Abstract

Previous work established that the principal sigma factor (RpoV) of virulent Mycobacterium bovis, a member of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex, restores virulence to an attenuated strain containing a point mutation (Arg-515→His) in the 4.2 domain of RpoV. We used the 4.2 domain of RpoV as bait in a yeast two-hybrid screen of an M. tuberculosis H37Rv library and identified a putative transcription factor, WhiB3, which selectively interacts with the 4.2 domain of RpoV in virulent strains but not with the mutated (Arg-515→His) allele. Infection of mice and guinea pigs with a M. tuberculosis H37Rv whiB3 deletion mutant strain showed that whiB3 is not necessary for in vivo bacterial replication in either animal model. In contrast, an M. bovis whiB3 deletion mutant was completely attenuated for growth in guinea pigs. However, we found that immunocompetent mice infected with the M. tuberculosis H37Rv whiB3 mutant strain had significantly longer mean survival times as compared with mice challenged with wild-type M. tuberculosis. Remarkably, the bacterial organ burdens of both mutant and wild-type infected mice were identical during the acute and persistent phases of infection. Our results imply that M. tuberculosis replication per se is not a sufficient condition for virulence in vivo. They also indicate a different role for M. bovis and M. tuberculosis whiB3 genes in pathogenesis generated in different animal models. We propose that M. tuberculosis WhiB3 functions as a transcription factor regulating genes that influence the immune response of the host.

The increased susceptibility of HIV-infected individuals and the emergence of multidrug-resistant strains of Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MTB) results in the death of 2–3 million people each year (1) and underscores the urgency of deciphering the molecular mechanisms of virulence of this pathogen. The highly variable protective efficacy of Mycobacterium bovis bacillus Calmette–Guérin in adults (0–80%; ref. 2) emphasizes the urgency for developing second-generation antituberculosis antimicrobial agents and vaccines. With these aims in mind, research stimulated by the advances in mycobacterial genetics (3, 4) has led to the identification of several genes that have been implicated in virulence (5–12).

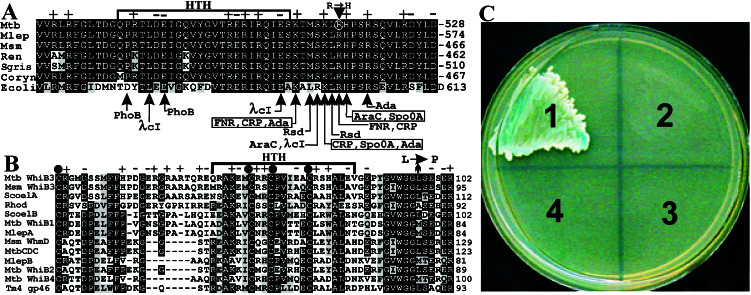

MTB requires sophisticated genetic mechanisms to recognize appropriate environmental signals and to convey this information to the transcriptional apparatus of the organism. The activation of bacterial sigma factors to regulate gene expression is an effective response mechanism that enables pathogens to respond instantly to a multitude of environmental signals. Bacterial σ70-type sigma factors are composed of four major regions, called regions 1, 2, 3 and 4 (13). Region 4 is subdivided further into sub regions 4.1 and 4.2; the latter is known to interact with the −35 region of promoters (13) and other transcription factors. Mutations in or close to the helix-turn-helix (HTH) motif in region 4.2 can result in either positive or negative effects on activation by transcription factors such as PhoB, AraC, cyclic-AMP receptor protein (CRP), λcI, and fumarate nitrate reductase regulator (FNR) (refs. 14 and 15; Fig. 1A), clearly pointing toward a role for this region in activation at activator-dependent promoters.

Figure 1.

(A) General diagram and alignment illustrating the C-terminal amino acids of RpoV (SigA) used as bait in the yeast two-hybrid system. Indicated are amino acids (vertical arrows) that affect activation by the corresponding transcription factors. The single point mutation (R515→H) causing attenuation of an MTB complex strain is circled. Mtb, M. tuberculosis; Mlep, M. leprae; Msm, M. smegmatis; Ren, Renibacterium salmoninarum; Sgris, Streptomyces griseus; Coryn, Corynebacterium ammoniagenes; Ecoli, E. coli. (B) Alignment of the most conserved regions of WhiB3-related proteins. Indicated are the four Cys residues (filled dots). A single amino acid substitution that abolishes sporulation in S. coelicolor, (Leu→Pro) is also indicated. S. coelicolor [ScoelA (T35596), ScoelB (CAC36616.1)], M. leprae [MlepA (CAC30314.1), MlepB (CAC31823.1)], M. tuberculosis CDC1551 (MtbCDC). Msm, M. smegmatis; Rhod, Rhodococcus opacus; TM 4 mycobacteriophage TM 4, gp49; +, positively charged residues; −, negatively charged residues. (C) The effect of the R515→H mutation on the interaction between RpoV and WhiB3 using the yeast two-hybrid system. S. cerevisiae PJ69–4α and S. cerevisiae PJ69–4A were transformed separately with pWB1 and the corresponding bait plasmids and mated. A heavy suspension of diploid cells were streaked out on SC lacking Ade and His and containing 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-α-d-galactopyranoside, incubated at 30°C, and photographed 4 days later. (1) S. cerevisiae [pWB1/pRpoV54]. (2) S. cerevisiae [pWB1/pRpoVR515H]. (3) S. cerevisiae [pLAM5′/pRpoV54]. (4) S. cerevisiae [pLAM5′/pRpoVR515H]. The control plasmid pLAM5′ contains the unrelated human lamin C protein fused to the DNA-binding domain.

