Summary

Purpose

Most people with epilepsy (PWE) reside in developing countries with limited access to medical care. In sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), traditional healers (THs) play a prominent role in caring for PWE, yet little is known about epilepsy care by THs. We conducted a multimethod, qualitative study to better understand the epilepsy care delivered by THs in Zambia.

Methods

We conducted focus-group discussions with THs, in-depth semistructured interviews with a well-recognized TH at his place of work, and multiple informal interviews with health-care providers in rural Zambia.

Results

THs recognize the same symptoms that a neurologist elicits to characterize seizure onset (e.g., olfactory hallucinations, jacksonian march, automatisms). Although THs acknowledge a familial propensity for some seizures and endorse causes of symptomatic epilepsy, they believe witchcraft plays a central, provocative role in most seizures. Treatment is initiated after the first seizure and usually incorporates certain plant and animal products. Patients who do not experience further seizures are considered cured. Those who do not respond to therapy may be referred to other healers. Signs of concomitant systemic illness are the most common reason for referral to a hospital. As a consequence of this work, our local Epilepsy Care Team has developed a more collaborative relationship with THs in the region.

Conclusions

THs obtain detailed event histories, are treatment focused, and may refer patients who have refractory seizures to therapy to other healers. Under some circumstances, they recognize a role for modern health care and refer patients to the hospital. Given their predominance as care providers for PWE, further understanding of their approach to care is important. Collaborative relationships between physicians and THs are needed if we hope to bridge the treatment gap in SSA.

Keywords: Traditional medicine, Epilepsy, Africa, Traditional healers

Of the 40 million people with epilepsy (PWE) worldwide, 80% live in developing countries (1). In sub-Saharan Africa, two-thirds to three-fourths of the rural population may have virtually no access to modern healthcare facilities (2). Despite moves to decentralize health care, resources have remained largely centralized and poorly allocated (3). Patients must travel long distances to seek medical attention (4). Travel costs can be prohibitive, and large urban settings may be menacing to rural villagers unaccustomed to city life and its dangers (5). Delays to see overworked healthcare providers may be substantial (6). Patients may arrive to find personnel on leave, medicines out of stock, or medical providers who lack needed expertise (7). User fees further deter health care seeking, particularly in vulnerable patient populations (8). Those who overcome these obstacles and access medical facilities may incur further expenses purchasing medicines or traveling to collect them.

PWE are especially likely to encounter barriers to medical care. Because recurrent seizures may limit a person’s ability to carry out the manual labor necessary for rural life, epilepsy causes economic losses (9). In sub-Saharan Africa, epilepsy is associated with tremendous stigma, which can worsen social and economic disadvantage (10). Where epilepsy is undertreated and stigmatized, PWE are less employable and less likely to earn a living (11). They may be unable to mobilize the social networks needed to provide the transportation, financial assistance, lodging, and psychological support required for seeking care in distant and underresourced medical facilities (12).

In this context, it is no surprise that PWE seek care from THs rather than from physicians. Not only are THs more physically accessible to patients, but they also offer greater cultural and conceptual familiarity. Hospital-based care is disease centered and may be unable to offer explanations of disease causality in an ecologically valid fashion (13). Conversely, THs focus on the patients and their social environments more than on their particular ailments, heavily emphasizing the psychological and social context of disease (14). Because patients in traditional cultures often believe psychological and social conflicts are a major cause of disease, failure of modern medicine to address these concerns may diminish the perceived power of modern medical interventions (15).

Reliance on traditional modes of health care in Africa is likely to increase as the gap between healthcare needs and resources widens under the increasing burden of poverty and the relentless human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) epidemic. Already 70% of patients in some areas initially seek health care from THs (16). Governments in developing countries have begun a dialogue with THs to facilitate some association with the formal healthcare sector. Recently, South Africa passed legislation to license its some 200,000 THs (17). Despite the global predominance of traditional healing for PWE and ongoing efforts to incorporate THs into the formal medical system, we know very little about how THs approach epilepsy care (18). We therefore undertook a multimethod qualitative study of THs in rural Zambia (19).

