Abstract

Background

Superficial fungal infections (SFIs) are highly prevalent globally, affecting approximately 20–25% of the population. Their diverse and often non-specific clinical manifestations necessitate accurate and timely laboratory diagnosis. Traditional methods such as potassium hydroxide (KOH) microscopy and fluorescence staining, although widely used, are limited by operator dependency, variability in sensitivity, and time-consuming procedures. To improve diagnostic accuracy and efficiency, we evaluated the performance of a novel Artificial Intelligence (AI) -powered Fluorescence Microscopic Image Analyzer (FMIA) in the early detection of SFIs.

Results

Among 300 patients with suspected SFIs, 241 were confirmed using a comprehensive clinical and mycological reference standard. FMIA achieved the highest diagnostic sensitivity (96.27%), outperforming both fluorescence staining (92.95%) and KOH microscopy (75.52%). FMIA also demonstrated high specificity (96.61%) and an area under the ROC curve of 0.96. In spore-dominant infections such as Malassezia folliculitis, genital candidiasis, tinea capitis, and seborrheic dermatitis, where KOH microscopy showed lower detection rates ranging from 29 to 59%, FMIA achieved significantly higher sensitivities between 83% and 100%. Across various SFI subtypes, FMIA consistently exhibited excellent diagnostic performance, achieving 100% detection for tinea pedis, tinea manuum, tinea faciei, and pityriasis versicolor. The system provided results within three to five minutes at a low per-test cost, while automated focusing and frame validation effectively minimized false positives caused by artifacts.

Conclusions

The FMIA system offers a highly accurate, rapid, and cost-effective tool for diagnosing SFIs. By addressing the limitations of traditional microscopy and current AI-based image analysis methods, FMIA improves diagnostic precision and efficiency. Its fully automated workflow delivers significant clinical value for routine application in both high-throughput diagnostic laboratories and resource-limited healthcare settings.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12879-025-11296-5.

Keywords: Superficial fungal infections, Automatic fluorescence microscopy, Artificial intelligence (AI), Diagnostic tool, Image analysis, Clinical mycology

Introduction

Superficial fungal infections (SFIs) refer to infections caused by pathogenic fungi that colonize the outermost layers of the skin, nails, and hair [1]. These infections exhibit diverse clinical manifestations depending on the anatomical sites and causative pathogens, often presenting as chronic or recurrent conditions [2]. Globally, SFIs represent a significant public health concern, with an estimated prevalence of 20–25% [3]. Dermatophyte infections are the most common form, whereas yeasts and non-dermatophyte molds constitute other notable etiological agents [4]. In regions with a high burden of SFIs, the incidence of dermatophytosis has been reported to reach as high as 70 %−100% [4, 5]. In many cases, the clinical manifestations of SFIs are nonspecific or subtle, necessitating mycological examination for definitive diagnosis [6].

Despite the widespread use of traditional diagnostic methods, identifying fungal infections remains a significant challenge, often contributing to considerable variability in patient prognoses [7]. Among conventional approaches, potassium hydroxide (KOH) microscopy and fluorescence staining remain pivotal for direct visualization of fungal elements during early diagnosis of SFIs [8, 9]. While KOH examination is low-cost and widely accessible, its diagnostic performance is limited by variable sensitivity and reliance on the operator’s experience [10]. Fluorescence staining significantly improves sensitivity and visualization clarity by enhancing fungal structures (9), yet it still requires considerable manual effort and technical expertise. Kaiti et al. reported that prolonged microscopy work is associated with asthenopic symptoms and measurable impairment in near binocular vision, underscoring the physical strain imposed by conventional diagnostic modalities [11].

To overcome these traditional limitations, there has been an increasing effort to apply digital imaging and computer vision technologies to automate the microscopic identification of fungi. For example, Koo and colleagues developed a deep learning model for the automatic detection of hyphal structures, offering advantages in terms of speed, convenience, consistency, and automation [10]. Mader et al. employed multiple image processing steps to preprocess, segment, and parameterize images obtained using an automated fluorescence imaging model [12]. Despite these advances, clinical validation of Artificial Intelligence (AI)-based tools in real-world mycological diagnostics remains limited.

