Abstract

Purpose:

To demonstrate a proof of concept for the measurement of myocardial oxygen extraction fraction (mOEF) by a cardiovascular magnetic resonance technique.

Methods:

The mOEF measurement was performed using an electrocardiogram-triggered double-echo asymmetric spin-echo sequence with EPI readout. Seven healthy volunteers (22–37 years old, 5 females) were recruited and underwent the same imaging scans at rest on 2 different days for reproducibility assessment. Another 5 subjects (23–37 years old, 4 females) underwent cardiovascular magnetic resonance studies at rest and during a handgrip isometric exercise with a 25% of maximal voluntary contraction. Both mOEF and myocardial blood volume values were obtained in septal regions from respective maps.

Results:

The reproducibility was excellent for the measurements of mOEF in septal myocardium (coefficient of variation: 3.37%) and moderate for myocardial blood volume (coefficient of variation: 19.7%). The average mOEF and myocardial blood volume of 7 subjects at rest were 0.61 ± 0.05 and 11.0 ± 4.3%, respectively. The mOEF agreed well with literature values that were measured by PET in healthy volunteers. In the exercise study, there was no significant change in mOEF (0.61 ± 0.06 vs 0.62 ± 0.07) or myocardial blood volume (12 ± 6% vs 13 ± 4%) from rest to exercise, as expected.

Conclusion:

The implemented cardiovascular magnetic resonance method shows potential for the quantitative assessment of mOEF in vivo. Future technical work is needed to improve image quality and to further validate mOEF measurements.

Keywords: cardiovascular magnetic resonance, contrast-free, handgrip exercise, myocardial blood volume, oxygen extraction fraction

1 |. INTRODUCTION

Imbalance of myocardial oxygen supply and demand precipitates a cascade of physiological changes resulting in ischemic pathology.1 For example, in patients with nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy, both oxygen metabolism and extraction are reduced significantly,2,3 whereas in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, they are relatively preserved or increased.4,5 In the presence of resting myocardial ischemia, myocytes reduce contractile function and therefore reduce metabolic need, to adapt to the reduced blood flow and oxygen supply. Measurements of oxygen extraction would provide direct assessment of the status of myocardial oxidative metabolism that have the potential to predict recovery of cardiac systolic function after restoration of blood flow and oxygen supply by coronary revascularization.6 It has been shown that cardiac metabolic changes precede ventricular mechanical dysfunction.7–9 Consequently, robust and accurate assessment of myocardial oxygen extraction would be highly desirable as a means of not only diagnosing myocardial oxygenation status, but also facilitating the development of therapies that aim to improve myocardial oxygen imbalance.

To date, the reference method for minimally invasive quantification of myocardial oxygen metabolism in vivo is PET with 11C-acetate and 15O-water. However, low spatial resolution, relatively long acquisition time (>30 minutes), limited availability, relatively high cost, and ionizing radiation discourage the widespread use of PET in practice. Cardiovascular MR (CMR) has shown promise in evaluating myocardial oxygenation using the “oxygenation-sensitive” imaging.10,11 Various applications using the oxygenation-sensitive method have shown its capability in detecting qualitative and/or semi-quantitative changes in myocardial oxygenation, with assistance from certain types of myocardial hyperemia.12–17 However, the contrast of oxygenation-sensitive imaging depends on the magnetic field strength, myocardial blood flow (MBV), and oxygen use. Therefore, data interpretation is sometimes difficult, and the oxygenation-sensitive method relies on cardiac stimulation (eg, vasodilator) to determine myocardial oxygenation status.

Previous studies demonstrated a T2-based model to measure myocardial oxygen extraction fraction (mOEF) during pharmacologically induced hyperemia.18,19 However, this method cannot measure mOEF at rest, and additional MBV data need to be incorporated within the model. To measure mOEF at any status, an extravascular model-based CMR method was developed and implemented. The purpose of this proof-of-concept study was to determine whether this new method can provide reasonable mOEF values in normal hearts, at rest and during a handgrip exercise.

2 |. METHODS

2.1 |. Theoretical consideration

The method for the quantification of mOEF was based on a theoretical extravascular model used to calculate tissue oxygenation with the magnetic susceptibility effect on deoxyhemoglobins.20 This susceptibility effect can be detected using an asymmetric spin-echo sequence (ASE), as described subsequently. It is noted that this model has no intravascular component, given relatively small amount of MBV (~10% or less) at rest.21 The effect of this intravascular component for the quantification of mOEF is addressed in more detail in Section 4. Because a similar method has already been described in detail in brain and skeletal muscle tissues,22–24 only a brief outline is provided here. This technique uses an electrocardiogram-triggered 2D ASE and EPI readout sequence with different pulse time offsets , while keeping an identical TE for each echo (Figure 1). Two echoes are acquired. The second echo is an asymmetric spin echo that occurs even if the pulse time offset is zero. In this way, double data points are obtained without increasing the scan time, with the potential to shorten breath-hold times during cardiac acquisition. It is noted that although the EPI readout may not be the best option at 3 T due to the relatively large inhomogeneity area around the myocardial lateral wall, this ASE sequence can still serve the proof-of-concept purpose by assessing myocardial segments without this inhomogeneity problem, such as the septal segment. It is likely that this inhomogeneity problem would be much less with this ASE sequence on a 1.5T system.

