Abstract

Introduction

In advanced Parkinson's disease (aPD), ‘ON-time’ indicates periods of better symptom control, with ‘good ON-time (GOT)’ indicating control without troublesome dyskinesia. Despite its importance, the impact of increased ‘GOT’ on aPD outcomes is understudied. This study aims to evaluate the clinical, humanistic, and economic value of incremental hourly increases in ‘GOT’ for people with aPD.

Methods

The study analyzed data from people with aPD across seven countries, using the Adelphi Parkinson's Disease Specific Program survey (2017–2020). ‘GOT’ (calculated from self-reported ON/OFF-time and the proportion of troublesome dyskinesia time) was normalized to a 16-h day. Outcomes included symptom control, medication use, falls, activities of daily living (ADLs), quality of life (QoL), and healthcare resource utilization (HRU). Regression models evaluated relationships between incremental ‘GOT’ hours and outcomes.

Results

Of 802 patients (mean [standard deviation; SD] age, 76.1 [8.9] years; male, 60.3%) included in the analysis, mean (SD) ‘GOT’ was 13.1 (2.7) hours/day. Hourly increases in ‘GOT’ were associated with lower likelihood of reporting uncontrolled motor (odds ratio [OR] 0.79; 95% confidence interval (CI) [0.62, 1.01]) and non-motor symptoms (OR 0.88; 95% CI [0.80, 0.96]), taking ≥ 2 PD medication classes (OR 0.91; 95% CI [0.86, 0.97]) and lower fall risk (incidence rate ratio 0.91; 95% CI [0.87, 0.95]). Hourly increases in ‘GOT’ were significantly associated with reduced humanistic burden (greater ADL independence, OR 1.19; 95% CI [1.04 1.37]) and improved QoL (for Parkinson’s Disease Questionnaire [PDQ]-39: coefficient − 1.49; 95% CI [− 2.46, − 0.52]) and with reduced economic burden, with annual total HRU cost-savings of $8602.24 (95% CI − $12,192.70 to $5011.77).

Conclusions

In this multi-country, real-world study of people with aPD, hourly increases in ‘GOT’ were associated with improved clinical outcomes, greater humanistic value, and reduced economic burden. Interventions that maximize improvement of ‘GOT’ should be considered for people with aPD adequately controlled on current therapy.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40120-025-00765-3.

Keywords: Advanced Parkinson’s disease, Clinical, Economic, Humanistic, ON-time, Troublesome dyskinesia

Plain Language Summary

For most people with advanced Parkinson’s disease, the waking day is characterized by periods when their symptoms are poorly controlled (OFF-time) and periods of better symptom control (ON-time). During ON-time, patients often experience involuntary muscle movements (called dyskinesia), which may be mild and non-problematic or may be more severe and troublesome. When patients are ON and have no troublesome dyskinesia (i.e., no dyskinesia or mild dyskinesia), this can be referred to as ‘good ON-time.’ While it is logical to assume that ‘good ON-time’ is preferred by patients, little is known about the association of ‘good ON-time’ with the burden of disease, patient quality of life or healthcare costs. This research sought to measure the impact of hourly increases in ‘good ON-time’ in 802 people with advanced Parkinson’s disease. The researchers showed that for every 1 h more of ‘good ON-time’ during the waking day, there was a 21% lower likelihood of the person having uncontrolled motor symptoms, a 9% lower risk of falls, a 19% better chance that the person would be able to do daily tasks independently, and a 49% chance of them having a better quality of life. One hour per day increases in ‘good ON-time’ also reduce hospitalization and visits to the doctor and thus reduced the cost of treating people with advanced Parkinson’s disease. The researchers carrying out this study suggest that increasing ‘good ON-time’ as much as possible should be a goal of treatment of advanced Parkinson’s disease.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40120-025-00765-3.

Key Summary Points

| Why carry out this study? |

| Despite its importance, there is limited understanding of the impact of improved ON-time hours on advanced Parkinson’s disease (aPD) outcomes |

| This study evaluated the clinical, humanistic, and economic value of incremental hourly increases in ‘good ON-time’ (control without troublesome dyskinesia) for people with aPD |

| What was learned from the study? |

| Hourly increases in ‘good ON-time’ in people with aPD were associated with a lower likelihood of uncontrolled motor or non-motor symptoms, greater independence in daily activities, and reduced economic burden |

| Patients with aPD should be considered for treatments that maximize improvements of ‘good ON-time’, to ensure optimal benefit in disease outcomes |

Introduction

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a progressive neurological disorder primarily characterized by motor symptoms such as bradykinesia, resting tremor, and rigidity [1]. As PD progresses, new motor and non-motor symptoms develop, and existing symptoms worsen in severity, leading to decline in quality of life (QoL) and activities of daily living (ADLs) [2–5]. Advanced PD (aPD) has been associated with greater care partner burden than earlier stages of the disease [6]; as the disease progresses, both the patient and the care partner incur an increasing economic burden [7]. Societal costs are also incurred in terms of greater medication use and healthcare resource utilization (HRU) [8–10].

aPD is associated with dyskinesia and motor fluctuations, and patients may experience increasing frequency and severity of OFF-states at the expense of time spent in an ON-state. Identification of aPD is not well defined, although clinical screening criteria have been proposed [11, 12]. For motor symptoms, these criteria include taking ≥ 5 doses of oral levodopa per day, having OFF symptoms for ≥ 2 h per waking day, or having ≥ 1 h of troublesome dyskinesia per waking day, and for non-motor symptoms, these criteria include mild dementia or non-transitory troublesome hallucinations [11, 12]. In addition, proposed clinical screening criteria for functional impairment include repeated falls despite optimal treatment and difficulty with ADLs [11, 12]. Recent studies [13, 14] have shown that increased OFF-time correlates with higher HRU and decreased QoL in people with PD. ON-time in people with aPD refers to periods of relatively better controlled motor and non-motor symptoms. Of particular importance is 'good ON-time,' during which patients experience better symptom control without troublesome dyskinesia [15]. Troublesome dyskinesia can significantly impact a patient’s QoL and increase the burden of disease for both the patient [5] and the care partner [16], making changes in the amount of ‘good ON-time’ a crucial factor in disease management.

Implementation of device-aided therapies (DATs) for aPD is effective in reducing OFF-time and increasing or stabilizing 'good ON-time' [17–21]. Recent analyses of ON-time found that, in appropriate candidates, initiation of DATs for aPD can result in more rapid onset of ‘good ON-time’ in the mornings and greater consistency of ‘good ON-time’ throughout the waking day [22]. However, nearly half of people with aPD have not discussed DATs with their healthcare providers, potentially missing out on these benefits [23].

