.0–3.0] | 2 [2.0–2.0] | 3 [3.0–3.5] | <0.0001c |

| Work situation (points) | 3.1 ± 0.8 | 2.2 ± 0.4 | 3.5 ± 0.5 | <0.0001a |

| Gender (Male) | 7 (25.0) | 2 (22.2) | 5 (26.3) | >0.99d |

| Depression status (mild or higher) | 12 (42.9) | 1 (11.1) | 11 (57.9) | 0.16d |

| Moderate depression | 3 (10.7) | 0 (0) | 3 (15.8) | 0.55d |

| PHQ-9 (points) | 4 [2.0–6.0] | 2 [1.0–3.8] | 5 [3.0–8.0] | 0.047c |

| Years of experience | ||||

| Nurse experience (years) | 9.5 ± 5.5 | 6.1 ± 3.8 | 11.2 ± 5.5 | 0.02a |

| Less than 5 years of nursing experience | 7 (25.0) | 3 (33.3) | 4 (21.1) | 0.65d |

| Less than 10 years of nursing experience | 15 (53.6) | 7 (77.8) | 8 (42.1) | 0.11e |

| ICU experience (years) | 4.5 [2.8–8.0] | 3 [2.0–5.0] | 7 [3.0–8.0] | 0.15c |

| Less than 3 years of ICU experience | 7 (25.0) | 4 (44.4) | 3 (15.8) | 0.17d |

| Less than 5 years of ICU experience | 14 (50.0) | 3 (33.3) | 11 (57.9) | 0.42d |

| Desire for ICU placement | 25 (89.3) | 8 (88.9) | 17 (89.5) | >0.99d |

| Experienced recruitment | 18 (64.3) | 5 (55.6) | 13 (68.4) | 0.68d |

| New graduate recruitment | 5 (17.9) | 2 (22.2) | 3 (15.8) | >0.99d |

| Age | ||||

| Under 25 years old | 8 (28.6) | 5 (55.6) | 3 (15.8) | 0.07d |

| Under 30 years old | 8 (28.6) | 5 (55.6) | 3 (15.8) | 0.07d |

| Under 40 years old | 22 (78.6) | 9 (100) | 13 (68.4) | 0.14d |

| Aged between 30 and 39 | 14 (50.0) | 4 (44.4) | 10 (52.6) | >0.99d |

| Dissatisfaction with the workplace environment | ||||

| Perceived nurse shortage relative to patient numbers | 15 (53.6) | 6 (66.7) | 9 (47.4) | 0.44d |

| Inability to take requested days off | 1 (3.6) | 0 (0) | 1 (5.3) | >0.99d |

| Dissatisfaction with salary or promotions | 3 (10.7) | 2 (22.2) | 1 (5.3) | 0.23d |

| Absolute shortage of nurses relative to workload | 23 (82.1) | 7 (77.8) | 16 (84.2) | >0.99d |

| Presence of interpersonal issues | 13 (46.4) | 3 (33.3) | 10 (52.6) | 0.44d |

| Supervisors’ interpersonal issues | 8 (28.6) | 2 (66.7) | 6 (60.0) | >0.99d |

| Colleagues’ interpersonal issues | 7 (25.0) | 1 (11.1) | 6 (31.5) | 0.56d |

| Other professionals’ interpersonal issues | 1 (3.6) | 1 (11.1) | 0 (0) | 0.23d |

| Overtime hours (hours) | 7 [5.0–14.0] | 8 [6.0–14.0] | 7 [4.5–15.0] | 0.66c |

| Married | 11 (39.3) | 1 (11.1) | 10 (52.6) | 0.049d |

| Turnover or transfer to other department intentions | 13 (46.4) | 3 (33.3) | 10 (52.6) | 0.44d |

Fatigue accumulation was evaluated with a checklist developed by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Fatigue was categorized as follows: 0–1 (low), 2–3 (moderately high), 4–5 (high), and 6–7 (very high). Participants were divided into two groups based on their fatigue accumulation scores: the “Low-High fatigue group” (scores of 0–5) and the “Highest fatigue group” (scores of 6–7).