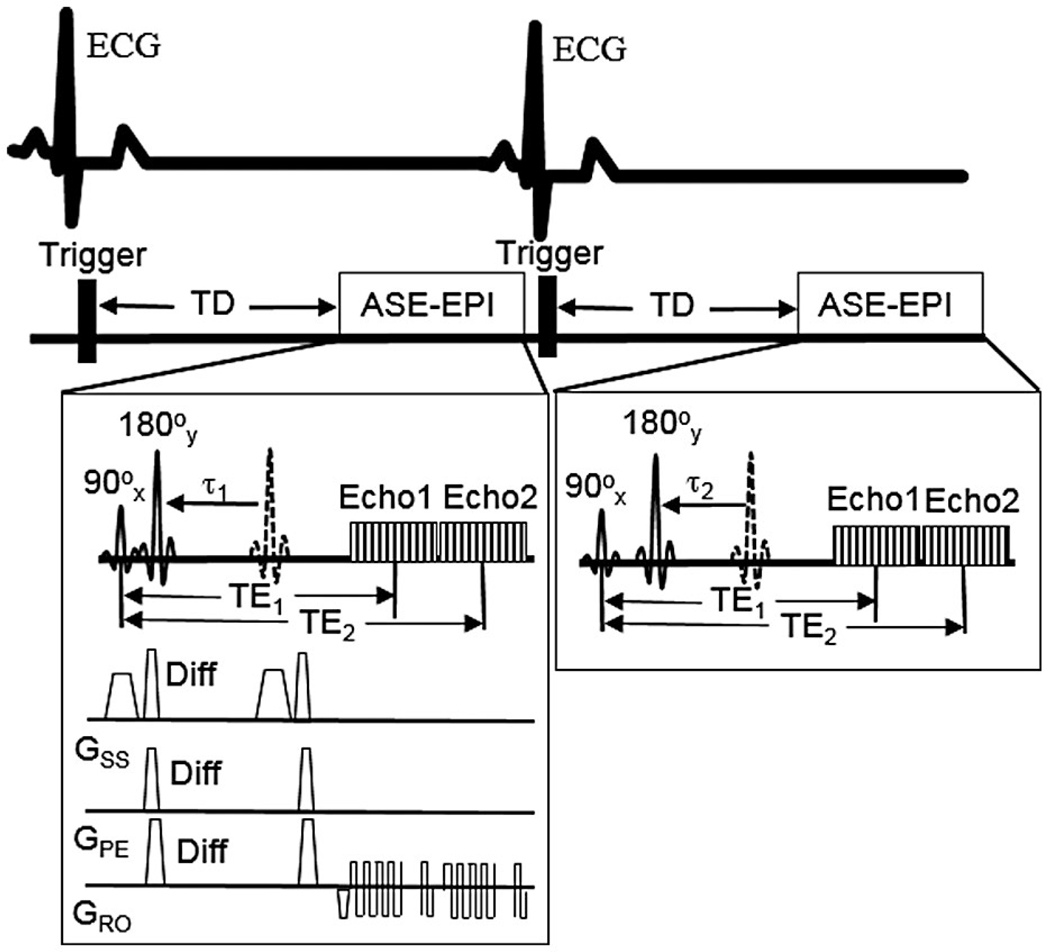

FIGURE 1.

Schematic display of the cardiac asymmetric spin-echo sequence with double-echo EPI (ASE-EPI) data acquisitions. The dotted 180° pulses are the refocusing pulses of the spin-echo sequences (time difference TE1/2 from 90° pulses). The diffusion gradients, “Diff,” are used to minimize ventricle blood signals. The trigger delay (TD) is to ensure that ASE-EPI data acquisition will occur in middiastole, to minimize cardiac motion. The two echoes and are constants, while the 180° pulse shift (eg, , ) varies with cardiac cycle. Abbreviation: ECG, electrocardiogram

The measured ASE signal can be expressed by two asymptotic forms, namely short time scale and long time scale, as follows:

| (1) |

and

| (2) |

where is the characteristic frequency shift induced by the presence of deoxyhemoglobin; for the first echo or for the second echo ; is the spin density; the subscripts s and l denote the short and long time scales, respectively; and is the critical time defined as tc = 1/(δω). It is noted that TE in Equations (1) and (2) is and for the first and second echo, respectively, and can be written as

| (3) |

where Hct is the fractional hematocrit; is the main magnetic field strength; and is the susceptibility difference between fully oxygenated and fully deoxygenated blood, which has been measured to be 0.18 ppm per unit Hct in centimeter–gram–second units.25 In this study, a constant Hct of 0.4 with a small to large vessel Hct ratio of 0.85 was used for all subjects.26

