Abstract

Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) is the leading cause of disability worldwide, affecting 3.8% of the global population. Despite its prevalence, less than half of those diagnosed with MDD receive treatment and remission rates remain low. Given these poor outcomes for individuals with depression and the findings of our previous study examining the role of certain psychological phenomena on the incidence of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), the present study aims to examine whether intolerance of uncertainty, perfectionism, and coping strategies can together predict the diagnosis and severity of MDD. Participants were outpatients (N = 549) referred to a tertiary care clinic in Toronto, Canada between 2011 and 2014. After undergoing a diagnostic assessment, participants were administered a series of self-report questionnaires that measured intolerance of uncertainty, perfectionism, and coping. Results demonstrate that task-oriented coping and emotion-oriented coping significantly predicted depression diagnosis, while avoidant coping, perfectionism, and intolerance of uncertainty did not. As for depression severity, significant predictors included perfectionism, task-oriented coping, emotion-oriented coping, and avoidant coping. Further research is needed to identify interactions between the subscales of these constructs to determine how they work in tandem to influence MDD. Our findings indicate a need for more personalized interventions in the treatment of this disorder.

Keywords: Major depressive disorder, Intolerance of uncertainty, Perfectionism, Task-oriented coping, Emotion-oriented coping, Avoidant coping

Highlights

-

•

Intolerance of uncertainty, perfectionism, and coping strategies may predict the diagnosis and severity of depression.

-

•

Avoidant coping, perfectionism, and intolerance of uncertainty did not predict depression diagnosis.

-

•

Task-oriented coping and emotion-oriented coping significantly predicted depression diagnosis.

-

•

Task-oriented, emotion-oriented, and avoidant coping, plus perfectionism, significantly predicted depression severity.

1. Introduction

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is the leading cause of disability worldwide, affecting 3.8% of the global population [1]. Despite the high prevalence and consequences of MDD, less than half of those diagnosed with depression receive treatment [2], and among those that do, remission rates remain low, leaving as many as 30–40% seeking second- and third-line treatments before being deemed treatment resistant [3]. Identifying risk factors involved in the development of MDD may be crucial to improving treatment outcomes. In a previous study, we examined the influence of intolerance of uncertainty, perfectionism, and coping styles on the incidence of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). The findings from this study suggest that perfectionism, coping styles, and intolerance of uncertainty predict both the diagnosis and severity of OCD, which may allow clinicians to predict features of OCD prior to a diagnosis [4]. The present study investigates these same factors in a population with MDD. Intolerance of uncertainty, perfectionism, and coping styles may provide for a particular risk for the development of MDD and therefore influence treatment outcomes. While there is research examining, individually, the relationship of each construct with depression, there is little knowledge on how, together, they may predict the diagnosis and severity of MDD.

1.1. Intolerance of uncertainty

Intolerance of Uncertainty (IU) refers to the emotional, cognitive, and behavioural reactions to uncertain situations that arise from negative beliefs about uncertainty and its implications [5]. As a transdiagnostic construct, IU has been implicated in various mental disorders, including generalized anxiety disorder, social anxiety disorder [6], [7], obsessive-compulsive disorder [4], [8], and major depressive disorder [9]. The construct consists of two dimensions: (i) prospective IU (i.e., desire for predictability and engagement in strategies to increase certainty) and (ii) inhibitory IU (i.e., impaired functioning and avoidance when faced with uncertainty) [10]. Researchers have postulated that inhibitory IU leads to depressive predictive certainty, which refers to the tendency to overestimate the likelihood of the occurrence of negative events [11], [12]. While this pessimistic outlook on the future appears less distressing than having to live with uncertainty, it ultimately may foster feelings of hopelessness and exacerbate depressive symptoms [13], [14]. Moreover, prospective IU, although less strongly associated with depression, also contributes to depressive symptoms, as it is thought to mediate the relationship between depression and reduced sensitivity to reward [15]. Therefore, both dimensions of the IU construct might play a role in the development and course of MDD.

A number of studies have found that the association between depression and IU is fully mediated by rumination [16], [17], [18]. Much like inhibitory IU, rumination may give rise to depressive predictive certainty when faced with an uncertain situation, leading to hopelessness and an increased vulnerability to depression [18]. Individuals with a strong tendency to ruminate may recall negative memories associated with uncertain situations more readily, reinforcing their belief that negative outcomes will occur in future uncertain events [17]. Due to their excessive focus on the distress associated with uncertainty, these individuals also tend to have fewer coping strategies and sources of social support to help them deal with uncertainty in adaptive ways [17]. Lastly, IU also influences treatment outcomes: reductions in IU from pre- to post-treatment with cognitive behavioural therapy have been associated with decreases in depressive symptom severity [19].

1.2. Perfectionism

Perfectionism can be defined as a scheme for self-evaluation that is overly dependent on achieving high personal standards in self-relevant domains, resulting in continuous striving to meet those standards in spite of negative consequences [20]. Although perfectionism can lead to positive behaviours, such as resourcefulness [21], it has also been associated with feelings of failure [22], anxiety [23], and depression [24]. [22] proposed three domains from which perfectionism can be measured: other-oriented, self-oriented, and socially prescribed perfectionism. Other-oriented perfectionism involves unrealistic and exaggerated expectations of others, whereas self-oriented perfectionism involves intense self-scrutiny, self-criticism, and the inability to accept flaws or failure within oneself. Socially prescribed perfectionism, however, is the belief that others hold unrealistic expectations of oneself [22]. Unlike other-oriented and self-oriented perfectionism, socially prescribed perfectionism has an external source and is therefore perceived to be out of one’s control [22].

