Abstract

The PA-PB1 interface of the influenza polymerase is an attractive site for antiviral drug design. In this study, we designed and synthesized a mini-library of indazole-containing compounds based on rational structure-based design to target the PB1-binding interface on PA. Biological evaluation of these compounds through a viral yield reduction assay revealed that compounds 27 and 31 both had a low micromolar range of the half maximal effective concentration (EC50) values against A/WSN/33 (H1N1) (8.03 μmol/L for 27; 14.6 μmol/L for 31), while the most potent candidate 24 had an EC50 value of 690 nM. Compound 24 was effective against different influenza strains including a pandemic H1N1 strain and an influenza B strain. Mechanistic studies confirmed that compound 24 bound PA with a Kd which equals to 1.88 μmol/L and disrupted the binding of PB1 to PA. The compound also decreased the lung viral titre in mice. In summary, we have identified a potent anti-influenza candidate with potency comparable to existing drugs and is effective against different viral strains. The therapeutic options for influenza infection have been limited by the occurrence of antiviral resistance, owing to the high mutation rate of viral proteins targeted by available drugs. To alleviate the public health burden of this issue, novel anti-influenza drugs are desired. In this study, we present our discovery of a novel class of indazole-containing compounds which exhibited favourable potency against both influenza A and B viruses. The EC50 of the most potent compounds were within low micromolar to nanomolar concentrations. Furthermore, we show that the mouse lung viral titre decreased due to treatment with compound 24. Thus our findings identify promising candidates for further development of anti-influenza drugs suitable for clinical use.

Key words: Influenza, Anti-influenza compounds, Compound library synthesis, Lead discovery and optimization, Polymerase inhibitors, PA-PB1 inhibitors, Indazole-containing compounds, Pharmacodynamics study

Graphical abstract

A novel class of indazole-containing compounds which exhibited favourable potency against both influenza A and B viruses was discovered, identify promising candidates for further development of anti-influenza drugs suitable for clinical use.

1. Introduction

The influenza infection is caused by the influenza A, B or C virus (IAV, IBV or ICV respectively). Human infections caused by ICV generally lead to mild common cold symptoms1,2. However, IAV and IBV infections can lead to upper respiratory symptoms and may be fatal. Influenza infections can claim up to 290,000 to 650,000 lives annually3, according to the World Health Organization. Human infections caused by zoonotic IAV strains are occasionally recorded and usually result in high mortality rates. The infamous examples of zoonotic IAV infection are caused by the avian H5N1 strain and the pandemic swine H1N1 strain recorded in 1997 and 2009 respectively.

The replication and transcription of influenza viruses are performed by their RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRP) protein architecture, which is composed of three subunits, namely the polymerase acidic protein (PA), polymerase basic subunit 1 (PB1) and polymerase basic subunit 2 (PB2)4. The PB1 subunit forms the core structure of this heterotrimeric complex and houses the catalytic active site responsible for RNA synthesis. The PA and PB2 are attached to PB1 for designated functions. The PB2 subunit binds to host capped-RNA while the PA subunit cleaves it to generate primers for transcription via a process called ‘cap-snatching’4. The correct folding and assembly of the RdRP complex is hence crucial for the replication and transcription of the virus.

The treatment of influenza infection has been hindered by the possible occurrence of antiviral resistance worldwide. The M2 ion channel inhibitors amantadine and rimantadine are no longer recommended as first-line anti-influenza therapeutics due to widespread occurrence of resistance5. It is also alarming that resistant strains have been identified from clinical isolates which show reduced susceptibility to available drugs such as oseltamivir, a neuraminidase inhibitor, or baloxavir, a polymerase inhibitor6, 7, 8, 9, 10. Oseltamivir-resistance is characterized by numerous mutations on the neuraminidase protein such as the H275Y mutation, while baloxavir-resistance is conferred by the I38T mutation on the PA subunit. More recently, it was reported that an E198K charge reversion on the PA protein renders baloxavir two-to six-fold less effective11. As a result, novel therapeutic options against the virus are required.

This PA-PB1 binding interface has attracted attention for antiviral discovery, owing to its importance in RdRP assembly. The binding of these two subunits relies on the extreme N-terminal helix (PB1–N) on PB1 and the C-terminal domain of PA (PA-C) which serves as the major anchor for PB1. From the earliest complex structure of PA-C in complex with PB1–N and the various RdRP crystal structures, the complex was formed by inserting PB1–N into a highly hydrophobic groove of PA-C. The PA hydrophobic groove, defined by four helices, resembles an opening of a mouth-shaped cavity4,12. Three groups of hydrophobic residues could be identified, namely L666/F710, M595/V636/L640/W619 and W706/F411, which resided on PB1. Among these residues, M595, L666, F411, W706 and F710 interacted with PB1 residues via side-chain hydrophobic interactions. A peptide corresponding to the N-terminal sequence of PB1 effectively disrupted PA-PB1 interaction and inhibited viral replication13.

Numerous attempts have been made to disrupt this interaction using small molecular inhibitors. Earlier, Muratore et al. used in silico screening to identify hit compounds with a low micromolar activity level against influenza (EC50 12.2–22.5 μmol/L)14. Zhang et al. identified a tetrazole compound which inhibited influenza A with an EC50 value ranging from 1.2 to 4.5 μmol/L and influenza B with an EC50 value around 1 μmol/L15. Later, through high-throughput screening (HTS), they identified two PA-PB1 inhibitors with an EC50 value that was effective against various influenza strains, ranging from 0.93 to 7.54 μmol/L16. Recently, Mizuta et al. optimized a PA-PB1 interface-targeting compound PA-49 with an EC50 value of 0.57 μmol/L and obtained derivatives around 9-fold more potent17. However, the overall efficacy of PA-PB1 inhibitors identified so far is suboptimal18.

Several small molecule inhibitors against the PA-C-PB1-N of the influenza virus have been identified19,20 using a high throughput screening (HTS) approach, which included a benzofurazan lead compound (Fig. 1) with the best anti-PA-C-PB1-N activity (IC50 = 45 μmol/L) and inhibited viral replication at a micromolar level (EC50 = 1 μmol/L). However, all compounds reported therein had cytotoxicity with 50% cytotoxic concentration (CC50) values ranging from 20 to 80 μmol/L, leading to small selectivity indices. Computational studies between the active inhibitors and target interface demonstrated that the benzofurazan scaffold exhibited pi–pi stacking interaction with W70619, and formed hydrogen bond with Q408 involving the oxygen atom of the furazan group. Furthermore, the nitro group formed an electrostatic interaction with K643. Based on these previous discoveries, we designed a mini-library of 31 compounds consisting of three series. For the first series of compounds, an indazole skeleton was introduced to generate the pi–pi stacking interaction. In addition, a nitrogen atom was designed to replace the oxygen atom for hydrogen bonding with Q408. A 2-amino benzamide moiety was introduced to improve the antiviral activities and reduce the cytotoxicity of these target compounds. The target compounds 1–8 exhibited a significant reduction in cytotoxicity, but anti-influenza activities were also hampered. Further, through scaffold hopping, an α,β-unsaturated carbonyl moiety was introduced to the second series of compounds, 9–18, to replace the 2-amino benzamide group. The indazole skeleton was maintained, and cinnamic acid derivatives with antiviral activities were introduced. To further reduce cytotoxicity, we eventually retained the parent indazole backbone, and the α,β-unsaturated carbonyl moiety in the second series of compounds was replaced with a thiourea segment to obtain the third series of compounds, 19–31.

Figure 1.

Strategy of structure optimization of target compounds.

We then tested the bioactivities of these target compounds against influenza and identified a potent compound 24 which is effective against both IAV and IBV. The molecular mechanism of compound 24 was then confirmed biochemically. This compound represents a promising lead for further translation to clinical use.

2. Results

2.1. Chemistry and synthesis of mini-library

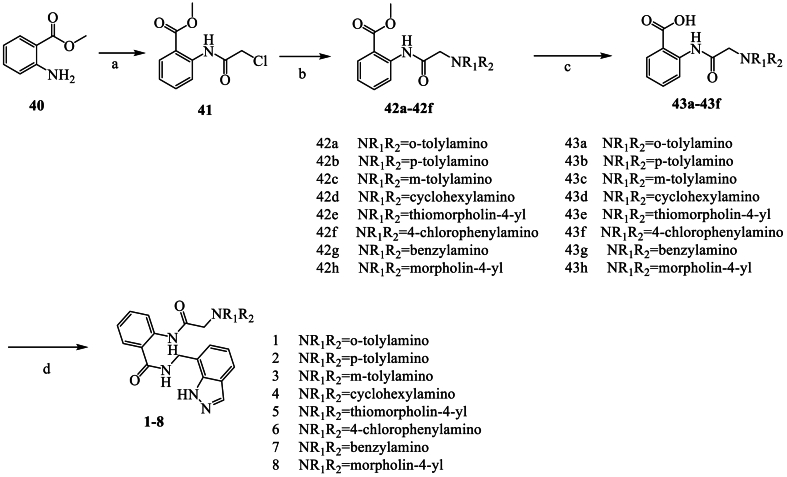

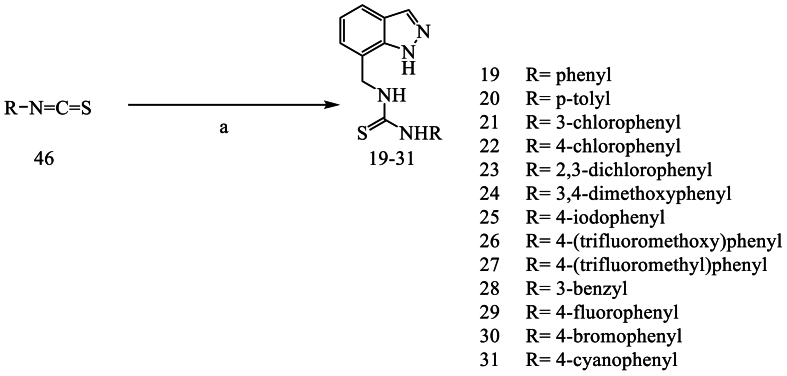

The synthetic protocols for the novel designed compounds 1–31 are outlined in Scheme 1, Scheme 2, Scheme 3, Scheme 4. The key intermediate (1H-indazol-7-yl)methanamine (39) was synthesized in seven steps with 3-methyl-2-nitrobenzoic acid as the starting material. Afterwards, the target compounds 1–8 were obtained using 39 and 43a‒43f, which were obtained in three steps with methyl 2-aminobenzoate as the starting material. Compounds 9–18 were synthesized using 39 and cinnamic acid derivatives (44). Compounds 19–31 were obtained using 39 and isothiocyanate derivatives (45).

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of the key intermediate 39. Reagents and conditions: a) MeOH, H2SO4, room temperature (r.t.); b) Fe, NH4Cl, EtOH, r.t.; c) potassium acetate, acetic anhydride, toluene, isoamyl nitrite, 110 °C; d) LiAlH4, THF, 0 °C; e) MnO2, CH2Cl2, DMF, r.t.; f) 1H-indazole-7-carbaldehyde, hydroxylamine hydrochloride, NaHCO3, H2O, r.t.; g) LiAlH4, THF, 0 °C.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of compounds 1–8. Reagents and conditions: a) Chloroacetyl chloride, K2CO3, CH2Cl2, r.t.; b) K2CO3, amines, THF, 66 °C; c) KOH, H2O, 100 °C; d) 39, HATU, DIPEA, DMF, r.t.

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of compounds 9–18. Reagents and conditions: a) 39, HATU, DIPEA, DMF, r.t.

Scheme 4.

Synthesis of compounds 19–31. Reagents and conditions: a) 39, TEA, THF, r.t.

