Abstract

Objective

Anatomical variations in the sacrococcygeal region can lead to complications such as accidental dural puncture during caudal block. This study aimed to determine the prevalence of sacrococcygeal anatomical variations using ultrasonography and to evaluate the necessity of ultrasound guidance in sacral block procedures.

Methods

Ultrasound findings of sacrococcygeal anatomy were validated against magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). A detailed ultrasound protocol was subsequently applied to assess sacrococcygeal anatomy in pediatric patients.

Results

Ultrasound and MRI demonstrated strong concordance in evaluating sacrococcygeal anatomy. The most common anatomical variation was a low-lying dural sac (16.2%), followed by incomplete sacral cornua (4.9%). The dural sac termination level was inversely associated with age (odds ratio: 0.996, 95% CI: 0.945–0.987; p < 0.001). Other variations included abnormal coccyx curvature (4.3%), sacral skewness (3.8%), and sacral hiatus atresia (1.1%), with no pathological abnormalities detected.

Conclusion

Comprehensive ultrasound scanning effectively identifies anatomical variations in the sacrococcygeal region of pediatric patients, which are highly prevalent. Routine preprocedural ultrasound examinations and ultrasound guidance during caudal block procedures are strongly recommended to enhance safety and accuracy.

Keywords: Caudal block, ultrasound, magnetic resonance imaging, sacrococcygeal anatomical variations

Introduction

Caudal block is a widely used regional anesthetic technique for intraoperative and postoperative pain management in pediatric patients [1,2]. The conventional landmark-based approach relies on accurate identification of the sacral hiatus and precise needle placement. Despite achieving an overall success rate of 96%, up to 25% of pediatric patients require multiple attempts [3]. Anatomical variations, including complete absence of the sacral hiatus, asymmetry of the sacral cornua (SC), and low-lying dural sacs (DS), can complicate the traditional technique in children [4]. Additionally, the small, narrow sacral hiatus and reduced diameter of the sacral canal in pediatric patients pose significant challenges, increasing the likelihood of failed injections. Repeated attempts can lead to complications such as vascular puncture, local anesthetic toxicity, and dural puncture [5]. Thus, a comprehensive understanding of sacrococcygeal anatomy is crucial to improving success rates and minimizing associated risks.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is recognized for its superior ability to provide detailed imaging of the sacrococcygeal region [6]. However, MRI is time-consuming, costly, and impractical in routine clinical settings. Ultrasound (US) has emerged as a promising alternative, particularly in infants and young children, where incomplete bone ossification creates a natural acoustic window for imaging neuraxial structures [7,8]. Previous studies have shown that ultrasound-guided caudal block improves both safety and efficacy by providing real-time guidance [9]. Despite these benefits, the utilization of ultrasound for pediatric caudal blocks remains limited, with reported adoption rates as low as 3% [5]. This underuse may stem from ongoing debates about the necessity of ultrasound in routine practice.

Anatomical variations of the sacrum are not uncommon and can significantly impact the success and safety of caudal blocks. Comprehensive preprocedural evaluation can help identify patients at higher risk of challenging punctures and reduce procedural complications. To address this, we developed a sequential ultrasound scanning protocol, extending from the sacrum to the fifth lumbar vertebra (L5), for a thorough assessment of sacrococcygeal anatomy in pediatric patients. This approach enables the detection of abnormalities that may be missed during palpation-based techniques. To further explore the prevalence of sacral anatomical variations and underscore the need for ultrasound guidance during caudal block, we conducted a large-scale observational study involving children under 84 months of age at our institution. Despite the increasing use of ultrasound in regional anesthesia, there is a lack of large-scale, systematically validated studies examining sacrococcygeal anatomical variations specifically in children under 84 months. Existing studies often suffer from limited age stratification, small sample sizes, or inadequate imaging comparisons, which this study aims to address.

Materials and methods

Patients

Trial design

This prospective observational trial was performed at the First Affiliated Hospital of University of Science and Technology of China (USTC). From August 2020 to July 2024, 805 pediatric patients participated in the study. This study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee (2020KY-24) of the First Affiliated Hospital of USTC and was performed in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration. Informed consent was signed by parents or guardians.