The PHQ-9 scores were divided into five levels: 0–4 was minimal, 5–9 was mild, 10–14 was moderate, 15–19 was moderately severe, and 20–27 was severe.

Continuous variables are presented as mean ± standard deviation or median (interquartile range); categorical variables are presented as numeric values (%).

aStudent’s t-test, bWelch T test, cMann–Whitney U test, dFisher’s exact test.

PHQ-9: Patient Health Questionnaire-9; ICU: Intensive care unit.

Fatigue and depression: univariate and bivariate analyses

Univariate analysis compared the Low-High fatigue group (32.1%) and the Highest fatigue group (67.9%), categorized based on fatigue levels. Significant differences were found in PHQ-9 scores (2 [1.0–3.8] vs. 5 [3.0–8.0], P<0.05), nursing experience (6.1 ± 3.8 vs. 11.2 ± 5.5 years, P<0.05), and marital status (11.1% vs. 52.6%, P<0.05). Mild or greater depression (11.7% vs. 57.9%) and moderate or greater depression (0% vs. 15.8%) were both higher in the Highest fatigue group, although these differences were not statistically significant. The results are presented in Table 1.

Bivariate analysis revealed a positive correlation between fatigue and PHQ-9 scores (r=0.657, P<0.001). The results are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The correlation between fatigue accumulation and PHQ-9.

Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient was used for statistical analysis.

A total of seven data points overlapped across three locations: two for (6,5), three for (6,2), and two for (4,1) in terms of fatigue accumulation and PHQ-9 scores. Consequently, the figure appears to show 21 data points instead of the actual 25, which is four times fewer than the true count.

PHQ-9: Patient Health Questionnaire-9.

Associated factors of TTI: univariate analysis

The TTI group accounted for 46.4% of participants, whereas the non-TTI group accounted for 53.6%. Univariate analysis revealed no significant differences in any variables. However, among the preselected variables—gender, interpersonal issues, and Highest fatigue group—the TTI group showed a non-significantly lower proportion of males and non-significantly higher levels for the other two variables compared to the non-TTI group. The results are presented in Table 2.

Table 2. Results of background factors influencing nurse turnover or transfer to other departments intentions: univariate analysis.

| N | Turnover or transfer to other departments | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non intention group (non-TTI) | Intention group (TTI) | |||

| 28 (100) | 15 (53.6) | 13 (46.4) | ||

| Fatigue accumulation (points) | 6 [4.8–7.0] | 6 [4.0–6.5] | 6 [6.0–7.0] | 0.22c |

| Highest fatigue group (6–7 points) | 19 (67.9) | 9 (60.0) | 10 (76.9) | 0.44d |

| Self-reported symptom (category) | 3 [2.0–3.0] | 3 [2.0–3.0] | 3 [3.0–4.0] | 0.12c |

| Work situation (points) | 3 [2.8–4.0] | 3 [2.0–4.0] | 3 [3.0–4.0] | 0.48c |

| Gender (Male) | 7 (25.0) | 6 (40.0) | 1 (7.7) | 0.08d |

| Depression status (mild or higher) | 12 (42.9) | 5 (33.3) | 7 (53.8) | 0.44d |

| Moderate depression | 3 (10.7) | 2 (13.3) | 1 (7.7) | >0.99d |

| PHQ-9 (points) | 4.0 [2.0–6.0] | 4.0 [2.0–5.0] | 5.5 [2.8–6.3] | 0.68c |

| Years of experience | ||||

| Nurse experience (years) | 9.5 ± 5.5 | 9.3 ± 6.1 | 9.8 ± 5.0 | 0.84a |

| Less than 5 years of nursing experience | 7 (25.0) | 4 (26.7) | 3 (23.1) | >0.99d |

| Less than 10 years of nursing experience | 15 (53.6) | 8 (53.3) | 7 (53.8) | >0.99d |

| ICU experience (years) | 4.5 [2.8–8] | 4.0 [1.5–7.5] | 5.0 [3.0–8.0] | 0.12c |

| Less than 3 years of ICU experience | 7 (25.0) | 6 (40.0) | 1 (7.7) | 0.08d |

| Less than 5 years of ICU experience | 14 (50.0) | 9 (60.0) | 5 (38.5) | 0.45d |

