Abstract

Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) manifests as a hereditary condition that diminishes muscular strength through the progressive degeneration of structural muscle tissue, which is brought about by deficiencies in the dystrophin protein required for the integrity of muscle cells. DMD is among four different types of dystrophinopathy disorders. Current studies have established that long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) play a significant role in determining the trajectory and overall prognosis of chronic musculoskeletal conditions. LncRNAs are different in terms of their lengths, production mechanisms, and operational modes, but they do not produce proteins, as their primary activity is the regulation of gene expression. This research synthesizes current literature on the role of lncRNAs in the regulation of myogenesis with a specific focus on certain lncRNAs leading to DMD increments or suppressing muscle biological functions. LncRNAs modulate skeletal myogenesis gene expression, yet pathological lncRNA function is linked to various muscular diseases. Some lncRNAs directly control genes or indirectly control miRNAs with positive or negative effects on muscle cells or the development of DMD. The research findings have significantly advanced our knowledge about the regulatory function of lncRNAs on muscle growth and regeneration processes and DMD diseases.

Keywords: skeletal muscle, DMD, LncRNA, gene regulation

1. Introduction

Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) is an X-linked recessive muscular dystrophy caused by pathogenic variants in the dystrophin gene (DMD), affecting patients from early childhood [1]. The majority of DMD patients aged 2–3 years old have muscle breakdown that leads to progressive weakness, more prominent initially in the proximal lower limbs, that rapidly leads to wheelchair dependence by early adolescence, as described in the natural history of the disease [2,3]. Deaths among DMD patients occur between 20 and 40 years because their muscles weaken to extreme debilitation. Thus, the primary cause of death is end-stage cardiomyopathy, often complicated by superimposed respiratory infections or acute episodes [4]. Various studies and sources have different reports concerning DMD prevalence as well as its incidence at birth. Current research suggests DMD affects 0.9 to 16.8 of 100,000 males, but birth prevalence studies suggest DMD occurs 1.5 to 28.2 times in 100,000 live-born male children. The numerous scientific estimates reflect the difficulty in estimating DMD incidence in males [5].

The pathogenetic variants of the DMD gene cause progressive deterioration of the skeletal muscle, the interplay of damage resulting from disrupted muscle fibers, and severe cycles of degeneration and regeneration, leading to progressive muscle atrophy and replacement with fibrotic and adipose tissues during the disease process [6]. The myogenesis of skeletal muscle is a multi-step process with various discrete stages characterized by the co-existence of myogenic regulatory factors (MRFs), which include Myf5, myogenic differentiation antigen (MyoD), myogenin (MyoG), and Mrf-4, as well as myosin heavy chain (Mhc) [7]. From a pathogenetic perspective, dystrophin deficiency leads to progressive muscle deterioration, inflammation, and pro-oxidative/mitochondrial stress [8,9]

LncRNA has now been acknowledged as a crucial factor directly interacting with multiple myogenic regulatory factors. The long non-coding RNA class comprises non-coding RNA species that exceed 200 nucleotides in length [4,10,11]. These RNA species play imperative roles by modulating gene expression at transcriptional and post-transcriptional levels [12,13]. LncRNAs differ from mRNAs as they do not have an open reading frame (ORF), having around 2.8 exons, whereas proprotein-coding RNA has 11 exons and low abundance [14]. LncRNAs can indirectly regulate gene expression in three ways: direct activation of transcription factors, miRNA sponge, enzymatic recruitment to genomic loci, and sequence changes [15,16]. Research has shown that some non-coding RNAs control muscle growth and development, albeit their genetic analysis boundaries are poorly understood [17,18].

Due to their underuse in genetic analysis, these RNAs have not received much focus in genetic research on muscle development. The Pathways Studio Software Web Mammalian (V. 12.5.0.2, 2022) was used to filter out matching lncRNAs that potentially influence the development of DMD and their miRNA binding and genetic motifs, and available literature on DMD and lncRNA, for the current review. LncRNA is encoded by more than 56,946 genes (127,802 transcripts) but has little or no potential to produce protein [19]. In addition, lncRNAs are transcribed into some peptides with regulatory functions [20].

Based on high-throughput technologies and bioinformatics analyses, thousands of lncRNAs have been discovered in skeletal muscles, but only a few have been identified as functionally regulated (Table 1). Hou et al. examined the skeletal muscle transcriptome, detecting 322 lncRNAs. The identified lncRNAs regulate the gene function of Csrp3, Myf6, Igfbp, Dcn, Map2k1, Spp1, and Acsl1, which control skeletal muscle development and fatty acid metabolism [19]. The groups of lncRNAs bind proteins to affect the development and deterioration of muscles. Metabolism-related lncRNAs: Gm15441 controls insulin signal transmission while sustaining stable blood glucose levels in skeletal muscles. Pparα activation level rises during fasting periods, leading to Gm15441 gene expression elevation through Pparα-binding sites in its promoter [21]. The protein Gm15441 forms a complex with Txnip and decreases protein amounts, which results in reduced hepatic glucose production [22]. A Spearman correlation analysis showed 3110045C21Rik and Ddr2 expression occur together in type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) patients, which indicates 3110045C21Rik regulates insulin-signaling mechanisms [23]. Fibrosis-related lncRNAs: Furthermore, the overexpression of 3110045C21Rik promotes the up-regulation of E-cadherin (Cdh1) while suppressing the expression of alpha-smooth muscle actin (Acta2) and Transforming Growth Factor Beta 1 (Tgfb1), key markers associated with the development and progression of fibrosis [24]. Myogenesis and Apoptosis-related lncRNAs: Recent literature identifies several lncRNAs related to skeletal muscle atrophy, including SYISL, Mir22hg, Myoparr, Pvt1, RP11-253E3.3, PRKG1-AS1, lncDLEU2, Chronos, lnc-ORA, lncMUMA, Atrolnc-1, H19, HOTAIR, Malat1, PVT1, Gm15441, 3110045C21Rik, Gm20743, LncEDCH1, ZFP36L2-AS, LncIRS1, SMUL, lnc-mg, and MYH1G-AS. These lncRNAs regulate key processes in muscle atrophy through diverse mechanisms, including modulation of protein synthesis, ubiquitin-proteasome-mediated protein degradation, and myogenic differentiation [25]. A Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis (WGCNA) of goat skeletal muscle in developmental stages revealed that LNC_011371 (targets 74 genes, including Mb and Clic5, that are up-regulated after birth), LNC_007561 (targets Tcf4 that regulates myogenesis), and LNC_001728 (binds to S100A4 gene and promotes cardiomyocyte production and increases myocardial cell number by inhibiting apoptosis) involve in muscle structure formation, p53-signaling pathways, and MAPK-signaling pathways [26].

Table 1.

Regulatory effects of lncRNAs on some genes related to muscle biology.

| LncRNA | Regulation | Genes | Function of lncRNA | Organism | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gm15441 | negative | Txnip | decline hepatic glucose production | Mouse | [20,22] |

| 3110045C21Rik | positive | Ddr2 | role in insulin signaling pathway regulation | Mouse | [23] |

| 3110045C21Rik | positive | Cdh1 | to be involved in fibrosis | Mouse | [24] |

| 3110045C21Rik | negative | Acta2 | to be involved in fibrosis | Mouse | [24] |

| 3110045C21Rik | negative | Tgfb1 | to be involved in fibrosis | Mouse | [24] |

| Lnc_011371 | positive | Mb, Clic5 | up-regulation after birth | Anhui white goats (AWG) | [26] |

| Lnc_007561 | positive | Tcf4 | regulates myogenesis | Anhui white goats (AWG) | [26] |

| Lnc_001728 | positive | S100 A4 | promotes cardiomyocyte production, inhibiting apoptosis | Anhui white goats (AWG) | [26] |

| Ppp1r1b | positive | Prc2 | leads to the induction of myogenic transcription factors | C2C12 and Human skeletal muscle myoblast | [27] |

| Miat | negative | Dnmt1, Dnmt3a, and Dnmt3b | silenced MIAT leads to reduced cell proliferation and promotes apoptosis | Human breast cancer | [28] |

| Lnc-1700113A16RIK | positive | Myog, MEF2D | enhance the differentiation of skeletal muscle stem cells | Mouse | [29] |

| Lnc-22988, Lnc-372289 and Lnc-482286 |

positive | Acta1, Eno3, Myl1, Myom1, Myoz1, Neb, Ryr1, and Tnnc2 | could directly or indirectly regulate muscle proliferation, differentiation, and development | Pig | [30] |

| H19 | negative | Smad1, Smad5 and Cdc6 | promotion of skeletal muscle differentiation and regeneration | C2C12 Mouse myoblast cell line | [31] |

| H19 | positive | Dusp27 | promote AMPK activity in muscle cells and stimulate glucose uptake and mitochondrial biogenesis | Mouse | [32] |

| Mar1 | positive | Myod, Myog, Mef2c, and Myf5 | positively correlated with muscle differentiation | Mouse | [33] |

| Syisl | negative | Ezh2 | regulate muscle atrophy and sarcopenia | C2C12 | [34] |

| LncMyod (Gm45923) | positive | Imp2 | promoted myoblast proliferation and inhibited myoblast differentiation in the C2C12 cell line | C2C12 | [35] |

| Dum | negative | Dppa2 | promotes myogenic differentiation | C2C12 | [36] |

| FKBP1C | negative | Myh1b | suppress myoblast proliferation and enhance myoblast differentiation in fast and slow muscle fibers. | Chicken | [37] |