METHODS

Focus group

We solicited community health workers and tribal head-men within the Chikankata catchment area to identify THs (locally called Ng’anga) working in their area. These individuals were sent written invitations to attend a focus-group discussion held at a local high school. With delivery of written invitations, simultaneous verbal invitations were offered. A prominent community leader facilitated the discussion, which was conducted in the local language. One of the authors (G.B.) attended and transcribed the proceedings, with a translator providing real-time feedback. On completion, a tape-recorded transcript was reviewed and translated by a second translator. The two transcripts were then compared, reviewed, and discrepancies reconciled.

Structured interview

Mr. Amos Makoli, Coordinator and Disciplinary Chairperson for the Mazabuka District branch for the Traditional Health Practitioners Association of Zambia (THPAZ), attended the focus-group discussion and was willing to provide further information. Dr. Baskind conducted a semistructured interview with Mr. Makoli at Mr. Makoli’s place of work. An Epilepsy Care Team staff member was present and provided translation when needed. The interview was tape recorded and later transcribed. The transcript was then reviewed with the translator to check for accuracy. A summary statement of this interview was reviewed and approved by Mr. Makoli.

Informal interviews

Both authors interviewed doctors, clinical officers, nurses, community health workers, and members of the Epilepsy Care Team at Chikankata Hospital. Specific questions were asked regarding the frequency with which patients sought THs for epilepsy care, known modes of traditional healing methods for seizures, and local beliefs regarding seizure attribution.

CASE STUDY

A 6-year-old girl was brought to Chikankata outpatient department for generalized seizures and frontal scalp burns. According to the mother, at age 4 years, the child had a generalized tonic–clonic seizure while in the care of the paternal grandparents. The paternal grandparents consulted a traditional healer (TH), who attributed the convulsion to the angry spirit of the child’s dead father. After the father’s death, the paternal grandparents had confiscated the family’s assets, including this child, leaving the mother destitute. The mother had epilepsy, and the paternal grandparents did not believe her to be a fit parent, although she was taking phenobarbital (PB) with good seizure control. The TH invoked this breach of rightful inheritance as the cause of the child’s seizures and advocated that the child and some of the possessions must be returned to the mother for the seizures to stop. The child continued to have intermittent seizures and had at least two episodes of status epilepticus, possibly in the setting of malaria. Eventually, the grandparents returned the child to the mother.

The mother took the child to another TH, who treated the child with herbal steam tenting. During one of steaming sessions, the child fell forward onto a boiling steam pot and sustained burns to the forehead. The TH had assured the mother that with full treatment, the seizures would stop. However, when the mother was unable to pay the price of one live goat, the TH refused to complete treatment. The mother then decided to seek care at the hospital.

RESULTS

Human resources for epilepsy care

Eighteen healers were identified. Thirteen THs verbally accepted the invitation. Ten actually arrived (seven men and three women) and participated in the 2-day focus-group discussion. By simply questioning individuals residing in the Chikankata community, we easily identified 18 prominent THs practicing in the catchment area of 55,000 people, which is served by only four physicians. The THs live and work within local villages and are geographically distributed throughout the catchment region. The doctors and nurses we questioned universally assume a TH has already seen all PWE who seek care at the hospital, closely corroborating studies from other parts of sub-Saharan Africa (16). The THs we interviewed perceived themselves as the principal care providers for people who experience a seizure. See Table 1 for direct quotes illustrating the THs’ perspective, which is further detailed later.

TABLE 1.

Quotes from traditional healers

| Establishing terminology |

| “Convulsions involve falling out with jerking of the body and sometimes tongue biting, urination, or defecation. The eyes may also move.” |

| “Some people will stare and act strangely...chewing without food and hyperactivity” (TH demonstrates picking at clothes) |

| Diagnosis |

| GB: How do you diagnose epilepsy? Ng’anga: By several possible means. A diviner may know by use of methods including an axe, reading the beads, and communing with the ancestors. Not all ng’anga are diviners, and even those who are may diagnose by getting a history of convulsions. |

| “I have a child who has fits only after smelling rotten eggs. Then she has fits. But there is no smell. Only the child thinks there is an odor. She tells us this after she wakes up.”5 |

| Attribution |

| “The disease may run in the family or be caused by witchcraft.” |

| “The brain is injured and may function like a leaking pipe.” |

| “Seizures from malaria can be too severe; then the problem stays.” |

| “Pregnant women may have seizures … the treatment for this is bed rest. These women must be referred to the midwives at the hospital.” |

| Treatment |

| “They (PWE) want to be cured and given a reason for the condition. They don’t want to take tablets for so long.” |

