Abstract

Background

Surgical site infection (SSI) is the most common complication post-caesarean section, causing risks such as antibiotic resistance, prolonged hospital stay, increased costs, maternal sepsis and even death. While SSI rates in India have declined by the initiative under the National Health Mission, they remain high in resource-constrained, tribal-dominant areas like Shahdol. This study estimates SSI incidence, identifies predictors, and analysed referral patterns at Medical College, Shahdol, India.

Methods

From May to July 2023, Pregnant women requiring caesarean section were invited to participate (estimated sample size: 224). They were followed until 30 days post- caesarean section or SSI development, whichever came earlier. The ‘event’ was the first SSI report, and ‘censoring’ included those without SSI or lost to follow-up. A heatmap visualized referral patterns by healthcare centers and duty hours for common caesarean section indications. Probability of SSI risk by different factors were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method, with survival curves compared via log-rank test. Adjusted hazard ratios were calculated using a multivariable Cox regression model.

Result

The SSI rate was 13.4%, with an incidence of 4.82 episodes per 1000 women-days. Significant predictors included caesarean section duration < 30 min (p = 0.03) and subcutaneous skin closure (p = 0.04). Pregnant women from Shahdol (aHR = 1.38), Umaria (aHR = 1.10), and other districts (aHR = 2.35) had higher SSI risk than those from Anuppur. Each additional minute in completion of caesarean section reduced SSI risk by 3% (aHR = 0.97; p = 0.045).

Conclusion

The high SSI incidence in this setting resulted from an erratic and largely irrational referral system, straining limited healthcare staff to perform disproportionately high caesarean section, especially at night, without adequate septic precautions. Strengthening infection control, post-operative surveillance, and community-based follow-up may significantly reduce SSI.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12884-025-07835-2.

Keywords: Risk of post caesarean section surgical site infection, Referral pattern, Resource constraint tertiary level health care Center, Tribal dominant setting, Kaplan Meier analysis

Introduction

Surgical site infection (SSI) is the most common complication following caesarean Sections [1, 2]. Typically, it occurs at the incision or operative site within the 30 days post-caesarean Sections [3]. In India, the reported incidence ranges from 3% to 10.3%, with superficial SSIs making up nearly two-thirds of cases [4–6]. SSIs may be acquired during hospital stay (nosocomial) due to factors like multiple referrals, poor aseptic practices, surgical site hygiene, or antimicrobial resistance, or after discharge (community-acquired) due to poor hygiene and cultural practices during the postpartum period [7, 8]. SSIs significantly increase hospital stays, healthcare costs, and strain on families and the healthcare delivery system [1, 2]. Recent evidence suggest that post-caesarean section SSIs have much greater impact on maternal deaths, than previously believed [9], suggesting that settings with high maternal mortality likely to have high burden of SSI rate as well.

Total 70% maternal mortality of India is contributed by the Empowered Action Group states like Madhya Pradesh (MP), despite the focussed and setting specific initiatives taken under the umbrella of National Health Mission (NHM) in last couple of decades to reduce the Maternal mortality [10]. Shahdol division of MP reports the highest maternal mortality ratio at a staggering 361, compared to the state average of 221, making it one of the highest in the country [11]. About 60% these deaths take place during post-partum period and SSI is main contributor of this [12]. There is obvious reasons to believe that delivery points in Shahdol division also have a higher SSI rate than the state.

In recent decades, India has made significant strides in reducing post-caesarean section SSIs through various interventions under the NHM [7]. The NHM has focused on improving the quality of maternal care by promoting best practices in surgical hygiene, infection control protocols, and preoperative antibiotic prophylaxis in both public and private healthcare settings through the Labour Room Quality Improvement (LAQSHY) Initiatives [13, 14]. Training healthcare professionals, enhancing infrastructure, and ensuring access to essential medicines have been key components of the strategy [7]. Additionally, guidelines for infection prevention and the implementation of regular surveillance of surgical outcomes have contributed to better monitoring and reduced post-caesarean section SSI rates [15]. These efforts align with the World Health Organization's global strategy for safe surgery and maternal health [16].

The LAQSHYA program lacks a robust methodology and an organized system to track all post-caesarean women for SSIs over the full 30-day period. No study in the state has reported this burden. This is largely due to the difficulty of tracking women in the community after hospital discharge. This study aimed to estimate SSI incidence, identify predictors, and analyse referral patterns at Birsa Munda Government Medical College (BMGMC) hospital. Considering Shahdol division’s high maternal mortality and limited resources, the findings highlight key demographic, surgical, and programmatic factors to reduce post-caesarean section SSI rates and related complications [11]. This might help the programme managers in setting health system priority and resource allocation in order to improve maternal health in Shahdol division, M.P.

Methods

Setting

Scheduled Tribe (ST) population in India, primarily residing in remote and forested regions, face significant socio-economic disadvantages i.e. high poverty (40.6%), low literacy (59%), and poor access to healthcare [17]. In MP, which has the largest ST population (approximately15 million), these challenges are even more pronounced, with ST literacy at 50.6% and over half living below the poverty line. Maternal health indicators among ST women lag behind the national average i.e. only 60.3% opt for institutional deliveries and just 54.5% receive full antenatal care. Healthcare infrastructure in tribal areas remains constrained, with major shortages of obstetricians (83%) and medical officers (21%) [18].

Shahdol division is located in eastern MP comprising Shahdol, Anuppur, and Umaria districts. It has nearly half of its 2.45 million population from ST population. The overall literacy rate in the division is 65% which is below the state average [19–21]. The public healthcare delivery system of division includes three district hospitals (DH) and one tertiary care center, Birsa Munda Government Medical College (BMGMC), established in 2020. BMGMC offers 24/7 emergency obstetric care as per national guidelines [12, 22] but lacks key diagnostic tools like ultrasonography, Computed Tomography Scan and culture and sensitivity test of biological samples limiting its ability to distinguish between superficial and deep SSI. Therefore, the study focused only on superficial SSI cases.