Understanding the impact of ON- and OFF-time on clinical, humanistic, and economic burdens in aPD is critical, and quantifying how incremental improvements in 'good ON-time' could reduce these burdens is a necessary first step. Due to the lack of specific data on this topic, we initiated an analysis using the large dataset from the Adelphi Parkinson's Disease Specific Programme™ (DSP). This study aims to evaluate the clinical, economic, and humanistic value of incremental hourly 'good ON-time' in people with aPD.

Methods

This was a secondary analysis of real-world data collected from the Parkinson’s DSP [24]. The Parkinson’s DSP is a large, cross-sectional survey of people with PD and the neurologists involved in their care, conducted in G7 countries (France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Spain, UK, and the USA) between 2017 and 2020 (Wave VII and VIII). The Parkinson’s DSP was a single point-in-time survey that collected data from physicians, patients, and care partners; follow-up data were not obtained.

A complete description of the survey methods has been previously published and validated [24–26]. Briefly, qualified neurologists were identified from public lists of healthcare professionals and invited to participate if they were responsible for treatment decisions for people with PD. Participating neurologists were instructed to complete a record form for the next 12 consecutive people with PD they consulted with in clinical practice. Each patient for whom the physician completed a record form was invited to complete a patient-reported questionnaire and upon agreement provided their informed consent to participate. If the patient had a care partner with them at the point of consultation, they were invited to complete a care partner-reported questionnaire and upon agreement provided their informed consent to participate.

This survey did not require ethics committee approval as data collection was undertaken in line with European Pharmaceutical Marketing Research Association (EphMRA) guidelines [27]. Each survey was performed in full accordance with relevant legislation at the time of data collection, including the US Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act 1996 (HIPAA) [28] and Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act (HITECH) legislation [29]. The study was submitted to the US Western Institutional Review Board and the appropriate waiver provided (institutional review board number AG8689). The respondents provided informed consent prior to questionnaire completion and for use of their anonymized and aggregated data for research and publication in scientific journals. All data were fully de-identified prior to receipt by Adelphi Real World (ARW). All aspects of these data, i.e., methodology, materials, data, and data analysis, that support the findings of this survey are the intellectual property of ARW.

Study Population

Physicians recruited the first 12 consecutive patients who visited for PD management to participate in this study. Patients were included in this analysis if they were determined by physician judgment to have aPD on or before the date they were included in the study (according to the physician’s answer to a single question: How would you describe this patient’s overall condition currently? Possible answers: early-stage PD [mild]; intermediate stage PD [moderate to severe]; aPD [late or severe]). Additional inclusion criteria were age ≥ 18 years and receiving only oral therapy for PD and DAT-naïve (i.e., naïve to levodopa/carbidopa intestinal gel, deep brain stimulation, and continuous subcutaneous apomorphine infusion).

Measures and Variables

The Parkinson’s DSP survey reflects current clinical practice by including patient, provider, and care partner completed patient record forms (PRFs), involving clinician information and patient-reported outcomes (PROs). Patient’s clinical and demographic characteristics including age (continuous), sex (categorized as male/female), comorbidity measured as number of conditions (continuous), Charlson comorbidity index (categorized as 1–2 as mild, 3–4 as moderate, ≥ 5 as severe and high score as more severe comorbidity), country, and ethnic origin (categorical) were measured. In addition, patients’ psychosocial status, including home circumstances (categorized as living alone or with spouse/friends/family, nursing home, sheltered housing, homeless, other, and do not know), employment status (categorized as working full time or part time, on long-term sick leave, homemaker student, retired, unemployed, and do not know), and care partner requirement (categorized as yes or no), were collected and evaluated.

Country-specific unit costs were used to obtain mean costs for each healthcare resource utilized (i.e., hospitalization, emergency room [ER] visits, consultation, scans, care partner hour requirement, and respite care). Country-specific consumer price index (CPI) was used to adjust costs to 2024 values. Unit costs for the US (US dollars) were obtained from the Medicare Procedure Price Lookup and the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule [30]. UK unit costs (GBP) were obtained from the National Health Service (NHS) National Schedule of Reference Costs [31]. Additional literature reviews were conducted to convert pounds to euros or obtain unit costs relevant for Spain, Italy, France, and Germany (reported as euros). Japan unit costs (reported as Japanese yen) were obtained from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan (MHLW) [32].

Specific questions on the PRF captured whether patients experienced OFF episodes and, if so, the estimated mean hours of daily OFF-time based on each patient’s typical experience/state at the time of the survey. Total ON-time was then calculated as: total ON-time = (16 h) − (OFF-time normalized to 16-h waking day). Among patients recorded as having dyskinesia, ON-time without troublesome dyskinesia (‘good ON-time’) was calculated using the total ON-time and the answers to two questions on the PRF: “On average, how many hours a day does this patient experience dyskinesia?” and “What proportion of the patient’s total time with dyskinesia per day is rated as troublesome?” (‘good ON-time’ = total ON-time − [proportion with troublesome dyskinesias × hours with dyskinesia]).

Outcomes assessed included clinical and humanistic factors (number of controlled/uncontrolled motor symptoms or non-motor symptoms, falls in the prior 12 months, or proportion of patients performing ADLs independently [judged as completion of all ADLs without support], Movement Disorder Society Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale [MDS-UPDRS] total score [all parts], Zarit Burden Interview [ZBI], EuroQol [EQ]-5D and PD-related QoL [Parkinson’s Disease Questionnaire; PDQ-39]) along with resource use (consultations, hospital visits and care in the prior 12 months; assessed using country-specific unit costs) and costs (assessed using country-specific CPI) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Clinical, humanistic, and healthcare resource utilization outcomes measured in this analysis

| Outcome | Scoring | Regression model used and outcome reporting |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical | ||

|

“Which of the following symptoms is the patient currently experiencing?” Motor symptoms Shuffling walk, freezing of gait, falling/imbalance, dysphagia, lack of arm swing, micrographia, tremor at rest, tremor on action, rigidity, bradykinesia, lack of facial expression, stoop, blepharospasm, pain (Parkinson’s related), finger tapping For each symptom selected: “How well are the patient’s current symptoms being controlled?” Full, partial, or not controlled |

Uncontrolled vs controlled Controlled symptoms defined as any symptoms under full control Uncontrolled symptoms defined as any symptoms under partial control or not controlled |

