Abstract

Introduction

Botulinum toxin injections into the salivary glands inhibit saliva production by reducing the release of acetylcholine at the parasympathetic nerve terminals within the salivary gland. The phase 3 study reported here assessed the safety, tolerability, and effectiveness of repeated cycles of rimabotulinumtoxinB (RIMA) injections in adults with troublesome sialorrhea.

Methods

In this phase 3, open-label multicenter study, 187 adult participants with troublesome sialorrhea due to Parkinson disease (65.8%), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (13.9%), and other etiologies (20.3%) received up to 4 cycles of RIMA treatment (3500 U every 11–15 weeks).

Results

Participants (69% male, 31% female; mean age 64.1 years) had sialorrhea for a mean of 3.2 years at baseline with a mean Unstimulated Salivary Flow Rate (USFR) of 0.63 ± 0.49 g/min. During the first treatment cycle, RIMA significantly reduced the mean±standard deviation (SD) USFR from baseline to week 4 by – 0.34 ± 0.37 g/min (p < 0.0001), and efficacy was maintained through week 13 (– 0.14 ± 0.29 g/min; p < 0.0001). Reductions were maintained at subsequent injection cycles 2–4, with mean absolute USFRs at weeks 4 and 13 of each cycle similar to those of cycle 1. Most adverse events (AEs) were mild, and the most commonly reported AEs in each cycle that were considered to be treatment-related were dry mouth (≤ 15.5% participants/cycle) and dental caries (≤ 6.0% participants/cycle).

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that RIMA 3500 U safely reduces saliva production over repeated treatment cycles through 1 year, thereby supporting its utility in the management of troublesome sialorrhea in adults.

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40120-025-00777-z.

Keywords: Botulinum toxin type B, Sialorrhea, Drooling, RimabotulinumtoxinB, Parkinson’s disease, Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

Key Summary Points

| Why carry out this study? |

| This study was performed to assess the safety, tolerability, and duration of therapeutic responses of repeated rimabotulinimtoxinB (RIMA) injections in adults with troublesome sialorrhea as required for US regulatory approval |

| What was learned from the study? |

| Repeated treatment with RIMA for sialorrhea was safe and well-tolerated through 1 year of treatment |

| Treatment with RIMA was consistently effective at reducing unstimulated salivary flow rate over repeated treatment cycles |

| Although the effects of RIMA were observed to wear off, most clinical measures were maintained significantly below pre-treatment baseline values across treatment cycles (mean injection interval 13.4 weeks) |

Introduction

Sialorrhea, defined as an excess spillage of saliva from the mouth, affects up to 74% of people with Parkinson disease (PD) [1] and is rated as one of the most bothersome non-motor symptoms of the disease [2]. Sialorrhea is also common in individuals with other neurological diseases, including amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) [3]. It is often seen as a side effect of radiation therapy in patients with head and neck cancers [4] and in patients taking certain antipsychotic medications (e.g., clozapine) [5]. Persistent sialorrhea often causes perioral irritation, oral hygiene problems, soiled clothing, speech difficulties, and sleep interruption; in some cases, pooling of saliva at the back of the throat can lead to chronic cough and aspiration pneumonia [6, 7]. Moreover, the embarrassment and social stigma associated with sialorrhea may lead to social withdrawal and isolation [8].

Botulinum toxin (BoNT) has been used to reduce saliva production in clinical practice since the early 2000s [9], with studies showing the safety and efficacy of BoNT type A (BoNT-A) and BoNT type B (BoNT-B) serotypes in patients with neurologic disorders [9–15]. Of the available BoNT formulations, only incobotulinumtoxinA (Xeomin®) [11, 15, 16] and rimabotulinumtoxinB (RIMA; Myobloc®) [13, 17] have received US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval for the management of sialorrhea. BoNT injections into the salivary glands provide long-lasting inhibition of saliva production by cleaving proteins that allow for the docking and release of vesicles containing acetylcholine at the parasympathetic (neurosecretory) nerve terminals within the salivary glands [18]. Since acetylcholine triggers the release of saliva, a reduction in acetylcholine will also reduce saliva production. BoNT-A and BoNT-B serotypes are antigenically distinct and differ in their site of action, cleaving different proteins within the docking apparatus [19]. Based on the greater propensity for BoNT-B to cause dry mouth, as observed in cervical dystonia studies, it was surmised that BoNT-B may have greater effects on autonomic nerve terminals than BoNT-A, resulting in RIMA being studied for the treatment of sialorrhea.

The approval of RIMA for sialorrhea by the US FDA is supported by safety and efficacy data from three clinical studies: a phase 2 double-blind study showing dose-dependent decreases in sialorrhea in individuals with PD [14]; a phase 3 (pivotal), randomized, double-blind study demonstrating that single injections of RIMA at doses of 2500 U or 3500 U significantly reduced unstimulated salivary flow rates (USFRs) as early as week 1 [13]; and the phase 3 , open-label, repeated dose, outpatient study reported here that assessed the safety, tolerability, and duration of therapeutic responses of repeated RIMA injections in adults with troublesome sialorrhea over a period of 1 year.

Methods

Study Conduct

This was a phase 3, multicenter, open-label, outpatient study with the aim to evaluate the safety and effectiveness of repeated treatment with RIMA (3500 U) in the management of adult sialorrhea over 1 year. The study was conducted from October 2015 to June 2017 at 37 sites located in the USA (21 sites), Ukraine (9 sites), and Belarus (7 sites). The study was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02610868).

Ethical Approval

Institutional review boards at the participating sites approved the protocol, and the trial was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the International Conference on Harmonization Good Clinical Practice Guidelines. All participants provided written informed consent.