Recruitment of participants

Pregnant women admitted to the Obstetric department and indicated for Caesarean section as determined by the department faculty, were invited to participate. Those who did not consent or from whom consent could not be obtained before Caesarean section were excluded. Recruitment was completed before Caesarean section was performed.

Study type and period

This prospective cohort study included pregnant women admitted to BMGMC for Caesarean section between May and July 2023 or until the sample size was achieved (whichever is earlier).

Sample size sampling method

For the estimation of Incidence rate of SSI, the sample size was determined by considering the single population proportion 10.3%, obtained from a previous study published from India, with 95% confidence level, 5% margin of error the sample size obtained was 142.

For the second objective the sample size, n, was estimated as n = e/p. Here,  denotes the cumulative incidence of SSI Post Caesarean section. An estimate of

denotes the cumulative incidence of SSI Post Caesarean section. An estimate of  is 0.06 which based on a pilot study conducted by the investigators. The required number of events,

is 0.06 which based on a pilot study conducted by the investigators. The required number of events,  , is given as

, is given as

Here  is the two tailed significance level taken to be 0.05 and

is the two tailed significance level taken to be 0.05 and  is the power taken to be 0.80. HR is the hazard ratio taken to be 2.2. These considerations amount to a sample size of 210. Hence, maximum sample size (210) was considered for the study however, due to operational reasons consecutive 224 pregnant women were recruited in the study.

is the power taken to be 0.80. HR is the hazard ratio taken to be 2.2. These considerations amount to a sample size of 210. Hence, maximum sample size (210) was considered for the study however, due to operational reasons consecutive 224 pregnant women were recruited in the study.

Data collection method and schedule

Information was collected using a mobile-based application, Epicollect5 [23]. The questionnaire was administered in the local language, Hindi, to reduce inter-observer bias. After enrollment into the study, baseline information was collected from each pregnant woman, followed by three scheduled follow-ups.

Baseline information was obtained through a one-on-one interview conducted before the caesarean section. The first follow-up (Day 0) was conducted on same day preferably, immediately after the caesarean section through a review of medical records. The second follow-up (Day 5) occurred at the time of discharge, using a combination of one-on-one interviews and record reviews. The third follow-up was conducted on Day 30 post- caesarean section or earlier, if a SSI was reported. This follow-up was done either through an in-person interview (if the woman returned to the BMGMC) or via a telephone call.

Interviews were conducted either with the woman herself or with a family member. For record reviews, sources included admission papers and surgical notes. At the time of discharge, women were educated about the symptoms of SSI and instructed to either return to the BMGMC or contact the medical team by phone if symptoms developed [1].

Development of SSI were confirmed in one of three ways: through physical examination by a faculty of BMGMC, written documentation from a private practitioner, or, when neither was possible, a telephonic assessment conducted by a faculty member based on the woman’s medical history and reported symptoms [1].

Variables

The operational definition of superficial SSI for this study was involvement of the skin and subcutaneous tissue at the surgical site, accompanied by at least one of the following indicators i.) purulent discharge, ii.) isolation of organisms from the fluid or tissue of the superficial incision, or iii.) the presence of at least one sign of inflammation such as pain, fever, localized swelling, induration, wound dehiscence, changes in the overlying skin, or exudative purulent discharge. Additionally, wounds that were intentionally opened by the surgeon for drainage or wounds declared infected by the surgeon were also considered as cases of SSI [3]. The ‘event’ was defined as first day of reporting of SSI. The follow-up period (days after caesarean section) was defined considering day of caesarean section as zero day and thereafter 30 days. ‘Censoring’ was defined as women not developed SSI, and those lost follow up due to any reason.

The indications of referrals for caesarean section were classified in four groups. First was Emergency; Antepartum Haemorrhage (APH), Foetal distress, Obstructed labour, Meconium aspirate and Severe Anaemia. The second group was Clinical or Obstetric; Cephalopelvic Disproportion (CPD), Malpresentation, Intrauterine Growth Restriction (IUGR), Oligohydramnios and Multiple gestation. The third group was Pre-existing Medical or Pregnancy-related Complications which includes Medical disorders, Pregnancy-Induced Hypertension, Post-dated pregnancy, Pre-term labour and Premature Rupture of Membranes (PROM). The last group was Non-Medical or Administrative Reasons which includes Non-availability of anaesthetist or gynaecologist or both, referral on-demand of pregnant women, Other (miscellaneous and unknown reasons), Previous caesarean section and Prolong labour [24].

Analysis

Data was extracted in excel file from epicollect5 and analyse using R software package and R Studio Version 1.3.1093© 2009–2020 RStudio, PBC. The codes of analysis were saved in R markdown file.(Supplementary material 2) Key analytic output was the ‘incidence rate of SSI’ calculated as number of SSI episodes per 1000 women-days. Incidence rate of SSI was also calculated as number of SSI episodes per 30 women-days.

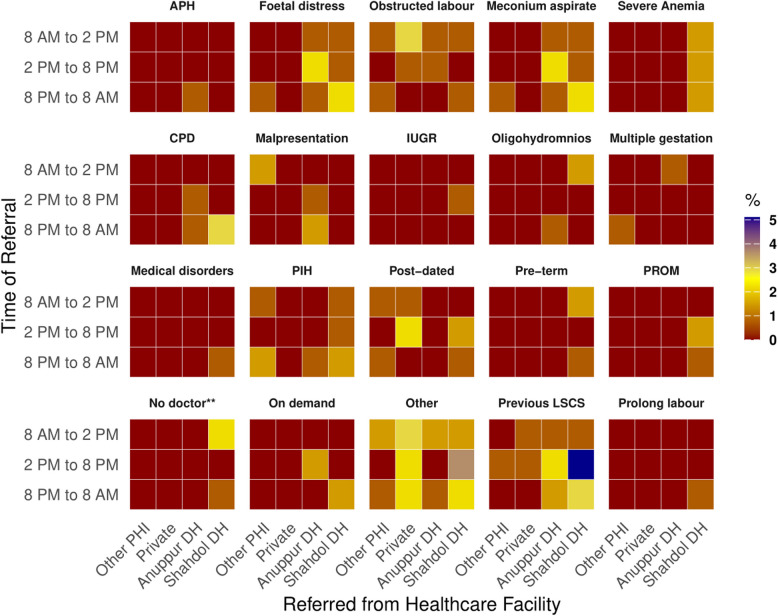

The number of days post- post-caesarean section remain ‘event free’ i.e. without SSI, was taken in account to considered as cumulative follow up and was calculated as women-days.

