Abstract

Metastasis is the leading cause of death from cutaneous melanoma. Identifying metastasis-related targets and developing corresponding therapeutic strategies are major areas of focus. While functional genomics strategies provide powerful tools for target discovery, investigations at the protein level can directly decode the bioactive epitopes on functional proteins. Aptamers present a promising avenue as they can explore membrane proteomes and have the potential to interfere with cell function. Herein, we developed a target and epitope discovery platform, termed functional aptamer evolution-enabled target identification (FAETI), by integrating affinity aptamer acquisition with phenotype screening and target protein identification. Utilizing the aptamer XH3C, which was screened for its migration-inhibitory function, we identified the Chondroitin Sulfate Proteoglycan 4 (CSPG4), as a potential target involved in melanoma migration. Further evidence demonstrated that XH3C induces cytoskeletal rearrangement by blocking the interaction between the bioactive epitope of CSPG4 and integrin α4. Taken together, our study demonstrates the robustness of aptamer-based molecular tools for target and epitope discovery. Additionally, XH3C is an affinity and functional molecule that selectively binds to a unique epitope on CSPG4, enabling the development of innovative therapeutic strategies.

Key words: FAETI, Aptamer, Melanoma migration, Phenotype screening, Target and epitope discovery, CSPG4, Chondroitin sulfate chain, Cytoskeletal rearrangement

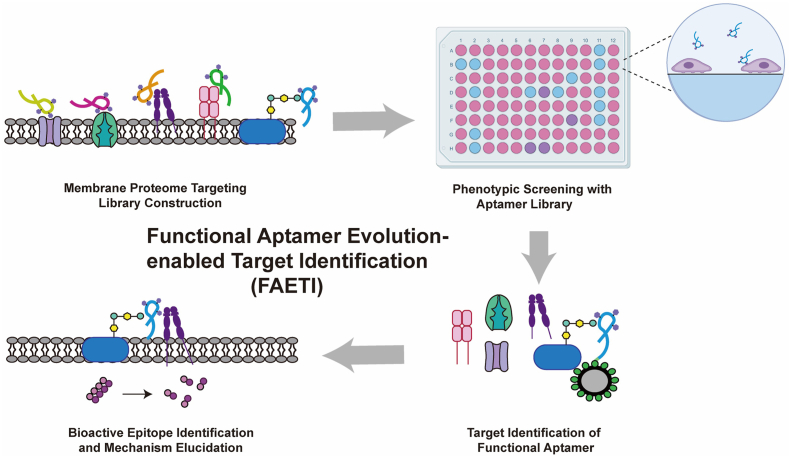

Graphical abstract

The FAETI platform was developed to identify targets and epitopes. Using identified aptamer, a melanoma migration target was discovered, demonstrating its potential for therapeutic strategy development.

1. Introduction

In recent decades, significant strides have been made in the treatment of malignant tumors. Particularly in melanoma, the discovery and effective blockade of drug targets such as the immune checkpoints PD-1/PD-L1 have greatly inspired researchers to pursue more effective targets. Notably, melanoma exhibits a rapid transition to the vertical growth phase, leading to metastatic malignant melanoma and decreasing the median 5-year survival rate to approximately 30%1,2. Therefore, further exploration of targets related to melanoma metastasis and the development of corresponding therapeutic strategies remain imperative.

Two primary strategies have emerged for identifying therapeutic targets in disease. One approach involves RNA sequencing of both healthy and diseased tissues, with a particular emphasis on single-cell RNA sequencing, to pinpoint differentially expressed genes3, 4, 5. The other relies on phenotypic screening, hit validation and target deconvolution, often necessitating the use of high-throughput molecules for perturbation, such as traditional small-molecule libraries of natural products, combinatorial chemistry and chemogenomic6,7.

To address the limitations of small molecules library, particularly its inability to target all the potential target candidates, functional genomics has emerged as a larger-scale perturbation tool. This approach integrates genetic technologies like RNA interference (RNAi) and CRISPR with phenotypic screening to identify multiple functional genes8, 9, 10. While RNA-seq and functional genomics enhance throughput, they primarily facilitate target discovery at the gene level, which may not always correlate perfectly with protein-level outcomes. These techniques cannot probe targets at the protein level, including dynamic changes in protein content, conformational alterations, and disease-related post-translational modifications, nor can they directly identify bioactive epitopes. Thus, complementary tools are still urgently needed to investigate targets at the protein level.

Bioaffinity-based proteomic assays utilizing affinity binders for membrane protein exploration offer a robust tool for mapping membrane proteomes. Techniques such as yeast display or phage display can generate antibody libraries in vitro, enabling the targeting of cell surface proteins and the identification of antigens of interest11, 12, 13, 14. Aptamers, drawn from a significantly larger pool of potential binders, also hold promise for membrane protein exploration and biomarker discovery15, 16, 17. This strategy, also referred to as aptamer-facilitated biomarker discovery, can yield aptamers capable of distinguishing between tumor and normal cells without prior knowledge of the surface proteins. These aptamers have the potential to identify binding proteins as potential biomarkers. Numerous studies have employed this approach to identify biomarkers18, 19, 20, 21, some of which have even investigated protein functions using selected aptamers22.

Nevertheless, most of these studies have typically been centered around searching for affinity molecules rather than functional molecules. While the former can uncover biomarkers, the latter have the potential to identify disease therapeutic targets, or even epitopes. Consequently, functional molecules derived from phenotypic screening of large-scale affinity molecules are anticipated to serve as tools for investigating targets at the phenotypic level. Aptamers offer distinct advantages over in vitro antibody libraries for functional assays. They can be easily chemically synthesized, allowing for the creation of large-scale libraries, and their in vitro evolution process is simpler and more efficient.

In the present study, we evolved an affinity aptamers library targeting membrane proteomes of melanoma A375 cells for phenotypic screening of melanoma migration inhibition (Fig. 1). This led to the discovery of aptamer XH3C, which possesses melanoma migration-inhibitory function. With the aid of functional aptamer XH3C, we identified Chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan 4 (CSPG4) as melanoma migration-related target. Additionally, we demonstrated that XH3C induces cytoskeletal rearrangement by blocking the interaction between the bioactive epitope of CSPG4—likely the chondroitin sulfate chain—and integrin α4, thereby revealing the mechanism behind XH3C's migration-inhibitory function. This platform, termed functional aptamer evolution-enabled target identification (FAETI), underscore the potential of functional aptamers for discovering therapeutic targets and epitopes. Moreover, the obtained aptamer XH3C targets a unique epitope on CSPG4, distinct from the binding sites of previously reported antibodies23. Consequently, novel therapeutic strategies based on XH3C can be developed for treating melanoma metastasis.

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of the platform of functional aptamer evolution-enabled target identification (FAETI). After constructing a library targeting membrane proteome, phenotypic screening was performed based on aptamer library to discover functional aptamer. Utilizing the functional aptamer, functional target and bioactive epitope were identified.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. General information

2.1.1. Chemicals and reagents

DMT-dC (Bz)-CE phosphoramidite, DMT-dG (iBu)-CE phosphoramidite, DMT-dA (Bz)-CE phosphoramidite and DMT-5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine-3′-CE phosphoramidite, as well as 5′-biotin CE phosphoramidite were acquired from Beijing Highgene-tech Automation Ltd. Tris (3-hydroxypropyltriazolylmethyl) amine (THPTA) and 3-(2-bromoethyl) indole were procured from Innochem Technology Co., Ltd. The 2′-deoxyribonucleotide triphosphates (dNTPs), comprising dATP, dTTP, dGTP, dCTP, and 5-ethynyl-dUTP, were obtained from Wuhu Huaren Science and Technology Co., Ltd. Hot Start Taq DNA polymerase was sourced from GenStar Biosolutions Co., Ltd. λ-Exonuclease was sourced from Suzhou Novoprotein Scientific Co., Ltd. Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and 0.25% trypsin-EDTA were purchased from ThermoFisher Scientific Inc. (Waltham, MA, USA). BSA and yeast tRNA were purchased from Sigma–Aldrich Co., Ltd. (St. Louis, USA). PE–Streptavidin conjugates were obtained from Sangon Biotech Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Streptavidin-coated magnetic beads were obtained from Suzhou Beaverbio Co., Ltd. (Suzhou, China). PMSF, RIPA, and IP lysate solution were obtained from Beyotime Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Anti-CSPG4 rabbit antibody was purchased from Abcam Co., Ltd. (Shanghai local agent, USA). Anti-β-actin rabbit antibody was purchased from Bioss Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). CSPG4 eukaryotic protein was purchased from ACROBiosystems Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). Chondroitinase ABC was purchased from Macklin Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Anti-ITGA4 mouse antibody was purchased from Cloud-clone Co., Ltd. (Wuhan, China). YF488-Phalloidin, YF594 goat anti-rabbit antibody, and YF647 goat anti-mouse antibody were purchased from UElandy Co., Ltd. (Suzhou, China). Hoechst33342 was purchased from HARVEYBIO Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). Protein G magnetic beads were obtained from MedChemExpress Co., Ltd. (NJ, USA). FITC-SG1 peptide was synthesized by Shanghai Apeptide Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Chondroitin sulfates A were purchased from Bide Pharmatech Ltd. (Shanghai, China).

