Abstract

Ferredoxin 1 (FDX1) emerges as a crucial regulator of autophagy and copper metabolism in ovarian cancer (OC), as revealed by this investigation. Predominantly localized to the cytoplasm and mitochondria, FDX1 coordinates autophagic activity by modulating the AMPK and mTOR signaling pathways. Its role extends to preserving mitochondrial integrity and facilitating sulfation of DLAT/DLST, ensuring effective autophagic flux. Knockdown of FDX1 disrupts these processes, exacerbating mitochondrial dysfunction. In vivo studies further demonstrate that overexpressing FDX1, combined with Compound C treatment, markedly inhibits tumor growth and Ki67 expression. These results position FDX1 as a promising target for therapeutic strategies aimed at exploiting autophagy to hinder OC progression.

Subject terms: Ovarian cancer, Ovarian cancer

Introduction

In recent years, there has been a continuous increase in the incidence and mortality rates of cancer, making it a top priority in global public health1. Ovarian cancer (OC) stands out as a leading cause of death among gynecologic malignancies. Due to the lack of effective early diagnostic markers and symptoms, many patients are diagnosed at advanced stages, posing significant challenges to treatment and prognosis2–5. Therefore, investigating the mechanisms of OC development, discovering new prognostic markers, and identifying therapeutic targets hold paramount significance6. Our study focuses on a novel form of cell death in OC, known as copper-induced cell death, and the role of the key mediator gene, Ferredoxin 1 (FDX1).

Copper-induced cell death is a recently identified programmed cell death pathway characterized by toxic damage to the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) caused by elevated copper ion levels7,8. FDX1 plays a crucial role in this process, suggesting that it could be a significant target for researching copper-induced cell death9–11. However, studies on the role of FDX1 in OC and its implications are limited12. Therefore, our research primarily delves into the molecular mechanisms of FDX1 in OC progression.

We conducted our research using multiple publicly available bioinformatics databases. Initially, we analyzed data from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) and the Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) datasets to investigate the correlation between FDX1 mRNA levels and clinical pathological features of OC. Subsequently, we assessed the protein levels and genetic variations of FDX1 using the CTPAC and cBioPortal databases. Moreover, to explore the impact of FDX1 on the tumor immune microenvironment, we employed the CIBERSORT algorithm and the TISIDB database, while for investigating the influence of FDX1 expression on drug sensitivity, we utilized the CellMiner and GDSC databases. Furthermore, we employed methodologies such as Gene Ontology (GO), Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG), and Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) to explore the potential mechanisms through which FDX1 functions.

This study aims to reveal the specific mechanisms by which the copper-induced cell death-related gene FDX1 participates in the progression of OC through bioinformatics analysis and in vivo and in vitro experimental validation. Hopefully, the findings from this research will offer new perspectives and therapeutic strategies for treating OC. It also provides new targets and directions for investigating the mechanisms of copper metabolism and autophagy crosstalk.

Results

Upregulation of FDX1 expression in OC and its close association with drug sensitivity

Copper-induced cell death is a newly discovered mechanism, distinct from all known cell death regulatory pathways, where FDX1 serves as a crucial regulatory factor and core gene for protein lipidation induced by copper ions7,13. FDX1 has been shown to exhibit differential expression in various cancer types, yet its mechanism of action in OC remains largely unknown.

In this study, we initially analyzed FDX1 expression in OC through the TCGA database, revealing that FDX1 mRNA levels are relatively elevated in OC tissues, with a gradual upregulation of mRNA expression as tumor grade increases (Fig. 1A, B). Additionally, protein expression of FDX1 was analyzed through the CTPAC database (Fig. 1B), showing higher FDX1 protein expression in OC compared to normal tissues (Fig. 1D), although no significant differences were observed in protein expression levels among different tumor grades (Fig. 1E). Subsequent analysis of FDX1’s specific expression in different p53 mutant subtypes revealed no significant differences in mRNA and protein expression levels across these subtypes (Fig. 1C; Fig. 1F). Finally, results from the HPA database demonstrated significant expression of FDX1 in multiple OC cell lines (Fig. 1G). Overall, these findings indicate an upregulation of FDX1 expression in OC, suggesting its potential key role in the initiation and progression of OC.

Fig. 1. Differential expression of FDX1 in OC and normal samples.

A Analysis of FDX1 mRNA levels in tumor tissues and normal tissues samples based on TCGA and GTEx data, *** indicates P < 0.001; B Analysis of FDX1 mRNA levels in tumor samples of patients with different Tumor grades based on TCGA data; C Analysis of FDX1 mRNA levels in tumor samples of different p53 mutation types based on TCGA data; D Analysis of FDX1 protein expression levels in tumor tissues and normal tissues samples based on CTPAC data; E Analysis of FDX1 protein expression levels in tumor samples of patients with different Tumor grades based on CTPAC data; F Analysis of FDX1 protein expression levels in tumor samples of different p53 mutation types based on CTPAC data; G Expression analysis of FDX1 in various OC cell lines using the HPA database.

Furthermore, based on the cBioPortal database, it was noted that genetic variations of FDX1 in OC occur at a frequency of approximately 3%, with FDX1 amplification being a predominant type of mutation (Supplementary Fig. 1A, B). Additionally, TMB, which represents the level of gene mutations in tumor cells, was examined for its association with FDX1, revealing a positive correlation between FDX1 expression and TMB (Supplementary Fig. 1C), possibly due to the higher transcriptional expression of FDX1 compared to normal tissues.

Moreover, we investigated the impact of FDX1 expression on the sensitivity to anti-cancer drugs. Initially, using the CellMiner database, we analyzed the relationship between drug sensitivity and FDX1 expression. The results showed a significant correlation between FDX1 expression and the sensitivity to six therapeutic drugs (Ifosfamide, Everolimus, JNJ-42756493, Ribavirin, Nelarabine, and Vorinostat) (Supplementary Fig. 2A). Additionally, utilizing the R package “oncoPredict” to calculate the IC50 values of drugs in the GDSC database, 95 drugs exhibited differential sensitivity between high and low FDX1 expression groups, including common chemotherapy drugs such as Bortezomib, Taselisib, and Fulvestrant (Supplementary Fig. 2B). While these drugs may not be standard treatments for OC in recent years, they do partly demonstrate the association between FDX1 and drug sensitivity, thus providing insights into the potential application of FDX1 in OC. For instance, Taselisib, a PI3K inhibitor, may be influenced by FDX1 due to its role in cellular energy metabolism, potentially affecting the activity of the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway14. Therefore, further exploration of the potential mechanisms through which FDX1 exerts its effects will be pursued.

FDX1 regulates autophagy pathway through the AMPK/mTOR signaling pathway to impact the occurrence and progression of OC

To elucidate the role of FDX1 in OC, we identified 291 FDX1 co-expressed genes in OC tissues using data from the TCGA dataset (filter criteria: |r | > 0.3 and P < 0.05) (Fig. 2A). Subsequently, we performed GO and KEGG enrichment analyses, revealing that FDX1-related genes were primarily enriched in GO terms related to histone modification and pathways, including the AMPK, mTOR, autophagy, and cancer pathways (Fig. 2B, C).

Fig. 2. Identification and functional enrichment analysis of FDX1-related genes.

A Heatmap of FDX1-related genes in TCGAOC; B GO functional enrichment analysis of FDX1-related genes; C KEGG enrichment analysis of FDX1-related genes.

Furthermore, based on TCGA data, we divided all tumor samples into high and low FDX1 expression groups according to the median FDX1 expression levels. GSEA showed that FDX1 was significantly associated with glycolysis, estrogen response, mTOR pathway, oxidative phosphorylation, peroxisomes, protein secretion, and reactive oxygen species (Supplementary Fig. 3), which was consistent with the results of the GO and KEGG enrichment analyses.

Utilizing the STRING database and querying “FDX1” yielded the top 25 proteins most closely interacting with FDX1 (Supplementary Fig. 4A). Subsequently, we conducted GO and KEGG enrichment analyses on these 26 proteins, including FDX1, to further validate the protein functions of FDX1. The results indicated that the main functions of FDX1 included electron transfer activity, mitochondrial inner membrane, mitochondrial respiratory chain complex, NADH dehydrogenase activity, oxidative reductase activity, NAD(P)H activity, active transmembrane transporter activity, and coupling of ATP synthesis with electron transport and oxidation-reduction processes (Supplementary Fig. 4B, C). Notably, in OC tissue samples, FDX1 expression exhibited significant positive correlations with autophagy-related genes (VMA21, ATG5, ATG3, ATG4A, ATG4C) (Supplementary Fig. 4D, E).

