Abstract

Objective

This study aims to identify the bioactive components of Qing-Wei-San (QWS) for treating periodontitis and to uncover their mechanisms using computational pharmacology. By constructing a comprehensive pharmacological network, this study seeks to identify key targets and active components associated with periodontitis, providing scientific evidence for the optimization, mechanistic analysis, and clinical application of TCM.

Methods

Through bioinformatics analysis, periodontitis-associated pathogenic genes were identified from the DisGeNET and GEO databases. Meanwhile, all components of QWS were retrieved from the TCMSP database, TCM Integrated Database, and TCM Database@Taiwan. These components were then subjected to further screening to identify potential bioactive compounds. A component-target-target network was constructed using protein-protein interaction data, pathogenic genes, and active components. The network was validated using a computational network pharmacology model to identify equivalent component groups. The anti-inflammatory effects of these components on RAW264.7 cells were assessed via CCK8, NO, qRT-PCR, and Western Blot assays. Additionally, molecular docking was performed with AutoDock Tools to evaluate the binding affinity between equivalent components and core targets.

Results

We designed a novel computational systems pharmacology model that integrates the targets of the traditional Chinese medicine QWS with periodontitis-associated pathogenic genes, forming a Core Effect Space (CES). Node importance was calculated using a new method to identify active proteins within this space. Subsequently, approximate equivalent component group (AECG) capable of mediating these active proteins was screened based on a cumulative contribution rate model. The systems pharmacology results indicate that the targets of the AECG derived from the optimized CES effectively cover both drug targets and pathogenic genes at the functional level. Experimental results demonstrate that Ethyl ferulate, Methyl protocatechuate, and quercetin significantly reduce the expression levels of inflammatory factors in an inflammatory environment.

Conclusion

This study can predict the key bioactive components and mechanisms of action of QWS in the treatment of periodontitis, providing a methodological reference for the optimization, mechanistic analysis, and further development of TCM.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12906-025-04967-y.

Keywords: QWS, Periodontitis, Computational Pharmacology, Core effect space, Stacked contribution index

Introduction

Periodontitis is a chronic inflammatory disease affected by multiple influencing factors, and its main clinical manifestation is the destruction of periodontal supporting tissues. Currently, there are various treatment approaches for periodontitis, including surgical interventions, pharmaceutical treatments, and fundamental periodontal therapies. Conventional pharmaceutical treatments often involve the use of antibiotics and other medications to mitigate the destruction of periodontal tissues [1]. On the other hand, surgical interventions are reserved for severe cases of periodontitis but are associated with significant trauma and a high risk of postoperative relapse [2]. The above treatment methods have certain limitations. For instance, long-term use of antibiotics could induce drug resistance, and surgical treatment can result in significant trauma. It is necessary to identify alternative treatment methods.

Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) has been shown to be effective in treating periodontitis, according to both clinical studies and practical applications. For example, using a modified QWS combined with Scutellaria baicalensis tablets to treat aggressive periodontitis effectively alleviates patients’ clinical symptoms, with a total effective rate of 95.45% in the treatment group, higher than the control group (81.82%) [3]. These clinical studies collectively demonstrate that QWS can achieve favorable therapeutic effects in treating periodontitis. TCM herbal contains numerous bioactive compounds that can help alleviate inflammatory responses and promote tissue repair [4].Compared to conventional pharmaceutical treatments, TCM therapy may have fewer side effects and can be used over the long term. Research indicates that Gan-Lu-Yin extract can inhibit osteoclast differentiation and alveolar bone resorption in experimental periodontitis [5]. Compound EMW, a potential method for treating periodontitis, may reduce the expression levels of inflammatory factors such as IL-6 and TNF-α through the PI3K/AKT and NF-κB/MAPK signaling pathways [6].

QWS is a classic herbal formula based on TCM, which is composed of five botanical drugs. Angelica sinensis(Oliv.)Diels (Dang Gui, DG), a member of the Apiaceae family, is widely known for its ability to tonify the blood and alleviate inflammation. Its primary bioactive compounds, such as phenolic compounds, coumarins, and flavonoids, particularly angelicosides, exhibit anti-inflammatory and immune-modulatory properties. Picrorhiza kurroa Royle ex Benth. (Huang Lian, HL), from the Ranunculaceae family, is rich in berberine, a potent antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory agent. This herb is effective in treating infections and reducing inflammation. Rehmannia glutinosa (Gaertn.) Libosch. ex DC. (Di Huang, DH), belonging to the Orobanchaceae family, contains iridoid glycosides like rehmannoside, along with flavonoids and polysaccharides, and is known for its blood-nourishing, liver- and kidney-regulating, and anti-inflammatory effects. Paeonia × suffruticosa Andrews (Mu Dan Pi, MDP), native to China, contains paeoniflorin, which provides anti-inflammatory, analgesic, and antispasmodic properties, making it useful for conditions involving blood stagnation and pain. Actaea cimicifuga L. (Sheng Ma, SM), a member of the Ranunculaceae family, contains triterpenoid saponins like actein, and offers anti-inflammatory, analgesic, and antimicrobial effects, while also raising yang and clearing toxins from the body. (Supplementary Table S1) [7].Together, these herbs in QWS work synergistically to regulate inflammation, improve blood circulation, and enhance immune response, making the formula particularly effective in treating periodontal diseases like periodontitis. It is commonly used to treat periodontitis with significant therapeutic effects in modern clinical practice. Previous studies have shown that QWS, either alone or combined with other traditional formulas such as Yu-Nv-Jian, can effectively reduce periodontal inflammation by inhibiting proinflammatory cytokines and matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), and by lowering the levels of key pathogenic bacteria such as Porphyromonas gingivalis (Pg), Tannerella forsythia (Tf), and Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans (Aa) in gingival crevicular fluid of periodontitis rats [8]. In clinical settings, modified QWS formulations have also been reported to significantly improve periodontal symptoms in patients with stomach-fire type chronic periodontitis [9]. Furthermore, integrated chemical profiling using UPLC-Q-TOF-MS and GC-MS, along with network pharmacology and molecular docking, has preliminarily revealed that QWS acts through multi-component, multi-target, and multi-pathway interactions involving inflammatory and immune signaling pathways [10].However, these studies primarily focus on therapeutic outcomes or preliminary mechanism analyses, without systematically identifying and optimizing the core bioactive component combinations responsible for these effects. To address this gap, we applied an integrated systems pharmacology approach combining network topology analysis and a multi-objective optimization model. We identified the core therapeutic targets and constructed an Approximate Equivalent Component Group (AECG) of QWS, which was further validated by in vitro experiments, offering a novel and simplified strategy for studying the pharmacological mechanisms of TCM formulas.

TCM often presents challenges in accurately identifying its effective components and mechanisms due to its complex composition and diverse treatment mechanisms. This complexity brings the big challenge to the secondary development and clinical application of TCM formulas. To better explore the underlying mechanisms of TCM formulas and optimize the formula, it’s necessary to identify AECG within these formulas and eliminate potentially adverse components. Currently, several pharmacological and bioinformatics methods have been employed to analyze the key active components and potential mechanisms of TCM [11]. Some pharmacological analysis models, however, have focused solely on analyzing the compound-target network, neglecting the spread of therapeutic effects from drug targets to pathogenic genes. Therefore, it is desirable to design a model that predicts and analyzes the effectiveness of the spread from components of TCM to drug targets and pathogenic genes. The main advantage of the model lies in its consideration of the characteristics of complex prescriptions with multiple-components, multiple-targets, and multiple-pathways. It models and computes the propagation of treatment effects and intervention characteristics through three aspects: node influence, control, and bridging. Through comparison with other models, the accuracy and reliability of our newly designed model have been thoroughly demonstrated. This provides methodological references for the optimization and further development of prescriptions.

We have designed a novel computational pharmacology model for drug analysis and to explore the therapeutic components and mechanisms of QWS in treating periodontitis. This is aimed at providing a theoretical foundation for the secondary development and optimization of QWS formulation. Through analysis of published literature reports and databases, potential pathogenic genes related to periodontitis were identified. All components of QWS were obtained from databases and literature, followed by further screening to identify potentially effective components. Initially, three online prediction tools were employed to forecast effective targets. Subsequently, utilizing pathogenic genes and the active component-target network, an effective interaction network was established to identify effective proteins. Furthermore, using the stacked contribution index (SCI) model, the AECG of QWS was screened. Finally, the identified effective components were employed to predict the mechanisms of QWS in treating periodontitis.

Materials and methods

Pathogenic genes collection and detection of high-throughput data

We searched DisGeNET [12] using the keyword “periodontitis,” resulting in a total of 14 IDs related to periodontitis (Supplementary Table S2). These data were integrated to define the set of pathogenic genes associated with periodontitis. In the GEO [13] database, a search was conducted using the term “periodontitis” and the condition “Homo sapiens” under “Expression profiling by array”. This search yielded gene sequencing chip data encompassing both control and periodontitis groups. The GSE12484 gene chip dataset was downloaded, and the GPL96 gene annotation platform was selected. This dataset included neutrophil chip data from two periodontitis patients and two healthy control subjects. High-throughput sequencing data were utilized to validate the periodontitis-related pathogenic genes.

Development of weighted protein-protein interactions of periodontitis

To establish weighted protein-protein interactions(WPI)related to periodontitis, the comprehensive protein-protein interaction network were extracted from the online web servers, CMGRN [14] and PTHGRN [15]. Pathogenic genes with evidence codes from DisGeNET were assigned to the comprehensive PPI network and utilized to construct the WPI for periodontitis. Cytoscape (version 3.9.1) was employed for the visualization of the network.

Collection and arrangement of chemical components of QWS

QWS is developed by Li Gao in his monograph Secret Record of the Orchid Chamber in Jin dynasty. The composition of QWS is derived from three natural medicinal databases: TCMSP [16], TCM Integrated Database [17], and TCM Database@Taiwan [18]. We obtained a total of 541 components from the five herbs used in QWS, including SM, HL, MDP, DG, DH.