2. LncRNAs in Muscle Development

The myogenic differentiation process benefits from Ppp1r1b-lncRNA positive regulatory action. The Ppp1r1b and polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2) interaction stimulates the transcription of myogenic transcription factors in a mouse C2C12 myoblast cell line and human skeletal myoblasts. The absence of Ppp1r1b leads Ezh2 to enhance its binding activities on the regulatory regions of these myogenic transcription factors. The suppression of MyoD, Myogenin, and Tbx5, along with sarcomere proteins, becomes very evident. The research indicates that Ppp1r1b functions as a regulatory factor during the early stages of muscle development and heart formation [27]. One of the essential lncRNAs that regulates some transcription factors and miRNAs is the myocardial infarction-associated transcript (Miat). This lncRNA can indirectly regulate some biological processes in muscle, such as cell proliferation, cell differentiation, regeneration, and myogenesis. For instance, Miat upregulates the expression of the transcription factor Foxo1 by sponging miR-139-5p [38], and this gene regulates myogenic differentiation and growth, muscle atrophy, and glycemic properties [39,40]. Moreover, Miat indirectly regulates the expression of Zeb1 by acting as a sponge and repressing miR-150. Expression of Zeb1 has been reported in numerous tissues, including the immune system, and significantly regulates muscle and lymphoid differentiation [41]. Notably, both Zeb1 and Zeb2 are pivotal elements that modulate the TGF-β-mediated signaling pathway through their interaction with Smad proteins to facilitate the recruitment of co-activators or co-repressors [42]. Current studies demonstrate that Miat operates directly to control three transcription factors named Dnmt1, Dnmt3a, and Dnmt3b. Research findings indicate that decreasing Miat levels limits attachment to these transcription factors [28]. Phytohemagglutinin stimulation increased apoptosis and inhibited cell proliferation in response to suppression of the Dnmt1 protein. Evidence shows that the gene modifier exerts substantial control over essential biological operations within immune cells [43]. A feedback loop between Dnmt3b and miR-125b controls vascular smooth muscle cell responses to homocysteine exposure [44]. Studies demonstrate that MyoG attaches to the promoter of this lncRNA to cause its expression activation. It was also shown that enhanced lncRNA-1700113A16RIK expression accelerates the differentiation process of MuSC cells, while decreased expression adversely affects the function of cells. Moreover, this lncRNA directly interacts with the 3′UTR of myogenic genes, including the myogenic transcription factor Mef2d, subsequently enhancing its translation [29].

Investigations into lncRNA expression patterns during skeletal muscle development identified ten lncRNAs, which displayed maximal correlations with known protein-coding genes. Hub lncRNAs consisting of lnc-22988, lnc-372289, and lnc-482286 exhibited positive correlation while connecting with 156 protein-coding genes, including the crucial skeletal muscle developmental genes Acta1, Eno3, Myl1, Myom1, Myoz1, Neb, Ryr1, and Tnnc2. The three lncRNAs are linked to various genetic elements that potentially control muscle proliferation and differentiation and global developmental pathways [30]. The expression of miR-675-3p and miR-675-5p increases due to H19 regulation in skeletal muscle cells, and these miRNAs reduce Smad1, Smad5, and Cdc6 gene activity to drive both skeletal muscle differentiation and regeneration [31]. Moreover, an increase in H19 results in the higher expression of dual-specificity phosphatase 27 (Dusp27) at the posttranscriptional level, promotes AMPK pathway activity in muscle cells, and stimulates glucose uptake and mitochondrial biogenesis. The decline of this lncRNA expression in human and mouse muscles leads to muscle insulin resistance, while high concentrations of H19 can enhance muscle insulin sensitivity [32]. In the embryonic stage, lncRNAs such as H19, Alien, and Miat are identified to have a key regulatory function. However, in cardiac development, their role is unclear, and H19 displays a dynamic epicardial, myocardial, and endocardial expression during cardiac development [45].

Several lines of evidence demonstrate that Chronos plays a pivotal role in hypertrophy. Using inducible Akt1 transgenic mice to investigate age-related lncRNAs revealed that Chronos inhibits Akt1 and hypertrophic growth. Studies in vivo and in vitro show that Chronos inhibition’s effect on the Bmp-signaling pathway in general [46] and the Bmp7 ligand specifically [47], leading to increased myofiber hypertrophy [48]. Furthermore, the Bmp gene is essential for developing blood vessels required for steady muscle states [49].

3. LncRNA and miRNA—Working Together in Muscles

Skeletal muscle formation depends on lncRNAs and miRNAs, which operate within a complex regulatory system to control myogenesis. They regulate chromatin, activate transcription, act as miRNAs sponges, modulate RNA stability and translation, and, in some cases, encode micropeptides. MiRNAs regulate myogenic gene expression precisely, while lncRNAs, often functioning as sponges, modulate miRNA activity to fine-tune proliferation, differentiation, and regeneration. This coordinated regulation is critical for muscle development and holds promise for diagnosing and treating muscle diseases, such as muscular dystrophies [50]. A direct relationship exists between lncRNA and miRNA expression patterns, combining regulatory mechanisms across biological operations. The lncMgpf functions as an example by influencing the expression level of miR-135a-5p. Through this interaction, lncMgpf weakens the inhibitory effects of miR-135a-5p, consequently elevating the expression of Mef2c. This action further increases human antigen R (HuR)-mediated mRNA and regulates muscle development genes like MyoD and MyoG [51]. Another study shows that AK003290 in mice and its homologous lncRNA AK394747 in pigs and MT510647 in humans positively regulate MyoD expression and enhance myogenic differentiation of muscle cells [5]. During muscle differentiation in C2C12 cells, miR-487b regulates Wnt5a, a key player in myogenesis, and promotes muscle differentiation and regeneration. A study on lncRNA shows that muscle anabolic regulator 1 (MAR1) may regulate miR-487b and positively correlate with muscle differentiation. In addition, this lncRNA significantly enhanced mRNA and protein levels of myogenic markers (MyoD, MyoG, Mef2c, and Myf5), with highly expressed formation of myotubes in mouse skeletal muscle [33]. Moreover, overexpression of the intronic sense-overlapping lncRNA known as Syisl adversely affects the differentiation process of C2C12 cells. Elevated Syisl expression delays cellular differentiation while promoting cell proliferation [52]. Also, Syisl homologs in humans (designated hSyisl) and pigs (designated pSyisl) regulate myogenesis through interactions with Ezh2 and regulate muscle atrophy and sarcopenia [34].

3.1. Cell Cycle and Differentiation Regulators

Specific lncRNAs function during the regulation of multiple myogenesis steps, and their depletion or dysregulation impairs cellular capacity to achieve cell cycle exit, resulting in aberrant proliferation. LncMyoD (Gm45923) is a regulatory lncRNA that binds directly to Igf2-mRNA-binding protein 2 (IMP2) during myoblast differentiation, downregulating the IMP2-mediated translation of proliferation-associated genes like N-Ras and c-Myc [53]. Meanwhile, miR-370-3p, which is directly targeted by lncMyoD, promotes myoblast proliferation and hinders myogenic differentiation of the C2C12 cell line [35]. Another lncRNA, Dum, follows the path of myoblast differentiation when stimulated by MyoD. Silencing Dppa2 and suppressing the MyoD–Dum–Dppa2 complex formation further augments myoblast differentiation and damage-induced muscle regeneration. A Dum knockdown could affect satellite cell activation, proliferation, or self-renewal capacity [36]. Furthermore, a network analysis of lncRNA-miRNA-gene interactions related to myogenesis led to the identification of lncIrs1, which regulates myoblast proliferation and differentiation [54]. LncRNA-Irs1 influences Irs1 expression downstream of the Igf1-receptor-signaling pathway. Elevating lncIrs1 expression in breast muscle mitigates muscle atrophy and enhances muscle weight. Its overexpression boosts the phosphorylation of AKT within the IGF-1 pathway [52].

3.2. Atrophy Regulators

Research on lncRNA FKBP1C has shown that it is a developmental regulator of skeletal muscle tissue that prevents myoblast replication while supporting differentiation, mostly in fast and slow muscle fibers. Research on the Myh1b gene silencing primarily showed effects in fast muscle fibers. The lncRNA enhances Myh1b expression through cis-regulation, promoting protein stability, and influencing myoblast development [37]. The co-expression network analysis highlighted three important lncRNAs linked to skeletal muscle and atrophy, which are Ac004797.1, Prkg1-As1, and Grpc5d-As1. Research results demonstrated that the knockdown of Prkg1-As1 increased MyoD, MyoG, and Mef2c gene expression while reducing apoptosis in myoblast cells and the mortality rate [55].

The decoy activity of lncRNAs results in miRNA sequestration, which blocks their interaction with target mRNAs and disrupts miRNA-mRNA communication networks [47,56]. MiR-127 interferes with the retrotransposon-like one protein (Rtl1) sense transcript, reducing Rtl1 protein production. The protein is essential throughout muscle regeneration and present within regenerating and dystrophic muscle tissue [57]. Another research, by Liu et al. (2020), demonstrates that miR-324 limits C2C12 myoblast differentiation while accelerating intramuscular lipid accumulation through regulation by the lncRNAs Dum and Pm20d1 [58]. Moreover, it was shown that lncRNA-Miat functions as a direct target of miR-214, demonstrating that inhibition of this miRNA restores hepatocellular carcinoma cell proliferation and invasion by counteracting the suppression of Miat expression levels [59].

4. LncRNA in DMD Disease

Atypical expression of lncRNAs is linked to diverse muscular disorders, most notably DMD, as outlined in Table 2. Current investigations have revealed that lncRNAs can regulate gene expression and translation, significantly influencing the progression of pathological states during cellular and muscular differentiation and development. Alterations in the expression of some lncRNAs are evident in the skeletal muscles of DMD patients (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Interactions of lncRNAs and miRNAs in the context of DMD (Pathway Studio Mammalian Web). Blue markers indicate lncRNAs that, together with miRNAs, are involved in interactions with disease-related genes.