Categorical variables were analysed using frequency tables, while continuous variables were summarized with medians and interquartile ranges (IQR). A heatmap was created to visualize referral patterns across healthcare centers and duty hours for common and plausible conditions. To enhance interpretation, indications were grouped and displayed in individual rows of the plot. Each grid in the heatmap represents the proportion of referrals for a specific indication, based on the healthcare centre and the doctor's duty. A blue grid indicates a 5% referral proportion, yellow represents 3%, and red signifies 0% in the respective scenario.

SSI was estimated using the Kaplan–Meier (KM) method, and survival curves were compared across relevant categorical variables using the log-rank test. As it was an obvious statistical tool to determine the day when SSIs developed post-caesarean section, as timing has important implications for prevention, treatment, and incurred expenditure on its management.

The proportional hazards assumption for the Cox proportional hazards model was evaluated through graphical inspection and the Schoenfeld residuals test. Variables with p-values less than 0.2 in the bivariable analysis were considered for inclusion in the multivariable Cox regression model. The model's goodness-of-fit was assessed using the Martingale test. Predictors with multicollinearity were excluded, and the final model reported adjusted hazard ratios (aHR) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) to quantify the strength of associations between SSI and potential predictors. Statistical significance was set at a p-value less than 0.05.

Ethical consideration

An approval from Institutional Ethics and review committee, Birsa Munda Government Medical College Shahdol was obtained. Written informed consent to participate in the study and for publication of information was obtained from each pregnant woman prior to her enrollment in the study. Although participants were followed up multiple times, consent was obtained only once i.e. at the time of recruitment. All efforts were made to ensure the confidentiality and privacy of the participants throughout the study. This study adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Result

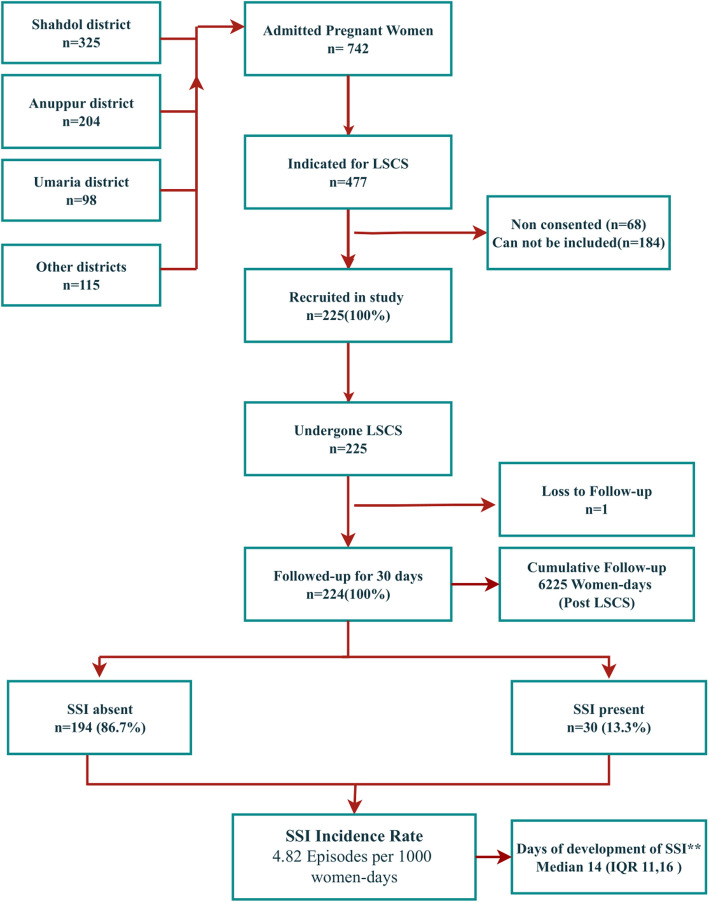

During the study, 742 pregnant women were admitted, with 477 (64%) indicated for caesarean section. Of these, 252 were excluded due to lack of consent or operational constraints. Among 225 recruited women, one was lost to follow-up, leaving 224 for analysis. SSI developed in 30 women (13.3%) over 6,225 post- caesarean section days, with an SSI incidence rate of 4.82 episodes per 1000 women-days or 0.14 episodes per 30 women-days. The median time to develop SSI post- caesarean section was 14 days (IQR 11,16). (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flowchart depicting the flow of the study participants from recruitment to development of Surgical Site Infection post-caesarean section at Birsa Munda Government Medical College Shahdol Madhya Pradesh (India) 2023. Footnote: LSCS: Lower section Caesarean section, Other districts: It includes pregnant women coming from neighbouring area of Chhattisgarh state, Can not be included: due to operational reasons, SSI: Surgical Site Infection. ** Among pregnant woman who developed SSI post-caesarean section

A total of 122 pregnant women were self-referred, while 102 were referred by healthcare facilities for diverse indications. i) Emergency indications included meconium aspirate, obstructed labour, and foetal distress (3% each). Severe anaemia referrals (6%) were exclusively from Shahdol DH, and APH referrals (2%) were from Anuppur DH during night hours. ii) Clinical indications included CPD (3%) and malpresentation (2%), predominantly from Shahdol and Anuppur DH during night hours. Oligohydramnios referrals (2%) came mostly from Shahdol DH. iii) Medical complications included post-dated pregnancy (3%), with most referrals from private centers. PIH referrals (2%) came from PHIs, while pre-term labour, medical disorders, and PROM referrals originated from Shahdol DH. iv) Non-medical reasons such as previous caesarean Sect. (5%) and administrative issues led to 3–4% of referrals across centers. (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Heat map depicting the indication-wise referral for caesarean section from different health care facilities across the duty hours to the Birsa Munda Government Medical College Shahdol Madhya Pradesh (India) 2023. Footnote; APH: Antepartum haemorrhage, IUGR: Intra uterine growth retardation, CPD: Cephalopelvic disproportion, PROM: Premature rupture of membrane, PIH: Pregnancy induced hypertension, LSCS: lower section Caesarean section, Severe anaemia: Haemoglobin less than 7, No doctor**: Either Gynaecologist or Anaesthetist or both were unavailable