The fluorescence microscopic image analyzer (FMIA) is a newly developed diagnostic instrument that integrates fluorescence staining, automatic focusing of the microscope with AI-powered image acquisition and interpretation. Designed to automatically detect fungal hyphae and spores in clinical specimens, FMIA enhances diagnostic efficiency by streamlining workflows, minimizing operator fatigue, and improving consistency and throughput. The aim of this prospective study was to evaluate the applicability of FMIA in the early diagnosis of SFIs by comparing its performance with conventional KOH examination and fluorescent staining microscopy.

Materials and methods

Patients and clinical specimens

The sample size of 300 patients was determined based on a preliminary power analysis using PASS 15.0 software (NCSS, LLC, USA). Assuming a two-sided alpha level of 0.05, a statistical power of 90%, and an expected difference in sensitivity of at least 10% between FMIA and conventional methods, a minimum of 273 participants was required to detect a significant difference using McNemar’s test for paired proportions. To account for potential dropouts and missing data, the final sample size was set at 300.

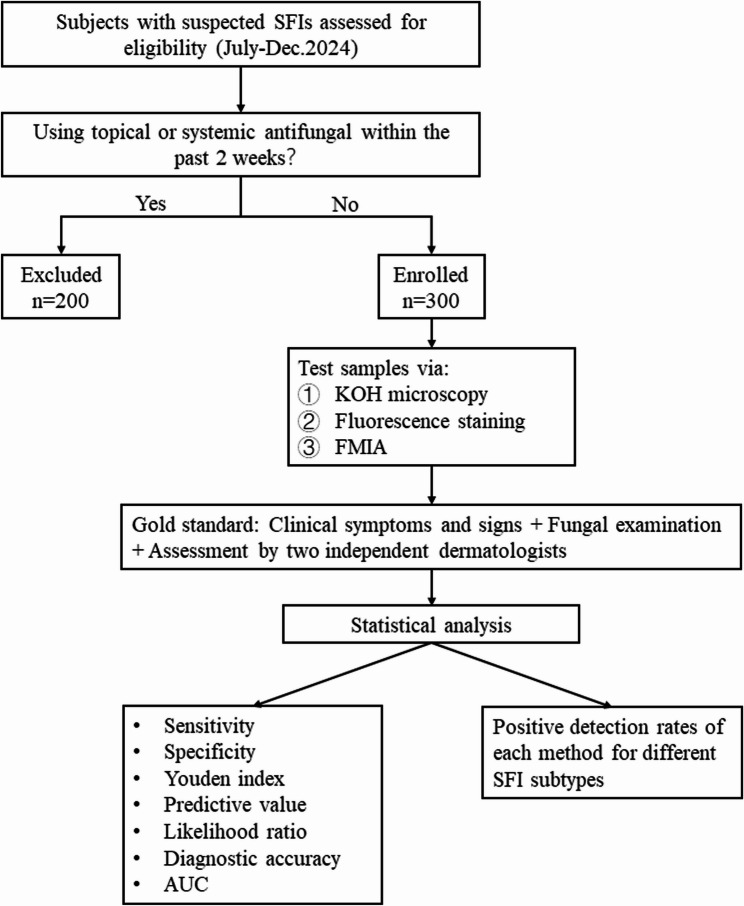

A total of 300 patients with suspected superficial fungal infections were enrolled in the study between July and December 2024, with no restrictions on age or gender. Patients who had used topical or systemic antifungal medications within the past two weeks were excluded from sampling. Skin lesion samples were obtained as close as possible to the edges of the affected areas. The samples were collected and analyzed using the automatic FMIA (Model FA500, Chongqing Tianhai Medical Equipment Co., Ltd., Chongqing, China), fluorescence staining, and KOH microscopy, with all examination results systematically recorded (Fig. 1). This study was conducted at the mycology department of Shanghai Skin Disease Hospital, China, and was approved by the hospital’s Ethics Committee in accordance with the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to their inclusion. Detailed demographic and clinical information, including age, sex, affected sites, clinical diagnosis, presenting symptoms, and medical history, was documented.

Fig. 1.