2.2. Initial screening of bioactivities of 31 compounds

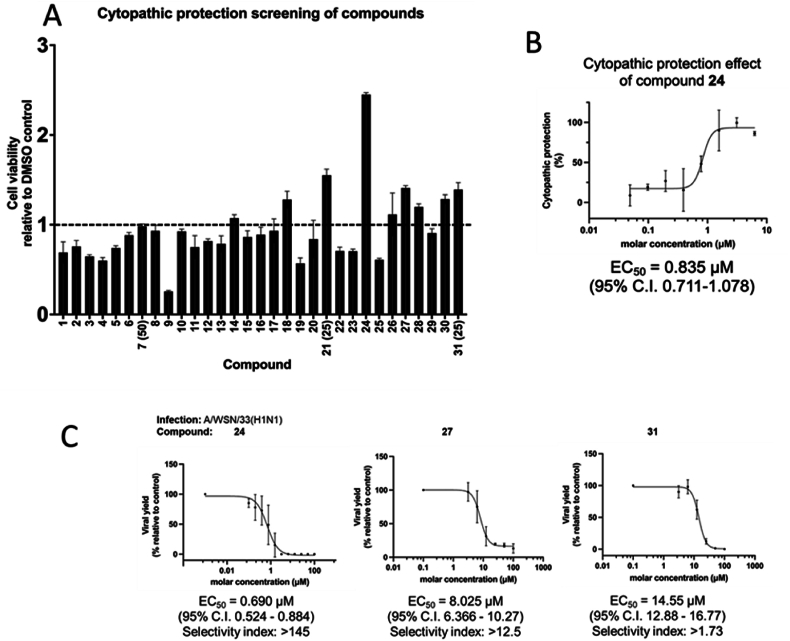

The cytotoxicity of the compounds in MDCK cells was evaluated using 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay. As shown in Table 1, 28 out of 31 compounds tested remained non-toxic at 100 μmol/L which was the highest concentration tested. The viral yield reduction and cytopathic effect (CPE) reduction assays were used for a preliminary evaluation of the anti-influenza activities of tested compounds. Compounds 24, 27, and 31 suppressed the growth of the A/WSN/33(H1N1) virus in MDCK cells at 100 μmol/L, exhibiting a >90% reduction in viral yield. Furthermore, these three compounds protected MDCK cells from cell death upon influenza virus infection, as shown in Fig. 2A. The half maximal effective concentration (EC50) of the best-performing compound, 24, was calculated to be 835 nmol/L (Fig. 2B). We then established the EC50 values of the three best-performing compounds using the viral yield assay. In our system, the potent positive chemical baloxavir marboxil (BxM) had an EC50 value of 0.95 nmol/L against A/WSN/33(H1N1) (Supplementary Table 1, Supporting Information Fig. S1). As shown in Fig. 2C, the EC50 of compounds 24, 27, and 31 against A/WSN/33(H1N1) were 690 nmol/L, 8.025 μmol/L, and 14.55 μmol/L respectively, leading to selectivity indices (CC50/EC50) of >145, >12.5 and > 1.73, respectively. Hence, we confirmed the anti-influenza bioactivities of this group of compounds. We refrained from using compound 31 for further studies because the low selectivity index of the compound indicated possible interference of bioactivity by toxicity. Compound 24 demonstrated better potency and selectivity index than 27 and was, therefore, subjected to further investigation. To further evaluate the bioactivity of compound 24 against different representative influenza strains, the viral yield reduction assay was used to establish the EC50 values for its inhibition of the virus strains A/HK/1/68(H3N2), A/California/7/09(H1N1pdm), B/Florida/04/2006, and A/PR/8/34(H1N1), which were 540 nmol/L, 746 nmol/L, 230 nmol/L, and 247 nmol/L, respectively. These values, shown in Fig. 3, demonstrated that the compound is active against all tested strains, with good selective index values larger than 100. The EC50 values for the positive chemical BxM are listed in Supplementary Table 1.

Table 1.

Chemical structures, cytotoxicity and percentages of virus inhibition in virus inhibition assay of compounds 1–31 was tested in MDCK cells. Compounds demonstrating no virus yield inhibition (%-inhibition <2%) are denoted as not significant. N.S.: not significant.

| Chemical | Structure | CC50 in MDCK in μmol/L | %-inhibition in viral yield reduction assay screening |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |  |

>100 | 25.0% |

| 2 |  |

>100 | 10.2% |

| 3 |  |

>100 | 18.6% |

| 4 |  |

>100 | N.S. |

| 5 |  |

>100 | N.S. |

| 6 |  |

>100 | N.S. |

| 7 |  |

>50 | N.S. |

| 8 |  |

>100 | N.S. |

| 9 |  |

>100 | N.S. |

| 10 |  |

>100 | N.S. |

| 11 |  |

>100 | N.S. |

| 12 |  |

>100 | 37.3% |

| 13 |  |

>100 | 30.5% |

| 14 |  |

>100 | 48.4% |

| 15 |  |

>100 | 44.1% |

| 16 |  |

>100 | 48.2% |

| 17 |  |

>100 | 33.9% |

| 18 |  |

>100 | N.S. |

| 19 |  |

>100 | 25.0% |

| 20 |  |

>100 | N.S. |

| 21 |  |

>25 | 37.5% |

| 22 |  |

>100 | 16.9% |

| 23 |  |

>100 | N.S. |

| 24 |  |

>100 | 99.9% |

| 25 |  |

>100 | 74.4% |

| 26 |  |

>100 | N.S. |

| 27 |  |

>100 | 94.9% |

| 28 |  |

>100 | N.S. |

| 29 |  |

>100 | N.S. |

| 30 |  |

>100 | N.S. |

| 31 |  |

>25 | 99.9% |

Figure 2.

(A) Cytopathic effect reduction screening of compounds 1–31. Bar chart shows viability of infected MDCK cells upon compound treatment, compared to DMSO control. Error bars represent standard deviation (n = 3). All compounds were tested at 100 μmol/L unless stated otherwise in brackets. (B) For compound 24 which outperformed other candidates, the EC50 in cytopathic effect reduction was 835 nM. Error bars represent the standard deviation of each data point on the dose–response curve (n = 3). The EC50 value was determined to be 835 nmol/L with 95% confidence interval shown in bracket. (C) Compounds 24, 27 and 31 suppressed growth of A/WSN/33(H1N1) virus with EC50 of 690 nmol/L, 8.025 and 14.55 μmol/L respectively. Error bars represent standard deviation of each data point on the dose–response curve (n ≥ 3). The EC50 values were shown with the respective 95% confidence interval in brackets.

Figure 3.

EC50 values of compound 24 against A/HK/1/68(H3N2), A/California/7/09(H1N1pdm), B/Florida/04/2006, and A/PR/8/34(H1N1) viruses were determined. Error bars represent the standard deviation of each data point on the dose–response curve (n ≥ 3). The EC50 values are shown with the respective 95% confidence interval in brackets. Compound 24 demonstrated good potencies against all four tested strains with selectivity indices >100.

2.3. Mechanistic investigation of compound 24

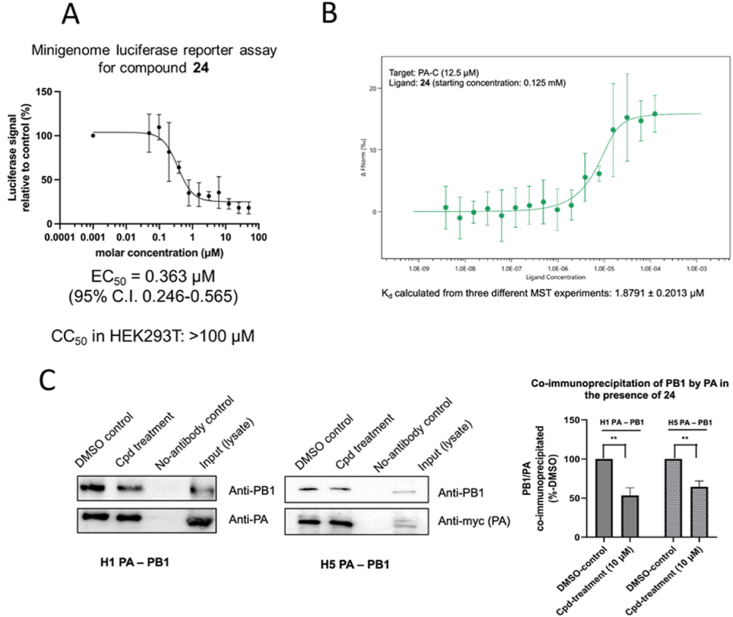

We used compound 24 as the representative compound to study the mode of action of this class of indazole-derivatives. As these compounds were developed based on a docking model onto the PA protein, we first used a minigenome luciferase reporter assay to test whether compound 24 could suppress the activity of the influenza ribonucleoprotein complex. In brief, a minireplicon system using the promoters of influenza and its RdRP was transfected into HEK293T cells to drive the expression of a luciferase reporter gene which serves as an indicator of ribonucleoprotein activity. Our results indicated that compound 24 inhibited ribonucleoprotein activity, as reflected by the luciferase signal, with an EC50 value of 363 nmol/L, which was in the same order of magnitude as 142 nmol/L for BxM (Fig. 4A and Supporting Information Fig. S1). This was consistent with its performance in viral yield reduction and cytopathic effect reduction assays. The reporter assay hence confirmed that compound 24 interfered with the proper function of the polymerase leading to suppression of replication and/or transcription.

Figure 4.

(A) Compound 24 was tested for the capability to inhibit polymerase activity with a minigenome luciferase reporter assay. The CC50 of the compound in HEK293T cells was pre-determined to be > 100 μmol/L. The EC50 of compound 24 to H1 polymerase was found to be 363 nM. Error bars on dose–response curve represent the standard deviation of each data point from n = 4. (B) Binding of compound 24 to PA-C protein was determined by microscale thermophoresis. The dissociation constant (Kd) was 1.88 ± 0.2 μmol/L (mean ± SD from three MST experiments) (C) Co-immunoprecipitation experiments showed that compound 24 could disrupt the formation of H1 and H5 PA-PB1 heterodimeric complex. Only 53.5% ± 7.9% (for H1) or 64.5% ± 6.2% (for H5) of PA-PB1 complex was co-immunoprecipitated compared to DMSO control. Values were obtained from triplicate experiments and represented by mean ± SD. ∗∗P < 0.01 Two-tailed Student's t-test.

The binding affinity of this compound with PA-C was determined through microscale thermophoresis (MST), where an H1-origin PA-C protein was titrated against a 2-fold dilution of compound 24. It was demonstrated by MST that the dissociation constant (Kd) of 24-PA-C binding was 1.88 μmol/L (Fig. 4B). This value was in the same order of magnitude as the EC50 values shown above and confirmed that compound 24 was still bound to PA-C despite the chemical modifications on the lead compound. Nevertheless, if compound 24 targets the PB1 binding interface on PA-C, we questioned whether it could effectively hinder the binding between PA and PB1. To this end, we used co-immunoprecipitation to demonstrate the effect of compound 24 on PA-PB1 interaction (Fig. 4C). In the presence of 10 μmol/L of compound 24, PA-PB1 binding in an H1 setting was reduced to 53.5%. We also performed the co-immunoprecipitation assay in the context of an H5 polymerase, and in this case, the binding was reduced to 64.5% upon compound treatment. Collectively, the PB1 binding interface on PA-C should be, at the very least, one of the binding sites for compound 24. This binding should contribute to the disruption of PA-PB1 complex formation and the proper functioning of the ribonucleoprotein complex. Moreover, our results also indicated that the compound should be effective against H5 strains, apart from the H1 and H3 strains we tested.

