Abstract

LVNC (Left Ventricular Non-Compaction), which is a type of cardiomyopathy characterized by an abnormal heart muscle structure. Retinoic acid (RA) is crucial for normal heart development, including the regulation of myocardial differentiation and chamber formation. Cyp26b1 plays a key role in regulating RA signaling by degrading RA. However, more targeted research is needed to directly link Cyp26b1 with LVNC pathology. To explore the effect of Cyp26b1 on heart development, we collected heart tissues from wild type (WT) and Cyp26b1 knockout (KO) mice at four time points (E10.5-E13.5) and performed single-cell RNA sequencing. We obtained 134,499 high-quality cells (57,923 WT and 62,488 KO) after filtering. The data quality was confirmed through various evaluation index and analytical methods mapping rates. Our initial analysis identified 10 major cell types in hearts, and differential expression analysis revealed the transcriptional change after deletion of Cyp26b1, particularly in cardiomyocytes. Collectively, these data offer a valuable resource for researchers investigating the role of Cyp26b1 in heart development.

Subject terms: Disease model, Cell growth, Sequencing

Background & Summary

Myocardial trabeculation and compaction are a series of important and complex processes involved in during heart development that require subtle interactions among various cell types. Left ventricular non-compaction (LVNC) is a rare and inherited cardiomyopathy characterized by a trabeculated myocardial structure resulting from an interruption in the normal compaction process during embryonic development. LVNC may occur in isolation or in association with other congenital heart defects, genetic syndromes, or neuromuscular disorders. This condition is associated with progressive cardiac dysfunction, arrhythmias, thromboembolic, and sudden cardiac death1–3. The etiology of LVNC is largely unknown due to the lack of studies of genes and regulatory factors clearly associated with the LVNC phenotype. Notably, 42% of cases demonstrate familial inheritance patterns, strongly implicating genetic determinants in disease pathogenesis4. LVNC is increasingly recognized as a genetically heterogeneous condition linked to mutations, and variants in genes encoding sarcomeric, cytoskeletal, and ion channel proteins, such as MYH7, TTN, and TAZ, have been implicated in its pathogenesis5,6.

Recent evidence has expanded our understanding of LVNC by implicating developmental signaling pathways—particularly those involving retinoic acid (RA)—in its pathogenesis. RA, a bioactive derivative of vitamin A, is crucial for proper heart development, regulating the expression of genes essential for cardiomyocyte differentiation and myocardial compaction7. Experimental studies have shown that altered RA levels during embryogenesis can lead to abnormal trabeculation and impaired ventricular compaction, suggesting that dysregulated RA signaling may contribute to the development of LVNC8,9. Cyp26b1 is a member of the cytochrome P450 family of enzymes and metabolizes RA into easily degraded derivatives. An exome-wide association study of human demonstrated that a genetic variant in CYP26B1 enhanced the catabolic activity for RA10. Loss of Cyp26 function in humans is related with numerous cardiovascular defects11. Global knockout of Cyp26b1 in mice results in upregulation of RA target genes, indicating the RA-dependent roles of Cyp26b1. Cyp26b1−/− hearts display abnormally enlarged aortic valve leaflets12. However, it is insufficient characterization of molecular mechanisms governing myocardial compaction during ventricular development, coupled with limited understanding of Cyp26b1 in LVNC.

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) offers an unprecedented opportunity to dissect the cellular complexity and dynamic gene expression changes occurring during cardiac development. Recent studies have applied scRNA-seq to study abnormal cardiogenesis, focusing on the shift of the composition of cell populations and transcriptional signature13–15. To better understand the transcriptomic changes due to the deletion of Cyp26b1, we generated Cyp26b1 knockout (KO) mice and performed scRNA-seq experiments on both wild type (WT) and KO mouse models at key stages of trabeculation, including embryonic day (E) 10.5, 11.5, 12.5 and 13.5. A schematic overview of the study workflow is provided in Fig. 1. The extensive time-series data can be used to identify certain genes, metabolic pathways, signaling pathways, and regulatory mechanisms during heart development. It will help to understand how Cyp26b1 modulates the cell states in the developing heart, which can help better define the pathogenesis mechanisms and potentially offer novel therapeutic targets.

Fig. 1.

Schematic diagram of the single-cell RNA sequencing and bioinformatics workflow. (a) Main experimental processes. Embryo hearts of four time points (E10.5-E13.5) from WT and Cyp26b1 KO mice were collected for single-cell sequencing. (b) Data processing and analysis.