Literature evidence suggests that FDX1 primarily participates in intracellular electron transfer processes, impacting various metabolic pathways. The overexpression of FDX1 may affect cellular energy metabolism and redox status15, aligning with the findings of this study. AMPK functions as an energy sensor within cells, being activated under low cellular energy levels (e.g., decreased ATP levels). AMPK activation can promote autophagy by inhibiting mTORC116. Recent studies have shown that copper ions can trigger macroautophagy/autophagy, a lysosome-dependent degradation pathway that plays a dual regulatory role in cell survival or death under various stress conditions17,18.

Therefore, we postulate that the genes related to copper-induced cell death may indirectly activate AMPK through FDX1 by impacting cellular energy metabolism, promoting autophagy by inhibiting the mTOR signaling pathway, and thereby exerting an impact on the progression of OC.

Upregulation of FDX1, a copper-induced cell death-related gene, is closely associated with increased of autophagy in clinical samples of OC patients

In order to validate the aforementioned analyses, we collected tumor tissue samples from 20 OC patients (OC group) and 3 normal ovarian tissue samples (Normal group). Through RT-qPCR, Western blot experiments, and immunohistochemical staining to detect FDX1 expression, we observed a significant upregulation of FDX1 in OC (Fig. 3A–C).

Fig. 3. Expression of FDX1 in clinical samples of OC patients and its association with autophagy levels.

RT-qPCR (A), Western blot (B), and immunohistochemistry (C) were utilized to assess the expression levels of FDX1 in Normal and OC groups, with scale bars = 50 μm; D Western blot was performed to analyze the expression levels of LIAS and Lipoy-DLAT in Normal and OC groups; E Copper ion concentration in Normal and OC groups was measured using a assay kit; F Correlation analysis between FDX1 protein expression and copper ion concentration in tumor tissue samples from OC patients; G Western blot analysis of the expression levels of LC3-II/I and Beclin-1 in Normal and OC groups; H Correlation analysis of FDX1 and LC3-II/I protein expression in tumor tissue samples from OC patients; I Correlation analysis of FDX1 and Beclin-1 protein expression in tumor tissue samples from OC patients; J Mitochondria labeled with MitoTracker (in red) and FDX1 (in green), white arrows indicate representative mitochondria in OC cells stained with FDX1 and MitoTracker, with scale bars = 25 μm and 15 μm; Normal group, n = 3, OC group, n = 20.

Subsequently, Western blot analysis was conducted to measure the expression of copper-induced cell death-related proteins (LIAS and Lipoy-DLAT) and the levels of copper ions. The results showed that compared to the Normal group, the expression of LIAS and Lipoy-DLAT in the OC group was significantly downregulated, while the copper ion levels were significantly elevated (Fig. 3D, E). Further correlation analysis between FDX1 expression and copper ion levels in tumor tissue samples from OC patients revealed a significant positive correlation (Fig. 3F). This suggests that the upregulation of FDX1 in clinical samples of OC patients may be a key factor leading to the increase in copper-induced cell death levels, with FDX1 being a core gene involved in copper-induced cell death in OC samples.

Autophagy-related proteins (LC3-II/I, Beclin-1) were assessed through Western blot analysis. We observed a significant upregulation of LC3-II/I and Beclin-1 in the OC group compared to the Normal group (Fig. 3G). The correlation analysis results showed a significant positive correlation between FDX1 and the protein expression of LC3-II/I and Beclin-1 (Fig. 3H, I), consistent with the earlier TCGA data analysis results (Supplementary Fig. 4D, E). These results indicate a close association between the upregulation of FDX1 and the upregulation of autophagy levels in clinical samples of OC patients.

Additionally, we found that FDX1 accumulated in the cytoplasm and co-stained with mitochondria labeled by MitoTracker Red in OC cells (Fig. 3J). FDX1, an iron-sulfur protein primarily involved in electron transfer within the mitochondria, has been implicated in regulating copper ion-induced cell death. Recent studies suggest that FDX1 may play a crucial role in modulating copper ion metabolism-induced cell death by interacting with copper ions in mitochondria through its iron-sulfur cluster (LIAS containing an iron-sulfur cluster)19. It is noteworthy that in tumor tissues, the high expression of FDX1 may help cells adapt to copper ion toxicity by maintaining mitochondrial function stability15, possibly explaining the upregulation of FDX1 in OC tumor samples.

FXD1 serves as a key regulator of copper ion-induced cell death and an upstream regulator of cellular protein lipoylation, which is a mitochondrial lipid-based post-translational modification essential for four mitochondrial enzymes crucial for TCA cycle function19. Thus, we hypothesize that the state of the iron-sulfur clusters affected by the copper-induced cell death gene FDX1 is vital for the activity of LIAS, thereby influencing mitochondrial metabolism and subsequently impacting cell autophagy.

FDX1 is a key gene regulating copper metabolism and autophagy crosstalk in OC cells

Clinical experiments have preliminarily elucidated the crosstalk between copper metabolism and autophagy in OC. To further validate this, we conducted cellular experiments. Initially, we treated two OC cell lines (SK-OV-3 and CAOV-3) with the copper-induced cell death inducer Elesclomol, measured copper ion levels using a reagent kit, and assessed the expression of FDX1 and autophagy-related proteins through Western blot analysis. The results indicated that compared to the Control group, the Elesclomol group exhibited elevated copper ion levels (Supplementary Fig. 5A), along with upregulation in the expression of FDX1 and autophagy-related proteins (Supplementary Fig. 5B, C). This suggests that the Elesclomol inducer of copper-induced cell death can upregulate FDX1 expression, consequently promoting copper metabolism and enhancing autophagy in OC cells. Subsequently, we proceeded with the CAOV-3 cell line due to its more significant variations for further experiments.

Our bioinformatics analysis and clinical findings have suggested that FDX1 may serve as a crucial gene regulating autophagy in OC cells induced by copper-induced cell death. We then manipulated the expression of FDX1 in CAOV-3 cells by overexpression/silencing to observe the impact on autophagy and copper metabolism. Firstly, we designed three shRNA sequences targeting FDX1 and validated the silencing efficiency. We selected the most effective sh-FDX1-3 sequence for subsequent experiments (Supplementary Fig. 6A, B). The effects of FDX1 overexpression are depicted in Supplementary Fig. 6C, D.

Overexpression of FDX1 led to a significant elevation in both intracellular copper ion levels and FDX1 expression, along with a pronounced decrease in LIAS and Lipoy-DLAT protein levels, whereas silencing FDX1 resulted in the opposite trends (Fig. 4A, B). Furthermore, cells from different groups were treated with varying concentrations of Elesclomol-Cu (ratio=1:1) for 72 h. Cell viability was assessed using the CCK-8 assay; proliferation capacity was evaluated through colony formation experiments, cell migration was determined by scratch assays, and cell invasion was assessed via Transwell assays. The results demonstrated that compared to the oe-NC group, the oe-FDX1 group displayed significantly increased cell viability, proliferation, migration, and invasion capabilities. In contrast, the sh-FDX1 group exhibited lower cell viability and decreased proliferation, migration, and invasion abilities compared to the sh-NC group (Fig. 4B–E). These findings indicate that under Elesclomol-Cu treatment conditions, the overexpression/silencing of FDX1 can significantly modulate the vitality, proliferation, migration, and invasion abilities of OC cells, suggesting that FDX1 exerts its effects by modulating copper metabolism.

Fig. 4. Impact of FDX1 overexpression/silencing on copper metabolism and autophagy in OC cells.

A Copper ion concentrations were measured using a reagent kit; B Western blot analysis was performed to assess the protein expression of LIAS and Lipoy-DLAT in the cell groups; C Cell viability and growth were determined by treating cells with different concentrations of elesclomol-Cu (ratio = 1:1) for 72 h, followed by CCK-8 assay; D Clonogenic assay was used to evaluate the proliferation capacity of the cell groups; E Scratch assay was conducted to assess cell migration ability, where scale bar = 100 μm; F Transwell assay was employed to measure cell invasion ability, with a scale bar = 50 μm; G Western blot analysis was utilized to detect the protein expression of LC3-II/I and Beclin-1 in the cell groups; H Mitochondrial membrane potential was examined using JC-1 staining; I Mitochondrial morphology was observed by transmission electron microscopy, where scale bar = 500 nm/1 μm; * indicates P < 0.05 compared to the oe-NC or sh-NC groups, and all cell experiments were repeated three times.

