Abstract

Endoscopic treatment of duodenal papillary tumors is well described. This study aims to provide new evidence for the treatment of benign papillary tumors through comparisons between endoscopic snare papillectomy (ESP) and endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR).

Between May 2010 and December 2017, 72 patients were enrolled. Diagnosis and treatment procedures were ESP and EMR. Endoscopic follow-up evaluation was done periodically as a surveillance measurement for recurrence.

Seventy-two patients with ampullary tumors were enrolled, of which 66 had adenomas including 9 high-grade intraepithelial neoplasias and 2 carcinomas in adenoma. Complete resections with tumor-free lateral and basal margins were achieved in all patients. Postoperative complications were bleeding (9.5% in EMR vs 10% in ESP) and pancreatitis (2.4% in EMR and 3.3% in ESP), with no occurrence of perforation, cholangitis or papillary stenosis. Adenoma recurrence was found in 7 patients (14.3% in EMR vs 3.3% in ESP) at 1 year.

The ESP procedure is safe and effective for benign ampullary adenoma, high-grade intraepithelial neoplasias, and noninvasive cancer without intraductal tumor growth, which has a shorter procedural duration, as well as lower complication, recurrence rates and hospitalization costs.

Keywords: benign papillary tumors, endoscopic mucosal resection, endoscopic snare papillectomy

1. Introduction

Adenomas of the duodenal papilla, or ampullary adenomas, are premalignant lesions of ampullary carcinomas which should be resected when necessary.[1,2] Many researches have shown that endoscopic papillectomy is a feasible management for benign papillary tumors without components of invasive carcinoma.[3–5] Compared to surgery, endoscopic papillectomy may substantially lower the treatment cost and reduce morbidity and mortality.[6]

Current techniques for endoscopic resection of papillary tumors include cold snare polypectomy, endoscopic snare papillectomy (ESP) and endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR), and so on. ESP originally use an oval rigid diathermic loop, and the lesion is transected using electric currency. EMR was performed with saline mixture submucosal injection and snare resection. Provided with the controversial indications, advantages, and limitations of endoscopic papillectomy, clinical decisions are difficult to make. Currently, the decision of whether ESP or EMR should be performed is based mostly on physician's personal experience, with little evidence from direct comparison of ESP and EMR.[7–9] There, we hereby report a single-center experience of 72 patients who underwent endoscopic resections of the papilla and evaluate the safety and efficacy of ESP and EMR, thus to facilitate the decision-making of physicians on appropriate procedure for papillary tumors.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Patients

All patients who underwent an endoscopic resection of the major papilla at Changhai hospital between May 2010 and December 2017 were enrolled. All patients had tumors that were confined to the mucosa and no intraductal tumor growth was found by the endoscopic ultrasound or magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography before endoscopic resection. Exclusion of endoscopy contraindications, coagulation function and platelet abnormalities. All procedures were performed with the patient under sedation using diazepam and dolantin. This is a retrospective study and does not require Ethical approval. Written informed consent to participate was obtained from all patients included in the study.

2.2. Resection technique

All papillectomy procedures were performed by experienced pancreatobiliary endoscopists by using a therapeutic duodenoscope (Olympus TJF260; Olympus Optical, Tokyo, Japan). The procedures include endoscopic snare papillectomy (ESP) and EMR. EMR was performed with saline mixture submucosal injection and snare resection. The submucosal injection of saline was mixed with epinephrine (1:10,000) and indigo carmine. The resection was performed with an oval rigid diathermic loop (diameter of 2.5 × 5.5 cm, cook medical) and Elton injection needle. During the endoscopic procedure, endoscopic hemostasis (adrenaline injection, endoclips and plasma Argon coagulation) was performed, and pancreatic stents (short, 5F, single-pigtail, cook medical) was inserted after the resection of the papilla in order to prevent acute pancreatitis. The endotherapy were performed under sedationor anaesthesia, and the minimum experience of the endoscopists was 10 years.

3. Results

3.1. Preoperative assessment

Seventy-two patients underwent endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) (38/72, 52.8%) or magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) (34/72, 47.2%), EUS and MRCP (14/72, 17.4%) assessment before the endoscopic resection. EUS and MRCP showed a lesion limited to the mucosa without intraductal tumor growth.