The flow diagram of study enrollment SFI, superficial fungal infection; FMIA, fluorescence microscopic image analyzer; KOH, potassium hydroxide; AUC, area under the curve

KOH examination

Depending on the sample type, different concentrations of KOH were used for specimen preparation. A 20% KOH solution was applied to nail, toenail, and hair samples, while a 10% KOH solution was used for all other specimens, with a standardized volume of one drop per sample. The preparation was either left to stand for a short period or was gently heated by briefly passing it through an alcohol lamp flame 2–3 times, to facilitate sample dissolution in the KOH solution. After cooling, the operator first examined the sample under a low-power microscope (10 × 10) to detect the presence of hyphae and spores. Subsequently, high-power microscopy (40 × 10) was used to assess the morphology, characteristics, location, size, and arrangement of the fungal elements, and the findings were documented for diagnostic evaluation.

Fluorescence staining

The sample was placed on a clean glass slide, and one drop of fluorescence dye (Chongqing Tianhai Medical Equipment Co., Ltd., Chongqing, China) was added to fully cover the sample. A coverslip was then placed on top, and the slide was left undisturbed for 1 min. Finally, the slide was observed under a fluorescence microscope (OLYMPUS BX53, Tokyo, Japan). The fluorescently labeled chitinase specifically binds to the chitin in the fungal cell wall, emitting bright blue-green fluorescence [13–15]. Based on this, the operator can determine the presence or absence of fungal elements.

FMIA examination

After the fluorescence staining preparation of the specimen, it was sequentially placed into the slide holder of the FMIA. The sample was automatically conveyed to the microscope system, where it underwent automatic microscopy, focusing, and scanning processes. The software system then automatically analyzes the scanned images, performing in-depth identification of fungal elements (hyphae or spores) under the microscope. The diagnostic results were automatically transmitted to the connected computer system.

To reduce diagnostic bias, each method (KOH, fluorescence staining, and FMIA) was conducted by a separate, experienced examiner blinded to clinical information and other test results.

Gold standard and statistical analysis

A composite gold standard was established based on clinical symptoms, signs, and fungal examination results, along with the opinions of two senior experts, as supported by previous diagnostic accuracy studies on fungal infections [16–18]. Each expert was blinded to the other’s assessments and to the results of FMIA, KOH microscopy, and fluorescence staining. FMIA was excluded from the reference standard to avoid incorporation bias.

Using the gold standard, we compared the diagnostic efficacy of KOH, fluorescence staining, and FMIA by evaluating sensitivity, specificity, Youden index, predictive value, likelihood ratio, diagnostic odds ratio, diagnostic accuracy, and area under the curve (AUC). Additionally, we assessed the positive detection rates of these methods for various SFIs.

Results

The combined gold standard diagnostic results indicated that 241 out of 300 subjects were diagnosed with SFIs. The mean age of these 241 subjects was 49 ± 19.38 years (ranging from 2 to 87 years). The male-to-female ratio of infections was 2.35: 1. The most common clinical infection type was tinea cruris, accounting for 21.2%, followed by tinea corporis (15.4%), tinea pedis (13.7%), and onychomycosis (12.9%). Seborrheic dermatitis, Malassezia folliculitis, pityriasis versicolor, and tinea manuum were observed in 9.5%, 7.1%, 5.8%, and 5.0% of the cases, respectively. Tinea faciei, genital candidiasis, and tinea capitis were the least common, each accounting for less than 5% of the cases (4.1%, 2.9%, and 2.5%, respectively).