A single point mutation in the 4.2 region of rpoV (sigA, Rv2703) was shown to be responsible for the loss of virulence of M. bovis, a member of the M. tuberculosis complex (16). This mutation, known to result in an Arg-515→His change, was originally suggested to influence recognition of the −35 promoter region (16). Therefore, it is possible that the mutation causes a change in promoter specificity and thus, abolishes or alters expression of a gene or subsets of genes essential for virulence. Alternatively, we and others (17, 18) have hypothesized that this mutation may alter the interaction of RpoV with a transcription factor that regulates expression of a gene(s) involved in virulence. Until now, the biological mechanism of attenuation caused by this mutation was unsolved, and the putative regulatory protein interacting with RpoV remained elusive.

In this study, we pursued a fresh approach by using the yeast two-hybrid system to identify the biological role of a mycobacterial protein, WhiB3, which interacts with the 4.2 domain of RpoV. We analyzed M. tuberculosis H37Rv (H37Rv) and M. bovis whiB3 mutants in mice and guinea pigs and showed that the H37Rv gene is dispensable for growth in both animal models, whereas the M. bovis whiB3 mutant was completely attenuated for growth in guinea pigs. Finally, we demonstrate that the survival of immunocompetent mice infected with the H37Rv whiB3 mutant is significantly prolonged despite bacterial organ burdens identical to that of mice infected with wild-type (wt) bacteria. These data have implications for experimental vaccine design against tuberculosis.

Methods

Strains and Media.

H37Rv and M. bovis ATCC35723 were cultivated as described (10, 16). Mycobacterial strains were transformed by using a previously described method (19). Escherichia coli DH10B, M15, and Tuner cells were grown in LB supplemented with carbenicillin (80 μg/ml), kanamycin (50 μg/ml), or hygromycin (180 μg/ml). When necessary, LB media were supplemented with isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside at a concentration of 1 mM. Yeast media were prepared as described in the CLONTECH Matchmaker manual.

Plasmid Constructs for Gene Disruption.

PCR was used to amplify a 2,467-bp DNA fragment containing whiB3 from cosmid MTCY28 (S. Cole, Institut Pasteur). The PCR fragment was blunted with T4 DNA polymerase and cloned into EcoRV-digested pBluescript IIKS(+) to create pKSwhiB3. Plasmid pKSwhiB3 was digested with AflII and StuI, blunted with T4 polymerase and ligated with a blunted loxP-hygromycin-loxP fragment to create pKSw3d. Plasmid pKSw3d was digested with XhoI and EcoRV, blunted and ligated with blunted BspHI-digested pYUB572 (20) to create pYUBwhiB. Aliquots of PacI-digested pYUBwhiB were ligated to PacI-digested phAE87 DNA (20) and packaged in vitro using the Packagene Lambda DNA packaging system (Promega). Logarithmically grown E. coli XL-Blue cells were transduced with the extract for 2 h at 30°C and plated out on LB containing hygromycin. Colonies were scraped from the plates, and plasmid DNA was isolated and electroporated (19) into Mycobacterium smegmatis mc2155. The resulting phage (φWhiB3) was used for the transduction of H37Rv, as described (20). Disruption of whiB3 in M. bovis was accomplished by electroporating alkali-denatured pYUBwhiB into M. bovis ATCC35723 and identifying an allelic exchange mutant by Southern blotting in a way similar to that described for disruption of another gene (21).

Two-Hybrid Screen.

The H37Rv yeast two-hybrid library was constructed as follows: H37Rv chromosomal DNA was partially digested with AciI and HpaI, size-fractionated (0.5–5 kb) and cloned into the unique ClaI site of pACT3, a pACT2 derivative (CLONTECH) containing a ClaI site in the multiple cloning site. An E. coli library was constructed containing ≈3.5 × 106 independent clones with inserts fused to DNA encoding the GAL4 DNA-activation domain (AD) of pACT3. Saccharomyces cerevisiae PJ69–4A (MATA trp1–901 leu2–3,112 ura3–52 his3–200 gal4 gal80 LYS2∷GAL1-HIS3 GAL2-ADE2 met2∷GAL7-lacZ) was transformed to yield approximately 50 × 106 yeast clones. The bait-containing plasmid pAS4 was a pAS2–1 (CLONTECH) derivative that contained the kanamycin resistance and URA3 genes. When necessary, bait-containing plasmids were transformed into S. cerevisiae PJ69–4α and mated with S. cerevisiae PJ69–4A, according to the CLONTECH Matchmaker manual.

Affinity Purification of Proteins and in Vitro Interaction.

Histidine-tagged WhiB3 was produced in E. coli M15 containing pWhiB3. Plasmid pWhiB3 contains the complete ORF of whiB3 cloned into pQE32 (Qiagen, Chatsworth, CA). Recombinant GST-RpoV was produced in Tuner cells containing pRpoV. Plasmid pRpoV contains DNA representing amino acids 369 to 528 of RpoV cloned into pGEX-4T-1 to form a fusion with glutathione S-transferase (GST; designated GST-RpoV). WhiB3(his) was purified by using Ni2+-NTA columns, and GST-RpoV was purified by using glutathione Sepharose 4B beads. SDS/12% PAGE and surface-enhanced laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight-mass spectrometry (SELDI-TOF; Ciphergen Biosystems, Fremont, CA) was used to assess the purity of each protein.

Mice and Guinea Pigs.

C57BL/6 and BALB/cJ mice (6–8 weeks old) were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory and were infected intravenously through the lateral tail vein. The titer of the inoculum was confirmed by dilution plating of organ homogenates at 24 h after injection. At several time points after infection, colony-forming units (cfu) in lung, liver, and spleen were determined by plating serial dilutions of organ homogenates on 7H10 media containing the appropriate antibiotics (10). Virulence of H37Rv and M. bovis strains also was tested by s.c. inoculation into female Duncan–Hartley guinea pigs. Animals were killed after 9 weeks, and the spleens were examined for gross lesions and cfu.

SELDI-TOF.

