Abstract

Background

Petrovinema skrjabini (Nematoda: Strongylidae, Cyathostominae) is a parasitic nematode colonizing the cecum and colon of equids. Like other cyathostomins, its larvae (L3) invade the intestinal mucosa, forming encysted nodules that may remain dormant for years. Mass larval emergence triggers larval cyathostominosis—a severe syndrome characterized by hemorrhagic typhlocolitis and diarrhea, with mortality rates exceeding 50%. However, owing to the morphological indistinguishability of cyathostomin and frequent mixed infections in natural settings, species-specific contributions to pathogenesis remain unresolved. Previous studies on P. skrjabini have predominantly focused on its morphology, with limited molecular information available.

Methods

The complete mitogenome of Petrovinema skrjabini was sequenced using the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform, followed by assembly and annotation. We performed a phylogenetic analysis using Bayesian inference (BI) and maximum likelihood (ML) methods, based on 12 protein-coding genes from mitogenomes, to assess the evolutionary relationships of 34 Strongylidae species.

Results

The complete mitogenome of P. skrjabini comprises 13,885 base pairs with 12 protein-coding genes, two ribosomal-RNA genes, 22 transfer-RNA genes, and two non-coding regions. The gene arrangement of the P. skrjabini mitogenome was consistent with the GA3 arrangement found in other Strongylidae species. The mitogenome exhibited a high AT bias (75.4%), which is consistent with other species in other Strongylidae species. Phylogenetic analysis showed that two Strongylus species (belonging to subfamily Strongylinae) formed a clade and located in the base of Strongylidae, while three Triodontophorus (belonging to subfamily Strongylinae) species and P. skrjabini formed another clade within in subfamily Cyathostominae within Strongylidae, based on 12 protein-coding genes from mitogenomes, suggesting that the genus Triodontophorus should transfer to the subfamily Cyathostominae.

Conclusions

The characterization of the complete mitochondrial genomes of P. skrjabini is reported for the first time. This study provided helpful genetic markers for P. skrjabini identification and taxonomy, facilitating early nematode diagnosis and treatment to decrease equine parasitic nematode burdens. Our mitochondrial phylogeny analyses further corroborate the hypothesis that the genus Triodontophorus belongs to Cyathostominae. The present study enriches the database of strongylids mitogenomes and provides a new insight into the systematics of the family Strongylidae.

Graphical Abstract

Keywords: Petrovinema skrjabini, Cyathostominae, Mitochondrial genome, Phylogenetic analysis, Equus ferus przewalskii

Background

Strongylids (Nematoda: Strongylidae) are a group of parasitic nematodes that co-infect the gastrointestinal tracts of equids [1–3], with veterinary and economic importance for domestic animals and wildlife [4–10]. Co-infecting nematode species can interact within the host, changing infection dynamics and transmission, with implications for host diseases [11–14]. Hence, a detailed understanding of strongylid species and how they infect the host is essential.

Studies on strongylid communities in equids rely heavily upon the morphological identification of specimens collected from feces or culled animals [15]. This method is challenging and labor-intensive, limiting the number of hosts that can be examined and requiring considerable expertise [15, 16]. Traditionally, Strongylidae is divided into two subfamilies, Strongylinae (large strongyles with globular or funnel-shaped buccal capsules) and Cyathostominae (small strongyles with cylindrical buccal capsules), based solely on morphological characteristics [22]. However, molecular studies are inconsistent with morphological classification criteria [19, 25–27]. For instance, Gao et al. showed through mitochondrial genome analyses that the genus Triodontophorus, morphologically assigned to Strongylinae, cluster within Cyathostominae in mitochondrial phylogenies [30], demonstrating the limitations of relying solely on buccal capsule morphology. These findings highlight the need for molecular approaches to reconcile taxonomic uncertainties. Advances in molecular technologies open promising avenues for nematode research, providing tools for species identification, exploring molecular evolution, and conducting phylogenetic studies [17–21]. To date, approximately 64 species from 19 genera in the Strongylidae family have been described [22]; however, only 22 compete mitogenomes belonging to 8 genera within Strongylidae are available in the GenBank Database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.gov/; accessed on 20 November 2023) [23, 24].

Petrovinema, described by Ershov in 1943, belongs to the phylum Nematoda, family Strongylidae, and subfamily Cyathostominae. It primarily infects equids such as donkeys and horses. Infection occurs via the fecal–oral route, causing symptoms such as subcutaneous edema, diarrhea, fever, and emaciation, with approximately 50% mortality [4, 28]. In 1975, Lichtenfels classified two species of Petrovinema, P. skrjabini and P. poculatum, into the genus Cylicostephanus. In 1986, Hartwich suggested that two species of Petrovinema transferred to the genus of Cylicostephanus is unreasonable based on morphological characteristics [22], which supported using the ITS 2 sequence by Hung et al. and recognized Petrovinema as an independent genus [23]. Currently two species of the genus Petrovinema are accepted: P. skrjabini and P. poculatum. In comparison with that of P. poculatum, the distribution range of P. skrjabini is relatively limited, has only been reported in Asia [22, 29], and lacks molecular data, which, to a certain extent, hinders the attainment of a comprehensive understanding of this strongylid species. Advanced studies of the genus Petrovinema have mainly focused on morphological evidences, while only a small number of studies have addressed their phylogenetic relationships based on molecular sequences, especially those including mitogenomes [22].

Therefore, this study addresses this critical gap by determining the complete mitogenome of P. skrjabini,, which will enable a more accurate identification of the species, and thus help to determine the specific parasite type of infection. Moreover, we sought to resolve taxonomic controversies related to the Strongylidae family.

Methods

Sample collection and DNA extraction

Petrovinema skrjabini specimens were collected from Equus ferus przewalskii dewormed with ivermectin in the Kalamaili Nature Reserve (Xinjiang, China). The specimens were thoroughly washed with saline solution, fixed in 70% ethanol, and stored at −40 °C. Nematodes were identified using a compound microscope (Olympus CX22, Japan), with reference to taxonomic keys and descriptions [22]. A tissue sample was taken from an adult P. skrjabini specimen for DNA extraction. The remaining body parts of the specimen were preserved as vouchers, labeled with the number 418–6, and then deposited in the Museum of Beijing Forestry University (Ne-418). DNA was extracted using the QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit, following the manufacturer’s instructions (Qiagen, GmbH, Germany), and eluted from the column using 200 μL of deionized water.

