Abstract

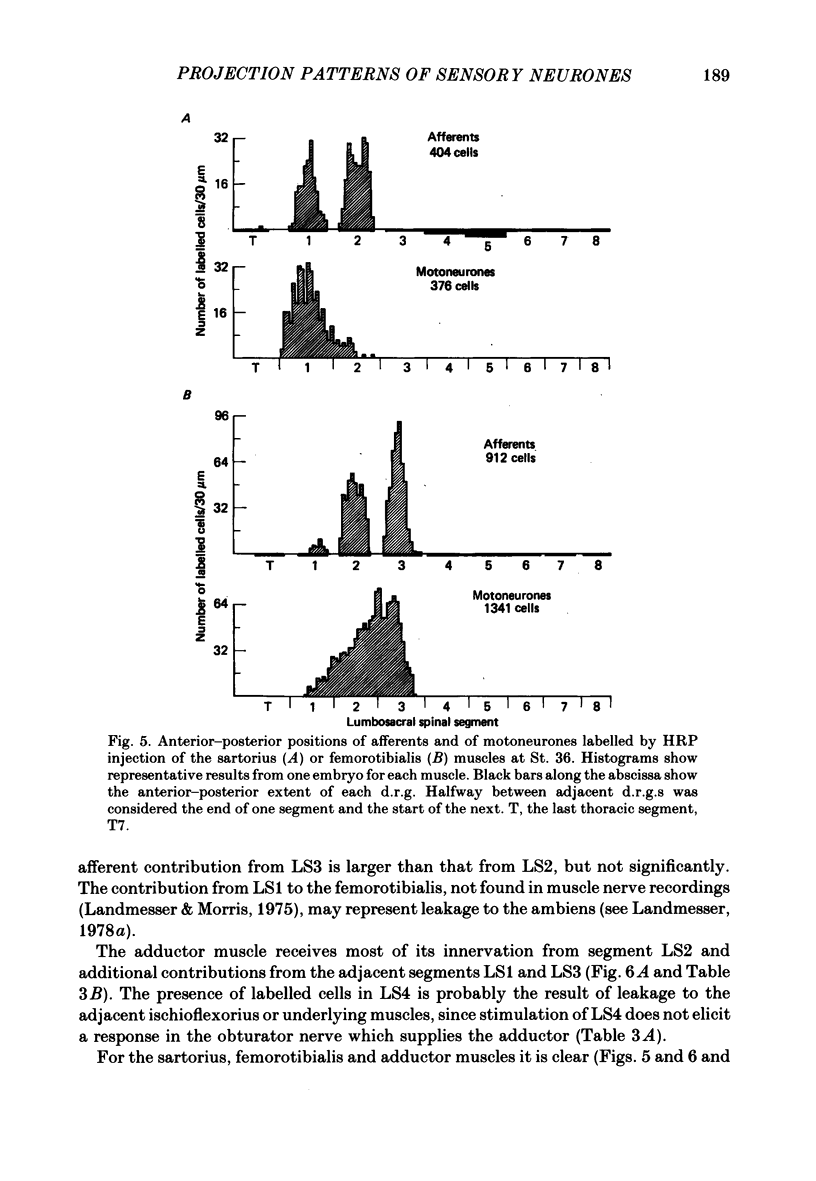

1. The distribution within individual dorsal root ganglia (d.r.g.s) of sensory neurones projecting to different targets in the embryonic chick hind limb was determined using the retrograde transport of horseradish peroxidase (HRP). The segmental pattern of sensory neurone projections was also defined, using retrograde and orthograde HRP labelling and electrophysiological techniques, from the onset of axonal outgrowth into the limb until after the period of sensory cell death. 2. At stage (St.) 29-30, shortly after initial axonal outgrowth into the limb, the large lateroventral neurones in the d.r.g.s projected both to skin and to muscle. At St. 36-37, after cell death in the d.r.g.s, cells from both the lateroventral and mediodorsal populations projected both to skin and to muscle. Thus these two cell populations do not correspond to cutaneous and proprioceptive afferents, respectively. 3. The cells projecting along individual cutaneous nerves or to individual muscles were always widely distributed throughout the ganglia. Thus, sensory neurones cannot be specified to project to particular peripheral targets as a result of their position in the d.r.g. Nevertheless, small clusters of cells were frequently found to project along the same peripheral nerve. 4. Since there is a correlation between position in the d.r.g. and time of origin, neurones projecting to each target have a wide range of birthdates, and, therefore, sensory neurones cannot be specified as a result of their birthdate. 5. At St. 36-38, after cell death, afferents to a given muscle or cutaneous nerve arise primarily from two or three adjacent segments out of the eight lumbosacral segments. For muscles these are the same segments that supply the motoneurones to that muscle. Each d.r.g. sends a characteristic proportion of axons down each of several peripheral nerves in a consistent and orderly pattern. 6. During initial outgrowth, the segmental projection pattern is similar to the pattern found in mature embryos. Thus, extensive projection 'errors' are not made and neither cell death nor retraction of axons is necessary for establishing the appropriate connectivity pattern. The majority of neurones do not send branches down more than one peripheral nerve. 7. Axons projecting to the same target are initially dispersed in the spinal nerves, and gradually segregate out in the plexus region, ultimately to form a separate nerve trunk. Axons projecting to different targets cross each other. Cutaneous and muscle nerves first form at the same stages. Therefore, the particular pathways axons take do not depend in any simple way on either axonal position in the plexus or time of arrival at the base of the limb. Simple timed outgrowth mechanisms and models in which axons maintain constant topographical relationships with each other therefore cannot generate the observed projection pattern. 8...

