Abstract

Ion flux kinetics associated with blue light (BL) treatment of two wild types (WTs) and the phot1, phot2 and phot1/phot2 mutants of Arabidopsis were studied by using the MIFE noninvasive ion-selective microelectrode technique. BL induced significant changes in activity of H+ and Ca2+ transporters within the first 10 min of BL onset, peaking between 3 and 5 min. In all WT plants and in phot2 mutants, BL induced immediate Ca2+ influx. In phot1 and phot1/phot2 mutants, net Ca2+ flux remained steady. It is suggested that PHOT1 regulates Ca2+ uptake into the cytoplasm from the apoplast. Changes in ion fluxes were measured from cotyledons of intact seedlings and from the cut top of the hypocotyl of decapitated seedlings. Thus the photoreceptors mediating BL-induced Ca2+ and H+ fluxes are present in the rest of the decapitated seedling and probably in the cotyledons as well. The H+ and Ca2+ flux responses to BL appear not to be linked because, (i) when changes were observed for both ions, Ca2+ flux changed almost immediately, whereas H+ flux lagged by about 1.5 min; (ii) in the Wassilewskija ecotype, changes in H+ fluxes were small. Finally, wave-like changes in Ca2+ and H+ concentrations were observed along the cotyledon–hook axis regardless of its orientation to the light.

Blue light (BL) is a key factor controlling plant growth and morphogenesis. Among numerous physiological processes controlled by BL are phototropism (bending toward or away from the light source), cotyledon expansion, and inhibition of hypocotyl elongation (1–3). These reactions are preceded or accompanied by significant changes in electrochemical properties of cells and tissues, including changes in membrane potential and ion transport across membranes (4–6).

For more than 60 years, the interpretation of the multiphasic transient surface electrical responses of plants to light (7–11) was problematic and speculative (4). More recently, with microelectrode impalements, those responses have been located at the plasma membrane (12, 13), and it is now possible to interpret them in terms of specific ionic movements (5). BL induces transient extracellular acidification of epidermal cells of young pea leaves (14, 15). This acidification was found to be linked to Ca2+ entry and Ca2+-calmodulin binding (14). BL also induces opening of anion (16) and potassium (17) channels and changes in the [Ca2+]cyt (18) in plants and plant cells. Protoplasts isolated from Arabidopsis hypocotyl cells exhibited shrinkage after BL illumination, which is likely to be linked with Cl− and K+ efflux (19).

Unfortunately, there are pitfalls in inferring causal links between electrophysiological changes and BL-induced morphogenetic responses, based only on the similarity of the time scales of the measured responses. From their time scale, the photomorphogenetic reactions could be divided into several groups. The quickest observed (within minutes) are reactions associated with inhibition of hypocotyl elongation (11, 13). Next are bending responses, operating within the time scale of hours. The slowest are reactions of cotyledon expansion, which take days (2). However, it is quite possible that all these reactions may be induced simultaneously (moreover, they could be linked), and the observed difference originates merely from different rates and delays in metabolic or long-distance-transport processes that mediate BL responses at the whole-plant level. Thus, it is very difficult to link causally the electrophysiological changes measured in response to BL treatment with one of these physiological responses. Still there are some indications of Ca2+ involvement in the phototropic response: unilateral white light caused an increase in [Ca2+]cyt in the shaded side of maize coleoptiles (20).

Recent progress in molecular biology and the availability of several phototropic Arabidopsis mutants provide a unique opportunity to overcome most of these problems. Of special interest is a mutant, deficient in PHOT1 gene expression, which lacks bending toward unilateral BL at low light intensity (21–23). Another gene, named PHOT2, has been discovered with striking similarity (58% identity and 67% similarity) to PHOT1 (21), and recently it has been shown that PHOT1 and PHOT2 show partially overlapping functions in phototropism and chloroplast relocation (22). In this study, we made an electrophysiological assessment of WT plants and their phot1, phot2, and phot1/phot2 mutants.

Understanding the electrophysiological mechanisms underlying BL perception in plants is additionally complicated by some methodological difficulties. These are associated with the slowness of plant phototropic responses and the consequent requirement for long-term measurements in rapidly expanding and bending tissues. That problem severely limits application of impaled microelectrode techniques used for both MP and cytosolic ion concentration measurements. Maintenance of gigaohm seals in patch–clamp studies over several hours is also problematic, whereas long-term monitoring of cytosolic pH and Ca2+ concentrations by using dyes might be complicated by dye bleaching.

