Abstract

Objective

To illustrate the differences between K1 and K2 Klebsiella pneumoniae strains.

Methods

Totally 68 K1 and 99 K2 K. pneumoniae strains from GenBank were analyzed for virulence genes, sequence types (STs), restriction-modification (R-M) systems, and clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeat (CRISPR)-Cas systems. Phylogenetic trees of the virulence plasmids and chromosomes in the strains were built using kSNP4.

Results

Virulence genes peg-344, allS, p-rmpA, p-rmpA2, c-rmpA, iroN, and iucA were more prevalent in K1 strains than K2. K1 strains were categorized into 7 STs with 79.41% being ST23 while K2 strains were categorized into 14 STs with 38.38% being ST14. K1 strains showed higher rates of CRISPR-Cas systems than K2 while lower rates of Type I and II R-M systems were found in K1 strains than K2. More rates of virulence plasmids (52/68 vs. 24/99) were found in K1 strains than K2. Based upon the phylogenetic tree of virulence plasmids, 46 in K1 strains belonged to the same clade while 11 and 7 virulence plasmids in K2 strains constituted the 2 major clades. For the chromosomes, 61 K1 strains belonged to the same clade while 99 K2 strains could be categorized into 4 major clades.

Conclusions

K1 K. pneumoniae strains are more conserved than K2 for both virulence plasmids and chromosomes. K1 strains are deficient in R-M systems but rich in CRISPR-Cas, which is contrary to K2.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12864-025-11624-8.

Keywords: Klebsiella pneumoniae, Serotype, K1, Plasmid

Impact statement

K1 and K2 Klebsiella pneumoniae strains are typical hypervirulent pathogens and cause invasive infections. However, their differences are intriguing and to be elucidated. This study was based upon 68 K1 and 99 K2 genomes from GenBank. The yielded data showed that K1 strains are more conserved than K2 for sequence types, virulence plasmids, and chromosomes. In addition, K1 strains showed higher rates of clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeat (CRISPR)-Cas system than K2 while lower rates of Type I and II restriction-modification (R-M) systems were found in K1 strains than in K2. This study indicates different evolutionary propensities of K1 and K2 strains and the possible underlying reasons.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12864-025-11624-8.

Introduction

Klebsiella pneumoniae is ubiquitous and can cause all sorts of infections [1]. As a notorious member of “ESKAPE” [2], carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae continues to be listed as a priority by WHO this year. To date, K. pneumoniae strains consist of at least 79 serotypes [1]. Different serotype strains cause different infections. Typically, K1 and K2 strains often induce community-acquired infections while K47 and K64 usually cause hospital-acquired infections [3]. Due to the prevalent hypervirulence of K1 and K2 K. pneumoniae strains, they often cause invasive infections, e.g. pyogenic liver abscess, lung abscess, meningitis, and so on [4]. Clinical statistics also showed the different distribution of K1 and K2 strains in various sample sources [5].

K. pneumoniae could harbour various virulence factors, e.g. capsule, fimbriae, lipopolysaccharides, siderophores, and so on [1]. The invasiveness of K1 and K2 K. pneumoniae strains largely depends on their hypercapsules [6], which are regulated by the virulence genes p-rmpA and p-rmpA2 on the pLVPK-like virulence plasmids [7]. In addition, other features of K1 and K2 K. pneumoniae strains include sequence types (STs), drug-resistance genes, immune systems, and so on. Generally, K1 and K2 K. pneumoniae strains are thought to originate from one ancestor but may evolve along different routes.

The differences between K1 and K2 K. pneumoniae strains were rarely intensively illustrated. We once compared K1 and K2 strains causing pyogenic liver abscess and found lower rates of virulence genes allS and irp2 in K2 than K1 [8]. However, a limitation was the too small sample size. Pyogenic liver abscess is a typical and special invasive infection dominantly caused by K1 and K2 strains [9, 10, 11]. As far as K1 and K2 strains causing other infections are included, their more differences may appear. Here, we analyzed 68 K1 and 99 K2 strains from GenBank and found that K1 strains are more conserved than K2 for both virulence plasmids and chromosomes.

