Abstract

We relate the unfolding of a protein to its loss of structural stability or rigidity. Rigidity and flexibility are well defined concepts in mathematics and physics, with a body of theorems and algorithms that have been applied successfully to materials, allowing the constraints in a network to be related to its deformability. Here we simulate the weakening or dilution of the noncovalent bonds during protein unfolding, and identify the emergence of flexible regions as unfolding proceeds. The transition state is determined from the inflection point in the change in the number of independent bond-rotational degrees of freedom (floppy modes) of the protein as its mean atomic coordination decreases. The first derivative of the fraction of floppy modes as a function of mean coordination is similar to the fraction-folded curve for a protein as a function of denaturant concentration or temperature. The second derivative, a specific heat-like quantity, shows a peak around a mean coordination of 〈r〉 = 2.41 for the 26 diverse proteins we have studied. As the protein denatures, it loses rigidity at the transition state, proceeds to a state where just the initial folding core remains stable, then becomes entirely denatured or flexible. This universal behavior for proteins of diverse architecture, including monomers and oligomers, is analogous to the rigid to floppy phase transition in network glasses. This approach provides a unifying view of the phase transitions of proteins and glasses, and identifies the mean coordination as the relevant structural variable, or reaction coordinate, along the unfolding pathway.

Much interest is currently focused on the rapid and faithful folding of proteins from a one-dimensional sequence of amino acids in a random coil, to a three-dimensional biologically functional structure in the native state (1–4). Chemical and thermal denaturation of proteins are standard techniques in protein biochemistry to determine protein folding and unfolding equilibria and kinetics (3, 5, 6).

A general view of protein folding is that it begins with hydrophobic collapse, in which the random coil changes to a compact state, with the hydrophobic groups in the interior region and polar groups at the surface interacting with the surrounding water. The packing is not yet optimal, with hydrophobic groups somewhat free to slide about in the interior of the globule, until residues are locked in place by the formation of specific hydrogen bonds. These hydrogen bonds can be regarded as a sort of Velcro that locks the various structural elements in the folded protein together. Once these interactions are optimized, the native state is predominantly rigid with flexible hinges or loops at the surface—the number and distribution of these depending on the particular protein.

There have been many significant theoretical advances in understanding protein folding in recent years—including the concept of a funnel-shaped free-energy landscape (1, 7–9), simplified lattice models that are more tractable for simulations of folding (8, 10, 11), and more detailed but computationally intensive off-lattice models and molecular dynamics simulations (12–14). These approaches have increased our understanding considerably, but the actual steps along the folding pathway continue to remain elusive. A series of challenging experiments is required to probe the range of time scales involved in folding, from microseconds to seconds (3, 6).

We have concentrated on a simpler problem—that of analyzing the unfolding transition by dilution of contacts in the native structure. For proteins in which the unfolding process is reversible, this approach also decodes the folding pathway. We postulate that information about the folding pathway is contained within the density, strength, and specific location of the hydrogen bonds in the native state. To simulate denaturation, the hydrogen bonds and salt bridges within the structure are ranked according to their relative energies and broken one by one, from weakest to strongest, similar to the way these bonds would break in response to slowly increasing temperature. The transition toward flexibility in the protein is observed as the hydrogen-bond and salt-bridge network is disrupted, and these results are found to be robust against the introduction of some noise, or stochastic character, into the order in which the hydrogen bonds are broken (unpublished data). The effective hydrophobic interactions actually strengthen somewhat with moderate increases in temperature (16), so they are maintained rather than broken in this simulation. In a related paper, we show that the unfolding pathway can be followed step by step, and that the most stable supersecondary associations within a protein predicted by this approach (unpublished data) correspond well with the folding core, as determined experimentally by hydrogen/deuterium exchange NMR for a series of proteins (17). Here we focus on the characteristics of the phase transition itself between rigid and flexible states of the protein, and how the transitions compare between different proteins and between proteins and network glasses.

Rigidity in Networks

Rigidity, or structural stability, is a property that can be measured or calculated for a given network of vertices (e.g., atoms) connected by edges (such as bonds). In the 19th century, Maxwell (18) studied the dependence of network stability on the amount of cross-bracing in bridges and other engineering structures. Maxwell found an approximate relationship between the mean coordination of all of the joints in a truss framework and its global rigidity. In the past few years, using the important theorem of Laman (19) and its extensions (20, 21), new computational algorithms (22, 23) have allowed a detailed local determination of the rigidity of networks to be made (21, 24). These approaches exactly relate the number and spatial distribution of remaining bond-rotational degrees of freedom in the network to regions of rigidity and flexibility. This approach has been applied to network glasses (21), and we have used the background and knowledge gained from this work to investigate flexibility and rigidity within protein structures (unpublished data; refs. 24–27).