Of these three domains, socially prescribed perfectionism has been most closely linked with depressive symptoms, though self-oriented perfectionism is also a moderate predictor of depression [25]. [26] theorized that extreme socially prescribed perfectionism may lead to a sense of learned helplessness due to a perceived discrepancy between one’s actual abilities and the unrealistic expectations of others. In line with this theory, one longitudinal study found that individuals high on socially prescribed perfectionism perceive ongoing disappointment and disapproval from others and expect failure in future interpersonal relationships, creating a sense of helplessness and an increased vulnerability to depressive symptoms [27]. Moreover, perfectionism not only contributes to the development of depression but also hinders treatment outcomes. [28] reported that all three domains of perfectionism predicted poorer treatment outcomes in a sample of outpatients receiving 10 weeks of cognitive behavioural group therapy for depression. This effect was mediated by a perceived lack of quality friendships. The role of perfectionism in the development and persistence of depression signals a need to better understand the factors that influence this relationship.

1.3. Coping

Coping strategies are an individual’s cognitive, emotional, and behavioural efforts to manage internal and external demands [29]. Task-oriented coping involves soliciting advice or direct help with problems in order to remove, avoid or minimize their impact [30], and has been associated with positive well-being [31]. Emotion-oriented coping encompasses a number of strategies used to manage negative feelings associated with a situation, ranging from acceptance and positive reframing to self-blame, denial, and rumination [32], [33], [34]. Although some studies have found this coping style to be effective for depressed patients, particularly against suicidal thoughts and behaviour [35], others have noted a positive correlation between depression and emotion-oriented coping [36]. Avoidant coping typically involves behaviourally or mentally disengaging from the problem by ignoring it and not attempting to find a solution or engaging in other activities to distract oneself from the problem [32]. Individuals who engage in avoidant coping are shown to have a greater risk for depression and post-traumatic symptoms along with an increased likelihood for substance dependence following a stressful life event [37], [38]. Thus, it is evident that the way in which one manages stress has a significant impact on mental health outcomes.

Several studies have determined that coping styles mediate the relationship between perfectionism and depression. [39] found that depressed patients with high perfectionism had a stronger tendency to use avoidant coping strategies when faced with stressors; this tendency was present even after 6 months of cognitive behavioural therapy [40]. In addition, depression was associated with a loss of task-oriented coping strategies in highly perfectionistic individuals [39]. Emotion-oriented coping, such as rumination, also affects the relationship between perfectionism and depression as well as IU and depression [16], [33]. Research has identified interactions between coping and perfectionism as well as coping and IU, but no study has examined the effect of all three constructs together in predicting depression.

1.4. Present study

Using a cross-sectional survey-based design, the present study aims to understand the role played by IU, perfectionism, and coping strategies within a clinical sample with depression. Specifically, we hypothesized that IU, perfectionism, and type of coping style will contribute to predicting the presence of MDD and its severity. Understanding how these constructs collectively predict depression diagnosis and severity may inform treatment plans, along with preventative measures, to better address the high rates of non-remission in clinical settings.

2. Methods

2.1. Procedure

This study included 549 outpatients (269 female, 280 male) with a mean age of 35.49 years (SD = 12.60) who were referred to a tertiary mood and anxiety disorder clinic in Toronto, Canada between 2011 and 2014. Out of the 549 participants, 144 were diagnosed with MDD.

Upon arrival at the clinic, enrolled patients completed informed consent forms, which included consent for the use of their data in current and archival studies, as approved by the Optimum Ethics Review Board. Patients were evaluated by a two-step procedure, which included administration of the MINI International Neuropsychiatric Interview Plus 5.0.0 (MINI Plus; [41], followed by a semi-structured psychiatric assessment, conducted by a board-certified psychiatrist to confirm diagnoses. Patients were subsequently distributed a series of self-report questionnaires as part of their initial intake assessment, which included the Intolerance of Uncertainty Scale (IUS; [42], Hewitt Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale (MPS; [43], Coping Inventory for Stressful Situations Scale (CISS; [44], and Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II; [45]).

2.2. Materials

2.2.1. Mini international neuropsychiatric interview plus 5.0.0 (MINI)

The MINI [41], validated in both North America and Europe [46], is a highly sensitive diagnostic interview used in clinical and research settings to screen for the most prevalent mental disorders. The MINI 5.0.0. has been shown to be compatible with the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) and the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders Fourth Edition (DSM-IV).

2.2.2. Intolerance of uncertainty scale (IUS)

The IUS [42] is a 27-item self-report measure, assessing the extent to which a person is able to tolerate uncertain or negative events. Items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all characteristic of me) to 5 (entirely characteristic of me). Higher scores indicate greater IU. The IUS-12 two-factor solution, consisting of Inhibitory IU and Prospective IU, was used in the current analyses due to support from various studies using clinical samples [47], [48], [49]. The IUS-12 contains 12 of the 27 items from the original IUS, including items such as “Unforeseen events upset me greatly” and “It frustrates me not having all the information I need.” The measure demonstrates good internal consistency (α = .85) [50] and good test-retest reliability and validity [51].

2.2.3. Hewitt multidimensional perfectionism scale (MPS)

The MPS [52] is a 45-item self-report questionnaire with three subscales measuring self-oriented perfectionism (e.g., “One of my goals is to be perfect in everything I do”), other-oriented perfectionism (e.g., “Everything that others do must be of top-notch quality”), and socially prescribed perfectionism (e.g., “I find it difficult to meet others’ expectations of me”). Items are rated on a 7-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Higher scores reflect greater levels of perfectionism. The construct has good internal consistency (α = .88 for self-oriented, α = .74 for other-oriented, and α = .81 for socially prescribed) [26] and reliability on repeat testing [43].

