Abstract

The helix-coil transition kinetics of an α-helical peptide were investigated by time-resolved infrared spectroscopy coupled with laser-induced temperature-jump initiation method. Specific isotope labeling of the amide carbonyl groups with 13C at selected residues was used to obtain site-specific information. The relaxation kinetics following a temperature jump, obtained by probing the amide I′ band of the peptide backbone, exhibit nonexponential behavior and are sensitive to both initial and final temperatures. These data are consistent with a conformation diffusion process on the folding energy landscape, in accord with a recent molecular dynamics simulation study.

The helix-coil transition represents the simplest scenario in protein folding (1–9), yet the details of its kinetics are not understood fully. The classical helix-coil transition theory describes the mechanism of helix formation as a sequence of events, starting from a so-called nucleation step where the first helical hydrogen bond, formed between the amide carbonyl of residue i and the amide hydrogen of residue i+4, is generated. The subsequent steps involve helix elongation by adding an extra hydrogen bond at either end of the preexisting helical turns. It has been argued that the nucleation process encounters the largest free energy barrier during the course of helix formation because three residues concomitantly lose their conformational entropy, whereas the propagation steps are energetically favorable because only one residue loses conformational entropy that is balanced by the energy generated from the formation of one extra hydrogen bond. Provided that the nucleation barrier is large enough (compared with those encountered by the propagation steps), a two-state scenario as well as transition-state theory remains effective to explain the dynamics of helix formation. Although recent experiments on the helix-coil transition employing laser-induced temperature-jump (T-jump) method (10–13) have shown that single exponential kinetics, which are characteristic of a two-state system, seem to be adequate to describe the transition between helix-containing and nonhelix-containing conformations, other studies involving theory and molecular dynamics (MD) simulations have suggested that the helix-coil transition may not follow first-order kinetics (14, 15). Another question that is also under debate involves the rate of the nucleation process. The T-jump data of infrared (10), fluorescence (11, 12), and Raman (13), as well as results from an NMR experiment (16) all suggest that the nucleation step takes place on a submicrosecond time scale, whereas a stopped-flow CD study (17) indicates that the nucleation process may be much slower, on millisecond time scales.

Recently, a new view of protein folding, based on statistical mechanical models of protein-like lattice or off-lattice polymers, has gained popularity in explaining protein folding dynamics, especially inhomogeneous folding kinetics. This new view describes protein folding as parallel, diffusion-like motions of a conformation ensemble on a highly dimensional energy surface, i.e., folding energy landscape, biased toward the native state. The folding energy landscape normally has a funnel-like shape that favors the native or folded conformation. Therefore, inhomogeneity in folding kinetics can be understood as the result of a rugged folding energy landscape where local traps, formed because of bad or unfavorable contacts, retard or frustrate the folding process. A downhill folding scenario, described recently by Wolynes and coworkers (18), can also lead to nonexponential kinetics in the search for native-like structures.

The energy landscapes of short helical peptides are expected to be much simpler than those of proteins and, therefore, have attracted the attention of both theoretical studies and computer simulations (19, 20). For example, in an MD simulation using an all-atom peptide model in explicit solvent, Hummer et al. (15, 21) have shown that the helix formation kinetics of an Ala pentapeptide can be described quantitatively by a diffusive search within the coil state with barrierless transitions into the helical state. Further, they pointed out that such a diffusive folding model should be testable by T-jump-coupled experiments. For example, a conformational diffusion search should lead to nonexponential kinetics in T-jump-induced conformation relaxations, because coil conformations closer to the helical state form helices faster than those distant from the helical state. Furthermore, the observed relaxation in T-jump experiments should also depend on the width of the T-jump, because conformation diffusion should depend on both the effective diffusion constant and the initial conformation distribution, which are determined by the final and initial temperatures, respectively.

To test these hypotheses and gain further understanding of the mechanism of helix formation, we have studied in detail the helix-coil transition of a synthetic Ala-based helical peptide and its isotope-labeled derivatives by using infrared spectroscopy and laser-induced T-jump technique. The T-jump method provides a means to quickly (within the duration of the T-jump pulse) perturb the temperature of the system and, therefore, the equilibrium between the folded and unfolded states. The relaxation to the new equilibrium position corresponding to the elevated temperature, which are probed in this study by monitoring the amide I′ absorbance of the peptide backbone, provides information for both folding and unfolding. The amide I′ band of polypeptides is due mainly to the amide C⩵O stretch vibration. Its sensitivity to conformation and conformational change is well documented (22–26). Although the protein amide I′ band has been used extensively for conformation analysis, it is often difficult to differentiate signals arising from different residues because the transitions are broadened from both inhomogeneous and homogeneous mechanisms. In this study, we followed the strategy of Decatur et al. (27), who prepared labeled peptides that contain a block of amide 13C⩵Os to obtain site-specific structural information through the shifted amide I′ absorbance of the 13C-labeled carbonyls (Fig. 1). It was found that the amide I′ band of the labeled residues is sensitive to their positions. We demonstrated that T-jump-induced relaxation to new equilibrium positions exhibits nonexponential kinetics, in agreement with our early studies (28). A rather surprising finding, however, is that the relaxation kinetics depend on both the initial and final temperatures. Together, these results indicate that helix formation follows a diffusion search model, as suggested by theoretical studies and MD simulations (15, 18, 21).