Glasses and Proteins

Network glasses are three-dimensional, cross-linked, covalently bonded noncrystalline materials. Glasses are often formed of mixtures of elements, like GexAsySe(1−x−y), where the subscripts identify the atomic fraction of germanium, arsenic, and selenium atoms. The mean coordination of atoms in such a glass is 〈r〉 = 4x + 3y + 2(1 − x − y) = 2x + y + 2, where x is the concentration of the 4-fold coordinated Ge atoms, y is the concentration of the 3-fold coordinated As atoms in the glass, and (1 − x − y) is the coordination of the 2-fold coordinated Se atoms. Studies have been done concerning the rigidity of such network glasses both experimentally (28) and by using computer-generated network models (21). The dominant forces are the bond-stretching and bond-bending forces that maintain the bond lengths and bond angles in the glass. Other forces are considerably weaker and can be neglected initially.

Glasses consisting primarily of long polymer chains (i.e., containing mainly Se atoms with a few cross links) are flexible and become rigid only as the number of cross links is increased. In glasses like GexAsySe(1−x−y), this can be accomplished by increasing x, the relative concentration of Ge, and hence the mean coordination, 〈r〉, of the glass. Extensive studies have shown that the phase transition from rigid to floppy in random network glasses takes place at 〈r〉 = 2.385 and is usually a continuous or second-order phase transition (21). It also has been shown that self-organization, such as the suppression of small rings of bonds and/or of locally stressed regions, can cause the transition to become discontinuous or first-order (29). This can occur, for example, when there are no nucleation sites for rigidity. In this case, the position of the transition is shifted only slightly to 〈r〉 = 2.389 (21), as shown by the purple and orange lines in Fig. 1 Left and Fig. 2.

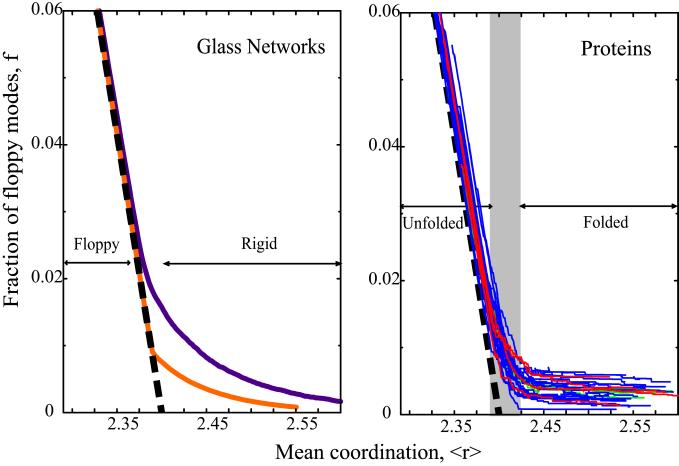

Figure 1.

The fractional number of floppy modes. f = F/3N in a glass as a function of the mean coordination, 〈r〉. The Maxwell approximation (Eq. 3) is shown as a thick black dashed line. (Left) The results for random glass networks (purple line, where the transition is second-order; orange line, for a network with an absence of small rings where the transition is first-order; ref. 21). (Right) Similar results for a representative set of 26 structurally and functionally diverse proteins (blue lines, monomers; red lines, dimers; green lines, tetramers; see Methods for details). The gray shaded region indicates the range in which protein folding/unfolding takes place.

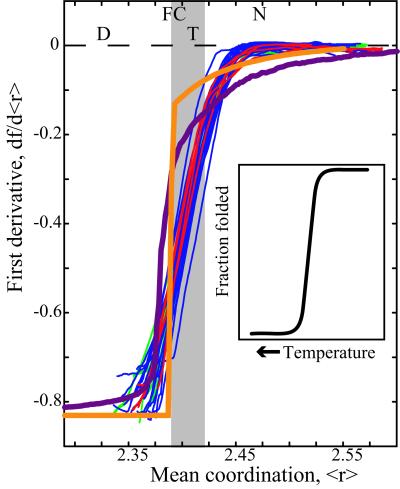

Figure 2.

