Abstract

The current study describes an assessment sequence that may be used to identify individualized, effective, and preferred interventions for severe problem behavior in lieu of relying on a restricted set of treatment options that are assumed to be in the best interest of consumers. The relative effectiveness of functional communication training (FCT) with and without a punishment component was evaluated with 2 children for whom functional analyses demonstrated behavioral maintenance via social positive reinforcement. The results showed that FCT plus punishment was more effective than FCT in reducing problem behavior. Subsequently, participants' relative preference for each treatment was evaluated in a concurrent-chains arrangement, and both participants demonstrated a clear preference for FCT with punishment. These findings suggest that the treatment-selection process may be guided by person-centered and evidence-based values.

Keywords: aversive, choice, concurrent chains, developmental disabilities, evidence-based values, functional analysis, functional communication training, punishment

Selecting interventions that are most effective in reducing problem behavior and promoting desirable behavior over the short and long term has been advocated for many years (Iwata, 1988; Perone, 2003; Van Houten et al., 1988). Nevertheless, many researchers and practitioners continue to select treatments based on structure or name alone (e.g., antecedent-based or positive-reinforcement-based treatment) or on values that are assumed to be in the best interest of the person with the problem behaviors. The current zeitgeist of providing exclusively positive behavioral interventions (positive behavior support [PBS]; E. G. Carr et al., 2002) is consistent with the approach of restricting treatment options to those that appear to be consumer friendly. More specifically, PBS implies that antecedent-oriented and reinforcement-based interventions should be developed to the exclusion of interventions involving punishment (E. G. Carr et al.). Although this approach seems to be grounded in the antiaversives movement (LaVigna & Donnellan, 1986), it is also predicated on the practices that have emerged from a behavior-analytic approach to understanding and treating problem behavior (J. E. Carr & Sidener, 2002).

Functional analysis, which is used to determine the reinforcing functions of problem behavior and to identify influential establishing operations and discriminative stimuli (Iwata, Pace, Dorsey, et al., 1994), presumably sets the occasion for a focus on positive behavioral interventions (Pelios, Morren, Tesch, & Axelrod, 1999). Once the reinforcer for problem behavior is identified via analysis, treatments can be developed in which the maintaining reinforcer is delivered differentially or noncontingently and withheld following problem behavior (i.e., extinction). Although function-based treatments have been proven effective for a variety of behavior disorders (e.g., Fisher, Piazza, & Page, 1989; Iwata, Pace, Dorsey, et al., 1994; Mace & Lalli, 1991; Piazza et al., 1997; Piazza, Hanley, & Fisher, 1996; Thompson, Fisher, Piazza, & Kuhn, 1998; Vollmer, Northup, Ringdahl, LeBlanc, & Chauvin, 1996), several rigorous component evaluations have shown that these treatments may not be effective for all individuals (Fisher et al., 1993; Hagopian, Fisher, Sullivan, Acquisto, & LeBlanc, 1998; Wacker et al., 1990).

For example, Hagopian et al. (1998) summarized the results of 21 clinical cases involving functional communication training (FCT) as the primary intervention. FCT is differential reinforcement of alternative behavior (DRA), but the reinforcer that maintains problem behavior, rather than an arbitrary reinforcer, is arranged for a socially recognizable alternative response (i.e., the response specifies the reinforcer). In addition, the consequence for problem behavior is often explicitly described in FCT treatments (i.e., extinction, punishment, or continued reinforcement is scheduled for problem behavior). Hagopian et al. found that only 1 of 10 applications were successful (success being defined as a reduction in problem behavior of 80% or better) when problem behavior and the alternative response both resulted in reinforcement. An improvement was seen when extinction for problem behavior was arranged, but still only 17 of 31 applications of FCT plus extinction were successful. Finally, the authors found that FCT was successful when combined with punishment in 17 of 17 applications.

Although these data are compelling, a recent review of the treatment literature suggests that the use of programmed punishment is low (Pelios et al., 1999). This apparent decreased reliance on punishment may be related to the increased dependence on functional analysis for treatment development (Pelios et al.), but is probably also related to the fact that the social acceptability of punishment is low (Blampied & Kahan, 1992; Kazdin, 1980; Miltenberger, Suda, Lennox, & Lindeman, 1991).

Even though questionnaires or rating scales may be appropriate for evaluating the acceptability of an intervention with critical stakeholders in the intervention process (caregivers, teachers, or community members; Miltenberger, 1990), these indirect methods are not appropriate for individuals who cannot readily express their preferences verbally. It may be reasonable for friends, family, and advocates to inform the process of selecting behavioral interventions, as in person-centered planning (Holburn, 1997; Whitney-Thomas, Shaw, Honey, & Butterworth, 1998); however, reliance on the values and preferences of others may not always be in the best interest of the consumer.

As an alternative to both approaches, Hanley, Piazza, Fisher, Contrucci, and Maglieri (1997) described a method for assessing the social acceptability of and preference for behavioral interventions by presenting multiple treatment alternatives in a choice arrangement to the actual person receiving the treatment. In this procedure, referred to as a concurrent-chains arrangement, two function-based interventions, one involving differential reinforcement of an alternative response (i.e., FCT) and the other involving the time-based delivery of the same amount and type of reinforcement (i.e., noncontingent reinforcement [NCR]), were evaluated with 2 children with developmental disabilities. The children were then given an opportunity to choose from among the treatment options (FCT, NCR, and extinction only) by pressing one of three colored switches that were associated with each of the treatments. Each switch press resulted in a brief experience with the selected treatment. Although FCT and NCR were equally effective in reducing problem behavior, both children preferred the FCT intervention.