Western blot analysis was conducted to assess the expression of autophagy-related proteins, transmission electron microscopy was used to observe mitochondrial structure, and JC-1 staining was performed to measure mitochondrial membrane potential. Results showed that compared to the oe-NC group, the oe-FDX1 group exhibited upregulation of LC3-II/I and Beclin-1 proteins, a significant increase in mitochondrial membrane potential, significantly elevated mitochondrial membrane potential, and observed reduction in mitochondrial shrinkage, cristae reduction, and increased membrane density. Conversely, the sh-FDX1 group displayed downregulation of LC3-II/I and Beclin-1 proteins, no increase in autophagosome or autolysosome formation, a marked decrease in mitochondrial membrane potential, and signs of mitochondrial injury repair compared to the sh-NC group (Fig. 4F–I). These findings suggest that FDX1 regulates autophagy in OC cells, possibly by influencing mitochondrial function.

FDX1 activates AMPK to inhibit the mTOR signaling pathway and promote autophagy in OC cells

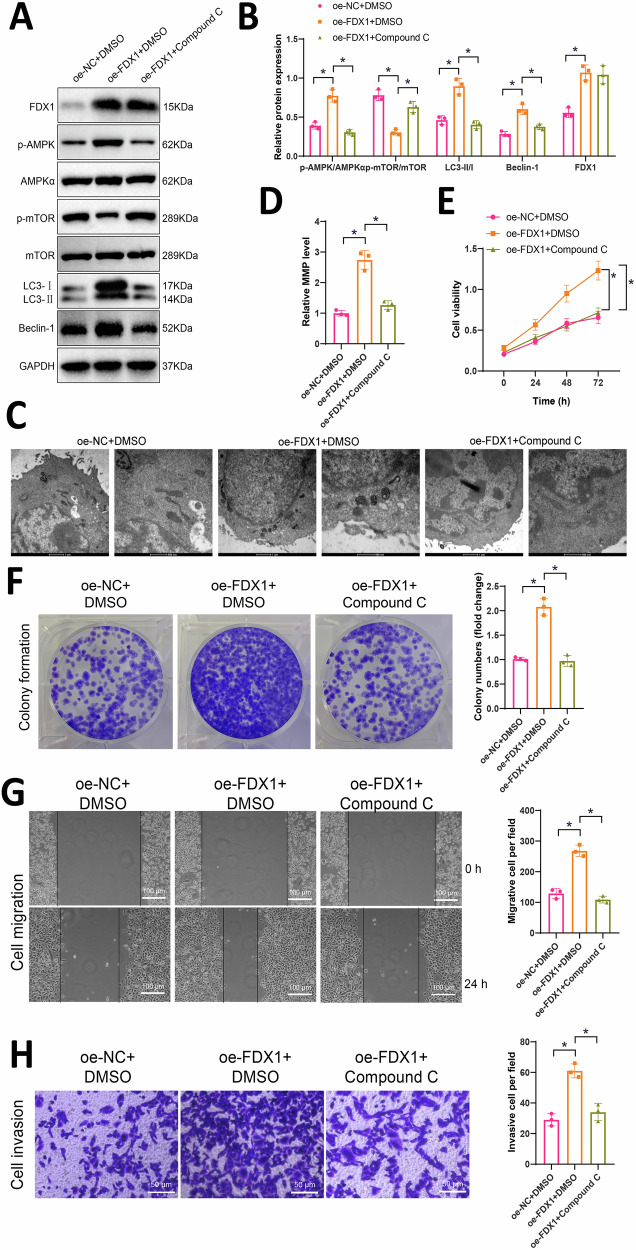

The bioinformatics analysis revealed that FDX1 exerts its effects by activating AMPK and subsequently inhibiting the mTOR signaling pathway. Given that the AMPK/mTOR pathway is crucial in autophagy regulation, we further investigated the underlying mechanisms through cellular experiments. Initially, we overexpressed FDX1 while concurrently treating the cells with the AMPK inhibitor Compound C. Specifically, cells were divided into oe-NC + DMSO group, oe-FDX1 + DMSO group, and oe-FDX1 + Compound C group. Subsequently, Western blot analysis was performed to evaluate the expression changes of factors related to the AMPK/mTOR signaling pathway and autophagy-related proteins. Compared to the oe-NC + DMSO group, the oe-FDX1 + DMSO group exhibited a significant increase in FDX1 expression, an upregulation of p-AMPK/AMPKα protein expression, and a notable downregulation of p-mTOR/mTOR. In contrast, compared to the oe-FDX1 + DMSO group, the oe-FDX1 + Compound C group exhibited a significant downregulation of p-AMPK/AMPKα protein expression and marked upregulation of p-mTOR/mTOR (Fig. 5A, B). These results suggest that overexpression of FDX1 can activate AMPK to suppress the mTOR signaling pathway. So, does FDX1 regulate OC cell proliferation, migration, invasion, and autophagy through the AMPK/mTOR signaling pathway?

Fig. 5. The impact of FDX1 on the AMPK/mTOR signaling pathway in OC cells: proliferation, migration, invasion, and autophagy.

A Western blot analysis was performed to evaluate the expression of AMPK/mTOR signaling pathway-related factors and autophagy-related proteins in each group of cells; B Quantitative results of Figure A; C Observation of mitochondrial morphology in cells by transmission electron microscopy, where scale bar=500 nm/1 μm; D Detection of mitochondrial membrane potential using JC-1; E Cell viability assessed by CCK-8 assay in each group of cells; F Colony formation assay to evaluate the proliferation capacity of each group of cells; G Scratch assay measuring the migration ability of each group of cells, with a scale bar of 100 μm; H Transwell assay determining the invasion ability of each group of cells, with a scale bar of 50 μm; * represents statistical significance compared to the oe-NC + DMSO group or oe-FDX1 + DMSO group at P < 0.05; all cell experiments were repeated three times.

Comparing the oe-NC + DMSO group with the oe-FDX1 + DMSO group, we observed an increase in the expression of LC3-II/I and Beclin-1 proteins, a significant elevation in mitochondrial membrane potential, along with mitochondrial shrinkage, reduced cristae, and increased membrane density. In contrast, the oe-FDX1 + Compound C group exhibited a decrease in LC3-II/I and Beclin-1 protein expression, a significant decrease in mitochondrial membrane potential, and noticeable mitochondrial damage compared to the oe-FDX1 + DMSO group (Fig. 5A–D). These results indicate that overexpression of FDX1 can influence OC autophagy by modulating the AMPK/mTOR signaling pathway.

Subsequently, cell viability was assessed using the CCK-8 assay, clonogenic formation experiments were conducted to evaluate cell proliferation capacity, scratch assays were performed to measure cell migration, and Transwell assays were utilized to assess cell invasion. The results revealed that compared to the oe-NC + DMSO group, the oe-FDX1 + DMSO group showed significantly increased cell viability and enhanced proliferation, migration, and invasion capabilities. Conversely, the oe-FDX1 + Compound C group exhibited a significant decrease in cell viability and weakened proliferation, migration, and invasion abilities compared to the oe-FDX1 + DMSO group (Fig. 5E–H).

In conclusion, we propose that FDX1 activates AMPK to inhibit the mTOR signaling pathway, thereby promoting OC cell proliferation, migration, and invasion.

Overexpression of FDX1 promotes tumor growth in mice by regulating the AMPK/mTOR signaling pathway

In this study, we conducted in vivo animal experiments to validate whether overexpression of FDX1 activates AMPK to inhibit the mTOR signaling pathway and consequently affects tumor growth in mice. Subcutaneous xenograft tumor models were established by injecting OC cells overexpressing FDX1 into mice, followed by treatment with Compound C, resulting in three groups: oe-NC + DMSO, oe-FDX1 + DMSO, and oe-FDX1+Compound C.

Our findings revealed that compared to the oe-NC + DMSO group, the oe-FDX1 + DMSO group showed a significant increase in p-AMPK/AMPKα protein expression and a notable decrease in p-mTOR/mTOR levels in the tumor tissues. Additionally, when comparing the oe-FDX1 + DMSO group to the oe-FDX1+Compound C group, there was a significant decrease in p-AMPK/AMPKα expression and a marked increase in p-mTOR/mTOR levels (Fig. 6A). These results indicate that overexpression of FDX1 can activate AMPK to inhibit the mTOR signaling pathway.