Number of uncontrolled/controlled motor symptoms Logistic regression OR |

|

“Which of the following symptoms is the patient currently experiencing?” Non-motor symptoms Dysosmia, confusion, depression/mood, anxiety, poor concentration, short-term memory loss, difficulty planning activities, delusions, hallucinations, non-transitory hallucinations, poor impulse control, other cognitive impairment, behavioral problems, drooling, stutter/impaired speech, muscle ache, physical fatigue/low energy, sexual dysfunction, apathy, constipation, excessive sweating, urinary problems, skin problems, dizziness For each symptom selected: “How well are the patient’s current symptoms being controlled?” Full, partial, or not controlled |

Uncontrolled vs controlled Controlled symptoms defined as any symptoms under full control Uncontrolled symptoms defined as any symptoms under partial control or not controlled |

Number of uncontrolled/controlled non-motor symptoms Logistic regression OR |

| “How many falls has this patient had in the last 12 months in relation to their Parkinson’s disease (with or without being admitted to hospital)?” | Physician-reported |

Negative binomial regression IRR |

| “Please provide details of ALL of this patient’s CURRENT Parkinson’s disease drug therapy, even if not prescribed during this visit” |

Categorical by medication class: Levodopa (IR levodopa/carbidopa; CR levodopa/carbidopa; Stalevo; numient/Rytary; Inbrija) Dopamine agonists (pramipexole [standard form and once daily]; ropinirole [standard form and once daily]; rotigotine; bromocriptine; cabergoline; pergolide) MAOB inhibitors (rasagiline; selegiline; safinamide) COMT inhibitors (entacapone; tolcapone; opicapone) NMDA antagonists (amantadine; ER amantadine) A2a antagonists (Nouriast) device-aided therapy (LCIG; DBS; apomorphine pump; apomorphine pen) |

Negative binomial regression IRR |

| Movement Disorder Society Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (MDS-UPDRS) total score (all parts) | Score 0–272; higher score indicates worse disability |

General linear regression Regression coefficient |

| Humanistic | ||

|

“Which of the following does this patient require assistance in managing?” Activities of daily living (ADL) Communication with others, getting in and out of bed, preparing meals/cooking food, eating, finances, getting dressed/washed, going to the toilet, shopping, traveling out of home, using household appliances, taking medication when required, planning and organizing everyday activities, gardening, other (specify), none of the above, do not know |

Independent vs not independent Independence was defined as completion of all ADLs without support |

Negative binomial/logistic regression OR |

| QoL measured by the EuroQol 5-Dimension (EQ-5D) and EQ-5D visual analog scale (VAS) | EQ-5D score 0–1; higher score indicates best health; VAS score 0–100; higher score indicates best health |

General linear regression Regression coefficient |

| Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale total score (UPDRS) | Score 0–199; higher score indicates worse disability |

General linear regression Regression coefficient |

| PD-related QoL Questionnaire-39 (PDQ-39) | Score 0–100; higher scores indicate worst QoL |

General linear regression Regression coefficient |

| Caregiver burden as measured by the Zarit Burden Interview (ZBI) | Score 0–88; higher scores indicate greater burden |

General linear regression Regression coefficient |

| Economic (healthcare resource utilization in the last 12 months) | ||

| “How many hospitalizations, including surgery, has the patient had in the last 12 months in relation to their Parkinson’s disease?” |

Number of hospitalizations in the last 12 months Cost of hospitalization because of PD will be evaluated |

Negative binomial regression OR |

| “How many times has this patient visited the ER in the last 12 months in relation to Parkinson’s (with or without being admitted)?” |

Number of ER visits in the last 12 months Cost of ER visits will be evaluated |

Negative binomial regression IRR |

|

“Involved with Parkinson’s disease management over the last 12 months” Self, primary care physician, neurologist, geriatrician, movement disorder specialist, peritoneal dialysis nurse, psychiatrist, psychogeriatrician, gastroenterologist, social worker, other |

Number of consultations related to PD in the last 12 months Cost of consultations will be evaluated |

Negative binomial regression IRR |

|

“Please indicate the number of times each scan/imaging has been conducted in the last 12 months?” Magnetic resonance imaging, functional magnetic resonance imaging, dopamine transporter, computed tomography, positron emission tomography, single-photon emission computed tomography, magnetic resonance spectroscopy, diffusion tensor imaging, other |

Number of scans/imaging for PD in last 12 months Use unit costs to determine mean costs |

Negative binomial regression IRR |

|

Professional caregiver status District nurse, home help, nursing home staff, physiotherapist, psychiatric nurse, social worker, speech therapist, other |

Yes vs no |

Logistic regression OR |

|

Non-professional caregiver status Partner/spouse, child, other relative, friend, volunteer, other |

Yes vs no |

Logistic regression OR |

|

“Does the patient receive respite care?” “How many times in the last 12 months have they received respite care?” “Duration of last period of respite care” |

‘Yes’ or ‘no;’ times used in last 12 months; duration of last period of respite care Use unit costs to determine mean costs |

Logistic regression OR |

| ICU admissions | Number of ICU admissions |

Negative binomial regression OR |

| Total costs | Total costs |

Two-part model using a generalized linear regression OR/regression coefficient |

DBS, deep brain stimulation; IRR, incidence rate ratio; OR, odds ratio; ER, emergency room; ICU, intensive care unit; LCIG, levodopa/carbidopa intestinal gel; PD, Parkinson’s disease; QoL, quality of life

Specific permissions were not required for any scales and indexes used, and all standard licensing requirements were met.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were provided for each of the clinical, economic, and humanistic outcomes. For continuous variables, mean and standard deviation (SD) were described; for categorical variables, number of patients and percentage were described.

Based on the outcome type, the following regression models were used to evaluate the relationship between incremental ‘good ON-time’ and each outcome: continuous outcomes were evaluated using general linear regression; binary outcomes used logistic regression; count outcomes used negative binomial regressions; ordered categories used ordered logistic regression; non-ordered categories used multinomial logistic regressions; cost data used a two-part model with a generalized linear regression. Regression models were adjusted for age (continuous), sex (male or female), and mean Charlson Comorbidity Index [33] (continuous) and were reported as odds ratios (ORs), incidence rate ratios (IRRs), or regression coefficients (Table 1). Regression model and reporting used per outcome are presented in Table 1. In addition, post hoc sensitivity analyses were conducted in patients with Hoehn and Yahr stage 3–5 disease to assess the impact of extreme mobility limitation on outcomes. All statistical analyses were conducted on the population from all G7 countries as well as for individual regions (Europe, USA and Japan). Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05 for all analyses, and all analyses were conducted in Stata version 17.0 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Data for 802 people with aPD were included in the current analysis (Table 2). Patients had a mean age of 76.1 years when they were diagnosed with PD and had PD for an average of 9.3 years when data were collected for this study. Of these 802 patients, 671 (85.8%) required a care partner for daily needs. However, completed ZBI data were available for only 183 care partners, representing 22.8% of the total care partner population. Most (62.3%) people with aPD received ≥ 2 different classes of treatment for their PD, commonly levodopa (92.6% of patients), dopamine agonist (40.3%), and MAO-B inhibitor (27.7%). When stratified by region, patient characteristics were generally similar, but in Japan patients had a numerically higher Hoehn and Yahr score and numerically lower frequency of being on long-term sick-leave/retired and comorbidities than in the USA and Europe (Supplementary Table 1).