The Ciphergen PBS II ProteinChip reader was used to analyze protein–protein interactions and purity of proteins according to the Ciphergen ProteinChip Users Guide. GST fusion proteins and control samples (0.5–5 μl) were analyzed on hydrophobic (H4) chips, whereas WhiB3(his) was analyzed on immobilized metal affinity capture (IMAC-3) chips. In vitro interaction between GST-RpoV and immobilized WhiB3(his) was performed essentially as described (22) except that PBS with 0.2% Triton X-100 was used as incubation buffer. A saturated solution of α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid in 50% acetonitrile and 0.5% trifluoroacetic acid or ferulic acid in 50% isopropanol and 0.5% trifluoroacetic was used as matrix.

Southern Blot Hybridization.

Genomic DNA was isolated from H37Rv and M. bovis strains (10), digested with restriction enzymes, and subjected to agarose gel electrophoresis. Southern blot analysis was performed according to standard methods (10).

Histopathological Analysis.

Mouse organs were fixed overnight in 10% (vol/vol) phosphate-buffered formalin, embedded in paraffin, and processed for histological examination. Slides were stained with hematoxylin and eosin.

Statistical Analysis.

Differences between survival times was determined with the logrank test by using GraphPad PRISM V.3 for Windows (GraphPad, San Diego).

Results

Yeast Two-Hybrid Screen for Interaction of H37Rv Proteins with RpoV.

To screen for proteins that interact exclusively with the 4.2 region of RpoV in which the Arg-515→His mutation is localized (Fig. 1A), a 175-bp rpoV DNA fragment (representing amino acids 474–528 and designated BD-RpoV54) was cloned in-frame with the yeast DNA-binding domain (DNA-BD) of pAS4 to generate plasmid pRpoV54. Mating of S. cerevisiae PJ694α [pRpoV54] with the H37Rv library transformed into S. cerevisiae PJ69–4A yielded several yeast colonies able to grow on synthetic complete (SC) plates lacking adenine (Ade) and histidine (His). Four S. cerevisiae clones (WB1–4) were identified that specifically interacted with S. cerevisiae [pRpoV54] and grew on SC lacking Ade and His and activated lacZ expression. Activation of all three reporter genes under control of three different promoter elements strongly suggests a true interaction. Sequence analysis of plasmids pWB1–4 isolated from clones WB1–4 showed that all four of the plasmid inserts contained in-frame fusions of the DNA-AD of pACT3 with the full-length ORF of H37Rv whiB3 (Rv3416) (designated AD-WhiB3).

The deduced amino acid sequence of WhiB3 corresponds to a protein of 102 amino acids with an HTH DNA-binding motif at position 48–70. The presence of four highly conserved Cys residues became evident when they were aligned with orthologues present in several microorganisms (Fig. 1B). Multiple orthologues are present in Streptomyces spp, Mycobacterium leprae, Mycobacterium smegmatis, and also in H37Rv, which contains seven WhiB homologues (23).

S. cerevisiae [pWB1/pRpoV54] was able to grow on plates of SC lacking Ade and His and containing 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, or 10 mM 3-amino-1,2,4-triazole, a natural inhibitor of His imidazole glycerol phosphate dehydratase (HIS3). This suggests a strong and specific interaction between BD-RpoV54 and AD-WhiB3. Because we initially hypothesized that the Arg-515→His mutation abolished or reduced interaction of an unknown transcription factor with the 4.2 region of RpoV, we independently cotransformed pRpoVR515H (pRpoV54 with the Arg-515→His mutation) and pRpoV54 into S. cerevisiae [pWB1]. S. cerevisiae [pWB1/pRpoVR515H] was unable to grow on SC lacking both Ade and His (Fig. 1C), thus strongly suggesting that the Arg-515→His mutation in BD-RpoVR515H diminishes or abolishes the interaction of WhiB3 with RpoV. To examine more closely the contribution of other regions outside of the 4.2 region of RpoV toward the interaction with WhiB3, we cloned a 581-bp PCR fragment (representing amino acids 338–528 and designated BD-RpoV191) in-frame with the DNA-BD of pAS4 to create pRpoV191. Subsequent co-transformation of pRpoV191 and pWB1 also resulted in growth of S. cerevisiae [pWB1/pRpoV191] on SC lacking both Ade and His (results not shown). However, LacZ filter-lift assays showed that for S. cerevisiae [pWB1/pRpoV54] a blue color developed after 15 min vs. 90 min for S. cerevisiae [pWB1/pRpoV191] (results not shown). We conclude that Arg-515 in the 4.2 region of RpoV is critical for optimal interaction with WhiB3, and that the affinity of BD-RpoV54 for AD-WhiB3 is greater than that of BD-RpoV191, suggesting that the tertiary structure of RpoV influences interaction with WhiB3.

Interaction of WhiB3 and RpoV in Vitro.

