Epithelia are tissues consisting of sheets of similar cells bound closely together, which include the epidermis, the surfaces of the eyes, the surfaces of the hollow tubes and sacs that make up the digestive, respiratory, reproductive, and urinary tracts, and the secretory cells and ducts of various glands. Depending on their predominant function, epithelia can be described further as barrier, secretory, or absorptive, but often all three functions coexist. These are the tissues most exposed to environmental bacteria. The importance of epithelia in host defense is best illustrated by the common experience that disruption of the epithelial layers, such as occurs in a minor skin scrape or a burn, greatly increases the likelihood of penetrating infection. Mechanical barrier properties of epithelia, the physical cleansing effects of their secretions, and the shedding of colonized cells normally contribute to protection from microbes (1). Moreover, injured or infected epithelial cells help initiate the inflammatory response by emitting chemotactic signals that attract blood-borne host defense cells. Although the ability of various glands to produce antimicrobial substances has been appreciated since Alexander Fleming's (2) pioneering studies of lysozyme in tears, respiratory secretions, and saliva, more recently it has become clear that barrier and absorptive epithelia also produce numerous antimicrobial substances (3–5). There are impressive similarities between the polypeptide arsenal of various epithelial cells and the prototypical professional host defense cells, the polymorphonuclear leukocytes. In some cases (e.g., lysozyme and lactoferrin), the same genes are highly expressed in both cell types; in other cases (e.g., defensins, peroxidase), the two cell types express different members of the same gene family. These similarities reinforce the notion that epithelial cells, like polymorphonuclear leukocytes, are important effectors of innate immunity.

In this issue of PNAS, Canny et al. (6) demonstrate that appropriately stimulated human epithelial cell lines as well as several specimens of human epithelial tissues express on their cell membranes bactericidal permeability-increasing protein (BPI), heretofore known as an abundant antimicrobial constituent of polymorphonuclear leukocytes (7, 8). BPI is bactericidal to many Gram-negative bacteria, a specificity that is determined by its avid binding to lipopolysaccharide (9), the major component of the external layer of the outer membrane of these bacteria. Canny et al. report that BPI inhibited the responses of epithelial cells to lipopolysaccharide and contributed to the ability of epithelial cells to kill Gram-negative bacteria. Expression of BPI in epithelia was discovered during an unbiased search for genes induced by treatment with ATLa, a synthetic congener of the (anti)inflammatory mediator lipoxin. The discovery points out the utility of the new large-scale screening methods for charting fresh directions in biological investigation.

Human epithelial cell lines express permeability-increasing protein (BPI), heretofore known as an abundant antimicrobial constituent.

However, much remains to be done before the new findings can be firmly placed in a biological context. The specific role of lipoxin signaling in epithelial responses to microbes is not yet understood and will require clarification. It will also be necessary to examine in more detail what kind of bacterial contact with epithelia is required for killing by membrane-associated BPI. In this regard, it is interesting to note that even in polymorphonuclear leukocytes most of the antimicrobial activity is associated with the membranes of storage granules (10), which eventually contribute membrane material to phagocytic vacuoles. Close apposition of bacterial and host membranes in both cell types could result in the transfer of BPI and other antimicrobial polypeptides into bacterial membranes whose affinity for cationic host defense polypeptides is much higher than that of host-derived membranes (11). The biology and biophysics of membranes loaded with highly concentrated antimicrobial polypeptides is a challenging area for further study.

Innate host defenses use both static and dynamic elements, with the latter having the capacity to recognize microbes and effect a response. Host defense responses to lipopolysaccharide are prototypic examples of pattern recognition (12, 13) in innate immunity. Unlike T cell antigen receptors and Abs, the pattern-recognition pathways are present in both vertebrates and invertebrates, are encoded by germ-line genes, and are fully activated within minutes to hours of first exposure. In general, the molecular patterns that trigger innate responses are found within essential structural components of microbes. Inflammation is a collective term for the tissue, cellular, and molecular consequences of these responses. Lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammation is often protective but also accounts for disease manifestations ranging from fever to shock and rapid death from infections with Gram-negative bacteria. Given the well known force of host defense responses to lipopolysaccharide it is amazing that animals harbor enormous numbers of symbiotic Gram-negative bacteria in their intestinal tracts without adverse consequences! The essential role of the intestinal epithelial barrier in confining Gram-negative bacteria is illustrated by injuries or diseases that disrupt this epithelium, with consequences ranging from localized inflammation and peritonitis to systemic shock.

