Abstract

Background

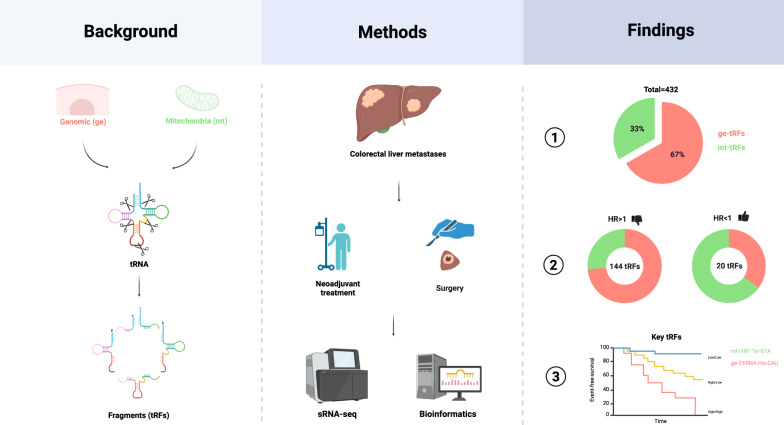

Colorectal liver metastases (CRLM) are the leading cause of colorectal cancer (CRC)-related mortality. Transfer RNA-derived fragments (tRFs), a novel class of small non-coding RNAs (sncRNA), regulate gene expression, stress response, and immune functions in cancer. While increasingly implicated in CRC progression, their prognostic significance in CRLM remains unknown. This study investigates the abundance and prognostic value of genomic (ge) and mitochondrial (mt) tRFs in CRLM.

Methods

Tumor samples from CRLM patients who underwent curative liver resection between January 2012 and December 2015 were retrospectively analyzed. Small RNA sequencing (sRNA-seq) quantified ge- and mt-tRF expression in tumor tissue. Event-free survival (EFS) was the primary outcome. Associations between tRF expression and EFS were evaluated using Cox regression, spline modeling, and network analysis.

Results

Among 588 screened samples, 40 met eligibility criteria (18 females [45%], median age 64 [42–79]). A total of 432 tRFs were identified, with ge-tRFs (67%) more abundant than mt-tRFs (33%). Spline regressions classified tRFs into ten prognostic groups. High ge-tRF abundance was predominantly associated with unfavorable EFS (FDR < 0.2; 94%), while mt-tRFs were significantly (p < 0.001; χ2 test) more often linked to favorable EFS (FDR < 0.2; 26%). Network analysis of tRF abundance correlations revealed higher intra-mitochondrial network density compared to the intra-genomic tRF network. No significant structural differences were observed between prognostically significant vs. non-significant or favorable vs. unfavorable tRFs. Key tRF candidates, including tRHalve3-His-CAU and tRNAleader-Gln-UUG (mt-tRFs), as well as tRFmisc-Tyr-GTA (ge-tRF), remained independent prognostic markers after adjusting for clinical covariates.

Conclusion

This study provides the first comprehensive characterization of tRF expression in CRLM, identifying distinct prognostic roles for ge- and mt-tRFs. While ge-tRFs correlated with poor prognosis, several mt-tRFs were linked to favorable outcomes, highlighting their potential as novel prognostic biomarkers and therapeutic targets.

Graphical Abstract

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12967-025-06850-3.

Keywords: Colorectal liver metastases, CRLM; Small RNA sequencing, sRNA-Seq; tRNA-derived fragments, tRFs; Mitochondrial tRNA-derived fragments, mt-tRFs; Genomic tRNA-derived fragments, ge-tRFs

Introduction

Colorectal liver metastases (CRLM) remain the most common cause of mortality in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer (CRC) [1]. Despite advancements in treatment, approximately 25–30% of CRC patients present with synchronous CRLM and nearly 50% develop metachronous liver metastases following curative resection of the primary tumor [2, 3]. This underscores the urgent need to uncover novel molecular regulators of CRC metastasis that may serve as prognostic markers or therapeutic targets.

Non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) have emerged as key players in cancer progression, with microRNAs (miRNAs) and long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) extensively studied for their roles in CRC metastasis [4]. Recently, transfer RNA-derived fragments (tRFs), a novel class of small non-coding RNAs, have been implicated in cancer biology [5]. Generated from precise cleavage of transfer RNAs (tRNAs), tRFs include tRNA halves (tiRNAs), tRF-5, tRF-3, tRF-1, and internal tRFs (i-tRFs), each of which plays a role in gene regulation, stress adaptation and immune modulation [6–8].

Recent studies highlight the diverse roles of tRFs in CRC metastasis. Certain tRFs are downregulated in CRC, leading to increased tumor invasiveness [9], while others are upregulated under hypoxic conditions, promoting cancer cell migration [10]. Additionally, tRFs contribute to epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) [11], the formation of stress granules (SGs) [12], and immune evasion via immunoediting [13]. Due to their stable and distinct expression patterns in tumors relative to normal tissues, tRFs represent promising biomarkers for CRC diagnosis and metastasis, as evidenced by studies demonstrating their differential expression between CRC and adjacent normal tissues [14–16]. Moreover, high expression of specific tRFs, such as i-tRF-Gly-GCC, has been linked to poor prognosis and early relapse in CRC, reinforcing their relevance as potential biomarkers for disease progression [17].

Despite growing evidence supporting the role of tRFs as regulators of cancer progression and metastasis [18, 19], their distinct origins, either genomic (ge-tRFs) or mitochondrial (mt-tRFs), may confer fundamentally different biological functions. Previous studies have suggested that some tRFs may influence chemotherapy (ChT) response, particularly in relation to 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) treatment resistance in CRC [20, 21], but their role in CRLM-specific therapeutic outcomes remains unclear. Understanding their clinical impact in CRLM could provide insights into their prognostic value, potential as biomarkers, and functional role in tumor progression. If tRFs indeed influence CRLM progression, targeting them through inhibitors, mimetics, or biogenesis modulation could offer new therapeutic strategies for disease management.