Fig. 6. FDX1 mediates the effects of AMPK/mTOR signaling pathway on tumor growth in vivo.

A Western blot analysis was performed to evaluate the expression of FDX1, AMPK/mTOR signaling pathway-related factors, and autophagy-related proteins in each group of cells; B Tumor growth at different time points was monitored by measuring bioluminescence intensity; C Morphology of tumor tissues from each group of mice, with 3 representative examples shown for each group; D Tumor tissue weights for each group of mice; E Immunohistochemical staining was conducted to assess the protein expression levels of Ki67, LC3B and p62 in tumor tissues of each group of mice, with a scale bar of 50 μm; F Statistical analysis of Ki67, LC3B and p62 positive expression; * indicates P < 0.05 compared to the oe-NC + DMSO group or oe-FDX1 + DMSO group, with 5 mice in each group.

Tumor growth assessment was carried out at 1 and 2 weeks by observing bioluminescent images of the tumors in the mice. In the 4th week, the tumor tissues were dissected and examined for morphological changes, tumor weight measurements, and Ki67 immunohistochemical staining, as well as the detection of autophagy-related protein expression. Our observations indicated that, compared to the oe-NC + DMSO group, the oe-FDX1 + DMSO group exhibited faster tumor growth, a significant increase in tumor weight, a marked rise in Ki67 and LC3B positivity, a reduction in p62 protein positivity, and an upregulation of LC3-II/I and Beclin-1 protein expression. Conversely, compared to the oe-FDX1 + DMSO group, the oe-FDX1+Compound C group exhibited slower tumor growth, a significant decrease in tumor weight, decreased Ki67 and LC3B positivity, increased p62 protein positivity, and downregulated LC3-II/I and Beclin-1 protein expression (Fig. 6A–F). These results demonstrate that overexpression of FDX1 activates AMPK to inhibit the mTOR signaling pathway, inducing autophagy, and thereby promoting tumor growth in mice.

Discussion

In previous studies, FDX1 has long been recognized as a crucial gene involved in various cellular processes, particularly in copper ion metabolism20. However, it is only recently that scientists have begun to uncover the potential impact of FDX1 in OC12. This study demonstrates a significant upregulation of FDX1 expression in OC tissues, showing a clear correlation with copper ion levels. This discovery not only provides a new perspective on the biological function of FDX1 but also offers possible new targets for OC treatment.

In the pathological mechanisms of OC, the AMPK and mTOR signaling pathways play central regulatory roles, influencing not only cell proliferation and survival but also regulating cellular metabolism and energy balance21. AMPK serves as an energy sensor, activated under conditions of low cellular energy, while the mTOR signaling pathway promotes protein synthesis and cell proliferation when cellular growth conditions are favorable22,23. In this study, we found that FDX1 can activate AMPK to inhibit the mTOR signaling pathway, shedding new light on the regulation of autophagy in OC cells.

Autophagy is a cellular survival mechanism employed under conditions of nutrient deprivation or other stresses, maintaining cellular energy balance and survival by degrading and recycling cellular components24. In many cancers, autophagy assists cancer cells in adapting to stressful environments and promoting their survival and proliferation by eliminating damaged organelles and proteins25,26. However, excessive autophagy can also lead to cell death, making autophagy a double-edged sword in cancer27. The mechanism discovered in this study involving FDX1 activation of AMPK and subsequent inhibition of the mTOR pathway not only regulates the autophagy process in OC cells but also potentially influences the crosstalk between copper metabolism and autophagy.

In the field of oncology, the balance of copper ions has a significant impact on cellular function and pathological states28,29. Particularly in the complex tumor microenvironment of OC, the maintenance and regulation of copper ion balance become crucial30. Copper is an essential trace element involved in various biochemical processes, including energy production, antioxidant defense, and cell proliferation. In the context of cancer, both excess and deficiency of copper may influence the development and progression of tumors31. This study revealed a significant upregulation of the FDX1 gene in OC, closely associated with the regulation of copper ion levels. As a key regulatory factor in copper metabolism, FDX1 in OC may impact cancer cell survival and proliferation by modulating the availability and intracellular distribution of copper ions.

The relationship between FDX1 and copper ion balance appears particularly important in OC. Studies suggest that the upregulation of FDX1 may enhance cellular uptake and utilization of copper, promoting copper ion accumulation in cancer cells15. This increase in copper ions may stimulate a series of pro-carcinogenic activities, including promoting angiogenesis and maintaining the high proliferative state of cancer cells. However, this action of FDX1 may also trigger the cell’s autophagy mechanism as a defense mechanism to help clear excessive copper ions, thereby preventing their toxic effects32. Therefore, the dual role of FDX1 in copper metabolism reveals its complexity in OC development, not only as a regulator of copper ion balance but also as a potential target for cancer therapy. Furthermore, copper ions can trigger macrophage/autophagy, a lysosome-dependent degradation pathway that plays a dual role in regulating cell survival or death fate under various stressful conditions17. Currently, there is limited research on the molecular mechanisms of copper metabolism and autophagy crosstalk, and this study, identifying FDX1 as a crucial gene in regulating copper metabolism and autophagy crosstalk in OC cells, partially fills this gap.

Although this study made significant progress in revealing FDX1’s role in regulating autophagy in OC cells by activating the AMPK and inhibiting the mTOR pathway, there are still limitations that need to be addressed in future research. Firstly, this study primarily relied on in vitro cellular experiments and mouse models, which, while providing a foundation to understand FDX1’s role in OC, may not fully replicate the complexity and heterogeneity of human OC. Therefore, future studies should validate these findings in a broader range of clinical samples to enhance the clinical relevance of the research.

Furthermore, while we have observed a correlation between FDX1 expression and autophagy activity in OCcells, the regulatory mechanisms of autophagy are extremely complex, potentially involving multiple signaling pathways and molecules. This study primarily focuses on the AMPK and mTOR pathways, and future research should consider investigating other signaling pathways that FDX1 may impact to comprehensively understand its role in OC. Additionally, autophagy may have a dual role in tumor development, both promoting tumor cell survival and triggering cell death. Hence, further research on the specific effects of FDX1 on autophagy and how these effects manifest in different stages of OC is necessary.

In summary, the study of copper-induced cell death and its crosstalk with autophagy not only advances our understanding of the role of FDX1 in OC but also has the potential to drive the development of novel anticancer strategies. Although the current understanding of copper-induced cell death is in its early stages, FDX1, as a key regulator of this form of cell death, offers a potential intervention point. Future research needs to further explore the detailed mechanisms of FDX1, copper-induced cell death, and autophagy in OC and other types of cancers, as well as how to precisely utilize this pathway to optimize treatment strategies.

In conclusion, this study reveals a novel role of FDX1 in coordinating autophagy and copper ion balance during osteoclastogenesis. Specifically, FDX1 activates AMPK to inhibit the mTOR signaling pathway, promoting autophagy in osteoclast cells and ultimately facilitating the osteoclastogenesis process (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Diagram illustrating the molecular mechanism by which the copper-induced cell death-related gene FDX1 is involved in the progression of OC (Created with BioRender.com).

Methods

Data sources

We obtained RNA-seq data and corresponding clinical information for 427 OC samples from the TCGA database (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/). The clinical information included tumor grade (Grade 1–4) and p53 mutation status (p53-Mutant and p53-NonMutant). Due to the lack of normal tissue sample data in TCGA, we also downloaded 88 normal ovarian tissue sample data from the GTEx database (https://www.gtexportal.org/home/datasets) for comparison with OC samples. Moreover, we retrieved proteomic data for FDX1 and its clinical information (PDC000110) from The National Cancer Institute’s Clinical Proteomic Tumor Analysis Consortium (CPTAC), which included 25 normal ovarian tissue samples and 100 tumor tissue samples. The clinical information for patients comprised tumor grade (Grade 1–4) and p53 mutation status (Normal, p53/Rb-related Pathway-altered, and Others)33. We analyzed the expression of FDX1 in various OC cell lines using the Human Protein Atlas (HPA) database (https://www.proteinatlas.org/). Since these data were obtained from publicly available databases, ethical approval from an institutional review board was not required.