Univariate analysis showed that referral centers, caesarean section duration, and antibiotic use within a week of caesarean section were significant predictors of SSI (p < 0.05) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic, clinical and healthcare facility related factors associated with the Surgical Site Infection post-caesarean section at Birsa Munda Government Medical College Shahdol Madhya Pradesh (India) 2023

| Characteristic | N |

Overall, N= 2241 |

SSI | p-value2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Absent, N= 1941 |

Present, N= 301 |

||||

| Age | 224 | 26[23,28] | 26[23,28] | 26[24,28] | 0.5 |

| Below poverty line | 224 | 132 (59%) | 109(56%) | 23 (77%) | 0.10 |

| Education status | 224 | 0.3 | |||

| Illiterate | 29 (13%) | 27 (14%) | 2 (6.7%) | ||

| Up to High School | 13 (5.8%) | 12 (6.2%) | 1 (3.3%) | ||

| Above High School | 180 (80%) | 154(79%) | 26 (87%) | ||

| Unknown | 2 (0.9%) | 1 (0.5%) | 1 (3.3%) | ||

| District | 224 | 0.7 | |||

| Shahdol | 105 (47%) | 90 (46%) | 15 (50%) | ||

| Anuppur | 66 (29%) | 59 (30%) | 7 (23%) | ||

| Umaria | 28 (13%) | 25 (13%) | 3 (10%) | ||

| Other districts of MP | 11 (4.9%) | 9 (4.6%) | 2 (6.7%) | ||

| Districts of CG | 14 (6.3%) | 11 (5.7%) | 3 (10%) | ||

| Schedule tribe | 224 | 31 (14%) | 28 (14%) | 3 (10%) | 0.3 |

| Rural residence | 222 | 180 (81%) | 152(79%) | 28 (93%) | |

| Referred by | 224 | 0.022 | |||

| Other PHI$ | 13 (5.8%) | 8 (4.1%) | 5 (17%) | ||

| Anuppur DH$$ | 23 (10%) | 21 (11%) | 2 (6.7%) | ||

| Shahdol DH$$ | 45 (20%) | 41 (21%) | 4 (13%) | ||

| Self-referral | 122 (54%) | 103(53%) | 19 (63%) | ||

| Private | 21 (9.4%) | 21 (11%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| Referral time | 104 | > 0.9 | |||

| 2 pm to 8 pm | 34 (33%) | 31 (33%) | 3 (27%) | ||

| 8 am to 2 pm | 33 (32%) | 29 (31%) | 4 (36%) | ||

| 8 pm to 8 am | 37 (36%) | 33 (35%) | 4 (36%) | ||

| Blood transfusion | 219 | 34 (16%) | 32 (17%) | 2 (6.9%) | 0.4 |

| Hypertension | 223 | 15 (6.7%) | 15 (7.8%) | 0 (0%) | 0.3 |

| DM | 219 | 3 (1.4%) | 3 (1.6%) | 0 (0%) | > 0.9 |

| H/O of Ab one week prior to LSCS | 217 | 69 (32%) | 66 (35%) | 3 (10%) | 0.009 |

| Sickle cell disease | 222 | 10 (4.5%) | 9 (4.7%) | 1 (3.3%) | > 0.9 |

| Thalassemia | 220 | 1 (0.5%) | 1 (0.5%) | 0 (0%) | > 0.9 |

| Hb level | 223 | 11[10,12] | 11[10,12] | 11[10,12] | 0.4 |

| H/O respiratory disease | 224 | 2 (0.9%) | 1 (0.5%) | 1 (3.3%) | 0.13 |

| BMI | 223 | 24.8 [22.5,28.1] | 24.6 [22.5,27.8] | 24.9 [22.8,28.1] | 0.7 |

| Prophylactic Ab dose | 222 | 221(100%) | 191(99%) | 30(100%) | > 0.9 |

| Surgery type | 222 | 0.8 | |||

| Elective | 24 (11%) | 22 (11%) | 2 (6.7%) | ||

| Emergency | 198 (89%) | 170(89%) | 28 (93%) | ||

| Duty shift of doctor | 223 | 0.2 | |||

| Evening | 72 (32%) | 66 (34%) | 6 (20%) | ||

| Morning | 67 (30%) | 58 (30%) | 9 (30%) | ||

| Night | 84 (38%) | 69 (36%) | 15 (50%) | ||

| Inserted OT drain | 224 | 1 (0.4%) | 1 (0.5%) | 0 (0%) | > 0.9 |

| Skin closure technique | 224 | 0.055 | |||

| Interrupted mattress sutures | 88 (39%) | 81 (42%) | 7 (23%) | ||

| Sub cutaneous suture | 136 (61%) | 113(58%) | 23 (77%) | ||

| Duration of caesarean section (min) | 224 | 42 [35,50] | 43 [35,51] | 36[30,42] | 0.006 |

| Surgical wound | 223 | 0.4 | |||

| Clean | 4 (1.8%) | 3 (1.6%) | 1 (3.3%) | ||

| Clean/contaminated | 219 (98%) | 190(98%) | 29 (97%) | ||

| Days for Ab after caesarean section | 224 | 3[3,5] | 3[3,4] | 3[3,5] | 0.11 |

| Post-caesarean section Folley’s removal | 224 | 0.078 | |||

| After 48 h | 123 (55%) | 111(57%) | 12 (40%) | ||

| Within 48 h | 101 (45%) | 83 (43%) | 18 (60%) |

MP Madhya Pradesh, $ PHI Public Health Institution including all Public delivery points i.e. Primary Health Centers, Community health centres and other district hospitals i.e. Umaria, Janakpur etc., $$DH District hospital, H/O History of, LSCS Lower section Cesarina section, DM Diabetes Mellitus, OT Operation theatre, SSI Superficial surgical site infection, Ab Antibiotics, Hb Haemoglobin, Min Minutes, BMI Body Mass Index