Screening of potential active components of QWS

We employed Lipinski’s Rule of Five for screening and obtained 178 potential active components from the initial pool of 541 [19]. The Lipinski’s Rule of Five is suitable for screening active pharmaceutical components and includes parameters such as molecular weight (MW), number of H-Bond acceptors (HBA), number of H-Bond donors (HBD), and rotatable bonds (RB). Fraction Csp3(Fsp3) reflects three-dimensional complexity and molecular saturation in drug-like compounds [20]. Meanwhile, three water solubility prediction methods based on computational models- Log S (ESOL) [21], Log S (Ali) [22] and LOG S (Silicas-IT) [23] were used to systematically evaluate the water solubility of small molecules. By quantifying the theoretical solubility of compounds in water, these models provide key parameter support for screening candidate drugs with ideal oral absorption potential, aiming at optimizing the bioavailability and pharmacokinetic characteristics of drugs. Small-molecule drugs also need to exhibit high GI absorption [24].Therefore, we selected the following screening conditions: MW ≤ 500, RB ≤ 10, HBA ≤ 10, HBD ≤ 5, Fsp3 ≥ 0.25, ESOL > -6.0; Ali> -6.0; Silicas-IT> -6.0 and high GI absorption(GI) [25]. Additionally, some components that didn’t meet the screening criteria but were reported in the literature to possess high concentrations and significant biological activity were included as supplements. These supplementary components were combined with the screened components for subsequent research.

Prediction of targets for potential active components

To identify the target-genes of the active components in QWS, we utilized the Open Babel toolkit (version 2.41) to convert chemical structures into standard SMILES format. We then employed online tools such as SEA [26], HitPick [27], and SwissTargetPrediction [28] for target identification.

Definition of core effect space and effective proteins

Node influence is a crucial topological attribute that can assess the influence of nodes in a network. Nodes with influence greater than the average node influence across all nodes are considered hub nodes within the network. In this context, we have devised a novel method for calculating node influence to evaluate the significance and impact of genes. Nodes represent components and drug targets, while edges depict interactions in the component-target-target(C-T-T) network. Following this principle, nodes with influence scores exceeding the average influence score are retained and combined with their edges to form the Core Effect Space (CES), where pivotal nodes are defined as effective proteins.

The detailed description of this method is as follows:

|

is the number of nodes in the network

is the number of nodes in the network  ;

; is all node set where the shortest path passes through node

is all node set where the shortest path passes through node  and

and  ; Nodes

; Nodes  and

and  belong to the set

belong to the set  ;

; represents all nodes in the network

represents all nodes in the network ;

; stands for the total number of the shortest paths passing through node

stands for the total number of the shortest paths passing through node  and

and  ;

; represents the sum of the shortest paths passing through node

represents the sum of the shortest paths passing through node  and

and  and simultaneously passing through node

and simultaneously passing through node  .If node

.If node  , then

, then  . If node

. If node  or node

or node  , then

, then  .

. stands for the number of neighbor nodes of node

stands for the number of neighbor nodes of node  and

and  .

. represents the number of neighbor nodes of node

represents the number of neighbor nodes of node  . If there is a direct connection between node

. If there is a direct connection between node  and node

and node  , then

, then  . When node

. When node  has fewer than two neighbors, the topological coefficient is defined as 0.

has fewer than two neighbors, the topological coefficient is defined as 0. is the shortest path from node

is the shortest path from node  to node

to node  .

.

Through the CES algorithm, the drug targets and pathogenic genes within the C-T-T network are scored. Among these nodes, those with a score greater than the mean CES value of all nodes are labeled as 1; otherwise, they are labeled as 0. This labeling is then redefined as the set  .

.

|

|

Set  represents the collection of node labels within the network, where each

represents the collection of node labels within the network, where each  corresponds to its unique

corresponds to its unique

|

Nodes within set  that are labelled as 1 are defined as effective proteins and the corresponding network is defined as the CES.

that are labelled as 1 are defined as effective proteins and the corresponding network is defined as the CES.

Design SCI to select AECG

The AECG is present in components within the CES. We denote the network coverage of every component  in the CES as

in the CES as  . The superposition index of targeted to pathogenic genes as

. The superposition index of targeted to pathogenic genes as  . The estimated maximum network coverage of AECG is

. The estimated maximum network coverage of AECG is  . Among the variables,

. Among the variables,  ,selecting AECG from

,selecting AECG from  components, therefore the SCI of targeted pathogenic genes is maximum. The method is described in detail as follows:

components, therefore the SCI of targeted pathogenic genes is maximum. The method is described in detail as follows:

|

|

The treatment mechanism of QWS for periodontitis is set as a sub-problem of the specified problem as:

|

|

is the best option when the prospective network coverage is

is the best option when the prospective network coverage is  ,and the optional component is

,and the optional component is  . According to the characteristics of the optimum substructure, the recursive formula for calculating

. According to the characteristics of the optimum substructure, the recursive formula for calculating  can be built as follows:

can be built as follows:

|

|

Gene ontology and pathway functional analysis

To evaluate functions of targeted genes and pathogenic genes, clusterProfiler package in R software was employed to performing GO [29] and KEGG analysis [30]. The  -value < 0.05 was used as the cutoff for statistical significance in the data processing.

-value < 0.05 was used as the cutoff for statistical significance in the data processing.

Molecular docking validation

Download the structural files for “PI3K”,“AKT”,“ERK” and “p38” from the PDB database (https://www.rcsb.org/). Obtain basic information about AECG from the PubChem database (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). Use Pymol to remove water molecules and small molecule ligands from the key target structures. Process the structures using AutoDock Tools and AutoDock Vina software, and visualize the results using Pymol for analysis.

Key resources table

| Reagent or Resource | Source | Identifier |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| β-actin | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#58,169, RRID: AB_2750839 |

| AKT | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#4691, RRID: AB_915783 |

| Phospho-AKT (p-AKT) | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#4060, RRID: AB_2315049 |

| p38 MAPK | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#8690, RRID: AB_10999090 |

| p-p38 | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#4511, RRID: AB_2139682 |

| 44/42 MAPK (Erk1/2) | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#4695, RRID: AB_390779 |

| Phospho-44/42 MAPK (p-Erk1/2) | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#4370, RRID: AB_2315112 |

| PI3K | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#4292, RRID: AB_329869 |

| p-PI3K | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#4228, RRID: AB_659940 |

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| Ethyl ferulate (HPLC ≥ 98%) | Jingzhu Biotechnology Co., Ltd | 4046-02-0 |

| Methyl protocatechuate (HPLC ≥ 98%) | Jingzhu Biotechnology Co., Ltd | 2150-43-8 |

| quercetin (HPLC ≥ 98%) | Jingzhu Biotechnology Co., Ltd | 117-39-5 |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium | ThermoFisher Biochemical Products Co., Ltd | Cat# C11995500BT |

| fetal bovine serum | ThermoFisher Biochemical Products Co., Ltd | Cat# FSP500 |

| Cell Counting Kit-8 | NCM | Cat#C6005 |

| The RNA Easy Fast Tissue/Cell Kit | Magen | Cat# R4010-03 |

| The EasyScript One-Step gDNA Removal and cDNA Synthesis SuperMix | Transgene | Cat#AU341-02-V2 |

| SYBR Green Pro Taq HS qPCR Kit | Vazyme | Cat#Q712-02 |

| lysis buffer | Sigma | Cat#20–188 |

| BCA kit | ThermoFisher Biochemical Products Co., Ltd | Cat#A53226 |

| sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis | Beyotime | Cat# P0561 |

| Tris Buffered Saline with Tween | Beyotime | Cat# ST673 |

| Chemiluminescence detection kit | Abbkine | Cat#BMU102-CN |

| The total NO assay kit | Beyotime | Cat#S0021S |

| PVDF membrane | Millipore | Cat# IPVH00010 |

| Experimental models: Cell lines | ||

| RAW264.7 cells | Cell Bank of the Chinese Academy of Sciences | N/A |

| Experimental models: Organisms/strains | ||

| LPS | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#93572-42-0 |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| Primer: GAPDH-Forward | This paper | 5’-CCATCACCATCTTCCAGGAG’-3 |

| Primer: GAPDH-Reverse | This paper | 5’- ATGATGACCCTTTTGGCTCC’-3 |

| Primer: IL6-Forward | This paper | 5’-CTGCAAGAGACTTCCATCCAG’-3 |

| Primer: IL6-Reverse | This paper | 5’-AGTGGTATAGACAGGTCTGTTGG’-3 |

| Primer: iNOS-Forward | This paper | 5’- GTTCTCAGCCCAACAATACAAGA’-3 |

| Primer: iNOS-Reverse | This paper | 5’- GTGGACGGGTCGATGTCAC’-3 |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| Cytoscape Version:3.9.1 | Cytoscape | https://cytoscape.org |

| Open Babel toolkit (version 2.41) | Open Babel toolkit | https://openbabel.org/wiki/Main_Page |

| GraphPad Prism8.0 | GraphPad | https://www.graphpad.com/ |

Cell culture

RAW264.7 cells were cultured in DMEM containing 8% FBS and maintained in a constant-temperature incubator at 37℃ with 5% CO2. The culture medium was replaced every 1–2 days. When the density of RAW264.7 cells reached approximately 80%, they were passaged using a 1:2 or 1:3 ratio. Cells (1 × 104 /well) were seeded in a 96-well plate until they reached a confluence of 80%. Subsequently, they were treated with LPS (1 µg/ml) for 2 h. Then, they were separately treated with Ethyl ferulate, Methyl protocatechuate, and quercetin for 24 h.

Cell viability assay

RAW264.7 cells were seeded in a 96-well plate at a density of 1 × 104 cells/ml. Subsequently, the cells were treated with varying concentrations of Ethyl ferulate (12.5, 25, 50, 100, and 200µM), Methyl protocatechuate (6.25, 12.5, 25, 50, and 100 µM), and quercetin (6.25, 12.5, 25, 50, and 100 µM). After 24 h, 10 µl of CCK-8 solution was added to each well. Following a 2-hour incubation, the absorbance was measured at 450 nm using a microplate reader (Infinite M200, TENAN, Switzerland) to quantify cell viability [31].

Assay the content of NO

RAW264.7 cells were first treated with LPS (1 µg/ml) for two hours, followed by the addition of Ethyl ferulate, Methyl protocatechuate, and quercetin. After 24 h of incubation, the culture supernatant was extracted and merged with the total NO assay kit. Subsequently, the absorbance was determined at 540 nm using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay reader (Tecan Infinite M200) [32].

qRT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated from RAW264.7 cells using the RNA Easy Fast Tissue/Cell Kit. cDNA was synthesized using the EasyScript One-Step gDNA Removal and cDNA Synthesis SuperMix for reverse transcription. qRT-PCR was performed using the SYBR Green on the ABI 7500 Real-Time PCR System (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The mRNA relative expression of the target gene was normalized to GAPDH [33].