3.2. Endoscopic resection

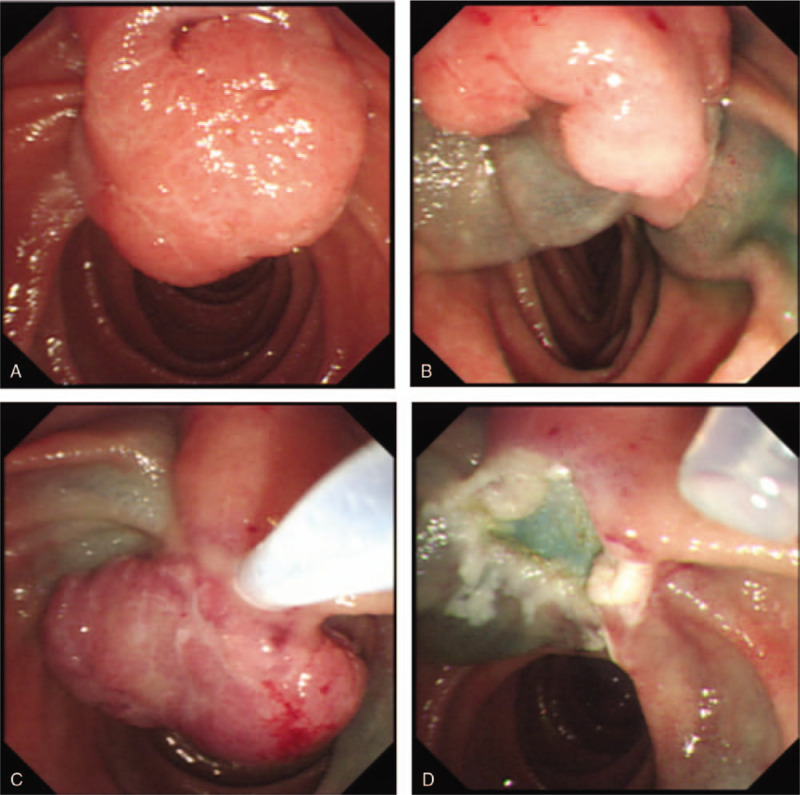

The procedures include ESP (N = 30) and EMR (N = 42) [Figures 1 and 2]. Four cases underwent piecemeal ampullectomy (ESP = 3, EMR = 1). A pancreatic stent was inserted in 14 patients undergoing ESP and 18 patients undergoing EMR. None biliary stenting was performed in any case.

Figure 1.

(A) Ampulloma before resection. (B) Tumor inserted in the snare. (C) Post endoscopic resection appearance.

Figure 2.

(A) Appearance of the ampulloma before resection. (B) Submucosal saline injection. (C)Tumor inserted in the snare. (D) Post endoscopic resection aspect. Complications.

No mortality occurred during the study period. Postoperative complications were mild acute pancreatitis in 2 patients (ESP = 1, EMR = 1) and gastrointestinal bleeding in 7 patients (ESP = 3, EMR = 4). No cases of perforation, cholangitis and papillary stenosis occurred during the study period. No significant difference was found between ESP and EMR resection groups in incidences of pancreatitis (3.3% vs 2.4%, P > .05) and bleeding (10% vs 9.5%, P > .05). All patients with complications were successfully treated medically. Thirty-two patients (ESP = 14, EMR = 18) had pancreatic stent placement, and 40 patients (ESP = 16, EMR = 24) did not. The two patients who suffered from acute pancreatitis did not have pancreatic stent placement. Seven patients had repeated endoscopy for hemostasis due to gastrointestinal bleeding after the procedure.

The mean procedure time of ESP was 84.2s, while that of EMR was 72.5s. And the median procedure time of ESP was 94s, while that of EMR was 67s. The procedure time has no statistical difference between ESP and EMR (P = .4818, P > .05). From the economic point of views, the total hospitalization costs of each patient was 18134.46 ± 8298.96 yuan by ESP and 22329.39 ± 8583.85 yuan by EMR (P = .0296, P < .05). Table 1.

Table 1.

