Abstract

Background

Disasters disrupt societies and exceed their capacities to cope, necessitating external support. Nurses play a critical role in disaster response, but disaster anxiety can negatively impact their willingness to work in such situations. Disaster response self-efficacy is positively impact nurse’s willingness to work in disasters. This study aimed to examine the mediating role of disaster response self-efficacy in the effect of disaster anxiety on the willingness to work in disasters among nurses.

Methods

A cross-sectional and descriptive study was conducted among 273 nurses from a university hospital in Türkiye using a random sampling method. Data were collected through validated scales, including the Disaster Response Self-Efficacy Scale, Disaster Anxiety Scale and a single-item measure for willingness to work in disasters. Analysis involved SPSS, AMOS, and PROCESS Model 4 to assess mediation effects.

Results

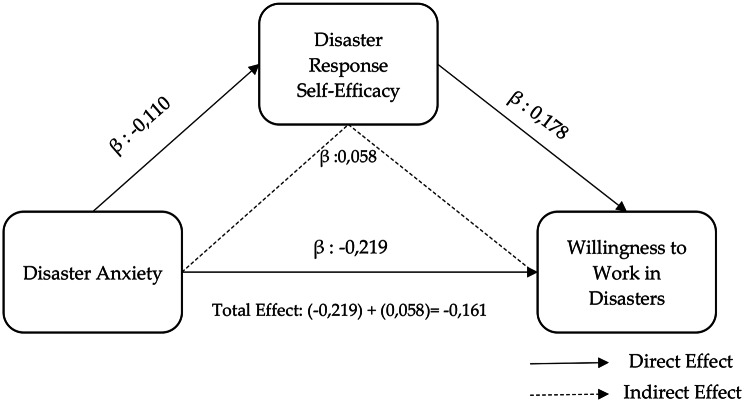

Disaster anxiety negatively influenced both disaster response self-efficacy (β = −0.110) and willingness to work during disasters (β = −0.219). However, disaster response self-efficacy was positively associated with willingness to work (β = 0.178), demonstrating a mediating effect. The total effect of disaster anxiety on willingness to work, mediated by disaster response self-efficacy, was − 0.161.

Conclusions

Disaster response self-efficacy partially mediates the negative impact of disaster anxiety on nurses’ willingness to work during disasters. While disaster response self-efficacy mitigates the adverse effects of disaster anxiety, it does not fully reverse them. National and institutional health and nursing policies should focus on reducing disaster anxiety and strengthening nurses’ disaster preparedness to ensure effective disaster relief and response.

Keywords: Disaster response self-efficacy, Disaster anxiety, Willingness to work, Nurses, Disaster management, Health policy, Nursing policy

Introduction

Disasters are defined as severe disruptions in the functioning of a society that exceeds its capacity to cope using its resources [1]. Worldwide disasters have increased significantly over the past decade compared to the previous sixty years [2]. Due to factors such as climate change, displacement, conflict, rapid and unplanned urbanization, technological hazards, and public health emergencies, the frequency, complexity, and severity of disasters will likely increase [1]. Such disasters result in physical, psychological, and social harm [3]. Disasters devastate individuals, communities, economies, and the environment, and these effects are more profoundly felt in developing countries [4].

Healthcare services play a key role in mitigating the impacts of disasters [5]. Nurses, as an integral part of healthcare services, provide the most appropriate care to individuals affected by disasters to minimize the hazards, risks, and life-threatening damage that arise at all stages of disaster management [6]. During disasters, nurses carry out initial interventions and evacuation procedures and prioritize healthcare needs through triage [7, 8]. In addition, nurses fulfill various duties and responsibilities, including assessing the current situation, ensuring communication and coordination with other institutions, controlling the spread of infectious diseases, and providing patient care, treatment, and rehabilitation [7]. Considering this positive contribution of nurses during disasters, identifying the factors that influence their willingness to participate in disaster response is of great importance for disaster management.

There are several studies on nurses’ willingness to work during disasters. These studies indicate that factors such as professional commitment, patriotism, belief systems, safety concerns, family responsibilities, protective equipment, health status, and transportation issues can positively or negatively influence nurses’ willingness to work in disasters [9–11]. However, empirical findings regarding the impact of disaster-related anxiety on nurses’ willingness to work in disasters are still limited. Since nurses are often on the front lines of disaster response, they are exposed to significant stress and anxiety during hazardous events or disasters [12–14]. It is also known that following disasters, nurses may experience high levels of anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder [15]. Therefore, understanding the impact of disaster anxiety on nurses’ willingness to participate in disaster situations is important.