In the last decade, noninvasive ion-selective microelectrode ion flux measurements have become a useful tool in plant physiological research (24–26). The MIFE technique developed in our laboratory (26) has high temporal (10-s) and spatial (several micrometers) resolutions, which make it an ideal tool to study electrophysiological responses associated with BL perception in etiolated plant tissues. We applied this technique to study BL-induced kinetics of net H+ and Ca2+ flux near cotyledons and hypocotyls of Arabidopsis WT plants and phot1, phot2, and phot1/phot2 mutants. We report a significant difference in BL-induced Ca2+ flux responses and suggest that PHOT1 regulates Ca2+ uptake into the cytoplasm from the apoplast.

Materials and Methods

Plant Material and Growing Conditions.

Seeds of Arabidopsis thaliana WTs [ecotype Col-0 (Col) and Wassilewskija (WS); Lehle Seeds], mutant line phot1–5 (Col background; a kind gift of W. R. Briggs, Carnegie Institution of Washington) and phot2-1 mutant and double-mutant phot1/phot2 (WS background; a kind gift of T. Sakai, RIKEN Plant Science Centre, Kyoto) were planted in Petri dishes on 0.8% (wt/vol) agar made up in 200 μM KCl + 100 μM CaCl2 solution and placed in a refrigerator at 8°C for 3 days. Before germination in complete darkness at 22 ± 2°C for 72 h, seeds were exposed to white light for 24 h at 22°C. Seedlings were ready for measurements when their hypocotyls were 7–10 mm long. At that stage, a seedling was transferred (in upright position) onto the liquid agar drop (at 28 ± 1°C) placed on a glass slide. The slide was attached to the bottom of a measuring chamber by sections of silicone tubes. After the agar solidified, the chamber was filled with measuring solution (200 μM KCl + 100 μM CaCl2; unbuffered pH about 5.2). All handling procedures were performed by using “safe” red light of 2.4 μmol⋅m−2⋅s−1. The chamber was then placed in the Faraday cage under the microscope light (red plastic filter; 0.9 μmol⋅m−2⋅s−1). Measurements started 30–60 min later.

In some experiments, decapitated seedlings were used to overcome the blocking effect of hypocotyl cuticle on ion fluxes. Decapitation was made just below the hook by a razor blade. To minimize the effect of wounding on fluxes, measurements on decapitated plants started several hours after the cotyledons were removed (27).

In all experiments, the source of monochromatic BL (468 nm) was a QBEAM projector (Quantum Devices, Barneveld, WI). In most experiments, the standard treatment was 15 mmol m−2 given as a 10-min pulse of 25 μmol⋅ m−2⋅s−1 BL. Bending assay studies showed that this fluence was adequate to induce substantial phototropic bending within 2 h in WTs, whereas phot1 and phot1/phot2 mutants did not show such bending (our own observations and refs. 22 and 28).

Ion Flux Measurements.

Specific details of ion-selective microelectrode fabrication and calibration are given in our previous publications (25, 29). The theory of measurements using the MIFE system (University of Tasmania) has also been given in a recent review (24).

Three different types of experiments were conducted (Fig. 1). In some experiments, net ion fluxes were measured from the cotyledon region of intact etiolated seedlings (Fig. 1A). The H+ and Ca2+ microelectrodes were positioned near the selected region, 50 μm above the surface, with their tips separated by 2–3 μm. Net H+ and Ca2+ fluxes were measured for 20–30 min before BL treatment. Then the BL pulse was given and measurements continued for at least 30 min (up to 4 h in some cases). As the distance between plant tissue and electrode tips changed because of the process of hook opening [a phenomenon known to be caused by the background red light (30)], the electrode position was adjusted every 1–2 min by using the three-dimensional hydraulic manipulator.

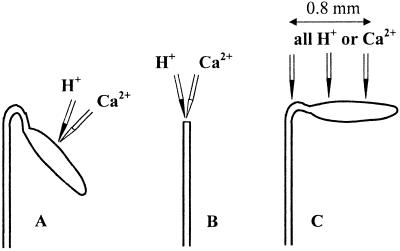

Figure 1.