| Desire for ICU placement | 25 (89.3) | 13 (86.7) | 12 (92.3) | >0.99d |

| Experienced recruitment | 18 (64.3) | 10 (66.7) | 8 (61.5) | >0.99d |

| New graduate recruitment | 5 (17.9) | 3 (20.0) | 2 (15.4) | >0.99d |

| Age | ||||

| Under 25 years old | 8 (28.6) | 5 (33.3) | 3 (23.1) | 0.69d |

| Under 30 years old | 8 (28.6) | 5 (33.3) | 3 (23.1) | 0.69d |

| Under 40 years old | 22 (78.6) | 10 (66.7) | 12 (92.3) | 0.17d |

| Aged between 30 and 39 | 14 (50.0) | 5 (33.3) | 9 (69.2) | 0.13d |

| Dissatisfaction with the workplace environment | ||||

| Perceived nurse shortage relative to patient numbers | 15 (53.6) | 6 (40.0) | 9 (69.2) | 0.15d |

| Inability to take requested days off | 1 (3.6) | 0 (0) | 1 (7.7) | 0.46d |

| Dissatisfaction with salary or promotions | 3 (10.7) | 2 (13.3) | 1 (7.7) | >0.99d |

| Absolute shortage of nurses relative to workload | 23 (82.1) | 11 (73.3) | 12 (92.3) | 0.33d |

| Presence of interpersonal Issues | 13 (46.4) | 4 (26.7) | 9 (69.2) | 0.055d |

| Supervisors’ interpersonal issues | 8 (28.6) | 1 (6.7) | 7 (53.8) | 0.22d |

| Colleagues’ interpersonal issues | 7 (25) | 3 (20) | 4 (30.8) | 0.56d |

| Other professionals’ interpersonal issues | 1 (3.6) | 0 (0) | 1 (7.7) | >0.99d |

| Overtime hours (hours) | 7 [5–14] | 8 [6–14] | 7 [4–8] | 0.53c |

| Married | 11 (39.3) | 7 (46.7) | 4 (30.8) | 0.46d |

Fatigue accumulation was evaluated with a checklist developed by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Fatigue was categorized as follows: 0–1 (low), 2–3 (moderately high), 4–5 (high), and 6–7 (very high). Participants were divided into two groups based on their fatigue accumulation scores: the “Low-High fatigue group” (scores of 0–5) and the “Highest fatigue group” (scores of 6–7).

The PHQ-9 scores were divided into five levels: 0–4 was minimal, 5–9 was mild, 10–14 was moderate, 15–19 was moderately severe, and 20–27 was severe.

Continuous variables are presented as mean ± standard deviation or median (interquartile range); categorical variables are presented as numeric values (%).

aStudent’s t-test, bWelch T test, cMann–Whitney U test, dFisher’s exact test.

PHQ-9: Patient Health Questionnaire-9; ICU: Intensive care unit; TTI: Turnover or transfer to other departments intentions.

TTI and its combined related factors: a univariate analysis

A univariate analysis combining “Highest fatigue group”, “female gender”, and “interpersonal issues” revealed significantly higher TTI rates in female nurses with interpersonal issues and Highest-fatigue nurses with interpersonal issues (P<0.05). The results are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3. Group Comparison of Turnover or Transfer Intentions Among Variable Combinations: Univariate Analysis.

| N | Turnover or transfer to other departments | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non intention group (Non TTI) | Intention group (TTI) | |||

| 28 (100) | 15 (53.6) | 13 (46.4) | ||

| Female + Relationship issues | 12 (42.9) | 3 (20.0) | 9 (69.2) | 0.02d |

| Female + Highest fatigue group | 5 (17.9) | 4 (26.7) | 1 (7.7) | 0.33d |

| Highest fatigue group + Relationship issues | 9 (32.1) | 2 (13.3) | 7 (53.8) | 0.04d |

Fatigue accumulation was evaluated with a checklist developed by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Fatigue was categorized as follows: 0–1 (low), 2–3 (moderately high), 4–5 (high), and 6–7 (very high). Participants were divided into two groups based on their fatigue accumulation scores: the “Low-High fatigue group” (scores of 0–5) and the “Highest fatigue group” (scores of 6–7).

