Abstract

Background

Peptides radiolabeled with fluorine-18 are frequently synthesized using prosthetic groups. Among them, activated esters of 6-[18F]fluoronicotinic acid ([18F]FNA) have been prepared and successfully employed for 18F-labeling of diverse biomolecules, including peptides. The utility of [18F]FNA as a prosthetic compound has been demonstrated in both preclinical and clinical settings, including radiopharmaceuticals targeting prostate-specific membrane antigen and poly(ADP ribose) polymerase inhibitors. This study aims to evaluate a [18F]FNA-conjugated nonapeptide, [18F]FNA-N-CooP, for positron emission tomography imaging of intracranial BT12 glioblastoma xenografts in a mouse model. Additionally, this study highlights the importance of including control experiments with prosthetic compound alone when it constitutes a major radiometabolite.

Results

[18F]FNA-N-CooP successfully delineated intracranial glioblastoma xenografts yielding a standardized uptake value of 0.21 ± 0.03 (n = 4) and a tumor-to-brain ratio of 1.84 ± 0.29. Ex vivo autoradiography of tumor tissue showed a partial co-localization between radioactivity uptake and the target fatty acid binding protein 3 expression. However, in vivo instability of [18F]FNA-N-CooP was observed, with [18F]FNA identified as a major radiometabolite. Notably, control studies using [18F]FNA alone also visualized tumors, producing a standardized uptake value of 0.90 ± 0.10 (n = 4) and a tumor-to-brain ratio of 1.51 ± 0.08.

Conclusions

Both [18F]FNA-N-CooP and [18F]FNA enabled PET visualization of human glioblastoma in the mouse model. However, the prominent presence of [18F]FNA as radiometabolite complicates the interpretation of [18F]FNA-N-CooP PET data, suggesting that the observed radioactivity uptake may primarily originate from [18F]FNA and other radiometabolites. Enhancing peptide stability is essential for improving imaging specificity. This study underscores the critical need to assess the imaging contributions of prosthetic groups when they function as significant radiometabolites.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s41181-025-00368-1.

Keywords: Fluorine-18, 6-[18F]fluoronicotinic acid, Peptide radiolabeling, PET, Prosthetic group

Background

18F-Radiolabeling of biomolecules (e.g. peptides and oligonucleotides) is often performed with indirect 18F-fluorination utilizing prosthetic groups, where direct 18F-fluorination is not feasible or practical for the particular biomolecules (Bispo et al. 2022). Thus far, the selection of prosthetic groups is mainly empirical instead of rational in design. In vivo stability, suitability of conjugation chemistry, and feasibility for automated production are among the key issues to consider when choosing prosthetic groups (Li et al. 2012, 2014). 6-[18F]fluoronicotinic acid ([18F]FNA, Fig. 1) has gained attention to be used as a prosthetic group since its publication in 2010 (Olberg et al. 2010), as it is convenient to produce (Davis et al. 2019) and stable in vivo (Dillemuth et al. 2025). Additionally, the [18F]FNA-labeling moiety is relatively small in size, which is anticipated to have little influence on the biological properties of larger biomolecules being labeled. [18F]FNA has been conjugated to several kinds of molecules including peptides (Olberg et al. 2010; Dillemuth et al. 2024a), small organic compounds (Cardinale et al. 2017; Giesel et al. 2017; Keam 2021), and antibody fragments (Zhou et al. 2021). Among them, the radiopharmaceuticals 18F-PSMA-1007 and Pylarify have entered into clinical use for the diagnosis of prostate cancer with positron emission tomography (PET) with both of them being agents to target prostate-specific membrane antigen (Giesel et al. 2017; Keam 2021). In addition, promising results have been obtained from preclinical evaluation of the [18F]FNA-conjugated inhibitor of poly(ADP ribose) polymerase (PARP) enzymes (Stotz et al. 2022). The use of [18F]FNA as a prosthetic group is primarily based on N-acylation reaction of a biomolecule with activated esters of [18F]FNA (Olberg et al. 2010) and we have recently observed that [18F]FNA 4-nitrophenyl ester can acylate the thiol group with high chemoselectivity (Dillemuth et al. 2024a). In addition to [18F]FNA, a structurally similar compound, 4-[18F]fluorobenzoic acid ([18F]FB, Fig. 1), is also a useful prosthetic group for clinical PET applications (Gent et al. 2013). In typical cases, [18F]FB is conjugated to biomolecules via the activated ester N-succinimidyl 4-[18F]fluorobenzoate ([18F]SFB). Compared to the one-step radiosynthesis of [18F]FNA esters, the preparation of [18F]SFB needs three steps of chemical transformation requiring a more complicated and time-consuming process for radiopharmaceutical production. [18F]SFB is an earlier generation of prosthetic group than [18F]FNA esters and the radiolabeling techniques of [18F]SFB keep on evolving. In a recent study, [18F]SFB has been successfully produced in an automated manner with the commercially available radiosynthesis device, Trasis AllInOne (Dierick et al. 2024). The improved synthesis methods and techniques may stimulate increased use of [18F]SFB for radiolabeling of biomolecules.

Fig. 1.

Radiolabeling strategies using prosthetic groups for CooP conjugation. (A) Chemical structures of the prosthetic groups [18F]FNA and [18F]FB. (B) Radiosynthesis scheme of [18F]FNA-N-CooP.

(adapted from Dillemuth et al. 2024b). (C) Radiosynthesis of [18F]FB-N-CooP.

