Abstract

Chitosan is a cationic natural polymer composed of glucosamine and N-acetylglucosamine residues that are held together by a glycosidic bond. Chitosan has many excellent properties, including physicochemical properties, i.e., stability in the natural environment, chelation of metal ions, high sorption properties, biological properties such as biocompatibility and biological activity, ecological properties resulting from biodegradability, and physiological properties, which include non-toxicity, and economic affordability, and is used in various biomedical and industrial applications. The presented article highlights recent developments in chitosan-based formulations for the treatment of bacteria, viruses, cancer, or gastroesophageal reflux disease. Moreover, chitosan-derived biomaterials can also be used in regenerative medicine or food packaging to prevent contamination by pathogenic microorganisms. In summary, this is a valuable compilation in this emerging field that focuses on the biomedical application of chitosan-based biomaterials.

Keywords: Chitosan, Biomedical applications, Nanoparticles, Microparticles

Background

The concept of chitosan-based biomedical applications

Chitosan is the most abundant biopolymer with a linear aminopolysaccharide composed of glucosamine and N-acetylglucosamine residues that are held together by glycosidic bonds. It is insoluble in water and soluble in acids such as hydrochloric acid and acetic acid, and its solubility is influenced by the degree of deacetylation. Chitosan is typically extracted from shrimp and crab shells containing abundant calcium carbonate and chitin and can also be obtained from bacteria or fungi [7, 117, 133]. Studies indicate that crustacean shell waste comprises 30%–50% calcium carbonate and 20%–30% chitin by weight, with lobster shells having the highest chitin content of 60%–75% by weight [196]. The extraction process involves demineralization, deproteinization, and deacetylation stages, with demineralization performed first to increase the efficiency of the subsequent steps. The chemical structure of chitosan imparts remarkable biocompatibility and biodegradability [48]. Chitosan can be used for a wide range of applications, including antimicrobial therapies and wound healing, due to its ability to form films and hydrogels, anticoagulant activity and antioxidant activity, and biosorption of heavy metals. Chitosan has been used in various studies to develop carriers to deliver medical formulations, including drugs, plant extracts, microorganisms, and their soluble components. Furthermore, the chelating properties of chitosan make it suitable for wastewater treatment [17]. Under acidic conditions, the protonated amino groups of chitosan confer mucoadhesive properties, facilitating prolonged contact with biological surfaces and promoting drug absorption. Additionally, the versatility of chitosan is evident in its film-forming ability, controlled swelling behavior, and high surface area, which make it suitable for various drug, protein, bacteria, yeast, and microalgae delivery systems, such as nanoparticles Ø 1–1000 nm), microparticles (Ø 1–1000 µm), hydrogels, fibers, and membranes [25, 187, 287]. These formulations can be used externally, topically, or administered parenterally or orally [138, 201].

Chitosan nanoparticles can be produced via the ionic gelation method, exhibiting advantages such as increased stability and high penetration properties. They can also be produced by spray drying. Nanoparticles can be obtained under mild conditions without harmful organic solvents and retain the compound's bioactivity. The stability of chitosan nanoparticles is attributed to the ionic cross-linking of positively charged chitosan with polyanions, which transfer amino groups via protonation. The most commonly used polyanion for ionic cross-linking is tripolyphosphate (TPP), which is nontoxic. The ionic group of TPP interacts with the amine group of chitosan. Zhang et al. (2020) focused on the development characteristics of chitosan-based microspheres obtained via the spray drying technique. They discussed the importance of microspheres in controlled drug delivery because of their high surface area-to-volume ratio and ability to encapsulate hydrophilic and hydrophobic drugs [314]. This study emphasized the influence of various process parameters on the characteristics of the resulting microspheres, highlighting the biocompatibility, mucoadhesive properties, and controlled release capabilities of chitosan [314]. The important feature of chitosan is the ease of chemical modification through primary amino groups at C3 and hydroxyl groups at C3 and C6 in the ring. In drug delivery systems (DDSs), modifications affect the properties of the conjugate, such as its stability, hydrophobicity, pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics, solubility, durability, and biocompatibility [138]. However, graft copolymerization and cross-linking, including the formation of polyelectrolyte complexes, are among the reactions leading to extension of the polymer chain and increase in molecular weight; these reactions are also important in chemical methods for obtaining DDSs based on particles [218] and in the design of orally administered pH-sensitive carriers. Mucoadhesiveness is important in designing DDSs and vaccines targeted to mucous membranes [201]. The particle diameters in DDSs are also important in the action of chitosan because microscale particles interact with the mucin layer less easily than nanoscale particles, and it has been shown that particles with diameters less than 200 nm can be internalized into epithelial cells [84].

The mechanism and kinetics of a biological substance’s release from a carrier depend on its physicochemical properties, the polymer (matrix) preparation method, and the particles’ morphology, size, and density. This effect may also depend on the pH and polarity of the dissolution medium in which in vitro release studies are performed [107].

There are three main release mechanisms of cargo, which are preceded by swelling of the polymer due to the inflow of the solvent: (1) diffusion from the surface of the carrier, (2) diffusion through the matrix, and (3) release due to erosion and/or degradation of the polymer. Typically, the release of a substance occurs via a combination of more than one mechanism. In practice, DDSs are designed to achieve the cumulative release of substances within the therapeutic window and with kinetics close to zero order, i.e., regardless of the amount of drug remaining in the system [107]. Binding a certain amount of the active substance on the surface or in the polymer matrix leads to the initial so-called burst effect, the duration of which is directly proportional to the particle diameter [107] and may depend on the encapsulation technique. Using a cross-linking agent can protect against this effect, as can cleaning the particles with an organic solvent, but these methods decrease the loading of the biocomponent into the carrier.

Encapsulation of drugs or biocomponents in the chitosan matrix allows for sustained release, which increases the local drug concentration, and such controlled release of drugs reduces their cytotoxicity. Various materials are used for the encapsulation of biologically active compounds, including nanoparticles/nanocapsules, nanofibers, microspheres, hydrogels [45–47, 221]. Moreover, the nanoparticles based on chitosan can enter the cells’ interior, enhancing the concentration of the drug inside the desired cells. To conclude, in the case of targeted and local drug delivery, it is superior to systematic administration due to long-term and high-dose release of drugs in the desired part of human body, resulting in decreased toxicity to other organs [234].

This review provides an in-depth examination of the research conducted on chitosan and chitosan-based nanoparticles or microparticles. It highlights various drug delivery applications, focusing on antibacterial therapy, particularly for drug-resistant pathogens, anti-Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) therapy, and the ability to use chitosan-like carriers to deliver probiotic bacteria or other bacterial strains with biomedical potential. Moreover, the immunomodulating properties of chitosan are discussed in light of different vaccination strategies and anticancer therapies.

Biocompatibility, biodegradability and biological properties of chitosan

Owing to its biocompatibility, chitosan has been extensively studied for drug delivery applications with different administration routes, oral, topical, and parenteral, where it facilitates sustained/controlled drug release and prevents drug molecules from decomposing through encapsulation [119]. Chitosan has been characterized as being minimally toxic and is thus generally regarded as safe (GRAS) by regulatory agencies such as the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) when derived from high-quality sources via optimal protocols. Additionally, chitosan displays biocompatible contact properties with living matter and body fluids and exhibits mucoadhesive properties, allowing it to adhere to mucosal gastrointestinal or ophthalmic surfaces to enable the prolonged release of medicaments or ulcers/wound healing. A recent study conducted by Punarvasu and Prashant 2023, demonstrated that low-molecular-weight chitosan can be administered orally for pharmaceutical and food applications [231]. Various experimental approaches have been applied to prove the biocompatibility of chitosan, including cell viability assays, microscopic imaging of cell morphology, and assessments of cell proliferation and cell functions. The 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) reduction assay, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release assay, and live/dead staining techniques are commonly used to evaluate cell viability and the extent of damage caused by the application of chitosan and its derivatives [325]. The toxicity of chitosan is dose and time-dependent, and in a wide range of concentrations, chitosan is nontoxic to epithelial cells, fibroblasts, osteoblasts, chondrocytes, and immune cells [135, 182]. Its chemical composition facilitates protein interactions and cell adhesion [249]. This finding was also confirmed in artificial tissue models in which chitosan facilitated cell adhesion, multiplication, and differentiation by providing an appropriate environment for cells and stimulating the extracellular matrix [320]. Since chitosan is mucoadhesive and not hypersensitive, epoetin beta nanoparticles were developed via the ionic gelation technique for topical application in the posterior section of the eye. Chitosan combined with hyaluronic acid showed improved mucoadhesive properties and prolonged drug release [263]. In August 2023, the FDA approved a chitosan product as a primary material for wound healing in humans. A study executed by Matrix Medical Consulting, Inc. (USA) revealed that chitosan promoted a wound-healing effect associated with its antibacterial, noncytotoxic, non-sensitizing, and nonirritant properties [235]. The biocompatibility of chitosan also makes it useful in tissue engineering, where it serves as a scaffold material that supports cell attachment, proliferation, and differentiation—functions essential for the regeneration of various tissues, including skin, bone, and cartilage [24, 109]. Additionally, Rajinikanth et al. explored and documented chitosan's biocompatibility and wound-healing abilities in conjunction with significant antimicrobial properties that directly benefit the wound-healing process [235]. The hemostatic properties of chitosan have been exploited in the development of topical hemostatic agents that can accelerate coagulation and facilitate wound closure, which is crucial in both surgical settings and emergency medicine [160].