Methods

Mice and genotyping

Wild-type (WT) and Cyp26b1−/− (Cyp26b1 KO) C57Bl/6 J mice at four developmental stages, including E10.5, E11.5, E12.5 and E13.5 used in this study were purchased from GemPharmatech Co., Ltd (Nanjing, China). Cyp26b1 KO mice used in this study were generated via targeted deletion of exons 2 to 6 of the ENSMUST00000204146.2 transcript, based on Ensembl GRCm39 annotation. Genotypes of mice were confirmed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis, and the PCR primer sequences are listed in Table 1. Genomic DNA was extracted from yolk sac tissues of mouse embryos using a standard alkaline lysis method. Briefly, yolk sac tissues were lysed in an 70 μL of alkaline lysis buffer containing 50 mM NaOH by heating at 98°C for 30 minutes. The lysate was then neutralized with 10 μL 1.0 M Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) and centrifuged to remove debris. Two PCR reactions of the resulting supernatant containing genomic DNA were performed to determine the Cyp26b1 genotype. Reaction 1 utilized primers B2484 and B2485 to amplify both wild-type (WT, 14,967 bp) and knockout (KO, 383 bp) alleles. Reaction 2 employed primers B2486 and B2487 to specifically amplify the WT allele (328 bp). PCR products were analyzed on 1.5% agarose gels stained with ethidium bromide. After sacrificing the mice, the hearts were dissected. All animal experiments were performed in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Institutes of Health and approved by Ethics Committee of BGI (permit No. BGI-IRB A22047-T1).

Table 1.

Primer sequences for genotyping.

| PCR No. | Primer No. | Sequence | Band Size |

|---|---|---|---|

| PCR1 | B2484 | GACGTGTTCCTAGGAGACCAGGAC | WT: 14967 bp |

| B2485 | CAAGAGAGCTGCGGTGAGTACTG | KO: 383 bp | |

| PCR2 | B2486 | CTACTTTCTGTATTCCCTCCTTGTGG | WT: 328 bp |

| B2487 | CTGAGAGCCATGAGGGAAAAGC | KO: 0 bp |

Single cell isolation and suspension for scRNA-seq

The embryonic hearts from E11.5, E12.5, E13.5 and E14.5 stages were dissected under a stereomicroscope. Due to the limited size of embryonic mouse hearts, particularly at early developmental stages, we employed a pooling strategy to ensure sufficient cell numbers and robust representation of cardiac cell types. For each experimental condition (genotype and time point), heart tissues from multiple littermate embryos were first rinsed with PBS and minced into small pieces approximately 3 × 3 × 3–5 × 5 × 5 mm3 using fine scissors. Minced tissues were pooled and digested for 1 h in DS-LT buffer (0.2 mg ml–1 CaCl2, 5 μM MgCl2, 0.2% BSA and 0.2 mg ml–1 Liberase in HBSS) at 37 °C, then was stopped by adding 3 ml of FBS. Samples were filtered through a 40-μm cell strainer and centrifuged at 500 × g for 5 min at 4 °C. Cell viability is assessed using Trypan Blue exclusion staining. Only samples with high viability (>80%) are used for further experimental procedures. Finally, cells were resuspended in cell resuspension buffer (0.04% BSA in PBS) for library preparation.

scRNA-Seq library preparation and sequencing

The DNBelab C series Single-Cell Library Prep Set (MGI) was employed to prepare single-cell RNA-seq libraries as previously described16. In brief, individual cells were co-encapsulated with gel beads and partitioning oil to form gel bead-in-emulsions (GEMs). Cell lysis within GEMs releases RNA, which undergoes reverse transcription (RT) to generate barcoded cDNA. Then, the obtained cDNA was purified and amplified to generate sufficient material for library construction. The amplified barcoded cDNA was sheared into 200–300 bp fragments, followed by end-repaired, A-tailed, ligated to sequencing adaptor and index PCR amplified. The final libraries were sequncing on a DNBSEQ-T7 sequencer at the China National GeneBank with the sequencing strategy: 41-bp read length for read 1 and 100-bp read length for read 2.

Raw sequencing reads were first processed for quality filtering and adapter trimming using Fastp (version 0.23.2) with default parameters17. High-quality reads were aligned to the mouse reference genome (mm10) using STAR (version 2.7.11a)18. Next, the alignment output generated a cell versus gene unique molecular identifier (UMI) count matrix.

