Abstract

Sugar alcohols, also known as glycitols, are reduced derivatives of sugars with multiple hydroxyl groups attached to the sugar skeleton. While classified as carbohydrates, they differ from monosaccharides by lacking an aldehyde or keto group. Glycitols are naturally abundant in various organisms and can also be synthesized industrially. These compounds possess unique physical and chemical properties, enabling them to function as compatible solutes, regulating cellular water balance and providing protection against stress. This mini-review explores the biosynthesis and roles of key glycitols, such as inositols, pinitol, and mannitol, in plants, focusing on their functions under environmental stresses, particularly drought. Furthermore, it discusses the potential application of these sugar alcohols in improving the production and resilience of tree seedlings, which is critical in the context of climate change. This paper highlights the need for further research into the role of glycitols in stress response, particularly for tree seedlings, to enhance nursery practices and forest regeneration.

Keywords: Sugar alcohols, Glycitols, Cyclitols, Inositols, Pinitol, Mannitol, Biosynthesis, Tree seedlings, Drought response

Introduction

Glycitols, also known as sugar alcohols, alditols, or polyols, are sugar derivatives that result from the reduction of aldehyde or ketone groups in monosaccharides [1]. These compounds are synthesized by various organisms under both normal and stress conditions. They are also produced industrially by hydrogenating sugars, a process that involves the addition of hydrogen to the sugar molecule, resulting in the formation of glycitols. Unlike monosaccharides like glucose and fructose, which contain reactive aldehyde or ketone groups, glycitols possess only hydroxyl groups, at least three of them, each attached to a different carbon atom of the sugar skeleton, enhancing their stability and allowing them to protect cellular components under stress [2]. Cyclitols, such as inositols and pinitol, contain a cyclic hexane ring, while mannitol, sorbitol, and galactitol are linear glycitols [3, 4]. Nevertheless, some authors distinguish between these by referring to cyclic sugar alcohols (e.g., pinitol, inositol) as polyols or cyclic polyols, and to acyclic sugar alcohols (e.g., mannitol) as glycitols [1, 5, 6]. Glycitols have unique physical and chemical properties allowing them to function as compatible solutes, helping cells maintain water balance and protecting enzymes from degradation during environmental stress. Among all glycitols, inositols, pinitol, and mannitol have been extensively studied for their biological functions in plants, fungi, and bacteria. In recent years, the focus has shifted towards understanding their roles in plant stress response mechanisms, particularly under conditions such as drought, salinity, and temperature extremes. In this paper, we review the chemical structure, biosynthesis, and biological functions of glycitols (myo-inositol, pinitol, and mannitol) in plants. We also discuss their roles alongside other critical plant processes influencing plant, particularly tree seedlings responses to abiotic stress with a focus on drought.

Chemical structures of monosaccharides and sugar alcohols

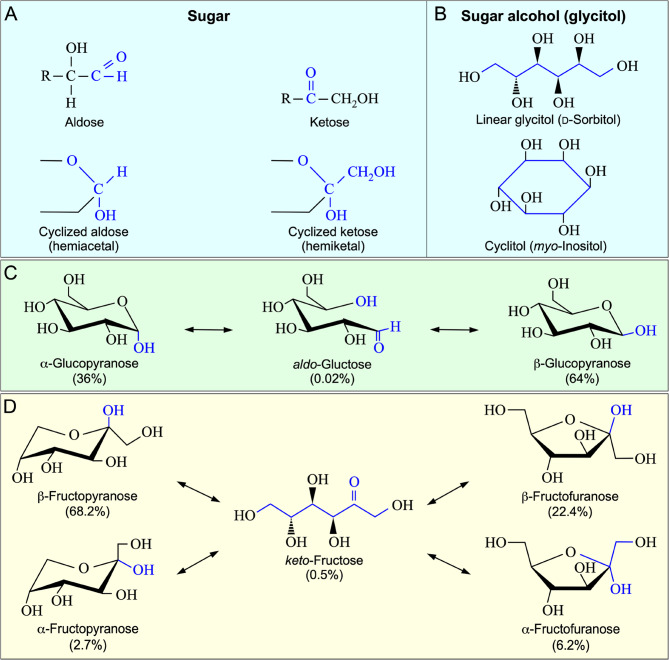

Monosaccharides such as glucose and fructose are characterized by the presence of reactive aldehyde or ketone groups, enabling cyclization into hemiacetal or hemiketal structures in solution (Fig. 1). This structural variability allows for rapid reactivity and energy release. In contrast, glycitols, which are the reduced forms of their respective monosaccharides, lack such reactive groups and are therefore more chemically stable. This stability is key to their role in stress tolerance, particularly in maintaining cell turgor and exerting unique protective functions to enzymes and reactants inside the cell, especially under stress conditions such as drought.

Fig. 1.