Mikušová and Mikuš reviewed advances in chitosan-based nanoparticles for drug delivery [189]. They highlighted the exceptional loading capacity of chitosan nanoparticles, with drug loading efficiencies reaching up to 90%. The unique chemical structure and biocompatibility of chitosan nanoparticles ensure minimal cytotoxicity, with cell viability exceeding 90%, even at high concentrations. The nanoparticles exhibited controlled release kinetics, with sustained drug release profiles lasting more than 72 h, making them promising candidates for targeted and prolonged drug delivery applications. The adaptability of chitosan to chemical modification further broadens its applicability, allowing the development of derivatives with enhanced solubility, strength, and bioactivity tailored to specific medical applications [302].

To confirm the suitability of chitosan-based products from the bench to the bedside, it is necessary to extend cytotoxicity studies for preclinical and clinical practice validation to ensure the safety and efficacy of chitosan-based formulations in vivo to obtain regulatory approval for healthcare application in wound dressings, surgical implants, drug delivery systems, and tissue engineering scaffolds [239].

Furthermore, other important issues to be discussed in terms of usage of the chitosan-based pharmaceuticals are their stability and biodegradability. Chitosan, as a natural polymer, is biodegradable to non-toxic oligosaccharides. Various groups of enzymes are able to degrade chitosan. In human body, these are mainly lysozyme and enzymes of bacteria present in human colon. However, several human chitinases, glucosidases and proteases have been identified as enzymes contributing to chitosan degradation [221]. The overview of the enzymes involved in chitosan degradation was presented by Aranaz et al. [18]. There are numerous factors that influence the stability and biodegradability of chitosan and chitosan-based materials, including molecular weight, polydispersity, deacetylation degree (DD), purity level and moisture content. Among them, the most important ones are molecular weight and DD. Chitosan of higher molecular weight degrades more slowly compared to chitosan of lower molecular weight and in general, the decrease in chitosan molecular weight causes its better adsorption by intestines [126]. DD is the ratio of glucosamine to N-acetylglucosamine units. This parameter usually ranges from 70 to 95% for the commercial chitosan [221]. The highest degradation rate was observed in vitro for DD of 50%, while increasing of DD significantly reduces chitosan degradation and the chitosan of DD above 90% exhibits only minimal degradation. Hence, the chitosan degradation can be controlled by changing the chitosan DD [221]. Additionally, to decrease the possibility of the biodegradation and to improve long-term stability of chitosan-based materials, for instance for storage purposes, various strategies are applied, including the addition of polyols, the preparation of the binary mixtures of chitosan with natural or synthetic polymers (like poly(ethylene oxide) or polyvinylopyrrolidone), and chitosan crosslinking [221]. For instance, the nanoparticles of PEGylated chitosan represent enhanced stability in the bloodstream [287]. Another example, the interactions of chitosan and oppositely charged polyelectrolytes (like sodium tripolyphosphate) enhance the stability of such materials during storage and stress conditions [25]. Similarly, alginate/chitosan microparticles represented increased stability not only in long-term storage but also in simulated gastric and intestinal juices [68]. Thus, the stability and biodegradability of chitosan-based materials can be tunned depending of its intended application.

A structured comparison between native chitosan and its modified forms regarding solubility, stability, and bioactivity is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

The comparisons between native chitosan and its modifications regarding solubility, stability and bioactivity

| Type of modification | Key achievements | Biomedical applications | Solubility | Stability | Bioactivity | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Native chitosan | Unknown | Unknown | Soluble in acidic conditions; poor solubility in neutral/alkaline pH | High thermal stability; maintains a crystalline structure | Antimicrobial, antioxidant, haemostatic | [70] |

| Deacetylated chitosan | Increases solubility, bioactivity | General drug delivery, wound healing | Enhanced solubility in neutral/alkaline pH; solubility increases with higher DD | Stability varies with DD; higher DD can reduce crystallinity, affecting thermal stability | Bioactivity is influenced by DD; higher DD can enhance bioactivity but may increase toxicity | [70, 290] |

| Depolymerized chitosan | Lowers viscosity, increases solubility | Injectable formulation, nanocarriers | Enhanced solubility in water and acetic acid; solubility increases with decreasing molecular weight | Reduced thermal stability; decomposition temperature decreases with lower molecular weight | Enhanced antimicrobial, antifungal, and antioxidant activities; bioactivity varies with molecular weight | [5, 183] |

| Quaternization- N-Trimethyl Chitosan (TMC) | High solubility at neutral pH, better stability | Oral/gene drug delivery, tissue repair | Enhanced solubility across a wide pH range due to quaternary ammonium groups | Decreased thermal stability; varies with degree of quaternization, more amorphous structure | Superior antimicrobial, antioxidant, and antifungal activities; pH-independent bioactivity | [79, 116] |

| Thiolated chitosan | Enhanced mucoadhesion | Mucosal drug delivery | Enhanced Solubility in Neutral and Alkaline Media | Susceptible to oxidation, leading to the formation of disulfide bonds | Mucoadhesion, antioxidant activity, enzyme inhibition, metal ion complexation | [74] |

| Sulphated chitosan | New bioactivity (neuronal differentiation) | Nerve regeneration | Improves solubility across a wider pH range | Decreases the thermal stability, complex degradation patterns | Anticoagulan, antimicrobia, and anti-inflammatory properties | [48, 188, 223] |

| Phosphorylated chitosan | Corrosion inhibition | Biomedical coatings | Improved water solubility | Decreases thermal stability and crystallinity | Enhanced bioactivity- antibacterial, antioxidant, and enzyme inhibitory properties | [63, 122, 256] |

In the context of health-promoting applications in humans, animals, and plants, the effects of the interactions of chitosan with components of the immune system of living organisms are particularly interesting. The immunomodulatory effects of chitosan are diverse, are dependent on its structure and dosing, and are related to the induction of pro- or anti-inflammatory cytokines. However, the precise definition of the immunomodulatory effect of chitosan is difficult because of the complex character of the inflammatory response, which can be beneficial or deleterious to the host. The inflammatory response is necessary for wound healing, but excessive cellular and humoral inflammatory responses can cause tissue damage. Chitosan has been shown to diminish inflammatory reactions in mice exposed to heat stress, which stimulates oxidative stress in intestinal tissue [195]. This study revealed that, compared with those in the heat stress group not treated with chitosan, the production of heat shock protein (Hsp)-70, toll-like receptor (TLR)-4, protein p65, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α and interleukin (IL)-10 in the chitosan-treated group was suppressed on days 1, 7 and 14. In mice inoculated with chitosan, the mRNA levels of the proteins claudin-2 and occludin, which are involved in epithelial cell integrity, were significantly increased.

It has been suggested that the purity of chitosan is essential for its immunological activity. In particular, lipopolysaccharide content, a molecular pattern of infectious agents that activates innate immune cells, may play a role. Ravindranathan et al. analyzed the effects of various biochemical properties (degree of deacetylation, viscosity, polymer length, and endotoxin levels) on the immune responses of antigen-presenting cells (APCs), including macrophages and dendritic cells by assessing the level of TNF-α as a biomarker of cell immunoreactivity [236]. This study revealed that only the endotoxin content and not the degree of deacetylation or viscosity influenced chitosan-induced immune responses. Low-endotoxin chitosan (< 0.01 EU/mg), ranging from 20 to 600 cP and 80% to 97% deacetylation, is inert. However, the structure of chitosan may also be necessary for inducing the activity of immune cells, as shown by Li et al. [162]. Hydroxypropyltrimethyl ammonium chloride chitosan (HACC) and hydroxypropyltrimethyl ammonium chloride fully deacetylated chitosan (De-HACC) were synthesized with various degrees of substitution by varying the ratio of chitosan to glycidyl trimethyl-ammonium chloride (GTMAC). The effects of the degree of quaternary ammonium groups and acetyl groups of these polymers on the immunostimulatory activities of chitosan were examined in RAW 264.7 cells. The levels of nitrogen oxide (NO), IL-6, and TNF-α were compared. The removal of acetyl groups from chitosan improved the degree of substitution of the quaternary ammonium salts, and HACC and De-HACC promoted the activity of immune cells in a substitution-dependent manner: HACC was positively correlated with immune cell activity, and De-HACC was negatively correlated. It was also concluded that the effects of chitosan are driven indirectly by NO, which is upregulated in response to chitosan [160]. A similar conclusion was reached in a study by Chandra and coworkers [41], who investigated the ability of chitosan nanoparticles to induce and augment immune responses in plants and the underlying mechanism. They showed that the treatment of leaves with chitosan nanoparticles significantly improved the plant’s innate immune response through the induction of defense-related genes, including those encoding antioxidant enzymes, and the elevation of total phenolics and NO, which are essential plant signaling molecules.