2.1.2. Cell lines and cell culture

The human melanoma cell line A375 and the Human embryonic kidney cell line HEK293T, obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC), were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; Gibco, USA). All cell culture media were supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (heat-inactivated; Gibco, USA) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (ThermoFisher Scientific, USA). All cells were cultured in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2 at 37 °C.

2.2. Construction of aptamer libraries mapping A375 membrane proteomes

2.2.1. DNA oligonucleotides

Initial library:

5′- CACGACGCAAGGGACCACAGG-N25-CAGCACGACACCGCAGAGGCA -3′ (N means dA:dG:dC:EdU =1:1:1:1)

Forward primer: 5′-CACGACGCAAGGGACCACAGG-3′

Reverse primer: 5′-phosphate-TGCCTCTGCGGTGTCGTGCTG-3′

2.2.2. Synthesis of 3-(2-azidoethyl)-1H-indole

First, charge a 250 mL round-bottomed flask with sodium azide (1.20 g, 18.5 mmol) and DMSO (25 mL), and allow the mixture to stir at room temperature for 15 min. Then, treat the mixture with 3-(2-bromoethyl) indole (14.6 mmol) and stir at room temperature for 12 h. Finally, dilute the reaction with 75 mL of water and extract the mixture with EtOAc (2×). The combined organic layers were washed with saturated NaCl solution (2×). The water was then removed with magnesium sulfate anhydrous. Finally concentrat the organics under reduced pressure. Identification of 3-(2-azidoethyl)-1H-indole compound was performed by nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR). The results are consistent with previously reported data24.

2.2.3. Synthesis and purification of oligonucleotide

The initial library and all aptamers used in this work were synthesized in the laboratory using a standard phosphoramidite protocol on a DNA synthesizer (96 Channels DNA/RNA Synthesizer, Beijing Highgene-tech Automation Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) at a 50 nmol scale. For library synthesis, DMT-dC (Bz)-CE phosphoramidite, DMT-dG (iBu)-CE phosphoramidite, DMT-dA (Bz)-CE phosphoramidite and DMT-5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine-3′-CE phosphoramidite were mixed in a vial, placed at the N vial position, and the random sequences were set on the synthesis programs to 25 N.

The 3-(2-azidoethyl)-1H-indole was then introduced to the alkyne-modified oligonucleotide sequences through click reaction directly on the CPG solid-phase synthesis column. 50 μL of MeOH, 10 μL 10 × PBS, 10 μL of 500 mmol/L 3-(2-azidoethyl)-1H-indole in DMSO, 10 μL of ddH2O and 20 μL of CuAAC catalyst solution (4 mmol/L THPTA, 1 mmol/L CuSO4 and 25 mmol/L sodium ascorbate in ddH2O) were mixed and incubated with 50 nmol DNA CPG column for 2.5 h at 37 °C, 800 rpm, three times.

The solid-phase synthesis columns were washed with 200 μL of 50% water/MeOH. Deprotection was carried out using an ammonia resolver at 95 °C for 3 h, followed by washing the CPG synthetic columns with 100% acetonitrile to remove short chains and desalinate. The full-length DNA strands were subsequently eluted with DEPC water, and the resulting DNA strand was freeze-dried.

2.2.4. Nucleobase analysis by HPLC after enzymatic digestion

For the enzymatic analysis of nucleosides, 3 μL of the provided 10 × S1 nuclease reaction buffer was added to 200 pmol of DNA in 27 μL of water. After adding 0.5 μL of S1 nuclease (100 U/μL), the samples were incubated in a water bath at 37 °C for 2 h. Following this, 3.5 μL of alkaline phosphatase buffer and 0.5 μL of alkaline phosphatase (CIAP) (1 U/μL), snake venom phosphodiesterase I (5 U/μL), and Benzonase® nuclease (250 U/μL) were introduced. The samples were left to incubate overnight in a 37 °C water bath. After digestion, the samples were heated to 95 °C for 5 min and then centrifuged for 10 min at 12,000×g. The supernatant was collected, filtered, and subsequently subjected to HPLC analysis. Nucleoside samples were analyzed on an UltiMate 3000 HPLC system with a SymmetryShieldTM RP 18 column (4.6 mm × 150 mm, 5 μm). The following HPLC conditions were used: 0.3 μL/min flow; Buffer A: 10 mmol/L NH4OAc (pH 4.5); Buffer B: Acetonitrile; Gradient: 10 min 100% A followed by a 20 min gradient to 30% B. Peak positions of each nucleoside are consistent with previously reported data25.

2.2.5. Construction of cell membrane-targeting library

The modified ssDNA pool dissolved in 1000 μL of binding buffer (4.5 g of glucose, 100 mg tRNA, 1 g BSA, and 5 mL of 1 mol/L MgCl2 in 1 L of DPBS) was denatured by heating at 95 °C for 5 min and then cooled on ice for 10 min. The ssDNA pool was then incubated with A375 cells in a culture dish on ice for 1 h. After washing three times, cells were scraped, and the bound ssDNA was eluted by heating at 95 °C for 5 min in 500 μL of DEPC water. The ssDNA was then recovered by centrifugation and amplified by PCR with a forward primer and a phosphate-labeled reverse primer. This step needs cycle number optimization (Supporting Information Tables S1–S3). The sense ssDNA was obtained by λ-Exonuclease digestion of the antisense ssDNA strand and modified by click reaction. For click reaction in solution, 70 μL of DNA solution containing 500 pmol DNA, 10 μL 10 × PBS, 10 μL of 10 mmol/L 3-(2-azidoethyl)-1H-indole in DMSO and 10 μL of CuAAC catalyst solution (4 mmol/L THPTA, 1 mmol/L CuSO4 and 25 mmol/L sodium ascorbate in ddH2O) were mixed and incubated for 60 min at 37 °C, 800 rpm. Then, the ssDNA was purified using Oligo Clean & Concentrator Kits (Zymo Research, USA) for the next round of selection. In the subsequent selection rounds, incubation times were shortened, and washing strengths were gradually enhanced by extending washing times and increasing the volumes of the washing buffer (4.5 g of glucose and 5 mL of 1 mol/L MgCl2 in 1 L of DPBS). Negative selection was performed at rounds 4–7, where ssDNA was incubated with HEK293T for 1 h before incubation with A375. After 7 rounds of selection, the obtained ssDNA pools were prepared for high-throughput sequencing.

2.2.6. DNA sequencing and data analysis

After 7 rounds of selection, 4th,5th,6th,7th libraries were amplified using primers with barcode sequences (Supporting Information Table S4) for next generation sequencing using the Illumina Novaseq platform.

Sequencing data analysis was performed with Aptasuite software and Aptacluster software for clustering and sorting. The software tallied the number of replicates for each sequence and computed the distance between all sequences, which was then stored using the locality sensitive hashing. Subsequently, the sequences were clustered into families based on distance threshold of 5, and these families were further organized by sorting them according to the abundance of their members.

To increase the likelihood of discovering functional aptamers, it is essential to ensure robust binding capabilities and high diversity within the aptamer libraries for phenotypic screening. Therefore, 3 strict conditions were used to filter the DNA sequences:

-

1.

From different cluster.

-

2.

Top sequences in 7th library.

-

3.

In each round from the 4th to the 7th, the counts per million (CPM) of sequences must exceed 1.5 times the CPM of sequences in the previous round (Supporting Information Table S6).