Comparison of monosaccharides and their corresponding sugar alcohols. A Monosaccharides can be either aldoses or ketoses. The presence of an aldehyde or keto group in monosaccharides with a molecular skeleton of longer than 5 carbons allow the linear sugar molecules to cyclize into hemiacetal or hemiketal structures in solution. B Sugar alcohols, or glycitols, lack either an active aldehyde or keto group and cannot form intramolecular hemiacetal or hemiketal structures. They can exist either as a linear molecule, such as D-sorbitol, or in a cyclitol form, like myo-inositol. C In solution, D-glucose, a typical aldose, exists mainly in the cyclic α-glucopyranose and β-glucopyranose forms, with a trace amount in the linear form. D D-Fructose, representing a typical ketose, can form a 6-member ring (pyranose) or 5-menber ring (furanose). Thus, D-fructose in solution equilibrates among different forms with varying percentages

Glucose and fructose

Glucose is an aldose and contains an active aldehyde group at C1 position, while fructose, a ketose, possesses a ketone group at C2 position (Fig. 1). In solution, glucose and fructose exist both as a linear molecule and in different cyclized forms. The percentages of sugar molecules in a specific form are determined by their stability or Gibb free energy level. In solution, D-glucose, for example, equilibrates between the linear form (accounting only for 0.02%) and the cyclized α-anomer (36%) and β-anomer (64%). D-Fructose in solution forms both the cyclized 6-atom ring of pyranose and 5-atom ring of furanose and equilibrates among the linear form keto-D-fructose (0.5%), α-D-fructopyranose (2.7%), β-D-fructopyranose (68.2%), α-D-fructofuranose (6.2%), and β-D-fructofuranose (22.4%). In contrast, cyclitols exist in only one form and do not equilibrate among different cyclized anomers.

Inositols

Inositols are a family of hexahydroxy cyclohexane stereoisomers. Due to the six chiral centers in the ring of cyclohexane, there are 64 theoretically possible stereoisomers for inositols. However, only 9 stereoisomers have been charactered so far (Fig. 2), including 6 (myo-, scyllo-, muco-, D-chiro-, L-chiro-, and neo-inositol) identified in organisms and 3 (allo-, epi-, and cis-inositol) synthesized in laboratories [7, 8]. Two of the stereoisomers (D-chiro- and L-chiro-inositol) are a pair of enantiomers, whereas the remaining 7 isomers are optically inactive (i.e., meso compounds), because a plane of symmetry exists in these molecules. The quantities of the 6 naturally occurring inositols vary drastically from high to minimal levels in organisms [8]. Four inositol isomers are known to occur in plants, including myo-, scyllo-, D-chiro-, and L-chiro-inositol [7].

Fig. 2.

Chemical structures of inositols. Inositols are isomers of hexahydroxy cyclohexanes with each hydroxyl attached to one carbon of the hexane ring. Inositols have six stereogenic carbons that can generate 16 possible distinct stereoisomers. Most of them are meso compounds and some are optically active. Amyo-Inositol and D-chiro-inositol are most widely spread in different organisms and their cellular functions and pharmacological effects have been studied extensively. B Four additional isoforms (scyllo-, L-chiro-, muco-, and neo-) of inositols have been identified in different organisms. Four isoforms (myo-, D-chiro-, scyllo-, and L-chiro-), present in higher plants, are indicated in green background. C Three more isoforms (allo-, epi-, and cis-) have been synthesized in laboratories

In its most stable conformation, myo-inositol exists in the chair conformation, which has 5 hydroxyls (1-, 3-, 4-, 5-, and 6-OH) in the equatorial orientation and only one (2-OH) in the axial orientation. Because hydroxyls in the equatorial orientation are farthest apart from each other and have minimal steric interference, such a distribution pattern of hydroxyl groups allows myo-inositol to assume the chair conformation with the lowest Gibbs free energy. myo-Inositol and D-chiro-inositol are the most common inositol isomers in nature and play significant roles in many biological processes in all eukaryotes. myo-Inositol was originally identified in muscle extracts by German chemist Johann J Scherer in 1850, making it the earliest identified isomer of inositols [9].

Pinitol

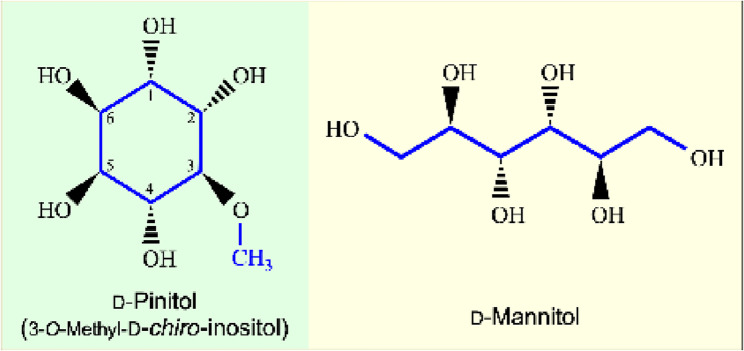

D-Pinitol is a methylated derivative of inositols, and its chemical name is 3-O-methyl-D-chiro-inositol (Fig. 3). D-Pinitol is a ubiquitous cyclitol in the Leguminosae and Pinaceae families. It is the most abundant inositol ether in plants [4].

Fig. 3.

