Abstract

In developing gene therapy for cystic fibrosis (CF) airways disease, a transgene encoding a partially deleted CF transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) Cl− channel could be of value for vectors such as adeno-associated virus that have a limited packaging capacity. Earlier studies in heterologous cells indicated that the CFTR R (regulatory) domain is predominantly random coil and that parts of the R domain can be deleted without abolishing channel function. Therefore, we designed a series of CFTR variants with shortened R domains (between residues 708 and 835) and expressed them in well-differentiated cultures of CF airway epithelia. All of the variants showed normal targeting to the apical membrane, and for the constructs we tested, biosynthesis was like wild type. Moreover, all constructs generated transepithelial Cl− current in CF epithelia. Comparison of the Cl− transport suggested that the length of the R domain, the presence of phosphorylation sites, and other factors contribute to channel activity. A variant deleting residues 708–759 complemented CF airway epithelia to the same extent as wild-type CFTR and showed no current in the absence of cAMP stimulation. In addition, expression in nasal mucosa of CF mice corrected the Cl− transport defect. These data provide insight into the structure and function of the R domain and identify regions that can be deleted with retention of function. Thus they suggest a strategy for shortening the transgene used in CF gene therapy.

Airway disease is the major cause of morbidity and mortality in cystic fibrosis (CF), an autosomal recessive disease caused by mutations in the gene encoding the CF transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) Cl− channel (1). Gene transfer offers the potential for a new and effective treatment for CF airways disease (for reviews see refs. 2–4). Previous studies have shown the feasibility of transferring the CFTR cDNA to CF airway epithelial cells in vitro and in vivo. However, with most vectors two main problems limit gene transfer: gene transfer from the apical surface of differentiated airway epithelia is inefficient, and transgene expression is transient (2–4).

For developing CF gene therapy, adeno-associated virus (AAV) vectors have several potential advantages (for reviews see refs. 3, 5, and 6). AAV has already been successfully used to produce factor IX in humans with hemophilia B. In AAV vectors, viral genes are deleted, thereby minimizing cell-mediated immune responses. AAV vectors can transduce nondividing cells, such as airway epithelia. And transgene expression can be prolonged. Although, most previous studies have used type 2 AAV vectors, their receptors are on the basolateral membrane and thus inaccessible to vector applied apically (7). Recent studies have discovered that type 5 AAV can efficiently transduce well-differentiated human airway epithelia, and that its receptor lies on the apical membrane (8, 9). Type 6 AAV is also a promising vector for airway epithelia (10).

One limitation of AAV vectors is the small size of transgene that can be inserted. Studies testing the insert size suggest that 4,100–4,900 bp is the optimal genome size for packaging (11). In comparison, the coding sequence of full-length CFTR is 4,450 bp (12). Addition of the two inverted terminal repeats of AAV (300 bp) and minimal 3′ and 5′ untranslated regions (≈100 bp) yields an insert (4,850 bp) that leaves little room for promoter-enhancer elements, most of which are >600 bp. Some studies have attempted to circumvent this limitation by using AAV sequences as a promoter (13, 14). However, their utility in differentiated airway epithelia and in vivo is uncertain.

A potential solution to this problem is to shorten the transgene by selectively deleting coding sequence. This strategy has been proposed with a minidystrophin gene for Duschennes muscular dystrophy (15) and CFTR (13, 14). Here we examined the effect of deleting regions within the CFTR R (regulatory) domain (for reviews on the R domain see refs. 16–19). Several features make this domain an attractive target for deletion. Phosphorylation of the R domain by the cAMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA) controls CFTR Cl− channel activity. Although this domain contains several conserved serines that are phosphorylated by PKA, no one phosphoserine is required and several different phosphoserines contribute to regulation. Although the boundaries of the R domain are not precisely defined, they extend approximately from residues 634–708 at the N terminus to approximately 835 at the C terminus (16, 20, 21). Previous work has shown that residues 708–831 regulate activity, but in solution they are predominantly random coil (20). These data suggested that selective deletions might not severely disrupt structure and that retention of consensus phosphorylation sites might be sufficient for PKA-dependent regulation. Importantly, several earlier studies deleted portions of the R domain without abolishing channel function (13, 22–26).

These earlier studies suggested that a transgene with R domain deletions might be of value in gene therapy applications (13). However, some alterations induced channel activity in the absence of phosphorylation, reduced the response to PKA-dependent phosphorylation, and/or reduced net channel activity (13, 16, 22–26). Moreover, previous studies have only examined CFTR expressed in heterologous cell lines and studied activity by using the patch–clamp technique, planar lipid bilayers, or anion efflux. There was no information about their function in airway or other epithelia. Expression in epithelia is key in assessing their value for gene transfer because deletions could alter protein–protein interactions, targeting to the apical membrane, constitutive and stimulated activity, phosphorylation-dependent regulation, and perhaps toxicity.

