Abstract

Chitinase h (Chi-h) has been identified as a promising pesticide target due to its exclusive distribution in lepidopteran insects and its essential role in the moulting processes. In this study, we leverage OfChi-h from destructive agricultural pest Ostrinia furnacalis (Asian corn borer) as a model target to identify novel chitinase inhibitors. A conformational restriction approach was employed to design a series of novel OfChi-h inhibitors. Among these, compound 6a showed the highest inhibitory activity against OfChi-h, with a Ki value of 58 nM. Molecular docking analysis suggested that 6a tightly bound to three subsites (-3 to −1) of OfChi-h. The binding mode is further confirmed by the co-crystallization data of 6a with the SmChiA, a bacterial homologue of OfChi-h, at a resolution of 1.8 Å. This research presents a novel approach for the development of highly potent insect chitinase inhibitors, offering potential tools for effective pest control.

Keywords: Chitinase, inhibitor, conformation restriction, inhibitory mechanism

GRAPHIC ABSTRACT

Introduction

Chitinase (EC 3.2.1.14) is an enzyme that hydrolyses β-1,4-glycosidic bonds in chitin and chitooligosaccharides. The loss of chitinase enzymatic activity in insects results in severe exoskeletal defects and lethality at all developmental stages, as chitin is an important structural component of insect cuticle1. Chitinase-h(Chi-h) is a lepidoptera-exclusive insect chitinase that is absent in most beneficial insects including parasitic wasps and bees. Chi-h is thought to be acquired through horizontal gene transfer from bacteria2 and it shows significantly lower sequence similarity to other insect chitinases. Moreover, the structure of Chi-h is significantly different from that of human and other insect chitinases3. Thus, Chi-h is a promising target, and its inhibitors hold potential for eco-friendly pesticide development, contributing to sustainable agriculture4.

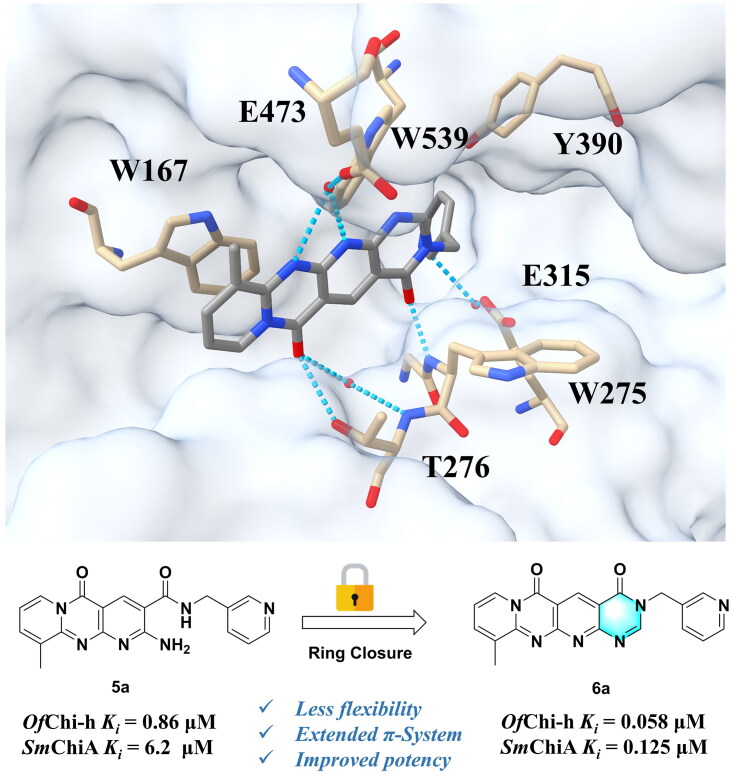

The only crystal structure of Chi-h is derived from Ostrinia furnacalis (OfChi-h), thereby establishing it as an important model for the development of Chi-h inhibitors1,3–5. OfChi-h features an elongated, asymmetric substrate-binding cleft containing seven distinct sugar-binding subsites, with multiple aromatic residues strategically positioned along the groove’s architecture. The co-crystal complex of OfChi-h-(GlcN)7 revealed that seven subsites, spanning from −5 to +2, are present in the binding cleft3 (Figure 1(a)). The sugar-binding subsites were named according to Davies et al.6 where subsite -n represents the non-reducing end, subsite + n represents the reducing end, and enzymatic cleavage occurs between the −1 and the +1 subsites. To date, several OfChi-h inhibitors have been reported, including chitoheptaose ((GlcN)7)3, the microbial secondary metabolite phlegmacin B17, the marine natural product Lynamicin B8, the aminoglycoside antibiotic Kasugamycin9, compound 2–8-s210, compound 5 m (also named as 6t in our previous report)11 and berberine along with its derivatives12,13. Several multitarget inhibitors of insect chitinolytic enzymes have also been reported, including Shikonin, Wogonin14, 3,5-Di-O-caffeoylquinic acid and γ-mangostin15 Rhein and its dimeric analogue Sennidin B16, Butenolide derivatives17,18 and guanidine-based inhibitors19–22.

Figure 1.

Binding clef of OfChi-h and its inhibitors. (a) OfChi-h in complex with (GlcN)7 (PDB: 5GQB) and (b) representative chitinase OfChi-h inhibitors.

Conformational restriction is a well-known strategy in drug and pesticide development23,24, which could be achieved by the enhancement of steric effects25, intramolecular hydrogen bonding26, ion pairing27, π–π stacking, incorporation of cyclic elements28, or fusion of adjacent rings. Compared with flexible ligands, similarly restrained ligands can form analogous pairwise interactions with the target while sacrificing fewer conformational degrees of freedom during complex formation, thereby resulting in a lower entropic penalty29 and improved binding affinity. In addition, conformational restriction by introducing fused rings offers potential advantages, such as reducing degradation and increasing selectivity towards certain receptor subtypes30.

GH18 chitinases possess surface-exposed aromatic residues in the binding cleft, which interact with sugars by a combination of hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic stacking interactions and have been shown to be essential for substrate binding. Although all the GH18 chitinases use the same catalytic mechanism, they exhibit variations in the shape of their substrate-binding cleft. Thus, rigid structures with fused rings may selectively inhibit certain types of chitinases. In our previous study, we identified 5 m11 as a potent OfChi-h inhibitor by introducing steric groups to restrain the conformation of 5a (Figure 1(b)). In this work, we reported the discovery of a novel rigid tetracyclic scaffold for OfChi-h inhibitors by ring closure to fix the conformation, with the expectation that it will enhance both inhibitory activity and selectivity. Among the designed compounds, compound 6a showed the highest inhibitory activity against OfChi-h with a Ki value of 58 nM. Furthermore, the structural analysis and docking results revealed that the tetracyclic scaffold binds to different sites within the chitinase, which will guide future chitinase inhibitors design.

