Abstract

This study examined packing (pocketing or holding accepted food in the mouth) in 3 children who were failing to thrive or had inadequate weight gain due to insufficient caloric intake. The results of an analysis of texture indicated that total grams consumed were higher when lower textured foods were presented than when higher textured foods were presented. The gram intake was related directly to levels of packing. That is, high levels of packing were associated with higher textured foods and low gram intake, and low levels of packing were associated with lower textured foods and high gram intake. All participants gained weight when texture of foods was decreased. Packing remained low during follow-up for 2 participants even when the texture of food was increased gradually over time. These data are discussed in relation to avoidance, response effort, and skill deficit.

Keywords: avoidance, packing, pediatric feeding disorders, texture assessment

Packing (pocketing or holding accepted food in the mouth) has the potential to cause significant health problems in the form of failure to thrive, malnutrition, or dehydration if the packing behavior results in inadequate intake. Aspiration of ingested food (Byard et al., 1996) is another serious risk that is associated with packing. Aspiration may be more likely when children are presented with textures that are inappropriate for their oral motor skills. Aspiration of ingested food may result in chronic coughing and choking, pneumonia, chronic lung disease, airway obstruction, and even death. Despite the potentially serious consequences of packing, it is a behavior problem that has received very little attention in the literature on pediatric feeding disorders.

Riordan, Iwata, Wohl, and Finney (1980) noted anecdotally that packing emerged during implementation of differential reinforcement of acceptance (providing the child with access to preferred food and social praise following acceptance of bites of nonpreferred food or sips of liquid). Therefore, the contingency was altered so that the child was required to swallow the bites or sips to receive reinforcement. However, it is not clear from the data if this change in the contingency resulted in reduced packing, because no data on packing were presented.

Similarly, Sevin, Gulotta, Sierp, Rosica, and Miller (2002) observed that packing emerged during the course of treatment for 1 child's feeding disorder. The authors used nonremoval of the spoon to increase acceptance. However, increases in acceptance were accompanied by increases in expulsion. Treatment of expulsion (re-presenting expelled food) was associated with the emergence of packing. The authors treated packing with a redistribution procedure (placing the food back on the tongue). The authors proposed that inappropriate behavior (e.g., head turning, blocking and batting at the spoon), expulsion, and packing comprised a response class of behavior maintained by negative reinforcement in the form of escape from or avoidance of eating. Thus, redistribution (the treatment for packing) was conceptualized as an escape-extinction procedure. However, the functions of inappropriate behavior, expulsion, and packing were not determined. The Sevin et al. paper was important because it was one of the first studies to operationally define and treat packing systematically. The data from this study suggested that a consequence-based treatment could be used to reduce packing.

Given the dearth of literature on the treatment of packing and the potential severity of its consequences, it appears that investigations examining additional treatment strategies are warranted. One potential alternative to the consequence-based redistribution procedure described by Sevin et al. (2002) is a procedure based on manipulation of antecedents. There are some data in the literature to suggest that antecedent variables may have effects on food refusal and related behavior. For example, Munk and Repp (1994) presented different types and textures of food to 5 children with feeding disorders. The results of this assessment indicated that both type and texture of food influenced the extent to which children accepted and expelled food.

Patel, Piazza, Santana, and Volkert (2002) extended the work of Munk and Repp (1994) by demonstrating that the results of the assessment of type and texture could be used to prescribe treatment. An assessment of type and texture suggested that expulsion occurred more often with meats compared to other foods (fruits, vegetables, and starches). Decreasing the texture of meats, but not the other foods, resulted in decreased expulsion. It is unclear from these data whether expulsion of meats was a part of a class of refusal behavior or whether another variable may have been responsible for this type of selective expulsion. The authors indicated that the response effort associated with consuming meats may be higher than consuming other foods. It is likely that once the response effort was decreased (i.e., decreasing the texture) expulsion also decreased. The Munk and Repp and Patel et al. studies demonstrated how manipulations of texture affected acceptance and expulsion. These data raise the possibility that similar manipulations may be effective for treatment of packing.