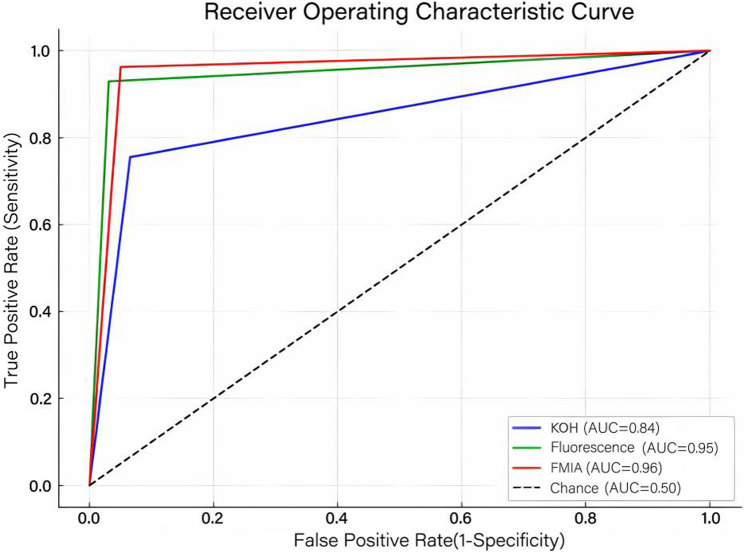

Among these 241 confirmed cases, FMIA achieved the highest sensitivity of 96.27%, followed by fluorescence staining (92.95%) and KOH microscopy (75.52%). Regarding specificity, fluorescence staining achieved the highest value at 96.61%, followed by FMIA at 94.92% and KOH examination at 93.22%. Furthermore, fluorescence staining and FMIA yielded comparable results in terms of the Youden index, likelihood ratio, predictive value, diagnostic odds ratio, and diagnostic accuracy, both significantly outperforming the KOH smear. These results are summarized in Table 1. Similarly, the area under the curve (AUC) values for fluorescence staining (0.95) and FMIA (0.96) were larger than that of KOH microscopy (0.84), as illustrated in Fig. 2.

Table 1.

Test characteristics for diagnosis of superficial fungal infections

| Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Youden index | PLR | NLR | DOR | PPV (%) | NPV (%) | Diagnostic accuracy (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Point value | 95%CI | Point value | 95%CI | ||||||||

| KOH | 75.52 | 69.72–80.52 | 93.22 | 83.82–97.33 | 0.69 | 11.14 | 0.26 | 42.42 | 97.87 | 48.25 | 79.00 |

| Fluorescence | 92.95 | 88.99–95.55 | 96.61 | 88.46–99.07 | 0.90 | 27.42 | 0.07 | 375.53 | 99.12 | 77.03 | 93.67 |

| FMIA | 96.27 | 93.06–98.02 | 94.92 | 86.08–98.26 | 0.91 | 18.93 | 0.04 | 481.19 | 98.73 | 86.15 | 96.00 |

KOH Potassium hydroxide, FMIA Fluorescence microscopic image analyzer, PLR Positive likelihood ratio, NLR Negative likelihood ratio, DOR Diagnostic odds ratio, PPV Positive predictive value, NPV Negative predictive value, CI Confidence interval

Fig. 2.

The receiver operating characteristic curve of KOH smear, fluorescence staining and FMIA test FMIA, fluorescence microscopic image analyzer; KOH, potassium hydroxide; AUC, area under the curve

As shown in Fig. 3, among the three examination methods, FMIA demonstrates the highest detection accuracy, achieving 100% sensitivity for several infections, including tinea faciei, malassezia folliculitis, pityriasis versicolor and genital candidiasis. Fluorescence staining also shows high detection rates but exhibits some variability, with lower performance observed in tinea capitis (83%), genital candidiasis (86%) and seborrheic dermatitis (87%). In contrast, KOH consistently shows the lowest detection rates across all tested fungal infections, particularly for genital candidiasis (29%) and seborrheic dermatitis (35%), indicating its relatively lower sensitivity. These findings underscore the superior performance of FMIA in the early detection of SFIs.

Fig. 3.

Comparison of positive detection rates of KOH microscopy, fluorescent staining, and FMIA in diagnosing superficial fungal diseases FMIA, fluorescence microscopic image analyzer; KOH, potassium hydroxide

Comparative analysis of six fungal diagnostic methods as shown in Table 2 demonstrated that FMIA provided the fastest diagnostic turnaround time of 3 to 5 min, outperforming PCR which required 2 to 14 days, fungal culture which took 2 to 4 weeks, and conventional microscopy including KOH smears requiring approximately 20 min and fluorescence staining requiring 8 to 10 min. FMIA achieved this speed at a cost of 48 Yuan per test, which is significantly lower than the cost of PCR (ranging from 220 to 1000 Yuan) and MALDI-TOF MS (120 Yuan), while also requiring minimal labor due to its automated workflow. Although FMIA demands high initial device investment, its low recurring material costs contrast with the high infrastructure and expertise burdens of molecular methods. Figure 4 displays fluorescence staining characteristics of various dermatological conditions captured by the FMIA.