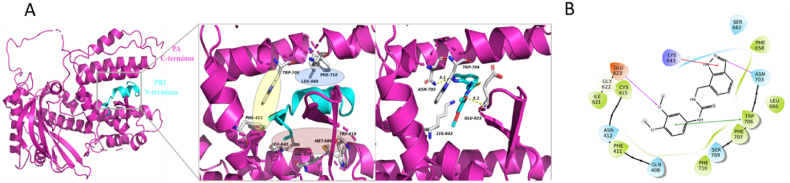

2.4. Molecular interaction between compound 24 and PA

To delineate how compound 24 binds onto PA in more detail, and to shed light on the structure–activity relationship of this class of compounds, we performed both molecular docking and molecular simulation experiments. According to Liu and Yao21, and the crystal structure solved earlier12, the PB1-binding groove is defined by three hydrophobic regions. The first hydrophobic region is centred on residues W706 and F411, the second one is defined by F710 and L666, and the third one includes L640, V636, M595, and W619 (Fig. 5A, left and middle panels). Compound 24 was docked onto PA-C (PDB 3CM8) using Schrödinger's Glide docking protocol. The ligand was situated in a binding pocket defined by E623, K643, N703 and W706 (Fig. 5A, right panel), with a glide score of −5.725 kcal/mol, which overlapped with the PB1 peptide binding site. The ligand was stabilized by extensive interactions with the protein core. Hydrogen bonds were identified between the ligand and E623 (main chain) and N703. Furthermore, W706 exhibited pi–pi stacking with the phenyl substituent (Fig. 5B). A cation–pi interaction was identified between K643 and the indazole ring. Notably, W706 is itself a critical residue involved in PB1-binding via pi–pi stacking.

Figure 5.

(A) Left panel: the structure of PA-C/PB1–N complex (PDB ID: 3CM8). Middle panel: The first hydrophobic region for PB1 binding is centred on residues W706 and F411 (yellow circle). The second region is defined by F710 and L666 (blue circle), and the third region includes L640, V636, M595, and W619 (pink circle). Right panel: Compound 24 (cyan, stick) could be docked into a groove defined by residues E623, K643, N703, and W706 (white, stick) on PA-C (PDB 3CM8, magenta, cartoon). Shown is the lowest energy conformer. (B) Schematic diagram showing the protein–ligand interactions. E623 (main chain) and N703 were involved in hydrogen bonding (pink arrows). W706 was involved in pi–pi stacking (green line); K643 was involved in pi–cation interaction (red arrow).

A 100 ns molecular dynamic simulation was performed to evaluate the trajectory of ligand binding (Fig. 6A). The fact that the protein and ligand root-mean-square-deviations (RMSD) over time converged towards the end of the simulation indicated stable complex formation between the protein and the ligand. The protein‒ligand system reached equilibrium at around 45 ns, after which the protein-ligand complex fluctuated only within a narrow range of RMSD around 4 Å. Secondary structure elements were monitored throughout the simulation. Except for unstructured regions, the root-mean-square-fluctuation (RMSF) of residues remained below 1.5 Å, indicative of the absence of protein unfolding upon ligand binding. Protein-ligand contacts were also monitored, revealing that, as expected from the chemical structure of 24 and the hydrophobic nature of the putative binding site, the primary interactions were hydrophobic interactions, including cation–pi interaction. Notably, L666, W706, F707 and F710 were all involved in hydrophobic interactions during the simulation. Residues E623 and S709 were predicted to form hydrogen bonds with the ligand, while E623, K643, S662, and N703 were among the residues involved in water bridges. Collectively, our molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulation studies pinpointed E623, K643, L666, R673, N703, W706, and F710 as essential residues for the binding of compound 24.

Figure 6.

(A) Root-mean-square-deviation (RMSD) over time plots for apo-PA-C protein (magenta) and 24-PA-C complex (blue). Convergence of RMSDs indicates stable complex formation. The complex reached equilibrium at around 45 ns. (B) Root-mean-square-fluctuation (RMSF) plots of the apo-protein (cyan) and the complex (purple) during simulation with inlet figure showing the secondary structure of the protein (orange: helices; blue: strands). Most residues fluctuated within a minimal RMSF of below 1.5 Å. The more flexible residues remained on unstructured regions. (C) Protein‒ligand interactions in the course of molecular simulation presented as Interactions Fraction, indicating the percentage of time where a specific type of interaction was maintained. As shown, K643 and F710 contributed most to the interaction.

To validate the protein‒compound interaction, a thermal shift assay was performed using wild-type H1 PA-C or PA-C K643A and Q408A recombinant mutants. K643 was chosen for further investigation because its importance had been demonstrated in both docking and molecular dynamics simulation. Q408A, which had not interacted with the ligand, and was chosen as a control. The melting temperatures (Tm) of these proteins were determined in the presence or absence of compound 24 (Supporting Information Fig. S2). Binding was indicated by a shift in the Tm of the protein upon compound treatment. Treatment of PA-C with DMSO (control) resulted in a single Tm of 38.4 °C. Treatment with compound 24 resulted in a broad melt curve (Supporting Information Fig. S1) with two close melt peaks at 55.9 and 60.9 °C. As shown in Table 2, treatment with compound 24 on the PA-C Q408A recombinant mutant resulted in changes in the Tm of +8.7 and +13.1 °C, leading to two broad peaks similar to those in the wild type. Hence ligand binding was not abolished by this mutation and Q408 should have limited contribution to ligand binding. The increase in Tm in PA-C and PA-C Q408A indicated a stabilization effect on the protein upon ligand binding, which was in line with molecular simulation (Fig. 6B). This was understandable as the ligand binding site should be stabilized by the PB1 peptide when in biological context. In contrast, treatment with compound 24 had a limited effect on the Tm of the K643A mutant (ΔTm = +0.6 °C), implying that ligand binding was abolished upon the mutation of K643. Hence, K643 should play a role in incorporating ligand 24 onto the binding site. These results from the thermal shift assay further support our docking model and molecular simulation, which showed the involvement of K643, but not Q408, in ligand binding (Fig. 6C).

Table 2.

Melting temperature of PA-C and variants in the presence and absence of compound 24. Standard deviations were calculated from at least n = 4.

| Protein/ligand | Melting temperature (Tm), oC, mean ± SD | Change in melting temperature (ΔTm)), oC |

|---|---|---|

| PA-C wild type/DMSO control | 38.4 ± 0.3 | Peak 1: +17.5 Peak 2: +22.5 |

| PA-C wild type/24 | Peak 1: 55.9 ± 1.7 Peak 2: 60.9 ± 1.7 |

|

| PA-C K643A/DMSO control | 50.8 ± 0.8 | ‒0.6 |

| PA-C K643A/24 | 50.2 ± 1.9 | |

| PA-C Q408A/DMSO control | 42.8 ± 0.13 | Peak 1: +8.7 Peak 2: +13.1 |

| PA-C Q408A/24 | Peak 1: 51.5 ± 1.6 Peak 2: 55.9 ± 0.6 |

To further validate the importance of residue K643 in compound binding, we repeated the minigenome luciferase reporter assay using a PA plasmid encoding a K643A variant of the protein. The EC50 of compound 24 against polymerase with PA K643A was 2.59 μmol/L (Fig. 7 and Supporting Information Fig. S1), indicating a roughly 7-fold drop in sensitivity to the compound. Hence, we have functionally demonstrated the involvement of K643 in holding onto compound 24.

Figure 7.

A PA K643A variant was used to repeat minigenome luciferase reporter assay. EC50 of compound 24 to H1 polymerase harvesting K643A PA was 2.59 μmol/L. Error bars on dose–response curve represent standard deviation of each data point from at least three independent experiments.

2.5. Compound 24 reduced lung viral titre in mice

To evaluate the in vivo efficacy of compound 24, we treated A/PR/8/34(H1N1)-infected mice with the compound (800 mg/kg/day) and monitored their lung viral titre. The compound was first tested to show no acute toxicity to mice (Supporting Information Fig. S3A). Our data then indicated that the lung viral titre was suppressed to 33% of the untreated group on day 4 post-infection. Moreover, the lung index improved upon treatment with compound 24 (Fig. 8), to a level similar to that in oseltamivir acid (65 mg/kg/day) treatment. These results further demonstrated that compound 24 targeted the influenza virus and shortened the time of viral shedding. However, we observed no significant change in the mean survival time of infected mice (Supporting Information Fig. S3B). Collectively, compound 24 still demonstrated promising in vivo potency against the influenza virus and holds good potential for clinical use after further optimization.

Figure 8.

(A) Lung indices of mice receiving compound 24 treatment were improved at day 4 post-infection. Oseltamivir acid was used as a positive control. (B) Viruses were recovered from lung tissues and titred by plaque assay. Improvement in lung viral titre in terms of plaque forming unit per lung (PFU/lung) was observed, despite a higher dose of compound 24 than oseltamivir acid being necessary. In (A) and (B), ∗∗∗∗P < 0.0001, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗P < 0.05. P-values were obtained by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Dunnett's post hoc test.

3. Discussion

In this study, we screened and tested the bioactivities against the influenza virus of a group of indazole-containing compounds. Among the 31 compounds tested, the best-performer exhibited activities against different strains of influenza viruses with sub-nanomolar EC50 values. Using representative compound 24, we demonstrated direct binding onto the PA C-terminal domain with MST. As such, the compound could interfere with PA-PB1 binding and inhibit ribonucleoprotein activity effectively. This class of compounds targets the PB1 binding interface on the PA protein. Molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulation studies revealed amino acid residues that were important for the compound to bind onto PA-C, and the result was validated using a thermal shift assay. The in vivo efficacy was also confirmed in the mouse model.

The bioactivity of compound 24 was superior to that of other PA-PB1 small molecule inhibitors reported in literature18, and was at least comparable to that of available FDA-approved RdRP inhibitors such as favipiravir (T-705), which has an EC50 that ranges between 190 nmol/L to 22 μmol/L against different strains22. This compound demonstrated similar activity to compound 24 in the viral yield reduction assay against A/WSN/33(H1N1) and A/PR/8/34(H1N1) at 1.57 and 1.32 μmol/L, respectively. It also inhibited polymerase activity at an EC50 of 441 nmol/L (Supplementary Table 1, Supporting Information Fig. S1). Furthermore, many available antivirals have been primarily designed to target IAV so that the efficacy against IBV becomes suboptimal. For example, according to Mishin et al., the only FDA-approved PA inhibitor, baloxavir, exhibits 5- to 10- fold decrease in potency against influenza B strains23. Our data showed that compound 24 is equivalently effective against IBV. As IBV infection can be fatal, especially in children and the elderly, the fact that compound 24 can circumvent the issue of decreased potency in IBV treatments renders the compound particular pharmacological values for further development.

For the compounds to elicit their antiviral effect, we expected that PA-PB1 binding would be disrupted, which was later confirmed by our co-immunoprecipitation experiment. According to previous reports, disrupting PA-PB1 heterodimer formation would lead to cytoplasmic retention of these proteins24,25, so a proper ribonucleoprotein would not be formed. The consequence of this would be a drop in ribonucleoprotein activity level, which was also proven by our minigenome luciferase reporter assay. Affinity studies confirmed that the compound could bind to the PA-C protein with a Kd of 1.88 μmol/L. Although the numerical value of Kd was around 2.7-times lower than the observed EC50 against the A/WSN/33(H1N1) virus, they are within the same order of magnitude. Furthermore, considering that the Kd was established in an in vitro setting using a purified protein domain during the experiment, the data could be regarded as consistent with each other. Nevertheless, we cannot rule out the possibility that the compound may target a secondary binding site on the ribonucleoprotein components.