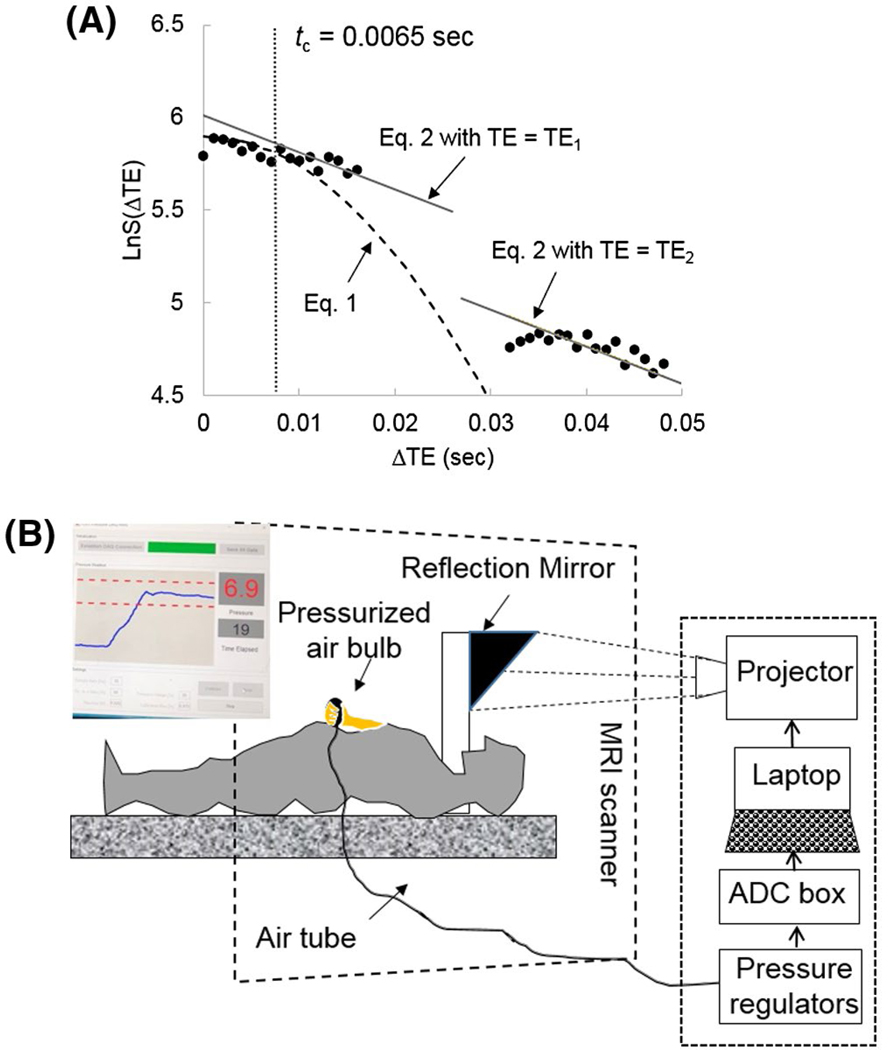

Figure 2A shows one example of curve fitting to Equations (1–3), using data from 1 healthy volunteer. The left side and right side of data points were acquired by the first and second echoes, respectively. The special transverse relaxation rate and are both estimated by fitting the logarithm of with (ie, ) using the double-echo ASE data. The MBV can be calculated as , following the estimation of and . After both and MBV are estimated, measurement of mOEF can be obtained from Equation (3).

FIGURE 2.

A, Examples of curve-fitting processes in the plot of Ln(S) versus time to obtain oxygen extraction fraction (OEF) and myocardial blood flow (MBV). In this case, the critical time is 0.0065 seconds (outlined by the gray vertical line). Equations (1) and (2) in the main text were used to fit to the points at time and time , respectively. The and can be obtained through the regression fitting of Equation (2) (gray lines). B, Illustration of the handgrip exercise within the MR bore. The photo insert shows what the subject viewed inside the scanner. The Blue curve shows the exercise level from baseline to the prescribed exercise strength, and the two red dotted lines indicate the tolerance range during the exercise (usually 10% of baseline strength)

2.2 |. Cardiovascular MRI protocol

In this ASE-CMR sequence, there were 17 varying 180° pulse shifts , and the increment of was 0.5 ms. Other imaging parameters were , TR = one R-R interval; FOV = 220 × 220 mm2, matrix size = 64 × 64 interpolated to 128 × 128, data acquisition window = 110 ms within each R-R interval, slice thickness = 8 mm, one midventricle slice, and total acquisition = 17 R-R intervals. The trigger delay in Figure 1 is adjusted automatically by the MRI system to ensure the data acquisition occurs in middiastole. To minimize ventricular blood (dark blood) and intravascular blood signals, a pair of weak diffusion gradients was added on both sides of the refocusing 180° pulse in three directions.27 The empirical b value from all of these gradients was found to be 5.65 s/mm2.

In addition to mOEF measurements, coronary artery flow measurements were performed in 5 subjects who performed the exercise study (see subsequently), with an established 2D phase-contrast flow velocity–encoded gradient-echo sequence available in the MRI system.28–30 A double-oblique 3D T2prep segmented gradient-echo sequence was first used to localize the right coronary artery. One slice was then prescribed at the proximal to middle segment of the right coronary artery with the slice orientation perpendicular to the artery. The single-slice 2D flow quantification sequence was performed on this slice with the following parameters: , flip angle = 20°, FOV = 259 × 194 mm2, matrix size = 384 × 260 (interpolated), true spatial resolution = 1.35 × 1.49 mm2, slice thickness = 6 mm, flow encoding in slice direction, velocity encoding = 35 cm/s, and retrospective electrocardiogram gating with 30 frames per R-R interval. The flow measurements were performed at rest and during a handgrip exercise, with a breath-hold time about 16–20 seconds for each scan.