Self-efficacy is another significant variable that may affect nurses’ willingness to work during disasters. Some studies have shown that self-efficacy determines the willingness to work during disasters [11, 16, 17]. Nurses with high self-efficacy are more willing to take on duties in uncertain and risky disaster conditions. The literature includes studies on disaster-related anxiety, willingness to work in disasters, and disaster response self-efficacy among nurses [5, 17, 18]. However, to our knowledge, the mediating role of self-efficacy in the relationship between disaster anxiety and willingness to work has not yet been investigated. The originality of this study lies in its examination of the mediating role of disaster response self-efficacy in the relationship between disaster-related anxiety and nurses’ willingness to work during disasters.

This study aims to evaluate the effect of nurses’ disaster-related anxiety on their willingness to work during disasters and examine the mediating role of disaster response self-efficacy in this relationship. The current research is structured based on the Protection Motivation Theory (PMT) to achieve this aim. As a health promotion model, PMT suggests that a certain level of risk-related knowledge can generate the motivation necessary for individuals to assess the severity of a risk, their vulnerability to it, and their ability to reduce it [19]. PMT has become a widely used theory to explain risk-reduction behaviors in the face of natural disasters. The theory consists of two components: threat appraisal (perceived vulnerability, perceived severity, and rewards) and coping appraisal (response efficacy, self-efficacy, and response costs), along with a fear component [20]. Moreover, PMT has been used in nursing research to explain various health behaviors [22–25].

Disaster anxiety represents nurses’ emotional response to disasters. This corresponds to the threat appraisal component of PMT. On the other hand, disaster response self-efficacy refers to individuals’ belief in their capacity to respond effectively during disasters and is directly related to PMT’s self-efficacy and response efficacy components. In this context, the study is based on the assumption that while high levels of disaster anxiety may reduce nurses’ willingness to work during disasters, this effect may be weakened in individuals with high disaster response self-efficacy.

To test this assumption, the following question is addressed

Q1– Does disaster response self-efficacy mediate between disaster anxiety and the willingness to work in disasters?

Methods

Design, setting and participants

This study is cross-sectional descriptive research conducted from October 9 to December 8, 2024. The population of the study consists of 942 nurses working at a university hospital in Türkiye’s Black Sea Region. The sample size was calculated to be 273 nurses, based on a 95% confidence interval and a 5% margin of error.

The sample size was calculated using the following formula [26].

N = Universe.

n = Number of samples.

p = Frequency of occurrence of the feature we are interested in within the universe (0.50 was taken).

q = Frequency of non-occurrence of the feature we are interested in within the universe (1-p).

Z = Standard value according to the confidence level (1.96 for 95% found from normal distribution tables).

t = Tolerable error (0.05 was taken)

|

|

|

A simple random sampling method was employed. Data were collected using face-to-face and online surveys from voluntary participants.

Instruments

General information

The first part of the questionnaire includes socioeconomic details, such as the participant’s age, gender, marital status, educational background, years of work experience, experience of losing a relative in a disaster, previous work experience in disasters, and whether they have received training related to disasters. This section consists of a total of eight questions.

Disaster response Self-Efficacy scale

Disaster Response Self-Efficacy Scale developed by Li et al. [27] and validated in Turkish by Koca et al. [28] was used in this study. The scale consists of 19 items across three sub-dimensions: on-site rescue competency, disaster psychological nursing competency, and disaster role quality and adaptation competency. Example items include “I can perform the initial psychological assessment of disaster victims” and “I can effectively communicate with disaster victims and their relatives, establishing a good nurse-patient relationship.” Each item is rated on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The original Cronbach’s alpha value was reported as 0.912, while the Turkish validity version showed 0.96; in this study, it was found to be 0.961.

