Abstract

To identify target antigens for prostate cancer therapy, we have combined computer-based screening of the human expressed sequence tag database and experimental expression analysis to identify genes that are expressed in normal prostate and prostate cancer but not in essential human tissues. Using this approach, we identified a gene that is expressed specifically in prostate cancer, normal prostate, and testis. The gene has a 1.5-kb transcript that encodes a protein of 14 kDa. We named this gene PATE (expressed in prostate and testis). In situ hybridization shows that PATE mRNA is expressed in the epithelial cells of prostate cancers and in normal prostate. Transfection of the PATE cDNA with a Myc epitope tag into NIH 3T3 cells and subsequent cell fractionation analysis shows that the PATE protein is localized in the membrane fraction of the cell. Analysis of the amino acid sequence of PATE shows that it has structural similarities to a group of proteins known as three-finger toxins, which includes the extracellular domain of the type β transforming growth factor receptor. Restricted expression of PATE makes it a potential candidate for the immunotherapy of prostate cancer.

Keywords: immunotherapy‖cancer vaccine‖snake toxin‖membrane protein

Prostate cancer is the most frequently diagnosed noncutaneous cancer and the second leading cause of cancer deaths in men. It has been estimated that about one in five men in the United States will develop prostate cancer during their lifetime, and, to date, there are no curative therapies available for this disease after it has metastasized from its site of origin. It is of great importance to identify specific molecular targets for prostate cancer, which can be used as early detection markers or for the targeted therapy of prostate cancer.

Our laboratory is interested in developing an immunobased, targeted therapy for the treatment of cancer and other diseases. For these therapies to be effective, it is important that the antigen is present on tumor cells and is not expressed on essential normal cells such as liver, heart, brain, and kidney. To achieve this goal, we have focused on the identification of new, tissue-specific antigens by using the expressed sequence tag (EST) database to generate clusters of ESTs that are expressed in normal prostate and/or prostate cancer but not in essential human tissues (1). Using this approach, we previously have identified several genes whose transcripts are expressed specifically in normal prostate and/or prostate cancer (2–6). Using the same approach, we describe here another gene that is expressed specifically in prostate cancer, normal prostate, and testis. We named this gene PATE for the gene expressed in prostate and testis.

Materials and Methods

Primers.

The nucleotide sequences of the primers used in this study are as follows: T339, 5′-GTG CTC CAG AGG AAG AGG AAT ATG CAC A-3′; T340, 5′-CAT TGT GAA GAG GCT GAG GCA ACA ACC T-3′; T364, 5′-GGG GAC AAG TTT GTA CAA AAA AGC AGG CTC GGA GAA CCT GTA CTT CCA GTC CAT GTG CCA CCT CCA GTT CCC A-3′; and T365, GGG GAC CAC TTT GTA CAA GAA AGC TGG GTT ATT ACT AAA GGT CTT CAT TGC ACA GG-3′.

Dot-Blot and Northern Blot Hybridizations.

The human multiple tissue RNA dot-blot (RNA Masterblot; CLONTECH) and Northern blot (Multiple Tissue Northern blot; CLONTECH) hybridizations were carried out as described previously (7). Briefly, the RNA membranes were prehybridized for more than 2 h in hybridization solution (Hybrisol I; Oncor) at 45°C. The probe labeled with 32P by random primer extension (Lofstrand Laboratories, Gaithersburg, MD) was added to the blots and hybridized for another 16 h. The blots then were washed twice for 15 min each in 2×SSC/0.1% SDS at room temperature and then washed twice for 15 min each in 0.2×SSC/0.1% SDS at 60°C. Finally, the membranes were exposed on x-ray film for 1–2 days.

Reverse Transcription–PCR Analysis.

PCR was performed on cDNA from 24 different human tissues by using the Rapid-Scan gene expression panel (OriGene Technologies, Rockville, MD). The thermocycling protocol was initial denaturation at 94°C for 3 min, 35 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 1 min, annealing at 65°C for 1 min, and elongation at 72°C for 2 min. The PCR primers used were T339 and T340. The PCR products were analyzed on 1.5% agarose gels.

In Situ Hybridization.