Table 2.

Comparison of six fungal diagnostic methods in terms of time to final results, costs per examination (according to the China medical fee schedule), resource acquisition, personnel and laboratory effort, and differentiation capability

| Diagnostic method | Time frame until diagnosis | Costs per examination (Yuan) | Material and device acquisition | Labor consumption | Differentiation of species |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KOH smear | 20 min | 10 | Low | Low | No |

| Fluorescence staining | 8–10 min | 48 | Low | Low | No |

| FMIA | 3–5 min | 48 | Low Material + High device | Lowest | No |

| Fungal culture | 2–4 weeks | 60 | Low | depends | Possible |

| MALDI-TOF MS | 3–7 days | 120 | High | High | Possible |

| PCR | 2–14 days | 220–1000 | High | High | Possible |

KOH Potassium hydroxide. FMIA Fluorescence microscopic image analyzer. MALDI-TOF MS Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry. PCR Polymerase Chain Reaction

Fig. 4.

Fluorescence staining morphology of different dermatological infection samples captured by the FMIA. A Groin scales from a patient with tinea cruris, showing abundant septate hyphae under fluorescence staining. B Toenail scales from a patient with onychomycosis, revealing numerous septate hyphae and a few spores under fluorescence staining. C Foot scales from a patient with tinea pedis, displaying long septate hyphae under fluorescence staining. D Back scales from a patient with pityriasis versicolor, showing short, arc-shaped hyphae under fluorescence staining. E Sebaceous glands from a patient with malassezia folliculitis on the chest, revealing abundant budding spores under fluorescence staining. F Scalp scales from a patient with seborrheic dermatitis, showing numerous spores under fluorescence staining. G Sebaceous glands from a patient with folliculitis, showing Demodex mites under fluorescence staining. H Hand scales from a patient with scabies, showing Sarcoptes scabiei mites under fluorescence microscopy FMIA, fluorescence microscopic image analyzer

Discussion

The integration of AI into diagnostic workflows has revolutionized the field of medical mycology, particularly in addressing the limitations of conventional methods for diagnosing SFIs. Our study demonstrated that FMIA significantly outperforms both standalone fluorescence staining and KOH microscopy in terms of sensitivity (96.27% vs. 92.95% and 75.52%, respectively), while maintaining comparably high specificity (94.92% vs. 96.61% and 93.22%). These findings align well with existing literature. For instance, Hu et al. reported in a study on oral candidiasis that fluorescence staining exhibited superior sensitivity (85.48%) compared to KOH microscopy (65.42%), with specificities of 91.94% and 72.58%, respectively [16]. Similarly, Bao et al. found that in onychomycosis diagnostics, fluorescence staining achieved a sensitivity of 97% versus 85% with KOH, although specificity was slightly higher in the latter (100% vs. 89%) [19]. Further supporting the clinical potential of AI-assisted image analysis, Koo et al. applied regional convolutional neural networks to the detection of SFIs, achieving sensitivities of 95.2% and 99% under 100x and 40x magnification models, respectively, with corresponding specificities of 100% and 86.6% [10]. Another study demonstrated that machine learning systems used for stained slide interpretation achieved an accuracy of up to 92.5%, surpassing manual evaluation in both consistency and speed [20]. Collectively, these data underscore a paradigm shift toward AI-augmented diagnostic platforms that offer improved sensitivity and specificity, particularly in the early identification of SFIs.

