Abstract

Conjugated linoleic acid (CLA) has received much attention for its beneficial physiological effects, particularly anticancer and metabolic control activity. However, traditional sources rely on extraction and chemical synthesis, both of which are not commercially viable. This article describes the research progress on sustainable alternative biosynthesis methods for the production of CLA, which is an attractive approach for commercial production because of its high stereoselectivity and convenient purification process. Here, we offer a comprehensive review of the current state and research progress in the biosynthesis of CLA, including production strains, biosynthesis mechanisms and improvements in the biosynthesis of CLA by genetic engineering. Finally, future research directions for improving the biosynthesis of CLA are defined in the light of recent advances, barriers and trends in this field.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s40643-025-00911-7.

Keywords: Conjugated Linoleic acid, Linoleic acid isomerase, Biotransformation, De Novo biosynthesis, Synthetic biology

Introduction

Conjugated linoleic acid (CLA), which is found primarily in ruminant meat and milk, is a general name for the positional and geometric isomers of linoleic acid (LA) with a conjugated double bond. Among the many isomeric forms of CLA, cis-9,trans-11-CLA (c9,t11-CLA) and trans-10, cis-12-CLA (t10,c12-CLA) are the two most abundant and important isomers with notable physiological activity (Wu et al. 2024; Yang et al. 2017). Because of its unique molecular structure, CLA can alleviate the symptoms of diabetes, atherosclerosis and many other diseases, such as that t10,c12 CLA can reduce lipogenesis, and c9,t11-CLA has an antitumor effect, making it a health-promoting fatty acid (Fig. 1) (Chen et al. 2025; Dhar Dubey et al. 2019; George and Ghosh 2025; Gong et al. 2019; Sun et al. 2022).

Fig. 1.

Applications of the two typical conjugated linoleic acid (CLA) isomers, cis-9,trans-11-CLA (c9,t11-CLA) and trans-10,cis-12-CLA (t10, c12-CLA)

The traditional sources of CLA are based on extraction and chemical synthesis, but due to the low content of CLA in animal fats, the steps needed to obtain the product with high purity are highly elaborate, making it difficult to apply the extraction process in industrial production. Currently, industrial CLA is primarily produced by alkaline isomerization of vegetable oils, but this method produces a mixture of several isomers, resulting in a very complicated downstream separation process. There is therefore an urgent need to search for novel and efficient CLA sources. Fortunately, it was found that certain microorganisms can biosynthesize CLA (Andrade et al. 2012; Liu et al. 2025), although the yield is generally low and is not sufficient to achieve economically viable industrial production. Nevertheless, obtaining CLA through biosynthesis is a promising alternative, as the process is not only mild but also characterized by a high degree of regio- and stereoselectivity (Wu et al. 2024). In this article, we will provide a comprehensive overview of the current state of CLA biosynthesis, including the commonly used microorganisms and related mechanisms, as well as strain engineering strategies for potential industrial CLA production. Finally, future perspectives of CLA biosynthesis are discussed.

Microorganisms for the production of conjugated Linoleic acid

Table 1 summarizes the currently known microorganisms that can convert LA into CLA, most of which are anaerobic or facultative anaerobes that synthesize CLA when grown in media containing LA.

Table 1.

Summary of the known bacteria that can convert Linoleic acid into conjugated Linoleic acid

| Strains | Nos | Substrates (g/L) | Biocatalysts | Conjugated Linoleic Acid (CLA) | References | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Titer (g/L) | Conversion rate (%) | 9, 11-CLA (%) | 10, 12-CLA (%) | |||||

| Butyrivibrio fibrisolvens | A38 | Linoleic acid (0.10) | Resting cells | 0.08 | 80.0 | 95 | 5 | Kim 2003 |

| Lactobacillus acidophilus | L1 | Linoleic acid (0.20) | Living cells | 0.13 | 65.5 | 90 | 10 | Alonso et al. 2003 |

| Q16 | Linoleic acid (0.20) | Living cells | 0.06 | 30.5 | 91 | 9 | Alonso et al. 2003 | |

| AKU1137 | Linoleic acid (4.00) | Resting cells | 1.50 | 37.5 | 100 | 0 | Kishino et al. 2002 | |

| AKU1137 | Linoleic acid (5.00) | Living cells | 4.90 | 98.0 | 100 | 0 | Ogawa et al. 2001 | |

| Lactobacillus casei | E10 | Linoleic acid (0.20) | Living cells | 0.08 | 40.1 | 91 | 9 | Alonso et al. 2003 |

| E5 | Linoleic acid (0.20) | Living cells | 0.11 | 55.5 | 88 | 12 | Alonso et al. 2003 | |

| Lactobacillus plantarum | JCM1551 | Linoleic acid (4.00) | Resting cells | 2.02 | 50.5 | 100 | 0 | Kishino et al. 2002 |

| JCM1551 | Castor oil (5.00) | Living cells | 2.70 | 54.0 | 100 | 0 | Ando et al. 2004 | |

| ZS2058 | Linoleic acid (0.55) | Living cells | 0.30 | 54.5 | 56 | 44 | Yang et al. 2014 | |

| PL 62 | Linoleic acid (1.00) | Purified enzymes | 0.65 | 65.0 | 47 | 53 | Lee et al. 2007 | |

| NCUL005 | Linoleic acid (2.28) | Living cells | 0.60 | 26.4 | 32 | 68 | Zeng et al. 2009 | |

| Lactobacillus reuteri | ATCC55739 | Linoleic acid (0.55) | Living cells | 0.35 | 63.6 | 97 | 3 | Yang et al. 2014 |

| ATCC55739 | Linoleic acid (0.90) | Living cells | 0.30 | 33.3 | 59 | 41 | Lee et al. 2003b | |

| Lactobacillus breve | IAM1082 | Linoleic acid (4.00) | Resting cells | 0.55 | 13.8 | 100 | 0 | Kishino et al. 2002 |

| Bifidobacterium breve | NCFB2257 | Linoleic acid (0.55) | Living cells | 0.23 | 42.0 | 99 | 1 | Coakley et al. 2003 |

| NCFB2258 | Linoleic acid (0.55) | Living cells | 0.40 | 72.4 | 100 | 0 | Coakley et al. 2003 | |

| NCFB11815 | Linoleic acid (0.55) | Living cells | 0.22 | 39.1 | 99 | 1 | Coakley et al. 2003 | |

| NCFB8815 | Linoleic acid (0.55) | Living cells | 0.24 | 44.0 | 99 | 1 | Coakley et al. 2003 | |