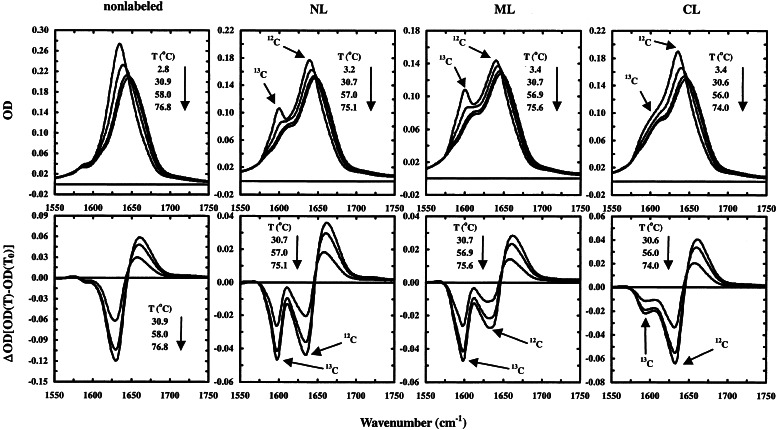

Figure 1.

Temperature-dependent equilibrium (Upper) and difference (Lower) infrared spectra of the labeled and nonlabeled peptides, as indicated in the plot. Difference spectra were generated by subtracting the spectrum collected at the lowest temperature from the spectra collected at higher temperatures. The bands at ≈1,600 cm−1 and ≈1,636 cm−1 are assigned to the amide I′ absorbance of the 13C-labeled and nonlabeled residues, respectively.

Materials and Methods

The α-helical peptides—Ac-YGSPEA3KA4KA4r-CONH2 (nonlabeled peptide), Ac-YGSPEA3KAAAAKA4r-CONH2 (ML peptide), Ac-YGSPEAAAKA4KA4r-CONH2 (NL peptide), and Ac-YGSPEA3KA4KAAAAr-CONH2 (CL peptide), where underlined residues are 13C-labeled and r represents d-Arg—were synthesized based on standard Fmoc-protocol employing Pal resin. All samples were purified to homogeneity and characterized by electrospray-ionization mass spectroscopy. For samples used in the infrared experiments, the residual trifluoroacetic acid from peptide synthesis, which has an infrared absorbance at 1,672 cm−1 that overlaps with the peptide amide I′ band, was removed by lyophilization against 0.1 M DCl solution. For both equilibrium and time-resolved infrared experiments, the samples were prepared by dissolving the lyophilized peptides directly in D2O; the final concentration was 2–4 mM.

Temperature-dependent Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectra of the peptides were collected on a Nicolet Magna-IR 860 spectrometer using 1 cm−1 resolution. A CaF2 sample cell that was divided into two compartments with a Teflon spacer was used to allow the separate measurements of the sample and reference (D2O) under identical conditions. The optical path length of the sample cell was determined to be 52 μm by its interference fringe obtained from the transmittance signal of the empty cell. Temperature control with ±0.2°C precision was obtained by a combination of a water bath (Haake K30) and a thermostated copper block. To correct for slow instrument drift, a programmable translation stage was used to move both the sample and reference side of the sample cell in and out of the infrared beam alternately, and each time a spectrum corresponding to an average of eight scans was collected. The final result was usually an average of 32 such spectra, both for the sample and the reference.

The T-jump infrared apparatus has been described in detail (29). A few modifications and improvements have been made to achieve better time resolution and signal-to-noise ratio. Specifically, the preamplifier of the mercury-cadmium-telluride detector was modified to achieve an effective rise time of 7–10 ns. To reduce shot-to-shot noise, the 1.9 μm T-jump pulse (3 ns and 10 Hz) was generated by means of Raman shifting the fundamental output of an Nd-YAG laser (Infinity, Coherent Radiation, Palo Alto, CA) in a Raman cell that was pressurized with a mixture of H2 and Ar to 750 psi. The presence of an inertial gas, such as Ar, greatly reduces the thermal effects and therefore stabilizes the 1.9 μm output. A stable pump source is rather critical to T-jump-coupled measurements because the observed kinetics are usually temperature dependent. To ensure a uniform T-jump distribution within the laser interaction volume, a thinner optical path length of 52 μm was used. Furthermore, to provide information for both background subtraction and T-jump amplitude calibration in the time-resolved measurements, a sample cell with dual compartments, similar to that used in the static FTIR measurements, was used to measure the T-jump-induced signals of both the sample and reference under the same conditions. Calibration of the T-jump amplitude was done by using the T-jump-induced absorbance change of the buffer (D2O) at the probing frequency ν, ΔA(ΔT, ν), and the following equation: ΔA(ΔT, ν) = a(ν)·ΔT + b(ν)·ΔT2, where ΔT = Tf − Ti is the T-jump amplitude; Tf and Ti correspond to the final and initial temperatures, respectively; and a(ν) and b(ν) are constants that are determined by the FTIR spectra of D2O measured at different temperatures.