2.2.4. Coping inventory for stressful situations (CISS)

The CISS [44] is a 48-item self-report scale assessing three types of coping strategies, including task-oriented (e.g., “Focus on a problem and see how I can solve it”), emotion-oriented (e.g., “Blame myself for having gotten into this situation”), and avoidance-oriented (e.g., “Take some time off and get away from the situation”) coping. Participants rate how often they engage in each of these coping strategies when faced with difficult or stressful situations on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much). Higher scores on a certain subscale indicate greater use of that coping strategy. The CISS demonstrates good test-retest reliability, validity, and internal consistency (α = .78–.87 for task-oriented, α = .78–.87 for emotion-oriented, and α = .70–.80 for avoidance-oriented) [34], [44], [53].

2.2.5. Beck depression inventory-II (BDI-II)

The BDI-II [45] is a 21-item self-report measure assessing the severity of depressive symptoms (e.g., “I can't get any pleasure from the things I used to enjoy”). Participants rate each item on a 4-point Likert scale from 0 to 3 with higher scores reflecting greater symptom severity. A total score of 0–13 indicates minimal depression, 14–19 mild depression, 20–28 moderate depression, and 29–63 severe depression. The measure has high internal consistency (α = .90) [54] and reliability [45], [55].

2.3. Statistical analysis

The data was analysed using SPSS. A MANOVA was performed to assess differences in IU and perfectionism between the MDD and non-MDD groups. Since the CISS subscales exhibited small correlations with each other and with the MPS and IUS total scores, the requirement that the dependent variables must be conceptually related (or correlated) was not met. Therefore, a series of independent t-tests were conducted to assess differences in coping between the two groups.

In order to determine whether the three constructs are able to predict a depression diagnosis, a logistic regression was conducted, where the predictor variables were the IUS-12 total score, MPS total score, and CISS subscale scores while the dependent variable was the presence or absence of an MDD diagnosis (yes/no). Logistic regression models are frequently used in medical and health science research specifically epidemiology studies and evaluate the effects of predictor variables on binary outcomes [56], [57]. We chose to undertake this analysis due to previous reports and discussions surrounding statistical methods that indicate logistic regression models optimally assess the relationship between predictor variables and binary outcomes in the form of yes/no, agree/disagree, and present/absent, for instance the presence or absence of a disease [57], [58].

Previous studies indicate that when there is an imbalance in sample size between two groups, a logistic regression may be useful; however, unequal sample sizes may impact the accuracy of results obtained [59], [60]. For instance, a study investigating the impact of imbalanced data using a binary logistic regression found that as sample size increases, the effect of the imbalanced data on estimates decreases. Additionally, it was found that with a sample size of 100, a mild imbalance ratio where the proportion of the minority group was below 30% resulted in biased estimates [61]. The imbalanced ratio for our sample is 144/405 = 0.3555 = 35.56%. Since the minority group is over 30% of the majority group, our sample size should not lead to biased parameter estimates using the logistic regression [61].

Finally, a multiple linear regression was used to determine how well the three constructs are able to predict depression severity. The predictor variables were the IUS-12 total, MPS total, and CISS subscale scores, while the dependent variable was BDI-II total scores.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive and correlational analyses

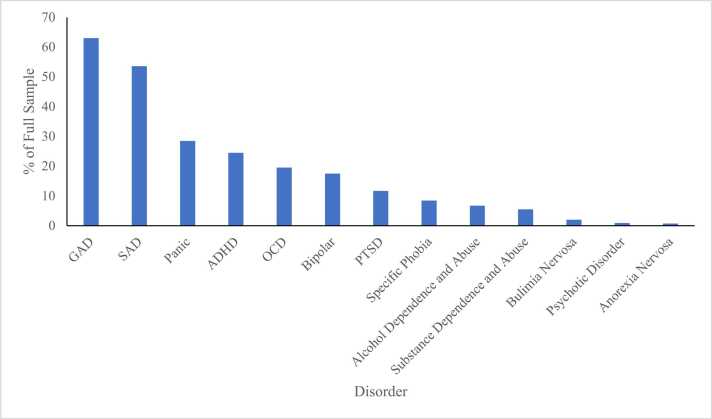

Table 1 shows the means, standard deviations, and Pearson correlations among variables. Both the MDD (n = 144) and non-MDD (n = 405) groups had many comorbidities (Fig. 1). The distribution of psychiatric diagnoses across the full sample was as follows: 62.96% generalized anxiety disorder (n = 345), 53.55% social anxiety disorder (n = 294), 28.42% panic disorder (n = 156), 24.45% attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (n = 134), 19.53% obsessive-compulsive disorder (n = 107), 17.49% bipolar disorder (n = 96), 11.68% post-traumatic stress disorder (n = 64), 8.39% specific phobia (n = 46), 6.7% alcohol dependence and abuse (n = 37), 5.46% substance dependence and abuse (n = 30), 2.01% bulimia nervosa (n = 11), 0.9% psychotic disorder (n = 5), and 0.73% anorexia nervosa (n = 4).

Table 1.

Means, Standard Deviations, and Pearson Correlations.

| Variable | M | SD | BDI-II total | CISS-Task | CISS-Emotion | CISS-Avoidant | MPS total | IUS-12 total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BDI-II total | 19.78 | 11.85 | — | |||||

| CISS-Task | 48.22 | 11.68 | -.371 | — | ||||

| CISS-Emotion | 50.26 | 11.75 | .531 | -.158 | — | |||

| CISS-Avoidant | 41.42 | 10.12 | -.028 | .171 | .250 | — | ||

| MPS total | 184.72 | 36.26 | .243 | .058 | .308 | .060 | — | |

| IUS-12 total | 35.77 | 10.21 | .409 | -.242 | .540 | .035 | .340 | — |

Note. Significant correlations (p < .05) are highlighted in bold.

Fig. 1.