Chemical structures of D-pinitol and D-mannitol. D-Pinitol (3-O-methyl- D-chiro-inositol) is a cyclitol and an ester derivative of D-chiro-inositol, whereas D-mannitol is a linear sugar alcohol and plays an important role in plants under stress

Mannitol

Mannitol is a linear molecule of 6-carbon sugar alcohol derived from the reduction of fructose [3] (Fig. 3). It is one of the most widely distributed soluble carbohydrates in various organisms. Mannitol is key end product of photosynthesis in many algae and higher plants and abundant in bacteria, yeasts, fungi, and plants [10]. D-Mannitol (C6H14O6) is an isomer of D-sorbitol and has a lower caloric value than sucrose [11].

Biosynthesis of glycitols

The production of glycitols, such as myo-inositol, pinitol, and galactinol, has been reviewed recently [12]. Their biosynthesis is highly regulated under various growth conditions, including light/dark cycles, food availability, and stress. Bacteria, fungi, and plants are capable of synthesizing glycitols through metabolic pathways. The biosynthesis of glycitols has been shown to be controlled by the availability of carbon and energy, as well as stress signals that stimulate the upregulation of the genes involved in the glycitol formation. Glycitol biosynthesis includes converting a monosaccharide into a sugar alcohol by the activity of enzymes. Depending on the species and the tissue, the biosynthesis of glycitols may vary in its specifics.

Biosynthesis of myo-inositol

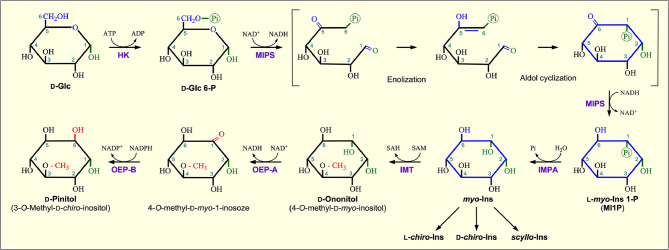

Cyclitols such as myo-inositol are more stable than their corresponding monosaccharides because cyclitol molecules contain a stable carbon ring and lack an acetal or keto group. Thus, the formation of the stable carbon ring is crucial for the biosynthesis of cyclitols. Four pathways have been proposed for the synthesis of different types of the initially produced cyclitols [12]. One of them involving myo-inositol phosphate (MIP) synthase (MIPS) is believed to be responsible for the synthesis of myo-inositol (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Biosynthesis of myo-inositol and D-pinitol. Plants synthesize myo-inositol through a de novo pathway from D-glucose (D-Glc) via glucose-6-phosphate (D-Glc 6-P) by the enzyme myo-inositol phosphate (MIP) synthase (MIPS). The reaction catalyzed by MIPS involves enolization and aldol cyclization of Glc-6-P into myo-inositol 1-phosphate (MI1P). Dephosphorylation of MI1P by inositol monophosphatase (IMPA) leads to production of free myo-inositol. O-Methylation of myo-inositol by inositol methyl transferase (IMT) produces an important cyclitol D-ononitol, which can be further converted to its epimer D-pinitol by consecutive reactions catalyzed by two D-ononitol epimerase enzymes (OEP-A and OEP-B). HK, hexokinase; SAM, S-adenosyl methionine; SAH, S-adenosyl homocysteine; OEP-A, NAD+-dependent D-ononitol dehydrogenase; OEP-B, NADP+-dependent D-pinitol dehydrogenase

In plants, myo-inositol (MI) is synthesized through a de novo pathway that involves the cyclization of D-glucose-6-phosphate (Glc-6-P) to L-myo-inositol-1-phosphate (MI1P) by myo-inositol-1-P synthase (MIPS) followed by dephosphorylation of MI1P by a specific MI monophosphatase [9]. Following is a summary of the inositol biosynthesis process in plants:

myo-Inositol-1-phosphate synthase (MIPS) converts glucose-6-phosphate (Glc 6-P) into myo-inositol-1-phosphate (MI1P).

The enzyme myo-inositol monophosphatase (IMPA) dephosphorylates myo-inositol-1-phosphate (MI1P) to produce myo-inositol (myo-Ins or MI).

The enzyme L-myo-inositol methyltransferase (IMT) catalyzes methylation of myo-inositol to D-ononitol in the presence of S-adenosyl methionine (SAM) as the methyl group donor.

D-Ononitol is converted to D-pinitol by consecutive reactions catalyzed by two epimerases, i.e., D-ononitol epimerase A and B (OEP-A and OEP-B).

Finally, the enzyme scyllo-inositol epimerase catalyzes epimerization of myo-inositol to produce scyllo-inositol [9, 12, 13].

The enzymes involved in the production of inositol, such as MIPS and IMPA, are found in the cytoplasm of plant cells as demonstrated in Arabidopsis thaliana through subcellular fractionation and immunofluorescence methods [14]. Yet, once inositol is generated, it can be transferred to different cellular organelles, such as the Golgi apparatus and chloroplasts, where it may play crucial roles in lipid metabolism and signaling. myo-Inositol serves as the backbone of phytic acid, also known as inositol hexakisphosphate (InsP6), the most abundant organic phosphate in soils [15, 16]. Its release from phytic acid by phytase enzymes not only supplies phosphate but also generates free inositol, which plays a critical role in cellular processes such as signal transduction, osmotic regulation, and phosphate homeostasis. In addition to being synthesized within plants, myo-inositol can be absorbed by plant roots from the soil, where it influences root physiology, phosphate acquisition, and osmotic balance. Furthermore, free inositol in the soil supports microbial activity, including mycorrhizal fungi, rhizosphere yeasts, and inositol-auxotrophic microorganisms, potentially mediating beneficial plant-microbe interactions and contributing to soil phosphate cycles [16].