This study had two goals. First, we tested the hypothesis that CFTR with truncations in the R domain could form Cl− channels in airway epithelia and complement the CF Cl− transport defect. Second, by studying a variety of constructs, we hoped to gain additional insight into the structure and function of the R domain. Therefore, we tested function in a model of the CF airway, well-differentiated cultures of human airway epithelia grown at the air–liquid interface (27). Because of the limited packaging capacity of AAV, we were not able to test the constructs in an AAV vector. Instead, we inserted the cDNAs into recombinant adenovirus vectors, which we used to infect epithelia through basolateral membrane receptors (28). This offers the advantage of testing a large number of constructs in differentiated CF epithelia. Moreover, the results should be applicable to any vector system.

Experimental Procedures

Construction of CFTR Variants.

CFTR variants were made in pTM1-CFTR4 by PCR deletion mutagenesis (Quik Change Mutagenesis, Stratagene) and confirmed by sequencing. Constructs were ligated into an adenovirus serotype 5 vector in which the cytomegalovirus promoter drives cDNA expression. CFTR variants are named by the residues that are deleted; for example in Δ708–835, residues between and including amino acids 708 and 835 are deleted. An identical adenovirus expressing green fluorescent protein (GFP) was used as a negative control. The University of Iowa Vector Core produced the recombinant adenovirus vectors.

Protein Biochemistry.

To confirm protein size and phosphorylation, HeLa cells were infected with 200 multiplicities of infection of recombinant adenovirus in Eagle's minimal essential media for 45 min. Cells were lysed 18–24 h later, and CFTR was immunoprecipitated and phosphorylated with [γ-32P]ATP and the catalytic subunit of PKA as described (29). For pulse–chase studies, HeLa cells were infected as above, and after 18–24 h cells were methionine-starved and labeled with [35S]methionine, and pulse–chase studies were carried out as described (30). Proteins were separated on 8% SDS/PAGE, stained, destained, dried, and exposed to phosphorscreens. After phosphorimaging, counts in bands B and C were quantitated.

Well-Differentiated CF Airway Epithelia.

Cultures of human airway epithelia were obtained from CF bronchus (ΔF508/ΔF508 or ΔF508/other genotypes) and cultured at the air–liquid interface as described (27). Epithelia were used at least 14 days after seeding when they were well differentiated with a surface consisting of ciliated cells, goblet cells, and other nonciliated cells (27). They also retained the functional properties of airway epithelia including transepithelial electrolyte transport and resistance. Epithelia were infected with 200 multiplicities of infection of adenovirus vector using 5 mM EGTA applied to the apical surface to transiently disrupt the tight junctions as described (28).

Immunocytochemistry.

Three days after gene transfer, epithelia were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100, blocked with 5% normal goat serum in SuperBlock (Pierce), and stained with anti-CFTR (24–1, R&D Systems) and anti-ezrin (a gift of Heinz Furthmayr, Stanford University, Stanford, CA) primary antibodies. Appropriate Alexa Fluor-conjugated secondary antibodies were then applied and epithelia were examined by confocal laser scanning microscopy. Figures show X-Z reconstructions.

Using Chamber Studies.

Three days after gene transfer, short-circuit current was measured in symmetrical solutions containing: 135 mM NaCl, 1.2 mM MgCl2, 1.2 mM CaCl2, 2.4 mM KH2PO4, 0.6 mM K2HPO4, 5 mM dextrose, and 5 mM Hepes, pH 7.4, as described (31). After measuring baseline current, we sequentially added mucosal amiloride (10−4 M), mucosal 4,4′-diisothiocyanatostilbene-2,2′-disulfonic acid (DIDS, 10−4 M); the cAMP agonists mucosal forskolin (10−5 M) plus 3-isobutyl-2-methylxanthine (IBMX, 10−4 M), and submucosal bumetanide (10−4 M) (see Fig. 2). For a limited number of studies, epithelia were treated with forskolin (10−5 M) and IBMX (10−4 M) for 24 h before study in Ussing chambers to minimize basal CFTR current.

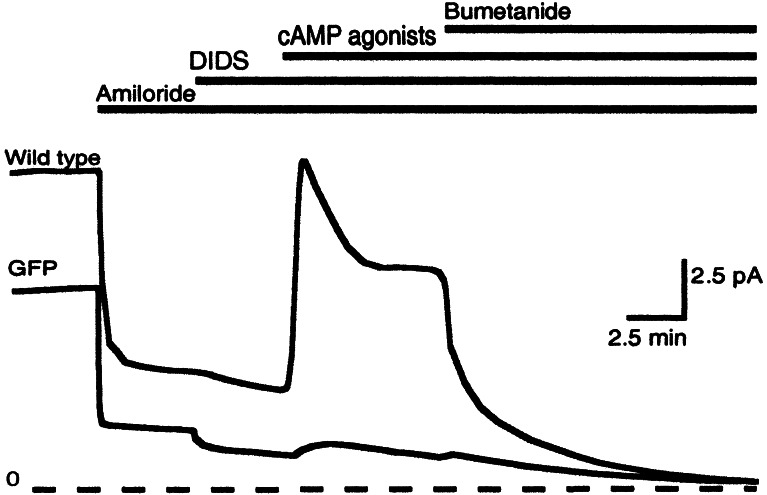

Figure 2.

