Abstract

The integrase protein (Int) from bacteriophage λ catalyzes the insertion and excision of the viral genome into and out of Escherichia coli. It is a member of the λ-Int family of site-specific recombinases that catalyze a diverse array of DNA rearrangements in archaebacteria, eubacteria, and yeast and belongs to the subset of this family that possesses two autonomous DNA-binding domains. The heterobivalent properties of Int can be decomposed into a carboxyl-terminal domain that executes the DNA cleavage and ligation reactions and a smaller amino-terminal domain that binds to an array of conserved DNA sites within the phage arms, thereby arranging Int protomers within the higher-order recombinogenic complex. We have determined that residues Met-1 to Leu-64 of Int constitute the minimal arm-type DNA-binding domain (INT-DBD1–64) and solved the solution structure by using NMR. We show that the INT-DBD1–64 is a novel member of the growing family of three-stranded β-sheet DNA-binding proteins, because it supplements this motif with a disordered amino-terminal basic tail that is important for arm-site binding. A model of the arm-DNA-binding domain recognizing its cognate DNA site is proposed on the basis of similarities with the analogous domain of Tn916 Int and is discussed in relation to other features of the protein.

The integrase protein (Int) of Escherichia coli phage λ (1) catalyzes the integration and excision of the viral genome into and out of its host chromosome (2). It belongs to a subgroup of the λ-Int family of site-specific recombinases whose members are distinguished by heterobivalent DNA binding. This ability to simultaneously bridge two distinct and well separated DNA sequences, called arm- and core-type sites is a key architectural element in the formation of recombinogenic higher-order complexes (for recent reviews, see refs. 3 and 4).

Underlying the functional diversity of the λ-Int family is a common set of chemical reactions in which the DNA cleavage/ligation reactions are mediated by transient covalent phosphotyrosine intermediates that first generate and then resolve Holliday junction recombination intermediates via two sequential pairs of strand exchanges. The locus of these reactions on each partner DNA duplex is a pair of 9- to 13-bp inverted binding sites for the recombinase (core-type sites) separated by a 6- to 8-bp overlap region (7 bp in the case of λ) whose boundaries are defined by the staggered and precisely positioned DNA cleavage sites. The att sites of the heterobivalent recombinases contain additional protein-binding sites that comprise flanking “arms,” called P and P′, in the λ viral attP site. Within these arms are five closely related, high-affinity, arm-type Int sites (P1, P2, P′1, P′2, P′3) that are unrelated to the low-affinity, core-type Int sites. Interspersed between the two classes of Int sites are binding sites for the accessory proteins, IHF, Xis, and Fis, all of which introduce sharp bends in their DNA-binding sites, thus bringing the distal arm-type Int-binding sites into close proximity with the core-type Int sites, where DNA cleavage and ligation are executed.

The first suggestion that λ-Int had two functional domains was made by Kikuchi and Nash (5) when they found that pretreating Int with N-ethylmaleimide (NEM) abolished both recombination activity and the formation of nonfilterable, heparin-resistant complexes but did not impair Int's ability to cleave and reseal DNA. We now know that λ-Int consists of three functional domains (6–8). The small, 7-kDa amino-terminal domain containing the NEM-sensitive site, Cys-25, is responsible for high-affinity binding to each of the five arm-type sites and is also a context-sensitive modulator of DNA cleavage (9, 10). The central core-binding domain (residues 65–169) and the carboxyl-terminal catalytic domain (residues 170–356) comprise a large functional domain (called C65) that is very efficient in DNA binding and cleavage reactions at core-type sites.

A great deal is known about the large carboxyl-terminal region of λ-Int and the mechanism of DNA cleavage and ligation from the crystal structure of several λ-Int family members (11–16). In contrast, very little is known about the amino-terminal domain, which is not related to any protein of known structure based on its primary sequence. In the experiments reported here, we have delineated the minimal region within Int required for efficient arm-type DNA binding and solved its structure by using NMR spectroscopy. We propose that Int recognizes the arms of the phage by using a three-stranded β-sheet and present a model of its DNA complex.

Materials and Methods

Site-Directed Mutagenesis, Protein Expression, and Purification.

The desired mutations were made by PCR and oligonucleotide-directed mutagenesis and cloned into the pRT101 backbone by using NdeI and EcoRI restriction enzymes (8), and the constructs were confirmed by DNA sequencing of the entire Int gene. Several truncated versions of λ-Int extending different distances from the amino terminus were generated by PCR and were fused to the Intein moiety of the affinity purification system in pIMC104 DNA (Intein vector; New England Biolabs) by using the restriction endonucleases SapI and PstI (17). The constructs were verified by DNA sequencing. E. coli BL21(DE3) cells containing appropriate plasmid constructs were grown at 37°C to an OD600 of 0.45–0.50, and expression of the fusion protein was induced by isopropyl β-d-thiogalactoside (0.3 mM). Cells were grown at 18°C for 12–14 h and harvested. Isotopic labeling of proteins with 15N, or 15N and 13C, was accomplished by growing the cells in minimal medium containing 15NH4Cl and unlabeled or 13C6-labeled glucose as the sole nitrogen and carbon sources, respectively. The affinity-purified protein in 30 mM Hepes, pH 8.0/1 mM EDTA/5 mM benzamidine containing 45 mM DTT was dialyzed extensively to remove excess DTT and concentrated by using Centricon membrane (Millipore). The amino-terminal variants of λ-Int do not contain extra amino acids at their amino termini. Int (wild type and mutant) proteins and IHF were expressed and purified as described (8, 18).