In situ hybridization of PATE mRNA on prostate cancer tissues was performed as described earlier (6, 8). Biotinylated probes were prepared by using PATE (1,500 bp) and U6 (250 bp) cDNA cloned in pBluescript II SK(+) plasmid, using the BioNick Labeling System kit (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Biotinylated pBluescript II (+) without any insert was used as a negative control. Slides were hybridized by using the in situ Hybridization and Detection System (Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The slides were counterstained by using 0.2% Light Green stain, rinsed through a series of alcohol grades, and mounted in Cytoseal (Stephens Scientific, Riverdale, NJ). Microscopic evaluation was performed by using a Nikon Eclipse 800 microscope.

Rapid Amplification of cDNA Ends (RACE) PCR.

RACE was performed on Marathon Ready normal prostate and testis cDNA (CLONTECH). The gene-specific primer used for the 5′ RACE was T340. The 5′ RACE PCR product was gel-purified (QIAquick gel extraction; Qiagen) and cloned into the pCR2.1 TOPO vector (Invitrogen). Clones were analyzed by restriction digestion using EcoRI. The longest clones were sequenced by using Perkin–Elmer's dRhodamine terminator sequencing kit.

In Vitro Translation.

The in vitro transcription and translation of the PATE cDNA was carried out by using T7 RNA polymerase and wheat germ extract (TNT; Promega) and following the manufacturer's instructions. [35S]Methionine (ICN) was incorporated in the reaction for visualization of translated products. The reaction mixture was heated at 95°C in reducing sample buffer and then analyzed under reducing conditions on a polyacrylamide gel (18% PAGE/Tris–glycine; Bio-Rad) together with a prestained protein molecular weight marker (Bio-Rad). The gel was dried and subjected to autoradiography.

Preparation of Cell Extracts and Western Blot Analysis.

NIH 3T3 cells were transiently transfected with a eukaryotic expression plasmid (pcDNA3.1-Myc-His) expressing PATE with a Myc epitope tag at the carboxyl terminus. Forty-eight hours after transfection, cells were harvested and analyzed. Whole-cell, cytoplasmic, membrane, and nuclear protein extracts were prepared as described previously (4). Twenty-five micrograms of protein extracts (5 μg for subcellular fractions) was run on a 18% Tris–glycine gel (Bio-Rad) and transferred to a 0.2-μm poly(vinylidene difluoride) membrane (Bio-Rad) in transfer buffer [25 mM Tris/192 mM glycine/20% (vol/vol) methanol, pH 8.3] at 4°C for 3 h at 30 V. Filters were probed with 10 μg/ml anti-Myc-tag monoclonal (9E10) antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and their respective signals were detected by using a chemiluminescence Western blotting kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Indianapolis, IN).

Results

Computer Analysis of GS1 Cluster.

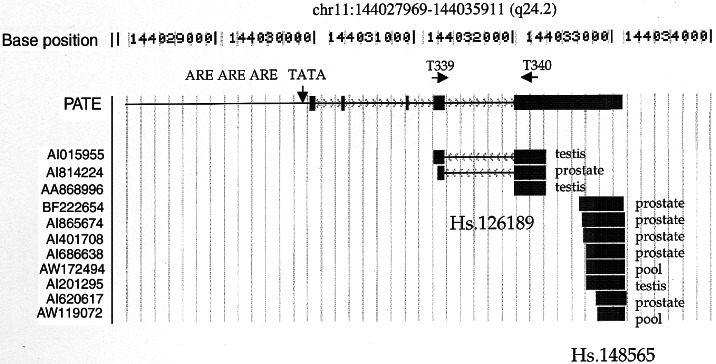

The GS1 cluster (Unigene clusters Hs.126189 and Hs.148565) was identified by computer analysis as partially prostate- and testis-specific (Fig. 1). There are a total of 11 ESTs: 6 are from prostate, 3 are from testis, and 2 are from RNA prepared from a pool of tissues containing testis, fetal lung, and B cells. All ESTs are localized to chromosome 11q24.2 on the human genome.

Figure 1.

Schematics show the alignment of ESTs of PATE into chromosome 11q24.2. Unigene cluster Hs.148565 (GS1) is 532 bp in length and contains five ESTs from prostate library, one from testis library, and two from library of pool of tissues. The positions of TATA box and potential ARE are shown. Locations of the PCR primers T339 and T340 are also shown.