Change in the fraction of floppy modes as a function of mean coordination for the set of 26 representative proteins shown in Fig. 1. Gray shading shows the transition region where folding takes place. The curves for the two kinds of glass networks from Fig. 1 Left (thick purple and orange lines) are shown superimposed on the protein curves. The notations at top indicate Denatured, Folding Core, Transition, and Native states of the proteins. For comparison with results for a typical thermal denaturation experiment, the Inset sketches the decrease in fraction of folded protein as temperature increases (adapted from figure 7.11 in ref. 42).

Like these glasses, proteins are complex, cross-linked polymers held together by covalent and weaker noncovalent interactions. Applying the rigidity techniques described above, we have developed the FIRST software (for Floppy Inclusions and Rigid Substructure Topography) (24, 26, 27) to analyze the rigid and flexible regions of proteins. As we simulate the thermal denaturation of a protein by incrementally breaking the noncovalent hydrogen-bond and salt-bridge interactions in order of their relative strengths, we use FIRST to determine the flexible and rigid regions within the protein for each of these successive networks of covalent and noncovalent bonds. This allows us to observe the phase transition from overall rigidity (structural stability) to overall flexibility (denaturation) of the protein through the parameters F (number of floppy modes, or degrees of bond-rotational freedom remaining in the protein) and 〈r〉 (mean coordination of the atoms, including noncovalent interactions). By monitoring F as a function of 〈r〉, we find that diverse proteins demonstrate rather universal behavior through the transition. Despite the finite size and different internal organization of proteins (with ≈104 atoms), they have similar rigid → flexible transitions when compared with glasses (with ≈1024 atoms). Very few amino acid sequences form proteins, and very few inorganic materials form amorphous networks as a result of failing to crystallize. Thus, both proteins and glasses can be regarded as rare occurrences in nature that share the properties of durability and metastability.

Methods

The FIRST Software.

FIRST can identify all of the structurally rigid and flexible regions within a protein of hundreds or thousands of residues within a few seconds. Computationally, FIRST uses the pebble game algorithm (21, 22) to generate a directed graph of the covalent and noncovalent constraints present within the protein. Once the constraint network has been generated to model the physical forces present in the protein, FIRST determines for every bond whether it is part of either a rigid cluster or an underconstrained region that forms a flexible connection between rigid clusters. In addition, the number of degrees of bond-rotational freedom (floppy modes) associated with each underconstrained region is also determined. As the protein is decomposed into rigid and flexible regions, the actual number of rotatable dihedral bonds is, in general, much greater than the number of degrees of freedom within that region. Collective motions are mapped out by FIRST, identifying which floppy modes are associated with which underconstrained regions (ref. 26; see http://www.pa.msu.edu/people/rader/). Similarly, within each rigid region, FIRST identifies the number of redundant constraints in stressed rigid regions. Redundant constraints cause rigid regions to be more stable, and remain stable even when one or more hydrogen bonds are broken within that region.

Maxwell Constraint Counting.

The Maxwell approach (18), although not taking into account the local distribution of constraints and forces, is surprisingly accurate for bulk properties (30, 31). By assuming a homogenous distribution of constraints, it is possible to calculate the transition point from rigid to flexible as measured by the mean coordination of atoms in the network. The mean coordination is defined by

|

1 |

where nr is the number of r-coordinated atoms. Maxwell constraint counting approximates the number of floppy modes (the residual degrees of freedom in the system), F, as

|

2 |

Here r/2 and 2r − 3 constraints are associated with the bond length and bond angles of an r coordinated site, and there are N sites. This formulation ignores any dangling bonds—i.e., terminal atoms which do not contribute to the global network rigidity (32). Eq. 2 simplifies to the general form

|

3 |

where 〈r〉 is given in Eq. 1 of course f must be positive, so a negative f given by Eq. 3 is interpreted as zero. Setting F = 0 gives an estimate for the transition point at which the number of floppy modes, and hence flexibility, vanishes. This occurs at a mean coordination, 〈r〉 = 2.4, separating the rigid and flexible phases (30, 31). The pebble game algorithm used in the FIRST software goes beyond this estimate, by using the actual structure and an exact enumeration. Both the density and placement of cross-linking hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic interactions result in the differential distribution of rigid (structurally stable) and flexible links, in the native as well as partially unfolded states of proteins.

Hydrophobic Tethers.