Sample Preparation for NMR Spectroscopy.

INT-DBD1–64 purified as described above was denatured in 0.1% TFA and loaded onto a C-4 reverse-phase HPLC column (Waters). The final NMR sample consisted of ≈1 mM INT-DBD1–64 (15N- or 15N/13C-labeled) in 20 mM potassium phosphate, pH 6.0/100 mM NaCl/0.01% NaN3/10 mM deuterated DTT (90%H2O:10%D2O). The NMR spectra of INT-DBD1–64 recorded before and after the HPLC purification step essentially are identical, indicating that the protein refolds into its native conformation. The protein–DNA complex consisted of a 1:1 mixture of 15N-labeled INT-DBD1–64 and a 14-bp DNA duplex containing the P′1 site obtained from Midland CRC [sequence listed below; see (i)]. The concentration of each component was measured by UV absorbance, mixed at high concentration (≈0.5 mM each) in high salt (≈300 mM NaCl), and then dialyzed and concentrated to the final NMR sample, which consisted of ≈0.4 mM complex, 20 mM potassium phosphate (pH 6.0), 0.01% NaN3, and 10 mM deuterated DTT.

Oligonucleotides.

Synthetic oligos (HPLC-purified) used for biochemical studies [(ii) and (iii), below] were obtained from Operon Technologies (Alameda, CA) and end-labeled with [γ-32P]ATP (NEN) by using T4 polynucleotide kinase. Sequences of the “top” strands for each of the double-stranded oligos used in this work are as follows (Int-binding sites are noted as bold, uppercase letters):

(i) 14-mer P′1 arm-site DNA, 5′-ccAGGTCACTATgg-3′; (ii) 19-mer P′1 arm-site DNA, 5′-cgaacAGGTCACTATtggc-3′; and (iii) 19-mer “anti-P′1” (heterologous) DNA, 5′-cgaacCTTGACAGCGtggc-3′.

The oligos were annealed in 10 mM Tris⋅HCl (pH 7.5) containing 50 mM NaCl. The sequence of “anti-P′1” DNA was derived from the P′1 sequence by interchanging all of the A's and C's and all of the G's and T's; it was used as nonspecific competitor DNA in binding assays. The 31-bp, top-strand nicked COC′ suicide substrate has been described (9).

NMR Spectroscopy.

NMR experiments were performed at 290 K on Bruker DRX-500 and -600 MHz spectrometers equipped with xyz-gradient triple-resonance probes. Protein resonances (1H,15N,13C) were assigned by using three-dimensional HNCA, HNCO, HNCOCA, HNCACB, CBCA(CO)NH, HCCH-total correlation spectroscopy (TOCSY), HCCH–correlated spectroscopy, and 15N-edited TOCSY experiments (19). 3JHNα-coupling constants, χ1 angles, and χ2 angles were analyzed by using quantitative J-correlation experiments (20) and nuclear Overhauser effect (NOE) patterns (21). Distance restraints were obtained from three-dimensional 15N- and 13C-edited NOE spectroscopy–heteronuclear sequential quantum correlation experiments (mixing times: 75, 125, and 150 ms). All spectra were processed by using nmrpipe (22) and analyzed by using the programs pipp, capp, and stapp (23).

Structure Calculations.

Residues Met-1-Arg-10 and Lys-60-Leu-64 do not exhibit any long-range NOEs and were omitted from the final simulated annealing calculations. NOE restraints were grouped into four distance ranges: 1.8–2.7 Å (1.8–2.9 Å for distances involving 15N-bound protons), 1.8–3.3 Å (1.8–3.5 Å for distances involving 15N-bound protons), 1.8–5.0 Å, and 1.8–6.0 Å. To account for the increased apparent intensity of restraints, 0.5 Å was added to the upper distance limits of those involving methyl protons. Distances involving methyl protons, aromatic ring protons, and nonstereospecifically assigned methylene protons were represented as a (Σr6)−1/6 sum (24). At the final stage of refinement, hydrogen bond restraints were added based on the atoms' position in the ensemble of structures and NOE patterns. HN, N, Cα, Hα, Cβ, and C′ chemical shifts were used for database searches by using the program talos (25). Structures were calculated by using the program x-plor 3.843 (26). The specific, simulated annealing protocol has been described (27, 28). The program procheck 3.4.4 was used to evaluate the final ensemble of conformers (29). Figures were prepared by using the program molmol (30). The coordinates of the INT-DBD1–64 have been deposited (PDB ID code 1KJK).