Quality control (QC)

To ensure the quality of scRNA-seq data, we performed rigorous QC steps. First, cells were filtered based on the following criteria: (1) Number of detected genes per cell: Cells with fewer than 500 genes were excluded to remove dead or low-quality cells. (2) Percentage of mitochondrial gene expression: Cells with mitochondrial gene expression exceeding 25% were discarded to eliminate stressed or apoptotic cells. Besides, genes expressed in fewer than 5 cells were removed from the dataset to exclude low-abundance transcripts and reduce noise. The potential doublets were removed using the DoubletFinder package (version 2.0.4)19. The expected doublet rate was estimated based on the number of recovered cells according to experimental settings. The baseline doublet rate for 1,000 cells was set at 0.8%. For each additional 1,000 cells, the doublet rate increased by 0.8%. The total estimated doublet rate (r) was calculated as:

where N represents the total number of recovered cells. The optimal pK parameter was determined using the paramSweep_v3 and BCmetric functions. Artificial doublets were generated, and doublet scores were computed using the doubletFinder_v3 function. Cells with high doublet scores exceeding the calculated threshold were removed from the dataset.

Data integration, dimensionality reduction and clustering

For scRNA-seq data integration, we utilized the Seurat package (version 5.1.0) in R20. Gene expression data were first normalized using the LogNormalize method and scaled with the ScaleData function. Next, the top 5,000 highly variable genes (HVGs) were identified using the FindVariableFeatures function with the “vst” method. PCA was then performed on these HVGs using the RunPCA function. Following PCA, the Harmony21 algorithm (version 1.2.0) was applied to the PCA results to correct for batch effects and mitigate technological variability. Clustering was subsequently performed on the Harmony-adjusted principal components (using the first 50 PCs) via the FindNeighbors and FindClusters functions, with a resolution parameter of 0.2. Finally, dimensionality reduction for two-dimensional visualization was achieved using UMAP through the RunUMAP function.

Differential expression gene and functional enrichment analysis

For differential expression gene (DEG) analysis, we identified DEGs between two genotypes across different time points and cell types using the FindMarkers function of Seurat package (version 5.1.0) with the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. The significance threshold was set at |log2(foldchange)| ≥ 0.5 and adjusted p-values < 0.05. For functional enrichment analysis, we performed Gene Ontology (GO) pathway enrichment using the enrichGO function of clusterProfiler package (version 4.10.0)22. Terms with an adjusted p-values < 0.05 were considered significantly enriched. The results were visualized using the ggplot2 packages (version 3.5.1).

Data Records

The raw FASTQ files of the scRNA-seq data have been deposited in the CNGB Nucleotide Sequence Archive (CNSA) under accession number CNP000700723. This dataset includes scRNA-seq data from E10.5, E11.5, E12.5, and E13.5 embryonic mouse hearts from both Cyp26b1 KO and WT samples. Detailed file descriptions are provided in Supplementary Table S324. Moreover, the processed and integrated RDS file, along with metadata and all supplementary tables, have been deposited in Figshare (10.6084/m9.figshare.29088062)24.