Participants

Inclusion criteria were age from 0 to 84 months, both genders, and voluntary participation and cooperation of children and guardians. Part I: The child was scheduled for MRI examination, including the intact lumbosacral caudal structure. Part II: The child was hospitalized for surgery under general anesthesia.

The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Family members were unable to understand the study process or were not cooperative; (2) The examination area was unsuitable for ultrasound examination, such as trauma, infection, or bandages on the body surface; (3) the child was unable to complete the position.

Part I. Consistency evaluation of sacrococcygeal anatomical structure between MRI and ultrasound

MRI and ultrasound protocol

At the very beginning, ten pediatric patients were arranged to undergo both MRI and ultrasonic examinations of sacrococcygeal section. To achieve motionless MRI imaging, all participants received sedation with oral chloral hydrate (30–50 mg/kg). Those with inadequate sedation were given a rescue dose of oral chloral hydrate (10–20 mg/kg), maintaining a total cumulative dose not exceeding 1,000 mg. Ear protectors were utilized to minimize auditory distraction and prevent potential damage from MRI noise. Throughout the procedure, all participants were under monitoring by an anesthetist. Lumbosacral MRI was performed on a Siemens 1.5-Tesla unit. Patients were scanned in supine position, according to standard imaging and positioning protocols. T1-weighted images and T2-weighted images were obtained. Slice thickness was 4 mm with a 1-mm interslice gap for all sequences [10].

Ultrasound images were obtained using a high-frequency linear US probe (model LH15-6) of the ultrasonic diagnostic system (Wisonic, 20162230883). The child was placed in the lateral position with knees as close to the abdomen as possible. And then, the morphology of sacrococcygeal vertebrae was evaluated by the following stepwise approach, including sequential transverse, longitudinal, and oblique sagittal scans (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Location and movement of the ultrasound probe for sacral imaging. (A) Schematic diagram of short-axis scanning: the probe is placed horizontally at the sacral hiatus and slid continuously from S5 to L5 along the arrow. (B) Schematic of longitudinal scanning: the probe is rotated 90 degrees and moved cephalad from S5 to S1. (C) Schematic of paracentral scanning: the probe is positioned 0.5–1 cm to the left/right of the midline and tilted towards the midline for paracentral imaging. L5, the fifth lumbar vertebra; S1, the first sacral vertebra; S5, the fifth sacral vertebra.

The probe was placed transversely at the midline close to the sacral cornua to obtain a transverse view of the sacral hiatus, known as the ‘frog sign’.

Ultrasound images from the fifth sacral vertebra (S5) to L5 in transverse planes were then obtained by sliding the ultrasound probe cephalad.

At the level of S5 again, the probe was rotated 90 degrees to acquire a longitudinal view of the sacral hiatus.

The probe was moved towards coccyx to observe tailbone curvature and then slid along the long axis plane until the first sacral vertebra (S1) for additional information about the entire sacrum.

After completing the longitudinal scan at S1 level, the probe sensor was shifted 0.5–1 cm on either side of body and tilted toward the midline to obtain clear paramedian approach image.

The probe was moved caudally until the termination of the dural sac was identified.

Consistency analysis of ultrasound and MRI images

The imaging, including the morphology of sacrococcygeal vertebrae, important structures of the spinal cord and associated anomalies, were then assessed by reviewing the ultrasound and MRI images (Figure 2). Before project initiation, all participants in the consistency analysis received standardized training to define uniform criteria, ensuring consistent interpretation of imaging results. Simulated scoring with identical images was performed post-training to confirm inter-rater agreement.

Figure 2.

Representative MRI and ultrasound images. Normal spinal MRI (A) and ultrasonography (B–D) in a 2-year-old child. The termination of the dural sac is marked by a red arrow. S1, the first sacral vertebra; S2, the second sacral vertebra; S3, the third sacral vertebra; S4, the fourth sacral vertebra; S5, the fifth sacral vertebra.