| NCFB8807 | Linoleic acid (0.55) | Living cells | 0.13 | 23.3 | 99 | 1 | Coakley et al. 2003 | |

| LMC520 | Linoleic acid (0.56) | Living cells | 0.40 | 71.4 | 95 | 5 | Coakley et al. 2003 | |

| Bifidobacterium animalis | Bb12 | Linoleic acid (0.56) | Living cells | 0.17 | 30.4 | 99 | 1 | Yang et al. 2014 |

| Bifidobacterium lactis | BB12 | Linoleic acid (0.55) | Living cells | 0.17 | 30.9 | 98 | 2 | Coakley et al. 2003 |

| Enterococcus faecium | M74 | Soybean oil (10) | Living cells | 0.73 | 7.30 | 100 | 0 | Xu et al. 2006 |

| Megasphaera elsdenii | YJ-4 | Linoleic acid (0.02) | Living cells | 0.01 | 50.0 | 15 | 85 | Kim et al. 2002 |

| Pediococcus acidilactici | AKU1059 | Linoleic acid (4.00) | Resting cells | 1.40 | 35.0 | 100 | 0 | Kishino et al. 2002 |

| Propionibacterium freudennreichii | P-6 Wiesby | Linoleic acid (0.75) | Living cells | 0.27 | 35.3 | 93 | 7 | Jiang et al. 1998 |

| 9093 | Linoleic acid (0.50) | Living cells | 0.11 | 22.2 | 90 | 10 | Jiang et al. 1998 | |

| ATCC 6207 | Linoleic acid (0.10) | Living cells | 0.02 | 23.2 | 75 | 25 | Jiang et al. 1998 | |

| Propinibacterium freudenreichii subsp. shermanii | 56 | Soybean oil (10) | Living cells | 1.09 | 10.9 | 83 | 17 | Xu et al. 2006 |

| 51 | Soybean oil (10) | Living cells | 1.65 | 16.5 | 85 | 15 | Xu et al. 2006 | |

| 23 | Soybean oil (10) | Living cells | 0.81 | 8.10 | 75 | 25 | Xu et al. 2006 | |

| Propionibacterium acnes | No. 27 | Linoleic acid (0.02) | Living cells | 0.02 | 85.0 | 0 | 100 | Verhulst et al. 1987 |

Where: 9, 11-CLA represents: c9, t11-CLA and t9, t11-CLA; 10, 12-CLA represents t10, c12-CLA

Strains that primarily synthesize the c9,t11-CLA isomer

The naturally occurring microorganisms capable of synthesizing CLA include rumen bacteria, as well as species of the genera Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium, Propionibacterium, and Clostridium, which mostly generate the c9,t11-CLA isomer as the main product. Rumen bacteria are the first group of strains reported to have the ability to biosynthesize CLA, which is an intermediate product in the bioconversion of LA to produce vaccenic acid or stearic acid. Butyrivibrio fibrisolvens A38 is the most efficient strain for CLA production among rumen bacteria, with a conversion rate of nearly 40%, 95% which is c9,t11-CLA (Hunter et al. 1976; Kepler and Tove 1967). Researchers also analyzed the factors affecting the CLA conversion rate (Kim et al. 2000), such as the substrate concentration, anaerobic environment and glycolysis inhibitors (Yang et al. 2017). In addition, the activity of CLA reductase can directly affect the accumulation of CLA, as for example the CLA reductase of B. fibrisolvens TH1 can convert CLA into vaccenic acid, which in turn reduces the accumulation of CLA (Kim 2003). Conversely, B. fibrisolvens MDT-5, which does not contain a CLA reductase, has a higher CLA content (Fukuda et al. 2006).

Another group of bacteria with the ability to synthesize CLA are lactobacilli, and they are widely used in CLA biosynthesis. Several Lactobacillus species have been shown to have the ability to transform LA into CLA rich in the c9,t11-CLA isomer. Lactobacillus brevis was the first species of the genus to be shown to convert LA into CLA. Notably, immobilized L. brevis produced 5.5 times more CLA than free resting cells, while L. brevis ATCC 55,739 was found to convert LA into CLA even in vivo in humans (Liu et al. 2025). Lactobacillus plantarum is another species with a high CLA production capacity. Kishino et al. (2002) showed that the CLA yield of L. plantarum AKU1009a could reach up to 85%. While L. plantarum JCM1551 can utilize ricinoleic acid as the substrate for the synthesis of CLA, with a final product titer as high as 2.7 mg/L (Ando et al. 2004). L. plantarum ZS2058 was able to convert 54.3% of LA into CLA (Yang et al. 2014). And it was found that the concentration of resting cells, substrate concentration, yeast extract in the medium, and glucose content can affect the efficiency of CLA conversion in L. plantarum (Khosravi et al. 2015). In addition to CLA, various Lactobacillus species convert LA into 10-hydroxy-cis12-octadecenoic acid (10-HOE), 10,13-dyhydroxyl-octadecanoic acid (10,13-diHOA), and 13-hydroxy-cis9-octadecenoic acid (13-HOE), with examples including L. brevis LTH2584 (Chen et al. 2016), Lactobacillus rhamnosus LGG (Yang et al. 2013), Lactobacillus acidophilus NCFM (Yang et al. 2013), L. plantarum AKU1009a (Kishino et al. 2002, 2011a, b, 2013), L. plantarum ATCC8014 (Ortega-Anaya & Hernández-Santoyo 2015), L. plantarum ZS2058 (Chen et al. 2016)d acidophilus AKU1137 (Ogawa et al. 2001). It has also been shown that CLA generated by resting cells of L. acidophilus is mainly accumulated intracellularly (Li et al. 2011). In addition, the oxygen in the fermentation system was found to only affects the ratio between isomers and not the total amount of CLA (Lin et al. 2005).

Species of Bifidobacterium constitute another group of efficient CLA producers. Coakley et al. (2003) first reported that Bifidobacterium sp. has the ability to convert LA into CLA with a preference for the c9,t11-CLA isomer, with Bifidobacterium breve exhibiting the highest ability of CLA synthesis. Another study analyzed the ability of 150 Bifidobacterium strains to produce CLA and found four strains with biotransformation rates of more than 80% with LA, all of which were B. breve, with B. breve LMC017CLA reaching a rate of up to 90.0% (Chung et al. 2008), and it could also produce CLA with monoglycerol linoleate as the substrate, with a conversion rate of 78.8%. Gorissen et al. (2010) examined the ability of 36 strains of Bifidobacterium sp. to synthesize CLA, and the results showed that the ability of B. breve to produce CLA was significantly higher than that of other Bifidobacterium species. In addition to B. breve, B. longum could was also able to produce CLA, and the ability to synthesize CLA differed significantly between strains, e.g. using LA as the substrate, the conversion rate of B. longum DPC6320 was 43.4%, while that of B. longum DPC6315 was only 11.0% (Barrett et al. 2007; Hennessy et al. 2012). In addition, it was noted that Bifidobacterium dentium can also produce CLA, whereby B. dentium NCFB2243 reached a conversion rate of 29.0% (Gorissen et al. 2010).