Biosynthesis of pinitol

D-Pinitol (3-O-methyl-D-chiro-inositol), a highly ubiquitous cyclitol in the Leguminosae family, provides the most exhaustive characterization of cyclitol production [17]. D-Pinitol is the most abundant sugar alcohol in many Leguminosae species including Glycine max (soybean). The biosynthetic pathway of D-pinitol is an intricate process and starts with glucose-6-phosphate as a precursor and involves three main enzymes and a series of epimerases (Fig. 4). While many stages can lead to the synthesis of D-ononitol (4-O-methyl-D-myo-inositol) [4, 17, 18], in angiosperms it is mainly derived from myo-inositol. The production of D-pinitol from D-ononitol is achieved via the activities of a pair of D-ononitol epimerases (OEP-A and OEP-B) in the presence of NAD+ and NADPH as cofactors. Thus, D-pinitol is synthesized from glucose-6-phosphate via myo-inositol and D-ononitol.

D-Pinitol is synthesized in both the cytosol and chloroplasts of plant cells. Photosynthesis creates the precursor, glucose-6-phosphate, for the synthesis of D-pinitol in the chloroplast. In the cytosol, inositol-1-phosphate synthase and inositol monophosphatase catalyze the conversion of glucose-6-phosphate to myo-inositol. myo-Inositol is returned to the chloroplast, where it is transformed into D-pinitol. MI epimerase, D-chiro-inositol (DCI) dehydrogenase, and pinitol O-methyltransferase have been demonstrated to be localized in the chloroplast [13].

In gymnosperms, D-pinitol is produced via a distinct biosynthetic route. While D-pinitol is synthesized via D-ononitol (4-O-methyl-D-myo-inositol) [13] in angiosperms, its biosynthetic route involves sequoyitol (5-O-methyl-D-myo-inositol) in gymnosperms [19].

Biosynthesis of mannitol

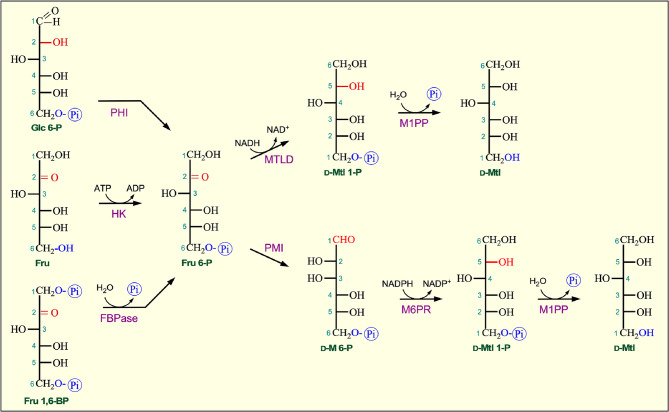

Mannitol, occurring abundantly in algae, is regularly found in plants and has been recognized in at least 70 higher plant families. It is a major carbohydrate in several dicot families, including Scrophulariaceae, Oleaceae, Rubiaceae, and Apiaceae [1, 20]. The biosynthesis process of mannitol in plants warrants more future studies as it varies between plant species. In the pathway, the enzyme mannitol-1-phosphate 5-dehydrogenase (MTLD) converts fructose-6-phosphate to D-mannitol-1-phosphate (D-Mtl 1P) in the presence of NADH (Fig. 5). Mannitol-1-phosphate is then converted to D-mannitol by the enzyme D-mannitol-1-phosphatase (M1PP) in plants [1, 21].

Fig. 5.

Biosynthesis of D-mannitol. The direct substrate for D-mannitol biosynthesis is D-fructose 6-phosphate (Fru 6-P), which is derived mainly from isomerization of glucose 6-phosphate (Glc 6-P), phosphorylation of fructose (Fru), and dephosphorylation of fructose 1,6-bisphosphate (Fru 1,6-BP). D-Fructose 6-phosphate is first reduced to D-mannitol 1-phosphate (D-Mtl 1P), followed by its dephosphorylation to produce D-mannitol (D-Mtl). PHI, phosphohexose isomerase; HK, hexokinase; FBPase, fructose 1,6-bisphosphatase; MTLD, D-mannitol 1-P dehydrogenase; M1PP, D-mannitol-1-phosphatase; PMI, phosphomannose isomerase; M6PR, D-mannose-1-phosphate reductase

In mature leaves, mannitol is mainly synthesized from fructose-6-phosphate to D-mannose 6-P (D-M6P) by phosphomannose isomerase (PMI). D-M6P is then reduced to D-mannitol-1-phosphate (D-Mtl1P) by NADPH-dependent D-mannose-6-phosphate reductase (M6PR) followed by the phosphatase (M1PP) to produce D-mannitol (Fig. 5) [22]. D-Mannitol can be transported from the source tissues such as leaves to the sink tissues, where it is converted back to D-mannose by NAD+-dependent D-mannitol dehydrogenase (MtlD). The use of mannitol is spatially isolated from its synthesis, and D-mannitol dehydrogenase activity is not observed in the source tissues (mature leaves) but is abundant in the sink tissues and in cell suspension cultures. Mannitol dehydrogenase is the initial step for translocated mannitol to enter the tricarboxylic acid cycle as a carbon and energy source [22]. Other studies have reported that some plants might utilize alternate mannitol production pathways, including enzymes such as hexokinase and phosphomannose isomerase [23].