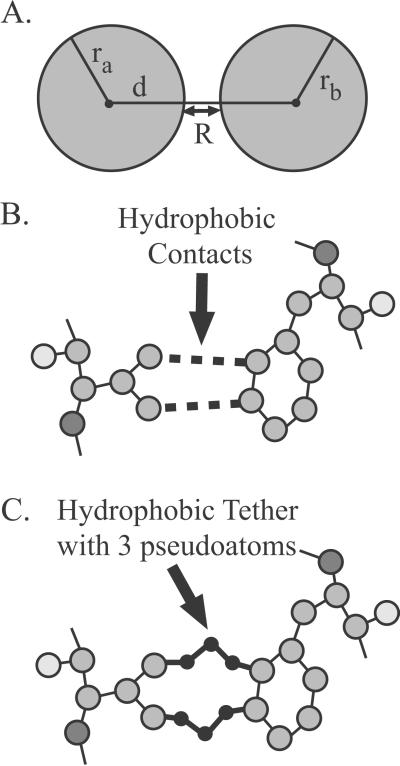

Hydrophobic forces contribute significantly to protein stability and are generally believed to be critical in driving the protein folding process (33). We model the tendency for hydrophobic atoms, principally carbon and sulfur atoms within proteins, to remain relatively near one another, rather than unfolding to interact with the solvent. These hydrophobic tethers restrict the local motion, which can be thought of as slippery. Hydrogen bonding groups, on the other hand, have angular as well as distance preferences, and thus are more specific and constraining.

We take the native structure of a protein from the Protein Data Bank (PDB; ref. 34) and include in the bond network its covalent bonds (with appropriate bond orders, lengths, and coordination angles), as well as defining its noncovalent hydrophobic, salt-bridge, and hydrogen-bond interactions as follows. Hydrophobic contacts are identified and modeled as constraints (both bond-length and bond-angle constraints) in FIRST as shown in Fig. 3. This model restricts the maximum distance between the two hydrophobic groups, while allowing them to slide with respect to one another. Such a tether is less specific than a hydrogen bond, which removes three degrees of bond-rotational freedom from the system, whereas each hydrophobic contact removes only two.

Figure 3.

Modeling hydrophobic contacts within proteins. Pairs of carbon and/or sulfur atoms, shown in A, are considered to make hydrophobic contacts if their van der Waals surfaces, represented by sphere radii ra and rb (without correction for attached hydrogen atoms) are within R = 0.25 Å. This allows atoms to either be in contact or lightly separated as shown in B, but without enough space between for water to intervene. Because first represents the protein as interatomic constraints, multijointed tethers with pseudoatoms at the joints shown in C are used to flexibly join atoms to form hydrophobic interactions. The flexible tethers allow two atoms forming a hydrophobic interaction to slip relative to one another, while remaining in the same vicinity.

Hydrogen Bonds.

Potential hydrogen bonds and salt bridges are identified according to geometrical rules (26). For PDB entries lacking polar hydrogen atom positions, the WHATIF software (35) is used to define hydrogen atom positions optimal for hydrogen bonding. Water molecules are included if they are entirely buried according to PRO_ACT (36), and can contribute to the protein hydrogen-bonding network; the number of buried waters ranges from 0 to 14 for the monomers in the study (see Table 1, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site, www.pnas.org). Bonds between the protein and ligands, including metals and other ions, are treated as covalent bonds if so specified in the PDB file (or if they are within covalent bonding distance); otherwise, their polar and hydrophobic atoms are subject to the same rules as protein atoms for determining noncovalent interactions with the protein.

Each potential hydrogen bond is assigned an energy by using a modified Mayo potential (37), which utilizes the length of the hydrogen bond relative to the optimal, equilibrium length for that pair of atoms based on their chemistry, and similarly evaluates the favorability of the three angles that define the orientation between donor–H and acceptor in the three-dimensional structure (more detailed information can be found in the supporting information on the PNAS web site). We have modified the Mayo potential (27) by strengthening the angular dependence on the donor–H–acceptor angle, so that it must be ≥120° for the bond to receive a favorable (negative) energy. This avoids including nonphysical H-bonds with angles near 90° [e.g., between C⩵O(i) and NH(i + 3), rather than NH(i + 4), in α-helices].

Peptide Bond Correction.

Proteins pose several additional cases for constraint counting (24, 26, 27). Rotations about the peptide bond and other double or partial double bonds in proteins are restricted in FIRST by a length constraint involving third nearest neighbor Cα atoms on either side of the peptide bond. We use an equivalent counting scheme by forming a six-membered ring, which is the simplest unit that is just rigid (when no bond deformation is allowed, as would be required for a boat-to-chair interconversion, as in cyclohexane). This representation locks the peptide and other nonrotatable bonds (e.g., within the guanidinium group in Arg; more detailed information can be found in the supporting information).

Bond Dilution and Pruning.