Our docking model identified K643 as a key residue to hold onto the compound. In contrast, another polar residue near the groove, Q408, was not involved in any interaction. This was in line with the results of our thermal shift assay where compound treatment caused a shift in melting temperature for both the wild-type and Q408A PA-C protein, but K643A abolished such a shift in melting temperature upon compound treatment. Three hydrophobic residues, L666, F710, and R673 were critical for PB1 binding as reported in the literature12. In our molecular dynamic simulation, all of these residues were involved in hydrophobic interactions (including cation–pi interaction) with the ligand. These same interactions were, however, not shown in docking. This could be expected as molecular docking showed the lowest energy steady-state binding, while molecular dynamics simulation revealed interactions over the trajectory of 100 ns.

As PA-PB1 interactions are highly conserved among different influenza sub-types, it is not surprising that compound 24 was effective against various influenza A and B strains. Surveying available structures from the Protein Databank, the PA-PB1 interaction site exhibits high similarity in IAV, IBV and ICV (Supporting Information Fig. S4). As pinpointed by molecular simulation, E623, K643, N703 and W706 were essential for binding to compound 24. These residues have the phenotype of T618, K639, S699, and W702 in IBV, respectively. Thus, K643/K639 and W706/W702 are conserved and polarity is preserved for E623/T618 and N703/S699. S699 in IBV should replace N703 in hydrogen bonding, while E623-T618 polymorphism should not affect ligand binding as main chain interaction was involved at this position. Compounds 19–27 exhibited better antiviral activities than 1–8 as demonstrated by the viral yield reduction assay. Among compounds 19–31, the antiviral activities of compounds with substituents (such as 3,4-dimethoxy, 4-trifluoromethoxy, 4-trifluoromethyl, 4-fluoro, or 4-cyano) in the terminal aromatic ring were significantly better than those of unsubstituted compounds. Compound 24 exhibited the best antiviral activity according to the CPE assay and viral yield reduction assay. The structure–activity relationship of these compounds could be concluded as follows: (1) the antiviral activities of thiourea derivatives were significantly better than those of the other two series of compounds. (2) Phenyl substitution on the thiourea segment is superior to benzyl substitution in terms of antiviral activities. (3) Better antiviral activities could be observed when the benzene ring was 4-substituted, and the steric volume of the substituent was relatively large. (4) Compound 24 with di-substitutions on the benzene ring at 3,4 positions exhibited the best antiviral activities. These observations were generally supported by the molecular docking model. For example, key interactions between E623 and W706 with the phenyl moiety in compound 24 could be disrupted if a benzyl was used in lieu of it due to conformational and distance restraints. Compared to an unsubstituted phenyl ring (19), compound 24 exhibited superior activity as the 3-methoxy substitution provided an additional anchor for binding.

Finally, the efficacy of the compound was tested in mice with a mouse-adapted A/PR/8/34(H1N1) virus. While the compound suppressed viral growth in the lungs, we observed that even at 800 mg/kg/day, the compound was ineffective in improving the survival of infected mice, as indicated by a continuous weight loss until day 10 when we were obliged to sacrifice them. In contrast, only 65 mg/kg/day of oseltamivir acid completely restored survival in the positive-control group. The discrepancy between cell line and in vivo experiments could be due to a short half-life of the compound in mice and possibly a suboptimal dosage design. Although 800 mg/kg/day was unlikely causing acute toxicity to mice, further investigation to establish the complete pharmacokinetic and toxicity profile of the compound would be worthwhile. Nevertheless, improvement of lung index and reduction of lung viral titre indicated that compound 24 could effectively suppress viral growth even in an in vivo environment.

4. Conclusions

Taking all data together, we conclude that we have identified an indazole-containing compound, 24, which effectively suppresses the influenza A and B viruses by targeting the PA-PB1 interface and is suitable for further pharmacokinetic optimization.

5. Experimental

5.1. Synthetic procedures

The melting points (m.p.) were determined using an X-4 digital melting point apparatus and were uncorrected. Mass spectra (MS) were recorded on an Agilent Technologies 6530 Accurate-Mass Q-TOF Mass Spectrometer (Agilent, Santa Clara, USA). 1H NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker 400 MHz NMR spectrometer (Bruker, Faellanden, Switzerland) with tetramethylsilane (TMS) as an internal standard and DMSO-d6 or CDCl3 as the solvent, chemical shifts (δ values), and coupling constants (J values) are reported in ppm and Hz, respectively.

All solvents and reagents were obtained from commercial sources and used without further purification.

5.1.1. Preparation of (1H-indazol-7-yl)methanamine (39)

5.1.1.1. Preparation of methyl 3-methyl-2-nitrobenzoate (33)

3-Methyl-2-nitrobenzoic acid (4.34 g, 24.00 mmol) in methanol (200 mL) was added to a 250 mL round-bottom flask. The mixture was stirred slowly at ambient temperature. Then, H2SO4 (1.2 mL, 40.00 mmol) was added and the mixture was refluxed for 48 h. Subsequently, the solvent was evaporated to afford a crude residue. Aqueous NaHCO3 water was added to pH 8−9. The mixture was filtered to afford methyl 3-methyl-2-nitrobenzoate (4.00 g), yield in 85.0%; m.p.: 221.1–222.5 °C; ESI-MS m/z: 196.0 ([M+H]+).

5.1.1.2. Preparation of methyl 2-amino-3-methylbenzoate (34)

Methyl 3-methyl-2-nitrobenzoate (4.00 g, 20.50 mmol) in ethanol (100 mL) was added to a 250 mL round-bottom flask, and the mixture was stirred slowly at ambient temperature. Then, Fe (5.74 g, 82.00 mmol) and NH4Cl (4.39 g, 84.00 mmol) were added and stirred for 5 min. Subsequently, water (5 mL) was added and refluxed for 5 h. The mixture was filtered to afford methyl 2-amino-3-methylbenzoate (3.00 g), yield in 89.0%; m.p.: 71.1–72.5 °C; ESI-MS m/z: 166.0 ([M+H]+).

5.1.1.3. Preparation of methyl 1H-indazole-7-carboxylate (35)

A solution of methyl 2-amino-3-methylbenzoate (5.50 g, 32.72 mmol), potassium acetate (5.00 g, 49.08 mmol), acetic anhydride (0.96 g, 98.16 mmol) in methylbenzene (50 mL) was added to a 250 mL round-bottom flask and refluxed for 0.5 h. Then, isoamyl nitrite (7.70 g, 65.44 mmol) was added and refluxed for 24 h. The mixture was filtered and the solvent was evaporated to afford methyl 1H-indazole-7-carboxylate26 (4.80 g), yield in 83.3%; m.p.: 83.1‒82.6 °C; ESI-MS m/z: 177.0 ([M+H]+).

5.1.1.4. Preparation of (1H-indazol-7-yl)methanol (36)

LiAlH4 (0.86 g, 22.72 mmol) in tetrahydrofuran (THF) (20 mL) was added to a 100 mL round-bottom flask in an ice water bath to afford suspension. Then, a solution of methyl 1H-indazole-7-carboxylate (2.00 g, 11.36 mmol) in THF (20 mL) was added and stirred for 2 h. Subsequently, water (3 mL) was added to quench the reaction and the mixture was dried with anhydrous sodium sulfate. The mixture was filtered and the solvent was evaporated to afford (1H-indazol-7-yl)methanol (1.00 g), yield in 60.0%; m.p.: 71.1–72.5 °C; ESI-MS m/z: 132.1 ([M-OH] +).

5.1.1.5. Preparation of 1H-indazole-7-carbaldehyde (37)

A solution of (1H-indazol-7-yl)methanol (1.30 g, 8.78 mmol) and MnO2 in CH2Cl2/DMF (1: 150 mL) was added to a 100 mL round-bottom flask and stirred for 6 h at ambient temperature. Then, the mixture was filtered and the solvent was evaporated. Water (50 mL) and ethyl acetate (50 mL) were added and the reaction mixture was stirred for 1 h. Then, the organic phase was washed with saturated brine (10 mL) and dried with anhydrous sodium sulfate. The mixture was filtered and the solvent was evaporated to afford 1H-indazole-7-carbaldehyde27 (0.70 g), yield in 70.3%; m.p.: 98.1–99.5 °C; ESI-MS m/z: 147.0 ([M+H]+).

5.1.1.6. Preparation of 1H-indazole-7-carbaldehyde oxime (38)

A solution of hydroxylamine hydrochloride (0.62 g, 8.90 mmol) and NaHCO3 (0.87 g, 10.34 mmol) in H2O (10 mL) was added to a 50 mL round-bottom flask and stirred for 20 min at ambient temperature. Then, 1H-indazole-7-carbaldehyde (0.66 g, 4.50 mmol) in ethanol (20 mL) was added and stirred for 4 h at ambient temperature. The mixture was filtered and the solvent was evaporated to afford 1H-indazole-7-carbaldehyde oxime (0.50 g), yield in 68.5%; m.p.: 99.1–100.2 °C; ESI-MS m/z: 162.2 ([M+H]+).

5.1.1.7. Preparation of (1H-indazol-7-yl)methanamine (39)

1H-Indazole-7-carbaldehyde oxime (0.55 g, 3.41 mmol) in THF (30 mL) was added to a 50 mL round-bottom flask. Then, LiAlH4 (0.26 g, 6.85 mmol) was added slowly and refluxed for 2 h. Subsequently, water (3 mL) was added to quench the reaction. The mixture was filtered and the solvent was evaporated to afford (1H-indazol-7-yl)methanamine (0.30 g), yield in 85.7%; m.p.: 102.1–103.5 °C; ESI-MS m/z: 148.1 ([M+H]+).

5.1.2. Preparation of 2-(2-aminoacetamido)benzoic acid derivatives (1–8)

5.1.2.1. Preparation of methyl 2-(2-chloroacetylamino) benzoate (41)

A solution of methyl o-aminobenzoate (10.00 g, 0.10 mmol) and K2CO3 (18.00 g, 0.10 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (60 mL) was added to a 250 mL round-bottom flask. Chloroacetyl chloride in CH2Cl2 (50 mL) was added dropwise in an ice water bath and the solution was stirred for 1 h at ambient temperature. Then, water (100 mL) was added. The organic phase was washed with saturatedbrine (10 mL) and dried with anhydrous sodium sulfate. The mixture was filtered and the solvent was evaporated to afford methyl 2-(2-chloroacetylamino) benzoate (20.51 g), yield in 90.6%; m.p.: 122.1–123.5 °C; ESI-MS m/z: 343.1 ([M+H]+).

5.1.2.2. Preparation of 2-(2-aminoacetamido)benzoic acid derivatives (43)

A solution of methyl 2-(2-chloroacetylamino) benzoate (2.00 g, 8.80 mmol), K2CO3 (3.65 g, 26.40 mmol) and amines (10.56 mmol) in THF (70 mL) was added to a 100 mL round-bottom flask and the solution was refluxed for 24 h. Then, the mixture was filtered and the solvent was evaporated to afford methyl 2-(2-aminoacetamido)benzoate derivatives (42a‒42f). Subsequently, a solution of methyl 2-(2-aminoacetamido)benzoate derivatives (8.81 mmol) and KOH (3.65 g, 26.43 mmol) in H2O (10 mL) and ethanol (30 mL) was added to a 100 mL round-bottom flask and the solution was refluxed for 3 h. The solvent was evaporated, and the mixture was acidified by acetic acid to pH 5−6. The mixture was filtered to afford 2-(2-aminoacetamido)benzoic acid.

