Abstract

1. The development of dermatomes in the chick hind limb was investigated with both electrophysiological recording from and horseradish peroxidase (HRP) labelling of neurones in lumbosacral dorsal root ganglia (d.r.g.s). The embryonic stages studied spanned the period before and after cell death.

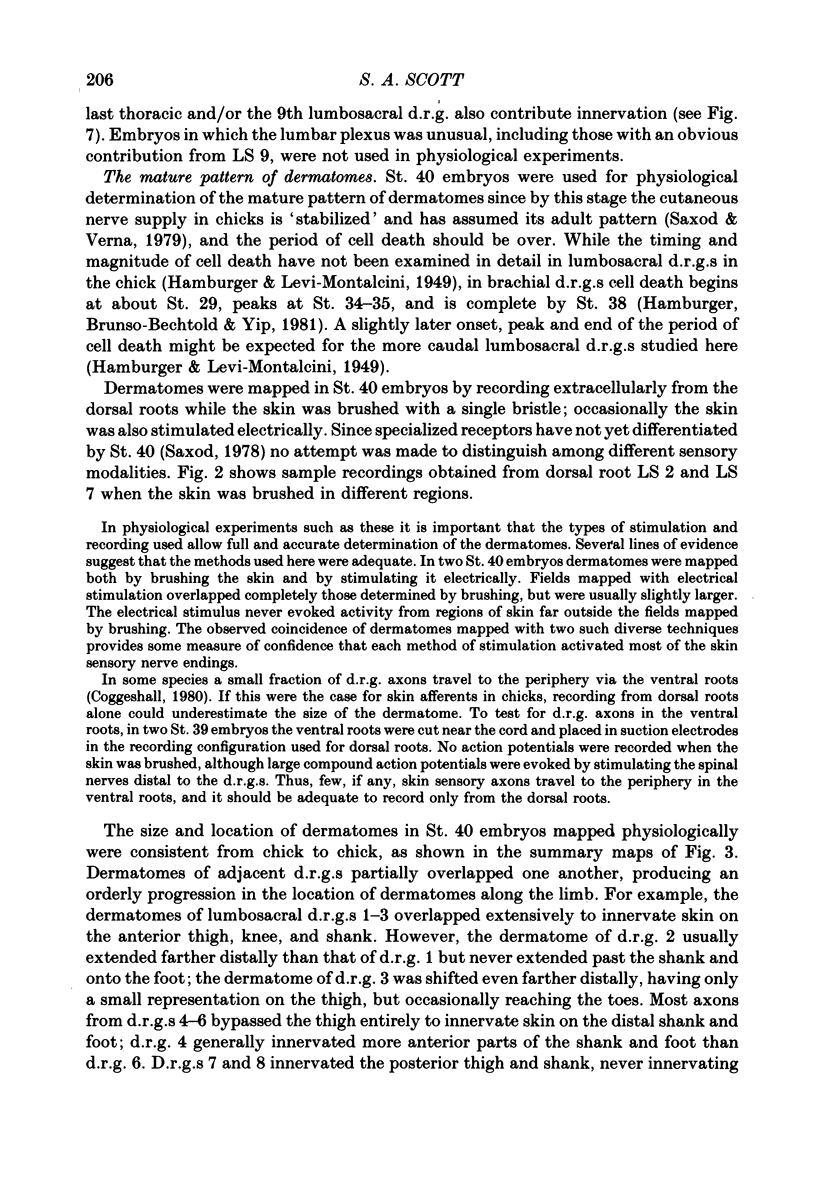

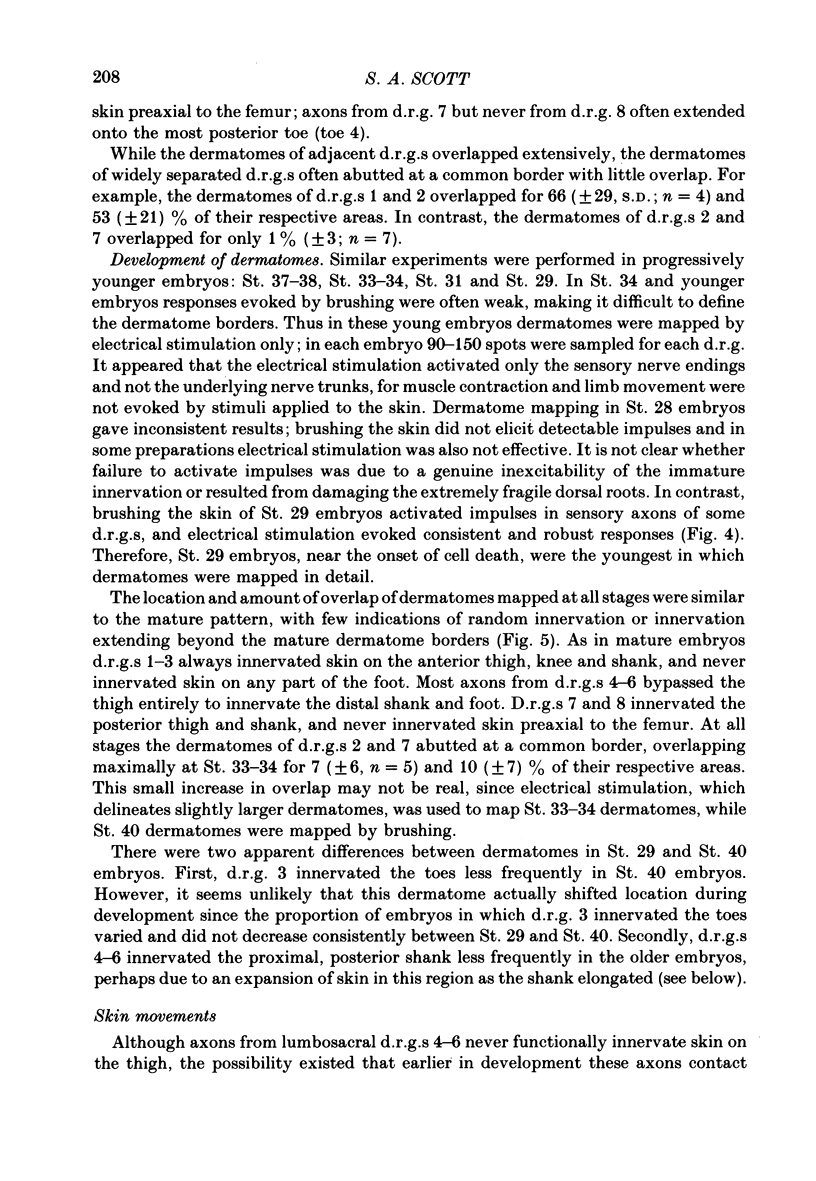

2. In mature embryos, after the bulk of cell death, physiological mapping showed that the location of the dermatome of each d.r.g. is consistent from embryo to embryo. HRP studies showed that axons from each d.r.g. project through the limb to the skin via a characteristic set of nerve trunks. Both the dermatomes and axonal projection pathways of adjacent d.r.g.s partially overlap one another, producing an orderly progression in the location of dermatomes and projection pathways along and within the limb, respectively.