Knowledge about the signaling pathways induced by chitosan is still insufficient. Shibata et al. explained the macrophage response to chitosan particles in C57BL/6 mice and SCID mice injected intravenously with phagocytose chitin particles [259]. This study revealed that the oxidative burst of alveolar macrophages was increased 50-fold. Furthermore, animals pretreated with monoclonal antibodies against mouse interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) or with natural killer cells NK1.1 presented markedly decreased levels of macrophage activity following the injection of chitin particles. The macrophage priming mechanism induced by chitin particles potentially involves the direct activation of these cells by interferon delivered by NK1.1 CD4- lymphocytes, which may stimulate macrophages via the autocrine pathway [259]. Currently, the best-described intracellular signaling pathways activated in response to chitosan involve GMP–AMP synthase (cGAS), stimulator of interferon genes (STING), and Nod-like receptor (NLR) family pyrin domain containing 3 (NLRP3) [76].

The role of chitosan in the modulation of the immune system has been shown by dietary studies in experimental animal models and farm animals. Li et al. reported that the addition of 500 mg/kg chitosan to the diet affected humoral and cellular immune responses and improved the antioxidative function of beef cattle [162]. The levels of IgM and IgA tended to increase, and total superoxide activity increased, whereas the malondialdehyde content in the serum decreased. A study by Caires et al. on the implantation of tissue-engineered chitosan scaffolds revealed that chitosan interacts with macrophages and increases the secretion of several chemokines, including IL-8, macrophage chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1), and regulated on activation, normal T cell expressed and secreted (RANTES). Furthermore, macrophages increase stem cell motility within scaffolds by 44% [36].

Interesting results have been obtained from studies on the effects of chitosan on the determinants of immune cell activity in WEHI-3 mice with leukemia [308]. Chitosan increased the total white blood cell number and percentage of CD3-positive T lymphocytes in the animals and decreased the levels of CD19-positive B lymphocytes and CD11b-positive phagocytes after 5 mg/kg treatment and of Mac-3-positive cells after 5 and 20 mg/kg treatment. Moreover, chitosan significantly increased macrophage phagocytosis and the activities of glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase (GOT) and glutamic pyruvic transaminase (GPT) [308].

The idea of anti-bacterial chitosan formulations

Direct anti-bacterial activity of chitosan

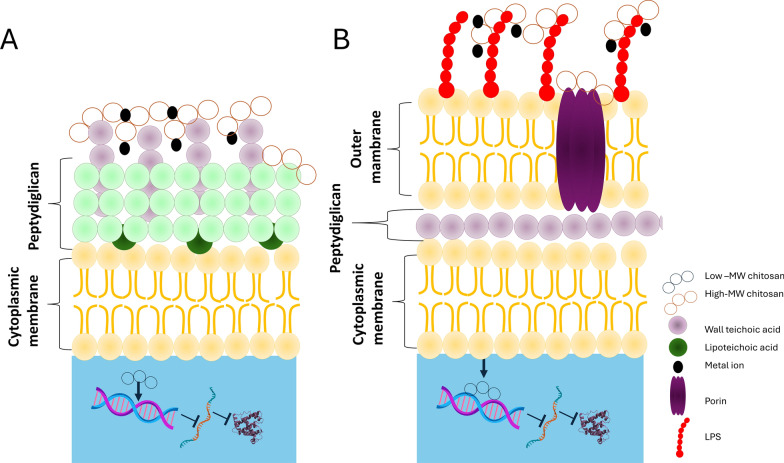

Chitosan shows antibacterial and antifungal activity by itself [120, 227, 243, 244, 260]. The mechanism of the bactericidal activity of chitosan depends on its molecular mass, degree of deacetylation, physicochemical properties (concentration, pH, contact time), structure, and reactive hydroxyl groups at the C-3 and C-6 positions. Chitosan may influence the growth of bacterial cells via interactions with bacterial surface structures, metal chelation, or interactions with DNA, as shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Schematic overview of action modes of chitosan on bacterial pathogens. A Gram-positive bacteria, B Gram-negative bacteria

The cell wall of Gram-positive bacteria consists of peptidoglycan and teichoic acids (TAs) covalently linked to peptidoglycan. In this group of bacteria, lipoteichoic acids (LTAs) are located in the cell membrane and are negatively charged; therefore, they interact directly with positively charged chitosan. In the cell wall of Gram-negative bacteria, there is a hydrophilic two-dimensional layer containing peptidoglycan, whereas the cytoplasmic membrane is made of lipopolysaccharide (LPS), lipoproteins, and phospholipids; thus, chitosan interacts with anionic components [139]. When the protonated amino groups of chitosan (NH3+) encounter an anionic bacterial surface (carboxylic residues, phosphate residues, etc.), the anion moieties may interact electrostatically with the protonated amino groups of chitosan, destroying the bacterial cell barrier and leakage of intracellular substances, especially if the chitosan is low in molecular weight [123]. In this case, chitosan exerts its antimicrobial effect by diminishing the stability of peptidoglycan and changing the osmotic balance of the cell membrane. Chitosan can also compromise the membrane by interfering with electron transport and redox processes [105, 173, 206]. High-molecular-weight chitosan prevents nutrient and oxygen uptake from the intracellular space by creating a polymer film on the surface of the bacterial cell wall. In contrast, low-molecular-weight chitosan penetrates bacterial cells, interacts with DNA, and diminishes protein synthesis, as demonstrated in an Escherichia coli (E. coli) model [142, 164, 309].

In the pioneer work of Zheng et al., it was concluded that chitosan with high molecular weight (above 166 kDa) possesses a good antimicrobial property against S. aureus due to the ability to form a film that suppresses the nutrient adsorptions. In contrast, this effect was inverted for E. coli, for which the decrease in chitosan molecular weight (5 to 48.5 kDa) causes the enhancement in its antimicrobial action due to penetration of the bacterial cell wall [323]. Nevertheless, the antimicrobial action against E. coli in one investigation is higher for low molecular weight chitosan [75], whereas in other ones, the high molecular weight was most effective [208].

Chitosan exerts a chelating effect, binding essential metals via charged amino groups and thereby inhibiting the growth of microbial agents [147]. This interaction between amino groups and divalent ions within the microorganism cell wall (Ca2+ or Mg2+) inhibits bacterial growth [102, 194]. These findings suggest that chitosan has better antibacterial activity against Gram-negative bacteria than Gram-positive bacteria because of the presence of LPS, which is often attached to phosphorylated groups, in the cell wall of Gram-negative bacteria [75, 134]. Chitosan binds essential metal ions required for bacterial growth and function. It may occur on bacterial cell surfaces, where it can attach to phosphate groups in lipopolysaccharide (LPS) or other molecules. Such an interaction could cause cell surface instability, potentially rupturing membrane [91]. Chelation occurs through electrostatic attraction facilitated by protonated amine groups. In acidic conditions, the amino groups in chitosan acquire a positive charge due to protonation. These charged amine groups can engage electrostatically with negatively charged regions on the bacterial cell surface, resulting in destabilization of the cell membrane [91, 92]. Chelation and electrostatic attraction can alter the permeability of the bacterial cell membrane, resulting in an osmotic imbalance. This imbalance may cause cell swelling and, ultimately, cell lysis or death. Furthermore, chitosan can disrupt the cell wall by hydrolyzing peptidoglycans, thereby promoting the release of intracellular components [220, 295].

An important question is whether the natural ion-chelating property of chitosan, particularly the ability to bind with divalent cations such as calcium, magnesium and zinc [232, 281], which is beneficial against infection agents will cause adverse effects in vivo as a drug carrier even though the chitosan is considered biocompatible and safe as a drug delivery carrier, particularly for the application of topical, local and temporary use [103, 125]. These characteristics of the chitosan can significantly influence in vivo, especially when used as a drug delivery system. The ions-chitosan complex can modify the drug delivery carrier by localizing to a specific site of action or enhancing loading capacity into the chitosan particulate system [59]. Additionally, the chelation of chitosan with ions improves the carrier system's stability and the drug's release in a controlled manner. However, chelation can also produce adverse effects, such as nutritional depletion from the gastrointestinal tract or bloodstream, which may lead to micronutrient deficiencies. Additionally, the chelation with calcium ions intercellularly could interrupt the cell signaling [268], contraction and functions of muscles and neurons, respectively, which further leads to abnormal processing of the physiological environment [18, 281]. However, most of the studies demonstrated that the chelating effect of chitosan is not strongly evidenced by clinical adverse effects in vivo in both short and long-term use [78].