Categorical variables are presented as numeric values (%).

dFisher’s exact test.

TTI: Turnover or transfer to other departments intentions.

Discussion

This study investigated the factors influencing fatigue, its correlation with PHQ-9 scores, and the factors associated with TTI among ICU nurses. Studies focusing specifically on fatigue among ICU nurses are limited, and research targeting rural areas such as Okinawa is scarce. Moreover, studies examining the correlation between fatigue and depressive symptoms have been conducted, and many countries have developed evaluation tools for both fatigue and depression, including those translated into native languages and validated for reliability. However, few studies have assessed the correlation between fatigue and depressive symptoms using country-specific tools developed and validated for both conditions. This study aims to address this gap and provide new insights.

Factors influencing fatigue

Our study revealed that nursing experience and marital status were significantly higher in the Highest fatigue group. Similarly, previous research reported that nurses with more years of experience tend to have higher levels of subjective fatigue10). This finding suggests that experienced nurses, who often assume complex patient care and leadership responsibilities, may face increased stress and workload, contributing to elevated fatigue levels. Marital status was also significantly higher in the Highest fatigue group. Married nurses, particularly those with multiple children or heavy financial burdens, are likely to experience higher levels of work–family conflict, making it more challenging to balance professional and family responsibilities11). This is particularly relevant in Okinawa, where female nurses with children have remarkably high employment rate4). These results highlight the importance of targeted interventions to alleviate these stressors. However, some studies indicate a nonlinear relationship between nursing experience and fatigue12), while others report higher burnout rates among new graduate nurses compared to their more experienced counterparts13). These discrepancies may stem from unaccounted confounding factors such as differences in healthcare systems, local socioeconomic conditions, and institutional working environments.

Fatigue and depression correlation

Fatigue demonstrated a significant positive correlation with PHQ-9 scores (r=0.657), indicating that the demanding environment of the ICU may contribute to mental health challenges. This correlation, observed using the Japanese versions of the evaluation tools, aligns with findings from a previous study conducted on the general population in Norway using non-Japanese tools14). These results underscore the potential effect of fatigue on depressive symptoms among ICU nurses. Moreover, the consistency of this correlation with the Norwegian study suggests that the relationship is robust across diverse populations and cultural contexts. Furthermore, the use of Japanese tools highlights their reliability and applicability for evaluating these constructs.

Fatigue and TTI

The global average nurse turnover rate is 16%, with an average rate of 19% in the Asian region15). In contrast, the turnover rate among Japanese ICU nurses is lower, at 2.5% [1–5%]16). While the TTI observed in this study represents “intentions” rather than actual turnover, the findings indicate a substantial risk of nurse disengagement. Specifically, nearly half (46.4%) of the ICU nurses in this study exhibited TTI, suggesting that the previously reported high turnover rates may represent only the “tip of the iceberg”. In this study, nearly 70% of nurses were categorized as having the highest levels of fatigue, and over 40% were found to have mild or greater depressive symptoms. Although not statistically significant, nurses in the Highest fatigue group tended to have higher TTI rates than those in the Low-High fatigue group. These results suggest that fatigue and psychological burden significantly influence TTI. Notably, TTI was significantly higher among female nurses experiencing interpersonal conflict and nurses reporting high fatigue levels. Prior studies have identified high fatigue17) and interpersonal conflict18) as the key drivers of turnover. Additionally, women are particularly vulnerable to the negative impact of interpersonal difficulties19), are twice as likely to experience fatigue20), and exhibit significantly higher levels of personal burnout than their male counterparts21). Nurse managers should understand the factors underlying TTI and address them to reduce unnecessary turnovers and transfers. At both the departmental and organizational levels, creating a supportive and safe work environment is essential for addressing TTI, which is heavily influenced by interpersonal dynamics and managerial support22).