Methods

Genomes of K. pneumoniae strains

Totally 1658 K. pneumoniae genomes were analyzed for the serotypes, which were deposited in the GenBank Database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/datasets/genome/?taxon=573; download date: July 3rd, 2023). After that, 167 complete whole genomes (K1: Table S1; K2: Table S2) were included in this study, Sixty-eight K1 strains were isolated from the following areas: China mainland (43), USA (6), Taiwan (4), India (3), Hongkong (2), Australia (2), Korea (2), America (1), Russia (1), Spain (1), Kazakhstan (1), Japan (1), and United Kingdom (1). Ninety-nine K2 strains were from such areas: USA (26), China mainland (20), India (11), Australia (8), Japan (4), Chile (4), United Kingdom (4), France (3), Korea (3), Switzerland (3), Taiwan (2), Canada (2), Singapore (2), Czech (2), Thailand (1), Saudi Arabia (1), Kazakhstan (1), Germany (1), and Spain (1).

Determination of serotypes, virulence genes, sequence types, and virulence plasmids

The Accession Numbers of the 167 chromosomes were entered at the database of the Institute Pasteur website (https://bigsdb.pasteur.fr/cgi-bin/bigsdb/bigsdb.pl?db=pubmlst_klebsiella_seqdef_page=sequenceQuery) to yield their serotypes.

For the analyses of virulence genes, e.g. rcsA, rcsB, p-rmpA, p-rmpA2, c-rpmA, wzi, fimH, mrkD, entB, irp2, iroN, and iucA, the sequences of the 167 genomes were input at Virulence Factors of Pathogenic Bacteria website (http://www.mgc.ac.cn/cgi-bin/VFs/v5/main.cgi).

The outer membrane protein-related genes, e.g. ompK35, ompK36, ompK26, and ompK37, were predicted using the NCBI_BLAST website (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi?PROGRAM=blastn_PAGE_TYPE=BlastSearch_LINK_LOC=blasthome) with experimental support (Table S3), with 80% cut-off coverage and 80% cut-off identity.

The Accession Numbers of the 167 chromosomes were input at the multilocus sequence typing website (https://bigsdb.pasteur.fr/cgi-bin/bigsdb/bigsdb.pl?db=pubmlst_klebsiella_seqdef_page=sequenceQuery) and their STs were then obtained.

A plasmid harbouring p-rmpA or p-rmpA2 is denoted as a virulence plasmid.

Construction of phylogenetic trees

The tool kSNP4 [12] was used to identify single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) between all the virulence plasmids without needing a reference plasmid. The construction of a SNP-based phylogenetic tree using the maximum likelihood method reveals the clusters of plasmids. A clade indicates the distance of less than 0.1 in a phylogenetic tree. The SNP-based phylogenetic tree of chromosomes was built like virulence plasmids.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 8 software (GraphPad Software Inc., CA, USA). Chi-square and Fisher’s exact test were used for comparisons between K1 and K2 strains. Statistical significance was set at a p value less than 0.05.

Results

Distribution of various genes among K1 and K2 K. pneumoniae strains

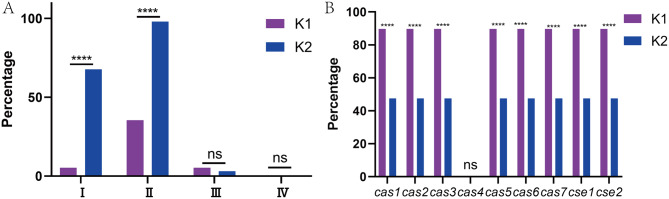

As shown in Fig. 1A, such virulence genes were more prevalent in K1 strains than K2: peg-344, allS, p-rmpA, p-rmpA2, c-rmpA, iroN, and iucA; the rates of other genes showed no significant differences. Positive rates of rcsA, rcsB, fimH, mrkD, and entB were all higher than 98.0% in both K1 and K2 strains.