Example of short-circuit current in well-differentiated airway epithelia. Epithelia expressing wild-type CFTR and GFP are indicated. Bars at the top indicate additions to solutions (see Experimental Procedures for details). Zero current level is shown by dashed line.

Patch–Clamp Studies.

The methods, solutions, and procedures for excised, inside-out patch–clamp recording were identical to those described (32). Patches containing multiple CFTR channels were studied at room temperature (≈24°C) in the presence of 1 mM ATP ± 75 nM PKA added to the bath solution. Membrane voltage was clamped at −40 mV; data were filtered at 100 Hz and digitized at 250 Hz.

Nasal Voltage Study in CF Mice.

For in vivo analysis, we used 6- to 8-wk-old ΔF508 homozygote CF mice (33). Mice were lightly anesthetized in a halothane chamber. Adenovirus vectors (5 × 109 particles) were administered intranasally as Ad:CaPi coprecipitates (34) in two 5-μl instillations delivered 5 min apart. Four days later animals were anesthetized with ketamine and xylazine, and the transepithelial electric potential difference across the nasal epithelium (Vt) was measured as described (33). During measurement of Vt, the nasal mucosa was perfused at a rate of 50 μl/min with a Ringer's solution containing: 135 mM NaCl, 2.4 mM KH2PO4, 0.6 mM K2HPO4, 1.2 mM CaCl2, 1.2 mM MgCl2, and 10 mM Hepes (pH 7.4 with NaOH). Three solutions were used: (i) Ringer's solution containing 100 μM amiloride; (ii) Ringer's solution containing 135 mM Na-gluconate substituted for NaCl plus amiloride; and (iii) Na-gluconate Ringer's solution containing 10 μM isoproterenol and amiloride. Measurements were made after perfusion for 5 min.

Results

Generation of CFTR with R Domain Deletions.

We selectively deleted portions of the R domain based on known PKA motifs and earlier structure and function studies (16–18). Because previous work showed that residues 708–835 are the largest deletion that yields a functional channel in mammalian cells (23), deletions were made in this region. In addition, we produced constructs that retained different numbers of the phosphoserines. Fig. 1 shows the deletion constructs. The cDNA for each variant was inserted into a recombinant adenovirus vector. Infection of HeLa cells produced approximately equivalent amounts of protein of the predicted size; it was recognized by CFTR antibodies and was phosphorylated in vitro by the catalytic subunit of PKA (not shown).

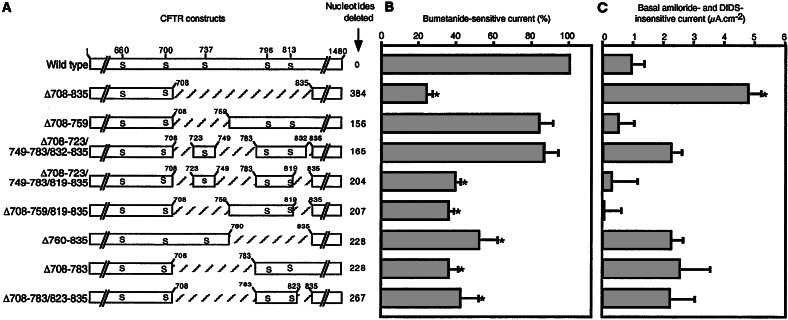

Figure 1.

CFTR variants and Cl− current in airway epithelia. (A) R domain sequence is shown graphically with portions deleted indicated by crosshatching. Serines that are phosphorylated in vivo are indicated with residue number at the top. First and last residue of deleted regions are indicated above each construct. Number of nucleotides deleted in each variant is shown on the right. (B) Bumetanide-sensitive short-circuit current in well-differentiated CF epithelia expressing the constructs shown in A. Data are difference in current generated by adding bumetanide corrected for current in GFP-expressing epithelia and normalized to current generated by wild-type CFTR. Bumetanide-sensitive current for epithelia expressing wild-type CFTR was 20.3 ± 1.6 μA⋅cm−2. * indicate value different from wild type (P < 0.05, one-way ANOVA). n = 18 for wild type and 6–15 for each variant. (C) Basal current measured in the presence of amiloride and DIDS and corrected for current in epithelia expressing GFP. All epithelia were pretreated with cAMP agonists for 24 h. * indicate value different from wild type (P < 0.05, one-way ANOVA). n = 3–6 for each construct.

Function of R Domain Variants in Well-Differentiated CF Airway Epithelia.

To learn whether the R domain variants can complement the CF Cl− transport defect, we expressed them in well-differentiated CF airway epithelia and measured the short-circuit current response to several interventions. Fig. 2 shows the interventions and an example of the currents. We sequentially added: (i) amiloride to inhibit apical Na+ channels, hyperpolarize the apical membrane, and thereby generate a driving force for Cl− secretory currents; (ii) DIDS to inhibit DIDS-sensitive apical Cl− channels; (iii) cAMP agonists to activate CFTR; and (iv) bumetanide to inhibit basolateral Cl− cotransport. Under these conditions, bumetanide-sensitive current provides the most accurate assessment of CFTR-dependent transepithelial Cl− transport.