DNA annotation, sequence analysis, and comparative analysis

To survey the P. skrjabini genome, we generated TruSeq libraries using the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform (with 150 base pair [bp] paired-end reads) at Berry Genomics in China. Trimmomatic v0.38 [30] was used to eliminate highly redundant and low-quality sequences from the FASTQ data generated using the Illumina platform. De novo assemblies were created using IDBA-UD (http://i.cs.hku.hk/~alse/hkubrg/projects/idba_ud/) with a similarity threshold of 98% and k-values ranging from 80 to 124 bp considered. The COXI gene (GenBank: KP693427.1) sequences of close relatives (P. poculatum) served as “bait” references for obtaining the most appropriate and targeted mitochondrial scaffolds. The P. skrjabini mitogenome was annotated using the MITOS webserver [31], and mitochondrial DNA maps were generated utilizing the Proksee Server (https://proksee.ca/).

Protein-coding genes (PCGs) and ribosomal-RNA (rRNA) genes were compared with homologous genes from other strongylid nematodes using MEGA version 6 [32] (Table 1). The AT/GC skew, a metric for assessing strand bias, was computed as described by Perna and Kocher (1995) [33]. To analyze codon usage, the relative synonymous codon usage (RSCU) values of 12 PCGs (with their termination codons removed) were calculated using MEGA v6 [34]. The synonymous (Ks) and non-synonymous (Ka) substitution rates of the PCGs were computed using DnaSP version 5 [35]. We sorted the output data in terms of codon usage and counts and created graphics using the ggplot2 package implemented in R v3.4.1 [36]. Pairwise alignments of the 12 PCGs were conducted using MEGA v6 [32] to identify variable nucleotide sites. Sequence variability across the Strongylidae family, encompassing 22 species (including P. skrjabini), was assessed through sliding-window analysis using DnaSP v5 [37]. The sliding-window analysis was carried out as previously described [38]. To evaluate substitution saturation at each codon position in the PCGs, we employed Xia’s test [39] within the DAMBE.

Table 1.

Species used for reconstructing relationships in the present study

| Superfamily | Family | Subfamily | Species | Locus | Sequence length (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strongyloidea | Strongylidae | Cyathostominae | Cylicodontophorus bicoronatus | NC_042141 | 13,756 |

| Coronocyclus coronatus | OR834861.1 | 13,870 | |||

| Coronocyclus labiatus | NC_042234 | 13,827 | |||

| Coronocyclus labratus | MN832736 | 13,856 | |||

| Cylicocyclus radiatus | NC_039643 | 13,836 | |||

| Cylicocyclus ashworthi | NC_046711 | 13,876 | |||

| Cylicocyclus auriculatus | NC_043849 | 13,831 | |||

| Cylicocyclus elongatus | NC_060748 | 13,875 | |||

| Cylicocyclus insignis | NC_013808 | 13,828 | |||

| Cylicocyclus nassatus | NC_032299 | 13,846 | |||

| Cyathostomum catinatum | NC_035003 | 13,838 | |||

| Cyathostomum pateratum | NC_038070 | 13,822 | |||

| Cyathostomum tetracanthum | MN792800 | 13,839 | |||

| Cylicostephanus goldi | AP017681 | 13,827 | |||

| Cylicostephanus longibursatus | NC_081015.1 | 13,807 | |||

| Cylicostephanus minutus | NC_035004 | 13,826 | |||

| Poteriostomum imparidentatum | NC_035005 | 13,817 | |||

| Strongylus equinus | NC_026868 | 14,545 | |||

| Strongylus vulgaris | GQ888717 | 14,301 | |||

| Triodontophorus brevicauda | NC_026729 | 14,305 | |||

| Triodontophorus nipponicus | NC 031517 | 13,701 | |||

| Triodontophorus serratus | KX185154 | 13,794 | |||

| Chabertiidae | Chabertiinae | Chabertia erschowi | KF660603 | 13,705 | |

| Chabertia ovina | NC_013831 | 13,682 | |||

| Cloacininae | Cloacina communis | NC_067626 | 13,689 | ||

| Oesophagostominae | Oesophagostomum asperum | NC_023932 | 13,672 | ||

| Oesophagostomum columbianum | NC_023933 | 13,561 | |||

| Oesophagostomum dentatum | GQ888716 | 13,869 | |||

| Oesophagostomum quadrispinulatum | NC_014181 | 13,681 | |||

| Phascolostrongylinae | Hypodontus macropi | NC_023098 | 13,634 | ||

| Macropicola ocydromi | NC_023099 | 13,659 | |||

| Syngamidae | – | Syngamus trachea | NC_013821 | 14,647 | |

| Stephanuridae | – | Stephanurus dentatus | MW970029 | 13,735 | |

| Ancylostomatoidea | Ancylostomatidae | Bunostominae | Bunostomum phlebotomum (outgroup) | NC_012308 | 13,790 |

Phylogenetic analyses

Phylogenetic analyses were performed using 12 PCG matrixes from the mitogenome of P. skrjabini (this study) and 33 other Strongyloidea mitogenomes (obtained from the NCBI GenBank database; Table 1), with Bunostomum phlebotomum selected as the outgroup species [40]. Maximum likelihood (ML) and Bayesian inference (BI) analyses were performed using RAxML v8 [41] and MrBayes v3.2.7a [42] as described by Zhao et al. (2021, 2022) [43, 44]. The best substitution models for the 12 PCG sequences were determined using ModelTest-NG software v0.1.7 [45]. The general time-reversible (GTR) + invariable sites (I) + gamma distribution (G) substitution model was used for the ML analysis, involving 1000 bootstrap replications. For the BI analysis, two independent runs of four Markov chains (three heated, one cold) were conducted for two million generations, sampling every 1000 generations. The GTR + I + G substitution model was used. The first 25% of the sampled trees were discarded as burn-in. Convergence of the MCMC chains was assessed by monitoring the average standard deviation of split frequencies, which fell below 0.01. The phylogenetic trees were visualized using the iTOL online tool (https://itol.embl.de) [46].