Building on our previous work investigating DNA damage, immunogenic cell death (ICD), and endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress in CRLM [22], we aimed to determine the prognostic significance of ge-tRFs and mt-tRFs in this setting. By focusing on their distinct biological roles and differential expression patterns, our study addresses a critical knowledge gap regarding the largely unexplored functional differences between ge-tRFs and mt-tRFs tRFs in CRLM progression. To bridge this gap, we analyzed tRF expression using small RNA sequencing (sRNA-seq) in tumor samples from patients who underwent curative-intent liver resection and assessed their association with clinical outcomes. Our findings reveal that while ge-tRFs are linked to poor prognosis, mt-tRFs may exert protective effects, suggesting distinct functional roles in tumor progression. These insights establish the potential of tRFs as prognostic biomarkers and therapeutic targets, paving the way for personalized treatment strategies and improved risk stratification in CRLM.

Methods

Study design and participants

This study is a retrospective, single-center cohort study conducted at the Division of Visceral Surgery, Department of General Surgery of the Medical University of Vienna. It included all patients with histologically confirmed CRLM who underwent perioperative ChT followed by curative-intent liver resection between January 2012 and December 2015. Both synchronous and metachronous CRLM cases were considered eligible. Patient data were retrieved from a prospectively maintained institutional database.

This study complies with the Reporting Recommendations for Tumor Marker Prognostic Studies (REMARK) guidelines to enhance transparency and reproducibility [23].

Procedures

Perioperative ChT was administered according to the multidisciplinary team (MDT) recommendations. Standard perioperative treatment (POT) included 4 cycles of neoadjuvant FOLFOX (folinic acid, fluorouracil, oxaliplatin) or CAPOX (capecitabine, oxaliplatin) in combination with bevacizumab (for RAS mutant tumors) or cetuximab/panitumumab (for RAS wild-type tumors). The choice of alternative regimens, including FOLFIRI (folinic acid, fluorouracil, irinotecan) or CAPIRI (capecitabine, irinotecan), was guided by patient-specific considerations, such as baseline liver function, necessity for optimal tumor shrinkage before surgery, and ChT-related adverse events (AEs). Radiologic tumor response was evaluated according to the Revised Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) version 1.1 [24]. Parenchymal-sparing non-anatomical resections (NAR), in combination with intraoperative microwave ablation (MWA), were preferred over anatomical resections (AR) whenever feasible. Ultrasonic and energy-based devices (HEPACCS™, Thunderbeat™, or LigaSure™) were used to facilitate these procedures.

Following curative-intent liver resection, adjuvant ChT was usually recommended to complete a total of 6 months of systemic treatment. Postoperative follow-up included multidetector computed tomography (MDCT) of the chest and abdomen as well as carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) measurement every 3–6 months for the first 2 years, followed by every 6–12 months thereafter. In cases of indeterminate hepatic lesions, further evaluation was performed using liver magnetic resonance imaging MRI with diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) and hepatobiliary contrast agent (Primovist®).

Macrodissection of CRLM

Two 10 µm thick formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) sections were extracted under nuclease-free conditions. Macrodissection was done under the guidance of a dedicated hepatobiliary (HBI) pathologist (PK), ensuring tumor purity by removing non-tumor tissue under microscopic guidance.

RNA isolation and sRNA-seq

Total RNA, including small RNAs, was isolated from macrodissected CRLM tissue using the AllPrep DNA/RNA FFPE Kit (QIAGEN) on a QIAcube following the manufacturer's protocol [25]. RNA quantity was assessed using a NanoDrop Eight Spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.) and the QuantiFluor® RNA System (Promega) and quality by a 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies Inc. Libraries for sRNA-Seq were prepared with the NEBNext® Small RNA Library Prep Set for Illumina® (New England Biolabs). Twenty samples were pooled for a 50-base pair (bp) single-read sequencing on a HiSeq 3000 system (Illumina Inc.) to get approximately 20 million reads for each sample (Biomedical Sequencing Facility, Research Center for Molecular Medicine of the Austrian Academy of Sciences). Size selection of the finally pooled libraries was performed by the BluePippin system (Sage Science). Analysis of sRNA subtypes was done using the unitas pipeline (v1.8.0) [26] using the hg38 genomic sequence, the tRF-1 sequence data and the tRNA-leader sequence data versions from 09.04.2019.

Histopathological assessment

Our expert HBI pathologists (PK), blinded to sequencing and clinical data, routinely conducted histopathological assessment using hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained tissue sections. The percentages of tumor necrosis were assessed as previously reported [27]. Hepatic steatosis was defined based on the presence of ≥ 5% steatotic hepatocytes in patient-matched non-tumor liver tissue.

Mutation analysis

Rat sarcoma virus (RAS; inducing KRAS exon 2, 3, 4 and NRAS exon 2, 3) and v-raf murine sarcoma viral oncogene homolog B1 (BRAF; exon 15) was conducted following previously established protocols from the Department of Pathology of the Medical University of Vienna [22, 28]. In brief, genomic DNA was extracted from FFPE tumor samples and amplified using polymerase chain reaction (PCR). The reactions were performed in a Thermocycler (Biometra GmbH) with conditions optimized for target-specific amplification. PCR products were visualized via electrophoresis on 2% agarose gels to confirm amplification success. The amplified DNA fragments were then purified with a MultiScreen® PCR Purification system (Merck Millipore) before undergoing bidirectional sequencing using fluorescent dye-terminator chemistry (Applied Biosystems). Sequence chromatograms were analyzed using SeqScape™ software (Applied Biosystems) for mutation identification. To ensure accuracy, mutation calling followed previously validated criteria and sequence data were manually reviewed for confirmation.

Outcomes

The primary endpoint was event-free survival (EFS), defined as the time from curative-intent liver resection to local/distant recurrence, cancer-related death (excluding secondary primary malignancies), or disease progression. In patients undergoing two-stage hepatectomy (TSH), disease progression was defined as failure to proceed to the second stage. Patients without recurrence, progression, or death were censored at their last follow-up.

