Abstract

We conducted a brief computer-based assessment involving choices of concurrently presented arithmetic problems associated with competing reinforcer dimensions to assess impulsivity (choices controlled primarily by reinforcer immediacy) as well as the relative influence of other dimensions (reinforcer rate, quality, and response effort), with 58 children. Results were compared for children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) who were and were not receiving medication, and with typically developing children without ADHD. Within-subject and between-groups analyses of the ordinal influence of each of the reinforcer dimensions were conducted using both time- and response-allocation measures. In general, the choices of children with ADHD were most influenced by reinforcer immediacy and quality and least by rate and effort, suggesting impulsivity. The choices of children in the non-ADHD group were most influenced by reinforcer quality, and the influence of immediacy relative to the other dimensions was not statistically significant. Results are discussed with respect to the implications for assessment and treatment of ADHD.

Keywords: attention deficity hyperactivity disorder, assessment, impulsivity, delay, concurrent schedules

The diagnosis of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) has increased dramatically in the last decade (see Purdie, Hattie, & Carroll, 2002). One of the diagnostic criteria for ADHD, impulsivity (American Psychiatric Association, 2000), is a core deficit of ADHD that underlies academic underachievement as well as behavioral and social difficulties (Barkley, Fischer, Edelbrock, & Smallish, 1990; Cantwell & Baker, 1992; Shoda, Mischel, & Peake, 1990). However, there is no commonly accepted objective measure for diagnosing ADHD, and diagnosis is typically based on subjective criteria (Conners, 2000). According to Barkley (1997), ADHD is fundamentally a problem of self-control, or impaired behavioral inhibition, that manifests in behavior that is “less likely to be aimed at maximizing net future outcomes over immediate ones” (p. 258) as a result of “diminished capacity to bridge delays in reinforcement” (p. 289). This conceptualization suggests that the behavior of individuals with ADHD is affected principally by immediate consequences, whereas delayed consequences are heavily discounted (i.e., the value of a desired consequence diminishes as a function of the delay to that consequence).

In basic and applied behavioral research, impulsivity and its converse, self-control, have been examined using a concurrent-schedules paradigm, which emphasizes the contextual nature of the constructs as depending on the size, quality, and delay of outcomes for competing response alternatives. These constructs are operationally defined as choices between concurrently available response alternatives that produce either delayed reinforcers with relatively high yields (self-control) or immediate reinforcers with smaller yields (impulsivity) (e.g., Neef, Bicard, & Endo, 2001; Neef, Mace, & Shade, 1993; Rachlin, 1974).

Although research suggests that choices involving immediate versus delayed outcomes have a significant role in the behaviors of children with ADHD, these relations have rarely been explicitly examined (see Critchfield & Kollins, 2001). It might be predicted from Barkley's (1997) conceptualization that children with ADHD would discount the value of delayed rewards, whereas peers without ADHD would be less likely to do so. On the other hand, some have argued that the behaviors associated with ADHD are within the realm of normal behavior for children but are subject to inconsistent interpretation (see Purdie et al., 2002). This issue might be addressed with a functional account of impulsivity as an alternative to the topographically defined measures typically used to diagnose ADHD.

We used measures based on a concurrent-schedules arrangement with a sample of students with a diagnosis of ADHD (who were and were not receiving medication) and typically developing students without ADHD to determine the extent to which their choices between competing response alternatives demonstrated impulsivity or self-control. In addition to examining sensitivity to immediacy of reinforcement, we assessed the relative influence of other reinforcer dimensions as a basis of comparison.

Method

Participants

Children aged 7 to 14 years from three urban public elementary schools and one private school were invited to participate. Students with ADHD were enrolled if they met the following criteria: (a) met the diagnostic criteria for ADHD (American Psychiatric Association, 2000), (b) demonstrated command of basic arithmetic skills (at minimum, addition without regrouping), (c) parent or guardian gave informed consent (including agreement that the student's medication status would remain unchanged throughout the child's participation in the study), and (d) the student assented to participate. Students with ADHD who met enrollment criteria completed a baseline assessment on the computer task (described under Experimental Conditions) to ensure that they discriminated each of the relevant reinforcer dimensions. Students who did not demonstrate the required discriminations (n = 6) were excluded from further participation.