All of the CFTR variants produced transepithelial Cl− currents (Fig. 1B). Because we tested the constructs in CF epithelia obtained from multiple different lungs, in each culture we compared responses of the variants to epithelia expressing GFP (as a negative control) and then normalized current to the response of wild-type CFTR. The Δ708–835 variant generated the least Cl− current, consistent with patch–clamp studies showing that this channel has a low open-state probability (35, 36). Two variants generated current similar to wild-type CFTR: Δ708–759 and Δ708–723/749–783/832–835. The other variants produced intermediate levels of Cl− current.

Amiloride-inhibited current has been reported to be increased in CF epithelia (37, 38). However, the responsible mechanism remains uncertain and a direct effect of CFTR on the Na+ currents has not been uniformly observed (38, 39). In these studies, we saw limited and variable effects on Na+ current. However in our studies, amiloride-inhibited current is influenced not only by the activity of epithelial Na+ channels, but also by the basal Cl− current, which is increased when amiloride hyperpolarizes the apical membrane. Moreover, in this study we did not control for the percentage of cells infected in different experiments. Although gene transfer to 5–10% of cells is sufficient to correct the CF Cl− transport defect (2–4), alteration of Na+ current may depend on the percentage of infected cells over a wide range (40).

Patch–clamp studies in heterologous cells demonstrated that some R domain deletion variants opened even without PKA phosphorylation; i.e., they were constitutively active (16). To assess constitutive activity, we first treated epithelia with cAMP agonists for 24 h before mounting them in Ussing chambers; this treatment minimizes basal CFTR Cl− channel activity (unpublished observations). Then we measured current remaining after treatment with amiloride and DIDS, but before addition of cAMP agonists (Figs. 1C and 2). Interestingly, Δ708–835 produced a large basal current, consistent with previous patch–clamp studies showing that it generates significant constitutive but little total Cl− current. Wild type and the other variants also showed some basal current, but because the amount of current was small and variable, it was not possible to draw conclusions about the level of constitutive activity.

Constitutive Activity of CFTR with R Domain Deletions.

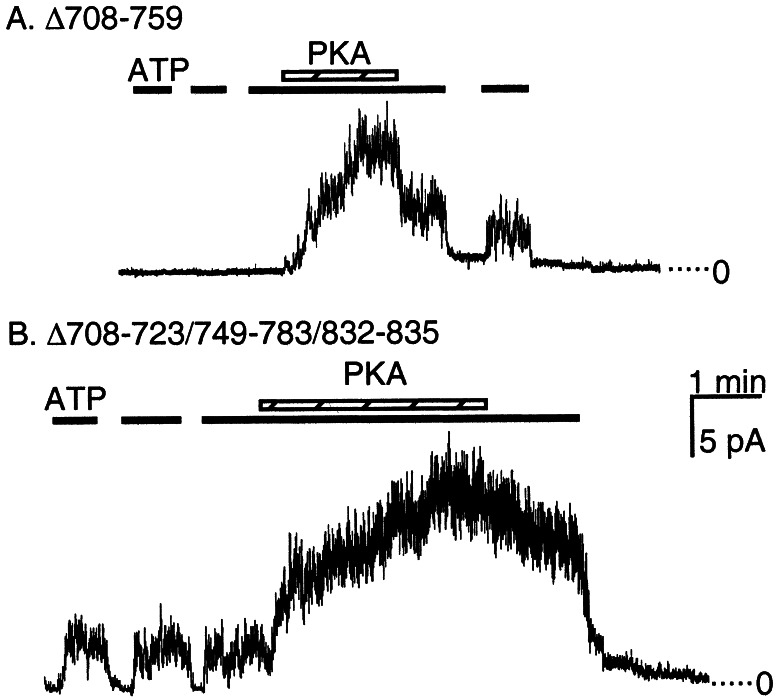

To test further for constitutive activity, we examined the two variants generating the largest Cl− currents in airway epithelia by expressing them in HeLa cells and measuring activity in excised, inside-out patches. Consistent with the transepithelial studies (Fig. 1C), Δ708–723/749–783/832–835, but not Δ708–759 generated constitutive current (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Representative current from indicated constructs in inside-out patches of membrane containing multiple CFTR channels. The presence of 1 mM ATP is indicated by a solid line and PKA by the crosshatched bar. (A) Δ708–759 showed no current before phosphorylation with PKA. (B) Δ708–723/749–783/832–835 activity was stimulated with ATP alone. The ratio of current with ATP alone to the maximal current with PKA and ATP was 0.22 ± 0.01, n = 4.

Biosynthesis and Localization of the R Domain Variants.