Although packing may be conceptualized as part of the same response class as other refusal behavior (e.g., head turning, blocking the spoon, expulsion), there may be another explanation for the emergence of this behavior. It is likely that children with feeding problems pack food because they do not have the appropriate oral motor skills to consume higher textured foods. That is, higher textures of food may require different or more advanced oral motor skills (e.g., chewing, tongue lateralization) relative to lower textures (Logemann, 1983). Typical eaters follow a progression of consuming consistencies that includes a liquid diet only (infants under 3 to 4 months), followed by introduction of cereals and baby foods at 4 to 6 months, chewing biscuits and soft solids at 6 to 9 months, and finally table-texture foods at 12 to 14 months (or commensurate with eruption of teeth). Experience with one consistency of liquid or solid aids in the development of appropriate oral motor skills necessary to process food at the next consistency (Morris & Klein, 2000). Early or late introduction of these steps (e.g., introducing solids too early or too late) may result in medical or behavioral feeding problems (Brown, Black, Lopez de Romana, & Creed de Kanashiro, 1989; Christophersen & Hall, 1978; Kleinman, 2000). Thus, it is more likely that children with a history of feeding problems who are inexperienced eaters have not developed the skills to process coarser textures (Christophersen & Hall), even though these higher textures would be appropriate or typical based on the child's chronological age. Parents may introduce textures according to their child's chronological age rather than their history of oral intake. This may result in problems such as expulsion and packing in children who are inexperienced eaters. Therefore, evaluation of the appropriateness of texture for individual children is critical from both medical and behavioral perspectives.

In the current investigation, we identified 3 children who had been presented with table-texture foods that were appropriate based on their chronological age. However, all of the children exhibited low oral intake and food refusal that were associated with failure to thrive or inadequate weight gain. Therefore, we evaluated the effects of texture on the packing and caloric consumption in these children.

Method

Participants and Setting

Three children who had been diagnosed with a pediatric feeding disorder participated in this study. All 3 children had been admitted to an intensive pediatric feeding disorders day-treatment program for poor oral intake. Children were included in this study if (a) their parents presented them with higher textures prior to admission, (b) the parents reported that packing was problematic, and (c) the higher textures did not appear to be appropriate relative to the child's oral motor skills based on observations conducted by the occupational therapist. Dylan was a 3-year-old boy who had been diagnosed with gastroesophageal reflux (GER), failure to thrive (FTT), asthma, and developmental delays. Caden was a 4-year-old boy who had been diagnosed with GER and autism. Although Caden was not diagnosed with FTT, his weight for height was at the 10th percentile, and he had not gained weight over the past year. Jasper was a 4-year-old boy who had been diagnosed with GER, FTT, bronchopulmonary dysplasia, and developmental delays. Caden was taking Prilosec® and Jasper was taking Prilosec® and Reglan® for GER during the entire admission. All 3 children were deemed ready for oral consumption of liquids and solids based on an interdisciplinary evaluation of their feeding skills.

All children consumed small amounts of table food prior to admission; however, none of the children ate a sufficient quantity to gain weight or grow (as evidenced by their FTT or low weight). The cause of each child's insufficient oral intake was unclear at the time of the admission; however, medical causes of their growth insufficiencies (e.g., hormonal or genetic, malabsorption) had been evaluated and ruled out. According to the occupational therapist, even though presentation of table-texture foods was appropriate based on the participants' ages, it did not appear that they had the oral motor skills to consume regular table-texture foods. That is, the occupational therapist described each of the children as having low oral tone, inability to lateralize food, and immature chewing patterns. The occupational therapist recommended an assessment of various textures because the most appropriate texture for each child was not clear at the time of admission. The goal of the assessment was to determine the highest texture that could be consumed safely and effectively by each child while sufficient caloric intake was maintained.