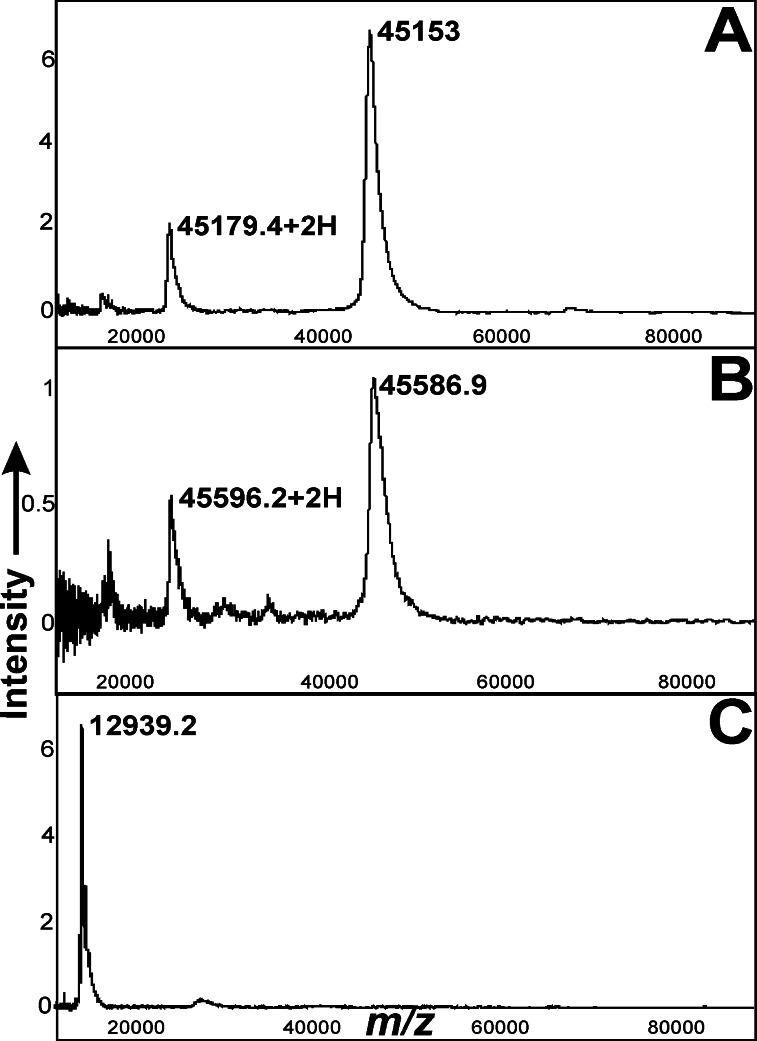

To corroborate the interaction of WhiB3 with RpoV observed in the yeast two-hybrid system, we overexpressed and purified from E. coli WhiB3 tagged with an His epitope [WhiB3(his)] and amino acid 369–528 of RpoV fused to GST-RpoV. SELDI-TOF analysis of samples spotted on IMAC-3 and H4 chips showed peaks corresponding to WhiB3(his) (m/z 12939.2+H) and GST-RpoV (m/z 45153+H), respectively (e.g., see Fig. 2). The hydrophobic surface of H4 chips contains 16 methylene groups that bind proteins through reverse-phase chemistry. However, on this surface, WhiB3(his) was inefficiently bound and, therefore, was captured on IMAC-3 chips. These chips contain nitrilotriacetic acid groups that chelate Ni2+ and, therefore, are highly effective in binding His-tagged WhiB3.

Figure 2.

In vitro interaction of immobilized WhiB3(his) with GST-RpoV using SELDI-TOF. Proteins were analyzed on H4 or IMAC-3 chips. (A) Purified GST-RpoV analyzed on a hydrophobic H4 chip. (B) The eluate analyzed on an H4 chip. The hydrophobic surface of the H4 chip preferentially captured GST-RpoV but not WhiB3(his) (laser intensity 270; sensitivity 9). Because the matrix solution disrupts noncovalent complexes, each protein is represented by a separate peak. Intriguingly, the apparent m/z of GST-RpoV in the eluate was altered slightly but consistently. (C) Analysis of the eluate on an IMAC-3 chip. The eluate was dialyzed against PBS to remove the imidazole, incubated on the IMAC-3 surface for 30 min to allow binding of WhiB3(his) to the chelated Ni2+, and washed with sterile water before analysis. Under these conditions, GST-RpoV did not bind to the IMAC-3 surface and was not observed in the spectra. Peaks corresponding to WhiB3(his) were observed by using a laser intensity of 240 and a sensitivity of 9. Mass identification was made by 100 average shots with the Ciphergen PBS II ProteinChip reader. Note the double-charged ions (+2H) in A and B. External calibration was performed as suggested by the manufacturer.

We studied complex formation between WhiB3(his) immobilized on Ni2+-agarose and GST-RpoV along with the control proteins GST and conalbumin. SELDI-TOF analysis of the eluate clearly indicated the presence of both GST-RpoV (m/z 45586.9+H) (Fig. 2B) and WhiB3(his) (m/z 12939.2+H) (Fig. 2C) on H4 and IMAC-3 chips, respectively, and confirm that WhiB3(his) associates with GST-RpoV. Our control reaction showed that nonspecific binding of GST-RpoV to the Ni2+-agarose was insignificant. We also independently incubated purified control proteins GST or conalbumin with immobilized WhiB3(his). As expected, analysis of these extracts on H4 or IMAC-3 chips showed peaks for GST (m/z 29140.3+H) and conalbumin (m/z 77814.6+H) only before the washing step, whereas no peaks could be detected in the eluates (not shown). We conclude that the in vitro interaction experiments support the in vivo yeast data, confirming the interaction between WhiB3 and RpoV.

Construction of whiB3 Mutants of H37Rv and M. bovis.