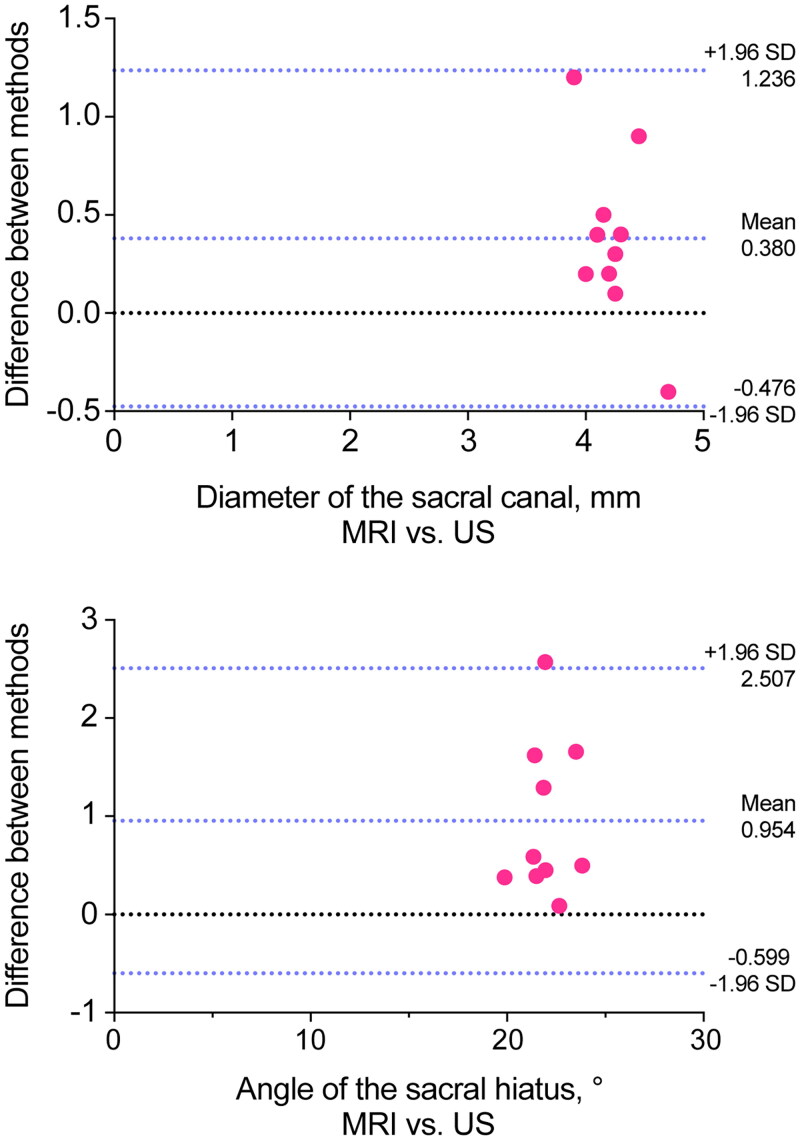

To investigate the consistency of the qualitative data from sacrococcygeal MRI and ultrasound, the abnormal fusion of sacral lamina, the absence of the sacral cornu and sacral hiatus were also shown in ultrasound and MRI. Consistency evaluation, such as Bland-Altman analysis, were used to quantify agreement of the anatomical structure between ultrasound and MRI. We calculated the diameter of the sacral canal at the apex of the hiatus, and the optimal angle of the sacral hiatus for evaluation the changes of sacral canal morphology. At the same time, confirming the termination level of the dural sac was important to avoid cord injury due to the needle entry into the dural sac.

Part II. Evaluation of the efficacy of US in detecting abnormal anatomical structures of sacrococcygeal region

Images were obtained by examining the sacrococcygeal region in all children using the ultrasonography method described in Part I. The primary outcome measures were the anatomical variation rate and type including absence of the sacral cornu and sacral hiatus, low-lying dural sacs and abnormal fusion of sacral lamina. Secondly, morphological features including the average height of sacral cornu, the distance between bilateral sacral cornua, diameter of the sacral canal at the apex of the hiatus and the terminal level of dural sac were collected depending on the age group. In addition, the following indicators were measured in turn. In transverse plane–distance between skin and sacral cornua, mean height and bilateral distance between sacral cornua, midpoint markings on each plane joined together for comparison with midline parallelism. In longitudinal plane–evaluation of coccyx and sacrum curvatures, measurement included the diameter of the sacral canal at the apex of the hiatus, the optimal angle for needle insertion. The indicators were shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Ultrasound images showing measurement indicators. (A) Transverse plane: a, distance between skin and sacral cornu; b, height of sacral cornu; c, distance between bilateral sacral cornua; d, diameter of the sacral canal at the apex of the hiatus. (B) Longitudinal plane: e, angle of the sacral hiatus. S3, the third sacral vertebra; S4, the fourth sacral vertebra; S5, the fifth sacral vertebra.