All sessions were conducted in a room with a one-way mirror. A highchair, food, utensils, and toys (as described below) were present during all sessions.

Dependent Variables and Data Collection

The major dependent variables were packing and total grams consumed. Packing was defined as any food larger than a size of a pea in the child's mouth 30 s (Dylan and Jasper) or 15 s (Caden) after acceptance. For Caden we used 15 s rather than 30 s to check for packing because Caden's mother wanted him to be presented with as many bites as possible. Therefore, if Caden had swallowed the bite after 15 s, we were able to present the next bite more rapidly (and thus present more total bites in the session) than if we had checked at 30 s. Acceptance was defined as the entire bite of food entering the child's mouth. Data on packing were collected on laptop computers using an event-recording procedure. Packing was converted to a percentage by dividing the number of occurrences by the number of acceptances multiplied by 100%. All food was weighed before and after each session. Premeal minus postmeal food weights were used to calculate total grams consumed. Data also were collected on inappropriate behavior (i.e., head turns, blocks, bats, negative vocalizations), expulsion, and vomiting, but these behaviors remained low for the 3 participants for the duration of the analysis.

A second observer independently scored 13%, 23%, and 30% of sessions for Dylan, Caden, and Jasper, respectively. Interobserver agreement for acceptance and packing was calculated by dividing the smaller frequency by the larger frequency multiplied by 100%. The mean total interobserver agreement for acceptance was 93% (range, 74% to 100%) for Dylan, 92% (range, 76% to 100%) for Caden, and 98% (range, 95% to 100%) for Jasper. The mean total interobserver agreement for packing was 100% for Dylan, 100% for Caden, and 99% (range, 98% to 100%) for Jasper. Interobserver agreement data were not collected for total grams consumed because an automated scale was used to collect data.

Experimental Design and Procedure

A reversal design was used to evaluate the effects of texture on packing and total grams consumed. Texture changes were evaluated in a reversal design. The parents were instructed to identify four foods from each food group (fruits, vegetables, starches, and proteins) that they wanted their child to eat after treatment, and these foods were used throughout the analysis. A food preference assessment was not conducted prior to the evaluation because the parents indicated that their children packed all foods. In addition, analysis of the data by food type from the texture assessment did not indicate that one food was packed more often than another.

Four foods, one from each food group, were presented in each session. The order of food presentation was selected randomly prior to the session; however, the order of presentation remained the same within a given session. Foods were presented at puree (i.e., regular table foods placed in a blender and blended until smooth) and wet ground (i.e., pureed foods with small chunks) textures for Dylan. Caden was presented with puree, wet ground, and baby food (i.e., jarred Gerber® Stage 2 foods) textures. Foods were presented at puree and chopped (i.e., regular table foods chopped into small pieces) textures for Jasper. Selection of textures was based on the recommendations of the occupational therapist. Individualized treatments were developed for each participant based on the results of previous assessments, recommendations from the parents and interdisciplinary team, and individual skills or characteristics of the child (e.g., some children were self-feeders and others were not). These individualized treatments were used during the texture assessment.

Five session blocks were conducted each day (i.e., session blocks were conducted five times per day) with approximately three to four 5-min sessions (15 to 20 min of total eating time) per session block (for a total of 15 to 20 sessions per day) for Dylan and Caden. Two to three 10-min sessions (20 to 30 min of total eating time) per session block were conducted for Jasper. The session may have exceeded 5 or 10 min for Dylan and Jasper because they were required to swallow the last bite presented before the session was terminated. However, sessions were terminated after 45 min, even if they did not swallow the last bite. Food was removed from Caden's mouth if he had not swallowed the bite within 5 min. This procedure was used with Caden because data from previous assessments showed that he held food in his mouth for up to 20 min, and the occupational therapist was concerned that packing food for extended durations increased the risk of choking or aspiration.