In addition, some species of Propionibacterium and Clostridium are also able to produce CLA. Verhulst et al. (1987) reported for the first time that Propionibacterium species can be used for CLA production, among which P. freudenreichii subsp. freudenreichii, P. freudenreichii subsp. shermanii, and P. acidipropionici were all able to convert LA into c9,t11-CLA. Among Clostridium species, it was found that CLA was an intermediate product in the biotransformation of LA by strains that produce vaccenic acid, and the generated CLA was dominated by the c9,t11-CLA isomer when using C. bifermentans, C. sporogenes, or C. sordelli as the while-cell catalyst (Verhulst et al. 1985). Peng et al. (2007) found that C. sporogenes ATCC22762 could convert the LA into CLA when the reaction time was 30 min, at this time, CLA was dominated by c9,t11-CLA, and prolongation of the reaction resulted in a decrease of this isomer, while the content of t9,t11-CLA as well as t10,c12-CLA rose, eventually resulting in comparable titers of all three isomers.

Strains that primarily synthesize the t10,c12-CLA isomer

In contrast to c9,t11-CLA, fewer strains are able to synthetize t10,c12-CLA as the major isomer. Verhulst et al. (1987) showed that eight strains of Propionibacterium acnes (ATCC6919, ATCC6921, VPl 162, VPl 163, VPl 164, VPl 174, VPl 186, and VPl 199) can convert LA into CLA, whereby the main product was t10,c12-CLA. In addition to P. acnes, strains of Megasphaera elsdenii are also able to produce predominantly t10, c12-CLA, reaching a proportion of up to 85% (Kim et al. 2002). In addition, a few Lactobacillus strains can convert LA into CLA with t10,c12-CLA as the dominant isomer, such as L. plantarum PL 62 (Lee et al. 2007)d plantarum NCUL005 (Zeng et al. 2009).

Mechanisms for microbial conjugated Linoleic acid production

Monoenzyme catalysis system

The monoenzyme catalysis system is based on a single enzyme, i.e., LA isomerase (EC 5.2.1.5), which can produce two different CLA isomers. To date, three LA isomerases have been isolated and purified, which are derived from Butyrivibrio fibrisolvens (Kepler et al. 1966), Lactobacillus reuteri (Rosson et al. 2001), and Propionibacterium acnes (Deng et al. 2007). The first two LA isomerases modify the C12 double bond of the LA molecule to produce c9,t11-CLA (Fig. 2). They are membrane-bound proteins, unstable and highly susceptible to inactivation during purification, as well as substrate inhibition, making them unsuitable for the production of CLA by biotransformation. The LA isomerase derived from P. acnes acts on the C9 double bond of the LA molecule, with the product being t10,c12-CLA (Fig. 2). In contrast to the former two enzymes, it is an intracellular soluble protein, and is not sensitive to substrate inhibition. It is the only LA isomerase with a known crystal structure and the only one that has been successfully heterologously expressed in a variety of hosts including Escherichia coli, Lactobacillus lactis, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Yarrowia lipolytica, etc., and even some plant cells such as tobacco and rice.

Fig. 2.

The conversion of LA into CLA catalyzed by two different LA isomerases. LA, linoleic acid, CLA, conjugated linoleic acid

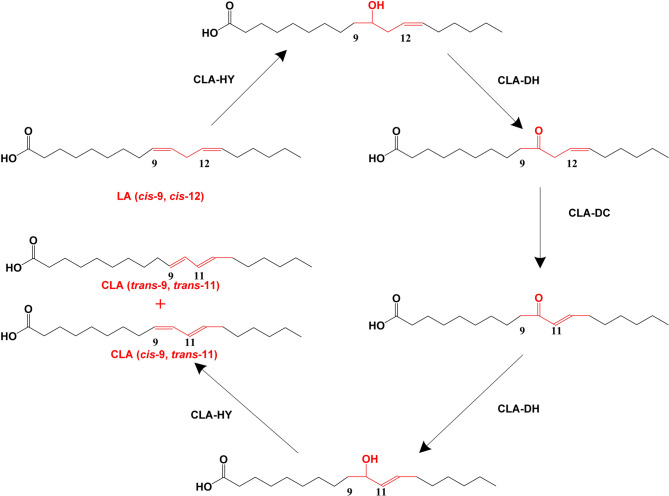

Multienzyme catalysis system

The proposed multienzyme catalysis system involves multiple enzymes for the conversion of LA into CLA (Salsinha et al. 2018), whereby the isomerization of LA requires the production of intermediate hydroxy fatty acids, while the final product of the process is mostly c9,t11-CLA and to a lesser extent t9,t11-CLA (Ogawa et al. 2001). This mechanism is commonly observed during the in vitro production of CLA using Lactobacillus as a whole-cell catalyst. In 2011, a research team in Japan identified for the first time three enzymes that constitute a complex system for the conversion of LA into CLA in L. plantarum (Kishino et al. 2011a, b). Each of the three enzymes was expressed in E. coli, with the first enzyme (CLA-HY) present in the cytosolic fraction of the bacterium, and the other two enzymes (CLA-DH and CLA-DC) located in the soluble fraction. The CLA-DH shares sequence similarity with the short-chain oxidoreductase/dehydrogenase in the genome of L. plantarum, while CLA-DC is somewhat similar to acetoacetate decarboxylase. Only when the recombinant bacteria expressing the three enzymes were mixed, and with the addition of LA combined with cofactors (NADH, FAD and NADPH), the final products c9,t11-CLA and t9,t11-CLA could be detected. Thus, CLA could not be synthesized in the absence of any of these components, suggesting that the three enzymes are elements of a constitutive multienzyme system (Kishino et al. 2011a). Therefore, the multienzyme catalysis system for the conversion of LA into CLA was proposed based on the following 5 steps: (1) CLA-HY catalyzes the hydration of LA to produce the corresponding hydroxy fatty acid; (2) CLA-DH catalyzes the oxidation of the hydroxy fatty acid to produce a ketocarbonyl fatty acid; (3) CLA-DC catalyzes the isomerization of the double bond on the ketocarbonyl fatty acid molecule to produce a conjugated enone fatty acid; (4) CLA-DH catalyzes the inverse dehydrogenation of the conjugated keto fatty acid to produce a conjugated alkenohydroxy fatty acid; (5) CLA-HY catalyzes the inverse hydration of the conjugated alkenohydroxy fatty acid to produce c9,t11-CLA and t9,t11-CLA as the end products (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Proposed reaction scheme for the conversion of LA into CLA using the multienzyme catalysis system. LA, linoleic acid; CLA, conjugated linoleic acid; CLA-HY, CLA-DH, and CLA-DC are three enzymes constituting the LA isomerase system; CLA-HY, CLA oleate hydratase; CLA-DH, CLA short-chain dehydrogenase/oxidoreductase; and CLA-DC, CLA acetoacetate decarboxylase