In bacteria and fungi, mannitol biosynthesis involves the enzyme mannitol dehydrogenase (MDH) to transform fructose into mannitol (MDH). MDH can utilize either NADH or NADPH as a cofactor to catalyze the fructose-to-mannitol conversion [11].

Biological functions of glycitols in plants particularly tree seedlings

Glycitols represent a major highly reduced sink in which plants may store and transport carbon compounds [24]. Cyclitols are frequently produced in response to environmental stressors like drought, high salt concentrations, and extreme temperatures. They serve as compatible solutes, energy storage compounds, and signaling molecules that help the plant survive and recover from these stresses. Glycitols have unique physical and chemical properties to serve as compatible solutes that help cells control their water balance and protect them from different kinds of stress [2, 7, 8]. Albeit numerous studies have been conducted to understand the biological functions of certain glycitols in plants, particularly crops, scant attention has been devoted to comprehending the dynamics behaviors of glycitols in tree seedlings [23–25]. Trees are uniquely different than crop species specifically because of their long life span, achievement of large size at maturity, and thus exposure to considerable environmental variability throughout their life. The seedling stage of tree development is particularly sensitive to environmental extremes due to their small mass.

Mannitol

Mannitol plays a critical role as a mobile carbon form in certain crops, such as celery (Apium graveolens) and olive (Olea europea), where it can accumulate through de novo synthesis or by absorption from the soil. This accumulation is in response to various environmental stressors, including drought, salinity, and high temperatures [1, 22]. In 5-year-old oak trees (Quercus robur), mannitol serves a crucial role in adaptation to prolonged drought conditions, acting as a stable osmolyte and enhancing plant resilience during multiple growing seasons. Conversely, under short-term drought stress, plants tend to accumulate other carbohydrates, such as glucose, fructose, and galactose [26–28]. This shift suggests that mannitol plays a unique role in preventing water loss in plant during extended periods of water scarcity. However, it remains unclear whether drought resistant conifer seedlings, such as Douglas-fir or other pines, accumulate stable osmolytes, particularly mannitol or other glycitols, under prolonged drought stress, or whether they produce such osmoprotectants in significant amounts [26] to cope with water stress. The presence of mannitol helps decrease water potential while increasing the cell’s osmotic pressure, maintaining turgor and reducing water loss under drought conditions. Additionally, mannitol also acts as an antioxidant, scavenging reactive oxygen species (ROS) and protecting cells from oxidative damage [21, 29, 30]. Under drought conditions, mannitol and other glycitols may mimic water molecules, creating an artificial hydration sphere around macromolecules [31–33]. This adjustment helps to maintain cell turgor and prevent water loss particularly when the plant is subjected to water deficit conditions [32, 34]. This action aids in the regulation of cellular hydration and enhance plant’s ability to withstand drought stress.

myo-Inositol

myo-Inositol metabolism is highly dynamic and varies under different growth conditions, especially in response to water deficit. As a compatible solute, myo-inositol helps reduce reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels within cells, thereby defending against oxidative stress [34]. Inositol derivatives are also critical in calcium signaling, facilitating intercellular communication in stoma guard cells and roots [27–29]. These compounds participate in signal transduction, enabling plants to synchronize their responses to environmental cues, such as drought or temperature changes [35]. Furthermore, myo-inositol contributes to the activation of stress-response genes, helping plants adjust to stressful environments [34, 36].

Recent research has revealed the significant ecological role of myo-inositol in nutrient cycles. When phytic acid in soils is broken down by phytases, myo-inositol is released and becomes a crucial component of the organic phosphate cycle. This process connects carbon and phosphate dynamics within ecosystems [16]. myo-Inositol serves a dual purpose by acting as a metabolic intermediary in plants and playing a vital role in soil nutrient cycling. For instance, when plant roots take up inositol, it not only supports intracellular signaling but may also enhance phosphate acquisition. This coordinated response helps plants manage nutrient limitations and water shortages effectively.

Studies on Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii) and Eucalyptus species have shown notable variations in myo-inositol metabolism under drought conditions. For example, It is shown that myo-inositol concentrations are elevated significantly in both coastal (var. menziesii) and interior (var. glauca) variants of Douglas-fir seedlings subjected to drought stress [26]. This accumulation is found to be accompanied by the upregulation of genes involved in myo-inositol biosynthesis, indicating that these plants actively produce myo-inositol to adapt to water scarcity. myo-Inositol also serves as a signaling molecule, potentially activating pathways critical for stress response [37, 38]. It has been demonstrated that under drought stress, Douglas-fir seedlings prioritize the production of pinitol and ononitol, while reducing the availability of precursors like myo-inositol for other metabolic processes [39]. This shift in metabolic priorities allows the plants to optimize their biochemical pathways for drought resilience, even if it limits other functions.