Specificity of GS1 Cluster.

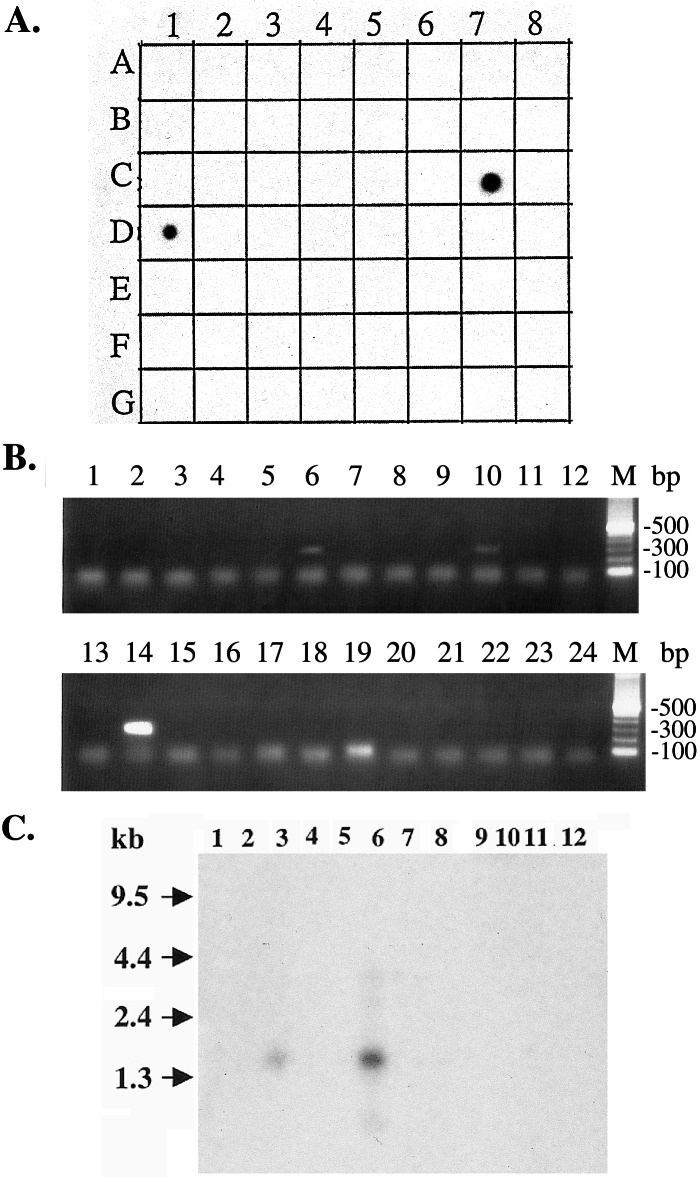

To determine experimentally the tissue specificity of the GS1 cluster, we performed a multitissue dot-blot analysis using a PCR-generated DNA fragment from the cluster as a probe. As shown in Fig. 2A, among the 50 different samples of normal and fetal tissue examined, GS1 is detected only in prostate (C7) and testis (D1) but not in essential tissues such as brain (A1), heart (C1), kidney (E1), liver (E2), lung (F2), and adrenal gland (D5). Because GS1 is expressed in prostate and testis, we named the gene PATE. To confirm the dot-blot result, we used a more sensitive, PCR-based analysis to validate tissue-specific expression of PATE. In this analysis, we used a panel of cDNAs isolated from 24 different normal tissues and performed PCRs with a primer pair (T339 and T340) designed from the DNA sequence of GS1 cluster. As shown in Fig. 2B, a strong, specific band of 300 bp was detected in testis (lane 14). There also was a signal detected in prostate (lane 6) and a weak signal in adrenal gland (lane 10). No expression was detected in essential tissues such as lung (lane 18), liver (lane 20), brain (lane 24), kidney (lane 22), and heart (lane 23). These data validate the computer analysis and indicate the cluster is specific for testis and prostate with some expression in adrenal gland.

Figure 2.