Three types of experiments used in this study. (A) H+ and Ca2+ ion selective microelectrodes were located in either the hook or the cotyledon region. Net ion fluxes were measured as described in Materials and Methods. (B) Similar measurements carried out on decapitated seedlings. (C) Three identical electrodes (either H+ or Ca2+) were separated by about 0.4 mm along the seedling surface (open hook) to study apparent pH and Ca2+ waves in response to BL.

In the second type of experiment, electrodes were placed 50 μm from the cut surface of decapitated seedlings (Fig. 1B). The rest of the protocol was the same as that described for intact plants.

Finally, in some experiments, three identical electrodes (either H+ or Ca2+) were positioned 0.4 mm apart along the seedling surface (Fig. 1C). Unilateral BL was given either from the hook or cotyledon end, and net fluxes of the ion were simultaneously measured for the three locations. In such experiments, etiolated plants were kept in the red light background for about 2 h before measurements to have their hook unfold and the cotyledons oriented horizontally.

Statistics.

Five to ten seedlings were measured for each treatment and at each location. In most figures, several representative examples are shown to illustrate the variability of kinetics in ion flux responses. Statistical information on the magnitudes of ion flux changes (calculated as shown in Fig. 2) is presented in Fig. 3. Significance of difference between means was based on the use of Student's t test.

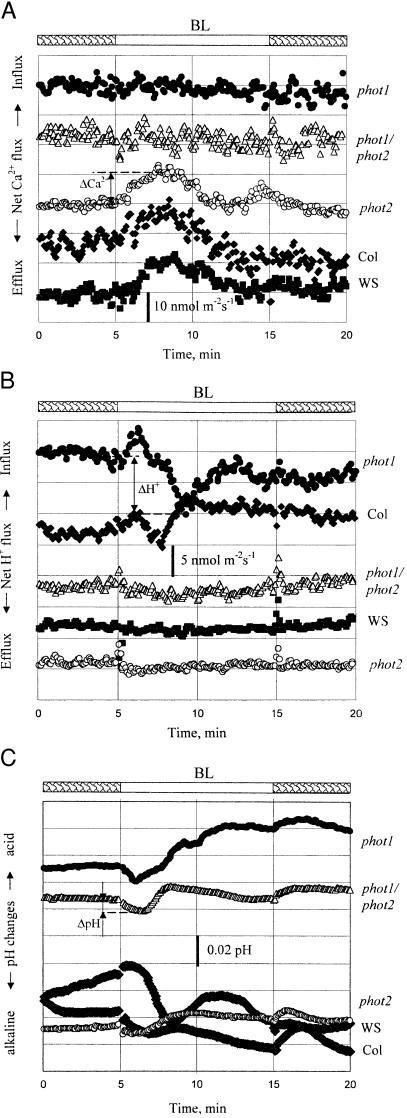

Figure 2.

Net Ca2+ (A) and H+ (B) fluxes (influx positive) and pH changes (C) measured from decapitated hypocotyls in response to BL of 15 mmol m−2 (given as a 10-min pulse at 5 min). One of five to eight representative examples is shown for each WT ecotype Col (closed diamonds) and WS (closed squares), phot1(closed circles), phot2 (open circles), and phot1/phot2 (closed triangles) mutants. Each point represents the ion flux averaged over a 10-s interval. In A, ΔCa2+ is the change (shown for phot2) from initial flux to the maximum flux at about 3 min after BL onset. In B, ΔH+ is the change for phot1 from initial flux to the minimum at about 4 min after BL onset. In C, ΔpH is the change (shown for phot1/phot2) from the initial pH to the maximum pH value within the first 5 min after BL onset.