Strategies for conjugated Linoleic acid biosynthesis

Biotransformation using natural strains

Currently, studies using natural microorganisms to convert LA into CLA generally using the following four methods: live cell fermentation, resting cell transformation, immobilized cell biosynthesis, and pure enzymatic biocatalysis, all of which have unique sets of advantages and disadvantages (Table 2).

Table 2.

Methods for the production of conjugated Linoleic acid using natural strains

| Methods | Details | Pros and cons | Typical examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Living cell fermentation | Microbial growth and biosynthesis are coupled to each other, with growth and synthesis occurring at the same time | Easy to achieve high-density culture but cells cannot be reused |

Lactobacillus lactis (Kim and Liu 2002) Bifidobacterium sp. (Oh et al. 2003) |

| Resting cell transformation | The resting microbes cannot grow due to the lack of certain essential nutrients, but the cells are still active due to the presence of various enzyme systems | Increased reaction activity but cumbersome steps |

Propionibacterium fischeri (Rainio et al. 2001) Lactobacillus plantarum (Zhao et al. 2011) |

| Immobilized cell biosynthesis | Microbial cells with physiological functions are immobilised by certain methods and utilised as solid biocatalysts | Increased microbial cell reuse but reduced viability |

Lactobacillus reuteri (Lee et al. 2003a) Lactobacillus delbrueckii and Lactobacillus acidophilus (Lin et al. 2005) |

| Pure enzymatic biocatalysis | Microbial cells are cultured at high density, and then they are fragmented and purified to obtain pure enzymes for biocatalysis | Higher catalytic efficiency but high cost of enzyme purification |

Lactobacillus acidophilus and Propionibacterium freudenreichi (Lin et al. 2002) Lactobacillus delbrueckii (Lin 2006) |

Kim and Liu (2002) identified 14 species of Lactobacillus in fermented milk with the ability to synthesize CLA from sunflower oil, among which Lactobacillus lactis I-01 had the highest synthesis ability and produced the maximum amount of CLA when the concentration of sunflower oil was 0.1 g/L. However, when the concentration of sunflower oil was greater than 0.2 g/L, the amount of CLA produced gradually decreased. Oh et al. (2003) studied the production of CLA by fermentation with B. breve and B. pseudocatenulatum, whereby the maximum amount of biomass was reached at 30 h of incubation, and the main isomer was c9,t11-CLA, which was distributed in the supernatant, with yields of 135–160 mg/L.

Rainio et al. (2001) cultured Propionibacterium fischeri in whey-supplemented medium, after which the cells were harvested, washed and placed into phosphate buffer containing 4.0 g/L LA for resting cell biotransformation. Notably, the conversion rate reached 46%, which was the highest yield reported at that time for the synthesis of CLA using resting cell biotransformation. Zhao et al. (2011) used the freeze-thaw method to permeabilize L. plantarum A6-1 F, which was then used to produce CLA. Using phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) as the biotransformation medium, a wet cell paste concentration of 150 g/L, LA concentration of 1.5 g/L, 37 °C, and a transformation time of 2 h, the highest yield of CLA reached 275.7 mg/L, which was nearly 20% higher than without permeabilization, and the main isomer was c9,t11-CLA.

Lee et al. (2003a) immobilized Lactobacillus reuteri ATCC 55,739 on silica gel, and the transformation reaction for 1 h at an LA concentration of 500 mg/L, pH 10.5, and 55 °C produced 175 mg/L of CLA, with a conversion rate of 35%. By contrast, free washed cells incubated for 1 h under the optimal reaction conditions produced only 32 mg/mL with a conversion rate of 6.4%. Thus, the CLA conversion rate of the immobilized cells was 5.5 times higher than that of the free cells. Lin et al. (2005) immobilized Lactobacillus delbrueckii ssp. bulgaricus CCRC 14,009 and Lactobacillus acidophilus CCRC 14,079 using both chitosan and polyacrylamide materials, respectively. At pH 7.0, the CLA yield was 121 µg for polyacrylamide-immobilized cells and 51.2 µg for chitosan, while the yield for free cells was only 29.4 µg.

Because most LA isomerases are difficult to isolate and purify, have poor thermal stability, and are easily inactivated during the extraction process, Lin et al. (2002) cultured Lactobacillus acidophilus in MRS broth, collected the cells by centrifugation, and then broke the wall with lysozyme followed by ultrasonication, and then subjected the crude enzyme to salting-out and dialysis, and finally concentrated the enzyme using a membrane with a molecular mass cutoff of 100 kD, which achieved a better purification effect. Lin (2006) compared the efficiency of Lactobacillus sp. washed cells and crude enzyme for the conversion of LA into CLA. The yield of CLA synthesized by washed cells was 209 mg/L, while that of the extracted crude enzyme was 8.5 mg/L, whereby the content of the individual isomers and the total CLA content was significantly lower than that of the transformation with washed cells, which might be related to the poor stability of free LA isomerase.

Biotransformation or de novo biosynthesis using engineered strains

From the above analysis, it is clear that reliance on natural microbial cells does not allow for efficient biosynthesis of CLA. This is because the biocatalysts involved are inherently dependent on the properties of the cells, and natural microbial cells often do not fundamentally solve the problem of low catalytic efficiency due to insufficient enzyme amount and specificity. By contrast, pure enzymatic biocatalysis can solve the problem, because the products of this process are easy to separate, and the amount of enzyme can be adjusted according to the needs of the reaction, but it suffers from the high cost of enzyme purification, loss of enzyme activity during the reaction, and the complexity of operation.