In Eucalyptus, different species exhibit distinct responses in sugar alcohol levels under water stress. In particular, Eucalyptus globulus and Eucalyptus ovata are found to increase myo-inositol concentrations in both leaves and roots, while other species, such as Eucalyptus tereticornis, show no significant changes [27]. Additionally, water deficiency is found to reduce myo-inositol and D-chiro-inositol content in the roots of all species examined. These variations in inositol expression likely reflect eco-evolutionary adaptations, allowing species to thrive in diverse environments. The differences in myo-inositol metabolism among species suggest that metabolic adjustments are crucial for enhanced drought tolerance and long-term survival in challenging environments.

Pinitol

D-Pinitol concentrations vary significantly across different species and tissues, depending on environmental conditions. For example, de Simón et al. [40] have observed significant increases in pinitol concentrations, but not in myo-inositol, in the needles of both mature and juvenile Maritime pine (Pinus pinaster) trees subjected to drought stress. This highlights D-pinitol’s crucial role as an osmotic regulator during water scarcity. Several other species also accumulate D-pinitol in response to stress, including Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris), Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii), and species within Eucalyptus [27], Acacia, European larch (Larix decidua), Black spruce (Picea mariana), and Norway spruce (Picea abies). Other studies have also discovered increased pinitol levels in Norway spruce and Scots pine during drought conditions, further supporting the hypothesis that D-pinitol plays a vital role in osmotic adjustment and stress resilience [41, 42].

Interestingly, more lines of evidence have suggested that the induction of pinitol accumulation is not limited only to drought. Elevated autumn temperatures have been shown to promote pinitol accumulation in Eastern white pine (Pinus strobus) seedlings [25] and Sitka spruce (Picea sitchensis) [43]. This dual response to both drought and cold stress suggests an inverse relationship between susceptibility to cold damage and drought tolerance, with populations showing high drought tolerance often also exhibiting greater cold tolerance [44, 45].

Conclusion and future research direction

Glycitols, such as mannitol, myo-inositol, and pinitol, offer promising pathways for enhancing the drought resilience of plants. These compounds play key roles in regulating cellular water balance, scavenging reactive oxygen species (ROS), and facilitating osmotic adjustments during stress. Although their functions are well-studied in crop species, further research is necessary to better understand the specific biosynthesis, regulation, and distribution of glycitols in tree seedlings.

This review highlights the critical role of sugar alcohols, such as mannitol, pinitol, and myo-inositol, in enhancing drought tolerance in tree seedlings. The differential accumulation and internal distribution of glycitols, along with their functions as mobile carbon sinks or osmoprotectants, offer both structural and metabolic benefits during prolonged drought periods.

Recent discoveries on the stability of non-structural carbon (NSC) reserves in temperate forest trees underscore the importance of stable carbon allocation for stress resilience [46]. These findings align with the role of glycitols, suggesting their potential significance in supporting plant stress tolerance. Future research should build on these insights by investigating intra-plant transport, tissue-specific allocation, and the interactions of glycitols with other stress-related pathways. Additionally, practical applications, such as foliar applications of polyols and genetic engineering to enhance glycytols production, hold promise for improving seedling vigor and drought tolerance.

By synthesizing insights of recent discoveries from both crop and tree species, this review emphasizes the unique physiological roles of glycitols and their potential contributions to sustainable forestry practices. Advancing our understanding of glycitols will facilitate targeted strategies for producing resilient seedlings, which are essential for reforestation and ecosystem restoration in the face of climate change and increasing environmental variability.

Although it has been suggested that sugar alcohols may play only a minor quantitative role in the seasonal carbon distribution among stems, leaves, and branch wood in temperate forest trees, that study is focused on the significance of understanding NSC dynamics across different seasons [46]. The stable NSC concentrations, even during high-demand periods such as mast years, highlight the critical role of these reserves in supporting metabolic functions and resilience. In general, the role of glycitols under drought stress, particularly in tree seedlings, remains poorly understood.

Further research is needed to explore the inter- and intraspecific dynamics of glycitols in tree seedlings under drought conditions. Such studies could provide valuable insights into how glycitols contribute to stress tolerance and whether their role in carbon distribution changes in response to water deficits. Given the observed stability of NSCs across seasons and tree species, glycitols may play a more prominent role in specific developmental stages, such as seedling establishment, where carbon allocation and osmoprotection are crucial for survival under stress.

Authors’ contributions

VE designed, wrote the manuscript, and ZH reviewed and drew the figures; AN provided critical review of the manuscript and contributed to the writing process. All authors reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Funding

The authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Dominguez PG, Niittylä T. Mobile forms of carbon in trees: metabolism and transport. Tree Physiol. 2022;42(3):458–87. 10.1093/treephys/tpab123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kindl H, Scholda R, Hoffmann-Ostenhof O. The biosynthesis of cyclitols. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 1966;5(2):165–73. 10.1002/anie.196601651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kalsoom U, Bennett I, Boyce M. A review of extraction and analysis: methods for studying osmoregulants in plants. J Chromatogr Sep Tech. 2016;7:315. 10.4172/2157-7064.1000315.