Results

The isotopically labeled and nonlabeled peptides were synthesized based on the poly(A) helical sequence of Marqusee and Baldwin (30). Luo and Baldwin (31) showed that solvation of the exposed amide polar groups through hydrogen bonding with surrounding water molecules stabilizes helices by an enthalpic factor. Thus, alanine's strong helix-forming propensity can be understood by the facts that Ala is the only residue that does not suffer a loss of side chain conformation entropy upon helix formation, and also that its side chain does not interrupt the favorable interaction between water molecules and the polar groups in the helix backbone (32). The C-capping residue, d-Arg (r), was chosen because it is the most favorable C-cap reported in the literature (33). As a helix-stabilizing N-terminal sequence, we chose Ser-Pro-Glu, which is the tripeptide that occurs most frequently at the N terminus of helices in the WHATIF database of 1,705 helices. In these structures, the N-terminal Ser forms an N-capping interaction, and the Pro helps to initiate the helix. The Glu side chain adopts a variety of different conformations, suggesting that it might stabilize the helix by electrostatic interactions that are not particularly sensitive to the geometry of the structure. A possible helix-stabilizing role of Lys residues has been discussed recently by Scheraga and coworkers (34, 35).

The FTIR spectra of the labeled and nonlabeled peptides in the amide I′ region (Fig. 1) were collected roughly every 7°C, from ≈3°C to ≈76°C. It was found that all these spectra were fully reversible upon cooling, and no aggregation was detected even to the highest temperature, monitored by the distinct spectral features at 1,624 cm−1 and 1,675 cm−1 associated with aggregates. At low temperature, the nonlabeled peptide exhibits an amide I′ band at ≈1,636 cm−1, which is typical for solvated helices, whereas its labeled derivatives show two major bands at ≈1,600 cm−1 and ≈1,640 cm−1, respectively. The 1,600 cm−1 band is therefore assigned to the amide I′ absorbance of the 13C-labeled residues. An isotope shift of 36 cm−1 is very close to the anticipated frequency shift for an isolated C⩵O oscillator and also the observed value of 37 cm−1 for a carbonyl in model peptides (36). The FTIR difference spectra (Fig. 1) show that the amide I′ band loses intensity as temperature increases, and there is a concurrent formation of a new spectral feature at higher wavenumbers. The negative feature, centered at ≈1,598 cm−1, is due to the loss of helical structures reported by the 13C-labeled residues, whereas the ≈1,632 cm−1 feature is due to the melting of nonlabeled helical residues. Compared with that of the nonlabeled peptide, the ≈1,632 cm−1 negative component of the labeled peptides is diminished, especially in the case of NL and ML peptides, presumably because of the positive signals arising from the labeled residues that adopt disordered conformations. Assuming the same isotope shift of 36 cm−1 for those carbonyls adopting disordered conformations, their labeled derivatives would have an amide I′ band peaked at ≈1,634 cm−1, which overlaps with the helical absorbance reported by the nonlabeled residues.

The intensity of the 1,600 cm−1 component of the CL peptide is much smaller than those of the NL and ML peptides, in agreement with the results of Decatur and coworkers (27, 37), who attributed this decrease in intensity to end fraying. Calculations based on classic helix-coil transition theory (2, 3) and the zipper model of Eaton and coworkers (12) also show that the helical population at the C terminus is less than that of the middle or N terminus (data not shown). Nevertheless, a recent study suggested that the amide I′ bands of the solvent-exposed and buried amide groups in a protein may significantly differ. Manas et al. (38) demonstrated by using isotope editing that the amide I′ infrared band of the α-helical coiled-coil GCN4-P1 contains two major components at ≈1,625 cm−1 and 1,650 cm−1. The 1,625 cm−1 component exhibited stronger temperature dependence and was attributed to the solvent-exposed amide carbonyls. The observed difference in the amide I′ infrared spectra of the CL peptide also may be caused by the block of alanines whose amide carbonyls are fully exposed to solvent molecules.