Instead of relying on a restricted set of treatment options that are assumed to be in the best interest of the consumer, the methods described by Hanley et al. (1997) may be used to identify the most effective and preferred interventions. In other words, the values that guide the selection of particular assessment and treatment strategies can be data based. Furthermore, continued direct evaluation of child and caregiver preferences may ultimately yield an evolving set of evidence-based values that may provide a more solid advocacy foundation for individuals who require or seek evaluation and support services. Finally, the practice of allowing individuals who cannot readily express their biases to participate directly in the treatment-selection process seems to be most consistent with placing the person in the center of the habilitative planning process (Holburn, 1997; Whitney-Thomas et al., 1998) and providing effective and preferred behavioral supports (see also Hanley, Iwata, & Lindberg, 1999).

Therefore, the preference assessment methods described by Hanley et al. (1997) were used in the current investigation to evaluate children's preference for function-based interventions that did and did not involve a punishment contingency. More specifically, the effectiveness of several function-based treatment packages was evaluated with 2 children whose problem behavior was sensitive to adult attention as reinforcement. Following demonstrations of the relative effectiveness of treatments that did and did not involve punishment contingencies, a concurrent-chains procedure was arranged to evaluate children's preferences for the treatments that they had experienced.

Method

Participants

Two children with severe behavior disorders had been admitted to an inpatient unit specializing in the assessment and treatment of problem behavior. Jay was a 5-year-old boy who had been diagnosed with moderate mental retardation, autism, and a seizure disorder. He lived at home with his mother and attended a public preschool with specialized programming for children with autism. His problem behavior included self-injury (hitting and slapping head with hands, hitting head with objects, biting arms, and eye poking), aggression (hitting, kicking, pushing, pinching, hair pulling, scratching, and head butting), and disruption (throwing objects, breaking objects, knocking objects to the floor). He followed simple one- and two-step instructions and ambulated without assistance.

Betty was an 8-year-old girl who had been diagnosed with mild to moderate mental retardation, attention deficit disorder, and oppositional defiant disorder. She also lived at home with her parents, attended a public elementary school with specialized programming, was ambulatory, and followed simple one- and two-step instructions. Betty's aggression (hitting, kicking, pinching, scratching, biting, pulling hair, and throwing objects at people) was the problem behavior in the current investigation. Betty also engaged in pica and self-injury, which were assessed and treated separately from her aggression (due mainly to different behavioral functions). Jay and Betty were included in this series of evaluations because two specific types of treatment (one involving extinction and one involving punishment) were shown to be effective to varying degrees in reducing problem behavior and because each child was available in the inpatient unit for further evaluation of other problem behavior (Betty) or for caregiver training (Jay).

Phase 1: Functional Analysis

Design, Setting, and Procedure

Functional analyses (Iwata, Pace, Dorsey, et al., 1994) were conducted with both participants. Sessions were 10 min in duration and were conducted in therapy rooms (3 m by 3 m) equipped with one-way mirrors. Approximately three to five sessions were conducted per session block (six to 10 sessions per day), and a 5-min break occurred between each 10-min session. Sessions were conducted in a random order within a multielement design for each participant. Levels of problem behavior were assessed across three to five conditions: attention, escape, tangible (Jay only), alone (Jay only), and play.

Prior to attention sessions, the child was given toys and was prompted to play while the therapist engaged in a task (e.g., reading a magazine). During sessions, the therapist provided attention in the form of a brief (5-s) verbal reprimand following each problem behavior. All other responses of the child were ignored. During the escape condition, the therapist delivered sequential verbal, gestural, and physical prompts to complete an academic or self-care task every 10 s until either the child complied with the instruction or engaged in a problem behavior. If the child complied with the instruction following a verbal or gestural prompt, he or she received praise from the therapist. If the child displayed problem behavior, the therapist terminated the instructions and removed the task materials for 30 s (i.e., escape was provided).

Tangible sessions were conducted with Jay because his mother reported that she often provided Jay with preferred toys to “calm him down” during episodes of problem behavior. Jay was allowed to play with preferred activities (a mirror, Pla-Doh®, and a rubber ball) for 2 min prior to the start of the tangible sessions. The therapist withdrew the preferred objects at the onset of the session and returned the items for 30 s following each occurrence of problem behavior. All other responses of the child were ignored. An alone condition also was conducted with Jay to determine if his self-injurious or disruptive behaviors would persist in the absence of any programmed social stimulation. Jay was alone in an otherwise empty room during the alone condition. Toys were available freely, and the therapist delivered attention at least every 30 s during the play condition, which served as the control for the potential reinforcement contingencies arranged in the previously described test conditions.

Data Collection and Interobserver Agreement

Trained observers used laptop computers to record the frequency of problem behaviors for all participants (see topographies and definitions above). Two observers scored problem behaviors simultaneously but independently during 54% and 32% of the sessions for Jay and Betty, respectively. Agreement coefficients were calculated by partitioning each session into consecutive 10-s intervals and dividing the number of exact agreements on the occurrence of behavior by the sum of agreements plus disagreements. This number was then multiplied by 100%. The mean exact agreement coefficients for problem behavior were 99% (range, 95% to 100%) for Jay and 80% (range, 46% to 100%) for Betty. Low agreement scores for Betty in this analysis (and the treatment analysis) were correlated with sessions during which the highest amounts of aggression occurred. This scoring difficulty was at least partly due to the fact that aggression often occurred in bursts of multiple forms of the response (i.e., hitting, kicking, etc.).