Technical Validation

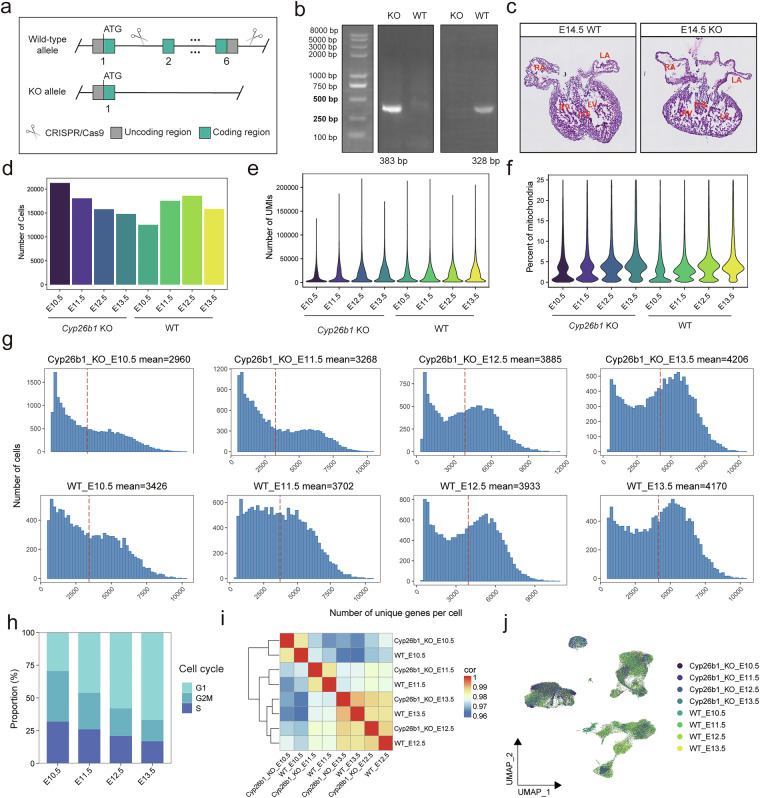

Figure 1 provides an overview of the experimental design (Fig. 1a), and the raw data were processed via the bioinformatics workflow (Fig. 1b). The Cyp26b1 heterozygous mice (Cyp26b1+/−) model were generated using CRISPR/Cas9-mediated deletion exons 2 to 6 of Cyp26b1 gene (Fig. 2a). Heterozygous animals were then intercrossed to obtain homozygous knockout (Cyp26b1−/−) embryos. The genotype of the offspring was confirmed by PCR genotyping (Fig. 2b). Cyp26b1−/− mice only displayed a single KO band of 383 bp, whereas Cyp26b+/+ mice showed a single WT band of 328 bp (Fig. 2b). Abnormal heart development, characterized by left ventricular non-compaction, was observed in the KO embryo at E14.5, as revealed by hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining (Fig. 2c). For each group and developmental stage, hearts from multiple embryos were pooled prior to single-cell RNA sequencing, and the detailed information on the number of pooled samples, library name and library quality of each sample from different groups was listed in Table 2. The estimated number of cells per sequencing library detected in WT groups and KO groups were 10,695 and 12,120, the mean UMIs detected in each cell were 20,784 and 20,312, and the average gene counts per cell were 3,727 and 3,575, respectively. The total raw reads in each library were ranged from 1,348 M to 2,499 M (Table 3). When considering the alignment of reads, the highest alignment rate of the reference genome was observed in exonic regions, with markedly lower mapping proportions detected in intronic and intergenic regions (Table 3). This pattern strongly suggests that the sequenced data are predominantly RNA-derived, consistent with transcriptional origin. These indicators evidenced the reliability of our sequencing data.

Fig. 2.

Quality of the scRNA-seq dataset. (a) Schematic diagram of constructing Cyp26b1 global knockout mouse line with CRISPR/Cas9 technology. (b) Genotype validation of mice by PCR. WT: Wild type mice; KO: Knock out mice. (c) Representative H&E staining images of KO and WT cardiac coronal maximum section at E14.5. LA: Left atria; RA: Right atria; LA: Left ventricle; RA: Right ventricle; IVS: Interventricular septum. (d) Bar plot showing the cell numbers per sample. (e,f) Violin plots showing the number of unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) detected per cell (e) and the percentage of counts from mitochondrial genes (f), split by sample. (g) Bar plots showing the distribution of the number of unique genes per cell, across various samples. (h) Bar plot showing the estimated cell cycle phases across different time points. (i) Heatmap clustering of correlation coefficients across different samples. (j) UMAP plot showing the cell cluster distribution across the different samples.

Table 2.

Barcode, RNA, UMI sequence quality control.

| SampleName | SampleNumber | LibName | Cell number | Mean UMIs per cell | Mean genes per cell |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT_E10.5 | 2 | cDNA-9553-1-221207 | 8014 | 19265 | 3234 |