2.3 |. Participants and handgrip exercise

Seven healthy participants (age = 27 ± 5 years, 5 females) were recruited to perform the repeatability study at rest on day 1 and day 2, separated by 7 days. Our local Washington University institutional review board approved the study, and written consent was received from each participant. All MRI studies were carried out in a 3T clinical whole-body MRI system (Magnetom Prisma; Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany) and a phased-array body coil was used.

Another 5 participants (age = 28 ± 6 years, 4 females) underwent the MRI study at rest and during an isometric hand grip exercise. The hand grip device was a custom-made bulb pressurized by air, as shown in Figure 2B. When the subject squeezed the bulb, the force was digitized and displayed on a screen. The subject was able to visualize the screen through a reflective mirror within the MRI bore, so that a constant pressure level was maintained consistently throughout the exercise. In this study, 25% of maximal voluntary contraction was prescribed. The subject was instructed to do the exercise for 4 minutes and the MRI scan started 2 minutes after the start of the exercise when the increased heart rate reached a plateau. The mOEF scan was performed during a breath-hold, and the trigger delay was adjusted based on the exercise heart rate before the scan. The blood pressure and the heart rate were monitored throughout the imaging session using an MR-compatible physiology monitor (Invivo, Gainesville, Florida). Rate-pressure product (RPP) was then calculated by multiplying the heart rate and the systolic blood pressure.

2.4 |. Image and data analysis

The coronary artery flow images were analyzed using commercial software Medis (Medis Medical Imaging Systems, Leiden, Netherlands) by 1 reviewer. The validation and application of this software for flow quantification have been well documented in the literature.31–34 Briefly speaking, a small circular region of interest (ROI) was drawn on the cross section of the coronary artery, and the ROI position was corrected manually at different cardiac phases. To remove any residual background motion, such as through-plane motion, another small reference ROI was drawn on the myocardium adjacent to the coronary artery of interest. The coronary flow velocity was corrected by subtracting the velocity in the reference ROI. Because the phasic flow is approximately equal in systole and diastole in the right coronary artery35 and motion artifacts are minimal in middiastole, the diastolic peak blood flow velocity was selected to represent the change in the coronary artery flow from rest to exercise. The source images of mOEF measurements were first retrospectively corrected for both cardiac and respiratory motion offline36 and then denoised using an in-house denoising software program based on the Block-matching and 3D filtering approach with a window size of 10.37 These images were then used to calculate mOEF and MBV maps using another in-house software written in MATLAB (R2019a version; The MathWorks, Natick, MA).

Because EPI readout is sensitive to the off-resonance effect and background inhomogeneity, particularly in the lateral myocardial regions (Supporting Information Figure S1), the mOEF measurement was made in the septum, which is much less prone to these adverse effects. Two reviewers (L.L. and Z.J.) performed blinded ROI measurements of mOEF and MBV independently. One reviewer (Z.J.) performed these measurements twice on different days, to assess intra-observer variability. An ROI was first drawn on the first magnitude image of the mOEF source sets and then copied to maps to obtain averaged mOEF and MBV values. The ROI covered the entire septal segment between two right-ventricle insertions. For better illustration of mOEF and MBV maps, a mask was first created by manually drawing endo-contours and epi-contours in the first source image. The left-ventricle wall areas defined by the mask on both mOEF and MBV maps were then overlaid on this source image to create color maps.

The mean mOEF and MBV values of 2 reviewers were used as the respective final values. The intra-reviewer and inter-reviewer variability was assessed by the interclass correlation for all data points. The repeatability of mOEF and MBV was determined using the coefficient of variation. The differences in mOEF and MBV between the rest and the exercise values were assessed using a paired Student’s t-test with both sides. All statistical analyses were performed with MedCalc Statistics for Biomedical Research (MedCalc Software, Mariakerke, Belgium). A P value < .05 was considered statistically significant.