Disaster anxiety scale

Initially developed by Lee [29] for coronavirus anxiety, this scale underwent validity and reliability studies by Evren et al. [30] and was further adapted by Güzel [18] as the Disaster Anxiety Scale. The scale consists of six items in a single dimension. Example items include “My hands tremble when I think about disasters” and “I lose my appetite when I think about disaster situations.” The scale is a six-point Likert type (0 = no anxiety, 1 = very little anxiety, 2 = some anxiety, 3 = moderate anxiety, 4 = quite a bit of anxiety, 5 = very high anxiety). As the average score increases, participants’ anxiety regarding disasters also increases. The original Cronbach’s alpha value is 0.968, while in this study, it was found to be 0.941.

Willingness to work in disasters

Participants were asked whether they would be willing to serve as nurses in any disaster. Responses were limited to “yes” or “no.”

Data collection

Data were collected between October and December 2024 through face-to-face and online methods. Both data collection methods were used together due to the nurses’ shift work, assignment to different units, workload, etc. Necessary permission for the study was obtained from the hospital management before data collection. Face-to-face data collection was carried out by the researchers by explaining the purpose of the study, obtaining informed consent from the participants, and answering their questions. The online survey link (Google Forms) was sent to the participants’ Whatsapp groups. The questionnaire was preceded by the informational part explaining the purpose of the study, indicating that participation was voluntary and anonymous. Participants who consented to participate in the study via online by clicking on the “I accept” button, and were given access to the survey. The survey took approximately 10–15 min to complete.

Data analysis

Data analysis was conducted using SPSS, AMOS, and HAYES software. AMOS and HAYES were used as add-ons for validity, reliability, and structural equation modeling. Within the scope of the research, the entire scale was used, not the sub-dimensions of the scales. Regression analysis using Model 4 was performed for the research. Five thousand bootstrap cycles were performed to calculate standardized total and indirect effects, standard errors, and bias-corrected 95% confidence intervals. Although mediation analyses are often performed within the linear regression framework, they also maintain validity when the dependent variable is binary. Hayes [31] states that in the PROCESS macro model, he developed for SPSS if the dependent variable consists of two categories, 0 and 1, the logistic regression model is automatically activated instead of linear regression. In this context, in the analyses conducted within the framework of PROCESS Model 4, the binary nature of the Y variable does not prevent mediation analysis; only the type of analysis changes. All analyses were conducted at a 95% confidence level with a 5% margin of error. The data were tested for normality using the Shapiro-Wilk test, and the p-value was greater than 0.05, indicating that the data conformed to a normal distribution. In order to ensure the validity of the scales, Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) analysis was first performed.

Table 1 presents the research findings regarding the EFA analysis. The total variance explained for the scales was 75.007%, and the Kaiser-Mayer-Olkin (KMO) value was 0.930. The Disaster Anxiety scale was collected in one dimension as in the original, and the factor loadings of the scale expressions varied between 0.821 and 0.910. However, the Disaster Response Self-Efficacy scale was distributed in three dimensions as in the original. The factor loadings of the scale expressions varied between 0.523 and 0.834. In this study, Cronbach’s alpha coefficient and composite reliability (CR) were used to test the reliability of the questionnaire. Both the alpha coefficient and composite reliability (CR) were greater than 0.70, indicating the scale’s good reliability. The validity of the questionnaire was tested using factor loadings and average variance extracted (AVE). All factor loadings were greater than 0.45, and the AVE was greater than 0.50, indicating the scale’s good validity.

Table 1.

EFA, CR and AVE values of the scales

| Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy. | 0,930 | |||

| Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity | Approx. Chi-Square | 6771,102 | ||