The degree of chitosan deacetylation, which indicates the percentage of deacylated (glucosamine) units, influences its antibacterial properties and its interaction with bacterial membranes. Higher bacterial cell membranes disruption as a result of chitosan activity may result in an increased production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which can damage cellular components such as DNA, proteins, and lipids. The effectiveness of ROS-related damage depends on chitosn concentration and duration of cell exposure. The mechanism through which chitosan induces ROS production depends on the disruption by chitosan of electron transportation [309]. Chitosan concentration significantly influences its capacity to inhibit bacterial enzymatic pathways [309]. The pH significantly influences the chitosan charge. At lower pH, chitosan charge is more positive, facilitating its stronger interaction with bacterial cells [190].

Interfering with Quorum Sensing, a communication system in bacteria that is crucial for coordinating virulence factors and the development of bacterial biofilms, can be affected by chitosan due to inhibition of the synthesis of autoinducers (AIs), which bacteria use as chemical signals for communication [251]. It has been shown that chitosan nanoparticles combined with carvacrol effectively reduced violacein production in Chromobacterium violaceum, which is regulated by quorum sensing [27]. Chitosan can inhibit AI signaling by interfering with the binding of AIs to their receptors, thereby preventing the activation of the signaling pathways. This can occur through various mechanisms, such as competitive binding with the AI molecule or by altering the receptor's structure [202].

Chitosan as a matrix for delivery of antimicrobial peptides

Chitosan is an excellent material for delivering antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) and proteins that act as antimicrobial agents. The novel systems used to fight bacteria are listed in Table 2. The presence of primary amino and hydroxyl groups in the chitosan backbone significantly enhances the possible modifications of the prepared materials [226] and, in some cases, facilitates interactions with the AMP or protein to be delivered. Using chitosan-based drug delivery systems allows an increase in the local drug concentration, providing sustained release and simultaneously decreasing systemic toxicity [110]. Additionally, various modifications of the chitosan structure provide stimuli-responsive materials that can direct the drug to infection sites. Furthermore, the encapsulation of AMPs and antimicrobial proteins protects these molecules from proteolytic degradation [33]. Finally, another great advantage of using chitosan in antimicrobial delivery systems is that it also has antimicrobial properties; hence, chitosan has been used as a component of toothpaste [39] and mouthwash [57].

Table 2.

The list of the described chitosan-based antimicrobial peptide or protein delivery systems

| Antimicrobial peptide or protein | Matrix | Materials | Bacterial target | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peptides | ||||

| Mastoparan | Chitosan | Nanoconstructs | multidrug-resistant (MDR) Acinetobacter baumannii (A. baumannii) | [100] |

| Nisin | Chitosan for coating microcontainers | Microcontainers |

pathogenic bacteria colonizing the oral cavity |

[29] |

| Nisin | Carboxymethyl chitosan-nisin nanogels and pullulan as core, and carboxymethyl chitosan/ polyethylene oxide as a shell layer | Electrospun core–shell nanofibers | Escherichia coli (E. coli), Staphylococcus aureus(S. aureus) | [67, 293] |

| Nisin | Chitosan functionalized with DNase I | Nanoparticles | Listeria monocytogenes (L. monocytogenes) | [114] |

| Nisin | Chitosan lactate (CHL) 1:3 ratio with blends of polysaccharides (corn starch, wheat starch, oxidized potato starch, or pullulan) | Films | various food-borne bacteria | [144] |

| Nisin | Carboxymethyl chitosan | Nanogels | various food-borne bacteria | [294] |

| Piscidin-1 | chitosan crosslinked to β-glycerolphosphate disodium salt pentahydrate | Hydrogels | multidrug-resistant (MDR) A. baumannii | [240] |

| Vancomycin | Chitosan and oleylamine-based zwitterionic lipid-polymer hybrid | Nanovesicles | methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) | [101] |

| Vancomycin | Chitosan/polyethylene oxide | Electrospun core–shell nanofibers | methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) | [130] |

| Vancomycin | Chitosan–polylactide | Microspheres | E. coli, S. aureus | [154] |

| Vancomycin | Chitosan-polyaniline | Microgels | S. aureus | [160] |

| Vancomycin |

Chitosan photo-crosslinked to pore-closed poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) microparticles |

Hydrogels |

pathogenic bacteria colonizing the oral cavity |

[267] |

| Vancomycin | Chitosan and cinnamaldehyde-based thioacetal (CTA) together with ginipin as the crosslinker | Hydrogels | methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) | [285] |

| GL13K peptide derived from the human salivary parotid secretory protein or innate defense regulator (IDR)-1018 derived from bovine neutrophil host defense peptide bactenecin | Chitosan and pectin derivatives | Nanofiber membranes |

pathogenic bacteria colonizing the oral cavity |

[30] |

| Nal-P-113 | Chitosan combined with polyethylene oxide | Nanoparticles |

pathogenic bacteria colonizing the oral cavity |

[115] |

| Proteins | ||||

| Azurin | Chitosan | Nanoparticles | bacterial species related to gastrointestinal cancer biopsies: Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori), Bacteroides fragilis (B. fragilis), Salmonella enterica (S. enterica), Fusobacterium nucleatum (F. nucleatum), and Porphyromonas gingivalis (P. gingivalis) | [11] |

| Chimeric endolysin | Chitosan | Nanoparticles | E. coli, S. aureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa (P. aeruginosa) | [1] |

| Endolysin Cpl-1 | Chitosan | Nanoparticles | S. pneumoniae | [86] |

| Endolysin LysMR-5 | Alginate-chitosan | Nanoparticles |

methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) |

[132] |

| Histatin 3 (HTN3) | Chitosan | Nanoparticles |

pathogenic bacteria colonizing the oral cavity |

[324] |

| Lactoferrin | Alginate-chitosan | Microparticles | Clostridioides difficile (C. difficile) | [32] |

AMPs are short, water-soluble peptides produced by various organisms for host defense. Among the chitosan-based AMP delivery systems, the two most popular are nisin (NIS) and vancomycin (VM) (Table 2). NIS is a bacteriocin produced by Lactococcus lactis (L. lactis) and belongs to the lantibiotic family of AMPs, which show antibacterial activity against a broad range of Gram-positive bacteria. Nisin prevents the synthesis of the bacterial cell wall and creates pores in the membrane, causing bacterial cell death. Notably, NIS has GRAS status and is used as a food preservative [65]. VM is a glycopeptide produced by the soil bacterium Amycolatopsis orientalis (A. orientalis). It also has activity against Gram-positive bacteria and inhibits cell wall synthesis. It is used as an antibiotic for infections caused by bacteria resistant to other antibiotics [200], and the World Health Organization (WHO) classifies it as critically important for human medicine. Most of the discussed chitosan-based materials contain VM or NIS.

Chitosan-based AMP delivery systems against multidrug-resistant bacteria

Most recent studies regarding multidrug-resistant bacteria have focused on systems designed to fight MRSA, which is a serious threat to human life and is becoming a global problem [99]. The treatment of skin infections and chronic nonhealing wounds caused by MRSA is especially challenging; hence, some chitosan-based materials have been proposed to deliver VM, one of the antibiotics used in severe cases of MRSA infections [101, 200].

Hassan et al. [101] proposed a formulation of chitosan-based pH-responsive lipid‒polymer hybrid nanovesicles (VM‒OLA‒LPHVs1) carrying VM, where the lipid component was oleylamine-based zwitterionic lipids (OLAs), which also enhance antimicrobial properties. The authors assumed that the resulting polyelectrolyte nanovesicles should have the free amino and hydroxyl groups of chitosan at the surface. In contrast, the carboxylic group of OLA should create electrostatic bonds with VM. In vitro drug release studies revealed that VM release was greater at pH 6.0 than at pH 7.4, indicating that the prepared nanovesicles are pH-responsive. The protonation of the amine groups of chitosan and OLA might cause this. Additionally, acidic pH increased the hydrophilicity of the formulation, which could also result in the breakdown of the system. pH-responsive systems are desirable for the treatment of wound infections, as an acidic pH is present at bacterial infection sites. Further studies revealed that VM-OLA-LPHVs1 were more effective at killing bacteria and eradicating biofilms in a BALB/c mouse skin infection model than free VM [101].