-

(1)

2-[2-(o-tolylamino)acetamido]benzoic acid (43a). White solid; yield in 72.0%; m.p.: 265.1–266.2 °C; ESI-MS m/z: 285.1 ([M+H]+).

-

(2)

2-[2-(p-tolylamino) acetamido]benzoic acid (43b). White solid; yield in 67.2%; m.p.: 241.5–242.5 °C; ESI-MS m/z: 285.1 ([M+H]+).

-

(3)

2-[2-(m-tolylamino)acetamido]benzoic acid (43c). White solid; yield in 66.4%; m.p.: 235.6–236.1 °C; ESI-MS m/z: 285.1 ([M+H]+).

-

(4)

2-[2-(cyclohexylamino)acetamido]benzoic acid (43d). White solid; yield in 67.9%; m.p.: 241.5–242.2 °C; ESI-MS m/z: 277.2 ([M+H]+).

-

(5)

2-[2-(thiomorpholinyl)acetamino]benzoic acid (43e). White solid; yield in 59.3%; m.p.: 231.2–231.2 °C; ESI-MS m/z: 281.1 ([M+H]+).

-

(6)

2-{2-[(4-chlorophenyl)amino]acetamido}benzoic acid (43f). White solid; yield in 69.6%; m.p.: 245.6–246.1 °C; ESI-MS m/z: 305.1 ([M+H]+).

-

(7)

2-[2-(benzylamino)acetamido]benzoic acid (43g). White solid; yield in 88.3%; m.p.: 205.4–206.8 °C; ESI-MS m/z: 314.2 ([M+H]+).

-

(8)

2-{2-[2-(morpholino)acetamido}benzoic acid (43h). White solid; yield in 75.5%; m.p.: 220.4.6–222.4 °C; ESI-MS m/z: 394.2 ([M+H]+).

5.1.2.3. Preparation of N-[(1H-indazol-7-yl)methyl]-2-(2-aminoacetamido)benzamide derivatives (1–8)

A solution of 2-(2-aminoacetamido)benzoic acid derivatives (3 mmol) and 2-(7-azabenzotriazol-1-yl)-N,N,N′,N′-tetramethyluronium hexafluorophosphate (HATU, 1.40 g, 3.60 mmol) in N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF, 30 mL) was stirred at ambient temperature for 1 h. Then, a solution of (1H-indazol-7-yl)methanamine (0.53 g, 3.60 mmol) and N,N-diisopropylethylamine (DIPEA, 0.58 g, 4.50 mmol) in DMF (10 mL) was added and the mixture was stirred at ambient temperature for 24 h. Water (100 mL) and ethyl acetate (20 mL) were added and the reaction mixture was stirred for 1 h. Then, the organic phase was washed with saturated brine (10 mL) and dried with anhydrous sodium sulfate. Subsequently, the solvent was evaporated to afford a crude residue. The crude residue was purified through chromatography on a silica gel column using CH3OH/CH2Cl2 (1/150) as an eluent to yield N-[(1H-indazol-7-yl)methyl]-2-(2-aminoacetamido)benzamide derivatives28 (1–8).

N-[(1H-Indazol-7-yl)methyl]-2-[2-(o-tolylamino)acetamido]benzamide (1): white solid; yield in 76.5%; m.p.: 246.6–247.0 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 13.06 (s, 1H), 11.83 (s, 1H), 9.17–9.16 (m, 1H), 8.63–8.48 (m, 1H), 8.12 (s, 1H), 7.80–7.71 (m, 1H), 7.71–7.66 (m, 1H), 7.55–7.43 (m, 1H), 7.15–7.12 (m, 2H), 7.08–7.04 (m, 1H), 6.99–6.94 (m, 2H), 6.57–6.53 (m, 1H), 6.36–6.34 (m, 1H), 5.79–5.76 (m, 1H), 4.65 (d, J = 5.7 Hz, 2H), 3.86 (d, J = 5.6 Hz, 2H), 2.21 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δC: 170.90, 168.53, 145.90, 139.00, 134.38, 132.46, 130.28, 128.54, 127.10, 124.46, 123.49, 123.39, 123.10, 121.62, 121.24, 120.88, 120.50, 119.73, 117.33, 109.21, 48.89, 18.07; ESI-MS m/z: 414.5 ([M+H]+).

N-[(1H-Indazol-7-yl)methyl]-2-[2-(p-tolylamino)acetamido]benzamide (2): white solid; yield in 74.5%; m.p.: 188.0–189.0 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 13.09 (s, 1H), 11.72 (s, 1H), 9.19–9.16 (m, 1H), 8.54–8.52 (m, 1H), 8.12 (s, 1H), 7.78–7.76 (m, 1H), 7.68–7.66 (m, 1H), 7.51–7.49 (m, 1H), 7.17–7.14 (m, 2H), 7.07–7.04 (m, 1H), 7.07–7.04 (m, 2H), 6.90–6.88 (m, 2H), 6.50–6.48 (m, 2H), 6.20–6.17 (m, 1H), 4.67 (d, J = 5.5 Hz, 2H), 3.75 (d, J = 5.6 Hz, 2H), 2.12 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δC:171.03, 168.56, 146.39, 138.89, 134.38, 132.38, 129.83, 128.61, 125.93, 124.19, 123.46, 123.19, 121.61, 120.89, 120.80, 119.67, 113.07, 49.74, 20.54; ESI-MS m/z: 414.2 ([M+H]+).

N-[(1H-Indazol-7-yl)methyl]-2-[2-(m-tolylamino)acetamido]benzamide (3): white solid; yield in 74.8%; m.p.: 212.1–213.0 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 13.08 (s,1H), 11.70 (s, 1H), 9.21–9.18 (m, 1H), 8.54–8.52 (m, 1H), 8.12 (s, 1H), 7.77–7.76 (m, 1H), 7.53–7.49 (m, 1H), 7.18–7.16 (m, 2H), 7.10–7.02 (m, 1H), 6.99–6.97 (m, 1H), 6.48–6.34 (m, 3H), 6.28–6.26 (m, 1H), 4.68 (d, J = 5.8 Hz, 2H), 3.77 (d, J = 5.7 Hz, 2H), 2.16 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (151 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 170.94, 168.59, 146.36, 138.90, 132.33, 130.38, 129.82, 128.58, 125.99, 124.29, 123.18, 122.59, 121.74, 120.88, 119.68, 113.16, 49.75, 40.63, 20.52; ESI-MS m/z: 414.2 ([M+H]+).

N-[(1H-Indazol-7-yl)methyl]-2-[2-(cyclohexylamino)acetamido]benzamide (4): white solid; yield in 76.8%; m.p.: 181.7–182.2 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 13.08 (s, 1H), 11.76 (s, 1H), 9.22–9.18 (m, 1H), 8.52–8.50 (m, 1H), 8.12 (s, 1H), 7.75–7.73 (m, 1H), 7.69–7.67 (m, 1H), 7.49–7.47 (m, 1H), 7.26–7.25 (m, 1H), 7.16–7.14 (m, 1H), 7.12–7.06 (m, 1H), 4.79 (d, J = 5.8 Hz, 2H), 3.27 (d, J = 5.7 Hz 2H), 2.31 (s, 1H), 1.82–1.79 (m, 2H), 1.61–1.58 (m, 2H), 1.48–1.45 (m, 1H), 1.07–0.99 (m, 6H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δC: 168.57, 138.86, 138.42, 134.40, 132.04, 128.58, 124.17, 123.47, 123.00, 122.79, 121.82, 120.87, 120.67, 119.71, 57.17, 50.95, 32.98, 26.14, 24.86; ESI-MS m/z: 406.2 ([M+H]+).

N-[(1H-Indazol-7-yl)methyl]-2-[2-(thiomorpholin-4-yl)acetamido]benzamide (5): white solid; yield in 78.2%; m.p.: 184.2–185.0 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 13.14 (s, 1H), 11.70 (s, 1H), 9.27–9.21 (m, 1H), 8.51–8.49 (m, 1H), 8.12 (s, 1H), 7.82–7.74 (m, 1H), 7.68–7.66 (m, 1H), 7.55–7.46 (m, 1H), 7.25–7.24 (m, 1H), 7.21–7.15 (m, 1H), 7.13–7.06 (m, 1H), 4.80 (d, J = 5.8 Hz, 2H), 3.09 (d, J = 5.7 Hz, 2H), 2.72–2.63 (m, 4H), 2.62–2.54 (m, 4H); ESI-MS m/z: 425.2 ([M+H]+).

N-[(1H-Indazol-7-yl)methyl]-2-{2-[(4-chlorophenyl)amino]acetamido}benzamide (6): white solid; yield in 72.8%; m.p.: 165.1–166.50 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 13.09 (s, 1H), 11.73 (s, 1H), 9.20–9.18 (m,1H), 8.53–8.51 (m, 1H), 8.12 (s, 1H), 7.79–7.77 (m, 1H), 7.68–7.66 (m, 1H), 7.52–7.51 (m, 1H), 7.19–7.05 (m, 5H), 6.59–6.57 (m, 3H), 4.67 (d, J = 5.7 Hz, 2H), 3.81 (d, J = 5.6 Hz, 2H); 13C NMR (151 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 170.39, 168.60, 147.55, 138.90, 134.39, 132.45, 129.10, 128.62, 124.30, 123.27, 121.45, 120.89, 120.79, 119.71, 114.35, 49.14, 40.54; ESI-MS m/z: 434.1 ([M+H]+).

N-[(1H-Indazol-7-yl)methyl]-2-[2-(benzylamino)acetamido]benzamide (7): white solid; yield in 52.2%; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 13.12 (s, 1H), 11.87 (s, 1H), 9.30–9.27 (m, 1H), 8.53 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 8.13 (s, 1H), 7.80 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 7.67 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.50 (ddd, J = 8.6, 7.4, 1.6 Hz, 1H), 7.43 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 2H), 7.28 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 1H), 7.24–7.16 (m, 4H), 7.11–7.06 (m, 1H), 4.82 (d, J = 5.8 Hz, 2H), 3.70 (s, 2H), 3.25 (s, 2H); ESI-MS m/z: 414.1 ([M+H]+).

N-[(1H-Indazol-7-yl)methyl]-2-(2-morpholinoacetamido)benzamide (8): white solid; yield in 49.6%; 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 13.13 (s, 1H), 11.70 (s, 1H), 9.26 (s, 1H), 8.50 (dd, J = 8.4, 1.2 Hz, 1H), 8.12 (s, 1H), 7.78 (dd, J = 7.8, 1.6 Hz, 1H), 7.67 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 7.52–7.49 (m, 1H), 7.24 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 1H), 7.19–7.16 (m, 1H), 7.09 (dd, J = 8.1, 7.0 Hz, 1H), 4.80 (d, J = 5.8 Hz, 2H), 3.09 (s, 2H), 2.71–2.65 (m, 4H), 2.60–2.55 (m, 4H); ESI-MS m/z: 394.1 ([M+H]+).

5.1.2.4. Preparation of N-[(1H-indazol-7-yl)methyl)cinnamamide derivatives (9–18)

A solution of cinnamic acid derivatives (3 mmol) and 2-(7-azabenzotriazol-1-yl)-N,N,N′,N′-tetramethyluronium hexafluorophosphate (HATU, 3.60 mmol) in N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF, 50 mL) was stirred at ambient temperature for 1 h. Then, a solution of (1H-indazol-7-yl)methanamine (3.60 mmol) and N,N-diisopropylethylamine (DIPEA, 4.50 mmol) in N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF 10 mL) was added and the mixture was stirred at ambient temperature for 24 h. Water (100 mL) and ethyl acetate (20 mL) were added and the reaction mixture was stirred for 1 h. Then, the organic phase was washed with saturated brine (10 mL) and dried with anhydrous sodium sulfate. Subsequently, the solvent was evaporated to afford a crude residue. The crude residue was purified through chromatography on a silica gel column using CH3OH/CH2Cl2 (1/150) as an eluent to yield N-[(1H-indazol-7-yl)methyl)cinnamamide derivatives29 (9–18).