Bovolenta et al. (2012) extensively investigated the DMD gene to elucidate how lncRNAs regulate gene expression and how nuclear lncRNAs modulate promoter regions to control muscle-specific isoform expression. Most regulatory lncRNA elements are found in intronic regions and nuclear spaces [60]. A detailed study based on bioinformatics identified Xist, Al132709, Linc00310, and Aldh1l1-As2 as key lncRNA regulators of DMD secondary processes, such as muscle degeneration and fibrosis. The diverse biological functions of these lncRNAs entail tumor-promoting capacity and ventricular septum development [61]. Dystrophin stabilizes the sarcolemma and is a scaffold for various intracellular signaling pathways, including nitric oxide synthase (NOS) signaling and the PI3K/Akt pathway [62]. LncRNAs, such as H19 and Malat1, are implicated in modulating these pathways. For instance, H19 can promote Akt1 expression, potentially counteracting muscle atrophy in dystrophic muscles, while lnc-31 influences myoblast differentiation by regulating myogenic gene expression [60,63]. These lncRNAs may act as upstream regulators or downstream effectors of dystrophin-dependent signaling, indicating a complex interplay that could amplify or mitigate the signaling defects caused by dystrophin deficiency [64].

Table 2.

Control of select genes through lncRNA modulation.

| LncRNA | Chr Location | Effect on Genes | Genes | Chr Location | References | DMD Effect on Gene | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meg3 | 14 | positive | Igf1 | 12 | [65] | positive | [66] |

| Meg3 | 14 | negative | Akt1 | 14 | [67] | positive | [68] |

| Meg3 | 14 | negative | Il6 | 7 | [69] | positive | [70] |

| Meg3 | 14 | negative | Mmp9 | 20 | [71] | positive | [72] |

| Meg3 | 14 | negative | Tgfb1 | 19 | [73] | positive | [74] |

| Meg3 | 14 | negative | Vegfa | 6 | [75] | positive | [76] |

| Meg3 | 14 | positive | Casp3 | 4 | [77] | - | - |

| Meg3 | 14 | positive | Casp9 | 1 | [78] | positive | [79] |

| Meg3 | 14 | positive | Foxo1 | 13 | [80] | - | - |

| Meg3 | 14 | positive | Mmp2 | 16 | [81] | positive | [82] |

| Meg3 | 14 | positive | Pten | 10 | [83] | positive | [84] |

| Neat1 | 11 | negative | Akt1 | 14 | [85] | positive | [68] |

| Neat1 | 11 | negative | Casp9 | 1 | [86] | positive | [79] |

| Neat1 | 11 | positive | Acta2 | 10 | [87] | positive | [88] |

| Neat1 | 11 | positive | Casp3 | 4 | [89] | - | - |

| Neat1 | 11 | positive | Foxo1 | 13 | [90] | - | - |

| Neat1 | 11 | positive | Il6 | 7 | [91] | positive | [70] |

| Neat1 | 11 | positive | Pycard | 16 | [92] | - | - |

| Neat1 | 11 | positive | Tgfb1 | 19 | [93] | positive | [74] |

| Xist | X | positive | Pten | 10 | [94] | positive | [84] |

| Xist | X | positive | Tgfb1 | 19 | [95] | positive | [74] |

| Xist | X | negative | Tgfb2 | 19 | [96] | positive | [97] |

| Malat1 | 11 | positive | Aqp4 | 18 | [98] | negative | [99] |

| Malat1 | 11 | negative | Mmp2 | 16 | [100] | positive | [82] |

| Malat1 | 11 | positive | Akt1 | 14 | [101] | positive | [68] |

| Malat1 | 11 | positive | Mmp9 | 20 | [102] | positive | [72] |

| Malat1 | 11 | positive | Nos3 | 7 | [103] | positive | [104] |

| Malat1 | 11 | positive | Parp1 | 1 | [105] | positive | [106] |

| Lnc31 | 9 | negative | Gsk3b | 3 | [107] | positive | [108] |

| Lnc31 | 9 | positive | Pten | 10 | [109] | positive | [84] |

| H19 | 11 | positive | Igf1 | 12 | [110] | positive | [66] |

| H19 | 11 | positive | Akt1 | 14 | [111] | positive | [68] |

| H19 | 11 | positive | Il6 | 7 | [112] | positive | [70] |

| H19 | 11 | positive | Vegfa | 6 | [113] | positive | [76] |

| Meg8 | 14 | positive | Jag1 | 20 | [114] | negative | [115] |

| Meg8 | 14 | positive | Vegfa | 6 | [116] | positive | [76] |

| Dbet | 4 | positive | Ash1l | 1 | [117] | negative | [118] |

For DMD research, a continued examination of lncRNAs occurred in the C2C12 cell line and human myoblasts. The study showed that lnc-31 exists at higher levels in DMD patient subjects than in individuals without DMD. The nuclear-based precursor molecule that produces miR-31 also creates the significant factor lnc-31, which guides the differentiation of precursor myoblasts. When lnc-31 is absent, the elevated expression of myogenin along with Atp2a1 causes rapid myogenic differentiation, which becomes difficult to reverse. This implies that lnc-31 is critical in controlling the transition from cell-cycle exit to terminal differentiation [119]. Another notable lncRNA in skeletal muscle regeneration and dystrophic muscles resides in the gene’s intron 44 (lncRNA44s2). This lncRNA exhibits expression during myogenesis in primary human myoblasts. It demonstrates activity linked to myogenesis, indicating its possible role in muscle differentiation and its potential as a disease-progression biomarker [63].

It is interesting to note that specific lncRNAs impact the progression of skeletal muscle atrophy. Physiological studies on different muscle atrophy models show depressed levels of lncMaat. Restoring or increasing lncMaat expression might then counteract multiple forms of atrophy. LncMaat inhibits miR-29b transcription through Sox6 and simultaneously represses Mbnl1 expression from the same regulatory module, leading to muscle atrophy regardless of miR-29b activity. Mbnl1 overexpression shows excellent potential for preventing muscle atrophy [120]. The literature data show that Long Intergenic Non-Protein Coding RNA, Muscle Differentiation 1 (LincMD1), becomes vital in understanding the development of DMD, as its expression is significantly reduced in myoblasts from DMD patients compared to healthy controls. The reduced levels of LincMD1 are connected to the delayed expression and development of Mhc and myogenin muscle-specific markers in DMD tissue. The therapeutic potential of LincMD1 is demonstrated by its ability to enhance Myog and Mef2c expression in DMD patient-derived myoblasts, promoting myogenic differentiation [121].

Scientific evidence reveals a significant relationship between serine/threonine-protein kinase MRCK alpha (Mrckα) and α-synuclein (Snca) with lncRNA-H19. When Mrckα and Snca actively bind, they displace H19 from interacting with DMD gene segments to promote better myotube development and more efficient cell fusion in skeletal muscle cells. The administration of AGR-H19-gain-of-function enhances WT mouse muscle tissue development, metabolic performance, and muscle mass increase [120]. The lncRNA H19 accelerates muscle regeneration by activating the miR-675-3p and miR-675-5p, which regulate myogenic pathways [31]. The influence of specific non-muscle-specific lncRNAs shapes muscle proliferation and differentiation processes and contributes to both normal and pathological conditions. The cellular proliferation inhibitor named maternally expressed gene 3 (Meg3) functions to regulate muscle metabolism, along with glucose tolerance functions. Limited lncRNA Meg3 activity impairs glucose tolerance and negatively affects muscle metabolism [122,123]. According to Butchart et al. (2018), the expression of the Meg3 gene remained the same between the atrophy disease model, mdx skeletal muscles, and normal C57 mouse muscle tissues [124].

Many lncRNAs work together to control Tnf gene activity, which might become a diagnostic marker for DMD [125]. Studies demonstrate elevated Tnf gene expression levels in DMD patients compared to healthy samples [9,70]. This regulation involves a spectrum of lncRNAs, including Meg3, Xist, lnc-31 (Mir31hg), Neat1, and Malat1, culminating in intricate control over this key gene’s activity (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The interaction of lncRNAs with hub genes.

A study showed that Meg3 overexpression decreased the pro-inflammatory cytokines Tnf-α, Il-6, and Il-1β levels [126]. The opposite results occur after silencing of Meg3 [127,128]. The increased expression level of Meg3 leads to diminished cell multiplication and reduced T-bet, Ifn-β, and Tnf-α levels. The reduction in these factors results in substantial increases in cell multiplication. The functions of lnc-31 and Neat1 in Tnf-α expression regulation match each other. The inhibitory action of lnc-31 on Tnf-α expression facilitates cell growth that might help reduce hypoxia-generated cell impairment. Neat1 exhibits anti-inflammatory properties that provide potential benefits against DMD inflammation when combined with associated treatments [129].

The expression profile of Tnf-α can be changed by several lncRNAs, such as Malat1 and Xist, because they activate the gene for Tnf-α production. Lowering of lncRNA Malat1 yields two primary effects on skeletal muscle cells. It leads to decreased Il-6, Il-8, Tnf-α serum levels, triggers cell death, and causes Akt-1 protein activation [130]. The reduction in Xist expression inhibits Tnf-α protein production and stops the Tnf-α/Rankl-signaling pathway activation process. The expression levels of Tnf-α significantly increase when Xist is overexpressed. Elevated levels of Xist following bone fractures hinder cell proliferation and differentiation, whereas reducing Xist expression promotes cell growth and regeneration [131]. The literature demonstrates that this lncRNA helps activate Pten by blocking the action of miR-17. Research has revealed that Xist silencing results in elevated levels of miR-17 in patients who experience type A aortic dissection [132]. The study of Yue et al. 2021 reported that Pten expression levels increased within the DMD and mdx mouse muscles, showing signs of muscular dystrophy. Reports indicate that Xist lncRNA indirectly supports the progression of DMD [84].