The optimal angle was defined as needle positioning parallel to the sacral base when entering the midpoint. In contrast to the continuous, irregular, high-echo wavy line observed at the midline of the sacral surface, cases of incomplete fusion of the sacral midline crest exhibited interrupted hyperechoic bone lines and reduced penetration of the ultrasound beam. Additionally, the low-lying dural sacs were defined as dural sac terminating below the second sacral vertebra (S2). Sacral skewness was defined as a developmental asymmetry of the sacrum in which the middle sagittal line be skewed to the right or left [11].

Statistical methods

Preliminary experiments revealed an anatomical variation rate of 20% in the sacrococcygeal region among children. Based on this estimate, a sample size of 683 cases was calculated to achieve 80% power at a 5% significance level. Accounting for a 10% dropout rate, the final sample size was set at 795 cases.

The normality of data distribution was evaluated using QQ-plots. Quantitative data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) for normally distributed data or as medians with interquartile range (IQR) for skewed data. Categorical data were presented as percentages. Agreements between indicators obtained from different methods were evaluated using the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) and Bland-Altman analysis.

For comparisons of numerical data, Kruskal-Wallis test, or analysis of variance (ANOVA) were applied, depending on the distribution of the data. Categorical variables were compared using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. Logistic regression analysis was conducted to evaluate correlations between variables. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (version 25.0), and a p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

In Part I, ultrasonic images were obtained within one week after performing MRI scans on ten pediatric patients. Seven boys and three girls aged between 15 and 73 months were included. The sacral lamina fusion, or absence of the sacral cornu or sacral hiatus, was not reported in these patients either on MRI or ultrasound. There was a high degree of concordance in sacral canal morphology assessment by MRI and ultrasound. Bland-Altman plots showed that the mean bias of diameter of the distance between bilateral sacral cornua, and the optimal angle of the sacral hiatus between MRI or ultrasound were 0.420 and 0.954, with the limit of agreement being −0.416 to 1.256 (t = 3.115, p < 0.01) and 0.387 to 1.521 (t = 3.807, p < 0.01), which showed good agreement (Figure 4). In addition, the two methods demonstrated strong agreement in examining the termination level of the dural sac (ICC: 0.816; 95% CI: 0.421, 0.951). Based on the above data, the accuracy of the US measurement was sufficient for the current investigation.

Figure 4.

Bland-Altman plots demonstrating agreement between MRI and ultrasound. (A) Diameter of the sacral canal. (B) Optimal angle of the sacral hiatus.

A total of 795 children participated in the study of Part II, including 88 cases aged between 0 and 12 months, 299 cases aged between 13 and 36 months, and 408 cases aged between 37 and 84 months. All the pediatric patients completed the study. The basic information of the enrolled pediatric patients was listed according to different age groups in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of participating children.

| ≤12 m | 13–36 m | 37–84 m | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 88 | 299 | 408 | 795 |

| Sex, n | ||||

| Male | 68 (77.27%) | 249 (83.28%) | 287 (70.34%) | 604 (75.97%) |

| Female | 20 (22.37%) | 50 (16.72%) | 121 (29.65%) | 191 (24.03%) |

| Age, month | 8.3 (7.0–12.0) | 22.0 (18.0–29.0) | 55.0 (45.0–66.0) | 38.0 (20.0–56.0) |

| Height, cm | 72.0 (68.0,75.0) | 88.0 (81.0, 92.0) | 110.0 (103.0, 116.0) | 98.0 (84.0, 110.0) |

| Weight, kg | 9.5 (8.5, 11.0) | 13.0 (11.0, 14.0) | 19.0 (17.0, 21.5) | 15.0 (12.0, 19.0) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 18.5 (17.0, 19.7) | 16.7 (15.6, 18.1) | 15.8 (14.6, 17.1) | 16.3 (15.2,17.9) |

In the study, 241 pediatric cases were found to have anatomical variations, and 15 of them had more than two abnormalities. The termination level of dural sac below S2 was observed in 129 cases, indicating a variation rate of 16.2%, and this decline became more pronounced with younger age. The incidence of incomplete sacral cornua, abnormal curvature of the coccyx and sacral skewness were 4.91%, 4.28%, 3.77%, respectively. While sacral hiatus atresia were present in 1.13% of patients. The anatomical variations of the sacral canal in the three age groups were shown in Table 2 and the representative images were available in the Supplementary Figures 1–5.