For these reasons, researchers have genetically engineered more suitable host organisms to heterologously express LA isomerase from natural strains. Since the LA isomerase from P. acnes is able to synthesize 100% t10,c12-CLA isomer using LA as substrate (Deng et al. 2007), it has become a focus of research. Since P. acnes is a pathogenic microorganism that can cause diseases such as acne, it is not suitable for direct use in CLA synthesis. Therefore, researchers have attempted to heterologously express its LA isomerase-encoding gene, PaLAI, in other safer species to efficiently and exclusively biosynthesize the t10,c12-CLA isomer (Table 3). Two studies from 2007 heterologously expressed the PaLAI gene in Escherichia coli and Lactobacillus lactis (Deng et al. 2007; Rosberg-Cody et al. 2007), whereby the conversion of LA into CLA reached 50% and 40%, respectively. Moreover, the yield of t10,c12-CLA in L. lactis reached 0.2 g/L, and it reduced the viability of SW480 rectal cancer cells to 7.9%. Hornung et al. (2005) heterologously expressed PaLAI in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and tobacco seedlings, demonstrating the substrate preference of PaLAI. Since rice is a richer source of free fatty acids, Kohno-Murase et al. (2006) heterologously expressed PaLAI in rice seedlings and found that the content of the product t10,c12-CLA reached 1.3% of the total rice lipids. Moreover, this genetically modified rice was used as feed in animal experiments to study the physiological effect of t10,c12-CLA, and also has the potential to be used as a nutraceutical product in the future.

Table 3.

Engineering strategies for conjugated Linoleic acid biotransformation or de Novo biosynthesis using engineered strains

| Chassis | Target genes | Methods | Substrates | Products | Productions | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tobacco | oPaLAI | Heterologous expression | Linoleic acid | t10, c12-CLA | 15.30% of total FAs | Hornung et al. 2005 |

| Rice | oPaLAI | Heterologous expression | – | t10, c12-CLA | 1.30% of total FAs | Kohno-Murase et al. 2006 |

| Escherichia coli | PaLAI | Heterologous expression | Linoleic acid | t10, c12-CLA | 0.08 g/L | Deng et al. 2007 |

| Lactococcus lactis | PaLAI | Heterologous expression | Linoleic acid | t10, c12-CLA | 0.20 g/L | Rosberg-Cody et al. 2007 |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae | oPaLAI | Heterologous expression | Linoleic acid | t10, c12-CLA | 5.70% of total FAs | Hornung et al. 2005 |

| Trichosporon oleaginosus | oPaLAI | Heterologous expression | – | t10, c12-CLA | 2.60% of total FAs | Görner et al. 2016 |

| Mortierella alpina | oPaLAI | Heterologous expression | – | t10, c12-CLA | 1.20% of total FAs, 0.03 g/L | Hao et al. 2015 |

| Yarrowia lipolytica | oPaLAI | Heterologous expression | Glucose | t10, c12-CLA | 5.90% of total FAs | Zhang et al. 2012 |

| Yarrowia lipolytica | MaFAD2 and oPaLAI | Co-expression | Soybean oil | t10, c12-CLA | 44.00% of total FAs, 4.00 g/L | Zhang et al. 2013 |

| Yarrowia lipolytica | MaFAD2 and oPaLAI | Co-expression | Glucose | t10, c12-CLA | 10.00% of total FAs | Zhang et al. 2013 |

| Yarrowia lipolytica | oPaLAI and ΔPEX10 | Genetically modified | Safflower seed oil | t10, c12-CLA | 7.40 g/L | Zhang et al. 2022 |

| Yarrowia lipolytica | ΔPOX1–6, ΔDGA1, ΔDGA2, ΔARE1, ΔLRO1, YlFAD2 and oPaLAI | Genetically modified | Soybean oil | t10, c12-CLA | 6.50% of total FAs, 0.302 g/L | Imatoukene et al. 2017 |

| Glucose | 0.052 g/L | |||||

| Yarrowia lipolytica |

MaDGA1, MaFAD2 and PaLAI |

Heterologous expression | Glycerol | t10, c12-CLA | 0.130 g/L | Wang et al. 2019 |

total FAs, total fatty acids. Δ followed by letters refers to gene knockout. PaLAI, linoleic acid isomerase gene from P. acnes; oPaLAI, codon-optimized linoleic acid isomerase gene from P. acnes; MaDGA1, diacylglycerol transferase 1 gene of M. alpina; MaFAD2, Δ12 desaturase gene of M. alpina; PEX10, peroxisome biosynthesis factor 10 gene; POX1–6, peroxisomal acyl-CoA oxidase 1–6 genes; DGA1, diacylglycerol acyltransferase 1 gene; DGA2, diacylglycerol acyltransferase 2 gene; ARE1, Acyl-CoA cholesterol acyltransferase gene; LRO1, phospholipid: diacylglycerol acyltransferase gene; YlFAD2, Δ12 desaturase gene of Y. lipolytica

To further achieve efficient biosynthesis of CLA, the researchers successively codon optimized PaLAI and expressed it in the oleaginous yeast Yarrowia lipolytica using a strong promoter (Zhang et al. 2013), complemented by high expression of the FAD2 gene derived from Mortierella alpina which encodes the Δ12 desaturase catalyzing the conversion of oleic acid into LA. Using oleic acid-rich soybean oil as the substrate for whole-cell catalysis, they achieved a final yield of the target product, t10,c12-CLA of 4.0 g/L. Subsequently, they further improved the efficiency of biotransformation by cell permeabilization treatment to reduce product inhibition of the whole-cell catalyst (Zhang et al. 2016). After disrupting the β-oxidation pathway of Y. lipolytica to reduce the degradation of the substrate and the product by the whole-cell catalyst, when using safflower seed oil enriched in LA as the substrate, the yield of the target product t10,c12-CLA reached 7.4 g/L (Zhang et al. 2022). This successful case provides an effective strategy for high-level CLA production using Y. lipolytica.