Assays of Int Function.

Recombination assays were carried out essentially as described (31) by using supercoiled attP (pWR1) and linearized attB DNA (BamHI-digested and [α-32P]dCTP-labeled pWR101) plasmid DNA at a 2-fold molar excess over its supercoiled recombination partner. Reactions were terminated by the addition of 0.2% SDS and analyzed by 1.2% agarose gel. DNA-binding experiments using gel-retardation assays and Int-mediated suicide substrate cleavage assays were carried out as reported (9, 31). The gels were dried, autoradiographed, and quantitated by a phosphorimager (Fuji).

Results

Defining the Minimal Arm-Type DNA-Binding Domain.

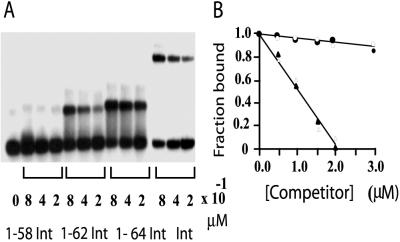

To precisely define the minimal domain necessary for binding to arm-type DNA, several different amino-terminal constructs, terminating at residues Gly-58, Lys-62, and Leu-64, were cloned, purified, and tested in gel-shift assays for their ability to bind radiolabeled P′1 arm-type DNA (Fig. 1A). The construct spanning residues Met-1–Gly-58 failed to form any complexes stable to gel electrophoresis. The Met-1–Lys-62 construct, at comparable protein concentrations, formed complexes of the expected mobility with about 3- to 4-fold-less efficiency than full-length Int, and the Met-1–Leu-64 construct was almost as efficient as the full-length protein. The specificity of the Met-1–Leu-64 construct was demonstrated by its resistance to competition by an unlabeled heterologous DNA competitor relative to the homologous competitor (Fig. 1B). Residues Met-1 to Leu-64 thus are necessary and sufficient for binding to a P′1 arm-type DNA site.

Figure 1.

Defining the minimal arm-type DNA-binding domain. (A) Full-length Int and three amino-terminal peptides, cloned and purified as described in Materials and Methods, were tested in a gel-shift assay for their respective abilities to bind arm-type DNA. The indicated concentrations of proteins were mixed with 0.1 μM radiolabeled, 19-bp P′1 arm-type DNA and incubated at 25°C for 20 min (see Materials and Methods). Full-length Int binding was done in a separate experiment with substrate of lower specific activity. After electrophoresis on an 8% polyacrylamide gel, the gels were dried and visualized by autoradiography. (B) The specificity of DNA binding by Int (filled symbols) and the INT-DBD1–64 (open symbols) was assayed by mixing 0.4 μM protein with 0.1 μM P′1 arm-type DNA in the presence of the indicated amounts of homologous (triangles) or heterologous (circles) competitor oligonucleotides (see Materials and Methods). The assays and quantitation were as in A. Binding in the absence of competitor, 45% for Int and 39% for 1–64 peptide, was normalized to 100%.

Three-Dimensional Structure of the Minimal Arm-Site-Binding Domain.

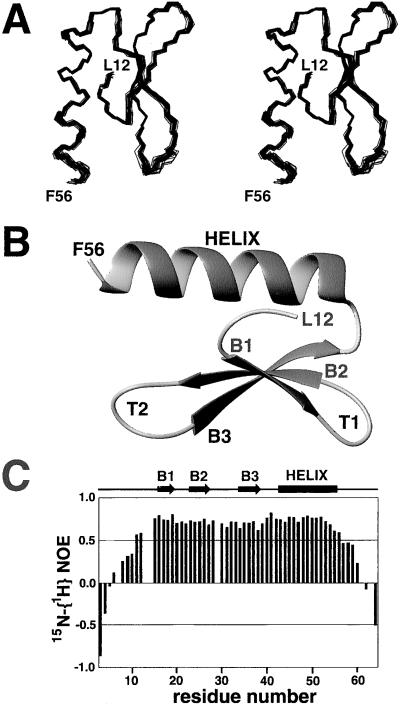

Having defined the minimal arm-site-binding domain within the λ-Int protein (residues Met-1–Leu-64, INT-DBD1–64), we determined its three-dimensional structure to gain insights into its function. The structure was solved by using multidimensional, heteronuclear NMR methods and hybrid distance geometry and simulated annealing calculations. An ensemble of 25 structures was calculated that is consistent with the experimental data; they exhibit no NOE, 3JHNα, or dihedral angle violations greater than 0.5Å, 2 Hz, or 0.5°, respectively (Table 1). The structures are well defined by the NMR data, and residues Leu-12–Leu-55 in the ensemble of conformers can be superimposed to the average structure with a rms deviation (rmsd) of 0.38 ± 0.07 Å for the backbone atoms and 0.93 ± 0.11 Å for all heavy atoms (Fig. 2A).