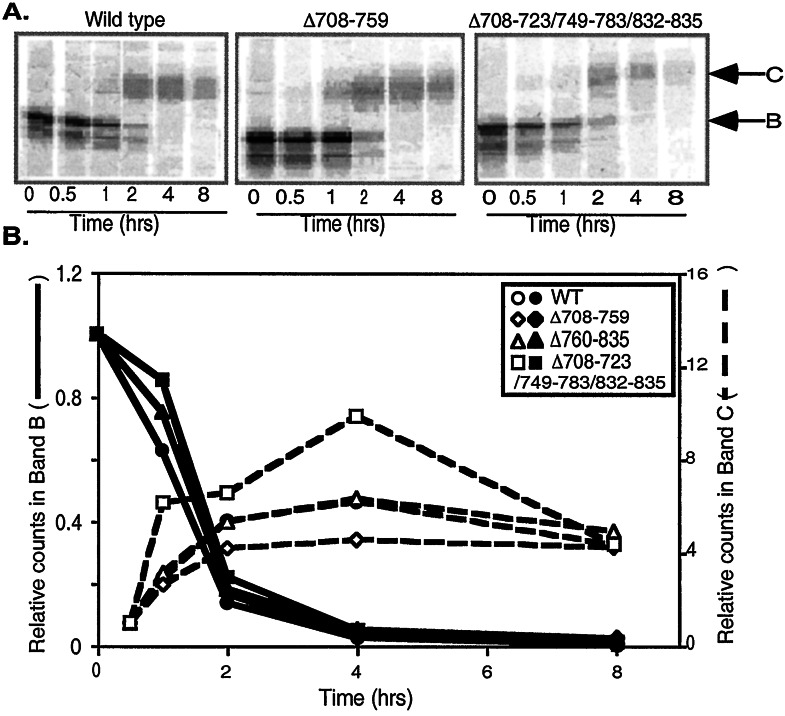

The glycosylation state of CFTR traces its progress through the biosynthetic pathway (41). In the endoplasmic reticulum, CFTR appears as a partially glycosylated intermediate, band B. In the Golgi complex, the protein becomes fully glycosylated, appearing as band C; this is the form that traffics to the plasma membrane. We used a pulse–chase analysis to assess biosynthesis of the R domain variants. Fig. 4 shows results for wild-type CFTR and three constructs. The rates at which band B disappeared and band C appeared were similar for each of the variants and wild type.

Figure 4.

Pulse–chase study showing disappearance of immature band B and appearance of mature band C CFTR. (A) Representative gels showing CFTR at indicated time after pulse with [35S]methionine. Positions of bands B and C are indicated. (B) Counts in band B (solid lines) and band C (dashed lines) were determined by phosphorimaging. Band B is shown as counts relative to counts at time = 0; band C is shown as counts relative to counts at time = 0.5 h. n = 3–4 for all points.

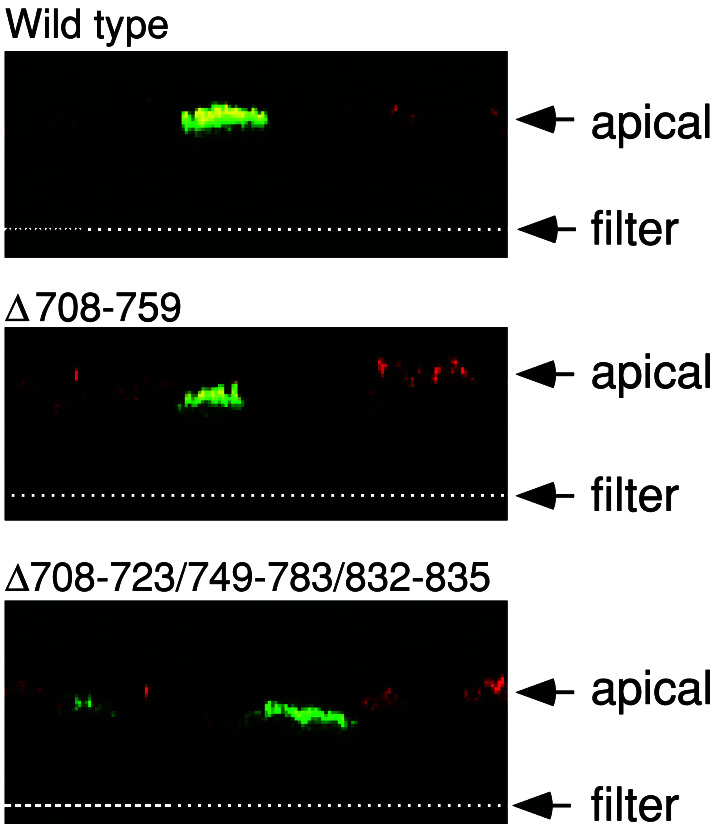

CFTR resides in the apical membrane of non-CF epithelia where it provides a pathway for Cl− flow (1); an apical location is critical for its function in transepithelial Cl− transport. We expressed the variants in well-differentiated CF airway epithelia and immunostained CFTR and examined the pattern of fluorescence with confocal microscopy. All of the constructs showed the same apical localization as wild-type CFTR; Fig. 5 shows examples for Δ708–759 and Δ708–723/749–783/832–835.

Figure 5.

Immunostaining of differentiated airway epithelia expressing indicated constructs. Data are X-Z confocal images. Arrows indicate position of the apical membrane and the top of filter support. Anti-CFTR immunostaining is green and anti-ezrin staining is red. Ezrin stains the apical region of the epithelial cells.