The limitations of conventional methods are particularly evident in infections dominated by fungal spores. In our cohort, KOH microscopy demonstrated suboptimal detection rates for Malassezia folliculitis (59%), tinea capitis (50%), genital candidiasis (29%), and seborrheic dermatitis (35%). These findings are consistent with previous reports, which have documented KOH smear sensitivities of 60.6% for Malassezia folliculitis [21], 38% for vulvovaginal candidiasis [22], and 24.4% for seborrheic dermatitis [23]. This may be attributed to the small size of fungal spores and the inherent lack of color contrast in KOH preparations, which complicates differentiation of fungal elements from artifacts such as lipid droplets, keratin debris, and air bubbles. FMIA overcomes these limitations, achieving detection rates of 100% for Malassezia folliculitis and genital candidiasis, and 83% for tinea capitis and seborrheic dermatitis. Additionally, FMIA demonstrated outstanding diagnostic performance across a wide range of SFI subtypes, including tinea pedis (100%), pityriasis versicolor (100%), tinea manuum (100%), tinea faciei (100%), tinea corporis (97%), and onychomycosis (94%).

However, compared to other SFIs, the lower sensitivity observed for seborrheic dermatitis with fluorescence staining (87%) and FMIA (83%) warrants further attention. In seborrheic dermatitis lesions, the yeast form predominates, while the mycelial form is generally absent [23]. In contrast, most other spore-dominant SFIs exhibit some degree of hyphal development, which appears to be more readily detectable. This challenge is further compounded by low fungal load, uneven spore distribution, and obstruction from sebum and keratin debris. The slightly higher sensitivity of fluorescence staining likely reflects the advantage of real-time interpretation by experienced microscopists, who are better equipped to identify subtle fungal elements within complex backgrounds. In contrast, FMIA may misclassify sparse or clustered spores due to limited training data or confusion with morphologically similar artifacts, making its algorithm less effective at detecting weak or atypical signals (Fig. 5). These findings highlight the need to optimize FMIA algorithms by incorporating more seborrheic dermatitis cases into the training dataset to enhance fungal-artifact differentiation.

Fig. 5.

Representative fluorescence microscopy images of seborrheic dermatitis samples with undetected fungal spores by FMIA Fluorescence microscopy images of clinical samples from seborrheic dermatitis cases in which the fluorescence microscopic image analyzer (FMIA) failed to detect fungal elements. Red arrows indicate fungal spores that were not recognized by the automated system. Panels (a–d) show examples of spores with low contrast or isolated distribution, which may contribute to false-negative results. Insets in the top-right corners display magnified views of the indicated regions

Despite these subtype-specific challenges, FMIA maintains robust overall performance, which can be attributed to its intelligent image acquisition and interpretation protocol. The system is programmed to terminate scanning only after detecting three consecutive positive frames, thereby enhancing diagnostic reliability. For negative samples, the analyzer captures up to 36 images devoid of fungal elements before confirming a negative result, with this parameter adjustable based on clinical requirements. In cases of diagnostic ambiguity, clinicians can review archived high-resolution images to verify whether highlighted features correspond to genuine fungal morphology or to potential false-positive artifacts. False-positive signals are primarily attributed to non-biological structures such as cellulose fibers from clothing, circular or irregular light reflections from air inclusions, and miscellaneous debris like plastic particles or dirt [12]. Furthermore, out-of-focus elements caused by specimen thickness may introduce blur, complicating accurate identification. FMIA addresses this limitation through an automated focusing mechanism, ensuring consistent sharpness across all captured frames.

Although PCR and MALDI-TOF MS enable species-level identification, their implementation in routine clinical settings remains limited. PCR is hindered by high operational costs and technically demanding workflows [24–26], while MALDI-TOF MS requires expensive equipment, and its diagnostic accuracy is constrained by the incompleteness of existing reference databases [24, 27, 28], thereby reducing their accessibility in primary care and resource-limited environments. Both techniques require fungal isolation and culture, leading to diagnostic delays of several days to weeks. When a fungal skin infection caused by dermatophytes is suspected, the majority of dermatologists (89%) prefer to confirm the diagnosis through direct microscopic examination of skin specimens [20]. Previous studies have reported an average diagnostic time of approximately 20 min for KOH smear microscopy [26, 29] and around 10 min for fluorescence staining [30]. In contrast, FMIA achieves diagnostic readouts within 3 to 6 min, representing a substantial reduction in turnaround time. This rapid performance is particularly valuable in managing fungal infections, where delayed diagnosis can worsen morbidity and increase the risk of transmission [31, 32]. Notably, in cases where FMIA yields false-negative results due to inadequate specimen collection or early-stage infections with low fungal burden, or when accurate etiological confirmation is required to guide treatment decisions, particularly in atypical, recurrent, or treatment-resistant cases, complementary diagnostic tools such as PCR or MALDI-TOF MS remain essential.