Table 1.

Structural statistics

| 〈SA〉 | (SA)BEST | |

|---|---|---|

| rmsd from NOE interproton distance restraints, Å* | ||

| All (661) | 0.037 ± 0.003 | 0.029 |

| Protein interresidue sequential (|i − j| = 1) (192) | 0.045 ± 0.004 | 0.044 |

| Protein interresidue short range (1 < |i − j| ≤ 5) (147) | 0.035 ± 0.005 | 0.024 |

| Protein interresidue long range (|i − j| > 5) (189) | 0.029 ± 0.007 | 0.027 |

| Protein intraresidue (133) | 0.034 ± 0.006 | 0.029 |

| rmsd from hydrogen-bonding restraints, ņ | 0.014 ± 0.008 | 0.020 |

| rmsd from dihedral angle restraints, ° (64)‡ | 0.097 ± 0.111 | 0.044 |

| rmsd from 3JHNα coupling constants, Hz (34) | 0.495 ± 0.047 | 0.452 |

| rmsd from secondary 13C chemical shifts, p.p.m. | ||

| 13Cα (43) | 1.017 ± 0.066 | 0.989 |

| 13Cβ (43) | 0.860 ± 0.036 | 0.879 |

| Deviations from idealized covalent geometry | ||

| Bonds, Å | 0.004 ± 0.0002 | 0.003 |

| Angles, deg. | 0.431 ± 0.018 | 0.396 |

| Impropers, deg. | 0.347 ± 0.058 | 0.259 |

| procheck-NMR§ | ||

| Most favored regions, % | 89.6 ± 0.086 | 91.9 |

| Additionally allowed regions, % | 8.9 ± 0.389 | 5.4 |

| Generously allowed regions, % | 1.5 ± 0.302 | 2.7 |

| Disallowed regions, % | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Coordinate precision, Ŷ | ||

| Protein backbone | 0.38 ± 0.07 | |

| All protein heavy atoms | 0.93 ± 0.11 |

The notation of the NMR structures is as follows: 〈SA〉 are the final 25 simulated annealing structures; (SA)BEST is the lowest energy structure in the ensemble. The number of terms for each restraint is given in parentheses. Residues Met-1–Arg-10 and Lys-60–Leu-64 displayed no cross-strand NOE cross-peaks in the data and were omitted from the final simulated annealing calculations.

None of the structures exhibited distance violations greater than 0.5 Å, dihedral angle violations greater than 5°, or 3JHNα coupling constant violations greater than 2 Hz.

Two distance restraints were used for each hydrogen bond (rNH⩵O ≤ 2.5Å and rN⩵O ≤ 3.5 Å).

The experimental dihedral angle restraints consisted of 34 φ, 11 χ1, and 2 χ2 angle restraints.

The values reported are for residues Leu-12–Leu-55, using procheck 3.4.4 (29).

The coordinate precision is defined as the average atomic rmsd of the 25 individual SA structures and their mean coordinates. The reported values are for residues Leu-12–Leu-55 of the protein. The backbone value refers to the N, C, and CO atoms.

Figure 2.

NMR solution structure of the INT-DBD1–64. (A) A stereoview of the ensemble of 25 structures showing the backbone atoms (N, Cα, and C′) from residues Leu-12–Phe-56. (B) A ribbon diagram of the lowest energy structure showing residues Leu-12–Phe-56 of INT-DBD1–64. The three strands of the anti-parallel β-sheet are labeled B1 (Leu-16–Ile-18), B2 (Tyr-24–Arg-27), and B3 (Glu-34–Gly-38). The C-terminal α-helix extends from Arg-41 to Leu-55. The structure is rotated 90° clockwise relative to A. (C) 15N-{1H} heteronuclear NOE data recorded on a uniformly 15N-labeled sample of the INT-DBD1–64. The figure shows NOE values for all nonproline residues from Arg-3 to Leu-64, with the exception of His7 and His-61, which are overlapped in the spectra.

The INT-DBD1–64 folds into a three-stranded, antiparallel β-sheet that packs against a C-terminal α-helix (Fig. 2B). Strands B1 (Leu-16–Ile-18) and B2 (Tyr-24–Arg-27) of the sheet are connected by a type-1β turn (T1, Arg-19–Tyr-23), whereas strands B2 and B3 (Glu-34–Gly-38) are separated by a six-residue extended turn (T2, Asp-28–Lys-33). Strand B3 contains a β-bulge, with the amide protons of Leu-37 and Gly-38 forming cross-strand hydrogen bonds to the CO atom of Tyr-24. A C-terminal α-helix (Arg-41–Leu-55) is positioned approximately parallel with strand B2 and stabilized by hydrophobic interactions between the side chains of Tyr-24, Tyr-26, Ala-44, Ala-48, and Ala-51. These residues, along with the side chains of Pro-13, Leu-16, Pro-29, Leu-37, Ile-45, and Leu-55, form the hydrophobic core of the protein. The packing of the helix is defined further by a hydrogen bond between the side chains of Asn-15 and Asn-52, which positions the N terminus of strand B1 relative to the helix. Residues Arg-3–Arg-10 and Lys-60–Leu-64 are disordered in the structure and highly mobile on the picosecond time scale, as judged by the small magnitude of their 15N-{1H} heteronuclear NOEs (less than 0.4, Fig. 2C).