Fig. 1.

Distribution of various genes in K1 and K2 K. pneumoniae strains (A) Distribution of virulence genes in K1 and K2 K. pneumoniae strains (B) Distribution of capsular polysaccharide-related genes in K1 and K2 K. pneumoniae strains (C) Distribution of outer membrane-related genes in K1 and K2 K. pneumoniae strains. ****, p < 0.0001; *, p < 0.05; ns, not significant

Fig. 1B showed that wza,wzc,wzx, and wzy were almost positive in all K1 strains but negative in all K2. Gene wzb was positive in all K2 strains but negative in all K1. Presence or absence of genes wza, wzb, wzc, wzx, and wzy confirms determination of serotypes. Positive rates of manC, galF, kvrA, kvrB, wcaJ, and wzi were all higher than 97.0% in both K1 and K2 strains.

Fig. 1C showed the rates of ompK35, ompK36, ompK26, ompK37, ompR, ompA, lamB, kbvR, envZ, and ramA were all higher than 93.0% in both K1 and K2 strains and showed no significant differences.

Since some aforementioned genes may exist on chromosomes or plasmids (Table S4), further statistics were made. Tables S4 to S6 showed their rates in genomes, chromosomes, and plasmids among K1 + K2, K1, and K2 strains, respectively. The vast majorities of the genes were located on either chromosomes or plasmids except peg-344 and iroN; their rates in K1 strains were higher than those in K2 whether for chromosomes or plasmids (p < 0.05). Therefore, the comparison conclusions in Fig. 1 were also applicable while chromosomes and plasmids were used for stratified analyses.