Finally, this single-center study was conducted in a specialized dermatology hospital, which may limit the generalizability of the results. Further multi-center studies are needed to validate the performance of FMIA in broader clinical settings.

In conclusion, our findings establish FMIA as a transformative diagnostic tool for the early detection of SFIs, offering the dual benefits of AI-assisted precision and operational efficiency. By addressing the pitfalls of traditional methods, it holds significant potential to improve patient outcomes and streamline clinical workflows, thereby supporting its broader implementation across both tertiary and primary care settings.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

None.

Clinical trial number

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- SFI

Superficial Fungal Infection

- FMIA

Fluorescence Microscopic Image Analyzer

- AI

Artificial Intelligence

- KOH

Potassium hydroxide

- TPR

True Positive Rate

- FPR

False Positive Rate

- AUC

Area Under the Curve

- PLR

Positive Likelihood Ratio

- NLR

Negative Likelihood Ratio

- PPV

Positive Predictive Value

- NPV

Negative Predictive Value

- CI

Confidence Interval

- MALDI-TOF MS

Matrix-assisted Laser Desorption Ionization Time-of-flight Mass Spectrometry

- PCR

Polymerase Chain Reaction

Author’s contributions

WJH and CJZ are the co-first author and they contributed equally to this article. WJH: Conception and design of study, Performed the laboratory tests and analyzed the data, Writing-original draft, and Writing-review and editing. CJZ: Performed the laboratory tests and analyzed the data, Writing-original draft. LJY: Conception and design of study, Resources, Supervision, and Writing-review and editing. JWT: Writing-review and editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (8217121063).

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study involving human participants was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Shanghai Skin Disease Hospital in accordance with the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients/participants to participate in this study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Wenjing He and Chunjiao Zheng are the co-first author and they contributed equally to this article.

References

- 1.Prawer S, Prawer S, Bershow A. Superficial fungal infections. Clin Dermatology Ed. 2013;1:71. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gnat S, Łagowski D, Nowakiewicz A, Dyląg M. A global view on fungal infections in humans and animals: opportunistic infections and microsporidioses. J Appl Microbiol. 2021;131(5):2095–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ameen M. Epidemiology of superficial fungal infections. Clin Dermatol. 2010;28(2):197–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Das S, Bandyopadhyay S, Sawant S, Chaudhuri S. The epidemiological and mycological profile of superficial mycoses in India from 2015 to 2021: A systematic review. Indian J Public Health. 2023;67(1):123–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coulibaly O, L’Ollivier C, Piarroux R, Ranque S. Epidemiology of human dermatophytoses in Africa. Med Mycol. 2017;56(2):145–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pihet M, Le Govic Y. Reappraisal of conventional diagnosis for dermatophytes. Mycopathologia. 2017;182(1):169–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Formanek PE, Dilling DF. Advances in the diagnosis and management of invasive fungal disease. Chest. 2019;156(5):834–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schelenz S, Barnes RA, Barton RC, Cleverley JR, Lucas SB, Kibbler CC, et al. British society for medical mycology best practice recommendations for the diagnosis of serious fungal diseases. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;15(4):461–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Felix ITJ, Martins BA, Dos Santos CTB, Tristão RJ, Rodrigues ARA, De Ataíde MS, et al. The role of Trypan blue as a conventional and fluorescent dye for the diagnosis of superficial mycoses by potassium hydroxide (KOH) testing. Mycopathologia. 2023;188(5):815–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koo T, Kim MH, Jue M-S. Automated detection of superficial fungal infections from microscopic images through a regional convolutional neural network. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(8):e0256290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaiti R, Shrestha J, Dev M, Pradhan A. Refractive and binocular vision status and associated asthenopia among clinical microscopists. Kathmandu Univ Med J. 2022;20(4):499–504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mäder U, Quiskamp N, Wildenhain S, Schmidts T, Mayser P, Runkel F, et al. Image-Processing scheme to detect superficial fungal infections of the skin. Comput Math Methods Med. 2015;2015:851014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen H. Comparison of fluorescence staining and KOH wet film in the diagnosis of superficial fungal infections. China Health Standard Manage. 2018;9:108–9. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jin Y, Jiang Q, Li J. Zhan P. Fluorescent staining with hypersensitivity and enhancement for early diagnosis of superficial fungal infection. Chin J Clin Lab Sci. 2017;(12):736–8.