Phase 2: Treatment Evaluation

Design, Setting, and Procedure

Several function-based treatments were evaluated in single-subject designs (reversal and multielement) for each participant. All sessions were conducted in individual treatment rooms (3 m by 3 m) equipped with one-way mirrors. Approximately three to five sessions were conducted per session block (six to 10 sessions per day), and a 5-min break occurred between each 10-min session.

Baseline

The baseline condition was similar to the attention condition of the functional analysis. The child was provided with activities and was instructed to play while the therapist attended to a task (e.g., reading a magazine). The therapist delivered approximately 20 s of attention in the form of mild verbal reprimands (e.g., “Don't do that”) and statements of concern (e.g., “You might hurt yourself”) following problem behavior. All other responses were ignored.

FCT training trials

Following baseline but prior to the FCT (and NCR for Jay) evaluation, training trials were conducted to teach the participants alternative responses that would result in access to adult attention. The alternative responses were selected based on the individual's expressive language abilities and the advice of the consulting speech pathologists. The alternative response for Jay was handing a yellow card containing the printed word “play” to the therapist. The alternative response for Betty was saying “attention, please” or “excuse me.” Nine 10-min training sessions were conducted with Jay, and two 10-min training sessions were conducted with Betty to teach the alternative responses.

Training consisted of backward chaining in which Jay was initially physically guided to hand the card to the therapist to obtain 20 s of attention. No attention was provided for problem behavior (i.e., extinction was programmed for problem behavior). The amount of guidance provided to hand the card to the therapist was decreased to a vocal prompt over the course of the training sessions. Subsequently, the vocal prompting was eliminated, and Jay independently engaged in the alternative response throughout the last two training sessions. The therapist vocally prompted Betty to emit either of the two vocal responses to request attention every 30 s, and problem behavior no longer produced attention (extinction) in the initial training session. Betty independently engaged in the alternative response during both training sessions.

FCT

The conditions were the same as those described in baseline with the following exceptions. If the child emitted the alternative response (i.e., saying “attention, please” or “excuse me” for Betty; handing the card to the therapist for Jay), the therapist delivered 20 s of attention (verbal praise and interactive play). If the child engaged in problem behavior, no differential consequence occurred (i.e., extinction). In addition, a blue laminated posterboard (80 cm by 52 cm) was placed on the wall during the FCT treatment sessions for Jay. This item was included in an attempt to establish an association with a salient stimulus (blue posterboard) and the FCT treatment contingencies and to promote discriminated performances during his comparative treatment analysis (similar condition-correlated stimuli were not used with Betty because she experienced only one intervention at a time).

NCR

This intervention was evaluated with Jay only. The conditions were similar to those described for the FCT sessions with the following exceptions: The communication card was not available, a green posterboard (80 cm by 52 cm) was placed on the wall, both problem behavior and alternative responding resulted in no differential consequences, and the therapist delivered 20 s of attention (verbal praise and interactive play) on a time-based schedule. The schedule of attention delivery in the NCR sessions was yoked to the preceding FCT session. During the FCT sessions, a data collector recorded the occurrence of each communicative response on a sheet that was partitioned into 60 10-s intervals. During NCR sessions, 20 s of attention was delivered at the approximate times (in the same intervals) that attention had been delivered in the previous FCT session. This procedure resulted in the same amount and temporal distribution of reinforcement delivered across FCT and NCR sessions. Both FCT and NCR were evaluated with Jay to determine if either treatment was more effective in reducing problem behavior (see Kahng, Iwata, DeLeon, & Worsdell, 1997, and Hanley et al., 1997, for similar comparative analyses). NCR was not evaluated with Betty because strengthening socially appropriate vocal behavior was a primary goal of her admission.

FCT plus punishment

These conditions were the same as the FCT conditions except that each instance of problem behavior resulted in a 30-s hands-down procedure for Jay (the therapist stood behind Jay and held his hands to his sides) and a 30-s hands-down and visual-screen procedure for Betty (the therapist stood behind the child and placed one arm around the child's arms while placing the other hand over the child's eyes; Fisher, Piazza, Bowman, Hagopian, & Langdon, 1994). These particular procedures were selected because they both have empirical support (Fisher et al.) and could be implemented safely and consistently by therapists and caregivers with these children. The procedures differed for each child based on caregiver preference. Caregivers were provided with a description of nine potential punishment procedures (Fisher et al.) and were asked to select the procedure they thought would be most effective and one that they would be willing to implement consistently. Overall session length varied in this condition because the session clock was stopped each time a punishment procedure was implemented (i.e., each session represents 10 min in which all target responses could occur). Also, for Jay, a red posterboard was present during the FCT plus punishment sessions.