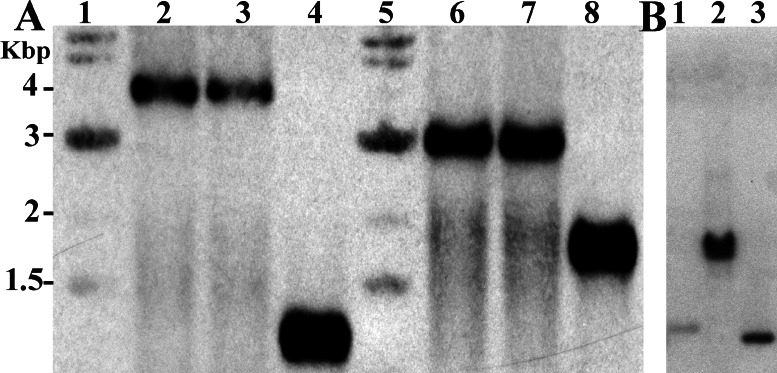

The original genetic complementation experiments performed by Collins et al. (16) showed that RpoV from virulent M. bovis could restore virulence to an attenuated M. bovis strain. We reasoned that disruption of whiB3 in both H37Rv and M. bovis would provide an ideal opportunity to study, in parallel, the effect of the mutation on virulence in two species of the MTB complex by using two animal model systems. Therefore, we introduced targeted null mutations at the whiB3 loci of H37Rv and virulent M. bovis ATCC35723 by using a conditionally replicating phage (φWhiB3; ref. 20) or a suicide plasmid (21), respectively. More than 90% of H37Rv and M. bovis whiB3 (H37Rv and M. bovis whiB3 are identical) was deleted and replaced with a loxP-hygromycin-loxP fragment. Likely polar effects were excluded because the genes adjacent to whiB3 (Rv3417c and Rv3415c) are transcribed in opposite directions to that of whiB3. Transduction of H37Rv with φWhiB3 resulted in 22 colonies on 7H10 plates containing hygromycin after 4 weeks of incubation. M. bovis ATCC35723 was electroporated with pKSw3d and screened for single and double crossover events. Southern blot hybridization of two H37Rv clones (WB1 and WB2; Fig. 3A) and several M. bovis clones revealed that WH1, WH2, and a single M. bovis clone (B1) contained the desired chromosomal whiB3 mutations (Fig. 3B). Probing NcoI- and BsmB1-digested chromosomal DNA of WH1, WH2, and B1 with a 974-bp NcoI/StuI fragment (immediately upstream of the whiB3 ORF) showed the loss of the wt 1,750-bp fragment and the presence of the insertionally inactivated alleles (NcoI, 3,005 bp; BsmB1, 3,056 bp). The H37Rv and M. bovis ATCC35723 whiB3 mutant strains are referred to here as MTwb3H and MBwb3H. All wt and mutant strains showed similar growth and colony morphology on 7H10 agar plates or in 7H9 liquid media. Therefore, we conclude that whiB3 is not required for in vitro growth of H37Rv or M. bovis ATCC35723.

Figure 3.

Disruption of the H37Rv and M. bovis ATCC35723 whiB3 loci. (A) Southern blot analysis of H37Rv parental (lanes 4 and 8) and two hygromycin resistant clones, WH1 (lanes 2 and 6) and WH2 (lanes 3 and 7). A 974-bp NcoI/StuI fragment adjacent to whiB3 was used to probe NcoI- (lanes 2–4) and BsmBI- (lanes 6–8) digested chromosomal DNA separated on a 0.8% agarose gel. Lanes 1 and 5 contain a 1-kb DNA ladder (New England Biolabs). (B) Southern blot analysis of wt M. bovis ATCC35723 (lane 1), an M. bovis hygromycin-resistant clone (lane 2), and marker DNA (lane 3). Chromosomal DNA in lanes 1 and 2 were digested with BsmB1. The marker DNA corresponds to a DNA fragment size of 1,650 bp.

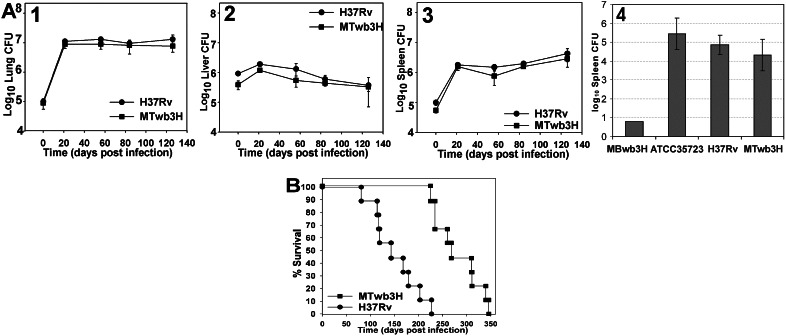

In Vivo Replication of H37Rv and M. bovis wt and whiB3 Mutant Strains.

Taking into consideration that several WhiB3 orthologues present in Streptomyces coelicolor are required for sporulation, we hypothesized that whiB3 might play a distinct role in the persistent phase of mycobacterial infection. Therefore, we assessed the in vivo growth characteristics of MTwb3H and MBwb3H in mice and guinea pigs. Fig. 4A (1–3) shows that the bacterial organ burdens (cfu) in the mice infected with MTwb3H and the parental strain H37Rv were identical throughout a 126-day period, showing no indication that MTwb3H is compromised for growth in the lungs, livers, or spleens of C57BL/6 mice. With respect to in vivo replication and organ burden, similar results were obtained in BALB/cJ infected mice (results not shown). Likewise, in guinea pigs, MTwb3H replicated as well as wt H37Rv, giving rise to comparable splenic bacterial burdens 9 weeks after s.c. inoculation (Fig. 4A 4). In striking contrast to the M. tuberculosis whiB3 mutant, MBwb3H was severely attenuated for growth in guinea pigs, showing a bacterial burden ≈5 logs lower than the parental M. bovis strain. We conclude that in H37Rv, whiB3 is dispensable for growth in both mice and guinea pigs. However, in M. bovis, the whiB3 mutation renders the bacilli incapable of either in vivo colonization or dissemination from the site of inoculation in guinea pigs.

Figure 4.

Disruption of H37Rv whiB3 does not affect organ burden during the acute and persistent phases of infection in mice and guinea pigs, whereas M. bovis whiB3 is required for in vivo growth in guinea pigs. (A) Bacterial burden in the lung (1), liver (2), and spleen (3) of C57BL/6 mice intravenously infected with 106 cfu of H37Rv and MTwb3H. Bacterial burdens in the spleens of guinea pigs (six per group) infected with H37Rv, MTwb3H, M. bovis ATCC35723, and MBwb3H (4). The results for each time point are the means and SDs of four mice per experimental group. Guinea pigs were killed 3 weeks after infection. (B) Disruption of H37Rv whiB3 significantly prolongs host survival. C57BL/6 mice (9–10 per group) were infected intravenously with 106 cfu of the indicated strain.