Dylan

The therapist presented a bite approximately every 30 s from the initial acceptance. Brief praise was delivered if Dylan accepted the bite within 5 s. The bite remained at Dylan's lips until it was accepted (nonremoval of the spoon). If Dylan expelled the bite (i.e., spit the food out), it was scooped up and re-presented for 30 s. The next bite was presented (after the initial 30 s) if the previous bite was in Dylan's mouth for at least 3 s. No differential consequences were provided for vomiting (i.e., bite presentation continued). The therapist checked inside Dylan's mouth every 30 s to determine whether the bite was swallowed. If Dylan packed the bite, the therapist used a bristled massaging toothbrush to facilitate a swallow response. The food was placed back on the tongue with the brush. In addition, the therapist delivered a verbal prompt to swallow (i.e., “Dylan, you need to swallow your bite”). This procedure was repeated every 30 s if food remained in Dylan's mouth. Praise was delivered if he swallowed the bite within 30 s of acceptance. Toys were available continuously. All inappropriate behavior (i.e., head turns, blocks, bats, negative vocalizations) was blocked or ignored. The next bite was presented immediately after the previous bite had been swallowed (after the initial 30 s).

Upon discharge, Dylan's parents presented him with pureed foods during all meals. However, during follow-up visits we attempted to increase the texture. Advances in texture were conducted by mixing pureed foods and wet ground foods together (Shore, Babbitt, Williams, Coe, & Snyder, 1998). This mixture was presented at home for a few months prior to conducting sessions with wet ground food alone. Systematic data were not collected during this process. Dylan's mother conducted all sessions during follow-up visits in the clinic. During the 3-month follow-up visit, wet ground foods alone were presented using the protocol described above. For 6- and 9-month follow-up visits, Dylan fed himself regular table-texture foods. At home the family continued to present Dylan with regular textured table foods in conjunction with some wet ground foods after the 6- and 9-month follow-up visits. During the 12-month follow-up visit, Dylan was presented with a meal for 30 min. His meal consisted of a half portion of regular table-texture foods and a half portion of foods at a wet ground texture.

Caden

All procedures with Caden were identical to the ones used with Dylan except (a) bites were presented approximately every 15 s from the initial acceptance, (b) a brush was not used, (c) the therapist interacted with Caden throughout the session but no toys were present, (d) expelled bites were re-presented until they were swallowed, and (e) the next bite was presented after the previous bite had been swallowed (after the initial 15 s). Upon discharge, Caden's parents were instructed to present him with pureed foods for all meals. Follow-up data were not collected for Caden because his family opted not to participate in our follow-up program.

Jasper

The therapist placed a bite in a bowl approximately every 30 s from the initial acceptance. Brief praise was delivered if Jasper fed himself the bite (i.e., picked up the bite with his fingers or a fork and placed it in his mouth) within 30 s. If Jasper did not feed himself the bite within 30 s, the therapist implemented a physical prompt (i.e., guiding his hand to the spoon and bringing it to his mouth). The spoon remained at his lips until the bite was accepted. If Jasper expelled the bite, it was scooped up and placed back in the bowl. Jasper had 30 s to put the food back into his mouth. If he did not do so, the physical prompt was initiated. The next bite was presented after the previous bite had been swallowed (after the initial 30 s). No differential consequences were provided for vomiting (i.e., bite presentation continued). If Jasper packed the bite, the therapist delivered a verbal prompt to swallow (i.e., “Jasper, you need to swallow your bite”). Praise was delivered if Jasper swallowed the bite within 30 s of acceptance. In addition, Jasper had access to preferred toys for 20 s if he swallowed the bite within 30 s of acceptance (Patel, Piazza, Martinez, Volkert, & Santana, 2002). All inappropriate behavior (i.e., dumping food, throwing, banging on the tray, hitting or kicking the therapist) resulted in a hands-down procedure (we held Jasper's hands) for 20 s. If the hands-down procedure was being implemented, the therapist used a non-self-feeder protocol (the therapist presented the bite on a spoon to Jasper's lips and the spoon remained at his lips until he accepted the bite).