In a previous work, we have used [18F]FNA as a prosthetic group to prepare the radiolabeled nonapeptide [18F]FNA-N-CooP with N-acylation (Fig. 1, Dillemuth et al. 2024b). CooP is a brain tumor-homing peptide identified by in vivo phage-display (Hyvönen et al. 2014), and its sequence is H-CGLSGLGVA-NH2. The target of CooP peptide is the fatty acid-binding protein 3 (FABP3), which plays important roles in cancers and neurological diseases (Kawahata et al. 2019; McKillop et al. 2019). In the previous work by Hyvönen et al. in 2014, the indium-111 labeled CooP has been successfully used for glioblastoma imaging with single-photon emission computed tomography, which has promted us to develop 18F-labeled CooP for PET applications. The N-acylated compound [18F]FNA-N-CooP has the thiol group free at the cysteine residue, and the free thiol is considered important for target binding (Ayo et al. 2020). The binding specificity of [18F]FNA-N-CooP to FABP3 has been confirmed with in vitro tissue binding and blocking experiments, and immunostaining (Dillemuth et al. 2024b). Herein, we report the in vivo PET imaging, tumor and tissue uptake kinetics, brain tissue autoradiography and histological staining, and ex vivo biodistribution studies of [18F]FNA-N-CooP in a mouse model of intracranial glioblastoma, prepared from patient-derived BT12 cells (Le Joncour et al. 2019). Consistent with previous findings in healthy mice (Dillemuth et al. 2024b), [18F]FNA-N-CooP exhibits in vivo instability with one of its major radiometabolites identified as the prosthetic compound [18F]FNA. Both previous studies (Dillemuth et al. 2025) and the control experiments presented here demonstrate that [18F]FNA itself can visualize the tumors, thereby complicating the interpretation of imaging results obtained with [18F]FNA-N-CooP. To address this, we conducted further control experiments using [18F]FB-N-CooP, in which [¹⁸F]FB was employed as the prosthetic group instead of [18F]FNA (Fig. 1). To further investigate the role of [18F]FNA as a radiometabolite in [18F]FNA-N-CooP PET imaging, in vivo blocking studies were performed using AZD3965, an agent previously shown to reduce tumor uptake of [18F]FNA in the same mouse model (Dillemuth et al. 2025). Finally, we highlight the critical importance of conducting appropriate control experiments when using prosthetic groups for radiolabeling biomolecules, particularly in the cases where the prosthetic groups are cleaved in vivo as major radiometabolites.

Methods

Material and general methods

Precursor compound N,N,N-trimethyl-5-((4-nitrophenoxy)carbonyl)pyridin-2-aminium trifuoromethanesulfonate for the radiosynthesis of [18F]FNA 4-nitrophenyl ester was purchased from R&S Chemicals (Kannapolis, NC, USA). Precursor compound ethyl 4-N,N,N-trimethylammoniumbenzoate triflate for the radiosynthesis of [18F]SFB was purchased from ABX GmbH (Radeberg, Germany). CooP peptide (H-CGLSGLGVA-NH2) and the non-radioactive peptide references FNA-N-CooP (FNA-CGLSGLGVA-NH2) and FB-N-CooP (FB-CGLSGLGVA-NH2) were purchased from United Biosystems (Herndon, VA, USA). 4′,6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, Vectashield, Vector Laboratories, Newark, NJ, USA), mouse monoclonal FABP3/MDGI (66E2) antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA), rat anti-mouse CD31 (MEC13.3) antibody (BD Pharmingen, BD Biosciences), and secondary antibodies Alexa Fluor-488 goat-anti-mouse (A11001) and Alexa Fluor-647 donkey-anti-rat (A78947) were purchased from Thermo Fisher (Life Technologies, Waltham, MA, USA). [18F]FNA was prepared according to the published method (Dillemuth et al. 2025).

Preparation of [18F]FNA-N-CooP

[18F]FNA-N-CooP was prepared with a custom-designed radiosynthesis device (DM Automation, Sweden) with similar procedures as reported previously (Fig. 1, Dillemuth et al. 2024b). Briefly, [18F]FNA 4-nitrophenyl ester was synthesized by nucleophilic 18F-fluorination reaction using N,N,N-trimethyl-5-((4-nitrophenoxy)carbonyl)pyridin-2-aminium trifluoromethanesulfonate as the precursor, and purified with semi-preparative high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). The HPLC fraction containing [18F]FNA 4-nitrophenyl ester was diluted with 25 mL of water and passed through two Sep-Pak tC18 Plus Light Cartridges (tC18; Waters, Milford, MA, USA) connected in tandem. Subsequently, [18F]FNA 4-nitrophenyl ester was eluted with 0.4 mL acetonitrile into a reaction vial, and a solution of CooP peptide (5.0 mg, 6.5 µmol) in 350 µL borate buffer (300 mM, pH 8.6) was added. After incubation for 10 min at room temperature, the product [18F]FNA-N-CooP was isolated with HPLC and formulated in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 14 mM ascorbic acid to prevent radiolysis.

Preparation of [18F]FB-N-CooP

[18F]FB-N-CooP was prepared by N-acylation of CooP peptide in the presence of [18F]SFB as the prosthetic compound (Fig. 1), and [18F]SFB was prepared as previously (Gent et al. 2013) with a remote-controled device (DM Automation, Nykvarn, Sweden, Li et al. 2014). Accordingly, [18F]fluoride was trapped on a QMA-light Sep-Pak cartridge (WAT023525, Waters, Milford, MA, USA) preconditioned with 10 mL 0.5 M NaHCO3 and 10 mL water. The [18F]fluoride was then eluted into the reaction vial using a solution of Kryptofix 222 (14.18 mg, 37.64 µmol) and potassium carbonate (3.27 mg, 23.67 µmol) in 1.2 mL of 91% acetonitrile in water. The eluted [18F]fluoride was dried by azeotropic evaporation. Following drying, ethyl 4-N,N,N-trimethylammoniumbenzoate triflate (5.00 mg in 0.5 mL of dry acetonitrile) was added, and the fluorination reaction mixture was heated at 82℃ for 15 min to yield ethyl 4-[18F]fluorobenzoate. Tetrapropylammonium hydroxide (1.0 M solution in water, 40 µL in 0.5 mL of acetonitrile) was then added, and the reaction was heated at 100℃ for 6 min to produce [18F]FB as the corresponding tetrapropylammonium salt. After saponification, the reaction mixture was dried. O-(N-succinimidyl)-1,1,3,3-tetramethyluronium tetrafluoroborate (20.00 mg in 0.6 mL of acetonitrile) was then added, and the reaction mixture was heated at 93℃ for 8 min to form [18F]SFB. After cooling, the reaction mixture was diluted with 75 mM HCl solution and purified by semi-preparative HPLC using a Jupiter 4 μm Proteo 90 Å column (250 × 10 mm; Phenomenex, Torrance, CA, USA) with a gradient of 27–70% solvent B over 15 min (solvent A: H2O with 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA), solvent B: CH3CN with 0.1% TFA) at a flow rate of 4 mL/min. The retention time was approximately 15 min. The purified [18F]SFB was trapped on a hydrophilic-lipophilic balance (HLB) cartridge (Oasis 30 mg, 186005125, Waters, Milford, MA, USA) preconditioned with 10 mL EtOH and 10 mL water, and eluted with 0.4 mL acetonitrile for subsequent conjugation.