Survival of Mice Infected with H37Rv and whiB3 Mutant Strains.

The biological effect of the H37Rv whiB3 mutation on virulence was further investigated in mice by analysis of mean survival time (MST) after infection. The results in Fig. 4B show that survival of C57BL6 mice infected with H37Rv (MST 150 ± 48 days) and MTwb3H (MST 280 ± 48 days) were significantly different (P < 0.0001), reflecting a nearly 2-fold difference in survival. In fact, the first death (day 225) of an MTwb3H-infected mouse preceded by only 2 days the last death of an H37Rv-infected mouse (day 227). Once again, infection of BALB/c mice showed essentially identical results in which MTwb3H-infected mice survived significantly longer (P < 0.0001) than wt H37Rv-infected mice (results not shown). We conclude that a mutation in M. tuberculosis whiB3 significantly enhances survival of immunocompetent mice.

Pathological Changes in Target Organs.

There were no apparent observable differences in the liver or splenic pathology of wt H37Rv- and MTwb3H mutant-infected mice (data not shown). Such was not the case in the lungs. Despite the fact that both groups of animals developed alveolar consolidation characterized by the presence of hyperplastic alveolar macrophages and a reduction in alveolar space, the extent was markedly different between the two groups. The pathological changes were most severe in the wt infected mice. At 126 days after infection, the preponderance of lung tissue in the H37Rv-infected mice (Fig. 5A) was adversely affected, whereas the majority of the lung in the whiB3 mutant-infected mice appeared unaffected (Fig. 5B), despite the fact that both groups of animals harbored identical bacilli burdens. It is possible that the more severe pulmonary pathological changes in H37Rv-infected mice accounted for the fact that approximately 50% of them had succumbed to the infection by this time.

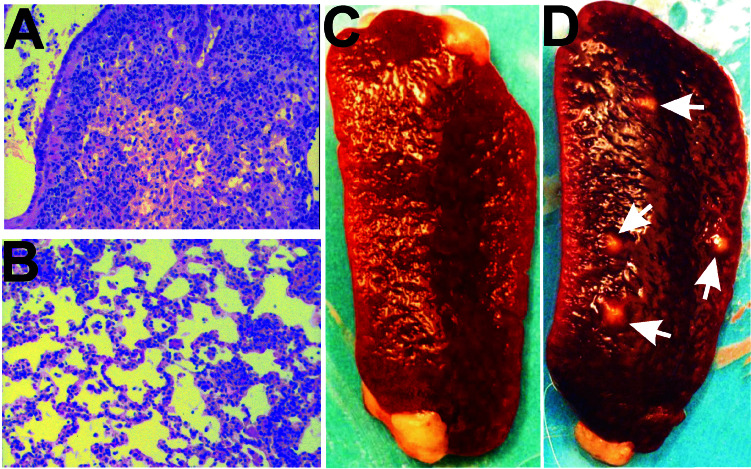

Figure 5.

Cellular infiltration in the lungs of H37Rv- (A) and MTwb3H- (B) infected C57BL/6 mice. Mice were infected with 106 cfu H37Rv or MTwb3H cells, and organs were harvested at day 126, fixed in formalin, embedded and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Magnification 100×. Spleens from guinea pigs infected with MBwb3H (C) and M. bovis ATCC35723 (D). Note the presence of multiple lesions (arrows) in the M. bovis ATCC35723-infected spleen.

Similar to previous findings with the RpoV mutant, the spleens of guinea pigs infected with MBwb3H showed no visible lesions, as expected (Fig. 5C), whereas several large lesions were observed in the spleens of guinea pigs infected with M. bovis ATCC35723 (Fig. 5D).

Discussion

In the postgenomic era, new approaches are being used to study the mechanisms of bacterial pathogenesis with the ultimate goal of understanding the function of every gene. Using the yeast two-hybrid system to study mycobacterial protein–protein interactions in yeast enabled us to convert raw genomic sequence data into functional information. We screened for proteins that interacted with the C-terminal region of RpoV, the principal sigma factor of H37Rv, and the first gene in the M. tuberculosis complex shown to be required for full virulence. We identified a protein, WhiB3, that specifically interacts with RpoV of H37Rv, and we demonstrated that the interaction of WhiB3 with mutated RpoV (Arg-515→His) is severely affected. We disrupted the whiB3 loci in both H37Rv and a virulent strain of M. bovis and studied these strains in guinea pigs and mice. Our results showed that the H37Rv whiB3 mutant behaved identically to the parental strain with respect to replication in host tissues in both guinea pigs and immunocompetent mice. In contrast, the M. bovis whiB3 mutant was severely attenuated for growth in guinea pigs. A striking finding was that disruption of H37Rv whiB3 significantly prolonged survival of immunocompetent mice, despite wild-type levels of bacteria in all organs. These findings define a previously uncharacterized virulence pathway in M. tuberculosis.

The present results strongly support a model in which the activation of a yet-to-be-identified virulence gene(s) requires an interaction between WhiB3 and the C terminus of RpoV, in which Arg-515 plays a critical role. The interaction of WhiB3 with RpoV191 is slightly weaker when compared with RpoV54 and is consistent with recent yeast two-hybrid data (24) showing increased binding of a small anti-sigma factor AsiA to truncated E. coli RpoD when compared with full-length RpoD. This finding suggests that the N-terminal domain of RpoV may shield the WhiB3 binding site in the 4.2 region and, therefore, would explain the stronger interaction of WhiB3 with RpoV54 than with RpoV191.