Western blot analysis

Cell lysates were prepared in a lysis buffer. Protein concentrations were determined using the BCA kit. Samples were loaded onto SDS-PAGE and then transferred to a PVDF membrane. The membrane was blocked with 5% nonfat milk for 1 h and then incubated with primary antibodies at 4 °C for 12 h. After incubation, the membrane was washed three times with 1x TBST for ten minutes each. Subsequently, the membrane was incubated with secondary antibodies at room temperature for 1 h. Chemiluminescence detection was performed using a detection kit and visualized using a gel imaging system [34].

Statistical analysis

All measurement data were expressed as the mean ± SD and were analyzed by GraphPad Prism8.0 software (San Diego, CA, USA) with Student’s t-test. We regarded p-values < 0.05 as statistically significant.

Results

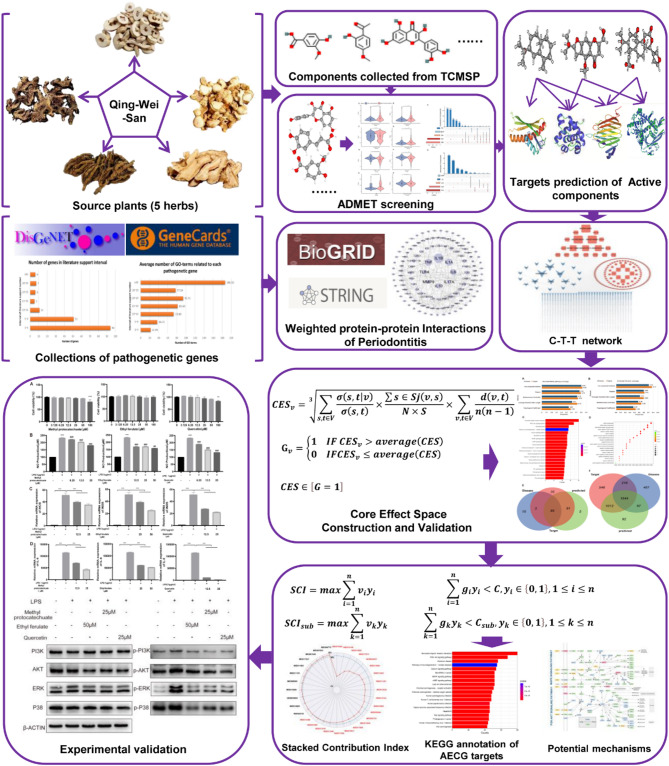

We developed a computational pharmacology-based framework to identify a cluster of AECG and reveal the potential molecular mechanisms on treating periodontitis in QWS (Fig. 1). Specifically, we initially constructed a weighted protein-protein interactions (WPI) of periodontitis based on the “number of literature supports.” Furthermore, all components of QWS were obtained from public databases. Subsequently, potential active components were screened from all QWS components using the previously established ADME method. The targets of the potential active components were predicted using established tools, and a C-T-T network was built using active components and their corresponding targets. Simultaneously, a node influence model was designed to determine the CES and effective proteins in the C-T-T network. Based on this, a SCI model was devised to pick out AECG. Lastly, the potential molecular mechanisms of QWS on periodontitis were predicted and validated based on AECG.

Fig. 1.

Computational pharmacology workflow.

Identification and collection of pathogenic genes

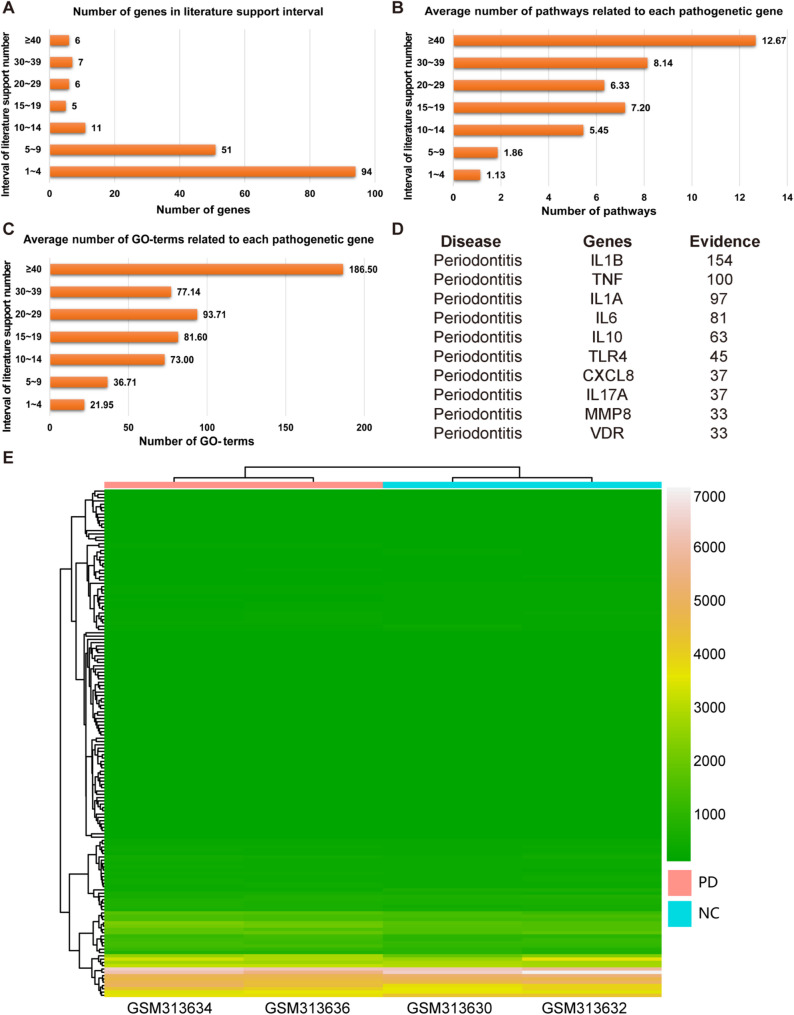

Genes related to the process of periodontitis can be marked as pathogenic genes at the level of diagnosis and intervention. To obtain a more comprehensive set of pathogenic genes, we extracted pathogenic genes related to periodontitis from literature confirmed in the DisGeNET database. A total of 180 genes were retained as significant pathogenic genes for periodontitis. Among them, 94 genes had at least one published literature supporting their relevance, and 24 genes were supported by over 15 published literature sources (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2.

Study situations of Pathogenic Genes. (A): Number of genes varies with the interval of literature support. (B): Average number of signaling pathways varies with intervals of literature support. (C): Average number of GO terms varies with intervals of literature support. (D): Top ten pathogenic genes ranked by the number of literature support. (E): Cluster analysis of pathogenic genes based on GSE12484

To validate whether genes with higher literature support have broader functionality, we conducted KEGG and GO enrichment analysis on all pathogenic genes, resulting in a total of 106 pathways and 2286 GO terms. It was observed that genes with greater literature support were associated with more pathways and GO terms. Genes with literature support ≥ 40 exhibited the highest average number of pathways and GO term associations (Fig. 2B, C). The top ten genes with the most literature support were IL1B, TNF, IL1A, IL6, IL10, TLR4, CXCL8, IL17A, MMP8, and VDR (Fig. 2D). These genes are primarily involved in regulating the inflammatory response related to periodontitis. Interleukin-6 (IL6) may aggravate local inflammation by increasing VEGF expression and enhancing vascular permeability [35]. Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) recognizes LPS and produces pro-inflammatory cytokines, regulating immune cell activity [36].

The expression profile of high-throughput sequencing data can typically differentiate the disease group from the control group and serves as one of the main methods to assess data reliability. We extracted the gene expression profile from the GSE12484 dataset and conducted clustering analysis, revealing that the gene profile could be divided into two clusters, one is normal and the other is periodontitis. These results indicate that the validation dataset could reflect the internal differences between normal and periodontitis. To validate the accuracy of the selected pathogenic genes from DisGeNET, we performed a clustering analysis on the expression profiles of the pathogenic genes extracted from the GSE12484 dataset. The results demonstrated that the pathogenic genes we selected could also distinguish between the disease group and the normal group (Fig. 2E). These findings further validate the reliability of the pathogenic genes we identified (Supplementary Table S3).

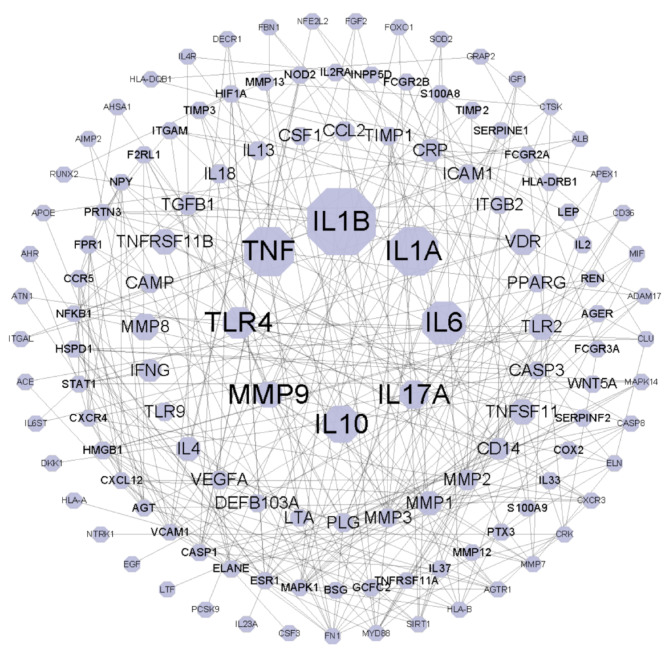

Development of WPI of periodontitis

The construction of the WPI for periodontitis pathogenic genes is essential for understanding the underlying mechanisms of periodontitis and providing intervention strategies for its treatment. To build the WPI of periodontitis, we integrated PPI data from CMGRN, PTHGRN, BioGRID, and STRING into a comprehensive PPI network. This network consists of 127 nodes and 297 edges (Fig. 3). Pathogenic genes like IL1B, TNF, and IL1A exhibit high-weight scores within the network and are supported by a substantial number of publications, with counts of 154, 100, and 97, respectively. Furthermore, according to published literature, these genes are prominently associated with key signaling pathways such as PI3K-Akt signaling pathway (hsa04151) (IL6, TLR4), and MAPK signaling pathway (hsa04010) (TNF, IL1A). These findings and pathway analyses indicate that the WPI of pathogenic genes accurately reflect the involvement of pathogenic genes in periodontitis. This also establishes a reliable foundation for constructing the CES in the subsequent steps (Supplementary Table S4).