Study Population

Inclusion criteria were similar to those used in a previous study of RIMA [13]. In brief, adults (aged 18–85 years) with troublesome sialorrhea (of any etiology) for at least 3 months were eligible for inclusion in this open-label study if they were judged able to participate in the study for up to 1 year (or 6 months for patients with ALS). Participants had to have a minimum USFR [20] of 0.2 g/min (process described in Assessments section) and a minimum Drooling Frequency and Severity Scale-Investigator (DSFS-I) score of 4 (indicating constant drooling) [21]. Participants who had previously received an injection of any BoNT into the salivary glands within the past 24 weeks were excluded; treatment with BoNT at other anatomic sites was allowed with a minimum treatment interval of 12 weeks and provided no adverse events (AEs) were reported. Participants with a moderate to high risk of aspiration were excluded except for patients with ALS whose aspiration risk was satisfactorily controlled by placement of a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube or G-tube for nutritional support (investigator judgement). Participants with known sensitivity to BoNT or any of the RIMA solution components, prior salivary gland surgery, a respiratory forced vital capacity of < 20% predicted value, and any clinically significant disease that could impact participation in the study were also excluded. Concomitant use of medications that affect neuromuscular function was prohibited, as was warfarin (to decrease potential for bruising). Oral/transdermal pharmacologic treatments for sialorrhea had to be discontinued at least 30 days prior to baseline injection; however, participants with ALS were permitted to take short-acting (< 8 h) medications to treat sialorrhea provided doses had been stable for ≥ 2 weeks prior to screening and the participants did not use these agents within 8 h of study visits.

Study Design

After a screening visit, participants received a total RIMA dose of 3500 U (0.7 mL volume), injected into the submandibular (250 U each) and parotid (1500 U each) glands on day 1. Injections were guided by external anatomical landmarks alone or by external anatomical landmarks using an ultrasound-guided technique. Injections were administered using four 1.0-mL insulin syringes (1 for each gland), using 0.5-inch, 30-gauge needles. The submandibular glands were landmarked a finger breadth medial to the middle of the body of the mandible, which was located by bisecting the distance between the tip of the chin, to the angle of the mandible. Injection was administered from an anterior to posterior direction at a depth of 0.5 to 1.0 cm. The parotid glands were landmarked by bisecting the distance between the tip of the tragus and the angle of the mandible. Injections were angled toward the anterior border of the masseter at a depth of 0.5 to 1.0 cm. Before delivering each injection, the plunger of the syringe was retracted slightly to ensure the needle was not in a vascular structure.

Participants were contacted by telephone within 24 h after the initial injection to check their health status and remind them to complete their patient diary (described in Assessments section). The planned duration of participation for each participant was a maximum of four treatment cycles (52 weeks), excluding the screening period, which could have lasted up to 21 days. Re-injection occurred when the participant returned to baseline status, with a minimum interval of 11 weeks from the prior injection but no later than 15 weeks (13 ± 2 weeks). Investigators had the discretion to decrease RIMA doses to a minimum of 2500 U for tolerability.

Assessments

Safety assessments included treatment-emergent AEs, AEs of special interest (AESIs), vital signs, weight, and safety laboratory tests. AESIs for the study were predefined as AEs that could represent airway compromise and included aspiration, aspiration pneumonia, choking, and dysphagia. Participants underwent scheduled dental examinations by an independent dentist at screening and at weeks 4 and 13 of cycle 1, and also at weeks 26 and 52 or study discontinuation (as applicable). Additionally, an oral exam was performed at each study visit when a dental exam was not scheduled. Dental AEs based on findings from these exams and any reported tooth or mouth events were also documented.

Efficacy assessments included USFR, the Clinical Global Impression of Severity and Change (CGI-S and CGI-C, respectively) scales in sialorrhea, the Patient Global Impression of Severity and Change (PGI-S and PGI-C, respectively) scales in sialorrhea, the DSFS-I and participant-rated DSFS (DSFS-P), and the participant-rated Drooling Impact Score (DIS) [22]. The USFR was determined at least 1 h postprandial and just before RIMA injection. Participants with PD had to be in the ON state (at least 1 h following first morning dose of PD medications). Participants cleared their mouth of excess saliva then tilted their head forward to allow saliva to pool in the floor of their mouth. They then expectorated any saliva that accumulated in their mouth into a pre-weighed cup during a 5-min collection period. The CGI-S and PGI-S scales assessed the severity of illness (sialorrhea) on a 7-point scale ranging from 1 (“normal”) to 7 (“among the most extremely ill”), and the CGI-C and PGI-C scales assessed change on a 7-point scale ranging from 1 (“very much improved”) to 7 (“very much worse”). The DIS is a 10-item questionnaire (with scores ranging 10 to 40) that evaluates the degree to which sialorrhea impacts daily activities (speech, social activities, etc.); each item is rated on a 4-point scale from 1 (“not at all”) to 4 (“very much”).

Safety and efficacy assessments (except for the DSFS-P) were obtained at clinic visits prior to first injection (day 1) and thereafter at weeks 4, 8, and 13 ± 2 (second injection visit), with subsequent visits occurring 4 and 13 weeks after each injection through week 52. The DSFS-P was assessed using a patient diary that was completed on a daily basis for the first 2 weeks following each injection and then weekly for the remainder of the cycle. Additionally, telephone follow-ups were conducted 1 and 8 weeks following injections 2, 3, and 4 to document AEs, note any medication changes, and remind participants to complete DSFS-P diaries.

Statistical Analysis

No sample size estimation was performed for this open-label study except that we planned to enroll up to 200 participants, based on the requirements of the final safety database required for drug approval; the study was terminated once sufficient participants required for safety monitoring across all RIMA studies had completed (regulatory submission required at least 100 participants with safety data for 1 year, including 65 at the 3500 U dose). Safety was analyzed for all participants who received an injection of study medication (safety population). Efficacy was analyzed for all participants in the safety population who had at least one post-injection measurement recorded for both USFR and CGI-C (intent-to-treat population). In addition, we performed an exploratory post-hoc analysis assessing efficacy on USFR in the subgroup of participants with ALS. For each treatment cycle, efficacy was assessed as change from baseline at each post-injection time point using t-tests, with baseline defined as the pre-injection assessment for that treatment cycle (i.e., day 1, and weeks 13, 26, and 39, respectively).