Results

Composition and organization of the mitogenome

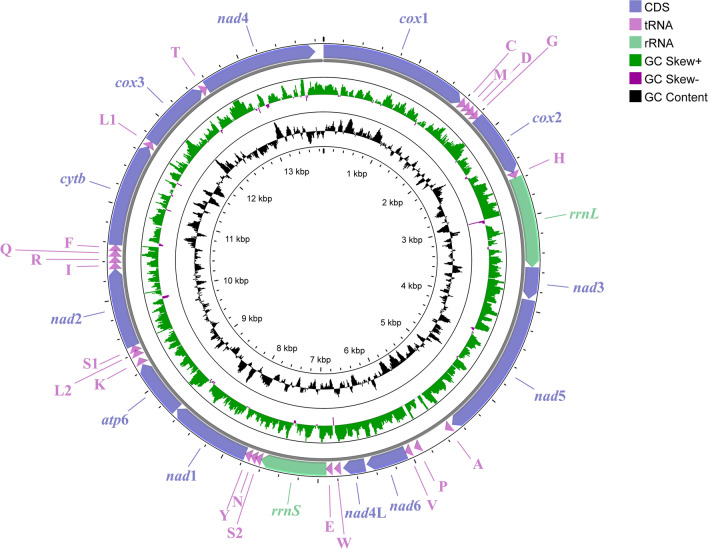

The complete mitogenome of P. skrjabini spanned 13,885 bp in length and contained 36 genes, including atp6, cox1–cox3, cytb, nad1–nad6, and nad4L, as well as the small and large subunit rRNA genes (rrnS and rrnL), 22 tRNA genes (tRNA-Ala, tRNA-Cys, and tRNA-Met, etc.) and two non-coding control regions (NCRs) (Fig. 1; Table 2), and has been deposited in the NCBI database (GenBank accession number: OP784481). All genes were encoded by the same strand, and the gene arrangement (GA) conformed to GA3 [47]. Notably, the P. skrjabini mitogenome contained 16 intergenic spacers, ranging from 1 to 54 bp in length, and five overlaps, reflecting a highly compact organization (Table 2). The overall AT content in the P. skrjabini mitogenome was 75.4%, with an AT skew of −0.20 and a CG skew of 0.42 (Fig. 2). Sliding-window analysis across the 12 PCGs revealed that nad4L had the lowest nucleotide variability, while cytb showed the highest (Fig. 3). Among the most conserved genes were nad4L, cox2, and nad4; whereas, cytb, cox3, and nad6 were the least conserved.

Fig. 1.

Organization of the complete mitochondrial genome of Petrovinema skrjabini

Table 2.

Organization of the complete mitochondrial genome of Petrovinema skrjabini

| Genes/regions | Positions and sequence lengths (bp) | Intergenic nucleotides | Initiation/stop codons |

|---|---|---|---|

| cox1 | 1–1578 (1578) | 0 | ATT/TAA |

| tRNA-Cys(tgc) | 1585–1640 (56) | 6 | |

| tRNA-Met(atg) | 1648–1706 (59) | 7 | |

| tRNA-Asp(gac) | 1708–1765 (58) | 1 | |

| tRNA-Gly(gga) | 1770–1824 (55) | 4 | |

| cox2 | 1825–2520 (696) | 0 | ATT/TAA |

| tRNA-His(cac) | 2520–2573 (54) | −1 | |

| rrnL | 2572–3547 (974) | −2 | |

| nad3 | 3548–3883 (336) | 0 | ATT/TAA |

| nad5 | 3895–5478 (1584) | 11 | ATT/TAA |

| tRNA-Ala(gca) | 5508–5562 (55) | 29 | |

| LNCR | 5563–5889 (326) | 0 | |

| tRNA-Pro(cca) | 5890–5943 (54) | 0 | |

| tRNA-Ser(gta) | 5998–6051 (54) | 54 | |

| nad6 | 6052–6486 (435) | 0 | ATT/TAG |

| nad4L | 6503–6736 (234) | 33 | ATT/TAG |

| tRNA-Trp(tga) | 6770–6826 (57) | 31 | |

| tRNA-Glu(gaa) | 6858–6915 (58) | −1 | |

| rrnS | 6915–7618 (704) | −1 | |

| tRNA-Ser2(tca) | 7618–7670 (53) | 0 | |

| tRNA-Asn(aac) | 7671–7727 (57) | 7 | |

| tRNA-Tyr(tac) | 7735–7789 (55) | 0 | |

| nad1 | 7790–8662 (873) | 1 | TTG/TAG |

| atp6 | 8664–9263 (600) | 12 | ATT/TAA |

| tRNA-Lys(aaa) | 9276–9338 (63) | 34 | |

| tRNA-Leu2(tta) | 9373–9427 (55) | 0 | |

| tRNA-Ser1(aga) | 9428–9479 (52) | 0 | |

| nad2 | 9480–10325 (846) | 2 | TTG/TAG |

| tRNA-Ile(atc) | 10,328–10,387 (60) | 6 | |

| tRNA-Arg(cgt) | 10,394–10,449 (56) | 11 | |

| tRNA-Gln(caa) | 10,461–10,515 (55) | 3 | |

| tRNA-Phe(ttc) | 10,519–10,575 (57) | 0 | |

| cytb | 10,576–11688 (1113) | −1 | ATT/TAA |

| tRNA-Leu1(cta) | 11,688–11,743 (56) | 0 | |

| cox3 | 11,744–12,509 (766) | 0 | ATT/T |

| tRNA-Thr(aca) | 12,510–12,568 (59) | 0 | |

| nad4 | 12,569–13,798 (1230) | 0 | TTG/TAA |

| SNCR | 13,799–13,885 (87) | 0 |

Fig. 2.

A + T content and nucleotide skew of genes, individual elements, and the complete mitogenome of Petrovinema skrjabini

Fig. 3.

Sliding window analysis (window size 300 bp, step size 10 bp) of the alignment of mitochondrial protein-coding sequences of Petrovinema skrjabini used to estimate nucleotide diversity Pi (π) across the alignments. Nucleotide diversity was plotted against the mid-point positions of each window. Gene boundaries are indicated above the graph

PCGs and codon usage

A total length of 10,291 bp was assembled across the 12 PCGs of P. skrjabini, encoding 3419 amino acids (Table 3). The results showed that T was the most prevalent base in all 12 PCGs of P. skrjabini, followed by G, A, and C. The AT contents of the 12 PCGs ranged from 69.65% (cox1) to 79.31% (nad2), with the third codon positions exhibiting the highest AT content (84.55%) compared with the first (72.25%) and second positions (70.35%). The high usage frequencies of codons such as UUU (Phe) and UUA (Leu) contributed to the overall high AT content of the mitogenome, whereas codons such as CUC (Leu) and GUC (Val) were rarely used (Fig. 4A and B).

Table 3.