| cDNA-9553-2-221207 | 7585 | 20266 | 3385 | ||

| WT_E11.5 | 2 | cDNA-9469-1-221130 | 11329 | 20160 | 3813 |

| cDNA-9469-2-221130 | 11088 | 20973 | 3751 | ||

| WT_E12.5 | 3 | cDNA-9498-1-221202 | 12397 | 19896 | 3843 |

| cDNA-9498-2-221202 | 12898 | 21882 | 3964 | ||

| WT_E13.5 | 8 | cDNA-9504-1-221202 | 11579 | 21281 | 3900 |

| cDNA-9504-2-221202 | 10672 | 22551 | 3928 | ||

| Cyp26b1_KO_E10.5 | 7 | cDNA-9546-1-221207 | 15291 | 17820 | 3320 |

| cDNA-9546-2-221207 | 14261 | 16953 | 3279 | ||

| Cyp26b1_KO_E11.5 | 11 | cDNA-9471-1-221130 | 12723 | 21684 | 3511 |

| cDNA-9471-2-221130 | 12297 | 19624 | 3320 | ||

| Cyp26b1_KO_E12.5 | 3 | cDNA-9501-1-221202 | 11836 | 22978 | 3994 |

| cDNA-9501-2-221202 | 8469 | 21090 | 3552 | ||

| Cyp26b1_KO_E13.5 | 4 | cDNA-9512-1-221202 | 11630 | 21074 | 3772 |

| cDNA-9512-2-221202 | 10452 | 21273 | 3855 |

Table 3.

Reference genome alignment.

| SampleName | LibName | Raw Data reads (M) | PassQC reads (M) | mapping rate to Genome | mapping rate to Exon | mapping rate to Inter |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT_E10.5 | cDNA-9553-1-221207 | 1409.95 | 1302.49 | 92.14% | 87.30% | 9.80% |

| cDNA-9553-2-221207 | 1348.55 | 1233.27 | 89.27% | 88.10% | 9.20% | |

| WT_E11.5 | cDNA-9469-1-221130 | 1957.15 | 1829.66 | 94.81% | 86.70% | 9.70% |

| cDNA-9469-2-221130 | 1987.69 | 1848.65 | 93.60% | 85.60% | 10.50% | |

| WT_E12.5 | cDNA-9498-1-221202 | 1744.68 | 1625.74 | 95.68% | 87.90% | 9.30% |

| cDNA-9498-2-221202 | 2365.2 | 2207.64 | 95.10% | 86.70% | 10.20% | |

| WT_E13.5 | cDNA-9504-1-221202 | 2284.01 | 2137.1 | 96.54% | 87.20% | 9.80% |

| cDNA-9504-2-221202 | 2267.89 | 2118.02 | 96.20% | 86.30% | 10.50% | |

| Cyp26b1_KO_E10.5 | cDNA-9546-1-221207 | 1423.31 | 1327.37 | 94.27% | 90.20% | 7.60% |

| cDNA-9546-2-221207 | 1382.77 | 1293.08 | 94.75% | 90.70% | 7.20% | |

| Cyp26b1_KO_E11.5 | cDNA-9471-1-221130 | 1911.29 | 1779.52 | 93.86% | 87.60% | 9.20% |

| cDNA-9471-2-221130 | 1835.04 | 1707.78 | 94.18% | 86.70% | 9.90% | |

| Cyp26b1_KO_E12.5 | cDNA-9501-1-221202 | 2499.17 | 2328.07 | 95.33% | 87.70% | 9.20% |

| cDNA-9501-2-221202 | 2340.75 | 2195.09 | 96.37% | 88.70% | 8.70% | |

| Cyp26b1_KO_E13.5 | cDNA-9512-1-221202 | 2124.5 | 1983.97 | 95.79% | 87.40% | 9.70% |

| cDNA-9512-2-221202 | 2070.39 | 1943.94 | 96.49% | 87.10% | 9.80% |

First, the doublets in the scRNA-seq data were predicted by DoubletFinder19 R package and were removed. Subsequently, we utilized Seurat20 for further filtering to ensure the high quality of the dataset. The low-quality cells with fewer than 500 genes or the percentage of mitochondrial genes greater than 25 and the genes expressed in fewer than 5 cells were removed. The counts of cell number per sample, UMIs and the proportion of mitochondrial genes in each cell were showed (Fig. 2d–f). The average number of genes of samples at eight groups are between 2,920 and 4,206 (Fig. 2g). The proportion of cells in the proliferative state decreased with time of development, which aligned with normal cardiac developmental biological events (Fig. 2h). The heatmap showed that all samples had strong correlations, especially between the samples at the same development time point, with Spearman’s correlation coefficients consistently above 0.96. The result indicated the sequencing quality of the two groups was high and comparable (Fig. 2i). The data were integrated and minimized the batch effect of samples for clustering by Harmony algorithm21 (Fig. 2j). Collectively, we generated a high-quality single-cell transcriptome dataset of hearts from WT and Cyp26b1 KO groups.