Establishing terminology

Although several ChiTonga terms for seizure and epilepsy exist, the THs’ descriptions of seizures are highly congruent with medical descriptions. In addition to familiarity with generalized tonic–clonic seizures, the THs also described focal motor and complex partial seizures and recognized these events as being a form of seizure. The healers did not make an overt distinction between single, sporadic seizures, provoked seizures, and epilepsy.

Diagnosis

As suggested in Table 1, in addition to divination, the THs emphasized the importance of history taking. Details regarding seizure onset, preceding symptoms, and other periictal phenomena were reported to be especially important.

Attribution

All the THs interviewed believed witchcraft was responsible to some extent for seizures. The strong belief in witchcraft and sustained capacity for magical thought evident in rural Zambia may be difficult for Westerners to appreciate. These beliefs are not limited to the uneducated. Some of the trained health care workers we interviewed, including physicians, believe witchcraft plays a role in causing seizures. Belief in witchcraft as the ultimate cause for the condition does not preclude attributing proximate causes for seizures. For example, a spell cast on someone might cause him or her to develop seizures during a bout of malaria, when otherwise the malaria would not cause seizures. The healers reported a diverse range of specific circumstances that can result in seizures.

Treatment

For immediate management, the healers concurred that nothing should be placed in the patient’s mouth. They endorsed “blowing smoke up the nostril” to try to stop the seizure. They also identified bodily secretions (urine, feces, flatus, and saliva) as contagious substances that could potentially transmit seizures to bystanders. Treatments to “immunize” family members against epilepsy were advocated. The THs we interviewed endorsed the importance of giving the patient an explanation for the seizure.

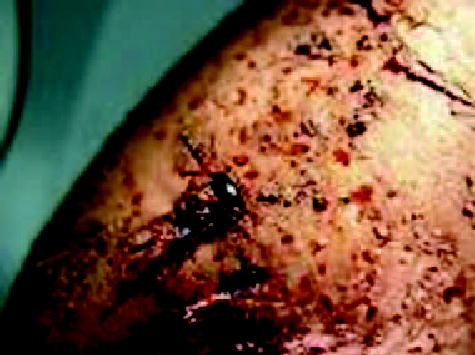

Witchcraft-induced seizures can be cured by treatment with an antidote comprising the same ingredients that were used in the original witchcraft. Treatment failures occur when the healer is unable to identify and obtain the correct ingredients. Popular ingredients for epilepsy treatment mentioned by both the THs and hospital health care workers were products from animals that exhibit behaviors resembling convulsions or loss of consciousness. Such animals are illustrated in Figs. 1–3. Some epilepsy cases cannot be cured. Burns are seen as a sign of intractable epilepsy. Many healers believe that the burn itself somehow seals the victim’s fate. Other studies have confirmed similar beliefs among THs in other sub-Saharan African regions (20).

FIG. 1.

Southern lesser bushbaby (Galago moholi).2 This animal feigns death when threatened.

FIG. 3.

Sweet potato weevil (Cylas formicarius).4 The adult feigns death when threatened

Referrals

THs may refer patients to another healer if their own therapies fail. Referrals are made to a more powerful healer or one who has access to different ingredients for use in treatment. THs also recognize a role for modern medicine in treating seizures and report referring patients to the hospital at times, especially when seizures occur within the context of certain other conditions (Table 2). Specific medical interventions such as “drips,” injections, and wound care were also cited as reasons to send patients to the hospital. Sometimes patients are referred simply because the healer feels his or her care has failed. To quote one of the traditional healers, “We are different doctors. They bring a patient to you. You start treating him or her.