However, although these methods can achieve high CLA yields, the presence of CLA in the form of free fatty acids can cause cytotoxicity and result in the termination of the reaction. Moreover, the biocatalysts are not recyclable, which increases the cost. Since Y. lipolytica has the ability to biosynthesize fatty acids de novo, studies also attempted to engineer it for the de novo biosynthesis of CLA from simple carbon sources (Zhang et al. 2012). In order to achieve this, researchers successively knocked out key genes of the β-oxidation pathway in Y. lipolytica (POX1-6) to block the degradation of fatty acids, overexpressed a codon-optimized PaLAI gene, and achieved CLA biosynthesis from glucose as well as glycerol, but the yields were not high enough, reaching only 0.05 and 0.13 g/L, respectively (Imatoukene et al. 2017; Wang et al. 2019). This is because the studies did not manage to regulate the fatty acid fractions accumulated by Y. lipolytica to increase the proportion of LA, and the PaLAI-encoded LA isomerase can only use free LA as substrate, whereas most of the fatty acids produced by Y. lipolytica accumulate in the form of triglycerides, resulting in the inaccessibility of the substrate for LA isomerase. This is another reason for the low yield of de novo CLA biosynthesis. In addition, the intermediate product free LA and the end product CLA are both cytotoxic to a certain extent, while the researchers did not try to enhance the fatty acid tolerance of the yeast chassis, illustrating the third reason for the low yield of de novo biosynthesis of the target product.

Research needs and future directions

CLA has beneficial physiological activities, including antiobesity, anti-atherosclerotic, and even anticancer effects, making it a promising compound not only for functional foods, but also in clinical practice. Therefore, it is of great significance to strengthen the research on the synthesis of CLA. Currently, most CLA is produced by chemical isomerization, which requires harsh reaction conditions and results in a complex mixture of isomers, making it difficult to isolate a single isomer for applications in food and medicine. By contrast, biosynthesis of CLA has greater advantages. In this article, we have provided a comprehensive summary of the current status and research progress on sustainable alternative CLA biosynthesis methods, including potential production strains, biosynthesis mechanisms, and improving CLA biosynthesis by means of genetic engineering. Looking ahead, in order to further improve the efficiency and yield of CLA biosynthesis, making this process more economical and competitive, future research work can be carried out in the following aspects (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

The proposed future research directions in the biosynthesis of CLA. LA, linoleic acid; CLA, conjugated linoleic acid

First, the mechanism of CLA biosynthesis deserves further study, especially the differences between various bacterial strains, in order to lay a foundation for the establishment of more efficient biotransformation processes. On the basis of the mechanistic studies, the preparation and effective expression of biocatalysts, as well as the enhancement of the biotransformation process are important research aims. In addition, constructing microbial cell factories for the de novo biosynthesis of CLA from glucose is also an important goal. This requires strengthening synthetic biology research, including chassis cell selection, as well as upgrading the “design-build-test-learn” cycle to systematically and iteratively develop and optimize microbial cell factories for the de novo biosynthesis of CLA. Finally, one of the major challenges to the economics of CLA biosynthesis is the development of efficient and economical downstream processing technologies, which will accelerate its commercial application. Generally, there are two biosynthetic isomers of CLA, namely c9,t11-CLA and t10,c12-CLA. Although the product spectrum is much simpler than that of chemical synthesis methods, the two isomers may have unknown physiological effects when applied as a mixture. Therefore, developing efficient downstream processing techniques for CLA isomer separation is crucial for its pharmaceutical applications.

In conclusion, CLA, which has notable physiological activities including antiobesity and anticancer effects, is attracting increasing attention in the field of healthcare. With the design and/or discovery of novel production strains, the biosynthesis approach will offer significant opportunities to further decrease CLA production costs, which will greatly increase its application prospects.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author contributions

L.L. and X.-J.J. conceived the project. X.-J.J. and Q.Z. supervised the project. L.L., M.-L.S., K.W., J.G. and X.-J.J. wrote, checked, and modified the manuscript. L.L., X.-J.J. and Q.Z. designed and drew the figures.

Funding

This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (22178173), the Jiangsu Basic Research Center for Synthetic Biology (BK20233003), the Project for the Introduction of Innovative and Leading Talents of Jiangxi Province (jxsq2023102175), and the State Key Laboratory of Materials-Oriented Chemical Engineering (SKL-MCE-24A10).

Data availability

Not applicable.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

The authors agreed to publish this article.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Xiao-Jun Ji, Email: xiaojunji@njtech.edu.cn.

Quanyu Zhao, Email: zhaoqy@njtech.edu.cn.

References

- Alonso L, Cuesta EP, Gilliland SE (2003) Production of free conjugated Linoleic acid by Lactobacillus acidophilus and Lactobacillus casei of human intestinal Origin1. J Dairy Sci 86:1941–1946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ando A, Ogawa J, Kishino S, Shimizu S (2004) Conjugated Linoleic acid production from castor oil by Lactobacillus plantarum JCM 1551. Enzym Microb Technol 35:40–45 [Google Scholar]

- Andrade JC, Ascencao K, Henriques SSM, Pinto J, Rocha-Santos TAP, Freitas AC, Gomes AMP (2012) Production of conjugated Linoleic acid by food-grade bacteria: A review. Int J Dairy Technol 65:467–481 [Google Scholar]

- Barrett E, Ross RP, Fitzgerald GF, Stanton C (2007) Rapid screening method for analyzing the conjugated Linoleic acid production capabilities of bacterial cultures. Appl Environ Microbiol 73:2333–2337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen YY, Liang NY, Curtis JM, Gänzle MG (2016) Characterization of linoleate 10-Hydratase of Lactobacillus plantarum and novel antifungal metabolites. Front Microbiol 7:1561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Xiao J, Zhu X, Fan X, Peng M, Mu Y, Wang C, Xia L, Zhou M (2025) Exploiting conjugated Linoleic acid for health: a recent update. Food Funct 16:147–167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung SH, Kim IH, Park HG, Kang HS, Yoon CS, Jeong HY, Choi NJ, Kwon EG, Kim YJ (2008) Synthesis of conjugated Linoleic acid by human-derived Bifidobacterium breve LMC 017: utilization as a functional starter culture for milk fermentation. J Agric Food Chem 56:3311–3316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coakley M, Ross RP, Nordgren M, Fitzgerald G, Devery R, Stanton C (2003) Conjugated Linoleic acid biosynthesis by human-derived Bifidobacterium species. J Appl Microbiol 94:138–145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng M-D, Grund AD, Schneider KJ, Langley KM, Wassink SL, Peng SS, Rosson RA (2007) Linoleic acid isomerase from Propionibacterium acnes: purification, characterization, molecular cloning, and heterologous expression. Appl Biochem Biotechnol 143:199–211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhar Dubey KK, Sharma G, Kumar A (2019) Conjugated linolenic acids: implication in cancer. J Agric Food Chem 67:6091–6101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda S, Suzuki Y, Murai M, Asanuma N, Hino T (2006) Isolation of a novel strain of Butyrivibrio fibrisolvens that isomerizes Linoleic acid to conjugated Linoleic acid without hydrogenation, and its utilization as a probiotic for animals. J Appl Microbiol 100:787–794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George J, Ghosh AR (2025) Conjugated Linoleic acid in cancer therapy. Curr Drug Deliv 22:450–464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong M, Hu Y, Wei W, Jin Q, Wang X (2019) Production of conjugated fatty acids: A review of recent advances. Biotechnol Adv 107454 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Gorissen L, Raes K, Weckx S, Dannenberger D, Leroy F, De Vuyst L, De Smet S (2010) Production of conjugated Linoleic acid and conjugated linolenic acid isomers by Bifidobacterium species. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 87:2257–2266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Görner C, Redai V, Bracharz F, Schrepfer P, Garbe D, Brück T (2016) Genetic engineering and production of modified fatty acids by the non-conventional oleaginous yeast trichosporon oleaginosus ATCC 20509. Green Chem 18:2037–2046 [Google Scholar]