Despite high TTI rates, many nurses in this study continued to work, possibly reflecting the unique characteristics of Okinawa, a rural region with limited career mobility. However, sustaining employment while facing significant health-related challenges may not be feasible in the long term. Tailored interventions that consider regional characteristics and emphasize improving nurses’ health and workplace conditions are crucial for reducing TTI and enhancing nurse retention.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, as a retrospective study at a single ICU in Okinawa, generalization to other facilities or wards is limited. Fatigue and TTI are influenced by institutional and regional factors, including hospital size, employment type, and local management. Turnover rates vary, with smaller or private hospitals showing different dynamics than larger or public ones; however, these factors were not analyzed in this study. Second, interviewer-participant relationships and techniques may have influenced the results. Self-reported fatigue assessments could reflect over-statements due to self-congratulatory perceptions. Position bias between superiors and subordinates is also difficult to eliminate. However, the interviews were not conducted specifically for this study, and the interviewers were incoming ICU managers. Therefore, the limited interaction between interviewers and nurses likely reduced the potential for intentional bias or closeness effects. In clinical practice, interviews with superiors are common, making full removal of position bias unrealistic. Third, TTI can indicate positive career steps, such as intra-facility transfers for growth; however, this aspect is beyond the scope of this study. Finally, it should be noted that this study did not consider the temporal link between fatigue and depressive symptoms, necessitating cautious interpretation of causality. Given the cross-sectional design, it remains unclear whether fatigue induces depression or vice versa. Moreover, the association with TTI should be viewed as limited, requiring cautious interpretation.

Strengths

This study presented a reproducible methodology that combines routine managerial interviews with locally available tools for assessing fatigue and depression applicable to any healthcare facility. This methodology enabled the quantitative evaluation of high-fatigue states that contribute to nurse retention risks and health challenges, providing a practical framework for the early identification of affected nurses. The sample size reflected the typical number of nurses in ICUs or similar units, ensuring relevance in real-world clinical settings. Furthermore, this approach facilitates timely and appropriate interventions, offering a meaningful strategy to improve workplace environments across diverse healthcare settings, particularly in rural areas with unique employment conditions such as Okinawa.

Conclusions

This study observed a correlation between ICU nurses’ subjective fatigue and mental health, suggesting that those experiencing significant fatigue, particularly interpersonal challenges, may be more inclined toward TTI. Additionally, it outlines an approach for identifying nurses’ fatigue and workplace stressors, indicating that early interventions may help support well-being. However, this study did not establish a direct link between fatigue, depressive symptoms, and TTI. Further longitudinal research is required to explore causality and refine intervention strategies. In rural areas, such as Okinawa, where career options are limited, tailored interventions targeting fatigue and interpersonal challenges are essential.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Funding information

No external funding was received for this study.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval to begin the study was obtained through an ethical review by the Clinical Ethics Committee of the Social Medical Corporation Yuuai Medical Center (approval number R06R007). Non-cooperation, lack of response, and invalid answers were considered non-consent. Participants could withdraw their consent at any time through an opt-out option available on the facility’s website.

Consent for publication

All authors consent to the publication of this article in Journal of Rural Medicine.

Author contributions

Conceptualization and Project administration: Toshiharu Nakama. Data curation: Shunta Tamashiro and Takahiro Kinjo. Formal analysis: Mitsunobu Toyosaki. Writing, review, and editing: Toshiharu Nakama and Koji Senaha. Supervisor: Mitsunobu Toyosaki.

Acknowledgments

We deeply appreciate all the participants for their valuable contributions to this study.

Data availability statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- 1.Drennan VM, Ross F. Global nurse shortages-the facts, the impact and action for change. Br Med Bull 2019; 130: 25–37. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldz014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Myhren H, Ekeberg O, Stokland O. Job satisfaction and burnout among intensive care unit nurses and physicians. Crit Care Res Pract 2013; 2013: 786176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sun T, Huang XH, Zhang SE, et al. Fatigue as a cause of professional dissatisfaction among Chinese nurses in intensive care units during the COVID-19 pandemic. Risk Manag Healthc Policy 2023; 16: 817–831. doi: 10.2147/RMHP.S391336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.The Japan Times. Japan’s record percentage of working mothers masks low-paying jobs. 2022. https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2022/09/10/business/japan-working-mothers-pay-gap/?utm_source=chatgpt.com (Accessed January 26, 2025).