Table 2.

Distribution of anatomical variations of the sacral canal in the three age groups.

| Anatomical variation | Total | ≤12 m n = 88 |

13–36 m n = 299 |

37–84 m n = 408 |

χ2/Fisher | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sacral hiatus atresia, n (%) | 9 (1.13%) | 1 (1.14%) | 4 (1.34%) | 4 (0.98%) | 0.667 | 0.756 |

| Sacral cornu absence, n (%) | 39 (4.91%) | 5 (5.68%) | 15 (5.02%) | 19 (4.66%) | 0.18 | 0.916 |

| Sacral skewness, n (%) | 30 (3.77%) | 6 (6.82%) | 8 (2.68%) | 16 (3.92%) | 3.24 | 0.198 |

| Low-lying dural sacs, n (%) | 129 (16.23%) | 17 (19.32%) | 73 (24.41%) | 39 (9.56%) | 28.71 | <0.001 |

| Abnormal coccyx curvature, n (%) | 34 (4.28%) | 6 (6.82%) | 11 (3.70%) | 17 (4.17%) | 2.03 | 0.363 |

Note: χ2/Fisher denotes χ2 statistic for the Chi-square test or p-value for Fisher’s exact tests (used when expected cell frequencies were <5).

The present study utilized logistic regression analysis to assess the effect of gender, age, height, weight and BMI on the termination level of the dural sac in pediatric patients. The results revealed that the termination level of dural sac was negatively correlated with age (OR 0.966, 95% CI 0.945–0.987, p < 0.001), but not with gender (z = 1.825, p = 0.068), height (z = 0.777, p = 0.437), weight (z = −1.592, p = 0.111) and BMI (z = 0.765, p = 0.444).

The termination level of dural sac moved upward with age, with the vast majority terminating at the S2 level. The prevalence of fusion of S2 or the third sacral vertebra (S3) increased with age, as shown in Table 3. There was no significant difference in the localization of the sacral hiatus apex among the age groups. The distance between skin and the sacral cornua and the average height of sacral cornu in children aged 37–84 months were found to be higher than those younger than 36 months. However, the angle of the sacral hiatus and diameter of the sacral canal at the apex of the hiatus didn’t change in the same way. Acoustic window score decreased with age. The results are presented in Table 4.

Table 3.

Anatomy of sacral canal in children.

| ≤12 m n = 88 |

13–36 m n = 299 |

37–84 m n = 408 |

H-statistic/χ2 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The localisation of the sacral hiatus apex, S | 3.48 ± 0.63 | 3.46 ± 0.59 | 3.48 ± 0.61 | 0.05 | 0.949 |

| Vertebral plane of dural sac terminal, S | 2.23 ± 0.51 | 2.16 ± 0.50 | 1.99 ± 0.53 | 18.45 | <0.0001 |

| Number of S2 lamina fusion cases, n | 22 (25.00%) | 74 (24.75%) | 190 (46.57%) | 40.21 | <0.0001 |

| Number of S3 lamina fusion cases, n | 12 (13.64%) | 43 (14.38%) | 112 (78.94%) | 20.69 | <0.001 |

Note: H-statistic represents the Kruskal-Wallis test statistic. χ2 denotes χ2 statistic for the Chi-square test.

Table 4.

Measurement values related to sacral canal structures.

| ≤12 m n = 88 |

13–36 m n = 299 |

37–84 m n = 408 |

F-statistic/H-statistic | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Distance between skin and sacral cornu, mm | 5.3 (4.7,5.9) | 5.4 (4.7,6.1) | 5.7 (5.0,6.4) | 14.54 | 0.001 |

| Average height of sacral cornu, mm | 5.2 (4.7,5.8) | 5.4 (4.7,6.1) | 5.7 (5.0,6.5) | 19.94 | <0.001 |

| Distance between bilateral sacral cornu, mm | 10.9 (9.7,12.3) | 11.9 (10.1,13.4) | 12.2 (10.6,13.8) | 22.08 | <0.001 |

| Angle of the sacral hiatus, ° | 19.8 (15.6,24.5) | 20.1 (17.1,24.1) | 20.2 (17.2,25.0) | 4.01 | 0.135 |

| Diameter of the sacral canal at the apex of the hiatus, mm | 4.2 (2.3,5.7) | 4.2 (3.3,5.3) | 4.2 (3.2,5.5) | 2.25 | 0.325 |

Note: H-statistic represents the Kruskal-Wallis test statistic. F-statistic represents the F statistic from analysis of variance (ANOVA).