Another type of material proposed for wound healing is a system of hybrid chitosan/polyethylene oxide (PEO) nanofibers loaded with VM. PEO, similar to chitosan, is biocompatible. It can form hydrogen bonds with chitosan, leading to chain stiffness of the resulting nanofibers. The concentration of VM in the nanofibers was 2.5 or 5% (w/v), and in vivo studies revealed that a lower antibiotic concentration was optimal. The wound area of the 2.5% VM group of rats was smaller than that of the 5% VM group, indicating a more efficient healing process [130].

The VM-bearing hydrogel was prepared by grafting chitosan and cinnamaldehyde-based thioacetal (CTA) with ginipin as the crosslinker. The covalently cross-linked chitosan hydrogels can adsorb large amounts of liquid. The inclusion of CTA in the formulation was advantageous because of two properties [285]. First, CTA was proven to sense ROS [301] thus, the produced material became stimuli-responsive [287]. Second, exposure to ROS causes the release of cinnamaldehyde from CTA, and cinnemaldehyde has bactericidal properties, as it destroys the bacterial cell wall. The hydrogel was tested in vivo in a mouse full-layer skin defect model. It accelerated wound healing and skin regeneration processes and contributed to improved VM bioavailability, which makes it an excellent material for the treatment of MRSA-induced skin infections [287].

Chitosan-based AMP delivery systems for the treatment of S. aureus infections are not limited to wound healing. VM-chitosan-polyaniline microgels [156] and VM-chitosan-polylactide microspheres [160] have been proposed for the delivery of VM to the inflamed intestine or to infected bone tissue, respectively. The microspheres were prepared using various ratios of amino Schiff base chitooligosaccharides to lactide, and the most efficient drug release was obtained at a ratio of 1:00. The microspheres exhibited antibacterial properties against S. aureus and E. coli [154]. VM-chitosan-polyaniline microgels were designed for lysozyme-triggered VM release. Lysozyme cleaves the glycosidic bonds of chitosan, which results in drug release. Interestingly, intestinal pathogens lead to cell dysfunction, and consequently, lysozyme is secreted in more significant amounts than in healthy cells. Hence, the proposed microgels can be used to treat intestinal infectious diseases, such as inflammatory bowel disease, and can target only the infected sites of the intestine without harming healthy tissue. The tests performed in the simulated inflammatory intestinal microenvironment confirmed this behavior of the microgels. Additionally, VM-chitosan-polyaniline microgels are stable at the acidic pH values in the stomach [165].

Another dangerous multidrug-resistant bacterium that can infect wounds is A. baumannii. In vitro, studies of AMP-loaded thermoresponsive chitosan hydrogels confirmed that this material is cytocompatible, as tested on Hu02 fibroblasts. These cells exhibited appropriate attachment and growth on the hydrogel. Thermoresponsiveness was achieved by the use of β-glycerolphosphate disodium salt pentahydrate as a cross-linker. The AMP loaded into the chitosan hydrogel was piscidin-1 [240], a peptide originating from aquaculture fishes. Piscidin-1 has a broad range of antimicrobial activity against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, yeast, and fungi; however, its cytotoxicity to red blood cells limits its use [148]. Hence, its utilization in a hydrogel that can be applied as a topical antimicrobial agent reduces its toxic effects [240]. A. baumannii not only infects wounds but also causes pneumonia, urinary tract infections, and septicemia. Thus, it is also called a superbug, and along with S. aureus, it has been included in the top six most dangerous pathogens (ESKAPE) [291]. Chitosan-based nanoconstructs loaded with mastoparan, another AMP, were prepared to fight these bacteria [100]. Mastoparan is a peptide extracted from wasp venom that disrupts the bacterial cell membrane, leading to increased permeability and cell death [112]. The preparation of the nanocomplex was preceded by molecular dynamics simulations, which demonstrated that chitosan cross-linked with sodium tripolyphosphate and mixed with mastoparan most likely forms circular rings encasing the mastoparan. The nanoconstructs caused bacterial damage during in vitro studies and reduced the number of bacterial colonies in BALB/c mice (sepsis model) [100].

Chitosan-based AMP-delivery systems against oral cavity bacterial pathogens

Various chitosan-based materials have been designed to deliver AMPs to infection sites in the oral cavity. Many microbes that colonize the oral cavity have beneficial effects on human health. However, they sometimes form biofilms of pathogenic bacteria that cause periodontitis and dental caries [60]. An AMP-delivery system targeting multispecies bacterial biofilms was proposed. It is based on miniaturized devices, called microcontainers (MCs), loaded with nisin. MCs were functionalized with a lid made of chitosan, taking advantage of its mucoadhesive properties. These bioadhesive MCs enable the retention of nisin in the oral cavity. These MCs are not easily removed by flowing saliva and are more effective than free nisin [29].

Another system that is dedicated to fighting periodontitis, especially periodontitis related to root caries, is based on PEO combined with chitosan nanoparticles loaded with a novel AMP, Nal-P-113 [115]. This peptide is a modification of peptide P-113, which is currently used in various products available on the market. The histidine residues of P-113 are replaced in Nal-P-113 with β-naphthylalanines, which increases the ability of the peptide to penetrate deeper into the bacterial cell membrane [283]. In vitro studies revealed that the proposed nanoparticles inhibited the growth of F. nucleatum, Streptococcus gordonii, and P. gingivalis. In addition, they are efficient at inhibiting bacterial biofilms [115].

The bioadhesive properties of chitosan have also been exploited to develop nanofiber membranes that adhere to both soft mucosal and hard bone/enamel tissue. The dual nature of the material was achieved by coating chitosan membranes with oxidized pectin. The resulting nanofiber membranes exhibit moderate and reversible underwater adhesion properties. Additionally, the membranes are pH-responsive, which is a desired feature of such materials, as the oral pH is approximately 6.7, whereas it decreases as far as 4.5 during infection. The nanofiber membranes were loaded with GL13K peptide, derived from the human salivary parotid secretory protein, and innate defense regulator (IDR)-1018, derived from the bovine neutrophil host defense peptide bactenecin. Both peptides have antimicrobial properties and were released in a pH-controlled manner in the in vitro studies [30].

Song et al. proposed a chitosan-based hydrogel that delivers not only the AMP vancomycin but also recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 (rhBMP-2), which promotes osteogenesis [267]. Hence, hydrogels have great potential in supporting the dental implantation process. The proposed hydrogel combined chitosan and pore-closed poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) microparticles. The chitosan matrix was loaded with VM, whereas the microparticles contained rhBMP-2. This formulation enabled the sequential release of the peptide and the protein, as shown by in vitro and in vivo studies. VM was released rapidly for the initial two days, while rhBMP-2 was released in a sustained manner for approximately 12 days. Thus, the hydrogel protected the implantation site from infection and promoted osteointegration of the dental implant [267].

Chitosan-based AMP delivery systems as food packaging materials prevent the development of pathogenic microorganisms

The antimicrobial properties of peptides have also been utilized to prevent the growth of various foodborne bacteria and improve the safety of stored food products. Chitosan, a biodegradable polymer, is used as a matrix to prepare different materials dedicated to food packaging and carrying AMPs. In all the examples described here, the AMP of choice was NIS [111, 144, 294].

Kowalczyk et al. performed comparative studies of films based on blends of chitosan lactate and one of the following polysaccharides: corn starch, wheat starch, oxidized potato starch, or pullulan [144]. The incorporation of NIS into the films at acidic pH protected NIS from degradation, as it is inactive under alkaline conditions. The blends were prepared using a 75:25 polysaccharide: chitosan lactate ratio. Various concentrations of NIS were introduced into the mixture prior to casting the material on trays and drying, which led to the formation of films. Pullulan offers antifungal activity, which is also desirable in packaging materials; hence, this polysaccharide was also tested. The NIS release kinetics were studied in water, and the obtained films were water soluble; thus, at the final stages of the experiment, NIS was wholly released from the films. NIS was released more slowly from starch/chitosan lactate films than from pullulan-containing films, which was preferable, as AMP should be released slowly during food storage. All formulations exhibited similar antimicrobial activity and limited the growth of Bacillus cereus (B. cereus), L. monocytogenes, S. aureus, and the phytopathogen Pectobacterium carotovorum (P. carotovorum) but did not inhibit the growth of E. coli or S. enterica ssp. enteretica sv. Anatum [144].

Chitosan and pullulan have also been combined to prepare electrospun core–shell nanofibers dedicated to fish storage and protection from spoilage. The nanofibers were prepared via coaxial electrospinning. Pullulan was the core of the fibers, whereas carboxymethyl chitosan (CMCS)/PEO constituted a shell layer. Moreover, CMCS-NIS nanogels were obtained via self-assembly and loaded into the core of the nanofibers. This material exhibited good thermostability, mechanical strength, and antibacterial properties when tested against S. aureus and E. coli. Additionally, it was used for the storage of bass and extended the shelf life from 9 to 15 days [63]. Another CMCS-based material for food packaging was a nanogel loaded with NIS and prepared via a combination of electrostatic self-assembly and chemical crosslinking. Like the described nanofibers, the nanogel exhibited antibacterial activity against S. aureus and E. coli [294].