The eluted [18F]SFB was conjugated with 5 mg of CooP peptide in 350 µL borate buffer (pH 8.6, 300 mM) at ambient temperature for 10 min. The resulting [18F]FB-N-CooP was purified by semi-preparative HPLC using Jupiter 4 μm Proteo 90 Å column (250 × 10 mm; Phenomenex) with a gradient of 0–55% solvent B in 25 min (solvent A: H2O with 0.1% TFA, solvent B: CH3CN with 0.1% TFA) at 4 mL/min, yielding a retention time of approximately 24 min. The purified product was trapped on a preconditioned tC18 cartridge (Waters, WAT036805; Milford, MA, USA) preconditioned with 10 mL EtOH and 10 mL water, and eluted with 50% ethanol. The final formulation of [18F]FB-N-CooP was 8% ethanol in PBS containing 14 mM ascorbic acid. The chemical identity and radiochemical purity of [18F]FB-N-CooP were analyzed by an analytical HPLC using a Jupiter 4 μm Proteo 90 Å column (250 × 4.6 mm, Phenomenex) with a gradient of 20–42% B over 10 min (A: H2O with 0.1% TFA, B: CH3CN with 0.1% TFA) at 1 mL/min. The commercially available reference compound FB-N-CooP was used in the HPLC analysis to confirm the chemical identity of [18F]FB-N-CooP.

Preparation of mouse model with glioblastoma xenografts

All animal work was approved by the National Project Authorisation Board in Finland (permission numbers ESAVI/10262/2022, ESAVI/3630/2023), and was carried out in compliance with the EU Directive 2010/EU/63 on the protection of animals used for scientific purposes. Mouse model of intracranial BT12 glioblastoma was prepared as previously reported (Filppu et al. 2021). In brief, intracranial engraftment of BT12 cells was performed on immunocompromised female mice (Rj: NMRI-FOXn1nu/nu strain, aged 6─7 weeks, Janvier Labs, Le Genest-Saint-Isle, France). Using a stereotaxic device (World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL, USA), 0.5 × 105 glioblastoma cells suspended in 5 µL of 0.9% saline were injected into the right hemisphere of the mouse brain with an XG needle attached to a Hamilton syringe. The injection site was located 2.0 mm from the bregma and inserted 2.5 mm into the brain parenchyma. Throughout the procedure, mice were anesthetized with 2–3% isoflurane and maintained at 37 °C using a heating plate and rectal probe connected to a temperature control system (World Precision Instrument). For pain management, mice received 0.01 mg/kg buprenorphine pre-operatively and 5 mg/kg carprofen post-operatively, with analgesic treatment continuing for two days following the procedure. The PET study was conducted on day 21 after the BT12 cell inoculation.

Animal PET imaging

In total, 21 mice were used in this work, and the study design is described in Supplemental Figure S1 (Additional file 1). PET imaging was performed similarly as previously reported (Dillemuth et al. 2025; Andriana et al. 2023). PET and high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) imaging were carried out using Molecubes small-animal PET and CT imaging systems (Molecubes NV, Gent, Belgium). Mice were provided with food and tap water ad libitum prior to the PET study. During the whole imaging procedure, mice were on a heating pad under anesthesia with continuous inhalation of 1─2% isoflurane. In a typical procedure, HRCT was first performed for the mice without the use of contrast agents, and the mice were then injected with [18F]FNA-N-CooP (4.70 ± 0.44 MBq, 0.10 ± 0.06 µg, n = 15), [18F]FNA (4.70 ± 0.10 MBq, n = 4) or [18F]FB-N-CooP (2.80 and 3.7 MBq each, n = 2) intravenously (i.v.) via tail vein with a cannula. Two mice were simultaneously imaged, with 60-min dynamic PET data collected in list mode. For in vivo blocking experiments, the procedure remained similar, except that the blocking agents (CooP peptide 500-fold excess to [18F]FNA-N-CooP, or AZD3965 1.1 mg/kg (MedChemExpress, Monmouth Junction, NJ, USA)) were intravenously injected 15 min prior to [18F]FNA-N-CooP administration. PET data reconstruction utilized an OSEM-3D algorithm with time frames of 6 × 10 s, 4 × 60 s, 5 × 300 s, and 3 × 600 s, while CT reconstruction employed the iterative image space reconstruction algorithm (ISRA) method. PET/CT image analysis was conducted using Carimas 2.10 software. Regions of interest (ROIs) were defined using the spline tool, referencing either anatomical CT images or focal maxima in brain PET images. Results were expressed as standardized uptake values (SUVs), tumor-to-brain ratios (TBRs), and time-activity curves (TACs). SUV calculations accounted for injected radioactivity dose, animal body weight, and residual radioactivity in the cannula and tail.