(E)-N-[(1H-Indazol-7-yl)methyl]-3-(4-bromophenyl)acrylamide (9): white solid; yield in 88.0%; m.p.: 214.5–215.4 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 13.05 (s, 1H), 8.77–8.75 (m, 1H), 8.11 (s, 1H), 7.69–7.67 (m, 1H), 7.63–7.61 (m, 2H), 7.57–7.45 (m, 3H), 7.27–7.19 (m, 1H), 7.09–7.07 (m, 1H), 6.77 (d, J = 15.8 Hz, 1H), 4.71 (d, J = 5.9 Hz, 2H); ESI-MS m/z: 356.0 ([M+H]+).

(E)-N-[(1H-Indazol-7-yl)methyl]-3-(4-chlorophenyl)acrylamide (10): white solid; yield in 87.6%; m.p.: 197.7–198.8 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) 13.05 (s, 1H), 8.77–8.75 (m, 1H), 8.12 (s, 1H), 7.69–7.67 (m, 1H), 7.63–7.61 (m, 2H), 7.56–7.44 (m, 3H), 7.25–7.23 (m, 1H), 7.13–7.06 (m, 1H), 6.75 (d, J = 15.8 Hz, 1H), 4.72 (d, J = 5.9 Hz, 2H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 165.77, 138.37, 134.45, 134.34, 134.28, 129.77, 129.46, 124.54, 123.47, 123.15, 120.86, 119.82, 40.68; ESI-MS m/z: 312.1 ([M+H]+).

(E)-N-[(1H-Indazol-7-yl)methyl]-3-[4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl]acrylamide (11): white solid; yield in 88.2%; m.p.: 213.8–214.8 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 13.07 (s, 1H), 8.83–8.81 (m, 1H), 8.12 (s, 1H), 7.85–7.74 (m, 4H), 7.70–7.68 (m, 1H), 7.59 (d, J = 15.8 Hz, 1H), 7.30–7.21 (m, 1H), 7.15–7.04 (m, 1H), 6.88 (d, J = 15.8 Hz, 1H), 4.73 (d, J = 5.7 Hz, 2H); 13C NMR (151 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 165.50, 139.46, 139.02, 138.00, 134.38, 128.68, 126.27, 126.25, 125.24, 124.63, 123.53, 121.80, 120.84, 119.83, 40.63; ESI-MS m/z: 346.1 ([M+H]+).

(E)-N-[(1H-Indazol-7-yl)methyl]-3-(4-nitrophenyl)acrylamide (12): white solid; yield in 88.1%; m.p.: 262.8–263.4 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 13.07 (s, 1H), 8.89–8.86 (m,1H), 8.35–8.19 (m, 2H), 8.12 (s, 1H), 7.92–7.80 (m, 2H), 7.73–7.55 (m, 2H), 7.31–7.20 (m, 1H), 7.14–7.06 (m, 1H), 6.94 (d, J = 15.9 Hz, 1H), 4.74 (d, J = 5.7 Hz, 2H); 13C NMR (151 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 165.27, 148.08, 141.98, 139.01, 137.34, 134.38, 129.12, 126.70, 124.64, 124.56, 123.55, 121.71, 120.85, 119.86, 40.63; ESI-MS m/z: 323.1 ([M+H]+).

(E)-N-[(1H-Indazol-7-yl)methyl]-3-(4-fluorophenyl)acrylamide (13): white solid; yield in 89.4%; m.p.: 175.5–176.6 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 13.04 (s, 1H), 8.75–8.73 (m, 1H), 8.12 (s, 1H), 7.72–7.60 (m, 3H), 7.52 (d, J = 15.8 Hz, 1H), 7.33–7.19 (m, 3H), 7.14–7.04 (m, 7.0 Hz, 1H), 6.69 (d, J = 15.8 Hz, 1H), 4.71 (d, J = 5.9 Hz, 2H); 13C NMR (151 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 165.93, 138.51, 134.36, 130.24, 130.18, 124.59, 123.49, 122.31, 122.01, 120.84, 119.79, 116.44, 116.29, 40.63; ESI-MS m/z: 296.1 ([M+H]+).

(E)-N-[(1H-Indazol-7-yl)methyl]-3-(4-methoxyphenyl)acrylamide (14): white solid; yield in 87.7%; m.p.: 168.7–169.7 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 13.03 (s, 1H), 8.67–8.63 (m, 1H), 8.11 (s, 1H), 7.68–7.66 (m, 1H), 7.57–7.51 (m, 2H), 7.47 (d, J = 15.8 Hz, 1H), 7.6–7.20 (m, 1H), 7.13–7.05 (m, 1H), 7.01–6.95 (m, 2H), 6.60 (d, J = 15.8 Hz, 1H), 4.70 (d, J = 5.8 Hz, 2H), 3.79 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (151 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 166.35, 160.91, 139.46, 139.03, 134.36, 129.64, 127.91, 124.59, 123.49, 122.15, 120.83, 119.87, 119.75, 114.90, 55.75, 40.63; ESI-MS m/z: 308.1 ([M+H]+).

(E)-N-[(1H-Indazol-7-yl)methyl]-3-(3,4-difluorophenyl)acrylamide (15): white solid; yield in 82.3%; m.p.: 210.5–211.2 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 13.05 (s, 1H), 8.74–8.70 (m, 1H), 8.12 (d, J = 1.4 Hz, 1H), 8.11 (s, 1H), 7.69–7.66 (m, 2H), 7.62–7.61 (m, 1H), 7.41–7.40 (m, 1H), 7.26–7.22 (m, 1H), 7.10 (m, 2H), 6.50 (d, J = 15.5 Hz, 1H), 4.70 (d, J = 5.7 Hz, 2H); 13C NMR (151 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 165.63, 139.01, 137.57, 134.37, 133.33, 125.22, 125.18, 124.60, 123.83, 123.52, 121.88, 120.83, 119.81, 118.56, 118.44, 116.84, 116.72, 40.63; ESI-MS m/z: 314.1 ([M+H]+).

(E)-N-[(1H-Indazol-7-yl)methyl]-3-(pyridin-4-yl)acrylamide (16): white solid; yield in 88.2%; m.p.: 189.5–190.1 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 13.05 (s, 1H), 8.76–8.72 (m, 1H), 8.12 (s, 1H), 7.76–7.65 (m, 2H), 7.55–7.43 (m, 3H), 7.09–7.08 (m, 1H), 6.73 (d, J = 15.8 Hz, 1H), 4.73 (d, J = 5.8 Hz, 2H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ: 165.51, 150.67, 149.63, 138.95, 136.39, 134.47, 134.36, 131.09, 124.54, 124.44, 124.30, 123.47, 121.81, 120.84, 119.81; ESI-MS m/z: 279.1 ([M+H]+).

(E)-N-[(1H-Indazol-7-yl)methyl]-3-(furan-2-yl)acrylamide (17): white solid; yield in 88.1%; m.p.: 175.8–176.6 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 13.04 (s, 1H), 8.79–8.75 (m, 1H), 8.11 (s, 1H), 7.79–7.78 (m, 1H), 7.68–7.67 (m, 1H), 7.35–7.31 (m, 1H), 7.23–7.21 (m, 1H), 7.13–7.05 (m, 1H), 6.81–6.80 (m, J = 3.3 Hz, 1H), 6.60–6.59 (m, J = 3.3, 1H), 4.70 (d, J = 5.8 Hz, 2H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ: 165.84, 151.36, 145.36, 138.98, 134.27, 127.09, 124.43, 123.44, 121.98, 120.86, 119.78, 119.45, 114.53, 112.89; ESI-MS m/z: 267.2 ([M+H]+).

(E)-N-[(1H-Indazol-7-yl)methyl]-3-(thiophen-2-yl)acrylamide (18): white solid; yield in 82.3%; m.p.: 186.2–186.9 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 13.04 (s, 1H), 8.74–8.70 (m, 1H), 8.11 (s, 1H), 7.69–7.66 (m, 2H), 7.62–7.61 (m, 1H), 7.41–7.40 (m, 1H), 7.26–7.24 (m, 1H), 7.16–7.05 (m, 2H), 6.50 (d, J = 15.5 Hz, 1H), 4.70 (d, J = 5.8 Hz, 2H); 13C NMR (151 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 165.71, 140.24, 138.94, 134.36, 132.77, 131.30, 128.83, 128.55, 124.47, 123.47, 121.91, 120.97, 120.86, 119.79, 40.53; ESI-MS m/z: 284.1 ([M+H]+).

5.1.2.5. Preparation of 1-[(1H-indazol-7-yl)methyl]thiourea derivatives (19–31)

A solution of isothiocyanate derivatives (3.60 mmol), (1H-indazol-7-yl)methanamine (3.60 mmol) and triethylamine (TEA, 3.60 mmol) in tetrahydrofuran (THF, 30 mL) was stirred at ambient temperature for 3 h. Then, the solvent was evaporated to afford crude residue. Subsequently, the crude product was recrystallized with methanol (20 mL) to obtain 1-[(1H-indazol-7-yl)methyl]thiourea derivatives30 (19–31).

1-[(1H-Indazol-7-yl)methyl]-3-phenylthiourea (19): white solid; yield in 85.5%; m.p.: 164.0–164.5 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 13.15 (s, 1H), 9.72 (s, 1H), 8.21 (s, 1H), 8.11 (s, 1H), 7.68–7.66 (m, 1H), 7.44–7.42 (m, 2H), 7.44–7.42 (m, 2H), 7.36–7.34 (m, 2H), 7.19–7.03 (m, 2H), 5.03 (d, J = 5.5 Hz, 2H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ: 181.34, 139.50, 138.90, 134.29, 129.18, 124.97, 124.58, 124.00, 123.45, 121.69, 121.68, 120.80, 119.69, 44.41; ESI-MS m/z: 283.1 ([M+H]+).

1-[(1H-Indazol-7-yl)methyl]-3-(p-tolyl)thiourea (20): white solid; yield in 86.7%; m.p.: 210.1–211.4 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 13.13 (s, 1H), 9.62 (s, 1H), 8.16–8.02 (m, 2H), 7.68–7.66 (m, 1H), 7.27–7.25 (m, 3H), 7.16–7.14 (m, 2H), 7.12–7.07 (m, 1H), 5.02 (d, J = 5.6 Hz, 2H), 2.28 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (151 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 181.41, 139.17, 138.88, 134.36, 131.86, 125.76, 124.61, 123.52, 121.43, 120.81, 119.76, 116.74, 44.38, 25.60; ESI-MS m/z: 297.1 ([M+H]+).

1-[(1H-Indazol-7-yl)methyl]-3-(3-chlorophenyl)thiourea (21): white solid; yield in 88.2%; m.p.: 171.5–172.5 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 13.17 (s, 1H), 9.84 (s, 1H), 8.38 (s, 1H), 8.12 (s, 1H), 7.73 (s, 1H), 7.69–7.67 (m, 1H), 7.35–7.34 (m, 2H), 7.28 (m, 1H), 7.17–7.16 (m, 1H), 7.14–7.07 (m, 1H), 5.03 (d, J = 5.2 Hz, 2H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 181.32, 149.14, 147.01, 138.89, 134.30, 131.85, 124.73, 123.43, 121.89, 120.73, 119.61, 117.19, 112.41, 109.91, 56.17, 55.84, 44.59; ESI-MS m/z: 317.1 ([M+H]+).