The clinical severity of DMD depends strongly on the functioning of the Tgfb1 gene. Evaluation of Tgfb1 expression enhances fibroblast multiplication and collagen synthesis while transforming fibroblasts into myofibroblasts [133]. The lncRNA molecules Neat1, Xist, and Meg3 maintain control over this gene. In molecular studies, in vitro experiments have shown that Xist can stimulate Tgfb1 expression by upregulating miR-185 [134]. Neat1 stimulates Tgfb1 overexpression through a competitive sponge action against miR-339-5p [135]. The RNA analysis demonstrates that Meg3 controls the cellular transition known as Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition (EMT) through its ability to suppress Tgfβ signaling. Interestingly, inhibiting Tgfβr1 or its downstream effectors, like RhoA, p38 MAPK, or Snai2, was proven to successfully reinstate facets of myogenic fusion and differentiation in vitro. The Meg3 functions as an inhibitor of Tgfbi or Tgfb1 expression while integrating a modification of anti-myogenic EMT-promoting factors Tgfβ, RhoA, and Snai2 in myoblasts and injured skeletal muscle [136] (Figure 2). The expression of Akt1 protein is upregulated through the regulatory actions of lncRNAs H19 and Malat1, which facilitate muscle hypertrophy in mdx mice [68].

5. How lncRNAs Can Control DMD Through miRNA and Gene Networks

Recent bioinformatics studies revealed distinct mechanisms by which Meg3 functions in its biological processes. The study shows that Meg3 functions as a miR-21-5p sponge, suggesting that this miRNA targets the 3′ untranslated region of the Pten sequence. Due to the overexpression of Meg3, Pten gene expression increases, leading to control of Pi3k/Akt signaling [137]. A third lncRNA, termed Neat1, reduces the expression levels of Akt1. The overexpressed miR-214 subsequently leads to elevated Pi3k, Akt, P-Akt, and Vegf level. The activating effect is achieved through Pten reduction. The expression of this specific lncRNA opposes the protective role of miR-214 on cerebral ischemia–reperfusion damage. By restoring Pten levels, the inhibition of Pi3k together with Akt, P-Akt, and Vegf production occurs [138].

Research indicates that serum interleukin-6 (IL-6) concentration is typically elevated in patients with DMD who are steroid-naïve or untreated compared to those treated with glucocorticoids. [139,140]. Different cell regulators, lncRNAs such as Neat1, H19, Meg3, and lnc-31, maintain control over this gene. The expression of Il-6 and Il-8 benefits from increased levels of lncRNA Neat1. This regulation is achieved by downregulating the expression of miR-181c [59], miR-139 [141], and miR-144-3p [142]. Similarly, H19 contributes to the regulation of IL-6 in a comparable manner. It promotes the expression of this gene by acting as a sponge for miR-let-7a, contributing to an increase in vascular inflammation. In contrast, Meg3 and lnc-31 exert inhibitory effects on the secretion of Tnf-α and Il-6 [127,143]. Vim represents another gene under the influence of specific lncRNAs. Some studies reveal notably elevated Vim gene expression in DMD and dystrophic hearts [144,145], but its exact function is still unclear. Xist lncRNA emerges as a potential regulator, possibly inhibiting miR-92b and freeing miR-92b from the 3′ UTR of Smad7. This process potentially triggers the activation and subsequent upregulation of Vim expression [146]. Additionally, Zhang et al. found that miR-143 and Malat1 directly regulate the Vim and epithelial–cadherin protein levels, but lower miR-143 expression combined with elevated Malat1 [147]. Conversely, higher Neat1 levels lead to an elevation of E-cadherin, Neural–cadherin protein, and Vim protein simultaneously [87]. Instead, the lncRNA H19 acts as a regulator that affects the expression of Vim, Zeb1, and Zeb2 by competing with endogenous RNAs, specifically miR-138 and miR-200a [148]. Furthermore, the overexpression of Meg3 leads to downregulation of Vim and fibronectin mesenchymal markers as it inhibits gastric cancer cell proliferation [149].

Interactions between lncRNAs and miRNAs are highly significant, as they play a crucial role in regulating gene expression. The expression of muscle-specific miRNAs regulates the modulation of muscle differentiation and homeostasis, while their patterns show changes in conditions like myocardial infarction and DMD, together with other myopathies [150,151] (Table 3, Figure 3). Cell migration and invasion are inhibited through the interaction of miRNA that simultaneously affects the gene expression of Anxa2 and Kras. The removal of miR-206 leads to worse and more rapid symptoms in mouse models of DMD [152]. Mice expressing the mature form of this miRNA demonstrate enhanced muscle tissue repair and a slower progression of Duchenne muscular dystrophy [153]. Also, the overexpression of miR-1 leads to a decrease in Malat1 expression [154]. Interestingly, miR-1 has demonstrated its potential to suppress breast cancer development by downregulating Kras and Malat1 transcription [155]. Investigations into miR-1 levels have shown significant elevation in DMD patients compared to healthy control subjects [156,157].

Table 3.

Interplay between specific lncRNAs, miRNAs, and genes in the DMD disease.

| LncRNA | Effect on Genes | miRNA | Genes | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LincMD1 | negative | miR-133A1 | Mef2c and Maml1 | [158] |

| Meg8 | negative | miR-195 | Stat6/Nf-Kβ/Il-31 | [159] |

| Malat1 | negative | miR-133A1 | Ryr2 | [44] |

| Malat1 | negative | miR-206 | Anxa2 and Kras | [160] |

| Xist | negative | miR-17 | Pten | [132] |

| Xist | negative | miR-29A | Stx17 | [122] |

| Xist | negative | miR-21 | Pc/Xist | [161] |

| Neat1 | negative | miR-34C | Cisplatin (DDP) | [162] |

| Neat1 | negative | miR-335 | Abca3 | [163] |

| Meg3 | positive | miR-133A1 | Prrt2 | [164] |

| Meg3 | negative | miR-21 | Rhob and Pten | [8] |

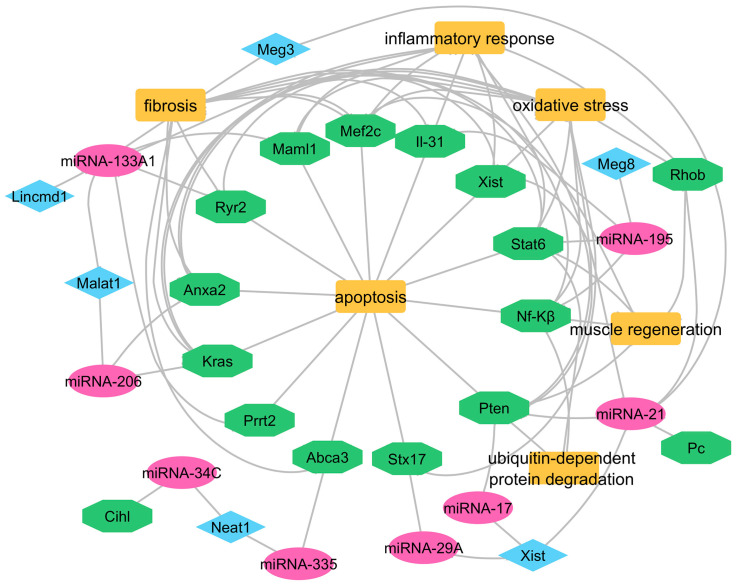

Figure 3.

A network diagram illustrating the interactions among miRNAs (pink), genes (green), and lncRNAs (blue), as well as their associations with key biological processes and pathways (orange) (Cytoscape software 3.10.3).

6. Conclusions

Recently, the importance of lncRNAs has increased because they can regulate many genes and are master regulators of various genetic, epigenetic, and biological processes essential to developing multiple disorders but are also potent regulators of muscle regeneration, affecting genes involved in DMD disease. The mechanisms of lncRNAs-mediated gene regulation discussed in this manuscript clarify that lncRNAs can regulate DMD-related gene expression at the post-transcriptional level, with a less abundant but significant role in post-translational regulation. Post-transcriptionally, lncRNAs such as Miat, H19, Meg3, and lnc-31 modulate mRNA stability, splicing, translation, and miRNA interactions (e.g., miRNA sponging, direct mRNA binding), influencing myogenic differentiation and DMD progression. Post-translationally, lncRNAs like H19 and FKBP1C regulate protein stability and signaling pathways (e.g., Akt, AMPK), highlighting their critical role in skeletal muscle development and DMD pathology. Adeno-associated virus (AAV)-mediated delivery holds promise for DMD therapy, supported by precedents in other diseases where AAV vectors delivered lncRNAs like H19 (cancer), Malat1 (vascular disease), and Neat1 (neurological disorders) to achieve therapeutic effects.

However, while the presented examples suggest potential roles for lncRNAs in DMD pathogenesis and therapeutic applications, further studies are required to establish causal relationships and validate their therapeutic potential.

Abbreviations

| DMD | Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy |

| lncRNA | Long Non-Coding RNA |

| miRNA | MicroRNA |

| MRFs | Myogenic Regulatory Factors |

| Myf5 | Myogenic Factor 5 |

| MyoD | Myogenic Differentiation Antigen |

| MyoG | Myogenin |

| Mrf4 | Myogenic Regulatory Factor 4 |

| Mhc | Myosin Heavy Chain |

| ORF | Open Reading Frame |

| T2dm | Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus |

| WGCNA | Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis |

| Prc2 | Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 |

| MuSC | Muscle Stem Cells |

| TGF-β | Transforming Growth Factor Beta |

| EMT | Epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition |

| AMPK | AMP-Activated Protein Kinase |

| Akt | Protein Kinase B |

| IGF-1 | Insulin-like Growth Factor 1 |

| Pi3k | Phosphoinositide 3-Kinase |

| P-Akt | Phosphorylated Akt |

| Vim | Vimentin |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

| IL-8 | Interleukin-8 |

| TNF-α | Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha |

| MAPK | Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase |

| Dusp27 | Dual-Specificity Phosphatase 27 |

| IMP2 | IGF2 mRNA-Binding Protein 2 |

| Mrckα | Myotonic dystrophy kinase-related Cdc42-binding kinase alpha |

| Snca | Alpha-Synuclein |

| Mbnl1 | Muscleblind-Like Splicing Regulator 1 |

| LincRNA | Long Intergenic Non-Coding RNA |

| Ryr2 | Ryanodine Receptor 2 |

| Stx17 | Syntaxin 17 |

| N-Ras | Neuroblastoma RAS Viral (v-ras) Oncogene Homolog |

| c-Myc | MYC Proto-Oncogene |

| TGFBI | Transforming Growth Factor Beta Induced |

| Prrt2 | Proline-Rich Transmembrane Protein 2 |

| ROCK1 | Rho Associated Coiled-Coil Containing Protein Kinase 1 |

| NF-κB | Nuclear Factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells |