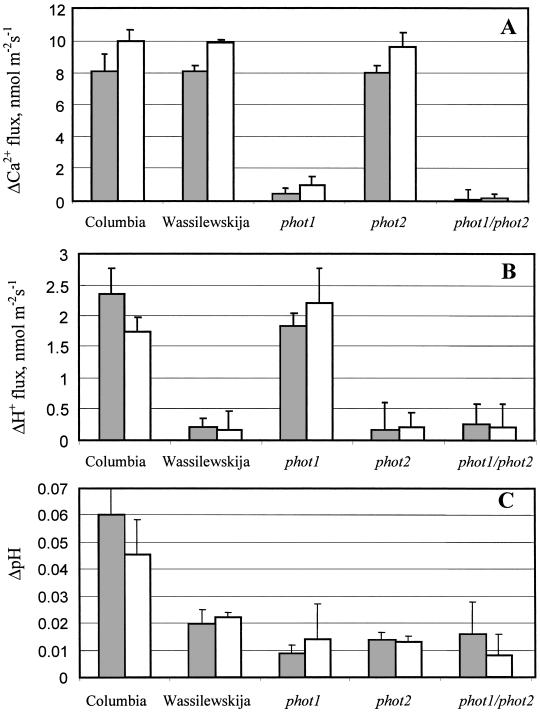

Figure 3.

Magnitude of changes in net Ca2+ (A) and H+ (B) flux and external pH (C) measured from cotyledon region (filled columns) and decapitated hypocotyl (open columns) in response to BL given as described in Fig. 2. Error bars are SEM (n = 5–8)

Results

BL exposure caused significant changes in membrane-transport activity in etiolated Arabidopsis seedlings (Figs. 2–4).

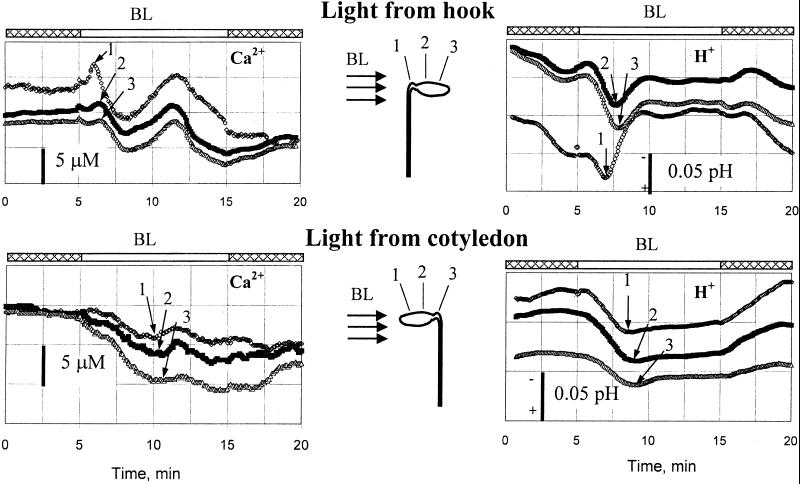

Figure 4.

Two typical examples of sequential time delays in changes of Ca2+ and H+ concentrations in Col seedlings. (Upper) Changes in external pH and Ca2+ concentration measured at three different spots, separated by about 0.4 mm in response to unilateral BL from the hook side. (Lower) Responses from other plants having BL given from the cotyledon side. The light treatment was given between 5 and 15 min.

Ca2+ flux kinetics was different for WT and mutant plants. Calcium flux responses were pronounced in the decapitated hypocotyl and in the cotyledon regions of intact plants in both the WT and phot2 plants but were lacking in phot1 and phot1/phot2 mutants (Figs. 2A and 3A). The maximum influx occurred between 2 and 4 min after BL onset, with subsequent reduction of Ca2+ fluxes. The ΔCa2+ fluxes that are presented in Fig. 3 were calculated as the difference for each plant between the flux before BL onset and the flux maximum. ΔCa2+ values (8–10 nmol⋅m−2⋅s−1) were very similar for both WT and phot2 mutant, with higher values for decapitated hypocotyls for all lines investigated (Fig. 3A).

Although the maximum response occurred about 3 min after BL onset, the notable feature of Ca2+ kinetics was the absence of any discernable delay in net Ca2+ flux responses (within the 10-sec time resolution of the MIFE system).

Changes in net H+ fluxes were ecotype specific with pronounced responses during 2–4 min for both cotyledons and decapitated hypocotyls in the Col ecotype and phot1 mutant with Col background (Figs. 2B and 3B). The BL onset led to a slight but pronounced “drop” in net H+ flux (increased efflux; Fig. 2B) of several nmol⋅m−2⋅s−1, with subsequent minor recovery. WS wild-type, phot2, and phot1/phot2 mutants with WS background did not have clear changes in H+ fluxes during BL exposure. Statistical analysis has not shown a significant difference between BL-induced H+ fluxes measured from WTs and their corresponding mutants for either cotyledons or decapitated hypocotyls (Fig. 3B).