1-[(1H-Indazol-7-yl)methyl]-3-(4-chlorophenyl)thiourea (22): white solid; yield in 84.7%; m.p.: 193.5–194.2 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 13.16 (s, 1H), 9.78 (s, 1H), 8.29 (s, 1H), 8.11 (s, 1H), 7.69–7.67 (M, 1H), 7.51–7.49 (m, 2H), 7.43–7.34 (m, 2H), 7.28–7.26 (m, 1H), 7.15–7.05 (m, 1H), 5.03 (d, J = 5.2 Hz, 2H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 181.47, 138.86, 138.70, 134.35, 128.94, 128.66, 125.51, 124.59, 123.50, 121.45, 120.81, 119.75, 44.38; ESI-MS m/z: 317.1 ([M+H]+).

1-[(1H-Indazol-7-yl)methyl]-3-(2,3-dichlorophenyl)thiourea (23): white solid; yield in 86.4%; m.p.: 196.0–196.5 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 13.11 (s, 1H), 9.55 (s, J = 5.7 Hz, 1H), 8.48 (s, 1H), 8.11 (s, 1H), 7.69–7.67 (m, 1H), 7.53–7.52 (m, 1H), 7.38–7.36 (m, 1H), 7.29–7.27 (m, 1H), 7.17–7.03 (m, 1H), 5.01 (d, J = 5.7 Hz, 2H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 182.22, 138.86, 138.56, 134.35, 132.29, 128.25, 124.60, 123.49, 121.34, 120.81, 119.79, 44.69; ESI-MS m/z: 351.0 ([M+H]+).

1-[(1H-Indazol-7-yl)methyl]-3-(3,4-dimethoxyphenyl)thiourea (24): white solid; yield in 86.6%; m.p.: 164.0–164.5 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 13.11 (s, 1H), 9.58 (s, J = 5.7 Hz, 1H), 8.10 (s, 1H), 8.00 (s, 1H), 7.67–7.65 (m, 1H), 7.28–7.26 (m, 1H), 7.15–7.04 (m, 1H), 7.01–6.87 (m, 2H), 6.82–6.81 (m, 1H), 5.01 (d, J = 5.7 Hz, 2H), 3.74 (s, 3H), 3.69 (s, 1H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ: 181.30, 149.13, 146.99, 138.88, 134.36, 131.90, 124.76, 123.41, 121.86, 120.72, 119.60, 117.18, 112.40, 109.90, 56.16, 55.84, 44.59; ESI-MS m/z: 343.1 ([M+H]+).

1-[(1H-Indazol-7-yl)methyl]-3-(4-iodophenyl)thiourea (25): white solid; yield in 85.7%; m.p.: 195.5–196.2 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 13.16 (s, 1H), 9.77 (s, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H), 8.31 (s, 1H), 8.11 (s, 1H), 7.69–7.65 (m, 3H), 7.32–7.30 (m, 2H), 7.27–7.25 (m, 1H), 7.10–7.08 (m, 1H), 5.02 (d, J = 5.0 Hz, 2H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 165.53, 150.68, 149.65, 138.97, 136.40, 134.48, 131.11, 124.56, 124.45, 123.49, 121.83, 120.85, 119.83, 40.62; ESI-MS m/z: 408.0 ([M+H]+).

1-[(1H-Indazol-7-yl)methyl]-3-[4-(trifluoromethoxy)phenyl]thiourea (26): white solid; yield in 85.5%; m.p.: 194.5–195.0 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 13.06 (s, 1H), 8.79–8.78 (m, 1H), 8.57–8.55 (m, 1H), 8.12 (s, 1H), 8.02–8.01 (m, 1H), 7.69–7.67 (m, 1H), 7.58–7.54 (m, 1H), 7.47–7.44 (m, 1H), 7.25–7.24 (m, 1H), 7.15–7.04 (m, 1H), 6.88–6.84 (m, 1H), 4.73 (d, J = 5.7 Hz, 2H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 165.53, 150.68, 149.65, 138.97, 136.40, 134.48, 134.38, 131.11, 124.56, 124.45, 124.31, 123.49, 121.83, 120.85, 119.83, 40.62; ESI-MS m/z: 367.0 ([M+H]+).

1-[(1H-Indazol-7-yl)methyl]-3-[4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl]thiourea (27): white solid; yield in 86.6%; m.p.: 204.5–205.0 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 13.21 (s, 1H), 10.06 (s, 1H), 8.51 (s, 1H), 8.13 (s, 1H), 7.79–7.77 (m, 2H), 7.69–7.67 (m, 3H), 7.31–7.29 (m, 1H), 7.14–7.10 (m, 1H), 5.06 (d, J = 4.9 Hz, 2H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ C: 181.33, 143.76, 138.88, 134.38, 126.17, 125.76, 124.65, 123.97, 122.77, 122.65, 121.16, 120.82, 119.84, 44.36; ESI-MS m/z: 351.0 ([M+H]+).

1-[(1H-Indazol-7-yl)methyl]-3-benzylthiourea (28): white solid; yield in 87.5%; m.p.: 201.5–202.0 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 13.15 (s, 1H), 8.10–8.05 (m, 3H), 7.67–7.65 (m, 1H), 7.40–7.16 (m, 6H), 7.14–6.98 (m, 1H), 4.99 (s, 2H), 4.71 (s, 2H); 13C NMR (151 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 181.29, 139.62, 138.87, 137.70, 134.35, 125.91, 124.61, 123.50, 121.42, 120.80, 119.75, 44.37, 40.54; ESI-MS m/z: 351.0 ([M+H]+).

1-[(1H-Indazol-7-yl)methyl]-3-(4-fluorophenyl)thiourea (29): white solid; yield in 87.7%; m.p.: 200.5–201.0 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 13.16 (s, 1H), 9.70 (s, 1H), 8.20 (s, 1H), 8.11 (s, 1H), 7.68–7.66 (m, 1H), 7.45–7.41 (m, 2H), 7.28–7.25 (m, 1H), 7.20–7.16 (m, 2H), 7.13–7.06 (m, 1H), 5.03 (d, J = 5.2 Hz, 2H); 13C NMR (151 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 181.88, 138.91, 135.91, 134.34, 126.60, 124.64, 123.52, 121.61, 120.78, 119.70, 115.80, 115.65, 44.46; ESI-MS m/z: 301.1 ([M+H]+).

1-[(1H-Indazol-7-yl)methyl]-3-(4-bromophenyl)thiourea (30): white solid; yield in 86.7%; m.p.: 201.5–202.2 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 13.15 (s, 1H), 9.68 (s, 1H), 8.18 (s, 1H), 8.11 (s, 1H), 7.68–7.66 (m, 1H), 7.28–7.27 (m, 1H), 7.22–7.20 (m, 3H), 7.12–7.10 (m, 1H), 6.97–6.95 (m, 1H), 5.03 (d, J = 5.2 Hz, 2H); 13C NMR (151 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 181.36, 139.34, 138.95, 138.51, 134.34, 129.04, 125.75, 124.79, 124.61, 123.53, 121.67, 121.24, 120.76, 119.71, 44.50; ESI-MS m/z: 361.0 ([M+H]+)0.1-[(1H-indazol-7-yl)methyl]-3-(4-cyanophenyl)thiourea (31): white solid; yield in 86.9%; m.p.: 199.1-196.2 °C; 1H-NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 13.21 (s, 1H), 10.14 (s, 1H), 8.59 (s, 1H), 8.13 (s, 1H), 7.82–7.75 (m, 4H), 7.71–7.69 (m, 1H), 7.30–7.28 (m, 1H), 7.13–7.09 (m, 1H), 5.05 (d, J = 4.3 Hz, 2H); 13C NMR (151 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 181.08, 144.62, 138.91, 134.41, 133.28, 124.70, 123.58, 122.06, 120.96, 120.83, 119.92, 119.58, 105.41, 44.34; ESI-MS m/z: 308.1 ([M+H]+).

5.2. Cells, viruses and other biological materials

MDCK and HEK293T cells were obtained from ATCC. MDCK cells were cultured in Minimal Essential Medium (MEM, Gibco) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco). HEK293T cells were cultured in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM, Gibco) supplemented with 10% FBS. Both cells were cultured at 37 °C with 5% CO2. Influenza A viruses A/WSN/33 (H1N1), A/PR/8/34 (H1N1), A/HK/1/68 (H3N2), and A/California/7/09(H1N1pdm) and the influenza B virus B/Florida/04/2006 were described previously31,32. All viruses were handled in a class II biosafety cabinet. Plasmids used in the minigenome luciferase reporter assay have been described previously33. Transfection was performed with Lipofectamine2000 (Invitrogen) following manufacturer's protocol. The following antibodies were used in co-immunoprecipitation and Western blotting: anti-myc (Cell Signaling Technology, Cat. 2276), anti-PA (Genetex, Cat. GTX118991), anti-PB1 (Genetex, Cat. GTX125923).

5.3. Evaluation of cytotoxicity in MDCK and HEK293T cells

The cytotoxicity of compounds in MDCK cells was determined using the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay. Cells were seeded on a 96-well plate in MEM/10%FBS and cultured overnight. The growth medium was removed and washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) before being changed to plain MEM supplemented with tested compounds at appropriate concentrations. After 48 h, MTT in PBS was added to a final concentration of 0.5 mg/mL and a further 1-h incubation at 37 °C was allowed. The medium was then removed and DMSO was added to solubilize the formazan crystals formed. Absorbance at 540 nmol/L was recorded on a CLARIOstar microplate reader. HEK293T cells were seeded on a 96-well plate in DMEM/10%FBS together with the compounds at appropriate concentrations. Cells were incubated for 48 h before MTT was added. The steps for formazan development and absorbance reading at OD540 were the same as those for MDCK cells.

5.4. Cytopathic effect reduction assay

MDCK cells seeded on 96-well cell culture plates were infected with A/WSN/33 (H1N1) virus at a multiplicity-of-infection (MOI) of 0.01. Virus inoculum was removed after 1 h and cells were extensively washed thrice with PBS. Compounds dissolved in serum-free MEM to appropriate concentrations were added to the cells to a final volume of 100 μL. Cells were allowed for a further incubation of 2 days and MTT assay was performed as described above to quantify virus-induced cytopathic effect (CPE). To calculate the CPE reduction for compound 24, the following calculation was used: [Abs(treatment)‒Abs(DMSO)]/[Abs(No infection control)‒Abs(DMSO)]

5.5. Viral yield reduction assay

MDCK cells were seeded on 24-well plates and infected with the influenza virus at a MOI of 0.01. Cells were washed with PBS after an 1-h inoculation. Serum-free MEM (100 μL) containing 1 μg/mL TPCK-treated trypsin and compounds adjusted to appropriate concentrations was added to the cells. In the case of A/WSN/33(H1N1), TPCK-treated trypsin was omitted. Supernatants were collected 24 h post-infection, and viral titres were determined by plaque assay. The system was validated using the positive chemical BxM. Dose–response curves are presented with y-axes representing the viral titre normalized to the negative (DMSO) control in percentage and x-axes representing molar concentration. EC50 values represent the concentration where the viral titre is 50% of the negative control.

5.6. Viral titre determination by plaque assay

A 10-fold dilution series was first prepared for each virus to be titred. Pre-seeded MDCK cells were incubated with serially diluted viruses for 1 h, washed and overlaid with a 1:1 mixture of 2% agarose, 1 μg/mL TPCK-treated trypsin and serum-free MEM. In the cases of A/WSN/33(H1N1), TPCK-treated trypsin was omitted. After incubation at 37 °C for 48 h, the agarose layer was removed and cells were stained with 0.1% (w/v) Coomassie Blue, 30% methanol and 5% acetic acid. Number of plaques formed was counted to determine the viral titres.