2.2.7. Flow cytometric analysis

To analyze the binding ability of DNAs, after being collected by a non-enzyme cell detachment solution (Leagene Biotech, China), 105–106 A375 cells and HEK293T cells were incubated with biotin-labeled ssDNA (250 nmol/L final concentration) in binding buffer at 4 °C for 20 min. The cell suspension was centrifuged and washed twice with washing buffer. Then cells were incubated with 1 μL PE–Streptavidin conjugates in binding buffer at 4 °C for 10 min in the dark. The cell suspension was centrifuged and washed twice with washing buffer. Then, the resuspended samples were evaluated using flow cytometry (Cytoflex, Beckman). The initial library was always used as the negative control. The fluorescence intensity was analyzed using FlowJo (v10.8) software.

2.3. High-throughput phenotypic screening for migration-inhibitory functional aptamers

2.3.1. Wound healing assay

A375 cells were seeded in 96-well plates for attachment and cultured overnight in blank DMEM medium without FBS. The confluent cell monolayer was then scratched when cell confluency reached 80%–90% and washed two times to remove floating cells and cell debris. In the phenotypic screening assay, 96 aptamers were added, with each aptamer set up in 3 replicates, and the final concentrations were approximately 1 μmol/L. In candidate validation, different concentrations of aptamers were incubated with A375 cells. Blank areas were monitored and calculated at 0, 12, 24, and 36 h using a high-content imaging instrument (Operetta, PE).

2.3.2. Data analysis

Migration rates, migration inhibition rates, normalized migration inhibition rates and normalized blank area were calculated according to Eqs. (1), (2), (3), (4):

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

where A0 represents the blank area at 0 h and Ax represents blank area at a certain time point.

2.3.3. Apparent dissociation constant measurement

A375 cells were incubated with different concentrations (1, 10, 25, 50, 75, 100, 250, 500 nmol/L) of biotin-labeled XH3C and the initial library in 200 μL of binding buffer at 4 °C for 20 min. Then cells were incubated with 1 μL PE–Streptavidin conjugates for 10 min. The apparent dissociation constant (Kd) value was determined by fitting the dependence of specific fluorescence intensities on corresponding concentrations with Eq. (5):

| (5) |

Using GraphPad Prism 8 software.

2.4. Identification of CSPG4 as the target of the functional aptamer XH3C

2.4.1. Determination of target type of XH3C

A375 cells were dissociated with 0.25% trypsin-EDTA or a non-enzyme cell detachment solution, respectively, and then incubated with biotin-labeled XH3C and PE–Streptavidin conjugates for flow cytometric analysis.

2.4.2. Target identification of XH3C

A375 cells (2 × 108 cells) were detached using a non-enzymatic cell detachment solution, washed twice, and then mixed with 2 mL of pre-cooled hypotonic buffer (50 mmol/L Tris-HCl, pH 7.35–7.45, supplemented with 10 mmol/L PMSF and 1 × protease inhibitor cocktail before use) on ice for 30 min. Cytosolic and nuclear proteins were removed by centrifugation, and the cell debris containing the membrane proteins was further treated with 500 μL of lysis buffer (2% Triton X-100 and 1% Tween-20 in hypotonic buffer) for 30 min. Subsequently, the mixture was centrifuged at 4000×g for 10 min, and the supernatant containing the membrane proteins was collected. The resulting supernatant was blocked with 0.1 mg/mL BSA and 1 mg/mL tRNA. Then, the membrane protein solution was incubated with 250 nmol/L of biotin-XH3C and biotin-library for 20 min, respectively. Streptavidin-coated magnetic beads were then added to pull down the DNA–protein complex for 1 h. After washing three times, the magnetic beads were mixed with SDS loading buffer and denatured at 95 °C for 5 min or at room temperature for 30 min. The proteins were separated using a 10% SDS-PAGE gel. Subsequently, the gel was visualized using silver staining. The aptamer-purified protein bands were excised for digestion and analyzed by LC–MS (Orbitrap Velos Pro, ThermoFisher).

2.4.3. Aptamer pull-down assay

The protein samples were prepared following the described protocol in Target identification of XH3C. Subsequently, proteins were analyzed by Western blot using the anti-CSPG4 antibody.

2.4.4. RNA interference experiments

The siRNA of CSPG426 (sense: GCUAUUUAACAUGGUGCUG (dT) (dT), antisense: CAGCACCAUGUUAAAUAGC (dT) (dT)) was synthesized by Beijing Tsingke Biotech Co., Ltd. A375 cells were transfected with siRNA using LipoRNAi transfection reagent (Beyotime Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) for 72 h. Then, the cells were harvested and analyzed by flow cytometry, and the protein extracts were detected by Western blot. The mean fluorescence intensity was calculated using FlowJo (v10.8) software and the quantitative analysis of Western blot was performed by ImageJ software. The results were statistically analyzed using GraphPad Prism 8 software.

2.4.5. Surface plasmon resonance (SPR)

A single-cycle kinetics model was utilized in the SPR Biacore 8K (Cytiva) to measure the binding affinity between XH3C and CSPG4. The carboxylated chip was initially activated with NHS and EDC. Subsequently, CSPG4 eukaryotic protein was diluted to 50 μg/mL with acetate buffer (pH 4.5) and coupled to the chip. The chip was then blocked with ethanolamine. XH3C was diluted to concentrations of 12.5, 25, 50, 100, and 200 nmol/L in a gradient with PBS-P buffer containing 5 mmol/L MgCl2. The samples were injected sequentially from low to high concentrations and the data analysis was performed finally.

2.4.6. Structure prediction

XH3C and CSPG4 complex structure prediction contains 3 parts. Structure of CSPG4 was predicted by AlphaFold3 server. Structure of XH3C was obtained by molecular dynamics simulation. The complex structure was predicted by HDOCK server27.

For the molecular dynamics simulation of XH3C, the 3dRNA/DNA web server28,29 was used to build the 3D structure of XH3C. The simulation was performed with the AMBER 16 molecular simulation package. To obtain molecular mechanical parameters for Indole-EdU, ab initio quantum chemical methods were employed using the Gaussian 16 program. The geometry was fully optimized, and then the electrostatic potentials around them were determined at the B3LYP/6-31G∗ level of theory. The RESP strategy was used to obtain the partial atomic charges. The starting structure of XH3C was solvated in TIP3P water using an octahedral box, which extended 8 Å away from any solute atom. To neutralize the negative charges of simulated molecules, Na+ counter-ions were placed next to each negative group. Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation was carried out using the PMEMD module of AMBER 16. The calculations began with 500 steps of steepest descent followed by 500 steps of conjugate gradient minimization with a large constraint of 500 kcal/mol Å-2 on the atoms of the XH3C. Then 1000 steps of steepest descent followed by 4000 steps of conjugate gradient minimization with no restraint on the complex atoms were performed. Subsequently, after 200 ps of MD, during which the temperature was slowly raised from 0 to 300 K with a weak (5 kcal/mol Å-2) restraint on the XH3C, the final unrestrained production simulations of 100.0 ns were carried out at constant pressure (1 atm) and temperature (300 K). Throughout the entire simulation, SHAKE was applied to all hydrogen atoms. Periodic boundary conditions with minimum image conventions were applied to calculate the non-bonded interactions. A cutoff of 10 Å was used for the Lennard–Jones interactions. The final conformations of the complexes used for discussion were produced from the 1000 steps of minimized averaged structure of the last 20.0 ns of MD.

The structure predictions of CSPG4 and XH3C/CSPG4 complex were performed in the following two web servers:

http://hdock.phys.hust.edu.cn/

In the HDOCK prediction results, the model with highly ranked docking score, highly ranked confidence score, small ligand RMSD, and fitting well with experimental results was considered.

2.4.7. IndU substitution and truncation analysis

Biotin-labeled IndU substitution and truncation sequences were synthesized according to the sequences in the Supporting Information Table S10. A375 cells were dissociated with non-enzyme cell detachment solution. Then A375 cells were incubated with biotin-labeled DNA and PE–Streptavidin conjugates for flow cytometric analysis, respectively.

2.5. XH3C-induced cytoskeletal rearrangement: blocking the interaction of the bioactive epitope chondroitin sulfate chain on CSPG4 and ITGA4

2.5.1. Differential gene expression analysis

Differential gene expression analysis was performed in the following two websites:

2.5.2. Determination of the effect of chondroitin sulfates on XH3C binding

To verify the effect of chondroitin sulfates on XH3C binding, A375 cells were treated with chondroitinase ABC for 24 h. Then, the cells were harvested, incubated with biotin-labeled XH3C and PE–Streptavidin conjugates for flow cytometric analysis. The protein extracts were detected by Western blot to quantify the CSPG4 glycoproteins after ChABC treatment.