Bioinformatics and statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using R (v4.3.1) [29]. A two-sided p-value ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant, and multiple testing was addressed using the Benjamini–Hochberg false discovery rate (FDR) method, with an FDR threshold of 0.2. We applied an FDR threshold of 0.2 to balance discovery with type I error control, acknowledging the exploratory intent of this initial study. Follow-up time was calculated using the reverse Kaplan–Meier method [30]. Missing clinicopathological variables were imputed using predictive mean matching (pmm) via the “mice” R package (v3.16.0). tRF quantification and preprocessing were based on raw read counts obtained via the unitas pipeline [26]. tRFs were filtered to retain only those with more than six distinct non-zero counts across samples. After adding a pseudocount (0.5), values were log2-transformed, yielding a final set of 432 tRFs for downstream analyses. A pseudocount of 0.5 was added to stabilize variance for low-abundance tRFs, as recommended in sRNA-seq data analysis and to allow log2-transformation of zero count values. tRFs were retained if they had more than six distinct non-zero counts across samples, to ensure robust downstream statistical modeling. To assess prognostic relevance, we applied multivariable Cox proportional hazards models using each tRF as a penalized smoothing spline (two degrees of freedom) to flexibly capture nonlinear associations with EFS. Optimal dichotomization cut-points for each tRF were identified using the “cutp” function from the “survMisc” R package (v0.5.6). The following clinicopathologic covariates were included as potential confounders: sex (male, female), metastases timepoint (synchronous, metachronous), neoadjuvant antibody (Cetuximab/Panitumumab, Bevacizumab), liver resection (minor, major), primary tumor location (left, right) and RAS status (mutant, wild-type). Spline curves for all tRFs were scaled and plotted. Dichotomized hazard ratios (HRs) and raw p-values for each tRF were compiled into a summary table; p-values were FDR-adjusted. Scaled spline curves were clustered using k-means clustering (k = 14) via the “kml” R package (v2.5.0) with 10,000 iterations to avoid local minima. Following visual inspection, similar clusters were merged, resulting in ten final clusters used in subsequent analyses. These are illustrated in Fig. 2A, showing directionality of effect on EFS (HR < 1, favorable; HR > 1, unfavorable). tRF subtype composition per cluster is presented as radar plots (Fig. 2B). To adjust for clinical heterogeneity, 13 clinicopathologic variables (five continuous and eight binary) were condensed into three principal components (PCs) using the “PCAmix” function from “PCAmixdata” R package (v3.1), explaining 49.9% of variance. These PCs were modeled as natural cubic splines (three degrees of freedom) using the “splines” R package (v4.4.0), and final models were optimized using backward stepwise selection “stepAIC” from the “MASS” R package, (v7.3–65), minimizing the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC).

Fig. 2.

Abundance and prognostic patterns of ge- and mt-tRFs in CRLM. A Spline regression estimates demonstrate the interaction between event-free survival (EFS) and abundance of genomic (ge) and mitochondrial (mt) tRFs. The tRFs are classified into different clusters according to the hazard ratio (HR) curve patterns. The x-axis shows the scaled levels of tRFs abundance, while the y-axis presents the HRs. The tRFs are highlighted as turquoise for mt-tRFs and red for ge-tRFs, if they were significantly associated with EFS (FDR < 0.2). Solid lines represent HR > 1 (unfavorable prognosis) and dashed lines represent HR < 1 (favorable prognosis). B Radar charts present the composition of tRF types in each of the spline clusters

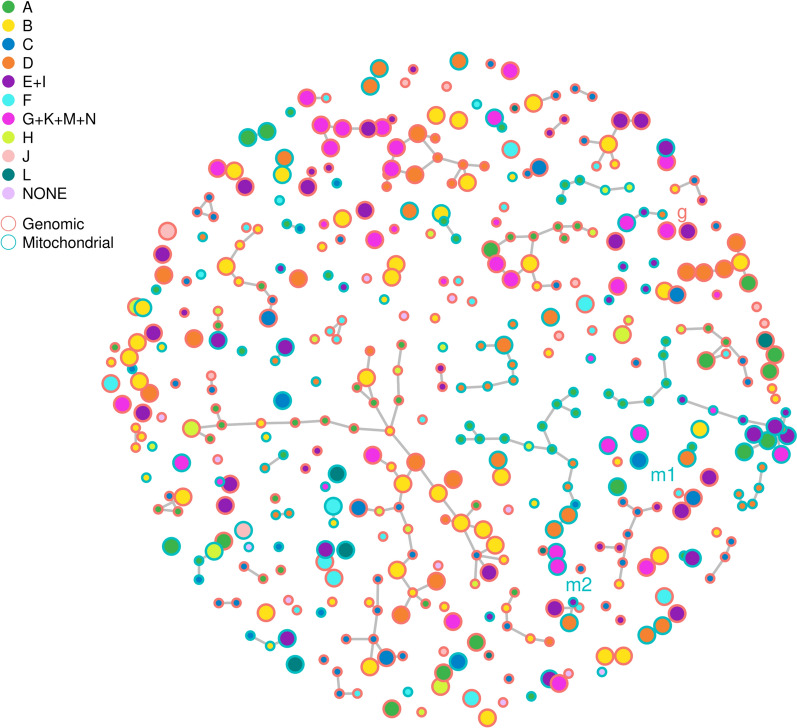

For network-based clustering of tRF abundance, we applied the “selectFast” function from “GGMselect” R package (v0.1–12.7.1) to estimate a Gaussian graphical model based on conditional independence structure. The penalization parameter K was tuned (range: 2–14), and finally K = 8 was selected. The resulting network was visualized and annotated by cluster membership (node color) and EFS association (node size: larger for significant associations). The final selected tRFs for modeling are labeled g (genomic), m1 (mitochondrial), and m2 (mitochondrial). Node outline color distinguishes tRF origin: red, genomic; blue, mitochondrial.

Network topology and cluster structure were analyzed using permutation-based null distributions via the “igraph” R package (v2.1.4), enabling robust comparison of observed network features against empirical expectations.

Results

Patients exhibit standardized treatment exposure and balanced demographics

A total of 588 patients were screened for eligibility, of whom 40 met the criteria for final data analyses. The study design and CONSORT flow diagram are presented in Fig. 1. The median age was 64 (range 42–79), with a gender distribution of 55% male and 45% female. The predominant POT was FOLFOX/CAPOX (65%) and bevacizumab (62%). The median follow-up time was 53 months (95% CI 37-NR). Baseline characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Fig. 1.