Results and discussion

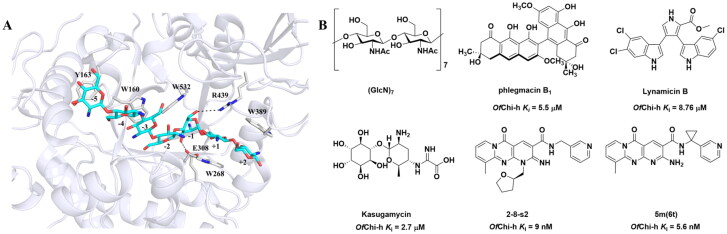

Rational design of a novel tetracyclic core

As previously reported, compound 5a was involved in several key interactions with residues in the active site of the chitinase as revealed by its X-ray cocrystal structure11. For example, the pyridopyrimidine moiety of compound 5a stacked with Trp97 and Trp220 at +1 and +2 subsites, respectively, and the 3-pyridyl nitrogen formed a hydrogen bond with the key catalytic residue Glu144. Interestingly, molecular docking indicated that 5a binds to OfChi-h in a different way. It is predicted to bind in the −3, −2 and −1 subsites of OfChi-h, while still forming a hydrogen bond with the key catalytic residue Glu308 (Figure 2(a)). In addition, the carbonyl oxygen atom of the amide group forms a hydrogen bond with the backbone of Trp268. Therefore, we designed a tetracyclic scaffold, compound 6a, with fewer rotatable bonds to lock it covalently into an active conformation, thereby improving potency. As shown by the superimposition of 5a and 6a (Figure 2(b)), the rigid tetracyclic core of 6a positions the carbonyl oxygen atom and the pyridine ring nearly exactly where they must be to maintain the active conformation of 5a. With this information in hand, we proceeded to synthesis 6a to test our hypothesis that conformation restriction improves potency.

Figure 2.

Design strategy of novel tetracyclic chitinase inhibitors. (a) Predicted binding mode of compound 5a with OfChi-h; (b) superimposition of compound 5a and compound 6a; (c) novel conformation restriction strategy by ring closure.

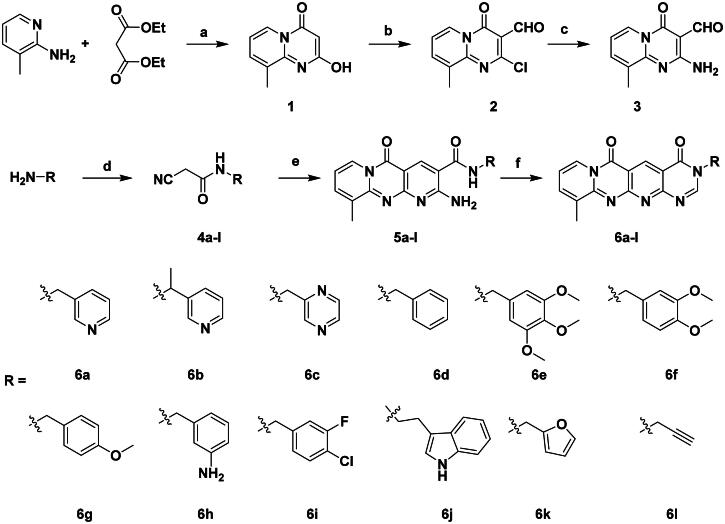

Chemistry

The target compounds 6a–6l were synthesised following the synthetic route depicted in Scheme 1. The starting material, 2-hydroxy-9-methyl-4H-pyrido[1,2-a]pyrimidin-4-one (compound 1), was prepared via a condensation reaction between 2-amino-3-picoline and diethyl malonate at 110 °C. Treatment of compound 1 with phosphorus oxychloride (POCl3) in DMF afforded 2-chloro-9-methyl-4-oxo-4H-pyrido[1,2-a]pyrimidine-3-carbaldehyde (compound 2), which was then reacted with excess aqueous ammonia in ethanol at 70 °C to give the key intermediate 2-amino-9-methyl-4-oxo-4H-pyrido[1,2-a]pyrimidine-3-carbaldehyde (compound 3). The cyanoacetamide derivatives 4a–4l were synthesised by the condensation of methyl cyanoacetate with the corresponding amines under neat conditions at room temperature. Subsequent condensation of intermediate 3 with cyanoacetamides 4a–4l in the presence of sodium hydroxide furnished compounds 5a–5l via a modified Friedländer reaction. Finally, treatment of 5a–5l with 1,1-dimethoxy-N,N-dimethylmethanamine (DMFDMA) under neat conditions at 110 °C yielded the desired tetracyclic target compounds 6a–6l. All the target compounds were confirmed by NMR spectroscopy and HRMS.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of target compounds 6a-l. Reagents and conditions: (a). neat, 110 °C; (b). POCl3, DMF, 0 °C-80 °C; (c). aqueous ammonia, EtOH, 70 °C; (d). methyl cyanoacetate, r.t. (e). NaOH/EtOH, 70 °C; (f). DMFDMA, neat, 110 °C.