The procedure time and the total hospitalization costs.

3.3. Histology

The histological results of all patients undergoing papillary tumor resection were: fibrosinginflammatory tissue in 6 (8.3%) patients, tubular adenoma in 15 (20.8%) patients, adenoma with low-grade intraepithelial neoplasia in 40 (55.6%) patients, adenoma with high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia in 9 (12.5%) patients, and adenocarcinoma in 2 (2.8%) patients. Complete resections with tumor-free lateral and basal margins were achieved.

3.4. Follow-up

The 72 patients with an endoscopic resection were followed up for 1 year. At 6-months follow-up, the adenomatous tissue had no change. At 1-year follow-up, histologically-confirmed recurrent adenomatous tissue at the resection site was detected in 7 out of 72 patients (EMR = 6, 14.3%; ESP = 1, 3.3%; P > .05). These 7 patients were treated with ESP or EMR after recurrence was detected.

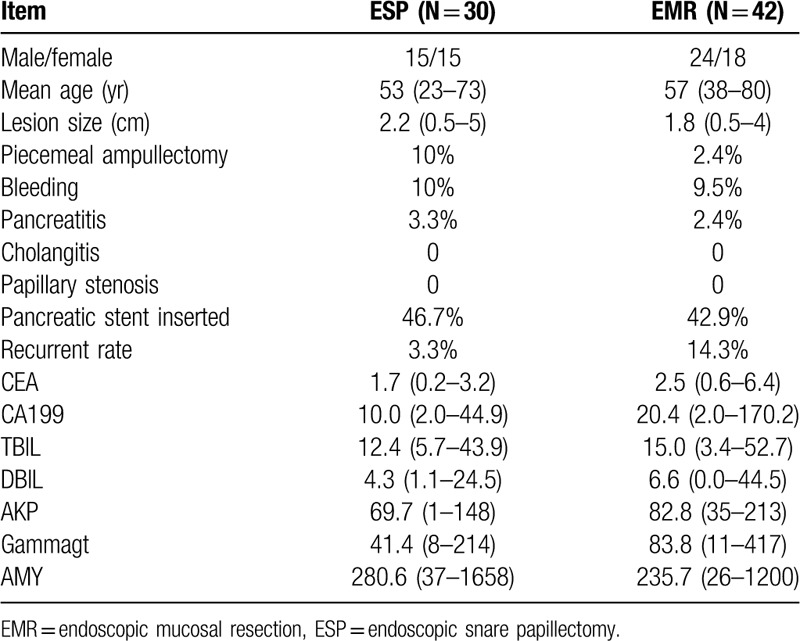

Patients’ clinical characteristics, lesion size, complications, and recurrence status were listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Patients’ clinical characteristics and treatment modalities of papillary tumors.

4. Discussion

Endoscopic papillectomy is an effective treatment for papillary tumors which should be considered in patients with smaller lesions (less than 3 cm in size) without carcinomatous components.[1,10–12] The present study showed that all benign papillary tumors of the enrolled patients were completely removed, with endoscopic en bloc resection achieved in 68 (94%) patients. The biggest lesion size was 5 cm. Preoperative EUS and MRCP done in our study were very helpful to assess the possibility of endoscopic resection for invasive carcinoma or evaluate the involvement of pancreatic and biliary ducts. With careful patient selection and preoperative tests, both ESP and EMR can be safe and effective therapeutic strategies.

By resecting the muscularis mucosae more thorough, the reported recurrence rate of EMR in Japanese patients is low (0%–8%; mean size, 9.4–10 mm). However, in the duodenum, submucosal vessels and Brunner's glands often make lift of the mucosa by submucosal injection difficult. Moreover, inadequate submucosal injection creates a large bleb with excessive mucosal tension and it can make snaring of superficial lesions difficult in some patients.[13] Whether submucosal injection with saline combined with epinephrine or methylene blue should be done before endoscopic resection is controversial.[3,14,15] Some case series have reported that the combination of epinephrine and methylene blue can contribute to minimize bleeding, getting a clearer version of the margins, and reducing complications.[16,17] The present study showed no significant statistical difference comparing the bleeding rates between ESP and EMR resection groups (10% vs 9.5%, P > .05), ie, EMR cannot reduce the risk of bleeding in comparison with ESP. Although there is no statistical difference between ESP and EMR (P = .4818, P > .05), the mean procedure time (EMR = 84.2 minutes, ESP = 72.5 min) and median procedure time (EMR = 94 minutes, ESP = 67 minutes) shows a trend that using a therapeutic duodenoscope and saline injection could increase operational difficulty.