| df | 300 | |||

| p | 0 | |||

| Toplam açıklanan varyans | 75.007 | |||

| Disaster Anxiety | Disaster Response Self-Efficacy | |||

| DA1 | ,867 | |||

| DA2 | ,891 | |||

| DA3 | ,910 | |||

| DA4 | ,862 | |||

| DA5 | ,900 | |||

| DA6 | ,821 | |||

| DRSE1 | ,760 | |||

| DRSE2 | ,834 | |||

| DRSE3 | ,799 | |||

| DRSE4 | ,725 | |||

| DRSE5 | ,736 | |||

| DRSE6 | ,736 | |||

| DRSE7 | ,666 | |||

| DRSE8 | ,694 | |||

| DRSE9 | ,701 | |||

| DRSE10 | ,523 | |||

| DRSE11 | ,586 | |||

| DRSE12 | ,749 | |||

| DRSE13 | ,830 | |||

| DRSE14 | ,829 | |||

| DRSE15 | ,591 | |||

| DRSE16 | ,699 | |||

| DRSE17 | ,812 | |||

| DRSE18 | ,820 | |||

| DRSE19 | ,784 | |||

| Açıklanan Varyans | 27.307 | 18.930 | 14.443 | 14.326 |

| CR | 0.954 | 0.631 | ||

| AVE | 0.968 | 0.774 | ||

| Cronbach alfa | 0.941 | 0.961 | ||

After the EFA analysis, Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted for the DRSE scale, with results supporting the overall measurement quality: CMIN/DF (3.299), Goodness of Fit Index (GFI: 0.854), Normed Fit Index (NF: 0.911), Comparative Fit Index (CFI: 0.936), Adjusted Goodness of Fit Index (AGFI: 0.804), and Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA: 0.081). For the DA scale, CFA analysis was conducted, yielding the following results: CMIN/DF (4.954), GFI (0.920), NF (0.983), CFI (0.946), AGFI (0.872), and RMSEA (0.059). Finally, the fit index values for all scales were determined as CMIN/DF (2.546), GFI (0.858), NFI (0.906), CFI (0.940), AGFI (0.857), and RMSEA (0.075).

Common method variance test

Harmann one-way variance analysis was performed to eliminate common orientation biases. The analysis was performed one-way and without principal component factor rotation. According to the analysis results, the first factor explained 44.20% of the variance, consistent with the values recommended in the literature [32, 33].

Results

Participant demographics

79.1% of the participants were female, 46.6% were in the 30–45 age group, 67% were married, and 54% indicated that they had been actively practicing nursing for over ten years. Among the participants, 42.9% (n = 117) reported having experienced a disaster (such as an earthquake or flood), 6.2% (n = 17) stated that they had lost a relative in a disaster, 18.3% (n = 50) indicated that they had previously worked in a disaster, and 62.6% (n = 171) reported having received training in disaster management or intervention.

Descriptive statistics and correlation analysis

The average score of the DRSE was interpreted as moderately high, whereas the DA had a lower average. The WWD variable consists solely of “yes” and “no” responses and during the coding process, the “no” option was coded as 2. Therefore, the average response for this item can be considered moderately high. Correlation findings indicated a negative relationship between DRSE and DAS, as well as between WWD and DAS, while a positive relationship was observed between DRSE and WWD (Table 2).

Table 2.

Correlation matrix between disaster anxiety, disaster response self-efficacy, and willingness to work during disasters

| Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DA (1) | 2,6374 | 1,21837 | 1 | ||

| DRSE (2) | 3,7602 | ,74,787 | -,179** | 1 | |

| WWD (3) | 1,6374 | ,48,164 | -,155* | ,206** | 1 |

DA: Disaster Anxiety, DRSE: Disaster Response Self-Efficacy, WWD: Willingness to Work in Disasters, SD: Standart Deviation

* Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level

** Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level

Test of mediation effect

The results of the mediation effect are presented in Table 3, utilizing SPSS PROCESS Model 4. The regression weights among DA, DRSE and WWD were calculated. According to the model, DA (β = -0.219) negatively influences the WWD. Additionally, DA also has a negative impact on DRSE (β = -0.110). Conversely, DRSE positively affects the WWD (β = 0.178). Finally, it can be inferred that DRSE plays a mediating role in the effect of DA on WWD. Thus, the total effect was determined to be 0.161 (Fig. 1).

Table 3.

Mediating role of disaster response Self-Efficacy in the relationship between DA and WWR

| Total | B | SE | t | p | LLCI | ULCI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DA and WWR | Total | 0,161 | 0,721 | 4,31 | 0.040 | -0,181 | -0,374 |

| Direct | − 0,219 | 0,108 | -2,040 | 0,031 | -0,430 | -0,009 | |

| Indirect | 0,058 | 0,036 | -0,145 | -0,008 |

DA: Disaster Anxiety, DRSE: Disaster Response Self-Efficacy, WWD: Willingness to Work in Disasters, SE = standard error; LLCI = lower limit confidence interval; ULCI = upper limit confidence interval

Fig. 1.