Data Collection and Interobserver Agreement

During all treatment analysis sessions, trained observers used laptop computers to record the frequency of problem behaviors and alternative responses. Two independent observers recorded target responses simultaneously but independently during 50% and 58% of the sessions for Jay and Betty, respectively. Mean exact agreement for problem behavior was 99% (range, 87% to 100%) and 88% (range, 56% to 100%) for Jay and Betty, respectively. Mean exact agreement for the alternative behavior was 90% (range, 88% to 100%) and 95% (range, 87% to 100%) for Jay and Betty, respectively. Frequency data also were collected during all waking hours on Jay's problem behavior on the living unit by direct-care staff using paper and pencil. These data were collected during baseline, FCT, and FCT plus punishment conditions and are reported as responses per hour.

Phase 3: Treatment Preference Evaluation

General Description

Each child's relative preference for several treatments was evaluated using a modified concurrent-chains procedure (Hanley et al., 1997). In this arrangement, three equal (fixed-ratio 1) and independent schedules were arranged for pressing one of three microswitches; these were the initial links of the chain. Responding on different-colored microswitches resulted in access to the different treatments; these were the terminal links in the chain. This procedure has been used to evaluate preference for different types or schedules of reinforcement because responding to produce access to the terminal links (reinforcing effectiveness of the terminal links) is separated from the contingencies that maintain responding in the terminal links (Catania, 1963). Three switches were available in the initial links, and three treatment procedures—FCT, FCT plus punishment, and punishment only—were available in the terminal links. Switch pressing outside a therapy room (initial links) resulted in a 2-min period inside the room (terminal links) in which the contingencies varied according to the switch that was pressed. The treatment contingencies were the same as those described in Phase 2.

Procedure

Three switches (22 cm by 14 cm), each covered with a different-colored piece of construction paper (blue, red, or white), were located on a table outside of a therapy room. Each colored switch was paired with a different treatment: the blue switch with FCT, the red switch with FCT plus punishment, and the white switch with punishment only. Pressing any switch resulted in immediate praise from the therapist (e.g., “Good pressing the red switch”) and access to the terminal link (i.e., the child entered the therapy room and experienced the treatment contingencies associated with the pressed switch for 2 min). The FCT and FCT plus punishment arrangements were similar to those described above for the treatment evaluation. The only difference between these two interventions was the presence or absence of the punishment procedure. During the punishment-only condition, problem behavior resulted in a 30-s hands-down procedure for Jay or a 30-s hands-down and visual-screen procedure for Betty; attention was otherwise unavailable. This option was included to distinguish between indiscriminate initial-link responding (represented by equal responding on all switches) and no preference between the two target treatments (represented by approximately 50% of responding to each FCT intervention) (i.e., given the results of the functional analyses, it was assumed that the child would not respond for the terminal link that was devoid of attention). The child exited the room after 2 min and was repositioned in front of the switches. This procedure was repeated until 20 min had elapsed for Jay or 10 initial-link responses were recorded for Betty. The change from the time-based to the response-based termination criterion ensured that the same number of choice opportunities would be arranged in each session (this procedural modification was introduced by Hanley et al., 1999; it occurred after Jay's assessment but before Betty's assessment). The materials in the terminal links were the same as those described for all assessment conditions (i.e., therapist, chair, and toys), except that colored posterboards corresponding to the treatment contingencies were posted in the terminal links (blue for FCT, red for FCT plus punishment, and white for punishment only).

Prior to the evaluation of treatment preference, prompted choice trials were conducted to expose the participants to the different contingencies arranged for pressing each of the switches. During each participant's first exposure session, the therapist physically guided Jay or Betty to press a switch. The order of switch pressing was determined randomly. In addition to exposing the children to the consequences for pressing each of the three switches, the contingencies also were described to Betty to facilitate discriminated switch pressing. In subsequent exposure sessions, the therapist stood behind the participant and verbally prompted him or her to press a switch once every 20 s if the participant did not press a switch independently. Exposure sessions were conducted with Jay until he pressed any of the three switches independently on five consecutive trials; this occurred in the fourth exposure session. Two 20-min exposure sessions were conducted with Betty.

Treatment preference assessment sessions then were conducted using similar procedures. Participants were physically guided to press each switch (red, blue, and white) once and contact the contingencies associated with each switch in the terminal links prior to the onset of each preference assessment session. Several controls for unwanted bias were programmed. The same therapist implemented each of the three treatments in the terminal links to insure that the procedures were implemented similarly within a session and to control for the participant pressing a switch to gain access to a particular therapist (different individuals served as therapists across sessions). The same materials also were present in the therapy room (toys, chair) for all treatments. The therapists were trained to issue all prompts (“Press the switch”) in a neutral tone of voice, to deliver all praise statements in the same tone of voice following all switch presses, and to implement attention and punishment procedures in an identical manner across treatments. Finally, the position of the switches was altered randomly after the participant pressed a switch and entered the room.

Data Collection and Interobserver Agreement

During all treatment preference evaluation sessions, two trained observers independently recorded the number of switch presses for Jay and Betty using paper and pencil. An agreement was scored if both observers recorded the same switch pressed for a given trial. An agreement coefficient was calculated for each participant's treatment preference evaluation by dividing the number of agreements by the total number of agreements plus disagreements and multiplying by 100%. Interobserver agreement was collected for 100% of the sessions for Jay and Betty and was 100%. Data were not collected on problem and alternative behaviors in the terminal links.