Fig. 3.

Weighted protein-protein interactions of periodontitis. Node sizes vary based on their weights

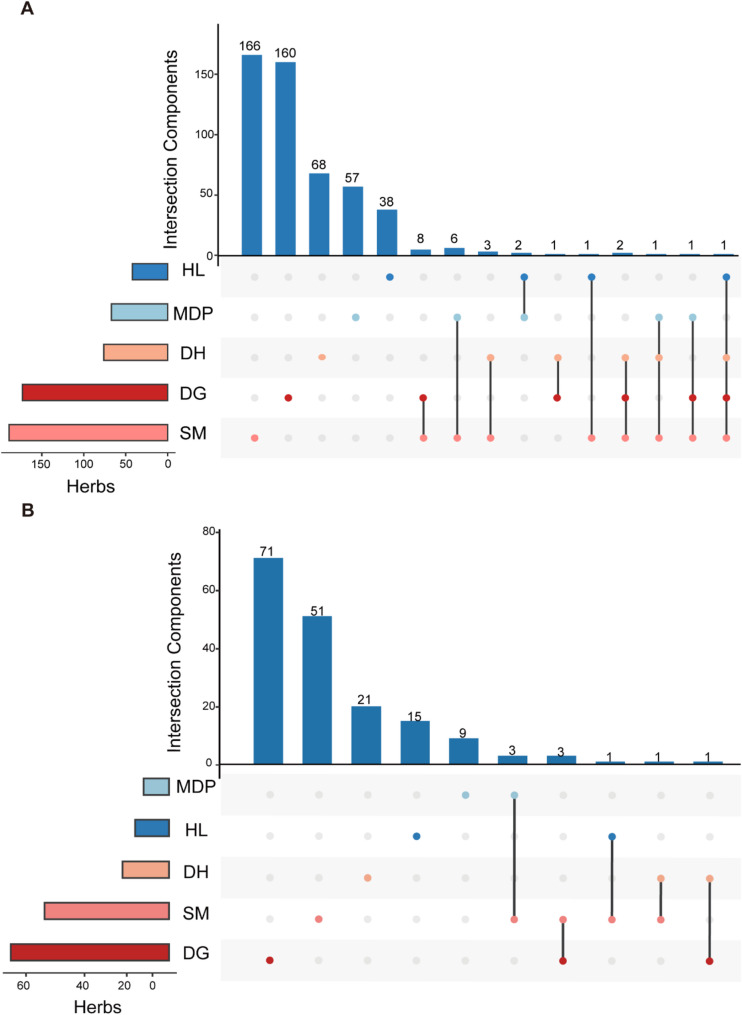

Collection of chemical components of QWS and screening of potential active components

We extracted a total of 541 components from the five botanical herbs in QWS from databases including TCM@Taiwan, TCMID, and TCMSP. Among them, SM, HL, DH, MDP, and DG contributed 188, 42, 76, 66, and 169 components, respectively. TCM are typically composed of multiple components, with only a small fraction exhibiting desirable pharmacological and pharmacokinetic attributes. In this study, we conducted a screening of QWS’s active components based on nine ADME-related pharmacokinetic attributes. After ADME screening, 178 active components from QWS were retained (Supplementary Table S5) (Fig. 4). Additionally, chemical analysis plays a crucial role in elucidating the substance basis and molecular mechanisms of complex formulations. By extracting concentrations of specific chemical components from published literature concerning QWS, we identified an additional 27 components from the five botanical herbs (Table 1). Combining the ADME-screened components with the high-concentration components resulted in a total of 205 active components. To further illustrate the differences between components before and after ADME screening, we compared eight properties in the screening criteria and employed the R package to generate violin plots. Except for FC3 (p = 0.407) and SIL (p = 0.087), all other chemical components and properties exhibited statistically significant differences before and after screening. These findings indicate that the components retained after ADME screening possess superior pharmacological properties.

Fig. 4.

Distribution of pharmacological characteristics of botanical herbs before and after ADME screening. Blue represents the distribution of components after ADME screening, while pink represents the distribution of components before ADME screening

Table 1.

Chemical analysis information of components in QWS

| Formula | ID | Method | component | concentration | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HL | MID000949 | 2D-HPLC | berberine | 59.1167 mg/g | Li et al. [37] |

| HL | MID001684 | 2D-HPLC | columbamine | 4.05 mg/g | Li et al. [37] |

| HL | MID001732 | 2D-HPLC | coptisine | 19.8 mg/g | Li et al. [37] |

| HL | MID004996 | 2D-HPLC | jatrorrhizine | 3.6333 mg/g | Li et al. [37] |

| HL | MID007109 | 2D-HPLC | palmatine | 15.6 mg/g | Li et al. [37] |

| HL | MID016085 | 2D-HPLC | epiberberine | 10.7833 mg/g | Li et al. [37] |

| SM | MID010065 | HPLC | caffeic acid | 0.68 mg/g | Cai et al. [38] |

| SM | MID015631 | HPLC | isoferulic acid | 1.95 mg/g | Cai et al. [38] |

| DH | MID005015 | RP-HPLC | Jionoside B1 | 0.6793 mg/g | Zhang et al. [39] |

| DH | MID005671 | RP-HPLC | Martynoside | 0.4642 mg/g | Zhang et al. [39] |

| DH | MID012604 | RP-HPLC | Catalpol | 1.3531 mg/g | Zhang et al. [39] |

| DH | MID016238 | RP-HPLC | Acteoside | 0.6348 mg/g | Zhang et al. [39] |

| DG | MID001474 | HPLC | Chlorogenic acid | 0.5508 mg/g | Yang et al. [40] |

| DG | MID001685 | HPLC | columbianadin | 0.0308 mg/g | Yao et al. [41] |

| DG | MID008259 | HPLC | Senkyunolide A | 0.1008 mg/g | Yao et al. [41] |

| DG | MID008261 | HPLC | Senkyunolide H | 0.0087 mg/g | Yao et al. [41] |

| DG | MID017931 | HPLC | Coniferyl ferulate | 1.3517 mg/g | Yao et al. [41] |

| DG | NEWID0001 | HPLC | ferulate acid | 0.7514 mg/g | Yao et al. [41] |

| DG | NEWID0002 | HPLC | Senkyunolide I | 0.0167 mg/g | Yao et al. [41] |

| DG | NEWID0003 | HPLC | Z-Ligustilide | 15.3681 mg/g | Yao et al. [41] |

| DG | NEWID0004 | HPLC | 3-n-Butylphthalide | 0.07 mg/g | Yang et al. [40] |

| MDP | MID000930 | HPLC | Benzoylpaeoniflorin | 0.956-2.363 mg/g | Xie et al. [42] |

| MDP | MID003520 | HPLC | Gallic acid | 1.264-3.207 mg/g | Xie et al. [42] |

| MDP | MID007098 | HPLC | Paeoniflorin | 4.540-8.902 mg/g | Xie et al. [42] |

| MDP | MID010699 | HPLC | Paeonol | 10.86-19.28 mg/g | Xie et al. [42] |

| MDP | MID016685 | HPLC | Oxypaeoniflorin | 0.7935-2.146 mg/g | Xie et al. [42] |

| MDP | NEWID0005 | HPLC | 1,2,3,4,6-O-Pentagalloylglucose | 5.043-9.016 mg/g | Xie et al. [42] |

Common and unique components in QWS

Before ADME screening, five active components, FER (MID010199), sitosterol (MID010198), WLN: QR CQ DV1 (MID016551), Sitogluside (MID010196), and Stigmasterol (MID010287) shared by three or more herbs were identified (Fig. 5A). Among them, FER is also named ferulic acid, which is a component shared by HL, SM, DH, and DG. Previous reports have shown that FER possesses antioxidant activity and relieves the expression levels of TNF-α and IL-1β, thereby reducing cyclosporine-induced liver damage [43]. Except for common components, most herbs exert their therapeutic effects through their specific components. SM, MDP, HL, DH, and DG have 166, 57, 38, 68, and 160 unique components, respectively. After ADME screening, there are a total of eight components shared by two components, such as hexanoic acid (MID011848), lauric acid (MID010146), ferulic acid (NEWID0001), and so on. Among them, Lauric acid is a common component of SM and DH, which can down-regulate the TLR4 signaling pathway and inhibit lipopolysaccharide-induced liver inflammation through the TLR4/MyD88 signaling pathway [44]. After chemical property screening, there still exist common and unique components among various traditional medicines. This shows that QWS can not only play a role in treating periodontitis through the synergistic mode of common components but also through the targeted treatment mode of specific components.

Fig. 5.