The overall complication rate after endoscopic papillectomy is about 15%, including pancreatitis, bleeding, perforation, cholangitis, and papillary stenosis.[10,16,18–20] The most serious complications are perforation (0%-4%), pancreatitis (0%-25%) and delayed bleeding (0%-25%).[10,14,15,17,18,21–24] Procedure-related mortality is very low (0%-0.3%).[25] Previous published studies have demonstrated the necessity of a pancreatic stent placement, which could significantly decrease the risk of pancreatitis.[26] In our study, there were 2 cases of mild acute pancreatitis (ESP 3.3%, EMR 2.4%) and 7 gastrointestinal bleeding (ESP 10%, EMR 9.5%), with no occurrence of perforation, cholangitis and papillary stenosis. The 2 patients who encountered acute pancreatitis did not have pancreatic stent placement. Thus, the incidence of acute pancreatitis is 5% (2/40) in patients without stent placement versus 0% (0/32) in those with stent placement. Seven patients with gastrointestinal bleeding after the first procedure had repeated endoscopy for hemostasis. Meanwhile, there was no significant statistical difference in terms of incidences of pancreatitis (3.3% vs 2.4%, P > .05) and bleeding rates (10% vs 9.5%, P > .05) between ESP and EMR resection groups.

Previous studies have shown a high rate (0%-30%) of adenoma recurrence after endoscopic papillectomy despite a complete removal.[15,22,26] It has been postulated that an en bloc excision can reduce recurrence rates. However, an en bloc excision may not be technically feasible if the adenoma is of large size. In our study, endoscopic resection of benign papillary tumors was conducted in 68 (94%) patients, even for large tumors up to 5 cm in diameter. Postoperative histological results were: fibrosing inflammatory tissue (8.3%), tubular adenoma (20.8%), adenoma with low-grade intraepithelial neoplasia (55.6%), adenoma with high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia (12.5%), and adenocarcinoma (2.8%). Complete resections with tumor-free lateral and basal margins were achieved. Moreover, we found a 3.3% (ESP) vs 14.3% (EMR) risk of recurrence after a follow-up of 1 year. Thus, we speculate that ESP can reduce recurrence rate, as long as the resection is sufficient and complete with negative margins of resection. However, the conclusion of this study is limited by a relatively short follow-up period. Therefore, the results of our study need to be validated by data with long-term follow-up.

In conclusion, ESP is a safe and efficient treatment modality for benign lesions of the major papilla, which can reduce the procedural time and hospitalization cost with low complication and recurrence rates.

Author contributions

Data curation: Mengni Jiang, Hailing Tang, Yuan Yang, Wei Zhang

Formal analysis: Shunli Lü, Mengni Jiang

Methodology: Minmin Zhang, Zhendong Jin, Zhaoshen Li

Methodology: Minmin Zhang, Feng Liu

Writing – original draft: Shunli Lü

Footnotes

Abbreviations: EMR = endoscopic mucosal resection, ESP = endoscopic snare papillectomy, EUS = endoscopic ultrasonography, MRCP = magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography.

How to cite this article: Lü S, Jiang M, Liu F, Tang H, Yang Y, Zhang W, Zhang M, Jin Z, Li Z. Endoscopic papillectomy of benign papillary tumors: a single-center experience. Medicine. 2020;99:22(e20414).

SL and MJ authors contuibuted equally.

The authors have no funding and conflicts of interest to disclose.