Study design and CONSORT flow diagram. A Study design. B CONSORT flow diagram. FFPE, formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded; sRNA-seq, small RNA sequencing; CRLM, colorectal liver metastases

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| Total No | 40 | |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years, median (range) | 64 | (42–79) |

| Sex, No. (%) | ||

| Male | 22 | (55) |

| Female | 18 | (45) |

| BMI, median (range) | 26 | (20–35) |

| Primary tumor location, No. (%) | ||

| Left | 34 | (85) |

| Right | 6 | (15) |

| Tumor differentiation, No. (%) | ||

| Moderate (G2) | 30 | (75) |

| Poor (G3) | 7 | (17) |

| Unavailable | 3 | (7) |

| pT stage, No. (%) | ||

| pT1 | 2 | (5) |

| pT2 | 9 | (22) |

| pT3 | 23 | (57) |

| pT4 | 3 | (7) |

| Unavailable | 3 | (7) |

| pN stage, No. (%) | ||

| pN0 | 13 | (32) |

| pN1/2 | 24 | (60) |

| Unavailable | 3 | (7) |

| Metastases timepoint, No. (%) | ||

| Synchronous | 23 | (57) |

| Metachronous | 17 | (43) |

| Distribution, No. (%) | ||

| Unilobular | 24 | (60) |

| Bilobular | 16 | (40) |

| Liver lesions, median No. (range) | 3 | (1–15) |

| Neoadjuvant chemotherapy, No. (%) | ||

| FOLFOX/CAPOX | 26 | (65) |

| FOLFIRI/CAPIRI | 14 | (35) |

| Neoadjuvant antibody, No. (%) | ||

| Bevacizumab | 25 | (62) |

| Cetuximab/panitumumab | 15 | (37) |

| Neoadjuvant cycles, median No. (range) | 4 | (2–12) |

| Radiographic therapy response, No. (%) | ||

| Good response (CR, PR) | 34 | (85) |

| Poor response (SD, PD) | 5 | (12) |

| Unavailable | 1 | (2) |

| Liver resection, No. (%) | ||

| Minor (≤ 3 segments) | 16 | (60) |

| Major (> 3 segments) | 24 | (40) |

| Tumor differentiation, No. (%) | ||

| Moderate (G2) | 35 | (87) |

| Poor (G3) | 5 | (12) |

| Tumor necrosis, No. (%) | ||

| Good response (≥ 50%) | 20 | (50) |

| Poor response (< 50%) | 20 | (50) |

| Steatosis, No. (%) | ||

| Absent | 14 | (35) |

| Present (≥ 5%) | 24 | (60) |

| Unavailable | 2 | (5) |

| RAS status, No. (%) | ||

| Wild-type | 24 | (60) |

| Mutant | 10 | (25) |

| Unavailable | 6 | (15) |

| BRAF status, No. (%) | ||

| Wild-type | 33 | (82) |

| Unavailable | 7 | (17) |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy, No. (%) | ||

| Yes | 34 | (85) |

| No | 3 | (7) |

| Unavailable | 3 | (7) |

| Median follow-up time, months (95% CI) | 53 | (37-NR) |

| Median event-free survival (EFS), months (95% CI) | 16 | (11–22) |

Percentages were intentionally rounded down to ensure the total does not exceed 100%

BMI: body-mass-index; FOLFOX: folinic acid, fluorouracil, oxaliplatin; CAPOX: capecitabine, oxaliplatin; FOLFIRI: folinic acid, fluorouracil, irinotecan; CAPIRI: capecitabine, irinotecan; PD: progressive disease; PR: partial response; SD: stable disease; RAS: rat sarcoma virus; BRAF: v-raf murine sarcoma viral oncogene homolog B1; CI: confidence interval; NR: not reached

Ge-tRFs are more abundant and predominantly associated with adverse prognosis compared to mt-tRFs

To investigate the prognostic relevance of tRFs in patients with CRLM, we performed sRNA-seq and quantified 696 distinct tRFs using the unitas pipeline. These included 392 genomic tRFs (ge-tRFs, 56%) and 304 mitochondrial tRFs (mt-tRFs, 44%). After filtering for absent expression, 432 tRFs remained for downstream analysis, comprising 288 ge-tRFs (67%) and 144 mt-tRFs (33%) (Supplementary Table 1). To evaluate the relationship between tRF abundance and EFS, we modeled each tRF using Cox regression with second-order natural polynomial splines, allowing for non-linear effects. The resulting spline curves were clustered into 14 distinct groups using iterative k-means clustering (“kml” R package v2.4.1). Based on interpretability, ten curated clusters were condensed and used for further analyses (Fig. 2A). These clusters represent distinct patterns of hazard ratio curves, such as linear, plateauing, and exponential, capturing the heterogeneity in prognostic associations across tRFs. Subsequently, each tRF was dichotomized into high- and low-abundance categories using optimal cut-off values determined by the smallest p-value of the (log-rank) statistic (“cutp” function of the “survMisc” R package v0.5.6). These values were then used in univariate and multivariable Cox regression analyses, adjusting for clinicopathological covariates. Raw p-values were adjusted using the FDR method [31]. Of the 432 tRFs analyzed, 164 (38%) were significantly associated with EFS at FDR < 0.2, including 113 ge-tRFs (26%) and 51 mt-tRFs (12%). This included 113 out of 288 ge-tRFs (39%) and 51 out of 144 mt-tRFs (35%). Among these, 94% of ge-tRFs (n = 106) were associated with poor prognosis (HR > 1), whereas 26% of mt-tRFs (n = 13) were linked to favorable prognosis (HR < 1). These tRFs displayed heterogeneous prognostic trajectories across the spline groups, indicating non-uniform effects on EFS in CRLM.

To visualize the distribution of prognostic tRF subtypes, radar charts were generated for each curated spline group (Fig. 2B). Group B contained the largest number of significant tRFs (n = 35), with 34 showing an adverse association with EFS (HR > 1); nearly all were ge-tRFs (n = 31). Similar trends were observed in groups E + I and G + K + M + N (n = 19 and n = 20, respectively), which were also dominated by ge-tRFs associated with worse prognosis. Subtypes most commonly linked to poor outcomes included tRF3 (ge: n = 26; mt: n = 12), tRFmisc (ge: n = 25; mt: n = 9), and tRF5 (ge: n = 22; mt: n = 4), frequently localized to spline groups B, E + I, F, and G + K + M + N. In contrast, tRFs associated with favorable outcomes (HR < 1) were predominantly mt-tRFs, particularly tRF3_CCA (mt: n = 4; ge: n = 2), tRNAleader (mt: n = 3; ge: n = 2), and tRHalve3 (mt: n = 2; ge: n = 1), with enrichment in groups A (n = 8), C (n = 5), and J (n = 2). Group D showed a balanced representation of ge- and mt-tRFs (n = 14 each), although 27 of the 28 tRFs in this group were associated with adverse outcomes (HR > 1). Mixed trends were observed in Groups A and C, where protective and adverse associations were nearly balanced (group A: 8 HR > 1 vs. 7 HR < 1; group C: 5 vs. 5). Among protective tRFs, tRF3_CCA emerged as a notable mt-tRF subtype.