Structure-activity relationship analysis

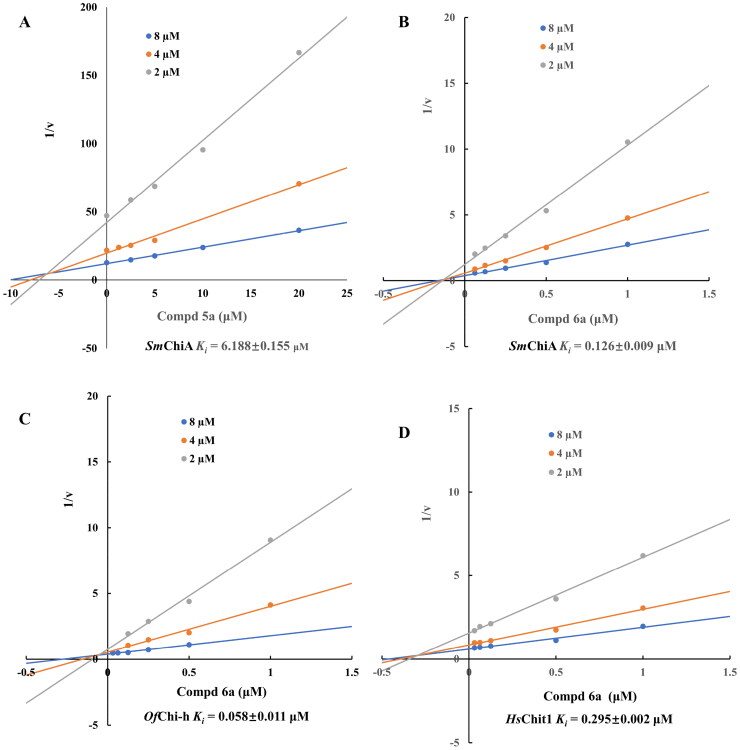

Originally, we sought to condense 5a with DMFDMA to afford 6a. As expected, 6a was obtained and tested against OfChi-h. To our delight, 6a showed a significant increase in inhibitory activity against OfChi-h, with a Ki value of 0.058 μM (Table 1 and Figure 3) compared to that of 5a11 (an approximately 15-fold improvement). The inspiring result motivated further modifications of 6a. Initially, a methyl group was introduced to the side chain of the pyridine to afford 6b (Figure S1). However, this modification unexpectedly resulted in a sharp decrease in inhibitory activity. Due to unsuccessful condensation reactions when larger substituents were introduced on the pyridine side chain, pyridine was replaced by pyrazine to produce compound 6c, in an effort to facilitate additional interactions with OfChi-h. However, 6c showed similar inhibitory activity to 6b (Figure S2). Compound 6d, bearing a phenyl substituent, exhibited further decreased inhibitory activity, with a Ki value of 1.419 μM (Figure S3). Though the introduction of fluorine and chlorine (6i) to the phenyl group failed to improve activity, the incorporation of an amino group (6h) and a methoxyl group (6 g) increased activity related to 6d (Figures S4 and S5). Surprisingly, the installation of a second methoxyl group (6f) and a third methoxyl group (6e) further enhanced the inhibitory activity against OfChi-h. 6e showed comparable activity to 6a, with a Ki value of 0.065 μM (Figure S3). Other attempts to substitute the pyridine group (6j-6l) also resulted in decreased activity, indicating that the pyridine group may interact with OfChi-h (Figures S4 and S5). We also tried to fuse 5 m to obtain a tetracyclic scaffold, as it showed the most potent activity in our previous study. However, the reaction is sensitive to the side chain of the amide, and 5 m failed to condensed into the corresponding tetracyclic structure due to the presence of a cyclopropyl group—a similar phenomenon was also observed by Wang31. In addition, the most potent compound 6a also displayed good inhibition activity against SmChiA (a bacterial homology of OfChi-h from Serratia marcescens) and HsChit1 (a chitinase from Homo sapiens), with a Ki value of 0.126 μM and 0.295 μM, respectively (Figure 3(b,d)).

Table 1.

Inhibition activity of 6a-6l against SmChiA and OfChi-h at 10 μM.

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compd | R | SmChiA |

OfChi-h |

|

| 10 μM (%) | 10 μM (%) | Ki (μM) | ||

| 6a |

|

98.5 ± 0.2% | 99.3 ± 0.2% | 0.058 |

| 6b |

|

88.7 ± 2.2% | 96.8 ± 0.1% | 0.215 |

| 6c |

|

91.5 ± 0.8% | 95.3 ± 0.5% | 0.294 |

| 6d |

|

32.0 ± 1.4% | 72.5 ± 2.4% | 1.419 |

| 6e |

|

28.2 ± 4.8% | 96.2 ± 0.3% | 0.065 |

| 6f |

|

34.2 ± 2.5% | 69.3 ± 4.4% | 0.747 |

| 6g |

|

30.3 ± 2.7% | 74.0 ± 2.0% | 1.032 |

| 6h |

|

37.9 ± 0.4% | 89.0 ± 1.5% | 0.276 |

| 6i |

|

31.7 ± 0.2% | 42.9 ± 1.0% | 2.889 |

| 6j |

|

42.4 ± 4.1% | 49.6 ± 2.2% | 0.551 |

| 6k |

|

47.5 ± 1.2% | 86.8 ± 0.8% | 1.509 |

| 6l |

|

37.5 ± 2.2% | 81.0 ± 0.8% | 1.338 |

| 5a 11 |

|

– | – | 0.86 |

Figure 3.

Representative Dixon plots for inhibition chitinase SmChi-A by 5a (a), and chitinase SmChi-A (b), OfChi-h (c) and HsChit1 (d) by 6a. The trend lines represent three substrate concentrations.

Elucidation of binding modes to OfChi-h

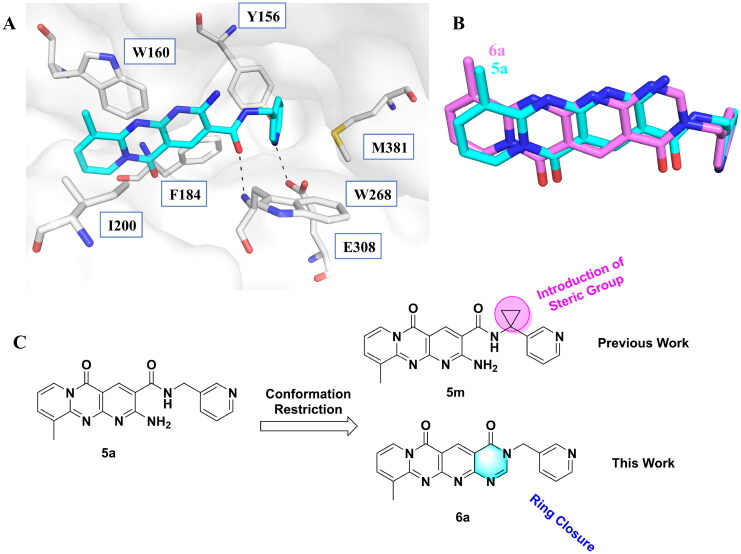

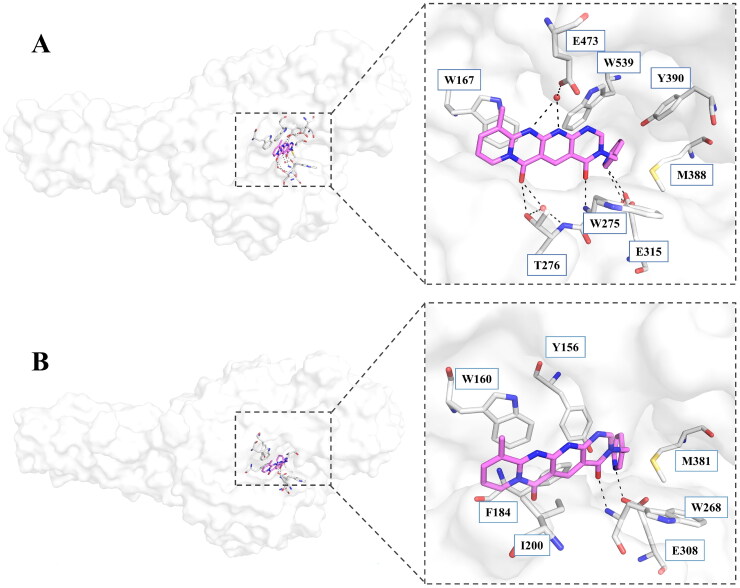

To investigate the binding mode of fused tetracyclic scaffold and to validate our hypothesis, we tried to obtain the crystal structure of OfChi-h and SmChiA in complex with the inhibitor 6a. However, only co-crystal structure SmChiA-6a was successfully obtained and refined. In this structure, compound 6a is bound at the −3, −2 and −1 subsites of SmChiA. The tetracyclic skeleton forms strong π-π interactions with Trp167, and the 11- and 12-nitrogen atoms of 6a form hydrogen bonds with the side chain of Glu473 through a water molecule. One of the carbonyl oxygen atoms in the tetracyclic backbone also forms a hydrogen bond with T276 through water-mediated network, while another carbonyl oxygen atom forms a direct hydrogen bond with the backbone of Trp275. The pyridine moiety inserts into a pocket at the bottom of the binding cleft, which is formed by Tyr390, Met388, and Trp539. The pyridine ring forms π-π stacking and π-S interactions with Trp539 and Met388, respectively. In addition, the nitrogen atom of the pyridine also forms a hydrogen bond with Glu315 through a water-mediated network. Since the SmChiA catalytic cleft is acidic, the nitrogen atom of pyridine moiety may guide the inhibitor to bind in the substrate-binding site.