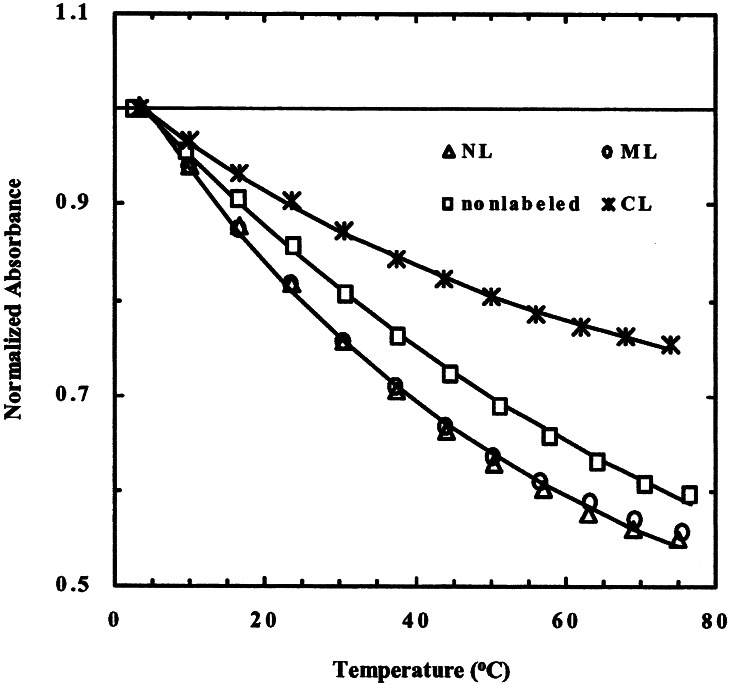

Both theoretical models and experimental results have suggested that short helical peptides contain helices of various lengths (9, 12), and an exact two-state description of helix-coil equilibrium is inadequate. The thermal unfolding curves measured by infrared of the labeled and nonlabeled peptides indeed show different behaviors (Fig. 2), indicating deviation from a two-state transition. It is clear that the block of alanines at the N terminus sample the same environment as that of the alanines at the middle of the peptide, indicated by the identical thermal melting transitions of these two labeled peptides. This result suggests that a helix containing the least number of residues in the bracket, Ac-YGSPE[A3KA4]KA4r-CONH2, is probably the dominating helical species. Kinetic measurements also show that these two blocks of alanines behave similarly.

Figure 2.

Thermal melting of the α-helical peptide obtained by monitoring the amide I′ bands of its labeled and nonlabeled derivatives, as indicated in the plot. For the labeled peptides, the probing frequency is 1,600 cm−1. For the nonlabeled peptide, the probing frequency is 1,636 cm−1. The data were normalized at the lowest temperature for each peptide to show the similarity and difference among the N terminus, C terminus, and the middle of the peptide. The smooth lines are to guide the eyes.

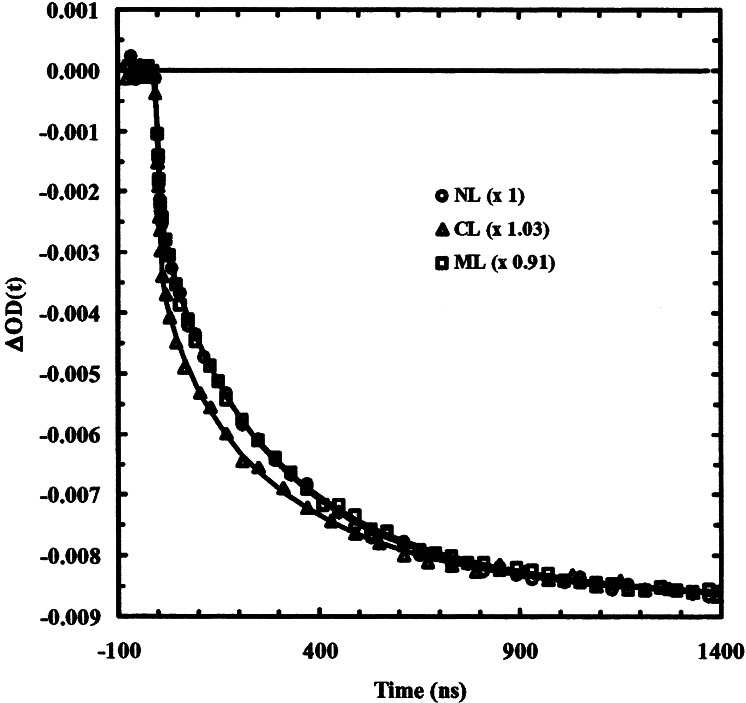

Specifically, isotope labeling residues at selected positions provide an effective means to probe site-specific conformational changes induced by the T-jump pulse. The relaxation kinetics of the three labeled peptides after a T-jump of ≈10°C, from 5 to 15°C, probed at 1,600 cm−1, show small but noticeable difference between that of the CL peptide and that of NL or ML peptide (Fig. 3). On the other hand, the relaxation kinetics of NL and ML peptides are identical within experimental noise, indicating that the 13C-labeled residues in these peptides probe the same transition, in agreement with the static FTIR measurements. Furthermore, these data were nicely modeled by a stretched exponential function§ and an instantaneous component that is not resolved because of the limited response time (7–10 ns) of the infrared detection system. Specifically, the function used to fit the data is ΔOD(t) = A·[1 − B·exp(−t/τ)β], where A is the full amplitude and (1 − B) is the percentage of the instantaneous component, and 0 < β < 1 measures the extent of deviations from single exponential kinetics. The parameters obtained from the best fits are listed in Table 1. It is evident from these results that the relaxation kinetics of the C terminus, after a T-jump, are faster and more stretched than that of the middle or N terminus of the peptide. Another visible difference is that the percentage of the instantaneous component for the CL peptide is larger than that of both the NL and ML peptides. The nature of this instantaneous component is not fully understood. Two mechanisms may contribute to this fast phase: an instantaneous spectral shift, or a conformational change on subnanosecond time scales as suggested by MD simulations (21). With a fluorescence probe attached at the N terminus of a helical peptide, Eaton and Hofrichter and their coworkers (12) have observed a very fast relaxation, which was attributed to the addition/removal of an additional hydrogen bond to an existing helix. It is likely that at least part of the observed fast phase is due to a similar process. The overall faster relaxation of the helical content near the C terminus, as revealed by the CL peptide, indicates that the unwinding of the helix probably occurs through the breaking of hydrogen bonds at the C terminus, as suggested by other studies (21, 32).