The mediating role of DRSE on the effect of DA on WWD

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, it was conducted in a single university hospital limiting the findings’ generalizability to other healthcare institutions. The results reflect the specific context of the hospital studied and may not account for variability in different healthcare settings. Further research is needed to determine the generalizability of these results. Second, the data collection relied on self-reported measures, which are inherently subject to response bias and may not fully capture participants’ actual behaviors or attitudes. In the data collection process, online and face-to-face methods were used to reach the targeted sample size due to the nurses working in shifts and different units. In addition to the advantages of both methods, online data collection has disadvantages such as distraction of participants, technical problems, limited control of the environment, etc., and social desirability and the possibility of participants expressing themselves differently in face-to-face data collection. Finally, the study design was cross-sectional, which limits the ability to establish causality between DA, DRSE, and WWD. Longitudinal studies or experimental designs could provide deeper insights into these relationships.

Discussion

During the disaster response process, nurses are exposed to traumatic events, work under stress, and may experience various psychological issues. Common problems observed during this process include depression, fear, burnout, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder [34]. These psychological challenges faced by nurses can be factors contributing to DA. In our study, the finding that nurses have low levels of DA suggests that this professional group may possess a high level of psychological resilience towards disasters. Given that Türkiye is a country frequently affected by disasters, it may be inferred that nurses have become accustomed to such events. However, findings by Huang et al. [13] reported high levels of DA among nurses. This situation indicates that the characteristics of the working environments of nurses in different regions, their disaster experiences, or personal factors may influence the differences in their DA levels.

WWD among nurses is critically important for the sustainability of quality healthcare services. In our study, WWD among nurses was found to be at a moderate to high level. This finding partially aligns with studies by Arbon et al. [35] and Hendrickx et al. [36] which reported high levels of WWD. The altruistic nature of the nursing profession, which is based on helping others, may be a significant factor in explaining the high levels of WWD among nurses.

Another finding of this research pertains to the level of DRSE. In our study, it was determined that the DRSE levels of nurses are at a moderate to high level. While Hasan et al. [8] found that nurses reported high levels of DRSE, Labrague et al. [37] identified a moderate level of DRSE. Overall, it appears that nurses’ DRSE levels are at or above moderate levels. Variations in DRSE levels may stem from factors such as the education nurses receive and their experiences during disaster processes. Furthermore, it is believed that psychological factors also influence DRSE levels. The negative impact of DA on DRSE, as highlighted in our research findings, supports this assertion. DA not only adversely affects DRSE but also negatively influences nurses’ willingness to work in disasters. Supporting our finding, a study indicated that healthcare professionals experiencing fear and anxiety during disasters reported a decreased WWD [38]. Consequently, this leads to disruptions in the provision of quality healthcare services in disaster-affected areas [39].

Another finding of this research is that DRSE positively influences the WWD. Al-Hunaishi et al. [17] stated that self-efficacy is an important factor in predicting WWD among nurses and doctors, noting that as DRSE levels increase, WWD also rises. Similarly, Choi and Lee [11] indicated that nurses with higher levels of DRSE are more WWD compared to those with lower levels. When the findings of this study are evaluated within the framework of protective motivation theory, it shows that nurses’ disaster anxiety can affect their desire to work in disasters. According to the Protective Motivation Theory, when individuals encounter a threat, they evaluate the seriousness and consequences of the threat and develop attitudes and behaviors [40]. The anxiety experienced by nurses in high-risk situations such as disasters emerges from this perception of threat. In addition, the second component of Protective Motivation Theory, the coping style, includes the individual’s belief that he/she can effectively intervene against the danger he/she encounters. In the study, it was observed that nurses with high levels of disaster intervention self-efficacy were more willing to take on disaster tasks. It is seen that disaster anxiety can reduce the desire to work in disasters, but the level of self-efficacy can play a protective role in reducing this effect. As a result, the findings presented are consistent with Rogers‘ [41] protective motivation theory approach.

The final and significant finding of the research is that DRSE mitigates the negative impact of disaster anxiety DA on the WWD. In the literature review, no studies were found examining the direct mediating role of DRSE in nurses. However, studies were found in which nurses were examined together with various factors, including DRSE and employee well-being [42] disaster preparedness perception [43] and emotional intelligence [44].

To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to examine the mediating role of DRSE in the relationship between DA and the WWD. The results of our research indicate that increasing nurses’ levels of DRSE not only enhances their WWD but also reduces the negative effects of DA on WWD. This finding clearly highlights the critical importance of DRSE among nurses. In this respect, our study aims to contribute to the existing literature by shedding light on this gap.