Network glasses can be computer generated for a specified mean coordination, 〈r〉, and the number of floppy modes, F (independent bond-rotational degrees of freedom), can be calculated (21, 29). The dependence of the number of floppy modes F on mean coordination 〈r〉 can be determined as shown in Fig. 1 (21). The analog to decreasing the mean coordination in glasses is to dilute the noncovalent interactions in proteins, simulating denaturation. Starting with the native structure, we vary 〈r〉 by removing hydrogen bonds and salt bridges one by one, according to their energies. At each step, singly coordinated atoms are pruned until there are none left, and side groups that do not connect to the rest of the protein via hydrophobic tethers or hydrogen bonds are also removed. This is done because such atoms do not contribute to the rigidity of the protein (32). This procedure allows the results on proteins to be compared directly with those for network glasses, as shown in Figs. 1 and 2.

Protein Database.

We have applied these methods to 26 proteins chosen to represent a range of CATH architectures (alpha, beta, and mixed alpha and beta; ref. 38), oligomeric states (monomers, dimers, and tetramers), folding mechanisms (two-state and multistate folders), and sizes (58–1332 residues): barnase (PDB ID code 1a2p), galectin (1a3k), myoglobin (1a6m), adenylate kinase (1ak3), bovine pancreatic trypsin inhibitor (1bpi), ribonuclease T1 (1bu4), α-lactalbumin (1hml), cytochrome c (1hrc), killer cell inhibitor receptor (1nkr), ribonuclease A (1ruv), dihydrofolate reductase (1rx1), tenascin (1ten), ubiquitin (1ubi), CheY (2chf), chymotrypsin inhibitor (2ci2), LIV-binding protein (2liv), lysozyme (3lzm), interleukin 1-β (4i1b), PFKinase/FBPase (1bif), electron transfer protein (1cku), HIV-1 protease (1hhp), interleukin 1-β converting enzyme (1ice), Fe-SOD (1ids), glyceraldehyde 3-P-dehydrogenase (1szj), and citrate synthase (2cts) (more detailed information can be found in the supporting information).

Results

Rigid Cluster Analysis.

Given a protein's native structure, we initially take all of the covalent bonds, hydrophobic tethers, hydrogen bonds, and salt bridges to define the constraint network for the protein. Given these constraints, FIRST identifies all of the rigid and flexible regions within a protein, and these results have been shown to correlate well with experimental measures of flexibility for a range of proteins (24, 26, 27). Fig. 4 shows these rigid regions mapped onto the protein structure of barnase (PDB ID code 1a2p). Singly colored regions represent a rigid cluster, whereas bonds divided into two colors remain rotatable and contribute to flexibility. The panels in Fig. 4 correspond to different subsets of hydrogen bonds used in the calculation at different steps in the dilution of bonds along the unfolding pathway. For each set of constraints used, FIRST calculates the mean coordination, 〈r〉, as described above. Fig. 4 Bottom roughly corresponds to the native state N having 〈r〉 = 2.45.

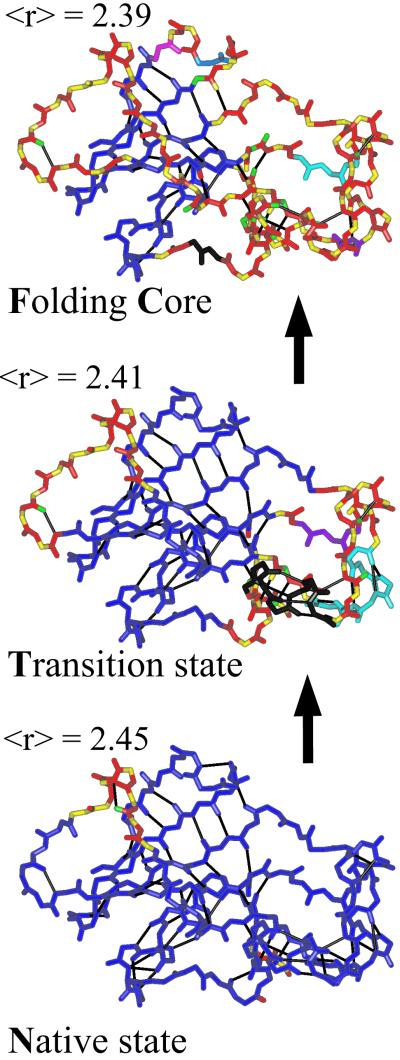

Figure 4.