In Vivo Function of R Domain Variants in the Nasal Epithelia of CF Mice.

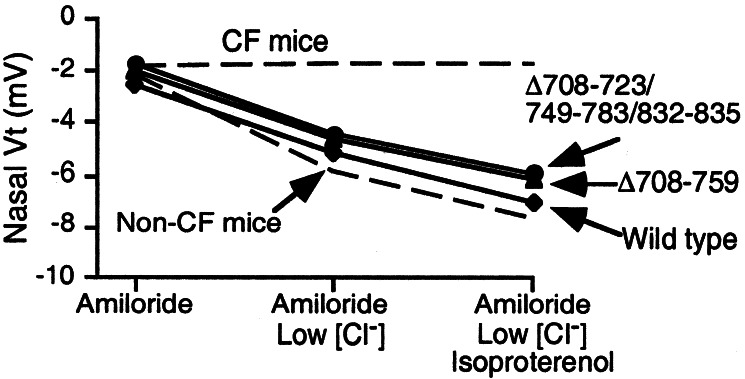

As an additional test of their combined biosynthesis, localization, and functional activity, we tested the variants in vivo. We infected nasal epithelia of CF mice (33) with adenovirus vectors expressing wild type and the two variants that generated the largest Cl− current in human airway epithelia. We treated epithelia with amiloride to inhibit Na+ channels and then measured Vt in response to perfusion with solutions containing a low Cl− concentration and isoproterenol to elevate cellular cAMP levels. Expression of Δ708–759 and Δ708–723/749–783/832–835 corrected the nasal voltage defect (Fig. 6) to a similar extent as wild-type CFTR and to levels similar to those we previously observed in non-CF mice (33).

Figure 6.

Voltage across nasal epithelium (Vt) in CF mice expressing indicated constructs in the nasal mucosa. Values of Vt obtained from untreated CF and wild-type mice are indicated by dashed lines (33). The three interventions are indicated at the bottom. n = 3 for wild type and 4 for the deleted variants.

Discussion

Our data show that CFTR constructs with multiple R domain deletions retain normal biosynthesis, apical targeting, and Cl− channel function when expressed in differentiated CF airway epithelia. These results have implications for developing CF gene therapy and understanding CFTR structure and function.

Evaluation of CFTR R Domain Deletions for Gene Transfer.

One goal of these studies was to generate a smaller CFTR transgene to accommodate the limited packaging capacity of AAV (11). Our data establish the feasibility of this strategy in vitro and in vivo. For optimal use in an AAV vector for CF gene therapy, the transgene would have two characteristics. The transgene would be short to facilitate packaging, and the protein product would correct the CF defect to the same extent as wild-type CFTR. Two constructs generated Cl− current similar to wild-type CFTR, Δ708–759 and Δ708–723/749–783/832–835, which deleted 156 bp and 165 bp, respectively. Δ760–835 generated the next greatest amount of Cl− current and deleted 228 bp.

Of these three constructs, Δ708–759 most closely resembled wild type, in that it produced no constitutive Cl− current. In contrast, Δ708–723/749–783/832–835 and Δ760–835 had greater basal Cl− currents than wild type and showed constitutive Cl− current when examined in patch–clamp studies (see ref. 29 for study of a channel closely related to Δ760–835). Whether constitutive channel activity would be an advantageous or an undesirable feature for gene therapy in airways is unknown. Certainly in vitro and in vivo non-CF airway epithelia show significant levels of Cl− transport before agonist stimulation, probably because of basal cAMP-dependent stimulation. Thus perhaps some level of constitutive activity would be beneficial. However, without knowing whether or not this is the case, the absence of constitutive activity makes Δ708–759 the most like wild type and thus the most suitable for further evaluation as a transgene for CF gene therapy. Although this construct deletes 156 nt, further deletions in the CFTR sequence (perhaps at the C terminus) or elsewhere in the transgene may be required for efficient packaging.

There are also theoretical limitations to using a partially deleted CFTR in gene therapy. For example, CFTR is reported to regulate more than 20 different channels, transporters, and other cellular functions (see ref. 38 for a review). Although the mechanisms are not well understood and the contribution to disease pathogenesis is uncertain, it is conceivable that CFTR missing part of the R domain might not restore such functions. It is also possible that a partially deleted construct might generate an immune response different from that of wild-type protein.

Structure and Function of the R Domain.

All of the variants targeted exclusively to the apical membrane, indicating that important apical targeting motifs are not likely located within this region of the R domain. The variants also showed normal biosynthesis, suggesting that sequences in the deleted regions are not required for normal processing. Apical targeting and biosynthesis were also normal in constructs with and without constitutive activity, suggesting that Cl− channel activity may not influence these processes. These conclusions are consistent with other studies showing that R domain deletions and missense mutations in this region of the R domain generate band C protein (25, 42). Our data are also consistent with studies showing that elimination of a single arginine-framed motif (residues 764–766) did not impair processing (43).

How phosphorylation of the R domain regulates activity and the relative importance of specific phosphoserines and sequences is uncertain (13, 22–26). Because we studied several deletions, our data allow conclusions and speculation about several aspects of R domain function.