Conclusion

This study aimed to investigate the mediating role of DRSE in the relationship between DA and WWD among nurses. It was determined that DA negatively affects the WWD among nurses, with DRSE acting as a positive mediator in this relationship. Specifically, DA reduces nurses’ WWD, while DRSE plays a beneficial mediating role. Thus, it can be stated that DRSE is a critical factor in enhancing nurses’ WWD despite their DA. However, even though DA adversely affects the WWD, the DRSE process mitigates this negative impact. Based on the Protection Motivation Theory, the findings obtained can be evaluated as a situation regarding the individual response of nurses to disasters. In contrast, disaster anxiety in nurses can be considered as a situation regarding the individual response of nurses to disasters since disaster response self-efficacy reflects their evaluations regarding their capacity to intervene effectively in the event of a disaster and is individually related to self-efficacy and response effectiveness components, it may serve as a partial explanatory factor in understanding nurses’ willingness to engage in disaster response. Nonetheless, the WWD does not shift from negative to positive; although DRSE plays an important role in this regard, many unknown factors also influence nurses’ WWD.

Implications for practice

The results of this study suggest that reducing the effect of disaster anxiety on the willingness to work in disasters, increasing nurses’ disaster intervention self-efficacy, empowering nurses, improving their competencies for disaster interventions, and increasing their self-efficacy may contribute to increasing their willingness to work in disasters. Therefore, developing policies and strategies at both national and institutional levels aimed at reducing DA and enhancing nurses’ DRSE could be beneficial in increasing their WWD. While the types and impacts of disasters vary from country to country and region to region, nurses, as indispensable human resources in any disaster management and healthcare delivery, play a critical role in protecting community health. It is recommended that the levels of DA among nurses be regularly measured and monitored and that psychosocial support and empowerment services aimed at reducing DA be planned. Furthermore, future research should address the inclusion of diverse healthcare settings, incorporate mixed methods to identify factors that influence nurses’ willingness to work in disasters, and employ robust longitudinal designs to understand better the dynamics of disaster response among nurses and healthcare professionals, as well as different theories to identify other conditions that may be caused by disaster anxiety.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the nurses who participated in the study.

Author contributions

“All authors designed the study. P.B.G. and G.Z.A. conducted data collection. M.A. D.G. and P.B.G. performed data analysis. M.A. D.G. and G.Z.A. carried out study supervision. P.B.G. G.Z.A. and N.G. wrote the manuscript. N.G. and M.A. made critical revisions for important intellectual content.”

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from public/private organizations/institutes.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Necessary permissions were obtained from the developers of all scales used in the study. Additionally, permission was granted by the relevant hospital directorate. Ethics committee approval was obtained from the relevant university for the study. The Süleyman Demirel University Ethics Committee ethically assessed and authorized the research design and methodology (Verification Code: E9A61AE, No. E.849500). Throughout the research process, compliance with the Helsinki Declaration was maintained, and survey responses were collected in sealed envelopes to ensure confidentiality. Finally, informed consent forms were obtained from all participants.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.IFRC. What is disaster?. 2023a. https://www.ifrc.org/our-work/disasters-climate-and-crises/what-disaster Accessed 21 December 2024.

- 2.IFRC, World Disasters R. 2022. 2023b. https://www.ifrc.org/document/world-disasters-report-2022 Accessed 21 December 2024.

- 3.Kim SH. A psychometric validation of the Korean version of disaster response Self-Efficacy scale for nursing students. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20(4):1–13. 10.3390/ijerph20042804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America. Handbook for estimating the socio-economic and environmental effects of disasters. United Nations, Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), & International Bank for Reconstruction and Development. 2003. https://repositorio.cepal.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/e390b193-db7e-4b5b-a929-9550b7538aac/content Accessed 25 June 2025.