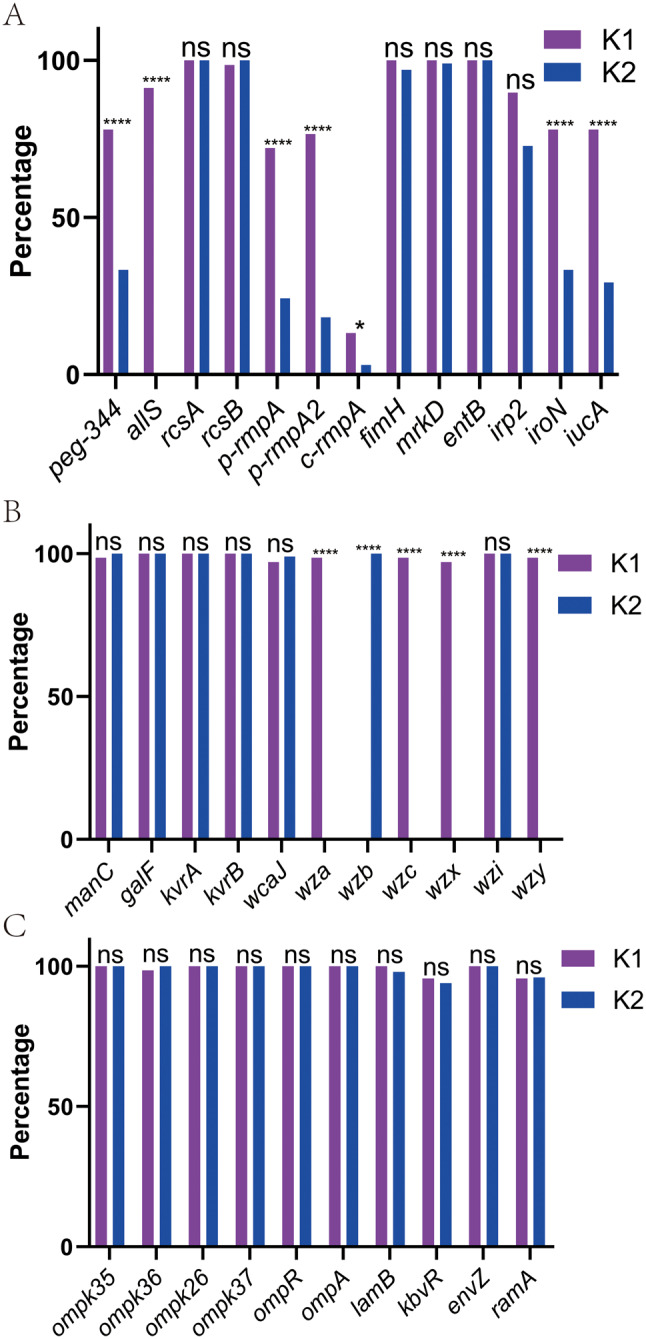

Distribution of STs among K1 and K2 K. pneumoniae strains

As shown in Fig. 2A, apart from not-defined STs, K1 strains were categorized into 7 STs with ST23 being predominant: 79.41%; apart from not-defined STs, K2 strains were categorized into 14 STs with ST14 being the most prevalent: 38.38% (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

Distribution of STs in K1 and K2 K. pneumoniae strains (A) Distribution of STs in K1 strains (B) Distribution of STs in K2 strains. ND, not defined

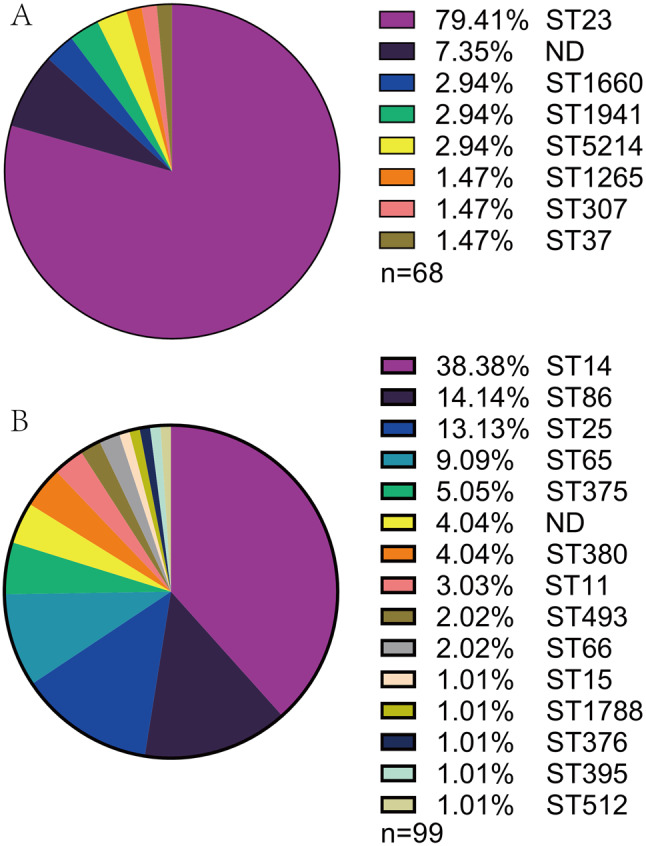

Distribution of R-M and CRISPR-Cas systems among K1 and K2 K. pneumoniae strains

As shown in Fig. 3B, cas4 was absent in both K1 and K2 strains; K1 strains presented higher rates of other cas (cas1-3 and cas5-7) and cse(cse1-2) subtypes than K2 strains. Fig. 3A confirmed lower rates of Type I and II R-M systems in K1 strains than K2 strains. Type III and IV R-M systems were almost absent in the 2 groups.

Fig. 3.

Distribution of R-M and CRISPR-Cas systems in K1 and K2 K. pneumoniae strains (A) Distribution of R-M systems in K1 and K2 strains (B) Distribution of CRISPR-Cas systems in K1 and K2 strains. ****, p < 0.0001; ns, not significant

The phylogenetic tree of virulence plasmids among K1 and K2 K. pneumoniae strains

As shown in Fig. 4, 68 K1 strains harboured 52 plasmids while 99 K2 isolates owned only 24 plasmids, presenting a higher rate in K1 strains than K2 (p < 0.0001). Among the 52 plasmids from K1 strains, 46 belonged to the same clade with a constituent ratio of 88.46%, showing high conservation. However, the 24 plasmids from K2 strains could be divided into 2 major clades with 11 and 7 strains respectively, presenting a more divergent propensity than those from K1.