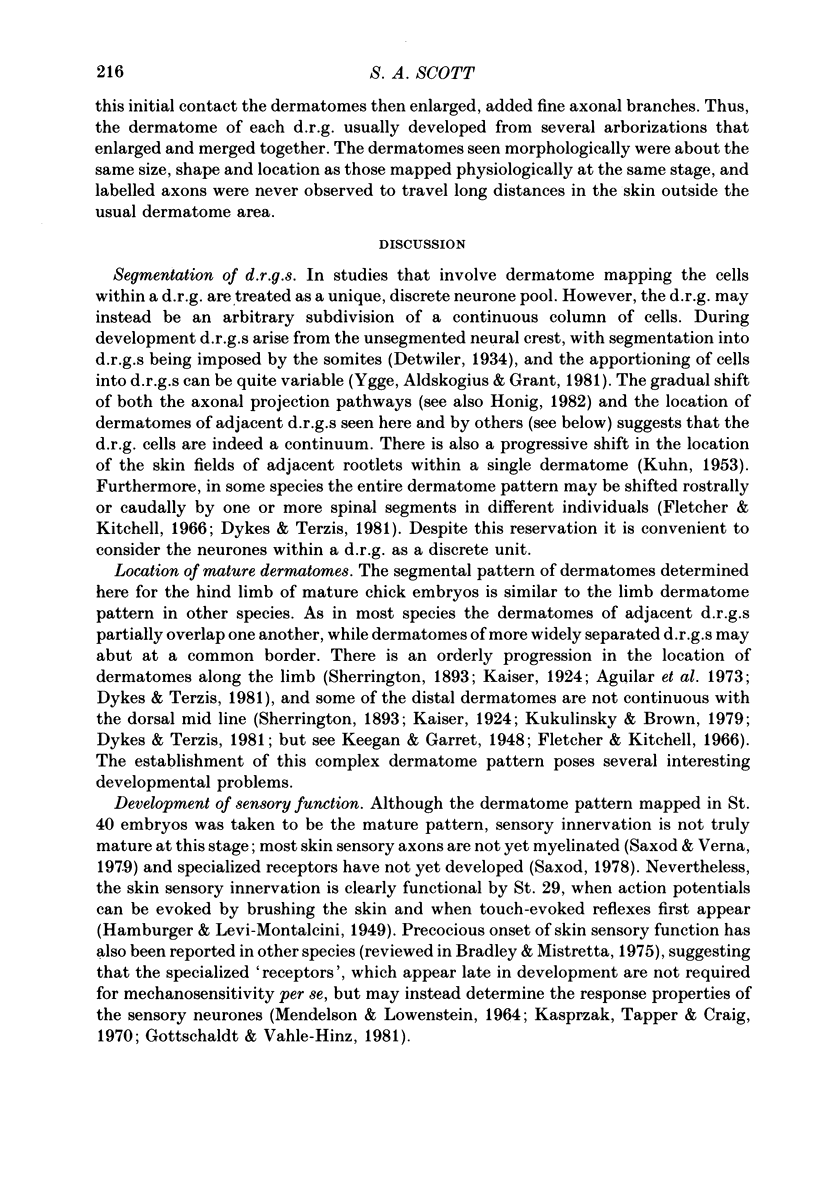

3. In younger embryos, before cell death, the location and amount of overlap of dermatomes, as well as the axonal projection pathways, are similar to the mature pattern. D.r.g.s that innervate distal skin on the shank and foot in mature embryos do not project out cutaneous nerve trunks in the thigh or contact nearby skin on the thigh at earlier stages.

4. Axons from a single d.r.g. initially contact the skin at one or more characteristic spots; the dermatomes then enlarge, adding fine axonal branches.

5. Carbon-marking experiments showed that there are no large distal migrations of skin on the limb during the stages studied.

6. Together these findings show that dermatomes on the chick hind limb do not develop by skin sensory axons simply growing to the nearest available skin, nor are axons towed to their final location by skin movements. Moreover, dermatomes are not shaped by cell death and the elimination of random or excessive axonal projections in the limb or the skin. It appears that skin sensory axons from each d.r.g. grow directly to their target skin along a defined set of pathways and establish their dermatome precisely at its characteristic location.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Aguilar C. E., Bisby M. A., Cooper E., Diamond J. Evidence that axoplasmic transport of trophic factors is involved in the regulation of peripheral nerve fields in salamanders. J Physiol. 1973 Oct;234(2):449–464. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1973.sp010354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley R. M., Mistretta C. M. Fetal sensory receptors. Physiol Rev. 1975 Jul;55(3):352–382. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1975.55.3.352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson B. M. The effects of rotation and positional change of stump tissues upon morphogenesis of the regenerating axolotl limb. Dev Biol. 1975 Dec;47(2):269–291. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(75)90282-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coggeshall R. E. Law of separation of function of the spinal roots. Physiol Rev. 1980 Jul;60(3):716–755. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1980.60.3.716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole J. P., Lesswing A. L., Cole J. R. An analysis of the lumbosacral dermatomes in man. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1968 Nov-Dec;61:241–247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dykes R. W., Terzis J. K. Spinal nerve distributions in the upper limb: the organization of the dermatome and afferent myotome. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1981 Aug 12;293(1070):509–554. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1981.0083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher T. F., Kitchell R. L. The lumbar, sacral and coccygeal tactile dermatomes of the dog. J Comp Neurol. 1966 Oct;128(2):171–180. doi: 10.1002/cne.901280204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank E., Harris W. A., Kennedy M. B. Lysophosphatidyl choline facilitates labeling of CNS projections with horseradish peroxidase. J Neurosci Methods. 1980 Apr;2(2):183–189. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(80)90059-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottschaldt K. M., Vahle-Hinz C. Merkel cell receptors: structure and transducer function. Science. 