Genetic variation analysis

To investigate the relationship between FDX1 expression and genetic variations, we analyzed the genetic variation frequency and major mutation types of FDX1 in all OC samples selected from the cBioPortal database (http://www.cbioportal.org)34.

Tumor mutation burden (TMB) refers to the number of somatic mutations in a tumor genome after excluding germline mutations. TMB calculation includes point mutations and insertion/deletion mutations. This study further explored the correlation between FDX1 expression and TMB in OC samples35.

Drug sensitivity analysis

The CellMiner database (https://discover.nci.nih.gov/cellminer/) is a network tool that integrates genomic and pharmacological information. Transcripts and drug response data of the NCI-60 cell lines were downloaded from the CellMiner database. The correlation between FDX1 gene expression and drug sensitivity was calculated using Pearson correlation analysis. A P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

The IC50 values of drugs in the Cancer Genome Project (GDSC) (https://www.cancerrxgene.org) were computed using the R package “oncoPredict”36,37.

Identification and functional enrichment analysis of FDX1-related genes

Based on the TCGA dataset, we used R software packages such as ggpubr to identify FDX1 co-expressed genes in OC tissue, with a filtering criterion of |r | > 0.3 and P < 0.05. Additionally, a scatter plot showing the expression correlation between FDX1 and autophagy-related genes (VMA21, ATG5, ATG3, ATG4A, ATG4C) was created38.

Searching “FDX1” in the STRING database (https://cn.string-db.org/cgi/input?sessionId=b92G0n5gdTKt&input_page_show_search=on), we retrieved proteins that interact most closely with FDX1 protein39.

The “ClusterProfiler” package in R40 was utilized for GO functional analysis of FDX1-related genes, including biological processes (BP), cellular components (CC), molecular functions (MF), and KEGG enrichment analysis, with significance set at P < 0.05.

By stratifying TCGA OC samples into high and low FDX1 expression groups based on the median FDX1 expression, we used GSEA to reveal pathway differences enriched between high and low FDX1 expression groups. The “c2.cp.kegg.v2023.1.Hs.symbols” from MSigDB served as the reference gene set, with NOM p-val < 0.05 considered significantly enriched41.

Clinical sample collection

We collected 20 ovarian cancer (OC) tissue samples and 3 normal ovarian tissue samples from the Pathology Department of Shengjing Hospital Affiliated to China Medical University. All OC samples were obtained from patients undergoing surgical treatment, confirmed pathologically, and without prior chemotherapy or radiotherapy. Normal ovarian tissue samples were derived from patients undergoing hysterectomy for benign gynecological conditions (without ovarian lesions). All samples were processed within 30 min post-surgery and preserved either at −80 °C for long-term storage or fixed in 10% neutral formalin for paraffin embedding. Patient selection followed strict inclusion criteria, including a confirmed diagnosis of OC, while excluding those with immune system diseases, infectious diseases (e.g., HIV, HBV, or HCV), or other concurrent malignancies42. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of Shengjing Hospital, China Medical University. All participants provided written informed consent prior to their inclusion in the study.

Detection of copper ions

To detect the concentration of copper ions in tissue or cell samples, the copper content detection kit (MAK127, Sigma-Aldrich, USA) was purchased and utilized following the manufacturer’s instructions. The absorbance of the samples was measured at 359 nm using a microplate reader (Infinite200, Tecan, Beijing, China), and quantification was performed using a standard curve43.

Immunohistochemical staining

Tissue samples from clinical or murine groups were embedded in paraffin, cut into slices, and baked at 60 °C for 20 min. Subsequently, the slices were placed in xylene, followed by two changes of xylene with each immersion lasting 15 min. After immersion in absolute alcohol for 5 min, the slices were placed in fresh absolute alcohol for an additional 5 min. The slices were then hydrated in 95% and 70% alcohol for 10 min each. 3% H2O2 was added dropwise to each slice and left to immerse at room temperature for 10 min to block endogenous peroxidases. Citrate buffer was added, and the samples were microwaved for 3 min, followed by the addition of antigen retrieval solution and incubation at room temperature for 10 min. Subsequently, the samples were washed in PBS three times. Normal goat serum blocking solution (E510009, Shanghai Sangon Biotech) was applied at room temperature for 20 min, and then the primary antibodies FDX1 (HPA041630, 1:5000, Sigma-Aldrich, USA), p62 (23214, 1:200, CST), LC3B (83506, 1:200, CST) and Ki67 (ab16667, 1:200, Abcam, UK) were added separately and incubated overnight at 4 °C. After washing three times with PBS, the samples were incubated with goat anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody (ab6721, 1:1000, Abcam, UK) for 30 min, followed by PBS washing. The DAB chromogenic reagent kit (DAB-M, Sigma-Aldrich, USA) was used by adding one drop each of color developers A, B, and C to the specimens, with a 6-minute color development time. Subsequently, the slices were stained with hematoxylin for 30 s, dehydrated in 70%, 80%, 90%, 95% ethanol, and then absolute ethanol for 2 min each. Finally, the slices were immersed twice in xylene for 5 min each and sealed with neutral resin. The slices were observed under a brightfield microscope (BX63, Olympus, Japan). The experiment was repeated three times. PBS was used for incubation instead of the primary antibody as a negative control. Five immunohistochemical images from different fields of view were selected for quantitative analysis. The number of cells with brown staining signals in the cytoplasm was counted as positively stained cells in each field of view. The total number of cells in each field of view was also counted, and the percentage of positive cells was calculated as follows: Positive cell percentage = number of cells with brown staining / total number of cells × 100%44.

Co-localization observed by immunofluorescence microscopy

Tissues were stained with 400 nM MitoTracker Deep Red (M22426, Invitrogen, USA) at 37 °C for 30 min. Following staining, cells were collected in a 1.5 mL centrifuge tube, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (60536ES60, Yeasen Biotechnology [Shanghai] Co., Ltd., China), permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 (P0096, Beyotime Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China), blocked in PBS containing 1% BSA, and then rotated overnight at 4 °C with a 1:100 dilution of anti-FDX1 antibody (ab109312, abcam, UK) in blocking buffer. After washing, cells were rotated in a blocking buffer and incubated with a 1:100 dilution of Alexa Fluor™ 488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibody (1:100, A-11008, Invitrogen, USA). Subsequently, cells were stained with 300 nM 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (D1306, Invitrogen, USA) in PBS for nuclear staining. Finally, cells were centrifuged at 800 g for 5 min, mounted with ProLong™ Gold anti-fade reagent (P36930, Invitrogen, USA), and cover-slipped. Macrophages in a 12-well plate were stained following the aforementioned steps after MitoTracker staining and imaged under LSM 700 with a 63×/1.4 NA objective lens (Carl Zeiss Microscopy, Germany)45.

In vitro cell culture

The human OC cell lines SK-OV-3 (ML097240, Shanghai Enzyme-linked Biotechnology, China) and CAOV-3 (ML096045, Shanghai Enzyme-linked Biotechnology, China) were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium (R4130, Sigma-Aldrich, USA) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (F8687, Sigma-Aldrich, USA). The cells were cultured at 37 °C in a humidified CO2 incubator (Heracell™ Vios 160i CR CO2 incubator, 51033770, Thermo Scientific, USA) with 5% CO2. Passage was performed when the cells reached 80%-90% confluency.

HEK293T cells were purchased from ATCC (CRL-3216) and cultured in DMEM medium (11965092, Gibco, USA) containing 10% FBS, 10 μg/mL streptomycin, and 100 U/mL penicillin. The cells were maintained at 37 °C in a humidified CO2 incubator with 5% CO2. Passage was conducted when the cells reached 80%-90% confluency46. To ensure the reliability and reproducibility of experimental results, all cell lines were subjected to stringent authentication and mycoplasma testing.

Construction of silencing and overexpression lentiviral vectors

Potential short hairpin RNA (shRNA) target sequences for FDX1 were analyzed based on GenBank mouse cDNA sequences. Three target sequences targeting FDX1 were designed, with a sequence lacking interference serving as the negative control (sh-NC). The primer sequences for each are listed in Supplementary Table 1. The oligonucleotides were synthesized by Sigma-Aldrich and utilized in constructing the lentivirus packaging system with the lentiviral interference vector LV-1 (pGLVU6/GFP) (C06001, Sigma-Aldrich, China).