Comorbidities in the Full Sample (n = 549) Fig. 1. The distribution of comorbid psychiatric diagnoses as percentages across the entire sample. Populations of individuals with MDD and without MDD both had many comorbidities. Abbreviations: GAD = generalized anxiety disorder, SAD = social anxiety disorder. ADHD = attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, OCD = obsessive-compulsive disorder, and PTSD = post-traumatic stress disorder.

Participants with depression did not differ from those without depression with respect to age, sex, social anxiety disorder, bipolar disorder, alcohol dependence or abuse, substance dependence or abuse, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, anorexia nervosa, and psychotic disorder, all ps > .103. Participants with depression were more likely to present with panic disorder, X2 (1, N = 549) = 9.92, p = .002, agoraphobia, X2 (1, N = 549) = 9.22, p = .002, obsessive-compulsive disorder, X2 (1, N = 549) = 5.64, p = .018, post-traumatic stress disorder, X2 (1, N = 548) = 6.97, p = .008, specific phobia, X2 (1, N = 548) = 5.95, p = .015, and were significantly less likely to have generalized anxiety disorder, X2 (1, N = 548) = 9.48, p = .002, and bulimia nervosa, X2 (1, N = 547) = 14.47, p < .001.

3.2. Differences in coping, perfectionism, and intolerance of uncertainty

A MANOVA was conducted to determine if IUS and MPS total scores differed based on whether or not a participant has depression (Table 2). The multivariate result was non-significant, Wilks’ Lambda (2, 530) = .989, p = .051, ηp2 = .011. The degree of intolerance of uncertainty significantly differed based on depression diagnosis, F(1, 531) = 5.511, p = .019, ηp2 = .010 (Table 3). Specifically, individuals with depression reported higher overall intolerance of uncertainty. MPS total scores did not significantly differ based on depression diagnosis, F(1, 531) = .031, p = .860, ηp2 < .001.

Table 2.

Multivariate Analysis of IUS and MPS Total Scores Between MDD and Non-MDD Groups.

| Effect | Value | F | Hypothesis df | Error df | p | ηp2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression | Pillai’s Trace | .011 | 2.984 | 2.000 | 530.000 | .051 | .011 |

| Wilks’ Lambda | .989 | 2.984 | 2.000 | 530.000 | .051 | .011 | |

| Hotelling’s Trace | .011 | 2.984 | 2.000 | 530.000 | .051 | .011 | |

| Roy’s Largest Root | .011 | 2.984 | 2.000 | 530.000 | .051 | .011 | |

Note. Results reported in the text are highlighted in bold.

Table 3.

Between-Subjects Effects for IUS and MPS Total Scores.

| Source | Dependent Variable | Type III Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | p | ηp2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression | IUS-12 total | 563.495 | 1 | 563.495 | 5.511 | .019 | .010 |

| MPS total | 39.932 | 1 | 39.932 | .031 | .860 | .000 |

Note. Significant effects (p < .05) are highlighted in bold.

A series of independent t-tests were conducted, with Bonferroni corrections, to assess differences between the depressed and non-depressed groups on the CISS subscales. Task-oriented coping scores of non-depressed individuals (M = 49.363, SD = 11.726) were significantly higher than those of depressed individuals (M = 46.386, SD = 11.474), t(541) = 2.961, p = .003. Emotion-oriented coping scores of depressed individuals (M = 52.396, SD = 11.584) were significantly higher than those of non-depressed individuals (M = 48.668, SD = 11.654), t(541) = −3.706, p < .001. A significant difference was not observed for the avoidant coping scores.

3.3. Prediction of depression diagnosis

A logistic regression was conducted to examine whether IUS total scores, MPS total scores, and CISS subscale scores could predict the presence or absence of MDD, as assessed by the MINI (Table 4). The logistic regression model was statistically significant, X2 (5) = 19.664, p = .001. The model explained 4.9% (Nagelkerke R2) of the variance in depression and correctly identified 59.1% of cases. Task-oriented coping (p = 0.035) and emotion-oriented coping (p = .009) contributed significantly to the model. Specifically, emotion-oriented coping was associated with an increased likelihood of depression, while task-oriented coping was associated with a decreased likelihood of depression. Intolerance of uncertainty, perfectionism, and avoidant coping were not significantly associated with depression diagnosis.

Table 4.

Logistic Regression Predicting Depression Diagnosis (MINI).

| Variable | B | SE | p | OR | 95% CI OR |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||||

| CISS-Task | -.017 | .008 | .035 | .983 | .967 | .999 |

| CISS-Emotion | .025 | .010 | .009 | 1.026 | 1.006 | 1.045 |

| CISS-Avoidant | -.002 | .009 | .871 | .998 | .980 | 1.017 |

| MPS total | -.002 | .003 | .376 | .998 | .992 | 1.003 |

| IUS-12 total | .005 | .011 | .659 | 1.005 | .984 | 1.027 |

| Constant | -.360 | .711 | .613 | .698 | ||

Note. Significant predictors (p < .05) are highlighted in bold. OR = odds ratio. CI = confidence interval.

3.4. Prediction of depression severity

Multiple linear regression was used to determine whether IUS total scores, MPS total scores, and CISS subscale scores could predict depression severity, as measured by the BDI-II, in the entire sample (Table 5). The model explained 39.4% of the variance and was a significant predictor of depression scores, R2 = .394, F(5, 521) = 67.61, p < .001. The variables that contributed significantly to the model include perfectionism (β = .105, p = .005), task-oriented coping (β = −.273, p < .001), emotion-oriented coping (β = .441, p < .001), and avoidant coping (β = −.100, p = .006). Intolerance of uncertainty was not a significant predictor of depression severity in this model (β = .073, p = .087).

Table 5.