3 |. RESULTS

3.1 |. Repeatability study

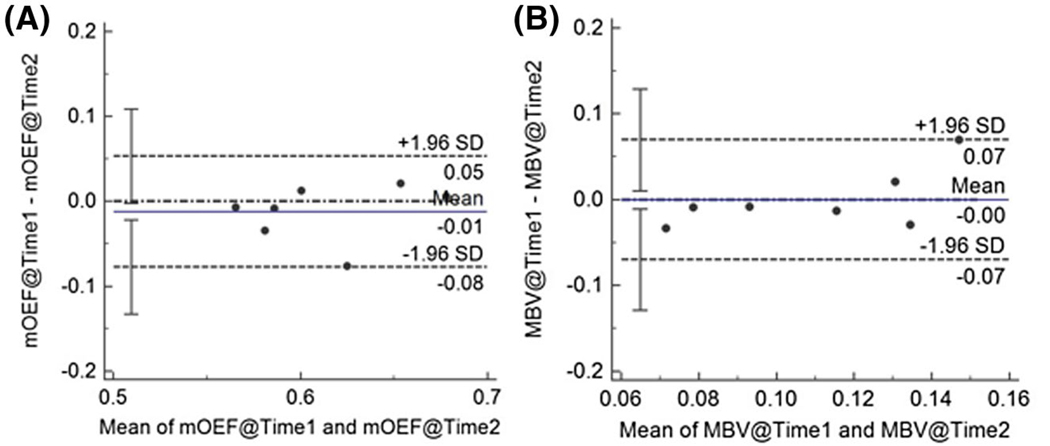

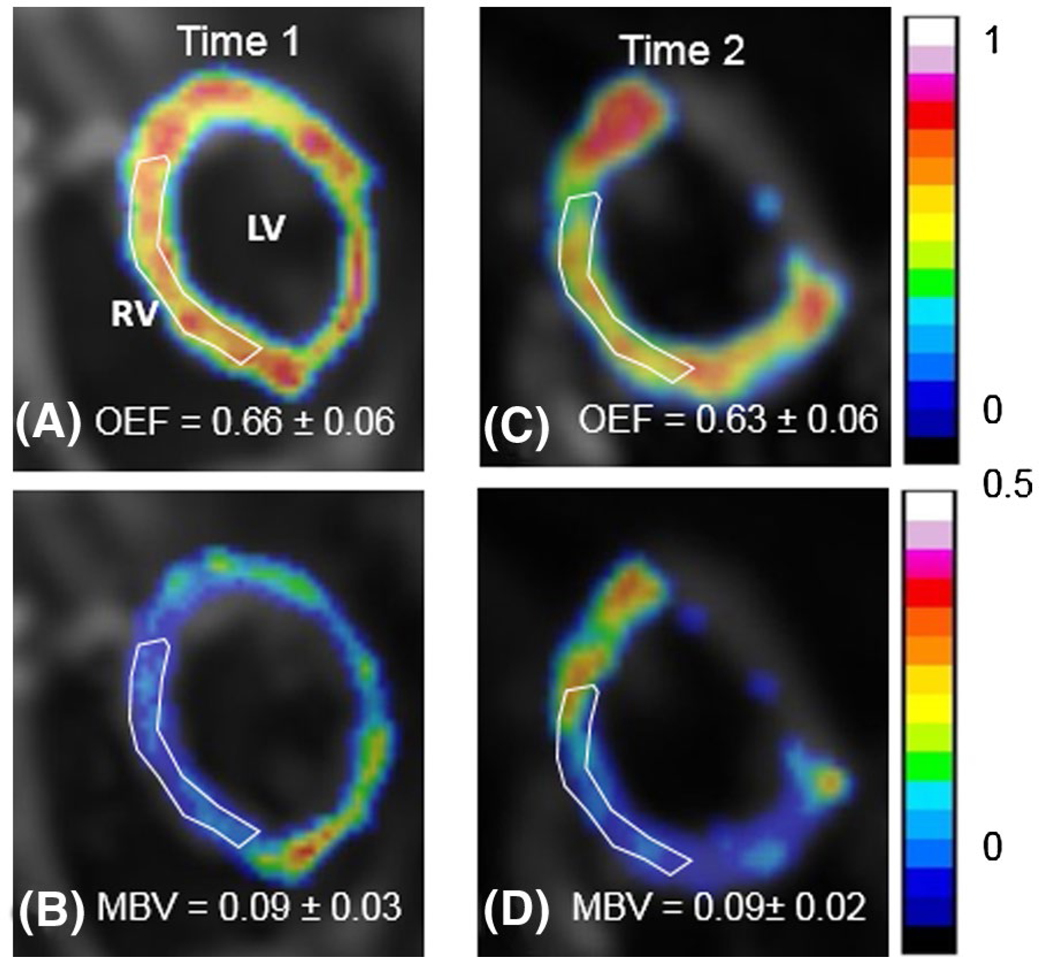

The inter-reviewer agreement for the measurements of mOEF and MBV were both strong (intraclass correlation coefficient: mOEF = 0.87, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.70~0.94; MBV = 0.94, 95% CI: 0.87~0.98). The intra-reviewer agreement was also good (mOEF = 0.94, 95% CI: 0.82~0.98; MBV = 0.87, 95% CI: 0.64~0.96). The Bland-Altman plots of the mOEF and MBV measurements at two time points are shown in Figure 3. The coefficient of variation values for OEF and MBV are 3.37% (CI: 0%, 6.3%) and 19.7% (CI: 0%, 29%), respectively. The averaged mOEF and MBV at time 1 are 0.61 ± 0.05 and 11.0 ± 4.3%, respectively. Representative mOEF and MBV maps at two different time points from 1 participant are shown in Figure 4.

FIGURE 3.

Bland-Altman plots for the cardiovascular MR (CMR)–measured resting mOEF (A) and MBV (B) at two time points (time 1 and time 2). Both are expressed without units

FIGURE 4.

Sample myocardial OEF and MBV maps from 1 participant at time 1 (A,B) and time 2 (C,D). The maps are overlaid on anatomic images. The white region-of-interest regions indicate the septal areas to obtain respective mean values

3.2 |. Exercise study

Table 1 lists the mean values of the hemodynamic parameters, mOEF, MBV, and peak diastole blood flow velocity, at rest and during the 25% maximal voluntary contraction handgrip exercise. Because RPP is an indicator of overall myocardial oxygen consumption, according to Fick’s law, the similar change between RPP (30%) and peak diastolic blood flow velocity (35.7%) suggests that mOEF is likely to remain at similar levels at both rest and exercise.38–40 This observation in flow velocity is consistent with what has been previously reported (ie, 44.3 ± 8.3% increase with 30% maximal voluntary contraction).41

TABLE 1.