1 Median [Q1,Q3]; n (%)

2 Wilcoxon rank sum test; Pearson’s Chi-squared test; Fisher’s exact test

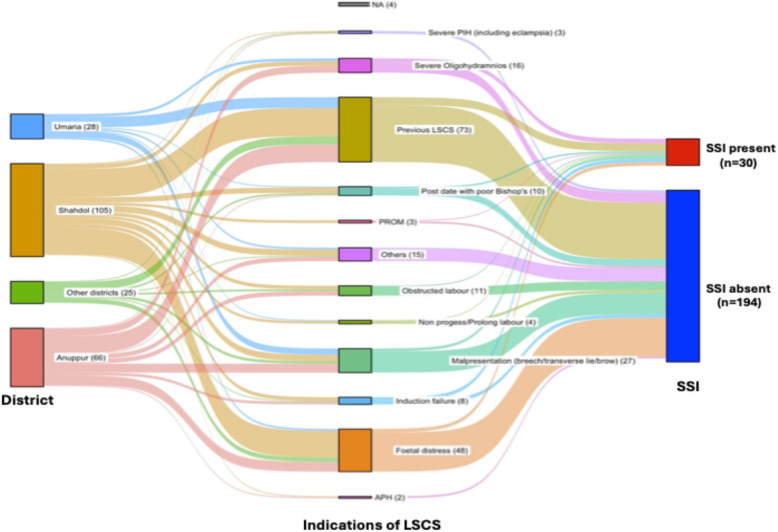

The Sankey plot revealed that 47% of Pregnant women were from Shahdol district, followed by Anuppur (29%), Umaria (13%), and other districts (11%). The most common indications for caesarean section were previous caesarean Sect. (33%), foetal distress (21%), and malpresentation (12%). Among women with SSI, previous caesarean section, severe oligohydramnios, and foetal distress were the leading indications (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Sankey plot depicting residence district of pregnant women, indication of caesarean section and Surgical Site Infection as respective three nodes for pregnant women undergone Caesarean section at Birsa Munda Government Medical College Shahdol Madhya Pradesh (India) 2023. Footnote: NA: Indication of LSCS was not mentioned, APH: Antepartum haemorrhage, IUGR: Intra uterine growth retardation, CPD: Cephalopelvic disproportion, PROM: Premature rupture of membrane, PIH: Pregnancy induced hypertension, LSCS: lower section Caesarean section, Severe anaemia: Haemoglobin less than seven,

Kaplan–Meier survival analysis showed declining SSI survival probability over 30 days post- caesarean section. By day 30, survival probability was lowest for pregnant women from other districts (80%) and highest for Umaria and Anuppur (91%), but differences were not significant (p = 0.63). Socioeconomic, geographic, and procedural factors (e.g., rural residence, emergency caesarean section, night procedures) showed varying survival probabilities, with skin closure technique (p = 0.04) and duration of surgery (p = 0.03) being statistically significant predictors (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Kaplan Meier plots with respective log rank test of plausible demographic, clinical and healthcare facility related predictors of Surgical Site Infection post-caesarean section at Birsa Munda Government Medical College Shahdol Madhya Pradesh (India) 2023. Footnote: LSCS: Lower section Cesarina section, OT: Operation theatre, SSI: Superficial surgical site infection, Ab: Antibiotics, Hb: Haemoglobin, Min: Minutes, ST: Schedule Tribe, DH: District hospital, OT: Operation theatre, ASA: American Society of Anaesthesiologists

The Cox-proportional hazard model provided key insights. Pregnant women from Shahdol (aHR = 1.38), Umaria (aHR = 1.10), and other districts (aHR = 2.35) had a higher risk of SSI compared to those from Anuppur, though these results were not statistically significant (p > 0.05). Caesarean section duration showed that each additional minute of surgery reduced the risk of SSI by 3% (aHR = 0.97; p = 0.045). Regarding the skin closure technique, subcutaneous closure was associated with more than double the risk of SSI compared to interrupted mattress closure (aHR = 2.20), but was not found statistically significant (p = 0.070). The model demonstrated moderate predictive ability, with a concordance value of 0.67 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Adjusted Hazard Ratio of Predictors of Post- post-caesarean section Surgical Site Infection among pregnant women attending Birsa Munda Government Medical College Shahdol Madhya Pradesh (India) 2023

| Predictor | aHR1 | 95%CI1 | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| District | |||

| Anuppur | - | - | - |

| Shahdol | 1.38 | 0.56, 3.39 | 0.5 |

| Umaria | 1.10 | 0.28, 4.26 | 0.9 |

| Other district | 2.35 | 0.74, 7.48 | 0.15 |

| OT duration in minutes | 0.97 | 0.94, 1.00 | 0.045 |

| Skin closure technique | |||

| Interrupted mattress | - | - | - |

| Sub cutaneous | 2.20 | 0.94, 5.18 | 0.070 |

1 aHR: Adjusted Hazard ratio calculated by Cox-proportional Hazard model, CI: Confidence Interval, Concordance of the model is 0.67

Discussion

Key findings

The study found a post-caesarean SSI incidence rate of 4.82 episodes per 1,000 women-days. Two factors were significantly associated with increased SSI risk; shorter duration of caesarean section and referrals from public health institutions other than district hospitals, or self-referrals.

Pregnant women were referred for caesarean sections due to a range of medical, obstetric, and administrative reasons. Shahdol DH referred women at all hours for severe anaemia, while conditions like meconium aspiration, APH, and foetal distress were usually referred during emergency hours. CPD was the most common obstetric reason for emergency referrals, and medical conditions such as pregnancy-induced hypertension, post-dated pregnancy, and preterm labor triggered referrals throughout the day. Administrative reasons like a history of previous caesarean section and patient demand also led to referrals, often during emergency hours. Referrals during routine hours occurred at times due to the unavailability of specialists by Shahdol DH. Most referrals came from Shahdol and Anuppur district hospitals, with the most common indications for caesarean section being previous caesarean section, foetal distress, malpresentation, and severe oligohydramnios.