Lengths and amino acids of mitochondrial genes/regions of 17 Strongylidae species

| Pet. skrjabini | Cya. catinatum | Cya. pateratum |

Cya. tetrac anthum |

Cylicos. goldi | Cylicos. minutus | Cor. labiatus | Cor. labratus | Cylicoc. auriculatus | Cylicoc. insignis | Cylicoc. elongatus | Cylicoc. nassatus | Cylicoc. radiatus | Cylicoc. ashworthi | Cylicod. bicoronatus | Pot. imparidentatum | Str. equinus | Str. vulgaris | Tri. brevicauda | Tri. nipponicus | Tri. serratus | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cox1 | 1578/525 | 1578/525 | 1575/524 | 1578/525 | 1578/525 | 1578/525 | 1578/525 | 1578/525 | 1578/525 | 1578/525 | 1578/525 | 1578/525 | 1578/525 | 1578/525 | 1578/525 | 1578/525 | 1578/525 | 1578/525 | 1578/525 | 1578/525 | 1578/525 |

| cox2 | 696/231 | 696/231 | 696/231 | 696/231 | 696/231 | 696/231 | 696/231 | 696/231 | 696/231 | 696/231 | 696/231 | 696/231 | 696/231 | 696/231 | 696/231 | 696/231 | 696/231 | 697/231 | 696/231 | 696/231 | 696/231 |

| rrnL | 974/– | 976/– | 976/– | 977/– | 972/– | 972/– | 979/– | 975/– | 969/– | 959/– | 968/– | 974/– | 969/– | 978/– | 982/– | 983/– | 959/– | 959/– | 975/– | 976/– | 961/– |

| nad3 | 336/111 | 336/111 | 336/111 | 336/111 | 336/111 | 336/111 | 336/111 | 336/111 | 336/111 | 336/111 | 336/111 | 336/111 | 336/111 | 336/111 | 336/111 | 336/111 | 336/111 | 336/111 | 336/111 | 336/111 | 336/111 |

| nad5 | 1584/527 | 1584/527 | 1584/527 | 1584/527 | 1593/530 | 1584/527 | 1584/527 | 1584/527 | 1584/527 | 1584/527 | 1584/527 | 1584/527 | 1584/527 | 1584/527 | 1584/527 | 1584/527 | 1599/532 | 1584/527 | 1584/527 | 1584/527 | 1584/527 |

| nad6 | 435/144 | 435/144 | 435/144 | 435/144 | 435/144 | 435/144 | 435/144 | 435/144 | 435/144 | 435/144 | 435/144 | 435/144 | 435/144 | 435/144 | 438/145 | 435/144 | 435/144 | 435/144 | 435/144 | 435/144 | 435/144 |

| nad4L | 234/77 | 234/77 | 234/77 | 234/77 | 234/77 | 234/77 | 234/77 | 234/77 | 234/77 | 234/77 | 234/77 | 234/77 | 234/77 | 234/77 | 234/77 | 234/77 | 234/77 | 234/77 | 234/77 | 234/77 | 234/77 |

| rrnS | 704/– | 708/– | 698/– | 700/– | 699/– | 700/– | 701/– | 701/– | 699/– | 700/– | 699/– | 699/– | 697/– | 711/– | 702/– | 709/– | 708/– | 700/– | 703/– | 696/– | 701 |

| nad1 | 873/290 | 873/290 | 873/290 | 873/290 | 873/290 | 873/290 | 873/290 | 873/290 | 873/290 | 873/290 | 873/290 | 873/290 | 873/290 | 873/290 | 873/290 | 873/290 | 879/292 | 876/291 | 873/290 | 873/290 | 873/290 |

| atp6 | 600/199 | 600/199 | 600/199 | 600/199 | 600/199 | 600/199 | 600/199 | 600/199 | 600/199 | 600/199 | 600/199 | 600/199 | 600/199 | 600/199 | 600/199 | 600/199 | 600/199 | 603/200 | 600/199 | 600/199 | 600/199 |

| nad2 | 846/281 | 846/281 | 846/281 | 846/281 | 846/281 | 846/281 | 846/281 | 846/281 | 846/281 | 846/281 | 846/281 | 846/281 | 846/281 | 846/281 | 846/281 | 846/281 | 846/281 | 846/281 | 846/281 | 846/281 | 846/281 |

| cytb | 1113/370 | 1113/370 | 1113/370 | 1113/370 | 1113/370 | 1113/370 | 1110/369 | 1113/370 | 1113/370 | 1113/370 | 1113/370 | 1113/370 | 1113/370 | 1113/370 | 1113/370 | 1113/370 | 1113/370 | 1116/371 | 1113/370 | 1113/370 | 1113/370 |

| cox3 | 766/255 | 766/255 | 766/255 | 766/255 | 766/255 | 766/255 | 766/255 | 766/255 | 766/255 | 769/256 | 766/255 | 766/255 | 766/255 | 766/255 | 766/255 | 766/255 | 766/255 | 766/255 | 766/255 | 766/255 | 766/255 |

| nad4 | 1230/409 | 1230/409 | 1230/409 | 1230/409 | 1230/409 | 1230/409 | 1230/409 | 1230/409 | 1230/409 | 1230/409 | 1230/409 | 1230/409 | 1230/409 | 1230/409 | 1230/409 | 1227/408 | 1230/409 | 1230/409 | 1230/409 | 1230/409 | 1230/409 |

| Total | 11,967 | 11,975 | 11,962 | 11,968 | 11,971 | 11,963 | 11,968 | 11,967 | 11,959 | 11,953 | 11,958 | 11,964 | 11,957 | 11,980 | 11,978 | 11,980 | 11,979 | 11,960 | 11,969 | 11,963 | 11,953 |

Pet. skrjabini, Petrovinema skrjabini; Cya. Catinatum, Cyathostomum catinatum; Cya. pateratum, Cyathostomum pateratum; Cya. Tetracanthum, Cyathostomum tetracanthum; Cylicos. goldi, Cylicostephanus goldi; Cylicos. minutus, Cylicostephanus minutus; Cor. labiatus, Coronocyclus labiatus; Cor. labratus, Coronocyclus labratus; Cylicoc. auriculatus, Cylicocyclus auriculatus; Cylicoc. insignis, Cylicocyclus insignis; Cylicoc. elongatus, Cylicocyclus elongatus; Cylicoc. nassatus, Cylicocyclus nassatus; Cylicoc. radiatus, Cylicocyclus radiatus; Cylicoc. ashworthi, Cylicocyclus ashworthi; Cylicod. bicoronatus, Cylicodontophorus bicoronatus; Pot. imparidentatum, Poteriostomum imparidentatum; Str. equinus, Strongylus equinus; Str. vulgaris, Strongylus vulgaris; Tri. brevicauda, Triodontophorus brevicauda; Tri. nipponicus, Triodontophorus nipponicus; Tri. serratus, Triodontophorus serratus

Fig. 4.