Figure 3.

Relaxation kinetics measured at 1,600 cm−1 for the three labeled peptides. Note that the signals have been scaled to the same amplitude. The T-jump was 10 ± 1°C, from 5 to 15°C. The smooth lines are fits to the following function, ΔOD(t) = A·[1 − B·exp(−t/τ)β], convolved with the instrument response function that was determined by fitting the rise time of the D2O signal. The fitting parameters are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Best fit parameters

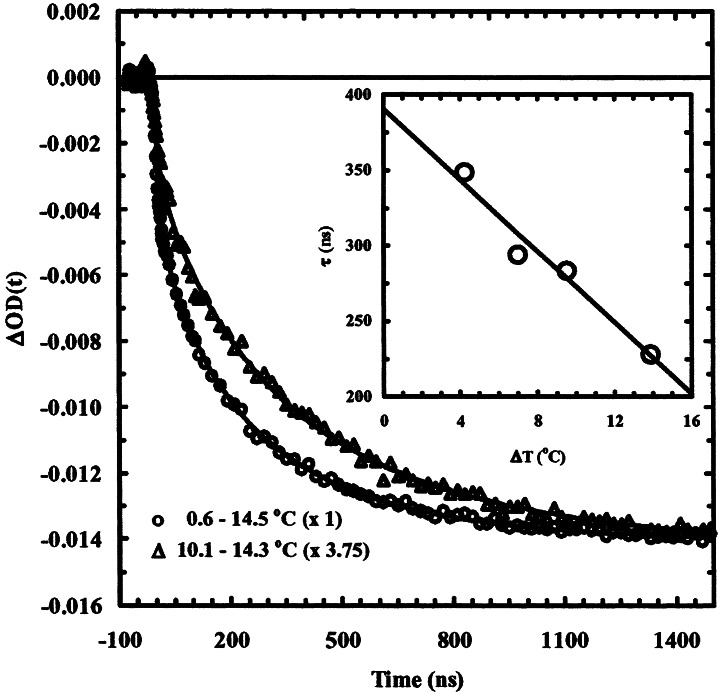

A rather surprising result, however, is that the T-jump-induced relaxation kinetics are T-jump width dependent; i.e., the relaxation is sensitive to both initial and final temperatures (Fig. 4). In an earlier work (29), we have shown that the helix-coil transition of a similar helical peptide exhibits linear temperature (the final temperature) dependence with an apparent activation energy of ≈15.5 kcal/mol. Although T-jump width-dependent relaxation kinetics have been observed for proteins (39, 40), it was not anticipated that peptides containing only secondary structures, such as the α-helix, also can exhibit this kind of behavior. Fig. 4 shows relaxation kinetics of the ML peptide, probed at 1,600 cm−1 and for two different T-jumps, i.e., from different initial temperatures, ≈0.5 and ≈10°C, respectively, to the same final temperature, ≈14.5°C. It is apparent that the T-jump-induced relaxation depends on the initial temperature with a relation that larger T-jump gives rise to faster overall relaxation rate. Similarly, these relaxations can be modeled by a stretched exponential and an instantaneous component. The results corresponding to four different initial temperatures are summarized in Table 1. It is interesting to notice that the time constant of the stretched exponential seems to have a linear dependence on T-jump amplitude (ΔT) within the range of temperature change used in this study. When ΔT is extrapolated to zero, a relaxation time of ≈390 ns is found for the final temperature of 14.5°C, which should correspond to the exchange time obtained from 13C NMR transverse relaxation experiments (16) that are done at a temperature corresponding to the same final temperature in the T-jump measurements.

Figure 4.

T-jump-induced relaxations of the ML peptide probed at 1,600 cm−1. The T-jump is from different initial temperatures to the same final temperature, as indicated in the plot. The smooth lines are fits to a stretched exponential function, as described in the legend of Fig. 3. The best fitting parameters are given in Table 1. Note that the signals have been scaled to reflect the difference between relaxations corresponding to different T-jump amplitudes. (Inset) T-jump amplitude-dependent relaxation time constants. The solid line is the linear regression to the data points.