Upon discharge, the family was instructed to present Jasper with pureed foods for all meals. However, during follow-up visits we attempted to increase the texture. Texture was advanced using a procedure similar to that described by Shore et al. (1998). Jasper's mother conducted sessions using the protocol described above during 3-, 6-, and 9-month follow-up visits in the clinic. Jasper was consuming regular table-texture foods using the protocol developed in the day-treatment program during all follow-up visits.

Results

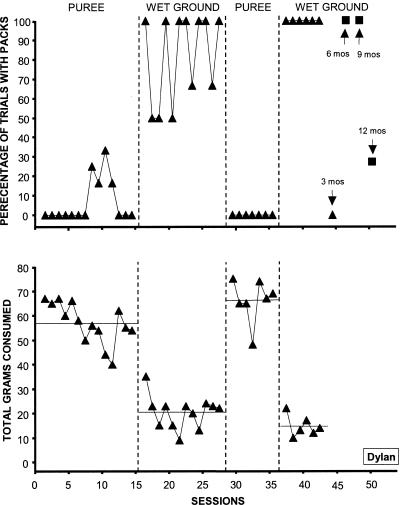

Packing for Dylan (Figure 1, top) was low when foods were presented at a pureed texture and high when foods were presented at a wet ground texture. Total grams consumed (Figure 1, bottom) were higher with pureed (M = 60.5 g) than with wet ground (M = 18.5 g) foods. In addition, packing remained at zero during 3-month follow-up when the texture was advanced to wet ground; however, packing increased to 100% when regular table food probes were conducted at 6- and 9-month follow-up visits (data not shown). At 6- and 9-month follow-ups, Dylan did not appear to display the appropriate oral motor skills (i.e., chewing) needed to consume regular table foods. Therefore, the family was instructed to continue to present food at a wet ground texture. Packing decreased during the 12-month follow-up visit when regular table foods were presented (data not shown). Total grams consumed remained low during regular table food probe sessions at 6- and 9-month follow-ups (data not shown). In addition, Dylan's weight increased substantially from the day-treatment admission (11.8 kg) to the 12-month follow-up (15.7 kg).

Figure 1. Percentage of trials with packing (top panel) and total grams consumed (bottom panel) for Dylan.

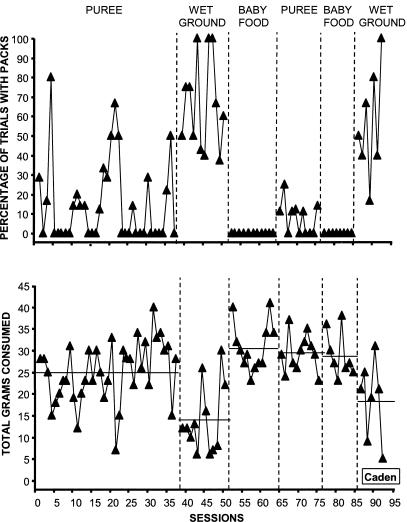

Packing for Caden (Figure 2, top) was variable and high when foods were presented at a wet ground texture. However, packing was generally low when baby food and puree textures were presented. Total grams consumed (Figure 2, bottom) were higher and more stable when baby food (M = 30.1 g) and pureed foods (M = 29.4 g) were presented than when wet ground foods were presented (M = 15.7 g). In addition, Caden's weight increased steadily during his admission. Caden weighed 17.8 kg at admission; after 5 weeks, he weighed 18.4 kg.

Figure 2. Percentage of trials with packing (top panel) and total grams consumed (bottom panel) for Caden.