Ex vivo biodistribution and tissue autoradiography

Ex vivo biodistribution and tissue autoradiography were performed following the published methods (Dillemuth et al. 2025; Andriana et al. 2023). Mice were euthanized immediately after PET imaging. This was accomplished through cardiac puncture of the left ventricle under deep anesthesia, followed by cervical dislocation. To eliminate residual blood radioactivity, the mice were perfused with 5─10 mL of PBS via the left ventricle of the heart. Twenty samples, including organs, tissues, plasma, and urine (Additional file 1: Supplemental Table S1), were then collected and analyzed using a Wizard 2 2480 3” gamma-counter (PerkinElmer, MA, USA). Radioactivity measurements were normalized based on the injected radioactivity dose per animal weight, tissue sample weights, and radioactivity decay. The injected radioactivity dose was adjusted to account for residual radioactivity in the tail and cannula. Results were presented as percentage of the injected radioactivity dose per gram (%ID/g) of tissue. Mouse brains were snap frozen in dry ice-cooled isopentane and sectioned into 20-µm- and 10-µm-thick cryosections. The 20-µm sections were thaw-mounted onto microscopy slides and exposed overnight to a phosphor imaging plate BAS-TR2025 (Fujifilm, Tokyo, Japan) within lead shielding. Digital autoradiographs were obtained using a BAS-5000 scanner (Fujifilm, Tokyo, Japan) and analyzed with Carimas software (Turku PET Centre, Turku, Finland). Results were expressed as photo-stimulated luminescence per square millimeter (PSL/mm2), with background correction applied. Following autoradiography, the same tissue sections underwent standard hematoxylin-eosin (H&E) staining at the University of Turku’s Histology core facility. The adjacent 10 μm-thick brain tissue sections were subjected to immunostaining.

Immunofluorescence staining of brain tissues

Frozen tissue sections, each 8-µm-thick, were initially rinsed with PBS (10 mM Na2HPO4, 2.7 mM KCl, 140 mM NaCl, pH 7.4) for 10 min. This was followed by fixing the tissues in a 4% paraformaldehyde solution for another 10 min at room temperature. The tissues underwent a 10-min PBS wash, were permeabilized with 0.3% Triton X-100 in PBS for 5 min, and then washed again in PBS for 10 min. Subsequently, the tissues were blocked in a PBS solution containing 0.03% Triton X-100 and 1% bovine serum albumin for 60 min at room temperature. They were then incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies: mouse monoclonal anti-FABP3 (sc-58274, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Heidelberg, Germany) and rat monoclonal anti-mouse CD31 (BD Pharmingen, BD Biosciences, Heidelberg, Germany), diluted at 1:50 and 1:800 in blocking buffers, respectively. After a 10-min PBS wash, the tissue sections were treated with AlexaFluor-conjugated secondary antibodies for 120 min and counterstained with 2-(4-amidinophenyl)-1 H-indole-6-carboxamidine (DAPI) to visualize cell nuclei. Finally, the sections were mounted using Mowiol (Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO, USA), and images of the entire tissue sections were captured using a digital slide scanner (Pannoramic P1000, 3DHistech Ltd., Budapest, Hungary).

Blood radioactivity and in vivo stability analysis

Following a 60-min dynamic PET imaging, blood samples were taken into heparinized tubes and centrifuged (2,100 × g, 5 min) to separate blood cells from plasma. Plasma proteins were precipitated using an equal volume of acetonitrile and removed by centrifugation (14,000 × g, 3 min) at room temperature. A Wizard gamma-counter was used to measure radioactivity in the isolated blood components, precipitated protein fraction, and protein-free plasma fraction. Protein-free plasma supernatant underwent HPLC analysis with a PerkinElmer Radiomatic 150TR flow scintillation analyzer. The analysis utilized a reversed-phase C18 column (Jupiter Proteo, 250 × 10 mm, 5 μm, 90 Å, Phenomenex) with a 5 mL/min flow rate. Solvents were 0.1% TFA in water (A) and 0.1% TFA in acetonitrile (B). The HPLC elution gradient ranged from 12 to 48% B during 0 to 18 min and from 48 to 80% B during 18 to 20 min. To isolate radioactive compounds from mouse brain tissues, the brain samples were homogenized, and an equal volume of acetonitrile was added. After centrifugation, the supernatant was analyzed with HPLC similarly as described above. To identify intact [18F]FNA-N-CooP and [18F]FNA in the supernatant sample, reference samples of these compounds in their final formulation solutions were analyzed by HPLC using the methods described above. The resulting retention times were then compared to those observed in the supernatant and brain homogenate HPLC chromatograms to identify the [18F]FNA-N-CooP and [18F]FNA signals. For further confirmation, a sample of [18F]FNA was co-injected with the supernatant sample.

Statistical analysis

GraphPad Prism version 10 was used for statistical analyses. Data was expressed as mean ± standard deviation. The differences between independent datasets were determined with an unpaired Student’s t-test. P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Radiosynthesis of [18F]FNA-N-CooP and [18F]FB-N-CooP

[18F]FNA-N-CooP was prepared in a two-step synthesis process with a decay-corrected radiochemical yield of 16.7 ± 5.6% (n = 3) and a radiochemical purity of 96.0 ± 3.7%. The molar activity at the end of synthesis was 108.8 ± 55.0 GBq/µmol, with a synthesis time of 173 ± 11 min. [18F]FB-N-CooP was obtained in a four-step synthesis process with a decay-corrected radiochemical yield of 21.5 ± 2.1% (n = 3). The radiochemical purity was 94.8 ± 1.0% at the end of the synthesis, and the chemical identity was confirmed by using the custom-synthesized non-radioactive reference FB-N-CooP. Representative HPLC chromatograms for the quality control were shown in Additional File 1 (Supplemental Figure S2).