- 5.Yılmaz D, Buran G. Disaster response self-efficacy of students in the nursing department: a cross-sectional study. Makara J Health Res. 2024;28(1):60–5. 10.7454/msk.v28i1.1603. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thobaity AA, Plummer V, Williams B. What are the most common domains of the core competencies of disaster nursing? A scoping review. Int Emerg Nurs. 2017;31:64–71. 10.1016/j.ienj.2016.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wall BM. Disaster nursing and community responses: a historical perspective. Nurs Hist Rev. 2015;23:11–27. 10.1891/1062-8061.23.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hasan MK, Srijan MH, Mahatasim M, Anjum A, Abir AI, Masud MB, Tahsin S, Akram S, Shuvo MSR, Akter J, Hossain MS, Uddin R, Islam MS. Factors influencing disaster response self-efficacy among registered nurses in Bangladesh. Progress Disaster Sci. 2024;23:1–9. 10.1016/j.pdisas.2024.100341. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ke Q, Chan SWC, Kong Y, Fu J, Li W, Shen Q, Zhu J. Frontline nurses’ willingness to work during the COVID-19 pandemic: A mixed‐methods study. J Adv Nurs. 2021;77(9):3880–93. 10.1111/jan.14989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chien YA, Lee YH, Chang YP, Lee DC, Chow CC. Exploring the relationships among training needs, willingness to participate and job satisfaction in disaster nursing: the mediating effect of achievement motivation. Nurse Educ Pract. 2022;61(103327):1–8. 10.1016/j.nepr.2022.103327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Choi HS, Lee JE. Hospital nurses’ willingness to respond in a disaster. JONA: J Nurs Adm. 2021;51(2):81–8. 10.1097/NNA.0000000000000974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim Y, Kim M. Factors affecting household disaster preparedness in South Korea. PLoS ONE. 2022;17(10):e0275540. 10.1371/journal.pone.0275540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang W, Li L, Zhuo Y, Zhang J. Analysis of resilience, coping style, anxiety, and depression among rescue nurses on EMTs during the disaster preparedness stage in sichuan, china: A descriptive cross-sectional survey. Disaster Med Pub Health Prep. 2023;17:e268. 10.1017/dmp.2022.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang Y, Liu Y, Yu M, Wang H, Peng C, Zhang P, … Changyan LI. Disaster preparedness among nurses in China: a cross-sectional study. Journal of Nursing Research, 2023;31(1), e255. doi: 10.1097/jnr.0000000000000537. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Schwartz RM, Sison C, Kerath SM, Murphy L, Breil T, Sikavi D, Taioli E. The impact of hurricane sandy on the mental health of new York area residents. Am J Disaster Med. 2015;10(4):339–46. 10.5055/ajdm.2015.0216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Öksüz MA, Avci D, Kaplan A. Relationship between disaster preparedness perception, self-efficacy, and psychological capital among Turkish nurses. Int Nurs Rev. 2025;72(1):e13097. 10.1111/inr.13097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Al-Hunaishi W, Hoe VC, Chinna K. Factors associated with healthcare workers willingness to participate in disasters: A cross-sectional study in sana’a. Yemen BMJ Open. 2019;9(10):1–9. 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-030547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Güzel A. Development of the disaster anxiety scale and exploring its psychometric properties. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2022;41:175–80. 10.1016/j.apnu.2022.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tang JS, Feng JY. Residents’ disaster preparedness after the Meinong Taiwan earthquake: A test of protection motivation theory. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(7):1434. 10.3390/ijerph15071434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bubeck P, Wouter Botzen WJ, Laudan J, Aerts JC, Thieken AH. Insights into flood-coping appraisals of protection motivation theory: empirical evidence from Germany and France. Risk Anal. 2018;38(6):1239–57. 10.1111/risa.12938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bell MA, Dake JA, Price JH, Jordan TR, Rega P. A National survey of emergency nurses and avian influenza threat. J Emerg Nurs. 2014;40(3):212–7. 10.1016/j.jen.2012.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leigh L, Taylor C, Glassman T, Thompson A, Sheu JJ. A cross-sectional examination of the factors related to emergency nurses’ motivation to protect themselves against an Ebola infection. J Emerg Nurs. 2020;46(6):814–26. 10.1016/j.jen.2020.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee E, Seomun G. Structural model of the healthcare information security behavior of nurses applying protection motivation theory. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:1–13. 10.3390/ ijerph18042084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nouri M, Ghasemi S, Dabaghi S, Sarbakhsh P. The effects of an educational intervention based on the protection motivation theory on the protective behaviors of emergency ward nurses against occupational hazards: a quasi-experimental study. BMC Nurs. 2024;23(1):1–10. 10.1186/s12912-024-02053-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Şahin SK, Aydin Z. Evaluation of nurses’ competency, motivation, and stress levels in disaster management. Disaster Med Pub Health Prep. 2024;18:e251. 10.1017/dmp.2024.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Karagöz Y. SPSS 21.1 Uygulamalı Biyoistatistik. Ankara: Nobel Yayın Dağıtım; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li HY, Bi RX, Zhong QL. The development and psychometric testing of a disaster response Self-Efficacy scale among undergraduate nursing students. Nurse Educ Today. 2017;59:16–20. 10.1016/j.nedt.2017.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Koca B, Çağan Ö, Türe A. Validity and reliability study of the Turkish version of the disaster response self-efficacy scale in undergraduate nursing students. Acıbadem Üniversitesi Sağlık Bilimleri Dergisi. 2020;3515–21. 10.31067/0.2020.301.