The existence of seven members of the WhiB family in MTB (23) and the fact that H37Rv WhiB orthologues are involved in sporulation in Streptomyces raise the intriguing question whether MTB induces a developmental switch to enter a “spore-like” state during persistence. With this question in mind, a recent report (25) demonstrated that the H37Rv whiB2 homologue in M. smegmatis, whmD, is important for septation and cell division, whereas disruption of M. smegmatis whiB3 did not affect growth or dormancy response (26). H37Rv whiB3 was shown to be constitutively expressed in M. tuberculosis H37Ra (27). H37Rv WhiB3 is homologous to the two Streptomyces proteins WhiD and WhiB, and deletion mutants of whiB and whiD (28) were shown to critically influence sporulation, septation, and spore cell-wall deposition in S. coelicolor.

Importantly, studies performed in S. coelicolor showed that in a whiB mutant background, transcription of a developmentally regulated gene whiE is completely blocked (29). Because whiE encodes a protein resembling the components of polyketide synthases (29), it is attractive to speculate that H37Rv WhiB3 regulates one or more of the 39 genes involved in polyketide metabolism (30). A recent report demonstrating a role for a mycobacterial polyketide in pathogenesis (31) coupled with the well known immunomodulatory role of polyketide immunosuppressants such as rapamycin and FK506 produced by Streptomyces hygroscopicus point toward a potential role of these molecules in modulating the host immune system.

Contrasting the results obtained from two different animal models and comparing bacterial organ burden with survival highlights a most interesting and unexpected difference between M. bovis and H37Rv whiB3 mutant strains. For example, s.c.-administered mutant MBwb3H is incapable of colonizing the spleen of guinea pigs, a result closely resembling that originally reported for the attenuated strain (16). In contrast, the bacterial burden in the spleens of guinea pigs s.c.-infected with MTwb3H and H37Rv were essentially identical, fully consistent with our data in the murine system. This dramatic difference in the effect of whiB3 upon the virulence of two M. tuberculosis complex members reveals a major dissimilarity between virulent M. bovis and H37Rv, a contrast that became apparent only by the use of multiple animal model systems. The difference in in vivo growth in guinea pigs likely mirrors fundamental genetic differences that exist between H37Rv and M. bovis. The identification of 61 ORFs in nine regions present in H37Rv and absent in several M. bovis strains (32) is consistent with this notion. Although the pulmonary disease caused by M. bovis and MTB in humans is clinically and pathologically indistinguishable (33), only the M. bovis whiB3 mutant is incapacitated with respect to in vivo growth in guinea pigs. This discovery points to the importance of a gene(s) regulated by WhiB3 that is essential for in vivo survival or replication or dissemination from the site of inoculation in guinea pigs. The identical bacterial burden in the organs of mice and guinea pigs infected with MTwb3H suggests that in H37Rv, whiB3 does not affect organ colonization in either animal species.

Strikingly, mice infected with MTwb3H showed a highly significant difference in host survival as compared with the wt infected mice. According to our knowledge, all attenuated MTB mutant strains to date can be categorized in one of two classes, showing either an immediate (5–8, 10, 12, 34–36) or delayed (9, 11) decrease of cfu in the organs of infected immunocompetent mice. The M. tuberculosis whiB3 mutant represents a third category, showing prolonged host survival despite wild-type growth and organ burden, hence showing significant attenuation for virulence and not growth. One explanation might be that proteinaceous (e.g., secreted proteins) or nonproteinaceous factors (e.g., polyketides) regulated by WhiB3 alter the ability of the infected cells to induce an ultimately harmful inflammatory response. An analogous explanation was suggested when several strains of MTB and M. bovis were studied with respect to growth rate, organ burden, and host survival (37, 38). Interestingly, despite identical organ burden, M. bovis Ravenel was shown to be considerably more virulent in mice when compared with H37Rv and CDC1551 (38).

It is known that when MTB are inhaled into the lungs, macrophages secrete numerous cytokines including IL-1, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), and transforming growth factor (TGF)-β, all possessing the potential to exert powerful immunoregulatory effects that mediate clinical manifestations of disease: i.e., tissue necrosis, fibrosis, fever, and wasting (39). Perhaps to reduce acute inflammation and tissue damage, immunosuppressive cytokines such as IL-10 and TGF-β are produced at the site of infection. Thus, in light of previous studies addressing the relationship between organ burden and host survival (37, 38), a reasonable explanation might be that WhiB3 regulates specific mycobacterial factors that modulate the kinetics and balance between proinflammatory and inhibitory cytokines to diminish host survival. Alternatively, specific mycobacterial factors regulated by WhiB3 might be directly involved in causing specific pathological damage, which eventually results in host death. Therefore, we would categorize the H37Rv whiB3 deletion strain as an increased host survival mutant, or an isurv.

In conclusion, through protein–protein communication and gene-disruption experiments, this study has provided fundamental insights into the biological role of a member of the WhiB family. To our knowledge, we describe the first MTB mutant in virulence that significantly prolongs host survival despite wild-type levels of viable bacilli. In addition, the present results are a description of a mutation that is attenuating for growth (in guinea pigs) in M. bovis but not in MTB, revealing a fundamental biological difference stemming from the small degree of genetic dissimilarity between these species.

Although the loss of whiB3 does not prevent a lethal infection in mice, death is significantly delayed. Importantly, our results caution against interpreting in vivo virulence experiments solely upon a single criterion such as organ colonization or survival studies. We believe our findings will contribute to the identification of mycobacterial genes involved in the production of virulence factors that modulate the immune system, which may aid in the future development of new vaccines against tuberculosis.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Ilona Breiterena, Gabriel Chan, Joe Ashour, and Geoffrey de Lisle for assistance with animal experiments, Henry Warren for the histopathological examination of infected tissue, and Joan Joseph for help in screening the yeast two-hybrid library. This work was supported by National Institute of Health Grants AI-07118, AI-23545, and the New Zealand Foundation for Research Science and Technology.