Fig. 4.

The phylogenetic tree of virulence plasmids from K1 and K2 K. pneumoniae strains. The 76 plasmids were analyzed using kSNP4. Based on the predicted results, the binary gene presence/absence matrix was created reflecting the collection year, R-M system, CRISPR-Cas system, virulence genes, capsular polysaccharide-related genes, and outer membrane-related genes. The STs of the strains were marked on the right of the phylogenetic tree. The presence of genes, etc. is represented by a solid box and the absence of others is represented by a white box. ST, sequence type; ND, not defined; K1 strains are shown in blue while K2 strains are in green

The phylogenetic tree of chromosomes from K1 and K2 K. pneumoniae strains

As shown in Fig. 5, 61 K1 strains belonged to the same clade with a constituent ratio of 89.71%, showing high conservation; in the clade, 56 strains were ST23 and 35 strains were from China. However, 99 K2 strains could be categorized into 4 major clades (≥ 5 strains) with 41, 15, 14, and 15 strains, which corresponded majorly to ST14, ST86, ST25, and ST65 respectively.

Fig. 5.

The phylogenetic tree of chromosomes from K1 and K2 K. pneumoniae. The 167 chromosomes were analyzed using kSNP4. Based on the predicted results, the binary gene presence/absence matrix was created reflecting the collection year, R-M system, CRISPR-Cas system, virulence genes, capsular polysaccharide-related genes, and outer membrane-related genes. The STs of the strains were marked on the right of the phylogenetic tree. The presence of genes, etc. is represented by a solid box and the absence of others is represented by a white box. ST, sequence type; ND, not defined; K1 strains are shown in blue while K2 strains are in green

Discussion

Although K1 and K2 K. pneumoniae strains are both typically hypervirulent, they present significant differences in multiple aspects.

First, K1 and K2 strains showed different rates of virulence genes, i.e. peg-344, allS, p-rmpA, p-rmpA2, c-rmpA, iroN, and iucA (Fig. 1A). These genes are mostly carried by virulence plasmids [7], which is also the case in our study (Table S4–S6). Therefore, the difference is in line with the different rates of virulence plasmids (Fig. 4). The reason that the different virulence gene rates in K1 and K2 strains differ from our past study [8] may be the different sample sources, which was also found in another clinical report [13]; generally, the rates of plasmid-born virulence genes were higher than those in our study, e.g. rmpA, rmpA2, iucA, and peg-344; their samples sources included sputum, midstream urine, sterile blood, secretions, and throat swabs. Other chromosome-born virulence-related genes, i.e. rcsA, rcsB, fimH, mrkD, ompK35, ompK36, ompK26, ompK37, ompR, ompA, lamB, kbvR, envZ, and ramA showed no significant rates between K1 and K2 strains. For capsular synthesis channel genes, K1 strains are entirely different from K2: K1 harbours wza, wzc, wzx, and wzy but K2 does wzb.

Second, K1 and K2 strains showed different STs distribution: ST23 dominated K1 strains with a rate nearing 80.0%, which was also found in other reports [14, 15]; STs of K2 strains were rather diverse and the most prevalent ST14 only got a share of 38.38%. STs of K2 strains are some related to their isolation regions [13, 16–18]; ST65 is dominant in China while ST86 and ST395 are the major in Japan and Germany respectively. Seven house-keeping genes determine a ST [19]. Therefore, significantly different ST distribution of K1 and K2 stains reflects their divergent origins.