Results

Phase 1

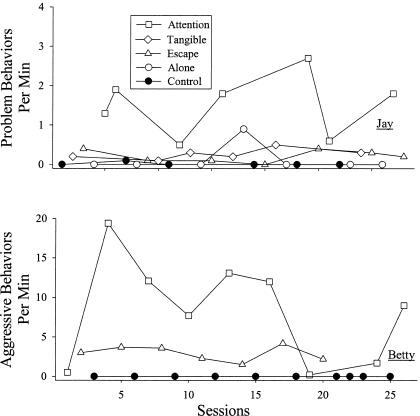

Results of the functional analyses for both participants are presented in Figure 1. Attention was the only condition in which rates of problem behavior were consistently higher than the control condition for Jay (M = 1.5 and 0.1 responses per minute, respectively), suggesting that his problem behavior was sensitive to attention as reinforcement. Betty's aggression was observed at high rates in the attention (M = 8.4) and escape (M = 2.9) conditions relative to the play condition (M = 0), suggesting both attention and escape functions. However, the treatment analyses focused exclusively on Betty's attention-maintained aggression (the escape function was addressed in another assessment not presented here).

Figure 1. Problem behaviors per minute during the functional analyses for Jay (top) and Betty (bottom).

Phase 2

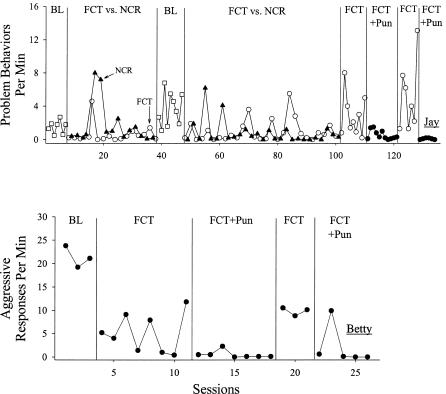

The results of the treatment analyses are presented in Figure 2. Jay engaged in a rate of problem behavior in the treatment baseline conditions (M = 1.5 responses per minute) similar to that observed in the attention condition of the functional analysis. A reduction in problem behavior was observed with both NCR and FCT; however, variable and sometimes high rates of responding were observed in both conditions (M = 1.7 for NCR, M = 0.6 for FCT). A return to baseline resulted in higher and variable rates of problem behavior (M = 3.7). The reintroduction of both interventions resulted in an overall decrease in responding from baseline (M = 0.7 for NCR, M = 0.9 for FCT); however, high rates of problem behavior were intermittently observed in both treatment conditions. The alternative response for Jay (handing a picture card to the therapist) persisted at low rates during all FCT sessions (M = 0.4, range, 0.1 to 1.1; data not shown).

Figure 2. Problem behaviors per minute during the treatment evaluations for Jay (top) and Betty (bottom).

Although both interventions resulted in similarly moderate reductions in problem behavior, FCT was implemented across the day as the primary intervention because it involved the strengthening of an adaptive behavior and allowed attention to be delivered at times when it was presumably most valuable to Jay (Hanley et al., 1997). Data collected throughout the day on the living unit showed that problem behavior was lower when FCT was in effect (M = 10.8 responses per hour) than in baseline (M = 15.4 responses per hour). Nevertheless, problem behavior persisted at unacceptable rates. An FCT baseline was then reestablished, and high and variable rates of problem behavior were observed (M = 2.8 responses per minute). FCT plus punishment resulted in a reduction in the level and variability of problem behavior (M = 0.7). High rates of problem behavior were recovered during the FCT intervention (M = 5.0), and near-zero rates of problem behavior were observed during the final FCT plus punishment condition (M = 0.3). The alternative response was emitted at variable rates throughout the FCT and FCT plus punishment conditions (Ms = 0.6 and 0.7, respectively). The FCT plus punishment intervention was implemented across the day and was associated with the lowest rates of problem behavior on the living unit (M = 3.4 responses per hour).

The results of Betty's treatment evaluation are shown in the bottom panel of Figure 2. She engaged in extremely high levels of aggression under baseline conditions (M = 21.4 responses per minute). Although an immediate reduction in aggression was observed when an alternative response resulted in attention and aggression was placed on extinction (FCT; M = 4.7), aggression continued to occur at rates above 5 per minute during 50% of FCT sessions. An immediate and sustained reduction in aggression was observed when punishment was added to the FCT intervention (M = 0.5). High levels of aggression were observed when the punishment contingency was withdrawn (M = 9.0), and low levels of aggression were recovered when the punishment contingency was reinstated (M = 0.4). The alternative response was emitted at variable rates throughout the FCT conditions; however, slightly elevated rates of the alternative response were observed during FCT plus punishment (M = 1.7) relative to FCT (M = 0.8).

In sum, function-based interventions involving differential or noncontingent reinforcement and an explicit extinction contingency resulted in reductions in problem behavior for Jay and Betty; however, problem behavior was observed intermittently at high rates under these conditions. The addition of the punishment procedures to the FCT interventions resulted in sustained low rates of problem behavior and maintenance of the alternative responses for both children.

Phase 3

The results of the treatment preference evaluation are presented in Figure 3. Throughout the evaluation, Jay allocated the majority (79.3%) of his switch presses to the FCT plus punishment intervention. A preference for FCT plus punishment emerged during Betty's evaluation, in that all switch presses were allocated to FCT plus punishment in the final five sessions. These data provide direct evidence that the function-based treatments involving punishment contingencies were more preferred (reinforcing) than similar function-based treatments involving extinction or interventions consisting of punishment alone.