To investigate whether XH3C binds specifically to chondroitin sulfates on CSPG4, A375 cells were incubated with 100 nmol/L biotin-labeled XH3C and PE–Streptavidin conjugates, washed with 20 μmol/L and 2 mmol/L chondroitin sulfate A solutions, and analyzed by flow cytometry.

2.5.3. Confocal microscopy imaging

The A375 cells were seeded into 35 mm glass-bottom cell dishes at a density of 3 × 104 cells and incubated for 24 h. To investigate the blocking effect of XH3C on CSPG4 and ITGA4, A375 cells were incubated with 500 nmol/L XH3C in blank DMEM for 48 h. After washing three times, the cells were fixed with paraformaldehyde solution (4%) for 20 min at room temperature and quenched by 0.1 mol/L glycine for 10 min. After washing three times, 1% BSA and 0.4% TritonX-100 were added in PBS and incubated with A375 cells for 30 min. After washing three times, the cells were incubated with anti-CSPG4 rabbit antibody and anti-ITGA4 mouse antibody overnight at 4 °C. After washing three times, the cells were incubated with the YF594 goat anti-rabbit antibody, YF647 goat anti-mouse antibody, YF488-Phalloidin and Hoechst33342 for 30 min at room temperature. These cells were imaged by confocal microscopy (AXR, Nikon) after washing three times with PBS. Rcoloc values between ITGA4 and CSPG4 were calculated by colocalization threshold in Fiji software.

2.5.4. Determination of the effect of XH3C on ITGA4 distribution

To investigate the effect of XH3C on ITGA4 content on the cell membrane, A375 cells were incubated with 500 nmol/L XH3C in blank DMEM for 48 h. After washing three times, A375 cells were collected with non-enzyme cell detachment solution for 5–7 min, the cells were fixed with paraformaldehyde solution (4%) for 20 min at room temperature and quenched by 0.1 mol/L glycine for 10 min. After washing three times, 1% BSA were added in PBS and incubated with A375 cells for 30 min. After washing three times, the cells were incubated with anti-ITGA4 mouse antibody for 1 h at room temperature. After washing three times, the cells were incubated with the YF647 goat anti-mouse antibody for 30 min at room temperature. After washing three times, the resuspended samples were evaluated using flow cytometry and fluorescence intensity was analyzed using FlowJo software.

2.5.5. Co-immunoprecipitation assay

The ITGA4 antibody was diluted to 5–50 μg/mL. Protein G magnetic beads were incubated with 400 μL of diluted ITGA4 antibody for 30 min at room temperature and washed three times. Cells were lysed using IP lysate solution (supplemented with 1% Tween-20 and 1% Triton X-100), and the protein lysate was collected. Then, 400 μL of protein lysate solution was added to the magnetic beads, along with 500 nmol/L XH3C and an equal volume of DEPC water. The complex was incubated for 30 min at room temperature. Subsequently, the beads were magnetically separated, and the supernatant was discarded. After washing three times, the magnetic beads were mixed with SDS loading buffer and denatured at room temperature for 30 min. The proteins were separated using a 7.5% SDS-PAGE gel. Finally, ITGA4 and CSPG4 antibodies were used for detecting proteins by Western blot with chemiluminescent reporters.

2.5.6. Competition assay based on SG1 peptide

A375 cells were detached with a non-enzyme cell detachment solution, incubated with 250 nmol/L FITC-SG1 peptide (KKEKDIMKKTI), and competed with 250 nmol/L XH3C and 500 nmol/L XH3C in binding buffer (4.5 g of glucose, 100 mg tRNA, 1 g BSA, and 5 mL of 1 mol/L MgCl2 in 1 L of DPBS) for 20 min. The negative control was A375 cells treated with ChABC. Finally, cells were used for flow cytometric analysis. The quantitative results were calculated using FlowJo (v10.8) software and statistically analyzed using GraphPad Prism 8 software.

2.5.7. Cell circularity calculation

Cell contours in confocal microscopy images were labelled with ImageJ software. Then the area and perimeter of each cell were measured with ImageJ software as well. Cell circularity was calculated according to Eq. (6). The statistics analysis was performed by GraphPad Prism 8 software.

| (6) |

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Construction of aptamer libraries mapping A375 membrane proteomes

To generate a molecular library targeting the melanoma membrane proteome, intact cell-based aptamer in vitro evolution method30 was employed against melanoma A375 cells. However, in contrast to the well-established ‘cell-SELEX’ method, only 7 rounds of selection were performed, compared to the more typical 13 or more rounds in traditional cell-SELEX. The goal was to enrich a diverse pool of affinity aptamers that bind to the entire surface of A375 cells for subsequent phenotypic screening, rather than to isolate aptamers with the highest affinity. This design choice is based on a key principle: the strongest affinity binders do not necessarily exhibit the best functional properties31. Additionally, HEK293T cells—characterized by low expression of membrane proteins32—were employed as a negative control to remove binders of commonly shared proteins on cell surfaces (Fig. 2A, Tables S1–S4).

Figure 2.

Construction of aptamer libraries mapping A375 membrane proteomes. (A) Procedures for library construction involved DNA library modification through click chemistry, positive selection, negative selection, and PCR amplification. Libraries obtained after 7 rounds of selection were utilized for sequencing and functional screening. (B) The molecular formula of the click reaction to convert EdU into IndU. (C) Flow cytometry analysis showing aptamer libraries enrichment on target cell A375. (D) Flow cytometry analysis showing no enrichment on control cell HEK293T. (E) Sequencing results showing libraries enrichment round-by-round. (F) Flow cytometry analysis of top 9 aptamers demonstrating robust binding capacities of libraries for A375.

The initial library was designed and synthesized with a 25-nt randomized region composed of four nucleotides in equal proportions, with dT replaced by ethynyl uridine (EdU). The library also contains 21-nt primer binding sites flanking the randomized region, consisting of three regular nucleotides, excluding dT. Additionally, following previously reported methodologies33,34, indole modifications were introduced into the DNA library via copper(I)-catalyzed alkyne-azide cycloaddition (CuAAC or click chemistry) to convert EdU into indole uridine (IndU), thereby enhancing the diversity and applicability of the DNA library (Fig. 2B, Supporting Information Figs. S1 and S2A). To preserve as much sequence information as possible, the screening process was halted when the library showed a slight round-by-round enrichment on target cells A375 but not on control cells HEK293T (Fig. 2C and D).

Sequencing analysis of libraries in each round revealed an increase in enriched species and a reduction of singletons and unique fractions round-by-round (Fig. 2E). To increase the likelihood of discovering functional aptamers, it is essential to ensure robust binding capabilities and high diversity within the aptamer libraries for phenotypic screening. Therefore, highly enriched aptamers originating from different clusters were selected to form the molecular libraries (Supporting Information Tables S5 and S6). The most enriched 96 species were resynthesized with a 96-channel DNA synthesizer. The aptamers were named based on their positions on the 96-well plate. The columns are numbered from 1 to 12, and the rows are labeled from A to H. “XH” is used as a uniform prefix for all aptamers, followed by the column and row labels.

Before the phenotypic screening, the binding ability of the top 9 aptamers to A375 cells was assessed using flow cytometry, and nearly all aptamers exhibited higher fluorescence intensity than the initial library (Fig. 2F). These results suggest the successful construction of molecular libraries mapping the melanoma membrane proteomes, laying the foundation for the potential interference with the biological function of melanoma cells based on their binding capabilities.

3.2. High-throughput phenotypic screening for migration-inhibitory functional aptamers

To evaluate the migration-inhibitory function of the aptamers, a wound healing assay was conducted to assess their impact on cell migration, with the blank area quantified using a high-content imaging instrument (Fig. 3A). Subsequently, a volcano plot was generated to compare the normalized migration inhibition rates (MIR) versus P-values for 96 aptamer candidates at 1 μmol/L, relative to the initial library. Six aptamers with a normalized MIR greater than 20% and a P-value smaller than 0.1 were selected for further concentration-dependent evaluation (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3.