Tissue distribution of PATE mRNA expression. (A) RNA hybridization of a multiple tissue dot-blot containing mRNA from 50 normal human cell types or tissues by using a cDNA probe from the 3′ end of the PATE transcript. Strong expression is observed in prostate (C7) and testis (D1) samples, but no detectable expression is observed in brain (A1), heart (C1), kidney (E1), liver (E2), lung (F2), and adrenal gland (D5). (B) PCR on cDNAs from 24 different human tissues (Rapid Scan panel; OriGene Technologies). The expected size of the PATE PCR product is 300 bp. A strong, 300-bp PCR product is detected in testis (lane 14). Weaker bands are detected in prostate (lane 6) and adrenal gland (lane 10). (C) Northern blot analysis showing expression and transcript sizes of PATE in different normal tissues. PCR probe generated from the PATE cluster was used for hybridization. The predominant transcript is about 1.5 kb in size and is highly expressed in prostate (lane 6). The signal in testis (lane 3) is weak, and there is no detectable signal in breast (lane 1), bone marrow (lane 2), ovary (lane 4), uterus (lane 5), stomach (lane 7), bladder (lane 8), spinal cord (lane 9), brain (lane 10), pancreas (lane 11), and thyroid (lane 12).

Full-Length cDNA Cloning of PATE.

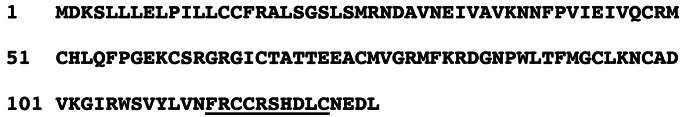

To determine the transcript size of PATE, we performed a Northern blot analysis using a blot containing mRNAs from different tissues including prostate and testis. The PCR-generated probe that was used for dot-blot analysis also was used in this experiment. As shown in Fig. 2C, a band of about 1.5 kb in size is detected in both the prostate (lane 6) and testis (lane 3). The intensity of the band detected in the prostate sample is much higher than the intensity observed in testis. To isolate the full-length cDNA for PATE, we used the 5′ and 3′ RACE PCR method and isolated a clone 1.5 kb in size. Complete nucleotide sequence (deposited in GenBank with accession number AF462605) of the cDNA reveals that it has an ORF of 127 aa (Fig. 3). The estimated molecular mass of the protein encoded by the PATE cDNA is about 14.3 kDa. The amino acid sequence analysis of the predicted ORF shows that PATE is a cysteine-rich protein with a phospholipase A2 motif at the carboxyl terminus (underlined).

Figure 3.

Amino acid sequence encoded by PATE. Putative phospholipase A2 motif is underlined.

Genomic Organization and Analysis of the Promoter Region of PATE.

blast analysis of the PATE cDNA against the human genome sequence demonstrates that PATE is localized at chromosome 11q24. It is composed of five exons and four introns and is spread across only about a 3.5-kb region. The genomic sequence of this region of the chromosome is complete and enabled us to analyze the promoter region of the PATE gene (Fig. 1). Examination of the sequence upstream of the PATE transcript reveals a perfect TATA box at −48-bp region from the start of the transcript. There are also three potential androgen response elements (ARE) upstream of the transcription start site, indicating that PATE expression may be regulated by androgen (Fig. 1).