Distribution of common and unique botanical components in QWS. (A): Distribution of botanical components in QWS before ADME screening. (B): Distribution of botanical components in QWS after ADME screening. UpSetR is used for plotting, where points represent components, and the corresponding histograms represent the number of active components. Unconnected points represent specific botanical components. Connected points represent shared botanical components

Target prediction and construction of C-T-T network

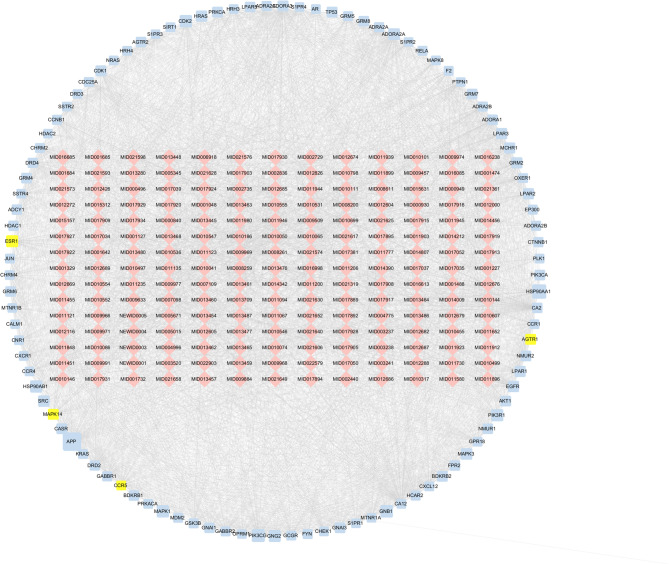

Drug action involves a complex interplay of various proteins or genes responding to stimuli. These proteins and genes are regulated by or interact with other proteins or genes during the development of diseases, forming a complex network associated with disease progression. To understand the targets through which the active components of QWS exert their therapeutic effects, we utilized 3 tools—SEA, HitPick, and Swiss Target Prediction—to predict target genes for the active components, resulting in 670 predicted target genes. To explore the therapeutic mechanism of QWS on periodontitis, we established a C-T-T network using the PPI network and the active component-target network (Supplementary Table S6). To clearly visualize the intrinsic connections within the C-T-T network, we constructed a condensed network by retaining the top 100 target nodes based on degree centrality. This streamlined C-T-T network comprises 296 nodes and 4,350 edges (Fig. 6), including:4 periodontitis pathogenic genes (representing 6.1% of pathogenic genes in the C-T-T network) and 96 target genes (accounting for 7.8% of all target genes in the C-T-T network). This indicates that some potential active components are simultaneously associated with multiple targets, and there are connections between different targets. The average number of targets per component is 29.39. Among these components, heptanoic acid (MID014390) has the highest number of targets, with 38. Among the targets, Carbonic anhydrase II(CA2) is related to the highest number of associations. Studies indicate that CA2 enters the serum as an acute phase protein without sialic acid after inflammatory stimulation, and its protein structure is recognized by specific monoclonal antibodies (mAb.2-4B) by mimicking di/oligoNeu5Gc structures, suggesting that CA2 may participate in the inflammatory response through molecular mimicry [45].These findings suggest that QWS exerts its effects on periodontitis through a multi-component, multi-target approach.

Fig. 6.

Streamlined C-T-T Network. Red nodes represent the components of QWS, blue nodes represent the target genes, yellow nodes represent periodontitis pathogenic genes

Common and unique drug targets in QWS

In order to further compare the consistency of the key drug targets in the potential activity grouping retained after ADME screening, the drug target information was drawn by UpSetR. After ADME screening, 184 components were retained in QWS. Although the number of components was reduced, the key drug target genes were retained (Fig. 7). A total of 1390 target genes were preserved by ADME screening, among which 377 target genes were shared by four or more herbs. Among them, CXCL12 is a common target of five herbs, which can enhance the differentiation of periodontal ligament stem cells, promoting bone tissue regeneration and angiogenesis [46].In addition, after screening, SM, MDP, HL, DH, and DG each retained 92, 72, 67, 16, and 182 unique targets. These results show that ADME screening simplifies the number of targets, but still retains the key targets, which is conducive to further exploring the mechanism of QWS in periodontitis treatment.

Fig. 7.

Distribution of common drug targets and unique targets in QWS. UpSetR is used for plotting, where points represent targets, and the corresponding histograms represent the number of targets. Unconnected points represent specific targets, while connected points represent shared targets

Validation of core effect space

The influence of nodes in a network is a crucial topological attribute for network evaluation. In this study, we introduced a novel method to calculate the influence scores of each node in the C-T-T network and obtained corresponding scores for each node. For each node, higher influence scores indicate a more significant role within the network structure, classifying it as a key node. We retained nodes that passed through the C-T-T network along with their edges, defining this subset as CES. All proteins within CES were designated as effective proteins. As a result, we selected 1266 effective proteins from the CES.

To validate the reliability and accuracy of our proposed method for calculating node influence in constructing the core effect space, we defined two reference standards: (1) the ratio of effective proteins to the number of enriched KEGG pathways, and (2) the ratio of effective proteins to the number of GO terms.

In the optimization of drug targets and disease-related genes, to further demonstrate the reliability and accuracy of our proposed model, we compared the node influence calculation method we introduced with other commonly used methods, including Average Shortest Path Length (Ave), Betweenness Centrality (Bet), Topological Coefficient (Top), and Degree (Deg). We obtained effective proteins using our model and these models, respectively, and performed pathway and GO enrichment analysis on these effective proteins. Then, we compared the percentages of enriched pathways and GO terms in the intervened pathways and intervened GO terms, respectively. The results indicated that using standard 1 as the evaluation criterion, in the optimization of disease-related genes, the proportions of Our proposed method, Ave, Bet, Top, and Deg were 0.80, 0.61, 0.72, 0.55, and 0.76, respectively. Simultaneously, in the optimization of drug targets, the proportions of Our proposed method, Ave, Bet, Top, and Deg were 0.82, 0.72, 0.73, 0.58, and 0.79, respectively (Fig. 8A). Using standard 2 as the evaluation criterion, in the optimization of disease-related genes, the proportions of Our proposed method, Ave, Bet, Top, and Deg were 0.70, 0.48, 0.51, 0.37, and 0.59, respectively. Simultaneously, in the optimization of drug targets, the proportions of Our proposed method, Ave, Bet, Top, and Deg were 0.77, 0.59, 0.54, 0.42, and 0.61, respectively (Fig. 8B). A higher proportion indicates higher reliability and accuracy. The results indicated that the percentage of effective protein-enriched pathways discovered in the pathway and GO terms enrichment using our model was higher than those obtained from Ave, Bet, Top, and Deg. These findings suggest that our model has higher accuracy and better functional coverage compared to other node influence assessment models.

Fig. 8.

Construction and Validation of the Core Effect Space. (A): Comparison of the pathway enrichment between our proposed model and other models in KEGG pathways.(B): Comparison of the enrichment of GO terms between our proposed model and other models.(C): Enrichment of effective protein pathways within the CES.(D): Enrichment of effective protein GO terms within the CES.(E): Venn diagram showing the overlap of enriched pathways among drug targets, disease-related genes, and CES targets.(F): Venn diagram showing the overlap of enriched GO terms among drug targets, disease-related genes, and CES targets

KEGG and GO enrichment analysis were conducted on the effective proteins within the CES, revealing that these proteins play a role in treating periodontitis. Among the 181 pathways analyzed, 96.59% of disease-related genes enriched pathways were covered (Fig. 8C, E). The PI3K-Akt signaling pathway, for instance, participates in regulating bone metabolism levels during inflammation [47]. Moreover, among the 2715 GO terms analyzed, a coverage of 87.72% of disease-related genes enriched GO terms was achieved. Among these GO terms, some were closely related to the pathogenesis of periodontitis, such as positive regulation of MAPK cascade (GO:0043410), response to oxidative stress (GO:0006979), and regulation of inflammatory response (GO:0050727) (Fig. 8D, F). These findings suggest that our model effectively retains potential therapeutic targets at the functional coverage level. (Supplementary Table S7)

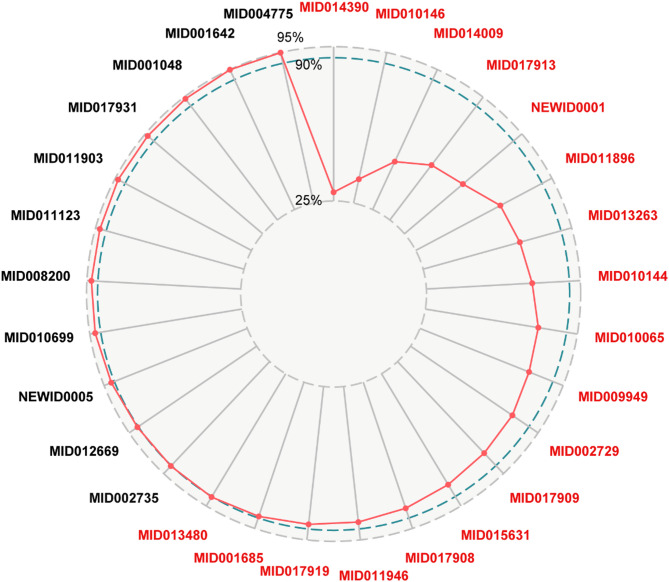

Determination and validation of the approximate equivalent component group

We established a SCI model to optimize the CES, resulting in the identification of AECG (Table 2). The top seven ranked components in this group are MID014390, MID010146, MID014009, MID017913, NEWID0001, MID011896, and MID013263. These seven components collectively target 70.60% of the effective proteins. The components of 11 and 18, respectively, target 80.89% and 90.30% of the effective proteins. Thus, we selected the top 18 components as the AECG (Fig. 9). The high coverage of effective proteins suggests that the AECG may possess critical therapeutic effects and exert a combined impact on the treatment of periodontitis.

Table 2.

Information of AECG in QWS

| ID | component name | Formula | MW | Fraction Csp3 | Rotatable bonds | H-bond acceptors | H-bond donors | ESOL Log S | Ali Log S |

Silicos-IT LogSw | GI absorption |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MID014390 | heptanoic acid | C7H14O2 | 130.18 | 0.86 | 5 | 2 | 1 | -1.84 | -2.85 | -1.63 | High |

| MID010146 | lauric acid | C12H24O2 | 200.32 | 0.92 | 10 | 2 | 1 | -3.07 | -4.69 | -3.69 | High |

| MID014009 | Ethyl ferulate | C12H14O4 | 222.24 | 0.25 | 5 | 4 | 1 | -2.55 | -3.01 | -2.53 | High |

| MID017913 | 2-methyldodecan-5-one | C13H26O | 198.34 | 0.92 | 9 | 1 | 0 | -3.47 | -4.85 | -4.28 | High |

| NEWID0001 | ferulate acid | C10H10O4 | 194.18 | 0.1 | 3 | 4 | 2 | -2.11 | -2.52 | -1.42 | High |

| MID011896 | DEP | C12H14O4 | 222.24 | 0.33 | 6 | 4 | 0 | -2.62 | -3.17 | -3.37 | High |

| MID013263 | Methyl protocatechuate | C8H8O4 | 168.15 | 0.12 | 2 | 4 | 2 | -2.05 | -2.49 | -1.32 | High |

| MID010144 | caprylic acid | C8H16O2 | 144.21 | 0.88 | 6 | 2 | 1 | -2.26 | -3.5 | -2.05 | High |

| MID010065 | caffeic acid | C9H8O4 | 180.16 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 3 | -1.89 | -2.38 | -0.71 | High |

| MID009949 | quercetin | C15H10O7 | 302.24 | 0 | 1 | 7 | 5 | -3.16 | -3.91 | -3.24 | High |

| MID002729 | Dimethyl azelate | C11H20O4 | 216.27 | 0.82 | 10 | 4 | 0 | -2.07 | -3.21 | -2.87 | High |

| MID017909 | (Z)-2-Hexenyl hexanoate | C12H22O2 | 198.3 | 0.75 | 9 | 2 | 0 | -2.92 | -4.13 | -3.27 | High |

| MID015631 | isoferulic acid | C10H10O4 | 194.18 | 0.1 | 3 | 4 | 2 | -2.11 | -2.52 | -1.42 | High |

| MID017908 | 2-valerylbenzoic acid | C12H14O3 | 206.24 | 0.33 | 5 | 3 | 1 | -2.46 | -2.96 | -3.33 | High |

| MID011946 | senkyunolide-E | C12H12O3 | 204.22 | 0.25 | 2 | 3 | 1 | -2.46 | -2.49 | -2.88 | High |

| MID017919 | Undecanol-6 | C11H24O | 172.31 | 1 | 8 | 1 | 1 | -3.08 | -4.42 | -3.36 | High |

| MID001685 | columbianadin | C19H20O5 | 328.36 | 0.37 | 4 | 5 | 0 | -4.24 | -4.76 | -5.02 | High |

| MID013480 | Rehmaionoside C | C19H32O8 | 388.45 | 0.84 | 5 | 8 | 5 | -1.53 | -1.78 | -0.28 | High |

Fig. 9.