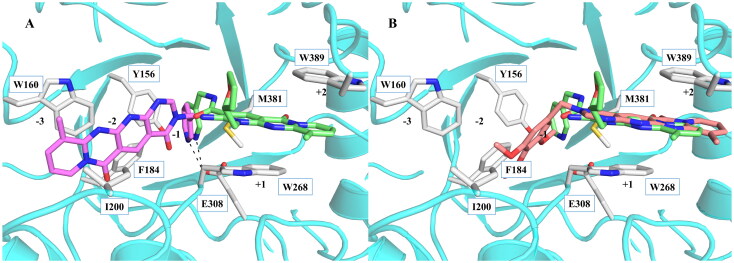

As we failed to obtain the crystal structure of OfChi-h in complex with 6a, molecular docking was used to investigate its binding mode. The docking results revealed that 6a binds to at the −3, −2 and −1 subsites of OfChi-h in a manner similar to SmChiA. The 3-pyridine group inserts into a binding cleft formed by Tyr156, Phe184, and Met381. The nitrogen atom forms a hydrogen bond with the key catalytic residue Glu308, as observed with inhibitor 2–8-s2 (Figures 4 and 5(a)). This interaction is likely responsible for the higher inhibitory activity against OfChi-h and explains the unsuccessful attempts to replace the 3-pyridine group. The tetracyclic skeleton of 6a forms strong π-π stacking interaction with Trp160, while a second carbonyl oxygen forms a hydrogen bond with backbone of the Trp268. In contrast, molecular docking showed that 6e binds to OfChi-h in a different manner (Figure 5(b)). The tetracyclic skeleton of 6e is sandwiched between Trp268 and Trp389, forming strong π-π stacking interactions similar to that of 2–8-s2. The trimethoxybenzene group inserts into −2 subsites of OfChi-h, because it is too bulky to fit into the binding cleft formed by Tyr156, Phe184, and Met381.

Figure 4.

Binding mode of 6a with SmChiA and OfChi-h. A. Binding mode of 6a with SmChiA revealed by co-crystal complex structure; B. Binding mode of 6a with OfChi-h revealed by molecular docking. 6a is shown in violet sticks, the key residues involved in inhibitor binding are shown in gray sticks, hydrogen bonds are shown as black dashed lines and water molecules are shown as red spheres.

Figure 5.

Superposition of 6a (a) and 6e (b) with 2–8-s2 in the binding site of OfChi-h. 6a is shown in violet sticks, 6e was shown in red sticks, 2–8-s2 was shown in light green sticks and the key residues involved in inhibitor binding are shown in gray sticks, hydrogen bonds are shown as black dashed lines.

Conclusion

In summary, this study demonstrates the successful development of conformationally restricted dipyridopyrimidine-3-carboxamide derivatives as potent inhibitors targeting OfChi-h. By employing a conformational restriction strategy, we discovered novel OfChi-h inhibitors with significantly improved inhibitory activity. The lead compound 6a exhibited exceptional potency (Ki = 58 nM) against OfChi-h, establishing its potential as a sustainable pesticide candidate. Notably, 6a also demonstrated promising activity against human chitinase HsChit1 (Ki = 295 nM), suggesting that this scaffold could also be repurposed to target human chitinases implicated in inflammatory diseases10,32–34. Structural investigations through molecular docking and high-resolution co-crystallization with SmChiA revealed that 6a binds to OfChi-h via a novel mechanism, occupying subsites −3 to −1 of the substrate-binding cleft. This binding mode not only validates the design rationale but also highlights the advantage of rigidifying the inhibitor scaffold to enhance target engagement. The fused tetracyclic skeleton introduced here serves as a robust structural template for designing selective chitinase inhibitors. Overall, this work underscores the broader utility of conformational restriction as a strategic tool in chitinase inhibitor discovery, bridging rational design with mechanistic validation, and paves the way for broader adoption of conformationally constrained scaffolds in chitinase inhibitors design.

Experimental section

Instruments and chemicals

Unless otherwise noted, standard and analytical graded reagents and solvents were obtained from Bide Pharmatech Ltd (Shanghai, China) and used without further purification. Ethanol, dichloromethane, methanol, and dimethyl sulfoxide were purchased from Shanghai Titan Scientific Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China), TLC plates (Silica gel 60 F254) and chromatography silica gel (200–300 mesh) were supplied by Qingdao Haiyang Chemical (Qingdao, China), N,N-Dimethylformamide dimethyl acetal (DMFDMA), were sourced from Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). All reactions were under ambient air. Melting points (M.p.) were recorded on Büchi B540 apparatus (Büchi Labortechnik, Flawil, Switzerland) and are uncorrected. High-resolution electron mass spectra (HRMS) were performed on Waters, Xevo G2 TOF spectrometer (MA, USA).1H NMR,19F NMR and 13C NMR spectra were recorded on Bruker AM-400 and Bruker ASCEND 600 MHz (1H at 400 MHz, 13C at 100 MHz or 150 MHz, 19F at 376 MHz) spectrometers with DMSO-d6 or CDCl3 as solvents and TMS as internal standard. Chemical shifts are reported in δ (parts per million). The following abbreviations were used to explain the multiplicities: s = singlet, d = doublet, t = triplet, q = quartette, m = multiplet, coupling constant (Hz) and integration.

General synthetic procedure of target compounds 6a-6l

Detailed synthesis procedures of compounds 5a-5l were described in our previous report11. Subsequently, to a round-bottom flask were added compound 5 (0.5 mmol, 1.0 equiv) and 1,1-dimethoxy-N,N-dimethylmethanamine (DMFDMA, 2.0 ml, approx. 15 mmol, ∼30 equiv). The mixture was stirred under neat conditions at 110 °C for 10–60 min (monitored by TLC). After completion, the reaction mixture was cooled to room temperature, and ethanol (2 ml) was added. The resulting solid was collected by filtration, washed with cold ethanol (2 × 1 ml), and dried under vacuum. The crude product was further purified by column chromatography on silica gel using DCM/MeOH (30:1) as eluent to afford the final compounds 6a–6l as yellow solids.