- 29.Lee SA. Coronavirus anxiety scale: A brief mental health screener for COVID-19 related anxiety. Death Stud. 2020;44(7):393–401. 10.1080/07481187.2020.1748481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Evren C, Evren B, Dalbudak E, Topcu M, Kutlu N. Measuring anxiety related to COVID-19: A Turkish validation study of the coronavirus anxiety scale. Death Stud. 2020;3:1–7. 10.1080/07481187.2020.1774969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hayes AF. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A Regression-Based approach (Methodology in the social Sciences). 2nd ed. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Lee JY, Podsakoff NP. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J Appl Psychol. 2003;88(5):879–903. 10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Podsakoff NP. Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Ann Rev Psychol. 2012;63:539–69. 10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang Y, Zhang Y, Liu Y, Li Q, Wang L, Du Y, Jin J. The associated factors of disaster literacy among nurses in china: A structure equation modelling study. BMC Nurs. 2024;23(855):1–10. 10.1186/s12912-024-02486-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Arbon P, Ranse J, Cusack L, Considine J, Shaban RZ, Woodman RJ, Bahnisch L, Kako M, Hammad K. Mitchell B. Australasian emergency nurses’ willingness to attend work in a disaster: A survey. Australasian Emerg Nurs J. 2013;16(2):52–7. 10.1016/j.aenj.2013.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hendrickx C, Van Turnhout P, Mortelmans L, Sabbe M, Peremans L. Willingness to work of hospital staff in disasters: a pilot study in Belgian hospitals. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2017;32:21–21. 10.1017/S1049023X17000759. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Labrague LJ, Kamanyire JK, Achora S, Wesonga R, Malik A, Al Shaqsi S. Predictors of disaster response self-efficacy among nurses in Oman. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct. 2021;61:102300. 10.1016/j.ijdrr.2021.102300. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stergachis A, Garberson L, Lien O, D’Ambrosio L, Sangaré L, Dold C. Health care workers’ ability and willingness to report to work during public health emergencies. Disaster Med Pub Health Prep. 2011;5(4):300–8. 10.1001/dmp.2011.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Farokhzadian J, Shahrbabaki PM, Farahmandnia H, Eskici GT, Goki FS. Exploring the consequences of nurses’ involvement in disaster response: findings from a qualitative content analysis study. BMC Emerg Med. 2024;24(74):1–11. 10.1186/s12873-024-00994-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rogers RW. Cognitive and physiological processes in fear appeals and attitude change: a revised theory of protection motivation. Social psychophysiology. Basic Social Psych Res. 1983;153–76.

- 41.Rogers RW. A protection motivation theory of fear appeals and attitude change. J Psychol. 1975;91(1):93–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Alquwez N. Nurses’ self-efficacy and well‐being at work amid the COVID‐19 pandemic: A mixed‐methods study. Nurs Open. 2023;10(8):5165–76. 10.1002/nop2.1752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Soylu D, Soylu A, Seven A. The perception of disaster preparedness and disaster Repsonse self-efficacy of nurses following the Kahramanmaraş earthquake on February 6, 2023: A pathway analysis. Disaster Med Pub Health Prep. 2025;19(20):1–12. 10.1017/dmp.2025.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kuday AD, Erdoğan Ö. Relationship between emotional intelligence and disaster response self-efficacy: A comparative study in nurses. Int Emerg Nurs. 2023;70:1–6. 10.1016/j.ienj.2023.101319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.