| VEGFA | Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor A |

| SIRT1 | Sirtuin 1 |

| FOXO1 | Forkhead Box O1 |

| CXCL12 | C-X-C Motif Chemokine Ligand 12 |

| CXCR4 | C-X-C Chemokine Receptor Type 4 |

| STAT3 | Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription 3 |

| SOCS6 | Suppressor of Cytokine Signaling 6 |

| JAK2 | Janus Kinase 2 |

| MEF2C | Myocyte Enhancer Factor 2C |

| MALAT1 | Metastasis Associated Lung Adenocarcinoma Transcript 1 |

| NEAT1 | Nuclear Enriched Abundant Transcript 1 |

| MEG3/MEG8 | Maternally Expressed Gene 3/8 |

| H19 | H19 Imprinted Maternally Expressed Transcript |

| Lnc-31 | Long Non-Coding RNA 31 |

| ST2 | Suppression of Tumorigenicity 2 (biomarker) |

| EZH2 | Enhancer of Zeste Homolog 2 |

| BRCA1 | Breast Cancer 1 |

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.E.G., T.S., and Z.R.; methodology, A.E.G., T.S., Z.R., and K.A.; software, A.E.G. and T.S.; validation, T.S., Z.R., K.A., V.R., M.S., and K.H.; formal analysis, A.E.G. and T.S.; investigation, A.E.G., T.S., Z.R., K.A., V.R., M.S., and K.H.; resources, A.E.G., T.S., Z.R., and K.A.; writing—original draft preparation, A.E.G.; writing—review and editing, T.S., Z.R., K.A., V.R., M.S., and K.H.; visualization, A.E.G. and T.S.; supervision, T.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

Information on the data acquired in the project is available upon request from the corresponding author, tomasz_sadkowski@sggw.edu.pl.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding Statement

The publication was co-financed by Science development fund of the Warsaw University of Life Sciences—SGGW.