Typically developing children without ADHD from the same classrooms who most closely matched the demographic characteristics of the enrolled participants with ADHD (age, grade, race, gender) were then selected for participation based on the following criteria: (a) no diagnosed disability, (b) basic arithmetic skills (at a minimum, addition without regrouping), (c) informed consent of parent or guardian, and (d) participant assent. Students who did not demonstrate discrimination of the relevant reinforcer dimensions as determined by baseline assessment on the computer task (described under Experimental Conditions) were excluded from further participation (n = 7). Additional students from both groups were subsequently excluded if they performed inconsistently (i.e., if their patterns of responding suggested control by variables other than the target dimensions, such as alternating between sides after completing a set number of problems) or if they were unavailable for regular participation (12 students with ADHD and 5 students without ADHD). Participants with ADHD were subdivided into those who were and were not receiving medication. Additional participants with ADHD who were not receiving medication were subsequently recruited because of the small size of that group. This resulted in 34 participants with ADHD (21 of whom were receiving medication consisting of methylphenidate, amphetamine salts, or d-amphetamine) and 24 participants without ADHD. The characteristics of the participants in each group are described in Table 1.

Table 1. Characteristics of Participants.

| ADHD no medication | ADHD medication | Non-ADHD | |

| N | 13 | 21 | 24 |

| Mean age | 10.3 years | 10.1 years | 10.4 years |

| Grade | |||

| 2–4 | 6 (46%) | 9 (43%) | 10 (42%) |

| 5–7 | 7 (54%) | 12 (57%) | 14 (58%) |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 11 (85%) | 13 (62%) | 13 (54%) |

| Female | 2 (15%) | 8 (38%) | 11 (46%) |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Caucasian | 5 (38.5%) | 14 (67%) | 12 (50%) |

| African-American | 5 (38.5%) | 3 (14%) | 10 (42%) |

| Other | 3 (23%) | 4 (19%) | 2 (8%) |

Apparatus and Setting

The experimental task was conducted on a Dell laptop computer (Inspiron® 3800 or 5000c) using a software program similar to one described by Neef and Lutz (2001b) and Neef et al. (2001). The program provided a menu from which the experimenter selected the specifications for each of two sets of mathematics problems. The specifications consisted of the type (addition, subtraction, multiplication, or division) and level of mathematics problems, the variable-interval (VI) schedules of reinforcement (VI 30 s, VI 60 s, or VI 90 s), back-up reinforcer delivery schedules (e.g., end of the session or next session), and back-up reinforcer repositories (Store A and Store B). The computer program was equipped to record (for each problem set) the number of points obtained, the number of problems attempted, the number of problems completed accurately and inaccurately, and the cumulative time spent on each problem set. The study was conducted 3 to 5 days per week in a secluded area of the school with only the experimenter and the student present. One or two sessions were conducted per day.

Experimental Conditions and Procedure

During each session throughout all phases of the study, the student completed a 5-min practice session followed by a 10-min test session. During each trial, two different-colored mathematics problems (one from each set selected from the menu) appeared on the monitor (choice screen). The response effort required for problem completion was evident from the problems displayed. The choice screen also displayed under each problem the cumulative number of reinforcers (points) obtained from that problem set, the store from which items could be purchased with the points earned (reinforcer quality), and when those items could be obtained (reinforcer delay). The student then selected either the Set 1 or Set 2 mathematics problem using a mouse pointer. The choice response produced only the selected problem on the screen and a representation of a small clock that showed how much time was left to complete the problem. The problem remained on the screen until the student entered the correct answer from the keyboard, the preset time of 30 s elapsed with no response, or the student reset the problems, after which the choice screen appeared with two new problems. Following an incorrect response, the words “try again” appeared on the screen, the computer presented the same problem, and the 30-s interval was reset. Different auditory stimuli signaled reinforcer delivery for Set 1 or Set 2 problems according to the schedule in effect for the problem set. During the 5-min practice preceding each test session, the student was required to sample both alternatives to ensure contact with the respective reinforcement schedules.

The dependent variables were (a) the percentage of time allocated to the respective problem sets (time allocation) and (b) the percentage of selections allocated to the respective problem sets (response allocation). The assessment identified relative sensitivities to response alternatives associated with competing dimensions. The former dependent variable was used because the VI schedules were based on time allocation. The latter dependent variable was used because time allocation might have been affected by more difficult problems that took more time to complete when effort was a competing dimension.

Assessment consisted of baseline, initial assessment, and replication involving four dimensions: rate (R), quality (Q), immediacy (I), and effort (E). A baseline was first conducted to establish the student's sensitivity to each dimension in isolation (higher vs. lower level of the dimension). For example, to determine sensitivity to rate of reinforcement, a VI 30-s schedule was programmed for Set 1 problems and a VI 90-s schedule was programmed for Set 2 problems, while quality, effort, and immediacy were equal for both problem sets. This was done to confirm that the student's responding was sensitive to the favorable level of the dimension (e.g., problems associated with a higher rate of reinforcement). For effort, preferences could be demonstrated for either easy or more challenging problems. A minimum of four sessions was conducted during baseline (one session for each dimension). If the initial results for a particular dimension showed only a minimal difference in response allocation, additional sessions were conducted to confirm discrimination.