Table 2.

Characteristics of people with aPD included in the current assessment

| Characteristic | All (G7) (n = 802) |

|---|---|

| Mean (SD) age, years | 76.1 (8.9) |

| ≥ 65 years, n (%) | 727 (90.6) |

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Male | 484 (60.3) |

| Female | 318 (39.7) |

| Mean (SD) time since diagnosis, years | 9.3 (5.3) |

| Mean (SD) Hoehn and Yahr score | 3.8 (0.9) |

| Hoehn and Yahr category, n (%) | |

| 1 | 14 (1.7) |

| 2 | 60 (7.5) |

| 3 | 184 (22.9) |

| 4 | 356 (44.4) |

| 5 | 188 (23.4) |

| Country, n (%) | |

| France | 94 (11.7) |

| Germany | 110 (13.7) |

| Italy | 60 (7.5) |

| Japan | 115 (14.3) |

| Spain | 72 (9.0) |

| UK | 118 (14.7) |

| USA | 233 (29.1) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |

| White/Caucasian | 611 (76.2) |

| Asian | 138 (17.2) |

| Black | 34 (4.2) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 10 (1.2) |

| Other | 9 (1.1) |

| Employment status, n (%) | |

| Employed and working | 25 (3.2) |

| Student/homemaker | 66 (8.4) |

| Unemployed | 46 (5.8) |

| Long-term sick-leave/retired | 651 (82.6) |

| Home circumstances, n (%) | |

| Lives alone | 63 (7.9) |

| Lives with friends/family | 109 (13.7) |

| Lives with spouse/partner | 441 (55.5) |

| Nursing home/sheltered housing | 175 (22.0) |

| Homeless | 1 (0.1) |

| Other | 5 (0.6) |

| Number of comorbid conditions, n (%) | |

| 0 | 107 (13.3) |

| 1 | 150 (18.7) |

| 2–3 | 303 (37.8) |

| 4 or more | 242 (30.2) |

| Mean (SD) Charlson Comorbidity Index | 1.1 (1.5) |

aPD, advanced Parkinson’s disease. SD, standard deviation

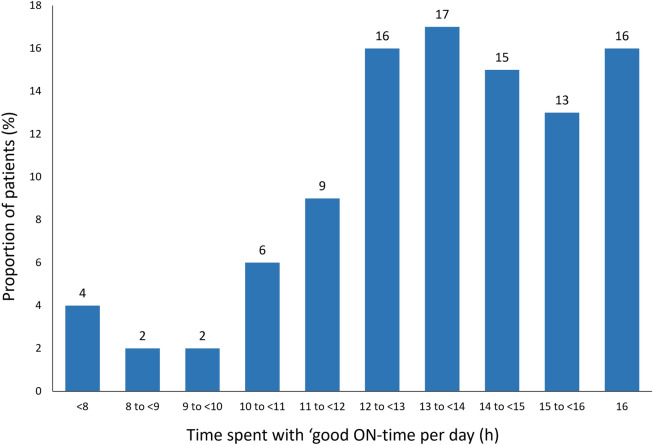

Patients had a mean (SD) of 13.1 (2.7) h of ‘good ON-time’ and 3.5 (3.7) h of OFF-time. The proportion of patients with 16 h of ‘good ON-time’ was 16.2% (Fig. 1). Mean (SD) ‘good ON-time’ was broadly similar in different regions (USA: 13.4 [2.1] h, Europe: 13.1 [2.7] h, Japan: 12.5 [3.6] h) (Supplementary Table 1)].

Fig. 1.

Distribution of daily ON-time without troublesome dyskinesia in people with aPD in the Parkinson’s DSP (normalized to a 16-h day), N = 802. DSP, disease-specific program; aPD, advanced Parkinson’s disease; h, hours

Impact of ‘Good ON-Time’ on Burden of Disease

Clinical Burden

Most people with aPD in the Parkinson’s DSP reported ≥ 1 uncontrolled motor (97.5%) and non-motor symptoms (82.0%; Supplementary Table 2). Descriptive stratified analysis of clinical, humanistic, and economic burden in people with aPD by country/region is presented in Supplementary Table 3. Regression analysis revealed that increased 'good ON-time' was significantly associated with improved outcomes in people with aPD. For every 1-h increase in 'good ON-time,' there was a 21% lower likelihood of uncontrolled motor symptoms (OR 0.79; 95% confidence interval, CI [0.62–1.01]; p = 0.060) and a 12% lower likelihood of uncontrolled non-motor symptoms (OR 0.88; 95% CI [0.81–0.96]; p = 0.004). Additionally, increased 'good ON-time' corresponded to a 9% reduced incidence of falls (IRR 0.91; 95% CI [0.87–0.95]; p < 0.001) in the previous year and a 9% lower likelihood of taking two or more PD medications (IRR 0.91; 95% CI [0.86–0.97]; p = 0.006; Table 3). Sensitivity analyses of patients with a Hoehn and Yahr score of 3–5 demonstrated similar results (Supplementary Table 4).

Table 3.

Regression analyses on the impact of incremental ‘good ON-time’ on clinical, humanistic, and economic burden in the G7 population

| Outcome | Change in burden with every 1-h increase in ‘good ON-time,’ adjusted ratio/coefficient (95% CI) | p value |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical burden | ||

| Uncontrolled motor symptoms, OR | 0.79 (0.62, 1.01) | 0.060 |

| Uncontrolled non-motor symptoms, OR | 0.88 (0.84, 0.96) | 0.004* |

| Number of falls in last 12 months relating to PD, IRR | 0.91 (0.87, 0.95) | < 0.001* |

| Number of PD treatment classes (1 vs 2 +), IRR | 0.91 (0.86, 0.97) | 0.006* |

| MDS-UPDRS total score (all parts), coefficient | − 2.68 (− 6.18, 0.82) | 0.129 |