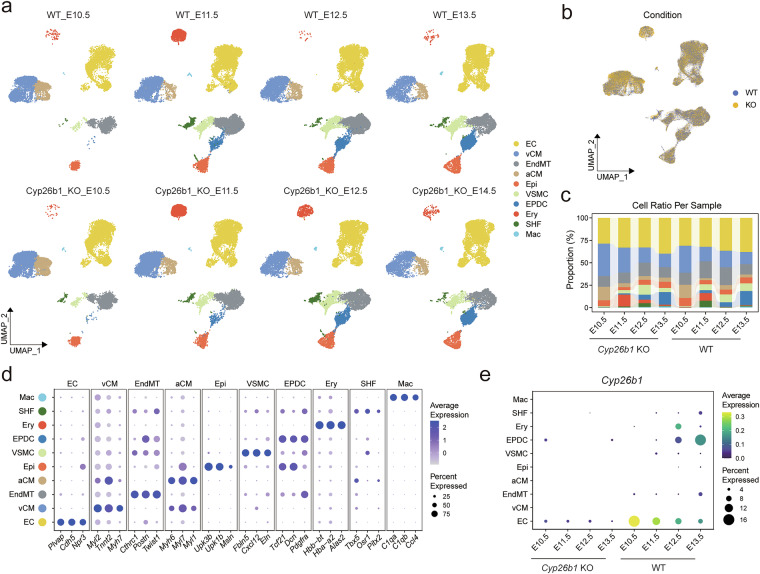

After quality control, a total of 134,499 high-quality cells were obtained to further analysis, with 57,923 and 62,488 cells in the WT and KO groups, respectively. To identify specific cell populations, we performed dimensionality reduction and unsupervised cell clustering using Seurat. Subsequently, we successfully revealed 10 distinct cell types expressing known markers of major cell types, including endothelial cells (EC), ventricular cardiomyocytes (vCM), endothelial to mesenchymal transition cells (EndMT), atrial cardiomyocytes (aCM), epithelial cells (Epi), vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMC), epicardium derived cells (EPDC), second heart field cells (SHF), erythrocytes (Ery) and macrophages (Mac) (Fig. 3a–d). The result was visualized by UMAP dimension reduction (Fig. 3a), consistent with the major cardiac cell populations identified in the present analysis25–27. In the Cyp26b1 KO hearts, similar major cell types were obtained compared with WT hearts (Fig. 3b). Cardiomyocytes were the most abundant cell population accounted for 28.77% of the total cell population, and the changes of cell type composition between WT and Cyp26b1 KO groups spanning different developmental time points were displayed (Fig. 3c). The expression levels of marker genes were specifically higher in certain cells compared with others (Fig. 3d). More details of gene expression associated with the 10 distinct cell types were listed in Supplementary Table S124. Notably, Cyp26b1 was mainly expressed in endothelial cells of WT group, and almost not expressed in KO group.

Fig. 3.

Cell types of the scRNA-seq data sets. (a) UMAP plot showing the classified cell types with different colors, split by different samples and time points. (b) UMAP plot showing the different genotypes . (c) Bar plot showing the percentage of cell types per group. Cell type colors are consistent with Fig. 3a. (d) Dot plot showing the known marker genes expressed by each cell type. (e) Dot plot showing the level of Cyp26b1 in each cell type of WT and KO mice hearts from different time points. EC: endothelial cells; vCM: ventricular cardiomyocytes; EndMT: endothelial to mesenchymal transition cells; aCM: atrial cardiomyocytes; Epi: epithelial cells; VSMC: vascular smooth muscle cells; EPDC: epicardium derived cells; SHF: second heart field cells; Ery: erythrocytes; Mac: macrophages.