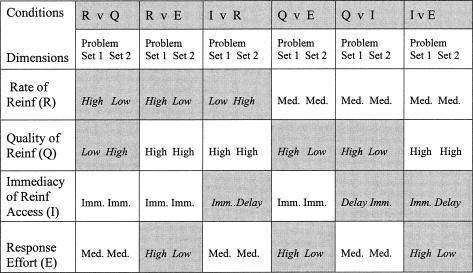

Baseline was followed by an initial assessment comprised of six conditions (one session per condition), conducted in random order. During each condition, one of the dimensions (rate, quality, immediacy, or effort) was placed in direct competition with another dimension (the assignment of dimensions to Set 1 or Set 2 problems varied). For example, RvI involved arithmetic problem alternatives associated with high-rate delayed reinforcement versus low-rate immediate reinforcement. Across the six assessment conditions, all possible pairs of dimensions were presented (RvQ, RvE, IvR, QvE, QvI, IvE). The conditions are depicted in Figure 1. The RvI, QvI, and IvE conditions provided an assessment of impulsivity.

Figure 1. Dimensions of the response alternatives for each assessment condition.

Shaded boxes represent the competing dimensions in each condition.

Rate (R) refers to the concurrent schedules of reinforcement in effect for the respective sets of problems. A VI 30-s schedule was used for the high value, VI 60 s for the medium value, and VI 90 s for the low value. The high and low values were used for the respective sets of problems when rate was a competing dimension (RvE, QvE, and IvE), and the medium value was used during the remaining conditions when rate was held constant across problem sets.

Quality (Q) refers to the student's relative preference for the reinforcers associated with the two respective problem sets, based on his or her ranking of available reinforcers during a preference assessment. Available rewards included a wide variety of tangible items (e.g., small toys, snacks), coupons for extra time in a preferred activity (e.g., playing computer games alone), and extra attention (e.g., playing a game with the experimenter, a certificate of task performance designed to evoke praise). During the preference assessment, 10 items were displayed, and the student was asked to select the item he or she most wanted to earn that day. That item was then set aside, and the process was repeated for the next nine items. The first to fifth favorite items served as the high-quality reinforcers (Store A). The remaining five items served as the low-quality reinforcers (Store B). When reinforcer quality was not a competing dimension, Stores A and B contained identical sets of five preferred items. During each session, points earned on the respective response alternatives could be used to purchase any items from the designated store. Items were placed in the labeled stores, visible to the student, before each session. Items were identically priced such that one to three items could typically be purchased during a session.

Immediacy (I) refers to whether access to reinforcers earned for the respective set of problems was immediate (at the end of the session) or delayed (immediately preceding the next session). If the student earned enough points for the delayed reinforcer, he or she was given a receipt for delayed delivery of the reward. Sessions in which reinforcer immediacy was a competing dimension were not conducted on Fridays so that the delay duration was not extended beyond 24 hr.

Effort (E) refers to the relative ease with which arithmetic problems from the respective sets could be completed, as determined by pretest performance (rate and accuracy) on samples of different types of problems (see Neef & Lutz, 2001a, for a description). Easy (fluency-level) and difficult (acquisition-level) problems were used for the respective sets in which effort was a competing dimension. Medium-level problems were used in conditions in which effort was held constant across the two problem sets.

Selected conditions, including the most influential dimension, were replicated to strengthen internal validity.

Experimental Design and Data Analysis

Within subjects

A within-subject design, involving an adaptation of a brief functional analysis similar to that described by Cooper, Wacker, Sasso, Reimers, and Donn (1990), was used to determine the relative influence of the four reinforcer dimensions for each of the 58 participants. Data were analyzed for both time allocation and response allocation. A dimension was judged to be most influential if the student allocated the majority of time (responses) to the problem set with the favorable level of that dimension across the three conditions when it competed with any other dimension, during both the initial assessment and replication phases. For example, if the student allocated the most time (responses) to the alternative associated with high-quality reinforcement in the RvQ, QvI, and QvE conditions, quality was judged to be the most influential dimension. A dimension was judged to be the second most influential dimension if the student allocated the majority of time (responses) to the problem set with the favorable level of that dimension across all conditions except when it competed with the most influential dimension, as described earlier. The least influential dimension was determined by allocation of the least amount of time (responses) to the problems associated with that dimension regardless of the competing dimension. Two dimensions were judged to be equally influential if allocation was similar across response alternatives when those two dimensions were in competition during both initial and replication phases. In cases in which more than one dimension was equally influential, both of those dimensions were placed in the same ordinal position (e.g., if immediacy and quality were equal as the most influential dimensions, they were both ranked as 1, and effort and rate were ranked 3 and 4). The experimenters concurred on the ordinal placements based on inspection of the data for each participant.