Glioblastoma PET imaging with [18F]FNA-N-CooP and the control experiments

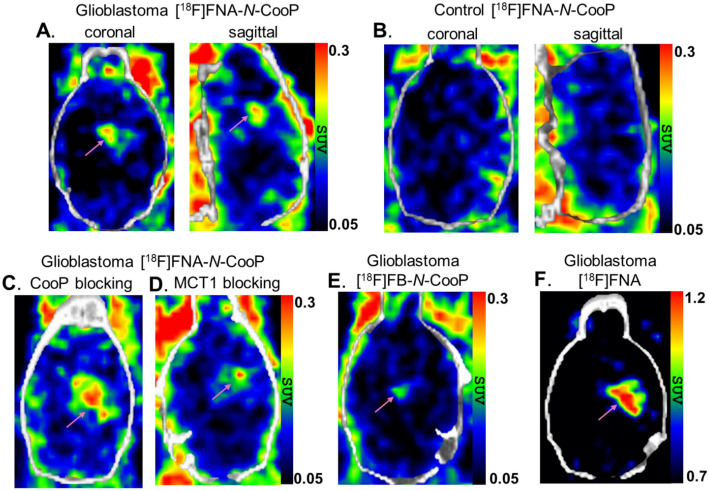

An in vivo PET study was performed in mice with glioblastoma and in healthy mice serving as controls. Representative brain PET/CT images are presented in Fig. 2A-F. At day 21 post intracranial BT12 cell inoculation, mice with glioblastoma xenografts were PET imaged with [18F]FNA-N-CooP, and HRCT was used for anatomical reference and attenuation correction. Intracranial glioblastomas were clearly delineated (Fig. 2A). The SUVs in tumor and healthy brain were 0.21 ± 0.03 (n = 4) and 0.11 ± 0.02 (P < 0.01), and the tumor-to-brain ratio (TBR) was 1.84 ± 0.29. There was no focal uptake in the corresponding brain areas in the healthy control mice (Fig. 2B). To evaluate tumor uptake specificity, in vivo blocking experiments were performed with preadministration of 500-fold excess of non-radiolabeled CooP peptide (Fig. 2C). However, the difference in tumor uptake was not statistically significant (P = 0.57) between the blocking experiments (SUV 0.23 ± 0.06, n = 4) and the non-blocking group (0.21 ± 0.03, n = 4).

Fig. 2.

Brain PET/CT images in healthy and glioblastoma-bearing mice (tumors indicated by magenta arrows). (A) Tumor visualization with [18F]FNA-N-CooP in glioblastoma-bearing mouse. (B) Control PET/CT scan with [18F]FNA-N-CooP in a healthy mouse. (C) [18F]FNA-N-CooP PET/CT imaging in glioblastoma-bearing mice following co-injection with a 500-fold excess of unlabeled CooP peptide as a blocking agent. (D) [18F]FNA-N-CooP PET/CT imaging with the MCT1 inhibitor (1.1 mg/kg) as a blocking agent in glioblastoma-bearing mice. (E) Control PET/CT imaging using [18F]FB-N-CooP in a glioblastoma-bearing mouse. (F) Control PET/CT imaging with [18F]FNA in a glioblastoma-bearing mouse. [18F]FNA-N-CooP PET images represent time-weighted averages of frames from 10─50 min post-injection; [18F]FB-N-CooP and [18F]FNA images are averages of frames from 5─40 and 5─25 min postinjection, respectively

Consistent with the previously reported instability of [18F]FNA-N-CooP in healthy mice (Dillemuth et al. 2024b), we observed that [18F]FNA-N-CooP was not stable in vivo in this mouse model either. The major radiometabolite at 60 min postinjection was the prosthetic group [18F]FNA in the plasma samples (Fig. 3A─3 C). In the brain homogenate samples from two mice, [18F]FNA was the only observed radiometabolite (Fig. 3D and E) under the used experimental conditions. The identity of the isolated [18F]FNA from mouse plasma was further confirmed with coinjection of the plasma sample and tracer standard [18F]FNA for HPLC analysis, and a clear single peak was observed at the expected retention time (Fig. 3F). In addition, the blood component binding of [18F]FNA-N-CooP in the blood samples was also assessed. In healthy control mice, the blood cell binding of the total radioactivity in the blood samples was 18.61% ± 0.54 (n = 4), while the plasma protein binding of the total radioactivity in plasma was 51.07% ± 7.85.

Fig. 3.

HPLC chromatographs from the in vivo stability analysis of [18F]FNA-N-CooP detected by radioactivity. (A) Reference chromatogram of [18F]FNA-N-CooP. (B) Reference chromatogram of [18F]FNA. (C) Plasma sample collected 60 min after intravenous [18F]FNA-N-CooP injection. (D, E) Brain homogenate samples from two individual mice. (F) Co-injection of a mouse plasma sample with [18F]FNA reference standard

In the previous study, we found that [18F]FNA itself was taken up by the BT12 glioblastoma xenografts in mice, and the brain tumors were clearly visualized with PET (Dillemuth et al. 2025). As a reference datum, we included herein the [18F]FNA PET study in four mice with BT12 glioblastoma xenografts. With [18F]FNA PET, brain tumors were clearly visible (Fig. 2F). The SUVs in tumor and healthy brain were 0.90 ± 0.10 (n = 4) and 0.59 ± 0.05 (P < 0.01), and TBR was 1.51 ± 0.08. This prompted us to perform additional control experiments to clarify possible roles of the cleaved [18F]FNA in the PET imaging with [18F]FNA-N-CooP. As known previously (Dillemuth et al. 2025), monocarboxylate transporter 1 (MCT1) is an important transporter for [18F]FNA, and glioblastoma uptake has been reduced by 76% in the presence of AZD3965 (1.1 mg/kg), a potent inhibitor of MCT1. Accordingly, two glioblastoma mice were pre-administered intravenously with AZD3965 at a dose of 1.1 mg/kg bodyweight 15 min before [18F]FNA-N-CooP injection, and PET imaging was performed in dynamic mode for 60 min. In one mouse, the tumor was visible (Fig. 2D), albeit uptake was low (SUV 0.17). In the other mouse, tumor was not delineable.

To completely exclude the presence and any possible influence of [18F]FNA in the PET imaging, we performed a further control experiment in which the prosthetic group [18F]FNA was replaced with [18F]FB in the radiolabeling of CooP peptide (Fig. 1, Additional file 1: Supplemental Fig. S2). The radiolabeled peptide was named [18F]FB-N-CooP. PET imaging was then carried out with [18F]FB-N-CooP in two mice with glioblastoma under similar experimental procedures as with [18F]FNA-N-CooP. In one mouse, the brain tumor was not visible. In the other mouse, the tumor SUV (0.16) was also low, and the tumor was barely visible in the PET image (Fig. 2E) with a TBR of 1.28. As the near-background level of tumor uptake made the tumor delineation and radioactivity quantification challenging, further studies with [18F]FB-N-CooP were not carried out.