Overall, ge-tRFs were more frequently associated with adverse prognosis (HR > 1), while mt-tRFs were more often linked to favorable EFS. These divergent distributions were particularly evident in groups B and E + I (HR > 1) and groups A and C (HR < 1). The overall HR by spline and tRF subtype is depicted in Supplementary Fig. 1.

Mt-tRFs exhibit higher network connectivity than ge-tRFs, independent of prognostic relevance

To explore abundance-based relationships among tRFs, a correlation network analysis was performed using Gaussian Graphical Models (GGMs). Pairwise correlations between tRF abundances were computed, and a final model of meaningful associations was selected by minimizing conditional least squares, an empirical model selection criterion. In the resulting network, tRFs are represented as nodes, and significant correlations above background are shown as edges (Fig. 3). The network constructed from 293 ge-tRFs comprised 292 edges, while the 146 mt-tRFs formed a network with 124 edges. Notably, nearly all correlations occurred within ge- or mt-tRF groups. Only a single edge connected a ge-tRF (tRF3-Tyr-ATA) and a mt-tRF (tRF3-Val-GUN). This topology resulted in a significantly denser intra-mitochondrial network compared to the intra-genomic network (Supplementary Fig. 2). Supplementary Figs. 3 and 4 further illustrate the size and degree distributions of subnetworks across both tRF types, where no significant differences in network size or connectivity distribution were observed. Moreover, when comparing EFS-associated vs. non-EFS-associated tRFs (as defined by FDR < 0.2 in prior analyses), no significant differences in intra-group network density were detected for either mitochondrial or genomic tRFs. These comparisons were evaluated using permutation testing (Supplementary Figs. 5–6).

Fig. 3.

Mt-tRFs form denser correlation networks than ge-tRFs, independent of prognostic relevance. A correlation network of tRF abundances, with nodes colored by spline groups and outline-colored by either genomic (red) or mitochondrial (turquoise) origin. The significant tRFs are represented by large nodes, while the small nodes indicate non-significance. The ge-tRFs and the two mt-tRFs used for Cox-regression models are indicated by labels g and m1 or m2, respectively

These findings indicate that while mitochondrial tRFs exhibit greater internal connectivity than genomic tRFs, this structural network difference does not appear to reflect or stratify prognostic relevance in CRLM.

Key ge- and mt-tRFs remain independent prognostic markers after clinical adjustment

To assess whether individual tRFs retain independent prognostic value for EFS after adjusting for clinical covariates, two multivariable Cox regression models were constructed. In model one, the most strongly EFS-associated ge- and mt-tRFs (FDR < 0.1), both individually linked to worse prognosis (HR > 1), were selected. In model two, the most unfavorable ge-tRF (HR > 1) was paired with the most favorable mt-tRF (HR < 1, FDR < 0.2). To account for clinical confounding, 13 clinicopathologic variables were reduced via principal component analysis (PCA), and the first three principal components (PC1-PC3) were modeled as natural splines in both multivariable Cox regression models.

In both models, both tRFs remained independently associated with EFS following adjustment. In model one, both tRFmisc-Tyr-GTA (ge-tRF) and tRHalve3-His-CAU (mt-tRF) were retained alongside clinical PC1. In model two, tRFmisc-Tyr-GTA (ge-tRF) and tRNAleader-Gln-UUG (mt-tRF) remained significant together with PC1 and PC3. The forest plot for model one is shown in Fig. 4A, and survival curves for combined high/low expression groups are shown in Fig. 4B. Corresponding plots for model two are provided in Supplementary Figs. 7A and 7B, with full results of univariate and final multivariable models are summarized in Supplementary Table 2.

Fig. 4.

Ge- and mt-tRFs remain independent prognostic markers after adjustment for clinical covariates. A Multivariable Cox regression model (backward selected) was used to predict event-free survival (EFS) based on the ge-tRF and mt-tRF, with each having the highest hazard ratios (HR), while adjusting for clinical factors summarized as principal components (PC1, PC2, and PC3). The forest plot shows the HR (black points) and the 95% CI (black horizontal lines). The grey vertical line is at HR = 1 (no effect), and the significance is indicated when the 95% CI does not cross the line at one. B Survival curves dividing patients into three groups according to the relative levels of the dichotomized ge-tRF (g) and mt-tRF (m) abundances, being low (L) or high (H): red, both high; green, one high, one low; and blue, both low

These findings reinforce the independent prognostic value of both mitochondrial and genomic tRFs, underscoring their potential utility in molecular risk stratification for patients with CRLM.

Discussion

In this study, we systematically analyzed the expression profiles and prognostic relevance of ge- and mt-tRFs in CRLM. Small RNA-seq identified 432 expressed tRFs, comprising 67% ge-tRFs and 33% mt-tRFs. Strikingly, high ge-tRF expression was predominantly associated with unfavorable EFS, with 94% of EFS-associated ge-tRFs linked to poorer outcomes (HR > 1). In contrast, 26% of EFS-associated mt-tRFs were correlated with favorable (HR < 1) prognosis (difference to favorable EFS among ge-tRFs: p = 0.001). These findings underscore biological distinctions between ge- and mt-tRFs and suggest their potential clinical utility as prognostic biomarkers and therapeutic targets in CRLM.