Discussion

The presence of abnormal sacrococcygeal anatomy presents significant challenges for caudal epidural anesthesia in pediatric patients. This study developed a comprehensive ultrasound scanning protocol to systematically evaluate sacral canal morphology and investigate the prevalence of anatomical variability in 795 pediatric patients under 84 months of age. Anatomical variations were observed in 30.31% of cases, with multiple abnormalities in 1.89%. These findings provide valuable anatomical insights for clinical practice.

Before this study, we used ultrasound to scan the sacrococcygeal structure from infants to adults and found that the acoustic window was highly likely to be severely affected in patients over 84 months, which was consistent with the literature [7]. Although numerous studies on pediatric ultrasound have included children over 84 months of age, their primary focus has been on evaluating the feasibility of the technique rather than assessing the higher segments of the sacral canal [4,12–14]. This oversight presents potential puncture risks, particularly in younger infants. Thus, we selected children aged 0–84 months for this study.

The success of caudal block relies on accurate identification of the sacral hiatus, traditionally achieved by palpating bilateral sacral cornua. However, even experienced clinicians report difficulties locating the sacral hiatus in 11% of children under seven years of age [15]. Ultrasound can identify sacral cornua that are unpalpable [13]. In this study, unilateral sacral cornu absence was observed in 2.53% of cases and bilateral absence in 2.38%, lower than previous studies reporting rates of up to 24.5% [16]. Discrepancies may result from differences in measurement methods, sample sizes, or reliance on cadaveric versus imaging data. Additionally, complete sacral hiatus atresia was identified in 1.13% of cases, rendering caudal block unfeasible [17]. Ultrasound imaging facilitates safer caudal epidural blocks and reduces complications from repeated punctures.

The termination level of the dural sac, which typically moves cranially with age, was below S2 in 16.2% of cases, below S3 in 15.3%, and below the fourth sacral vertebra (S4) in 0.25%. These findings highlight the risk of inadvertent dural puncture, particularly in younger patients [18–20]. Spinal anesthesia in this population requires careful needle placement, avoiding cord injury. Furthermore, changes in body position can alter dural sac termination level, making preoperative ultrasound evaluation critical [21].

Sacral hiatus anatomical variations also impact caudal block success. Inverted ‘U’ or ‘V’ shapes are common, but irregular or dumbbell-shaped hiatuses must be considered [22]. Variability in the distance between the sacral hiatus apex and the dural sac termination can complicate neuraxial access [23,24]. Our findings, consistent with previous studies [1,25,26], emphasize the importance of measuring this distance preoperatively to account for individual differences.

The anteroposterior diameter and curvature of the sacral canal are predictive of puncture difficulty. In this study, the mean diameter at the hiatus apex was 4.2 mm, with 2.2% of cases measuring <2 mm, indicative of higher puncture difficulty [27]. Additionally, the optimal puncture angle was 20.2°, aligning with previous findings of 21° [28]. For patients with a diameter <2 mm or an angle <14°, ultrasound-guided puncture or alternative anesthesia plans are recommended.

Other anatomical abnormalities, such as scoliosis or skin changes (e.g. dimples, sinuses, or hair tufts), should be ruled out prior to caudal block. Such features may indicate underlying conditions like spina bifida occulta or tethered cord syndrome. Thorough preoperative ultrasound evaluation is essential to ensure procedural safety and identify contraindications.

A potential limitation is the relatively small sample size (n = 10) of the MRI-ultrasound validation cohort, which might be considered to introduce bias. However, such limited sample sizes are frequently encountered in prior pediatric or dedicated volunteer studies [29–31], which may be due to feasibility, ethics, and technical constraints. Correspondingly, given our participant population (children aged 0–84 months), rigorous ethical safeguards were implemented throughout the experimental design. Furthermore, Bland-Altman analysis was employed because it can visually suggest systematic bias or trends even in smaller samples. Critically, although the limited sample size in Part I resulted in a relatively wide 95% confidence interval, the magnitude of this variation falls within a clinically acceptable range and does not represent a meaningful difference in clinical interpretation.