Results

Patient Disposition and Baseline Characteristics

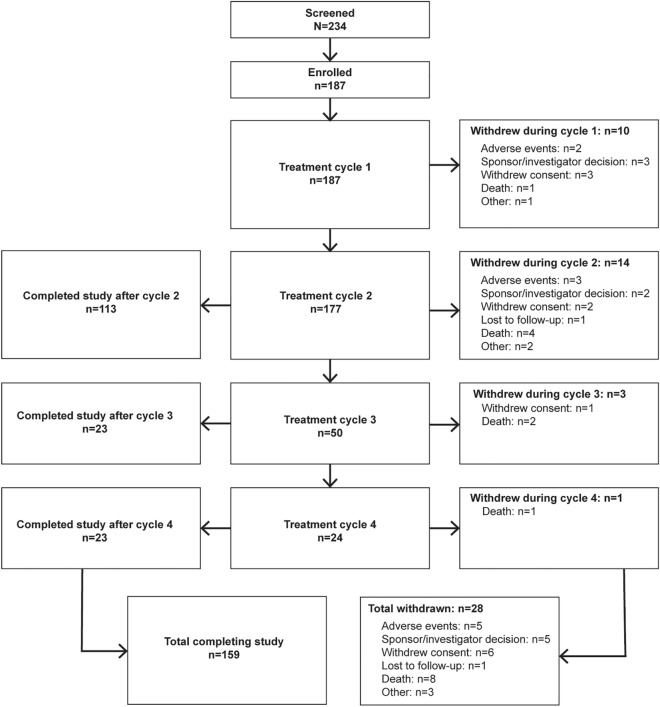

Of 234 patients screened, 187 were enrolled and received at least one injection of RIMA. Of these, 177 (94.7%) participants entered cycle 2, 50 (26.7%) entered cycle 3, and 24 (12.8%) entered cycle 4. Sufficient safety data for regulatory filing was captured prior to most participants reaching the third injection cycle, and study termination was the main reason for the lower enrollment in cycles 3 and 4. In total, 159 (85.0%) patients either completed 52 weeks or were counted as completers based on continued enrollment at the time of study termination (Fig. 1). Participants were predominately male (69.0%), and the mean ± standard deviation (SD) participant age was 64.1 ± 12.2 years (Table 1). The main etiologies of sialorrhea were PD (65.8%) and ALS (13.9%). Participants had a mean ± SD baseline USFR of 0.63 ± 0.49 g/min and a mean DSFS-I score of 6.4 ± 1.4, indicating moderate-to-severe drooling.

Fig. 1.

Participant disposition. aThe study was stopped once sufficient patients required for safety monitoring (across all ongoing rimabotulinumtoxinB trials) had completed treatment. At the time of study stoppage, no participants remained in cycle 1 and patients currently in cycles 2, 3, and 4 completed the study at the end of their current treatment cycle

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics and treatment exposure

| Characteristic | Safety set N = 187 |

|---|---|

| Demographics | |

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Male | 129 (69.0) |

| Female | 58 (31.0) |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 64.1 (12.2) |

| Age categories (years), n (%) | |

| 18–64 | 85 (45.5) |

| 65–74 | 64 (34.2) |

| 75+ | 38 (20.3) |

| Clinical history | |

| Diagnosis/cause of sialorrhea, n (%) | |

| Parkinson disease | 123 (65.8) |

| Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis | 26 (13.9) |

| Stroke | 7 (3.7) |

| Oral cancer | 5 (2.7) |

| Cerebral palsy | 4 (2.1) |

| Traumatic brain injury | 3 (1.6) |

| Medication-related | 1 (0.5) |

| Other | 18 (9.6) |

| Years since sialorrhea diagnosis | |

| Mean (SD) | 3.2 (5.1) |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 1.8 (0.8, 3.9) |

| Unstimulated salivary flow rate (g/min), mean (SD) | 0.63 (0.49) |

| Drooling frequency and severity score—investigator, mean (SD) | 6.4 (1.4) |

| Drooling frequency and severity score-patienta, mean (SD) | 5.9 (1.4) |

| Clinical global impression—severity, mean (SD) | 4.4 (0.9) |

| Patient global impression—severity, mean (SD) | 5.3 (1.2) |

| Drooling impact score, mean (SD) | 21.2 (5.9) |

| Treatment exposure | |

| Duration between injections (weeks), mean (SD)b | 13.4 (1.0) |

| Duration of exposure (weeks), mean (SD) | 31.1 (10.4) |

| Number of injections per participant, mean (SD) | 2.3 (0.8) |

| Number of injections per participant, count (n [%]) | |

| 1 injection | 10 (5.3) |

| 2 injections | 127 (67.9) |

| 3 injections | 26 (13.9) |

| 4 injections | 24 (12.8) |

| Injection method, n (%) | |

| Guided by external anatomical landmarks only | 144 (77.0) |

| Needle placement confirmed by ultrasound | 43 (23.0) |

Q1, Q3 First and third quartile, SD standard deviation

aDenominator n = 169

bCalculated for participants with at least 2 injections (n = 177)

Safety Analysis

Most participants (n = 167, 89.3%) were treated with the RIMA 3500 U total dose, with 16 participants starting at 3500 U and reducing dosage at subsequent cycles. The mean ± SD duration between injection intervals was 13.4 ± 1.0 (range 11.3–17.1) weeks (Table 1).