Another characteristic feature of H+ flux responses was a significant delay of up to 2 min between BL onset and the moment when net H+ flux started to change.

Interestingly, H+ fluxes were not always accompanied by consistent pH changes, which could reflect an involvement of CO2 in the BL response. In the first 1–3 min after BL onset, there was an increase in pH values, up to 0.07 pH units for some plants, making the bath solution more alkaline. This response was transient, reaching maximum pH at 1–4 min with a subsequent decrease. As for H+ fluxes, the most pronounced pH changes were present in the Col ecotype. However, phot1 mutants exhibited significantly smaller pH changes despite being in the Col background and despite showing large changes in H+ flux. For WS and its mutants, these changes were much smaller (about 0.02 pH) (Fig. 3C).

Another finding was a sequential delay of BL-induced changes in net H+ and Ca2+ fluxes along the cotyledon–hook axis (regardless of orientation). This delay is illustrated in Fig. 4, where two typical examples of wave-like changes in Ca2+ and H+ concentrations are shown. Fig. 4 Upper illustrates changes in external pH and Ca2+ concentrations measured at three different spots (end of the hypocotyl, on the border between hypocotyl and cotyledon, and toward the end of the cotyledon) along about 0.8 mm, in response to unilateral BL illumination from the hook side. Fig. 4 Lower shows similar measurements from another plant in response to the BL pulse given from the cotyledon side. In both cases, the first pH and Ca2+ changes were observed at the spot closest to the light source.

Discussion

Since Darwin's studies, the location of phototropic receptors has been in question. At our present level of knowledge, at least two types of BL receptors are believed to mediate higher plant phototropic responses: cryptochromes and phototropins (21, 31). Molecular studies suggest that phototropins are associated with the plasma membrane (32), and cryptochromes were found predominantly located in the nucleus (33–35). The distribution of these photoreceptors in plant tissues remains unclear. CRY1 and CRY2 genes (involved in anthocyanin formation, phototropism, cotyledon opening, flowering, chalcone synthase expression, hypocotyl extension, leaf growth, and stem growth) (36) were found to be expressed throughout the whole seedling and mature plant (37). However, the location of phototropin expression in the whole seedling is still to be established, and there are some indications that its concentration is highest in the upper part of the hook (W. R. Briggs, personal communication).

Our observation of the response in decapitated hypocotyls (Fig. 2) shows that the photoreceptors mediating BL-induced Ca2+ and H+ fluxes are present in the rest of the seedling and probably in the cotyledons as well (Fig. 4). However, when plants were illuminated from the cotyledon side (Fig. 4 Lower), the response was less pronounced for both Ca2+ concentration and pH. Thus some components of the BL signal cascade that leads to changes in ion concentrations, if not the BL photoreceptors themselves, may be more abundant or active in the hook region of the seedling than in the cotyledon.

In this work, we observed a difference in BL-induced Ca2+ flux kinetics between both the WT ecotypes and the phot1 and phot1/phot2 mutants. This difference could be explained if PHOT1 and PHOT2 regulate Ca2+ entry into the cytoplasm through different membranes: PHOT1 through the plasma membrane and PHOT2 through endomembranes. It is reasonable to suggest that some steps in BL signal transduction require a rise in [Ca2+]cyt to a certain level. In WTs, this rise is achieved by Ca2+ influx from both apoplast and internal compartments. In phot1 mutants, this Ca2+ influx occurs only from internal compartments and in phot2, only from the apoplast. This proposition can explain, (i) the lack of Ca2+ influx from the apoplast in phot1 and phot1/phot2 mutants observed in this work (Fig. 2A); (ii) the lower (but not abolished) rise in [Ca2+]cyt after BL onset in phot1 seedlings found by Baum et al. (18); and (iii) why phot1 mutants are still able to bend toward BL, although they need much higher fluence rate and dose (22). The last happens because in phot1 the BL signal still reaches the target [Ca2+]cyt by using the PHOT2 pathway. When the activation of Ca2+ transporters is interrupted in both BL signal pathways, in the phot1/phot2 mutant, no phototropic response occurs.