- Hao D, Chen H, Hao G, Yang B, Zhang B, Zhang H, Chen W, Chen YQ (2015) Production of conjugated Linoleic acid by heterologous expression of Linoleic acid isomerase in oleaginous fungus Mortierella alpina. Biotechnol Lett 37:1983–1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hennessy AA, Barrett E, Paul Ross R, Fitzgerald GF, Devery R, Stanton C (2012) The production of conjugated α-Linolenic, γ-Linolenic and stearidonic acids by strains of bifidobacteria and propionibacteria. Lipids 47:313–327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornung E, Krueger C, Pernstich C, Gipmans M, Porzel A, Feussner I (2005) Production of (10E,12Z)-conjugated Linoleic acid in yeast and tobacco seeds. Biochimica et biophysica acta (BBA) -. Mol Cell Biology Lipids 1738:105–114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter WJ, Baker FC, Rosenfeld IS, Keyser JB, Tove SB (1976) Biohydrogenation of unsaturated fatty acids. Hydrogenation by cell-free preparations of Butyrivibrio fibrisolvens. J Biol Chem 251:2241–2247 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imatoukene N, Verbeke J, Beopoulos A, Idrissi Taghki A, Thomasset B, Sarde C-O, Nonus M, Nicaud J-M (2017) A metabolic engineering strategy for producing conjugated Linoleic acids using the oleaginous yeast Yarrowia lipolytica. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 101:4605–4616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang J, Björck L, Fondén R (1998) Production of conjugated Linoleic acid by dairy starter cultures. J Appl Microbiol 85:95–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kepler C, Tove S (1967) Biohydrogenation of unsaturated fatty acids. 3. Purification and properties of a linoleate delta-12-cis, delta-11-trans-isomerase from Butyrivibrio fibrisolvens. J Biol Chem 242:5686–5692 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kepler CR, Hirons KP, McNeill JJ, Tove SB (1966) Intermediates and products of the biohydrogenation of Linoleic acid by Butyrivibrio fibrisolvens. J Biol Chem 241:1350–1354 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khosravi A, Safari M, Khodaiyan F, Gharibzahedi SMT (2015) Bioconversion enhancement of conjugated Linoleic acid by Lactobacillus plantarum using the culture media manipulation and numerical optimization. J Food Sci Technol 52:5781–5789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim YJ (2003) Partial Inhibition of biohydrogenation of Linoleic acid can increase the conjugated Linoleic acid production of Butyrivibrio fibrisolvens A38. J Agric Food Chem 51:4258–4262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y, Liu R (2002) Increase of conjugated Linoleic acid content in milk by fermentation with lactic acid bacteria. J Food Sci 67:1731–1737 [Google Scholar]

- Kim YJ, Liu RH, Bond DR, Russell JB (2000) Effect of Linoleic acid concentration on conjugated Linoleic acid production by Butyrivibrio fibrisolvens A38. Appl Environ Microbiol 66:5226–5230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim YJ, Liu RH, Rychlik JL, Russell JB (2002) The enrichment of a ruminal bacterium (Megasphaera elsdenii YJ-4) that produces the trans‐10, cis‐12 isomer of conjugated Linoleic acid. J Appl Microbiol 92:976–982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishino S, Ogawa J, Omura Y, Matsumura K, Shimizu S (2002) Conjugated Linoleic acid production from Linoleic acid by lactic acid bacteria. J Amer Oil Chem Soc 79:159–163 [Google Scholar]

- Kishino S, Ogawa J, Yokozeki K, Shimizu S, Bioscience (2011a) Biotechnol Biochem 75:318–322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishino S, Park S-B, Takeuchi M, Yokozeki K, Shimizu S, Ogawa J (2011b) Novel multi-component enzyme machinery in lactic acid bacteria catalyzing C = C double bond migration useful for conjugated fatty acid synthesis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 416:188–193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishino S, Takeuchi M, Park S-B, Hirata A, Kitamura N, Kunisawa J, Kiyono H, Iwamoto R, Isobe Y, Arita M (2013) Polyunsaturated fatty acid saturation by gut lactic acid bacteria affecting host lipid composition. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 110:17808–17813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kohno-Murase J, Iwabuchi M, Endo-Kasahara S, Sugita K, Ebinuma H, Imamura J (2006) Production of trans-10, cis-12 conjugated Linoleic acid in rice. Transgenic Res 15:95–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SO, Hong GW, Oh DK (2003a) Bioconversion of Linoleic acid into conjugated Linoleic acid by immobilized Lactobacillus reuteri. Biotechnol Progress 19:1081–1084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SO, Kim CS, Cho SK, Choi HJ, Ji GE, Oh DK (2003b) Bioconversion of Linoleic acid into conjugated Linoleic acid during fermentation and by washed cells of Lactobacillus reuteri. Biotechnol Lett 25:935–938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K, Paek K, Lee HY, Park JH, Lee Y (2007) Antiobesity effect of trans-10,cis‐12‐conjugated Linoleic acid‐producing Lactobacillus plantarum PL62 on diet‐induced obese mice. J Appl Microbiol 103:1140–1146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J-Y, Zhang L-W, Du M, Han X, Yi H-X, Guo C-F, Zhang Y-C, Luo X, Zhang Y-H, Shan Y-J (2011) Effect of tween series on growth and cis-9, trans-11 conjugated Linoleic acid production of Lactobacillus acidophilus F0221 in the presence of bile salts. Int J Mol Sci 12:9138–9154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin TY (2006) Conjugated Linoleic acid production by cells and enzyme extract of Lactobacillus delbrueckii ssp. Bulgaricus with additions of different fatty acids. Food Chem 94:437–441 [Google Scholar]