Abbreviations

- MTB

Mycobacterium tuberculosis

- H37Rv

M. tuberculosis H37Rv

- wt

wild type

- GST

glutathione S-transferase

- cfu

colony-forming unit

- IMAC-3

immobilized metal affinity capture

- SC

synthetic complete

- BD

binding domain

- AD

activation domain

References

- 1.Dye C, Scheele S, Dolin P, Pathania V, Raviglione M C. J Am Med Assoc. 1999;282:677–686. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.7.677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fine P E. Lancet. 1995;346:1339–1345. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)92348-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Steyn A J C, Chan J, Mehra V. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 1999;12:415–424. doi: 10.1097/00001432-199910000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Glickman M S, Jacobs W R., Jr Cell. 2001;104:477–485. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00236-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berthet F X, Lagranderie M, Gounon P, Laurent-Winter C, Ensergueix D, Chavarot P, Thouron F, Maranghi E, Pelicic V, Portnoi D, et al. Science. 1998;282:759–762. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5389.759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buchmeier N, Blanc-Potard A, Ehrt S, Piddington D, Riley L, Groisman E A. Mol Microbiol. 2000;35:1375–1382. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01797.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cox J S, Chen B, McNeil M, Jacobs W R., Jr Nature (London) 1999;402:79–83. doi: 10.1038/47042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dubnau E, Chan J, Raynaud C, Mohan V P, Laneelle M A, Yu K, Quemard A, Smith I, Daffe M. Mol Microbiol. 2000;36:630–637. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01882.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Glickman M S, Cox J S, Jacobs W R., Jr Mol Cell. 2000;5:717–727. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80250-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hondalus M K, Bardarov S, Russell R, Chan J, Jacobs W R, Jr, Bloom B R. Infect Immun. 2000;68:2888–2898. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.5.2888-2898.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McKinney J D, Honer zu Bentrup K, Munoz-Elias E J, Miczak A, Chen B, Chan W T, Swenson D, Sacchettini J C, Jacobs W R, Jr, Russell D G. Nature (London) 2000;406:735–738. doi: 10.1038/35021074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Perez E, Samper S, Bordas Y, Guilhot C, Gicquel B, Martin C. Mol Microbiol. 2001;41:179–187. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02500.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lonetto M, Gribskov M, Gross C A. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:3843–3849. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.12.3843-3849.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lonetto M A, Rhodius V, Lamberg K, Kiley P, Busby S, Gross C. J Mol Biol. 1998;284:1353–1365. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rhodius V A, Busby S J. J Mol Biol. 2000;299:311–324. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Collins D M, Kawakami R P, de Lisle G W, Pascopella L, Bloom B R, Jacobs W R., Jr Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:8036–8040. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.17.8036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gomez J E, Chen J M, Bishai W R. Tuber Lung Dis. 1997;78:175–183. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8479(97)90024-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gomez M, Doukhan L, Nair G, Smith I. Mol Microbiol. 1998;29:617–628. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00960.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wards B J, Collins D M. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1996;145:101–105. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1996.tb08563.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bardarov S, Kriakov J, Carriere C, Yu S, Vaamonde C, McAdam R A, Bloom B R, Hatfull G F, Jacobs W R., Jr Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:10961–10966. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.20.10961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wards B J, de Lisle G W, Collins D M. Tuber Lung Dis. 2000;80:185–189. doi: 10.1054/tuld.2000.0244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Qin L, Dutta R, Kurokawa H, Ikura M, Inouye M. Mol Microbiol. 2000;36:24–32. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01837.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Soliveri J A, Gomez J, Bishai W R, Chater K F. Microbiology. 2000;146:333–343. doi: 10.1099/00221287-146-2-333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sharma U K, Ravishankar S, Shandil R K, Praveen P V, Balganesh T S. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:5855–5859. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.18.5855-5859.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gomez J E, Bishai W R. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:8554–8559. doi: 10.1073/pnas.140225297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hutter B, Dick T. Res Microbiol. 1999;150:295–301. doi: 10.1016/s0923-2508(99)80055-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mulder N J, Zappe H, Steyn L M. Tuber Lung Dis. 1999;79:299–308. doi: 10.1054/tuld.1999.0217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Molle V, Palframan W J, Findlay K C, Buttner M J. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:1286–1295. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.5.1286-1295.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kelemen G H, Brian P, Flardh K, Chamberlin L, Chater K F, Buttner M J. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:2515–2521. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.9.2515-2521.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Domenech P, Barry C E, 3rd, Cole S T. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2001;4:28–34. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5274(00)00160-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.George K M, Chatterjee D, Gunawardana G, Welty D, Hayman J, Lee R, Small P L. Science. 1999;283:854–857. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5403.854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Behr M A, Wilson M A, Gill W P, Salamon H, Schoolnik G K, Rane S, Small P M. Science. 1999;284:1520–1523. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5419.1520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Grange J M. Tuberculosis. 2001;81:71–77. doi: 10.1054/tube.2000.0263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Smith D A, Parish T, Stoker N G, Bancroft G J. Infect Immun. 2001;69:1142–1150. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.2.1142-1150.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jackson M, Phalen S W, Lagranderie M, Ensergueix D, Chavarot P, Marchal G, McMurray D N, Gicquel B, Guilhot C. Infect Immun. 1999;67:2867–2873. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.6.2867-2873.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zahrt T C, Deretic V. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:12706–12711. doi: 10.1073/pnas.221272198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dunn P L, North R J. Infect Immun. 1995;63:3428–3437. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.9.3428-3437.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.North R J, Ryan L, LaCource R, Mogues T, Goodrich M E. Infect Immun. 1999;67:5483–5485. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.10.5483-5485.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Barnes P F, Modlin R L, Ellner J J. In: Tuberculosis: Pathogenesis, Protection and Control. Bloom B R, editor. Washington, DC: Am. Soc. Microbiol.; 1994. pp. 417–435. [Google Scholar]