Rigid cluster decompositions of barnase (PDB ID code 1a2p). Each image corresponds to a different value of 〈r〉 along the unfolding pathway shown in Figs. 2 and 5. Calculations were carried out for the entire protein structure, but only the backbone is shown for clarity, with main chain to main chain hydrogen bonds drawn as thinner black lines. Each bond is colored according to the rigid cluster to which it belongs. Bonds split into two colors indicate that the bond remains rotatable, and small regions of alternating color indicate a sequence of flexible bonds. Note how the largest rigid cluster, shown in dark blue, shrinks as the protein goes from the Native state at 〈r〉 = 2.45, through the Transition state at 〈r〉 = 2.41, to the Folding Core at 〈r〉 = 2.39, which just precedes the onset of complete flexibility.

Simulating thermal denaturation, weaker hydrogen bonds are broken until the transition state, T, is reached, with 〈r〉 = 2.41. The transition state is defined by the inflection point along the first derivative shown in Fig. 2, or equivalently, the peak position in Fig. 5. Finally, in Fig. 4 Top the folding core, FC, is shown. This prediction for barnase (unpublished data) defined as the last point in the thermal denaturation when two secondary structures (any pairing of α-helices and/or β-strands) form a mutually rigid cluster; any further dilution of the bond network would break this region into independently mobile units. Fig. 8, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site, shows a detailed comparison of the flexible and rigid regions in barnase as a function of residue number, along with their comparison with experimentally determined crystallographic temperature factors (measuring relative flexibility) and Fersht Φ values (ref. 39; reflecting whether a residue at the transition state has a native-state-like conformation).

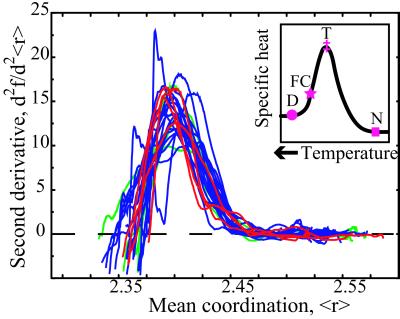

Figure 5.

The second derivative of the fraction of floppy modes as a function of mean coordination for the set of 26 proteins from Figs. 1 and 2. The Inset shows a sketch of the specific heat for a protein with the Denatured state, Folding Core, Transition state, and Native state indicated. The x axis of the Inset has the temperature increasing to the left.

Flexibility for Glasses and Proteins.

The results of rigid cluster analysis can also be tracked quantitatively along the unfolding pathway in terms of the change in number of bond-rotational degrees of freedom (F) as the mean coordination decreases. The fraction of floppy modes, f = F/3N, is shown in Fig. 1 for a range of proteins and for two limiting models of network glasses. The approximate Maxwell result of Eq. 3 is shown as the black dashed straight line in Fig.1 Left and Right. The overall similarity in the flexibility transition behavior of f for the diverse proteins and glasses is striking.

To examine these results in more detail, in particular the phase transition region shown in gray in Fig. 1, we have obtained the first and second derivatives by a numerical procedure, as shown in Figs. 2 and 5 (to obtain the first and second derivatives of f, we fit to a cubic equation over an interval corresponding to Δ〈r〉 = 0.75, which contained typically from 90 to 2,000 data points). The fraction of floppy modes, f, plays the role of a free energy as the transition is traversed, and as such the second derivative couples to the fluctuations and reaches a maximum at the transition point as shown in Fig. 5. In Fig. 2, we see the sharp rise of the first derivative through the transition region, again marked in gray. One of the glass models (orange line) shows a first-order transition as indicated by the discontinuity at 〈r〉 = 2.389. We note that the approximate Maxwell result in Eq. 3 would give a discontinuity at 〈r〉 = 2.4 from −5/6 = −0.833 to zero. The insert in Fig. 2 is adapted from several folding experiments (33) showing that as the temperature increases, the fraction of folded protein decreases.

The second derivative, shown in Fig. 5, is noisier, because of the numerical differentiation, but nevertheless shows similar behavior for the 26 proteins, with the peak that defines the transition state occurring at 〈r〉 = 2.405 ± 0.015. There is no obvious pattern in size, architecture, oligomeric state, or ligand content for the few proteins with irregular curves. Cytochrome c (PDB ID code 1hrc) is the one protein with a bimodal curve that decreases near the transition region, and this behavior occurs both when the heme group is included or excluded from the calculation. Proteins with somewhat broad peaks and a shoulder at lower 〈r〉 values are α-lactalbumin (1hml), barnase (1a2p), and GAPDH (1szj). The behavior of all proteins becomes predictably noisier at low mean coordination values, as more and more hydrogen bonds are removed from the native structure. The Inset in Fig. 5 compares these results with the specific heat curve for a typical protein (41, 42). The shape of the second derivative in Fig. 5 is suggestive of a relationship with the specific heat, sketched in the Inset. The two quantities are similar in that both are related to fluctuations, with specific heat reflecting fluctuations in the energy. It is unclear whether the width of the experimentally measured specific heat is associated with a single protein, or broadened because of monitoring an ensemble of unfolding proteins. The specific heat of a single protein as it unfolds could be considerably more narrow than the measured specific heat, which will be known once experiments can be done on single proteins.