Overall, 58.3% of participants experienced at least one AE during the study. For most participants AEs were mild or moderate in severity, with 8.0% of participants experiencing any AE rated as severe. When analyzed by treatment cycle, the proportion of participants who experienced at least one AE was similar for cycles 1, 2, and 3 (39.5–41.2%) but somewhat lower (29.2%) for cycle 4. A summary of AEs by treatment cycle is shown in Table 2. Dry mouth and dental caries were the two most commonly reported AEs. Dry mouth occurred most frequently in cycle 1 (15.5% of patients), with lower incidence in subsequent cycles (5.6%, 2.0%, and none in cycles 2, 3, and 4, respectively), and was considered by investigators to be related to RIMA treatment in all participants. Dental caries were reported by 7.0%, 9.6%, 12.0%, and 8.3% of participants in cycles 1 through 4, respectively, and were judged to be related to RIMA treatment in 5.9%, 5.6%, 6.0%, and 4.2% of these participants, respectively. The only other AE occurring in at least 5.0% of patients in any treatment cycle was progression of ALS, which was judged to be unrelated to study treatment by investigators. Only one AE (dry mouth, reported by a single patient in cycle 1) was considered to be both severe and related to RIMA treatment; this AE led to discontinuation from the study. A total of 13 participants had AEs that led to discontinuation (n = 4, 6, 2, and 1 in cycles 1 through 4, respectively). Aside from the single participant with dry mouth in cycle 1, the remaining AEs leading to discontinuation were judged to be unrelated to RIMA treatment and appeared largely to be due to progression of underlying conditions; these included neoplasm progression (n = 3), ALS progression (n = 3), and (n = 1 each) respiratory failure, post-procedural complication, large intestinal obstruction, coronary artery disease, urosepsis, and pneumonia.

Table 2.

Adverse events by treatment cycle (safety population)

| Adverse events, n (%) | Cycle 1 (n = 187) | Cycle 2 (n = 177) | Cycle 3 (n = 50) | Cycle 4 (n = 24) | All sessions (N = 187) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any AE | 77 (41.2) | 70 (39.5) | 20 (40.0) | 7 (29.2) | 109 (58.3) |

| Any treatment-related AE | 42 (22.5) | 26 (14.7) | 4 (8.0) | 2 (8.3) | 55 (29.4) |

| Any severe AE | 5 (2.7) | 8 (4.5) | 2 (4.0) | 2 (8.3) | 15 (8.0) |

| Any AE leading to discontinuation | 4 (2.1) | 6 (3.4) | 2 (4.0) | 1 (4.2) | 13 (7.0) |

| Any serious AE | 7 (3.7) | 14 (7.9) | 3 (6.0) | 2 (8.3) | 25 (13.4) |

| Death | 1 (0.5) | 4 (2.3) | 2 (4.0) | 1 (4.2) | 8 (4.3) |

| Most common AEs (≥ 2% overall) | |||||

| Dry mouth | 29 (15.5) | 10 (5.6) | 1 (2.0) | NA | 32 (17.1) |

| Dental caries | 13 (7.0) | 17 (9.6) | 6 (12.0) | 2 (8.3) | 28 (15.0) |

| Amyotrophic lateral sclerosisa | 2 (1.1) | 8 (4.5) | 1 (2.0) | 2 (8.3) | 10 (5.3) |

| Fall | 6 (3.2) | 3 (1.7) | 1 (2.0) | NA | 9 (4.8) |

| Nasopharyngitis | 6 (3.2) | NA | NA | 1 (4.2) | 7 (3.7) |

| Urinary tract infection | 1 (0.5) | 3 (1.7) | 1 (2.0) | NA | 5 (2.7) |

| Dysphagia | 4 (2.1) | NA | NA | NA | 4 (2.1) |

| Oral candidiasis | 3 (1.6) | 2 (1.1) | NA | NA | 4 (2.1) |

| Tooth fracture | 1 (0.5) | 2 (1.1) | 1 (2.0) | NA | 4 (2.1) |

AE Adverse event, NA not applicable

aProgression of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

AESIs were reported for six (3.2%) participants, all of whom had PD: four (2.1%) participants experienced dysphagia (all in cycle 1), of whom three had history of mild dysphagia at baseline; one 1 (0.5%) participant experienced aspiration (cycle 2); and one (0.5%) participant experienced aspiration pneumonia (cycle 2). Other than the dry mouth and dysphagia events (reported above), other reported AEs that were pre-identified in the protocol as being “potentially indicative of toxin spread” were constipation (n = 2) and aspiration pneumonia (n = 1); however, these events occurred in individuals with PD and—with the exception of one of the events of constipation (n = 1)—were judged to be unrelated to RIMA treatment by the investigator.

AEs associated with dental disease were separately collated and were reported by 14.4%, 13.0%, 16.0%, and 8.3% of participants in cycles 1 through 4, respectively, with 24.1% of overall participants experiencing ≥ 1 dental AEs. Other than dental caries (reported above), dental AEs occurring in > 1 participants in any cycle included oral candidiasis (1.6%, [n = 3] in cycle 1 and 1.1% [n = 2] in cycle 2), oral discomfort (1.1% [n = 2] in cycle 1), tooth loss (1.1% [n = 2] in cycle 1), and tooth fracture (1.1% [n = 2] in cycle 2); of these, one case of candidiasis in each cycle, one case of tooth loss, and one case of tooth fracture were considered to be treatment-related.

Serious AEs occurred in 25 (13.4%) participants (3.7%, 7.9%, 6.0%, and 8.3% in cycles 1 through 4, respectively), including eight (4.3%) participants who died during the study (3 due to cancer progression, 3 due to ALS, 1 due to urosepsis, and 1 due to community-acquired pneumonia). Serious AEs (including deaths) were largely consistent with progression or sequelae of underlying neurological or oncological disease, and none were considered to be related to RIMA treatment.

Across all treatment cycles, there were no relevant findings based on assessments of laboratory parameters, vital signs, or body weight measurements.