Linear Regression Predicting Depression Severity (BDI-II).

| Variable | B | SE B | β | t | p | 95% CI |

VIF | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||||||

| CISS-Task | -.277 | .037 | -.273 | -7.490 | < .001 | -.349 | -.204 | 1.139 | |

| CISS-Emotion | .445 | .043 | .441 | 10.280 | < .001 | .360 | .530 | 1.581 | |

| CISS-Avoidant | -.117 | .042 | -.100 | -2.765 | .006 | -.201 | -.034 | 1.130 | |

| MPS total | .034 | .012 | .105 | 2.809 | .005 | .010 | .058 | 1.191 | |

| IUS-12 total | .085 | .050 | .073 | 1.713 | .087 | -.012 | .182 | 1.565 | |

| Constant | 6.289 | 3.208 | 1.960 | .050 | -.013 | 12.591 | |||

Note. Significant predictors (p < .05) are highlighted in bold. CI = confidence interval.

4. Discussion

Our previous study investigated the impact of intolerance of uncertainty, perfectionism, and coping on OCD. The current study aimed to explore how these same constructs, together, predict the presence and severity of depression. Previous studies have elucidated the relationship between depression and each of the three constructs individually, but this study provides the first evidence that they are collectively able to predict depression to a high degree.

In line with previous research, individuals with an MDD diagnosis were more intolerant of uncertainty than those without MDD, and a positive correlation was observed between IU and depression severity. Contrary to our hypothesis, perfectionism scores did not differ between the MDD and non-MDD groups. Although our findings approach significance, the presence of comorbidities may in part explain the insignificant findings. In particular, the most common diagnoses in our sample were generalized anxiety disorder, social anxiety disorder, and panic disorder. Research on perfectionism and anxiety suggests that the two are strongly correlated [26], [62]. Therefore, having a large number of participants with anxiety disorders in our overall sample may have resulted in similar perfectionism scores between the MDD and non-MDD groups. Furthermore, although perfectionism was not associated with a depression diagnosis, it was positively associated with depression severity. In addition, individuals with MDD were more likely to use emotion-oriented coping, which was associated with greater depression severity compared to task-oriented coping. The MDD and non-MDD groups did not differ in avoidant coping, which was also unrelated to the severity of the disorder. The regression model revealed that individuals with high perfectionism who were more likely to engage in emotion-oriented coping and less likely to engage in task-oriented and avoidant coping experienced more severe MDD symptoms than others.

Our findings support research showing that perfectionism exacerbates depressive symptoms [26] and that coping may play a role in this relationship [33], [39]. Indeed, research has determined that the relationship between depression and certain domains of perfectionism—socially prescribed and, to some degree, self-oriented perfectionism—is mediated by emotion-oriented coping strategies [33]. Interestingly, avoidant coping on its own was uncorrelated with depression scores but predicted lower depression severity in the regression model. This contradicts research showing that depressive symptoms are worsened by avoidant coping. A possible explanation for this finding may be that avoidant coping provides temporary relief from symptoms of depression but increases the severity of the disorder in the long run. It may also be that overall depression scores in our sample were in the mild to moderate range and avoidant coping is particularly harmful in cases of severe depression.

Conversely, IU was correlated with depression scores but was an insignificant predictor of depression severity. While previous research demonstrates a strong association between IU and MDD [9], [47], our findings suggest that this association may be present largely due to perfectionism and coping styles. In our study, IU was positively correlated with emotion-oriented coping; previous studies have identified rumination—a form of emotion-oriented coping—to be a complete mediator in the IU-depression link [16], [17], [18]. Additionally, a positive correlation was observed between IU and perfectionism, indicating that perfectionism may also be a mediator in the IU-depression relationship. It is possible that those with high IU who are also highly perfectionistic are more prone to depression than those with high IU and low perfectionism.

5. Limitations and future directions

The present study has several limitations that should be noted. First, due to its cross-sectional nature, no causal conclusions can be made. Future research should utilize a longitudinal design to examine the relationships between depression and the three constructs across various timepoints. For instance, while perfectionism and emotion-oriented coping may worsen depression symptoms, it is also worth considering that depression may worsen existing perfectionistic tendencies and reinforce the use of emotion-oriented coping over task-oriented coping. Second, aside from depression diagnosis, all other variables in this study were assessed via self-report measures, which may not provide the most accurate representation of participants’ actual experiences. Future studies should employ alternative research methods, such as informant ratings or behavioural measures, to objectively assess IU, perfectionism, and coping. Third, group differences in comorbidity may have affected the results since certain disorders were more prevalent in one group than the other (e.g., the MDD group was more likely to have panic disorder than the non-MDD group). Fourth, within-group differences in the MDD group used in this investigation comprised subjects undergoing both current and/or past episodes of depression. Future studies should expand on the analyses by separating current versus past episodes of depression in order to assess the efficacy of IU, MPS, and CISS in predicting depression severity.

For this study, we chose to focus on whether overall scores on the IUS and MPS along with subscale scores on the CISS could accurately predict depression. It was decided that if the overall model was significant, we may analyse interactions between the subscales of all three constructs in subsequent studies. This presents another avenue for future research, which is to explore how different aspects of IU, perfectionism, and coping interact to predict depression. For example, emotion-oriented coping may be more strongly associated with depression in individuals who are higher on socially prescribed perfectionism than self-oriented perfectionism. Moreover, as previously mentioned, IU may be correlated with depression at high levels of perfectionism but not at low levels of perfectionism. Furthermore, the interaction of IU within the analyses can be separated into its two respective subscales of inhibitory and prospective IU to evaluate differences in the accuracy of predicting depression outcomes. Therefore, an in-depth investigation of the interactions between these factors may provide deeper insights into how they work in tandem to influence MDD.