- 4.Sánchez-Hidalgo M, León-González AJ, Gálvez-Peralta M, González-Mauraza NH, Martin-Cordero C. D-Pinitol: a cyclitol with versatile biological and Pharmacological activities. Phytochem Rev. 2021;20(1):211–24. 10.1007/s11101-020-09677-6. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ashraf M, Foolad MR. Roles of glycine betaine and proline in improving plant abiotic stress resistance. Environ Exp Bot. 2007;59(2):206–16. 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2005.12.006. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Choudhary S, Wani KI, Naeem M, Khan MMA, Aftab T. Cellular Responses, Osmotic Adjustments, and Role of Osmolytes in Providing Salt Stress Resilience in Higher Plants: Polyamines and Nitric Oxide Crosstalk. J Plant Growth Regul. 2023;42(2):539–53. 10.1007/s00344-022-10584-7. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anderson L, Wolter KE. Cyclitols in plants: biochemistry and physiology. Annu Rev Plant Physiol. 1966;17(1):209–22. 10.1146/annurev.pp.17.060166.001233. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Siracusa L, Napoli E, Ruberto G. Novel chemical and biological insights of inositol derivatives in mediterranean plants. Mol Basel Switz. 2022;27(5):1525. 10.3390/molecules27051525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Majumder AL, Biswas BB, editors. Biology of Inositols and phosphoinositides. In: Subcellular Biochemistry, no. V. 39. New York: Springer; 2006.

- 10.Song SH, Vieille C. Recent advances in the biological production of mannitol. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2009;84(1):55–62. 10.1007/s00253-009-2086-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martínez-Miranda JG, Chairez I, Durán-Páramo E. Mannitol Production by Heterofermentative Lactic Acid Bacteria: a Review. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2022;194(6):2762–95. 10.1007/s12010-022-03836-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kudo F, Eguchi T. Biosynthesis of cyclitols. Nat Prod Rep. 2022;39(8):1622–42. 10.1039/D2NP00024E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vernon DM, Bohnert HJ. A novel Methyl transferase induced by osmotic stress in the facultative halophyte Mesembryanthemum crystallinum. EMBO J. 1992;11(6):2077–85. 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05266.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Donahue JL, et al. The Arabidopsis thaliana myo-Inositol 1-Phosphate Synthase1 Gene Is Required for myo -inositol Synthesis and Suppression of Cell Death. Plant Cell. 2010;22(3):888–903. 10.1105/tpc.109.071779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen A, Zhu L, Arai Y. Enhanced and suppressed phosphorus mineralization by Ca complexation: NMR and CD spectroscopy investigation. Chemosphere. 2023;330:138761. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2023.138761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Su XB, Saiardi A. The role of inositol in the environmental organic phosphate cycle. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2024;90:103196. 10.1016/j.copbio.2024.103196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dumschott K, Dechorgnat J, Merchant A. Water deficit elicits a transcriptional response of genes governing D-pinitol biosynthesis in Soybean (Glycine max). Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:2411. 10.3390/ijms20102411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Streeter JG, Lohnes DG, Fioritto RJ. Patterns of pinitol accumulation in soybean plants and relationships to drought tolerance. Plant Cell Environ. 2001;24(4):429–38. 10.1046/j.1365-3040.2001.00690.x. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dittrich P, Kandler O. Biosynthesis of D-1-O-methyl-mucoinositol in gymnosperms. Phytochemistry. 1972;11(5):1729–32. 10.1016/0031-9422(72)85027-1.

- 20.Loescher WH, Tyson RH, Everard JD, Redgwell RJ, Bieleski RL. Mannitol synthesis in higher plants 1: evidence for the role and characterization of a NADPH-dependent mannose 6-phosphate reductase. Plant Physiol. 1992;98(4):1396–402. 10.1104/pp.98.4.1396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Upadhyay R, Meena M, Prasad V, Zehra A, Gupta V. Mannitol metabolism during pathogenic fungal–host interactions under stressed conditions. Front Microbiol. 2015;6:1019. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2015.01019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Stoop JMH, Williamson JD, Mason Pharr D. Mannitol metabolism in plants: a method for coping with stress. Trends Plant Sci. 1996;1(5):139–44. 10.1016/S1360-1385(96)80048-3. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hu L, et al. Plant phosphomannose isomerase as a selectable marker for rice transformation. Sci Rep. 2016;6:25921. 10.1038/srep25921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Merchant A, Richter AA. Polyols as biomarkers and bioindicators for 21st century plant breeding. Funct Plant Biol. 2011;38(12):934–40. 10.1071/FP11105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chang CY, Unda F, Zubilewich A, Mansfield SD, Ensminger I. Sensitivity of cold acclimation to elevated autumn temperature in field-grown Pinus strobus seedlings. Front Plant Sci. 2015;6:165. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2015.00165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Du B, et al. A coastal and an interior Douglas fir provenance exhibit different metabolic strategies to deal with drought stress. Tree Physiol. 2015;36:148–63. 10.1093/treephys/tpv105. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Merchant A, Tausz M, Arndt SK, Adams MA. Cyclitols and carbohydrates in leaves and roots of 13 Eucalyptus species suggest contrasting physiological responses to water deficit. Plant Cell Environ. 2006;29(11):2017–29. 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2006.01577.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Spieß N, et al. Ecophysiological and transcriptomic responses of oak (Quercus robur) to long-term drought exposure and rewatering. Environ Exp Bot. 2012;77:117–26. 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2011.11.010.