Third, both Fig. 4 and 5 confirmed the more conservation of K1 strains than that of K2. 88.46% of virulence plasmids in K1 strains belonged to the same clade while the 24 plasmids of K2 could be divided into 2 major clades with 11 and 7 strains respectively. 89.71% of K1 chromosomes belonged to the same clade while K2 chromosomes could be categorized into 4 major clades with shares of 41.41%, 15.15%, 14.14%, and 15.15%, which corresponded majorly to ST14, ST86, ST25, and ST65 respectively. This indicates different STs mean different clades. Figure 3 confirmed the different distribution of R-M and CRISPR-Cas systems: CRISPR-Cas systems are sufficient in K1 strains but R-M systems are sufficient in K2 strains. R-M systems are innate while CRISPR-Cas systems are adaptive [20]. We speculate the different distribution of R-M and CRISPR-Cas systems result in different conservation of K1 and K2 strains. Furthermore, the virulence plasmids of K2 strains originate from those of K1; such plasmids are usually not self-transferrable but could transfer under the help of other self-transferrable plasmids [21, 22]. The much lower rate of virulence plasmids in K2 strains than in K1 indicates their low transmission possibility and low retention rates.

This study has some limitations. The sources of K1 and K2 strains are not known. The statistics may be biased by the propensities of providers who deposited the K1 and K2 genomes in GenBank. This study is only an in silico investigation and lacks functional experiments.

In conclusion, K1 K. pneumoniae strains are more conserved than K2 for both virulence plasmids and chromosomes. K1 strains are deficient in R-M systems but are rich in CRISPR-Cas, which are contrary to K2.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Author contributions

P. D., T. H., and X. Y. conceived the study. P. D., T. H., X. Y., and S. M. collected the genomic sequences from GenBank. P. D., T. H., J. Z., and X. L. analyzed the data. P. D., T. H., and D. H. drafted the manuscript, which was revised by H. Z. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Zhejiang Provincial Health Commission (Recipient: Dakang Hu; Grant numbers 2023KY1326 and 2024KY535); the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Recipient: Haifang Zhang; Grant number: 82172332); and the Discipline Construction of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Soochow University (Recipient: Haifang Zhang; Grant number: XKTJ-TD2024003). The funding sources had no role in the study design; collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; the writing of the report; and the decision to submit the article for publication.

Data availability

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included in the Supplement and also deposited at Science Data Bank (https://www.scidb.cn/en/s/amQR3m).

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable. In addition, the study is not a clinical trial.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Piaopiao Dai, Tingting Huang, and Xinru Ye contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Dakang Hu, Email: 18111220048@fudan.edu.cn.