Between groups

Between-groups comparisons were analyzed descriptively and statistically for both time allocation and response allocation. First, we compared the percentage of children in each of the three groups (ADHD no medication, ADHD medication, and non-ADHD) for whom reinforcer immediacy, quality, rate, and effort were the most, second, third, and least influential dimensions. Second, we used Friedman rank sum tests to determine whether there were statistically significant differences between the six conditions for each of the three groups, and for the non-ADHD and combined (medication and no medication) ADHD groups. Third, we conducted a multiple-comparisons test to determine whether there were statistically significant absolute differences in average ranks for the six pairwise comparisons of the reinforcer dimensions; this analysis was performed for each group (non-ADHD, ADHD no medication, ADHD medication, and ADHD medication and no medication combined). It was necessary to use nonparametric statistics because the distributions for the dependent variables did not meet the assumption of independence from one another.

Results

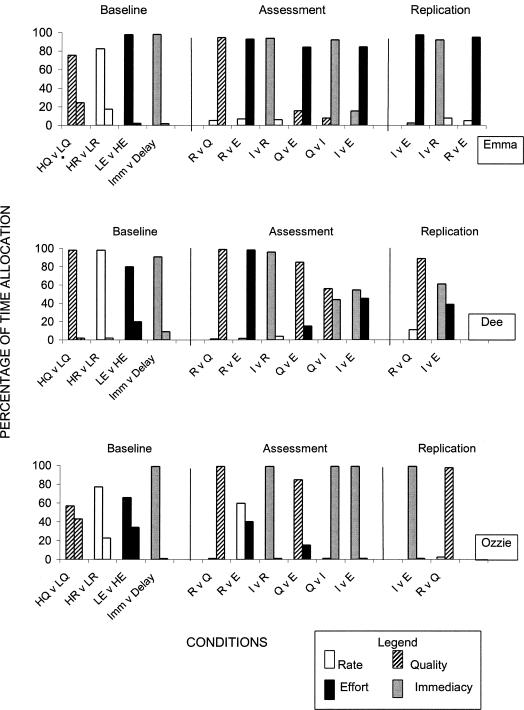

Figure 2 shows illustrative results of different outcomes for 3 participants (Emma, Dee, and Ozzie) based on the percentage of time allocation to problems with competing dimensions. (Dimensions judged to be influential based on response allocation were determined in a like manner.) During the baseline condition when response options were equal on all but one dimension, all 3 of these children allocated the majority of their time to the alternative producing higher quality reinforcement, higher rate of reinforcement, lower effort, and more immediate reinforcement, confirming that they discriminated the different values of each dimension.

Figure 2. Illustrative results showing the percentage of time allocation to problem alternatives across assessment conditions.

The top panel of Figure 2 shows results for Emma (ADHD medication group) for whom response effort was the most influential dimension, followed by reinforcer immediacy, quality, and rate. Emma allocated the majority of time to the lower effort problems (black bars) even when they produced a lower rate of reinforcement (RvE), less preferred reinforcers (QvE), and more delayed access to reinforcers (IvE) relative to the alternative. When effort was held constant across the response alternatives, Emma allocated the most time to the alternative producing more immediate but lower rate (IvR) or lower quality (QvI) reinforcement. Emma consistently allocated the least time to the problem alternative that produced the higher rate of reinforcement when it competed with any other dimension (RvQ, RvE, IvR). Similar results were obtained when the IvE, IvR, and RvE conditions were replicated.

The middle panel of Figure 2 shows results for Dee (non-ADHD group) for whom reinforcer quality was the most influential dimension, followed by reinforcer immediacy, reponse effort, and reinforcer rate. Dee allocated the majority of time to the alternatives that produced higher quality reinforcers (striped bars) even when they produced a lower rate of reinforcement (RvQ), when they were associated with more effortful problems (QvE), or when they yielded delayed access to the reinforcers (QvI). When reinforcer quality was equal across the two response alternatives (i.e., not a competing dimension), Dee allocated the most time to the option that produced immediate access to reinforcers, responding almost exclusively to that option when it competed with rate (IvR), and slightly more time than to the option associated with lower effort problems (IvE). As with Emma, Dee rarely chose the alternatives associated with the higher rate of reinforcement when they competed with any other dimension (RvQ, RvE, IvR). Replication of the RvQ and IvE conditions produced results similar to those of the initial assessment.