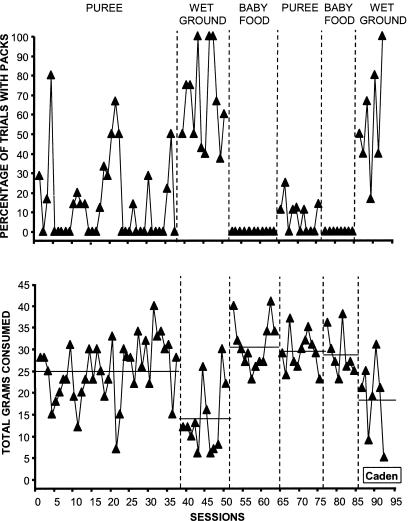

Packing for Jasper (Figure 3, top) was high and variable when foods were presented at a chopped texture. However, packing remained low when foods were presented at a pureed texture. Total grams consumed (Figure 3, bottom) were higher when pureed foods (M = 63.5 g) were presented than when chopped foods were presented (M = 27.3 g). During all follow-up visits packing remained relatively low, and total grams consumed remained high (data not shown). In addition, Jasper's weight increased steadily from admission (12.2 kg) to 9-month follow-up (14.2 kg).

Figure 3. Percentage of trials with packing (top panel) and total grams consumed (bottom panel) for Jasper.

Discussion

The results from the current investigation showed that higher textures were associated with higher levels of packing and lower levels of gram intake. Thus, packing has the potential to be a life-threatening problem if it results in inadequate intake, as shown in the current investigation. All participants were failing to thrive or had inadequate weight gain as a result of their low intake. Despite the potential negative consequences of packing, only one study in the literature operationally defined and systematically treated the packing of 1 participant (Sevin et al., 2002). Therefore, the results of the current investigation are important in that they add to the almost nonexistent literature on packing. These data also are important because altering the texture of food may be a relatively easy way to treat such a serious problem. The positive effects of treatment were evidenced by the fact that all participants in the current investigation gained weight over the course of treatment.

The reason that packing emerges is unclear. Sevin et al. (2002) hypothesized that packing was part of a response class of behaviors maintained by negative reinforcement in the form of escape from or avoidance of eating. The hypothesis that feeding problems are maintained by negative reinforcement has been supported by the results of treatment studies in which procedures targeted to prevent escape from eating (e.g., nonremoval of the spoon, Cooper et al., 1995; Hoch, Babbitt, Coe, Krell, & Hackbert, 1994; Patel, Piazza, Martinez, Volkert, & Santana, 2002; physical guidance, Ahearn, Kerwin, Eicher, Shantz, & Swearingin, 1996; Piazza, Patel, Gulotta, Sevin, & Layer, 2003) have been effective in increasing acceptance and decreasing refusal behavior. Sevin et al. hypothesized further that packing may be part of a chain of negatively reinforced behaviors that emerge during the treatment of food refusal. In the Sevin et al. investigation, a treatment targeting acceptance (nonremoval of the spoon) was associated with the emergence of expulsion. Subsequently, treatment for expulsion resulted in emergence of packing.

In the current investigation, packing was associated with higher textures rather than treatment of refusal, suggesting that packing may not necessarily occur as part of a chain of behaviors. All 3 children accepted all bites presented regardless of the texture, and other inappropriate behavior remained low throughout the analysis. If packing was maintained by negative reinforcement in the form of avoidance of eating, it should occur across all textures, regardless of the ease or difficulty of packing a particular texture. However, in the current study packing was associated with higher textures only.

Higher textured foods may function as an establishing operation based on a child's history with higher textures. Shore et al. (1998) and Patel, Piazza, Santana, and Volkert (2002) proposed that higher textured food may function as a conditioned aversive stimulus if it has been paired with gagging or vomiting in the past. That is, some children may hold food (particularly higher textures) in their mouth to avoid choking or gagging.

Alternatively, packing may be a function of the response effort required to consume higher textures. Kerwin, Ahearn, Eicher, and Burd (1995) evaluated the effects of response effort on eating by manipulating spoon volume systematically. Kerwin et al. showed that levels of acceptance varied as a function of spoon volume (e.g., higher levels of acceptance were associated with lower spoon volumes). The data from Kerwin et al. may be relevant to the current investigation in that different levels of response effort may be required to consume different textures of foods, and these changes in response effort may alter eating behavior. More specific to the current investigation, as the response effort for eating increases with the higher textures, the likelihood of packing also may increase.