Analysis data of compounds 6a-6l

6a, Yellow solid, Yield: 67.3%, M.p.: 352.1–352.7 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 9.56 (t, J = 5.8 Hz, 1H), 8.93 (s, 1H), 8.74 (d, J = 7.1 Hz, 1H), 8.64 (s, 1H), 8.53 (d, J = 3.8 Hz, 1H), 7.88 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 7.78 (d, J = 6.7 Hz, 1H), 7.48 (dd, J = 7.8, 4.9 Hz, 1H), 7.08 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 1H), 4.52 (d, J = 5.7 Hz, 2H), 2.47 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO) δ 174.45, 166.09, 160.98, 157.66, 150.70, 147.89, 147.19, 143.29, 138.33, 136.58, 136.42, 135.25, 133.18, 125.47, 123.96, 113.42, 110.48, 100.85, 40.33, 17.82. HRMS-ESI (m/z): calcd for C20H15N6O2 [M + H]+, 371.1256; found, 371.1257.

6b, Yellow solid, Yield: 41.7%, M.p.: 302.5–304.7 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, Chloroform-d) δ 9.79 (s, 1H), 8.82 (d, J = 7.1 Hz, 1H), 8.74 (s, 1H), 8.63 (d, J = 4.0 Hz, 1H), 8.35 (s, 1H), 7.74 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 7.63 (d, J = 6.7 Hz, 1H), 7.37 (dd, J = 7.9, 4.9 Hz, 1H), 6.97 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 1H), 6.31 (q, J = 7.1 Hz, 1H), 2.70 (s, 3H), 1.95 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3) δ 161.48, 160.31, 159.65, 159.35, 151.84, 150.23, 150.01, 148.83, 142.07, 136.21, 135.60, 134.81, 134.45, 125.25, 123.84, 114.69, 113.58, 110.96, 50.79, 29.65, 18.84. HRMS-ESI (m/z): calcd for C21H17N6O2 [M + H]+, 385.1413; found, 385.1412.

6c, Yellow solid, Yield: 53.4%. M.p.: 306.1–307.0 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 9.25 (s, 1H), 8.87 (d, J = 1.6 Hz, 2H), 8.71 (m, 1H), 8.62 − 8.56 (m, 2H), 7.82 (m, 1H), 7.11 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 1H), 5.44 (s, 2H), 2.53 (s, 3H).13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO) δ = 161.62, 160.10, 159.17, 158.87, 154.60, 151.13, 150.90, 144.12, 144.01, 143.84, 139.36, 136.86, 133.75, 125.34, 114.14, 113.72, 110.52, 48.35, 18.05. HRMS-ESI (m/z): calcd forC19H14N7O2 [M + H]+, 372.1209; found, 372.1210;

6d, Yellow solid, Yield: 72.4%, M.p.: 303.8–304.5 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, Chloroform-d) δ 9.78 (s, 1H), 8.82 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 8.45 (s, 1H), 7.62 (d, J = 6.7 Hz, 1H), 7.47 − 7.30 (m, 5H), 6.96 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 1H), 5.22 (s, 2H), 2.70 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 160.69, 159.44, 152.56, 141.97, 139.56, 136.15, 135.64, 134.93, 129.90, 129.26, 129.12, 128.76, 128.38, 125.30, 115.18, 113.57, 110.91, 49.85, 29.34. HRMS-ESI (m/z): calcd for C21H16N5O2 [M + H]+, 370.1304; found, 370.1305;

6e, Yellow solid, Yield: 54.8%, M.p.: 329.8–331.1 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, Chloroform-d) δ 9.79 (s, 1H), 8.82 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 1H), 8.45 (s, 1H), 7.62 (d, J = 6.7 Hz, 1H), 6.96 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 1H), 6.62 (s, 2H), 5.13 (s, 2H), 3.86 (s, 6H), 3.83 (s, 3H).13C NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3) δ 161.97, 160.62, 159.54, 159.36, 153.76, 152.37, 151.81, 141.96, 138.30, 136.22, 135.56, 130.35, 125.24, 115.04, 113.59, 110.86, 105.56, 60.83, 56.21, 50.04, 18.82. HRMS-ESI (m/z): calcd for C24H22N5O5[M + H]+, 460.1621; found, 460.1620.

6f, Yellow solid, Yield: 59.1%, M.p.: 303.9–305.1 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, Chloroform-d) δ 9.78 (s, 1H), 8.81 (d, J = 7.1 Hz, 1H), 8.44 (s, 1H), 7.01 − 6.91 (m, 3H), 6.86 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 5.14 (s, 2H), 3.88 (s, 3H), 3.88 (s, 3H), 2.69 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 162.12, 160.73, 159.59, 159.44, 152.47, 151.83, 149.56, 149.49, 141.91, 136.12, 135.64, 127.34, 125.28, 121.14, 115.17, 113.55, 111.63, 111.44, 110.88, 56.02, 55.98, 49.76, 18.85. HRMS-ESI (m/z): calcd for C23H20N5O4[M + H]+, 430.1515; found, 430.1514.

6g, Yellow solid, Yield: 68.3%, M.p.: 311.8–314.6 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, Chloroform-d) δ 9.77 (s, 1H), 8.81 (d, J = 7.1 Hz, 1H), 8.44 (s, 1H), 7.61 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 1H), 7.36 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 2H), 6.92 (m,6.87–6.98 3H), 5.15 (s, 2H), 3.80 (s, 3H), 2.69 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 173.25, 160.43, 157.25, 154.87, 153.95, 149.83, 148.66, 147.36, 135.67, 135.01, 134.18, 133.97, 125.34, 123.44, 113.80, 100.67, 93.58, 38.62, 29.42, 17.89. HRMS-EI (m/z): calcd for C22H17N5O3[M] +, 399.1331; found, 399.1335.

6h, Yellow solid, Yield: 42.1%. M.p.: 324.6–326.3 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, Chloroform-d) δ 9.78 (s, 1H), 8.82 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 1H), 8.42 (s, 1H), 7.62 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 1H), 7.19 − 7.09 (m, 2H), 6.96 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 1H), 6.76 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 6.71 − 6.59 (m, 3H), 5.11 (s, 2H), 2.70 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3) δ 160.64, 159.52, 159.38, 152.61, 151.76, 147.17, 141.89, 136.07, 136.01, 135.56, 130.15, 129.83, 125.23, 118.19, 115.25, 115.13, 114.50, 113.49, 110.81, 49.64, 29.65. HRMS-ESI (m/z): calcd for C21H17N6O2[M + H]+, 385.1413; found, 385.1412.