Role of the Amino-Terminal Arg Residues.

Although the first 10 aa of the INT-DBD1–64 are unstructured and flexible in the absence of DNA, this portion of the polypeptide contains three sequential Arg residues (Arg-3–Arg-5), which are of the correct charge to interact with DNA. To test the functional significance of these residues, three amino-terminal deletion mutants of the full-length protein were constructed. These mutants substitute lysine for Gly2 of the primary sequence and progressively delete amino acids Arg-3, Arg-4, and Arg-5, and G2KΔ1R, G2KΔ2R, and G2KΔ3R, respectively. The mutants were assayed for arm-type DNA binding, integrative recombination, and the ability to cleave COC′ “suicide substrates.”

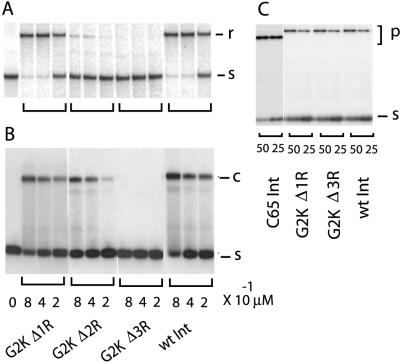

All of the constructs retain DNA cleavage activity, consistent with our previous data demonstrating that the carboxyl-terminal domain (residues Thr-65–Lys-356) is fully competent for catalysis (7). The G2KΔ1R mutant deletes a single Arg amino acid but has the same number of positive charges as the wild-type protein, and, indeed, they are indistinguishable based on all measures of Int function (Fig. 3). However, when two Arg residues are deleted to give a net loss of one positive charge (mutant G2KΔ2R), recombinase activity and arm-type DNA binding both are reduced. Deletion of three Arg residues (net loss of two positive charges) virtually abolishes arm-type DNA binding and recombinase activity. These results suggest that Arg-4 and Arg-5, which are disordered in the absence of DNA, nevertheless are important for recombinase activity, presumably because they are involved in arm-type DNA binding (see below). The undiminished activity of the Lys-for-Arg substitution suggests that two consecutive positive charges in this region may be sufficient for efficient DNA binding.

Figure 3.

Functional assays of amino-terminal Arg deletions. Arm-binding domains carrying deletions of one to three Arg residues (Δ1R, Δ2R, and Δ3R) were constructed and purified as described in the text. (A) The indicated amounts of wild-type and mutant Int proteins (lanes labeled below B) were assayed for their ability to recombine unlabeled circular attP and linear 32P-labeled attB DNAs (see Materials and Methods). After gel electrophoresis of the recombination mixtures, the 32P-labeled attB (s) and linear recombination product (r) were visualized by autoradiography. (B) Gel mobility-shift assays for arm-type DNA binding were performed as described in Fig. 1. The Int-bound P′1 DNA complex (c) and the unbound substrate DNA (s) are indicated on the figure. (C) DNA cleavage by the indicated proteins, including the large, carboxyl-terminal domain (C65), was assayed by their ability to form covalent complexes (p) with a top strand-nicked COC′ suicide substrate (s) and analyzed by 12% SDS-polyacrylamide gels followed by autoradiography.

The loss of two positive residues in the INT-DBD1–64 apparently has not compromised any of the functions of the carboxyl-terminal domain or the ability of the amino-terminal domain to suppress the functions of the carboxyl-terminal domain. The deletion mutant is similar to wild-type, full-length Int in being depressed for DNA cleavage, relative to the activity of the isolated carboxyl-terminal domain (Fig. 3C). At the Int concentrations used here, the full-length Int is reduced ≈1.8-fold relative to the isolated carboxyl-terminal domain, whereas at lower Int concentrations, this difference increases to 3-fold (9).

The Unstructured N-Terminal Tail Interacts with DNA.