Finally, a child may pack food because he or she lacks the prerequisite skills (e.g., tongue lateralization, chewing) necessary to consume higher textured foods (Christophersen & Hall, 1978; Logemann, 1983). That is, the child may not be physically capable of processing (i.e., chewing and swallowing) higher textured foods. In this case, presentation of higher textures may be associated with the additional risk of aspiration (Byard et al., 1996; Shore et al., 1998). This explanation should be viewed with caution because the recommendations from the occupational therapist regarding texture were based on her observations of the children's skills during meals rather than a formal oral motor evaluation.

Even though the lower textures presented to the children in the current investigation were not appropriate based on chronological age, the data suggested that altering texture may be an appropriate treatment for a number of reasons. Manipulations of texture were associated with changes in volume of consumption. Each of these children was at risk for placement of a gastrostomy tube as a result of their inadequate growth. Lowering texture resulted in increases in caloric intake, avoidance of surgery, and weight gain. Second, for some children higher textures may present an additional risk of aspiration if the child lacks the appropriate oral motor skills to manage the food appropriately. Third, altering texture is a relatively simple task that can be accomplished prior to the start of the meal and does not require any within-meal manipulations. Finally, the results from the current investigation showed that higher textured foods that were more appropriate for the child's chronological age were reintroduced successfully over time for Dylan and Jasper. Anecdotally, it was observed that Dylan's and Jasper's oral motor skills did improve over time. For example, both children began chewing their food and lateralizing the tongue. These were skills that were not evident at the beginning of the evaluation.

One limitation of this study is that texture changes were not evaluated in isolation. Because escape extinction was implemented with all participants, it is unclear whether the same results would have been achieved without the use of escape extinction. Because escape extinction was implemented from the onset of the analysis, it is likely that escape extinction did not affect the results. Escape extinction was necessary to increase acceptance, but once acceptance increased, packing was observed. Therefore, it did not seem appropriate to conduct the texture evaluations in the absence of escape extinction.

Future studies should develop both assessments and treatments for packing. An important first step would be to develop a procedure to assess the function of packing, because different forms of treatment would be indicated based on the function of the behavior (Iwata, Dorsey, Slifer, Bauman, & Richman, 1982/1994). In addition, such an assessment may help to discriminate between motivational and skill deficits that may contribute to packing. Treatments that target motivational issues might include procedures based on positive reinforcement, negative reinforcement, or punishment. Even though positive reinforcement has not been consistently effective in treatment of acceptance, it is not clear how effective it would be for treatment of packing. Sevin et al. (2002) showed that a putative escape-extinction procedure (redistribution) reduced the packing of 1 participant; however, they suggested that redistribution also may function as punishment. Future studies should examine the effectiveness of redistribution with additional participants and compare its effectiveness with other procedures.

Finally, it is unclear if lowering texture has any long-term detrimental effects on a child's oral motor-skill development. For example, if a child has some emerging chewing skills, will lowering the texture of food extinguish those skills? In the current investigation, we were able to increase the texture for 2 participants, but future investigations should examine the relation of texture and chewing. If packing is related to a skill deficit and the child cannot consume higher textures safely (i.e., is at risk of aspiration when consuming higher textures), then treatments should be developed to train the child in the appropriate skills needed to consume higher textures.

Acknowledgments

This investigation was supported in part by Grant 1 K24 HD01380-01 received by the second author from the Department of Health and Human Services, the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

Study Questions

What is packing, and why is it a problem?

What are two hypotheses for the emergence of packing?

What were the inclusion criteria for participation in the study?

What were the primary target behaviors, and how were they measured?

Briefly describe the consequences for (a) acceptance of food and (b) food packing.