- 15.Sanketh D, Patil S, Rao RS. Estimating the frequency of Candida in oral squamous cell carcinoma using calcofluor white fluorescent stain. J Invest Clin Dent. 2016;7(3):304–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hu L, Zhou P, Zhao W, Hua H, Yan Z. Fluorescence staining vs. routine KOH smear for rapid diagnosis of oral candidiasis—A diagnostic test. Oral Dis. 2020;26(5):941–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Coronado-Castellote L, Jimenez-Soriano Y. Clinical and Microbiological diagnosis of oral candidiasis. J Clin Experimental Dentistry. 2013;5(5):e279–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Richardson MD, Warnock DW, Fungal Infection. DIAGNOSIS AND MANAGEMENT. United Kingdom: John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bao F, Fan Y, Sun L, Yu Y, Wang Z, Pan Q, et al. Comparison of fungal fluorescent staining and ITS rDNA PCR-based sequencing with conventional methods for the diagnosis of onychomycosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32(6):1017–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Singla N, Kundu R, Dey P. Artificial intelligence: exploring utility in detection and typing of fungus with futuristic application in fungal cytology. Cytopathology. 2024;35(2):226–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ahmad Z, Ervianti E. Dermoscopic examination in malassezia folliculitis. Berk Ilmu Kesehat Kulit Dan Kelamin-Period. Dermatology Venereol. 2022;34(2):130–6. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aslam M, Hafeez R, Ijaz S, Tahir M. Vulvovaginal candidiasis in pregnancy. Biomedica. 2008;24(January-June):54–6. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li J, Feng Y, Liu C, Yang Z, de Hoog S, Qu Y, et al. Presence of malassezia hyphae is correlated with pathogenesis of seborrheic dermatitis. Microbiol Spectr. 2022;10(1):e01169–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Posteraro B, De Carolis E, Vella A, Sanguinetti M. MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry in the clinical mycology laboratory: identification of fungi and beyond. Expert Rev Proteomics. 2013;10(2):151–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kozel TR, Wickes B. Fungal diagnostics. Cold Spring Harbor Perspect Med. 2014;4(4):a019299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gupta AK, Kohli Y, Summerbell RC. Molecular differentiation of seven malassezia species. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38(5):1869–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Becker PT, De Bel A, Martiny D, Ranque S, Piarroux R, Cassagne C, et al. Identification of filamentous fungi isolates by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry: clinical evaluation of an extended reference spectra library. Med Mycol. 2014;52(8):826–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Patel R. A moldy application of MALDI: MALDI-ToF mass spectrometry for fungal identification. J Fungi. 2019;5(1):4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Khurana U, Marwah A, Dey V, Uniya U, Hazari R. Evaluating diagnostic utility of PAS stained skin scrape cytology smear in clinically suspected superficial cutaneous mycoses: A simple yet unpracticed technique. J Family Med Prim Care. 2022;11(3):1089–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yao Y, Shi L, Zhang C, Sun H, Wu L. Application of fungal fluorescent staining in oral candidiasis: diagnostic analysis of 228 specimens. BMC Microbiol. 2019;19:1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Suneja M, Beekmann SE, Dhaliwal G, Miller AC, Polgreen PM. Diagnostic delays in infectious diseases. Diagnosis. 2022;9(3):332–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schwartz S, Kontoyiannis DP, Harrison T, Ruhnke M. Advances in the diagnosis and treatment of fungal infections of the CNS. Lancet Neurol. 2018;17(4):362–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.