| Humanistic burden | ||

| ADL independence, OR | 1.19 (1.03, 1.37) | 0.013* |

| UPDRS total score, coefficient | − 3.70 (− 6.03, − 1.36) | 0.002* |

| EQ-5D, coefficient | 0.03 (0.01, 0.05) | 0.001* |

| EQ-5D VAS, coefficient | 1.89 (0.95, 2.82) | < 0.001* |

| PDQ-39, coefficient | − 1.49 (− 2.46, − 0.52) | 0.003* |

| ZBI, coefficient | − 0.74 (− 2.08, 0.60) | 0.276 |

| Economic burden (healthcare resource utilization and costs) | ||

| Hospitalizations (including surgery) in the last 12 months, OR | 0.89 (0.83, 0.95) | 0.001* |

| Hospitalization costs ($), coefficient | − 2496.98 (− 5708.52, 714.55) | 0.128 |

| ICU admission in last 12 months, OR | 0.73 (0.60, 0.89) | 0.002* |

| Number of ER visits in last 12 months, IRR | 0.92 (0.86, 0.98) | 0.013* |

| ER visit costs ($), coefficient | − 2176. 10 (− 4389.16, 36.95) | 0.054 |

| Number of PD consultations in last 12 months, IRR | 0.99 (0.94, 1.05) | 0.851 |

| Consultation costs ($), coefficient | − 11.96 (− 108.19, 84.26) | 0.807 |

| Number of scans for PD in last 12 months, IRR | 1.00 (0.95, 1.05) | 0.994 |

| Scan costs ($), coefficient | 15.67 (− 36.12, 67.46) | 0.553 |

| Respite care, OR | 0.93 (0.87, 1.00) | 0.051 |

| Respite care costs ($), coefficient | − 12,344.30 (− 24,598.03, − 90.57) | 0.048* |

| Professional care partner status, OR | 0.89 (0.83, 0.95) | < 0.001* |

| Professional care costs ($), coefficient | − 51.88 (− 1588.65, 1484.89) | 0.947 |

| Non-professional care partner status, OR | 1.00 (0.94, 1.06) | 0.968 |

| Mean total costs ($), coefficient | − 8602.24 (− 12,192.70, − 5011.77) | < 0.001* |

ADL, activity of daily living; CI, confidence interval; EQ-5D, EuroQol 5-Dimension; EQ-5D VAS, EuroQol 5-Dimension visual analog scale; ER, emergency room; ICU, intensive care unit; IRR, incidence rate ratio; MDS, Movement Disorder Society; OR, odds ratio; PD, Parkinson’s disease; PDQ-39, Parkinson’s Disease Questionnaire-39; UPDRS, Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale; ZBI, Zarit Burden Interview

*Values are statistically significant

Stratified analysis based on hours of 'good ON-time' demonstrated that patients with longer durations of 'good ON-time' had better symptom control compared to those with shorter durations. Specifically, patients with 16 h of 'good ON-time' per day were significantly more likely to have controlled motor and non-motor symptoms (based on physician record), experienced fewer falls, and were taking fewer PD treatment classes compared to those with < 16 h of 'good ON-time' (Supplementary Table 2). Although differences were less marked, a similar pattern was observed among those with ≥ 12 h of 'good ON-time' compared with those with < 12 h of 'good ON-time' (Supplementary Table 2). The proportion of patients with 16 h of ‘good ON-time’ and ≥ 12 h of ‘good ON-time’ was similar between the regression and sensitivity analyses.

Humanistic Burden

Overall, 7.5% of people with aPD independently performed ADLs (Supplementary Table 2). Regression analysis showed that each additional hour of 'good ON-time' was associated with a 19% greater likelihood of ADL independence (OR 1.19; 95% CI [1.03–1.37]; p = 0.013) and better PD-related QoL (regression coefficient − 1.49; 95% CI [0.62–1.01]; p = 0.003). Care partner burden, as measured by the ZBI, did not significantly change with incremental increases in 'good ON-time' (regression coefficient − 0.74; 95% CI [− 2.08 to 0.60]; p = 0.276; Table 3). These results were similar in the sensitivity analyses of patients with a Hoehn and Yahr score of 3–5 (Supplementary Table 4).

Similarly, when stratified by duration of ‘good ON-time,’ patients with 16 h of 'good ON-time' per day were significantly more likely to be ADL independent and had slightly better QoL compared to those with less 'good ON-time' despite similar care partner burden across groups (Supplementary Table 2). Significantly better QoL was observed among patients with ≥ 12 h of ‘good ON-time’ compared with those with < 12 h of ‘good ON-time’ (p ≤ 0.01; Supplementary Table 2).

Economic Burden

Approximately a third of people with aPD required hospitalization over the last 12 months or were cared for by a paid professional care partner. While < 20% of patients required respite care, this was the biggest contributor to the total HRU costs ($28,738 of a total $73,609 annually; Supplementary Table 2). Every 1-h increase in ‘good ON-time’ was associated with an 11% lower likelihood of hospitalization (OR 0.89; 95% CI [0.83–0.95] p = 0.001) and reduction in the risk of intensive care unit (ICU) admission (OR 0.73; 95% CI [0.60–0.89]; p = 0.002), ER visits (IRR 0.92; 95% CI [0.86–0.98]; p = 0.013) or the need for professional care (OR 0.89; 95% CI [0.83, 0.95]; p < 0.001). Total HRU costs for people with aPD were significantly reduced with every 1-h increase in ‘good ON-time’ (regression coefficient – $8602.78; p < 0.001) (Table 3). As for clinical and humanistic burden, sensitivity analyses of patients with a Hoehn and Yahr score of 3–5 demonstrated similar results to the regression analysis of patients with Hoehn and Yahr scores of 1–5 (Supplementary Table 4).

Similarly, the group of patients with 16 h of ‘good ON-time’ per day had considerably lower total HRU costs than those with less ‘good ON-time’ largely because of the lower requirement for respite care (Supplementary Table 2). Patients with ≥ 12 h of ‘good ON-time’ had significantly lower total HRU costs than those with < 12 h of ‘good ON-time’ (p = 0.0008; Supplementary Table 2).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first analysis examining the impact of incremental 'good ON-time' on clinical, humanistic, and economic outcomes in aPD. Our findings indicate that increasing 'good ON-time' leads to a significant reduction in humanistic burden, resulting in an increased likelihood of ADL independence and enhanced overall QoL. Furthermore, our results show that augmenting 'good ON-time' reduces clinical burden, characterized by significant decreases in the number of uncontrolled non-motor symptoms, fall frequency, and the number of PD treatment classes required. Additionally, increasing 'good ON-time' leads to reduced HRU, including fewer hospitalizations, ER visits, ICU admissions, and the need for professional care. Notably, achieving 16 h of 'good ON-time' daily confers substantial benefits, including improvements in controlled motor and non-motor symptoms, reduced PD-related falls, decreased number of PD treatment classes, enhanced ADL independence, lower Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) total scores, higher EQ-5D visual analogue scale (VAS) scores, and reduced non-professional care partner utilization and respite care needs compared to < 16 h of 'good ON-time' per day.