Another interesting finding was a wave-like change in Ca2+ and H+ concentration along the horizontal cotyledons (Fig. 4). The sequential delay in ion flux responses was larger for the hook–cotyledon part than between the two points in the cotyledon (Fig. 4 Upper). The apparent wave started at the closest point to the BL source along the cotyledon–hook axis regardless of the orientation of the axis to the BL source (Fig. 4).

A simple interpretation of the apparent wave is that cells more distant from the light source receive lower BL fluence rates, mostly because of absorption by intervening tissue. BL-induced phototropic responses are known to be dose-dependent (13). Assuming that a certain threshold BL dose is required to initiate ion flux kinetics in Arabidopsis, tissues with these lower fluence rates will require a longer time to reach the threshold dose. The observed sequential delay in ion flux responses of itself provides a possible mechanism for the polarity leading to bending toward the BL source. Changes in both Ca2+ concentrations and pH are delayed by more than 1 min between hook and cotyledon (Fig. 4), which could be enough to induce a signal cascade in the plant tissues.

Another possibility is that the observed sequential delay in Ca2+ concentration changes reflects changes in [Ca2+]cyt. Such changes may play some regulatory role. There is growing evidence that Ca2+ waves often spread across large groups of similar contiguous cells (38–41). The reported speed range of 1–25 μm⋅s−1 (38) is also consistent with our observations (Fig. 4). Such Ca2+ waves are believed to be crucial for the growth of pollen tubes (42) or root hairs (43) and for coordination of physiological processes between spatially separated plant tissues (39). A Ca2+ wave in staminal hairs of Setcreasea may spread from one cell to another through plasmodesmata, with a speed of about 10 μm/sec (42). The model suggested by these authors involves rapid and transient increase in cytosolic Ca2+ on both sides of the plasmodesmata, followed by plasmodesmatal closure and reopening within 30 s. Their model requires Ca2+ uptake via the plasma membrane to replenish Ca2+ losses from the internal stores, which is also consistent with the BL-induced net Ca2+ uptake measured in our experiments on WT and phot2 seedlings (Figs. 2A and 3A).

Although BL also affects H+ fluxes and pH, it appears that responses in H+ and Ca2+ fluxes are not linked, because (i) when changes were observed for both ions, changes in Ca2+ flux started almost immediately, whereas H+ flux showed a lag of about 1.5 min; and (ii) in WS ecotype, the normal Ca2+ influx was observed under BL, but H+ flux barely changed. It also appears that the changes in H+ fluxes are not a product of PHOT1 and PHOT2, because there was no significant difference between the WTs and their mutants (Fig. 3B).

From our observations and analysis, we suggest that PHOT1 regulates Ca2+ uptake into the cytoplasm from the apoplast, and that some stage of phototropins' signal transduction pathway requires a rise in [Ca2+]cyt to a certain level. Specific details of these processes may be revealed by further studies involving triple/quadruple mutants deficient in cryptochromes and phototropins and by the concurrent measurement of net ion fluxes and cytosolic pH and Ca2+ changes by using imaging techniques.

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. W. R. Briggs and Dr. T. Sakai for their kind supply of the mutant lines. This work was supported by the Australian Research Council (Grant A00001144 to S.S.).