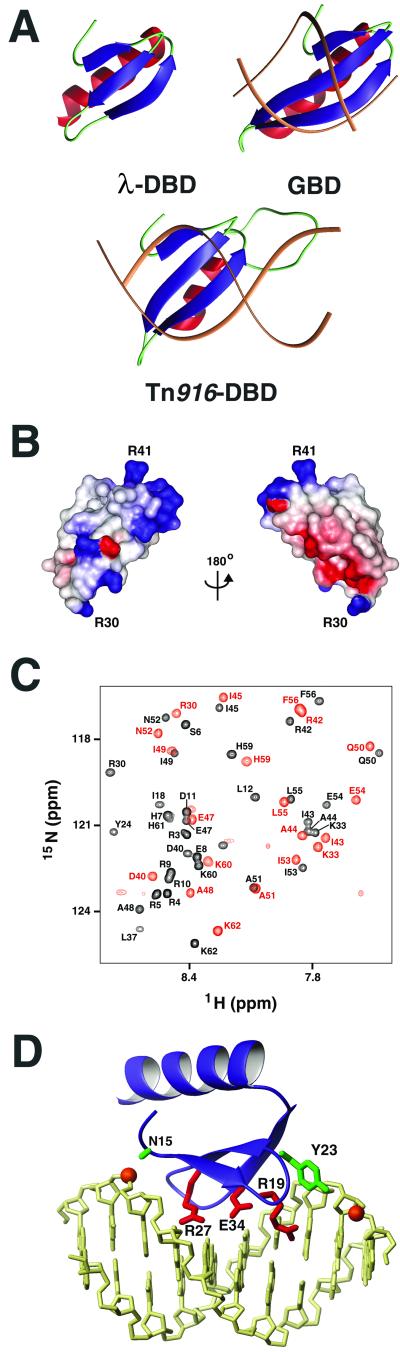

To substantiate the finding that the N-terminal tail in the full-length λ-Int protein is required for DNA binding, NMR spectroscopy was used to study its interaction with DNA within the context of the isolated amino-terminal domain. In this experiment, 1H-15N heteronuclear single quantum correlation spectra of the 15N-labeled INT-DBD1–64 in the presence or absence of DNA were compared to identify DNA-dependent changes in the chemical shifts of the backbone amide nitrogen and hydrogen atoms. Although the spectrum of the 1:1 INT-DBD1–64/DNA complex is well resolved, its low concentration precludes its complete and unambiguous resonance assignment. However, a superficial analysis clearly indicates that the chemical shifts of amino acids within the N-terminal tail, β-sheet, and turn T1 are perturbed significantly by DNA binding, whereas amino acids within the C-terminal α-helix largely are unaffected by the addition of DNA. For example, in the absence of DNA, the amide cross-peaks of residues Arg-3 to Arg-10 exhibit narrow line-widths and chemical shifts that indicate they adopt a random-coil conformation (Fig. 4C). However, when the 14-bp duplex DNA containing the P′1 site is added, these cross-peaks are affected significantly, exhibiting either large changes in their chemical shifts or resonance line-broadening (Fig. 4C). These data support the biochemical studies (Fig. 3) and suggest that the β-sheet and N-terminal tail comprise or are near the protein–DNA interface.

Figure 4.

β-Sheet DNA-binding domains and model of the INT-DBD1–64/DNA complex. (A) A structural comparison of the lowest energy structure of the INT-DBD1–64, Tn916-DBD complex (27, 28, 32, 33), and AtERF1 GBD (27, 28, 32, 33). The antiparallel β-sheet is blue, and the C-terminal helix is red. The Tn916-DBD and GBD were solved in complex with DNA (brown). (B) Electrostatic surface potential of the INT-DBD1–64. The structure on the left is orientated similar to that of A. Positive charges are in blue, and negative charges are in red. (C) Overlay of a selected region of the 1H-15N heteronuclear single quantum correlation spectrum of the INT-DBD1–64 with (red) and without (black) DNA. It should be noted that the 1H-15N heteronuclear single quantum correlation spectrum of the complex was recorded at a lower salt concentration as compared with the spectrum of the free protein (0 vs. 100 mM NaCl). However, the NMR spectrum of the isolated INT-DBD1–64 protein does not change significantly as a function of salt, indicating that the spectral changes are a direct result of DNA binding (data not shown). (D) Model of the INTDBD1–64/DNA complex. The INT-DBD1–64 (blue) is docked to B form DNA (yellow) containing the P′1 arm-type sequence. Side chains that are poised to contact the major groove are shown in red. The Asn-15 amide proton and Tyr-23 side chain (green) are predicted to contact phosphate groups (orange spheres), interactions that are conserved in the structures of other three-stranded β-sheet protein–DNA complexes.

Discussion

Our results indicate that the INT-DBD1–64 adopts a fold that is structurally related to the three-stranded β-sheet family of DNA-binding domains (Fig. 4A) (27, 28, 32, 33). These proteins include, among others, the GCC-box DNA-binding domain (GBD) and the N-terminal domain of Tn916 integrase (Tn916-DBD) (34). Although the INT-DBD1–64 shares only a low degree of primary sequence homology to these proteins, it nevertheless adopts a similar fold; the secondary structural elements of the INT-DBD1–64 can be superimposed to the GBD and Tn916-DBD with a Cα atom coordinate rmsd of 2.0 Å and 2.5 Å, respectively. Our finding that the INT-DBD1–64 is structurally related to the N-terminal domain of Tn916 integrase is of particular interest, because Tn916 integrase mediates the transposition of the conjugative transposon Tn916 by using a mechanism that apparently is related to the lambdoid phages.