- Lin TY, Lin CW, Wang YJ (2002) Linoleic acid isomerase activity in enzyme extracts from Lactobacillus Acidophilus and Propionibacterium Freudenreichii ssp. Shermanii. J Food Sci 67:1502–1505 [Google Scholar]

- Lin TY, Hung TH, Cheng TSJ (2005) Conjugated Linoleic acid production by immobilized cells of Lactobacillus delbrueckii ssp. Bulgaricus and Lactobacillus acidophilus. Food Chem 92:23–28 [Google Scholar]

- Liu X-X, Izzat S, Wang G-Q, Xiong Z-Q, Ai L-Z (2025) Research progress on biosynthesis and regulation of conjugated Linoleic acid in lactic acid Bacteria. Biotechnol Appl Chem. 10.1002/bab.2737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa J, Matsumura K, Kishino S, Omura Y, Shimizu S (2001) Conjugated Linoleic acid accumulation via 10-hydroxy-12-octadecaenoic acid during microaerobic transformation of Linoleic acid by Lactobacillus acidophilus. Appl Environ Microbiol 67:1246–1252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh D-K, Hong G-H, Lee Y, Min S, Sin H-S, Cho SK (2003) Production of conjugated Linoleic acid by isolated Bifidobacterium strains. World J Microbiol Biotechnol 19:907–912 [Google Scholar]

- Ortega-Anaya J, Hernández-Santoyo A (2015) Functional characterization of a fatty acid double-bond hydratase from Lactobacillus plantarum and its interaction with biosynthetic membranes. Biochim Et Biophys Acta (BBA) - Biomembr 1848:3166–3174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng SS, Deng M-D, Grund AD, Rosson RA (2007) Purification and characterization of a membrane-bound Linoleic acid isomerase from Clostridium sporogenes. Enzym Microb Technol 40:831–839 [Google Scholar]

- Rainio A, Vahvaselkä M, Suomalainen T, Laakso S (2001) Reduction of linoleic acid inhibition in production of conjugated linoleic acid by Propionibacterium freudenreichii ssp. shermanii. 47:735–740 [PubMed]

- Rosberg-Cody E, Johnson MC, Fitzgerald GF, Ross PR, Stanton C (2007) Heterologous expression of Linoleic acid isomerase from Propionibacterium acnes and anti-proliferative activity of Recombinant trans-10, cis-12 conjugated Linoleic acid. Microbiology 153:2483–2490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosson RA, Grund A, Deng M-D, Sanchez-Riera F (2001) Linoleate isomerase. United States Patent, p 6743609

- Salsinha AS, Pimentel LL, Fontes AL, Gomes AM, Rodríguez-Alcalá LM (2018) Microbial production of conjugated Linoleic acid and conjugated linolenic acid relies on a multienzymatic system. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 82:e00019–e00018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y, Hou X, Li L, Tang Y, Zheng M, Zeng W, Lei X (2022) Improving obesity and lipid metabolism using conjugated Linoleic acid. Veterinary Med Sci 8:2538–2544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhulst A, Semjen G, Meerts U, Janssen G, Parmentier G, Asselberghs S, Van Hespen H, Eyssen H (1985) Biohydrogenation of Linoleic acid by Clostridium Sporogenes, Clostridium bifermentans, Clostridium sordellii and Bacteroides Sp. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 1:255–259 [Google Scholar]

- Verhulst A, Janssen G, Parmentier G, Eyssen H (1987) Isomerization of polyunsaturated long chain fatty acids by propionibacteria. Syst Appl Microbiol 9:12–15 [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Xia Q, Wang F, Zhang Y, Li X (2019) Modulating heterologous pathways and optimizing culture conditions for biosynthesis of trans-10, cis-12 conjugated Linoleic acid in Yarrowia lipolytica. Molecules 24:1753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu C, Chen H, Mei Y, Yang B, Zhao J, Stanton C, Chen W (2024) Advances in research on microbial conjugated Linoleic acid bioconversion. Prog Lipid Res 93:101257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu S, Boylston TD, Glatz BA (2006) Effect of inoculation level of Lactobacillus rhamnosus and yogurt cultures on conjugated Linoleic acid content and quality attributes of fermented milk products. J Food Sci 71:C275–C280 [Google Scholar]

- Yang B, Chen H, Song Y, Chen YQ, Zhang H, Chen W (2013) Myosin-cross-reactive antigens from four different lactic acid bacteria are fatty acid hydratases. Biotechnol Lett 35:75–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang B, Chen H, Gu Z, Tian F, Ross RP, Stanton C, Chen YQ, Chen W, Zhang H (2014) Synthesis of conjugated Linoleic acid by the linoleate isomerase complex in food-derived lactobacilli. J Appl Microbiol 117:430–439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang B, Gao H, Stanton C, Ross RP, Zhang H, Chen YQ, Chen H, Chen W (2017) Bacterial conjugated Linoleic acid production and their applications. Prog Lipid Res 68:26–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng Z, Lin J, Gong D (2009) Identification of lactic acid bacterial strains with high conjugated Linoleic acid-Producing ability from natural sauerkraut fermentations. J Food Sci 74:M154–M158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B, Rong C, Chen H, Song Y, Zhang H, Chen W (2012) De Novo synthesis of trans-10, cis-12 conjugated Linoleic acid in oleaginous yeast Yarrowia lipolytica. Microb Cell Fact 11:51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B, Chen H, Li M, Gu Z, Song Y, Ratledge C, Chen YQ, Zhang H, Chen W (2013) Genetic engineering of Yarrowia lipolytica for enhanced production of trans-10, cis-12 conjugated Linoleic acid. Microb Cell Fact 12:70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B, Song Y, Chen H, Zhang H, Chen W (2016) Production of trans-10, is-12-conjugated Linoleic acid using permeabilized whole-cell biocatalyst of Yarrowia lipolytica. Biotechnol Lett 38:1917–1922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B, Ni L, Tang X, Chen X, Hu B (2022) Engineering the β-oxidation pathway in Yarrowia lipolytica for the production of trans-10, cis-12-conjugated linoleic acid. J Agric Food Chem 70:8377–8384 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Zhao H-W, Lv J-P, Li S-R (2011) Production of conjugated linoleic acid by whole-cell of Lactobacillus plantarum A6-1F. Biotechnol Biotec Equip 25:2266–2272

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.