Efficacy Analyses

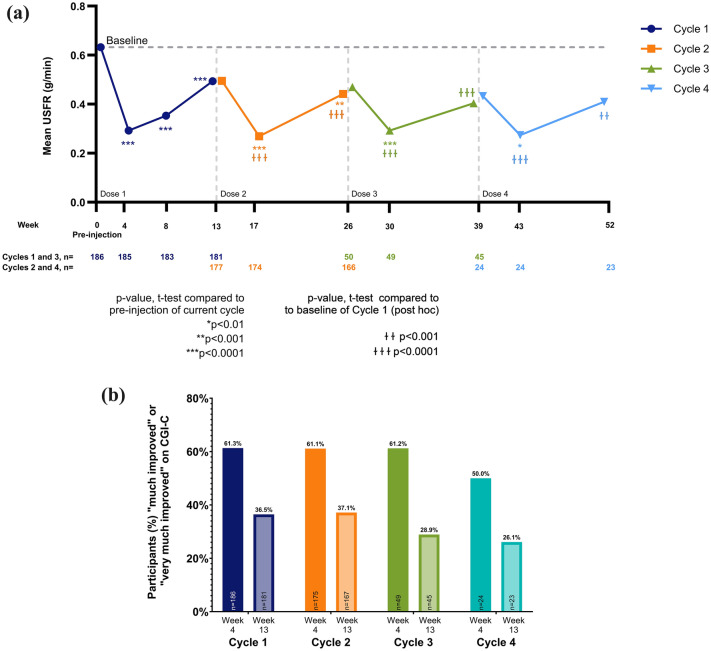

The baseline (pre-injection) USFR was highest prior to cycle 1 (mean 0.63 g/min) and lower at the baselines of subsequent cycles (0.49, 0.47, and 0.43 g/min, prior to cycles 2, 3, and 4, respectively) (Fig. 2a; Electronic Supplementary Material [ESM] Table S1). Likewise, the corresponding mean ± SD change in USFR from baseline to week 4 was also greater during cycle 1 (− 0.34 ± 0.37, p < 0.0001 vs. baseline) compared with matched timepoints in subsequent cycles (cycle 2: − 0.23 ± 0.27, p < 0.0001; cycle 3: − 0.18 ± 0.20, p < 0.0001; cycle 4: − 0.16 ± 0.23, p = 0.003). The larger changes observed during cycle 1 may be attributed to the higher pre-injection baseline compared to subsequent cycles, a possibility that is supported by the observation that the absolute USFRs at week 4 following each injection were similar across all cycles (Fig. 2a; ESM Table S2). The same general pattern was seen at week 13 (Fig. 2a; ESM S1, S2). Although changes in USFRs from pre-injection to week 13 of each cycle were significant for cycle 1 only, this also appears to be due to the higher baseline for cycle 1. Notably, a post-hoc analysis showed significant reductions in USFR at weeks 4 and 13 of all four cycles when measured relative to cycle 1 baseline (Fig. 2a).

Fig. 2.

a, b Mean unstimulated salivary flow rate (USFR) over cycles 1–4 (a) and percentage of patients rated ‘much’ or ‘very much’ improved on Clinical Global Impression of Change (CGI-C) (b). a Vertical dashed lines indicate the beginning of each cycle. Asterisks indicate p-values for the a priori-specified statistical tests comparing USFR at weeks 4, 8 (cycle 1 only), and 13 of each cycle to the pre-injection USFR for that cycle. Daggers indicate p-values for post-hoc t-tests comparing USFR at weeks 4 and 13 of cycles 2, 3, and 4 to the pre-injection baseline of cycle 1. Sample sizes for each point are provided below the graph. b The CGI-C rated the change in the participants condition (regarding sialorrhea) relative to pre-injection of the current treatment cycle. Percentages were calculated based on the number of participants at each visit (denominators shown at the base of each bar). Of the overall participant population, 57.6% of participants were rated as “much improved” or “very much improved” at week 8 of cycle 1 (the only cycle that included a week 8 CGI-C assessment). For a and b, cycles 1, 2, 3, and 4 are shown in dark blue, orange, green, and light blue, respectively.

The relevance of the observed reduction in sialorrhea was evidenced by the CGI-C and CGI-S scores, which consistently showed significant improvements from baseline to week 4 of each treatment cycle (first visit post-injection). The results of a responder analysis for CGI-C, with improvement conservatively defined as ratings of “very much improved” or “much improved,” are shown in Fig. 2b; the proportion of responders was greater at 4 weeks post-injection and declined by week 13 in all cycles. Clinician ratings of severity (CGI-S and DSFS-I) at each cycle’s baseline visit tended to decrease with subsequent treatment cycles. Likewise, patient-reported measures of severity and impact (PGI-C, PGI-S, DSFS-P, and DIS) also showed consistent efficacy at week 4, with a tendency toward reduction over repeated cycles (ESM Tables S1, S2).

Discussion

In this phase 3 open-label study, long-term, repeated treatment with RIMA for managing chronic sialorrhea in adults was generally well tolerated, and the efficacy of repeated treatment was maintained for up to 1 year. No unexpected AEs or safety signals were reported in this study. Systemic anticholinergic AEs related to RIMA treatment were not observed. Dry mouth was the most common AE but led to discontinuation in only one participant.

A higher incidence of dental caries (15.0% of overall participants) was reported compared with prior studies [3, 14, 23] and may reflect the frequent dental evaluations included as part of the study procedures. Dental caries were assessed as unrelated to RIMA treatment in a little over one third of individuals who experienced them (n/N: 10/28), and overall dental AEs were assessed as unrelated to RIMA treatment in approximately one half of individuals who experienced them (n/N: 23/45). Saliva plays a vital role in the prevention of dental caries through neutralization of acids in the dental plaque following the consumption of fermentable carbohydrates—mainly sugars—in foods and drinks. It should also be noted that people with neurological conditions leading to sialorrhea may already be at higher risk for periodontal disease. For example, multiple studies have shown people with PD experience higher rates of periodontitis and other dental problems than age-matched controls, and neurological conditions associated with reduced motor control or swallowing difficulties can affect the quality of toothbrushing, the ability to use oral rinses, and the ability to easily receive dental care [24–27]. Individuals receiving RIMA injections for troublesome sialorrhea should be counseled on strategies to improve oral health. Caregivers are often responsible for helping the patient to maintain oral hygiene and may also benefit from support. Frequent dental visits are highly recommended for all patients, and dental hygiene should be a part of the patient and caregiver education.