Among women who developed SSI, the leading indication for caesarean section was previous caesarean section, followed by severe oligohydramnios. The 30-day follow-up revealed a significantly higher risk of SSI among women whose wounds were closed using subcutaneous sutures and whose caesarean section lasted less than 30 min, with the risk becoming more pronounced after 15 days post-operation.

Implications

As anticipated, the SSI rate in present study was 13.4% which is higher in comparison to the fully-functional and resource dense urban settings of India where it was reported from 5.63% to 10.3% [6, 25]. This higher SSI rate might be due to a disproportionately high number of emergency referrals, often during emergency-hours when faculty and residents are limited in number. As a result, adherence to aseptic protocols may be compromised by less experienced staff. Additionally, some women may have been referred multiple times between facilities due to non-operational delivery points or staff shortages, leading to delays. By the time they reached BMGMC, many required urgent caesarean sections, further limiting time for standard aseptic precautions.

The incidence rate of SSI in present study was 4.82 episodes per 1000 women-days. Present study also estimated the incidence rate of SSI as 0.14 episodes per 30 women-days, considering post-caesarean section. 30 women-days as denominator. As measuring the SSI in 1000 women-days may deflate the findings and anyway a women potentially remain susceptible to SSI only for 30 days hence investigators argue that it might be potentially and plausibly a better indicator for the estimation SSI [26].

Studies from Africa having similar setting reported variable incidence rate i.e. 3.75 to 11.7 episodes per 1000 woman-days [26, 27]. Considering maternal mortality in these African countries are very much comparable to the Shahdol division, these variations can be attributed to factors like population characteristics, including prevalence of comorbid conditions like anaemia including sickle cell anaemia of that period, which is very common in study setting, likely play a role in determining SSI rates [28, 29].

The study found a higher risk of SSI among women who underwent subcutaneous skin closure and whose caesarean sections lasted less than 30 min. This may be attributed to the technical demands of subcutaneous closure, which require expertise as reported in few studies [30, 31]. Inexperienced faculty and residents, under pressure to complete surgeries quickly due to a backlog of cases, may have compromised technique, increasing the risk of infection.

BMGMC is a relatively new tertiary healthcare facility operating in a resource-constrained setting, faces challenges such as limited staffing experience and a disproportionately high number of caesarean sections. These factors may contribute to inconsistent peri-operative practices, including variations in the use of prophylactic antibiotics, adherence to aseptic techniques, and timing of skin closure. Additionally, post-discharge surveillance for SSI is often limited or inconsistent in such settings, potentially leading to underreporting or misclassification of SSI cases [32, 33].

The erratic and largely irrational referral pattern especially evening and night hours from the district hospitals to the BMGMC hospital need to be streamlined. For instance, the severe anaemia in pregnant women is an emergency and many times need blood transfusion as per national guidelines [34]. Most of these cases were referred to the BMGMC hospital during evening and night hours despite unavailability of blood bank in the hospital threatens the successful outcome of pregnancy. Similarly, the combination of few available faculties and high number of referrals for the conditions like Meconium aspirate, Foetal distress and PROM has high referrals during night hours which required immediate surgical intervention leads to too many impending surgeries in emergency hours. It might have contributed to SSI among pregnant women. The SSI during and after 15 days of LSCS need to explore the socio-cultural factors and treat the anaemia as per the national guideline [34].

Reducing SSI post-LSCS in resource-constrained settings always requires a multiprong approach that may addresses pre-operative, intra-operative, and post-operative factors i.e. meticulous hand hygiene, proper surgical site preparation with chlorhexidine-alcohol, and timely administration of prophylactic antibiotics [35, 36]. Study from India has emphasize the need for aseptic surgical precautions particularly in rural and low-resource hospitals where these practices are often inconsistent [37]. The investigators argue that in addition to these factors, judicious and coordinated referral mechanism may play a crucial role in reduction on SSI burden in these setting. The peripheral health institutes need to prioritise the referrals for caesarean section especially in evening and night hours for the cases like severe anaemia, previous caesarean section, CPD, malpresentation, no-doctor and malpresentation. Ideally, it has to be the part of microplanning of delivery of pregnant women as per the national Guidelines for Antenatal Care [22].

In addition, post-operative infection surveillance is critical in reducing SSIs, with studies showing that regular wound assessments and patient education on hygiene and wound care can significantly lower infection rates [35]. In resource-constrained settings, community health workers can play a vital role in follow-up care and early identification of infections. Study from rural central India has documented that good infrastructure, proper asepsis and antisepsis protocols, dedicated and skilled surgical team and enhanced awareness. may reduce the SSI to substantial number even in a rural hospital [38]. Together, these strategies underscore the importance of system-level improvements, clinical training, and patient-cantered care in reducing SSI rates post-caesarean section.

Limitations

Despite of robust methodology and first of its kind in central India the study has some conspicuous limitations; i.) it exclusively measured superficial SSI, missing deep SSI due to resource constraints. ii.) socio-cultural or health system factors contributing to SSI post-discharge were not assessed, iii.) the antibiogram of SSI cases could not be studied, limiting insights into antimicrobial resistance patterns and difference between nosocomial and community acquired SSI, iv.) Furthermore, the number of vaginal examinations performed on pregnant women prior to caesarean section, a potential predictor of SSI, was not included in the analysis.

Recommendations

The study recommends improving the referral system for pregnant women, ensuring adherence to aseptic protocols, promoting evidence-based surgical practices among healthcare staff, and implementing standardized SSI monitoring under the LAQSHYA programme. Specifically, it advises at least one post-operative check-up within 15 days. It also highlights the need for equitable distribution of healthcare personnel in tribal-dominated areas like Shahdol to ensure timely and quality maternal care. Future study should assess the antibiogram for post-caesarean section SSI to guide treatment and distinguish between hospital and community acquired infections. Additionally, it should explore the full referral pathway; from community to postpartum to better understand its causes and impact in present setting.