Abbreviations

- BL

blue light

- WT

wild type

- Col

Columbia

- WS

Wassilewskija

Footnotes

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

References

- 1.Briggs W R, Huala E. Annu Rev Cell Dev. 1999;15:33–62. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.15.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blum D E, Neff M M, Van Volkenburgh E. Plant Physiol. 1994;105:1433–1436. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.4.1433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fankhauser F, Chory J. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1997;13:203–229. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.13.1.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Racusen R H, Galston A W. In: Encyclopaedia of Plant Physiology: New Ser. Pirson A, Zimmerman M H, editors. 16B. Berlin: Springer; 1982. pp. 687–703. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spalding E P. Plant Cell Environ. 2000;23:665–674. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3040.2000.00594.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stahlberg R, Cosgrove D J. Plant Physiol. 1997;113:209–217. doi: 10.1104/pp.113.1.209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shrank A R. Plant Physiol. 1946;21:362–365. doi: 10.1104/pp.21.3.362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Newman I A. Aust J Biol Sci. 1963;16:629–646. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hartman E. Physiol Plant. 1975;33:266–275. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Racusen R H, Galston A W. Plant Physiol. 1980;66:534–535. doi: 10.1104/pp.66.3.534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Parks B M, Cho M H, Spalding E P. Plant Physiol. 1998;118:609–615. doi: 10.1104/pp.118.2.609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Newman I A, Sullivan J K. In: Transport and Transfer Processes in Plants. Wardlaw I F, Passioura J B, editors. New York: Academic; 1976. pp. 153–159. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Spalding E P, Cosgrove D J. Planta. 1989;178:407–410. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elzenga J T M, Staal M, Prins H B A. J Exp Bot. 1997;48:2055–2061. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Elzenga J T M, Staal M, Prins H B A. Plant J. 2000;25:377–389. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2000.00748.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cho M H, Spalding E P. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:8134–8138. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.15.8134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Suh S, Moran N, Lee Y. Plant Physiol. 2000;123:833–843. doi: 10.1104/pp.123.3.833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baum G, Long J C, Jenkins G I, Trewavas A J. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:13554–13559. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.23.13554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang X, Iino M. Plant Physiol. 1998;117:1265–1279. doi: 10.1104/pp.117.4.1265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gehring C A, Williams D A, Cody S H, Parish R W. Nature (London) 1990;345:528–530. doi: 10.1038/345528a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Briggs W R, Beck C F, Cashmore A R, Christie J M, Hughes J, Jarillo J A, Kagawa T, Kanegae H, Liscum E, Nagatani A, et al. Plant Cell. 2001;13:993–997. doi: 10.1105/tpc.13.5.993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sakai T, Kagawa T, Kasahara M, Swartz T E, Christie J M, Briggs W R, Wada M, Okada K. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:6969–6974. doi: 10.1073/pnas.101137598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lascève G, Leymarie J, Olney M A, Liscum E, Christie J M, Vavasseur A, Briggs W R. Plant Physiol. 1999;120:605–614. doi: 10.1104/pp.120.2.605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jones D L, Shaff J E, Kochian L V. Planta. 1995;197:672–680. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shabala S N, Newman I A, Morris J. Plant Physiol. 1997;113:111–118. doi: 10.1104/pp.113.1.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Newman I A. Plant Cell Environ. 2001;24:1–14. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3040.2001.00661.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hush J M, Newman I A, Overall R L. J Exp Bot. 1992;43:1251–1257. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huala E, Oeller P W, Liscum E, Han I S, Larsen E, Briggs W R. Science. 1997;278:2120–2123. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5346.2120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shabala S. Plant Cell Environ. 2000;23:825–837. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Neff M M, Chory J. Plant Physiol. 1998;118:27–36. doi: 10.1104/pp.118.1.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Briggs W R, Olney M A. Plant Physiol. 2001;125:85–88. doi: 10.1104/pp.125.1.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Short T W, Briggs W R. Annu Rev Plant Mol Biol. 1994;45:143–171. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cashmore A R, Jarillo J A, Wu Y-J, Liu D. Science. 1999;284:760–765. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5415.760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Guo H, Duong H, Ma N, Lin C. Plant J. 1999;19:279–287. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1999.00525.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kleiner O, Kircher S, Harter K, Batschauer A. Plant J. 1999;19:289–296. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1999.00535.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Batschauer A. Cell Mol Life Sci. 1999;55:153–165. doi: 10.1007/s000180050282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ahmad M, Cashmore A R. Nature (London) 1993;366:162–166. doi: 10.1038/366162a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jaffe L F. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:9883–9887. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.21.9883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tucker E B, Boss W F. Plant Physiol. 1996;111:459–467. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.2.459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Holdaway-Clarke T L, Feijo J A, Hacket G R, Kunkel J G, Hepler P K. Plant Cell. 1997;9:1999–2010. doi: 10.1105/tpc.9.11.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Grabov A, Blatt M R. J Exp Bot. 1998;49:351–360. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Franklin-Tong V E, Drobak B K, Allan A C, Watkins P A C, Trewavas A J. Plant Cell. 1996;8:1305–1321. doi: 10.1105/tpc.8.8.1305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yang Z B. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 1998;1:525–530. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5266(98)80046-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]