The present study included a subgroup of 26 participants with ALS for whom sialorrhea is common. Sialorrhea affects about 50% of individuals with ALS, with about 25% having moderate-to-severe symptoms, and can be extremely distressing for patients and care partners [28]. Currently, the American Academy of Neurology recommends that BoNT-B should be considered as a treatment strategy for individuals with ALS who have medically refractory sialorrhea (Level B), and our findings provide additional evidence of safety and effectiveness for this recommendation (ESM Table S3). No participant with ALS reported dysphagia or aspiration, and although three participants died because of ALS progression, these deaths were considered to be unrelated to RIMA treatment. The use of RIMA to reduce troublesome sialorrhea can be considered an appropriate part of palliative care for individuals with ALS.

The results of clinical efficacy measures in this study were consistent with those of the previously published phase 3, double-blind, placebo-controlled MYSTICOL study of RIMA at doses of 2500 U and 3500 U [13]. In that class I study, both doses of RIMA significantly reduced USFR at week 4 by − 0.36 (2500 U) and − 0.37 (3500 U) g/min, respectively (mean placebo-adjusted treatment difference of − 0.30 g/min for each dose; p < 0.0001), which is nearly identical to the − 0.34 g/min week 4 reduction in USFR seen in the present study. Onset of efficacy for both doses in the MYSTICOL study was seen as early as week 1, and although both doses were effective, the 3500 U dose had a longer duration of action (through week 13) than the lower 2500 U dose (which showed significant difference from placebo at week 8 but not week 13). The primary reason for choosing the 3500 U dose for the present study, however, was to provide sufficient exposure at this dose to meet US FDA requirements to establish long-term safety. The 3500 U dose was well-tolerated overall, with < 10% of participants requiring dose reduction (2500 U or 3000 U) in any subsequent treatment cycle.

The greatest magnitude of improvement from each pre-injection USFR was seen during cycle 1 in the present study; however, rather than any change in treatment effect, this may be more indicative of the greater baseline (pre-injection) USFR in cycle 1 relative to subsequent cycles. Indeed, the mean absolute USFRs at weeks 4 and 13 of cycles 2 through 4 were similar to or lower than these same timepoints in cycle 1. Most (73.8%) participants in this study were new to sialorrhea treatment, and the higher cycle 1 baseline appears to reflect this de novo status. Despite the requirement that participants should come back to baseline status before re-injection, most clinical measures showed a tendency to improve over subsequent cycles, with lower scores at the baseline of each consecutive treatment cycle. This may suggest a change in saliva production from repetitive treatments or a prolonged effect in some participants where injectors/participants did not await symptoms to fully return to baseline before the next treatment. This is common clinical practice in BoNT injections to minimize the ‘gap’ in efficacy between injection cycles. In this study, the mean ± SD duration between injection intervals was over 13 weeks. A limitation of the study design was that the investigators were asked to limit intervals to a maximum of 15 weeks. Future real-world studies may allow fully flexible dosing intervals (earlier than week 11 or later than week 15) according to clinical need to better capture the duration of clinical efficacy.

Other limitations of this study include its open-label design, and the fewer number of participants treated in cycles 3 and 4, owing to the adaptive trial design that resulted in stoppage once a sufficient number of participants had completed to fulfill FDA submission requirements (barring drop-out, all patients had the opportunity to complete at least two cycles). While the study is one of the few to include patients of varied neurologic etiologies for sialorrhea, two-thirds of participants had PD. Future studies may focus on the effectiveness of RIMA in larger populations of patients with other underlying pathologies. The current study targeted both the parotid (responsible for stimulated saliva production) and submandibular (responsible for unstimulated saliva production) glands. However, a prior study in participants with PD demonstrated efficacy when only the parotids were targeted [29], which could theoretically reduce the potential for AEs. Additionally, a greater proportion of patients in this study underwent injection using only external anatomical landmarks, as compared to external anatomical landmarks with ultrasound confirmation of needle placement within the gland (77.0% vs. 23.0%). Although no analyses were performed to compare these injection paradigms in this study, prior studies have not shown differences between these two techniques [13, 15].

Conclusion

In summary, this study provides class II evidence that RIMA 3500 U safely reduces saliva production over repeated treatment cycles through 1 year and supports the utility of RIMA in the management of troublesome sialorrhea in adults.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all of the study participants, care partners, investigators, and site personnel who made the study possible.

The OPTIMYST Study Group: Pinky Agarwal, Jason Aldred, Susan Criswell, Khashayar Dashtipour, Virgilio Gerald Evidente, Alan Freeman, Ramon A Gil, Stephen Grill, Philip Hanna, Patrick Hogan, Jennifer S. Hui, Stuart H. Isaacson, Olga Klepitskaya, Kevin Klos, Eric Dale Kramer, Mark LeDoux, Jonathan McKinnon, Guillermo D Moguel-Cobos, Rajesh Pahwa, Atul T Patel, Fredy J Revilla, Joseph Savitt, Yaryna Brozhyk, Nataliya Buchakchyiska, Lyudmyla Dzyak, Viktoriia Gryb, Iryna Khubetova, Yanosh Sanotskyy, Volodymyr Smolanka, Nataliya Voloshyna, Yuri Alekseenko, Andriy Dubenko, Zigmund Gedrevich, Sergei Likhachev, Siarhei Lialikau, Tatsyana Mikhailava, Natalya Mitkovskaya, Volha Moguchaya, Konstantin Shelepen.