Footnotes

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

References

- 1.Ousterout D.G., Kabadi A.M., Thakore P.I., Majoros W.H., Reddy T.E., Gersbach C.A. Multiplex CRISPR/Cas9-Based Genome Editing for Correction of Dystrophin Mutations That Cause Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:6244. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Duan Y., Song B., Zheng C., Zhong Y., Guo Q., Zheng J., Yin Y., Li J., Li F. Dietary Beta-Hydroxy Beta-Methyl Butyrate Supplementation Alleviates Liver Injury in Lipopolysaccharide-Challenged Piglets. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2021;2021:e5546843. doi: 10.1155/2021/5546843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mercuri E., Bönnemann C.G., Muntoni F. Muscular Dystrophies. Lancet. 2019;394:2025–2038. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32910-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cai A., Kong X. Development of CRISPR-Mediated Systems in the Study of Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy. Hum. Gene Ther. Methods. 2019;30:71–80. doi: 10.1089/hgtb.2018.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crisafulli S., Sultana J., Fontana A., Salvo F., Messina S., Trifirò G. Global Epidemiology of Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2020;15:141. doi: 10.1186/s13023-020-01430-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dowling J.J., Weihl C.C., Spencer M.J. Molecular and Cellular Basis of Genetically Inherited Skeletal Muscle Disorders. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2021;22:713–732. doi: 10.1038/s41580-021-00389-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tajbakhsh S. Skeletal Muscle Stem Cells in Developmental versus Regenerative Myogenesis. J. Intern. Med. 2009;266:372–389. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2009.02158.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kumar S., Williams D., Sur S., Wang J.-Y., Jo H. Role of Flow-Sensitive microRNAs and Long Noncoding RNAs in Vascular Dysfunction and Atherosclerosis. Vasc. Pharmacol. 2019;114:76–92. doi: 10.1016/j.vph.2018.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rodríguez-Cruz M., Cruz-Guzmán O.D.R., Almeida-Becerril T., Solís-Serna A.D., Atilano-Miguel S., Sánchez-González J.R., Barbosa-Cortés L., Ruíz-Cruz E.D., Huicochea J.C., Cárdenas-Conejo A., et al. Potential Therapeutic Impact of Omega-3 Long Chain-Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids on Inflammation Markers in Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy: A Double-Blind, Controlled Randomized Trial. Clin. Nutr. 2018;37:1840–1851. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2017.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheng J.-T., Wang L., Wang H., Tang F.-R., Cai W.-Q., Sethi G., Xin H.-W., Ma Z. Insights into Biological Role of LncRNAs in Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition. Cells. 2019;8:1178. doi: 10.3390/cells8101178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martone J., Mariani D., Desideri F., Ballarino M. Non-Coding RNAs Shaping Muscle. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2019;7:394. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2019.00394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Esteller M. Non-Coding RNAs in Human Disease. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2011;12:861–874. doi: 10.1038/nrg3074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mattick J.S., Makunin I.V. Non-Coding RNA. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2006;15:R17–R29. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Derrien T., Johnson R., Bussotti G., Tanzer A., Djebali S., Tilgner H., Guernec G., Martin D., Merkel A., Knowles D.G. The GENCODE v7 Catalog of Human Long Noncoding RNAs: Analysis of Their Gene Structure, Evolution, and Expression. Genome Res. 2012;22:1775–1789. doi: 10.1101/gr.132159.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu W., Kuang H., Xia Y., Pope Z.C., Wang Z., Tang C., Yin D. Regular Aerobic Exercise-Ameliorated Troponin I Carbonylation to Mitigate Aged Rat Soleus Muscle Functional Recession. Exp. Physiol. 2019;104:715–728. doi: 10.1113/EP087564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chouvarine P., Photiadis J., Cesnjevar R., Scheewe J., Bauer U.M.M., Pickardt T., Kramer H.-H., Dittrich S., Berger F., Hansmann G. RNA Expression Profiles and Regulatory Networks in Human Right Ventricular Hypertrophy Due to High Pressure Load. iScience. 2021;24:102232. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2021.102232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kallen A.N., Zhou X.-B., Xu J., Qiao C., Ma J., Yan L., Lu L., Liu C., Yi J.-S., Zhang H. The Imprinted H19 lncRNA Antagonizes Let-7 microRNAs. Mol. Cell. 2013;52:101–112. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.08.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mousavi K., Zare H., Dell’Orso S., Grontved L., Gutierrez-Cruz G., Derfoul A., Hager G.L., Sartorelli V. eRNAs Promote Transcription by Establishing Chromatin Accessibility at Defined Genomic Loci. Mol. Cell. 2013;51:606–617. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.07.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Volders P.-J., Anckaert J., Verheggen K., Nuytens J., Martens L., Mestdagh P., Vandesompele J. LNCipedia 5: Towards a Reference Set of Human Long Non-Coding RNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:D135–D139. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang L., Fan J., Han L., Qi H., Wang Y., Wang H., Chen S., Du L., Li S., Zhang Y., et al. The Micropeptide LEMP Plays an Evolutionarily Conserved Role in Myogenesis. Cell Death Dis. 2020;11:357. doi: 10.1038/s41419-020-2570-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brocker C.N., Kim D., Melia T., Karri K., Velenosi T.J., Takahashi S., Aibara D., Bonzo J.A., Levi M., Waxman D.J., et al. Long Non-Coding RNA Gm15441 Attenuates Hepatic Inflammasome Activation in Response to PPARA Agonism and Fasting. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:5847. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-19554-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xin M., Guo Q., Lu Q., Lu J., Wang P.-S., Dong Y., Li T., Chen Y., Gerhard G.S., Yang X.-F., et al. Identification of Gm15441, a Txnip Antisense lncRNA, as a Critical Regulator in Liver Metabolic Homeostasis. Cell Biosci. 2021;11:208. doi: 10.1186/s13578-021-00722-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang N., Zhou Y., Yuan Q., Gao Y., Wang Y., Wang X., Cui X., Xu P., Ji C., Guo X., et al. Dynamic Transcriptome Profile in Db/Db Skeletal Muscle Reveal Critical Roles for Long Noncoding RNA Regulator. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2018;104:14–24. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2018.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arvaniti E., Moulos P., Vakrakou A., Chatziantoniou C., Chadjichristos C., Kavvadas P., Charonis A., Politis P.K. Whole-Transcriptome Analysis of UUO Mouse Model of Renal Fibrosis Reveals New Molecular Players in Kidney Diseases. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:26235. doi: 10.1038/srep26235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang Y., Wang T., Wang Z., Shi X., Jin J. Functions and Therapeutic Potentials of Long Noncoding RNA in Skeletal Muscle Atrophy and Dystrophy. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2025;16:e13747. doi: 10.1002/jcsm.13747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ling Y., Zheng Q., Sui M., Zhu L., Xu L., Zhang Y., Liu Y., Fang F., Chu M., Ma Y., et al. Comprehensive Analysis of LncRNA Reveals the Temporal-Specific Module of Goat Skeletal Muscle Development. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019;20:3950. doi: 10.3390/ijms20163950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kang X., Zhao Y., Van Arsdell G., Nelson S.F., Touma M. Ppp1r1b-lncRNA Inhibits PRC2 at Myogenic Regulatory Genes to Promote Cardiac and Skeletal Muscle Development in Mouse and Human. Rna. 2020;26:481–491. doi: 10.1261/rna.073692.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ge X., Sun T., Zhang Y., Li Y., Gao P., Zhang D., Zhang B., Wang P., Ma W., Lu S. The Role and Possible Mechanism of the Long Noncoding RNA LINC01260 in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Nutr. Metab. 2022;19:3. doi: 10.1186/s12986-021-00634-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kitamura T., Kitamura Y.I., Funahashi Y., Shawber C.J., Castrillon D.H., Kollipara R., DePinho R.A., Kitajewski J., Accili D. A Foxo/Notch Pathway Controls Myogenic Differentiation and Fiber Type Specification. J. Clin. Investig. 2007;117:2477–2485. doi: 10.1172/JCI32054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kousteni S. FoxO1, the Transcriptional Chief of Staff of Energy Metabolism. Bone. 2012;50:437–443. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2011.06.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vandewalle C., Van Roy F., Berx G. The Role of the ZEB Family of Transcription Factors in Development and Disease. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. CMLS. 2009;66:773–787. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8465-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jou M.-Y., Philipps A.F., Kelleher S.L., Lönnerdal B. Effects of Zinc Exposure on Zinc Transporter Expression in Human Intestinal Cells of Varying Maturity. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2010;50:587–595. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3181d98e85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li D., Hu X., Yu S., Deng S., Yan M., Sun F., Song J., Tang L. Silence of lncRNA MIAT-Mediated Inhibition of DLG3 Promoter Methylation Suppresses Breast Cancer Progression via the Hippo Signaling Pathway. Cell. Signal. 2020;73:109697. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2020.109697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen G., Chen H., Ren S., Xia M., Zhu J., Liu Y., Zhang L., Tang L., Sun L., Liu H., et al. Aberrant DNA Methylation of mTOR Pathway Genes Promotes Inflammatory Activation of Immune Cells in Diabetic Kidney Disease. Kidney Int. 2019;96:409–420. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2019.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang M., Wang L.I. MALAT1 Knockdown Protects from Bronchial/Tracheal Smooth Muscle Cell Injury via Regulation of microRNA-133a/Ryanodine Receptor 2 Axis. J. Biosci. 2021;46:28. doi: 10.1007/s12038-021-00149-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fu X., Li S., Jia M., Xu B., Yang L., Ma R., Cheng H., Yang W., Hu P. Myogenesis Controlled by a Long Non-Coding RNA 1700113A16RIK and Post-Transcriptional Regulation. Cell Regen. 2022;11:13. doi: 10.1186/s13619-022-00114-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gao P.F., Guo X.H., Du M., Cao G.Q., Yang Q.C., Pu Z.D., Wang Z.Y., Zhang Q., Li M., Jin Y.S., et al. LncRNA Profiling of Skeletal Muscles in Large White Pigs and Mashen Pigs during Development. J. Anim. Sci. 2017;95:4239–4250. doi: 10.2527/jas2016.1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dey B.K., Pfeifer K., Dutta A. The H19 Long Noncoding RNA Gives Rise to microRNAs miR-675-3p and miR-675-5p to Promote Skeletal Muscle Differentiation and Regeneration. Genes Dev. 2014;28:491–501. doi: 10.1101/gad.234419.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Geng T., Liu Y., Xu Y., Jiang Y., Zhang N., Wang Z., Carmichael G.G., Taylor H.S., Li D., Huang Y. H19 lncRNA Promotes Skeletal Muscle Insulin Sensitivity in Part by Targeting AMPK. Diabetes. 2018;67:2183–2198. doi: 10.2337/db18-0370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.García-Padilla C., Domínguez J.N., Aránega A.E., Franco D. Differential Chamber-Specific Expression and Regulation of Long Non-Coding RNAs during Cardiac Development. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gene Regul. Mech. 2019;1862:194435. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2019.194435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sartori R., Schirwis E., Blaauw B., Bortolanza S., Zhao J., Enzo E., Stantzou A., Mouisel E., Toniolo L., Ferry A., et al. BMP Signaling Controls Muscle Mass. Nat. Genet. 2013;45:1309–1318. doi: 10.1038/ng.2772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Winbanks C.E., Chen J.L., Qian H., Liu Y., Bernardo B.C., Beyer C., Watt K.I., Thomson R.E., Connor T., Turner B.J., et al. The Bone Morphogenetic Protein Axis Is a Positive Regulator of Skeletal Muscle Mass. J. Cell Biol. 2013;203:345–357. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201211134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Neppl R.L., Wu C.-L., Walsh K. lncRNA Chronos Is an Aging-Induced Inhibitor of Muscle Hypertrophy. J. Cell Biol. 2017;216:3497–3507. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201612100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Macpherson P.C.D., Farshi P., Goldman D. Dach2-Hdac9 Signaling Regulates Reinnervation of Muscle Endplates. Development. 2015;142:4038–4048. doi: 10.1242/dev.125674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang Z.-K., Li J., Guan D., Liang C., Zhuo Z., Liu J., Lu A., Zhang G., Zhang B.