Haifang Zhang, Email: haifangzhang@suda.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Paczosa MK, Mecsas J. Klebsiella pneumoniae: going on the offense with a strong defense. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2016;80(3):629–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Oliveira DMP, Forde BM, Kidd TJ, Harris PNA, Schembri MA, Beatson SA, Paterson DL, Walker MJ. Antimicrobial resistance in ESKAPE pathogens. Clin Microbiol Rev 2020, 33(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Russo TA, Marr CM. Hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae. Clin Microbiol Rev 2019, 32(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Nakamura K, Nomoto H, Harada S, Suzuki M, Yomono K, Yokochi R, Hagino N, Nakamoto T, Moriyama Y, Yamamoto K, et al. Infection with capsular genotype K1-ST23 hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates in Japan after a stay in East Asia: two cases and a literature review. J Infect Chemother. 2021;27(10):1508–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ranjbar R, Fatahian Kelishadrokhi A, Chehelgerdi M. Molecular characterization, serotypes and phenotypic and genotypic evaluation of antibiotic resistance of the Klebsiella pneumoniae strains isolated from different types of hospital-acquired infections. Infect Drug Resist. 2019;12:603–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hu D, Chen W, Wang W, Tian D, Fu P, Ren P, Mu Q, Li G, Jiang X. Hypercapsule is the cornerstone of Klebsiella pneumoniae in inducing pyogenic liver abscess. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2023;13:1147855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dai P, Hu D. The making of hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae. J Clin Lab Anal. 2022;36(12):e24743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dong M, Ma X, Wang D, Ma X, Zhang J, Yu L, Yang Q, Hu D, Qiao D. Higher virulence renders K2 Klebsiella pneumoniae a stable share among those from pyogenic liver abscess. Infect Drug Resist. 2024;17:283–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yin D, Ji C, Zhang S, Wang J, Lu Z, Song X, Jiang H, Lau WY, Liu L. Clinical characteristics and management of 1572 patients with pyogenic liver abscess: A 12-year retrospective study. Liver Int. 2021;41(4):810–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lin Y, Chen Y, Lu W, Zhang Y, Wu R, Du Z. Clinical characteristics of pyogenic liver abscess with and without biliary surgery history: a retrospective single-center experience. BMC Infect Dis. 2024;24(1):479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang S, Zhang X, Wu Q, Zheng X, Dong G, Fang R, Zhang Y, Cao J, Zhou T. Clinical, Microbiological, and molecular epidemiological characteristics of Klebsiella pneumoniae-induced pyogenic liver abscess in southeastern China. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2019;8:166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gardner SN, Slezak T, Hall BG. kSNP3.0: SNP detection and phylogenetic analysis of genomes without genome alignment or reference genome. Bioinformatics. 2015;31(17):2877–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jiang M, Zhang H, Lu W, Qiu X, Lin C, Zhao R, Li Q, Wu Q. Molecular characteristics of virulence genes in Carbapenem-Resistant and Carbapenem-Sensitive Klebsiella Pneumoniae in relation to different capsule serotypes in Ningbo, China. Infect Drug Resist. 2024;17:2109–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anantharajah A, Deltombe M, de Barsy M, Evrard S, Denis O, Bogaerts P, Hallin M, Miendje Deyi VY, Pierard D, Bruynseels P, et al. Characterization of hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates in Belgium. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2022;41(5):859–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Du P, Liu C, Fan S, Baker S, Guo J. The role of plasmid and resistance gene acquisition in the emergence of ST23 Multi-Drug resistant, hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae. Microbiol Spectr. 2022;10(2):e0192921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Matsuda N, Aung MS, Urushibara N, Kawaguchiya M, Ohashi N, Taniguchi K, Kudo K, Ito M, Kobayashi N. Prevalence, clonal diversity, and antimicrobial resistance of hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae and Klebsiella variicola clinical isolates in Northern Japan. J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2023;35:11–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wahl A, Fischer MA, Klaper K, Muller A, Borgmann S, Friesen J, Hunfeld KP, Ilmberger A, Kolbe-Busch S, Kresken M, et al. Presence of hypervirulence-associated determinants in Klebsiella pneumoniae from hospitalised patients in Germany. Int J Med Microbiol. 2024;314:151601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Choi M, Hegerle N, Nkeze J, Sen S, Jamindar S, Nasrin S, Sen S, Permala-Booth J, Sinclair J, Tapia MD, et al. The diversity of lipopolysaccharide (O) and capsular polysaccharide (K) antigens of invasive Klebsiella pneumoniae in a Multi-Country collection. Front Microbiol. 2020;11:1249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Diancourt L, Passet V, Verhoef J, Grimont PA, Brisse S. Multilocus sequence typing of Klebsiella pneumoniae nosocomial isolates. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43(8):4178–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shen Z, Tang CM, Liu GY. Towards a better Understanding of antimicrobial resistance dissemination: what can be learnt from studying model conjugative plasmids? Mil Med Res. 2022;9(1):3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tian D, Liu X, Chen W, Zhou Y, Hu D, Wang W, Wu J, Mu Q, Jiang X. Prevalence of hypervirulent and carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae under divergent evolutionary patterns. Emerg Microbes Infect 2022:1–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Xu Y, Zhang J, Wang M, Liu M, Liu G, Qu H, Liu J, Deng Z, Sun J, Ou HY, et al. Mobilization of the nonconjugative virulence plasmid from hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae. Genome Med. 2021;13(1):119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included in the Supplement and also deposited at Science Data Bank (https://www.scidb.cn/en/s/amQR3m).