Structural similarity, in conjunction with biochemical and NMR mapping experiments, indicates that the INT-DBD1–64 will recognize sequence-specifically the major groove of the arm-type sites through its β-sheet. The structures of the GBD and Tn916-DBD solved in complex with DNA reveal a similar mode of binding, in which side chains extending from the sheet contact nucleotide bases through the major groove (Fig. 4A). The electrostatic surface potential of the structurally similar INT-DBD1–64 is consistent with this mode of recognition, because its β-sheet surface is positively charged and thus suitable for DNA binding (Fig. 4B). In contrast, the opposite surface of the protein contains a helix that is more negatively charged. β-Sheet-mediated DNA binding by the INT-DBD1–64 is supported further by our limited chemical shift-mapping data, which coarsely localize its binding surface to residues within the N-terminal tail and β-sheet (Fig. 4C).

To gain insights into the mechanism of arm-type binding by the λ-Int protein, we constructed a model of INT-DBD1–64 bound to its cognate DNA site (Fig. 4D), which was constructed by superimposing the backbone atoms of the free INT-DBD1–64 structure onto the structure of the GBD protein within the GBD-DNA complex (32). In the structures of GBD, Tn916-DBD, and the I-Ppo1 protein–DNA complexes, amino acids located at conserved positions within the β-sheet motif form similar types of interactions with the duplex (34). It can be predicted reliably that the INT-DBD1–64 will contact the DNA by presenting the alternating surface-exposed side chains of its β-sheet. In particular, the side chains of Tyr-17 and Arg-19 in strand B1; Tyr-23, Cys-25, and Arg-27 in strand B2; and Glu-34 within strand B3 are all expected to reside at the molecular interface. Sequence-specific recognition likely will involve the side chains of Arg-19, Arg-27, and Glu-34, which are expected to project into the major groove. Two conserved protein–phosphate contacts are visualized in the model: the amide of Asn-15 appears to hydrogen-bond to a phosphate along the DNA backbone, and the Tyr-23 hydroxyl proton likely contacts a phosphate on the opposite strand (Fig. 4D).

The model provides a structural explanation for how NEM incorporation at Cys-25 results in a loss of recombination function whereas mutants C25S and C25A retain full activity (10). The side chain of Cys-25 is located at the DNA interface; however, it is not close enough to make an intermolecular hydrogen bond. In the model, a bulky maleimide moiety attached to the sulfhydryl group of Cys-25 would disrupt the protein–DNA interface by sterically hindering DNA contacts from the nearby side chains of Arg-27 and Glu-34. The model is consistent with biochemical data demonstrating the importance of Arg-4 or Arg-5 in DNA binding (Fig. 3). The amino-terminal tail of the protein is poised for interactions with the sugar–phosphate backbone and/or minor groove. However, the details of these interactions cannot be predicted, because this region of the protein is mobile and unstructured in the absence of DNA and because this appendage is not present in other three-stranded β-sheet, DNA-binding domains. Although the model does not explain our finding that residues His-59 to Leu-64 are important for binding (Fig. 1A), it is conceivable that these amino acids contribute to the stability of the protein through packing interactions with the β-sheet; alternatively, they may become structured upon DNA binding, forming favorable contacts to the sugar–phosphate backbone.

From our results, a “switch model” in which the amino-terminal residues would interact alternatively either with arm-type DNA, in the stimulating mode, or with an acidic patch on the carboxyl-terminal domain, in the suppressive mode, is not likely because deletions of the Arg residues that abolish arm-type DNA binding did not compromise the ability to suppress carboxyl-terminal domain function (Fig. 3C). Our studies also suggest it is unlikely that Cys-25 would be at or near a protein–protein interface, Int is bound to arm-type DNA sites. BMH-mediated protein–protein cross-linking at Cys-25 (35) might be promoted by DNA binding primarily at the carboxyl-terminal domain, but it is likely to be competitive with arm-type DNA binding. Protein–protein interactions may involve amino acids within the α-helix of the amino-terminal domain. An R42L mutation increases Int binding 10-fold to a single P′1 site and 100-fold to DNA containing the P′1, P′2, and P′3 sites compared with the wild-type protein (36). In the structure of INT-DBD1–64, Arg-42 is located at the N terminus of the helix near the side chains of Ile-45, Ile-49, and Ile-53. Interestingly, these amino acids form a solvent-exposed hydrophobic surface that might be involved in cooperative interactions with other Int molecules bound to arm-type sites. Our present data do not offer any insights on the remaining potential functions of the amino-terminal domain, such as interaction with one or both of the accessory factors IHF and Xis—possibilities that currently are under investigation.

Acknowledgments

We thank Gregg Gariepy, Tina Oliveira, Junji Iwahara, and Robert Peterson for technical assistance, Joan Boyles for manuscript preparation, and members of the Clubb and Landy laboratories for advice and helpful comments. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants GM62723 and GM33928 (to A.L.), and GM57487 (to R.T.C.).