Stacked contribution index of effective components in CES

Experimental validation in vitro

To further decode the mechanisms of the AECG, five components were selected from the 18 components for experimental validation. The results demonstrated that Methyl protocatechuate, Ethyl ferulate, and quercetin could inhibit the expression levels of inflammatory factors. Additionally, the study suggested that the guided bone regeneration membrane prepared from lauric acid could slow down the growth and proliferation of Gram-negative bacteria, which is beneficial for periodontal tissue regeneration therapy [48]. LPS-induced RAW264.7 cells were employed to evaluate the potential anti-inflammatory effect of decisive components in vitro. The results of cell viability showed that Methyl protocatechuate at 3.125–50 µM, Ethyl ferulate at 3.125–100 µM, and quercetin at 3.125–50 µM had no obvious cytotoxicity to RAW264.7 cells (Fig. 10A).

Fig. 10.

Functional Validation of Methyl protocatechuate, Ethyl ferulate, and quercetin. (A): Impact on RAW264.7 Cell viability. (B): Impact on NO release levels. (C): Effect of drug treatment on IL-6 mRNA expression levels in LPS-treated RAW264.7 cells. (D): Effect of drug treatment on iNOS mRNA expression levels in LPS-treated RAW264.7 cells. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 compared to the control group (DMSO group). ###p < 0.001 compared to the positive control group (LPS group)

Subsequently, we observed the effect of these components on the production of NO in RAW264.7 cells under inflammatory conditions. Compared to the control group, treatment with LPS (1 µg/ml) significantly increased NO levels in the supernatant of RAW264.7 cells by 232.67%. However, Methyl protocatechuate (6.25, 12.5, and 25 µM), Ethyl ferulate (12.5, 25, and 50 µM), and quercetin (6.25, 12.5, and 25 µM) significantly reduced NO levels in the cell supernatant in a concentration-dependent manner (p < 0.0001) (Fig. 10B). These results indicate that Methyl protocatechuate, Ethyl ferulate, and quercetin effectively lower the levels of NO produced by LPS-induced RAW264.7 cells.

Furthermore, qRT-PCR results (Fig. 10C-D) showed that compared to the control group, the expression levels of the inflammatory factors iNOS and IL-6 were significantly increased in the LPS group. However, the addition of corresponding concentrations of Methyl protocatechuate (12.5 and 25 µM), Ethyl ferulate (25 and 50 µM), and quercetin (12.5 and 25 µM) significantly reduced the expression levels of iNOS and IL-6 and exhibited a concentration-dependent pattern (p < 0.0001). These findings suggest that Methyl protocatechuate, Ethyl ferulate, and quercetin from the approximate equivalent component group have inhibitory effects on the inflammatory response induced by LPS in RAW264.7 cells.

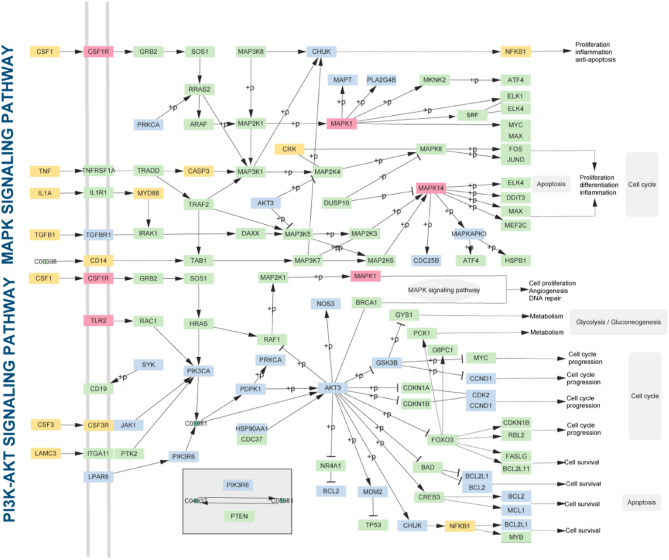

KEGG enrichment analysis of nearly equivalent compound group targets

To investigate the potential therapeutic mechanisms of QWS in treating periodontitis, we performed KEGG pathway enrichment analysis separately on the targets of the AECG and the targets of the disease-causing genes (Supplementary Table S7). We found that 10 out of the top 20 enriched pathways were common between the two sets, with pathways such as the PI3K-Akt signaling pathway (hsa04151) and MAPK signaling pathway (hsa04010) being widely associated with periodontitis progression and treatment. To further explore the underlying therapeutic mechanisms of the AECG, we constructed a comprehensive signaling pathway by integrating the PI3K-Akt and MAPK pathways (Fig. 11). Some proteins were found to be present in both pathways, such as AKT3 and PRKCA. Additionally, some proteins were identified as targets of both disease-causing genes and the core component group, like CSF1R and MAPK1. Thirty proteins were found to be active in the pathways and influenced by the AECG. Most of these proteins have been confirmed to be associated with periodontitis. In the PI3K-Akt and MAPK signaling pathways, proteins like MAPK1 can impact cell proliferation and inhibit apoptosis [49]. The results from the comprehensive signaling pathway analysis suggest that the AECG is crucial and effective in treating periodontitis. These effects are achieved through a multi-pathway biological process. This outcome indicates that when treating periodontitis, it’s important not only to consider the relationship between components and targets but also the interactions between different pathways.

Fig. 11.

Distribution of AECG targets and pathogenic genes in the integrated pathway diagram. The color code is as follows: yellow represents pathogenic genes, green represents pathway proteins, blue represents targets of the AECG, and red represents targets that are both pathogenic genes and part of the AECG

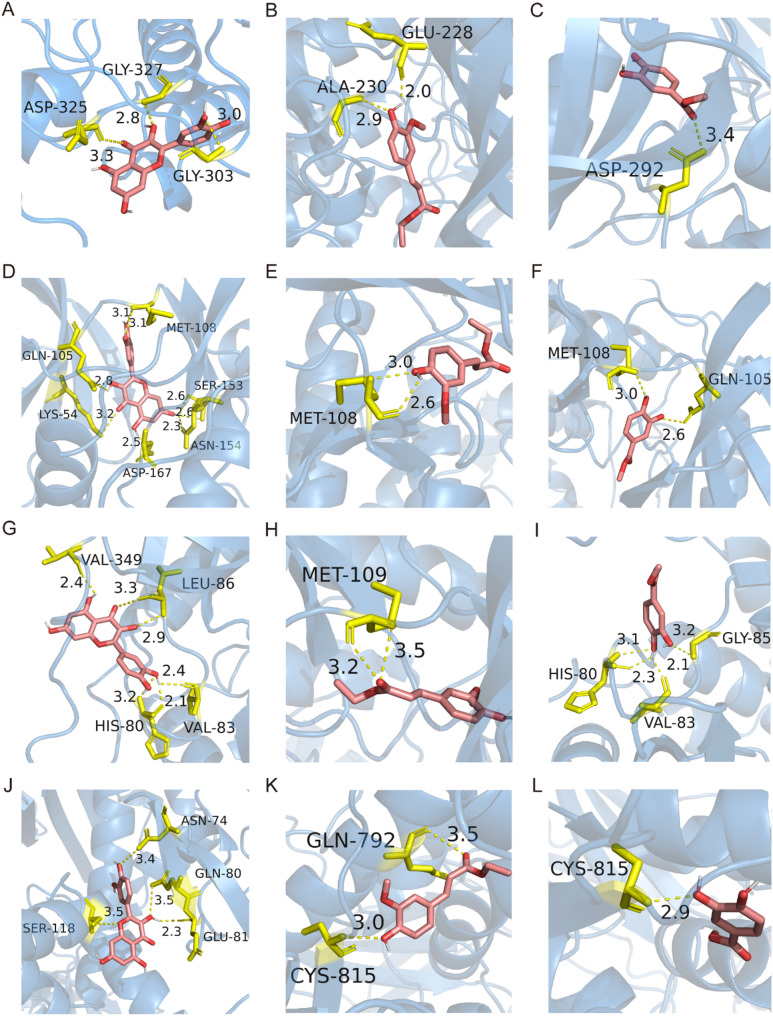

In order to further explore the interaction between Methyl protocatechuate, Ethyl ferulate, and quercetin and the key proteins (PI3K, AKT, ERK and p38) of the comprehensive signaling pathway, using molecular docking to simulate the binding of drugs to key proteins. A total of 108 molecular docking results were obtained by molecular docking simulation of three components and four key proteins. Among them, 12 docking relationships had the lowest binding free energies and were all not greater than − 5.0 kcal/mol (Fig. 12). These results indicated that Methyl protocatechuate, Ethyl ferulate, and quercetin had good binding ability to the key proteins of PI3K-Akt and MAPK signaling pathways.

Fig. 12.