Discussion

It is well known that stretched exponential kinetics (41) occur frequently in many condensed matter systems (42) as well as in proteins (43). A number of mechanisms have been found to be responsible for giving rise to stretched decay or relaxation. For example, diffusion with correlated traps has been suggested to yield stretched exponential kinetics in a domain of parameters that describe the trap clustering (44). The existence of a broad distribution of relaxation lifetimes because of inhomogeneity also can lead to stretched exponential kinetics. Another possibility is that the observed stretched exponential kinetics are the result of modulation of the rates of an underlying exponential process. Recently, stretched or “strange” kinetics of protein folding have been observed. Dobson and coworkers (45) have reported that the refolding kinetics of equine lysozyme can be described best by stretched exponentials. Gruebele and coworkers (40) also observed strange kinetics in the refolding of the cold denatured phosphoglycerate kinase. However, it was at first unanticipated that a short helical peptide, such as the one used in the current study, could follow such a complex relaxation, because single exponential relaxation kinetics have been reported by several research groups (10–13) on helical peptides of similar sequence and length. Nonetheless, the observed stretched or nonexponential relaxation kinetics are in accord with a number of theoretical studies (15, 46) and also a recent T-jump experiment done by Gruebele and coworkers (47) on nonbiological helices.

Deviation from single exponential relaxation kinetics indicates that a simple and rigorous two-state model cannot account for the nature of the helix-coil transition. Several reasons could lead to deviations from two-state or single exponential kinetics. One possibility is due to folding intermediates or multiple folding pathways. For example, in a recent all-atom computer simulation, Pande and coworkers (46) reported that a nonbiological helix, a 12-mer polyphenylacetylene, folds via an on-pathway intermediate and exhibits nonexponential folding kinetics. 310-helix also has been suggested previously as a possible intermediate in the folding of α-helix (48). By using a self-guided MD method, Wu and Wang (32) found that frequent transitions occur during their 10-ns simulation between 310-helix and α-helix. Further, they demonstrated that turns also may play an important role for the helix nucleation. It is unquestionable that a kinetic model involving either on- or off-pathway intermediates may be able to explain the observed nonexponentiality associated with the helix-coil transition kinetics; however, it hardly can interpret the fact that the relaxation kinetics also depend on the initial temperature.

An alternative explanation can be derived based on the concept of protein folding energy landscape, which describes folding as a diffusion-like process on a highly dimensional energy surface biased toward the native state. For such a diffusive motion, the mean folding time is determined by both the overall shape and the ruggedness of the energy landscape. A rugged energy landscape can affect the folding rate through an effective diffusion coefficient. Byngelson and Wolynes (49, 50) first introduced the idea of using diffusive coordinates along with energy landscape to interpret folding on a single funnel. Wolynes and coworkers (51, 52) further applied this approach to segment of polypeptide, such as the α-helix. They concluded that the folding of short peptides can be described as a downhill diffusion in conformation space without significant free energy barriers to the native state.

Although the helix formation involves greatly simplified searching through conformational space toward the native structure, this process is still too far from trivial to be simulated for peptides having significant helical populations in aqueous solution (like the one used in this study) using full atomic representations for both the peptide and water molecules. In an effort to catch the helix nucleation kinetics, Hummer et al. (21) recently performed MD simulations employing all-atom models and explicit solvent on the simplest peptide that can form 1.5 turns of α-helix: Ac-Ala5-NHMe (A5 peptide). A kinetic analysis shows that helix nucleation occurs rapidly on a time scale of 0.1 ns for this all-Ala pentapeptide. Based on extensive MD simulation and principal-component analysis, these authors further showed that the coil-to-helix transition of A5 peptide can be described quantitatively by a diffusive search within the coil state with barrierless transitions into the helical conformation (15), whereas helix-to-coil transitions occur predominantly through the breaking of hydrogen bonds at the helix ends, particularly at the C terminus.

A diffusive search model of helix formation leads to two conclusions that can be tested by T-jump coupled experiments. First, a conformation search within coil states to helix conformations would yield nonexponential kinetics, because coils that are close to the helical state will relax to the helical state faster than those distant from the helical state. Indeed, Hummer et al. (15) observed an initial nonexponential relaxation within the first 50 to 100 picoseconds for the A5 peptide. Although this time scale is too fast to be resolved by our current experimental setup, we did observe an instantaneous phase in the T-jump-induced relaxation kinetics. Second, a diffusion-search model suggests that the helix formation depends on the initial distribution of the coil conformation. Such dependence should lead to T-jump width dependent relaxation kinetics in the T-jump experiments, as observed in this study.