Relative synonymous codon usage (RSCU, A) and COUNT (B) of Petrovinema skrjabini mitogenome

tRNA genes, rRNA genes, and non-coding regions

The P. skrjabini mitogenome contained 22 tRNA genes, ranging in length from 52 to 63 bp, these tRNAs appeared to fold into an atypical clover-leaf secondary structure. Two tRNAs, namely tRNA-Ser2 and tRNA-Ser1, lacked a dihydrouridine arm and had a d-loop structure. The other 20 tRNAs lacked the TΨC loop, which was replaced by the “TV-replacement loop”. The two rRNA genes, rrnL (974 bp) and rrnS (704 bp), were located between tRNA-His and nad3, and between tRNA-Glu and tRNA-Ser, respectively. The AT contents of rrnL and rrnS were 80.1% and 76.6%, respectively. Two NCRs were identified: the long NCR (326 bp) located between tRNA-Ala and tRNA-Pro, and the short NCR (87 bp) located between nad4 and cox1 (Table 2), with AT contents of 87.8% and 80.5%, respectively. The rrnL gene was located between tRNA-His and nad3, whereas rrnS was located between tRNA-Glu and tRNA-Ser.

Phylogenetic analyses

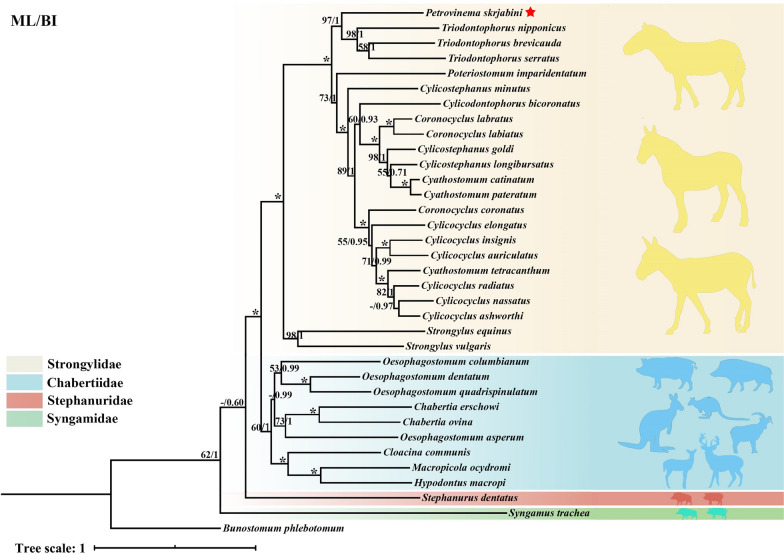

Prior to phylogenetic reconstruction, substitution saturation analysis of the 12 PCGs was performed (Fig. 5). The substitution saturation index (Iss) was significantly lower than the critical Iss value (P < 0.001), confirming minimal saturation and validating the suitability of these sequences for phylogenetic inference. Phylogenetic analyses were reconstructed using concatenated sequences of the 12 PCGs from P. skrjabini and 33 other Strongyloidea species representing 16 genera (data from GenBank). The maximum likelihood (ML) and Bayesian inference (BI) analyses produced identical tree topologies (Fig. 6). While most nodes were well-supported, some nodes in Oesophagostominae and Strongylidae displayed weak bootstrap support (< 50) in ML but were strongly supported in BI (posterior probability ≥ 0.97). The Cyathostominae subfamily formed a strongly supported monophyletic clade (bootstrap = 100; posterior probability = 1), including genera Cylicocyclus, Cyathostomum, Coronocyclus, Poteriostomum, Cylicostephanus, Cylicodontophorus, Petrovinema, and Triodontophorus (traditionally classified under Strongylinae). In contrast, Strongylinae was paraphyletic, with Strongylus vulgaris and S. equinus forming a basal clade, while Triodontophorus clustered within Cyathostominae. Petrovinema skrjabini clustered robustly with three species of the Triodontophorus genus (posterior probability = 1; bootstrap = 97), forming a monophyletic group that further clustered with six other genera within the Cyathostominae subfamily (Fig. 6).

Fig. 5.

The transitions (s) and transversions (v) for 12 protein-coding genes of Strongyloidea against GTR distance. Plots in blue and orange indicate transition and transversion, respectively. (A) Coding genes 1, 2 and 3; (B) Coding gene 1; (C) Coding gene 2; (D) Coding gene 3; (E) Coding genes 1 and 2

Fig. 6.

Phylogenetic relationships of Strongyloidea inferred from mitochondrial genomes. Topology obtained on the basis of concatenated amino acid sequences of 12 protein coding genes analyzed by maximum likelihood (ML) and Bayesian inference (BI) using Bunostomum phlebotomum as an outgroup. Statistical support values (bootstrap/posterior probability) of ML/BI analysis are shown above the nodes. Asterisks (*) indicate ML/BI = 100/1.0, other values are given above the nodes. Families are highlighted by individual colors. The species identified in the present study is denoted by the red star. Values below 50% are shown here as “–”

Discussion

Previous studies on the Strongyloidea superfamily have primarily relied on single-gene markers or morphological characteristics, which often lack the resolution required to resolve complex evolutionary relationships, particularly for the genus Petrovinema. In this study, we sequenced and analyzed the complete mitochondrial genome of P. skrjabini, revealing its gene content, arrangement, and codon usage. This work not only expands the available genomic resources for Strongyloidea nematodes but also offers new insights into their evolutionary relationships and phylogenetic placement.

The gene arrangement of P. skrjabini conformed to the GA3 [47] pattern, consistent with other strongylids such as T. brevicauda, Strongylus equinus, Cylicocyclus insigne, and Cylicodontophorus bicoronatus [23, 24, 48–52]. This structural conservation reflects evolutionary stability and strong selective pressures within the Strongyloidea superfamily. The absence of the ATP8 gene in P. skrjabini and other Strongyloidea species, is likely due to functional redundancy or gene loss during evolution. The notable AT bias in the P. skrjabini mitogenome (75.4%) was consistent with Strongyloidea mitogenomes [24, 52–54] (Fig. 2), with NCR AT content (86.5%) similar to those observed in nematodes and trematodes, such as Cylicocyclus radiatus, Cyathostomum catinatum, Coronocyclus labiatus, Echinostoma miyagawai, and Postharmostomum commutatum [24, 55, 56]. In addition, the size and location of NCRs in the P. skrjabini mitogenome resembled those in the subfamily of Cyathostominae nematodes (Table 3) but differed from those of the subfamily of Strongylinae nematodes [48–50]. Regarding nucleotide composition, the highest AT-skew value was found at the third codon position, and the lowest in the second codon position, consistent with observations in nematodes and trematodes, such as Cylicocyclus radiatus, Coronocyclus labiatus, Cylicodontophorus bicoronatus, and E. miyagawai [23, 24, 55]. These findings suggest that the nucleotide composition and skewness in the P. skrjabini mitogenome are consistent with evolutionary patterns observed in related species, indicating conserved mutational pressures and selection mechanisms across different nematode and trematode taxa.