The bottom panel shows assessment results for Ozzie (ADHD no-medication group) for whom reinforcer immediacy was the most influential dimension, followed by reinforcer quality, reinforcer rate, and response effort. Specifically, Ozzie responded exclusively to the problem alternatives that produced more immediate access to reinforcers, even though that alternative resulted in a lower rate of reinforcement (IvR), lower quality of reinforcement (QvI), or more difficult problems (IvE). However, when reinforcer immediacy was held constant across the problem alternatives, he allocated the majority of time to the alternatives that produced higher quality (more preferred) reinforcers (RvQ, QvE). He consistently allocated the least time to the low-effort problems when high-effort problems resulted in more immediate, higher quality, or a higher rate of reinforcement. The same results were obtained when the two most influential dimensions competed with the two least influential dimensions in the IvE and RvQ conditions of the replication phase.

The results for all 58 participants are summarized in Tables 2 and 3, which show the percentage of children in each of the three groups (ADHD no medication, ADHD medication, and non-ADHD) for whom reinforcer immediacy, quality, rate, and response effort were the most, second, third, and least influential dimensions (as described in the data analysis section). Results for time allocation are shown in Table 2, and results for response allocation are shown in Table 3. The results of a Friedman ranks sum test for time and response allocation across the combined ADHD (medication and no medication) and non-ADHD groups are shown in Appendix A, and suggest that the differences in performance between reinforcement conditions were larger for the ADHD groups than for the non-ADHD group. Appendix B shows the results of the multiple comparisons tests across each of the conditions for these two groups.

Table 2. Percentage of Students in Each Group by Ordinal Influence of Dimensions for Time Allocation.

| Ordinal influence | Dimensions | |||

| Immediacy | Quality | Effort | Rate | |

| ADHD no medication (n = 13) | ||||

| 1 | 53.8 | 46 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 30.8 | 46 | 31 | 7.7 |

| 3 | 7.7 | 8 | 15 | 61.5 |

| 4 | 7.7 | 0 | 54 | 30.8 |

| ADHD medication (n = 21) | ||||

| 1 | 48 | 28.6 | 24a | 0 |

| 2 | 33 | 47.6 | 14 | 14.3 |

| 3 | 14 | 19 | 5 | 52.4 |

| 4 | 5 | 4.8 | 57 | 33.3 |

| Non-ADHD (n = 24) | ||||

| 1 | 21 | 46 | 25b | 12.5 |

| 2 | 67 | 29 | 12.5 | 21 |

| 3 | 8 | 21 | 16.7 | 37.5 |

| 4 | 4 | 4 | 45.8 | 29 |

One of the 5 children chose high-effort rather than low-effort problems.

Four of the 6 children chose high-effort rather than low-effort problems.

Table 3. Percentage of Students in Each Group by Ordinal Influence of Dimensions for Response Allocation.

| Ordinal influence | Dimensions | |||

| Immediacy | Quality | Effort | Rate | |

| ADHD no medication (n = 13) | ||||

| 1 | 38.5 | 54 | 8 | 0 |

| 2 | 38.5 | 46 | 15 | 0 |

| 3 | 8 | 0 | 23 | 69 |

| 4 | 15 | 0 | 54 | 31 |

| ADHD medication (n = 21) | ||||

| 1 | 43 | 33 | 29 | 0 |

| 2 | 38 | 43 | 14 | 19 |

| 3 | 14 | 19 | 14 | 38 |

| 4 | 5 | 5 | 43 | 43 |

| Non-ADHD (n = 24) | ||||

| 1 | 12.5 | 50 | 29 | 12.5 |

| 2 | 50 | 21 | 29 | 20.8 |

| 3 | 33.3 | 25 | 21 | 16.7 |

| 4 | 4.2 | 4 | 21 | 50 |

Time allocation

As shown in Table 2, the results were similar across ADHD no-medication, ADHD medication, and non-ADHD groups, in that reinforcer quality and immediacy were the dimensions that influenced most children's choices. For the ADHD no-medication group, immediacy was the most influential dimension for the majority of participants (54%), and was the first or second most influential dimension for 85% of these students. Quality was the most influential dimension for 46% of the participants in this group and was the first or second most influential dimension for 92% of the participants. A multiple-comparisons test (Appendix B) showed that the preferences (absolute difference in average ranks) for reinforcer quality relative to rate and effort and immediacy relative to effort were statistically significant (α = .05).

For the ADHD medication group, immediacy was the most influential dimension for 48% of the participants and the second most influential dimension for 33% of the participants. Thus, immediacy accounted for the first or second most influential dimension for 81% of the participants in this group. Quality was similar; it was the first and second most influential dimension for 29% and 48% of the participants, respectively. A multiple-comparisons test revealed that the absolute difference in average ranks for both immediacy and quality relative to rate (but not effort) was statistically significant for this group (α = .05). For the ADHD medication and no-medication groups combined, the preferences for reinforcer quality and immediacy relative to rate and effort were statistically significant (α = .05).