6i, Yellow solid, Yield: 46.2%. M.p.: 353.5–354.5 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, Chloroform-d) δ 9.77 (s, 1H), 8.82 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 8.52 (s, 1H), 7.63 (d, J = 6.7 Hz, 1H), 7.31 − 7.27 (m, 2H), 7.20 − 7.13 (m, 1H), 6.97 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 1H), 5.34 (s, 2H), 2.70 (s, 3H). 19F NMR (376 MHz, DMSO) δ −115.22. 13C NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3) δ 161.93, 160.63, 159.62, 159.33, 158.47 (d, J = 250.0 Hz), 152.50, 151.84, 141.93, 136.23, 135.61, 134.51, 129.85 (d, J = 5.2 Hz), 128.13 (d, J = 8.0 Hz), 125.94 (d, J = 3.6 Hz),125.24, 116.86 (d, J = 21.3 Hz), 114.95, 113.60, 110.89, 47.21, 29.65. HRMS-ESI (m/z): calcd for C21H14 35ClFN5O2 [M + H]+, 422.0820; found, 422.0821; calcd for C21H14 37ClFN5O2 [M + H]+, 424.0791; found, 424.0795.

6j, Yellow solid, Yield: 43.4%. M.p.: 323.4–324.6 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.89 (s, 1H), 9.38 (s, 1H), 8.80 − 8.71 (m, 1H), 8.40 (s, 1H), 7.84 (dt, J = 6.7, 1.4 Hz, 1H), 7.60 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 7.35 (dt, J = 8.1, 1.1 Hz, 1H), 7.18 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H), 7.13 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 1H), 7.07 (ddd, J = 8.1, 6.9, 1.2 Hz, 1H), 6.95 (ddd, J = 7.9, 7.0, 1.0 Hz, 1H), 4.27 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 2H), 3.17 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 2H), 2.54 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (150 MHz, DMSO) δ 166.56, 163.44, 160.71, 160.24, 157.97, 153.85, 150.96, 146.18, 139.79, 136.64, 130.06, 129.37, 127.37, 123.88, 122.21, 121.90, 121.49, 118.83, 118.54, 110.40, 110.36, 53.14, 29.38, 18.24. HRMS-ESI (m/z): calcd for C24H19N6O2[M + H]+, 423.1569; found, 423.1571.

6k, Yellow solid, Yield: 33.4%. M.p.: 297.3–298.5 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, Chloroform-d) δ 9.76 (s, 1H), 8.81 (d, J = 6.9 Hz, 1H), 8.50 (s, 1H), 7.62 (d, J = 6.7 Hz, 1H), 7.47 − 7.37 (m,1H), 6.96 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 1H), 6.53 (d, J = 3.1 Hz, 1H), 6.42 − 6.33 (m, 1H), 5.21 (s, 2H), 2.70 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3) δ 161.99, 160.21, 159.51, 159.34, 152.26, 151.79, 147.51, 143.56, 141.86, 136.15, 135.56, 125.23, 115.04, 113.54, 110.87, 110.80, 110.59, 42.13, 18.80. HRMS-ESI (m/z): calcd for C19H14N5O3[M + H]+, 360.1097; found, 360.1098.

6l, Yellow solid, Yield: 34.2%. M.p.: 200.6.-201.3 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, Chloroform-d) δ 9.78 (s, 1H), 8.83 (d, J = 7.3 Hz, 2H), 8.67 (s, 1H), 7.64 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 2H), 6.97 (t, J = 6.8 Hz, 2H), 4.84 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 3H), 2.71 (s, 3H), 2.57 (s, 1H). 13C NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3) δ 161.94, 159.93, 159.63, 159.35, 151.86, 151.25, 141.89, 136.25, 135.61, 129.87, 125.26, 114.64, 113.62, 76.09, 75.55, 35.38, 18.80. HRMS-ESI (m/z): calcd for C17H12N5O2 [M + H]+, 318.0991; found, 318.0995.

Full 1H, 13C, 19F NMR and HRMS raw spectra of compound 6a-6l are included in (Supplementary Material Figures S7–S43).

Preparation and purification of enzyme

SmChiA was expressed in Escherichia coli BL21(DE3), HsChit1 and OfChi-h were overexpressed in Pichia pastoris GS115. The Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) strain was purchased from TaKaRa Biotech (Dalian, 6dChina) while the Pichia pastoris GS115 strain was obtained from Invitrogen (Thermo Fisher Scientific, CA, USA), both of which were cultured and handled according to the protocols provided by suppliers. All chitinases were purified using immobilised metal ion affinity chromatography as previously described35. Briefly, solid ammonium sulphate was slowly added to the culture supernatant to achieve 75% saturation. After incubation at 4 °C for 24 h, the precipitated proteins were collected by centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 30 min at 4 °C. The pellet was resuspended thoroughly in buffer A (20 mM sodium phosphate, 0.5 M sodium chloride, pH 7.4), and the solution was centrifuged again at 12,000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C to remove insoluble material. The clarified supernatant was loaded onto a 5 ml HisTrap™ Crude affinity column (GE Healthcare) that had been pre-equilibrated with buffer A. The column was subsequently washed with buffer A containing 75 mM imidazole to remove non-specifically bound proteins. Recombinant chitinases were eluted using buffer A containing 250 mM imidazole. The expressed proteins were quantified using a BCA protein assay kit (TaKaRa Biotech, China). And their purities were determined by SDS-PAGE and found to be >95% in all cases.

Chitinase inhibition assay and Ki determination

Chitinase activities for SmChiA, HsChit1 and OfChi-h were determined using 4-methylumbelliferyl-N, N′-diacetyl-β-D-chitobioside (MU-β-(GlcNAc)2) (purchased from Sigma) as a substrate. The final reaction mixture volume used for inhibitor screening was 100 μL, consisting of 10 nM enzyme, 4 μM MU-β-(GlcNAc)2, 10 μM inhibitor, and 2% DMSO in a 20 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 6.0). The reaction in the absence of inhibitor was used as a positive control. After incubation at 30 °C for 20 min, 0.5 M sodium carbonate was added to the reaction mixture, and the fluorescence produced by the released 4-MU was quantified with a Varioskan Flash microplate reader (Thermo Fisher Scientific) using excitation and emission wavelengths of 360 and 450 nm, respectively. Experiments were performed in triplicate unless specified otherwise. For Ki value determination, the inhibitor concentration was varied in the above reaction, and different concentrations of substrate (2–8 μM) were used. The amount of released 4-MU was quantified as above, and the Ki value and the mode of inhibition were determined using the Dixon plot.

Molecular docking

Protein structure for molecular docking was prepared using the protein preparation wizard in Maestro 10.2 (2015–2 release). The crystal structure of OfChi-h in complex with inhibitor 2–8-s2 (PDB: 6jmn) was used in molecular docking study. Bond orders were assigned, hydrogens were added and waters beyond 5 Å from inhibitor 2–8-s2 were deleted. The protein structure was the refined using PROPKA and minimised OPLS336 force field. The docking grid were generated by Receptor Grid Generation tool integrated in Glide.