Our current analysis helps to strengthen previous research by focusing on increasing ‘good ON-time’ (ON-time with no troublesome dyskinesia), which may have greater impact on patients’ QoL than OFF-time reduction [34]. This may be particularly important in aPD as some of these patients have troublesome dyskinesia [35]. However, our analysis did not directly compare the impacts of increased ‘good ON-time’ and reduced OFF-time on QoL; therefore, this comparison should be further evaluated into future studies to substantiate these results. We suggest that the improvements in humanistic outcomes of PDQ-39, EQ-5D, and EQ-VAS with incremental increases in ‘good ON-time’ reported in our study can be translated into clinically significant improvements. For example, a 1-h improvement in ON-time was associated with a 1.5-point reduction in PDQ-39 score. The minimal clinically important difference (MCID) for PDQ-39 is − 4.72; therefore, an increase of 3–4 h of ‘good ON-time’ would translate into a clinically significant improvement. The impact of OFF-time on QoL and ADL has previously been reported, where an investigation of QoL in people with aPD using the Parkinson's Disease Questionnaire Summary Index (PDQ-8 SI), which includes measurement of ADL, found a significant negative effect of OFF-time duration on overall QoL [36].

Increased good ON-time lowers the likelihood of falls or other clinical indicators of uncontrolled symptoms, which could be the reason for the reduction in the utilization of non-preventative care services like ER visits (IRR 0.92; p = 0.013) or hospitalizations (OR 0.89; p = 0.001) seen in this analysis, as falls are a well-established reason for ER visits and hospitalization in people with PD [37–39]. As respite care is the biggest single driver of costs, it also saw the biggest impact on reducing cost elements with increased ‘good ON-time.’ Combined with the increased chance of ADL independence, this finding underscores the potential economic benefits of improving ON-time in aPD management. Interestingly, care partner burden showed only minimal changes in response to improvements in 'good ON-time.' However, this finding should be interpreted cautiously because of the limited sample size; we were able to evaluate care partner burden in < 25% of care partners. This limitation may have affected our ability to detect significant changes in care partner burden. Furthermore, non-motor symptoms such as cognitive and mood changes, which are less impacted by motor fluctuations, may persistently impact care partner burden. Despite the minimal change in care partner burden, we observed a decrease in the need for professional care as 'good ON-time' increased.

While achieving 16 h/day of 'good ON-time' in people with aPD may be challenging, comparing those with ≥ 12 h to < 12 h reveals valuable insights. Patients with ≥ 12 h show slightly reduced clinical burden but significantly better QoL. Those with < 12 h experience higher HRU and costs. These findings underscore the importance of increasing 'good ON-time' and highlight the need to prioritize treatments that reduce OFF-time and stabilize or increase 'good ON-time' in aPD management [17–19]. Previous research in a general PD population has illustrated the increased utilization of healthcare resources associated with the presence of OFF-time and also a significant impact on the incremental hourly increase in OFF-time [40].

While using data from DSP offers valuable insights, there are some limitations of the dataset. The sample may be subject to selection bias, as patients who are more frequently consulted by their physicians are more likely to be included, and the results may be subject to responder and recall bias because of the self-reporting nature of the patient questionnaires. Additionally, the inclusion criteria for physicians were primarily based on their willingness to participate, which may limit generalizability. Diagnosis of aPD patients in this dataset was based on the judgment and diagnostic skills of the consulting physician, which may vary from center to center, because of a lack of an accepted and standardized definition of aPD as well as the fact that participating physicians were not necessarily movement disorder specialists. Indeed, the observation that 16.2% of this sample had 16 h ‘good ON-time’ would suggest that many of these patients do not have severe motor fluctuations on oral therapy, and their classification as having advanced disease may be due to other factors or a lack of awareness of what constitutes aPD. A recent study validating clinical indicators of aPD, which also used data from the Parkinson’s DSP, suggested a considerable disconnect between physician judgment of aPD and the presence of these clinical indicators [40]. Patients receiving, or who had previously used, DATs were excluded from this analysis; therefore, the proportion of the total aPD population that is represented by this analysis of patients on oral medication is not known. Furthermore, the reasons for the patients with aPD receiving oral therapy rather than DATs were not recorded, and this population may not be fully representative of the aPD population in these countries. Estimations of ‘ON-time’ were reliant on retrospective neurologist and patient reporting, which is a feasible method of assessment in a large population. ON-time was not directly measured as it was indirectly calculated based on the reported ‘OFF-time,’ hours of dyskinesia, and the proportion of dyskinesia time rated as troublesome. Therefore, any inaccuracy in recall and/or reporting of OFF-time by patients or neurologists would have affected the calculation of ON-time. Furthermore, there could be other confounding factors (such as the different healthcare system structures and cultural differences that may affect, for example, professional versus non-professional care partner status) that could not be measured in this dataset. Nevertheless, the aforementioned limitations regarding assessment and recall provide insight into the real-world management of people with PD. Strengths of this study include the fact that the DSP utilizes a validated methodology that captures impartial and robust real-world evidence from many patients, providers, and care partners that reflects current clinical practice in the US, Spain, Italy, UK, France, Germany, and Japan.

Conclusions

This multi-country, real-world study of people with aPD demonstrates the importance of ‘good ON-time’ as a measure of clinical outcome and highlights the need to ensure patients are on therapies that maximize improvement in ‘good ON-time.’ Hourly increases in ‘good ON-time’ were associated with better clinical outcomes (improvements in the number of uncontrolled motor and non-motor symptoms, number of falls and PD medication requirements), greater humanistic value (improvements to PD-related QoL and independence in performing ADL), and reduced economic burden (reductions in total HRU costs). These results emphasize the need for therapeutic strategies that maximize 'good ON-time' to ensure optimal patient outcomes. Further studies are needed to directly assess the impact of specific treatments that improve ‘good ON-time,’ such as DATs, on the clinical, humanistic, and economic outcomes outlined in our study.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by AbbVie Inc. AbbVie participated in study design, research, data collection, analysis and interpretation of data, writing, reviewing, and approving of the publication.

Medical Writing, Editorial, and Other Assistance

The authors acknowledge Aristide Merola, Aditi Kharat, and Ali Alobaidi for assistance with analyses and interpretation. Editorial support was provided by Martin Gilmour, PhD, CMPP, and Emily Eagles, CMPP, of ESP Medical Communications Ltd., Crowthorne, UK, funded by AbbVie.