TABLE 2.

Reasons traditional healers cited for referring patients with seizures to the hospital

| Body hotness (fever) |

| Pregnancy with breach presentation |

| Pregnancy with body hotness |

| Concomitant burns (acute or by history) |

| Concomitant malaria, tuberculosis, anemia, or other chronic disease |

| Head injury |

| Headache with opisthotonous (demonstrated by the TH) |

| Prolonged seizures |

| Multiple therapies failing |

Therefore, you try your level best, all your medicine you have. But that patient hasn’t become well. You are to tell them ‘no please, in my magic I have failed. Take her or him to the hospital. Maybe they will finish this disease he is having.’”

DISCUSSION

Significant economic limitations in sub-Saharan Africa continue to inhibit health systems development, and for the foreseeable future, modern medical systems alone cannot bridge the treatment gap for PWE. Despite numerous anthropologic (20–26) and some epidemiologic studies (27), emphasizing the important health-promoting role of THs in sub-Saharan Africa, modern health care has often viewed traditional healers with a mix of skepticism and suspicion (28). THs are an integral part of the health-care milieu in sub-Saharan Africa (29,30), and attempts to intervene medically, without collaboration with THs, are likely to fail.

Qualitative methods do not seek to find a representative sample of informants. Rather we used data from several sources to develop a basic understanding of the epilepsy care provided by THs in Zambia. When one triangulates this data with our clinical observations and previously gathered quantitative data, the information gathered appears to have substantial validity. For example, PWE seen by the Epilepsy Care Team with seizures characterized by focal motor or sensory phenomena generally have TH’s scarification or tattoos in the region affected at seizure onset. This supports the TH’s reports that they obtain detailed histories of seizure onset (31). Burns in Zambian PWE are associated with frequent seizures and therefore probably are indicative of a low likelihood of seizure freedom (32). The ingredients THs and hospital staff named as being important for traditional epilepsy treatments have been independently reported elsewhere (9; Haworth. Treatment for epilepsy: a description of a na’anga at work. 1978: p. 1–5, unpublished paper.).

Traditional medicines are not always benign. Negative consequences can result from TH care, such as the child’s burns in the case presentation. Care provided by THs can consume significant financial resources, but TH care may not be entirely without benefit. If a healer’s treatment allows the family members of a PWE no longer to fear contagion, perhaps the family is more willing to assist the PWE when they experience seizures—pull them from the fire, prevent them from drowning. In addition, after a first seizure, some individuals worry constantly about the possibility of another seizure. Many will never have a second seizure, or the next seizure will not occur for months or years (33). Perhaps the TH’s ritual treatment alleviates this worry and allows the person to return to the social fold as “normal.” At times, the THs seem to function as the community’s moral conscience—pointing out broken taboos and violated norms.

Regardless of how we choose to view THs and their care, from the perspective of PWE in rural Zambia, these individuals are central figures in healthcare provision. THs’ prominence in the lives of PWE requires that we understand and acknowledge their care. Any interventions aimed at increasing access to care and alleviating epilepsy-associated stigma must be inclusive of this group of providers.

Summary statement from “Dr. Zuma”1 (a.k.a. Amos Makoli)