The mitochondrial codon usage in P. skrjabini and related Strongylidae species follows the standard invertebrate genetic code, with UUA (Leu) and CGU (Arg) being the most common, consistent with 22 published Strongylidae mitogenomes [23, 24, 50, 55]. Minor interspecific differences in RSCU values were observed: CUC (Leu) has an RSCU of 0.01 in Cylicodontophorus bicoronatus but was absent (RSCU = 0) in P. skrjabini and Coronocyclus labiatus. Similarly, CGC (Arg) showed limited usage (RSCU = 0.13) in P. skrjabini but was absent (RSCU = 0) in Cylicocyclus radiatus and Cylicodontophorus bicoronatus [23, 24]. These RSCU differences highlight evolutionary divergence in codon preference, not alterations to the genetic code, aligning with the conserved framework reported for Strongylidae nematodes [23, 24, 50, 52]. The rRNA genes, rrnL and rrnS, in P. skrjabini are of similar length to those in other nematodes, such as T. brevicauda (975 bp and 703 bp), Po. imparidentatum, Chabertia erschowi (970 bp and 696 bp), and Chabertia ovina (962 bp and 696 bp) [24, 34, 48, 50, 57, 58]. There was no difference compared with other Strongylinae nematodes, such as Cylicocyclus radiates [57], in the position of rrnS. The rrnL gene was located between tRNA-His and nad3; whereas, rrnS was located between tRNA-Glu and tRNA-Ser.

This study revealed the phylogenetic relationships of the genus Petrovinema through mitogenome analysis of P. skrjabini. Contrary to the findings of Bu et al. (2016), based on P. poculatum ITS1/ITS2 sequence data [59], which suggested a close phylogenetic relationship between Petrovinema and Poteriostomum, our mitochondrial genomic data demonstrate that P. skrjabini forms a monophyletic clade with Triodontophorus (bootstrap/posterior probability = 97/1). This difference could potentially be due to differences in gene fragment selection and length used for phylogenetic tree construction, as longer mitochondrial genome segments provide better resolution for evolutionary trees. Owing to its relatively long length, the mitochondrial genome contains more informative data and more accurately represents the evolutionary relationships among parasitic nematodes. Similarly, the taxonomic discordance between the mitochondrial clade of Petrovinema and the nuclear gene clade of Poteriostomum underscores the necessity of integrating multi-genomic datasets in resolving phylogenies of morphologically convergent groups.

The mitochondrial phylogenetic position of the genus Triodontophorus (nested within the subfamily Cyathostominae), exhibits a clear inconsistency with its morphological classification under Strongylinae (Fig. 6). This incongruence corroborates the conclusions of Hung et al. and Gao et al. [27, 60]. Our results further validate that the traditional classification, dividing Strongylidae into the Strongylinae and Cyathostominae subfamilies [22] based solely on the size and shape of the buccal capsule is insufficient. On the basis of the existing molecular data, we propose transferring Triodontophorus to Cyathostominae while retaining Strongylinae as a monotypic subfamily containing the genus Strongylus. The phylogenetic analysis in this study was limited by the insufficient coverage of genomic data for extant genera in the Strongylinae and Cyathostominae subfamilies (9/19 genera lacking data). Future studies should prioritize filling the genomic data for key genera (such as Oesophagodontus and Skrjabinodentus) to enhance the reliability of the topological structure. In addition, the coordinated analysis of morphological trait quantification (such as buccal capsule depth) and molecular evolutionary rates remains unexplored. Subsequent studies can further dissect the mechanisms of species differentiation by integrating multi-omics data from geographical population samples. These expansion directions will systematically improve the classification framework of the Strongylidae family and provide new dimensions for the study of the adaptive evolution of parasitic nematodes.

Conclusions

In the present study, the complete mitogenome sequence of P. skrjabini was assembled, and comparative mitogenomes and phylogenetic analyses with other Strongyloidae species were carried out. Using next-generation sequencing technology, our analyses provided additional molecular evidence to clarify the systematic position of P. skrjabini, further improving the understanding of phylogenetic relationships within the Strongylidae family. Our study enriches the database of Strongylidae mitogenomes. The availability of the complete mitogenome of P. skrjabini also provides useful genetic markers for molecular epidemiology, population genetics, and systematics of Strongylidae nematodes infecting equids.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the staff of Kalamaili Nature Reserve (Aletai, Xinjiang Province) for their support in collecting samples used in this study and for valuable technical assistance, especially veterinarian Mr. Make Ente for his kind help and support.

Abbreviations

- ML

Maximum likelihood

- BI

Bayesian inference

- PCGs

Protein-coding genes

- RSCU

The relative synonymous codon usage

- GA

Gene arrangement

- Ks

Synonymous

- Ka

Non-synonymous

- GTR

General time-reversible

- I

Invariable sites

- G

Gamma distribution

- Iss

Index of substitution saturation

Author contributions

Huiping Jia, Liping Tang, Kai Li, Defu Hu, and Dong Zhang conceived of the study and participated in its design. Huiping Jia, Yajun Fu, Yu Xiong, and Changliang Shao coordinated the field activities and nematode collection. Huiping Jia and Liping Yan carried out the molecular analysis. Huiping Jia conducted the phylogenetic analyses and wrote the manuscript. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (2022YFC2601601).

Availability of data and materials

The mitochondrial DNA sequences of Petrovinema skrjabini obtained in the present study were deposited in the GenBank database under the BioSample: SAMN17267219; BioProject: PRJNA690898; Sequence Read Archive: SRS7997327; GenBank Accession number: OP784481.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Dong Zhang, Email: ernest8445@163.com.