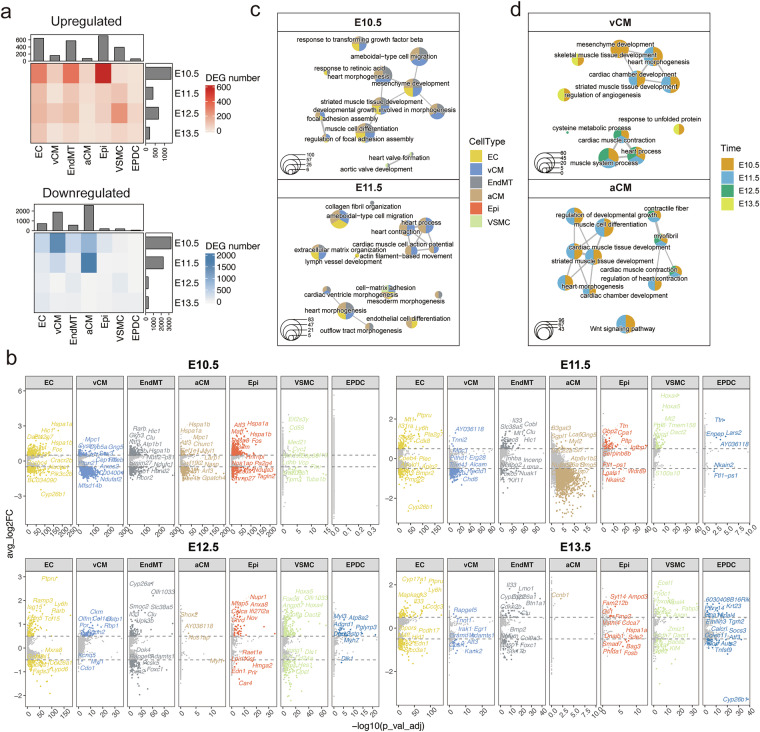

To further validate the effect of Cyp26b1 knockout on transcriptomic alterations during heart development, we performed differential expression gene analysis between WT and KO samples at each development time point and across various major cardiac cell types (Fig. 4a–d and Supplementary Table S224). Interestingly, we found that a large part of DEGs were concentrated in E10.5 and E11.5, and most were downregulated, particularly in vCM and aCM (Fig. 4a). As expected, Cyp26b1 was markedly downregulated in EC at E10.5 and E11.5 (Fig. 4b). The GO terms of downregulated genes were involved in heart morphogenesis, mesenchymal cell differentiation and connective tissue development, particularly in vCM, aCM, EC, and EndMT populations, suggesting the abnormal developmental processes after the deletion of Cyp26b1 (Fig. 4c). Notably, downregulated genes in E10.5 Cyp26b1 KO samples were enriched in the response to retinoic acid pathway, especially in EC and EndMT populations. This further supports the notion that RA signaling is perturbed in Cyp26b1 KO samples. The DEG analysis showed the altered transcriptional profiles of vCM and aCM in Cyp26b1 KO samples (Fig. 4a,b), which is consistent with the phenotype of impaired myocardial compaction observed in these embryos (Fig. 2c). Consequently, functional analysis showed the terms related to heart contraction and muscle cell differentiation were down regulated in vCM and aCM of KO samples, particularly in E10.5 and E11.5, suggesting Cyp26b1 plays an important role in cardiomyocyte differentiation and maturation (Fig. 4d).

Fig. 4.

Differential expression gene analysis. (a) Heatmap and bar plots showing the DEG number of upregulated (top) and downregulated (bottom) genes in different time points and cell types between WT and KO samples. (b) Volcano plots illustrate the upregulated and downregulated genes in different time points and cell types of KO samples compared to WT samples. (c) The GO enrichment analysis results of the downregulated genes in E10.5 (top) and E11.5 (bottom) of KO samples at major cell types. (d) The GO enrichment analysis results of the downregulated genes in vCM (top) and aCM (bottom) of KO samples at different time points. EndMT: endothelial to mesenchymal transition cells; vCM: ventricular cardiomyocytes; Epi: epithelial cells; EC: endothelial cells; aCM: atrial cardiomyocytes; VSMC: vascular smooth muscle cells; EPDC: epicardium derived cells.

In conclusion, we provide a high-quality single cell atlas of early hearts. Additionally, we reveal transcriptional changes at four time points and across different cell types under the deletion of Cyp26b1 conditions. The data set could be used to understand the mechanisms of Cyp26b1 in heart development as well as the discovery of key targets of LVNC.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

Thanks for the support of the China National GeneBank and the authors for their contributions. This work was supported by High-performance Computing Platform of YaZhou Bay Science and Technology City Advanced Computing Center (YZBSTCACC).

Author contributions

Z.Z. conceived the idea. L.P. collected the samples and performed the single-cell experiments. Z.Z. and X.C. analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. S.C. and S.S. uploaded the sequencing data and analysis code. X.F. and J.S. revised the manuscript. A final manuscript review and approval was completed by all authors.

Code availability

The custom scripts used for data input/output, integration, and differential expression analysis are available from Figshare at 10.6084/m9.figshare.2908806224.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Zhao Zhang, Xueting Chen.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41597-025-05497-5.