Medical Writing, Editorial, and Other Assistance

Medical writing support (literature search, referencing, and editing) was provided by Anita Chadha-Patel, PhD (ACP Clinical Communications Ltd) and was funded by Supernus Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Editorial support, publication management, and graphics preparation were provided by Andrea Formella, PharmD, CMPP and Ramsey Samara, PhD, both of Supernus Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

Author Contributions

Rajesh Pahwa, Eric Molho, Khashayar Dashtipour, Ramon A Gil, Fredy J Revilla, and Stuart H Isaacson were on the study steering committee, were investigators in the OPTIMYST study, and were involved in the execution, analysis, and interpretation of results. Mark Lew was on the study steering committee, had patients participating at his affiliated investigative site at the University of Southern California, and was involved in the execution, analysis, and interpretation of results. Thomas Clinch and Peibing Qin were responsible for data analysis. Rajesh Pahwa and Stuart H Isaacson wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors were involved in interpretation of the data and in critical review and approval of the manuscript and take accountability for all aspects of the work.

Funding

The study was funded and conducted by MDD US Operations, LLC (formerly US WorldMeds, LLC; Louisville, KY, USA) and its subsidiary, Solstice Neurosciences, LLC (Malvern, PA, USA), both subsidiaries of Supernus Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (Rockville, MD, USA), which also contributed to the study’s design, execution, data collection, and management. The journal’s Rapid Service Fee was funded by Supernus Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from Supernus Pharmaceuticals, Inc. on reasonable request. Supernus Pharmaceuticals, Inc. will share study data with qualified researchers who provide valid research questions.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

Rajesh Pahwa is a member of the Editorial Board of Neurology and Therapy. Rajesh Pahwa was not involved in the selection of peer reviewers for the manuscript nor any of the subsequent editorial decisions. Rajesh Pahwa, Eric Molho, Khashayar Dashtipour, Ramon A Gil, Fredy J Revilla, and Stuart H Isaacson were all investigators in the OPTIMYST study and report fees for consultancy from Supernus Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Rajesh Pahwa reports grants from Abbott, AbbVie, Alexza, Annovis, Biogen, Bluerock, Bukwang, Cerevel, Global Kinetics, Jazz, the Michael J Fox Foundation, NeuroDerm, Neuraly, the Parkinson’s Foundation, Praxis, Roche, Sage, Scion, Sun Pharma, UCB, and Voyager; and consulting fees from Abbott, AbbVie, ACADIA, Acorda, Allevion, Amneal, Artemida, BioVie, CalaHealth, Convatec, Global Kinetics, Inbeeo, Insightec, Jazz, Kyowa, Lundbeck, Merz, Neurocrine, NeuroDerm, Ono, PhotoPharmics, Sage, Sunovion, Supernus, UCB, and Wren. Eric Molho reports consultancy fees from CNS Ratings; speaker fees from Neurocrine Biosciences; research grants from Impax Pharmaceuticals, Civitas Therapeutics, Cure Huntington’s Disease Initiative, Michael J Fox Foundation, Biogen, Acorda Therapeutics, Biohaven Pharmaceuticals; and an educational grant from Merz Neurosciences. Mark Lew reports consultancy for Supernus Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Neurocrine, Acorda, Kyowa, Amneal, UCB, Merz, Acadia, and Abbvie; and research grants from the Michael J Fox Foundation, Neuraly, NIAA, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, UCB, Inhibikase Therapeutics, Biogen, and Ono Pharma. Khashayar Dashtipour has received compensation to serve as an advisor and/or speaker from Allergan, Acadia, Abbvie, Acorda, Amneal, Cynapsus, Ipsen, Kyowa Kirin, Lundbeck, Neurocrine, Revance, Supernus, Teva, and US WorldMeds. Ramon A Gil reports fees for speaking engagements consultancy from US WorldMeds, LLC. Fredy J Revilla reports consultancy fees from US WorldMeds, LLC. Stuart Isaacson reports receipt of grants and/or research support from Abbvie, Amneal, Bial, Biogen, Ipsen, Lundbeck, Michael J Fox Foundation, Neurocrine, Neuroderm, Parkinson Study Group, Revance, Roche, Supernus, Teva, Theravance, and UCB; receipt of consulting fees from Abbvie, Acadia, Amneal, Cerevance, Kirin, Merz, Neurocrine, Neuroderm, Revance, Roche, Supernus, Teva, and UCB; and participation in a company sponsored speaker’s bureau for Abbvie, Acadia, Amneal, Kyowa Kirin, Merz, Neurocrine, Supernus, and Teva. Thomas Clinch was an employee of US WorldMeds, LLC (currently MDD, US Operations, LLC, a subsidiary of Supernus Pharmaceuticals, Inc.) at the time the study was conducted. His current affiliation is USWM, LLC (Louisville, KY, USA). Peibing Qin is an employee of Supernus Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

Ethical Approval

Institutional review boards at the participating sites approved the protocol, and the trial was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the International Conference on Harmonization Good Clinical Practice Guidelines. All patients provided written informed consent.

Footnotes

Prior presentation: Results from the OPTIMYST study have previously been presented at the 2019 International Neurotoxin Association meeting (16-19 January 2019, Copenhagen, Denmark) and the 2019 International Congress of Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders (22-26 September 2019, Nice, France).

Contributor Information

Rajesh Pahwa, Email: rpahwa@kumc.edu.

on behalf of the OPen Label Trial of Intraglandular MYobloc injections for Sialorrhea Treatment (OPTIMYST) study group:

Rajesh Pahwa, Khashayar Dashtipour, Ramon A. Gil, Fredy J. Revilla, Stuart H. Isaacson, Pinky Agarwal, Jason Aldred, Susan Criswell, Virgilio Gerald Evidente, Alan Freeman, Stephen Grill, Philip Hanna, Patrick Hogan, Jennifer S. Hui, Olga Klepitskaya, Kevin Klos, Eric Dale Kramer, Mark LeDoux, Jonathan McKinnon, Guillermo D. Moguel-Cobos, Atul T. Patel, Joseph Savitt, Yaryna Brozhyk, Nataliya Buchakchyiska, Lyudmyla Dzyak, Viktoriia Gryb, Iryna Khubetova, Yanosh Sanotskyy, Volodymyr Smolanka, Nataliya Voloshyna, Yuri Alekseenko, Andriy Dubenko, Zigmund Gedrevich, Sergei Likhachev, Siarhei Lialikau, Tatsyana Mikhailava, Natalya Mitkovskaya, Volha Moguchaya, and Konstantin Shelepen