- 5.The Japanese Society of Intensive Care Medicine. List of Accredited Specialist Training Facilities by Academic Society. 2025. https://www.jsicm.org/institution/index.html?pref=okinawa&utm_source=chatgpt.com (Accessed January 26, 2025)

- 6.Roller MR. The in-depth interview method [Working paper]. 2020. https://www.rollerresearch.com/MRR%20WORKING%20PAPERS/IDI%20April%202020-Final.pdf (Accessed January 26, 2025)

- 7.Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Worker Fatigue Accumulation Self-Diagnosis Checklist (2023 revised version). 2023. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/content/001084057.pdf (Accessed January 26, 2025)

- 8.Inagaki M, Ohtsuki T, Yonemoto N, et al. Validity of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ)-9 and PHQ-2 in general internal medicine primary care at a Japanese rural hospital: a cross-sectional study. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2013; 35: 592–597. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2013.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kanda Y. Investigation of the freely available easy-to-use software ‘EZR’ for medical statistics. Bone Marrow Transplant 2013; 48: 452–458. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2012.244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kagamiyama H, Yano R. Relationship between subjective fatigue, physical activity, and sleep indices in nurses working 16-hour night shifts in a rotating two-shift system. J Rural Med 2018; 13: 26–32. doi: 10.2185/jrm.2951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yao X, Wen S, Song Z, et al. Work-family conflict categories and support strategies for married female nurses: a latent profile analysis. Front Public Health 2024; 12: 1324147. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2024.1324147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liao T, Liu Y, Luo W, et al. Non-linear association of years of experience and burnout among nursing staff: a restricted cubic spline analysis. Front Public Health 2024; 12: 1343293. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2024.1343293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Al Sabei SD, Al-Rawajfah O, AbuAlRub R, et al. Nurses’ job burnout and its association with work environment, empowerment and psychological stress during COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Nurs Pract 2022; 28: e13077. doi: 10.1111/ijn.13077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dahl AA, Grotmol KS, Hjermstad MJ, et al. Norwegian reference data on the Fatigue Questionnaire and the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 and their interrelationship. Ann Gen Psychiatry 2020; 19: 60. doi: 10.1186/s12991-020-00311-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ren H, Li P, Xue Y, et al. Global prevalence of nurse turnover rates: a meta-analysis of 21 studies from 14 countries. J Nurs Manag 2024; 5063998:. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Japan Society of Intensive Care Medicine, Intensive Care Nursing Committee 2022 Critical Care Specialist Facility Survey: Additional Report. 2023. https://www.jsicm.org/publication/pdf/2022_20230808_JSICM_sksch_nrs.pdf.

- 17.Xu JB, Zheng QX, Jiang XM, et al. Mediating effects of social support, mental health between stress overload, fatigue and turnover intention among operating theatre nurses. BMC Nurs 2023; 22: 364. doi: 10.1186/s12912-023-01518-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yamaguchi S, Ogata Y, Sasaki M, et al. The impact of resilience and leader–member exchange on actual turnover: a prospective study of nurses in acute hospitals. Healthcare (Basel) 2025; 13: 111. doi: 10.3390/healthcare13020111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Deng Y, Chang L, Yang M, et al. Gender differences in emotional response: Inconsistency between experience and expressivity. PLoS One 2016; 11: e0158666. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0158666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sharpe M, Wilks D. Fatigue. BMJ 2002; 325: 480–483. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7362.480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alenezi L, Gillespie GL, Smith C, et al. Gender differences in burnout among US nurse leaders during COVID-19 pandemic: an online cross-sectional survey study. BMJ Open 2024; 14: e089885. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2024-089885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hellín Gil MF, Ruiz Hernández JA, Ibáñez-López FJ, et al. Relationship between job satisfaction and workload of nurses in adult inpatient units. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022; 19: 11701. doi: 10.3390/ijerph191811701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.