A national association of ng’anga has been formed in Zambia to try to regulate practices and establish professional standards, but beliefs and practices remain varied among healers. There are no formal training schools or written books. Instead, most healers get their knowledge and skills from an older family member, or students may be apprenticed to a non–family member ng’anga. Ng’anga have different ideas about what causes epilepsy and how to treat this problem, but some ideas are shared. There are two types of epilepsy. One is a disease caused by witchcraft. Driven by jealousy or the desire to succeed in business, a person may, through magic, inflict epilepsy on another. The victim may no longer be able to earn money or may use all his money paying for treatments and seeking a cure. A second basic form of epilepsy is found when more than one family member has epilepsy. This may not be a result of witchcraft. This form is hard to treat and requires the TH to provide treatment to prevent disease in family members without epilepsy. In treating the type caused by witchcraft, the healer uses his supernatural powers to divine first the ingredients used to inflict the witchcraft on the sufferer. He may use certain enchanted objects to divine these ingredients. He then must gather those same ingredients as an antidote. Common ingredients are parts of insects or animals that themselves have convulsions (for example, a certain insect that, when molested, wiggles and then plays dead). The bushbaby feigns death to avoid attack. These are sought-after ingredients. Such insects or animal parts are mixed with plant parts in the same proportion as those used to inflict the epilepsy. The mixture is then applied to the skin, inhaled, or eaten. For the type of epilepsy that is found in families, treatment focuses on protecting family members without epilepsy. When such a patient goes to the ng’anga, other family members are given treatments to prevent spread of the illness. The need for such treatment is that convulsions of this type of epilepsy may be contagious. The contagion comes from saliva, stool, or urine, which, if contacted during or after a seizure, may transmit the disease. Treatment is not always effective. When an ng’anga admits that he is unable to know or locate the same ingredients used to cause epilepsy, he may refer to another ng’anga. Some ng’anga believe that if a person gets burned during a seizure, then the fits cannot be cured, so many ng’anga will not try to treat epileptics with a history of burns. Many of these patients go to the hospital for treatment of the burns but will go to other healers for treatment of the epilepsy. Ng’anga do refer patients for whom treatment has failed to the hospital. They can also receive self-referrals from the hospital. Modern doctors’ treatment failures are either due to their powerlessness against witchcraft or to underdosing of medication.

FIG. 2.

Bateleur eagle (Terathopius ecaudatus).3 This bird is described as a “tight-rope walker” that floats and balances still in the sky and then drops suddenly.

Acknowledgments

We thank Amos Makoli for his contribution to this work. His openness and patience were greatly appreciated. We are also grateful to Chieftainess Mwend, Mrs. Ellie Kalichi, for encouraging the THs and Chikankata health care providers to cooperate with one another in their care of her people. We also thank Mr. Charles Mabeta for his help with translations. Support for this work was provided by the Goldman Brothers Philanthropic Partnerships through their Charles E. Culpeper Medical Scholars program and NIH 1 R21 NS48060–01.

Footnotes

With contributions from Mr. Amos Makoli, Coordinator and Disciplinary Chairperson for the Mazabuka District branch of the Traditional Health Practitioners Association of Zambia.

During a later discussion, this TH concluded that rotten eggs must have been used in the witchcraft that caused this child's epilepsy.

This is the title Mr. Makoli uses professionally

References

- 1.Institute of Medicine. Neurological and psychiatric disorders: meeting the challenge in the developing world Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine, 2001:7.

- 2.Slikkerveer LJ. Rural health development in Ethiopia: problems of utilization of traditional healers. Soc Sci Med. 1982;16:1859–72. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(82)90447-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Birbeck GL, Kalichi EM. Primary healthcare workers’ perceptions about barriers to health services in Zambia. Trop Doct. 2004;34:84–6. doi: 10.1177/004947550403400208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Birbeck G, Munsat T. Neurologic services in sub-Saharan Africa: a case study of Zambian primary healthcare workers. J Neurol Serv. 2002;200:75–8. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(02)00132-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hjortsberg CA, Mwikisa CN. Cost of access to health services in Zambia. Health Policy Plan. 2002;17:71–7. doi: 10.1093/heapol/17.1.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stekelenburg J, Kyanamina S, Mukelabi M, et al. Waiting too long: low use of maternal health services in Kalabo, Zambia. Trop Med Int Health. 2004;9:390–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2004.01202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blas E, Limbambala M. The challenge of hospitals in health sector reform: the case of Zambia. Health Policy Plan. 2001;16(suppl 2):29–43. doi: 10.1093/heapol/16.suppl_2.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Malama C, Chen Q, De Vogli R, et al. User fees impact access to healthcare for female children in rural Zambia. J Trop Pediatr. 2002;48:371–2. doi: 10.1093/tropej/48.6.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kalumba K. The quiet black lamb: epilepsy in traditional African beliefs, in Community Health Research Unit Conference. Lusaka, Zambia: University of Zambia, 1983.