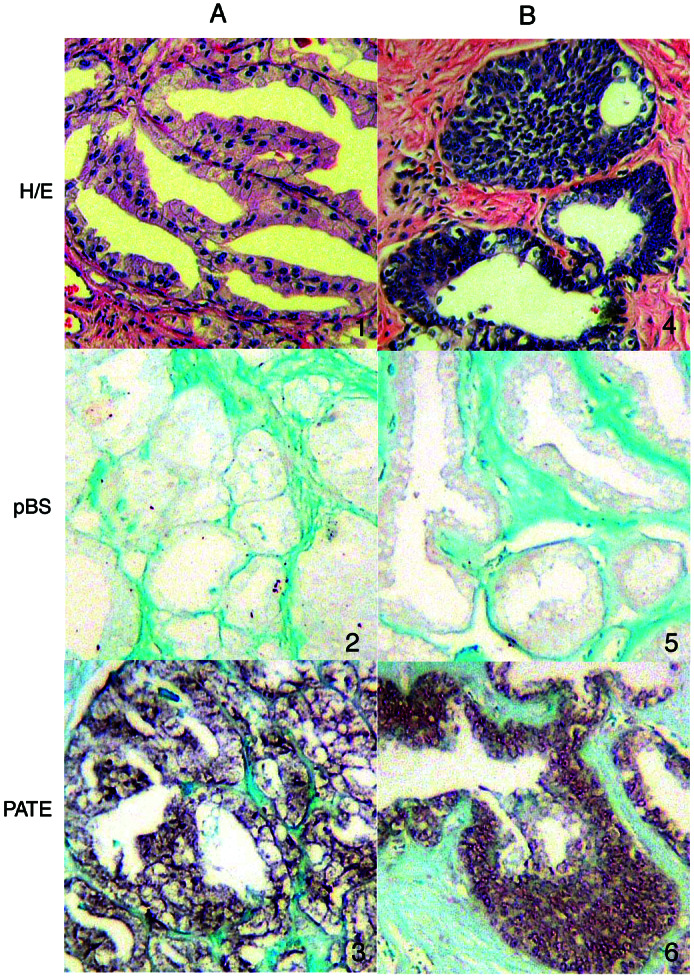

PATE mRNA Is Expressed in Epithelial Cells of Normal Prostate and Prostate Cancer.

To determine the cell types in normal prostate and prostate cancer that express PATE mRNA, we used in situ hybridization with a biotin-labeled PATE cDNA as a probe as described in Materials and Methods. As shown in Fig. 4, PATE mRNA is highly expressed in prostatic epithelial cells of two prostate cancer specimens. There is no signal with a probe that does not contain the PATE insert, indicating the specificity of the hybridization reaction; also, there is no detectable signal in cells in the stromal compartment of the tissue, indicating that PATE is specifically expressed in the epithelial cells of the prostate.

Figure 4.

In situ localization of PATE mRNA. A and B represent two prostate cancer samples. (Top) Prostate tissue section stained with hematoxylin/eosin shows the general morphology and the types of cells (1 and 4). (Middle) Prostate tissue section probed with plasmid Bluescript vector (without any cDNA insert) as a negative control (2 and 5). Note the absence of signal. (Bottom) Prostate tissue section probed with PATE (3 and 6). Note the strong signal in the tumor cells.

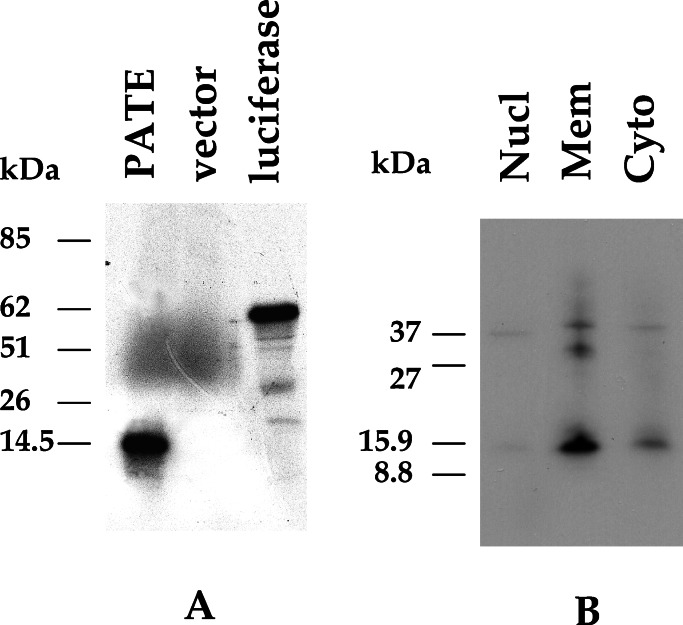

The PATE Transcript Encodes a 14-kDa Membrane-Associated Protein.

Analysis of the sequence of the PATE cDNA indicates that it has a predicted ORF of 127 aa and an estimated molecular mass of 14.3 kDa. To determine the size of the protein encoded by the PATE cDNA, in vitro transcription and coupled translation were performed by using the T7 RNA polymerase and wheat germ extract system. As shown in Fig. 5A, PATE cDNA produced a specific band of about 14 kDa, whereas the empty vector produced no specific protein product. A plasmid containing luciferase cDNA was used as a positive control and gave rise to an expected 62-kDa product.

Figure 5.