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Adrian E. D., Cattell M., Hoagland H. Sensory discharges in single cutaneous nerve fibres. J Physiol. 1931 Aug 14;72(4):377–391. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1931.sp002781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker R. E. Synapse selectivity in somatic afferent systems. Prog Brain Res. 1978;48:77–99. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(08)61017-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barde Y. A., Edgar D., Thoenen H. Sensory neurons in culture: changing requirements for survival factors during embryonic development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1980 Feb;77(2):1199–1203. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.2.1199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton H., McFarlane J. J. The organization of the seventh lumbar spinal ganglion of the cat. J Comp Neurol. 1973 May 15;149(2):215–232. doi: 10.1002/cne.901490207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr V. M., Simpson S. B., Jr Proliferative and degenerative events in the early development of chick dorsal root ganglia. I. Normal development. J Comp Neurol. 1978 Dec 15;182(4):727–739. doi: 10.1002/cne.901820410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr V. M., Simpson S. B., Jr Proliferative and degenerative events in the early development of chick dorsal root ganglia. II. Responses to altered peripheral fields. J Comp Neurol. 1978 Dec 15;182(4):741–755. doi: 10.1002/cne.901820411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen A. M. Factors directing the expression of sympathetic nerve traits in cells of neural crest origin. J Exp Zool. 1972 Feb;179(2):167–182. doi: 10.1002/jez.1401790204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen A. M. Independent expression of the adrenergic phenotype by neural crest cells in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1977 Jul;74(7):2899–2903. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.7.2899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaze R. M., Feldman J. D., Cooke J., Chung S. H. The orientation of the visuotectal map in Xenopus: developmental aspects. J Embryol Exp Morphol. 1979 Oct;53:39–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamburger V., Brunso-Bechtold J. K., Yip J. W. Neuronal death in the spinal ganglia of the chick embryo and its reduction by nerve growth factor. J Neurosci. 1981 Jan;1(1):60–71. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.01-01-00060.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamburger V. Cell death in the development of the lateral motor column of the chick embryo. J Comp Neurol. 1975 Apr 15;160(4):535–546. doi: 10.1002/cne.901600408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffer J. A., Stein R. B., Gordon T. Differential atrophy of sensory and motor fibers following section of cat peripheral nerves. Brain Res. 1979 Dec 14;178(2-3):347–361. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(79)90698-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hökfelt T., Elde R., Johansson O., Luft R., Nilsson G., Arimura A. Immunohistochemical evidence for separate populations of somatostatin-containing and substance P-containing primary afferent neurons in the rat. Neuroscience. 1976;1(2):131–136. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(76)90008-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JEFFERSON A. Aspects of the segmental innervation of the cat's hind limb. J Comp Neurol. 1954 Jun;100(3):569–596. doi: 10.1002/cne.901000306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson M. Cessation of DNA synthesis in retinal ganglion cells correlated with the time of specification of their central conections. Dev Biol. 1968 Feb;17(2):219–232. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(68)90062-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEVI-MONTALCINI R., HAMBURGER V. Selective growth stimulating effects of mouse sarcoma on the sensory and sympathetic nervous system of the chick embryo. J Exp Zool. 1951 Mar;116(2):321–361. doi: 10.1002/jez.1401160206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb A. H. The projection patterns of the ventral horn to the hind limb during development. Dev Biol. 1976 Nov;54(1):82–99. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(76)90288-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lance-Jones C., Landmesser L. Motoneurone projection patterns in the chick hind limb following early partial reversals of the spinal cord. J Physiol. 1980 May;302:581–602. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1980.sp013262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lance-Jones C., Landmesser L. Pathway selection by chick lumbosacral motoneurons during normal development. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1981 Dec 9;214(1194):1–18. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1981.0079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lance-Jones C., Landmesser L. Pathway selection by embryonic chick motoneurons in an experimentally altered environment. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1981 Dec 9;214(1194):19–52. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1981.0080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landmesser L. T. The generation of neuromuscular specificity. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1980;3:279–302. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.03.030180.001431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landmesser L., Morris D. G. The development of functional innervation in the hind limb of the chick embryo. J Physiol. 1975 Jul;249(2):301–326. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1975.sp011017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landmesser L. The development of motor projection patterns in the chick hind limb. J Physiol. 1978 Nov;284:391–414. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1978.sp012546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landmesser L. The distribution of motoneurones supplying chick hind limb muscles. J Physiol. 1978 Nov;284:371–389. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1978.sp012545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Douarin N. M., Renaud D., Teillet M. A., Le Douarin G. H. Cholinergic differentiation of presumptive adrenergic neuroblasts in interspecific chimeras after heterotopic transplantations. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1975 Feb;72(2):728–732. doi: 10.1073/pnas.72.2.728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Douarin N. M., Teillet M. A. Experimental analysis of the migration and differentiation of neuroblasts of the autonomic nervous system and of neurectodermal mesenchymal derivatives, using a biological cell marking technique. Dev Biol. 1974 Nov;41(1):162–184. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(74)90291-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtman J. W., Purves D., Yip J. W. On the purpose of selective innervation of guinea-pig superior cervical ganglion cells. J Physiol. 1979 Jul;292:69–84. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1979.sp012839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitolo V., Selvaggi F., Selvaggi L. Influences of the extent of the peripheral field of innervation on the volume of spinal ganglia and on the number of their nerve cells in chick embryos. Acta Embryol Morphol Exp. 1965 Oct;8(2):150–169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noden D. M. An analysis of migratory behavior of avian cephalic neural crest cells. Dev Biol. 1975 Jan;42(1):106–130. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(75)90318-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noden D. M. The control of avian cephalic neural crest cytodifferentiation. I. Skeletal and connective tissues. Dev Biol. 1978 Dec;67(2):296–312. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(78)90201-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noden D. M. The control of avian cephalic neural crest cytodifferentiation. II. Neural tissues. Dev Biol. 1978 Dec;67(2):313–329. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(78)90202-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norcio R., De Santis M. The organization of neuronal somata in the first sacral spinal ganglion of the cat. Exp Neurol. 1976 Jan;50(1):246–258. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(76)90251-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oppenheim R. W. Cell death of motoneurons in the chick embryo spinal cord. V. Evidence on the role of cell death and neuromuscular function in the formation of specific peripheral connections. J Neurosci. 1981 Feb;1(2):141–151. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.01-02-00141.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pannese E., Luciano L., Iurato S., Reale E. Intercellular junctions and other membrane specializations in developing spinal ganglia: a freeze-fracture study. J Ultrastruct Res. 1977 Aug;60(2):169–180. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5320(77)80063-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson P. H. Environmental determination of autonomic neurotransmitter functions. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1978;1:1–17. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.01.030178.000245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettigrew A. G., Lindeman R., Bennett M. R. Development of the segmental innervation of the chick forelimb. J Embryol Exp Morphol. 1979 Jan;49:115–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilar G., Landmesser L., Burstein L. Competition for survival among developing ciliary ganglion cells. J Neurophysiol. 1980 Jan;43(1):233–254. doi: 10.1152/jn.1980.43.1.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma S. C., Hollyfield J. G. Specification of retinotectal connexions during development of the toad Xenopus laevis. J Embryol Exp Morphol. 1980 Feb;55:77–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stirling R. V., Summerbell D. The segmentation of axons from the segmental nerve roots to the chick wing. Nature. 1979 Apr 12;278(5705):640–642. doi: 10.1038/278640a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swett J. E., Eldred E., Buchwald J. S. Somatotopic cord-to-muscle relations in efferent innervation of cat gastrocnemius. Am J Physiol. 1970 Sep;219(3):762–766. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1970.219.3.762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueyama T. The topography of root fibres within the sciatic nerve trunk of the dog. J Anat. 1978 Oct;127(Pt 2):277–290. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verna J. M., Saxod R. Développement de l'innervation cutanée chez le poulet: analyse ultrastructurale et quantitative. Arch Anat Microsc Morphol Exp. 1979;68(1):1–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weston J. A., Butler S. L. Temporal factors affecting localization of neural crest cells in tbe chicken embryo. Dev Biol. 1966 Oct;14(2):246–266. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(66)90015-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida S., Matsuda Y. Studies on sensory neurons of the mouse with intracellular-recording and horseradish peroxidase-injection techniques. J Neurophysiol. 1979 Jul;42(4):1134–1145. doi: 10.1152/jn.1979.42.4.1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]