- 10.Jilek-Aall L, Rwiza HT. Prognosis of epilepsy in a rural African community: a 30-year follow-up of 164 patients in an outpatient clinic in rural Tanzania. Epilepsia. 1992;33:645–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1992.tb02341.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Begley CE, Famulari M, Annegers JF, et al. The cost of epilepsy in the United States: an estimate from population-based clinical and survey data. Epilepsia. 2000;41:342–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.2000.tb00166.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kleinman A, Wang WZ, Li SC, et al. The social course of epilepsy: chronic illness as social experience in interior China. Soc Sci Med. 1995;40:1319–30. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)00254-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cassel EJ. The nature of suffering and the goals of medicine. N Engl J Med. 1982;306:639–45. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198203183061104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hewson MG. Traditional healers in southern Africa. Ann Intern Med. 1998;128(12 Pt 1):1029–34. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-128-12_part_1-199806150-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tella A. The practice of traditional medicine in Africa. Niger Med J. 1979;9(5–6):607–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Puckree T, Mkhize M, Mgobhozi Z, et al. African traditional healers: what health care professionals need to know. Int J Rehabil Res. 2002;25:247–51. doi: 10.1097/00004356-200212000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sidley P. South Africa to regulate healers. BMJ. 2004;329(7469):758. doi: 10.1136/bmj.329.7469.758-b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Millogo A, Ratsimbazafy Z, Nubukpo P, et al. Epilepsy and traditional medicine in Bobo-Dioulasso (Burkina Faso) Acta Neurol Scand. 2004;109:250–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2004.00248.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stekelenburg J, Jager BE, Kolk PR, et al. Health care seeking behaviour and utilisation of traditional healers in Kalabo, Zambia. Health Policy. 2005;71:67–81. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2004.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gelfand M. Witch doctor, traditional medicine man of Rhodesia. With a foreword by Sir Roy Welensky London: Harvill Press, 1964, 191.

- 21.Rivers WHR, Kofoid CA. Medicine, magic, and religion: the Fitz Patrick lectures delivered before the Royal College of Physicians of London in 1915 and 1916. In: International library of psychology, philosophy and scientific method London: K. Paul Trench Trubner, Harcourt Brace. 1924;viii:146 (1).

- 22.Adekson MO. The Yorùa traditional healers of Nigeria New York: Routledge. 2003;xv:136.

- 23.Gumede MV. Traditional healers: a medical practitioner’s perspective Braamfontein: Skotaville Publishers, 1990;iv:238.

- 24.Nwokedike A. Folkmedicine in Iboland/Nigeria Düsseldorf: Institut für Geschichte de Medizin, 1980:58.

- 25.Maclean U. Magical medicine; a Nigerian case-study London: Lane, 1971:166.

- 26.Bryant AT. Zulu medicine and medicine-men Cape Town: C. Struik. 1966:115.

- 27.Gessler MC, Msuya DE, Nkunya MH, et al. Traditional healers in Tanzania: sociocultural profile and three short portraits. J Ethnopharmacol. 1995;48:145–60. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(95)01295-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Awaritefe A. Epilepsy: the myth of a contagious disease. Cult Med Psychiatry. 1989;13:449–56. doi: 10.1007/BF00052051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Selin H, Shapiro H. Medicine across cultures: history and practice of medicine in non-Western cultures. Science across cultures; v. 3 Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 2003;xxiv:416.

- 30.Jacobson-Widding A, Westerlund D, Humanistisk-samhällsvetenskapliga forskningsrådet (Sweden). Culture, experience, and pluralism: essays on African ideas of illness and healing Uppsala: 1989:308.

- 31.Birbeck GL. Seizures in rural Zambia. Epilepsia. 2000;41:277–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.2000.tb00156.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hampton KK, Peatfield RC, Pullar T, et al. Burns because of epilepsy. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1988;296:1659–60. doi: 10.1136/bmj.296.6637.1659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hauser WA, Rich SS, Annegers JF, et al. Seizure recurrence after a 1st unprovoked seizure: an extended follow-up. Neurology. 1990;40:1163–70. doi: 10.1212/wnl.40.8.1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]