Analysis of the protein product encoded by PATE. (A) Analysis of the in vitro translated products of PATE cDNA. PATE cDNA was transcribed in vitro with T7 RNA polymerase and the RNA was translated with wheat germ extract in the presence of [35S]methionine. The translated products were analyzed by SDS/PAGE and fluorography. Lanes: 1, PATE cDNA; 2, empty vector control; 3, luciferase cDNA as positive control. (B) Western blot analysis of PATE-transfected cell extract with anti-Myc-tag antibody. A specific band of molecular mass of about 16 kDa is detected by anti-Myc-tag antibody in the membrane fraction of the transfected cell line.

To determine the subcellular localization of PATE, we constructed a eukaryotic expression plasmid (pcDNA3.1/PT-Myc-His) expressing PATE with a Myc-His epitope tag at the carboxyl terminus. We prepared nuclear, cytoplasmic, and membrane fractions from NIH 3T3 cells transiently transfected with the expression plasmid pcDNA3.1/PT-Myc-His. As shown in Fig. 5B, a strong, specific band at a molecular mass of about 16.0 kDa (14-kDa PATE with 2 kDa from the tag) is detected in the lane containing protein extracts from the membrane fraction when anti-Myc-tag mAb was used. There is a very weak band of similar size in the cytoplasmic fraction. There is no detectable signal from the extract of the cells transfected with empty vector (data not shown). This result indicates that the PATE gene encodes a 14-kDa protein and the protein is associated with the membrane fraction of the cell.

Discussion

Using the EST database as a guide, we identified a gene, PATE, that is highly expressed in prostate cancer, normal prostate, and testis. PATE RNA is expressed in the epithelial cells of prostate cancer and normal prostate tissues.

PATE is a small protein with a molecular mass of 14 kDa. When PATE protein sequences were analyzed by using the ExPASy site (http://www.expasy.org/) for signal peptide prediction, the signalp program predicted a 21-aa signal peptide with a likely cleavage site between G21 and S22. This finding suggests that PATE is processed and then either is secreted or remains bound to the cell membrane. Transfection experiments reveal that PATE is associated with the membrane fraction. A blastp run (9) against the National Center for Biotechnology Information's nr database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ blast/) by using the PATE putative protein sequence resulted in hits to the acrosomal vesicle proteins, SP-10, with e-scores between 0.003 and 0.07. The acrosomal vesicle protein SP-10 may be involved in sperm-zona binding and penetration (10). The aligned part of the SP-10 protein belongs to a snake toxin family of proteins according to the sequence-based protein classification database Pfam (11).