This study has other limitations. As a single-center trial in a tertiary hospital, findings may lack generalizability, necessitating larger, multi-center studies. Additionally, the exclusive inclusion of pediatric patients undergoing surgery, without healthy volunteers, raises questions about the association between medical conditions and sacral canal variations. The study population, composed solely of Han Chinese children, limits the assessment of racial variation. Lastly, the gender imbalance, although not statistically significant, may introduce potential bias.

Conclusion

Sacrococcygeal ultrasonography effectively identifies anatomical variations in children under 84 months, revealing a higher prevalence than previously anticipated. For successful and safe caudal block procedures, ultrasound guidance is strongly recommended. At a minimum, a meticulous preoperative ultrasound scan of the sacrococcygeal region should be routinely performed. Furthermore, preprocedural imaging can proactively identify challenging cases and assist anesthesiologists in planning optimal puncture trajectories, ultimately enhancing procedural accuracy and reducing the risk of complications.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Yin-guang Fan (Anhui Medical University, Department of Epidemiology and Health Statistics) for statistical advice for this manuscript.

Funding Statement

This study has received funding by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [grant number 82301391], and USTC Research Funds of the Double First-Class Initiative [grant number YD9110002065].

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Professor Wei Gao, upon reasonable request.

References

- 1.Wiegele M, Marhofer P, Lönnqvist P-A.. Caudal epidural blocks in paediatric patients: a review and practical considerations. Br J Anaesth. 2019;122(4):509–517. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2018.11.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tian Y, Li S, Yang F, et al. The median effective concentration of ropivacaine for ultrasound-guided caudal block in children: a dose-finding study. J Anesth. 2024;38(2):179–184. doi: 10.1007/s00540-023-03294-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dalens B, Hasnaoui A.. Caudal anesthesia in pediatric surgery: success rate and adverse effects in 750 consecutive patients. Anesth Analg. 1989;68(2):83–89. (Print):doi: 10.1213/00000539-198902000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee HJ, Min JY, Kim HI, et al. Measuring the depth of the caudal epidural space to prevent dural sac puncture during caudal block in children. Paediatr Anaesth. 2017;27(5):540–544. doi: 10.1111/pan.13083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Suresh S, Long J, Birmingham PK, et al. Are caudal blocks for pain control safe in children? An analysis of 18,650 caudal blocks from the pediatric regional anesthesia network (PRAN) database. Anesth Analg. 2015;120(1):151–156. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000000446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hresko AM, Hinchcliff EM, Deckey DG, et al. Developmental sacral morphology: MR study from infancy to skeletal maturity. Eur Spine J. 2020;29(5):1141–1146. doi: 10.1007/s00586-020-06350-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marhofer P, Bösenberg A, Sitzwohl C, et al. Pilot study of neuraxial imaging by ultrasound in infants and children. Paediatr Anaesth. 2005;15(8):671–676. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9592.2004.01521.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tsui BC, Suresh S.. Ultrasound imaging for regional anesthesia in infants, children, and adolescents: a review of current literature and its application in the practice of neuraxial blocks. Anesthesiology. 2010;112(3):719–728. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181c5e03a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yan T-T, Yang X-L, Wang S, et al. Application of continuous sacral block guided by ultrasound after comprehensive sacral canal scanning in children undergoing laparoscopic surgery: a prospective, randomized, double-blind study. J Pain Res. 2023;16:83–92. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S391501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Daher RT, Daher MT, Daher RT, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of the spine in a pediatric population: incidental findings. Radiol Bras. 2020;53(5):301–305. doi: 10.1590/0100-3984.2018.0099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu L-P, Li Y-K, Li Y-M, et al. Variable morphology of the sacrum in a Chinese population. Clin Anat. 2009;22(5):619–626. doi: 10.1002/ca.20809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adewale L, Dearlove O, Wilson B, et al. The caudal canal in children: a study using magnetic resonance imaging. Paediatr Anaesth. 2000;10(2):137–141. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9592.2000.00462.