For the non-ADHD group, quality was the most influential dimension for the greatest percentage of participants (46%), and immediacy was the second most influential dimension for the majority of participants (67%). Taken together, immediacy was the first or second most influential dimension for 88% of the participants, and quality was the first or second most influential dimension for 75% of the participants. A multiple-comparisons test, however, did not reveal statistically significant absolute differences in average ranks for the six conditions.

Response allocation

As shown in Table 3, results for response allocation were similar to those for time allocation for the participants in the ADHD groups in that reinforcer quality and immediacy were the most influential dimensions. However, quality was the most influential dimension and immediacy was the second most influential dimension for the ADHD no-medication group. Immediacy was the most influential dimension and quality was the second most influential dimension for the ADHD medication group. The absolute differences in ranks for reinforcer quality and immediacy relative to rate were statistically significant for the medication group (α = .05). For the combined ADHD groups, the preferences for quality relative to rate and effort and for immediacy relative to rate were statistically significant (α = .05).

Quality was the first or second most influential dimension for 71% of the non-ADHD participants. The preferences for quality and effort relative to rate were statistically significant (α = .05). Although immediacy was the first or second most influential dimension for 63% of the non-ADHD participants, the preference for immediacy relative to the other three dimensions was not statistically significant.

The three groups of participants differed somewhat with respect to performance of math problems. The mean number of total problems completed correctly was highest for the non-ADHD group (779 correct of 817 problems), followed by the ADHD medication group (633 correct of 725 problems) and the ADHD no-medication group (557 correct of 624 problems). The mean percentage of correct responses across all conditions was 95%, 87%, and 89% for participants in the non-ADHD, ADHD medication, and ADHD no-medication groups, respectively.

Discussion

The results of the study indicate that the choices of children with ADHD were influenced principally by reinforcer immediacy and quality and least by rate and effort. Impulsivity, when defined as choices between concurrently available response alternatives that produce more immediate but fewer reinforcers, characterized the responding of most of the participants with a diagnosis of ADHD, whether or not they were receiving medication. Reinforcer immediacy was the most influential dimension with respect to time allocation for both ADHD groups and was second only to reinforcer quality with respect to response allocation for the no-medication group. The choices of children in the non-ADHD group, on the other hand, were influenced principally by reinforcer quality, and the influence of immediacy relative to the other dimensions was not statistically significant.

These findings have several key implications. First, they are consistent with a diagnostic criterion for ADHD, and they appear to support Barkley's (1997) assertion that ADHD is fundamentally a problem of self-control, which manifests in behavior that is “less likely to be aimed at maximizing net future outcomes over immediate ones” (p. 258). The finding that reinforcer immediacy was an influential dimension for ADHD participants in both the medication and no-medication groups suggests that medication may have little effect on functionally defined objective measures of impulsivity. Conversely, it is possible that the medicated group started out extreme in this respect and that the medication normalized these students' performance to some extent. Although the relatively few participants in the medication group limit conclusions, the findings are consistent with those of Neef, Bicard, Endo, Coury, and Aman (in press), who used a double blind, placebo-controlled reversal design to examine the effects of stimulant medication on impulsivity. The findings of both studies are inconsistent with findings in the research literature on ADHD that medication improves impulse control (see Barkley, 1997). This discrepancy might be accounted for by the measures used; in most cases, improvements have been evaluated on the basis of parent and teacher ratings or measures that may be either subject to influence by, or confounded with, perceptions of other behavioral changes (e.g., time on task, level of activity, vocalizations).

A potentially important consideration, however, is whether impulsivity is assessed on the basis of delays to the exchange period for terminal reinforcers (e.g., preferred rewards) or with respect to the delivery of points that may function as conditioned reinforcers. Basic research using analogues to self-control methods with humans suggests that the former is a more critical determinant of choice than the latter (Jackson & Hackenberg, 1996). Nevertheless, differences between children who are and are not receiving medication (or differences between other populations) may become more apparent without the use of intervening stimuli, which is more typical of classroom situations (e.g., independent seat work in which students complete worksheets with no consequences for responses until the worksheets are graded at a later time). To evaluate that possibility, the procedures in the current study might be compared with a condition in which points are not displayed until the session is completed.

Although the results for children in the medication and no-medication ADHD groups were similar, there were several differences for children with and without a diagnosis of ADHD. First, reinforcer quality was more influential than reinforcer immediacy for more children in the non-ADHD group than in the ADHD group. Second, children in the non-ADHD group completed more problems with a higher percentage of correct solutions than did children with ADHD. Third, of the minority of participants for whom effort was most influential, those without ADHD were more likely to choose problems that were challenging, whereas the participants with ADHD were more likely to avoid them. Choices governed by easy problems might reflect a form of impulsivity, in that the latency to both positive (point delivery) and negative (termination of the problem stimulus) reinforcement is longer for difficult problems because they take more time to complete.