Chitosan nanoparticles loaded with NIS were prepared to inhibit the growth of L. monocytogenes, a food-contaminating bacterial species that causes life-threatening infections and economic losses. The nanoparticles were further functionalized with DNase I by covalent grafting of the enzyme onto the nanoparticle surface [114]. DNase I degrades eDNA, which is essential for biofilms' structural stability and promotes bacteria's aggregation and intercellular adhesion [215]. Hence, the use of this enzyme in the formulation enhanced the reduction in L. monocytogenes biofilm formation on polyurethane [114].

Chitosan-based antibacterial protein delivery systems

The use of proteins as antimicrobial components of drug delivery systems is even more complicated than the use of peptides. Proteins are much larger and much more fragile and prone to proteolytic degradation, and many factors can cause their denaturation. The loading of proteins into chitosan-based nano- or microparticles significantly extends the in vivo half-life of the proteins. Hence, there have been trials describing the utilization of several proteins in chitosan-based drug delivery systems aimed at fighting bacteria (Table 2).

Among proteins with antibacterial properties, endolysins represent a large group of novel antimicrobial agents. These proteins are also classified as enzybiotics, as their antibacterial properties are closely related to their enzymatic activity. Endolysins are peptidoglycan hydrolases originating from bacteriophages, and according to their class, they target peptidoglycans of the bacterial cell wall. They are effective against life-threatening bacteria such as MRSA, as bacteria currently exhibit low resistance to these molecules. These enzymes usually comprise two domains: an N-terminal catalytic domain and a C-terminal domain responsible for binding to the bacterial cell wall [94]. The recombinant proteins provide the possibility to modify the protein of interest further, and such an attempt was made to produce a chimeric endolysin composed of the N-terminal domain representing cysteine/histidine-dependent amidohydrolase/peptidase (CHAP) and the C-terminal domain originating from the endolysin LysK amidase-2 domain connected by a decapeptide linker. The chimeric protein reduced the growth of MRSA [95] and was thus chosen to prepare nanoparticles against different bacteria. Two types of chitosan nanoparticles were designed: in one of the proposed formulations, chimeric endolysin was attached covalently to the nanoparticles, whereas in the other formulation, the chimeric protein was noncovalently entrapped in the nanoparticles. The lytic activity of the nanoparticles was shown against S. aureus, E. coli, and P. aeruginosa. Furthermore, a synergistic effect between the nanoparticles and VM was observed. Additionally, the nanoparticles effectively reduced biofilm formation by E. coli [1].

Cpl-1 is another endolysin used for the preparation of nanoparticles. This drug delivery system was developed to fight antibiotic-resistant S. pneumoniae. The mucoadhesive properties of the chitosan nanoparticles were tested ex vivo, and the results confirmed the mucoadhesive nature of the formulation. Moreover, in vitro and in vivo studies have shown that these nanoparticles are biocompatible, noncytotoxic, and able to stimulate the immune system of tested mice [86]. Both chimeric endolysin and Cpl-1 were entrapped in chitosan nanoparticles prepared via ionic gelation with the addition of sodium tripolyphosphate (TPP) [1, 86]. In contrast, the preparation of the delivery system for endolysin LysMR-5 involved the use of sodium alginate. The process started with the mixing of sodium alginate with LysMR-5. Then, the pregelation of the alginate core loaded with LysMR-5 was induced by calcium ions, and the next step was complexation with chitosan. The gelation method for the production of nanoparticles requires mild conditions that are safe for proteins. The proposed LysMR-5-delivery system was tested in vitro, and it exhibited antibacterial properties against S. aureus and was not cytotoxic [132].

Proteins encapsulated in chitosan nanoparticles can also be used to prevent dental caries. Histatins (HTNs) are salivary proteins that act in the oral cavity to maintain homeostasis and exhibit antibacterial properties. HTN3, a representative histatin, was used to prepare nanoparticles that target bacteria in the oral cavity. Here again, the ionic gelation method with TPP was utilized. Interestingly, in vitro studies revealed that the chitosan nanoparticles with and without HTN3 both showed antibacterial properties against S. mutans, a bacterium that plays a significant role in forming dental caries, and reduced biofilm formation. Chitosan also has antibacterial properties; in this case, the nanoparticles efficiently killed the bacteria even when HTN3 was absent [324]. In other reports, the release of AMP or proteins with antimicrobial properties usually significantly improved the antibacterial effect of the material. It is possible that more differences could be observed when the tests include additional bacterial species.

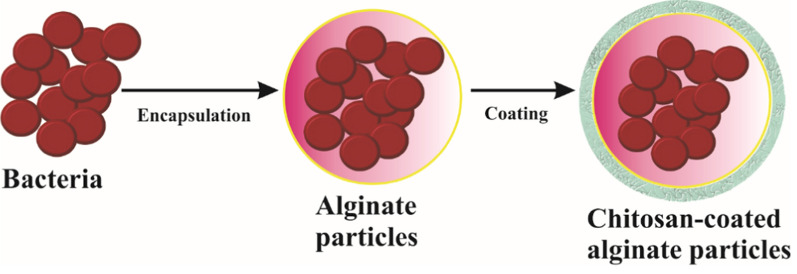

Some proteins have antibacterial and anticancer properties. An example of such a protein is azurin, which is produced by the pathogenic bacteria P. aeruginosa. Notably, in some cancers, such as gastrointestinal cancer, various bacteria are detected in biopsies from patients. These bacteria include H. pylori, B. fragilis, S. enterica, F. nucleatum, and P. gingivalis, which can all contribute to cancer development [108]. Azurin immobilized via adsorption on the surface of chitosan nanoparticles was shown to exhibit antibacterial and anticancer properties [11]. A different approach was used to design a delivery system for bovine lactoferrin, a protein that exhibits antibacterial properties against C. difficile, a dangerous pathogen of the colon. The authors of this study aimed to deliver the protein to the colon via the gastrointestinal tract. Thus, factors such as changing pH values in different parts of the tract are essential. Bovine lactoferrin was encapsulated in alginate microparticles via gelation or emulsification methods. The microparticles were coated with chitosan. The release of the protein was tested at different pH values that simulate various conditions in the gastrointestinal tract. No release was noted at acidic pH values, whereas pH 7.4, which mimics the colon environment, caused the release of most of the encapsulated lactoferrin. The microparticles were also applied to human intestinal epithelial cells and reduced the cytotoxic effects of C. difficile toxins A and B [32].

In summary, proteins can be successfully encapsulated in chitosan nano- or microparticles or immobilized on chitosan materials. The size of the proteins used in the studies varied from 50 (for HTN3) and 128 (for azurin) to 689 amino acid residues (for bovine lactoferrin). A comparison of the available spatial structures of azurin and lactoferrin (Fig. 2) revealed that the dimensions of such molecules are less than 10 nm (100 Å); hence, it is possible to pack a certain amount of such molecules in nano- or microparticles. The mild conditions used to prepare these materials enable the proper function of the proteins at the target sites.

Fig. 2.

Scheme of most common encapsulation of bacteria in particles composed of alginate core and chitosan shell

The chitosan showed immunogenic properties when used as a drug delivery carrier for proteins or as adjuvant in vaccine formulations. This activity was found to be dose-dependent and influenced by the chitosan structure [14, 80]. In the study by Koppolu and Zaharoff [143], the bovine serum albumin labelled with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC-BSA) or ovalbumin (OVA) were loaded in particles developed by the precipitation-coacervation method. The effectiveness of encapsulation reached 89% and particle size was in the range 3–300 µm. These particles were engulfed by antigen presenting cells (APCs), which were then activated. Another study showed that chitosan was involved in modifying the maturation, activation, cytokine production, and polarization of dendritic cells (DCs) and macrophages both involved in the development of innate and adaptive immune responses, and the potential mechanisms are based on modulation of different signaling pathways, including cGAS-STING, STAT-1, and MLRP3 [80]. Oliveira et al. showed [211] that in response to chitosan particles, the activity and motility of macrophages were increased. The study by Scherlie et al., [252] revealed that chitosan-driven immunomodulatory effects were associated with different physicochemical characteristics of chitosan, including molecular weight, particle size, extraction technique, and degree of deacetylation (DDA). A lower degree of DDA (76%) resulted in higher reactivity of immune cells compared to chitosan with higher DDA (81%). Low chitosan dose induced an anti-inflammatory response related to releasing IL-1ra without activation of inflammasomes while a high dose of chitosan caused disruption of lysosomes present in immune cells resulting with an activation of inflammasomes and pro-inflammatory response [76]. In has been shown that chitosan induces type-I interferon response driven by activation of cGAS-STING signaling pathway [76].