Conclusion

This study underscores the burden of superficial SSI post-caesarean section in a resource-constrained, tribal-dominated setting. With an SSI rate of 13.4% and incidence rate of 4.82 episodes per 1000 women-days. The notable predictors such as duration of caesarean section and skin closure techniques, and post-operative care are critical. Streamlining referral patterns, particularly during evening and night hours, and improving emergency preparedness can mitigate SSI risks. Enhanced infection control measures, consistent with post-operative surveillance, and community-based follow-up mechanisms can significantly reduce SSIs, improve maternal health outcomes, and contribute to achieving safer deliveries in similar low-resource settings.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The investigators extend their sincere gratitude to the Senior and Junior Residents of the Department of Obstetrics for their valuable support. They also express their appreciation to the nursing and paramedical staff of the department for their assistance. Additionally, they are deeply grateful to Dr. Milind Shiralkar, Dean of the institute, for his encouragement and support, which contributed to the successful completion of this study, aimed at enhancing the quality of maternal health services at the institute.

Clinical trial number

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- aHR

Adjusted hazard ratio

- APH

Antepartum Haemorrhage

- BMGMC

Birsa Munda Government Medical College

- CI

Confidence intervals

- CPD

Cephalopelvic Disproportion

- DH

District Hospital

- IQR

Interquartile range

- IUGR

Intrauterine Growth Restriction

- KM

Kaplan-Meier Method

- LAQSHY

Labour Room Quality Improvement

- MP

Madhya Pradesh

- NHM

National Health Mission

- PROM

Premature Rupture of Membranes

- SSI

Surgical site infection

- ST

Scheduled Tribe

Authors’ contributions

SS: Conception, design of the work, interpretation of data and approved the submitted version NJ: Conception, design of the work, interpretation of data and approved the submitted version SSP: Conception, design of the work, interpretation of data and approved the submitted version ARS: Conception, design of the work, interpretation of data and approved the submitted version, acquisition, analysis, interpretation of data, creation of new software used in the work, drafted the work and substantively revised it. SB: Acquisition, analysis, interpretation of data, and approved the submitted version, approved the submitted version VK: Conception, design of the work, interpretation of data and approved the submitted version NS: Conception, design of the work, interpretation of data and approved the submitted version.

Funding

Not applicable.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript as supplementary file's'and'g'and analysis codes are provided as''ssi"rmd file.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

An approval from Institutional Ethics and review committee, Birsa Munda Government Medical College Shahdol was obtained. Written informed consent to participate in the study and for publication of information was obtained from each pregnant woman prior to her enrollment in the study. Although participants were followed up multiple times, consent was obtained only once at the time of recruitment. All efforts were made to ensure the confidentiality and privacy of the participants throughout the study. This study adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from each participant to publish their personal details in this study.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Sona Singh and Akash Ranjan Singh contributed equally as joint first authors of this paper.

References

- 1.Global guidelines for the prevention of surgical site infection. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241550475. Accessed May 10, 2025.

- 2.Berriós-Torres SI, Umscheid CA, Bratzler DW, et al. Centers for disease control and prevention guideline for the prevention of surgical site infection, 2017. JAMA Surg. 2024;152(8):784–91. 10.1001/JAMASURG.2017.0904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Horan TC, Gaynes RP, Martone WJ, Jarvis WR, Grace Emori T. CDC definitions of nosocomial surgical site infections,1992: a modification of CDC definitions of surgical wound infections. Am J Infect Control. 1992;20(5):271–4. 10.1016/S0196-6553(05)80201-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prajapati V, Modi KP. Study of surgical site infection in patients undergoing caesarean section at tertiary care center, Gujarat. Int J Reprod Contracept Obstet Gynecol. 2022;11(3):844–8. 10.18203/2320-1770.IJRCOG20220567. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Junnare K, Kalra K, Mhaske G, Vadehra P. Study of surgical site infection (SSI) in patients undergoing caesarean section (CS): A retrospective study. International Journal of Clinical Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2020;350(1):28–39. 10.33545/gynae.2020.v4.i1f.483. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gupta S, Manchanda V, Sachdev P, Kumar Saini R, Joy M. Study of incidence and risk factors of surgical site infections in lower segment caesarean section cases of tertiary care hospital of north India. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2021;39(1):1–5. 10.1016/J.IJMMB.2020.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization India. National Guidelines for Infection Prevention and Control in Healthcare Facilities. New Delhi; 2020. https://ncdc.mohfw.gov.in/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/National-Guidelines-for-IPC-in-HCF-final1.pdf. Accessed 12 Jan 2025.

- 8.Hajira S, Korbu J. Analysis of the incidence and risk factors for surgical site infection following caesarean section in a tertiary healthcare centre. Int J Reprod Contracept Obstet Gynecol. 2024;13(9):2477–82. 10.18203/2320-1770.IJRCOG20242502. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bonet M, Brizuela V, Abalos E, et al. Frequency and management of maternal infection in health facilities in 52 countries (GLOSS): a 1-week inception cohort study. Lancet Glob Health. 2020;8(5):e661–71. 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30109-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.India Annual Health Survey 2012–2013. Office of the Registrar General and Census Commissioner (India). https://ghdx.healthdata.org/record/india-annual-health-survey-2012-2013. Accessed 12 Jan 2025.

- 11.India Health Action Trust. Maternal and Neonatal Health in Madhya Pradesh: Trends, Insights and Scope - India Health Action Trust (IHAT). IHAT. https://www.ihat.in/resources/mnh-in-madhya-pradesh-trends-insights-and-scope/. Published 2017. Accessed 12 Jan 2025.

- 12.World Health Organization (WHO). Managing Complications in Pregnancy and Childbirth: A Guide for Midwives and Doctors, Second Edition. Geneva; 2017.

- 13.National Health Mission (NHM). Labour Room Quality Improvement Initiative. New Delhi; 2017. https://nhm.gov.in/New_Updates_2018/NHM_Components/RMNCH_MH_Guidelines/LaQshya-Guidelines.pdf. Accessed 12 Jan 2025.