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- [1].Hirota WK, Zuckerman MJ, Adler DG, et al. ASGE guideline: the role of endoscopy in the surveillance of premalignant conditions of the upper GI tract. Gastrointest Endosc 2006;63:570–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Moon JH, Choi HJ, Lee YN. Current status of endoscopic papillectomy for ampullary tumors. Gut Liver 2014;8:598–604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Adler DG, Qureshi W, Davila R, et al. The role of endoscopy in ampullary and duodenal adenomas. Gastrointest Endosc 2006;64:849–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Klein A, Tutticci N, Bourke MJ. Endoscopic resection of advanced and laterally spreading duodenal papillary tumors. Dig Endosc 2016;28:121–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Napoleon B, Gincul R, Ponchon T, et al. Endoscopic papillectomy for early ampullary tumors: long-term results from a large multicenter prospective study. Endoscopy 2014;46:127–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Ceppa EP, Burbridge RA, Rialon KL, et al. Endoscopic versus surgical ampullectomy: an algorithm to treat disease of the ampulla of Vater. Ann Surg 2013;257:315–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Yandrapu H, Desai M, Siddique S, et al. Normal saline solution versus other viscous solutions for submucosal injection during endoscopic mucosal resection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc 2017;85:693–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Menees SB, Schoenfeld P, Kim HM, et al. A survey of ampullectomy practices. World J Gastroenterol 2009;65:AB218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].De Palma GD. Endoscopic papillectomy: indications, techniques, and results. World J Gastroenterol 2014;20:1537–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Binmoeller KF, Boaventura S, Ramsperger K, et al. Endoscopic snare excision of benign adenomas of the papilla of Vater. Gastrointest Endosc 1993;39:127–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Beger HG, Staib L, Schoenberg MH. Ampullectomy for adenoma of the papilla and ampulla of Vater. Langenbecks Arch Surg 1998;383:190–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Han J, Kim MH. Endoscopic papillectomy for adenomas of the major duodenal papilla (with video). Gastrointest Endosc 2006;63:292–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Yamasaki Y, Uedo N, Takeuchi Y, et al. Current status of endoscopic resection for superficial nonampullary duodenal epithelial tumors. Digestion 2018;97:45–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Cheng CL, Sherman S, Fogel EL, et al. Endoscopic snare papillectomy for tumors of the duodenal papillae. Gastrointest Endosc 2004;60:757–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Irani S, Arai A, Ayub K, et al. Papillectomy for ampullary neoplasm: results of a single referral center over a 10-year period. Gastrointest Endosc 2009;70:923–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Martin JA, Haber GB. Ampullary adenoma: clinical manifestations, diagnosis, and treatment. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am 2003;13:649–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Desilets DJ, Dy RM, Ku PM, et al. Endoscopic management of tumors of the major duodenal papilla: refined techniques to improve outcome and avoid complications. Gastrointest Endosc 2001;54:202–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Ponchon T, Berger F, Chavaillon A, et al. Contribution of endoscopy to diagnosis and treatment of tumors of the ampulla of Vater. Cancer 1989;64:161–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Shemesh E, Nass S, Czerniak A. Endoscopic sphincterotomy and endoscopic fulguration in the management of adenoma of the papilla of Vater. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1989;169:445–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Norton ID, Geller A, Petersen BT, et al. Endoscopic surveillance and ablative therapy for periampullary adenomas. Am J Gastroenterol 2001;96:101–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Catalano MF, Linder JD, Chak A, et al. Endoscopic management of adenoma of the major duodenal papilla. Gastrointest Endosc 2004;59:225–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Vogt M, Jakobs R, Benz C, et al. Endoscopic therapy of adenomas of the papilla of Vater. A retrospective analysis with long-term follow-up. Dig Liver Dis 2000;32:339–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Patel R, Davitte J, Varadarajulu S, et al. Endoscopic resection of ampullary adenomas: complications and outcomes. Dig Dis Sci 2011;56:3235–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Nguyen N, Shah JN, Binmoeller KF. Outcomes of endoscopic papillectomy in elderly patients with ampullary adenoma or early carcinoma. Endoscopy 2010;42:975–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].El H, II, Cote GA. Endoscopic diagnosis and management of ampullary lesions. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am 2013;23:95–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Harewood GC, Pochron NL, Gostout CJ. Prospective, randomized, controlled trial of prophylactic pancreatic stent placement for endoscopic snare excision of the duodenal ampulla. Gastrointest Endosc 2005;62:367–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]