Molecular docking results of Methyl protocatechuate, Ethyl ferulate, quercetin and pathway proteins. (A-D) Visualization on molecular docking results of quercetin-AKT, quercetin-ERK, quercetin-p38 and quercetin-PI3K; (E-H) Visualization on molecular docking results of Ethyl ferulate -AKT, Ethyl ferulate -ERK, Ethyl ferulate -p38 and Ethyl ferulate -PI3K; (I-L) Visualization on molecular docking results of Methyl protocatechuate -AKT, Methyl protocatechuate -ERK, Methyl protocatechuate -p38 and Methyl protocatechuate -PI3K

Subsequently, WB was performed to detect the activity of the PI3K-Akt and MAPK signaling pathways in RAW264.7 cells (Fig. 13). Compared to the control group, both pathways were activated in LPS-induced RAW264.7 cells. However, the expression levels of p-PI3K, p-AKT, p-P38, and p-Erk1/2 were reduced in the treatment groups, indicating that Methyl protocatechuate (25 µM), Ethyl ferulate (50 µM), and quercetin (50 µM) could inhibit the activity of these pathways in LPS-induced RAW264.7 cells. These results suggest that the core component group partially exerts its therapeutic effects on periodontitis by suppressing the PI3K-Akt and MAPK signaling pathways. Additionally, this validates the reliability and accuracy of the AECG.

Fig. 13.

Pathway enrichment analysis and validation of the AECG. Western blot analysis of protein expression levels of MAPK and PI3K-Akt signaling pathways in RAW264.7 cells induced by LPS and treated with Methyl protocatechuate (25µM), Ethyl ferulate (50µM), and quercetin (25µM)

Discussion

Periodontitis is a chronic inflammatory disease influenced by both plaque accumulation and the host immune response. The destruction of periodontal supporting tissue caused by periodontitis can lead to tooth loosening, which significantly affecting patients’ quality of life. Epidemiological surveys show that approximately 110 million people worldwide suffer from severe periodontal disease, significantly increasing the burden on global public health management [50]. Currently, the treatment of periodontitis involves a combination of basic therapy, surgical intervention, and medication. Following basic therapy, drugs are commonly administered either locally or systemically as part of the treatment regimen [51]. However, the use of local antimicrobial drugs may lead to local drug resistance and gastrointestinal reactions, making long-term use less favorable [52]. TCM, on the other hand, is often used in periodontitis treatment due to its lower toxicity and fewer side effects. Studies have demonstrated that the various components of the QWS formulation have significant therapeutic effects on periodontitis [53, 54]. These components can effectively promote bone formation, inhibit bone resorption, and control the progression of inflammation. TCM is well-suited for addressing complex diseases due to its composition of multiple components that act on various targets. Therefore, optimizing these relationships, identifying key synergistic components, and minimizing adverse effects are feasible starting points and significant driving factors in the optimization of TCM components.

Computational pharmacology analysis utilizes systems biology approaches to enhance the understanding of pharmacological behaviors at the molecular level within cells and tissues. Through this approach, scientists can systematically predict and interpret drug actions, optimize drug design, identify factors influencing drug efficacy and safety, and design multi-target drugs or drug combinations. However, there has been limited research utilizing system pharmacology to optimize TCM formulations for identifying functional constituents. Currently, researchers extract gene, protein data from various experimental methods to share information across diverse public databases [55]. This approach is highly beneficial for analyzing disease pathogenicity and therapeutic targets. The integration of computational pharmacology strategies with high-throughput data contributes to exploring the mechanisms of TCM treatments for complex diseases.

In this study, we devised a computational pharmacology strategy to optimize the AECG in QWS for the treatment of periodontitis and to unveil hidden molecular mechanisms. This model incorporates a novel node influence calculation method, utilizing this model to derive the CES and effective proteins, subsequently identifying AECG. Finally, based on AECG, the potential mechanisms of QWS in treating periodontitis were determined. In comparison to other computational pharmacology methods, our strategy boasts three primary advantages.

Firstly, we employed a novel node influence model to extract the CES and effective proteins. The influence of nodes in the network is determined by their communication closeness, bridging capacity, and control over neighboring nodes. A higher communication closeness indicates that a node occupies a critical position in the information flow within the network. A stronger bridging capacity reflects better connectivity in the network, making the node more significant. Greater control over neighboring nodes suggests a higher level of influence for that node. In summary, our newly designed model takes into account all the above characteristics, leading to more accurate assessments of node influence compared to other commonly used models.

Additionally, we employed the SCI model to select functionally equivalent components based on effective proteins, which proved to be an efficient approach. Our analysis revealed that the enriched pathways for the AECG were 173 (p < 0.05), and for the pathogenetic genes, they were 106 (p < 0.05). Moreover, the AECG covered 96.59% of the pathways enriched with pathogenetic genes.

The third advantage lies in the alignment of our predicted core components with evidence in the context of periodontitis treatment. Optimize the pharmaceutical composition by screening the common and specific components of QWS. For instance, quercetin, shared by MDP and HL, can alleviate the inflammatory reaction caused by imbalance of oral microbial flora and is considered to be a crucial component of periodontitis treatment [4]. Paeonol, a shared compound of MDP and SM, reduces alveolar bone resorption through the Nrf2/NF-κB/NFATc1 signaling pathway, inhibiting osteoclast differentiation [56]. Consequently, these components can be considered effective therapeutic agents for periodontitis.

According to the C-T-T network analysis, the majority of components are associated with the PI3K-AKT signaling pathway and MAPK signaling pathway, which are implicated in the mediation of inflammatory reaction. For instance, caffeic acid exhibits potent antioxidant properties and can inhibit LPS-induced signaling pathways such as p38 MAPK and JNK1/2, consequently restraining the production of NO by macrophages and demonstrating anti-inflammatory effects [57].Columbianadin has been found to reduce the expression levels of TNF-α and IL-1β in LPS-induced RAW 264.7 cells, inhibit iNOS and NO production, and reverse LPS-induced acute inflammatory liver injury [58].

To delve into the potential mechanisms of QWS in treating periodontitis, we conducted GO and KEGG pathway enrichment analysis using the targets identified within the AECG. Our findings reveal that QWS-regulated targets are significantly enriched in the PI3K-AKT signaling pathway and MAPK cascade processes. In addition, lipid rafts have been shown to play a crucial role in the activation of Wnt signaling [59], which is involved in the regulation of various inflammatory processes. Lipid rafts serve as signaling platforms, facilitating the interaction of Wnt receptors with downstream effectors, thus influencing inflammatory pathways [60]. Given the significant involvement of Wnt signaling in bone resorption and immune responses, it is likely that QWS modulates this pathway through lipid raft-mediated mechanisms. Furthermore, several genes involved in regulating inflammatory factors exhibit a strong correlation with periodontitis. For instance, the expression level of NLRP3 mRNA in gingival tissues of periodontitis patients is significantly higher than in periodontally healthy individuals, with NLRP3 mRNA expression positively correlated with IL-1β [61]. MAPK1, as one of the downstream targets of the MAPK pathway, has been implicated in promoting the production of IL-6 and TNF-α in macrophages [62]. Notably, the expression of TLR2 is upregulated in peripheral blood monocytes and macrophages of periodontitis patients. so TLR2 can serve as an indicator of inflammatory activity [63]. Collectively, our analysis suggests that QWS may exert its therapeutic effects in periodontitis through the regulation of crucial pathways like PI3K-AKT and MAPK signaling. Recent studies have demonstrated that disruption of lipid rafts by cholesterol-binding agents can reduce the expression of Tissue Factor (TF) [64], a key initiator of the coagulation cascade, and restore nitric oxide (NO) production [65]. Since NO has potent anti-inflammatory effects, this suggests that QWS may exert additional therapeutic benefits by modulating lipid raft dynamics, thereby influencing the coagulation cascade and inflammatory responses.

We further conducted in vitro experiments to assess whether the selected components have anti-inflammatory effects on periodontitis at the experimental level. LPS-induced RAW264.7 cells represent a classical model for studying inflammatory diseases and screening anti-inflammatory substances. Inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) is a crucial intracellular enzyme, and its induction by pro-inflammatory cytokines in macrophages leads to increased iNOS expression, producing a large amount of NO and promoting inflammation progression [66]. In this study, we confirmed that the three selected components, Methyl protocatechuate, quercetin, and ethyl ferulate, effectively reduced NO levels in LPS-induced RAW264.7 cells. Additionally, evaluation based on IL-6 and iNOS expression levels confirmed the anti-inflammatory effects of the chosen components on LPS-induced RAW264.7 cells. Some of the reported results are as follows: (1) The impact of quercetin on RAW264.7 cells suggests that 20 µM quercetin significantly inhibits IL-6 expression [67]. (2) Experimental results on RAW264.7 cells indicate that 40 mg/L ethyl ferulate significantly suppresses iNOS levels [68].

Periodontitis is a chronic inflammatory disease occurring in the periodontal tissues, characterized by symptoms such as gingival redness and swelling, alveolar bone resorption, and tooth mobility. These symptoms align with the pathways we predicted. We chose to construct an integrated pathway involving the PI3K-AKT signaling pathway and the MAPK signaling pathway to elucidate the therapeutic mechanism of QWS in treating periodontitis. Increasing evidence suggests that these pathways are associated with the pathogenesis of periodontitis or potential therapeutic targets. The PI3K-Akt signaling pathway (hsa04151) plays a crucial role in bone formation and remodeling, regulating inflammatory bone resorption caused by periodontitis [69]. The MAPK signaling pathway (hsa04010) helps maintain mitochondrial homeostasis and suppresses inflammatory responses [70]. These findings support the relevance of the pathways we selected for understanding the therapeutic mechanisms of QWS in periodontitis treatment.