Length.

In general, the more the R domain deleted, the less the Cl− current. However, length alone did not explain the results as evidenced by the finding that Δ708–783/823–835 (267 bp deleted) had as much current as Δ708–723/749–783/819–835 (204 bp deleted).

Specific phosphoserines.

Although all of the variants retained Ser-660 and Ser-700, the number of additional phosphoserines failed to predict the amount of current. For example, Δ760–835 (with one additional phosphoserine) had at least as much current as Δ708–783 (two additional phosphoserines) and Δ708–723/749–783/819–835 (three additional phosphoserines). These results are consistent with previous work suggesting that not all of the phosphoserines are necessary for activity and no one phosphoserine is dominant.

Charge.

We found no correlation between Cl− current and net charge present within the region between amino acids 708 and 835.

Ser-737.

Mutation of Ser-737 suggested it has an inhibitory function on CFTR studied in Xenopus oocytes (44). Our deletion mutants studied in airway epithelia did not reveal inhibition.

Residues 817–838.

This stretch of negatively charged amino acids has been suggested as a stimulatory region (26). Deletion of this region decreased current in Δ708–723/749–783/819–835 compared to Δ708–723/749–783/832–835. However, deletion of this region in Δ708–783/823–835 did not reduce current as compared with Δ708–783.

Residues 760–783.

We previously suggested that these residues prevented constitutive activity (29). Our present data support that hypothesis, but because we could not confidently evaluate low levels of current, our present data do not extend it further.

Structure.

The ability to alter the sequence of the R domain in so many different ways and yet retain Cl− channel function and phosphorylation-dependent activity supports the hypothesis that there are few or no required structural motifs in this portion of the R domain. That conclusion is consistent with our recent finding that this region of the R domain is predominantly random coil (20).

In considering these conclusions and comparing them to other data it is important to note that we were measuring transepithelial Cl− current and that the properties of differentiated airway epithelia may affect CFTR function. Thus it is not surprising that some conclusions might vary when comparing our present data to patch–clamp and bilayer studies and to studies performed with other heterologous expression systems. Nevertheless, it is interesting that there was such good agreement between our data and similar constructs examined in excised patches of membrane from heterologous cells. Finally, although our data provide insight, they leave open the question of precisely how the R domain controls function. Thus they emphasize the complex role of phosphorylation in regulating CFTR.

Acknowledgments

We thank Evan Sivesind, Pary Weber, Tammy Nesselhauf, Janice Launspach, and Theresa Mayhew for excellent assistance. We thank Dr. Heinz Furthmayr for the gift of the ezrin antibody. We appreciate valuable assistance from the following cores: the University of Iowa In Vitro Models and Cell Culture Core (supported by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, and the National Institutes of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases); the University of Iowa Vector Core (supported by the Roy J. Carver Charitable Trust; the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, and the National Institutes of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases); the Cell Morphology Core Facility (National Institutes of Health/National Institutes of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Grant ENGLH985O and the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation), and the DNA Core Facility (Diabetes and Endocrinology Research Center; supported by National Institutes of Health Grant DK25295). This work was supported by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute and the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation. C.R. is supported by a grant of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Ra 682/5–1). M.J.W. is an Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Abbreviations