Summarize the results obtained for each child.

How did the authors justify presenting children with foods at textures lower than those appropriate for the children's chronological age?

What is a potentially detrimental effect of presenting a child with lower textured foods?

Questions prepared by Leah Koehler and Pamela Neidert, University of Florida

References

- Ahearn W.H, Kerwin M.E, Eicher P.S, Shantz J, Swearingin W. An alternating treatments comparison of two intensive interventions for food refusal. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1996;29:321–332. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1996.29-321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown K.H, Black R.E, Lopez de Romana G, Creed de Kanashiro H. Infant feeding practices and their relationships with diarrheal and other diseases. Pediatrics. 1989;83:31–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byard R.W, Gallard V, Johnson A, Barbour J, Bonython-Wright B, Bonython-Wright D. Safe feeding practices for infants and young children. Journal of Pediatrics and Child Health. 1996;32:327–329. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.1996.tb02563.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christophersen E.R, Hall C.L. Eating patterns and associated problems encountered in normal children. Issues in Comprehensive Pediatric Nursing. 1978;3:1–16. doi: 10.3109/01460867809087345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper L.J, Wacker D.P, McComas J, Brown K, Peck S.M, Richman D, et al. Use of component analysis to identify active variables in treatment packages for children with feeding disorders. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1995;28:139–153. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1995.28-139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoch T.A, Babbitt R.L, Coe D.A, Krell D.M, Hackbert L. Contingency contacting: Combining positive reinforcement and escape extinction procedures to treat persistent food refusal. Behavior Modification. 1994;18:106–128. doi: 10.1177/01454455940181007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwata B.A, Dorsey M.F, Slifer K.J, Bauman K.E, Richman G.S. Toward a functional analysis of self-injury. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1994;27:197–209. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1994.27-197. (Reprinted from Analysis and Intervention in Developmental Disabilities, 2, 3-20, 1982) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerwin M.E, Ahearn W.H, Eicher P.S, Burd D.M. The costs of eating: A behavioral economic analysis of food refusal. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1995;28:245–260. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1995.28-245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinman R.E. Complementary feeding and later health. Pediatrics. 2000;106:1287–1288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logemann J.A. Evaluation and treatment of swallowing disorders. San Diego, CA: College-Hill Press; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Morris S.E, Klein M.D. Normal development of feeding skills. In: Morris S, Klein M, editors. Pre-feeding skills. Tucson, AZ: Therapy Skill Builders; 2000. pp. 59–95. [Google Scholar]

- Munk D.D, Repp A.C. Behavioral assessment of feeding problems of individuals with severe disabilities. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1994;27:241–250. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1994.27-241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel M.R, Piazza C.C, Martinez C.J, Volkert V.M, Santana C.M. An evaluation of two differential reinforcement procedures with escape extinction to treat food refusal. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2002;35:363–374. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2002.35-363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel M.R, Piazza C.C, Santana C.M, Volkert V.M. An evaluation of food type and texture in the treatment of a feeding problem. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2002;35:183–186. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2002.35-183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piazza C.C, Patel M.R, Gulotta C.S, Sevin B.S, Layer S.A. The relative contribution of positive reinforcement and escape extinction in the treatment of food refusal. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2003;36:309–324. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2003.36-309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riordan M.M, Iwata B.A, Wohl M.K, Finney J.W. Behavioral treatment of food refusal and selectivity in developmentally disabled children. Applied Research in Mental Retardation. 1980;1:95–112. doi: 10.1016/0270-3092(80)90019-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sevin B.M, Gulotta C.S, Sierp B.J, Rosica L.A, Miller L.J. Analysis of response covariation among multiple topographies of food refusal. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2002;35:65–68. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2002.35-65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shore B.A, Babbitt R.L, Williams K.E, Coe D.A, Snyder A. Use of texture fading in the treatment of food selectivity. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1998;31:621–633. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1998.31-621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]