It is worth mentioning that content of bacterial endotoxin may influence the immune properties of chitosan. However, contamination with endotoxin from Gram-negative bacteria below 0.01EU/mg does not activate an immune cells. The influence of chitosan concentration, contamination with endotoxin, chemical modifications, presence of antigen or the rout of administration on immune and undesired effects are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

The influence of different factors on chitosan-related immune effects and undesired reactions

| Factor | Immune effect | Potential undesired reaction | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low chitosan dose | Anti-inflammatory (IL-1ra, type I IFN) | Minimal risk | [71] |

| High chitosan dose | Pro-inflammatory (IL-1β, PGE2 via inflammasome) | Local/systemic inflammation, tissue damage risk | [79] |

| Endotoxin contamination | Strong pro-inflammatory cytokine release | Severe inflammation, confounded safety profile | [80] |

| Presence of antygen | Enhanced adaptive immunity (Th1/Th2/Th17) | Hypersensitivity, DTH responses | [143] |

| Route (e.g., subcutaneous) | Depot effect, prolonged immune stimulation | Local inflammation, injection site reactions | [14] |

| Chemical modifications | Variable immunogenicity | Unknown, requires case-by-case evaluation | [212] |

Chitosan-based vaccines against bacterial pathogens

Emerging research has explored the immunomodulatory effects of chitosan, which could enhance its application in vaccine delivery by improving the immune response to various antigens [121]. Several studies have proposed chitosan nanoparticles or microparticles as carriers for numerous antigens, representing new candidate vaccines against bacterial infections. These nanoparticles are biocompatible, biodegradable, and non-toxic; have the desired size, shape, and large surface area; and exhibit high permeability and stability over a range of ionic conditions [226, 320, 321]. Hence, antigens loaded into chitosan carriers can be efficiently delivered to target sites. Additionally, chitosan derivatives can act as adjuvants, increasing the immunogenic properties of the vaccine antigens [179, 237, 238, 250].

The ideal nanoparticle size for vaccine applications generally ranges from 20 to 200 nm, particularly those around 50 nm, which often exhibit better uptake efficiency by APCs, such as dendritic cells or B lymphocytes [286]. Spherical shapes are common and effective in facilitating cellular uptake, while surface area plays a crucial role in antigen loading and delivery [322]. Although smaller particles are typically favored for uptake, larger ones (such as 160 nm) have demonstrated the ability to attract a greater number of immune cells to the injection site.

Chitosan's permeability and stability are significantly influenced by ionic conditions, particularly pH. Although chitosan is typically insoluble in water due to strong intermolecular hydrogen bonds, it becomes soluble in acidic solutions (pH < 6) due to the protonation of its amino groups. This protonation also influences its susceptibility to enzymatic degradation, with acidic conditions resulting in a more rapid breakdown. These changes in the properties of chitosan, which vary with pH, have significant implications for antigen delivery, as they can impact its ability to encapsulate and release antigens, as well as its interaction with biological tissues [304]. For example, a nanoparticle composed of chitosan could be designed to release antigen specifically at a targeted pH as in the stomach's acidic environment or lysosomes [15]. Chitosan's cationic properties at lower pH can enhance its interactions with negatively charged biological surfaces, potentially improving mucoadhesion (the adhesion to mucus membranes) or targeting [15, 91].

Chitosan-based vaccines against bacterial infections usually contain a protein or part of one, which represents the antigen or the DNA encoding such a protein. The latter is designed mainly to prevent infections spread by fish pathogens and was reviewed recently [6, 297]. Vaccines based on recombinant proteins require adjuvant systems to generate T helper (Th) 1-type immune responses. Chitosan is a good candidate in conjunction with IL-12, which induces T lymphocytes and NK cells to produce IFN-γ, granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), and TNF-α; directs CD4 + T lymphocytes toward Th 1 differentiation; and induces T-cell proliferation [104].

The regulation of immune cells, particularly macrophages and NK cells, is greatly influenced by the structure of chitosan and the content of endotoxins [71, 152]. Endotoxins, such as LPS, strongly activate the innate immune cells such as macrophages and NK cells via TLR4 while chitosan as another conservative pattern molecule via TLR2 and Dectin-1 [72]. Cytotoxicity of NK cells increased by chitosan may be an indirect effect driven by DCs, which deliver IFN-γ [211]. The activation of DCs by chitosan also prompts the release of different pro-inflammatory cytokines like IL-12 and IL-15, which further activate NK cells [72]. It has been shown that chitosan activates macrophages by stimulating the NLRP3 inflammasome, which triggers the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β. It also initiates the STAT-1 pathway, producing pro-inflammatory cytokines and secretion of nitric oxide. However, chitosan can also influence the polarization of macrophages, steering them towards anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype that promotes tissue repair and alleviates inflammation but due to down regulation of the immune cells may promote the development of cancer [211, 213]. The content of endotoxins and the structure of chitosan are pivotal in influencing immune responses. Endotoxins primarily affect macrophage activation, while chitosan exhibits a broader range of effects that can engage both macrophages and NK cells. Understanding these interactions is essential for developing effective strategies for immune modulation and therapeutic interventions.

This section focuses mainly on protein-based chitosan vaccine candidates reported in the past five years, which are listed in Table 4.

Table 4.

The list of the described chitosan-based vaccine candidates loaded with various proteins representing antigens

| Pathogen | Infected organism | Vaccine matrix | Materials | Particles triggering immune response, loaded in chitosan | Vaccine distribution | Organisms in which in vivo studies were performed | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Avian pathogenic E. coli (APEC) | Poultry | Ascorbate chitosan | Nanoparticles | Outer membrane protein-flagellar antigen (O-F) | Not specified | Chickens | [193] |

| Bordetella bronchiseptica | Mammals | Chitosan | Nanoparticles | Outer membrane vesicles (OMVs) | Subcutaneous | Rabbits | [161] |

| Brucella abortus (B.abortus) | Human | Chitosan | Nanoparticles | Malate dehydrogenase and/or outer membrane proteins (Omp10 and Omp19) | Intranasal | Mice | [261] |

| B. abortus | Human | Chitosan | Nanoparticles | Malate dehydrogenase | INTRANASAL | Mice | [262] |

| Brucella melitensis (B. melitensis), B. abortus | Human | Mannosylated chitosan | Nanoparticles | Flagellin FliC | Subcutaneous | Mice | [250] |

| Campylobacter jejuni (C. jejuni) | Poultry | Chitosan-sodium tripolyphosphate | Nanoparticles | Hemolysin co-regulated protein (hcp) | Oral | Chickens | [264] |

| C. jejuni | Human | Chitosan | Nanoparticles | Outer membrane vesicles (OMVs) | Oral | Mice | [265] |

| Chlamydophila psittaci (Ch. psittaci) | Animal | Chitosan | Nanoparticles | Multi-epitope peptide antigens | intramuscular and intranasal | Mice | [166] |

| Ch. Psittaci | Poultry | Vibrio cholerae (V. cholerae) ghost (VCG) – chitosan | Hydrogel | Chlamydophila elementary bodies (EBs) | Intranasal | Chickens | [158] |

| Ch. Psittaci | Poultry | V. cholerae ghost (VCG) – chitosan | Hydrogel | Multiple polymorphic membrane protein G (PmpG) antigens and major outer membrane protein (MOMP) | Intranasal | Chickens | [326] |

| Clostridium perfringens (C. perfringens) | Chicken (broilers) | Chitosan | Nanoparticles | Toxoids of extracellular proteins of C. perfringens, surface-tagged with Salmonella flagellar proteins | Oral | Chickens | [10] |

| Enterohemorrhagic E. coli (EHEC) Shigella dysenteriae (S. dysenteriae) type 1 | Human | Chitosan | Nanoparticles | Chimeric recombinant protein: EIT comprising crucial immunogenic segments of EspA, intimin, and Tir of EHEC and two key virulence factors (STX1B-IPAD) of S. dysenteriae | Oral or injection | Mice | [197] |

| Haemophilus influenzae (H. influenzae) | Human | Mannose-modified chitosan | Microparticles | Nontypeable H. influenzae (NTHi) outer membrane protein P6 | Intranasal | Mice | [179] |

| Mycobacterium tuberculosis (M. tuberculosis) | Human | Alginate-chitosan | Nanoparticles | PPE17, a surface localized protein displaying robust immunoreactivity in patients with active tuberculosis and represented as potent T-cell antigen and CpG | Intranasal or subcutaneous | Mice | [203] |