Using a spline modeling approach, we classified tRFs into ten prognostic clusters based on tRF-EFS spline curve-type patterns. High ge-tRFs abundances were predominantly associated with unfavorable EFS, specifically in clusters B, E + I, and G + K + M + N. This suggests that ge-tRFs are associated with or may co-activate oncogenic pathways involved in tumor growth and metastasis. Prior studies have demonstrated that certain ge-tRFs, such as tRF-Phe-GAA-031 and tRF-Val-TCA-002, are markers of metastasis and poor prognosis in CRC [11]. Among tRF subtypes, tRF3, tRFmisc, and tRF5 were associated with adverse outcomes, aligning with previous findings that tRF levels are elevated in CRC tissues compared to non-tumoral tissues [15, 16]. Furthermore, specific tRFs have been implicated in tumor progression under hypoxic conditions. For example, hypoxia-induced 5′-tiRNA-His-GTG accelerates CRC progression by regulating large tumor suppressor kinase 2 (LATS2) and reversing the Hippo signaling [32]. Similarly, tRF-20-M0NK5Y93, which is downregulated under hypoxia, suppresses CRC migration and invasion by targeting Claudin-1, a key EMT-related molecule [33]. These findings further support the complex interplay between tRFs and the tumor microenvironment (TME), particularly in stress-induced metastatic processes. Additionally, stress-induced 5′-tiRNA-Val, processed by angiogenin (ANG), has been linked to CRC metastasis [34], and tRF5-Gly-GCC has been shown to enhance ChT efficacy to 5-FU by regulating transcription factor Spi-B (SPIB) and activating the Janus kinase 1 (JAK1)/signal transducer and activator of transcription 6 (STAT6) signaling pathway [20, 21].

Conversely, approximately 26% of mt-tRFs were associated with a favorable prognosis at high abundance, particularly within clusters A, C, H, and J, suggesting a potential tumor-suppressive role for specific mitochondrial tRFs. Specifically, the mt-tRF3-CCA subtype was associated with improved EFS, which may be related to mitochondrial homeostasis and stress-induced tumor suppression. However, research on protective mt-tRFs in CRC remains limited. Previous studies suggest that some tRFs, particularly those induced by hypoxia or cellular stress, can silence oncogenic transcripts and modulate immune editing. For instance, tRF-Asp-GTC, tRF-Glu-YTC and tRF-Gly-TCC downregulate oncogenic transcripts by competing for RNA-binding proteins, such as Y-box binding protein 1 (YB-1) [12]. Since YB-1 is a key regulator of SG formation rather than a direct translational repressor [35], these findings suggest that tRFs may function through mechanisms distinct from conventional stress-induced translation inhibition, potentially influencing tumor progression via RNA-binding protein (RBP) interactions. Additionally, tRNA-Leu-derived tRF/miR-1280 suppresses CRC stemness and metastasis through Notch signaling [9]. This aligns with studies showing that tRF/miR-1280, along with tRNA-Val-AAC/CAC and tRNA-Asp-GTC, are significantly downregulated in tumor tissues compared to adjacent normal tissues, with particularly low expression in stage IV CRC patients [36]. These observations further support the tumor-suppressive role of certain tRFs and their potential as biomarkers for metastatic disease. Similarly, tRF3-Val-3008A has been shown to inhibit tumor growth by reducing forkhead box class K1 (FOXK1) stability through an argonaute (AGO)-dependent mechanism [37]. In addition, tRF-3022b has been found to influence CRC tumor progression and M2 macrophage properties by modulating cytokine interactions [38], underscoring the diverse mechanisms by which tRFs regulate the TME.

Network analysis further supported these opposing roles of ge- and mt-tRFs. Protective spline groups (A, C, and H) formed small, sparsely connected clusters of mt-tRFs, while adverse groups (B, E + I, and G) were characterized by large, highly interconnected ge-tRF clusters, suggesting potential co-regulatory mechanisms. The observation that mt-tRFs form denser internal networks, yet do not show a direct correlation with prognostic relevance, may indicate compensatory or buffering mechanisms within mt-RNA processing. Further studies should explore whether such network features reflect functional redundancy or alternative regulatory pathways in mt-tRF biology. Importantly, the top mt-tRF candidate (tRhalve3-His-CAU/C) and ge-tRF candidate (tRFmisc-Tyr-GTA) remained significant poor EFS prognostic markers even after adjustment for clinical covariates. This finding aligns with previous research identifying i-tRF-GlyGCC as a prognostic biomarker in CRC, where high expression correlates with shorter disease-free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS), maintaining prognostic significance independent of other established factors [17]. Together, these findings suggest that ge-tRFs contribute to the malignant phenotype in CRLM, while some mt-tRFs may exert tumor-suppressive effects.

Despite the insights gained from this study, several limitations must be acknowledged. The relatively small sample size necessitates validation in larger, independent, and preferably multicenter cohorts to confirm the generalizability and clinical utility of our findings. Additionally, it is important to emphasize that this study is correlative in nature, and thus the suggested oncogenic roles of ge-tRFs and tumor-suppressive roles of mt-tRFs are based solely on prognostic associations without direct functional evidence. Interpretations regarding biological mechanisms should therefore be considered speculative at this stage. Future research should explicitly aim to perform mechanistic validations using approaches such as CRISPR interference (CRISPRi), tRF mimetics, or targeted experimental assays. In particular, candidates such as mt-tRF3-CCA warrant functional investigation to validate their roles in immune modulation, EMT, mitochondrial function, and overall tumor biology. Recent studies have highlighted the therapeutic potential of exogenous tRF mimics derived from non-pathogenic Escherichia coli (E. coli), demonstrating anti-tumor efficacy even against 5-FU resistant CRC cells [39]. These findings raise the possibility of utilizing tRF-based therapies, alone or in combination with chemotherapy or immunotherapy, as novel strategies to overcome treatment resistance in CRLM.

Conclusion

This study provides new insights into the distinct expression patterns and prognostic significance of ge- and mt-tRFs in CRLM. The differential roles of these tRFs highlight their potential as biomarkers and therapeutic targets, paving the way for improved prognostic tools and novel treatment strategies aimed at enhancing patient outcomes in CRLM.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our deepest appreciation to Andreas Winter, Ruth Bogusch, and Cara Lade for their invaluable assistance in collecting FFPE tissue blocks from the repository. We are also grateful to Margit Schmeidl (Department of Pathology, Medical University of Vienna) for her expertise and support in cutting the FFPE tissue blocks. We sincerely thank Martin Bilban and Markus Jeitler (Core Facility Genomics-RNA, Medical University of Vienna) for their contributions to sample quality control. We also extend our gratitude to Michael Schuster and Alberto Alises (BSF, CeMM, Austrian Academy of Sciences) for their generous assistance with the next-generation sequencing-related work. Additionally, we would like to acknowledge all members of our research group for their valuable input, insightful discussions, and continuous support throughout this project. Some parts of the figures were created using BioRender.com and Prism version 10.4.1 (GraphPad).