Tissue uptake kinetics and ex vivo biodistribution

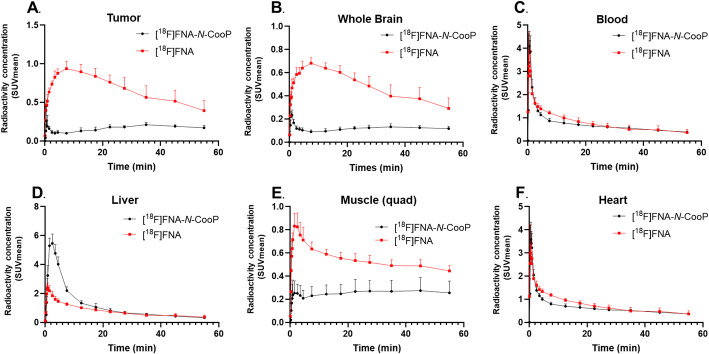

With in vivo PET imaging data, we have quantified tissue uptake kinetics in tumor, whole brain, blood, liver, muscle, and heart (Fig. 4). Due to the in vivo instability of [18F]FNA-N-CooP, the radioactivity-based quantification was a summation of all the radiometabolites, including [18F]FNA and the intact tracer. According to the previous study (Dillemuth et al. 2024b), there were a few other radiometabolites in addition to [18F]FNA, and the proportion of [18F]FNA among the radiometabolites was different at different time points postinjection. [18F]FNA was the only radiometabolite for which we have so far confirmed the chemical identity. Therefore, we took [18F]FNA as a reference in the comparison analysis of tissue uptake kinetics with [18F]FNA-N-CooP. According to the TACs (Fig. 4), there were distinct differences in uptake kinetics in the tumor, whole brain, and muscle (quad). In the case of [18F]FNA, in general, the tissue radioactivity concentration peaked earlier and decreased faster than [18F]FNA-N-CooP. As an example, [18F]FNA concentration in the tumor reached the highest level at approximately 4─8 min, and the TAC showed a sharper descending trend in comparison to [18F]FNA-N-CooP (Fig. 4A). Both radiotracers had fast clearance from blood circulation, liver, and heart (Fig. 4C, D and F).

Fig. 4.

Tissue uptake kinetics of [18F]FNA-N-CooP and [18F]FNA during 60-min dynamic PET imaging in mice bearing glioblastoma

To quantify the biodistribution of radioactivity in various organs and tissues, radioactivity measurements were performed with gamma counting for the collected 20 samples from each mouse immediately after PET imaging at 60 min postinjection (Fig. 5 and Additional file 1: Supplemental Table S1). In [18F]FNA-N-CooP PET in mice with glioblastoma, high radioactivity concentration was observed in urine (%ID/g 772.29 ± 373.58, n = 7) and kidneys (%ID/g 8.88 ± 6.16). The radioactivity concentration in the rest of the samples was relatively low (%ID/g ≤ 1.67). In healthy mice, the uptake in most of the tissues was not statistically different from that of mice with glioblastoma, except for the brain and spleen. In the blocking experiments with the CooP peptide, radioactivity concentration in the skull bone was statistically lower (P < 0.05) compared to non-blocking experiments. In all other tissues, there was no significant difference between the CooP blocking and non-blocking groups of mice. In comparison with [18F]FNA PET, brain, skull, and femur bone uptake was significantly lower, but higher in the small intestine (without contents). In all other tissues, the difference was not statistically significant. The radioactivity biodistribution patterns are also shown in the whole body PET images (Fig. 6), and the most intense signals came from the liver, kidneys, and urinary bladder contents. In the [18F]FNA-N-CooP imaging of mice with glioblastoma (Fig. 6A and B), the tumor was not visualized using the SUV color scale of 0.6–1.3, while the tumor was clearly visible with [18F]FNA PET (Fig. 6D and E).

Fig. 5.

Histogram showing the ex vivo biodistribution of [18F]FNA-N-CooP and [18F]FNA in mice bearing glioblastoma. Statistical significance was determined using Student’s t-test and is indicated as follows: * (P < 0.05), ** (P < 0.01), and *** (P < 0.001)

Fig. 6.

Whole-body PET/CT imaging of [¹⁸F]FNA-N-CooP and [¹⁸F]FNA in glioblastoma and healthy mice. PET/CT images of glioblastoma-bearing mice following injection of (A) [18F]FNA-N-CooP alone and (B) co-injected with [18F]FNA-N-CooP and an excess of unlabeled CooP peptide as a blocking agent (C) PET/CT image of a healthy mouse injected with [¹⁸F]FNA-N-CooP. (D, E) PET/CT images of glioblastoma-bearing mice injected with [¹⁸F]FNA. Tumor locations are indicated by magenta arrows. PET images represent time-weighted averages of frames acquired from 5─50 min post-injection for panels A─D, and 5─30 min for panel E

Co-localization of tumor radioactivity uptake with FABP3 positivity

After PET imaging, mouse brains were snap frozen and cryosectioned for autoradiography, H&E histology, and immunofluorescence staining. Brain tumor radioactivity uptake was focal (Fig. 7A) and correlated well with the tumor areas as observed in H&E (Fig. 7B). Adjacent tissue sections were stained with anti-FABP3 antibody for immunofluorescence imaging (Fig. 7C), and the observed radioactivity uptake co-localized with the FABP3 positivity. In the same tissue sections, endothelial cells were stained with an anti-CD31 antibody (Fig. 7D), as FABP3 is expressed not only in tumor cells but also in tumor vasculature (Hyvönen et al. 2014). Cell nuclei were clearly visualized using DAPI staining (Fig. 7E).

Fig. 7.