- CF

cystic fibrosis

- CFTR

CF transmembrane conductance regulator

- AAV

adeno-associated virus

- R domain

regulatory domain

- PKA

cAMP-dependent protein kinase

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- DIDS

4,4′-diisothiocyanatostilbene-2,2′-disulfonic acid

- Vt

transepithelial electric potential difference across the nasal epithelium

References

- 1.Welsh M J, Ramsey B W, Accurso F, Cutting G R. In: The Metabolic and Molecular Basis of Inherited Disease. Scriver C R, Beaudet A L, Sly W S, Valle D, Childs B, Vogelstein B, editors. New York: McGraw–Hill; 2001. pp. 5121–5189. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davies J C, Geddes D M, Alton E W. J Gene Med. 2001;3:409–417. doi: 10.1002/jgm.200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Flotte T R. Curr Opin Mol Ther. 1999;1:510–516. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Welsh M J. J Clin Invest. 1999;104:1165–1166. doi: 10.1172/JCI8634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carter P J, Samulski R J. Int J Mol Med. 2000;6:17–27. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.6.1.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Athanasopoulos T, Fabb S, Dickson G. Int J Mol Med. 2000;6:363–375. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.6.4.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Summerford C, Samulski R J. J Virol. 1998;72:1438–1445. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.2.1438-1445.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zabner J, Seiler M, Walters R, Kotin R M, Fulgeras W, Davidson B L, Chiorini J A. J Virol. 2000;74:3852–3858. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.8.3852-3858.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Walters R W, Yi S M, Keshavjee S, Brown K E, Welsh M J, Chiorini J A, Zabner J. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:20610–20616. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101559200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Halbert C L, Allen J M, Miller A D. J Virol. 2001;75:6615–6624. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.14.6615-6624.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dong J Y, Fan P D, Frizzell R A. Hum Gene Ther. 1996;7:2101–2112. doi: 10.1089/hum.1996.7.17-2101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Riordan J R, Rommens J M, Kerem B S, Alon N, Rozmahel R, Grzelczak Z, Zielenski J, Lok S, Plavsic N, Chou J L, et al. Science. 1989;245:1066–1073. doi: 10.1126/science.2475911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang L, Wang D, Fischer H, Fan P D, Widdicombe J H, Kan Y W, Dong J Y. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:10158–10163. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.17.10158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Flotte T R, Afione S A, Solow R, Drumm M L, Markakis D, Guggino W B, Zeitlin P L, Carter B J. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:3781–3790. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Phelps S F, Hauser M A, Cole N M, Rafael J A, Hinkle R T, Faulkner J A, Chamberlain J S. Hum Mol Genet. 1995;4:1251–1258. doi: 10.1093/hmg/4.8.1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ostedgaard L S, Baldursson O, Welsh M J. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:7689–7692. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R100001200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sheppard D N, Welsh M J. Physiol Rev. 1999;79:S23–S45. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1999.79.1.S23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gadsby D C, Nairn A C. Physiol Rev. 1999;79:S77–S107. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1999.79.1.S77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ma J. News Physiol Sci. 2000;15:154–158. doi: 10.1152/physiologyonline.2000.15.3.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ostedgaard L S, Baldursson O, Vermeer D W, Welsh M J, Robertson A D. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:5657–5662. doi: 10.1073/pnas.100588797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Csanady L, Chan K W, Seto-Young D, Kopsco D C, Nairn A C, Gadsby D C. J Gen Physiol. 2000;116:477–500. doi: 10.1085/jgp.116.3.477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rich D P, Gregory R J, Anderson M P, Manavalan P, Smith A E, Welsh M J. Science. 1991;253:205–207. doi: 10.1126/science.1712985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rich D P, Gregory R J, Cheng S H, Smith A E, Welsh M J. Receptors Channels. 1993;1:221–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ma J, Zhao J, Drumm M L, Xie J, Davis P B. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:28133–28141. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.44.28133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vankeerberghen A, Lin W, Jaspers M, Cuppens H, Nilius B, Cassiman J J. Biochemistry. 1999;38:14988–14998. doi: 10.1021/bi991520d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xie J, Zhao J, Davis P B, Ma J. Biophys J. 2000;78:1293–1305. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76685-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Karp P H, Moninger T, Weber S P, Nesselhauf T S, Launspach J, Zabner J, Welsh M J. In: Epithelial Cell Culture Protocols. Wise C, editor. Totowa, NJ: Humana; 2002. , in press. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Walters R W, Grunst T, Bergelson J M, Finberg R W, Welsh M J, Zabner J. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:10219–10226. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.15.10219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baldursson O, Ostedgaard L S, Rokhlina T, Cotten J F, Welsh M J. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:1904–1910. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006934200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ostedgaard L S, Zeiher B, Welsh M J. J Cell Sci. 1999;112:2091–2098. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.13.2091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zabner J, Smith J J, Karp P H, Widdicombe J H, Welsh M J. Mol Cell. 1998;2:397–403. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80284-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carson M R, Travis S M, Welsh M J. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:1711–1717. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.4.1711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zeiher B G, Eichwald E, Zabner J, Smith J J, Puga A P, McCray P B J, Capecchi M R, Welsh M J, Thomas K R. J Clin Invest. 1995;96:2051–2064. doi: 10.1172/JCI118253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fasbender A J, Lee J H, Walters R W, Moninger T O, Zabner J, Welsh M J. J Clin Invest. 1998;102:184–193. doi: 10.1172/JCI2732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Winter M C, Welsh M J. Nature (London) 1997;389:294–296. doi: 10.1038/38514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rich D P, Berger H A, Cheng S H, Travis S M, Saxena M, Smith A E, Welsh M J. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:20259–20267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boucher R C J. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;150:271–281. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.150.1.8025763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schwiebert E M, Benos D J, Egan M E, Stutts J, Guggino W B. Physiol Rev. 1999;79:S145–S166. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1999.79.1.S145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nagel G, Szellas T, Riordan J R, Friedrich T, Hartung K. EMBO Rep. 2001;2:249–254. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kve045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Johnson L G, Boyles S E, Wilson J, Boucher R C J. J Clin Invest. 1995;95:1377–1382. doi: 10.1172/JCI117789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cheng S H, Gregory R J, Marshall J, Paul S, Souza D W, White G A, O'Riordan C R, Smith A E. Cell. 1990;63:827–834. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90148-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vankeerberghen A, Wei L, Jaspers M, Cassiman J J, Nilius B, Cuppens H. Hum Mol Genet. 1998;7:1761–1769. doi: 10.1093/hmg/7.11.1761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chang X, Cui L, Hou Y, Jensen T J, Aleksandrov A A, Mengos A, Riordan J R. Mol Cell. 1999;4:137–142. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80196-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wilkinson D J, Strong T V, Mansoura M K, Wood D L, Smith S S, Collins F S, Dawson D C. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:L127–L133. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1997.273.1.L127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]