1981 Oct 9;214(4517):183–186. doi: 10.1126/science.7280690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamburger V., Brunso-Bechtold J. K., Yip J. W. Neuronal death in the spinal ganglia of the chick embryo and its reduction by nerve growth factor. J Neurosci. 1981 Jan;1(1):60–71. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.01-01-00060.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honig M. G. The development of sensory projection patterns in embryonic chick hind limb. J Physiol. 1982 Sep;330:175–202. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1982.sp014336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KUHN R. A. Organization of tactile dermatomes in cat and monkey. J Neurophysiol. 1953 Mar;16(2):169–182. doi: 10.1152/jn.1953.16.2.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasprzak H., Tapper D. N., Craig P. H. Functional development of the tactile pad receptor system. Exp Neurol. 1970 Mar;26(3):439–446. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(70)90140-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kukulinsky D. H., Brown P. B. Cat L4-S1 dermatomes determined using signal averaging. Neurosci Lett. 1979 Jun;13(1):79–82. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(79)90079-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landmesser L., Morris D. G. The development of functional innervation in the hind limb of the chick embryo. J Physiol. 1975 Jul;249(2):301–326. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1975.sp011017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landmesser L. The development of motor projection patterns in the chick hind limb. J Physiol. 1978 Nov;284:391–414. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1978.sp012546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landmesser L. The distribution of motoneurones supplying chick hind limb muscles. J Physiol. 1978 Nov;284:371–389. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1978.sp012545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MENDELSON M., LOWENSTEIN W. R. MECHANISMS OF RECEPTOR ADAPTATION. Science. 1964 May 1;144(3618):554–555. doi: 10.1126/science.144.3618.554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesulam M. M. Tetramethyl benzidine for horseradish peroxidase neurohistochemistry: a non-carcinogenic blue reaction product with superior sensitivity for visualizing neural afferents and efferents. J Histochem Cytochem. 1978 Feb;26(2):106–117. doi: 10.1177/26.2.24068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesulam M. M. The blue reaction product in horseradish peroxidase neurohistochemistry: incubation parameters and visibility. J Histochem Cytochem. 1976 Dec;24(12):1273–1280. doi: 10.1177/24.12.63512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oppenheim R. W. Cell death of motoneurons in the chick embryo spinal cord. V. Evidence on the role of cell death and neuromuscular function in the formation of specific peripheral connections. J Neurosci. 1981 Feb;1(2):141–151. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.01-02-00141.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettigrew A. G., Lindeman R., Bennett M. R. Development of the segmental innervation of the chick forelimb. J Embryol Exp Morphol. 1979 Jan;49:115–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