Figure 3. Number of switch presses during the evaluation of preference for functional communication training (FCT), FCT combined with punishment, or punishment only for Jay (top) and Betty (bottom).

Discussion

Functional analysis results showed that the problem behavior (aggression, self-injury, and disruption) of 2 children was maintained by adult attention. Function-based treatments, which included the differential or noncontingent delivery of attention and the withholding of the same reinforcer following problem behavior (i.e., extinction), were shown to partially, but not satisfactorily, reduce problem behavior. Adding punishment contingencies to the function-based treatments resulted in sustained near-zero rates of problem behavior and maintenance of an alternative response for both participants. Finally, and perhaps most important, when the children were given the opportunity to select behavioral interventions, they chose the intervention that involved both a reinforcement contingency for alternative behavior and a punishment contingency for problem behavior.

Interventions based on a functional analysis (Iwata, Pace, Dorsey, et al., 1994) typically involve either contingent (e.g., E. G. Carr & Durand, 1985) or time-based (e.g., Vollmer, Iwata, Zarcone, Smith, & Mazaleski, 1993) delivery of maintaining reinforcers, and extinction is explicitly arranged for problem behavior (e.g., Iwata, Pace, Cowdery, & Miltenberger, 1994). Reinforcement and extinction packages have been shown to be effective in reducing problem behavior (Lalli, Casey, & Kates, 1995; Lovaas, Freitag, Gold, & Kassorla, 1965; Mazaleski, Iwata, Vollmer, Zarcone, & Smith, 1993). However, several other studies have shown that the differential delivery of the maintaining reinforcer may not be sufficient for reducing problem behavior to acceptable levels (Fisher et al., 1993; Hagopian et al., 1998; Wacker et al., 1990). These particular studies showed that the combination of function-based interventions and punishment contingencies resulted in the largest reductions in problem behavior. The results of the current study are consistent with the latter set of studies in that punishment contingencies were necessary to reduce behavior to acceptable levels.

The fact that children in the current study committed to treatment conditions involving punishment contingencies is seemingly at odds with the antiaversives movement (LaVigna & Donnellan, 1986) and the recent practice of designing positive behavioral interventions for individuals with problem behavior (E. G. Carr et al., 2002). If treatment options were restricted to those considered nonaversive or positive, the participants in the current study would have been prescribed treatments that were both ineffective and nonpreferred. These data clearly emphasize the notion that evidence-based values can and should guide the treatment-selection process.

Nevertheless, it appears somewhat counterintuitive that children would prefer conditions that involve punishment contingencies. One explanation for this preference is that the hands-down and visual-screen procedures were not actually punishment procedures. It is possible that the procedures contained elements that were similar to the attention that served as reinforcement for problem and alternative behavior (e.g., an adult approaching the child, physical contact). However, if the procedures were reinforcing, an increase in problem behavior would be expected to occur when the procedures were provided contingent on problem behavior during the FCT plus punishment conditions. This clearly was not the case (see Figure 2); therefore, the procedures and their effects satisfy the functional criteria of a punisher (Azrin & Holz, 1966). It also might be argued that the procedures reduced problem behavior by merely interrupting a burst or cluster of behavior, a process that might be less consistent with punishment. However, problem behavior did not usually appear in clusters for Jay, and the frequency of behavior clusters was reduced as were the number of instances (i.e., there were several sessions for both Jay and Betty in which no problem behaviors were observed during FCT plus punishment).

The children may have preferred FCT plus punishment if more reinforcers (20-s periods of adult attention) were delivered during the FCT plus punishment condition than the FCT condition (preference for greater overall amount of reinforcement). However, limitations of the current study, which include the lack of data collected on the number of reinforcers delivered during the treatment assessment and the lack of data collected on relevant child–therapist interactions during the terminal links of the preference assessment, prohibit complete analyses of these variables. However, because a reinforcer was scheduled to follow each alternative response, the number of alternative responses emitted during both FCT and FCT plus punishment during the treatment analysis would be suggestive of differing levels of reinforcement. Jay's data showed no difference in the rate of alternative responses emitted during FCT and FCT plus punishment (Ms = 0.6 and 0.7 responses per minute, respectively) during the treatment analysis. Betty engaged in the alternative response at higher rates during FCT plus punishment (M = 1.7) than in FCT (M = 0.8), suggesting that the higher overall level of reinforcement in FCT plus punishment experienced during her treatment analysis may have been responsible for her preference.

There was, however, a difference in the percentage of responses that resulted in reinforcement across FCT plus punishment and FCT conditions during the treatment analyses. Because problem behavior persisted during extinction for both children, only a small percentage of the children's overall responses resulted in reinforcement. But when the suppressive effects of punishment were arranged, the majority of behavior emitted resulted in reinforcement. Therefore, it seems plausible that the higher probability of reinforcement per response was responsible for the children's preference for the interventions involving punishment. Generally speaking, this suggests that the children preferred conditions in which they were more effective (or efficient). However, this explanation is merely suggested by correlational and indirect means. In other words, the higher percentage of reinforcement per response may be associated with the punishment condition, but this particular factor may not have been the variable that exerted control over children's preferences. Future research may be best directed towards determining the specific variables that control children's preference for treatments involving punishment, or other intervention components, via functional analysis (i.e., systematic manipulation of the suspected variables that control preference for a particular context).