High-throughput phenotypic screening to obtain aptamer XH3C with migration-inhibitory function. (A) Schematic illustration of functional aptamer discovery based on the wound healing assay and high-content analysis. (B) The volcano plot showing the normalized migration inhibition rates and P-values of 96 aptamer candidates. P-values between MIR of aptamers and MIR of Library on each plate were calculated by one-way ANOVA using Graphpad software (P-values: XH3C 0.022, XH3F 0.038, XH3G 0.045, XH4F 0.048, XH7E 0.062, XH11D 0.046). Condition: incubate 1 μmol/L aptamer and library on A375 in blank medium for 36 h after scratching (n = 3) (C) Representative scratch images of XH3C directly showing migration-inhibitory function. (D) Migration inhibition rate curves of XH3C at various administered drug concentrations after 36 h (n = 3). (E) Time-normalized blank area curves of XH3C at different concentrations (n = 3). (F) Binding curves of XH3C to A375 cells (n = 3). (G) Flow cytometry analysis showing robust binding affinity of XH3C to A375. (H) Flow cytometry analysis showing minimal binding affinity of XH3C to HEK293T.

Among all the candidate aptamers, only XH3C exhibited a concentration-dependent migration inhibition effect and other sequences are false positives (Supporting Information Fig. S3). Fig. 3C shows representative scratch images of XH3C demonstrating its migration-inhibitory function. The migration inhibition rate curve at different concentrations and the normalized blank area curve at different times further demonstrated that higher concentrations of XH3C were correlated with a slower migration rate of A375 cells (Fig. 3D and E).

The functional aptamer XH3C obtained can then serve as a molecular tool for research on melanoma migration-associated targets. Given that high affinity and specificity are fundamental for targets identification, the properties of this molecular tool were investigated. The composition and mass of the synthetic oligonucleotide were first examined and confirmed (Supporting Information Figs. S2B and S4). By plotting binding curves, the Kd value of XH3C on A375 cells was estimated to be around 22 nmol/L, indicating high affinity of XH3C (Fig. 3F). In addition, the binding capability of XH3C on A375 was significantly higher than that of the initial library, whereas the two binding capabilities were comparable on HEK293T, indicating the binding specificity of XH3C on A375 (Fig. 3G and H).

Compared to traditional aptamers, this study introduces an indole group into the initial library to mimic the tryptophan side chain found in proteins, thereby increasing the chances of successful aptamer discovery. We discovered that XH3C contains four IndU residues. Curious about the role of IndU in the aptamer, we individually replaced each IndU with regular dT (Supporting Information Table S7). Interestingly, all four IndU residues were found to be critical for binding—any substitution resulted in a decrease in the aptamer's binding capability (Supporting Information Fig. S5A). Furthermore, when we attempted to truncate the XH3C aptamer (Table S7), we found that even removing five bases from the 3′ end and six bases from the 5′ end significantly reduced its binding capacity (Fig. S5B), which means that XH3C inhibits cell migration based on the entire sequences rather than isolated motifs within it. Based on these findings, we chose to continue using the full-length XH3C for further investigation. These properties make XH3C a promising tool for research on melanoma migration-associated targets and bioactive epitopes.

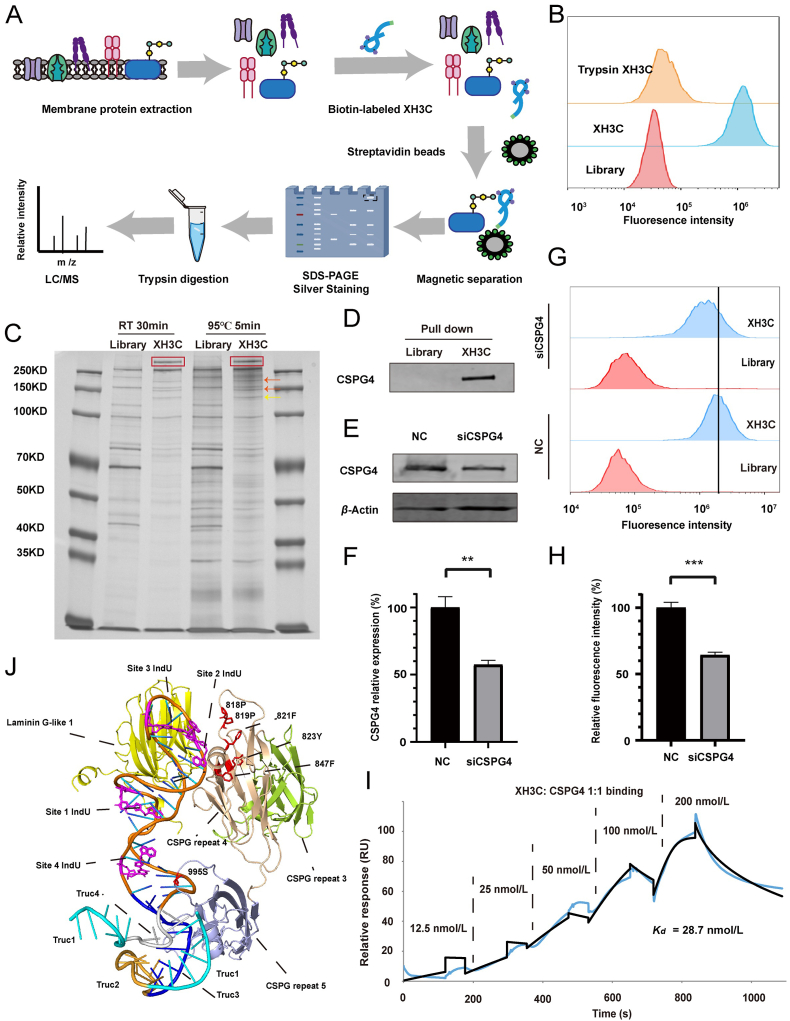

3.3. Identification of CSPG4 as the target of the functional aptamer XH3C

XH3C was utilized in a pull-down experiment, as illustrated in Fig. 4A, to serve as a target discovery tool. To confirm that the binding targets were proteinaceous, trypsin was utilized to deplete membrane proteins before aptamer binding. The results in Fig. 4B indicate that trypsin treatment significantly reduced the binding capacity of XH3C to A375 cells, suggesting that the target of XH3C is a membrane protein. Due to the propensity of membrane proteins to aggregate upon heating35, two denaturation conditions were examined: room temperature (RT) for 30 min and 95 °C for 5 min. Pull-down results revealed a specific band at >250 kDa in the XH3C group under both denaturation conditions, compared to the library group (Fig. 4C). This band was excised, digested, and subjected to mass spectrometry analysis, which identified CSPG4 as the top-ranked protein, matching both its molecular weight and subcellular location (Supporting Information Table S8). Although bands at 130 kDa and approximately 150 kDa were also examined, they did not match the expected molecular weights and subcellular locations. It was speculated that these bands might be cleavage products of CSPG436 or due to nonspecific binding (Supporting Information Tables S9 and S10).

Figure 4.

Identification of CSPG4 as the target of functional aptamer XH3C. (A) Schematic illustration of procedures to identify binding target of XH3C. (B) Analysis of target type through cell membrane proteins digestion by trypsin. (C) Silver-stained SDS-PAGE showing specific band in XH3C group (red rectangle) under two denaturation conditions (room temperature for 30 min and 95 °C for 5 min). Mass spectrometry identified this band as Chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan 4 (CSPG4). Other bands (orange and yellow arrows) were verified as cleavage product of CSPG436 or non-specific binding proteins. (D) Western blotting (WB) of pull-down samples stained with CSPG4 antibody. (E) Typical WB images and (F) quantitative analysis showing that the expression level of CSPG4 was reduced to about 60% by siCSPG4 (n = 3, ∗∗P < 0.01; unpaired Student's t test). (G) Flow cytometry analysis of the binding ability of XH3C on CSPG4-knockdown A375 cells. (H) Quantitative analysis of Fig. 4G showing that the binding ability of XH3C was reduced to about 60% after CSPG4 knockdown, the mean fluorescence intensity was calculated by flowjo (n = 3, ∗∗∗P < 0.001; unpaired Student's t test). (I) SPR experiments measuring Kd value of XH3C and CSPG4 eukaryotic proteins. (J) Structure predictions of CSPG4 and XH3C complex. Structure of CSPG4 was predicted by AlphaFold3.Structure of XH3C was obtained by molecular dynamics simulation. The complex structure was predicted by HDOCK Server. Four interaction protein domains are colored by yellow, wheat, green and light blue. The four IndU sites on XH3C are magentas, while potentially interacting amino acids on the CSPG4 are red. 995S is chondroitin sulfate modification site. Trucation1, 2, 3 and 4 are shown in cyan, gold, blue and gray respectively.