Abbreviations

- 5-FU

5-Fluorouracil

- AEs

Adverse events

- AGO

Argonaute

- AR

Anatomical resections

- BP

Base pair

- CAPIRI

Capecitabine, irinotecan

- CAPOX

Capecitabine, oxaliplatin

- CEA

Carcinoembryonic antigen

- ChT

Chemotherapy

- CI

Confidence interval

- CRISPRi

CRISPR interference

- CRLM

Colorectal liver metastases

- CRC

Colorectal cancer

- DFS

Disease-free survival

- DWI

Diffusion-weighted imaging

- EFS

Event-free survival

- EMT

Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition

- ER

Endoplasmic reticulum

- FFPE

Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded

- FOLFIRI

Folinic acid, fluorouracil, irinotecan

- FOLFOX

Folinic acid, fluorouracil, oxaliplatin

- FDR

False discovery rate

- FOXK1

Forkhead box protein K1

- GEO

Gene expression omnibus

- ge-tRFs

Genomic tRNA-derived fragments

- GGM

Gaussian graphical model

- GSP

Good scientific practice

- H&E

Hematoxylin and eosin

- HBI

Hepatobiliary

- HR

Hazard ratio

- ICD

Immunogenic cell death

- ICF

Informed consent form

- i-tRF

Internal tRNA-derived fragment

- IRB

Institutional review board

- JAK1

Janus kinase 1

- lncRNAs

Long non-coding RNAs

- MDCT

Multidetector computed tomography

- MDT

Multidisciplinary team

- miRNAs

MicroRNAs

- mt-tRFs

Mitochondrial tRNA-derived fragments

- MWA

Microwave ablation

- NAR

Non-anatomical resections

- ncRNAs

Non-coding RNAs

- NDA

Non-disclosure agreement

- NR

Not reached

- OS

Overall survival

- PCA

Principal component analysis

- PCs

Principal components

- PCR

Polymerase chain reaction

- PHI

Protected health information

- POT

Perioperative treatment

- RECIST

Response evaluation criteria in solid tumors

- REMARK

Reporting recommendations for tumor marker prognostic studies

- RNA

Ribonucleic acid

- sRNA-seq

Small RNA sequencing

- SGs

Stress granules

- sncRNA

Small non-coding RNA

- SPIB

Spi-B transcription factor

- STAT6

Signal transducer and activator of transcription 6

- tRFs

TRNA-derived fragments

- tiRNAs

TRNA halves

- TME

Tumor microenvironment

- TNM

Tumor, node, metastasis (staging system)

- TSH

Two-stage hepatectomy

- YB-1

Y-box binding protein 1

Author contributions

All authors contributed substantially to the study's design, data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation. Each author participated in drafting and critically revising the manuscript and has approved the final version for submission. All authors take full responsibility for the accuracy and integrity of this work in all its aspects.

Funding

This study was partially supported by the Georg Stumpf Scholarship from the Austrian Society of Surgical Oncology (ACO-ASSO) and a Research Scholarship from Fellinger Cancer Research, both awarded to JL. Additional support was provided by a Research Fund from Roche, granted to KK, as well as general Research Funds from the Division of Visceral Surgery, Department of General Surgery of the Medical University of Vienna. The funding organizations had no involvement in the study design, data acquisition, analysis, interpretation, manuscript preparation or the decision to submit this work for publication.

Availability of data and materials

All small RNA sequencing data generated in this study are publicly available in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) repository under accession number GSE293849. Anonymized data will be made available upon reasonable academic request. Protected health information (PHI) will not be disclosed. Investigators seeking access to the data must contact the corresponding author, provide proof of approval from their institution’s local institutional review board (IRB), and sign a non-disclosure agreement (NDA).