The packaging virus and desired vectors were co-transfected into human kidney epithelial cell line HEK293T using Lipofectamine 2000 (11668030, Thermo Fisher, USA) with a cell confluency of 80–90%. After 48 h of cell culture, the supernatant, which contained viral particles post-filtration and centrifugation, was collected. The virus was harvested during the logarithmic growth phase, and the viral titer was determined. The lentivirus for overexpressing FDX1 was constructed and packaged by Genomeditech, and the lentiviral gene overexpression vector was LV-PDGFRA47.

The cell groups were divided as follows: (1) sh-NC group (transfected with silencing negative control lentivirus), sh-FDX1 group (transfected with FDX1 silencing lentivirus), oe-NC group (transfected with overexpression negative control lentivirus), oe-FDX1 group (transfected with FDX1 overexpression lentivirus); (2) oe-NC + DMSO group (transfected with overexpression negative control lentivirus, treated with an equal volume of DMSO), oe-FDX1 + DMSO group (transfected with FDX1 overexpression lentivirus, treated with an equal volume of DMSO), oe-FDX1+Compound C group (transfected with FDX1 overexpression lentivirus, treated with Compound C). The cells in each group were treated with 10 μM Compound C for 18 h. Compound C (catalog number: HY-13418A) was purchased from Med Chem Express48.

Furthermore, for the detection of copper-induced cell death, different concentrations of the copper ion carrier Elesclomol-Cu (ratio=1:1) were applied to the above cell groups for 72 h32. Subsequently, the cell viability was assessed using the CCK-8 assay, cell migration was evaluated using the scratch assay, and cell invasion was assessed using the Transwell assay. Elesclomol (catalog number: HY-12040) was purchased from Med Chem Express.

RT-qPCR

Total RNA was extracted using the Trizol reagent kit (T9424, Sigma-Aldrich, USA). RNA quality and concentration were assessed using UV-visible spectrophotometry (ND-1000, Nanodrop, Thermo Fisher, USA). Reverse transcription was carried out according to the PrimeScript™ RT-qPCR kit (RR086A, TaKaRa, Mountain View, CA, USA). Real-time quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) was conducted using SYBR Green PCR Master Mix reagents (4364344, Applied Biosystems, USA) and the ABI PRISM 7500 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems, USA). GAPDH was used as the reference gene for mRNA normalization. The primers for amplification were designed by Shanghai General Biotech Co., Ltd. Primer sequences can be found in Supplementary Table 2. The fold change in gene expression between experimental and control groups was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method with the formula: ΔΔCT = ΔCtexperimental - ΔCtcontrol, where ΔCt = Cttarget gene - Ctreference gene49.

Western blot

To initiate the Western blot analysis, tissues or cells were collected and lysed using an enhanced RIPA lysis buffer containing a protease inhibitor (P0013B, Beyotime, Shanghai, China). The protein concentration was determined using a BCA protein quantification kit (P0012, Beyotime, Shanghai, China). Subsequently, the proteins were separated on a 10% SDS-PAGE gel, transferred to a PVDF membrane, and blocked with 5% BSA at room temperature for 2 h to prevent nonspecific binding. Following blocking, the membrane was incubated at room temperature for 1 h with specific primary antibodies diluted accordingly (rabbit anti-human; detailed information in Supplementary Table 3), then washed and further incubated at room temperature for 1 h with an HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (ab6721, 1:2000, Abcam, UK). Pierce™ ECL Western blot substrate (32209, Thermo Scientific™, Germany) A and B solutions were mixed in equal amounts and applied onto the membrane, which was subsequently exposed and imaged using a gel documentation system (Bio-Rad, USA). Image J analysis software was utilized to quantify the band intensities in the Western blot images, with GAPDH as the internal reference. Each experiment was replicated three times50 All the Full, uncropped images can be found at Supplementary Fig. 7–45.

Mitochondrial membrane potential detection

Cells were seeded into a 6-well culture plate using a JC-1 mitochondrial membrane potential assay kit (40706ES60, Yeasen Biotechnology (Shanghai) Co., Ltd., China). One milliliter of JC-1 staining working solution was added to each well and thoroughly mixed. The cells were then incubated at 37 °C in a cell culture incubator for 20 min. To serve as a positive control, CCCP (50 mM) provided in the assay kit was added to the cell culture medium at a dilution of 1:1000 to achieve a final concentration of 50 μM, and the cells were treated for 20 min. After the incubation at 37 °C, the supernatant was removed, and the cells were washed twice with JC-1 staining buffer (1×). Subsequently, 2 mL of cell culture medium containing serum and phenol red was added. The fluorescence of JC-1 monomers was observed under a fluorescence microscope or confocal laser scanning microscope, with the excitation light set at 490 nm and emission light set at 530 nm51.

Observation of mitochondrial morphology with transmission electron microscopy

The cell samples were first fixed overnight in a 2.5% paraformaldehyde solution at 4 °C. Subsequently, the samples were fixed in a 1% osmium tetroxide solution for 1–2 h. Dehydration of the samples was carried out in graded ethanol solutions of 50%, 70%, 80%, 90%, and 95% at room temperature, followed by treatment with pure acetone. The samples were then infiltrated overnight in pure embedding resin and further polymerized overnight at 70 °C to complete embedding. Thin sections with a thickness of 70–90 nm were obtained by cutting the samples in a Reichert ultramicrotome. These sections were stained with lead citrate solution and 50% ethanol-saturated uranyl acetate solution for 15 min each. Finally, the sections were observed under a transmission electron microscope52.

Detection of cell viability using CCK-8 assay

After dissociating cells in each group, they were resuspended, adjusting the cell concentration to 1 × 105 cells/mL. Subsequently, 100 μL of cell suspension was seeded into a 96-well plate for routine culture. Once the cells adhered to the plate, drugs were added, and cells were cultured overnight. On the first and fourth days post-culturing, cell viability was assessed according to the instructions of the CCK-8 kit (C0041, Beyotime Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China). For each assessment, 10 μL of CCK-8 detection solution was added to the wells and incubated in a cell culture incubator for 4 h. Following this, the absorbance at 450 nm was measured using a microplate reader to calculate the cell viability53.

Experiment to detect the clonogenic ability of cells

For plate clone experiments, cells in the exponential growth phase were harvested using standard subculture methods to obtain a cell suspension with over 95% single-cell viability. The cells were counted and diluted to an appropriate concentration with a culture medium. Subsequently, 5 mL of the cell suspension containing 100 cells per plate was seeded into culture dishes (60 mm diameter) and gently rocked in a crosswise motion to ensure uniform cell distribution. The culture dishes were then incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 2–3 weeks. Upon visible colony formation in the dishes, the incubation was stopped, and the culture medium was discarded. The dishes were carefully rinsed twice with PBS and air-dried. The colonies were fixed with methanol for 15 min, followed by air-drying after methanol removal. Giemsa staining was carried out for 10 min, followed by slow rinsing with running water to remove excess stain and air-drying. Colony numbers containing more than 10 cells were counted either visually or under a microscope (low magnification). The clonogenic efficiency was calculated using the formula: Clonogenic efficiency = (Number of colonies/Number of seeded cells) × 100%54.

Scratch test to evaluate cell migration ability

Using a marker pen, draw a uniform horizontal line behind each well of a 6-well plate, with each line spaced 1 cm apart and crossing through the well. Inoculate approximately 5 × 105 cells into each well and culture using standard protocols until confluence reaches 100%. Subsequently, perpendicular to the cell plane, scratches are created across the cell layer along the lines on the back of the plate using a pipette tip. After scratching, rinse three times with sterile PBS to remove non-adherent cells, ensuring clear visibility of the gaps left by the scratches. Replace with fresh serum-free culture medium and incubate the cells in a 37 °C, 5% CO2 cell culture incubator. After 24 h, observe and measure the width of the scratches under a microscope, capturing images for documentation. Analyze the migration rate using Image J software55.

Transwell assay for cell invasion

Cell invasion was assessed using Transwell chambers with 8 µm-pore membranes (product #3391, Corning, USA). For the invasion assay, Matrigel (product #354277, BD Biosciences, USA) was added to each well according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Subsequently, cells from each group (2 × 105 cells) were placed in a serum-free culture medium and added to the upper chamber of the Transwells. Following a 24-hour incubation period at 37 °C, the translocated cells were fixed with 0.5% crystal violet at room temperature for 20 min. Subsequently, under a Nikon Eclipse Ci optical microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan), five areas (upper, lower, central, left, and right, one each) were observed and photographed. Five fields were randomly selected for counting the purple-stained positive cells, and the results were recorded56.