Hemodynamic parameters, CMR-measured septal mOEF, and septal MBV

| Rest | Handgrip | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| HR (bpm) | 68 ± 5 | 81 ± 11 | <.01 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 114 ± 4 | 126 ± 5 | .01 |

| Rate-pressure product (bpm · mmHg) | 7780 ± 648 | 10 268 ± 1590 | <.01 |

| Peak diastolic blood velocity (cm/s) | 24.3 ± 2.6 | 32.9 ± 2.9 | <.001 |

| mOEF | 0.61 ± 0.06 | 0.62 ± 0.07 | NS |

| MBV | 0.12 ± 0.06 | 0.13 ± 0.04 | NS |

|

| |||

Abbreviations: HR, heart rate; NS, no significance.

4 |. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

This work shows the potential of a quantification method to measure mOEF at any status. Although the clinical utility of mOEF remains to be defined, a few studies report potential changes in the mOEF at rest in subjects with hibernating myocardium42 and dilated cardiomyopathy,2 or in the mOEF during inotropic stress in patients with coronary artery disease.1 The purpose of this study was to explore whether a new CMR method can provide reproducible mOEF values at rest, as well as reasonable mOEF values during a handgrip stress, by comparing them with corresponding literature values. Excellent repeatability of the mOEF measurement at rest was achieved in the septum of healthy subjects. The calculated mOEF at rest was in close agreement with the mOEF values reported in the literature, measured by PET in the septum.2,43,44 The moderate isometric handgrip exercise induced nonsignificant increase in mOEF in healthy subjects, which is expected when significant increases in RPP and peak coronary artery flow velocity during the exercise were observed.

The model used in this method considers only the extravascular contribution to the MRI contrast. Given the small blood volume in the cardiac muscle, the oxygen-sensitive MR contrast obtained is predominately from the extravascular compartment. The added diffusion gradients in the ASE sequence further diminished most intravascular signals. To approximately estimate the effect of the intravascular contribution, a T2-based model reported previously in hearts was used for a simulation, in which both intravascular and extravascular components were involved.18 Assuming mOEF of 0.7 and MBV of 10%, it was found that for a true decrease of 30% in mOEF (ie, 0.49), the estimated mOEF would be 0.51 (an error of only 4%) if the intravascular contribution is ignored. Therefore, at resting conditions, or when using adenosine, dipyridamole, or mild to moderate isometric exercise when mOEF decreases, the described extravascular model appears to be a valid method of estimating the mOEF values. Because the previous T2 model can only estimate mOEF during stress,18 the current new method would be preferable for its capability to estimate mOEF at any status (rest or stress).

The current reference method for the noninvasive measurement of mOEF is the PET approach with the inhalation of [15O] O2 gas. Literature has shown considerable variation in the septal mOEF of healthy subjects at rest, from 0.64 ± 0.142 to 0.71 ± 0.18.43 In a group of 13 men with ages (mean age, 29 years) similar to those in our study population (mean age, 27 years), mOEF was approximately 0.64 ± 0.12.42 Our mean mOEF of 0.61 was slightly lower, but still within the range of measurement errors.

Strictly speaking, MBV measured with the mOEF method refers to the venous blood volume with deoxyhemoglobin. Because diffusion gradients were used to crush intravascular signals in relatively large blood vessels and 90% of microvasculature in the heart is composed of small capillary vessels,45 the measured MBV is likely to represent transmural capillary and venule blood volume. Our mean MBV (11 ± 4.3%) agrees well with the blood volume value of approximately 13.8 ± 3.3% measured by PET39 and 12.3 ± 4.5% measured by contrast echocardiography in healthy subjects.46

There are several limitations to the current study. First, distortion and signal loss were observed in the lateral wall due to the relatively strong field inhomogeneity, which reduces signal intensity progressively with the increased ΔTE (Supporting Information Figure S1). Thus, the current version of the mOEF sequence with the EPI readout is unsuitable for the detection of myocardial ischemia in the lateral wall. Future technical developments of the ASE sequence and/or background field inhomogeneity correction is necessary for robust imaging of mOEF of the heart in its entirety. Second, the data acquisition window is relatively long and uses a single-shot acquisition scheme (approximately 110 ms), which makes the sequence susceptible to cardiac motion. The inhomogeneity observed in the mOEF and MBV maps in Figure 4 may be partially induced by this motion artifact, in addition to intravoxel dephasing. Segmented data acquisition or a different readout scheme would be options that could reduce this motion error. Third, a breath-hold time of 17 R-R intervals is still relatively long and may not be feasible for some patients. A free-breathing approach, based either on a navigator echo or using a retrospective motion correction scheme, is currently under investigation. Fourth, a single slice was acquired in this pilot study. To cover more areas in the left ventricle, multiple 2D slices can be acquired with multiple breath-holding or under free breathing. The latter approach is currently investigated in clinical patients with much success so far, which will be reported in different manuscripts. Finally, the proposed mOEF technique needs rigorous validation against the reference methods in vivo, such as in animal studies.19,47

In conclusion, we have demonstrated a proof of concept of a CMR approach to quantitatively assess mOEF with an extravascular model. The excellent repeatability of the mOEF measurements in the same regions indicates its potential for consecutive monitoring of mOEF progression under various pathophysiological conditions. Nevertheless, substantial technical development, rigorous validation, and case-control study are warranted before its clinical application.