Western blotting confirmed the presence of CSPG4 in pull-down samples, further corroborating that the target of XH3C is CSPG4 (Fig. 4D). Additionally, when CSPG4 expression was reduced by siCSPG4 (Fig. 4E and F), the binding capacity of XH3C to A375 cells decreased to approximately 60% compared to the negative control (NC) (Fig. 4G and H, Supporting Information Fig. S6). Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) was employed to investigate the direct interaction between CSPG4 and XH3C, yielding a Kd value of 29 nmol/L (Fig. 4I), which was comparable to the previously determined value of 22 nmol/L obtained by flow cytometry on cells. These experimental results confirmed that the binding target of aptamer XH3C, functioning as a melanoma migration inhibitor, is CSPG4.

A structural simulation was performed to predict the complex between aptamer XH3C and the CSPG4 protein core (Fig. 4J, Supporting Information Table S11). While the simulation does not perfectly replicate the actual structure, the best-fitting model aligns well with our experimental results. The CAGCACGA sequence (depicted in blue in Fig. 4J) appears to strongly interact with the protein core, which is consistent with our observation that the binding capacity of XH3C Truc3 decreased significantly compared to the longer version (Fig. S5B). Moreover, indole sites 2 and 3 play critical roles in the binding complex (Fig. 4J, Fig. S5A).

According to the simulated structure, regions near the 3′ end (CACCGCAGAGGCA, depicted in gold and cyan in Fig. 4J) and the 5′ end (CACGAC, depicted in cyan in Fig. 4J) contribute minimally to binding. However, when these regions were truncated, a slight reduction in binding was still observed (Fig. S5B). Additionally, although the indole at sites 1 and 4 appears irrelevant to the binding process based on the simulated structure, replacing it with dT resulted in a significant decrease in binding (Fig. S5A). It has been reported that tryptophan, an indole derivative, often forms key interactions within the binding pockets of anticarbohydrate antibodies. It has been suggested that indole favorably binds to the electron poor C-H bonds of carbohydrates, and that complementary electronic effects help drive indole-carbohydrate interactions34. Combining this with the fact that they are in close proximity to the 995S chondroitin sulfate site, it led us to consider whether the aptamer might also interact with other components, such as chondroitin sulfate chains, in addition to the protein core.

3.4. XH3C-induced cytoskeletal rearrangement: blocking the interaction of the bioactive epitope on CSPG4 and ITGA4

Drawing from the aforementioned results, it can be reasonably inferred that CSPG4 serves as a target implicated in melanoma migration. Leveraging our molecular tool XH3C, the quest for identifying the bioactive epitope on CSPG4 is transformed into an exploration the binding site of XH3C. Moreover, delving into the mechanism through which XH3C hampers cell migration via CSPG4 could yield novel therapeutic avenues for tackling melanoma metastasis (Fig. 5A).

Figure 5.

XH3C-induced cytoskeletal rearrangement by inhibiting the interaction between the bioactive epitope chondroitin sulfate chain on CSPG4 and ITGA4. (A) Schematic illustration of mechanism of cell migration inhibition by XH3C. (B) Flow cytometry analysis showing the reduced XH3C binding capacity after chondroitin sulfates digestion by chondroitinase ABC (ChABC). (C) Flow cytometry analysis of the membrane ITGA4 content showing less distribution of ITGA4 on membrane after XH3C treatment. (D) Statistical analysis of Rcoloc between CSPG4 and ITGA4, calculated from multiple fields, showing significant difference between the control group and XH3C group (n = 5 and 6, ∗P < 0.05; unpaired Student's t test). Rcoloc values between CSPG4 and ITGA4 were calculated by Fiji software. (E) Representative immunofluorescent (IF) images showing attenuated co-localization of ITGA4, CSPG4 and F-actin and more distribution of ITGA4 in cytoplasm in the XH3C group. (F) Confocal microscopy images showing F-actin cytoskeleton in A375 cells in the absence and presence of the XH3C aptamer. Cell Contours were used to measure areas and perimeters per cell to calculate cell circularity. (G) Statistical analysis of cell circularity showing significant difference between the control group and XH3C group. (n = 17 and 21, ∗∗∗P < 0.001; unpaired Student's t test). (H) Co-IP (Co-Immunoprecipitation) assay showing the interactions between CSPG4 and ITGA4 in the absence and presence of the XH3C aptamer.

Inspired by the simulated structural data, we investigated the role of the chondroitin sulfate chain in XH3C binding. We found that treating A375 cells with chondroitinase ABC (ChABC) to degrade chondroitin sulfates—removing 90% of the chains (Supporting Information Fig. S7)—resulted in a certain extent of reduction in XH3C binding capacity (Fig. 5B). This suggests that, although XH3C mainly binds to the protein core, the chondroitin sulfates on CSPG4 also play a supporting role in XH3C binding. Further evidence showed that 2 mmol/L of unbound chondroitin sulfates could not compete with the binding of 100 nmol/L XH3C to A375 cells (Supporting Information Fig. S8). These results also indicate that the aptamer primarily binds to the protein core of CSPG4, albeit partially binding to the chondroitin sulfate chains.

Joji Iida et al.37,38 have reported that chondroitin sulfates on CSPG interacted with integrin α4 (ITGA4) to enhance α4β1 integrin-mediated cell adhesion to fibronectin, with the binding site on integrin α4 identified as SG1 (KKEKDIMKKTI). We then investigated if XH3C inhibits cell migration by blocking the interaction between chondroitin sulfate chain on CSPG4 and integrin α4.

Flow cytometry was first performed to assess the levels of membrane-bound ITGA4 protein. It was observed that, after the addition of the aptamer, the distribution of ITGA4 on the membrane was significantly reduced (Fig. 5C), possibly due to the blockage of the interaction between ITGA4 and CSPG4.

To further investigate the effect of the aptamer XH3C on the co-localization of CSPG4 and ITGA4, immunofluorescence (IF) and confocal microscopy were employed. Statistical analysis of the co-localization coefficient (Rcoloc), calculated from multiple fields, revealed a significant difference between the control and XH3C treatment groups (Fig. 5D). In representative images, ITGA4 was partially localized on the cell membrane in the control group, where aggregation and co-localization with CSPG4 and F-actin were observed, forming focal adhesions (white arrow in Fig. 5E). In contrast, in the XH3C treatment group, ITGA4 was predominantly found in the cytoplasm, with reduced co-localization with CSPG4. A decrease in the Rcoloc value was also observed, suggesting reduced co-localization of CSPG4 and ITGA4 compared to the control group (Fig. 5D and E).

Confocal images can also demonstrate the impact of XH3C on cytoskeletal regulation. Broad lamellipodia and spike-like filopodia formation, driven by actin filament polymerization, are hallmark features of aggressive tumor cells. As shown in Fig. 5F, the polarity towards the direction of migration in cell populations untreated with XH3C was evident, indicative of metastasis. Also, F-actin formed longitudinal fibers around the nucleus, parallel to the direction of movement, showing the “ready” state for migration. Following incubating of A375 cells with XH3C, a reduction in lamellipodia and filopodia was observed, accompanied by the disappearance of stress fibers, suggesting a transition away from a metastasis state.

Additionally, more rounded cells were observed in the aptamer-treated group, also showing the impact of XH3C on cytoskeletal regulation (Fig. 5F, Supporting Information Fig. S9). Cell roundness was quantified across multiple fields, and it was found that aptamer treatment caused cells to transition from the irregular shape observed during adhesion to the rounded shape typical of non-adhered cells (Fig. 5G).

Co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) experiments using an ITGA4 antibody for pull-down confirmed that in the presence of XH3C, significantly less CSPG4 interacted with ITGA4, consistent with the immunofluorescence (IF) results (Fig. 5H). Given that XH3C and the SG1 (KKEKDIMKKTI) peptide on integrin α4 share the same ligand, a competition assay based on FITC-SG1 was performed to further elucidate the blocking effect of XH3C on ITGA4 and the chondroitin sulfate chain of CSPG4. To prevent electrostatic interactions between the aptamers and the positively charged peptide, 100 mg of tRNA was added to the binding buffer to neutralize these forces. As shown in Supporting Information Fig. S10, digestion of A375 by ChABC reduced the FITC-SG1 binding capacity, suggesting its interaction with chondroitin sulfates. And more importantly, XH3C competitively inhibited FITC-SG1 binding in a concentration-dependent manner.