The results are grounds for optimism with respect to the potential for environmental influences to mitigate impulsivity. Specifically, the finding that reinforcer quality was also an influential dimension for children in the ADHD groups suggests the potential for highly preferred stimuli to compete effectively with reinforcer immediacy in the development of self-control, as demonstrated by Neef et al. (2001).

A contribution of this study relative to most other comparisons of children with and without ADHD (e.g., Campbell, Pierce, March, Ewing, & Szumoswski, 1994) is that an independent within-subject analysis was conducted with each of the 58 participants (analogous to the experimental-epidemiological examination of self-injurious behavior conducted by Iwata et al., 1994). This type of analysis with large numbers of participants is labor intensive and time consuming, and practical considerations dictated the use of an abbreviated assessment. The strengths of the analysis must therefore be balanced against the limitations of the abbreviated assessment, including inadequate provision for determining within-condition variability, and the use of single, constant values of each dimension to examine their relative influence.

Conclusions are also limited by differences in demographic characteristics between the groups. To match participants with and without ADHD as closely as possible with respect to age, grade, and socioeconomic status, an effort was made to recruit them from the same classrooms of the same schools. However, the restricted pool necessarily limited matching on all variables. For example, the non-ADHD group contained proportionally more females. This imbalance was likely due to the known high male-to-female ratio among ADHD children. In addition, there were relatively few children diagnosed with ADHD who were not receiving medication, which weakened the power of statistical comparisons with this group (see Appendixes A and B for statistical comparisons for each group, including by gender). Thus, further replications are needed to determine the generality of our findings. The limitations notwithstanding, the study demonstrates application of a conceptual and methodological framework for investigations of impulsivity that may lead to improvements in diagnosis, assessment, and evaluation of treatments for children with ADHD.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a field-initiated grant from the U.S. Department of Education, Office of Special Education Programs. The opinions expressed herein do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of that agency. We gratefully acknowledge Stephanie Peterson and Min Gao for their consultation; Laurice Joseph for her assistance with the diagnostic assessments of the participants with ADHD; Kendra Dawson, Kyle Evans, Megan Duffy, Joyce McNally, Lorraine Stachler, and Erin Callahan for their assistance with data collection; and Kelly Hunter-Rice and the personnel at Marburn Academy and Easthaven, Como, and South Haven elementary schools for their cooperation and assistance with the investigation.

Appendix A

Friedman Rank Sums Test Results for Time and Response Allocation Across Combined ADHD and Non-ADHD Groups.

| Friedman test statistic | df | P value | ||

| Time allocation | ||||

| Combined ADHD | Overall | 25.4134 | 3 | 1.265e-05 |

| Males | 17.9607 | 3 | 0.0004481 | |

| Females | 9.12 | 3 | 0.02774 | |

| Non-ADHD | Overall | 5.5837 | 3 | 0.1337 |

| Males | 3.2017 | 3 | 0.3616 | |

| Females | 3.4 | 3 | 0.3340 | |

| Response allocation | ||||

| Combined ADHD | Overall | 18.6839 | 3 | 0.0003178 |

| Males | 12.2751 | 3 | 0.006498 | |

| Females | 9.6 | 3 | 0.02229 | |

| Non-ADHD | Overall | 12.943 | 3 | 0.004762 |

| Males | 9.9 | 3 | 0.01944 | |

| Females | 5.1333 | 3 | 0.1623 | |

Appendix B

Multiple-Comparisons Test of the Absolute Differences of Average Ranks Across Reinforcement Conditions for Combined ADHD and Non-ADHD Groups.