Network pharmacology is a crucial tool for analyzing the treatment of periodontitis with TCM, as demonstrated in previous studies. For instance, Cytoscape 3.7.1 was employed to construct and analyze the constituent-periodontitis target-pathway network of Asarum-Angelica, using degree, betweenness, and closeness as analysis metrics to identify the key target of Angelica sinensis in the treatment of periodontitis [71]. Similarly, a herbal medicine-compound-target interaction network was established, where degree values were utilized to assess the importance of nodes and to identify bioactive compounds and core targets in EMW for the treatment of periodontitis [49]. Compared with these studies, our computational pharmacology model we proposed for constructing the CES considers the connectivity of the network. Nodes with tighter connections enable more rapid information flow within the network. The model takes the connectivity and stability of nodes in the network to select key nodes. It assesses the degree of aggregation among nodes, where closer relationships between nodes suggest a higher likelihood of interaction and information sharing. Furthermore, the use of the knapsack algorithm further optimizes the selection of key components. We introduced a multi-objective optimization approach that takes into account node communication closeness, bridging capacity, and control over neighboring nodes to select the AECG that represents the original formulas. As a result, our model serves as a powerful tool for studying TCM compatibility and disease mechanisms. However, there are still some limitations in our study. First, the network pharmacology and computational modeling methods rely heavily on existing databases, which may not cover all the bioactive compounds or reflect the dynamic nature of biological systems. Second, we should consider more primary active components. Third, the current model does not incorporate individual differences or pharmacokinetics, which may affect the applicability of the findings in clinical practice. Therefore, in the future, we plan to validate our effective components and mechanisms for periodontitis treatment through in vivo and/or in vitro studies.

Conclusion

This study employed computational network pharmacology and molecular docking to explore the active components and potential targets of QWS in the treatment of periodontitis. A group of compounds collectively referred to as AECG was identified, potentially mediating anti-inflammatory effects through the PI3K-Akt and MAPK signaling pathways. The findings indicate that QWS may exert therapeutic effects via a multi-component, multi-target, and multi-pathway approach, providing a systematic perspective on its mechanism of action in periodontitis.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

This project thanks the Basic Medical College of Southern Medical University for providing experimental sites and technical guidance.

Abbreviations

- QWS

Qing-Wei-San

- CES

Core effect space

- SCI

Stacked contribution index

- AECG

Approximate equivalent component group

- TCM

Traditional Chinese medicine

- DG

Dang Gui

- HL

Huang Lian

- DH

Di Huang

- MDP

Mu-Dan-Pi

- SM

Sheng Ma

- WPI

Weighted protein-protein interactions

- C-T-T

Component-target-target

- GO

Gene Ontology

- KEGG

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

Author contributions

Conceptualization, XHY and GDG; Investigation, LYH, LWQ and LAP; Writing– Original Draft, LYH; Formal Analysis, CJX and LY; Funding Acquisition, XHY; Validation, CJQ, LYX, LJH, and CL.

Funding

This project was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province(2020A1515011453).

Data availability

The pathogenic genes associated with periodontitis data used in this study were sourced from the DisGeNET database (https://www.disgenet.org/).The chemical composition of QWS was derived from three natural medicinal plant databases: TCMSP(https://old.tcmsp-e.com/tcmsp.php), TCMID (http://www.megabionet.org/tcmid/), and TCM Database@Taiwan(https://tcm.cmu.edu.tw/).Subsequently, target identification was performed using online tools such as SEA(https://sea.bkslab.org/), HitPick(http://mips.helmholtz-muenchen.de/hitpick/), and SwissTargetPrediction(http://www.swisstargetprediction.ch/).

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Clinical trial number

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Yanhong Liu and Wenqi Li contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Daogang Guan, Email: guandg0929@smu.edu.cn.

Huiyong Xu, Email: xuhuiyong@i.smu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Tang Z, et al. The effect of antibiotics on the periodontal treatment of diabetic patients with periodontitis: A systematic review and Meta-Analysis. Front Pharmacol. 2023;14:1013958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Slots J. Periodontitis: facts, fallacies and the future. Periodontol 2000. 2017;75(1):7–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu H, et al. Effect of modified Qingweisan and Huangqin tablets for invasive periodontitis. Guid J Tradit Chin Med Pharm. 2020;11 vo 26:77–9. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mooney EC, et al. Quercetin preserves oral cavity health by mitigating inflammation and microbial dysbiosis. Front Immunol. 2021;12:774273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Inagaki Y, et al. Gan-Lu-Yin (Kanroin), traditional Chinese herbal extracts, reduces osteoclast differentiation in vitro and prevents alveolar bone resorption in rat experimental periodontitis. J Clin Med. 2021;10(3):386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xia Z, et al. Network pharmacology, molecular docking, and experimental Pharmacology explored Ermiao Wan protected against periodontitis via the PI3K/AKT and NF-Kappa B/MAPK signal pathways. J Ethnopharmacol. 2023;303:115900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huang J et al. Herbal Textual Research on Classical Prescription Qingwei Powder. Mod. Chin. Med. 2022, No. 06 vo 24, 1114–1121.

- 8.Sun X, et al. Effects of Qingwei powder and Yunv Decoction on inflammatory factors and extracellular matrix metalloproteinases in periodontitis rats. Chin J Geriatr Dent. 2021;19(05):286–90. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li X, et al. New application of psoralen and angelicin on periodontitis with Anti-Bacterial, Anti-Inflammatory, and osteogenesis effects. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2018;8:178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meng Y, UPLC-Q-TOF-MS, et al. GC-MS combined with network Pharmacology and molecular Docking technology to analyze the mechanism of Qingwei powder in treating periodontitis. China J Tradit Chin Med. 2022;47(10):2778–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yuan H, et al. How can synergism of traditional medicines benefit from network pharmacology?? Molecules. 2017;22(7):1135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Piñero J, et al. DisGeNET: A comprehensive platform integrating information on human Disease-Associated genes and variants. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45(D1):D833–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barrett T, et al. NCBI GEO: archive for functional genomics data Sets—Update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;41(D1):D991–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guan D, et al. CMGRN: A web server for constructing multilevel gene regulatory networks using ChIP-Seq and gene expression data. Bioinformatics. 2014;30(8):1190–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guan D, et al. PTHGRN: unraveling Post-Translational hierarchical gene regulatory networks using PPI, ChIP-Seq and gene expression data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42(W1):W130–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ru J, et al. TCMSP: A database of systems Pharmacology for drug discovery from herbal medicines. J Cheminformatics. 2014;6(1):13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xue R, et al. Traditional Chinese medicine integrative database for herb molecular mechanism analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;41(D1):D1089–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen CY-C. TCM database@taiwan: the world’s largest traditional Chinese medicine database for drug screening in Silico. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(1):e15939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Lipinski CA et al. Experimental and computational approaches to estimate solubility and permeability in drug discovery and development settings. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2001;46(1-3):3–26. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Lovering F, et al. Escape from flatland: increasing saturation as an approach to improving clinical success. J Med Chem. 2009;52:21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Muegge I et al. Simple selection criteria for Drug-like chemical matter. J Med Chem 2001; 44(12):1841–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Ali J et al. Revisiting the general solubility equation: in Silico prediction of aqueous solubility incorporating the effect of topographical Polar surface area. J Chem Inf Model. 2012;52(2):420–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Daina A et al. SwissADME: A free web tool to evaluate pharmacokinetics, Drug-Likeness and medicinal chemistry friendliness of small molecules. Sci Rep. 2017;7:42717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Abramson A et al. An ingestible Self-Orienting system for oral delivery of macromolecules. Science 2019;363(6427):611–615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Daina A, et al. SwissADME: A free web tool to evaluate pharmacokinetics, Drug-Likeness and medicinal chemistry friendliness of small molecules. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):42717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Keiser MJ, et al. Relating protein Pharmacology by ligand chemistry. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25(2):197–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu X, et al. HitPick: A web server for hit identification and target prediction of chemical screenings. Bioinformatics. 2013;29(15):1910–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Daina A, et al. SwissTargetPrediction: updated data and new features for efficient prediction of protein targets of small molecules. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47(W1):W357–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tang F, et al. The accurate prediction and characterization of Cancerlectin by a combined machine learning and GO analysis. Brief Bioinform. 2021;22(6):bbab227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kanehisa M, et al. KEGG for Taxonomy-Based analysis of pathways and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023;51(D1):D587–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huang Y, et al. System Pharmacology-Based determination of the functional components and mechanisms in chronic heart failure treatment: an example of Zhenwu Decoction. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2024;42(23):12935–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu Q, et al. Screening of the key response component groups and mechanism verification of Huangqi-Guizhi-Wuwu-Decoction in treating rheumatoid arthritis based on a novel computational Pharmacological model. BMC Complement Med Ther. 2024;24(1):4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen J et al. Molecularly imprinted macroporous hydrogel promotes bone regeneration via osteogenic induction and osteoclastic Inhibition. Adv Healthc Mater. 2024;13(23), e2400897. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Liu Q, et al. A novel network Pharmacology strategy to Decode mechanism of Wuling powder in treating liver cirrhosis. Chin Med. 2024;19(1):36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tanaka T, et al. IL-6 in inflammation, immunity, and disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2014;6(10):a016295–016295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Asehnoune K, et al. Involvement of reactive oxygen species in Toll-Like receptor 4-Dependent activation of NF-κB. J Immunol. 2004;172(4):2522–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li W, et al. Simultaneous determination of six alkaloids in coptidis Rhizoma by 2D - HPLC coupled with trapping column. Chin J Pharm Anal. 2014;34(4):654–8. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cai X. Simultaneous determination of three phenolic acids in Cimicifuga by HPLC. J China Prescr Drug. 2020;18(3):39–41. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang W, et al. Simultaneous determination of four constituents in rehmanniae Radix preparata by RP-HPLC under double-wave length. J Shenyang Pharm Univ. 2012;29(5):367–72. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yang R, et al. Determination and principal component analysis of nine components of Angelica sinensis from different origins. Tradit Chin Drug Res Clin Pharmacol. 2020;31(4):473–7. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yao Y, et al. HPLC analysis and study of the content determination of 7 components of Angelica sinensis in four producing areas in different treatments. Lishizhen Med Mater Med Res. 2022;33(8):1987–90. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xie J, et al. HPLC with UV switch determination of 6 indicative components in Moutan cortex. Chin J Exp Tradit Med Formulae. 2013;19(2):85–9. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nouri A et al. Ferulic acid exerts a protective effect against Cyclosporine-induced liver injury in rats via activation of the Nrf2/HO‐1 signaling, suppression of oxidative stress, inflammatory response, and halting the apoptotic cell death. J Biochem Mol Toxicol. 2023;37(10):e23427. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Khan HU, et al. Lauric acid ameliorates lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-Induced liver inflammation by mediating TLR4/MyD88 pathway in Sprague Dawley (SD) rats. Life Sci. 2021;265:118750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yasukawa Z, et al. Identification of an Inflammation-Inducible serum protein recognized by Anti-Disialic acid antibodies as carbonic anhydrase II. J Biochem (Tokyo). 2007;141(3):429–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]