Although children's preferences may have been a function of the increased likelihood of reinforcement per response, it is also possible that selection responses in the initial link functioned partly to avoid the FCT intervention (i.e., treatment selections may have been controlled by both the reinforcing context of FCT plus punishment and the nonreinforcing or aversive aspects of FCT plus extinction). The aversiveness of punishment procedures is presupposed; an event would not function as a punisher unless it was indeed aversive (see a recent discussion by Perone, 2003). The data in the current study suggested that the punishment procedures were sufficiently aversive to decrease problem behavior, but the context involving extinction only for problem behavior may have been more aversive than the context in which punishment was arranged for problem behavior. Hence, under some conditions it is plausible that extinction might be more aversive than punishment.

As noted earlier, FCT is a DRA procedure, and all DRA procedures necessarily involve extinction (i.e., some responses are reinforced while others are not). Therefore, selecting interventions based on their nonaversive properties may be a bit more complicated than simply discerning the presence or absence of an explicit punishment contingency. Instead of attempting to discern the appropriateness of a given intervention based on its name, structure, or presumed aversiveness, perhaps we should continue to systematically establish the effectiveness of function-based interventions and ask the consumers which interventions they prefer. The data from the present study, and the methods used to yield the data, suggest that the consumers of our interventions can and should contribute directly to the value systems that guide the treatment-selection process.

It may also be important to begin to understand the conditions in which the aversiveness of situations involving punishment is minimized. Various basic and applied studies demonstrate or suggest strategies for minimizing the aversiveness of situations involving punishment; these strategies include scheduling reinforcement for a competing response, increasing the overall density of reinforcement, and making the punishment schedule contingent, signaled, and predictable (Badia, Coker, & Harsh, 1973; Farley, 1980; Harsh & Badia, 1975; Hoffman & Fleshler, 1965; Lerman & Vorndran, 2002; MacDonald, 1973; Orne-Johnson & Yarczower, 1974; Thompson, Iwata, Conners, & Roscoe, 1999). From this, we speculate that our participants would not have chosen the intervention involving punishment if reinforcement for an intact competing response was unavailable or if the punishment procedures were noncontingent or unpredictable. However, continued research on these variables as they affect the effectiveness and value of interventions is needed. Specifically, research findings that lead to more effective punishers (Lerman & Vorndran) while minimizing the aversiveness of situations in which punishment is delivered may optimize interventions for the most intractable behavior problems, enhance their value to the persons who experience the treatments, and promote the adoption of the most effective interventions.

Acknowledgments

This investigation was supported in part by Grant MCJ249149-02 from the Maternal and Child Health Service of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Study Questions

According to the authors, what two factors might account for the apparent decrease in the use of punishment?

How were Jay's FCT and NCR conditions (a) similar and (b) different?

What punishment procedures were used, and how were they selected?

Summarize the results obtained during treatment.

Describe the concurrent-chains procedure used to assess treatment preference.

What was the purpose of the punishment-only condition during Phase 3?

Summarize participants' performance during the preference assessment.

What two factors were suggested to account for participants' selections? What data contained in the article were consistent with this account, and what additional data would have been helpful?

Questions prepared by David Wilson and Jennifer Fritz, University of Florida

References

- Azrin N.H, Holz W.C. Punishment. In: Honig W.K, editor. Operant behavior: Areas of research and application. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Badia P, Coker C.C, Harsh J. Choice of higher density signalled shock over lower density unsignalled shock. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1973;20:47–55. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1973.20-47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blampied N.M, Kahan E. Acceptability of alternative punishments. Behavior Modification. 1992;16:400–413. [Google Scholar]

- Carr E.G, Dunlap G, Horner R.H, Koegel R.L, Turnbull A, Sailor W, et al. Positive behavioral support: Evolution of an applied science. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions. 2002;4:4–16. [Google Scholar]