References

- 1.Paterick, T. E. & Tajik, A. J. Left Ventricular Noncompaction. Circulation Journal76, 1556–1562, 10.1253/circj.cj-12-0666 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arbustini, E., Weidemann, F. & Hall, J. L. Left ventricular noncompaction: a distinct cardiomyopathy or a trait shared by different cardiac diseases? Journal of the American College of Cardiology64, 1840–1850 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chin, T. K., Perloff, J. K., Williams, R. G., Jue, K. & Mohrmann, R. Isolated noncompaction of left ventricular myocardium. A study of eight cases. Circulation82, 507–513 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Casas, G. et al. P2250 Role of family screening and genetic testing in left ventricular noncompaction. 39, ehy565. P2250 (2018).

- 5.Towbin, J. A., Lorts, A. & Jefferies, J. L. Left ventricular non-compaction cardiomyopathy. The Lancet386, 813–825 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Waning, J. I. et al. Genetics, clinical features, and long-term outcome of noncompaction cardiomyopathy. Journal of the American College of Cardiology71, 711–722 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Niederreither, K. et al. Embryonic retinoic acid synthesis is essential for heart morphogenesis in the mouse. Development128, 1019–1031 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duester, G. Retinoic acid synthesis and signaling during early organogenesis. Cell134, 921–931 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Niederreither, K. & Dollé, P. Retinoic acid in development: towards an integrated view. Nature Reviews Genetics9, 541–553 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chang, J. et al. Exome-wide analyses identify low-frequency variant in CYP26B1 and additional coding variants associated with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Nature Genetics50, 338–343 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rydeen, A. B. & Waxman, J. S. Cyp26 enzymes are required to balance the cardiac and vascular lineages within the anterior lateral plate mesoderm. Development141, 1638–1648 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ahuja, N. et al. Endothelial Cyp26b1 restrains murine heart valve growth during development. Developmental Biology486, 81–95 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu, T. et al. PRDM16 is a compact myocardium-enriched transcription factor required to maintain compact myocardial cardiomyocyte identity in left ventricle. Circulation145, 586–602 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.George, R. M. et al. Single cell evaluation of endocardial Hand2 gene regulatory networks reveals HAND2-dependent pathways that impact cardiac morphogenesis. Development150, dev201341 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jang, J. et al. Endocardial HDAC3 is required for myocardial trabeculation. Nature Communications15, 4166 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Han, L. et al. Cell transcriptomic atlas of the non-human primate Macaca fascicularis. Nature604, 723–731 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen, S., Zhou, Y., Chen, Y. & Gu, J. fastp: an ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics34, i884–i890 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dobin, A. et al. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics29, 15–21 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McGinnis, C. S., Murrow, L. M. & Gartner, Z. J. DoubletFinder: doublet detection in single-cell RNA sequencing data using artificial nearest neighbors. Cell systems8, 329–337. e324 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Butler, A., Hoffman, P., Smibert, P., Papalexi, E. & Satija, R. Integrating single-cell transcriptomic data across different conditions, technologies, and species. Nature biotechnology36, 411–420 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Korsunsky, I. et al. Fast, sensitive and accurate integration of single-cell data with Harmony. Nature methods16, 1289–1296 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yu, G., Wang, L.-G., Han, Y. & He, Q.-Y. clusterProfiler: an R package for comparing biological themes among gene clusters. Omics: a journal of integrative biology16, 284–287 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.CNGB Nucleotide Sequence Archive.10.26036/CNP0007007 (2025).

- 24.Zhang, Z. Single-cell RNA sequencing dataset of hearts from wild type and Cyp26b1 knockout mouse embryos. 10.6084/m9.figshare.29088062 (2025). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Ren, H. et al. Single-cell RNA sequencing of murine hearts for studying the development of the cardiac conduction system. Scientific Data10, 577 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Farah, E. N. et al. Spatially organized cellular communities form the developing human heart. Nature627, 854–864 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cui, Y. et al. Single-cell transcriptome analysis maps the developmental track of the human heart. Cell reports26, 1934–1950. e1935 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- CNGB Nucleotide Sequence Archive.10.26036/CNP0007007 (2025).

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The custom scripts used for data input/output, integration, and differential expression analysis are available from Figshare at 10.6084/m9.figshare.2908806224.