The grid box dimensions were determined based on the coordinates of the bound 2–8-s2. A 10 Å*10 Å*10 Å inner grid box and a 20 Å*20 Å*20 Å outer grid box was used without other constraints. The 2D structures of 6a-6l were constructed by Chemdraw 17.1 and were imported to Maestro 10.2. Initial ligand conformations are minimised and sampled by MacroModel, which were then prepared LigPrep tool. Hydrogen atoms were added while the ionisation and tautomeric states of ligands at a target pH of 7.0 ± 2.0 were generated using Epik. The 3D geometry of each structure was optimised by OPLS-3 force field. Glide in extra precision (XP) mode was used in docking. Molecular mechanics-generalized Born surface area (MM-GBSA) method in Prime was used for rescoring the docked pose of ligand. For each compound, the pose with the lowest score was retained.

Cocrystallization and data collection

Protein-inhibitor complex crystal was prepared by co-crystallization methods. Briefly, the crystal of SmChiA-6a crystal complex was obtained in a solution consisting of 5 mM 6a, 5% (v/v) DMSO, 0.75 M sodium citrate (pH 7.2) and 20% (v/v) methanol by the vapour method37. The crystals were soaked for 10 s in a reservoir solution containing 20% (v/v) glycerol as a cryoprotection reagent, and subsequently flash-cooled in liquid nitrogen. X-ray diffraction data of the complexes were collected on the BL-19U1 at Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility in China. The diffraction data of the complexes were processed using the HKL-3000 package.

Structure determination and refinement

The structures of SmChiA-6a was solved by molecular replacement with Phaser38 using the structure of free SmChiA as a model (PDB entry 2WLZ). The PHENIX suite of programs39 was used for structure refinement. Coot was used for manually building and extending the molecular models40. The stereo chemical quality of the models was checked by PROCHECK41. The coordinates of SmChiA-6a were deposited in the Protein Data Bank as entry 7FD6. The structural figures were generated using the PyMOL program. The statistics for the diffraction data and the structure refinement are summarised in Table 2.

Table 2.

X-ray data collection and structure-refinement statistics of the complex SmChiA-6a.

| SmChiA-6a | |

|---|---|

| Protein Data Bank entry | 7FD6 |

| Space group | C2221 |

| Unit-cell parameters | |

| a (Å) | 132.525 |

| b (Å) | 202.186 |

| c (Å) | 59.43 |

| α (°) | 90 |

| β (°) | 90 |

| γ (°) | 90 |

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.97776 |

| Temperature (K) | 100 |

| Resolution (Å) | 34.92–1.786 (1.85–1.786) |

| Unique reflections | 74412 |

| Observed reflections | 117961 |

| Rmerge | 0.03271 (0.01386) |

| Average multiplicity | 1.6 (1.0) |

| <σ(I)> | 14.76 (3.08) |

| Completeness (%) | 98 (82) |

| R/Rfree | 0.1748/ 0.1917 |

| Protein atoms | 4124 |

| Water molecules | 678 |

| Other atoms | 28 |

| R.M.S. deviation from ideal | |

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.004 |

| Bond angles (°) | 0.682 |

| Wilson B factor (Å2) | 18.57 |

| Average B factor (Å2) | 23.32 |

| Protein atoms | 21.64 |

| Water molecules | 33.20 |

| Ligand molecules | 31.57 |

| Ramachandran plot (%) | |

| Favored | 99 |

| Allowed | 1.5 |

| Outliers | 0 |

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank the staff of BL19U1 beamlines at National Facility for Protein Science Shanghai (NFPS) and Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility, Shanghai, People’s Republic of China, for assistance during data collection.

Funding Statement

This work was financially supported by National Key Research and Development Program of China (No. 2022YFD1700200), the Shenzhen Science and Technology Program (No. KQTD20180411143628272) and the Key Project of the Shanghai Science and Technology Committee (No.18DZ1112703).