Although the predictive accuracy of our logistic regression model was relatively low, it suggests the possibility that coping styles may exert some influence on the presence and perhaps the development of MDD. Examining factors that contribute to the developmental pathway of this disorder may inform treatment plans moving forward. Thus, future studies may use our findings to investigate a targeted approach to treating depression. For instance, individuals with MDD may benefit from interventions that are personalized to their levels of IU, perfectionism, and coping. Given that depression scores in our sample were mostly impacted by perfectionism and coping, interventions should aim to reduce perfectionistic tendencies and foster the use of task-oriented over emotion-oriented coping strategies. Recent research showing that perfectionism and coping hinder treatment outcomes in those with depression further underlines the importance of designing treatments that directly target these factors [28], [40].

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests: Martin Katzman reports a relationship with S.T.A.R.T Clinic for Mood and Anxiety Disorders that includes: employment and non-financial support. Martin Katzman reports a relationship with Adler Graduate Professional School that includes: employment. Martin Katzman reports a relationship with NOSM University that includes: employment. Martin Katzman reports a relationship with Lakehead University that includes: employment. Martin Katzman reports a relationship with AbbVie Inc that includes: consulting or advisory and funding grants. Martin Katzman reports a relationship with Eisai Co Ltd that includes: consulting or advisory and funding grants. Martin Katzman reports a relationship with Empower Pharmacy that includes: consulting or advisory. Martin Katzman reports a relationship with Janssen Pharmaceuticals Inc that includes: consulting or advisory and travel reimbursement. Martin Katzman reports a relationship with Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co Ltd that includes: consulting or advisory and travel reimbursement. Martin Katzman reports a relationship with Pfizer Inc that includes: consulting or advisory, funding grants, and travel reimbursement. Martin Katzman reports a relationship with Purdue Pharma LP that includes: consulting or advisory and travel reimbursement. Martin Katzman reports a relationship with Santé Cannabis that includes: consulting or advisory. Martin Katzman reports a relationship with Shire that includes: consulting or advisory and travel reimbursement. Martin Katzman reports a relationship with Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited that includes: consulting or advisory and travel reimbursement. Martin Katzman reports a relationship with Tilray Inc that includes: consulting or advisory and travel reimbursement. Martin Katzman reports a relationship with Lundbeck that includes: consulting or advisory, funding grants, and travel reimbursement. Martin Katzman reports a relationship with Allergan Canada that includes: consulting or advisory and travel reimbursement. Martin Katzman reports a relationship with Sunovion Pharmaceuticals Inc that includes: consulting or advisory and travel reimbursement. Martin Katzman reports a relationship with Biohaven Ltd that includes: funding grants. Irvin Epstein reports a relationship with Pfizer Inc that includes: funding grants and speaking and lecture fees. Irvin Epstein reports a relationship with Janssen Pharmaceuticals Inc that includes: funding grants and speaking and lecture fees. Irvin Epstein reports a relationship with Alkermes Plc that includes: equity or stocks. Alethea Correa reports a relationship with Pfizer Inc that includes: consulting or advisory and speaking and lecture fees. Alethea Correa reports a relationship with Bayer Corporation that includes: consulting or advisory and speaking and lecture fees. Alethea Correa reports a relationship with Novo Nordisk Inc that includes: consulting or advisory and speaking and lecture fees. Alethea Correa reports a relationship with Medexus Pharmaceuticals Inc that includes: consulting or advisory and speaking and lecture fees. Alethea Correa reports a relationship with University of Toronto Department of Family & Community Medicine that includes: employment.

Appendix

Table 6.

Means and Standard Deviations Within MDD and Non-MDD Groups.

| Variable | Depression |

No Depression |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | ||

| CISS-Task | 46.386 | 11.474 | 49.363 | 11.726 | |

| CISS-Emotion | 52.396 | 11.584 | 48.668 | 11.654 | |

| CISS-Avoidant | 41.545 | 10.290 | 41.235 | 9.965 | |

| MPS total | 184.944 | 36.061 | 184.253 | 35.632 | |

| IUS-12 total | 37.003 | 10.036 | 34.921 | 10.125 | |

References

- 1.World Health Organization. (2017). Depression and other common mental disorders: Global health estimates. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/254610 (accessed 18 September 2022).