Discussion

Remarkably, both glasses and proteins display a very similar dependence of the number of independent bond-rotational degrees of freedom, or floppy modes, on mean coordination, as seen by comparing the results from glass networks with the results from proteins in Figs. 1 and 2. This implies that proteins are similar to network glasses, in that the folded to unfolded transition in proteins can be viewed as a rigid to flexible transition of the kind observed in network glasses.

From studies of network models for glasses, it is known that the phase transition from rigid to floppy is continuous or second-order if the network is random. However, if structural restrictions are placed on the topology of the network, such as the absence of small rings of bonds or the avoidance of stressed regions when possible, then the transition can become discontinuous or first-order (29). A protein can be considered as a particular example of a self-organized network (4), where the linear polypeptide chain folds and cross-links to create the three-dimensional native structure. We have shown that the largest rigid cluster of a protein fragments into typically four or five independently rigid regions at the transition point (unpublished data); hence, the transition appears to have more of a catastrophic or first-order character, albeit rounded because of the finite size of a protein. Here, we use first- and second-order to refer to the thermodynamic behavior of the phase transition, rather than to the kinetics of the transition or whether the protein is a two-state folder or passes through intermediates. Future studies looking at the detailed structural pathways during unfolding, as shown in Fig. 4, will allow such questions to be addressed. Within the folding regime (gray region in Fig. 2) common to the proteins, there is substructure in the derivative curve, which has become more pronounced upon differentiation. Whether this is significant and can be used to define types of unfolding pathways, or whether this is due to noise, remains to be studied.

The differences between proteins and glasses are in the nature of their self-organization and the fact that proteins have a finite number of atoms and are not at the thermodynamic limit, in which the number of atoms tends to infinity, as is strictly required for a phase transition to occur. Nevertheless, the number of atoms in a protein, which is typically thousands, is enough to give strong resemblance to phase transition behavior. The self-organization noted here may contribute to folding, as well, by driving folding rapidly toward a unique, stable structure, and hence overcoming Levinthal's paradox (15).

Conclusions

We have shown that the protein folding transition can be viewed as a flexible to rigid phase transition, similar to that observed for network glasses. The mean coordination, 〈r〉, of atoms in the protein, including noncovalent interactions, can be regarded as the reaction coordinate controlling protein folding, and provides a unifying treatment of the dynamic and structural processes involved. Proteins are self-organized networks, because of the special nature of the cross-linking of the polypeptide chain via hydrophobic contacts and hydrogen bonds. This makes the protein folding transition more first-order than second-order, albeit rounded because of finite size effects in the network. This transition is shared among diverse proteins ranging from all-α to all-β folds, and from monomers to tetramers, and occurs once the protein denatures to a mean coordination of 〈r〉 = 2.41, which is very similar to the value found in network glasses.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank A. R. Day, D. Jacobs, M. Lei, J. C. Schotland, and W. Whiteley for continuing discussions. Discussions with many biochemists have contributed to our modeling of the relevant forces, which is essential to the success of these calculations. We also thank the Center for Biological Modeling at Michigan State University and the National Science Foundation under Grant DMR-0078361 for financial support.