5.7. Minigenome luciferase reporter assay

The luciferase reporter system was described previously33. Briefly, plasmids encoding the PA, PB1, PB2 and NP genes of A/WSN/33(H1N1) or A/HK/156/97(H5N1) on a pcDNA3 backbone were co-transfected onto HEK293T cells on a 30 mmol/L dish with the luciferase reporter plasmid and a control EGFP plasmid. Transfection was performed using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) at a ratio of 1 μg DNA:1.5 μL transfection agent. Cells were re-seeded onto a 96-well plate at 24 h post-transfection. Subsequently, they were treated with compounds at appropriate concentrations (in triplicate for each concentration) and incubated for 48 h before being harvested in lysis buffer (50 mmol/L Tris pH 7.8, 150 mmol/L NaCl, 10% glycerol, 1% Triton X-100, 2 mmol/L DTT, 1 mmol/L EDTA). GFP signal was first measured on a ClarioStar spectrophotometer. A luciferase substrate (Promega) was subsequently added to each well and the chemiluminescence signal was measured. RNP activities were reflected by the chemiluminescence signal normalized by the GFP signal. The experiment was performed thrice.

5.8. Protein expression and purification

Expression of PA C-terminal domain as a hexahistidine-tagged fusion protein in E. coli BL21(DE3)pLysS strain was described previously with modifications33. Expression was induced by isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside to a final concentration of 0.4 μmol/L at 16 °C for 16 h with shaking at 220 rpm. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 4 °C. Harvested cells expressing the PA C-terminal domain were resuspended in 20 mmol/L Tris pH 7.8, 500 mmol/L NaCl, 5% glycerol, 1 mmol/L phenylmethylsulfonylfluoride, 2 mmol/L TCEP and 1 mmol/L benzadamine. Cells were lysed by sonication and the lysate was cleared by centrifugation at 20,000 g for 1 h at 4 °C. The protein was then purified on a nickel-chelating IMAC column and eluted in 20 mmol/L Tris–HCl pH 7.8, 500 mmol/L NaCl, 5% glycerol, 500 mmol/L imidazole after extensive washing. The protein was further subjected to Superdex 200 10/300 GL gel filtration column and buffer exchanged to 20 mmol/L Tris pH 7.8, 500 mmol/L NaCl, 5% glycerol for storage. The expression and purification of K643A and Q408A mutants followed the same procedure.

5.9. Microscale thermophoresis

Prior to MST experiment, purified PA-C protein was buffer exchanged to 20 mmol/L Tris pH 7.8, 125 mmol/L NaCl and 1.25% glycerol. MST experiments were performed on a Monolith NT.LabelFree machine (Nanotemper, Munich, Germany). A 20 μL MST sample was made up by mixing 10 μL of protein titrated against a serial 2-fold dilution of compound 24. MST samples were loaded into Nanotemper's Monolith LabelFree capillaries (standard-treated). Measurements were made at 23 °C with 1% LED and medium MST power. The experiment was repeated in 15% LED/medium MST power with similar results. Nanotemper's MO.Affinity V2.3 software was used to analyze MST data using thermophoresis signal at 5 s MST-on-time. Fnorm against concentration were fitted using the built-in Kd model using data points from at least three independent measurements and with target concentration fixed as appropriate. Outlier points due to protein aggregation, compound precipitation or capillary contamination were removed. Error bars represent the mean ± standard deviation of each data point. The reported Kd was the mean value taken from three MST experiments.

5.10. Co-immunoprecipitation

H1 or H5 PA was expressed with a myc-tag on pCMV-myc vector. PB1 was expressed on a pcDNA3 vector. PA and PB1 were separately transfected into HEK293T cells using Lipofectamine 2000. Cells were harvested 48 h post-transfection in 50 mmol/L Tris pH 7, 500 mmol/L NaCl, 2 mmol/L EDTA, 0.5% Triton X-100. Cell lysates with expressed PB1 were mixed with PA either in the presence of compound 24 or an equivalent volume of DMSO as control. After incubation at 4 °C for at least 1 h for complex formation, the PA-PB1 complex was co-immunoprecipitated by anti-PA (H1) or anti-myc (H5). The reaction mixture was then incubated with protein A agarose (Sigma) for an additional 1 h and washed with the lysis buffer. The bound complex was eluted by addition of SDS loading dye and boiled at 100 °C for 10 min. The eluted complex was separated on 12% SDS-PAGE and detected by Western blotting.

5.11. Molecular docking

The PA-C structure from Protein Databank 3CM812 was used for molecular docking in the Gild-XP (Extra Precision Glide) package. The structure was first prepared in Schrödinger's protein preparation wizard to define an active site of PA-C based on residues N412, Q408, E623, W706, W618, I621, K643, R673, and Q67012. Compound 24 was prepared for molecular docking by Glide-XP (Extra Precision Glide) to generate three-dimensional conformers. Docking results were visualized in Pymol (Schrödinger LLC) and were manually checked for free energy scoring and correct conformation. Polar contacts were identified in Pymol.

5.12. Molecular dynamics simulation

The complex 24-PA-C was subjected to a 100 ns molecular dynamics (MD) simulation performed on the Desmond v3.8 module, Schrödinger suite (version 9.6, Schrödinger Inc., NY, USA). SPC water and an appropriate amount of counter ions for buffer area formation were added. OPLS_2005 force field was implemented for energy minimization, and a maximum number of iterations was set at 5000. MD simulations were performed for 300 K and 1.01325 bar. The Simulation Quality Analysis tools and the Simulation Event Analysis tool were used to analyze the quality of MD simulations. The Simulation Interaction Diagram tool was used for protein-ligand interaction identification.

5.13. Thermal shift assay

The PA-C protein or its variants were prepared in 20 mmol/L Tris, pH 7.8, 150 mmol/L NaCl, 1.25% glycerol. The protein concentration used was in the range of 60–80 μmol/L. Compound 24 or equivalent amount of DMSO as control was added to the protein to allow ligand binding. To saturate the protein, at least 20-fold molar excess of compound was used. 1 μL of 500-fold diluted Sypro Orange gel stain dye (ThermoFisher, Cat. S6650) was then added to 9 μL of the protein-ligand complex. Sample mixtures were subjected to a Bio-rad CFX96 Touch Real-Time PCR Detection System and heated from 16 to 94 °C in increments of 0.3 °C for 3 s followed by plate reading. Excitation and emission wavelengths were set as 483 nmol/L/568 nm. Melt peaks (expressed as –d(RFU)/dT versus temperature) were obtained with Bio-rad's CFX Manager V3.0. Each experiment was performed twice with at least triplicate readings in each run. The mean melting temperature with standard deviation was reported. The following three control experiments were also performed: PA-C protein without dye, PA-C protein added with compound 24 without dye and compound 24 with dye.

5.14. In vivo efficacy in mice model

Groups of nine BALB/c mice were divided randomly into the untreated (vehicle), oseltamivir acid (positive control), 24 (treatment) and no-infection control (normal) groups. Mice except those in the normal group were intranasally infected with 2 mouse lethal dose 50 of mouse-adapted A/PR/8/34 (H1N1) virus in a volume of 20 μL virus in PBS. The treatment group was orally treated with 800 mg/kg/day compound 24 in 0.5% CMC solution, while the positive control group was treated with a solution of oseltamivir at 65 mg/kg/day. The normal and vehicle groups were treated with 0.5% CMC solution. The compound was administered once daily for 6 consecutive days, and body weight was recorded for a 16 consecutive days. Mice with a weight loss of >25% were sacrificed according to university guidelines.

Four mice from each group were randomly selected and sacrificed on the fourth day post-infection. Lung tissues were weighed. The lung index was calculated as follows: Lung index (%) = [lung weight / body weight] × 100. Right lungs were homogenized in MEM containing 0.1% penicillin-streptomycin. The homogenates were cleared by centrifugation at 12,000 rpm for 5 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was aliquoted and stored at −80 °C until it was used for titer determination. Lung homogenates were 10-fold serial diluted and used for plaque assay following the procedures described above.

5.15. Statistics

Dose–response curves in cytopathic effect reduction assay, viral yield reduction assay and minigenome reporter assay were fitted in GraphPad Prism 9 with the built-in variable slope, four parameters dose–response fit algorithm. Error bars on dose–response curves represent the standard deviation of individual data points. EC50 values were presented with 95% confidence intervals. P values were obtained by two-tailed Student's t-test or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Dunnett's post hoc test, as described in the text or figures.

Author contributions

Yun-Sang Tang: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Chao Zhang: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Software, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation. Jing Xu: Software, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Haibo Zhang: Methodology, Investigation. Zhe Jin: Methodology, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Mengjie Xiao: Investigation. Nuermila Yiliyaer: Investigation. Er-Fang Huang: Supervision, Methodology, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Xin Zhao: Investigation. Chun Hu: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Conceptualization. Pang-Chui Shaw: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Resources, Methodology, Conceptualization.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a Health and Medical Research Fund (HMRF), Hong Kong SAR (No.18170352, China) to Pang-Chui Shaw.

Footnotes

Peer review under the responsibility of Chinese Pharmaceutical Association and Institute of Materia Medica, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences.

Supporting information to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsb.2025.04.014.

Contributor Information

Er-Fang Huang, Email: erfanghuang@syphu.edu.cn.

Chun Hu, Email: chunhu@syphu.edu.cn.

Pang-Chui Shaw, Email: pcshaw@cuhk.edu.hk.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supporting Information to this article.

References

- 1.Matsuzaki Y., Katsushima N., Nagai Y., Shoji M., Itagaki T., Sakamoto M., et al. Clinical features of influenza C virus infection in children. J Infect Dis. 2006;193:1229–1235. doi: 10.1086/502973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Daniels R.S., Tse H., Ermetal B., Xiang Z., Jackson D.J., Guntoro J., et al. Molecular characterization of influenza C viruses from outbreaks in Hong Kong SAR, China. J Virol. 2020;94 doi: 10.1128/JVI.01051-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Influenza (seasonal) https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/influenza-(seasonal Available from:

- 4.Lo C.Y., Tang Y.S., Shaw P.C. In: Virus protein and nucleoprotein complexes. Harris J., Bhella D., editors. vol. 88. Springer; Singapore: 2018. Structure and function of influenza virus ribonucleoprotein; pp. 95–128. (Subcellular biochemistry). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jalily P.H., Duncan M.C., Fedida D., Wang J., Tietjen I. Put a cork in it: plugging the M2 viral ion channel to sink influenza. Antivir Res. 2020;178 doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2020.104780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hickerson B.T., Huang B.K., Petrovskaya S.N., Ilyushina N.A. Genomic analysis of influenza A and B viruses carrying baloxavir resistance-associated substitutions serially passaged in human epithelial cells. Viruses. 2023;15:2446. doi: 10.3390/v15122446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Samson M., Pizzorno A., Abed Y., Boivin G. Influenza virus resistance to neuraminidase inhibitors. Antivir Res. 2013;98:174–185. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2013.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aoki F.Y., Boivin G., Roberts N. Influenza virus susceptibility and resistance to oseltamivir. Antivir Ther. 2007:603–616. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Renaud C., Kuypers J., Englund J.A. Emerging oseltamivir resistance in seasonal and pandemic influenza A/H1N1. J Clin Virol. 2011;52:70–78. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2011.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hanpaibool C., Leelawiwat M., Takahashi K., Rungrotmongkol T. Source of oseltamivir resistance due to single E119D and double E119D/H274Y mutations in pdm09H1N1 influenza neuraminidase. J Comput Aided Mol Des. 2020;34:27–37. doi: 10.1007/s10822-019-00251-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]