[¹⁸F]FNA-N-CooP autoradiography, H&E staining, and immunofluorescence staining of brain tissues containing tumor. The same tissue section was used for (A) autoradiography and (B) hematoxylin-eosin (H&E) staining. An adjacent section was immunostained for (C) FABP3 and (D) CD31, with (E) cell nuclei counterstained using DAPI. Panel (F) shows the merged image of FABP3, CD31, and DAPI staining

Discussion

CooP is a brain-tumor homing peptide identified by in vivo phage-display methods and has been previously radiolabeled with indium-111 (111In) for single-photon emission computed tomography imaging in a mouse model with U87MG glioblastoma (Hyvönen et al. 2014). For PET imaging purposes, we have recently prepared the 18F-labeled CooP, [18F]FNA-N-CooP, by using [18F]FNA as the prosthetic group (Dillemuth et al. 2024b). In this work, we have performed PET evaluation of [18F]FNA-N-CooP in a mouse model of intracranial BT12 glioblastoma xenograft. With intravenously administered [18F]FNA-N-CooP, the glioblastoma xenografts were clearly visualized. However, [18F]FNA-N-CooP was not stable in vivo, and the prosthetic group [18F]FNA is one of the major radiometabolites. In our previous study, we observed that [18F]FNA itself has uptake in the same mouse model, generating clear PET images of the brain tumor (Dillemuth et al. 2025). This prompted us to carry out additional follow-up experiments to clarify any possible roles of the cleaved [18F]FNA in the PET study using [18F]FNA-N-CooP. In comparison to [18F]FNA PET, clear differences have been observed in the PET imaging, tumor TACs, and ex vivo biodistribution patterns in [18F]FNA-N-CooP PET. In addition, autoradiographic analysis of tumor tissue showed that [18F]FNA-N-CooP uptake co-localized with FABP3 expression. On the other hand, it is highly possible that the radiometabolite [18F]FNA has a significant contribution to the observed tumor uptake, based on the MCT1 blocking study and the control experiments with [18F]FB-N-CooP. Currently, we are not able to provide an explanation why [18F]FB-N-CooP did not work. Similar to other PET imaging agents that are not sufficiently stable in vivo, the PET imaging and biodistribution data indicate the summation of radiometabolites and intact radiotracer (if any left), thus not being largely representative of the intact [18F]FNA-N-CooP.

Unfortunately, it is common that biomolecules such as peptides and oligonucleotides have limited in vivo stability and that poses challenges in developing those agents for in vivo applications (Evans et al. 2020). To stabilize the peptides, including [18F]FNA-N-CooP, methods to try would include α-methylation and the use of retro-inverso analogues (Doti et al. 2021; Evans et al. 2020). Regardless, biomolecules are frequently radiolabeled utilizing prosthetic groups, and in the literature there are many types of prosthetic groups available based on numerous types of conjugation chemistry. Prosthetic groups are intended to facilitate the radiolabeling of biomolecules with convenience, and/or modulate the pharmacokinetics of biomolecules. In the cases where the cleaved prosthetic groups are the major radioactive chemical compounds instead of the intact parent radiolabeled biomolecules, special attention needs to be paid to the possible roles of prosthetic groups in study results. This work is an excellent example demonstrating the importance of control experiments with prosthetic groups themselves in PET studies when prosthetic groups are cleaved in vivo.

Conclusion

Intracranial BT12 glioblastoma xenografts in mice were clearly visualized with PET imaging following intravenous administration of either [18F]FNA-N-CooP or [18F]FNA. However, [18F]FNA-N-CooP exhibited rapid in vivo degradation, with the prosthetic group [18F]FNA identified as a major radiometabolite. Although distinct PET imaging and biodistribution patterns were observed between [18F]FNA-N-CooP and [18F]FNA, the PET signal and quantitative data likely reflect, to a significant extent, the biological behavior of radiometabolites, including [18F]FNA. The in vivo instability of [18F]FNA-N-CooP remains a major challenge in its development as a radiopharmaceutical. From a radiopharmacy perspective, control experiments using prosthetic groups alone are strongly recommended, in the cases where the prosthetic compound constitutes a substantial portion of the radiometabolite profile.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Additional File 1: Supplementary information about animal study design, HPLC chromatograms of [18F]FB-N-CooP, and ex vivo biodistribution

Acknowledgements

Tissue staining was digitized using a 3DHISTECH Pannoramic 250 FLASH II slide scanner at the Genome Biology Unit sup ported by HiLIFE and the Faculty of Medicine, University of Helsinki and Biocenter Finland. H&E staining was performed at the Histocore unit, University of Turku. We thank Aake Honkaniemi, David Ekwe, Saeka Shimochi, Emel Bakay, Jenni Virta, Marko Vehmanen, and Sami Paunonen for the kind assistance in some of the data collection.

Abbreviations

- CD31

Cluster of differentiation 31 protein

- CooP

Peptide with sequence of H-CGLSGLGVA-NH2

- FABP3

Fatty acid binding protein 3

- HPLC

High-performance liquid chromatography

- FNA

6-Fluoronicotinic acid

- PET

Positron emission tomography

- SFB

N-succinimidyl 4-[18F]fluorobenzoate

- SUV

Standardized uptake value

- TAC

Time-activity curve

- TBR

Tumor-to-brain ratio

- %ID/g

Percentage of injected radioactivity dose per gram (of tissue weight)

Author contributions

PD, AA, XZ, JMR, AR, AJA, PLa and XGL conceived and designed the experiments. JMR, AR, AJA, PLa and XGL supervised in data collection, data analysis and interpretation of results. PD, AA, XZ, PLö, HL, SK, TA, JK, JP, MWGM, and JR performed the experiments and analyzed the data. PD and XGL drafted the manuscript. All the authors critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Funding

We thank the research grants from the Finnish Cancer Foundation, the Finnish Cultural Foundation, the Turku University Foundation, Turku University Hospital, Sigrid Jusélius Foundation, and the Research Council of Finland (decision numbers 368560, 350117). This research was partially supported by the Research Council of Finland’s Flagship InFLAMES and ImmunoCAP projects, and the funding Decision Numbers were 337530, 357910, 352727.