-T. A Newly Identified lncRNA MAR1 Acts as a miR-487b Sponge to Promote Skeletal Muscle Differentiation and Regeneration. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2018;9:613–626. doi: 10.1002/jcsm.12281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jin J., Du M., Wang J., Guo Y., Zhang J., Zuo H., Hou Y., Wang S., Lv W., Bai W., et al. Conservative Analysis of Synaptopodin-2 Intron Sense-Overlapping lncRNA Reveals Its Novel Function in Promoting Muscle Atrophy. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2022;13:2017–2030. doi: 10.1002/jcsm.13012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang P., Du J., Guo X., Wu S., He J., Li X., Shen L., Chen L., Li B., Zhang J., et al. LncMyoD Promotes Skeletal Myogenesis and Regulates Skeletal Muscle Fiber-Type Composition by Sponging miR-370-3p. Genes. 2021;12:589. doi: 10.3390/genes12040589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang L., Zhao Y., Bao X., Zhu X., Kwok Y.K.-Y., Sun K., Chen X., Huang Y., Jauch R., Esteban M.A., et al. LncRNA Dum Interacts with Dnmts to Regulate Dppa2 Expression during Myogenic Differentiation and Muscle Regeneration. Cell Res. 2015;25:335–350. doi: 10.1038/cr.2015.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yu J.-A., Wang Z., Yang X., Ma M., Li Z., Nie Q. LncRNA-FKBP1C Regulates Muscle Fiber Type Switching by Affecting the Stability of MYH1B. Cell Death Discov. 2021;7:73. doi: 10.1038/s41420-021-00463-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang S., Jin J., Xu Z., Zuo B. Functions and Regulatory Mechanisms of lncRNAs in Skeletal Myogenesis, Muscle Disease and Meat Production. Cells. 2019;8:1107. doi: 10.3390/cells8091107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.He L., Chen Y., Hao S., Qian J. Uncovering Novel Landscape of Cardiovascular Diseases and Therapeutic Targets for Cardioprotection via Long Noncoding RNA-miRNA-mRNA Axes. Epigenomics. 2018;10:661–671. doi: 10.2217/epi-2017-0176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jin J.J., Lv W., Xia P., Xu Z.Y., Zheng A.D., Wang X.J., Wang S.S., Zeng R., Luo H.M., Li G.L., et al. Long Noncoding RNA SYISL Regulates Myogenesis by Interacting with Polycomb Repressive Complex 2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2018;115:E9802–E9811. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1801471115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gong C., Li Z., Ramanujan K., Clay I., Zhang Y., Lemire-Brachat S., Glass D.J. A Long Non-Coding RNA, LncMyoD, Regulates Skeletal Muscle Differentiation by Blocking IMP2-Mediated mRNA Translation. Dev. Cell. 2015;34:181–191. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2015.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Li J., Yang T., Tang H., Sha Z., Chen R., Chen L., Yu Y., Rowe G.C., Das S., Xiao J. Inhibition of lncRNA MAAT Controls Multiple Types of Muscle Atrophy by Cis- and Trans-Regulatory Actions. Mol. Ther. J. Am. Soc. Gene Ther. 2021;29:1102–1119. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2020.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zheng L., Huang L., Chen Z., Cui C., Zhang R., Qin L. Magnesium Supplementation Alleviates Corticosteroid-Associated Muscle Atrophy in Rats. Eur. J. Nutr. 2021;60:4379–4392. doi: 10.1007/s00394-021-02598-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mercer T.R., Dinger M.E., Mattick J.S. Long Non-Coding RNAs: Insights into Functions. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2009;10:155–159. doi: 10.1038/nrg2521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Loo T.H., Ye X., Chai R.J., Ito M., Bonne G., Ferguson-Smith A.C., Stewart C.L. The Mammalian LINC Complex Component SUN1 Regulates Muscle Regeneration by Modulating Drosha Activity. eLife. 2019;8:e49485. doi: 10.7554/eLife.49485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Liu Y., Wang J., Zhou X., Cao H., Zhang X., Huang K., Li X., Yang G., Shi X. miR-324-5p Inhibits C2C12 Cell Differentiation and Promotes Intramuscular Lipid Deposition through lncDUM and PM20D1. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids. 2020;22:722–732. doi: 10.1016/j.omtn.2020.09.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Huang Q., Huang C., Luo Y., He F., Zhang R. Circulating lncRNA NEAT1 Correlates with Increased Risk, Elevated Severity and Unfavorable Prognosis in Sepsis Patients. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2018;36:1659–1663. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2018.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bovolenta M., Erriquez D., Valli E., Brioschi S., Scotton C., Neri M., Falzarano M.S., Gherardi S., Fabris M., Rimessi P., et al. The DMD Locus Harbours Multiple Long Non-Coding RNAs Which Orchestrate and Control Transcription of Muscle Dystrophin mRNA Isoforms. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e45328. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Xu X., Hao Y., Xiong S., He Z. Comprehensive Analysis of Long Non-Coding RNA-Associated Competing Endogenous RNA Network in Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy. Interdiscip. Sci. Comput. Life Sci. 2020;12:447–460. doi: 10.1007/s12539-020-00388-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Culligan K.G., Mackey A.J., Finn D.M., Maguire P.B., Ohlendieck K. Role of Dystrophin Isoforms and Associated Proteins in Muscular Dystrophy (Review) Int. J. Mol. Med. 1998;2:639–648. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2.6.639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gargaun E., Falcone S., Solé G., Durigneux J., Urtizberea A., Cuisset J.M., Benkhelifa-Ziyyat S., Julien L., Boland A., Sandron F., et al. The lncRNA 44s2 Study Applicability to the Design of 45-55 Exon Skipping Therapeutic Strategy for DMD. Biomedicines. 2021;9:219. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines9020219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shen Y., Kim I.-M., Hamrick M., Tang Y. Uncovering the Gene Regulatory Network of Endothelial Cells in Mouse Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy: Insights from Single-Nuclei RNA Sequencing Analysis. Biology. 2023;12:422. doi: 10.3390/biology12030422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Liu Y., Liu C., Zhang A., Yin S., Wang T., Wang Y., Wang M., Liu Y., Ying Q., Sun J., et al. Down-Regulation of Long Non-Coding RNA MEG3 Suppresses Osteogenic Differentiation of Periodontal Ligament Stem Cells (PDLSCs) through miR-27a-3p/IGF1 Axis in Periodontitis. Aging. 2019;11:5334–5350. doi: 10.18632/aging.102105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gehrig S.M., Ryall J.G., Schertzer J.D., Lynch G.S. Insulin-like Growth Factor-I Analogue Protects Muscles of Dystrophic Mdx Mice from Contraction-Mediated Damage. Exp. Physiol. 2008;93:1190–1198. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2008.042838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jing X., Han J., Zhang J., Chen Y., Yuan J., Wang J., Neo S., Li S., Yu X., Wu J. Long Non-Coding RNA MEG3 Promotes Cisplatin-Induced Nephrotoxicity through Regulating AKT/TSC/mTOR-Mediated Autophagy. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2021;17:3968–3980. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.58910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Peter A.K., Crosbie R.H. Hypertrophic Response of Duchenne and Limb-Girdle Muscular Dystrophies Is Associated with Activation of Akt Pathway. Exp. Cell Res. 2006;312:2580–2591. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2006.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Li Y., Zhang S., Zhang C., Wang M. LncRNA MEG3 Inhibits the Inflammatory Response of Ankylosing Spondylitis by Targeting miR-146a. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2020;466:17–24. doi: 10.1007/s11010-019-03681-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Messina S., Vita G.L., Aguennouz M., Sframeli M., Romeo S., Rodolico C., Vita G. Activation of NF-kB Pathway in Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy: Relation to Age. Acta Myol. 2011;30:16–23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Gu L., Zhang J., Shi M., Zhan Q., Shen B., Peng C. lncRNA MEG3 Had Anti-Cancer Effects to Suppress Pancreatic Cancer Activity. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2017;89:1269–1276. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2017.02.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Anderson J., Seol H., Hathout Y., Spurney C. Elevated St2 Serum Levels A Biomarker for Cardiomyopathy in Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2015;65:A997. doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(15)60997-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zhang D., Qin H., Leng Y., Li X., Zhang L., Bai D., Meng Y., Wang J. LncRNA MEG3 Overexpression Inhibits the Development of Diabetic Retinopathy by Regulating TGF-Β1 and VEGF. Exp. Ther. Med. 2018;16:2337–2342. doi: 10.3892/etm.2018.6451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ishitobi M., Haginoya K., Zhao Y., Ohnuma A., Minato J., Yanagisawa T., Tanabu M., Kikuchi M., Iinuma K. Elevated Plasma Levels of Transforming Growth Factor Β1 in Patients with Muscular Dystrophy. NeuroReport. 2000;11:4033. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200012180-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zhou Y., Zhang X., Klibanski A. MEG3 Noncoding RNA: A Tumor Suppressor. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 2012;48:R45–R53. doi: 10.1530/JME-12-0008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Saito T., Yamamoto Y., Matsumura T., Fujimura H., Shinno S. Serum Levels of Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Elevated in Patients with Muscular Dystrophy. Brain Dev. 2009;31:612–617. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2008.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zhang Y., Zou Y., Wang W., Zuo Q., Jiang Z., Sun M., De W., Sun L. Down-Regulated Long Non-Coding RNA MEG3 and Its Effect on Promoting Apoptosis and Suppressing Migration of Trophoblast Cells. J. Cell. Biochem. 2015;116:542–550. doi: 10.1002/jcb.25004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wang M., Huang T., Luo G., Huang C., Xiao X., Wang L., Jiang G., Zeng F. Long Non-Coding RNA MEG3 Induces Renal Cell Carcinoma Cells Apoptosis by Activating the Mitochondrial Pathway. J. Huazhong Univ. Sci. Technol. Med. Sci. 2015;35:541–545. doi: 10.1007/s11596-015-1467-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Li Y., Jiang J., Liu W., Wang H., Zhao L., Liu S., Li P., Zhang S., Sun C., Wu Y., et al. microRNA-378 Promotes Autophagy and Inhibits Apoptosis in Skeletal Muscle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2018;115:E10849–E10858. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1803377115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zhu X., Wu Y.-B., Zhou J., Kang D.-M. Upregulation of lncRNA MEG3 Promotes Hepatic Insulin Resistance via Increasing FoxO1 Expression. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2016;469:319–325. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.11.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Liu W., Liu X., Luo M., Liu X., Luo Q., Tao H., Wu D., Lu S., Jin J., Zhao Y., et al. dNK Derived IFN-γ Mediates VSMC Migration and Apoptosis via the Induction of LncRNA MEG3: A Role in Uterovascular Transformation. Placenta. 2017;50:32–39. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2016.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.von Moers A., Zwirner A., Reinhold A., Brückmann O., van Landeghem F., Stoltenburg-Didinger G., Schuppan D., Herbst H., Schuelke M. Increased mRNA Expression of Tissue Inhibitors of Metalloproteinase-1 and -2 in Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy. Acta Neuropathol. 2005;109:285–293. doi: 10.1007/s00401-004-0941-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Yang N.-Q., Luo X.-J., Zhang J., Wang G.-M., Guo J.-M. Crosstalk between Meg3 and miR-1297 Regulates Growth of Testicular Germ Cell Tumor through PTEN/PI3K/AKT Pathway. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2016;8:1091–1099. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Yue F., Song C., Huang D., Narayanan N., Qiu J., Jia Z., Yuan Z., Oprescu S.N., Roseguini B.T., Deng M., et al. PTEN Inhibition Ameliorates Muscle Degeneration and Improves Muscle Function in a Mouse Model of Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy. Mol. Ther. 2021;29:132–148. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2020.09.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Huang S., Xu Y., Ge X., Xu B., Peng W., Jiang X., Shen L., Xia L. Long Noncoding RNA NEAT1 Accelerates the Proliferation and Fibrosis in Diabetic Nephropathy through Activating Akt/mTOR Signaling Pathway. J. Cell. Physiol. 2019;234:11200–11207. doi: 10.1002/jcp.27770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Wang L., Yang D., Tian R., Zhang H. NEAT1 Promotes Retinoblastoma Progression via Modulating miR-124. J. Cell. Biochem. 2019;120:15585–15593. doi: 10.1002/jcb.28825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Zhang Y., Yao X.-H., Wu Y., Cao G.-K., Han D. LncRNA NEAT1 Regulates Pulmonary Fibrosis through miR-9-5p and TGF-β Signaling Pathway. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2020;24:8483–8492. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_202008_22661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Chen Y.-W., Zhao P., Borup R., Hoffman E.P. Expression Profiling in the Muscular Dystrophies. J. Cell Biol. 2000;151:1321–1336. doi: 10.1083/jcb.151.6.1321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Ding X.-M., Zhao L.-J., Qiao H.-Y., Wu S.-L., Wang X.-H. Long Non-Coding RNA-P21 Regulates MPP+-Induced Neuronal Injury by Targeting miR-625 and Derepressing TRPM2 in SH-SY5Y Cells. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2019;307:73–81. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2019.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ma M., Hui J., Zhang Q., Zhu Y., He Y., Liu X. Long Non-Coding RNA Nuclear-Enriched Abundant Transcript 1 Inhibition Blunts Myocardial Ischemia Reperfusion Injury via Autophagic Flux Arrest and Apoptosis in Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetic Rats. Atherosclerosis. 2018;277:113–122. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2018.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Bai Y., Lv Y., Wang W., Sun G., Zhang H. LncRNA NEAT1 Promotes Inflammatory Response and Induces Corneal Neovascularization. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 2018;61:231–239. doi: 10.1530/JME-18-0098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Zhang P., Cao L., Zhou R., Yang X., Wu M. The lncRNA Neat1 Promotes Activation of Inflammasomes in Macrophages. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:1495. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-09482-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Tu J., Zhao Z., Xu M., Lu X., Chang L., Ji J. NEAT1 Upregulates TGF-Β1 to Induce Hepatocellular Carcinoma Progression by Sponging Hsa-Mir-139-5p. J. Cell. Physiol. 2018;233:8578–8587. doi: 10.1002/jcp.26524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Chang S., Chen B., Wang X., Wu K., Sun Y. Long Non-Coding RNA XIST Regulates PTEN Expression by Sponging miR-181a and Promotes Hepatocellular Carcinoma Progression. BMC Cancer. 2017;17:248. doi: 10.1186/s12885-017-3216-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Yang J., Shen Y., Yang X., Long Y., Chen S., Lin X., Dong R., Yuan J. Silencing of Long Noncoding RNA XIST Protects against Renal Interstitial Fibrosis in Diabetic Nephropathy via microRNA-93-5p-Mediated Inhibition of CDKN1A. Am. J. Physiol.-Ren. Physiol. 2019;317:F1350–F1358. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00254.2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Sun J., Zhang Y. LncRNA XIST Enhanced TGF-Β2 Expression by Targeting miR-141-3p to Promote Pancreatic Cancer Cells Invasion. Biosci. Rep. 2019;39:BSR20190332. doi: 10.1042/BSR20190332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.McLennan I.S., Koishi K. Cellular Localisation of Transforming Growth Factor-Beta 2 and -Beta 3 (TGF-Beta2, TGF-Beta3) in Damaged and Regenerating Skeletal Muscles. Dev. Dyn. 1997;208:278–289. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(199702)208:2<278::AID-AJA14>3.0.CO;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Zhang Y., Wang J., Zhang Y., Wei J., Wu R., Cai H. Overexpression of Long Noncoding RNA Malat1 Ameliorates Traumatic Brain Injury Induced Brain Edema by Inhibiting AQP4 and the NF-κB/IL-6 Pathway. J. Cell. Biochem. 2019;120:17584–17592. doi: 10.1002/jcb.29025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Jimi T., Wakayama Y., Matsuzaki Y., Hara H., Inoue M., Shibuya S. Reduced Expression of Aquaporin 4 in Human Muscles with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis and Other Neurogenic Atrophies. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2004;200:203–209. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2004.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Han Y., Wu Z., Wu T., Huang Y., Cheng Z., Li X., Sun T., Xie X., Zhou Y., Du Z. Tumor-Suppressive Function of Long Noncoding RNA MALAT1 in Glioma Cells by Downregulation of MMP2 and Inactivation of ERK/MAPK Signaling. Cell Death Dis. 2016;7:e2123. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2015.407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Pan F., Zhu L., Lv H., Pei C. Quercetin Promotes the Apoptosis of Fibroblast-like Synoviocytes in Rheumatoid Arthritis by Upregulating lncRNA MALAT1. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2016;38:1507–1514. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2016.2755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Wu X.-S., Wang X.-A., Wu W.-G., Hu Y.-P., Li M.-L., Ding Q., Weng H., Shu Y.-J., Liu T.-Y., Jiang L., et al. MALAT1 Promotes the Proliferation and Metastasis of Gallbladder Cancer Cells by Activating the ERK/MAPK Pathway. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2014;15:806–814. doi: 10.4161/cbt.28584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Sun X., Luo L., Li J. LncRNA MALAT1 Facilitates BM-MSCs Differentiation into Endothelial Cells via Targeting miR-206/VEGFA Axis. Cell Cycle. 2020;19:3018–3028. doi: 10.1080/15384101.2020.1829799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Loufrani L., Dubroca C., You D., Li Z., Levy B., Paulin D., Henrion D. Absence of Dystrophin in Mice Reduces NO-Dependent Vascular Function and Vascular Density: Total Recovery after a Treatment with the Aminoglycoside Gentamicin. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2004;24:671–676. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000118683.99628.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Ji D.-G., Guan L.-Y., Luo X., Ma F., Yang B., Liu H.-Y. Inhibition of MALAT1 Sensitizes Liver Cancer Cells to 5-Flurouracil by Regulating Apoptosis through IKKα/NF-κB Pathway. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2018;501:33–40. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.04.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Aguennouz M., Vita G.L., Messina S., Cama A., Lanzano N., Ciranni A., Rodolico C., Di Giorgio R.M., Vita G. Telomere Shortening Is Associated to TRF1 and PARP1 Overexpression in Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy. Neurobiol. Aging. 2011;32:2190–2197. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2010.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Zheng S., Zhang X., Wang X., Li J. MIR31HG Promotes Cell Proliferation and Invasion by Activating the Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling Pathway in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Oncol. Lett. 2019;17:221–229. doi: 10.3892/ol.2018.9607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Feron M., Guevel L., Rouger K., Dubreil L., Arnaud M.-C., Ledevin M., Megeney L.A., Cherel Y., Sakanyan V. PTEN Contributes to Profound PI3K/Akt Signaling Pathway Deregulation in Dystrophin-Deficient Dog Muscle. Am. J. Pathol. 2009;174:1459–1470. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Cao L., Jiang H., Yang J., Mao J., Wei G., Meng X., Zang H. LncRNA MIR31HG Is Induced by Tocilizumab and Ameliorates Rheumatoid Arthritis Fibroblast-like Synoviocyte-Mediated Inflammation via miR-214-PTEN-AKT Signaling Pathway. Aging. 2021;13:24071–24085. doi: 10.18632/aging.203644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Wu Y., Jiang Y., Liu Q., Liu C.-Z. lncRNA H19 Promotes Matrix Mineralization through Up-Regulating IGF1 by Sponging miR-185-5p in Osteoblasts. BMC Mol. Cell Biol. 2019;20:48. doi: 10.1186/s12860-019-0230-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Chen X., Yang J., Shen H., Zhang X., Wang H., Wu G., Qi Y., Wang L., Xu W. Muc5ac Production Inhibited by Decreased lncRNA H19 via PI3K/Akt/NF-kB in Asthma. J. Asthma Allergy. 2021;14:1033–1043. doi: 10.2147/JAA.S316250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Wang Z.-M., Xia S.-W., Zhang T., Wang Z.-Y., Yang X., Kai J., Cheng X.-D., Shao J.-J., Tan S.-Z., Chen A.-P., et al. LncRNA-H19 Induces Hepatic Stellate Cell Activation via Upregulating Alcohol Dehydrogenase III-Mediated Retinoic Acid Signals. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2020;84:106470. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2020.106470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Hou J., Wang L., Wu Q., Zheng G., Long H., Wu H., Zhou C., Guo T., Zhong T., Wang L., et al. Long Noncoding RNA H19 Upregulates Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor A to Enhance Mesenchymal Stem Cells Survival and Angiogenic Capacity by Inhibiting miR-199a-5p. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2018;9:109. doi: 10.1186/s13287-018-0861-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Hu Z., Liu X., Guo J., Zhuo L., Chen Y., Yuan H. Knockdown of lncRNA MEG8 Inhibits Cell Proliferation and Invasion, but Promotes Cell Apoptosis in Hemangioma, via miR-203-induced Mediation of the Notch Signaling Pathway. Mol. Med. Rep. 2021;24:872. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2021.12512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Vieira N.M., Elvers I., Alexander M.S., Moreira Y.B., Eran A., Gomes J.P., Marshall J.L., Karlsson E.K., Verjovski-Almeida S., Lindblad-Toh K., et al. Jagged 1 Rescues the Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy Phenotype. Cell. 2015;163:1204–1213. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.10.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Sui S., Sun L., Zhang W., Li J., Han J., Zheng J., Xin H. LncRNA MEG8 Attenuates Cerebral Ischemia After Ischemic Stroke Through Targeting miR-130a-5p/VEGFA Signaling. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 2021;41:1311–1324. doi: 10.1007/s10571-020-00904-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Cabianca D.S., Casa V., Bodega B., Xynos A., Ginelli E., Tanaka Y., Gabellini D. A Long ncRNA Links Copy Number Variation to a Polycomb/Trithorax Epigenetic Switch in FSHD Muscular Dystrophy. Cell. 2012;149:819–831. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Castiglioni I., Caccia R., Garcia-Manteiga J.M., Ferri G., Caretti G., Molineris I., Nishioka K., Gabellini D. The Trithorax Protein Ash1L Promotes Myoblast Fusion by Activating Cdon Expression. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:5026. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-07313-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Dimartino D., Colantoni A., Ballarino M., Martone J., Mariani D., Danner J., Bruckmann A., Meister G., Morlando M., Bozzoni I. The Long Non-Coding RNA Lnc-31 Interacts with Rock1 mRNA and Mediates Its YB-1-Dependent Translation. Cell Rep. 2018;23:733–740. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.03.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Li Y., Zhang Y., Hu Q., Egranov S.D., Xing Z., Zhang Z., Liang K., Ye Y., Pan Y., Chatterjee S.S., et al. Functional Significance of Gain-of-Function H19 lncRNA in Skeletal Muscle Differentiation and Anti-Obesity Effects. Genome Med. 2021;13:137. doi: 10.1186/s13073-021-00937-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Tran T.H.T., Zhang Z., Yagi M., Lee T., Awano H., Nishida A., Okinaga T., Takeshima Y., Matsuo M. Molecular Characterization of an X(P21.2;Q28) Chromosomal Inversion in a Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy Patient with Mental Retardation Reveals a Novel Long Non-Coding Gene on Xq28. J. Hum. Genet. 2013;58:33–39. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2012.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Zhou M., Liu X., Qiukai E., Shang Y., Zhang X., Liu S., Zhang X. Long Non-Coding RNA Xist Regulates Oocyte Loss via Suppressing miR-23b-3p/miR-29a-3p Maturation and Upregulating STX17 in Perinatal Mouse Ovaries. Cell Death Dis. 2021;12:540. doi: 10.1038/s41419-021-03831-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.You L., Wang N., Yin D., Wang L., Jin F., Zhu Y., Yuan Q., De W. Downregulation of Long Noncoding RNA Meg3 Affects Insulin Synthesis and Secretion in Mouse Pancreatic Beta Cells. J. Cell. Physiol. 2016;231:852–862. doi: 10.1002/jcp.25175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Butchart L.C., Terrill J.R., Rossetti G., White R., Filipovska A., Grounds M.D. Expression Patterns of Regulatory RNAs, Including lncRNAs and tRNAs, during Postnatal Growth of Normal and Dystrophic (Mdx) Mouse Muscles, and Their Response to Taurine Treatment. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2018;99:52–63. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2018.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Bier A., Berenstein P., Kronfeld N., Morgoulis D., Ziv-Av A., Goldstein H., Kazimirsky G., Cazacu S., Meir R., Popovtzer R., et al. Placenta-Derived Mesenchymal Stromal Cells and Their Exosomes Exert Therapeutic Effects in Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy. Biomaterials. 2018;174:67–78. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2018.04.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Dong J., Xia R., Zhang Z., Xu C. lncRNA MEG3 Aggravated Neuropathic Pain and Astrocyte Overaction through Mediating miR-130a-5p/CXCL12/CXCR4 Axis. Aging. 2021;13:23004–23019. doi: 10.18632/aging.203592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]