Abbreviations

- Int

integrase protein

- NEM

N-ethylmaleimide

- NOE

nuclear Overhauser effect

- rmsd

rms deviation

- GBD

GCC-box DNA-binding domain

- DBD

DNA-binding domain

Footnotes

Data deposition: The atomic coordinates have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, www.rcsb.org (PDB ID code 1KJK).

References

- 1.Kikuchi Y, Nash H A. J Biol Chem. 1978;253:7149–7157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Campbell A M. Advances in Genetics. New York: Academic; 1962. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grainge I, Jayaram M. Mol Microbiol. 1999;33:449–456. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01493.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Azaro M A, Landy A. Mobile DNA II. Washington, DC: Am. Soc. Microbiol.; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kikuchi Y, Nash H A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76:3760–3764. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.8.3760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moitoso de Vargas L, Pargellis C C, Hasan N M, Bushman E W, Landy A. Cell. 1988;54:923–929. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90107-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tirumalai R S, Healey E, Landy A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:6104–6109. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.12.6104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tirumalai R S, Kwon H J, Cardente E H, Ellenberger T, Landy A. J Mol Biol. 1998;279:513–527. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.1786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sarkar D, Radman-Livaja M, Landy A. EMBO J. 2001;20:1203–1212. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.5.1203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tirumalai R S, Pargellis C A, Landy A. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:29599–29604. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.47.29599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hickman A B, Waninger S, Scocca J J, Dyda F. Cell. 1997;89:227–237. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80202-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kwon H J, Tirumalai R, Landy A, Ellenberger T. Science. 1997;276:126–131. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5309.126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Subramanya H S, Arciszewska L K, Baker R A, Bird L E, Sherratt D J, Wigley D B. EMBO J. 1997;16:5178–5187. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.17.5178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cheng C H, Kussie P, Pavletich N, Shuman S. Cell. 1998;92:841–850. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81411-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Redinbo M R, Stewart L, Kuhn P, Champoux J J, Hol W G J. Science. 1998;279:1504–1513. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5356.1504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gou F, Gopaul D N, Van Duyne G D. Nature (London) 1997;389:40–46. doi: 10.1038/37925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chong S R, Mersha F B, Comb D G, Scott M E, Landry D, Vence L M, Perler F B, Benner J, Kucera R B, Hirvonen C A, et al. Gene. 1997;192:271–281. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(97)00105-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nash H A, Robertson C A, Flamm E, Weisberg R A, Miller H I. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:4124–4127. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.9.4124-4127.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cavanagh J, Fairbrother W J, Palmer A G I, Skelton N J. Protein NMR Spectroscopy. San Diego: Academic; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bax A, Vuister G W, Grzesiek S, Delaglio F, Wang A C, Tschudin R, Zhu G. Methods Enzymol. 1994;239:79–105. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(94)39004-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Powers R, Garrett D S, March C J, Frieden E A, Gronenborn A M, Clore G M. Biochemistry. 1993;32:6744–6762. doi: 10.1021/bi00077a030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Delaglio F. J Biomol NMR. 1995;6:277–293. doi: 10.1007/BF00197809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garrett D S, Powers R, Gronenborn A M, Clore G M. J Magn Res. 1991;95:214–220. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nilges M. Proteins Struct Funct Genet. 1993;17:295–309. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cornilescu G, Delaglio F, Bax A. J Biomol NMR. 1999;13:289–302. doi: 10.1023/a:1008392405740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brünger A T. x-plor 3.1: A System for X-Ray Crystallography and NMR. New Haven, CT: Yale Univ.; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Connolly K M, Wojciak J M, Clubb R T. Nat Struct Biol. 1998;5:546–550. doi: 10.1038/799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wojciak J M, Connolly K M, Clubb R T. Nat Struct Biol. 1999;6:366–373. doi: 10.1038/7603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Laskowski R A, Rullmann J A C, MacArthur M W, Kaptein R, Thornton J M. J Biomol NMR. 1996;8:477–486. doi: 10.1007/BF00228148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Koradi R, Billeter M, Wuthrich K. J Mol Graphics. 1996;14:51–55. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00009-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pargellis C A, Nunes-Düby S E, Moitoso de Vargas L, Landy A. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:7678–7685. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Allen M D, Yamasaki K, Ohme-Takagi M, Tateno M, Suzuki M. EMBO J. 1998;17:5484–5496. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.18.5484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Flick K E, Jurica M S, Monnat R J, Jr, Stoddard B L. Nature (London) 1998;394:96–101. doi: 10.1038/27952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Connolly K M, Ilangovan U, Wojciak J M, Iwahara M, Clubb R T. J Mol Biol. 2000;300:841–856. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jessop L, Bankhead T, Wong D, Segall A M. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:1024–1034. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.4.1024-1034.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cheng Q, Swalla B M, Beck M, Alcaraz R, Gumport R I, Gardner J F. Mol Microbiol. 2000;36:424–436. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01860.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]