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Karaca O, Pinar HU, Gokmen Z, et al. Ultrasound-guided versus conventional caudal block in children: a prospective randomized study. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2019;29(6):533–538. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1676980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim H-J, Kim H, Lee S, et al. Reconsidering injection volume for caudal epidural block in young pediatric patients: a dynamic flow tracking experimental study. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2024;49(5):355–360. doi: 10.1136/rapm-2023-104409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Veyckemans 1 Ljvo F, Gouverneur JM.. Lessons from 1100 pediatric caudal blocks in a teaching hospital. Reg Anesth. 1992;17:119–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aggarwal A, Kaur H, Batra YK, et al. Anatomic consideration of caudal epidural space: a cadaver study. Clin Anat. 2009;22(6):730–737. doi: 10.1002/ca.20832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nastoulis E, Tsiptsios D, Chloropoulou P, et al. Morphological and morphometric features of sacral hiatus and its clinical significance in caudal epidural anaesthesia. Folia Morphol. 2023;82(3):603–614. doi: 10.5603/FM.a2022.0078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Herregods N, Anisau A, Schiettecatte E, et al. MRI in pediatric sacroiliitis, what radiologists should know. Pediatr Radiol. 2023;53(8):1576–1586. doi: 10.1007/s00247-023-05602-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim M-S, Han K-H, Kim EM, et al. The myth of the equiangular triangle for identification of sacral hiatus in children disproved by ultrasonography. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2013;38(3):243–247. doi: 10.1097/AAP.0b013e31828e8a1a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van Schoor AN, Bosman MC, Venter G, et al. Determining the extent of the dural sac for the performance of caudal epidural blocks in newborns. Paediatr Anaesth. 2018;28(10):852–856. doi: 10.1111/pan.13483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koo BN, Hong JY, Kim JE, et al. The effect of flexion on the level of termination of the dural sac in paediatric patients. Anaesthesia. 2009;64(10):1072–1076. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2009.06031.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Senoglu N, Senoglu M, Oksuz H, et al. Landmarks of the sacral hiatus for caudal epidural block: an anatomical study. Br J Anaesth. 2005;95(5):692–695. doi: 10.1093/bja/aei236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nasr AY. Clinical relevance of conus medullaris and dural sac termination level with special reference to sacral hiatus apex: anatomical and MRI radiologic study. Anat Sci Int. 2017;92(4):456–467. doi: 10.1007/s12565-016-0343-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aggarwal, Anjali, Aggarwal, Aditya, Sahni, Daisy, et al. Morphometry of sacral hiatus and its clinical relevance in caudal epidural block. Surg Radiol Anat 2009;31(10):793–800. doi: 10.1007/s00276-009-0529-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aggarwal A, Sahni D, Kaur H, et al. The caudal space in fetuses: an anatomical study. J Anesth. 2012;26(2):206–212. doi: 10.1007/s00540-011-1271-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cicekcibasi AE, Borazan H, Arıcan S, et al. Where is the apex of the sacral hiatus for caudal epidural block in the pediatric population? A radio-anatomic study. J Anesth. 2014;28(4):569–575. doi: 10.1007/s00540-013-1758-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim DH, Park JH, Lee SC.. Ultrasonographic evaluation of anatomic variations in the sacral hiatus. Spine. 2016;41(13):E759–E763. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000001448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Park JH, Koo BN, Kim JY, et al. Determination of the optimal angle for needle insertion during caudal block in children using ultrasound imaging. Anaesthesia. 2006;61(10):946–949. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2006.04795.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schwenzer NF, Schraml C, Müller M, et al. Pulmonary lesion assessment: comparison of whole-body hybrid MR/PET and PET/CT imaging–pilot study. Radiology. 2012;264(2):551–558. doi: 10.1148/radiol.12111942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Verhulst A, Hol M, Vreeken R, et al. Three-dimensional imaging of the face: a comparison between three different imaging modalities. Aesthet Surg J. 2018;38(6):579–585. doi: 10.1093/asj/sjx227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Toto L, Di Antonio L, Mastropasqua R, et al. Multimodal imaging of macular telangiectasia type 2: focus on vascular changes using optical coherence tomography angiography. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2016;57(9):Oct268–76. doi: 10.1167/iovs.15-18872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Professor Wei Gao, upon reasonable request.