| Salmonella spp. | Chicken (broilers) | Chitosan | Nanoparticles | Outer membrane proteins (OMPs) and flagellin | Oral | Chickens | [62, 98, 232, 237] |

| Salmonella enterica (S. enterica) | Chicken (broilers) | Chitosan | Nanoparticles | Outer membrane proteins (OMPs) and flagellin | In-ovo | Chickens | [2] |

| S. enterica | Chicken (broilers) | Mannose-modified chitosan | Nanoparticles | Outer membrane proteins (OMPs) and flagellin | Oral | Chickens | [271] |

| S. enterica | Human | Chitosan | Nanoporous microparticles | Outer membrane proteins (OMPs) | Subcutaneous | Mice | [23] |

| S. enterica | Human | Chitosan | Nanoparticles | The tip protein of the Salmonella pathogenicity island 2 type III secretion system (SseB) fused with the LTA1 subunit of labile-toxin from enterotoxigenic E. coli, making the self-adjuvating antigen L-SseB | Intranasal | Mice rabbits | [58] |

| Shigella flexneri (S. flexneri) | Human | Trimethyl chitosan (TMC) | Nanoparticles | N-terminal region of IpaD antigen (NIpaD) | Oral | guinea pigs | [9] |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae (S. pneumoniae) | Human | Chitosan-maleimide | Nanocapsules | Pneumococcal surface adhesin A (PsaA) | Intranasal | - | [244] |

| S. pneumoniae | Human | Chitosan | Nanoparticles | Semisynthetic glycoconjugate (GC) composed of a synthetic tetrasaccharide mimicking the S. pneumoniae serotype 14 capsular polysaccharide (CP14) linked to the Pneumococcal surface adhesin A (PsaA) | Subcutaneous | Mice | [228] |

|

Streptococcus pyogenes (S. pyogenes), group A streptococcus, GAS |

Human | Trimethyl chitosan (TMC) | Nanoparticles | Lipopeptide with B-cell epitope J8 and T-helper epitope PADRE | Intranasal | Mice | [207] |

| S. pyogenes | Human | Amphiphilic chitosan derivative (arginine and oleic acid conjugated to the free amino groups present in the chitosan) | Nanoparticles | KLH protein (a source of T helper cell epitopes) and lipidated M-protein derived B cell peptide epitope (lipoJ14) | subcutaneous | Mice | [254] |

The discussed vaccines are designed to prevent bacterial infections in humans, mammals or poultry. Among the vaccine candidates for humans, the proposed formulations are against non-typeable H. influenzae [179], M. tuberculosis [203], S. pneumoniae [228, 242] or S. pyogenes, also known as group A streptococci (GAS) [207, 254]. Another group involves bacteria responsible for life-threatening diarrhea in humans, such as enterohemorrhagic E. coli (EHEC) and Shigella spp. [9, 197], which are the leading causes of death in children under the age of five years worldwide [181]. Many of the described vaccines are linked to the prevention of diseases caused by zoonotic bacteria such as Bordetella bronchiseptica causing respiratory diseases in companion animals (mainly dogs and cats), or Brucella spp., which is often present in unpasteurized dairy products; poultry-origin Salmonella spp. [2, 23, 58, 62, 98, 161, 238, 270, 271], which is a major food-borne pathogen; the avian pathogenic E. coli (APEC) [193] C. jejuni [264, 265] and Ch. psittaci [158, 166, 326]. Vaccines against poultry-origin zoonotic pathogens have been designed for use in both humans and chickens to block bacterial colonization and prevent the transmission of pathogens to humans. One vaccine candidate was linked to a poultry disease, necrotic enteritis, caused by C. perfringens [10]. For some of these diseases, such as GAS-caused illnesses, no vaccines are currently available. In contrast, vaccines preventing pneumonia caused by S. pneumoniae are widely used in the clinic and have contributed to decreasing the number of pneumococcal infections worldwide. However, the available formulations offer protection to only some serotypes of S. pneumoniae, whereas the serotypes not included in the vaccine remain a threat to human health [228]. Finally, vaccines based on live attenuated bacteria or elementary bodies, for example, against Ch. psittaci, can cause disease in vaccinated animals [326] hence, new protein-based vaccines are needed, and promising candidates are presented in this section. Notably, in vivo studies were performed to determine the effectiveness of almost all proposed vaccines. In the case of human vaccines, animal models, such as mice, rabbits or guinea pigs, were used, whereas for poultry-dedicated vaccines, the model birds were chickens (Table 4).

Various proteins, usually recombinant proteins with immunogenic properties, have been loaded in chitosan as candidate vaccine formulations. The distinct outer membrane proteins (OMPs) were the most common, as summarized in Table 4. In many cases, such formulations contain several proteins, so-called protein cocktails, such as Omp10, Omp19, and malate dehydrogenase, in vaccines against B. abortus [262]. The use of protein cocktails can offer protection even from two different bacterial species, such as a vaccine against S. dysenteriae and EHEC, which is composed of two key virulence factors (STX1B-IPAD) of S. dysenteriae and a recombinant chimeric protein, rEIT, derived from crucial EHEC antigens (E. coli secretion protein A EspA), intimin, translocated intimin receptor (Tir)) [196]. Similarly, the fusion protein used in the vaccine against S. enterica contains the tip protein of the Salmonella pathogenicity island 2 type III secretion system (SseB) fused with the LTA1 subunit of labile toxin (LT) of enterotoxigenic E. coli. The LTA1 subunit is an adjuvant [58]. In some cases, the glycoconjugates or lipids were linked to proteins or peptides carrying the epitope. In a vaccine against S. pneumoniae, a synthetic tetrasaccharide that mimicked the capsular polysaccharide of S. pneumoniae serotype 14 was attached to pneumococcal surface protein A (PsaA) [228], whereas the vaccine against GAS contained peptides representing various epitopes linked with lipids [207, 254]. Interestingly, one report described formulations composed of a lipidated peptide conjugated to poly-L-glutamic acid (PGA), which, along with the lipid, functioned as an adjuvant. Moreover, the position of lipid attachment influenced the conformation of the peptide and the size of the produced chitosan nanoparticles [207]. Finally, larger structures, such as inactivated elementary bodies (EBs), were formulated in chitosan hydrogels as vaccines against C. psittaci. In contrast to live attenuated EBs, inactivated EBs are only marginally protective when used as vaccines. In the proposed formulation, the EBs were mixed with V. cholerae ghost (VCG) particles and a chitosan hydrogel solution, providing an effective adjuvant/delivery system [326]. VCGs represent empty bacterial cell envelopes lacking cytoplasmic contents and the cholera toxin [69]. Using inactivated EBs in VCG-chitosan improved their ability to trigger a protective immune response in chickens [227].

Notably, loading various antigens into chitosan often improves vaccine properties, as chitosan derivatives can act as adjuvants. A promising example is the vaccine against Brucella spp., where mannosylated chitosan improved the immune response to the vaccine [250]. In humans, the mannose residues present on antigens are recognized by specific mannose receptors located in the cell membranes of immune cells called APCs that trigger the activation of T lymphocytes. Hence, mannose residues in chitosan can also increase antigen presentation ability and improve the immune response [299]. Similar effects can be obtained by introducing groups that increase the positive charge of chitosan, such as the functionalization of chitosan with arginine, as was done in vaccines against GAS. The presence of arginine in the chitosan-based vaccine improved the interaction with APCs. In addition to arginine, chitosan was also modified with oleic acid; thus, the resulting chitosan derivative exhibited amphiphilic characteristics. Oleic acid has immunostimulant properties; hence, its introduction to chitosan further improved the immunogenic potential of the proposed vaccine [254]. The recent study by Zhao et al. reports the sucralfate acidified (SA) encapsulated N-2-hydroxypropyl trimethyl ammonium chloride chitosan (N-2-HACC) / N,O-carboxymethyl chitosan (CMCS) nanoparticles which were designed to work as adjuvant. In this model, bovine serum albumin (BSA) was used as an antigen. It was proved that such nanoparticles were highly stable in simulated gastric juice and intestinal fluid. The in vivo studies were performed in the guinea pig model. The vaccine was administrated orally and it significantly enhanced the residence time of BSA in the intestine up to more than 12 h. Additionally, it elicited the production of IgG and sIgA [322]. Notably, chitosan nanoparticles and emulsions were proposed as systems that can serve as adjuvants. Such an example is chitosan hydrochloride-stabilized Pickering emulsion (CHSPE) which was tested along with a lumazine synthase isolated from Brucella representing the antigen. CHSPE induced antigen-specific antibody levels, increased the ratio of central memory T cells (TCM) and effector memory T cells (TEM), and promoted the secretion of Th1-type cytokines. These effects were highly comparable to a commercial adjuvant ISA 206 [304].