In vivo animal experimentation

CAOV-3 cells (2 × 106) were subcutaneously injected into 4-week-old female BALB/c nude mice (Cat. NO. SM-014, purchased from Shanghai Model Biotech Co., Ltd., housed in an SPF facility) to establish an OC subcutaneous transplant model57. All animal experiments were approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Shengjing Hospital of China Medical University (Approval No. CMUXN2022719), and were conducted in strict accordance with the guidelines of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, as well as institutional and national regulations for animal welfare. All efforts were made to minimize animal suffering, and humane endpoints were used throughout the study.

The CAOV-3 cells were labeled with a near-infrared fluorescent probe DiR (MX4005, Maokang Biotech, Shanghai, China) at a labeling rate of 90%. Subsequently, the bioluminescent signals of CAOV-3 cells were analyzed using the CRi Maestro in vivo imaging system (Cambridge Research & Instrumentation, Massachusetts, USA).

After 28 days of CAOV-3 cell injection, mice were anesthetized and euthanized by cervical dislocation, and tumor volume V was calculated using the formula V = (length × width2)/2. The tumor tissues were then isolated and processed for further experimental analysis using FFPE (Formalin-Fixed Paraffin-Embedded) or rapid freezing.

Animal groups included the oe-NC + DMSO group (injection of negative control CAOV-3 cells, intravenous injection of equivalent volume of DMSO), oe-FDX1 + DMSO group (injection of CAOV-3 cells overexpressing FDX1, intravenous injection of equivalent volume of DMSO), and oe-FDX1+Compound C group (injection of CAOV-3 cells overexpressing FDX1, intravenous injection of Compound C). Compound C (25 mg/kg) was injected intravenously 30 min prior to modeling58.

Statistical analysis

All experiments were conducted independently at least three times, and the data were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Differences between groups were assessed using an independent samples t-test or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). In cases where the ANOVA revealed significant differences, we proceeded with Tukey’s Honestly Significant Difference (HSD) post-hoc test to compare differences among groups. For non-normally distributed or inhomogeneous variance data, the Mann-Whitney U test or Kruskal-Wallis H test was employed. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 8.0. A significance level of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant59.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Shengjing 345 Talent Project.

Author contributions

C.L. and S.W. designed and performed the experiments. J.Z. contributed to data analysis and interpretation. H.Q. assisted with in vivo studies and histological assessments. H.D. supervised the project, acquired funding, and revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to manuscript writing, reviewed the final version, and approved it for submission.

Data availability

We confirm that all datasets used in our study were obtained from publicly accessible repositories and have been appropriately cited within the manuscript. Details are as follows: 1. RNA-seq and clinical data for 427 ovarian cancer samples were downloaded from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/), including tumor grade and p53 mutation status. Since TCGA lacks normal ovarian tissue samples, we additionally downloaded 88 normal ovarian tissue RNA-seq samples from the Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) database (https://www.gtexportal.org/home/datasets) for comparison. 2. Proteomic data for FDX1 and associated clinical information (25 normal tissues and 100 tumor tissues) were obtained from the Clinical Proteomic Tumor Analysis Consortium (CPTAC), dataset ID: PDC000110, including tumor grade and p53 pathway alteration status. 3. Protein expression across ovarian cancer cell lines was analyzed using data from the Human Protein Atlas (HPA) (https://www.proteinatlas.org/). 4. FDX1 genetic alterations were examined using the cBioPortal platform (http://www.cbioportal.org), and their relationship with tumor mutation burden (TMB) was also assessed. As all data were retrieved from open-access public databases, no ethical approval or patient consent was required for this study. The description of data availability is mentioned at the beginning of the Materials and Methods section.

Code availability

Custom R scripts were used for processing and analyzing the RNA-seq data, clinical data integration, mutation analysis, drug sensitivity correlation, and functional enrichment analyses (GO, KEGG, and GSEA). These scripts were developed based on standard pipelines using R (version 4.2.1) and Bioconductor packages, including ggpubr (v0.6.0), clusterProfiler (v4.6.2), and oncoPredict (v0.2). Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) was performed using the MSigDB reference gene set “c2.cp.kegg.v2023.1.Hs.symbols”. Custom parameters such as |r | > 0.3 and P < 0.05 for co-expression filtering were applied. The code is available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author, as there are currently no public repositories hosting these scripts.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41698-025-00994-7.

References

- 1.Kocarnik, J. M. et al. Cancer incidence, mortality, years of life lost, years lived with disability, and disability-adjusted life years for 29 Cancer Groups From 2010 to 2019, American Medical Association (AMA), (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Weiland, F. et al. Ovarian Blood Sampling Identifies Junction Plakoglobin as a Novel Biomarker of Early Ovarian Cancer, Frontiers Media SA, (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Penny, S. M. Ovarian Cancer: An Overview. Radio. Technol.91, 561–575 (2020). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stewart, C., Ralyea, C. & Lockwood, S. Ovarian Cancer: An Integrated Review, Elsevier BV, (2019). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Morand, S., Devanaboyina M., Staats H., Stanbery L. & Nemunaitis J. Ovarian Cancer Immunotherapy and Personalized Medicine, MDPI AG, (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Wu, Y. SNHG11: A New Budding Star in Tumors and Inflammatory Diseases, Bentham Science Publishers Ltd., (2023). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Tsvetkov, P. et al. Copper induces cell death by targeting lipoylated TCA cycle proteins, American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS), (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Chakraborty, J., Pakrashi, S., Sarbajna, A., Dutta, M. & Bandyopadhyay J. Quercetin Attenuates Copper-Induced Apoptotic Cell Death and Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress in SH-SY5Y Cells by Autophagic Modulation, Springer Science and Business Media LLC, (2022). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Wang, T. et al.Cuproptosis-related gene FDX1 expression correlates with the prognosis and tumor immune microenvironment in clear cell renal cell carcinoma, Frontiers Media SA, (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Jiang, A. et al. Copper Death Inducer, FDX1, as a Prognostic Biomarker Reshaping Tumor Immunity in Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma, MDPI AG, (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Liu, H. Pan-cancer profiles of the cuproptosis gene set. Am. J. Cancer Res.12, 4074–4081 (2022). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Takahashi, R., Kamizaki, K., Yamanaka, K., Terai, Y. & Minami, Y. Expression of Ferredoxin1 in cisplatin‑resistant ovarian cancer cells confers their resistance against ferroptosis induced by cisplatin, Spandidos Publications, (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Hussain, S. et al. The Roles of Stroma-Derived Chemokine in Different Stages of Cancer Metastases, Frontiers Media SA, (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Cocco, S. et al. Inhibition of autophagy by chloroquine prevents resistance to PI3K/AKT inhibitors and potentiates their antitumor effect in combination with paclitaxel in triple negative breast cancer models, Springer Science and Business Media LLC, (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Zulkifli, M. et al. FDX1-dependent and independent mechanisms of elesclomol-mediated intracellular copper delivery, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Jing, Z. et al. NCAPD2 inhibits autophagy by regulating Ca2+/CAMKK2/AMPK/mTORC1 pathway and PARP-1/SIRT1 axis to promote colorectal cancer, Elsevier BV, (2021). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Xue, Q. et al. Copper metabolism in cell death and autophagy, Informa UK Limited, (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Liao, J. et al. Copper induces energy metabolic dysfunction and AMPK-mTOR pathway-mediated autophagy in kidney of broiler chickens, Elsevier BV, (2020). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Dreishpoon, M. B. et al. FDX1 regulates cellular protein lipoylation through direct binding to LIAS, Elsevier BV, (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Lu, J. et al. FDX1 enhances endometriosis cell cuproptosis via G6PD-mediated redox homeostasis, Springer Science and Business Media LLC, (2023). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Ashraf, R. & Kumar, S. Mfn2-mediated mitochondrial fusion promotes autophagy and suppresses ovarian cancer progression by reducing ROS through AMPK/mTOR/ERK signaling, Springer Science and Business Media LLC, (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Hsu, C.-C., Peng, D., Cai, Z. & Lin, H.-K. AMPK signaling and its targeting in cancer progression and treatment, Elsevier BV, (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Carling, D. AMPK signalling in health and disease, Elsevier BV, (2017). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Klionsky, D. J. et al. Autophagy in major human diseases, Springer Science and Business Media LLC, (2021).