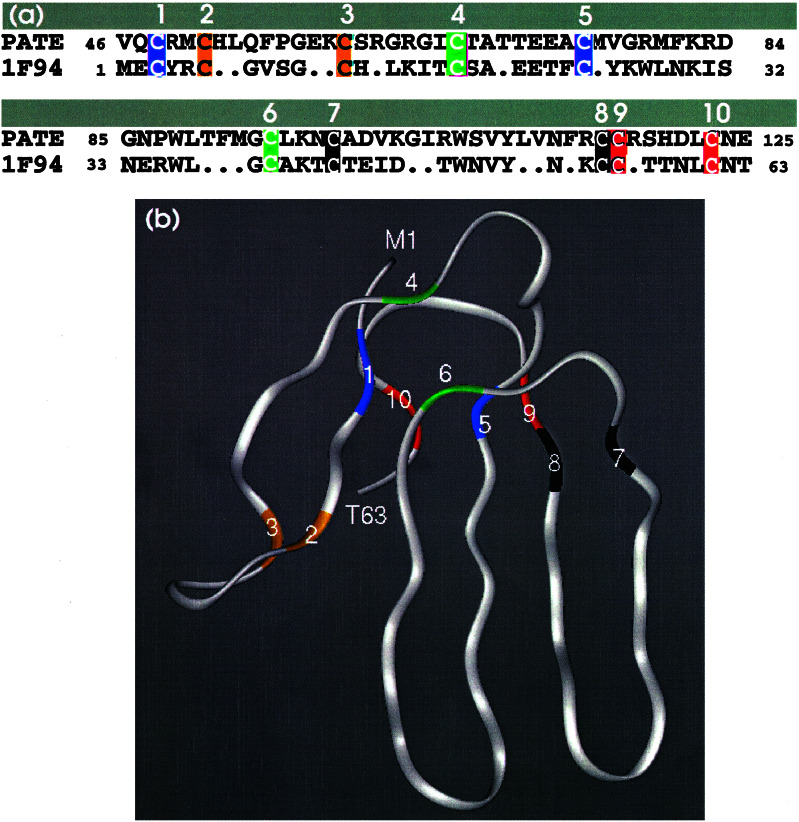

When fold-recognition programs were run for the PATE amino acid sequence, three different programs, 3d-pssm (12), genthreader (13), and bioinbgu (14), predicted a protein in the same snake toxin family (PDB ID codes 1f94 or 1cdt) as the highest scoring hit with high to medium prediction confidence.

According to the manually procured protein structure classification database SCOP (15), the superfamily of protein structures that contains the snake venom toxin also includes many neurotoxins and cardiotoxins. It also contains CD59 (16, 17) and an extracellular domain of the activin receptor (18). The recently described bone morphogenic protein receptor contains a domain of similar structure (19). These structures contain five or six β-strands that extend like the fingers of a hand, which are tied together in the “palm” region of the molecule by four or five disulfide bonds (Fig. 6). PATE contains 12 cysteines, two of which are in the putative signal sequence. The receptor proteins are homologous to the extracellular domain of the type β transforming growth factor receptor and urokinase-type plasminogen activator (20). These are transmembrane proteins that bind the type β transforming growth factor family of cytokines and relay their signal through phosphorylation of other proteins. CD59 is a member of the ly6 superfamily. It is a cell-surface glycoprotein anchored to the membrane by means of glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI). It is believed to interfere with the full assembly of the membrane-attack complex of the complement system (21). The prostate stem cell antigen (22) also belongs to this family of 10 cysteine proteins.

Figure 6.

Alignment of PATE with a three-finger toxin family member 1F94_A. (a) The alignment was performed manually first by aligning the 10 cysteines and then arranging the rest of the residues for the best alignment. The cysteine residues are numbered serially. Cysteines with same color are disulfide-bonded to each other. (b) Ribbon diagram (using insight ii; Biosym Technologies, San Diego) of the x-ray structure of 1F94_A. The color and the numbering of the cysteine residues correspond to a.

The number and pattern of cysteine residues in the PATE sequence, as well as partial sequence homology and the results of several protein fold prediction programs, suggest that PATE protein may have a structure similar to these proteins. The PATE sequence does not appear to have a transmembrane segment or the motif for the GPI anchor that CD59 and PSCA proteins have; therefore, it may be anchored to the membrane by interaction with another protein or means of some other lipid molecule. In fact, the common characteristic of all of the proteins with this structure is that they interact with other proteins; PATE can also be expected to be involved in protein—protein interactions.

PATE is the fifth small protein (below 20 kDa) that we have identified and characterized in our search for new genes highly expressed in the prostate. The other four are PAGE4 (16 kDa), TARP (7 kDa), PRAC (6 kDa), and GDEP (4 kDa) (3, 4, 6, 7). To date, there are few prostate-specific markers reported in the literature. The best known and well characterized markers are prostate-specific antigen (PSA) (23) and prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA) (24). Other reported prostate-specific markers are DD3 (25), PSCA (22), PCGEM1 (26), STEAP (27), and Trp-P8 (28).

The PATE promoter region has three putative ARE, suggesting that its expression is probably regulated by androgen. The TARP promoter, like that of PATE, also has ARE and is induced by testosterone treatment of LnCAP cells (29).

One wonders why these proteins have not been identified previously by standard techniques of protein purification or by identification of proteins with immune sera prepared against prostate cancer cell lines. We believe there are several possible reasons. First, these proteins are made at low levels or are undetectable in prostate cancer cell lines. Second, they are small and difficult to visualize on SDS gels. Third, because of their small size or sequence conservation, they may induce a poor immune response.

In conclusion, PATE is a novel gene expressed in prostate cancer, normal prostate, and testis that may be a useful molecular target for prostate cancer therapy.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. K. Egland and K. Santora for their comments, Steve Neal for photography, and Anna Mazzuca for editorial assistance.