- 2.González H.M., Vega W.A., Williams D.R., Tarraf W., West B.T., Neighbors H.W. Depression care in the United States: too little for too few. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(1):37–46. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sternat T., Fotinos K., Fine A., Epstein I., Katzman M.A. Low hedonic tone and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: risk factors for treatment resistance in depressed adults. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2018;14:2379–2387. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S170645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fotinos K., Fine A., Nasiri K., Youmer N., Sternat T., Cook S., Epstein I., Katzman M.A. Predicting OCD: an analysis of the conceptually related measures of intolerance of uncertainty, perfectionism, and coping. EC Psychol Psychiatry. 2018;7:270–280. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buhr K., Dugas M.J. The role of fear of anxiety and intolerance of uncertainty in worry: an experimental manipulation. Behav Res Ther. 2009;47(3):215–223. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2008.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Counsell A., Furtado M., Iorio C., Anand L., Canzonieri A., Fine A., Fotinos K., Epstein I., Katzman M.A. Intolerance of uncertainty, social anxiety, and generalized anxiety: differences by diagnosis and symptoms. Psychiatry Res. 2017;252:63–69. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.02.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Whiting S.E., Jenkins W.S., May A.C., Rudy B.M., Davis T.E., 3rd, Reuther E.T. The role of intolerance of uncertainty in social anxiety subtypes. J Clin Psychol. 2014;70(3):260–272. doi: 10.1002/jclp.22024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gillett C.B., Bilek E.L., Hanna G.L., Fitzgerald K.D. Intolerance of uncertainty in youth with obsessive-compulsive disorder and generalized anxiety disorder: A transdiagnostic construct with implications for phenomenology and treatment. Clin Psychol Rev. 2018;60:100–108. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2018.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gentes E.L., Ruscio A.M. A meta-analysis of the relation of intolerance of uncertainty to symptoms of generalized anxiety disorder, major depressive disorder, and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Clin Psychol Rev. 2011;31(6):923–933. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2011.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hong R.Y., Lee S.S. Further clarifying prospective and inhibitory intolerance of uncertainty: factorial and construct validity of test scores from the Intolerance of Uncertainty Scale. Psychol Assess. 2015;27(2):605–620. doi: 10.1037/pas0000074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Andersen S.M. The inevitability of future suffering: the role of depressive predictive certainty in depression. Soc Cogn. 1990;8(2):203–228. doi: 10.1521/soco.1990.8.2.203. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jensen D., Cohen J.N., Mennin D.S., Fresco D.M., Heimberg R.G. Clarifying the unique associations among intolerance of uncertainty, anxiety, and depression. Cogn Behav Ther. 2016;45(6):431–444. doi: 10.1080/16506073.2016.1197308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dupuy J.B., Ladouceur R. Cognitive processes of generalized anxiety disorder in comorbid generalized anxiety disorder and major depressive disorder. J Anxiety Disord. 2008;22(3):505–514. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2007.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saulnier K.G., Allan N.P., Raines A.M., Schmidt N.B. Depression and intolerance of uncertainty: relations between uncertainty subfactors and depression dimensions. Psychiatry. 2019;82(1):72–79. doi: 10.1080/00332747.2018.1560583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nelson B.D., Shankman S.A., Proudfit G.H. Intolerance of uncertainty mediates reduced reward anticipation in major depressive disorder. J Affect Disord. 2014;158:108–113. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang V., Yu M., Carleton R.N., Beshai S. Intolerance of uncertainty fuels depressive symptoms through rumination: cross-sectional and longitudinal studies. PloS One. 2019;14(11) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0224865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liao K.Y., Wei M. Intolerance of uncertainty, depression, and anxiety: the moderating and mediating roles of rumination. J Clin Psychol. 2011;67(12):1220–1239. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yook K., Kim K.H., Suh S.Y., Lee K.S. Intolerance of uncertainty, worry, and rumination in major depressive disorder and generalized anxiety disorder. J Anxiety Disord. 2010;24(6):623–628. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2010.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boswell J.F., Thompson-Hollands J., Farchione T.J., Barlow D.H. Intolerance of uncertainty: a common factor in the treatment of emotional disorders. J Clin Psychol. 2013;69(6):630–645. doi: 10.1002/jclp.21965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shafran R., Cooper Z., Fairburn C.G. Clinical perfectionism: a cognitive-behavioural analysis. Behav Res Ther. 2002;40(7):773–791. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(01)00059-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Flett G.L., Hewitt P.L., Blankstein K.R., Mosher S.W. Perfectionism and self-actualization, and personal adjustment. J Soc Behav Personal. 1991;6(5):147–160. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hewitt P.L., Flett G.L. Perfectionism and depression: a multidimensional analysis. J Soc Behav Personal. 1990;5(5):423. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Klibert J.J., Langhinrichsen-Rohling J., Saito M. Adaptive and maladaptive aspects of self-oriented versus socially prescribed perfectionism. J Coll Stud Dev. 2005;46(2):141–156. doi: 10.1353/csd.2005.0017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rice K.G., Dellwo J.P. Within-semester stability and adjustment correlates of the Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale. Meas Eval Couns Dev. 2001;34(3):146–156. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith M.M., Sherry S.B., Rnic K., Saklofske D.H., Enns M., Gralnick T. Are perfectionism dimensions vulnerability factors for depressive symptoms after controlling for neuroticism? A meta–analysis of 10 longitudinal studies. Eur J Personal. 2016;30(2):201–212. doi: 10.1002/per.2053. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hewitt P.L., Flett G.L. Perfectionism in the self and social contexts: conceptualization, assessment, and association with psychopathology. J Personal Soc Psychol. 1991;60(3):456–470. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.60.3.456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smith M.M., Sherry S.B., McLarnon M.E., Flett G.L., Hewitt P.L., Saklofske D.H., Etherson M.E. Why does socially prescribed perfectionism place people at risk for depression? A five-month, two-wave longitudinal study of the Perfectionism Social Disconnection Model. Personal Individ Differ. 2018;134:49–54. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2018.05.040. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hewitt P.L., Smith M.M., Deng X., Chen C., Ko A., Flett G.L., Paterson R.J. The perniciousness of perfectionism in group therapy for depression: a test of the perfectionism social disconnection model. Psychother (Chic, Ill ) 2020;57(2):206–218. doi: 10.1037/pst0000281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lazarus R.S., Folkman S. Coping and adaptation. Handb Behav Med. 1984;282325:282–325. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lazarus R.S. Emotions and interpersonal relationships: toward a person-centered conceptualization of emotions and coping. J Personal. 2006;74(1):9–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2005.00368.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Williams K., McGillicuddy-De Lisi A. Coping strategies in adolescents. J Appl Dev Psychol. 