- 25.Debnath, J., Gammoh, N. & Ryan, K. M. Autophagy and autophagy-related pathways in cancer, Springer Science and Business Media LLC, (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Levy, J. M. M., Towers, C. G. & Thorburn, A. Targeting autophagy in cancer, Springer Science and Business Media LLC, (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Liu, S., Yao, S., Yang, H., Liu, S. & Wang Y. Autophagy: Regulator of cell death, Springer Science and Business Media LLC, (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Ge, E. J. et al. Connecting copper and cancer: from transition metal signalling to metalloplasia, Springer Science and Business Media LLC, (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Guan, D., Zhao, L., Shi, X., Ma, X. & Chen, Z. Copper in cancer: From pathogenesis to therapy, Elsevier BV, (2023). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Guo, J., Sun, Y. & Liu, G. The mechanism of copper transporters in ovarian cancer cells and the prospect of cuproptosis, Elsevier BV, (2023). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Li, Y. Copper homeostasis: Emerging target for cancer treatment, Wiley, (2020). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Sun, L. et al. Lactylation of METTL16 promotes cuproptosis via m6A-modification on FDX1 mRNA in gastric cancer, Springer Science and Business Media LLC, (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Xu, J. et al. Multi-omics pan-cancer study of cuproptosis core gene FDX1 and its role in kidney renal clear cell carcinoma, Frontiers Media SA, (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Xu, H. et al. MRPL15 is a novel prognostic biomarker and therapeutic target for epithelial ovarian cancer, Wiley, (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Chalmers, Z. R. et al. Analysis of 100,000 human cancer genomes reveals the landscape of tumor mutational burden, Springer Science and Business Media LLC, (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Xiaowei, W., Tong, L., Yanjun, Q. & Lili, F. PTH2R is related to cell proliferation and migration in ovarian cancer: a multi-omics analysis of bioinformatics and experiments, Springer Science and Business Media LLC, (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Li, H. et al. A prognostic signature consisting of metabolism-related genes and SLC17A4 serves as a potential biomarker of immunotherapeutic prediction in prostate cancer, Frontiers Media SA, (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Fang, Y., Huang, S., Han, L., Wang, S. & Xiong, B. Comprehensive Analysis of Peritoneal Metastasis Sequencing Data to Identify LINC00924 as a Prognostic Biomarker in Gastric Cancer, Informa UK Limited, (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Szklarczyk, D. et al. The STRING database in 2023: protein–protein association networks and functional enrichment analyses for any sequenced genome of interest, Oxford University Press (OUP), (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Yu, G., Wang, L.-G., Han, Y. & He, Q.-Y. clusterProfiler: an R Package for Comparing Biological Themes Among Gene Clusters, Mary Ann Liebert Inc., (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.Du, Y. et al. The Epithelial to Mesenchymal Transition Related Gene Calumenin Is an Adverse Prognostic Factor of Bladder Cancer Correlated With Tumor Microenvironment Remodeling, Gene Mutation, and Ferroptosis, Frontiers Media SA, (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Vankerckhoven, A. et al. Opposite Macrophage Polarization in Different Subsets of Ovarian Cancer: Observation from a Pilot Study, MDPI AG, (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Xu, X. et al. Integrative analysis revealed that distinct cuprotosis patterns reshaped tumor microenvironment and responses to immunotherapy of colorectal cancer, Frontiers Media SA, (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 44.Wang, X. & Wu Y. Protective effects of autophagy inhibitor 3-methyladenine on ischemia–reperfusion-induced retinal injury, Springer Science and Business Media LLC, (2020). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 45.Tsai M.-L. et al. IL-25 Induced ROS-Mediated M2 Macrophage Polarization via AMPK-Associated Mitophagy, MDPI AG, (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46.Lu, T. et al. Enhanced osteogenic and selective antibacterial activities on micro-/nano-structured carbon fiber reinforced polyetheretherketone, Royal Society of Chemistry (RSC), (2016). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 47.Zhang, Z. et al. Activin a promotes myofibroblast differentiation of endometrial mesenchymal stem cells via STAT3-dependent Smad/CTGF pathway, Springer Science and Business Media LLC, (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Kim, Y. M. et al. Compound C independent of AMPK inhibits ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 expression in inflammatory stimulants-activated endothelial cells in vitro and in vivo, Elsevier BV, (2011). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 49.Cao, D., Pi, J., Shan, Y., Tang, Y. & Zhou, P. Anti‑inflammatory effect of Resolvin D1 on LPS‑treated MG‑63 cells, Spandidos Publications, (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 50.Zhu, Y. et al. LDHA deficiency inhibits trophoblast proliferation via the PI3K/AKT/FOXO1/CyclinD1 signaling pathway in unexplained recurrent spontaneous abortion, Wiley, (2022). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 51.Su, L. et al. Pannexin 1 mediates ferroptosis that contributes to renal ischemia/reperfusion injury, Elsevier BV, (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 52.Sui, M. et al. CIRBP promotes ferroptosis by interacting with ELAVL1 and activating ferritinophagy during renal ischaemia-reperfusion injury, Wiley, (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 53.Xiao, X. et al. HSP90AA1-mediated autophagy promotes drug resistance in osteosarcoma, Springer Science and Business Media LLC, (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 54.Geng, X.-F., Fang, M., Liu, S.-P. & Li, Y. Quantum dot-based molecular imaging of cancer cell growth using a clone formation assay, Spandidos Publications, (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 55.Chen, X. et al. FGF21 promotes migration and differentiation of epidermal cells during wound healing via SIRT1-dependent autophagy, Wiley, (2021). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 56.Ding, W., Shi, Y. & Zhang, H. Circular RNA circNEURL4 inhibits cell proliferation and invasion of papillary thyroid carcinoma by sponging miR-1278 and regulating LATS1 expression. Am. J. Transl. Res13, 5911–5927 (2021). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhang, B., Ma, X., Li, Y., Li, S. & Cheng, J. Pleuromutilin Inhibits Proliferation and Migration of A2780 and Caov-3 Ovarian Carcinoma Cells and Growth of Mouse A2780 Tumor Xenografts by Down-Regulation of pFAK2, International Scientific Information, Inc., (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Retracted]

- 58.Yu, P. B. et al. Dorsomorphin inhibits BMP signals required for embryogenesis and iron metabolism, Springer Science and Business Media LLC, (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 59.Qu Y. et al. Monocytic myeloid-derived suppressive cells mitigate over-adipogenesis of bone marrow microenvironment in aplastic anemia by inhibiting CD8+ T cells, Springer Science and Business Media LLC, (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

We confirm that all datasets used in our study were obtained from publicly accessible repositories and have been appropriately cited within the manuscript. Details are as follows: 1. RNA-seq and clinical data for 427 ovarian cancer samples were downloaded from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/), including tumor grade and p53 mutation status. Since TCGA lacks normal ovarian tissue samples, we additionally downloaded 88 normal ovarian tissue RNA-seq samples from the Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) database (https://www.gtexportal.org/home/datasets) for comparison. 2. Proteomic data for FDX1 and associated clinical information (25 normal tissues and 100 tumor tissues) were obtained from the Clinical Proteomic Tumor Analysis Consortium (CPTAC), dataset ID: PDC000110, including tumor grade and p53 pathway alteration status. 3. Protein expression across ovarian cancer cell lines was analyzed using data from the Human Protein Atlas (HPA) (https://www.proteinatlas.org/). 4. FDX1 genetic alterations were examined using the cBioPortal platform (http://www.cbioportal.org), and their relationship with tumor mutation burden (TMB) was also assessed. As all data were retrieved from open-access public databases, no ethical approval or patient consent was required for this study. The description of data availability is mentioned at the beginning of the Materials and Methods section.

Custom R scripts were used for processing and analyzing the RNA-seq data, clinical data integration, mutation analysis, drug sensitivity correlation, and functional enrichment analyses (GO, KEGG, and GSEA). These scripts were developed based on standard pipelines using R (version 4.2.1) and Bioconductor packages, including ggpubr (v0.6.0), clusterProfiler (v4.6.2), and oncoPredict (v0.2). Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) was performed using the MSigDB reference gene set “c2.cp.kegg.v2023.1.Hs.symbols”. Custom parameters such as |r | > 0.3 and P < 0.05 for co-expression filtering were applied. The code is available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author, as there are currently no public repositories hosting these scripts.