Funding

Data collection was undertaken by Adelphi Real World as part of an independent survey, entitled the Adelphi Parkinson’s Disease Specific Programme, sponsored by multiple pharmaceutical companies of which one was AbbVie. AbbVie did not influence the original survey through either contribution to the design of questionnaires or data collection. Abbvie Inc. provided financial support for the study and funded the journal’s Rapid Service Fee. AbbVie participated in the interpretation of the data, review, and approval of the abstract. All authors contributed to the development of the abstract and maintained control over the final content.

Author Contributions

Joohi Jimenez-Shahed, Irene A. Malaty, Jean-Philippe Azulay, Ashwini Parab, Connie H. Yan, Prasanna L. Kandukuri, Pavnit Kukreja, Jorge Zamudio, Alexander Gillespie, and Angelo Antonini meet the ICMJE criteria for authorship and have contributed to the development of the manuscript and read and approved the final version for submission and agree to be accountable for the work. The concept of the analysis was provided by Joohi Jimenez-Shahed, Jorge Zamudio, Connie H. Yan and Pavnit Kukreja. The data interpretation was conducted by Connie H. Yan, Pavnit Kukreja, Jorge Zamudio, Joohi Jimenez-Shahed, Irene A. Malaty, Ashwini Parab, Jean-Philippe Azulay, and Angelo Antonini.

Data Availability

The survey materials and datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available as they are the intellectual property of Adelphi Real World. All requests for access should be addressed directly to Jack Wright (jack.wright@adelphigroup.com).

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

Joohi Jimenez-Shahed has received consulting fees from Medtronic, Abbvie, Bracket, AlphaOmega, Teva, Praxis, RegenXBio, Kyowa Kirin, Amneal, and TreeFrog. She has received research funding from Annovis and Sage. She serves on the data safety monitoring board for BlueRock Therapeutics and Emalex and on an advisory board for PhotoPharmics. Aristide Merola has received grant support from the NIH (KL2 TR001426). He has received speaker honoraria or advisory board honoraria from CSL Behring, AbbVie, Abbott, Medtronic, Theravance, and Cynapsus Therapeutics. He has received grant support from Lundbeck and AbbVie. Irene A. Malaty has participated in research funded by AbbVie, Emalex, Praxis, Neuroderm, Prilenia, Revance, and Sage but has no owner interest in any pharmaceutical company. She has received consulting fees from Abbvie, travel compensation or honoraria from Cleveland Clinic, Parkinson Foundation, Tourette Association, Medscape, and royalties from Robert Rose Publishers. Jean-Philippe Azulay has received compensation for consultancy and speaker-related activities from UCB, AbbVie, Kyowa Kirin, Zambon, Roche HAC Pharma, and Allergan. Alexander Gillespie is an employee of Adelphi Real World, a consulting company that was hired by AbbVie Inc., to perform analyses on the Adelphi Disease Specific Programme database. Angelo Antonini has received compensation for consultancy and speaker-related activities from UCB, Boehringer Ingelheim, Britannia, AbbVie, Kyowa Kirin, Zambon, Bial, Neuroderm, Theravance Biopharma, and Roche. He receives research support from Chiesi Pharmaceuticals, Lundbeck, Bial, Horizon2020 Grant 825785, Horizon2020 Grant 101016902, Ministry of Education University and Research (MIUR) Grant ARS01_01081, and Cariparo Foundation. He serves as consultant for Boehringer–Ingelheim for legal cases on pathological gambling. Aditi Kharat, Lakshmi P. Kandukuri, Ali Alobaidi, Pavnit Kukreja, Jorge Zamudio, Ashwini Parab, and Connie H. Yan are employees of AbbVie and may own stocks/shares in the company.

Ethical Approval

Data collection was undertaken in line with European Pharmaceutical Marketing Research Association guidelines and as such it does not require ethics committee approval. Each survey was performed in full accordance with relevant legislation at the time of data collection, including the US Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act 1996 and Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act legislation. All data were fully de-identified prior to receipt by Adelphi Real World. The respondents provided informed consent for use of their anonymized and aggregated data for research and publication in scientific journals.

Footnotes

Prior presentation: This manuscript is based on work that has been previously presented at the 74th Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Neurology from 2–7 April 2022, in Seattle, WA, USA. Jimenez-Shahed et al. The clinical and humanistic value of “good on-time” among patients with advanced Parkinson’s disease: A real-world study from 7 countries (P7-11.005). Neurology 2022; 98 (18_suppl.).