- 29.Pharr DM, et al. Regulation of mannitol dehydrogenase: relationship to plant growth and stress tolerance. 1999;34:1027–32. 10.21273/hortsci.34.6.1027.

- 30.Hema R, Vemanna RS, Sreeramulu S, Reddy CP, Senthil-Kumar M, Udayakumar M. Stable Expression of mtlD gene imparts multiple stress tolerance in finger millet. PLoS One. 2014;9(6):e99110. 10.1371/journal.pone.0099110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Dichio B, Margiotta G, Xiloyannis C, Bufo SA, Sofo A, Cataldi TRI. Changes in water status and osmolyte contents in leaves and roots of olive plants (Olea europaea L.) subjected to water deficit. Trees. 2009;23(2):247–56. 10.1007/s00468-008-0272-1. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mechri B, Tekaya M, Cheheb H, Hammami M. Determination of mannitol sorbitol and myo-inositol in olive tree roots and rhizospheric soil by gas chromatography and effect of severe drought conditions on their profiles. J Chromatogr Sci. 2015;53(10):1631–8. 10.1093/chromsci/bmv066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Conde A, Martins V, Noronha H, Conde C. Solute transport across plant cell membranes. Canal BQ. 2011;8:20–34.

- 34.Yildizli A, Çevik S, Ünyayar S. Effects of exogenous myo-inositol on leaf water status and oxidative stress of Capsicum annuum under drought stress. Acta Physiol Plant. 2018;40(6):122. 10.1007/s11738-018-2690-z. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Loewus FA, Murthy PPN. Myo-Inositol metabolism in plants. Plant Sci. 2000;150(1):1–19. 10.1016/S0168-9452(99)00150-8. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Riemer E, et al. Regulation of plant biotic interactions and abiotic stress responses by inositol polyphosphates. Front Plant Sci. 2022;13. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2022.944515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Perera IY, Hung C-Y, Moore CD, Stevenson-Paulik J, Boss WF. Transgenic arabidopsis plants expressing the type 1 inositol 5-phosphatase exhibit increased drought tolerance and altered abscisic acid signaling. Plant Cell. 2008;20:2876–93. 10.1105/tpc.108.061374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Zhai H, et al. A myo-inositol-1-phosphate synthase gene, IbMIPS1, enhances salt and drought tolerance and stem nematode resistance in Transgenic sweet potato. Plant Biotechnol J. 2016;14(2):592–602. 10.1111/pbi.12402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jansen K, et al. Douglas-Fir seedlings exhibit metabolic responses to increased temperature and atmospheric drought. PLOS One. 2014;9(12):e114165. 10.1371/journal.pone.0114165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.de Simón BF, Sanz M, Cervera MT, Pinto E, Aranda I, Cadahía E. Leaf metabolic response to water deficit in Pinus pinaster ait. Relies upon ontogeny and genotype. Environ Exp Bot. 2017;140:41–55. 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2017.05.017. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ivanov YV, Kartashov AV, Zlobin IE, Sarvin B, Stavrianidi AN, Kuznetsov VV. Water deficit-dependent changes in non-structural carbohydrate profiles, growth and mortality of pine and spruce seedlings in hydroculture. Environ Exp Bot. 2019;157:151–60. 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2018.10.016. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tomasella M, Häberle K-H, Nardini A, Hesse B, Machlet A, Matyssek R. Post-drought hydraulic recovery is accompanied by non-structural carbohydrate depletion in the stem wood of Norway spruce saplings. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):14308. 10.1038/s41598-017-14645-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Dauwe R, Holliday JA, Aitken SN, Mansfield SD. Metabolic dynamics during autumn cold acclimation within and among populations of Sitka Spruce (Picea sitchensis). New Phytol. 2012;194:192–205. 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2011.04027.x. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Bansal S, St. Clair JB, Harrington CA, Gould PJ. Impact of climate change on cold hardiness of Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii): environmental and genetic considerations. Glob Change Biol. 2015;21(10):3814–26. 10.1111/gcb.12958. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 45.Schreiber SG, Hacke UG, Hamann A, Thomas BR. Genetic variation of hydraulic and wood anatomical traits in hybrid Poplar and trembling Aspen. New Phytol. 2011;190(1):150–60. 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2010.03594.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hoch G, Richter A, Körner C. Non-structural carbon compounds in temperate forest trees. Plant Cell Environ. 2003;26(7):1067–81. 10.1046/j.0016-8025.2003.01032.x. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.