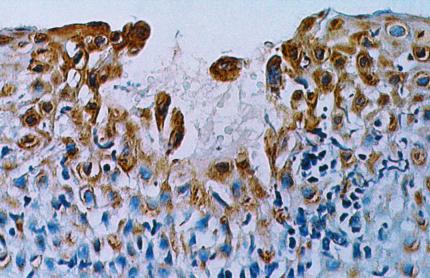

In this context, BPI may now be thought of as both an effector and a regulator of responses to lipopolysaccharide. To understand the role of BPI it is important to note that a related protein in blood plasma, lipopolysaccharide-binding protein (LBP), helps deliver lipopolysaccharide to specific receptor complexes (CD14/TLR4) on macrophages and other host defense cells (13–15) to activate the inflammatory response against Gram-negative bacteria. The latter response is so exquisitely sensitive that even picogram amounts of lipopolysaccharide generate detectable cellular effects. BPI competes with LBP (16, 17) for lipopolysaccharide, thus blunting the cellular responses to low concentrations of lipopolysaccharide. In the scenario proposed by Canny et al. (6), the expression of BPI on epithelial cells contributes to killing bacteria that become tightly adherent to epithelial cells, but at the same time, BPI inhibits the signals that would provoke a potentially injurious inflammatory response. This kind of yin-yang mechanism makes sense in limiting the response to a low-level infection in tissues where such infections are very frequent. BPI does not act alone as an antimicrobial effector and modulator of lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammation. Barrier and absorptive epithelial cells also produce constitutive and inducible β-defensins (Fig. 1) and cathelicidins, and secretory epithelial cells generate a complex mixture whose antimicrobial components include lysozyme and lactoferrin, lactoperoxidase, secretory leukoprotease inhibitor, phospholipase A2, and defensins. There is evidence that most of these cationic polypeptides also bind lipopolysaccharides [albeit with lower affinity than does BPI (18)] and may help blunt lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammation.

Figure 1.

A microscopic focus of infection is surrounded by epithelial cells that produce an antimicrobial peptide. A biopsy of human epidermis was stained by the immunoperoxidase method with Ab to human β-defensin-2 (HBD-2). Areas of HBD-2 accumulation are brown, and the tissue counterstain is blue. The image is courtesy of Lide Liu (Univ. of California, Los Angeles).

The location of the pattern-recognition receptors in epithelia may also be important for the close regulation of their responses. The toll-like pattern recognition receptors TLR2 (for peptidoglycan and mycobacterial glycolipids), TLR4 (for lipopolysaccharide), and TLR5 (for bacterial flagellin) are located on the basolateral surfaces (19, 20) of epithelial cells or on macrophages and other specialized host defense cells generally found below the epithelial surface. To activate such receptors, it is not sufficient for the microbes to make contact with the apical epithelium but they must penetrate the epithelial barrier, a much less frequent but more threatening occurrence. Along similar lines, the production of lipoxin, the mediator implicated in the induction epithelial BPI, generally requires the metabolic cooperation of two cell types, typically leukocytes and platelets or leukocytes and epithelial cells (21), which will rarely be found together in an undisturbed epithelium. The probability of such encounters is greatly increased when microbes penetrate the epithelium in an area of injury. The location of the lipopolysaccharide-recognition machinery inside the epithelial barrier may avoid the triggering of inflammatory responses by microbes that are innocuous or symbiotic colonists.

Clearly, epithelia are more than a physical barrier. They are dynamic host defense participants with sensors, signaling circuits, and effector molecules that coordinate and execute a graduated reaction to microbes. We are now on the verge of learning much more about the molecules and pathways of these epithelial responses.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant R01 HL46809.

Footnotes

See companion article on page 3902.

References

- 1.Metchnikoff E. Immunity in Infective Diseases. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge Univ. Press; 1905. pp. 403–432. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fleming A. Proc R Soc London B Biol Sci. 1922;93:306–317. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Diamond G, Zasloff M, Eck H, Brasseur M, Maloy W L, Bevins C L. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:3952–3956. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.9.3952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Valore E V, Park C H, Quayle A J, Wiles K R, McCray P B, Ganz T. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:1633–1642. doi: 10.1172/JCI1861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harder J, Bartels J, Christophers E, Schroeder J-M. Nature (London) 1997;387:861–862. doi: 10.1038/43088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Canny G, Levy O, Furuta G T, Narravula-Alipati S, Sisson R B, Serhan C N, Colgan S P. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:3902–3907. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052533799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weiss J, Elsbach P, Olsson I, Odeberg H. J Biol Chem. 1978;253:2664–2672. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elsbach P, Weiss J, Franson R C, Beckerdite Quagliata S, Schneider A, Harris L. J Biol Chem. 1979;254:11000–11009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mannion B A, Kalatzis E S, Weiss J, Elsbach P. J Immunol. 1989;142:2807–2812. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gabay J E, Heiple J M, Cohn Z A, Nathan C F. J Exp Med. 1986;164:1407–1421. doi: 10.1084/jem.164.5.1407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matsuzaki K, Sugishita K, Fujii N, Miyajima K. Biochemistry. 1995;34:3423–3429. doi: 10.1021/bi00010a034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoffmann J A, Kafatos F C, Janeway C A, Ezekowitz R A. Science. 1999;284:1313–1318. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5418.1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beutler B. Curr Opin Immunol. 2000;12:20–26. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(99)00046-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ulevitch R J, Tobias P S. Annu Rev Immunol. 1995;13:437–457. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.13.040195.002253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Poltorak A, He X, Smirnova I, Liu M Y, Huffel C V, Du X, Birdwell D, Alejos E, Silva M, Galanos C, et al. Science. 1998;282:2085–2088. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5396.2085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marra M N, Wilde C G, Griffith J E, Snable J L, Scott R W. J Immunol. 1990;144:662–666. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marra M N, Wilde C G, Collins M S, Snable J L, Thornton M B, Scott R W. J Immunol. 1992;148:532–537. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Levy O, Ooi C E, Elsbach P, Doerfler M E, Lehrer R I, Weiss J. J Immunol. 1995;154:5403–5410. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fusunyan R D, Nanthakumar N N, Baldeon M E, Walker W A. Pediatr Res. 2001;49:589–593. doi: 10.1203/00006450-200104000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gewirtz A T, Navas T A, Lyons S, Godowski P J, Madara J L. J Immunol. 2001;167:1882–1885. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.4.1882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Serhan C N, Takano T, Gronert K, Chiang N, Clish C B. Clin Chem Lab Med. 1999;37:299–309. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.1999.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]