Defu Hu, Email: hudf@bjfu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Clark A, Sallé G, Ballan V, Reigner F, Meynadier A, Cortet J, et al. Strongyle infection and gut microbiota: profiling of resistant and susceptible horses over a grazing season. Front Physiol. 2018;9:272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kuzmina TA, Tolliver SC, Lyons ET. Three recently recognized species of cyathostomes (Nematoda: Strongylidae) in equids in Kentucky. Parasitol Res. 2011;108:1179–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.SSaeed MA, Beveridge I, Abbas G, Beasley A, Bauquier J, Wilkes E, et al. Systematic review of gastrointestinal nematodes of horses from Australia. Parasit Vectors. 2019;12:188.10.1186/s13071-019-3445-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Corning S. Equine cyathostomins: a review of biology, clinical significance and therapy. Parasit Vectors. 2009;2:S1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krecek RC, Guthrie AJ. Alternative approaches to control of cyathostomes: an African perspective. Vet Parasitol. 1999;85:151–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morariu S, Mederle N, Badea C, Dărăbuş G, Ferrari N, Genchi C. The prevalence, abundance and distribution of cyathostomins (small stongyles) in horses from Western Romania. Vet Parasitol. 2016;223:205–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Painer J, Kaczensky P, Ganbaatar O, Huber K, Walzer C. Comparative parasitological examination on sympatric equids in the great gobi “B” strictly protected area, Mongolia. Eur J Wildl Res. 2011;57:225–32. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baptista CJ, Sós E, Madeira de Carvalho L. Gastrointestinal parasitism in Przewalski horses (Equus ferus przewalskii). Acta Parasitol. 2021;66:1095–101. 10.1007/s11686-021-00391-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kuzmina T, Zvegintsova N, Zharkikh T. Strongylid community structure of the przewalski’s horses (Equus ferus przewalskii) from the biosphere reserve “askania-Nova”, Ukraine. Vestn Zool. 2009;43:e5. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Slivinska K, Klich D, Yasynetska N, Zygowska M. The effects of seasonality and group size on fecal egg counts in wild Przewalski’s horses (Equus ferus przewalskii, Poljakov, 1881) in the Chernobyl exclusion zone, Ukraine during 2014–2018. Helminthologia (Poland). 2020;57:314–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferrari N, Cattadori IM, Rizzoli A, Hudson PJ. Heligmosomoides polygyrus reduces infestation of Ixodes ricinus in free-living yellow-necked mice, Apodemusflavicollis. Parasitology. 2009;136:305–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lass S, Hudson PJ, Thakar J, Saric J, Harvill E, Albert R, et al. Generating super-shedders: co-infection increases bacterial load and egg production of a gastrointestinal helminth. J R Soc Interf. 2013;10:20120588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lello J, Boag B, Fenton A, Stevensonlan R, Hudson PJ. Competition and mutualism among the gut helminths of a mammalian host. Nature. 2004;428:837–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Randall J, Cable J, Guschina IA, Harwood JL, Lello J. Endemic infection reduces transmission potential of an epidemic parasite during co-infection. Proc Roy Soc B Biol Sci. 2013;280:20131500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tombak KJ, Hansen CB, Kinsella JM, Pansu J, Pringle RM, Rubenstein DI. The gastrointestinal nematodes of plains and Grevy’s zebras: phylogenetic relationships and host specificity. Int J Parasitol Parasites Wildl. 2021;16:228–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bredtmann CM, Krücken J, Murugaiyan J, Kuzmina T, von Samson-Himmelstjerna G. Nematode species identification—current status, challenges and future perspectives for cyathostomins. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2017;7:283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blouin MS. Molecular prospecting for cryptic species of nematodes: mitochondrial DNA versus internal transcribed spacer. Int J Parasitol. 2002;32:527–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gasser RB, Newton SE. Genomic and genetic research on bursate nematodes: significance, implications and prospects. Int J Parasitol. 2000;30:509–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hung GC, Chilton NB, Beveridge I, Gasser RB. Secondary structure model for the ITS-2 precursor rRNA of strongyloid nematodes of equids: implications for phylogenetic inference. Int J Parasitol. 1999;29:1949–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nisa RU, Tantray AY, Shah AA. Shift from morphological to recent advanced molecular proaches for the identification of nematodes. Genomics. 2022;2:114.10.1016/j.ygeno.2022.110295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blaxter ML, De Ley P, Garey JR, Llu LX, Scheldeman P, Vierstraete A, et al. A molecular evolutionary framework for the phylum Nematoda. Nature. 1998;392:71–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lichtenfels JR, Kharchenko VA, Dvojnos GM. Illustrated identification keys to strongylid parasites (Strongylidae: Nematoda) of horses, zebras and asses (Equidae). Vet Parasitol. 2008;156:4–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gao Y, Wang XX, Ma XX, Zhang ZH, Lan Z, Qiu YY, et al. Characterization of the complete mitochondrial genomes of Coronocyclus labiatus and Cylicodontophorus bicoronatus: comparison with Strongylidae species and phylogenetic implication. Vet Parasitol. 2021;290:109359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hu L, Zhang M, Sun Y, Bu Y. Characterization and phylogenetic analysis of the first complete mitochondrial genome of Cylicocyclus radiatus. Vet Parasitol. 2020;281:109097. 10.1016/j.vetpar.2020.109097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McDonnell A, Love S, Tait A, Lichtenfels JR, Matthews JB. Phylogenetic analysis of partial mitochondrial cytochrome oxidase c subunit I and large ribosomal RNA sequences and nuclear internal transcribed spacer I sequences from species of Cyathostominae and Strongylinae (Nematoda, Order Strongylida), parasites of. Parasitology. 2000;121:649–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang L, Hu M, Chilton NB, Huby-Chilton F, Beveridge I, Gasser RB. Nucleotide alterations in the D3 domain of the large subunit of ribosomal DNA among 21 species of equine strongyle. Mol Cell Probes. 2007;21:111–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gao Y, Zhang Y, Yang X, Qiu JH, Duan H, Xu WW, et al. Mitochondrial DNA evidence supports the hypothesis that Triodontophorus species belong to cyathostominae. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peregrine AS, Mcewen B, Bienzle D, Koch TG, Weese JS. Larval cyathostominosis in horses in Ontario: an emerging disease? Can Vet J. 2006;47:80. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang LP, Kong FY. Parasitic nematodes from Equus spp.Beijing: China Agriculture Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2114–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bernt M, Donath A, Jühling F, Externbrink F, Florentz C, Fritzsch G, et al. MITOS: improved de novo metazoan mitochondrial genome annotation. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2013;69:313–9. 10.1016/j.ympev.2012.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tamura K, Stecher G, Peterson D, Filipski A, Kumar S. MEGA6: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 6. Mol Biol Evol. 2013;30:2725–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Perna NT, Kocher TD. Patterns of nucleotide composition at fourfold degenerate sites of animal mitochondrial genomes. J Mol Evol. 1995;41:353–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA5: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol Biol Evol. 2011;28:2731–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rozas J, Ferrer-Mata A, Sánchez-DelBarrio JC, Guirao-Rico S, Librado P, Ramos-Onsins SE, et al. DnaSP 6: DNA sequence polymorphism analysis of large data sets. Mol Biol Evol. 2017;34:3299–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gómez-Rubio V. ggplot2 - elegant graphics for data analysis. J Stat Softw. 2017;77:1–3. 10.18637/jss.v077.b02. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Librado P, Rozas J. DnaSP v5: A software for comprehensive analysis of DNA polymorphism data. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1451–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu GH, Zhao L, Song HQ, Zhao GH, Cai JZ, Zhao Q, et al. Chabertia erschowi (Nematoda) is a distinct species based on nuclear ribosomal DNA sequences and mitochondrial DNA sequences. Parasit Vectors. 2014;7:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xia X, Xie Z, Salemi M, Chen L, Wang Y. An index of substitution saturation and its application. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2003;26:1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gao JF, Zhao Q, Liu GH, Zhang Y, Zhang Y, Wang WT, et al. Comparative analyses of the complete mitochondrial genomes of the two ruminant hookworms Bunostomum trigonocephalum and Bunostomum phlebotomum. Gene. 2014;541:92–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stamatakis A. RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:1312–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ronquist F, Teslenko M, Van Der Mark P, Ayres DL, Darling A, Höhna S, et al. Mrbayes 3.2: efficient Bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Syst Biol. 2012;61:539–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhao H, Zhu J, Zong TK, Liu XL, Ren LY, Lin Q, et al. Two new species in the family Cunninghamellaceae from China. Mycobiology. 2021;49:142–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhao H, Nie Y, Zong TK, Wang YJ, Wang M, Dai YC, et al. Species diversity and ecological habitat of Absidia (Cunninghamellaceae, Mucorales) with emphasis on five new species from forest and grassland soil in China. Journal of Fungi. 2022;8:471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Darriba D, Posada D, Kozlov AM, Stamatakis A, Morel B, Flouri T. ModelTest-NG: a new and scalable tool for the selection of DNA and protein evolutionary models. Mol Biol Evol. 2020;37:291–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Letunic I, Bork P. Interactive Tree of Life (iTOL) v4: recent updates and new developments. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:W256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu GH, Shao R, Li JY, Zhou DH, Li H, Zhu XQ. The complete mitochondrial genomes of three parasitic nematodes of birds: a unique gene order and insights into nematode phylogeny. BMC Genomics. 2013;14:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Duan H, Gao JF, Hou MR, Zhang Y, Liu ZX, Gao DZ, et al. Complete mitochondrial genome of an equine intestinal parasite, Triodontophorus brevicauda (Chromadorea: Strongylidae): the first characterization within the genus. Parasitol Int. 2015;64:429–34. 10.1016/j.parint.2015.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Xu WW, Qiu JH, Liu GH, Zhang Y, Liu ZX, Duan H, et al. The complete mitochondrial genome of Strongylus equinus (Chromadorea: Strongylidae): comparison with other closely related species and phylogenetic analyses. Exp Parasitol. 2015;159:94–9. 10.1016/j.exppara.2015.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gao JF, Liu GH, Duan H, Gao Y, Zhang Y, Chang QC, et al. Complete mitochondrial genomes of Triodontophorus serratus and Triodontophorus nipponicus, and their comparison with Triodontophorus brevicauda. Exp Parasitol. 2017;181:88–93. 10.1016/j.exppara.2017.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Qiu YY, Zeng MH, Diao PW, Wang XX, Li Q, Li Y, et al. Comparative analyses of the complete mitochondrial genomes of Cyathostomum pateratum and Cyathostomum catinatum provide new molecular data for the evolution of Cyathostominae nematodes. J Helminthol. 2019;93:643–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gao Y, Qiu JH, Zhang BB, Su X, Fu X, Yue DM, et al. Complete mitochondrial genome of parasitic nematode Cylicocyclus nassatus and comparative analyses with Cylicocyclus insigne. Exp Parasitol. 2017;172:18–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kim T, Kim J, Cho S, Min GS, Park C, Carreno RA, et al. Phylogeny of Rhigonematomorpha based on the complete mitochondrial genome of Rhigonema thysanophora (Nematoda: Chromadorea). Zool Scr. 2014;43:289–303. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Palomares-Rius JE, Cantalapiedra-Navarrete C, Archidona-Yuste A, Blok VC, Castillo P. Mitochondrial genome diversity in dagger and needle nematodes (Nematoda: Longidoridae). Sci Rep. 2017;7:41813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Li Q, Gao Y, Wang XX, Li Y, Gao JF, Wang CR. The complete mitochondrial genome of Cylicocylus ashworthi (Rhabditida: Cyathostominae). Mitochondrial DNA B Resour. 2019;4:1225–6. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fu YT, Jin YC, Liu GH. The complete mitochondrial genome of the Caecal fluke of poultry, Postharmostomum commutatum, as the first representative from the superfamily Brachylaimoidea. Front Genet. 2019;10:1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Deng YP, Zhang XL, Li LY, Yang T, Liu GH, Fu YT. Characterization of the complete mitochondrial genome of the swine kidney worm Stephanurus dentatus (Nematoda: Syngamidae) and phylogenetic implications. Vet Parasitol. 2021;295:109475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhao L, Liu GH, Zhao GH, Cai JZ, Zhu XQ, Qian AD. Genetic differences between Chabertia ovina and C. erschowi revealed by sequence analysis of four mitochondrial genes. Mitochondrial DNA. 2015;26:167–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bu YZ. Studies on Strongylid Nematodes in Henan Province. Zhengzhou: Henan Science and Technology Press; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hung GC, Chilton NB, Beveridge I, Gasser RB. A molecular systematic framework for equine strongyles based on ribosomal DNA sequence data. Int J Parasitol. 2000;30:95–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The mitochondrial DNA sequences of Petrovinema skrjabini obtained in the present study were deposited in the GenBank database under the BioSample: SAMN17267219; BioProject: PRJNA690898; Sequence Read Archive: SRS7997327; GenBank Accession number: OP784481.