- Carr E.G, Durand V.M. Reducing behavior problems through functional communication training. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1985;18:111–126. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1985.18-111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr J.E, Sidener T.M. On the relation between applied behavior analysis and positive behavioral support. The Behavior Analyst. 2002;25:245–253. doi: 10.1007/BF03392062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catania A.C. Concurrent performances: A baseline for the study of reinforcement magnitude. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1963;6:299–300. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1963.6-299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farley J. Reinforcement and punishment effects in concurrent schedules: A test of two models. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1980;33:311–326. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1980.33-311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher W, Piazza C.C, Bowman L.G, Hagopian L.P, Langdon N.A. Empirically derived consequences: A data-based method for prescribing treatments for problem behavior. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 1994;15:133–149. doi: 10.1016/0891-4222(94)90018-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher W, Piazza C, Cataldo M, Harrell R, Jefferson G, Conner R. Functional communication training with and without extinction and punishment. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1993;26:23–36. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1993.26-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher W, Piazza C.C, Page T.J. Assessing independent and interactive effects of behavioral and pharmacologic interventions for a client with dual diagnoses. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 1989;20:241–250. doi: 10.1016/0005-7916(89)90029-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagopian L.P, Fisher W.W, Sullivan M.T, Acquisto J, LeBlanc L.A. Effectiveness of functional communication training with and without extinction and punishment: A summary of 21 inpatient cases. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1998;31:211–235. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1998.31-211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanley G.P, Iwata B.A, Lindberg J.S. Analysis of activity preferences as a function of differential consequences. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1999;32:419–435. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1999.32-419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanley G.P, Piazza C.C, Fisher W.W, Contrucci S.A, Maglieri K.A. Evaluation of client preference for function-based treatment packages. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1997;30:459–473. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1997.30-459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harsh J, Badia P. Choice for signalled over unsignalled shock as a function of shock intensity. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1975;23:349–355. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1975.23-349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman H.S, Fleshler M. Stimulus aspects of aversive controls: The effects of response contingent shock. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1965;8:89–96. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1965.8-89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holburn S. A renaissance in residential behavior analysis? A historical perspective and a better way to help people with challenging behavior. The Behavior Analyst. 1997;20:61–86. doi: 10.1007/BF03392765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwata B.A. The development and adoption of controversial default technologies. The Behavior Analyst. 1988;11:149–157. doi: 10.1007/BF03392468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwata B.A, Pace G.M, Cowdery G.E, Miltenberger R.G. What makes extinction work: An analysis of procedural form and function. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1994;27:131–144. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1994.27-131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwata B.A, Pace G.M, Dorsey M.F, Zarcone J.R, Vollmer T.R, Smith R.G, et al. The functions of self-injurious behavior: An experimental-epidemiological analysis. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1994;27:215–240. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1994.27-215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahng S, Iwata B.A, DeLeon I.G, Worsdell A. Evaluation of the “control over reinforcement” component in functional communication training. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1997;30:267–277. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1997.30-267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin A.E. Acceptability of alternative treatments for deviant child behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1980;13:259–273. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1980.13-259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lalli J.S, Casey S, Kates K. Reducing escape behavior and increasing task completion with functional communication training, extinction, and response chaining. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1995;28:261–268. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1995.28-261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaVigna G.W, Donnellan A.M. New York: Irvington; 1986. Alternatives to punishment: Solving behavior problems with non-aversive strategies. [Google Scholar]

- Lerman D.C, Vorndran C.M. On the status of knowledge for using punishment: Implications for treating behavior disorders. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2002;35:431–464. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2002.35-431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovaas O.I, Freitag G, Gold V.J, Kassorla I.C. Experimental studies in childhood schizophrenia: Analysis of self-problem behavior. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 1965;2:67–84. [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald L. The relative aversiveness of signalled versus unsignalled shock-punishment. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1973;20:37–46. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1973.20-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mace F.C, Lalli J.S. Linking descriptive and experimental analyses in the treatment of bizarre speech. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1991;24:553–562. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1991.24-553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazaleski J.L, Iwata B.A, Vollmer T.R, Zarcone J.R, Smith R.G. Analysis of the reinforcement and extinction components in DRO contingencies with self-injury. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1993;26:143–156. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1993.26-143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miltenberger R.G. Assessment of treatment acceptability: A review of the literature. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education. 1990;10:24–38. [Google Scholar]

- Miltenberger R.G, Suda K.T, Lennox D.B, Lindeman D.P. Assessing the acceptability of behavioral treatments to persons with mental retardation. American Journal on Mental Retardation. 1991;96:291–298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orne-Johnson D.W, Yarczower M. Conditioned suppression, punishment, and aversion. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1974;21:57–74. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1974.21-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelios L, Morren J, Tesch D, Axelrod S. The impact of functional analysis methodology on treatment choice for self-injurious and aggressive behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1999;32:185–195. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1999.32-185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perone M. Negative effects of positive reinforcement. The Behavior Analyst. 2003;26:1–14. doi: 10.1007/BF03392064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piazza C.C, Hanley G.P, Bowman L.G, Ruyter J.M, Lindauer S.E, Saiontz D.M. Functional analysis and treatment of elopement. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1997;30:653–672. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1997.30-653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piazza C.C, Hanley G.P, Fisher W.W. Functional analysis and treatment of cigarette pica. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1996;29:437–450. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1996.29-437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson R.H, Fisher W.W, Piazza C.C, Kuhn D.E. The evaluation and treatment of aggression maintained by attention and automatic reinforcement. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1998;31:103–116. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1998.31-103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson R.H, Iwata B.A, Conners J, Roscoe E.M. Effects of reinforcement for alternative behavior during punishment of self-injury. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1999;32:317–328. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1999.32-317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Houten R, Axelrod S, Bailey J.S, Favell J.E, Foxx R.M, Iwata B.A, et al. The right to effective behavioral treatment. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1988;21:381–384. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1988.21-381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vollmer T.R, Iwata B.A, Zarcone J.R, Smith R.G, Mazaleski J.L. The role of attention in the treatment of attention-maintained self-injurious behavior: Noncontingent reinforcement and differential reinforcement of other behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1993;26:9–21. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1993.26-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vollmer T.R, Northup J, Ringdahl J.E, LeBlanc L.A, Chauvin T.M. Functional analysis of severe tantrums displayed by children with language delays: An outclinic assessment. Behavior Modification. 1996;20:97–115. [Google Scholar]

- Wacker D.P, Steege M.W, Northup J, Sasso G, Berg W, Reimers T, et al. A component analysis of functional communication training across three topographies of severe behavior problems. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1990;23:417–429. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1990.23-417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitney-Thomas J, Shaw D, Honey K, Butterworth J. Building a future: A study of student participation in person-centered planning. Journal of the Association for Persons with Severe Handicaps. 1998;23:119–133. [Google Scholar]