The mechanism is starting to take shape. Following post-translational modifications and heterodimerization of immature integrins in the endoplasmic reticulum, only a small portion of mature integrins are transported to the cell membrane as inactive heterodimers39. The chondroitin sulfate chain of CSPG4 may play a role in stabilizing ITGA4 on the membrane, and blocking this interaction with XH3C causes ITGA4 to accumulate in the cytoplasm. By inhibiting the interaction between the chondroitin sulfate epitope on CSPG4 and ITGA4, XH3C induces cytoskeletal rearrangement, which in turn reduces melanoma migration (Fig. 5A).

We performed differential gene expression (DGE) analysis to assess CSPG4 expression in normal tissue, SKCM (Skin Cutaneous Melanoma), and SKCM.Metastasis. Our results show that while CSPG4 is highly expressed in SKCM, there was no significant difference in its levels between SKCM and SKCM.Metastasis (Supporting Information Fig. S11). This initially seemed to contradict our experimental outcomes. However, when considering the chondroitin sulfate chain on CSPG4, which we identified as potentially involved in a migration-associated bioactive epitope, this discrepancy becomes more understandable.

We conducted DGE analysis to evaluate the expression of carbohydrate sulfotransferase (CHST) family members, which are responsible for sulfating the N-acetyl-d-galactosamine (GalNAc) residues of chondroitin polymers. The results revealed predominant expression of nearly all CHSTs in SKCM.Metastasis, with notable differences observed in CHST7, CHST11, CHST12, and CHST15 (Supporting Information Fig. S12). These findings suggest a potential role for chondroitin sulfates in SKCM.Metastasis.

4. Conclusions

In the present work, XH3C was developed both as a melanoma migration inhibitor and a tool for identifying therapeutic targets, enabling the identification of the chondroitin sulfate chain on CSPG4 as a key epitope influencing melanoma migration through its interaction with ITGA4. Despite multiple functional domains of CSPG4—including a core protein that regulates cell growth and motility via Cdc42, Ack-1, p130cas, and sustained Erk1/2 activation40,41—its chondroitin sulfate chain stands out by interacting with integrin α4, which triggers integrin/focal adhesion kinase (FAK) signaling and cytoskeletal reorganization crucial for cell migration36. Moreover, this chain acts as a P-selectin ligand in metastatic breast cancer cells, where its removal significantly reduces lung metastases, underscoring its potential as an anti-metastatic target42.

Given its distinct expression in tumors compared to healthy tissues, CSPG4 serves as an ideal tumor antigen, leading to the development of various CSPG4-targeted therapies such as antibodies, cytolytic fusion proteins, bispecific T-cell engagers (BiTEs), and chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells23. Most therapies target the core protein of CSPG4, which remains unaffected by the removal of chondroitin sulfates23. However, our novel aptamer XH3C specifically targets the protein core and chondroitin sulfates, providing a unique approach for developing new therapeutic strategies like aptamer-conjugated drugs, setting it apart from traditional methods.

Aptamers are increasingly utilized in bioaffinity-based proteomic assays, as exemplified by the successful SOMAscan platform43. In this study, we further explore the potential of aptamers by using them to investigate functional proteins and bioactive epitopes, combining aptamer libraries that map membrane proteomes with phenotypic screening. The facile in vitro evolution process of aptamers makes them especially powerful for studying membrane proteins, allowing us to disrupt specific protein-ligand interactions and potentially blocking cellular crosstalk in co-culture models.

Unlike other molecular tools, aptamers achieve an unparalleled level of throughput in the study of membrane proteins, crucial for discovering new therapeutic targets and epitopes. Generating on-demand small molecule libraries or employing antibody libraries displayed on yeast or phages has its limitations, including depth of coverage and cumbersome in vitro processes. Aptamers can function not only as potential therapeutics or targeting agents but also as pivotal tools in molecular biology for epitope discovery, paving the way for the development of other drug modalities targeting these epitopes. This shifts the drug discovery process from phenotype-based to target-based, establishing a robust paradigm for drug development.

What we present is a chemical biology proof of concept, further investigation into sequences beyond the initial 96 and additional phenotypic screening assays using our constructed library are planned. This FAETI platform will be extended to study other cellular interaction models and may be integrated with existing functional ligands to select epitopes that synergize with known ones, proposing a novel strategy for membrane target discovery through cell-based aptamer evolution and functional screening.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: Hong Xuan, Youbo Zhang and Liqin Zhang; Methodology: Hong Xuan, Siqi Bian, Youbo Zhang and Liqin Zhang; Formal analysis: Hong Xuan, Siqi Bian and Ruidong Xue; Investigation: Hong Xuan, Siqi Bian, Qinguo Liu, Jun Li, Shaojin Li, Sharpkate Shaker, Haiyan Cao, Tongxuan Wei, Panzhu Yao, Yifan Chen, Xiyang Liu and Ruidong Xue; Funding acquisition: Liqin Zhang; Supervision: Youbo Zhang and Liqin Zhang; Validation: Hong Xuan, Siqi Bian; Visualization: Hong Xuan, Siqi Bian; Writing – original draft: Hong Xuan and Liqin Zhang; Writing – review & editing: Hong Xuan and Liqin Zhang. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no competing interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend our thanks to the staff at the Peking University Medical and Health Analysis Center and the State Key Laboratory of Natural and Biomimetic Drugs for their invaluable assistance with instrumental analysis. This work is financially supported by the National Key Research & Development Program of China (Grant No. 2022YFA1304500), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 22227805, 22374004), Excellent Young Scientists Fund Program (Overseas), Clinical Medicine Plus X - Young Scholars Project of Peking University, the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (No. PKU2024LCXQ026, China).

Footnotes

Peer review under the responsibility of Chinese Pharmaceutical Association and Institute of Materia Medica, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences.

Supporting information to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsb.2025.03.003.

Contributor Information

Youbo Zhang, Email: ybzhang@bjmu.edu.cn.

Liqin Zhang, Email: lqzhang@hsc.pku.edu.cn.

Appendix A. Supporting information

The following is the Supporting Information to this article:

References

- 1.Curti B.D., Faries M.B. Recent advances in the treatment of melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:2229–2240. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra2034861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centeno P.P., Pavet V., Marais R. The journey from melanocytes to melanoma. Nat Rev Cancer. 2023;23:372–390. doi: 10.1038/s41568-023-00565-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Van De Sande B., Lee J.S., Mutasa-Gottgens E., Naughton B., Bacon W., Manning J., et al. Applications of single-cell RNA sequencing in drug discovery and development. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2023;22:496–520. doi: 10.1038/s41573-023-00688-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mathewson N.D., Ashenberg O., Tirosh I., Gritsch S., Perez E.M., Marx S., et al. Inhibitory CD161 receptor identified in glioma-infiltrating T cells by single-cell analysis. Cell. 2021;184 doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.01.022. 1281–98.e26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gladka M.M., Molenaar B., De Ruiter H., Van Der Elst S., Tsui H., Versteeg D., et al. Single-cell sequencing of the healthy and diseased heart reveals cytoskeleton-associated protein 4 as a new modulator of fibroblasts activation. Circulation. 2018;138:166–180. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.030742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jones L.H., Bunnage M.E. Applications of chemogenomic library screening in drug discovery. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2017;16:285–296. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2016.244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Terstappen G.C., Schlüpen C., Raggiaschi R., Gaviraghi G. Target deconvolution strategies in drug discovery. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2007;6:891–903. doi: 10.1038/nrd2410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haley B., Roudnicky F. Functional genomics for cancer drug target discovery. Cancer Cell. 2020;38:31–43. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2020.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang Y., Donaher J.L., Das S., Li X., Reinhardt F., Krall J.A., et al. Genome-wide CRISPR screen identifies PRC2 and KMT2D-COMPASS as regulators of distinct EMT trajectories that contribute differentially to metastasis. Nat Cel Biol. 2022;24:554–564. doi: 10.1038/s41556-022-00877-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ye L.P., Park J.J., Dong M.B., Yang Q.J., Chow R.D., Peng L., et al. In vivo CRISPR screening in CD8 T cells with AAV–Sleeping Beauty hybrid vectors identifies membrane targets for improving immunotherapy for glioblastoma. Nat Biotechnol. 2019;37:1302–1313. doi: 10.1038/s41587-019-0246-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lopez-Morales J., Vanella R., Appelt E.A., Whillock S., Paulk A.M., Shusta E.V., et al. Protein engineering and high-throughput screening by yeast surface display: survey of current methods. Small Sci. 2023;3 doi: 10.1002/smsc.202300095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ditzel H.J., Masaki Y., Nielsen H., Farnaes L., Burton D.R. Cloning and expression of a novel human antibody–antigen pair associated with Felty's syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2000;97:9234–9239. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.16.9234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jakobsen C.G., Rasmussen N., Laenkholm A.V., Ditzel H.J. Phage Display–derived human monoclonal antibodies isolated by binding to the surface of live primary breast cancer cells recognize GRP78. Cancer Res. 2007;67:9507–9517. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hansen M.H., Nielsen H., Ditzel H.J. The tumor-infiltrating B cell response in medullary breast cancer is oligoclonal and directed against the autoantigen actin exposed on the surface of apoptotic cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2001;98:12659–12664. doi: 10.1073/pnas.171460798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ma H.T., Liu J.P., Ali M.M., Mahmood M.A.I., Labanieh L., Lu M.R., et al. Nucleic acid aptamers in cancer research, diagnosis and therapy. Chem Soc Rev. 2015;44:1240–1256. doi: 10.1039/c4cs00357h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Berezovski M.V., Lechmann M., Musheev M.U., Mak T.W., Krylov S.N. Aptamer-facilitated biomarker discovery (AptaBiD) J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:9137–9143. doi: 10.1021/ja801951p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang L.Q., Wan S., Jiang Y., Wang Y.Y., Fu T., Liu Q.L., et al. Molecular elucidation of disease biomarkers at the interface of chemistry and biology. J Am Chem Soc. 2017;139:2532–2540. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b10646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Van Simaeys D., Turek D., Champanhac C., Vaizer J., Sefah K., Zhen J., et al. Identification of cell membrane protein stress-induced phosphoprotein 1 as a potential ovarian cancer biomarker using aptamers selected by cell systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment. Anal Chem. 2014;86:4521–4527. doi: 10.1021/ac500466x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu X.Q., Liu H.L., Han D.M., Peng B., Zhang H., Zhang L., et al. Elucidation and structural modeling of CD71 as a molecular target for cell-specific aptamer binding. J Am Chem Soc. 2019;141:10760–10769. doi: 10.1021/jacs.9b03720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dua P., Kang H.S., Hong S.-M., Tsao M.-S., Kim S., Lee D. Alkaline phosphatase ALPPL-2 is a novel pancreatic carcinoma-associated protein. Cancer Res. 2013;73:1934–1945. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-3682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sun X., Xie L., Qiu S.Y., Li H., Zhou Y.Y., Zhang H., et al. Elucidation of CKAP4-remodeled cell mechanics in driving metastasis of bladder cancer through aptamer-based target discovery. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2022;119 doi: 10.1073/pnas.2110500119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wei Y.R., Long S.Y., Zhao M., Zhao J.F., Zhang Y., He W., et al. Regulation of cellular signaling with an aptamer inhibitor to impede cancer metastasis. J Am Chem Soc. 2023;146:319–329. doi: 10.1021/jacs.3c09091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ilieva K.M., Cheung A., Mele S., Chiaruttini G., Crescioli S., Griffin M., et al. Chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan 4 and its potential as an antibody immunotherapy target across different tumor types. Front Immunol. 2018;8:1911. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Suzuki T., Ota Y., Ri M., Bando M., Gotoh A., Itoh Y., et al. Rapid discovery of highly potent and selective inhibitors of histone deacetylase 8 using click chemistry to generate candidate libraries. J Med Chem. 2012;55:9562–9575. doi: 10.1021/jm300837y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tolle F., Rosenthal M., Pfeiffer F., Mayer G. Click reaction on solid phase enables high fidelity synthesis of nucleobase-modified DNA. Bioconjug Chem. 2016;27:500–503. doi: 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.5b00668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.You W.K., Yotsumoto F., Sakimura K., Adams R.H., Stallcup W.B. NG2 proteoglycan promotes tumor vascularization via integrin-dependent effects on pericyte function. Angiogenesis. 2014;17:61–76. doi: 10.1007/s10456-013-9378-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yan Y.M., Zhang D., Zhou P., Li B.T., Huang S.-Y. HDOCK: a web server for protein–protein and protein–DNA/RNA docking based on a hybrid strategy. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:W365–W373. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang Y., Xiong Y.D., Xiao Y. 3dDNA: a computational method of building DNA 3D structures. Molecules. 2022;27:5936. doi: 10.3390/molecules27185936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang Y., Wang J., Xiao Y. 3dRNA: 3D structure prediction from linear to circular RNAs. J Mol Biol. 2022;434 doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2022.167452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shangguan D.H., Li Y., Tang Z.W., Cao Z.C., Chen H.W., Mallikaratchy P., et al. Aptamers evolved from live cells as effective molecular probes for cancer study. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2006;103:11838–11843. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602615103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li J., Yao P.Z., Tang K., Zhao X.Y., Liu X.Y., Liu Q.G., et al. Functional aptamers in vitro evolution for intranuclear blockage of RNA–protein interaction. J Am Chem Soc. 2024;146:24654–24662. doi: 10.1021/jacs.4c08824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thomas P., Smart T.G. HEK293 cell line: a vehicle for the expression of recombinant proteins. J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods. 2005;51:187–200. doi: 10.1016/j.vascn.2004.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tolle F., Brändle G.M., Matzner D., Mayer G. A versatile approach towards nucleobase-modified aptamers. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2015;54:10971–10974. doi: 10.1002/anie.201503652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yoshikawa A.M., Rangel A., Feagin T., Chun E.M., Wan L., Li A., et al. Discovery of indole-modified aptamers for highly specific recognition of protein glycoforms. Nat Commun. 2021;12:7106. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-26933-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tsuji Y. Transmembrane protein Western blotting: impact of sample preparation on detection of SLC11A2 (DMT1) and SLC40A1 (ferroportin) PLoS One. 2020;15 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0235563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Price M.A., Colvin Wanshura L.E., Yang J., Carlson J., Xiang B., Li G., et al. CSPG4, a potential therapeutic target, facilitates malignant progression of melanoma. Pigment Cel Melanoma Res. 2011;24:1148–1157. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-148X.2011.00929.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Iida J., Skubitz A.E.N., Furcht L.T., Wayner E.A., McCarthy J.B. Coordinate role for cell surface chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan and α4β1 integrin in mediating melanoma cell adhesion to fibronectin. J Cel Biol. 1992;118:431–444. doi: 10.1083/jcb.118.2.431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Iida J., Meijne A.M.L., Oegema T.R., Yednock T.A., Kovach N.L., Furcht L.T., et al. A role of chondroitin sulfate glycosaminoglycan binding site in α4β1 integrin-mediated melanoma cell adhesion. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:5955–5962. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.10.5955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kechagia J.Z., Ivaska J., Roca-Cusachs P. Integrins as biomechanical sensors of the microenvironment. Nat Rev Mol Cel Biol. 2019;20:457–473. doi: 10.1038/s41580-019-0134-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Eisenmann K.M., McCarthy J.B., Simpson M.A., Keely P.J., Guan J.L., Tachibana K., et al. Melanoma chondroitin sulphate proteoglycan regulates cell spreading through Cdc42, Ack-1 and p130cas. Nat Cel Biol. 1999;1:507–513. doi: 10.1038/70302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yang J.B., Price M.A., Li G.Y., Bar-Eli M., Salgia R., Jagedeeswaran R., et al. Melanoma proteoglycan modifies gene expression to stimulate tumor cell motility, growth, and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. Cancer Res. 2009;69:7538–7547. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cooney C.A., Jousheghany F., Yao-Borengasser A., Phanavanh B., Gomes T., Kieber-Emmons A.M., et al. Chondroitin sulfates play a major role in breast cancer metastasis: a role for CSPG4 and CHST11gene expression in forming surface P-selectin ligands in aggressive breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Res. 2011;13 doi: 10.1186/bcr2895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gold L., Ayers D., Bertino J., Bock C., Bock A., Brody E.N., et al. Aptamer-based multiplexed proteomic technology for biomarker discovery. PLoS One. 2010;5 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.