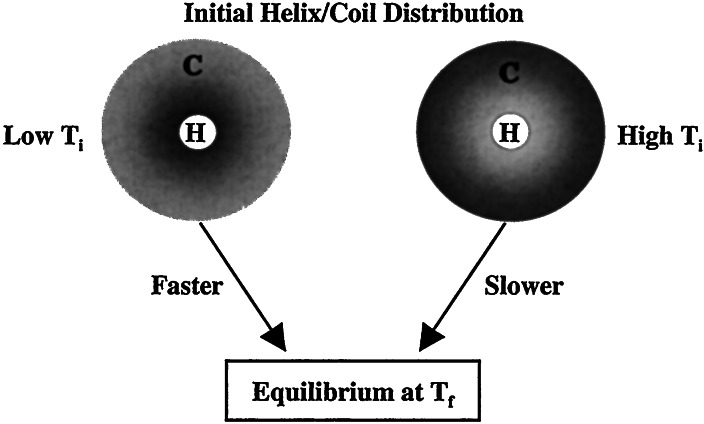

The result that needs to be explained in detail is why the mean relaxation time gets longer when ΔT approaches zero (Fig. 4). Although the helix-coil transition cannot be described rigorously as an equilibrium between two well defined states, the free energy profile of a helical peptide can nevertheless be depicted as two broad basins with a barrier separating the coil ensemble from the helix ensemble (53, 54). The two ensembles are in thermal equilibrium at any given temperature. Although a T-jump-induced relaxation always causes the coil population to increase (in the current study), the observed signal nevertheless contains contributions from both folding and unfolding, because the T-jump experiment is essentially a relaxation method. Most importantly, the final temperature of ≈14.5°C for the data presented in Fig. 4 is smaller than the apparent thermal melting temperature of ≈16°C (28). Therefore, at this temperature, the overall folding rate is comparable to the overall unfolding rate. Previously, a number of studies have shown that the helix-to-coil transition is mainly a thermally activated process with a significant enthalpic barrier, which leads to single exponential kinetics whose rate constant does not depend on initial temperature. Therefore, we attributed the observed nonexponentiality and the T-jump width dependence of the relaxation kinetics mainly to the folding of the coil conformation. When temperature is suddenly changed at zero time, both the coil and helix populations are projected onto a new free energy surface that is different from the one before the T-jump. However, the initial population distribution is essentially the same as that corresponding to the initial temperature (Fig. 5). Thus, when the initial temperature is significantly different from the final temperature, the coil states are on average closer to the helical states because of the lower conformational entropy, and the mean diffusion time for these molecules to be converted into the helical state therefore becomes faster. At a higher initial temperature, where most of the coil states are relatively distant from the helical state, it takes longer for them to diffuse to the helical region (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Schematic representation of the conformation distribution at zero time for low and high initial temperatures as well as T-jump-induced relaxations to the same new equilibrium position. The inner circle represents helical structures; the outer region corresponds to coil conformations. The darkness represents qualitatively the distribution of the coil states.

The current results also may be understood qualitatively within the framework of the kinetic zipper model developed by Eaton and coworkers (11, 12). This model suggests that it is not the nucleation process that limits the rate of helix formation. Instead, the rate of coil-to-helix transition is determined by the time required for the nucleated species to search for (or equilibrate with) the final helical conformation.

In summary, the T-jump-induced helix-coil transition kinetics of an Ala-based helical peptide, obtained by probing the amide I′ band of the peptide backbone, exhibit nonexponential behavior and are sensitive to both initial and final temperatures. These results provide strong evidence supporting the picture that the nucleation process is fast, on a nanosecond or subnanosecond time scale, and the helix formation process can be described by a diffusion search within the coil states. Further studies need to be carried out to address questions as to how peptide stability and length influence its folding dynamics and what is the nature of the fast component.

Acknowledgments

F.G. gratefully acknowledges financial support from Research Corporation, the University of Pennsylvania Research Foundation, National Science Foundation Grant CHE-0094077, and the Materials Research Science and Engineering Centers program of the National Science Foundation under award DMR00–79909.

Abbreviations

- T-jump

temperature jump

- MD

molecular dynamics

- FTIR

Fourier transform infrared

Footnotes

§ In an early publication (ref. 28), a multi-exponential function instead of stretched exponential function was used to fit the data. Also, in an early publication (ref. 29), nonexponential relaxation (for the slow phase) was not observed because the detection system used had a slower response time (20–30 ns).