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval was granted by the institutional review board (IRB) of the Medical University of Vienna (No. 1374/2014). The study was conducted in strict accordance with Good Scientific Practice (GSP) guidelines of the Medical University of Vienna and the most recent Declaration of Helsinki. Due to its retrospective design, the requirement for individual patient informed consent (ICF) was waived by the IRB.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interest related to the content of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Wagle NS, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J Clin. 2023;73:17–48. 10.3322/caac.21763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Manfredi S, Lepage C, Hatem C, et al. Epidemiology and management of liver metastases from colorectal cancer. Ann Surg. 2006;244:254–9. 10.1097/01.sla.0000217629.94941.cf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Van Cutsem E, Cervantes A, Adam R, et al. ESMO consensus guidelines for the management of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Ann Oncol Off J Eur Soc Med Oncol. 2016;27:1386–422. 10.1093/annonc/mdw235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Slack FJ, Chinnaiyan AM. The role of non-coding RNAs in ONCOLOGY. Cell. 2019;179:1033–55. 10.1016/j.cell.2019.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haussecker D, Huang Y, Lau A, et al. Human tRNA-derived small RNAs in the global regulation of RNA silencing. RNA. 2010;16:673–95. 10.1261/rna.2000810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saikia M, Krokowski D, Guan B-J, et al. Genome-wide identification and quantitative analysis of cleaved tRNA fragments induced by cellular stress. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:42708–25. 10.1074/jbc.M112.371799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ivanov P, Emara MM, Villen J, et al. Angiogenin-induced tRNA fragments inhibit translation initiation. Mol Cell. 2011;43:613–23. 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thompson DM, Parker R. Stressing out over tRNA cleavage. Cell. 2009;138:215–9. 10.1016/j.cell.2009.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang B, Yang H, Cheng X, et al. tRF/miR-1280 suppresses stem cell-like cells and metastasis in colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 2017;77:3194–206. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-3146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Luan N, Mu Y, Mu J, et al. Dicer1 promotes colon cancer cell invasion and migration through modulation of tRF-20-MEJB5Y13 expression under hypoxia. Front Genet. 2021;12: 638244. 10.3389/fgene.2021.638244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen H, Xu Z, Cai H, et al. Identifying differentially expressed tRNA-derived small fragments as a biomarker for the progression and metastasis of colorectal cancer. Dis Mark. 2022;2022:2646173. 10.1155/2022/2646173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goodarzi H, Liu X, Nguyen HCB, et al. Endogenous tRNA-derived fragments suppress breast cancer progression via YBX1 displacement. Cell. 2015;161:790–802. 10.1016/j.cell.2015.02.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chiou NT, Kageyama R, Ansel KM. Selective export into extracellular vesicles and function of tRNA fragments during T cell activation. Cell Rep. 2018;25:3356-3370.e4. 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.11.073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ye C, Cheng F, Huang L, et al. New plasma diagnostic markers for colorectal cancer: transporter fragments of glutamate tRNA origin. J Cancer. 2024;15:1299–313. 10.7150/jca.92102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang X, Zhang Y, Ghareeb WM, et al. A comprehensive repertoire of transfer RNA-derived fragments and their regulatory networks in colorectal cancer. J Comput Biol. 2020;27:1644–55. 10.1089/cmb.2019.0305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xiong W, Wang X, Cai X, et al. Identification of tRNA-derived fragments in colon cancer by comprehensive small RNA sequencing. Oncol Rep. 2019;42:735–44. 10.3892/or.2019.7178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Christodoulou S, Katsaraki K, Vassiliu P, et al. High intratumoral i-tRF-GlyGCC expression predicts short-term relapse and poor overall survival of colorectal cancer patients. Indep TNM Stage Biomed. 2023;11:1945. 10.3390/biomedicines11071945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fu M, Gu J, Wang M, et al. Emerging roles of tRNA-derived fragments in cancer. Mol Cancer. 2023;22:30. 10.1186/s12943-023-01739-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang S, Yu X, Xie Y, et al. tRNA derived fragments: a novel player in gene regulation and applications in cancer. Front Oncol. 2023;13:1–11. 10.3389/fonc.2023.1063930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu Y, Yang X, Jiang G, et al. 5′-tRF-GlyGCC: a tRNA-derived small RNA as a novel biomarker for colorectal cancer diagnosis. Genome Med. 2021;13:20. 10.1186/s13073-021-00833-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xu R, Du A, Deng X, et al. tsRNA-GlyGCC promotes colorectal cancer progression and 5-FU resistance by regulating SPIB. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2024;43:1–17. 10.1186/s13046-024-03132-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Laengle J, Stift J, Bilecz A, et al. DNA damage predicts prognosis and treatment response in colorectal liver metastases superior to immunogenic cell death and T cells. Theranostics. 2018;8:3198–213. 10.7150/thno.24699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McShane LM, Altman DG, Sauerbrei W, et al. Reporting recommendations for tumor marker prognostic studies (REMARK). Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2006;100:229–35. 10.1007/s10549-006-9242-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:228–47. 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bachmayr-Heyda A, Auer K, Sukhbaatar N, et al. Small RNAs and the competing endogenous RNA network in high grade serous ovarian cancer tumor spread. Oncotarget. 2016;7:39640–53. 10.18632/oncotarget.9243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gebert D, Hewel C, Rosenkranz D. unitas: the universal tool for annotation of small RNAs. BMC Genom. 2017;18:644. 10.1186/s12864-017-4031-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Loupakis F, Schirripa M, Caparello C, et al. Histopathologic evaluation of liver metastases from colorectal cancer in patients treated with FOLFOXIRI plus bevacizumab. Br J Cancer. 2013;108:2549–56. 10.1038/bjc.2013.245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stremitzer S, Stift J, Gruenberger B, et al. KRAS status and outcome of liver resection after neoadjuvant chemotherapy including bevacizumab. Br J Surg. 2012;99:1575–82. 10.1002/bjs.8909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.R Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. 2023.

- 30.Schemper M, Smith TL. A note on quantifying follow-up in studies of failure time. Control Clin Trials. 1996;17:343–6. 10.1016/0197-2456(96)00075-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc. 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tao E-W, Wang H-L, Cheng WY, et al. A specific tRNA half, 5’tiRNA-His-GTG, responds to hypoxia via the HIF1α/ANG axis and promotes colorectal cancer progression by regulating LATS2. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2021;40:67. 10.1186/s13046-021-01836-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Luan N, Chen Y, Li Q, et al. TRF-20-M0NK5Y93 suppresses the metastasis of colon cancer cells by impairing the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition through targeting claudin-1. Am J Transl Res. 2021;13:124–42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li S, Shi X, Chen M, et al. Angiogenin promotes colorectal cancer metastasis via tiRNA production. Int J cancer. 2019;145:1395–407. 10.1002/ijc.32245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lyons SM, Achorn C, Kedersha NL, et al. YB-1 regulates tiRNA-induced stress granule formation but not translational repression. Nucl Acid Res. 2016;44:6949–60. 10.1093/nar/gkw418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sahlolbei M, Fattahi F, Vafaei S, et al. Relationship between low expressions of tRNA-derived fragments with metastatic behavior of colorectal cancer. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2022;53:862–9. 10.1007/s12029-021-00773-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Han Y, Peng Y, Liu S, et al. tRF3008A suppresses the progression and metastasis of colorectal cancer by destabilizing FOXK1 in an AGO-dependent manner. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2022;41:32. 10.1186/s13046-021-02190-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lu S, Wei X, Tao L, et al. A novel tRNA-derived fragment tRF-3022b modulates cell apoptosis and M2 macrophage polarization via binding to cytokines in colorectal cancer. J Hematol Oncol. 2022;15:1–6. 10.1186/s13045-022-01388-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cao KY, Pan Y, Yan TM, et al. Antitumor activities of tRNA-derived fragments and tRNA halves from non-pathogenic Escherichia coli strains on colorectal cancer and their structure-activity relationship. mSystems. 2022;7:e0016422. 10.1128/msystems.00164-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All small RNA sequencing data generated in this study are publicly available in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) repository under accession number GSE293849. Anonymized data will be made available upon reasonable academic request. Protected health information (PHI) will not be disclosed. Investigators seeking access to the data must contact the corresponding author, provide proof of approval from their institution’s local institutional review board (IRB), and sign a non-disclosure agreement (NDA).