1999;20(4):537–549. doi: 10.1016/S0193-3973(99)00025-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carver C.S., Scheier M.F., Weintraub J.K. Assessing coping strategies: a theoretically based approach. J Personal Soc Psychol. 1989;56(2):267–283. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.56.2.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Senra C., Merino H., Ferreiro F. Exploring the link between perfectionism and depressive symptoms: contribution of rumination and defense styles. J Clin Psychol. 2018;74(6):1053–1066. doi: 10.1002/jclp.22571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Endler N.S., Parker J.D. Assessment of multidimensional coping: task, emotion, and avoidance strategies. Psychol Assess. 1994;6(1):50. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.6.1.50. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Horwitz A.G., Czyz E.K., Berona J., King C.A. Prospective associations of coping styles with depression and suicide risk among psychiatric emergency patients. Behav Ther. 2018;49(2):225–236. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2017.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cohan S.L., Jang K.L., Stein M.B. Confirmatory factor analysis of a short form of the Coping Inventory for Stressful Situations. J Clin Psychol. 2006;62(3):273–283. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ouimette P.C., Finney J.W., Moos R.H. Two-year posttreatment functioning and coping of substance abuse patients with posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychol Addict Behav. 1999;13(2):105. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.13.2.105. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pineles S.L., Mostoufi S.M., Ready C.B., Street A.E., Griffin M.G., Resick P.A. Trauma reactivity, avoidant coping, and PTSD symptoms: a moderating relationship? J Abnorm Psychol. 2011;120(1):240–246. doi: 10.1037/a0022123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dunkley D.M., Lewkowski M., Lee I.A., Preacher K.J., Zuroff D.C., Berg J.L., Foley J.E., Myhr G., Westreich R. Daily stress, coping, and negative and positive affect in depression: complex trigger and maintenance patterns. Behav Ther. 2017;48(3):349–365. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2016.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Richard A., Dunkley D.M., Zuroff D.C., Moroz M., Elizabeth Foley J., Lewkowski M., Myhr G., Westreich R. Perfectionism, efficacy, and daily coping and affect in depression over 6 months. J Clin Psychol. 2021;77(6):1453–1471. doi: 10.1002/jclp.23079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sheehan D.V., Janavs J., Baker R., Harnett-Sheehan K., Knapp E., Sheehan M.F., Dunbar G.C. M.I.N.I. – Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview – English version 5.0.0 – DSM-IV. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59:34–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Freeston M.H., Rhéaume J., Letarte H., Dugas M.J., Ladouceur R. Why do people worry? Personal Individ Differ. 1994;17(6):791–802. doi: 10.1016/0191-8869(94)90048-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hewitt P.L., Flett G.L., Turnbull-Donovan W., Mikail S.F. The multidimensional perfectionism scale: reliability, validity, and psychometric properties in psychiatric samples. Psychol Assess: A J Consult Clin Psychol. 1991;3(3):464–468. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.3.3.464. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Endler N.S., Parker J.D. Assessment of multidimensional coping: task, emotion, and avoidance strategies. Psychol Assess. 1994;6(1):50. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Beck A.T., Steer R.A., Brown G.K. Psychological Corporation; 1996. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory-II. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lecrubier Y., Sheehan D.V., Weiller E., Amorim P., Bonora I., Sheehan K.H.…Dunbar G.C. The mini international neuropsychiatric interview (MINI). A short diagnostic structured interview: reliability and validity according to the CIDI. Eur Psychiatry. 1997;12(5):224–231. doi: 10.1016/S0924-9338(97)83296-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Carleton R.N., Mulvogue M.K., Thibodeau M.A., McCabe R.E., Antony M.M., Asmundson G.J. Increasingly certain about uncertainty: intolerance of uncertainty across anxiety and depression. J Anxiety Disord. 2012;26(3):468–479. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2012.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jacoby R.J., Fabricant L.E., Leonard R.C., Riemann B.C., Abramowitz J.S. Just to be certain: confirming the factor structure of the intolerance of uncertainty scale in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Anxiety Disord. 2013;27(5):535–542. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2013.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McEvoy P.M., Mahoney A.E. To be sure, to be sure: intolerance of uncertainty mediates symptoms of various anxiety disorders and depression. Behav Ther. 2012;43(3):533–545. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2011.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Carleton R.N., Norton M.P.J., Asmundson G.J. Fearing the unknown: a short version of the Intolerance of Uncertainty Scale. J Anxiety Disord. 2007;21(1):105–117. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2006.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Buhr K., Dugas M.J. The intolerance of uncertainty scale: psychometric properties of the English version. Behav Res Ther. 2002;40(8):931–945. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(01)00092-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hewitt P.L., Flett G.L. Multi-Health Systems; Toronto, Canada: 2004. Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale (MPS): Technical manual. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Takagishi Y., Sakata M., Kitamura T. Factor structure of the coping inventory for stressful situations (CISS) in Japanese workers. Psychology. 2014;5(14):1620. doi: 10.4236/psych.2014.514172. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang Y.P., Gorenstein C. Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory-II: a comprehensive review. Braz J Psychiatry. 2013;35:416–431. doi: 10.1590/1516-4446-2012-1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Beck A.T., Steer R.A., Ball R., Ranieri W. Comparison of Beck Depression Inventories -IA and -II in psychiatric outpatients. J Personal Assess. 1996;67(3):588–597. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6703_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nick T.G., Campbell K.M. Logistic regression. Top Biostat. 2007:273–301. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-530-5_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hayes A.F. Routledge,; 2020. Statistical methods for communication science. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hellevik O. Linear versus logistic regression when the dependent variable is a dichotomy. Qual Quant. 2009;43:59–74. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Olvera Astivia O.L., Gadermann A., Guhn M. The relationship between statistical power and predictor distribution in multilevel logistic regression: a simulation-based approach. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2019;19(1) doi: 10.1186/s12874-019-0742-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Herrera A.N., Gómez J. Influence of equal or unequal comparison group sample sizes on the detection of differential item functioning using the Mantel–Haenszel and logistic regression techniques. Qual Quant. 2008;42:739–755. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rahman H.A.A., Wah Y.B., Huat O.S. Predictive performance of logistic regression for imbalanced data with categorical covariate. Pertanika J Sci Technol. 2021;29(1) [Google Scholar]

- 62.Egan S.J., Wade T.D., Fitzallen G., O'Brien A., Shafran R. A meta-synthesis of qualitative studies of the link between anxiety, depression and perfectionism: implications for treatment. Behav Cogn Psychother. 2022;50(1):89–105. doi: 10.1017/S1352465821000357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]