References

- 1.Cacabelos R. Parkinson’s disease: from pathogenesis to pharmacogenomics. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18:551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Giugni JC, Okun MS. Treatment of advanced Parkinson’s disease. Curr Opin Neurol. 2014;27:450–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kulisevsky J, Luquin MR, Arbelo JM, Burguera JA, Carrillo F, Castro A, et al. Advanced Parkinson’s disease: clinical characteristics and treatment. Part II. Neurologia. 2013;28:558–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Olanow CW, Obeso JA, Stocchi F. Drug insight: continuous dopaminergic stimulation in the treatment of Parkinson’s disease. Nat Clin Pract Neurol. 2006;2:382–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fasano A, Fung VSC, Lopiano L, Elibol B, Smolentseva IG, Seppi K, et al. Characterizing advanced Parkinson’s disease: OBSERVE-PD observational study results of 2615 patients. BMC Neurol. 2019;19:50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martinez-Martin P, Skorvanek M, Henriksen T, Lindvall S, Domingos J, Alobaidi A, et al. Impact of advanced Parkinson’s disease on caregivers: an international real-world study. J Neurol. 2023;270:2162–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chaudhuri KR, Azulay J-P, Odin P, Lindvall S, Domingos J, Alobaidi A, et al. Economic burden of Parkinson’s disease: a multinational, real-world, cost-of-illness study drugs. Real World Outcomes. 2024;11:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang W, Hamilton JL, Kopil C, Beck JC, Tanner CM, Albin RL, et al. Current and projected future economic burden of Parkinson’s disease in the US. npj Parkinsons Dis. 2020;6:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dahodwala N, Li P, Jahnke J, Ladage VP, Pettit AR, Kandukuri PL, et al. Burden of Parkinson’s disease by severity: health care costs in the US medicare population. Mov Disord. 2021;36:133–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hjalte F, Norlin JM, Kellerborg K, Odin P. Parkinson’s disease in Sweden-resource use and costs by severity. Acta Neurol Scand. 2021;144:592–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Malaty IA, Martinez-Martin P, Chaudhuri KR, et al. Does the 5-2-1 criteria identify patients with advanced Parkinson’s disease? Real-world screening accuracy and burden of 5-2-1-positive patients in 7 countries. BMC Neurol. 2022;22(1):35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Antonini A, Stoessl AJ, Kleinman LS, et al. Developing consensus among movement disorder specialists on clinical indicators for identification and management of advanced Parkinson’s disease: a multi-country Delphi-panel approach. Curr Med Res Opin. 2018;34(12):2063–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thach A, Jones E, Pappert E, Pike J, Wright J, Gillespie A. Real-world assessment of “OFF” episode-related healthcare resource utilization among patients with Parkinson’s disease in the United States. J Med Econ. 2021;24:540–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thach A, Jones E, Pappert E, Pike J, Wright J, Gillespie A. Real-world assessment of the impact of “OFF” episodes on health-related quality of life among patients with Parkinson’s disease in the United States. BMC Neurol. 2021;21:46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hauser RA, Deckers F, Lehert P. Parkinson’s disease home diary: further validation and implications for clinical trials. Mov Disord. 2004;19:1409–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garon M, Weck C, Rosqvist K, et al. A systematic practice review: providing palliative care for people with Parkinson’s disease and their caregivers. Palliat Med. 2024;38:57–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Olanow CW, Kieburtz K, Odin P, Espay AJ, Standaert DG, Fernandez HH, et al. Continuous intrajejunal infusion of levodopa-carbidopa intestinal gel for patients with advanced Parkinson’s disease: a randomised, controlled, double-blind, double-dummy study. Lancet Neurol. 2014;13:141–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weaver FM, Follett K, Stern M, Hur K, Harris C, Marks WJ, et al. Bilateral deep brain stimulation vs best medical therapy for patients with advanced Parkinson disease: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;301:63–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Katzenschlager R, Poewe W, Rascol O, Trenkwalder C, Deuschl G, Chaudhuri KR, et al. Apomorphine subcutaneous infusion in patients with Parkinson’s disease with persistent motor fluctuations (TOLEDO): a multicentre, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2018;17:749–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Soileau MJ, Aldred J, Budur K, Fisseha N, Fung VS, Jeong A, et al. Safety and efficacy of continuous subcutaneous foslevodopa–foscarbidopa in patients with advanced Parkinson’s disease: a randomised, double-blind, active-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Neurol. 2022;21:1099–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aldred J, Freire-Alvarez E, Amelin AV, Antonini A, Bergmans B, Bergquist F, et al. Continuous subcutaneous foslevodopa/foscarbidopa in Parkinson’s disease: safety and efficacy results from a 12-month, single-arm, open-label, phase 3 study. Neurol Ther. 2023;12:1937–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pahwa R, Aldred J, Gupta N, Terasawa E, Garcia-Horton V, Steffen DR, et al. Patterns of daily motor-symptom control with carbidopa/levodopa enteral suspension versus oral carbidopa/levodopa therapy in advanced Parkinson’s disease: clinical trial post hoc analyses. Neurol Ther. 2022;11:711–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fernandez HH, Odin P, Standaert DG, Henriksen T, Jimenez-shahed J, Metz S, et al. Healthcare resource utilization and device-aided therapy discussions with eligible patients across the Parkinson’s disease continuum: revelations from the MANAGE-PD validation cohort. Parkinsonism and Related Disorders [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2024 Jul 18];116. https://www.prd-journal.com/article/S1353-8020(23)00237-7/fulltext. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Anderson P, Benford M, Harris N, Karavali M, Piercy J. Real-world physician and patient behaviour across countries: disease-specific programmes—a means to understand. Curr Med Res Opin. 2008;24:3063–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Babineaux SM, Curtis B, Holbrook T, Milligan G, Piercy J. Evidence for validity of a national physician and patient-reported, cross-sectional survey in China and UK: the Disease Specific Programme. BMJ Open. 2016;6: e010352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Higgins V, Piercy J, Roughley A, Milligan G, Leith A, Siddall J, et al. Trends in medication use in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a long-term view of real-world treatment between 2000 and 2015. DMSO. 2016;9:371–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Code of Conduct/AER | EPHMRA [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jul 19]. https://www.ephmra.org/code-conduct-aer.

- 28.hitech_act_excerpt_from_arra_with_index.pdf [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jul 19]. https://www.healthit.gov/sites/default/files/hitech_act_excerpt_from_arra_with_index.pdf.

- 29.privacysummary.pdf [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jul 19]. https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/privacysummary.pdf.

- 30.Procedure Price Lookup for Outpatient Services|Medicare.gov [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jul 18]. https://www.medicare.gov/procedure-price-lookup/.

- 31.OpenDataNI. Health Trust Reference Costs 2017–18 [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2024 Jul 18] . https://www.data.gov.uk/dataset/71367291-5636-460f-a8fe-374780a16a8e/health-trust-reference-costs-2017-18

- 32.Welcome to Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jul 18]. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/english/index.html.

- 33.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Soh S-E, Morris ME, McGinley JL. Determinants of health-related quality of life in Parkinson’s disease: a systematic review. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2011;17:1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chaudhuri KR, Jenner P, Antonini A. Dyskinesia matters: but not as much as it used to. Mov Disord. 2020;35:900–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hayashi Y, Nakagawa R, Ishido M, Yoshinaga Y, Watanabe J, Kurihara K, et al. Off time independently affects quality of life in advanced Parkinson’s disease (APD) patients but not in non-APD patients: results from the self-reported Japanese Quality-of-Life Survey of Parkinson’s Disease (JAQPAD) Study. Parkinsons Dis. 2021;2021:9917539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Okunoye O, Horsfall L, Marston L, Walters K, Schrag A. Rate of hospitalizations and underlying reasons among people with Parkinson’s disease—population-based cohort study in UK primary care. J Parkinsons Dis. 2022;12:411–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Temlett JA, Thompson PD. Reasons for admission to hospital for Parkinson’s disease. Intern Med J. 2006;36:524–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Al-Hakeem H, Zhang Z, DeMarco EC, Bitter CC, Hinyard L. Emergency department visits in Parkinson’s disease: the impact of comorbid conditions. Am J Emerg Med. 2024;75:7–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Antonini A, Pahwa R, Odin P, Henriksen T, Soileau MJ, Rodriguez-Cruz R, et al. Psychometric properties of clinical indicators for identification and management of advanced Parkinson’s disease: real-world evidence from G7 countries. Neurol Ther. 2022;11:303–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The survey materials and datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available as they are the intellectual property of Adelphi Real World. All requests for access should be addressed directly to Jack Wright (jack.wright@adelphigroup.com).