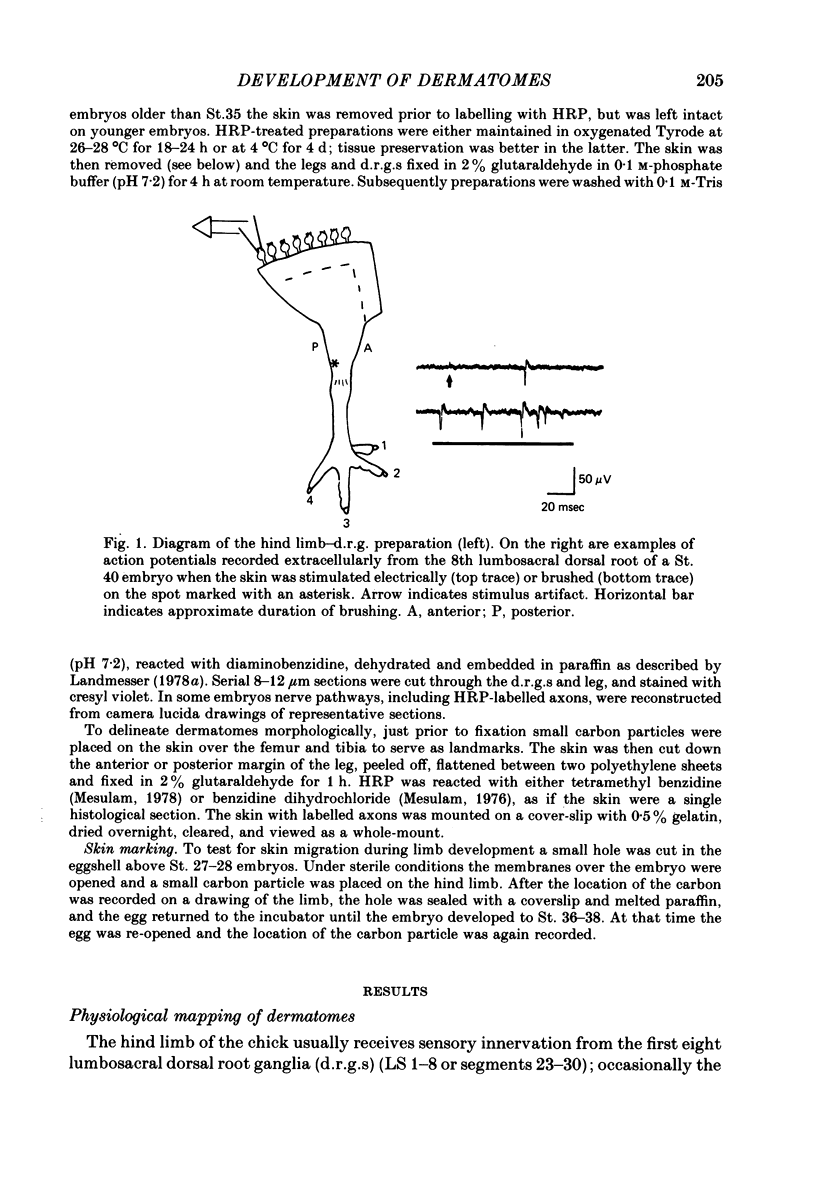

- Ygge J., Aldskogius H., Grant G. Asymmetries and symmetries in the number of thoracic dorsal root ganglion cells. J Comp Neurol. 1981 Nov 1;202(3):365–372. doi: 10.1002/cne.902020306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]