- 14.Seidelman JL, Mantyh CR, Anderson DJ. Surgical site infection prevention: a review. JAMA. 2023;329(3):244–52. 10.1001/JAMA.2022.24075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Health Organization (WHO). Protocol for surgical site infection surveillance with a focus on settings with limited resources. World Health Organization (WHO). https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/protocol-for-surgical-site-infection-surveillance-with-a-focus-on-settings-with-limited-resources. Published March 31, 2019. Accessed 12 Jan 2025.

- 16.World Health Organization (WHO). WHO Guidelines for Safe Surgery; Safe Surgery Saves Lives. Geneva; 2009. https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/44185/9789241598552_eng.pdf?sequence=1. Accessed 12 Jan 2025. [PubMed]

- 17.The Expert Committee on Tribal Health. Tribal Health in India: Bridging the Gap and a Roadmap for the Future. New Delhi; 2013. https://nhm.gov.in/nhm_components/tribal_report/Executive_Summary.pdf. Accessed 11 May 2025.

- 18.State Health Resource Centre Atal Bihari Vajpayee Institute of Good Governance and Policy Analysis. Tribal Health in Madhya Pradesh. Bhopal; 2024. https://aiggpa.mp.gov.in/uploads/project/tribal_health.pdf. Accessed 11 Jan 2025.

- 19.Office of Commissioner & Registrar General of the India. Population Census 2011: Shahdol district. 2016. https://www.census2011.co.in/census/district/327-shahdol.html. Accessed 14 July 2018.

- 20.Office of Commissioner & Registrar General of the India. Census of India 2011 Madhya Pradesh: District Census Handbook Anuppur. New Delhi; 2016.

- 21.Office of the Registrar General India. Census of India: Umaria District Population, Madhya Pradesh - Census India 2011. Office of registrar General & Census Commissioner, Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India.

- 22.National Health Mission (NHM). Guidelines for Antenatal Care and Skilled Attendance at Birth by ANMs/LHVs/SNs. New Delhi; 2010. https://nhm.gov.in/images/pdf/programmes/maternal-health/guidelines/sba_guidelines_for_skilled_attendance_at_birth.pdf. Accessed 12 Jan 2025.

- 23.Singh AR. Epicollect5 - SSI at GMC Shahdol. https://five.epicollect.net/myprojects/ssi-at-gmc-shahdol. Published January 18, 2023. Accessed 13 Jan 2025.

- 24.World Health Organization. WHO Recommendations Intrapartum Care for a Positive Childbirth Experience Executive Summary. Geneva, Switzerland; 2018. www.who.int/reproductivehealth. Accessed 16 Jan 2025. [PubMed]

- 25.Hirani S, Trivedi NA, Chauhan J, Chauhan Y. A study of clinical and economic burden of surgical site infection in patients undergoing caesarian section at a tertiary care teaching hospital in India. PLoS One. 2022;17(6):e0269530. 10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0269530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ketema DB, Wagnew F, Assemie MA, et al. Incidence and predictors of surgical site infection following cesarean section in North-west Ethiopia: a prospective cohort study. BMC Infect Dis. 2020;20(1):1–11. 10.1186/S12879-020-05640-0/TABLES/6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mpogoro FJ, Mshana SE, Mirambo MM, Kidenya BR, Gumodoka B, Imirzalioglu C. Incidence and predictors of surgical site infections following caesarean sections at Bugando Medical Centre, Mwanza. Tanzania Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2014;3(1):1–10. 10.1186/2047-2994-3-25/TABLES/5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chourasia S, Kumar R, Singh MPSS, Vishwakarma C, Gupta AK, Shanmugam R. High prevalence of anemia and inherited hemoglobin disorders in tribal populations of Madhya Pradesh state, India. Hemoglobin. 2020;44(6):391–6. 10.1080/03630269.2020.1848859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ganesh B, Rajakumar T, Acharya SK, Kaur H. Sickle cell anemia/sickle cell disease and pregnancy outcomes among ethnic tribes in India: an integrative mini-review. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2022;35(25):4897–904. 10.1080/14767058.2021.1872536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tuuli MG, Stout MJ, Martin S, Rampersad RM, Cahill AG, Macones GA. Comparison of suture materials for subcuticular skin closure at cesarean delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215(4):490.e1–490.e5. 10.1016/j.ajog.2016.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sobodu O, Nash CM, Stairs J. Subcuticular suture type at cesarean delivery and infection risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2024. 10.1016/j.jogc.2023.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alemayehu MA, Azene AG, Mihretie KM. Time to development of surgical site infection and its predictors among general surgery patients admitted at specialized hospitals in Amhara region, northwest Ethiopia: a prospective follow-up study. BMC Infect Dis. 2023;23(1):334. 10.1186/S12879-023-08301-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Allegranzi B, Donaldson LJ, Kilpatrick C, et al. Infection prevention: laying an essential foundation for quality universal health coverage. Lancet Glob Health. 2019;7(6):e698–700. 10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30174-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.National Health Mission. Anaemia Mukt Bharat:: National Health Mission. Ministry of Health & Family Welfare, Government of India. https://nhm.gov.in/index1.php?lang=1&level=3&sublinkid=1448&lid=797. Accessed 18 Jan 2025.

- 35.Mangram A, Horan T, Pearson M, Silver L, Jarvis W. Guideline for Prevention of Surgical Site Infection, 1999. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Hospital Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. Am J Infect Control. 1999;27(2):97–132. 10.1055/s-2001-12415. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Allegranzi B, Nejad SB, Combescure C, et al. Burden of endemic health-care-associated infection in developing countries: systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2011;377(9761):228–41. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61458-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Neogi SB, Malhotra S, Zodpey S, Mohan P. Assessment of special care newborn units in India. J Health Popul Nutr. 2011;29(5):500–9. 10.3329/JHPN.V29I5.8904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tayade S, Gangane N, Kore J, Kakde P, Resident S, Resident J. Surveillance of surgical site infections following gynecological surgeries in a rural setup-Lessons learnt. Indian Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology Research. 6(1):58. 10.18231/2394-2754.2019.0013.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data is provided within the manuscript as supplementary file's'and'g'and analysis codes are provided as''ssi"rmd file.