Supplementary Material

FIGURE S1 The myocardial oxygen extraction fraction (mOEF) source images from the subject in Figure 4 at time 1. All 34 images are shown for both and . The images are displayed in the order of images acquired in an interleaved fashion. The value at the bottom of each image is the , a time decay for . The signal loss, shown in the lateral myocardial segment (arrows), is mostly seen in the second echo due to the strong effect. Abbreviations: LV, left ventricle; RV, right ventricle

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional Supporting Information may be found online in the Supporting Information section.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank Samika Kikkeri for helping with the construction of the handgrip device throughout the study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Janier MF, André-Fouet X, Landais P, et al. Perfusion-MVO2 mismatch during inotropic stress in CAD patients with normal contractile function. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:H59–H67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agostini D, Iida H, Takahashi A, Tamura Y, Henry Amar M, Ono Y. Regional myocardial metabolic rate of oxygen measured by O2–15 inhalation and positron emission tomography in patients with cardiomyopathy. Clin Nucl Med. 2001;26:41–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bell SP, Adkisson DW, Ooi H, Sawyer DB, Lawson MA, Kronenberg MW. Impairment of subendocardial perfusion reserve and oxidative metabolism in nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy. J Card Fail. 2013;19:802–810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Timmer SA, Germans T, Götte MJ, et al. Determinants of myocardial energetics and efficiency in symptomatic hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2010;37:779–788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Güçlü A, Knaapen P, Harms HJ, et al. Disease stage-dependent changes in cardiac contractile performance and oxygen utilization underlie reduced myocardial efficiency in human inherited hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2017;10:e005604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abraham A, Nichol G, Williams KA, et al. 18F-FDG PET imaging of myocardial viability in an experienced center with access to 18F-FDG and integration with clinical management teams: the Ottawa-FIVE substudy of the PARR 2 trial. J Nucl Med. 2010;51:567–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tadamura E, Tamaki N, Matsumori A, et al. Myocardial metabolic changes in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Nucl Med. 1996;37:572–577. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hernandez AM, Huber JS, Murphy ST, et al. Longitudinal evaluation of left ventricular substrate metabolism, perfusion, and dysfunction in the spontaneously hypertensive rat model of hypertrophy using small-animal PET/CT imaging. J Nucl Med. 2013;54:1938–1945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li J, Kemp BA, Howell NL, et al. Metabolic changes in spontaneously hypertensive rat hearts precede cardiac dysfunction and left ventricular hypertrophy. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8:e010926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vöhringer M, Flewitt JA, Green JD, et al. Oxygenation-sensitive CMR for assessing vasodilator-induced changes of myocardial oxygenation. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2010;12:20–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Friedrich MG, Karamitsos TD. Oxygenation-sensitive cardiovascular magnetic resonance. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2013;15:43–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Foltz WD, Huang H, Fort S, Wright GA. Vasodilator response assessment in porcine myocardium with magnetic resonance relaxometry. Circulation. 2002;106:2714–2719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dharmakumar R, Arumana JM, Tang R, Harris K, Zhang Z, Li D. Assessment of regional myocardial oxygenation changes in the presence of coronary artery stenosis with balanced SSFP imaging at 3.0 T: theory and experimental evaluation in canines. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2008;27:1037–1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fischer K, Yamaji K, Luescher S, et al. Feasibility of cardiovascular magnetic resonance to detect oxygenation deficits in patients with multi-vessel coronary artery disease triggered by breathing maneuvers. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2018;20:31–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grover S, Lloyd R, Perry R, et al. Assessment of myocardial oxygenation, strain, and diastology in MYBPC3-related hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a cardiovascular magnetic resonance and echocardiography study. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2019;20:932–938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dass S, Holloway CJ, Cochlin LE, et al. No evidence of myocardial oxygen deprivation in nonischemic heart failure. Circ Heart Fail. 2015;8:1088–1093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levelt E, Rodgers CT, Clarke WT, et al. Cardiac energetics, oxygenation, and perfusion during increased workload in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Eur Heart J. 2016;37:3461–3469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zheng J, Wang JH, Nolte M, Li D, Gropler RJ, Woodard PK. Dynamic estimation of myocardial oxygen extraction ratio during dipyridamole stress by MRI: a preliminary study in canines. Magn Reson Med. 2004;51:718–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McCommis KS, Goldstein TA, Abendschein DR, et al. Quantification of regional myocardial oxygenation by magnetic resonance imaging: validation with positron emission tomography. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2009;3:41–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yablonskiy DA, Haacke EM. Theory of NMR signal behavior in magnetically inhomogeneous tissues: the static dephasing regime. Magn Reson Med. 1994;32:749–763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaul S, Jayaweera AR. Coronary and myocardial blood volumes: noninvasive tools to assess the coronary microcirculation? Circulation. 1997;96:719–724. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.An H, Lin W. Impact of intravascular signal on quantitative measures of cerebral oxygen extraction and blood volume under normo- and hypercapnic conditions using an asymmetric spin echo approach. Magn Reson Med. 2003;50:708–716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.An H, Liu Q, Chen Y, Lin W. Evaluation of MR-derived cerebral oxygen metabolic index in experimental hyperoxic hypercapnia, hypoxia, and ischemia. Stroke. 