Abbreviations

- EST

expressed sequence tag

- PATE

expressed in prostate and testis

- RACE

rapid amplification of cDNA ends

- ARE

androgen response element(s)

Footnotes

Data deposition: The sequence reported in this paper has been deposited in the GenBank database (accession no. AF462605).

References

- 1.Vasmatzis G, Essand M, Brinkmann U, Lee B, Pastan I. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:300–304. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.1.300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Essand M, Vasmatzis G, Brinkmann U, Duray P, Lee B, Pastan I. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:9287–9292. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.16.9287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brinkmann U, Vasmatzis G, Lee B, Yerushalmi N, Essand M, Pastan I. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:10757–10762. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.18.10757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wolfgang C D, Essand M, Vincent J J, Lee B, Pastan I. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:9437–9442. doi: 10.1073/pnas.160270597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brinkmann U, Vasmatzis G, Lee B, Pastan I. Cancer Res. 1999;59:1445–1448. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Olsson P, Bera T K, Essand M, Kumar V, Duray P, Vincent J, Lee B K, Pastan I. Prostate. 2001;48:231–241. doi: 10.1002/pros.1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu X F, Olsson P, Wolfgang C D, Bera T K, Duray P, Lee B, Pastan I. Prostate. 2001;47:125–131. doi: 10.1002/pros.1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kumar V, Collins F H. Insect Mol Biol. 1994;3:41–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2583.1994.tb00149.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Altschul S F, Madden T L, Schaffer A A, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman D J. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Foster J A, Klotz K L, Flickinger C J, Thomas T S, Wright R M, Casillo J R, Herr J C. Biol Reprod. 1994;51:1222–1231. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod51.6.1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bateman A, Birney E, Durbin R, Eddy S R, Finn R D, Sonnhammer E L. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:260–262. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.1.260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kelley L A, MacCullum R M, Sternberg M J. J Mol Biol. 2000;299:499–520. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jones D T. J Mol Biol. 1999;287:797–815. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fischer D. In: Pacific Symposium on Biocomputing. Altman R B, Dunker A K, Hunter L, Klein T E, editors. Teaneck, NJ: World Scientific; 2000. pp. 119–130. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Murzin A G, Brenner S E, Hubbard T, Chothia C. J Mol Biol. 1995;247:536–540. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fletcher C M, Harrison R A, Lachmann P J, Neuhaus D. Structure. 1994;2:185–199. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(00)00020-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kieffer B, Driscoll P C, Campbell I D, Willis A C, Vandermerwe P A, David S J. Biochemistry. 1994;33:4471–4482. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Greenwald J, Fischer W H, Vale W W, Choe S. Nat Struct Biol. 1999;6:18–22. doi: 10.1038/4887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kirsch T, Sebald W, Dreyer M K. Nat Struct Biol. 2000;7:492–496. doi: 10.1038/75903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jokiranata T S, Tissari J, Teleman O, Meri S. FEBS Lett. 1995;376:31–36. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)01239-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Davies A, Lachmann P J. Immunol Res. 1993;12:258–275. doi: 10.1007/BF02918257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reiter R E, Gu Z N, Watabe T, Thomas G, Szigeti K, Davis E, Wahl M, Nisitani S, Yamashiro J, Le Beau M M, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:1735–1740. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.4.1735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wolfgang C D, Essand M, Lee B K, Pastan I. Cancer Res. 2001;61:8122–8126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Young C Y F, Andrews P E, Tindall D J. J Androl. 1995;16:97–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Israeli R S, Powell C T, Fair W R, Heston W D W. Cancer Res. 1993;53:227–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bussemakers M J G, van Bokhoven A, Verhaegh G W, Smit F P, Karthaus H F M, Schalken J A, Debruyne F M J, Ru N, Issacs W B. Cancer Res. 1999;59:5975–5979. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Srikantan V, Zou Z Q, Petrovics G, Xu L, Augustus M, Davis L, Livezey J K, Connell T, Sesterhenn I A, Yoshino K, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:12216–12221. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.22.12216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hubert R S, Vivanco I, Chen E, Rastegar S, Leong K, Mitchell S C, Madraswala R, Zhou Y H, Kuo J, Raitano A B, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:14523–14528. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.25.14523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tsavaler L, Shapero M H, Morkowski S, Laus R. Cancer Res. 2001;61:3760–3769. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]