Data availability

Supplemental data are provided in the Additional File 1. Additional data can be obtained from the correspondence author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval

All animal work was approved by the National Project Authorisation Board in Finland (permission numbers ESAVI/10262/2022, and ESAVI/3630/2023), and was carried out in compliance with the EU Directive 2010/EU/63 on the protection of animals used for scientific purposes.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

XGL is an Editorial Board member of EJNMMI Radiopharmacy and Chemistry. Other authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Andriana P, Makrypidi K, Liljenbäck H, Rajander J, Saraste A, Pirmettis I, et al. Aluminum fluoride-18 labeled mannosylated dextran: radiosynthesis and initial preclinical positron emission tomography studies. Mol Imaging Biol. 2023;25:1094103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayo A, Figueras E, Schachtsiek T, Budak M, Sewald N, Laakkonen P. Tumor-targeting peptides: the functional screen of glioblastoma homing peptides to the target protein FABP3 (MDGI). Cancers. 2020;12:1836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bispo ACA, Almeida FAF, Silva JB, Mamede M. Peptides radiofluorination: main methods and highlights. Int J Org Chem. 2022;12:16172. [Google Scholar]

- Cardinale J, Schäfer M, Benešová M, Bauder-Wüst U, Leotta K, Eder M, et al. Preclinical evaluation of 18F-PSMA-1007, a new prostate-specific membrane antigen ligand for prostate cancer imaging. J Nucl Med. 2017;58:42531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis RA, Drake C, Ippisch RC, Moore M, Sutcliffe JL. Fully automated peptide radiolabeling from [18F]fluoride. RSC Adv. 2019;9:863849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dierick H, Navarro L, Ceuppens H, Ertveldt T, Antunes ARP, Keyaerts M, et al. Generic semi-automated radiofluorination strategy for single domain antibodies: [18F]FB-labelled single domain antibodies for PET imaging of fibroblast activation protein-α or folate receptor-α overexpression in cancer. EJNMMI Radiopharm Chem. 2024;9:54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillemuth P, Karskela T, Ayo A, Ponkamo J, Kunnas J, Rajander J, et al. Radiosynthesis, structural identification and in vitro tissue binding study of [18F]FNA-S-ACooP, a novel radiopeptide for targeted PET imaging of fatty acid binding protein 3. EJNMMI Radiopharm Chem. 2024a;9:16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillemuth P, Lövdahl P, Karskela T, Ayo A, Ponkamo J, Liljenbäck H, et al. Switching the chemoselectivity in the Preparation of [18F]FNA-N-CooP, a free thiol-containing peptide for PET imaging of fatty acid binding protein 3. Mol Pharm. 2024b;21:414756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillemuth P, Ayo A, Airenne T, Lövdahl P, Bakay E, Zhuang X et al. Utilizing monocarboxylate transporter 1-mediated blood–brain barrier penetration for glioblastoma PET imaging with 6-[18F]fluoronicotinic acid. Mol Pharm. 2025, 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.5c00457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Doti N, Mardirossian M, Sandomenico A, Ruvo M, Caporale A. Recent applications of retro-inverso peptides. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:8677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans BJ, King AT, Katsifis A, Matesic L, Jamie JF. Methods to enhance the metabolic stability of peptide-based PET radiopharmaceuticals. Molecules. 2020;25:2314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filppu P, Ramanathan JT, Granberg KJ, Gucciardo E, Haapasalo H, Lehti K, et al. CD109-GP130 interaction drives glioblastoma stem cell plasticity and chemoresistance through STAT3 activity. JCI Insight. 2021;10:e141486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gent YY, Weijers K, Molthoff CF, Windhorst AD, Huisman MC, Smith DE, et al. Evaluation of the novel folate receptor ligand [18F]fluoro-PEG-folate for macrophage targeting in a rat model of arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2013;15:R37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giesel FL, Hadaschik B, Cardinale J, Radtke J, Vinsensia M, Lehnert W, et al. F-18 labelled PSMA-1007: biodistribution, radiation dosimetry and histopathological validation of tumor lesions in prostate cancer patients. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2017;44:67888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyvönen M, Enbäck J, Huhtala T, Lammi J, Sihto H, Weisell J, et al. Novel target for peptide-based imaging and treatment of brain tumors. Mol Cancer Ther. 2014;13:9961007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawahata I, Bousset L, Melki R, Fukunaga K. Fatty acid-binding protein 3 is critical for α-synuclein uptake and MPP+-induced mitochondrial dysfunction in cultured dopaminergic neurons. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:5358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keam SJ. Piflufolastat F 18: diagnostic first approval. Mol Diagn Ther. 2021;25:64756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Joncour V, Filppu P, Hyvönen M, Holopainen M, Turunen SP, Sihto H, et al. Vulnerability of invasive glioblastoma cells to lysosomal membrane destabilization. EMBO Mol Med. 2019;11:e9034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X-G, Haaparanta M, Solin O. Oxime formation for fluorine-18 labeling of peptides and proteins for positron emission tomography (PET) imaging: a review. J Fluor Chem. 2012;143:4956. [Google Scholar]

- Li X-G, Helariutta K, Roivainen A, Jalkanen S, Knuuti J, Airaksinen AJ. Using 5-deoxy-5-[18F]fluororibose to glycosylate peptides for positron emission tomography. Nat Protoc. 2014;9:13845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKillop IH, Girardi CA, Thompson KJ. Role of fatty acid binding proteins (FABPs) in cancer development and progression. Cell Signal. 2019;62:109336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olberg DE, Arukwe JM, Grace D, Hjelstuen OK, Solbakken M, Kindberg GM, et al. One step rdiosynthesis of 6-[18F]fluoronicotinic acid 2,3,5,6-tetrafluorophenyl ester ([18F]F-Py-TFP): a new prosthetic group for efficient labeling of biomolecules with fluorine-18. J Med Chem. 2010;53:173240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stotz S, Kinzler J, Nies AT, Schwab M, Maurer A. Two experts and a newbie: [18F]PARPi vs [18F]FTT vs [18F]FPyPARP—a comparison of PARP imaging agents. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2022;49:83446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Z, Meshaw R, Zalutsky MR, Vaidyanathan G. Site-specific and residualizing linker for 18F labeling with enhanced renal clearance: application to an anti-HER2 single-domain antibody fragment. J Nucl Med. 2021;62:162430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional File 1: Supplementary information about animal study design, HPLC chromatograms of [18F]FB-N-CooP, and ex vivo biodistribution

Data Availability Statement

Supplemental data are provided in the Additional File 1. Additional data can be obtained from the correspondence author on reasonable request.