References

- 1.Kalf JG, de Swart BJ, Borm GF, Bloem BR, Munneke M. Prevalence and definition of drooling in Parkinson’s disease: a systematic review. J Neurol. 2009;256(9):1391–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Politis M, Wu K, Molloy S, Bain PG, Chaudhuri KR, Piccini P. Parkinson’s disease symptoms: the patient’s perspective. Mov Disord. 2010;25(11):1646–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jackson CE, Gronseth G, Rosenfeld J, Barohn RJ, Dubinsky R, Simpson CB, et al. Randomized double-blind study of botulinum toxin type B for sialorrhea in ALS patients. Muscle Nerve. 2009;39(2):137–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Epstein JB, Thariat J, Bensadoun RJ, Barasch A, Murphy BA, Kolnick L, et al. Oral complications of cancer and cancer therapy: from cancer treatment to survivorship. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62(6):400–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen SY, Ravindran G, Zhang Q, Kisely S, Siskind D. Treatment strategies for clozapine-induced sialorrhea: a systematic review and meta-analysis. CNS Drugs. 2019;33(3):225–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Postma AG, Heesters M, van Laar T. Radiotherapy to the salivary glands as treatment of sialorrhea in patients with parkinsonism. Mov Disord. 2007;22(16):2430–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leibner J, Ramjit A, Sedig L, et al. The impact of and the factors associated with drooling in Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2010;16(7):475–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hockstein NG, Samadi DS, Gendron K, Handler SD. Sialorrhea: a management challenge. Am Fam Phys. 2004;69(11):2628–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Naumann M, So Y, Argoff CE, et al. Assessment: botulinum neurotoxin in the treatment of autonomic disorders and pain (an evidence-based review): report of the Therapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2008;70(19):1707–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vashishta R, Nguyen SA, White DR, Gillespie MB. Botulinum toxin for the treatment of sialorrhea: a meta-analysis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;148(2):191–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jost WH, Friedman A, Michel O, et al. SIAXI: placebo-controlled, randomized, double-blind study of incobotulinumtoxinA for sialorrhea. Neurology. 2019;92(17):e1982–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dashtipour K, Bhidayasiri R, Chen JJ, Jabbari B, Lew M, Torres-Russotto D. RimabotulinumtoxinB in sialorrhea: systematic review of clinical trials. J Clin Mov Disord. 2017;4:9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Isaacson SH, Ondo W, Jackson CE, et al. Safety and efficacy of rimabotulinumtoxinB for treatment of sialorrhea in adults: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Neurol. 2020;77(4):461–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chinnapongse R, Gullo K, Nemeth P, Zhang Y, Griggs L. Safety and efficacy of botulinum toxin type B for treatment of sialorrhea in Parkinson’s disease: a prospective double-blind trial. Mov Disord. 2012;27(2):219–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jost WH, Friedman A, Michel O, Oehlwein C, Slawek J, Bogucki A, et al. Long-term incobotulinumtoxinA treatment for chronic sialorrhea: efficacy and safety over 64 weeks. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2020;70:23–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.US Food and Drug Administration. XEOMIN (incobotulinumtoxinA) for injection, for intramuscular or intraglandular use. Precribing information. 2018. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2018/125360s073lbl.pdf. Accessed 15 Aug 2024.

- 17.US Food and Drug Administration. MYOBLOC® (rimabotulinumtoxinB) injection, for intramuscular or intraglandular use. Prescribing information. 2019. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2019/103846s5190lbl.pdf. Accessed 15 Aug 2024.

- 18.Bhidayasiri R, Truong DD. Expanding use of botulinum toxin. J Neurol Sci. 2005;235(1–2):1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arezzo JC. NeuroBloc®/Myobloc®: unique features and findings. Toxicon. 2009;54(5):690–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Proulx M, de Courval FP, Wiseman MA, Panisset M. Salivary production in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2005;20(2):204–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Evatt ML, Chaudhuri KR, Chou KL, et al. Dysautonomia rating scales in Parkinson’s disease: sialorrhea, dysphagia, and constipation—critique and recommendations by movement disorders task force on rating scales for Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2009;24(5):635–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reid SM, Johnson HM, Reddihough DS. The Drooling Impact Scale: a measure of the impact of drooling in children with developmental disabilities. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2010;52(2):e23–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ondo WG, Hunter C, Moore W. A double-blind placebo-controlled trial of botulinum toxin B for sialorrhea in Parkinson’s disease. Neurology. 2004;62(1):37–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lansdown K, Irving M, Mathieu Coulton K, Smithers-Sheedy H. A scoping review of oral health outcomes for people with cerebral palsy. Spec Care Dentist. 2022;42(3):232–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.AlMadan N, AlMajed A, AlAbbad M, AlNashmi F, Aleissa A. Dental management of patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Cureus. 2023;15(12):e50602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Auffret M, Meuric V, Boyer E, Bonnaure-Mallet M, Verin M. Oral health disorders in Parkinson’s disease: more than meets the eye. J Parkinsons Dis. 2021;11(4):1507–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen Y, Jin Y, Li K, Qiu H, Jiang Z, Zhu J, et al. Is there an association between Parkinson’s disease and periodontitis? A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Parkinsons Dis. 2023;13(7):1107–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Garuti G, Rao F, Ribuffo V, Sansone VA. Sialorrhea in patients with ALS: current treatment options. Degener Neurol Neuromuscul Dis. 2019;9:19–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Racette BA, Good L, Sagitto S, Perlmutter JS. Botulinum toxin B reduces sialorrhea in parkinsonism. Mov Disord. 2003;18(9):1059–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from Supernus Pharmaceuticals, Inc. on reasonable request. Supernus Pharmaceuticals, Inc. will share study data with qualified researchers who provide valid research questions.