| Group | Time allocation | Response allocation | |

| Combined ADHD groups | |||

| RvQ | Overall | 1.2273* | 1.2121* |

| Males | 1.3261* | 1.2174* | |

| Females | 1 | 1.2 | |

| RvE | Overall | 0 | 0.2273 |

| Males | 0.0 | 0.1522 | |

| Females | 0.0 | 0.4 | |

| IvR | Overall | 1.0152* | 0.8636* |

| Males | 0.8478 | 0.5435 | |

| Females | 1.4 | 1.6* | |

| QvE | Overall | 1.2273* | 0.9848* |

| Males | 1.3261* | 1.0652* | |

| Females | 1 | 0.8 | |

| QvI | Overall | 0.2121 | 0.3485 |

| Males | 0.4783 | 0.6739 | |

| Females | 0.4 | 0.4 | |

| IvE | Overall | 1.0152* | 0.6364 |

| Males | 0.8478 | 0.313 | |

| Females | 1.4 | 1.2 | |

| Non-ADHD group | |||

| RvQ | Overall | 0.809524 | 1.2857* |

| Males | 0.9167 | 1.5* | |

| Females | 0.667 | 1 | |

| RvE | Overall | 0.166667 | 1.1905* |

| Males | 0.2917 | 1.2497 | |

| Females | 0 | 1.111 | |

| IvR | Overall | 0.642857 | 0.85714 |

| Males | 0.4584 | 0.583 | |

| Females | 0.889 | 1.222 | |

| QvE | Overall | 0.642857 | 0.09524 |

| Males | 0.625 | 0.2503 | |

| Females | 0.667 | 0.111 | |

| QvI | Overall | 0.166667 | 0.42857 |

| Males | 0.45833 | 0.917 | |

| Females | 0.222 | 0.222 | |

| IvE | Overall | 0.47619 | 0.33333 |

| Males | 0.16667 | 0.6667 | |

| Females | 0.889 | 0.111 | |

*Indicates differences that are statistically significant (familywise error rate is α = 0.05).

Study Questions

Define self-control and impulsivity. How are these concepts critical in diagnosing attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)?

Briefly describe the experimental task. Why were data collected on time and response allocation?

What reinforcer dimensions were examined, and how was sensitivity to them assessed?

Why did the authors conduct both within-subject and between-groups comparisons?

Summarize the general results of the between-groups comparison with respect to time and response allocation.

How do the results of the study support the traditional diagnostic criteria of ADHD?

In addition to immediacy, quality was also an influential reinforcer dimension for most participants. What might these results suggest for behavioral interventions aimed at mitigating impulsivity?

According to the authors, how might the selection of easy problems reflect a form of impulsivity?

Questions prepared by Natalie Rolider and Jennifer N. Fritz, University of Florida

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed., text rev. Washington, DC: Author; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Barkley R.A. ADHD and the nature of self-control. New York: Guilford; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Barkley R.A, Fischer M, Edelbrock C.S, Smallish L. The adolescent outcome of hyperactive children diagnosed by research criteria: I. An 8-year prospective follow-up study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1990;29:546–557. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199007000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell S.B, Pierce E.W, March C.L, Ewing L.J, Szumoswski E.K. Hard-to-manage preschoolers: Symptomatic behavior across contexts and time. Child Development. 1994;65:836–851. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantwell D.P, Baker L. Association between attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder and learning disorders. In: Shaywitz S.E, Shaywitz B.A, editors. Attention deficit disorder comes of age: Toward the twenty-first century. Austin, TX: Pro-Ed; 1992. pp. 145–164. [Google Scholar]

- Conners C.K. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder—historical development and overview. Journal of Attention Disorders. 2000;3:173–191. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper L.J, Wacker D.P, Sasso G.M, Reimers T.M, Donn L.K. Using parents as therapists to evaluate appropriate behavior of their children: Application to a tertiary diagnostic clinic. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1990;23:285–296. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1990.23-285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Critchfield T.S, Kollins S.H. Temporal discounting: Basic research and the analysis of socially important behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2001;34:101–122. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2001.34-101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwata B.A, Pace G.M, Dorsey M.F, Zarcone J.R, Vollmer T.R, Smith R.G, et al. The functions of self-injurious behavior: An experimental-epidemiological analysis. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1994;27:215–240. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1994.27-215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson K, Hackenberg T.D. Token reinforcement, choice, and self-control in pigeons. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1996;66:29–49. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1996.66-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neef N.A, Bicard D.F, Endo S. Assessment of impulsivity and the development of self-control by students with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2001;34:397–408. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2001.34-397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neef N.A, Bicard D.B, Endo S, Coury D.L, Aman M.G. Evaluation of pharmacological treatment of impulsivity with children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2005.116-02. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neef N.A, Lutz M.N. Assessment of variables affecting choice and application to classroom interventions. School Psychology Quarterly. 2001a;16:239–252. [Google Scholar]

- Neef N.A, Lutz M.N. A brief computer-based assessment of reinforcer dimensions affecting choice. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2001b;34:57–60. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2001.34-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neef N.A, Mace F.C, Shade D. Impulsivity in students with serious emotional disturbance: The interactive effects of reinforcer rate, delay, and quality. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1993;26:37–52. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1993.26-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neef N.A, Shade D, Miller M.S. Assessing the influential dimensions of reinforcers on choice in students with serious emotional disturbance. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1994;27:575–583. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1994.27-575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purdie N, Hattie J, Carroll A. A review of research on interventions for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: What works best? Review of Educational Research. 2002;72:61–99. [Google Scholar]

- Rachlin H. Self-control. Behaviorism. 1974;2:94–107. [Google Scholar]

- Shoda Y, Mischel W, Peake P.K. Predicting adolescent cognitive and self-regulatory competencies from preschool delay of gratification: Identifying diagnostic conditions. Developmental Psychology. 1990;26:978–986. [Google Scholar]