2009;40:2165–2172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zheng J, An H, Coggan AR, et al. Noncontrast skeletal muscle oximetry. Magn Reson Med. 2014;71:318–325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weisskoff RM, Kiihne S. MRI susceptometry: image-based measurement of absolute susceptibility of MR contrast agents and human blood. Magn Reson Med. 1992;24:375–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eichling JO, Raichle ME, Grubb RL Jr, Larson KB, Ter-Pogossian MM. In vivo determination of cerebral blood volume with radioactive oxygen-15 in the monkey. Circ Res. 1975;37:707–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McCommis KS, Koktzoglou I, Zhang HS, et al. Improvement of hyperemic myocardial oxygen extraction fraction estimation by a diffusion prepared sequence. Magn Reson Med. 2010;63:1675–1682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bedaux WL, Hofman MB, de Cock CC, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging versus Doppler guide wire in the assessment of coronary flow reserve in patients with coronary artery disease. Coron Artery Dis. 2002;13:365–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Machida H, Komori Y, Ueno E, et al. Accurate measurement of pulsatile flow velocity in a small tube phantom: comparison of phase-contrast cine magnetic resonance imaging and intraluminal Doppler guidewire. Jpn J Radiol. 2010;28:571–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Deng Z, Fan Z, Lee SE, et al. Noninvasive measurement of pressure gradient across a coronary stenosis using phase contrast (PC)-MRI: a feasibility study. Magn Reson Med. 2017;77:529–537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Langerak SE, Kunz P, Vliegen HW, et al. MR flow mapping in coronary artery bypass grafts: a validation study with Doppler flow measurements. Radiology. 2002;222:127–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Salm LP, Schuijf JD, Lamb HJ, et al. Validation of a high-resolution, phase contrast cardiovascular magnetic resonance sequence for evaluation of flow in coronary artery bypass grafts. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2007;9:557–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van Wolferen SA, Marcus JT, Westerhof N, et al. Right coronary artery flow impairment in patients with pulmonary hypertension. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:120–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hays AG, Hirsch GA, Kelle S, Gerstenblith G, Weiss RG, Stuber M. Noninvasive visualization of coronary artery endothelial function in healthy subjects and in patients with coronary artery disease. JACC. 2010;56:1657–1665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Davies JE, Whinnett ZI, Francis DP, et al. Evidence of a dominant backward-propagating “suction” wave responsible for diastolic coronary filling in humans, attenuated in left ventricular hypertrophy. Circulation. 2006;113:1768–1778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xue H, Shah S, Greiser A, et al. Motion correction for myocardial T1 mapping using image registration with synthetic image estimation. Magn Reson Med. 2012;67:1644–1655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Danielyan A, Katkovnik V, Egiazarian K. BM3D frames and variational image deblurring. IEEE Trans Image Process. 2012;21: 1715–1728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Katori R, Miyazawa K, Ikeda S, Shirato K, Muracuchi I, Hayashi T. Coronary blood flow and lactate metabolism during isometric handgrip exercise in heart disease. Jpn Heart J. 1976;17:742–752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Khan IA, Otero FJ, Font-Cordoba J, et al. Adjunctive handgrip during dobutamine stress echocardiography: invasive assessment of myocardial oxygen consumption in humans. Clin Cardiol. 2005;28:349–352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kaijser L, Berglund B. Coronary hemodynamics during isometric handgrip and atrial pacing in patients with angina pectoris compared to healthy men. Cardioscience. 1993;4:99–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hays AG, Stuber M, Hirsch GA, et al. Non-invasive detection of coronary endothelial response to sequential handgrip exercise in coronary artery disease patients and healthy adults. PLoS One. 2013;8:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Grund F, Treiman C, Ilebekk A. How to discriminate between hibernating and stunned myocardium. J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino). 2006;47:323–328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Heinonen I, Kudomi N, Kemppainen J, et al. Myocardial blood flow and its transit time, oxygen utilization, and efficiency of highly endurance-trained human heart. Basic Res Cardiol. 2014;109:413–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kudomi N, Kalliokoski KK, Oikonen VJ, et al. Myocardial blood flow and metabolic rate of oxygen measurement in the right and left ventricles at rest and during exercise using 15O-labeled compounds and PET. Front Physiol. 2019;10:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kaul S, Jayaweera AR. Coronary and myocardial blood volumes: noninvasive tools to assess the coronary microcirculation? Circulation. 1997;96:719–724. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vogel R, Indermühle A, Reinhardt J, et al. The quantification of absolute myocardial perfusion in humans by contrast echocardiography: algorithm and validation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45: 754–762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zheng J, Wang JH, Rowold FE, Gropler RJ, Woodard PK. Relationship of apparent myocardial T2 and oxygenation: towards quantification of myocardial oxygen extraction fraction. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2004;20:233–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

FIGURE S1 The myocardial oxygen extraction fraction (mOEF) source images from the subject in Figure 4 at time 1. All 34 images are shown for both and . The images are displayed in the order of images acquired in an interleaved fashion. The value at the bottom of each image is the , a time decay for . The signal loss, shown in the lateral myocardial segment (arrows), is mostly seen in the second echo due to the strong effect. Abbreviations: LV, left ventricle; RV, right ventricle