Disclosure statement

The authors claim no conflict of interest about this work.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- 1.Chen W, Yang Q.. Development of novel pesticides targeting insect chitinases: a minireview and perspective. J Agric Food Chem. 2020;68(16):4559–4565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhu B, Lou M-M, Xie G-L, Zhang G-Q, Zhou X-P, Li B, Jin G-L.. Horizontal gene transfer in silkworm, bombyx mori. BMC Genom. 2011;12(1):248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu T, Chen L, Zhou Y, Jiang X, Duan Y, Yang Q.. Structure, catalysis, and inhibition of OfChi-h, the lepidoptera-exclusive insect chitinase. J Biol Chem. 2017;292(6):2080–2088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lu Q, Xie H, Qu M, Liu T, Yang Q.. Group h chitinase: a molecular target for the development of lepidopteran-specific insecticides. J Agric Food Chem. 2023;71(15):5944–5952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen W, Jiang X, Yang Q.. Glycoside hydrolase family 18 chitinases: the known and the unknown. Biotechnol Adv. 2020;43:107553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davies GJ, Wilson KS, Henrissat B.. Nomenclature for sugar-binding subsites in glycosyl hydrolases. Biochem J. 1997;321 (Pt 2)(Pt 2):557–559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen L, Liu T, Duan Y, Lu X, Yang Q.. Microbial secondary metabolite, phlegmacin B1, as a novel inhibitor of insect chitinolytic enzymes. J Agric Food Chem. 2017;65(19):3851–3857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lu Q, Xu L, Liu L, Zhou Y, Liu T, Song Y, Ju J, Yang Q.. Lynamicin B is a potential pesticide by acting as a lepidoptera-exclusive chitinase inhibitor. J Agric Food Chem. 2021;69(47):14086–14091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Qi H, Jiang X, Ding Y, Liu T, Yang Q.. Discovery of kasugamycin as a potent inhibitor of glycoside hydrolase family 18 chitinases. Front Mol Biosci. 2021;8:640356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jiang X, Kumar A, Motomura Y, Liu T, Zhou Y, Moro K, Zhang KYJ, Yang Q.. A series of compounds bearing a dipyrido-pyrimidine scaffold acting as novel human and insect pest chitinase inhibitors. J Med Chem. 2020;63(3):987–1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yuan P, Jiang X, Wang S, Shao X, Yang Q, Qian X.. X-ray structure and molecular docking guided discovery of novel chitinase inhibitors with a scaffold of dipyridopyrimidine-3-carboxamide. J Agric Food Chem. 2020;68(47):13584–13593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhu L, Chen L, Shao X, Cheng J, Yang Q, Qian X.. Novel inhibitors of an insect pest chitinase: design and optimization of 9-O-aromatic and heterocyclic esters of berberine. J Agric Food Chem. 2021;69(27):7526–7533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen L, Zhu L, Chen J, Chen W, Qian X, Yang Q.. Crystal structure-guided design of berberine-based novel chitinase inhibitors. J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem. 2020;35(1):1937–1943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li W, Ding Y, Qi H, Liu T, Yang Q.. Discovery of natural products as multitarget inhibitors of insect chitinolytic enzymes through high-throughput screening. J Agric Food Chem. 2021;69(37):10830–10837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ding Y, Chen S, Liu H, Liu T, Yang Q.. Discovery of multitarget inhibitors against insect chitinolytic enzymes via machine learning-based virtual screening. J Agric Food Chem. 2023;71(23):8769–8777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pang Z, Xie H, Jiang X, He Y, Liang J, Ding Y, Liu T.. Discovery of sennidin B as a potent multitarget inhibitor of insect chitinolytic enzymes. J Agric Food Chem. 2025;73(19):11661–11669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zou R, Li X, Jiang X, Shi D, Han Q, Duan H, Yang Q.. Novel butenolide derivatives as dual-chitinase inhibitors to arrest the growth and development of the Asian corn borer. J Agric Food Chem. 2024;72(9):5036–5046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Han Q, Zi Y-J, Feng T-Y, Wu N, Zou R-X, Zhang J-Y, Zhang R-L, Yang Q, Duan H-X.. Vital residues-orientated rational design of butenolide inhibitors targeting of ChtI. Med Chem Res. 2024;33(5):740–747. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhao Z, Chen W, Dong Y, Yang Q, Lu H, Zhang J.. Discovery of potent N-methylcarbamoylguanidino insect growth regulators targeting OfChtI and OfChi-h. J Agric Food Chem. 2023;71(33):12431–12439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhao Z, Chen W, Wang S, Dong Y, Yang Q, Zhang J.. Rational design of N-methylcarbamoylguanidinyl derivatives as highly potent dual-target chitin hydrolase inhibitors for retarding growth of pest insects. J Agric Food Chem. 2023;71(6):2817–2826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhao Z, Li F, Chen W, Yang Q, Lu H, Zhang J.. Discovery of aromatic 2-(3-(methylcarbamoyl) guanidino)-N-aylacetamides as highly potent chitinase inhibitors. Bioorg Med Chem. 2023;80:117172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liang P, Li J, Chen W, Zhou H, Lai X, Li J, Xu Z, Yang Q, Zhang J.. Design of inhibitors targeting chitin-degrading enzymes by bioisostere substitutions and scaffold hopping for selective control of ostrinia furnacalis. J Agric Food Chem. 2024;72(19):10794–10804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fang Z, Song Y, Zhan P, Zhang Q, Liu X.. Conformational restriction: an effective tactic in ‘follow-on’-based drug discovery. Future Med Chem. 2014;6(8):885–901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sandner A, Hüfner-Wulsdorf T, Heine A, Steinmetzer T, Klebe G.. Strategies for late-stage optimization: profiling thermodynamics by preorganization and salt bridge shielding. J Med Chem. 2019;62(21):9753–9771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schwizer D, Patton JT, Cutting B, Smieško M, Wagner B, Kato A, Weckerle C, Binder FPC, Rabbani S, Schwardt O, et al. Pre-organization of the core structure of E-selectin antagonists. Chemistry. 2012;18(5):1342–1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Riel AMS, Decato DA, Sun J, Massena CJ, Jessop MJ, Berryman OB.. The intramolecular hydrogen bonded–halogen bond: a new strategy for preorganization and enhanced binding. Chem Sci. 2018;9(26):5828–5836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McConnell AJ, Beer PD.. Heteroditopic receptors for ion-pair recognition. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2012;51(21):5052–5061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ikegashira K, Oka T, Hirashima S, Noji S, Yamanaka H, Hara Y, Adachi T, Tsuruha J-I, Doi S, Hase Y, et al. Discovery of conformationally constrained tetracyclic compounds as potent hepatitis C virus NS5B RNA polymerase inhibitors. J Med Chem. 2006;49(24):6950–6953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Benfield AP, Teresk MG, Plake HR, DeLorbe JE, Millspaugh LE, Martin SF.. Ligand preorganization may be accompanied by entropic penalties in protein–ligand interactions. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2006;45(41):6830–6835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Borsari C, Rageot D, Dall’Asen A, Bohnacker T, Melone A, Sele AM, Jackson E, Langlois J-B, Beaufils F, Hebeisen P, et al. A conformational restriction strategy for the identification of a highly selective pyrimido-pyrrolo-oxazine mTOR inhibitor. J Med Chem. 2019;62(18):8609–8630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang K, Herdtweck E, Dömling A.. Cyanoacetamides (IV): versatile one-pot route to 2-quinoline-3-carboxamides. ACS Comb Sci. 2012;14(5):316–322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gavala ML, Kelly EaB, Esnault S, Kukreja S, Evans MD, Bertics PJ, Chupp GL, Jarjour NN.. Segmental allergen challenge enhances chitinase activity and levels of CCL18 in mild atopic asthma. Clin Exp Allergy. 2013;43(2):187–197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Artieda M, Cenarro A, Gañán A, Jericó I, Gonzalvo C, Casado JM, Vitoria I, Puzo J, Pocoví M, Civeira F.. Serum chitotriosidase activity is increased in subjects with atherosclerosis disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23(9):1645–1652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Boot RG, Hollak CEM, Verhoek M, Alberts C, Jonkers RE, Aerts JM.. Plasma chitotriosidase and CCL18 as surrogate markers for granulomatous macrophages in sarcoidosis. Clin Chim Acta. 2010;411(1–2):31–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen L, Zhou Y, Qu M, Zhao Y, Yang Q.. Fully deacetylated chitooligosaccharides act as efficient glycoside hydrolase family 18 chitinase inhibitors. J Biol Chem. 2014;289(25):17932–17940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Harder E, Damm W, Maple J, Wu C, Reboul M, Xiang JY, Wang L, Lupyan D, Dahlgren MK, Knight JL, et al. OPLS3: a force field providing broad coverage of drug-like small molecules and proteins. J Chem Theory Comput. 2016;12(1):281–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Papanikolau Y, Prag G, Tavlas G, Vorgias CE, Oppenheim AB, Petratos K.. High resolution structural analyses of mutant chitinase a complexes with substrates provide new insight into the mechanism of catalysis. Biochemistry. 2001;40(38):11338–11343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McCoy AJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Adams PD, Winn MD, Storoni LC, Read RJ.. Phaser crystallographic software. J Appl Crystallogr. 2007;40(Pt 4):658–674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Adams PD, Afonine PV, Bunkóczi G, Chen VB, Davis IW, Echols N, Headd JJ, Hung L-W, Kapral GJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, et al. PHENIX: a comprehensive python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66(Pt 2):213–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Emsley P, Cowtan K.. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60(Pt 12 Pt 1):2126–2132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Laskowski RA, MacArthur MW, Moss DS, Thornton JM.. PROCHECK: a program to check the stereochemical quality of protein structures. J Appl Crystallogr. 1993;26(2):283–291. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.