References

- 1.Schellman J A. J Phys Chem. 1958;62:1485–1494. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zimm B H, Bragg J K. J Chem Phys. 1959;31:526–535. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lifson S, Roig A. J Chem Phys. 1961;34:1963–1974. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Poland D, Scheraga H A. Theory of Helix-Coil Transition in Biopolymers. New York: Academic; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brooks C L., III J Phys Chem. 1996;100:2546–2549. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kimov D K, Betancourt M R, Thirumalai D. Folding Des. 1998;3:481–496. doi: 10.1016/s1359-0278(98)00065-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Duan Y, Kollman P A. Science. 1998;282:740–744. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5389.740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buchete N-V, Straub J E. J Phys Chem B. 2001;105:6684–6697. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schimada J, Kussell E L, Shakhnovich E I. J Mol Biol. 2001;308:79–95. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Williams S, Causgrove T P, Gilmanshin R, Fang K S, Callender R H, Woodruff W H, Dyer R B. Biochemistry. 1996;35:691–697. doi: 10.1021/bi952217p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thompson P A, Munoz V, Jas G S, Henry E R, Eaton W A, Hofrichter J. J Phys Chem B. 2000;104:378–389. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thompson P A, Eaton W A, Hofrichter J. Biochemistry. 1997;36:9200–9210. doi: 10.1021/bi9704764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lednev I K, Karnoup A S, Sparrow M C, Asher S A. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:8074–8086. doi: 10.1021/ja003381p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ferrara P, Apostolakis J, Caflisch A. J Phys Chem B. 2000;104:5000–5010. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hummer G, Garcia A E, Grade S. Phys Rev Lett. 2000;85:2637–2640. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.85.2637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nesmelova I, Krushelnitsky A, Idiyatullin D, Blanco F, Ramirez-Alvarado M, Daragan V A, Serrano L, Mayo K H. Biochemistry. 2001;40:2844–2853. doi: 10.1021/bi001293b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clarke D T, Doig A J, Stapley B J, Jones G R. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:7232–7237. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.13.7232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bryngelson J D, Onuchic J N, Wolynes P G. Proteins Struct Funct Genet. 1995;21:167–195. doi: 10.1002/prot.340210302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Takano M, Takahashi T, Nagayama K. Phys Rev Lett. 1998;80:5691–5694. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saven J G, Wolynes P G. Physica D. 1997;107:330–337. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hummer G, Garcia A E, Grade S. Proteins Struct Funct Genet. 2001;42:77–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krimm S, Bandekar J. Adv Protein Chem. 1986;38:181–364. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3233(08)60528-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heimburg T, Schuenemann J, Weber K, Geisler N. Biochemistry. 1996;35:1375–1382. doi: 10.1021/bi9515883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gilmanshin R, Williams S, Callender R H, Woodruff W H, Dyer R B. Biochemistry. 1997;36:15006–15012. doi: 10.1021/bi970634r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Volk M, Kholodenko Y, Lu H S M, Gooding E A, DeGrado W F, Hochstrasser R M. J Phys Chem B. 1997;101:8607–8616. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fabian H, Schultz C, Naumann D, Landt O, Hahn U, Saenger W. J Mol Biol. 1993;232:967–981. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Decatur S M, Antonic J. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:11914–11915. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huang C-Y, Getahun Z, Wang T, DeGrado W F, Gai F. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:12111–12112. doi: 10.1021/ja016631q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huang C-Y, Klemke J W, Getahun Z, DeGrado W F, Gai F. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:9235–9238. doi: 10.1021/ja0158814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marqusee S, Baldwin R L. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;88:2854–2858. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.7.2854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Luo P, Baldwin R L. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;96:4930–4935. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.9.4930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wu X, Wang S. J Phys Chem B. 2001;105:2227–2235. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schneider J P, DeGrado W F. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:2764–2767. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vila J A, Ripoll D R, Scheraga H A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:13075–13079. doi: 10.1073/pnas.240455797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vila J A, Ripoll D R, Scheraga H A. Biopolymers. 2001;58:235–246. doi: 10.1002/1097-0282(200103)58:3<235::AID-BIP1001>3.0.CO;2-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tadesse L, Nazarbaghi R, Walters L. J Am Chem Soc. 1991;113:7036–7037. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Silva R A G D, Kubelka J, Bour P, Decatur S M, Keiderling T A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:8318–8323. doi: 10.1073/pnas.140161997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Manas E S, Getahun Z, Wright W W, DeGrado W F, Vanderkooi J M. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:9883–9890. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Leeson D T, Gai F, Rodriguez H M, Gregoret L M, Dyer R B. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:2527–2532. doi: 10.1073/pnas.040580397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sabelko J, Ervin J, Gruebele M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:6031–6036. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.11.6031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hagen S J, Eaton W A. J Chem Phys. 1996;104:3395–3398. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Klafter J, Shlesinger M F. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:848–851. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.4.848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kumar A T N, Zhu L, Christian J F, Demidov A A, Champion P M. J Phys Chem B. 2001;105:7847–7856. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Makhnovskii Y A, Berezhnovskii A M, Sheu S-Y, Yang D-Y, Lin S H. J Chem Phys. 1999;111:711–720. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Morozova-Roche L A, Jones J A, Noppe W, Dobson C M. J Mol Biol. 1999;289:1055–1073. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Elmer S, Pande V S. J Phys Chem B. 2001;105:482–485. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yang W Y, Prince R B, Sabelko J, Moore J S, Gruebele M. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:3248–3249. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Miick S M, Martinez G V, Fiori W R, Todd A P, Millhauser G L. Nature (London) 1992;359:653–655. doi: 10.1038/359653a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bryngelson J D, Wolynes P G. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:7524–7528. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.21.7524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bryngelson J D, Wolynes P G. J Phys Chem. 1989;93:6902–6915. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Onuchic J N, Luthey-Schulten Z, Wolynes P G. Annu Rev Phys Chem. 1997;48:545–600. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physchem.48.1.545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hardin C, Luthey-Schulten Z, Wolynes P G. Proteins Struct Funct Genet. 1999;34:281–294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hiltpold A, Ferrara P, Gsponer J, Caflisch A. J Phys Chem B. 2000;104:10080–10086. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Levy Y, Jortner J, Becker O M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:2188–2193. doi: 10.1073/pnas.041611998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]