Footnotes

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

References

- 1.Bryngelson J D, Onuchic J N, Socci N D, Wolynes P G. Proteins Struct Funct Genet. 1995;21:167–195. doi: 10.1002/prot.340210302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Honig B. J Mol Biol. 1999;293:283–293. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Radford S E. Trends Biochem Sci. 2000;25:611–618. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)01707-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baker D. Nature (London) 2000;405:39–42. doi: 10.1038/35011000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jackson S E. Folding Des. 1998;3:R81–R91. doi: 10.1016/S1359-0278(98)00033-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eaton W A, Muñoz V, Hagen S J, Jas G S, Lapidus L J, Henry E R, Hofrichter J. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 2000;29:327–359. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.29.1.327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Onuchic J N, Luthey-Schulten Z, Wolynes P G. Annu Rev Phys Chem. 1997;48:545–600. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physchem.48.1.545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chan H S, Dill K A. Proteins Struct Funct Genet. 1998;30:2–33. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0134(19980101)30:1<2::aid-prot2>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brooks C L, III, Onuchic J N, Wales D J. Science. 2001;293:612–613. doi: 10.1126/science.1062559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klimov D K, Thirumalai D. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:6166–6170. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.11.6166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mirny L, Shakhnovich E. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 2001;30:361–396. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.30.1.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Daggett V, Li A, Itzhaki L S, Otzen D E, Fersht A R. J Mol Biol. 1996;257:430–440. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duan L, Wang L, Kollman P A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:9897–9902. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.17.9897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shea J-E, Brooks C L., III Annu Rev Phys Chem. 2001;52:499–535. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physchem.52.1.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Levinthal C. J Chim Phys Phys Chim Biol. 1968;65:44–45. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tanford C. The Hydrophobic Effect: Formation of Micelles & Biological Membranes. New York: Wiley; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li R, Woodward C. Protein Sci. 1999;8:1571–1591. doi: 10.1110/ps.8.8.1571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maxwell J C. Philos Mag. 1864;27:294–299. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Laman G. J Eng Math. 1970;4:331–340. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tay T-S, Whiteley W. Struct Topol. 1985;9:31–38. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thorpe M F, Jacobs D J, Chubynsky N V, Rader A J. In: Rigidity Theory and Applications. Thorpe M F, Duxbury P M, editors. New York: Kluwer Academic; 1999. pp. 239–277. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jacobs D J, Thorpe M F. Phys Rev Lett. 1995;75:4051–4054. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.75.4051. ; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jacobs D J, Thorpe M F. Phys Rev E. 1996;53:3682–3693. doi: 10.1103/physreve.53.3682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jacobs D J, Kuhn L A, Thorpe M F. In: Rigidity Theory and Applications. Thorpe M F, Duxbury P M, editors. New York: Kluwer Academic; 1999. pp. 357–384. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thorpe M F, Hespenheide B M, Yang Y, Kuhn L A. In: Pacific Symposium on Biocomputing. Altman R B, Dunker A K, Hunter L, Lauderdale K, Klein T, editors. Singapore: World Scientific; 2000. pp. 191–205. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jacobs D J, Rader A J, Kuhn L A, Thorpe M F. Proteins Struct Funct Genet. 2001;44:150–165. doi: 10.1002/prot.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thorpe M F, Lei M, Rader A J, Jacobs D J, Kuhn L A. J Mol Graph Model. 2001;19:60–69. doi: 10.1016/s1093-3263(00)00122-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Boolchand P, Selvanathan D, Wang Y, Georgiev D G, Bresser W J. In: Properties and Applications of Amorphous Materials. Thorpe M F, Tichý L, editors. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic; 2001. pp. 97–132. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thorpe M F, Jacobs D J, Chubynsky M V, Phillips J C. J Non-Cryst Solids. 2000;266–269:859–866. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Phillips J C. J Non-Cryst Solids. 1979;34:153–161. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thorpe M F. J Non-Cryst Solids. 1983;57:355–370. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Boolchand P, Thorpe M F. Phys Rev B. 1994;50:10366–10368. doi: 10.1103/physrevb.50.10366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dill K A. Biochemistry. 1990;29:7133–7155. doi: 10.1021/bi00483a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Berman H M, Westbrook J, Feng Z, Gilliland G, Bhat T N, Weissig H, Shindyalov I N, Bourne P E. Nucl Acids Res. 2000;28:235–242. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vriend G. J Mol Graph. 1990;8:52–56. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(90)80070-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Williams M A, Goodfellow J M, Thornton J M. Protein Sci. 1994;3:1224–1235. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560030808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dahiyat B I, Gordon D B, Mayo S L. Protein Sci. 1997;6:1333–1337. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560060622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Orengo C A, Michie A D, Jones S, Jones D T, Swindells M B, Thornton J M. Structure (London) 1997;5:1093–1108. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(97)00260-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Oliveberg M, Fersht A R. Biochemistry. 1996;35:2738–2749. doi: 10.1021/bi950967t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Duxbury P M, Jacobs D J, Thorpe M F, Moukarzel C. Phys Rev E. 1999;59:2084–2092. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Privalov P L. J Mol Biol. 1996;258:707–725. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Angell C A. In: Hydration Processes in Biology. Bullisent-Funel M C, editor. Amsterdam: IOS Press; 1999. pp. 127–139. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.